95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 04 January 2022

Sec. Global Change and the Future Ocean

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.674804

This article is part of the Research Topic Sustainable Development Goal 14 - Life Below Water: Towards a Sustainable Ocean View all 25 articles

This article contributes to a growing body of research on the Large Marine Ecosystems Concept. It particularly shines the light on the Guinea Current Large Marine Ecosystem (GCLME), a biodiverse maritime domain providing essential ecosystem services for the survival of a large population while at the same time under intense pressure from both anthropogenic and natural factors. With the need for coordination and cross-border ocean management and governance becoming imperative due to the magnitude of challenges and maritime domain, we examine the factors that underpin ocean governance and those key elements necessary for cross-border ocean governance cooperation in the region. The research draws on qualitative data collected from peer-reviewed literature and documents sourced from different official portals. Three countries in the region (Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon) are selected as the descriptive and comparative case studies to examine: (i) the factors that drive ocean governance (including geographical features, maritime jurisdictions, political framework, maritime activities, and associated pressures), and (ii) key enabling factors for cross-border ocean governance and cooperation in the GCLME (including marine and coastal related policy and legal framework convergence from international to national including, and shared experiences, common issues and joint solutions). We show that the biophysical maritime features, the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), otherwise known as the Law of the Sea (LOS), inherent political characteristics and the relics of colonization, and increasing ocean use and pressure on the ecosystem make ocean governance challenging in the region. Our analysis also reveals a varying level of convergence on international, regional and national legal, policy and institutional frameworks between the case studies on ocean-related aspects. Significant convergence is observed in maritime security, ocean research, and energy aspects, mostly from countries adopting international, regional and sub-regional frameworks. National level convergence is not well established as administrative and political arrangement differs from country to country in the region. These different levels of convergence help reveal procedural and operational shortcomings, strengths, weaknesses, and functional capability of countries within a cooperative ocean governance system in the region. However, experience from joint-implementation of projects, pre- and post-colonial relations between countries and the availability of transboundary organizations that have mainly emerged due to sectoral ocean challenges would play a crucial role in fostering cross-border ocean governance cooperation in the region.

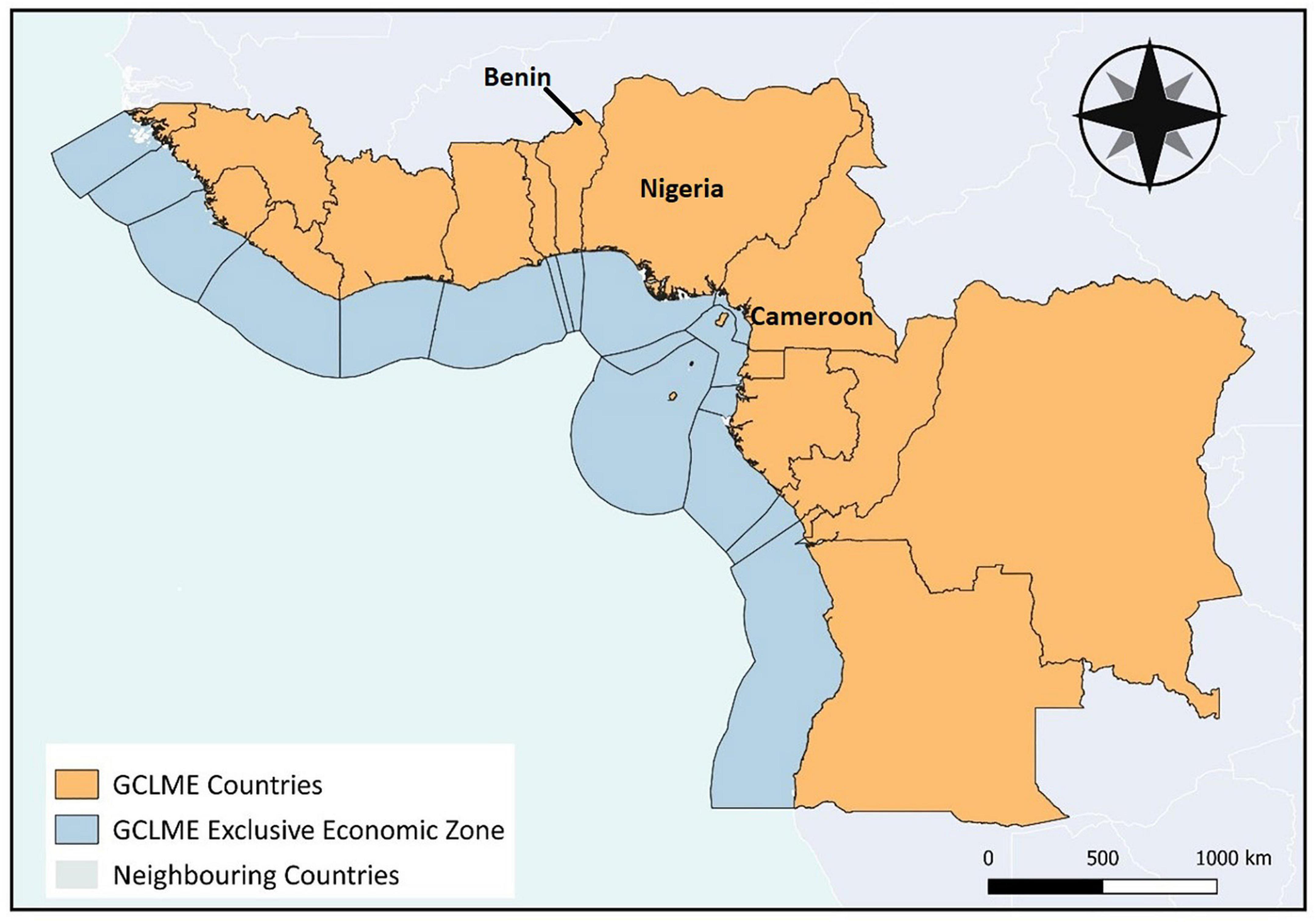

The Guinea Current Large Marine Ecosystem (GCLME) is a total area of 1,958,802 km2 bordering: Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, The Republic of Benin (Benin), Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Congo, Angola, The Democratic Republic of Congo, São Tomé and Príncipe (IW:LEARN, 2016; Figure 1). It falls in the cluster of Large Marine Ecosystems exhibiting economic development levels within the low to medium range (based on the night light development index) and medium levels of collapsed and overexploited fish stocks (Ukwe et al., 2006; UNESCO/IOC, 2020a). According to UNESCO/IOC (2020a), the overall risk factor in the GCLME is rated high following a combined measure of the Human Development Index and the averaged indicators for fish and fisheries, pollution and ecosystem health modules. It is a marine region endowed with an extensive coastline and maritime space, which provides the basis for substantial economic and social proportion activities (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020). About 47% of the 248 million GCLME’s people lives (200 km) off its coast and are dependent on the resources therein (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020), and projected to increase in share to 52% in 2100 (Barbier, 2015). However, intense competition and unsustainable use of resources by different sectors, coupled with climate change, negatively affect the ecosystem and people who depend on them (Abe et al., 2016; Okafor-Yarwood, 2018).

Figure 1. Map showing the geographical scope of the GCLME (Data source: Flanders Marine Institute, 2019).

With the magnitude of marine space under the jurisdiction1 of the GCLME countries (see Table 1), collaborative, management of different aspects of the maritime areas is therefore imperative to protect biodiversity and secure livelihoods. Weak collaborative processes in the GCLME impedes stakeholders to manage the ocean cohesively, minimize conflict, and maintain a long-term flow of ecosystem goods and services, just as resource mismanagement, degradation, and depletion become increasingly evident (IMS-UD/UNEP, 2015; Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020). Likewise, the absence of adequate coordinating mechanisms for marine activities further entrenches fragmentation of governance architectures and duplication of efforts. However, the inadequate implementation/enforcement of the existing legal, policy, and institutional frameworks, combined with the significant extent of the maritime domain, might be why the required collaboration and coordination necessary to ensure sustainability in the GCLME needs unique attention. There have also been calls to strengthen cooperation across national boundaries to ensure ocean sustainability. This is principal because of specific governance gaps in Africa, such as the lack of a common political/economic agenda and coordinated approach to using and managing ocean resources (e.g., IMS-UD/UNEP, 2015).

How do we address these reprising challenges so that national and regional coordination and cross-border collaboration in the GCLME becomes possible to ensure the overall sustainability of coastal and marine spaces? Vivero and de Mateos (2015) believe that understanding the elements that shape the emergence of ocean governance, including geographical features (physical and biological), maritime jurisdictions, political framework, maritime activities, and associated pressures on different scales, should be the first prerogative. To Boateng (2006), a clear understanding of available frameworks and their consequent impact on resources and stakeholders’ power is required. Boateng assertion holds true because the governance of coastal and marine space is viewed as the process of policymaking and negotiation nested between governmental institutions at several levels, civil society organizations and market parties (OECD, 2004; Momanyi, 2015; Horigue et al., 2016).

This paper aims to point out how cross-border collaboration for ocean governance in the GCLME may become possible by understanding the conceptual and normative construction, strength and weakness of ocean governance in the GCLME. To achieve this aim, the paper poses three research questions: (1) What are the underlining elements that shape the emergence of marine governance in the GCLME? (2) What are the enabling factors for cross-border ocean governance cooperation in the GCLME? (3) What is the capacity of the existing transboundary organizations to foster the most significant cross-boundary ocean governance cooperation in the GCLME?

The GCLME provides the opportunity to explore the research questions in this paper, considering that the region: (1) in contrast to other regions on in the continent, is a setting where relatively all maritime boundary disputes have been resolved, (2) exhibits a wide range of biomes and ecoregions (Miller and Gosling, 2013) and, (3) consists of culturally diverse nations with different governance regimes (i.e., centralized/federal), which results in a wide range of ocean governance system transformations due to human action and social peculiarities. Also, it includes areas where the maritime space has been aggressively exploited for its resources, uniqueness and strategic location for more than five centuries (i.e., from the transatlantic slave trade era to the pre and post-colonization times). It is also an area where early European colonization expanded new forms of maritime trade and is currently the most active frontier of fisheries, agriculture, industrialization and population expansion in the world (Harley, 2015; Abobi and Wolff, 2020; Nwafor et al., 2020; OECD, 2020).

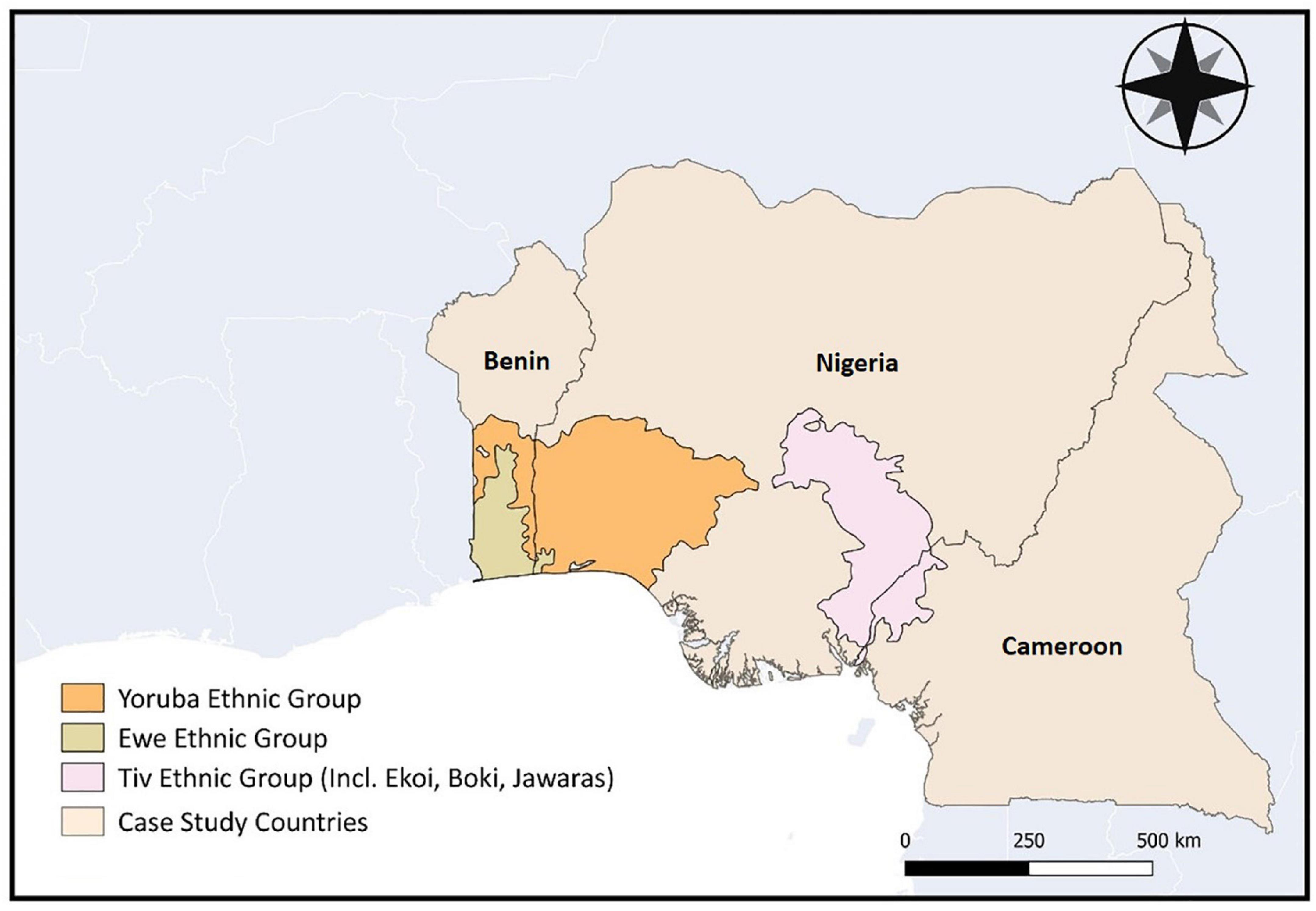

Cross-national research in the GCLME region poses many methodological and logistically challenges (Copans, 2020). These methodological and logistical challenges also come amidst an increasing call to decolonize academic research in the region (Adams, 2014; Seehawer, 2018). Therefore, answers to the research questions are explored using Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon as descriptive and comparative case studies to highlight the functional capability of some GCLME countries to cooperate toward ocean governance and existing transboundary institutions.

Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon are chosen because they share maritime and land borders and social and ethnographic affinity (Edung, 2015; Nwokolo, 2020). They have historically cooperated on several developmental areas pre-and post-independence. Also, many ocean development projects are currently taking place in these countries’ maritime jurisdictions. These include developments in the oil and gas, maritime security, ports, coastal land concessions and reclamation sectors which have attracted the most significant attention from citizens, civil society groups and investors.

Although cross-national qualitative research presents many issues, including issues related to the selection process of countries and the analytical strategy (Gharawi et al., 2009), its application in this paper gives room for the development of new perspectives in the GCLME governance research. It also allows the development of robust and context-driven research in the Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) governance concept. Likewise, much of the academic literature on the LME concept focuses on the need for and the benefits of cross-border ocean management. However, little research has been conducted on how cross-border cooperation may be best advanced between neighboring jurisdictions in the GCLME or the political and institutional conditions that can facilitate practical cross-border cooperation at an LME scale.

The selection of Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon as analytical and comparative case studies allows for a cross-national qualitative research approach to be applied, a method not commonly applied in ocean governance system research. It has also permitted comparisons between ocean governance systems in Francophone and Anglophone regions, differing political and post-colonial attitudes that affect cross-border participation in policy and development planning.

This paper is outlined in four sections. The first section reveals factors that shape the emergence of ocean governance in the GCLME by analyzing the three case studies’ geopolitical variables, including geographical features, maritime jurisdictions, political framework, maritime activities, and associated pressures. The second section moves to identify the structures and mechanisms staged at international, regional and national levels that tend to promote or frustrate cross-border ocean. The third section assesses the current capacity of existing transboundary institutions in the GCLME to foster cross-national ocean governance cooperation based on Kidd and McGowan’s (2013) analytical framework. It provides an opportunity to identify a spectrum of transnational ocean governance partnership approaches that could be applied in the region. The fourth concluding session discusses the study results by highlighting challenges facing coastal and marine governance and transboundary collaboration in the GCLME while emphasizing the need to enhance cross-sectoral coordination at the national and improve cooperation among regional institutions.

The present paper is based on a desk review of secondary data collected from peer-reviewed literature and official documents sourced from the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) FAOLEX and ECOLEX databases, the UN treaty collection, the African Union (AU) database of treaties, conventions, protocols and charters, and other national repositories. It generally employs a qualitative research approach to understand factors that either bring weak or strong ocean governance. Likewise, it is used to explore mechanisms that foster or wreck cross-border cooperation and analyze the capacity of existing institutions to promote cross-border ocean governance coordination and cooperation. A combination of two political science approaches is adopted to guild the logic and analysis in this paper, including the Constructivist Institutionalism and Historical Institutionalism approach. Following Steinmo (2008) and Bell (2011), these two approaches are essential for this study to dissect the ‘ideational’ foundation of ocean governance and examine how institutions’ creation, maintenance, and change can foster cross-border cooperation for ocean governance in a particular historical timeframe. After all, politics, policies and people constantly shape the ocean, just as political ecology themes (power and politics, narratives and knowledge, scale and history, and environmental justice and equity) are interconnected with governance and management (Bennett, 2019).

Given the previously mentioned aspects of geopolitical, sociological, historical, and developmental idiosyncrasies, the GCLME and the three case studies (Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon) are chosen to undertake this study. Gerring (2013) and Devare (2015) had earlier raised concern about investigators believing they have full knowledge of a particular study area, and maintained that knowledge is always partial. However, information collected from existing documents is complemented with the first-hand knowledge of the authors about the environmental, political, and socio-economic realities of GCLME and the selected case studies.

To answer the questions posed by this paper, we carried out three types of investigations. Attending to the first research question “What are the underlining elements that shape the emergence of marine governance in the GCLME?”, we employed a descriptive-analytical research approach to examine the ideational and normative factors which drive ocean governance in the GCLME using Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon as analytical and comparative case studies. A descriptive-analytical research approach helps point toward causal understanding and reveals mechanisms behind causal relationships (Loeb et al., 2017).

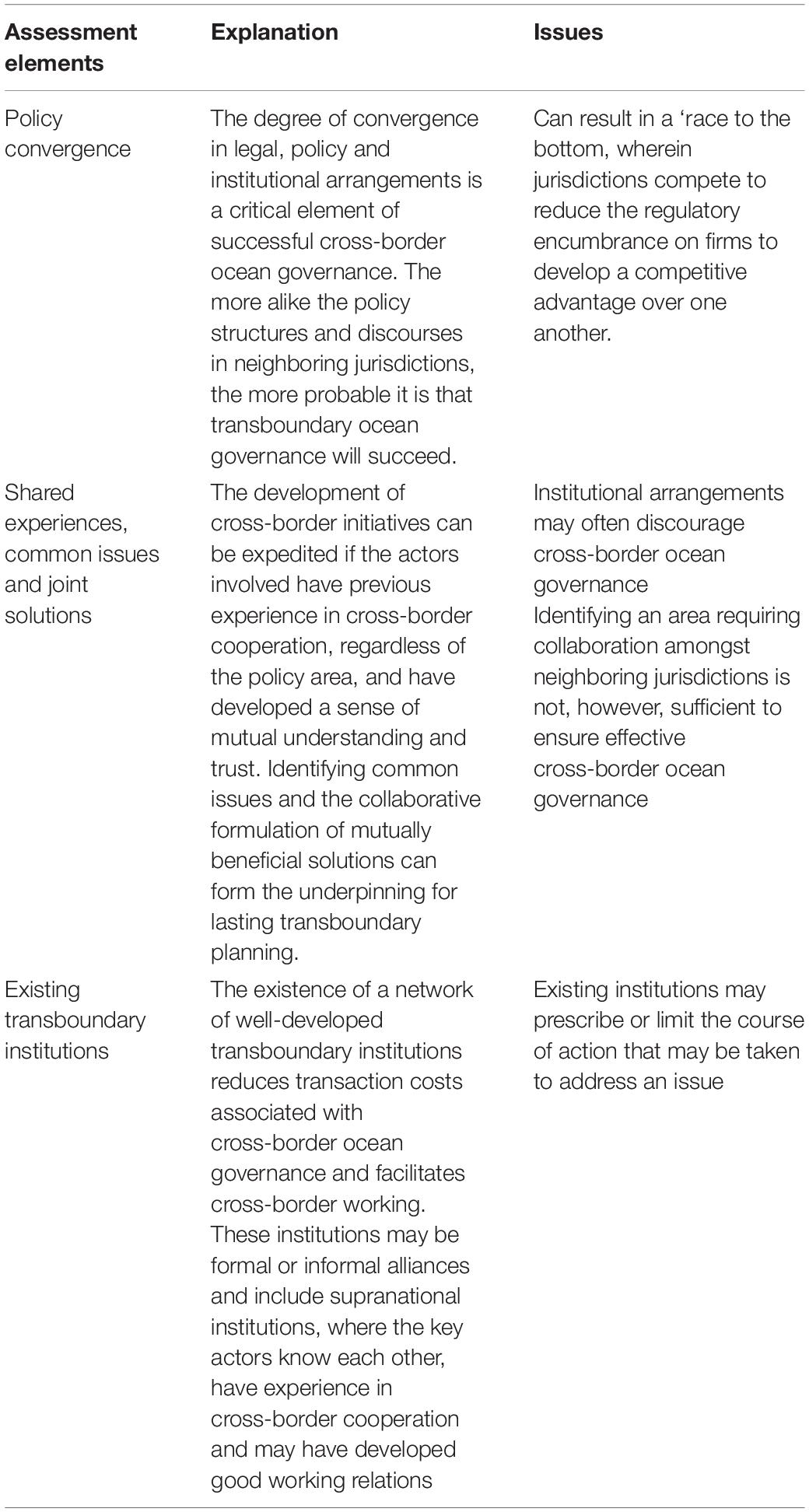

Once the ideational and normative factors that shape ocean governance in the region are described, it became essential that answering our second research question, “what are the key enabling factors for cross-border ocean governance cooperation in the GCLME?” would require the examination of the operational and deliberative mechanisms staged at the international, regional and national levels to promote cooperative ocean governance. Previous studies on ocean governance (e.g., Rochette et al., 2015; Weiand et al., 2021) argues that this examination enables the understanding of how collaborative ocean governance in a particular context is constructed, particularly through inter-subjective operations embodied in the governance systems and institutional frameworks. A range of existing analytical frameworks from previous studies (e.g., Fanning et al., 2007, 2013; Hill and Kring, 2013; Herman, 2016) could be adopted to answer our second question. Pearce et al. (2015) posit that such frameworks improve validity and reliability in assessment, allowing researchers to create robust assessment instruments more easily. However, many of these frameworks focus more on the nature of cross-border ocean governance processes and their effects on managing marine resources. But the authors insist only on one dimension of the cross-border ocean governance or integration, typically favoring the functional capacity of governance systems and institutional frameworks dimensions of differing states. Therefore, taking a cue from a transboundary marine spatial planning perspective, we adopt Flannery et al. (2015) analytical framework. Flannery and colleagues believe that for cross-border ocean governance to be possible, it is critical to identify contextual factors that are likely to impact the success of transboundary partnership initiatives. These factors are identified as policy convergence, the common conceptualization of planning issues, joint vision and strategic objectives, shared experience, and existing transboundary institutions. We, however, categorize the factors into three broad elements, which are presented and explained in the Table 2 below.

Table 2. Explanation of the Flannery et al. (2015) theoretical framework.

To answer the third question “what is the capacity of the existing transboundary organizations to foster the most significant cross-boundary ocean governance cooperation in the GCLME?”, Kidd and McGowan’s (2013) ladder of transnational partnership is adopted to assess existing transboundary organizations’ nature in the region. Considering the region’s and case study countries’ multi-level ocean governance structure, this is to evaluate conditions and institutions that may affect cross-border ocean governance cooperation. Other cross-boundary institutional analysis frameworks such as Herrera et al. (2005) and Rahman et al. (2017) are based on institutional efficiency criteria and the relationship of different rule levels. In contrast, Kidd and McGowan’s ladder provides the opportunity to explore further motivations for collaboration between cross-border institutions in particular marine settings. It also helps to grasp which institutions have reached an atmosphere of established understanding applicable to transboundary initiatives.

In Kidd and McGowan’s ladder (see Figure 2), the first rung on the ladder concerns Information Sharing, focusing on trust-building among a range of stakeholders, understanding each other’s perspectives, and building capacity to support integrated ocean approaches. Administration Sharing is the second rung that presents potential areas where collaborative advantages for ocean governance advantages are perceived. The third rung on the ladder is where stakeholders identify Agreed Joint Rules that can facilitate establishing standard procedures or protocols related to specific areas of activity. Combined Organization relates to the level where new joint research institutes, joint planning teams, or other formal institutional arrangements of a transnational nature are created. Combined Constitution occupies the fifth rung of the ladder and relates to how cooperative efforts are formalized through new legal agreements and may secure new political order for ocean governance and management.

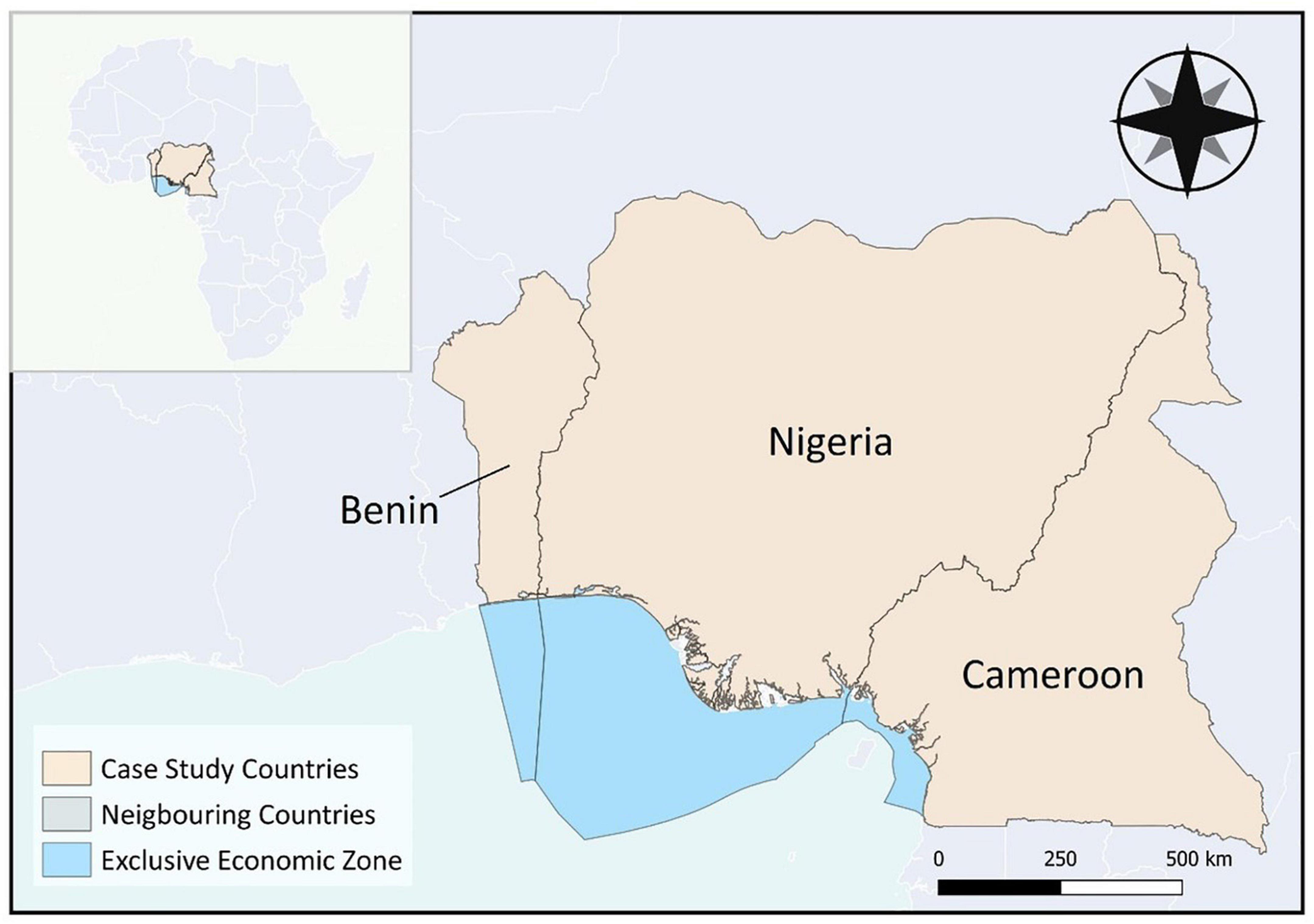

Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon are coastal states in the GCLME (see Figure 3) with an extensive coastline and maritime space, characterized by a high degree of biodiversity and resources, which provides the basis for a substantial proportion of economic and social activities (UNDP, 2013; Oribhabor, 2016; Rice and Rosenberg, 2016). With one of the shortest coastal strips in the region, Benin’s coastal zone comprises alluvia sand with a maximum depth of four meters with longitudinal depressions parallel to the coastline and swamps (Dossou and Gléhouenou-Dossou, 2007). Whereas, the barrier lagoon complex of Nigeria covers about 200 km from Benin/Nigeria border eastward to the western limit of transgressive mud beach and adjacent to the Gulf of Guinea (GoG) backed by the Badagry creek, Lagos Lagoon and Lekki, Lagoon (Amosu et al., 2012). Cameroon’s different coastal ecosystems are prevalent, including estuaries (in Rio-del-Rey, Cameroon, and Ntem estuaries), mangroves, lagoons, deltas, mud and sand flats, coastal shelves, etc. (UNESCO/IOC, 2020b). On the other hand, the south-eastern part of the coast presents an alternation of rocky and sandy beaches and cliffs (Fonteh et al., 2009).

Figure 3. Map of study area showing maritime jurisdictions (Data source: Flanders Marine Institute, 2019).

Mangrove swamps are the most biologically significant coastal ecosystems along these countries’ coasts (Asangwe, 2006; Fonteh et al., 2009; Amosu et al., 2012; UNDP, 2013), with strands reaching heights of up to 40 m (FAO, 2007). As it will be described in section “Maritime uses, activities and pressures,” these forests are now under severe pressure from anthropogenic activities, putting their ecosystem service roles and biological diversity at stake (Ukwe et al., 2006; Eke, 2015). Equally, several aquatic species are endangered due to unsustainable harvesting, oil pollution and habitat degradation (GCLME-RCU, 2006; Amosu et al., 2012). The severity of coastal erosion is high due to natural factors and habitat modification (Abessolo Ondoa et al., 2018; World Bank, 2019; Alves et al., 2020).

All three countries have since ratified the LOS—and like every other coastal state operating under UNCLOS, they are entitled to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles, including territorial waters and contiguous zones. The three countries have since promulgated legislations to delimit their EEZ in 1976, 1978, and 2000, respectively (see Table 1). Likewise, they have submitted applications to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf for an extension beyond the 200 nautical miles2. Meanwhile, the fierce maritime and land dispute between Nigeria and Cameroon (Nigeria Vs Cameroon: Equatorial Guinea Intervening) was put to rest on the 10 of October 2002, following the International Court of Justice’s grand judgment ruling in favor of Cameroon. It is interesting to note that the maritime jurisdictions of Benin, and Nigeria and Cameroon are recognized under various geographical contexts, including the greater Gulf of Guinea, GCLME, Southeast Atlantic, IHO Gulf of Guinea, and the Global International Water Assessment Region 42. Likewise, the maritime jurisdictions in the countries are found under different Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinate System Zones (Benin – 31N; Nigeria – 31N, 32N, 33N; and Cameroon – 32N, 33N).

The signing of UNCLOS marked the latest major international political step toward a universal regulation of the ocean. It has further jerked commitments at the political level in the GCLME, calling for a better understanding of the value and usefulness of the sea (Chatham House, 2013). However, Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon are all products of colonial imperialism and exhibit inherent political characteristics that generally influence governance, but with various distinctions. Suárez-de Vivero and Rodríguez Mateos (2014) sees these countries as post-colonial maritime states shaped after maritime empires and powers.

In terms of the internal political system, Benin is a presidential representative democratic republic, where the President is both head of state and government. The current political system is derived from the 1990 Constitution giving the president executive power, while legislative power is vested in the government and the legislature. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. Nigeria is structured as a federation, having a three-tier government (legislative, executive and judiciary). Under the 1999 constitutions, governance is carried out within three federating units (Federal, States, and local governments). Yet, power resides in the central government, which controls most of the country’s revenues and resources.

The political system in Cameroon is a republic multiparty presidential regime that is structured on the French model. Under this model, power is distributed among the President, the Prime Minister, and the Cabinet ministers appointed by the president as proposed by the prime minister, allowing the president to control whoever comes into power. Under this system, the Republic is divided into ten regions supervised by a Governor appointed by the president, who coordinates Divisional officers and subdivision officers.

Apart from the role the internal political framework plays in each jurisdiction’s maritime domain, various supranational bodies’ roles have become increasingly important in managing marine space. These bodies include the African Union, the Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS), the Economic Community of Central Africa States ECOWAS (ECCAS), Gulf of Guinea Commission (GGC), the United Nations Economic Commission for African (UNECA), etc.

Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon have a significant level of leisure-based coastal tourism with some beach and heritage-based interest. Ouidah, a coastal city in is the Voodoo religion’s birthplace endowed with ancient temples (E.g. the Python temple) and grooves where the Voodoo festival attracts thousands of tourists yearly (Forte, 2009). Even though coastal tourism is still developing in Nigeria, the proportion of tourism on the coast is expected to be high. The expectation is partly owing to the coastal location of cities like Lagos and Port Harcourt, sizeable coastal towns and linked communities on the outskirts of cities (e.g., Badagry); pleasant sites on creeks in the Niger Delta; strong historic heritage linked to the slave trade and cultural events, etc. Cameroon has a diverse product, with some beach-related accommodation and a vital element of cultural tourism, including key coastal historical sites with mountain and rainforest experiences. Kribi stands out as the prime leisure tourism destination.

Of all these uses of the coastal-marine area, perhaps the one which has the most significant economic and environmental impact is maritime transport. Generally, the GCLME naval space offers seemingly idyllic shipping conditions (Ali, 2015; Osinowo, 2015; Richardson, 2015). Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon are hosts to numerous natural harbors that are weather friendly to vessels and primarily devoid of chokepoints (Osinowo, 2015). This unique feature provides a medium where raw materials like timber, cocoa, coffee, cotton and finished goods are being traded with other parts. Port and shipping activities are critical to Nigeria and Cameroon as the significant GDP earning of both countries depends on the exportation of hydrocarbon (UNCTAD, 2020a p. 24). Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon are also open registry nations, registering 462, 10,882, and 448 ships respectively between 2011 and 2020 (UNCTAD, 2020b). However, besides the economic impact of maritime transport in the countries, there have been negative impacts. These include ship-based pollutants on the marine ecosystem (Onwuegbuchunam et al., 2017), coupled with security issues related to piracy and armed robbery at sea, which have escalated into a transboundary crisis (Ali, 2015; Eke, 2015; Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020). For example, the extent of environmental pollution in the Niger-Delta region of Nigeria, mainly due to oil and gas activities, is unprecedented and has affected the health of ecosystems and the livelihood of those who depend on them (Eke, 2015; Okafor-Yarwood, 2018).

The significance of the export of hydrocarbons to the national income stream cannot be underemphasized, particularly in Nigeria and Cameroon. Nigeria produces an estimate of 2,317,000 Billion Barrels of crude oil per day (BPD) with an offshore output in 2019 estimated at 780,000 barrels per day (BPD), amounting to 39 percent of the country’s total daily production (George, 2019). Cameroon received USD 1.152 billion revenue from extractive industry taxation in 2014, with 93.66% from upstream hydrocarbons, mainly from crude oil (EITI, 2020). Meanwhile, in Benin, oil and gas production stopped in the Sèmè field in 1998 with no further discovery. The Niger Delta of Nigeria, Kribi, and Limbe areas of Cameroon are prone to oil spills, destroying millions of people’s livelihoods (Tiafack et al., 2014; Amesty International, 2015; Okafor-Yarwood, 2018).

Although resources and capacities related to fisheries vary significantly between Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon, the sector has been vital to food and socio-economic security. Despite the lack of upwelling along Benin’s coastline limits marine resources, the annual harvest is estimated at 12,000 MT for fish and 4,000 MT for shrimp (FAO, 2015), and provide an opportunity for artisanal fishing with an estimated 50,000 canoes and a maritime artisanal fleet of 825 pirogues (WASSDA, 2008; FAO, 2015). Meanwhile, the fisheries sector in Nigeria directly employs an estimated 8.6 million people and another 19.6 million indirectly (WorldFish, 2017). Cameroon’s fisheries sector is crucial for socio-economic sustenance as it accounts for 1.8% of the country’s estimated US$35 billion GDP and employs more than 200,000 people (Beseng, 2019). Generally, the governments cannot monitor fisheries effort and catch, which often results in a lack of data, scientific knowledge and inadequate management (Chan et al., 2019). Fishery bycatch is not mostly reported, while other illegal activities such as illegal fishing, trans-shipment are significant problems (Belhabib and Pauly, 2015).

Undoubtedly, for a long time, mining renewable and non-renewable resources in the coastlines and seabeds of Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon contributes to the socio-economic development of coastal communities and substantial degradation of the marine ecosystem. Besides hydrocarbon exploration and mining, extraction of sand, gravel, rocks, sulfur and other construction materials both legally and illegally are ongoing, which has hitherto widely exacerbated land and coastal erosion (Ukwe et al., 2006). In Benin, illegal marine and beach sand mining thrive as sand diggers are paid between US$87 and US$125 per truckload—a value above Benin’s average monthly salary is less than US$50 (WACA, 2018). Large-scale sand mining along Nigeria’s coast raises concerns over erosion and other environmental damage (Aljazeera, 2014). Illegal and legal sand mining occurs in Cameroon, particularly around coastal cities and towns where industrial activity and construction are high, e.g., port development, land reclamation and housing construction, etc. (Asangwe, 2006; MINEP, 2011; Fotsi et al., 2019). All these puts together have exacerbated coastal erosion, habitat degradation and loss of livelihood (UNESCO/IOC, 2020b).

This section has identified the factors shaping ocean governance in the three case study countries, including biophysical maritime features, maritime jurisdiction, political framework, maritime uses, and associated ecosystem pressures. The next section of this paper examines the mechanisms, staged at the international, regional and national level, that would promote cooperative ocean governance. In addition, it is essential to ask what the enabling factors for cross-border ocean governance cooperation are in the GCLME from the lens of Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon.

This section is structured following Flannery et al. (2015) framework, which presents several important factors to measure the possibility of cross-border ocean governance. Flannery and his colleagues identify these factors to include policy convergence, the common conceptualization of planning issues, joint vision and strategic objectives, shared experience, and existing transboundary institutions. However, we categorize the factors into three broad elements, as presented and explained in Table 2 above. These elements allow us to examine the structures of operation, and deliberative mechanisms staged at international, regional and national levels that tend to promote or downplay cooperative ocean governance in the three case study countries and, by extension, in the GCLME. Also, the length of this section is extensive as it constitutes the core of our analysis

To a significant extent, Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon rely on several international policy architecture and commitments to guild ocean management and governance, bringing about convergence in ocean policies and strategies. Besides the promulgation of legislations to delimit their territorial sea, contiguous zone, and EEZs, the countries in 2009 and 2018 for instance, submitted an application to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to extend their Continental Shelves3 beyond the 200 nautical miles. Also, under UNCLOS’s limits of the Continental Shelf regime, Benin and Nigeria agreed in 2009 to commit to a ‘‘no objection note’’4 to cooperate on the boundary of their extended continental shelf.

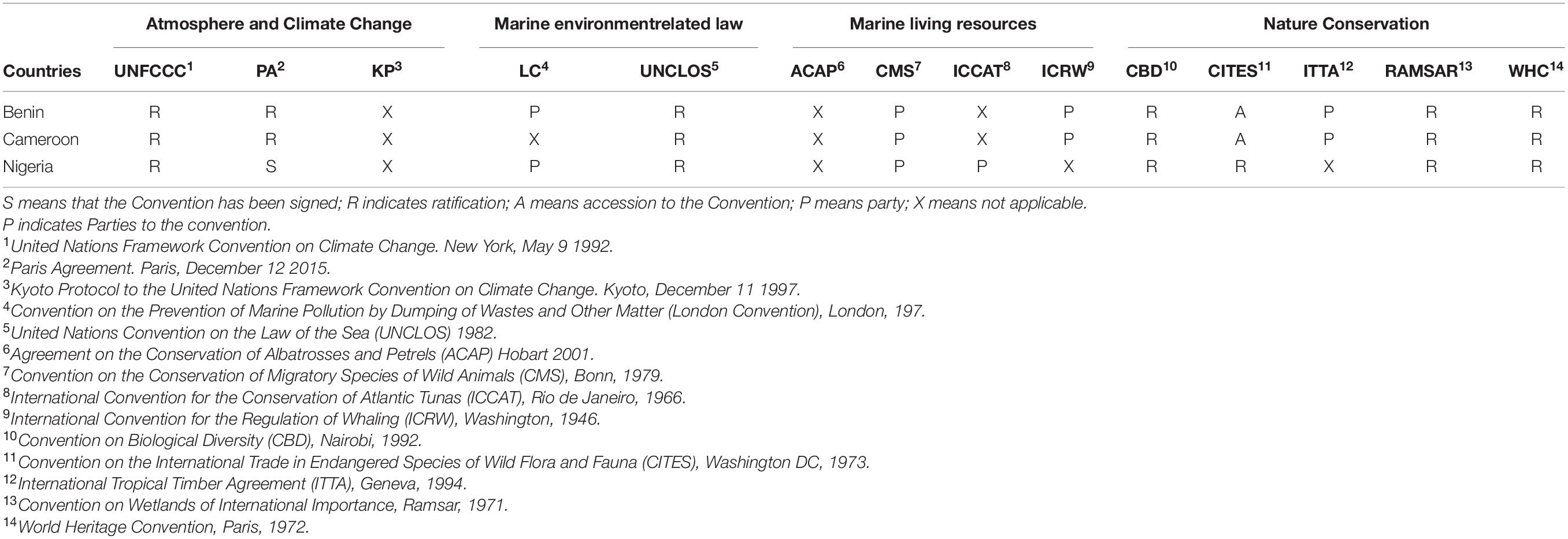

Similarly, being contracting parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), these jurisdictions must report the progress of biodiversity conservation under a common standard, ensuring they prepare a national biodiversity strategy that is expected to be mainstreamed into national conservation efforts. The same goes for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) of 1992, under which the three countries have developed similar but individual Climate Change Action policies and plans. The three jurisdictions are also working with the Paris Agreement to actualize the global climate change targets. Meanwhile, the acceptance and ratification of the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 currently suffer a significant setback, probably due to the countries’ progress anchoring on the UNFCC of 1992.

Agreements with international conventions and protocols governing aspects of maritime navigation and shipping seem to have brought a significant level of legal convergence in the three jurisdictions. Among the IMO conventions5 to which the three countries are, to various degrees, in compliance with, are the 1972 Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping Wastes and Other Matter (London Convention), International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 19736, Protocol for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts (SUA).

There is an average level of convergence on legal instruments in the three jurisdictions on ocean conservation matters, as several vital agreements and conventions have remained either unsigned, signed, or ratified. For instance, the 2001 Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels is not recognized in the countries. Still, they are parties to the 1979 Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals by the basis of ratification and accession. Meanwhile, out of the three jurisdictions, Nigeria happens to be the only country party to the 1966 International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Moreover, Benin and Cameroon have signed the MoU concerning the conservation of manatees and small cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia to complement the Bonn Convention on the flip side. The three countries have also ratified the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety.

Likewise, Benin and Cameroon are contracting parties to the International Tropical Timber Agreement (ITTA), Geneva, 1994, while Nigeria has not---possibly leaving Nigeria vulnerable to illegal logging of mangroves and other coastal timber species. The Ramsar Convention has also rallied the convergence of legal instruments in the three jurisdictions on coastal wetland conservation. At the same time, the ratification of the World Heritage Convention plays a significant role to protect a substantial number of heritage sites within their coastal zone are in alignment. Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon may gain from the recommendations of Article 4 of the European Union and the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP-EU) Agreement7 which acknowledges and recognizes the complementary role and potential for contributions of non-state actors in the development process.

Although countries in the case studies generally see values aligning with international commitments, complying and implementing some of these commitments is taking a back foot. For example, despite Benin and Cameroon being parties to International Tropical Timber Agreement (ITTA), Geneva, 1994, illegal logging in these countries are still happening at an accelerated rate (Cannon, 2015; Teka et al., 2019). See Table 3 for a summary of international conventions, protocols and agreements signed by countries in the case study.

Table 3. Summary of international conventions, protocols, and agreements signed by countries in the case study (Data source: Source: United Nations [UN], 2021).

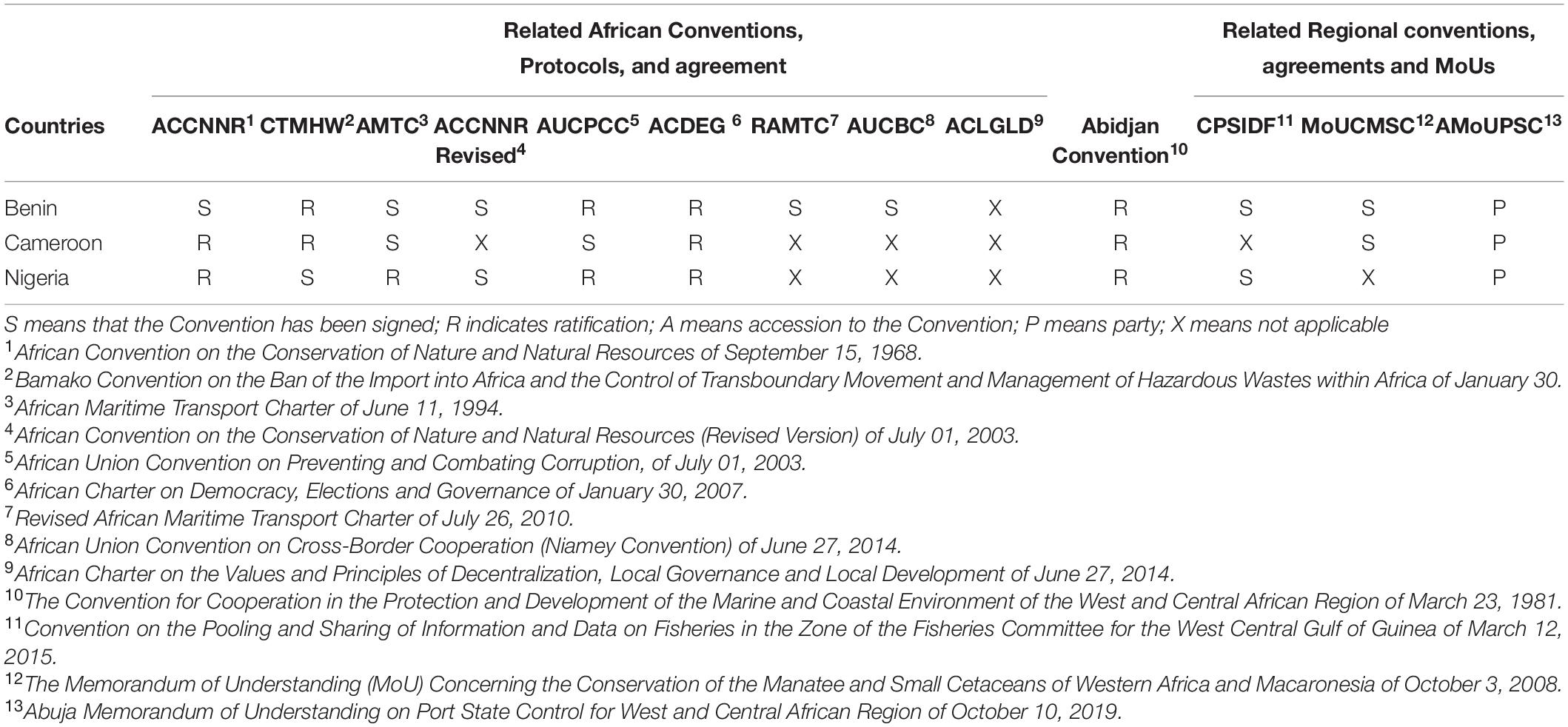

Due to the harmonization of several African and regional level policy instruments (including conventions, strategies, treaties and protocols), there is some degree of convergence of policy and legal frameworks between Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon (see Table 4). Besides promoting policy convergence, implementing several African Union (AU) conventions, protocols, treaties, and strategies emphasizes cooperation among the AU Member States. Nonetheless, the reactions of the three jurisdictions to these instruments varies significantly. The conservation of nature in Africa is within the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 19688 and its 2017 revised version. While Benin and Cameroon only signed it, Nigeria has ratified the convention, signifying the policy and legal framework convergence toward ocean conservation.

Table 4. Summary of Regional conventions, protocols, and agreements signed by Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon countries (Data source: African Union [AU], 2021).

Meanwhile, the formation of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) in 1985 has provided the necessary platform for environmental policy and legal framework convergence between Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon on multilateral environmental agreements. In its objectives toward enhancing governance mechanisms for ecosystem-based management of the African ocean, the AMCEN has repeatedly called on African countries to fulfill their ocean-related commitments. For instance, Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon are among the African countries through the AMCEN, which adopted 11 resolutions to accelerate action strengthen partnerships on marine litter microplastics at the third meeting of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) held in December 2017 in Nairobi (AMCEN, 2019).

There is no consistency in the jurisdictions’ commitment toward embracing African instruments concerning maritime transportation at different stages. The 1994 and 2010 versions of the African Maritime Transport Charter have low acceptance of accession and ratification. The Nigerian government has signed the 1994 version but has not acted on the 2010 version7. However, Benin and Cameroon have not reacted to either version of the Charter. The overall reaction of the Jurisdictions to this Convention shows absolute disregard of the jurisdictions’ responsible authorities toward the plight of maritime transport, especially when the region is wallowing in the dismal affront of maritime piracy and related vices.

There is a significant level of policy convergence on information and data sharing, particularly in Benin and Nigeria. They are signatories to the Convention on the pooling and sharing of information and Data on Fisheries in the Zone of the Fisheries Committee of the West Central Gulf of Guinea. With this Convention, the three countries adopted a set of strategic objectives to ensure consistency in fisheries data and information to aid collaboration, joint-fact finding and decision making. The Jurisdictions being parties to the Abidjan Convention9 allows them to work in tandem on coastal and marine issues, as the Convention provides the necessary platform for them to collaborate through the Conference of Party (CoP) and activities of the Focal Points. The Convention also commits the Jurisdictions to protect and manage their adjoining marine and coastal environment. Similarly, the Abuja Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control for the West & Central African Region also binds the countries to adhere to crew adequacy and vessels best maintenance incompliance with the requirements of international conventions, such as SOLAS, MARPOL, etc.

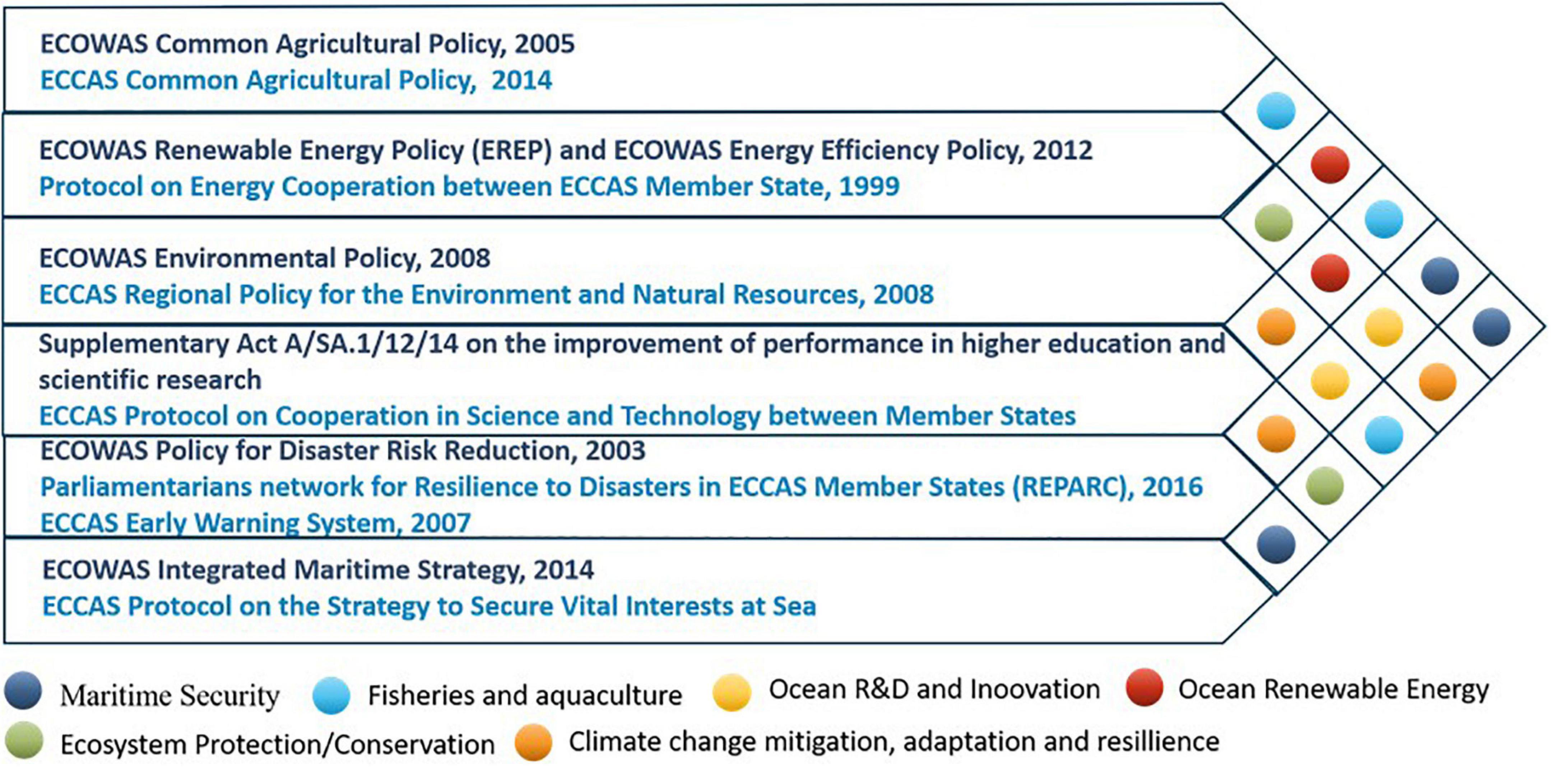

Since the 1970s and early 1980s, the topics for regional-scale policies, protocols and actions have developed in West and Central Africa, either paralleling global/African environmental protection instruments or considering characteristic sub-regional challenges. Several aligned policies and legislations are in operation to enhance joint management and governance of ocean space within and across the two sub-regions. These policies and legislations have aims and objectives that stresses the move toward more integrated approaches. They address cross-cutting challenges, including security, fisheries, conservation, climate change, research and development, ocean renewable energy, etc. (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Selected policies and legislations within ECOWAS and ECCAS with a matrix of their sector/activities convergence.

More recently, some integrated policies have taken on goals for a sustainable ocean environment. In the ECCAS sub-region, the 2009 ECCAS Protocol on the Strategy to Secure Vital Interests at Sea aims to protect natural resources and artisanal maritime fisheries zones maritime routes and fight against illicit naval activities (ECCAS, 2009). Similarly, in the ECOWAS sub-region, the Integrated Maritime Strategy follows the AU Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS). There is a convergence in these two instruments as both focus on maritime security and identify the maritime domain’s significant challenges and a set of comprehensive priority actions needed for a prosperous, safe and peaceful marine environment at the national and sub-regional level.

A convergence of policy approaches centered around an integrated regional maritime security architecture within the two sub-regions is also strongly noticeable. For example, the 2008 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on the Establishment of a Sub-regional Integrated Coast Guard Network in West and Central Africa signed by 14 Members of the Maritime Organization of West and Central Africa (MOWCA), laid down the framework to promote regional maritime cooperation, safety, law and order and surveillance for West and Central Africa (IMO/MOWCA, 2008). Additionally, the adoption of the 2013 Code of Conduct (CoC) concerning the repression of piracy, armed robbery against ships, and illicit maritime activity in West and Central Africa, also known as the Yaoundé CoC emphasises cooperation and information-sharing across the region as a panacea for addressing an array of maritime crimes.

On the environmental front, there are points of convergence between policies and plans in the ECCAS and ECOWAS sub-region on agriculture, environment, energy, research and development, etc. These policies and plans often have similar implementation strategies on management and governance objectives for coastal and marine spaces. For example, the ECOWAS Common Agricultural Policy adopted in 2005 includes two supplementary plans (Regional Agricultural Investment Plan and Food & Nutrition Security and the 2025 Strategic Policy Framework adopted 2016) with a high commitment to the maritime and continental fisheries/aquaculture sector. It promises to ensure a modern, competitive, inclusive, and sustainable fisheries sector to accelerate economic prosperity, guarantee decent jobs, and ensure food security (ECOWAS, 2017). Similarly, in the ECCAS sub-region, the 2014 Regional Common Agricultural Policy allowed reframing a set of strategies and programs (e.g., the Regional Program for Agricultural Investment, Food and Nutrition Security). Also, these two instruments’ strategies and plans have similar focus on several topics, including fisheries. For the fisheries sectors, they both envisage a modern, competitive, inclusive, and sustainable sector to accelerate economic prosperity, guarantee decent jobs, and ensure food security (PDDAA, 2017).

Developing national platforms for cooperation, promoting and expanding various early warning systems, coordination and harmonization, and supporting public awareness advocacy are significant issues of interest in the existing ECOWAS and ECCAS sub-regional policies. For instance, the ECOWAS Policy for Disaster Risk Reduction, adopted in 2006, focuses on reducing disaster risks through development interventions by managing disaster risks as a development challenge. In response to disaster risk, the Parliamentarians Network for Resilience to Disasters in Central Africa was inaugurated in 2016 by the ECCAS in a drive to curb the impact of natural and human-made hazards by implementing the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. These policies and actions are essential for the two sub-regions, given that climate change risks pose a particular threat to coastal communities from increased marine erosion, sea flooding, and landslides (UNESCO/IOC, 2020b).

Although some of the available policies and instruments acknowledge integrated resources management principles, their implementation does not abide by these principles in practice. Likewise, a look into some of the policy documents shows their limitation to goals concerning resource exploration/exploitation and control, projections of future demands, or more on the needs for the financing of developmental projects. For example, the ECOWAS Renewable Energy Policy (EREP) and Protocol on Energy Cooperation between ECCAS Member States did not address critical issues that bother socioeconomic justice, such as equitable energy distribution.

Despite some of their lapses, the presented policies and legislations in the two sub-regions are starting points in determining the need to revise current laws, promulgating ocean-related regulations, or taking other steps to implement ocean laws effectively. Also, they are necessary to catalyze the creation of new legislative and institutional arrangements that accommodate novel policy prescriptions as the policies are periodically revised.

Constitutions typically outline a broader set of pronouncements for which implementation mechanisms are less exact (Lijphart, 2004). It often needs to be translated into laws and policies to have a widespread impact on citizens’ lives. Constitutional provisions in Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon revealed mechanisms for the legal enforcement and fundamental building blocks of government and laws for ocean-related concerns. Their commitments remain relatively stable and permanent even as different political parties assume power, which can help guard against governments’ attempts to remove or weaken national coastal and marine management commitments.

Most of the recent sectoral laws on the countries’ environment are derived from colonial laws, specifically from early 20th century English and French laws. These laws primarily deal with natural resource extraction to facilitate exploitation more than protection (Kameri-Mbote and Cullet, 1997). Questions arise as to the capacity of these laws to deal with traditional health and natural resource problems, let alone deal with new issues and needs not contemplated when the laws were initially enacted. However, several critical legal instruments exist directly or indirectly to the countries’ management and control of coastal and maritime environments. As parties to UNCLOS, Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon have sovereign rights over their EEZ, including soil and subsoil of their extended continental shelf. Various legal instruments are in place in the countries following UNCLOS’s requirement for their Territorial Sea, Contiguous Zone and EEZ. Others bolster all aspects of sustainable development and align with objectives and goals for management on fisheries and aquaculture; conservation and environmental protection; coastal protection, waste management, land-use and development control; rural development. These legislations are in the form of Acts, Regulations, Orders, and Decrees, whose implications are clear if implemented and enforced correctly. After all, there are certain disadvantages of creating new coastal and marine management (including time-consuming, flexibility, undesired outcomes, and decreased political support) legislations, especially when considering Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) (IOC-UNESCO, 2009b).

Meanwhile, in the absence of a stand-alone national ocean policy in Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon some regulatory measures for managing coastal and marine resources are in place. These include issuing fishing, logging and mangrove harvesting permits, etc. – even though most of these have proven ineffective for various reasons (see, e.g., Ukwe and Ibe, 2010; Diop et al., 2012; Barnes-Dabban and Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, 2018). Increasingly, the countries are enacting sectoral policies that can provide practical frameworks at the national level to implement ecological standards and regulate socio-economic activities in the light of sustainable development objectives.

In Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon’s ocean domain, the numerous pieces of sectoral policies and enacted legislative instruments of governance are devised, administered and enforced by a wide range of formally established institutions. Most departments within central government ministries, statutory authorities, or cabinet appointed multi-sectoral steering committees to manage single or multiple facets of the ocean and coastal sphere. Though sectoral in approach, these institutional frameworks for governance and management of ocean activities and resources are comprehensive. Coastal and marine management is mostly saddled on the environment and transportation’s ministries with interwoven responsibilities for the three countries (see Table 5). Together with their various departments, the environment ministries oversee marine environmental protection, adherence to international, regional and national regulation and implementation of national policies and programs. In Nigeria, these institutions are also replicated at the state and local government levels and backed up by laws aligned with national legislation and policies. The ministry of transportation in Nigeria and Cameroon is responsible for activities that have to do with shipping, port development, and transportation. In Benin, this responsibility is carried out by the Ministry of Maritime Economic, with obligations mainly on transport and port infrastructure. Apart from the various government institutes and universities, the live wires of marine and coastal research and technical support are the the national institutes for oceanographic and marine research of the different countries. There are also some national NGOs serving as pressure groups to advance sustainable development.

Besides various spatial and territorial planning instruments in the case studies, there are few dedicated national legal frameworks for ICZM. Decree No. 86-516 of 1986 defining responsibilities for coastal management and law No 2018-10 of the 2 of July 2018, on the protection, development and theft of the coastal zone in Benin are in place to guide the ICZM process, with a proposition of inter-ministerial participation. In Nigeria, the National Coastal and Marine Area Protection Regulations, 2011 (S.I. No. 18 of 2011) and the National Wetlands, Riverbanks and Lake Shores Protection Regulations, 2009 (S.I. No. 26 of 2009) gives the Federal Ministry of Environment the coordination responsibility to develop and implement ICZM. However, there are existing comprehensive policies to realize ICZM at the national and regional levels in Cameroon. These include the National Action Plan (NAP) for Marine and Coastal Area Management (November 2010), the Management Plan of the Campo Ma’an National Park, and Kribi Campo Coastal Zone Management for Sustainable Tourism Development.

Concerning MSP, a mismatch of ministries has related competencies in the three countries. Based on several legal and essential institutional tools, developing and implementing MSP lies in an inter-ministerial arrangement. There exist several overlaps in mandates related to marine protection, development and administration. In the three countries, the inter-ministerial arrangement involves ministries responsible for the:

- Management and protection of inland waters, prevention of pollution and the protection of the sea and coastal.

- Spatial and physical planning.

- National Defence; Ministry of Urban Development, Land Reform & Erosion Prevention; and Ministry of Transport the three countries.

- Infrastructure, transport and management of maritime properties of national interest.

- Coordination of policies on food, forestry, aquaculture and fisheries.

Besides countries’ constitutions in the case studies, various high-level national policies are the basis for Blue Economy development (see Table 5). For example, the National Development Plan 2018-2025 of Benin has one of its objectives “to make agro-industry and services the engine of inclusive and sustainable economic growth within the framework of more effective national and local governance by focusing on the development of human capital and infrastructure.” This it plans to achieve by consolidating the rule of law and good governance; ensuring the sustainable management of the living environment, the environment, and the emergence of regional development poles; sustainably increasing the Beninese economy’s productivity and competitiveness healthy, competent and competitive human capital.

With the eradication of poverty expected to be at its center, the Nigerian Medium-Term National Development Plan 2021–2025 and 2026–2030, which is currently under preparation, would invariable aid the realization of the Blue Economy in the country.

Meanwhile, the prospect for the Blue Economy development in Cameron aligns with the expectations of the Vision 2035 Plan and the National Development Strategy 2020–2030. These two strategic documents highlight Cameroon’s overall policy direction and developmental pursuit, focusing on poverty reduction, becoming a middle-income country; industrialization, consolidating democracy and enhancing national unity.

Several strategic projects and programs have set the foundation for developing transboundary ocean science capacities between Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, and beyond. For example, the Global Environment Facility financed GCLME program introduced the countries and others to the ecosystem-based approach for marine goods and services assessment and management (GCLME-RCU, 2006). The program commits the GCLME countries to conduct transboundary marine resources assessments and support resource recovery and sustainability actions. Another important project that brought Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon together is the Monitoring of the Environment for Security in Africa (MESA) project implemented through ECOWAS and ECCAS. By providing information to relevant agencies using Earth Observation data and information products, the project helps the countries to work together to enhance coastal monitoring, improve fishery management and reduce illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing practices. Under the Ocean Data and Information Network for Africa (ODINAFRICA) project initiated by UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon have been working on ocean science and observation since 2011 (IOC-UNESCO, 2009a). The National Oceanographic Data Centre (NDC) in Nigeria coordinates Benin, Cameroon and other NDCs in the region (IOC-UNESCO, 2010).

Similarly, several projects aim to strengthen national and regional action through knitted activities and integrated approaches to accelerating integrated coastal and marine management in the three countries and beyond. This includes the Mami Wata transboundary project, which has built technical and institutional capacity for marine ecosystem-based using integrated Ocean Management frameworks, including MSP. Also, the two phases of the World Bank’s West Africa Coastal Areas Management Program (WACA) have improved countries’ capacities to manage their growing coastal erosion and flooding problems and access expertise and finance to manage their coastal areas (World Bank, 2016). The “Enhancing Adaptation and Resilience against multi-hazards along West Africa’s Coasts (EARWAC)” is a recent project supported by the European Space Agency and Future Earth and developed by The Sixth Avis Ltd, which presents an interactive dashboard (https://earwac.com/). The dashboard is built using long-term climate records derived from Earth Observation (EO) and other sources, allowing 10 West African countries (including Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon) to understand better, prepare for, monitor, and manage coastal degradation and hazards.

Historically, the Nigeria–Benin and Nigeria–Cameroon relationship has been that based on cultural and socio-economic nerves. Coastal communities in the three countries have similar ethnological composition and culture (Familigba and Ojo, 2013; Mark, 2015). For example, the Badagry division’s people are mainly the Egun-speaking people with a direct cultural affinity with the Aja-speaking people of Benin, ditto, the Ewes in Benin and Nigeria. The language, culture and traditional administration of the people on either side of the border are identical. Similarly, the same ethnocultural stock is on both sides of the ostensible international divide between Nigeria and Cameroon (Edung, 2015; Nwokolo, 2020). The Ibibio, Efik, Ekoi, some Bantu and semi-Bantu people are the five original ethnic groups that settled at the boundary area (Njoku, 2012; see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Map showing the coastal communities in Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon cultural and ethnic affinity (Data source: Weidmann et al., 2010).

Likewise, these three jurisdictions were among African countries affected by this colonial division between British and French rule (Omede, 2006). However, despite different western powers colonizing the countries, long-standing bilateral relations between Nigeria–Benin and Nigeria–Cameroon persist post-independence. The three countries have signed many bilateral agreements (in pair – Nigeria–Benin and Nigeria–Cameroon) relevant to ocean governance (see Tables 6, 7).

To fight maritime piracy, Nigeria and Benin in 2011 set up the Operation Prosperity initiative, the first of its kind in the region, aimed at a combined maritime patrol of their waters.

Similarly, peace, environmental, socio-economic development, and other partnership forces are creating interlinked and overlapping identities that influence the form and function of the relationship between Nigeria and Cameroon. Several bilateral agreements have been signed between both countries, which governs their relationships (see Table 6).

The impression from the historical relationship and bilateral agreements/cooperation in these three Jurisdictions is that the relationship between the Benin and Nigeria seems more effortless than that of Nigeria-Cameroon for several reasons. Firstly, cordial symbiotic relationship between two ethnic stocks (Ewe, Yoruba, Egun) found between the coastal boundary of Benin and Nigeria are well established till today (Babatunde, 2014). However, the same cannot be said of the Ibibio, Efik, Ekoi, and Tivs people found between the Nigeria--Cameroonian border. The implication of this to coastal and marine management is that the ease of communication and cultural acceptance that cross-border management and governance initiatives will gain with stakeholders between Benin and Nigeria would be more than that of Nigeria--Cameroon. Secondly, the fierce maritime and land dispute10 between Nigeria and Cameroon has brought about a certain level of animosity between governments and people at the two divides even though the dispute has been settled since 2002 (Kadagi et al., 2020). Confrontations between the military, fishers, and people from Nigeria and Cameroon, particularly in the Bakassi Peninsula axis, are still periodic (BBC, 2017).

Following Flannery et al. (2015) analytical framework, this section so far has focused on examine the factors that shape ocean governance in the three case study countries, including policy convergence, the common conceptualization of planning issues, joint vision and strategic objectives, and shared experience. The following section will explore the potential of existing transboundary organizations in the GCLME to impact cross-boundary ocean governance cooperation using Kidd and McGowan’s (2013) ladder of transnational partnership as an analytical framework.

In this section, the nature of selected existing institutions with cross-border mandates in the GCLME and their capacity to foster transboundary cooperation toward sustainable coastal and marine management is analyzed using Kidd and McGowan’s (2013) ladder of transnational partnership, is used to examine (see Table 4). As described in section “Materials and Methods,” the ladder uses five ‘rungs’ to describe the different partnership categories, with informal partnerships at the bottom and more formalized partnerships on top. The analysis focuses on organizations in four key marine sectors, maritime security, fisheries, port and shipping, conservation and ecosystem-based management. These policy domains are selected for analysis because they represent critical sectors of activity and aspects in the GCLME and in the Jurisdictions understudy, and are likely areas of interest for cross-border ocean governance.

The signing of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct in 2013 led to the formation of the Interregional Coordination Centre (ICC) based in Yaoundé, Cameroon. The center coordinates the Regional Centre for maritime Security in Central Africa (CREAMAC) located in Pointe-Noire, the Republic of Congo for the Central Africa Region, and the Regional Coordination Centre for Maritime Security in West Africa (CRESMAO) based in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. Strengthening the cooperation, coordination, mutualization and interoperability of resources while ensuring maritime safety and security in the West and Central Africa region is the principal role of this center. These roles make the ICC correspond to Kidd and McGowan’s description of a “Combined Organization” and “Administration sharing.” Besides playing a prominent role in the emergence of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, Member States of the GGC consults with each other and cooperate on preventing, managing and resolving conflicts that may include maritime border delimitation, exploitation of resources with their EEZs. The GCC would therefore occupy the “Combined Organization” rung on the Kidd and McGowan’s ladder. For the Northwest Africa Maritime Safety and Security Agency (NWAMSA), the provision of scientific and intelligence assistance to the Member States and other Maritime Stakeholders on issues relating to the safe, secure and clean movement of maritime transport and the prevention of the loss of human lives at sea is its primary mission. Three iterations of the NWAMSA Work Plan (2008, 2009/2010, and 2011) developed a communication system and outline plan, harmonized methodologies for analytical purposes and information sharing, and a common information-sharing platform (NWAMSA, 2008). Following Kidd and McGowan’s ladder, NWMSA would sit on the “Information Sharing” rung.

Following approval for its establishment by the directors of fisheries in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria and Togo in 2006, and the 2007 approval of the Ministers of Fisheries establishing its Convention and the Rules of Procedure establishing, the Committee of Fisheries for the West Central (FCWC) of the Gulf of Guinea (FCWC) being working to promote regional integration through practical implementation of sound fisheries initiatives. The FCWC increased its commitment to transboundary fisheries management by recently conveying the West Africa Task Force composed of representatives from its six Member States to stop illegal fishing activities and trade. Rule 15 of the FCWC’s Rules of Procedure leaves the final decision-making power in the hands of the Conference of Ministers (Adewumi, 2020a). The FCWC would thus sit at the highest rung, ‘‘Combined Constitutions,’’ and could also pass as ‘‘Agreed Joint Rule’’ on the Kidd and McGowan’s ladder. Another organization of note relevant for the fisheries is the Ministerial Conference on fisheries cooperation among African States bordering the Atlantic Ocean (ATLAFCO), an intergovernmental organization founded in 1989 with 22 Member States covering from Morocco to Namibia. Cooperation between its Member States is fostered through two instruments: (1) the Constitutive Convention11, which sets out the areas and modalities of Regional Fisheries Cooperation, and (2) the institutional Framework Protocol, which commits the States to actively cooperate to the sustainable management of fisheries in the region. With these instruments, ATLAFCO promotes cooperation develops coordination and harmonization of Member States’ efforts and capabilities to manage fisheries resources. Member States exerts rights to influence decision making through nominees to the different ordinary and extraordinary sessions, a position mandated by ATLAFCO’s general rules of procedure. Through the regional professional and institutional networks in the fisheries sector established by ATLAFCO, states also share a common platform to work together on issues of mutual concern. The modus operandi and responsibilities of ATLAFCO indicate that it rightly fits the “Combined Organization” and “Agreed Joint Rule” rung on the Kidd and McGawan’s ladder.

The port and shipping sector in the GCLME provides a significant advantage for socio-economic development and the potential for the region to realize its growth ambition. Institutions and agencies with maritime administration mandate in the region are aware of this potential and engage in various transboundary cooperation forms. For example, the Maritime Organisation for the West and Central Africa (MOWCA)12 unifies 25 countries on the West and Central African shipping range and offers a platform to cooperate on maritime security and environmental safety security. Its 2008–2010 Action Plan and 2011–2013 program saw the adoption of processes for information sharing, formation of collaborative projects, and building strategic networks by the Assembly of Ministers of Transport of Member States. The coordination responsibility of MOWCA also extends to the Port Management Association of West and Central Africa, the Union of African Shippers Councils, and the Association of African Shipping Lines, three specialized units governed its mechanisms. Therefore, MOWCA’s position on the Kidd and McGowan’s ladder would be between “Information Sharing” and “Joint Administration.”

Taking a holistic view of the region in terms of geography, ecosystem and governance, the Abidjan Convention stands as the regional legally binding institution for coastal and marine conservation and management within Central and West African and beyond. Through its Conference of Party and Secretariat, the role of the Abidjan Convention is to develop consultation, co-operation and actions within its jurisdiction on coastal and marine matters. The Party States have jointly signed several important protocols to the Convention, making it a critical regional platform influencing coastal and marine policies at the national level (Adewumi, 2020b). With this, the Abidjan Convention correspond to Kidd and McGowan’s description of a “Combined Constitution” and “Combined Organization.”

The introduction of the Monitoring for Environment and Security in Africa (MESA) under the Global Monitoring for Environment and Security and Africa (GMES and Africa) initiative13 has strengthened partnerships between countries through two specialized technical institutions in the GCLME. These are the International Commission for Congo-Oubangui-Sangha Basin (CICOS) for the Central Africa sub-region and the ECOWAS Coastal and Marine Resources Management Centre (ECOMARINE) for the West African sub-region. With the coordination of CICOS and CECOMARINE, relevant national agencies are committed to sharing and receiving earth observation data from the satellite to enhance their early warning system on ocean conditions, thereby helping make informed conservation and management decisions. For example, a dedicated interactive web-based platform allows both users and ECOMARINE to provide information to relevant agencies in the region to enhancing coastal monitoring and improve fishery management. Likewise, CICOS has developed consolidated operational applications to monitor water heights for river navigation and the dynamics of the wetlands, thereby increasing data, knowledge and access to information for natural resources management. The commitment of these institutions to support conservation efforts in the region implies they fulfill criteria for “Information Sharing” on the Kidd and McGowan ladder.

The GCLME program has offered significant background and knowledge for implementing ecosystem-based management for the maritime domain in the region. It gave credence to the Interim Guinea Current Commission (IGCC), established in 2006 by the Abuja Ministerial Declaration for leadership and coordination of the GCLME Projects. The success of the IGCC has generated some new momentum to establish a permanent Guinea Current Commission (GCC) to oversee the sustainable development of the GCLME. Besides the financial and technical support from the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the World Bank, UNEP, UNDP, UNIDO, FAO, etc., solid political buy-in from ministers of the 16 participating countries and an array of top-notch scientists and professionals from the region with extant experience in the LME approach, the emerging GCC is poised to enhance integrated management of the GCLME region. Correspondingly, a new “protocol” has been decided at the 2nd Ministerial Meeting of the Abidjan Convention to support ecosystem-based assessment and management practices for sustainable development of the GCLME through the proposed GCC (Abe and Brown, 2020). The proposed GCC will occupy the “Combined Constitution” and “Combine Organization” rung by Kidd and McGowan ladder.

The second column on the table, “Function of cooperation,” follows Glasbergen (2011) and helps us better understand the heuristic of the ocean cooperation development processes in the GCLME in terms of critical issues. In this context, the coming together of stakeholders from different countries to resolve particular or complex marine challenges and realize opportunities reflects a functional image of “joint conceptualization” and partnership for ocean governance. The highest point of this partnership function is “Changing political order” while the lowest being “Building trust, understanding capacity.” Table 8 shows that one of the steps to achieving cross-border cooperation for ocean governance in the GCLME is to have a basis for collaborative interactions between various stakeholder institutions across borders in an atmosphere of mutual trust. Organizations such as MOWCA, FCWC, PMAWCA, CICOS, and ECOMARINE have built both internal and external trust, thereby guaranteeing positive intentions of national institutions, their capacity to contribute and reaction to broader ocean governance cooperation. These organizations provide an atmosphere for ocean governance cooperation to foster because national institutions would have been used to (1) operating in a system where coastal and marine-related information is shared, and (2) partnership working where the primary goal is the creation of comparative value for sustainable ocean development beyond the material interest of one single country.

Values and mechanisms exhibited by transboundary organizations like MOWCA, PMAWCA, Union of African Shippers Councils, Association of African Shipping Lines, and ICC provide a basis for participating countries to explore how they work together, find common ground, and distribute opportunities and risks for ocean governance. They captures the potential for collaborative advantage for ocean governance, which could not be achieved by any of the GCLME countries working alone. In other words, participating countries can connect their ocean interest with the common objectives across the GCLME.

The joint rule system practiced by transboundary organizations such as FCWC and ATLAFCO is a tool for coordinating and resolving unforeseen contingencies. Therefore, they are, thus, capable of advancing cross-border ocean cooperation in the GCLME based on trust-building and achieving collaborative advantage. Although not legally binding, the system indicates that the rights of participating countries are covered, duties are well articulated, and there are implementation and evaluation mechanisms. It, therefore, constitutes a shared system that motivates participating countries to (1) build cross-border ocean governance cooperation and develop areas of joint working and common practice, (2) develop a coordinated approach to major cross-boundary development issues, and (3) facilitate a coordinated approach to international/regional/sub-regional obligations.

Mainstreaming cross-border ocean governance cooperation in the GCLME would mean that forms of partnership that build trust, create collaborative advantage and shared system functions are implemented on a broader scale. At this scale, cross-border ocean governance cooperation implies transcending beyond a single ocean policy area or sector to an integrated ocean governance structure that countries associate with while changing institutions order. Transboundary institutions such as the proposed Guinea Current Commission, the Abidjan Convention, FCWC, ICC, and ATLAFCO are examples of organizations that can be leveraged to achieve this type of cooperation. This is because they (1) have the legitimacy to influence how their Party States manage and govern their maritime domain, and (2) will manifest themselves in the political sphere of ocean governance actions and structure in the GCLME.

With the diversity, dynamism and complexities of the maritime domain in the GCLME, cross-border ocean governance cooperation will not only be fostered based on their merit but a more significant societal, political order. With transboundary institutions like the Abidjan Convention and the proposed GCC, ocean governance cooperation in the GCLME has undoubtedly become part of the networks that govern the society, as political power has become disperse among the Party States. As such, cross-border ocean governance cooperation from the perspective of these organizations is seen as a new political space where stakeholders come together for negotiations and deliberate on ocean issues and decide concerted action of change.

The GCLME is a highly biodiverse marine area endowed with enormous marine resources that are important for livelihood sustenance and provide significant sources of governments’ GDP earnings. However, anthropogenic and natural factors pose considerable threats to the marine environment, reducing its capacity to continue performing its ecosystem services. A look at the GCLME through the lens of Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon provides an opportunity to examine the dynamics of ocean governance mechanisms in the region and reveal challenges and opportunities for a cross-bother ocean governance cooperation. The geopolitical characterization underpinning ocean governance in the region is brought to the fore by highlighting factors that drive ocean governance, including geographical features, maritime jurisdictions, political framework, maritime framework activities, and associated pressures.

The paper further assessed the key enabling factors for transboundary planning and governance in the GCLME from the perspective of the selected case studies, looking at how (i) ocean-related instruments from international to national scales bring convergence of policies at the country level, and (ii) shared experiences, common issues and joint solutions. The convergence in policy and legislative arrangements across borders will be of utmost importance and a prime contributor to successful transboundary governance of the ocean space (Flannery et al., 2014). Strong policy convergence in maritime boundary delimitation, security and safety, and climate change adaptation and resilience are evident from commitments to various international governance mechanisms like UNCLOS, IMO, UNFCC, etc. In contrast, there is a limited policy convergence on conservation issues from obligations to international level environmental mechanisms. Meanwhile, implementing several AU and sub-regional level environmental instruments and commitment, including arrangements such as AMCEN, Abidjan Convention, and the FCWC promotes policy convergence on ocean protection, conservation, integrated resource management and data sharing in the region. Policy convergence is also visible through various ECOWAS and ECCAS instruments on maritime security, disaster early warning system, fisheries and energy. Although a dedicated national ocean governance policy does not exist so far in the countries under study, government institutions and legal instruments are necessary to galvanize ocean governance and administration. In most cases, ocean governance competencies are usually within the federal or central government’s extant powers, depending on government operations in the countries. In Nigeria for instance, the overall responsibility for ocean governance, ICZM, MSP, and the Blue Economic rest on the federal government’s shoulders through various competent ministries.