- 1Tristan da Cunha Government, Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, Tristan da Cunha

- 2Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science, Lowestoft, United Kingdom

- 3School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

- 4Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Sandy, United Kingdom

- 5Marine Section, Environment, Natural Resources and Planning Directorate, St Helena Government, Jamestown, Saint Helena

- 6British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, Cambridge, United Kingdom

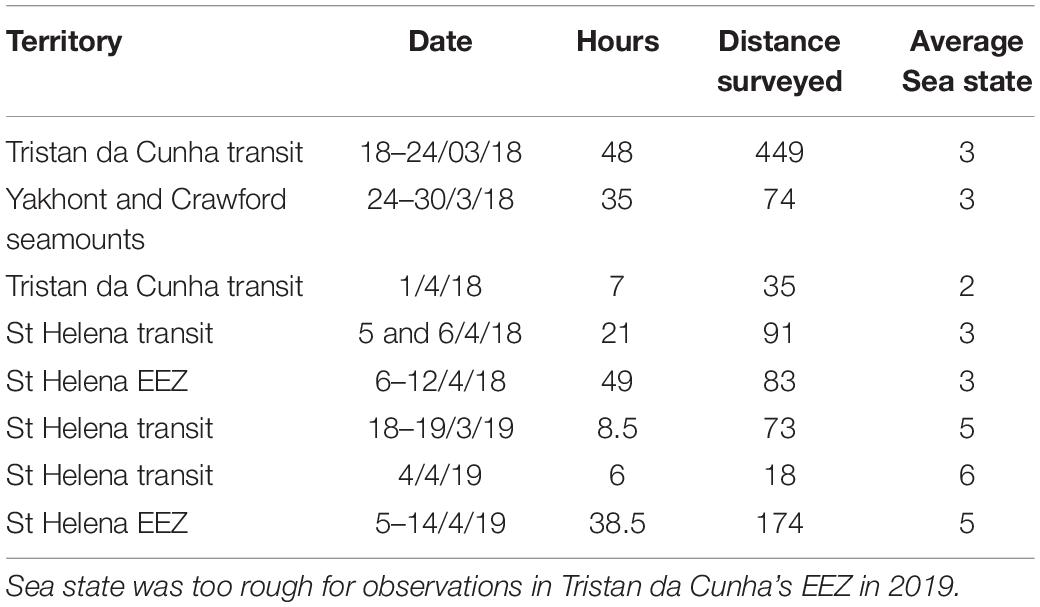

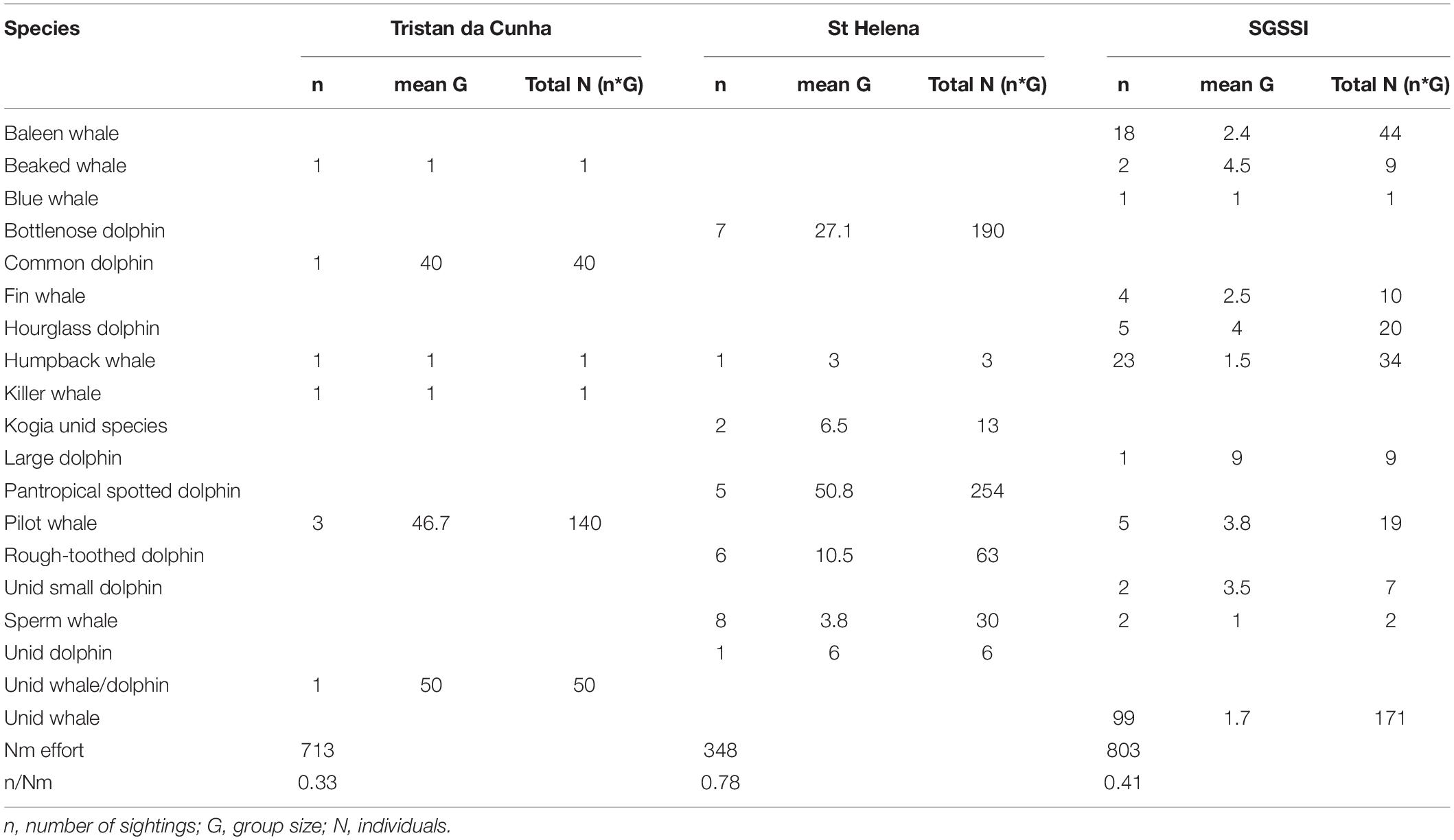

Marine mammal sightings were recorded during research cruises to three remote, mid-ocean British Overseas Territories in the South Atlantic and Southern Ocean. In March to April 2018 and 2019, the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of tropical St Helena and temperate Tristan da Cunha were surveyed. The sub-polar waters of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI) were surveyed in February to March 2019. At St Helena in 2018, five species were recorded during 11 sightings, and in 2019, four species, with one additional unidentified species, during seven sightings. Most of these sightings were of dolphin species, which are known to be resident around the Island and seamounts. In Tristan da Cunha in 2018, a total of five identified and one unidentified species were recorded during six sightings, half of which were associated with the Islands or seamounts. In 2019, due to rough weather, no sightings were recorded in the Tristan da Cunha waters. Around SGSSI, 162 sightings of 236 cetaceans were made in 2019, mostly of baleen whales, with seven species identified with certainty. Sightings around the southern South Sandwich Islands included beaked whales and large dolphins, whereas baleen whales dominated in the northern South Sandwich Islands. These results provide new data for rarely surveyed regions, helping to build a spatial picture of important areas for marine mammals, which will help inform marine spatial protection strategies.

Introduction

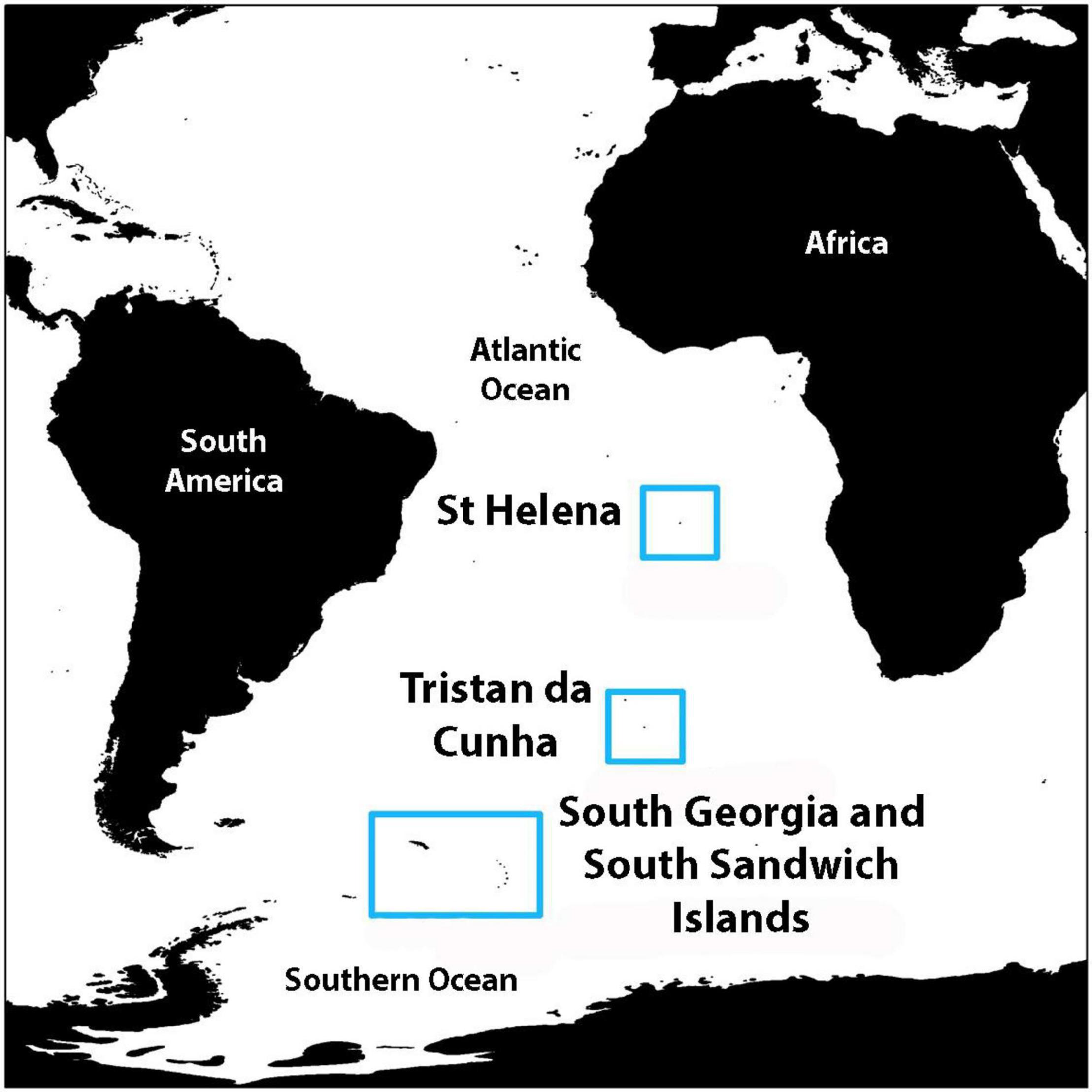

The remote British Overseas Territories in the South Atlantic (St Helena and Tristan da Cunha) and in the Southern Ocean (South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands - SGSSI) span the global migration routes of cetaceans, from tropical breeding to polar feeding grounds (Figure 1). The exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of these territories also provide habitat for resident cetacean populations. However, due to their remoteness the lack of, or limited data, makes it difficult to assess cetacean populations within these territories and how they have changed since or recovered from historical whaling (Best et al., 2009). St Helena is tropical with one main Island (12–19°S), while Tristan da Cunha is further south and spans the sub-tropical convergence (33–43°S) with three main Islands in the northern group and Gough Island to the south. The territory of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI) is within the Southern Ocean. The main island of South Georgia is at the northern limit of the Southern Ocean (54°S) while the island archipelago of the South Sandwich Islands is located further south (56–59°S); both lie within the Scotia Sea and due to their position receive strong advective flow of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). The southern South Sandwich Islands regularly experience seasonal sea-ice cover in the austral winter (Trathan et al., 2014).

Figure 1. Survey locations in three Atlantic British Overseas Territories in 2018 and 2019: tropical region around St Helena, temperate region around Tristan da Cunha, and sub-polar region around South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands. Boxes indicate the locations of the territories.

Despite their different climate zones, all three territories are characterized by deep oceans with steep-sided volcanic seamounts and guyots rising from the deep ocean floor (Makler and de Matos Mello, 2007; Geissler et al., 2020); only the island of South Georgia has a significant area of shelf shallower than 700m deep distinguishing it from the rest of SGSSI (Hogg et al., 2016) and the Atlantic territories. The seamounts and shelf breaks provide upwelling areas of productivity, supporting a rich food chain that includes many cetacean species (MacLeod and Bennett, 2007; Rossi-Santos et al., 2007; Best et al., 2009; Calderan et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020). An understanding of which areas within the exclusive economic zones are key regions for biodiversity, the “biodiversity hotspots” (Hogg et al., 2016; Requena et al., 2020), is required to inform management decisions. The maritime zones of St Helena and Tristan da Cunha territories are economically and culturally important to the Islanders, and all three territories have spatial marine protection, with a mixture of closed and sustainable use zones. The Governments of these three territories have signed up to the United Kingdom Government’s Blue Belt Programme to further develop their marine protection zones and management strategies. The jointly funded Blue Belt and UKRI funded British Antarctic Survey cruises visited St Helena and Tristan da Cunha in the austral autumn of 2018 and 2019. The Blue Belt Programme further funded a survey of the South Sandwich Islands in austral autumn 2019. During these surveys, cetacean observations were conducted to provide up to date information on cetacean species within these three rarely surveyed Atlantic overseas territories with the aim that this new data will feed into marine spatial planning and management.

Materials and Methods

Surveys

The remote British Overseas Territories of St Helena and Tristan da Cunha, in the South Atlantic, and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, in the Southern Ocean, were surveyed during research cruises on the RRS James Clark Ross (JR17-004; Morley et al., 2018) in Tristan da Cunha’s and St Helena’s EEZs (23 March – 1 April and 5–12 April 2018 respectively).

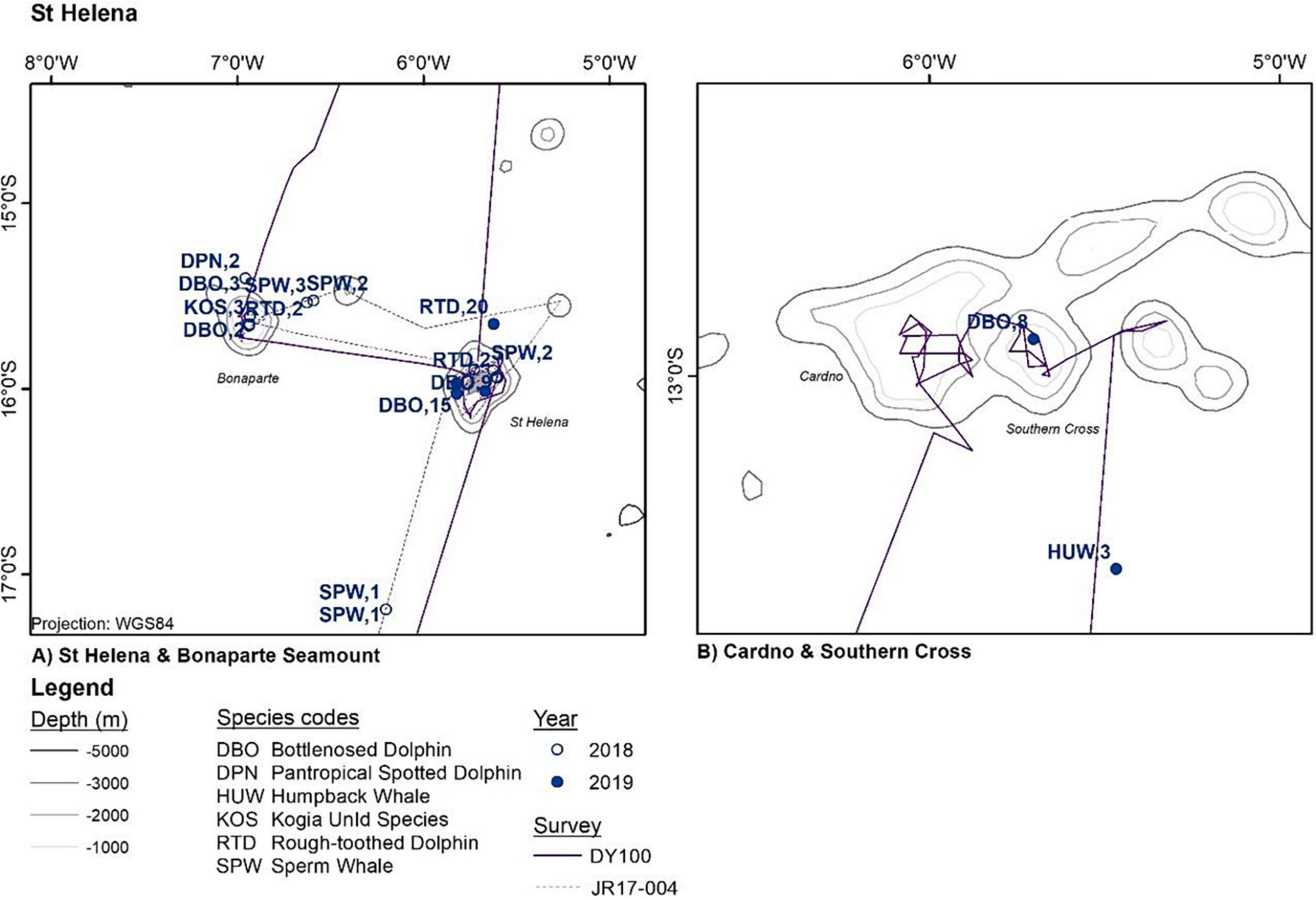

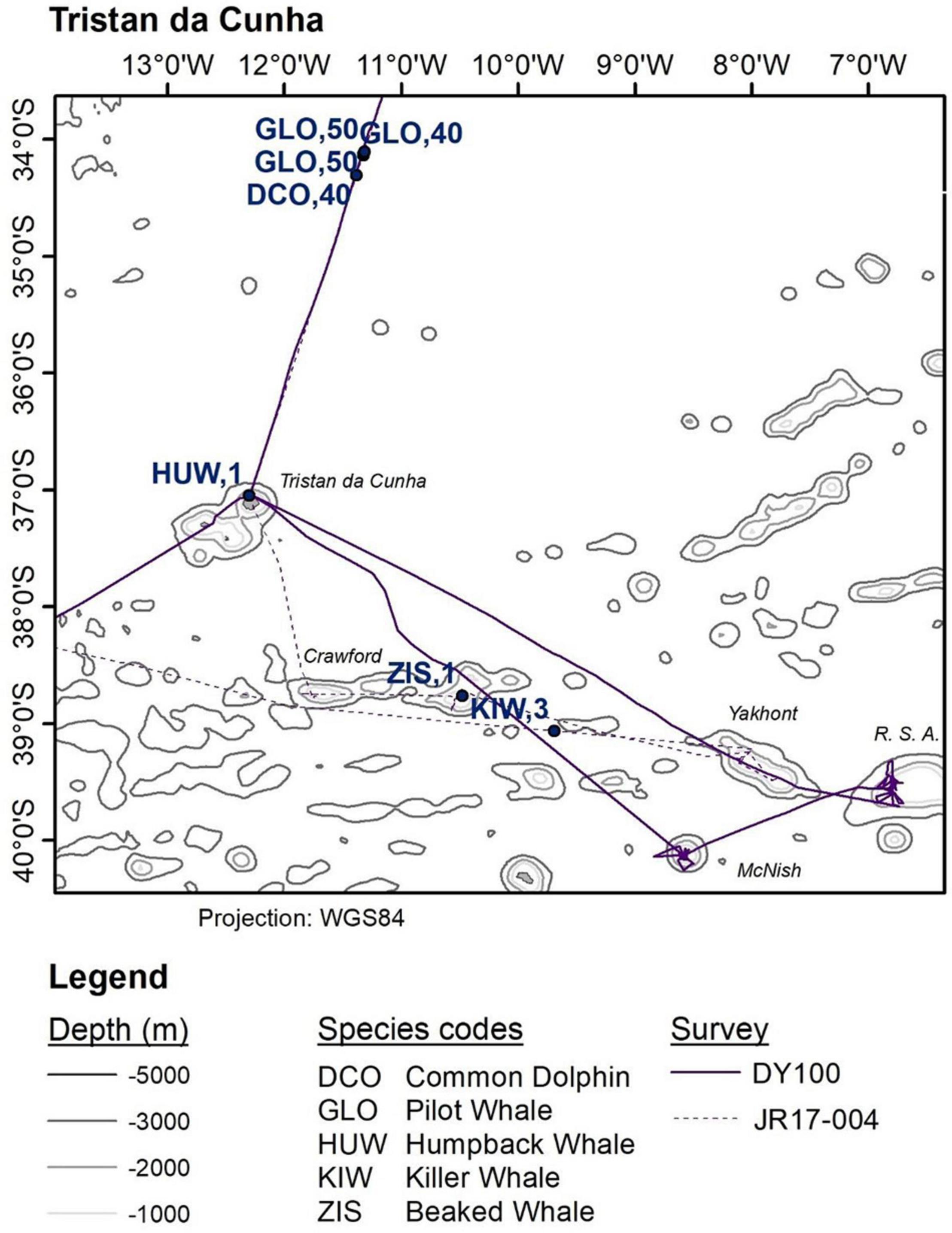

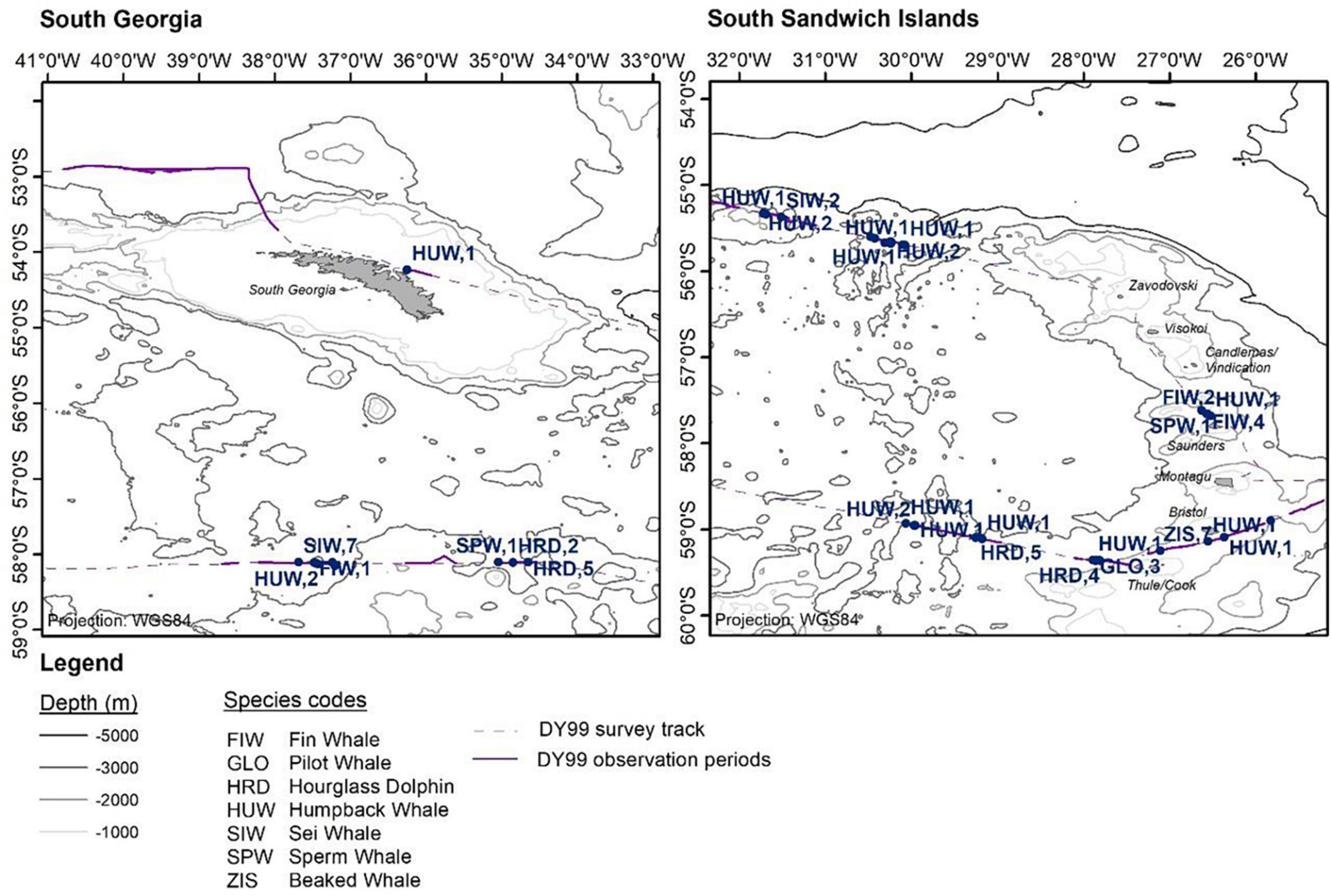

In 2019, surveys were on the RRS Discovery in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (14th February – 10th March; DY99; Darby et al., In Prep.), Tristan da Cunha’s EEZ (21–31 March; DY100; Whomersley et al., 2019) and in St Helena’s EEZ (5–14 April; DY100). Survey tracks are shown in Figures 2A,B, 3.

Figure 2. Cetacean sightings around St Helena in 2018 (JR17-004) and 2019 (DY100). (A) St Helena island, Bonaparte and (B) Cardno and Southern Cross seamounts are labeled. Further details are given in the Supplementary Data Table.

Figure 3. Cetacean sightings around Tristan da Cunha in 2018 (JR17-004). Sea state was too rough for any observations to be made in 2019. Tristan da Cunha, Crawford, Yakhont, McNish and R.S.A. seamounts are labeled.

Survey Methods

Tristan da Cunha and St Helena

In Tristan da Cunha and St Helena, opportunistic observations were made by two experienced marine mammal observers, using handheld binoculars, during two multidisciplinary research cruises to assess the shelf biodiversity (shallower than 1000m) in March-April 2018 and 2019. The vessels stopped frequently at multiple sampling stations concentrated around the seamounts. The two research cruises were an opportunity, during transit and when sampling, to survey for presence or absence of marine mammals in the large, mostly pelagic EEZs of Tristan da Cunha and St Helena that are difficult for small vessels to access. Surveys were at a time of a year when very little previous data has been collected. Observers identified species and recorded low, high and best estimates of group sizes, while the vessel continued along its course. The best estimate was reported as the group size. Since these were not dedicated marine mammal surveys, no deviations from the transit track line were made, so, depending on sea state, individuals were visible for approximately 20 min. Sampling effort for Tristan da Cunha and St Helena is detailed in Table 1. When seas were calmer than sea state 6, two observers scanned for wildlife from the bridge wings. When the ship was sampling at stations on Yakhont and Crawford seamounts, single observers alternated 2-h shifts throughout the same daytime periods. In 2019 during DY100, both Tristan da Cunha and St Helena surveys overall experienced rougher seas (higher sea state) and poor visibility conditions than in 2018 impacting observer hours and sighting opportunities.

South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

During DY99 around SGSSI on the RRS Discovery, vessel transit was used as the basis for transects with observation effort using distance sampling, with two observers and separate viewing points on the vessel (Buckland et al., 2001). Observers were located on the bridge deck on the port and starboard side, and during observation effort periods, observations were made from −10 degrees to 90 degrees on the starboard side and from −90 degrees to 10 degrees on the port side, thus ensuring a 20-degree overlap in observation sector at the bow of the ship. Observations were made when in transit in daylight hours and sea state calmer than 6.

Results

The complete list of sightings from all three surveys is presented in the Supplementary Table. Key sightings are discussed by territory and summarized in Table 2.

St Helena

In both years, most sightings were of known resident dolphin species, associated with the islands and seamounts (Clingham et al., 2013). Three species, pantropical spotted (Stenella attenuata), bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus), and rough-toothed dolphins (Steno bredanensis) were sighted, with the largest group consisting of 150 bottlenose dolphins. In 2018 five species were recorded during 11 sightings. Within these were four sightings of 17 sperm whales (Physeter catodon), but no sperm whales were recorded in 2019. Conversely, three humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) were seen in 2019 but none in 2018. Humpback whales were one of five species recorded, one of which was unidentified, during six sightings in 2019.

Tristan da Cunha

In 2018 six out of seven sightings were of toothed whales (Odontocetes), including pods of long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) and long-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus capensis) as well as a killer whale (Orcinus orca) and an unidentified beaked whale. In 2019 sea state was consistently greater than 6 and so no sightings were recorded.

South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands

Observers completed 67 h of marine mammal observation in total, covering a total of just over 800 nautical miles. The black lines in Figure 4 show the observation effort transects within 200 nm of SGSSI. A total of 326 cetaceans were counted during these observations. The most frequently observed cetaceans, seen throughout the entire survey, were humpback whales, followed by hourglass dolphins (Lagenorhynchus cruciger), groups of pilot whales (Globicephala spp.), and fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus). Other less frequently sighted species included blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus), minke whales (Balaenoptera bonaerensis), sperm whales, and beaked whales (Ziphiidae). Additional species were recorded with some certainty but are reported here as “unidentified” in the Supplementary Data Table. Of note was the difference in species seen in different regions. Around South Georgia and to the north of Montagu Island (58.3°S, 26.2°W), cetacean sightings were primarily of humpback and other baleen whales. Baleen whales remained the most frequent encounters from Montagu Island southwards; however here, pilot whales were also encountered on several transects, as well as hourglass dolphins and beaked whales.

Figure 4. Observations of identified marine mammals within 200 nm around South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands in 2019 (DY99). The main island of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands are labeled. Further sightings with less certain IDs are reported in the Supplementary Data Table.

Discussion

The data collected during these surveys will add to the knowledge of current cetacean group size around these remote British Overseas Territories (Supplementary Data Table). All three territories are known areas for humpback and sperm whales (MacLeod and Bennett, 2007; Rossi-Santos et al., 2007; Best et al., 2009), which were subjected to commercial whaling for periods during the 19th and 20th centuries until the whaling moratorium in 1986. Since the moratorium, the recovery of some populations from near extinction has been a significant conservation success (Cooke, 2018; Zerbini et al., 2019). With this recovery it is possible that cetaceans could be returning to some of the lesser-known areas within their historical ranges. However, there are emerging threats, particularly from climate change impacts on food availability, e.g., krill, Euphausia superba, in the Southern Ocean (Atkinson et al., 2019; Morley et al., 2020). Pollution, such as plastics, are increasing globally (see Barnes et al., 2018 for the Atlantic) and negative impacts of macroplastics on cetaceans are regularly reported (Roman et al., 2020). To monitor the impacts of these emerging threats, any information that will improve the knowledge of locations used by cetaceans as their populations recover and start to spread back into previous grounds, will aid zonal planning and ecosystem based management of fisheries (e.g., Requena et al., 2020).

St Helena

The majority of previous sightings at St Helena were of species of dolphins, pantropical spotted, bottlenose, and rough-toothed (MacLeod and Bennett, 2007; Clingham et al., 2013). These are species that are known to be associated with the island shelf and the seamounts, and although the bottlenose dolphins are least likely to be sighted between February and May (Clingham et al., 2013), both our surveys recorded them in April. Our survey shows that the decrease in the number of observations during this period (Clingham et al., 2013) may be a result of dolphins spending more time further offshore where they will be observed less frequently by inshore surveys, rather than them migrating away from St Helena waters.

St Helena is a known wintering ground for several cetacean species but there is very limited knowledge of which populations use these waters (Whitehead, 2003; MacLeod and Bennett, 2007; Clingham et al., 2013). Our surveys around St Helena were outside of previously described peak seasons for humpback whale abundance, which occurs during the austral winter, July to October (MacLeod and Bennett, 2007). Our sightings of humpback whales during April suggests that more research is required throughout the year to fully understand the distribution and group size of this species in St Helena waters. Further records of predominantly anecdotal sightings collated by St Helena Government are also helping to build knowledge of humpback whales outside of peak season.

While there are limited historical records of hunting of sperm whales around St Helena (Clark, 1887; Perrin, 1985), the migratory behavior of this species within the tropics is uncertain (Whitehead, 2003), so it is not clear if sperm whales use St Helena waters throughout the year. No sperm whales were recorded by MacLeod and Bennett (2007) in the austral winter of 2003, a survey that largely focused on areas close to shore. Between 2003 and 2012 dedicated marine mammal monitoring only recorded anecdotal sightings of sperm whales, one from a fisherman, one from a visiting yacht (Clingham et al., 2013) and a pod of 20 from an unknown source in 2009. The sightings of sperm whales in 2015 and 2018 once again highlight the value of these surveys and that more observations are required.

Tristan da Cunha

The sightings in Tristan da Cunha’s waters were also mostly of species that are sighted throughout the year, with more than half the sightings from around the seamounts. Sightings were mainly of Odontocetes (toothed whales), mostly pods of pilot whales, which has previously been recorded from sporadic sightings and strandings (Scott, 2017). One beaked whale was sighted in the 2018 survey, but the sea state was too high for it to be identified to species. Tristan da Cunha is also a known location for beaked whale strandings, and the first live sighting of Shepherd’s beaked whale since 2012 was recorded in 2017 (Best et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2019), confirming the persistence of a population in Tristan da Cunha waters.

South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands

Whales were exploited from the beginning of the 20th century, with whaling focusing on the waters around the island of South Georgia and on three main species: blue whales, fin whales, and southern right whales (Clark, 1919). By 1965 around 175,250 whales had been processed on South Georgia, and the local whale populations were close to being depleted (Moore et al., 1999), leading to an effective end of industrial whaling in this region. From 1979 to 1998, the main species sighted around the island of South Georgia were fin whales, sei whales, humpback whales, southern right whales, minke whales, southern bottlenosed whales, sperm whales, killer whales, and pilot whales (Moore et al., 1999). The peak abundances were recorded during February and March (Moore et al., 1999), with southern right whales being the most commonly recorded. A survey around the island of South Georgia in 1997, largely in depths shallower than 2000 m, recorded a total of 57 cetaceans over 27 sea days, and was again dominated by southern right whales (Moore et al., 1999). During a survey of the South Georgia shelf in 2018 southern right whales were also the most commonly encountered species (Jackson et al., 2020).

Twenty-two years after the Jan-Feb 1997 survey, the DY99 survey recorded more than five times as many cetaceans (326) over 13 sea days within 200nm of the coast. These differences could be because DY99 only completed two tracks at depths shallower than 2000m to the north of South Georgia, the remaining observations were further off-shore from the Island of South Georgia than the majority of the previous surveys. The species composition recorded during the DY99 survey was similar to the 1997 survey, except that the most frequently recorded species in 2019 was the humpback whale and no southern right whales were seen. This may be due to the different focus of these surveys between coastal versus offshore waters (e.g., Hedley et al., 2001). The frequencies of species sightings have changed over time around South Georgia (Richardson et al., 2012; Calderan et al., 2020) with humpback whales becoming increasingly common in recent years (Jackson et al., 2020). Previously a very rare sighting, blue whales have been seen more frequently since 2018 (Richardson et al., 2012; Calderan et al., 2020). Both 2019 surveys, the DY98 survey in January/February (Baines et al., 2019) and the DY99 survey in February/March, recorded humpback whales as the most frequent sighting, not only across South Georgia, but also across the South Sandwich Islands as well.

The 1997 survey did not record major aggregations of cetaceans, which sharply contrasts with February records from the whaling era (Moore et al., 1999). The largest single species group sighting recorded during the DY99 survey consisted of nine large dolphins. Groups greater than 25 were observed during DY99 but these consisted of aggregations of multiple species. There is some evidence that larger groups of humpback whales are being seen again, as recorded by the Groundfish Survey in 2015 around Shag Rocks (unpublished data). The Scotia Arc humpback whales largely breed off the coast of Brazil, where humpback whale group size has increased over the past decades (Bortolotto et al., 2017; Zerbini et al., 2019). The increased sightings around South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands could be a consequence of a continued recovery of these humpback whale populations (Jackson et al., 2020).

Dedicated surveys of cetaceans in the waters surrounding these three British Overseas Territories have been relatively limited, although they have increased in recent years, particularly around South Georgia (see Calderan et al., 2020). Thus these opportunistic data, during marine ecosystem research cruises, provide valuable information on the distribution of cetaceans in these territories and can help inform about the trajectories of whale populations, in particular, where future studies should focus. Further dedicated ship-based cetacean surveys, will allow further opportunities for species to be identified. Combining these with acoustic sound trap studies that are being conducted in South Georgia, and are planned for Tristan da Cunha, will lead to a greater understanding of cetacean group size and distribution, contributing to management of the biodiversity of these remote oceanic territories.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

This was an observational rather than an experimental study and did not therefore require ethics approval.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

JR17-004 and DY100 were jointly funded by the United Kingdom Government Blue Belt Programme, through the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Sciences and the Marine Management Organisation, and the Natural Environment Research Council (Grant NE/R000107/1) through the British Antarctic Survey. AS was funded by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. DY99 was funded by the United Kingdom Government Blue Belt Programme through the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Sciences and the Marine Management Organisation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a shared program with the authors at the time of review.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of the local communities, governments and the crews of the RRS James Clark Ross, RRS Discovery, Ramon Benedet, and Georgia Robson. James Bell produced the sightings figures.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.660152/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Data Table | Date, locations, and abundance estimates for cetacean sightings during the JR17-004, DY099, and DY100 surveys to St Helena, Tristan da Cunha, and South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands.

References

Atkinson, A., Hill, S. L., Pakhomov, E. A., Siegal, V., Reiss, C. S., Loeb, V. J., et al. (2019). Krill (Euphausia superba) distribution contracts southward during rapid regional warming. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 142–147. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0370-z

Baines, M., Reichelt, M., Lacey, C., Pinder, S., Fielding, S., Kelly, N., et al. (2019). Density and Abundance Estimates of Baleen Whales Recorded During the 2019 DY098 Cruise in the Scotia Sea Around South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Report to CCAMLR WG-EMM, WG-EMM-19/27. Hobart, Tas: Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

Barnes, D. K. A., Morley, S. A., Bell, J., Brewin, P., Brigden, K., Collins, M., et al. (2018). Marine plastics threatens giant Atlantic marine protected areas. Curr. Biol. 28, R1121–R1142. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.064

Best, P. B., Glass, J., Ryan, P. G., and Dalebout, M. L. (2009). Cetacean records from Tristan da Cunha, South Atlantic. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 89, 1023–1032. doi: 10.1017/s0025315409000861

Bortolotto, G. A., Danilewicz, D., Hammond, P. S., Thomas, L., and Zerbini, A. N. (2017). Whale distribution in a breeding area: spatial models of habitat use and abundance of western South Atlantic humpback whales. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 585, 213–227. doi: 10.3354/meps12393

Buckland, S. T., Anderson, D. R., Burnham, K. P., Laake, J. L., Borchers, D. L., and Thomas, L. (2001). Introduction to Distance Sampling. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Calderan, S. V., Black, A., Branch, T. A., Collins, M. A., Kelly, N., Leaper, R., et al. (2020). South Georgia blue whales five decades after the end of whaling. Endanger. Species Res. 43, 359–373. doi: 10.3354/esr01077

Clark, A. H. (1887). The American whale-fishery 1877-1886. Science 9, 321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.ns-9.217s.321

Clark, R. S. (1919). “South Atlantic whales and whaling,” in South: The Story of Shackleton’s Last Expedition, 1914-1917, ed. E. H. Shackleton (London: William Heinemann).

Clingham, E., Henry, L., and Beard, A. (2013). Monitoring Population Size of St Helena Cetaceans. 2003-2012. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.734.6030&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed December 10, 2020).

Cooke, J. G. (2018). Megaptera novaeangliae. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T13006A50362794. Available online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T13006A50362794.en (accessed December 10, 2020).

Geissler, W. H., Wintersteller, P., Maia, M., Strack, A., Kammann, J., Eagles, G., et al. (2020). Seafloor evidence for pre-shield volcanism above the Tristan da Cunha mantle plume. Nat. Commun. 11:4543. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18361-4

Hedley, S., Reilly, S., Borberg, J., Holland, R., Hewitt, R., Watkins, J., et al. (2001). Modelling Whale Distribution: A Preliminary Analysis of Data Collected on the CCAMLR-IWC Krill Synoptic Survey, 2000. CCAMLR-IWC, SC/53/E9). Hobart, CCAMLR.

Hogg, O. T., Huvenne, V. A. I., Giffiths, H. J., Dorschel, B., and Linse, K. (2016). Landscape mapping at sub-Antarctic South Georgia provides a protocol for underpinning large-scale marine protected areas. Sci. Rep. 6:33163. doi: 10.1038/srep33163

Jackson, J. A., Kennedy, A., Moore, M., Andriolo, A., Bamford, C. C. G., Calderan, S., et al. (2020). Have whales returned to a historical hotspot of industrial whaling? The pattern of southern right whale Eubalaena australis recovery at South Georgia. Endanger. Species Res. 43, 323–339. doi: 10.3354/esr01072

MacLeod, C. D., and Bennett, E. B. (2007). Pan-tropical spotted dolphins (Stenella attenuata) and other cetaceans around St Helena in the tropical south-eastern Atlantic. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 87, 339–344. doi: 10.1017/S0025315407052502

Makler, M., and de Matos Mello, S. L. (2007). Analysis of seafloor depth anomalies between the Ascension and St Helena Islands, South Atlantic. Rev. Bras. Geof. 25, 107–114. doi: 10.1590/s0102-261x2007000500011

Moore, M. J., Berrow, S., Jensen, B. A., Carr, P., Sears, R., Rowntree, V. A., et al. (1999). Relative abundance of large whales around South Georgia (1979-1998). Mar. Mamm. Sci. 15, 1287–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00891.x

Morley, S. A., Abele, D., Barnes, D. K. A., Cárdenas, C. A., Cotté, C., Gutt, J., et al. (2020). Global drivers on Southern Ocean Ecosystems: changing physical environments and anthropogenic pressures in an earth system. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:547188. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.547188

Morley, S. A., Collins, M. A., Barnes, D. K. A., Sands, C., Bell, J. B., Walmsley, S., et al. (2018). Helping Tristan da Cunha and St Helena Manage Their Marine Environments. Report of James Clark Ross Cruise 17-004. BODC Cruise Reports. 139. Liverpool, BODC.

Requena, S., Oppel, S., Bond, A. L., Hall, J., Cleeland, J., Crawford, R. J. M., et al. (2020). Marine hotspots of activity inform protection of a threatened community of pelagic species in a large oceanic jurisdiction. Anim. Conserv. 23, 585–596. doi: 10.1111/acv.12572

Richardson, J., Wood, A., Neil, A., Nowacek, D., and Moore, M. (2012). Changes in distribution, relative abundance, and species composition of large whales around South Georgia from opportunistic sightings: 1992 to 2011. Endanger. Species Res. 19, 149–156. doi: 10.3354/esr00471

Roman, L., Schuyler, Q., Wilcox, C., and Hardesty, B. D. (2020). Plastic pollution is killing marine megafauna, but how do we prioritize policies to reduce mortality? Conserv. Lett. 14:e12781. doi: 10.1111/conl.12781

Rossi-Santos, M. R., Baracho, C., Cipolotti, S., and Marcovaldi, E. (2007). Cetacean sightings near South Georgia islands, South Atlantic Ocean. Polar Biol. 31:63. doi: 10.1007/s00300-007-0333-8

Scott, S. (2017). A Biophysical Profile of the Tristan Da Cunha Archipelago. Available online at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2019/07/cp_on_a_remote_archipelago_rich_biodiversity_faces_threats.pdf (accessed December 13, 2020).

Thompson, C. D. H., Bouchet, P. J., and Meeuwig, J. J. (2019). First underwater sighting of Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi). Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 12:6. doi: 10.1186/s41200-019-0165-6

Trathan, P. N., Collins, M. A., Grant, S. M., Belchier, M., Barnes, D. K., Brown, J., et al. (2014). The South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands MPA: protecting a biodiverse oceanic island chain situated in the flow of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Adv. Mar. Biol. 69, 15–78. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800214-8.00002-5

Whitehead, H. (2003). Sperm Whales: Social Evolution in the Ocean. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Whomersley, P., Morley, S., Bell, J., Collins, M., Pettafor, A., Campanella, F., et al. (2019). Blue Belt Programme: RRS Discovery DY100 Survey Report. (Lowestoft, United Kingdom: Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science).

Keywords: St Helena, Tristan da Cunha, South Georgia and South Sandwich Island, Marine protected area, whales and dolphins

Citation: Martin SM, Soeffker M, Schofield A, Hobbs R, Glass T and Morley SA (2021) Cetaceans Sightings During Research Cruises in Three Remote Atlantic British Overseas Territories. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:660152. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.660152

Received: 28 January 2021; Accepted: 25 June 2021;

Published: 28 July 2021.

Edited by:

Joanna Stockill, Marine Management Organisation (MMO), United KingdomReviewed by:

Danielle Kreb, Conservation Foundation for Rare Aquatic Species of Indonesia, IndonesiaWolfram Geissler, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), Germany

Copyright © 2021 Martin, Soeffker, Schofield, Hobbs, Glass and Morley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stephanie M. Martin, RW52aXJvbm1lbnQucG9saWN5QHRkYy51ay5jb20=

Stephanie M. Martin

Stephanie M. Martin Marta Soeffker

Marta Soeffker Andy Schofield

Andy Schofield Rhys Hobbs

Rhys Hobbs Trevor Glass1

Trevor Glass1 Simon A. Morley

Simon A. Morley