- 1Global Ocean Accounts Partnership, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2African Marine Environment Sustainability Initiative, Lagos, Nigeria

- 3World Ocean Council, Honolulu, HI, United States

Regional and global ocean governance share complex, co-evolutionary histories in which both regimes – among others – interacted with and used the ocean and resources therein to consolidate, expand, and express power. Simultaneously, regional and global ocean governance relations have changed continuously, particularly when we are trying to understand their differences within the logic of regionalisation, regionalism, and globalisation. The paper is generally based on deductive reasoning and reflects scholarship in security studies, political science, international law, international relation, development studies, and African studies. It delves into the critical aspect of understanding the nexus/relationship between regional and global ocean governance in critical traditional and contemporary ocean policy domains, specifically from an African regional ocean governance standpoint. Ocean governance processes that are historically confronted by globalisation, multilateralism, and post-colonisation are confronted by the rise of regionalism, especially the need for nation-states and regions to respond to and manage traditional and emerging ocean challenges. Responses to these challenges by various actors, including states, economic blocks, private sector, financial institutions, and non-governmental organisations, development partners, etc., result in different forms of relationships that refocus regions’ activities toward globally defined ocean agendas. A review of different policy domains (including maritime security, environmental, economic, and socio-political governance) critical for regional ocean governance sets a robust background for understanding the contextual factors and concerns inherent in the regional-global ocean governance nexus. These outcomes, therefore, help us to arrive at a five-fold taxonomy of different types/degrees of linkages developed around the regional-global ocean governance relationship spectrum described as (1) discrete, (2) conflictual, (3) cooperative, (4) symmetric, and (5) ambiguous. Comparatively, experience and perspective from Africa are utilised to support raised arguments about these linkages. Furthermore, this spectrum allows for the diagnosis of the utilities and most prevalent arguments that regional governance’s effectiveness is directly related to the nature of the interaction between regional governance schemes and global governance; and vice-versa. This paper’s outcomes reveal how government, institutions, actors, and researchers address the relationship between regional and global ocean governance and generate a valuable way to think about current and future global and regional ocean governance direction while outlining some logical possibilities for an effective form of ocean governance.

Introduction

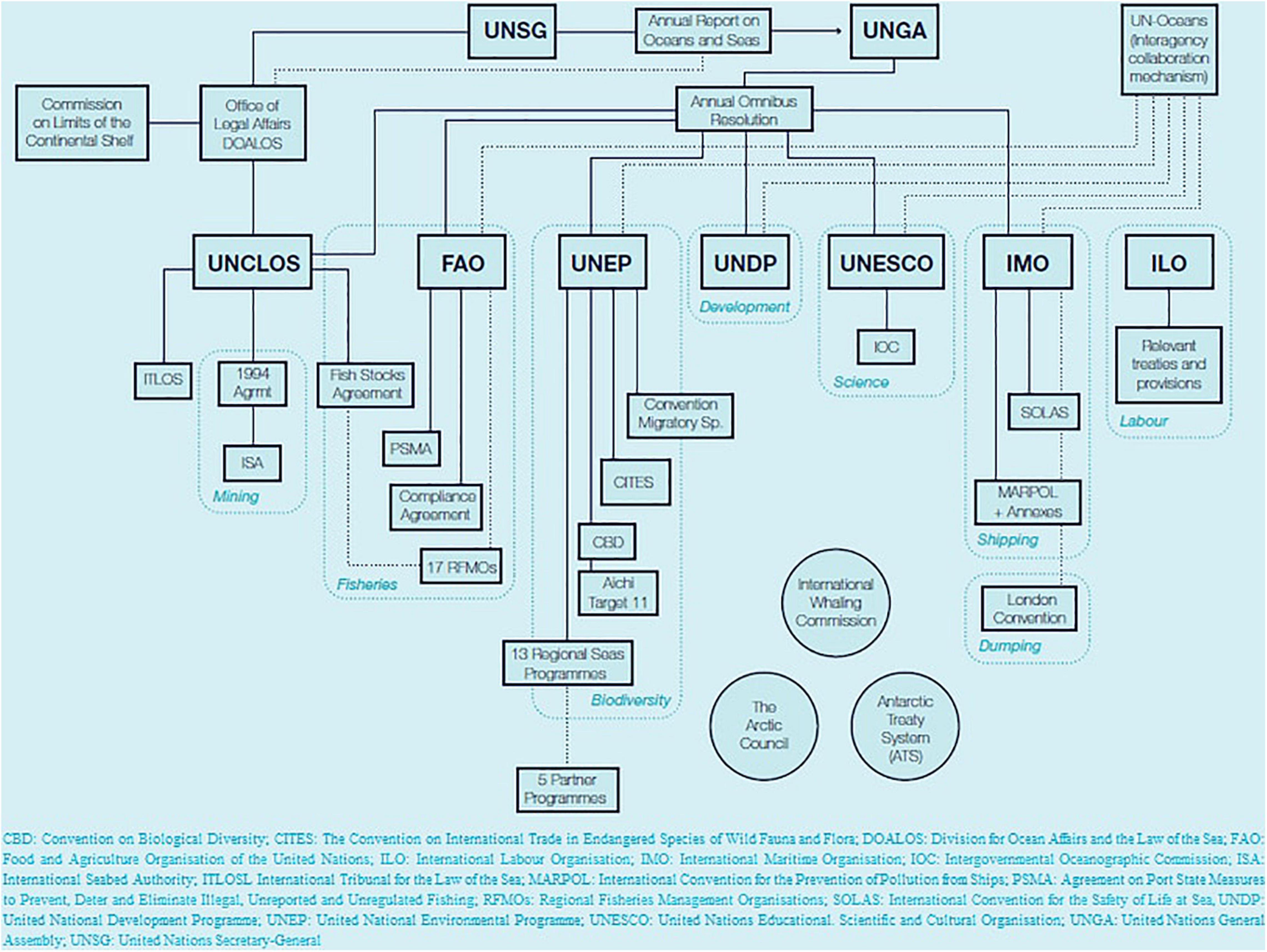

Enhanced and holistic knowledge of the ocean’s system, including its physical and biochemical processes and socio-ecological characteristics, are imperative for achieving global ocean agendas and sustainable development (Österblom and Folke, 2013; citealpBR187; Adewumi, 2020a). However, there is a dearth of the needed information and knowledge to fully understand and govern the ocean (Halpern et al., 2019), coupled with an array of pressing issues confronting today’s coastal and marine domains. Such issues include unsustainable exploitation of resources, climate change effects, specific regulation of activities in special issue waters (e.g., the Arctic and Antarctic). Issues such as states’ competence other than flag-states in enforcement and compliance and biodiversity conservation in Areas Beyond National Jurisdictions (ABNJ) are also not left out. The proliferation of these issues indicates that ocean management is a complex web of interrelated, intertwined, converging, competing demands and interests (Futures Centre, 2015; Campbell et al., 2016; Grip, 2016). Evidence of these complexities is reflected in the fragmentation of today’s ocean governance framework, arising from changing relations between the regional and global regime of governance and regional and global power in managing the ocean (Mahon, 2015; Wilson et al., 2019; IOC-UNESCO, 2020; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summarised schematic diagram of global ocean governance showing sectoral approach and plethora of organisations (source: Global Ocean Commission, 2014).

However, the architecture of global ocean governance is defined as the roles of regional and global institutions and other actors such as states, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), the private sector, financial institution, etc., participating in the governing of the ocean ecosystem toward sustainable development (Allison, 2001; Mahon and Fanning, 2019a; Petersson et al., 2019; Liss, 2020; Haas et al., 2021). Nevertheless, global governance and globalisation often drive ocean governance regulations, particularly in areas where ocean protection, economic, and security imperatives overlap in expected and unexpected ways. The global ocean space is currently regulated by upward of 576 bilateral and multilateral agreements, spread across several international, regional, and national organisations mandated to carry out monitoring and implementation, but which often lack the wherewithal to ensure compliance and enforcement (IOC-UNESCO, 2020). Since 2003, in response to the fragmentation in global ocean governance, an Oceans and Coastal Areas Network, “UN-Oceans” was approved by the United Nations High-Level Committee on Programmes to ensure stronger cooperation between entities and specialised agencies of the UN system with an ocean mandate (UN-Oceans, n.d.). However, due to lacklustre coherence with other mechanisms such as the UN-Water and UN-Energy, UN-Oceans is considered insufficient to ensure coordination and promotion of synergy amongst the several agreements relevant to regulating the global ocean (Zahran and Inomata, 2012). This further entrenches the perceptions that global ocean governance mechanisms are too weak and cumbersome to deliver the urgent large-scale collective action needed to tackle oceanic problems.

More pragmatic approaches to national, regional, and global ocean governance are needed to ensure the effectiveness of ocean governance (Pyc, 2016; Rudolph et al., 2020), further substantiation of UNCLOS, and a holistic paradigm of sustainable development (Visbeck et al., 2014). Following the principle of subsidiarity, these global ocean frameworks’ deficiencies indicate that several oceanic challenges can be better handled at regional levels to reduce the number of challenges handed at the international and supranational levels. After all, scholars such as Österblom and Folke (2013); Bodansky et al. (2014), Kacowicz (2018) note that the global view of regions is directly related to the possible interlink between regional and global governance. Also, by their nature, regional arrangements do not neatly fit into existing global arrangements, nor do they operate in isolation from a larger context of global governance (Väyrynen, 2003; Ba and Hoffmann(eds), 2005; Yilmaz and Li, 2020).

It is not just the fragmentation in the global governance regime that reveals the inherent footprints that globalisation maintains toward streamlining relationships between regional and global ocean governance. The normative understanding of governance and the connection between maintaining ecosystems sustainability and democratic values also play a role. According to Pickering et al. (2020), ecological and environmental democracy concepts already reveal the relationship between ensuring environmental sustainability while safeguarding democracy. Within a non-electoral and trans-national context, democratic practices and ideas are, in fact, critical to influencing the participation gap and politics of natural resources governance at all levels (Bäckstrand, 2006; Pickering et al., 2020).

Therefore, this paper examines the possible interplay between ROG and GOG from an African perspective, highlighting various identifiable elements that influence and remake regions and global institutions’ roles in ocean governance. There have been minimal systematic studies of regional ocean governance in less developed countries where the benefits of globalisation are less obvious or are absent despite years of donor-oriented ocean management and governance programmes. Even less known is the effect of globalisation on Africa’s regional ocean governances. Also, this paper focuses on Africa, where ocean governance and policy remain woefully understudied compared with other inquiry areas, such as financial outlook, gender equality, entrepreneurship, democratisation, conflict, aid effectiveness, and ethnicity. Even where there have been studies on ocean governance and policy (Agbakoba, 2006; Diop et al., 2011; Dzidzornu, 2011; Hewawasam et al., 2015; UNECA, 2016a; Vrancken, 2018; Belhabib et al., 2019; Adewumi, 2020a), there are few new inquiries into how African ocean is governed from a comparative institutional and political perspective. In this respect, this paper’s author poses two mutually exclusive questions: are there linkages between the logic and operations of ROG and the general frameworks/instruments of GOG? What are the identifiable factors under which these linkages can be explained?

This paper focuses on three considerations to answer these questions. First, it supports and elaborates that various regional ocean governance mechanisms emerge from global forces, policies, and actions that fully or partially reshape the regions’ activities toward the globally defined ocean or related agendas and rules such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Pyc, 2016; UNEP, 2017; Mahon and Fanning, 2019a). Second, it centres on how these dynamics and relations are influenced by international regimes and intra-regional conditions that define, enable, and constrain regions’ responsibilities and actions while emphasising markets and sovereignty rights (Briceño-Ruiz, 2014; UNEP, 2017). By implication, this involves accounting for the perspective of regulatory institutions, actions, and interaction of actors, their norms and rules concerning the ocean (Pellowe and Leslie, 2020). Finally, the paper accentuates the imbalances and role of power dynamics, mainly as it concerns the influences of capitalism on ocean governance and how it continually shapes the structure of regions vis-a-vis regional ocean governance.

Likewise, the paper conceptualises ocean governance architectures as a reflection from the lens of different “policy domains” rather than “issue areas.” To Burstein (1991), policy domain is a sub-set of a political system organised around concrete issues that define a domain and “sharing inherent substantive characteristics that influence how they are framed and dealt with.” In contrast, Keohane’s (1984) concept of “issue areas” has the disadvantage of excluding actors that play essential roles while the policy domain is more inclusive – following that, ocean governance architecture emphasises different actors’ participation (Poe and Levin, 2017).

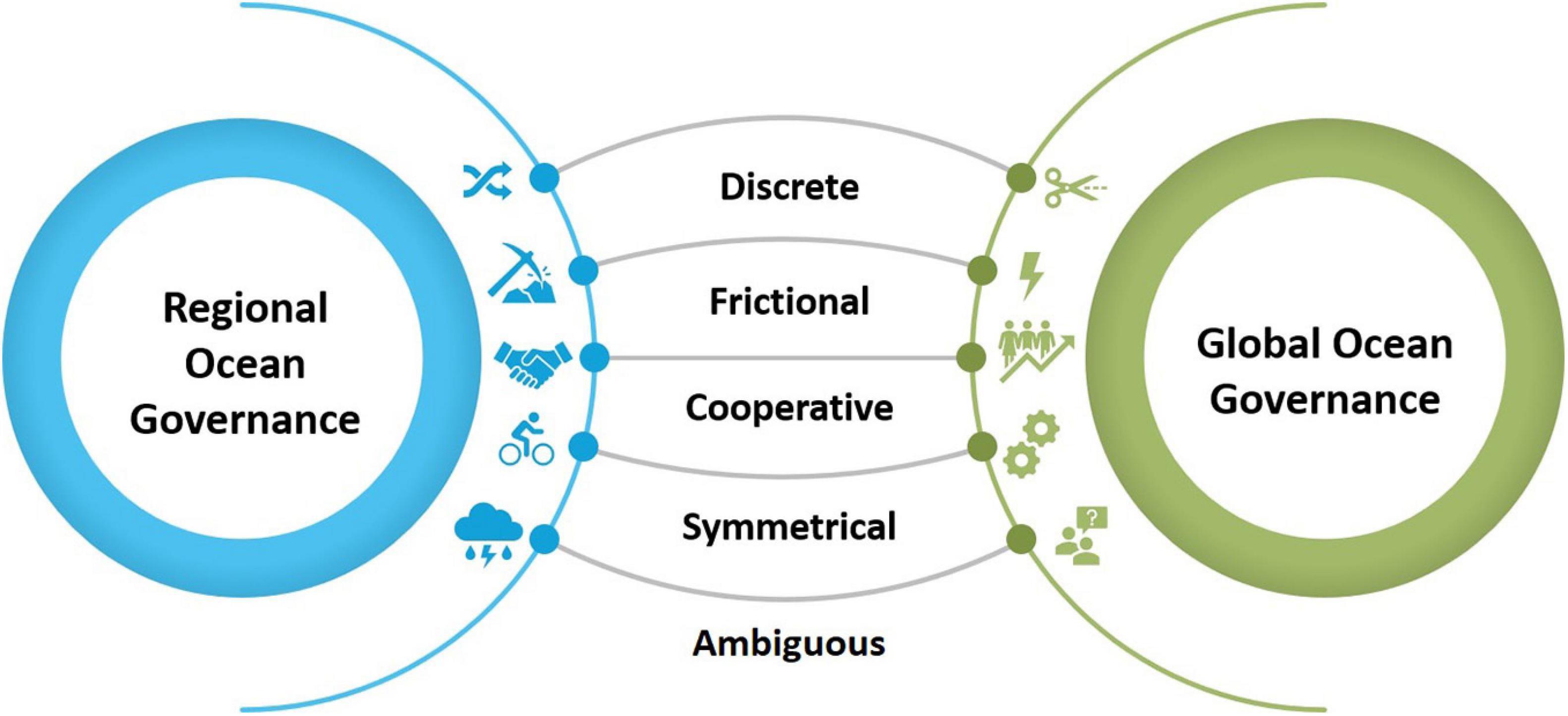

Based on the classification of the degree of fragmentation of global governance architecture by Biermann et al. (2009) and Nolte (2016), the paper proceeds to identify fivefold taxonomy of linkages that signify the relationship between ROG and GOG: (1) discrete; (2) conflict; (3) cooperation; (4) symmetricity; and (5) ambiguous. These classifications provide the basis for highlighting various utilities from the links or/and relationship between global and regional ocean mechanisms.

Global and Regional Ocean Governance Approach and Issues

Ocean governance is the process that ensures ecosystem structures and functions are sustained, including the coordination of various marine environmental protection and ocean uses (Pyc, 2016). Even though multilateralism appears to be increasingly important in today’s globalised world, there have been consistent warnings that it is currently facing a legitimacy crisis, and hence, must be reshaped and readjusted (Zurn, 2003; Zürn, 2011) to meet 21st century environmental, social, and economic challenges. Attention has been called to the current deteriorating state of marine ecosystems (Blau and Green, 2015; Hattam et al., 2015; Pauli and Corbis, 2015). Improved governance has been touted to play a crucial role in halting the continuing and pressing marine challenges and developing a sustainable future for coastal and oceanic economies (Tarmizi, 2010; Al-Abdulrazzak et al., 2017). Töpfer et al. (2014) corroborate this argument, acknowledging that ocean governance is now at a critical point where existing institutions need to be redesigned to address current pressing problems. They stress that ocean governance is not an exception when it comes to institutional misfit, just as Österblom and Folke (2013) have earlier explained that today’s ocean governance perhaps does not differ from happenings in other fields of global relevance.

Two distinct types of transnational ocean organisation are distinguishable. Firstly, organisations such as the United Nations Division of Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (UNDALOS), International Maritime Organisation (IMO), Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), ocean-related units within the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), World Trade Organisation (WTO), etc., provide the organisational and infrastructural support for the transnational ocean regulations. Secondly, other transnational organisations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Ocean Conservancy, Conservation International, etc., focus on advocacy and influencing governmental coastal and marine policies by addressing transnational public opinion.

Nonetheless, global mechanisms for ocean governance have faced criticism. In the belief that existing international mechanisms need reform in the face of implementation deficiencies and lacunae arising from emerging unforeseen challenges during UNCLOS negotiations, Visbeck et al. (2014) envisioned a reinvigorated commitment to marine issues in the SDGs. Indeed, the derived commitments and focus of SDG 14 have since 2015 triggered the imperative for authentic partnerships and increased international cooperation to have a coherent governance framework that can address the various coastal and oceanic challenges both at a national, regional or global scale. It is recognised that many ocean areas are insufficiently protected – particularly the high seas – raising the question that borders on either a lack of legal rules or shortcomings in how existing rules are implemented and further developed (Houghton, 2014).

Ehlers (2016) reported that ocean governance had been a magical word in recent times, indicating that a mere Google search for ocean governance returns a whopping 5.5 million results and posits four questions that would need to be answered, including: “Who is responsible for ocean governance? Are the individual states exercising their sovereign rights within their jurisdiction, and do these rights include freedom at sea? Is it enough that states at best cooperate constructively in intergovernmental organisations such as IMO? Moreover, is it enough to conclude international agreements leaving the implementation and enforcement to the states? Alternatively, do we have to find some new approaches by giving more competencies to international organisations?” These are the sort of questions that call for far-reaching and immediate answers. To Zürn (2011), the more international institutions dealing with ocean governance at the global level, the higher the number of collisions between different international regulations and national ones, a difference which only a supranational arbitration body can settle. Zürn is of the school of thought that the functioning of international institutions such as the United Nations does not meet democratic standards because of the absence of recognised decision-makers that could be held accountable for wrong decisions. Therefore, it is impossible to scrutinise the international decision-making process as prime actors in international politics are only accountable to a fraction of the people affected by their activities. The international community is conscious that improving global and regional cooperation should be in the mainstream of socio−economic and political discourse (Pyc, 2016).

Nonetheless, Pyæ (2011) and Houghton (2014) favour the development of standard rules to govern the coastal and marine domains. For ocean governance to be effective, Pyæ (2011) posits that there must be a global consensus on rules and procedures and regional actions based on shared principles and national legal frameworks and integrated policies. Developing these rules will require stepping back and looking at the legal rules system applicable to the oceans (Houghton, 2014).

Now that UNCLOS cannot meet today’s ocean challenges and demands, rational use of our ocean calls for integrated maritime governance, understood as the processes of planning, decision-making, and management at the global level (Pyc, 2016). Under its articles 117 and 118, UNCLOS requires states to cooperate with others to conserve the high seas’ living resources (UNEP, 2016). Over the years, the importance of regionalising ocean governance for more straightforward implementation of approaches have gained traction (Tutangata and Power, 2002; Gjerde et al., 2013; Rochette et al., 2015; Vince et al., 2017). This follows the reality that governance itself, in a universal sense, is the fragmentation of political authority stratified in seven dimensions of geography, function, resources, interests, norms, decision making, and policy implementation (Krahmann, 2003). According to several scholars (e.g., Väyrynen, 2003; Henocque, 2010; Behr and Jokela, 2011; Börzel and Risse(eds), 2013; Nolte, 2016; Kahler, 2017; Grevi, 2018), the internationalisation of these governance dimensions has witnessed a sharp shift since the Cold War, giving way to regional characterisation in various forms, shapes, and span – transcending one issue areas, policy domain, institutions, norms, power, and discusses (Pattberg et al., 2014; Isailovic et al., 2013). Regional governance has emerged as a concept sufficiently broad and flexible to grasp the variable interaction patterns between global and transnational institutions (Nolte, 2016). The same goes for the ocean, where regional governance has become an indispensable part of the international ocean system, contributing significantly to the improvement and sustainable development of a globalised ocean (Borgese, 1999; Houghton, 2014; Werle et al., 2019b), as well as presenting new risks (Abbott et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2016). They do so mainly through various mechanisms such as the Regional Seas Programme, Regional Fisheries Bodies, Large Marine Ecosystems (LME) Programmes (UNEP, 2016), and pursued rigorously by regions (European Union, 2017; Keen et al., 2018; EC, 2019). However, Mahon and Fanning (2019b) have opined that for a holistic approach in ROG to happen, concerns such as the composition of ROG arrangement worldwide, how they relate to GOG mechanisms, and each other should be addressed. This means that an understanding of the nexus, utilities and challenges of contemporary regional and global ocean governance and ROG is capable of accelerating an improved ocean governance system.

Materials, Methods and Approaches

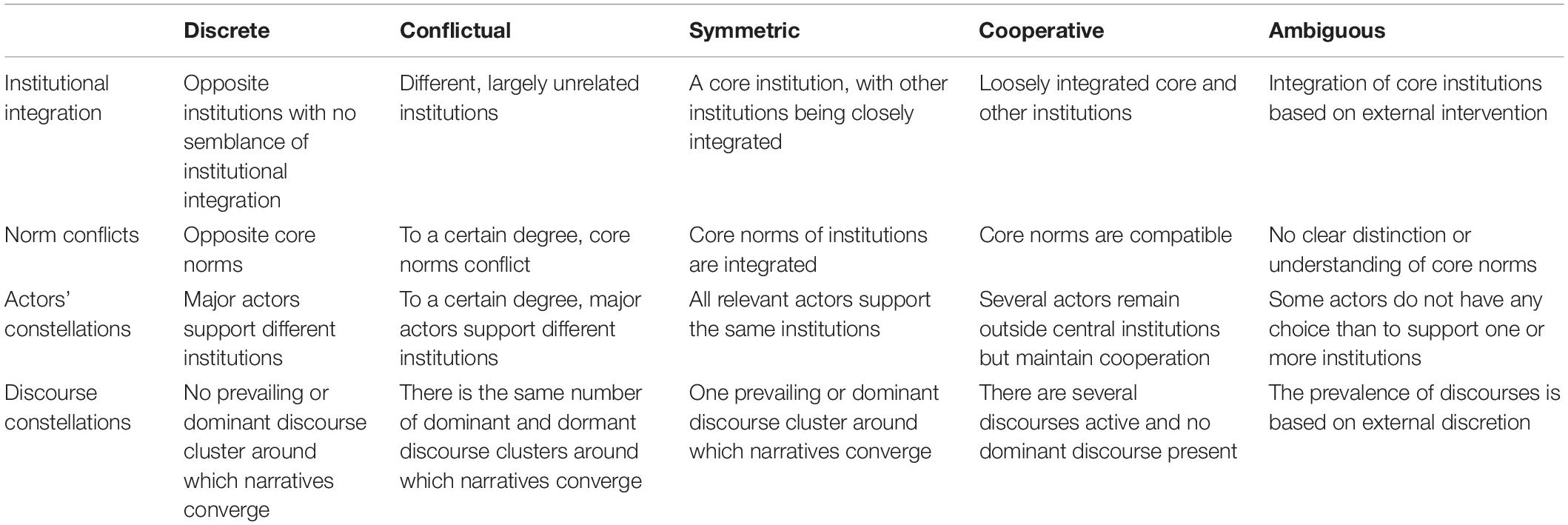

The paper reflects scholarship in fields underrepresented in oceans research to set the foundation, shape the central arguments, frame the findings, and draw conclusion. These include applying findings and observations from the literature review of documents in different fields of studies, including security studies, political science, international law, international relation, development studies, and African studies. In his pioneering work on argumentation theory, Trudy Govier warned about the danger of choosing a deductive over an inductive argument and vice versa, claiming that it leads to false simplicity (Govier, 2018, p. 80). Nevertheless, this paper is generally based on deductive reasoning as various conclusion about the relationship between regional and global ocean governance are contained within the central premise that ocean governance at both regional and global levels exists within the sphere of political and economic ideas, characterised by dynamic power relations. This approach is appropriate for this study, considering that the contemporary social-science scholarship environment is leaning toward variable analysis that seeks to identify causal relationships, whether it is case-based or not (Cock and Fig, 2000; Darmofal, 2012; Nmadu, 2013; Vani et al., 2017; UNEP, 2018). Besides, this study is concerned with generating a new theory as it explores variables helpful in understanding what might be expected within the ROG and GOG relationship given specific situations (see Table 1) or structures (see Table 2). It also generates a new understanding using prior research and approaches to hypothesise that factors such as history, democracy, characteristics of global institutions, states, actors, norms, and principles have implications on the ocean governance architecture pattern.

Table 1. Criteria for analysing linkages between ROG and GOG architecture based on previous studies on the fragmentation of governance architectures by Biermann et al. (2009); Isailovic et al. (2013), Pattberg et al. (2014), and Kempchen (2018).

Table 2. Explanation of the typology of linkage/relationship between the ROG and GOG architectures partly adapted from Biermann et al. (2009) and Nolte (2016) and further modified by the author.

Acknowledging the complexity of ocean governance challenges (Campbell et al., 2016; Rudolph et al., 2020) and the paper’s focus on the relations between entities (states, actors, institutions, norms, values, discusses, etc.), a relational ontology reasoning is adopted, which according to Soboleva (2020), provides relevance epistemic access to reality. Likewise, to examine the ROG and GOG system’s fragmentation, the paper adopts ecological, political, and constructivist perspectives. An ecological, political economy perspective provides the epistemological foundation for illuminating research on why socio-environmental, socio-economical, and socio-political conflicts emerge at certain historical conjunctures in specific geographical and cultural contexts to spark ROG regime (Takeda, 2003; Bassett and Peimer, 2015; Quastel, 2016). Also, it helps us to understand how resistance ideologies against neo-colonialism, economic dominance, and dispossession are organised and sustained to influence new forms of ocean governance structure at a regional level – with emphasis on experience from Africa. Constructivists’ perspectives offer elements to explain the phenomenon of growing political, social, and ecological concerns in the ocean governance policy domain. It posits that reality (be it social, political, or environmental) is a product of human knowledge, beliefs, or meanings (Bevir(ed.), 2010) and has been good in explaining fragmentation as a phenomenon (Isailovic et al., 2013). This perspective has been widely used in socio science studies to explore the critical interplay between political and socio-environmental governance issues, for example, in Maslow and Nakamura (2008); Ide (2016) and Jung (2019).

To address the linkages/relationship between ROG and GOG, the paper identifies the main issues of ocean governance and the different focus of emerging contestation over time in Africa. Following this, an assessment at the regional level is carried out as a heuristic tool by examining the context of ocean governance architecture trends, identify interactions, similarities, and differences between ROG and GOG systems without diluting the overarching conclusion by concentrating too closely on regional detail. It is building on Acharya’S (2017) notion of a “multiplex world” that has accelerated various movements toward greater regionalisation. The choice of Africa is also based on several factors. First, this paper’s author has a lived and research experience in the region – satisfying the constructivism perspective, which acknowledges the importance of pure experience derived from independent reality natural ideas (Bevir(ed.), 2010). Second, a scholarly lacuna warrants a concentration on Africa because stakes in Africa’s ocean governance and policy are incredibly high. Out of 54 African countries, 38 are coastal or island states, while about 90% of imports and exports in Africa are carried out by sea (UNECA, 2016b). The livelihood and sustenance of a significant number of Africans also depend on ocean resources (Jarrett, 2017), particularly as 66 million Africans are expected to live less than 100 m to the coast by 2030 and about 174 million by 2060 (Neumann et al., 2015).

Understanding Globalisation, GOG Agenda, and the Making of ROG in Africa

In an increasingly connected world lacking any central actor, there is a need to develop “ordered rule and collective action” (Higgott, 2002; Garrad, 2018; Grevi, 2018). Global governance provides the needed orderliness and collective actions with processes and institutions that seek to manage pressing global problems (adhering to the basic norms of international summits, decision making, and decision application). However, ensuring multilateral actions in governance constitutes globalisation, a continually evolving historical process that involves a critical shift in the human social organisation at a spatial scale linking and expanding power relations across and continents (Held et al., 1999; McGrew, 2017). From the mid-20th century, the sea has played host to states expanding their dominance to exploit all available resources, giving rise to trade globalisation (Houghton, 2014). The advent of UNCLOS has also created the “global commons” mentioned by Garrad (2018), with its ambiguous and defined global governance parameters. It has also increased demands on coastal and marine sectors of the variety of GOG institutions, most notably in conservation, shipping, and fishing. Besides UNCLOS and the 2015 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, several efforts have been made globally in response to the marine environment’s challenges. They include the High Level-level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, the Global Ocean Commission, Friends of Ocean Action, the Global Ocean Alliance – 30 by 30 initiative, Global Ocean Accounts Partnership, etc. Many of these initiatives have their central focus on strengthening ocean policy frameworks and regimes while accelerating solutions to critical ocean challenges. UNCLOS and these other efforts have recorded some gains over the years, but there are still tremendous and critical challenges (Molenaar, 2019; Werle et al., 2019a).

Although UNCLOS has already presented a planet-wide ocean system governance in attending to the global ocean challenges, this is proving problematic. The clamour for ocean governance at a planetary scale makes two distinct arguments. The first argument concerns UNCLOS’s ambiguity, which has opened it to political debate and pressure on several issues such as its effectiveness (Mossop, 2018) and legitimacy (NISCSS, 2018). UNCLOS has been criticised on the premise that establishing regulations alone is not enough, but what is paramount is ensuring compliance with these regulations for effective implementation and enforcement (Ehlers, 2016). Secondly, nation-states cannot address and manage transboundary ocean challenges (van Tatenhove, 2017; UNDP, 2018) and issues in special area water such as the High Seas (Ringbom and Henriksen, 2017). This is because notable ocean challenges transcend national and regional borders (Goldin, 2013) and concern several players aware of their impacts (Garrad, 2018). Although a unilateral world government is still farfetched, several global governance mechanisms operate in principle through conventions, protocols, and treaties. Still, in reality, these mechanisms evoke and reflect power imbalances among states (Campbell et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2019), the divergence of views and understanding of oceanic problems, and regime shift in the ocean space (Rudolph et al., 2020; Spalding and de Ycaza, 2020). However, scholars have advocated for an integrated ocean governance approach through which centralised international ocean governance systems are operational under a single institution (Rudolph et al., 2020), or ocean polycentrism anchored in the strengths of existing arrangements while the UN play a leadership role (Fanning and Mahon, 2020). Nevertheless, what is the implication of these dynamics for regional ocean governance in Africa?

Theoretically, the concept of regionalism in the African context has provoked much political rhetoric and many academic debates (see Söderbaum and Grant, 2003; Gibb, 2009; Zajontz, 2013). Three predominant questions at the centre of the debate have been on ways to emancipate the African states from the relics of the precolonial and colonial-era; the understanding of intra-state power dynamics related to social, political, and economic conditions post-independence; and achieving regional cooperation and integration especially in solving problems related to economic, political, environmental or security issues (Börzel and Risse(eds), 2013; Ibrahim, 2013; Chirikure, 2017; Englebert, 2021). All the arguments point to one direction: globalisation has inherently not been kind to Africa.

The forces of globalisation have brought about anti developmentalism both in socio-economic, environmental, and political terms, particularly as they have reinforced the economic marginalisation of African states, negatively impacted the development and consolidation of democratic governance, and encouraged vices such as illegal drugs trade, prostitution, human smuggling, dumping of dangerous waste and depletion of the environment (Ibrahim, 2013). Mule (2001) explains that African countries are victims of economic imposition, hindering sustainable development and limiting gains realised from globalisation. African countries have suffered from the imposition of dissembling development models, strategies, and policies by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the WTO, with a significant negative toll on political, economic, and financial sovereignty (Due and Gladwin, 1991; Lundvall and Lema, 2014; Mendes et al., 2014). Starting in the 1980s, the World Bank and the International Monetary Funds’ Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) had devastating social and economic consequences on the Africa states (Due and Gladwin, 1991; Mkandawire and Soludo, 1998; Heidhues and Obare, 2011). SAPs marked significant proof of how externalities of globalisation and attendant global capitalism propelled the African regional state’s shaping and indicated the need for African solutions to African problems. The multidimensional nature of contemporary regionalisation in Africa occurs in various forms, but it is mainly seen from an economic and financial perspective (Draper, 2010; Asongu et al., 2020). It also finds its interpretation in dominant regional integration theories, including neorealism, neo-functionalism structuralism, etc. Often, the ocean domain’s role in shaping the African region is ignored in scholarly analyses, yet global ocean regimes are involved in the making and breaking the region’s present and future.

Global ocean governance impacts African states differently: It triggers competition among states and leads to new ocean-related forms of crises. African countries have used ocean issues to compete and accrue political leverage among themselves, although this a more significant issue, as seen in the South China Sea or the Arctic. For example, the Extended Continental Shelf regime adopted under the 1982 UNCLOS has increased African states’ drive to increase their maritime domain, especially in their quest to explore and exploit known and anticipated mineral resources. Out of the 30 submissions (both complete and preliminary) made by African coastal states to extend their continental shelf after the 13 May 2009 deadline, nine contained potentially overlapping claims: Mauritania and Cape Verde, Senegal and Gambia, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, Sao Tomé and Príncipe and Cameroon, Guinea and Sierra Leone, Gabon, Congo, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia and South Africa, Mozambique and South Africa, Tanzania and Seychelles, and Kenya and Somalia (van de Poll and Schofield, 2010). This has created fierce competition and animosity amongst African coastal states as they strive to outsmart each other in providing scientific and technical evidence of the geological and geomorphological features of their prospective continental shelf. Likewise, commentators within and outside Africa think that instead of fortifying the African state, UNCLOS, in some ways, has bolstered the grip of international capital on the African state as they would have to depend on the Law of the Sea Tribunal or the International Court of Justice to seek redress. This would mean that a sizable amount of funds would be expended to file and hear a case at the Tribunal, including the costs of hiring competent Lawyers or Law firm, travel, accommodation, estacodes for government officials, etc. Webe (2012); Okafor-Yarwood (2015), Walker (2015); Moudachirou (2016) questioned UNCLOS ambiguities regarding maritime zones’ delimitation, emphasising that it creates more problems than it resolves in Africa. Despite the safety nets for peaceful resolution of maritime boundary disputes provided by Article 298 of UNCLOS (Sim, 2018), maritime boundary disputes still pose the most dangerous potential for conflict between the African states. Several cases in question include the maritime dispute between Mozambique and Tanzania (Mlimuka, 1994), Nigeria and Cameroon (Merrills, 2003), Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire (Peiris, 2018), and recently between Kenya and Somalia (Bryant, 2021).

Apart from spurring competition, ocean issues have also enabled African states to act collaboratively at the regional level and forge a common position globally. For example, in the spirit of brotherliness, member states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) agreed in 2009 to cooperate on issues of the limit of their extended continental shelf and write a “no objection note” to the submission of their neighbouring states.1 Also, several bilateral agreements have been reached between the African states to settle years of maritime boundary disputes. Some African countries have even gone a step further from the bilateral agreements to introduce a Joint Maritime Development Zone (JDZ) concept to manage the resources within the previously disputed area. For example, in the early 2000s, Nigeria and Sao Tome and Principe established a Joint Development Authority to manage the resources in the area where their EEZs overlap (Eze, 2020). Seychelles and Mauritius, in 2012, also adopted this model to manage the area of the seabed and its underlying sub-soil in the Mascarene Plateau Region (Kadagi et al., 2020). Likewise, the idea of a Combined Exclusive Economic Zone for Africa is under consideration as proposed in the 2050 African Union (AU) Integrated Maritime Strategy.

However, to a large extent, solidarity, collective awareness, and ubuntu’s spirit2 drive African states to survive the competition spawned by UNCLOS’s boundary regime as; their drive to cooperate is solid because of their common struggle against slavery and colonial rule. This allows African states to present themselves as a voting block and a unified African voice during negotiations for ocean agreements and deliberation of global ocean governance initiatives. Following the 2010 introduction of the LMEs Concept as a tool for enabling ecosystem-based management in the world’s ocean, African states positioned themselves as a formidable force in the LMEs discourses with the formation of the African LME Caucus. At their inaugural meeting in Accra, Ghana, in May 2011, the African LME Caucus set out goals and objectives to “establish closer cooperation between African LMEs, by discussing common concern issues, sharing experiences and developing strategies to work together” (African LME Caucus, 2011, p. 3). This group has represented the African LME projects’ interests at the annual LME meetings and other international fora and has developed a paper on Africa’s needs for a marine research platform. Prominently, the formation of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) in 1985 provided the necessary guidance and platform to articulate African interests in multilateral environmental agreements. In its objectives toward enhancing governance mechanisms for ecosystem-based management of the African ocean, the AMCEN has repeatedly called on various multilateral organisations and countries in the Global North to fulfil their ocean-related commitments. At the third meeting of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) held in December 2017 in Nairobi, Kenya, African countries through the AMCEN adopted 11 resolutions to accelerate action and strengthen partnerships on marine litter microplastics, among other challenges (AMCEN, 2019). AMCEN has also helped develop Africa’s common position in climate change agreements producing a relatively new governance structure at the continental level, including the Committee of African Heads of State and Government on Climate Change and the African Group of Negotiators on Climate Change (AGN). Since the 1st session of the Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) on a new international legally binding instrument to sustainably conserve biodiversity in ABNJ under UNCLOS, the African Group has taken several positions on behalf of the continent. These positions are mainly related to the negotiation mode, monetary and non-monetary benefits, complementarity of Area-based Management Tools, traditional knowledge, EIAs requirements, financial, and social responsibility, etc. (IISD, 2018, 2019).

Sometimes, this solidarity also extends beyond the shores of the African continent to include Pan-Africanist3 ideology. For example, in the build-up to the WTO’s 11th Ministerial Conference held in late 2017, the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) Group of countries expressed their collective position on the negotiations for fisheries subsidies. They were sturdily against providing subsidies for large-scale commercial fishing activities but canvassed for support to developing countries and LDCs for coastal fishing activities related to artisanal, small-scale, and subsistence fishing within their EEZ (Bahety and Mukiibi, 2017).

Many ocean challenges in Africa have also been linked to global security concerns. The spate of illegal maritime migration, piracy and armed robbery at sea, IUU fishing, transhipment of narcotics, and other illicit maritime crimes has brought African countries face-to-face with international interventions and measures with significant implications on states’ territorial integrity and sovereignty (Hamad, 2016; Brits and Nel, 2018; Okafor-Yarwood, 2020; Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020). Measures such as joint military training exercises and intelligence gathering imply that African states and their citizens are constantly placed under surveillance, while foreign agencies and individuals are enabled to become surveillance states to protect “maritime assets.” A particular case can be cited from the Horn of Africa. From 2008 through 2011, all eyes were on Somalia as it became the hotspot for piracy in the Gulf of Aden. The UN Security Council, through resolutions 1816, 1838, 1846, and 1851, made it its explicit purpose to protect the Gulf of Aden’s maritime space at all costs by allowing warships to enter Somali territorial waters. This intervention turned Somalia into a chessboard for global superpowers and maintained their influence more broadly in the region (Weldemichael, 2019). Yet, the internal and external factors that allowed piracy to flourish in Somalia, such as illegal fishing by non-Africans, dumping of toxic waste, international shipping corridors, ineffective security structure, Eritrea’s hostile relationship with Ethiopia, and Somalia’s instability, were left unattended – prompting Menkhaus (2009) to argue that policies of Western countries helped fanned the flames of conflicts and insecurity in Somalia. Central, therefore, to Somalia’s problems and the region is the inextricable relationship between the West’s economic and political interests (Menkhaus, 2008; Beri, 2011), which explains why there was an international consensus to dominate Somalia’s maritime domain at all cost. Several multilateral agreements and multi-stakeholder dialogues such as the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development; 1998 Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making, and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, commonly known as the Aarhus Convention; and 2002 Johannesburg World Summit for Sustainable Development have defined new forms of relations between actors at regional and international level. Furthermore, these global platforms have institutionalised multi-stakeholder processes for ocean governance at the regional and regional levels. For example, efforts to implement principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on public participation, information sharing and justice in the environmental matter are exemplified in several African high-level documents related to the ocean, including the 2003 African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resource; the AU 2050 African Integrated Maritime Strategy; the AU Blue Economy Strategy; etc. African countries are now domesticating these efforts to strengthen public participation in evaluating Environmental Impact Assessments and Strategic Environmental Assessments. Madagascar now conducts a public hearing and seeks advice from concerned stakeholders before the developmental project is granted (IUCN, 2004).

Regional Ocean Governance: Pertinent Policy Domains of Concern

Various regional cooperation forms peaked around the late 1980s and early 1990s, particularly intense in the Global South, where different overlapping bilateral, sub-regional, and regional economic and security arrangements emerged (Kacowicz, 2018). In the realm of international law and policy, the development of regional governance for environmental protection and natural resources sustainability is considered to be a cornerstone (Rochette et al., 2015). Here, the author defines ROG as the institutionalisation and coordination of efforts geared at common coastal and marine challenges with cumulative effects and linkages to ecological, social-political, and economic issue areas, involving different actors, via binding or non-binding rules, regulations, actions, strategies, and policies that regionally mandated organisations enforce. Nonetheless, there is variation in the level of cooperation and coordination between ROG mechanisms (UNEP, 2016). Therefore, institutions saddled with ocean affairs responsibilities at the regional level take many forms with differing mandates.

In contrast, some are exclusively developed to attend ocean-related matters or passively engage in ocean activities as part of their much broader functions (Tarmizi, 2010). Considering the successes, challenges, cooperation efforts of available ROG mechanisms, three different structures are recognisable (UNEP, 2016): (1) Regional Seas programmes, many of them supported or coordinated by the UNEP; (2) regional fishery bodies (RFBs), some established under the framework of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) while some are quasi-independent (e.g., Fisheries Commission of West and Central Africa); and (3) LME mechanisms, including projects supported by the Global Environment Facility (UNEP, 2016; Holthus, 2018; Adewumi, 2020b,c). Though there are other schemes of ROG in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, by far, the European Union (EU) case stands out–where ocean policies increasingly incorporate regional measures, making regionalization of maritime governance more effective (van Tatenhove et al., 2015).

Regional Maritime Security Governance

The concept of security governance and the notion of security entails the production of mechanisms steered by states and non-state actors (Kacowicz, 2018). Maritime security is a broad issue area in ocean governance. It encompasses physical, environmental, and human security at the coast and offshore. Regional security governance is supposed to contribute to a multilateral (global) security system (Söderbaum, 2016). However, the nature, context, and contemporary realities of maritime security governance at the regional level indicate that interventions carried out by regional apparatus, but within UNCLOS and international law framework are better to effect changes (Paik, 2005; Sandoz, 2012; RSIS, 2017). Also, despite several impediments confronting regional organisations (e.g., political will, coordination, funds, etc.), they have increased their relevance in maritime security issues, including piracy, armed robbery at sea, IUU fishing, narcotics, arms, and human trafficking in compliance with various international processes and institutions. On piracy and armed robbery at sea issues, regional actors in several hotspots have unfolded institutionalised maritime security architectures and coordination mechanisms that are not inspired by any UN Security Council resolutions but comply with other UN processes such as IMO. For example, Yaoundé Code of Conduct, the Heads of States Declaration and the Memorandum of Understanding between regional organisations initiated by the Gulf of Guinea Commission and leaders from the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), ECOWAS, inspired the creation of the Yaoundé Architecture. It provides joint operations, intelligence sharing, and harmonised legal frameworks between West and Central Africa countries toward combating various illicit maritime activities. Besides these structured mechanisms, countries are also working on an ad hoc basis.

Regional Ocean Environmental Governance

Improvements in managing and governing oceans help maintain ecosystems’ integrity and upgrade ocean environments, thus building environmental sustainability (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). As far as marine biodiversity is concerned, namely protecting and preserving endangered species or threatened ecosystems, existential uncertainties still abound and are yet to be adequately addressed by existing global/international frameworks. The responsibility to protect the marine environment effectively is at the centre of GOG (Töpfer et al., 2014). However, several loopholes exist within GOG mechanisms that have left the marine environment vulnerable to market forces. For example, UNCLOS’s creation of the global commons opens the high seas to the danger of market forces (Thiele and Gerber, 2017), and the take on non-discriminatory trade-restrictive measures position of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas toward non-parties gives room for fishing interests responding to large markets to trample upon best conservation efforts (SITFGPG, 2006). Likewise, a range of market policy failures has encouraged under-investment or no investment at all in activities necessary to sustain the marine environment, while on the other hand promoting over-investment in activities that undermine the marine environment (UNDP, 2017). Ocean industries are often held accountable for their impacts on the ocean by both states and non-state actors (Holthus, 2018). Another dicey but apposite argument aligns with environmental and ethical concerns emanating from climate change and the ocean interplay. Garrad (2018) argues that global governance regarding environmental regulation now faces the increasing demand for balancing the development and industrialisation of emerging economies to manage global emissions.

Although environmental sustainability of the ocean is global (Visbeck et al., 2014; Holthus, 2018), the most effective and recognised approaches to combat the wide range of marine environmental issues (e.g., Ecosystem-Based Approach, Marine Protected Areas, Marine Spatial Planning) are normatively and contextually tailored to the needs, drivers, and aspiration of the people (Röckmann et al., 2017; Keijser et al., 2018). “One-size-fits-all” solutions for the ecosystem approach are neither feasible nor desirable (UNEP, 2016) because coastal areas and communities are vulnerable to changing environmental conditions and will have to prepare for and adapt to their effects (Avery et al., 2011). Hence, regional governance development to protect the environment and its biodiversity is unquestionably a cornerstone of international environmental law and policy (UNEP, 2016).

Fortunately, all regions have at least some arrangements covering specific issues or a wide range of issues relating to marine biodiversity, fisheries, and pollution, etc. (Mahon and Fanning, 2019b). For instance, under the Regional Seas Programmes, the Abidjan and Nairobi Conventions, in cooperation with other regional and international partners, are committed to advancing the Ecosystem-Based Management approach to ocean governance in Africa, applying marine spatial planning (MSP). Since 2017, the Abidjan Convention Secretariat currently co-implementing the Mami Wata regional MSP project (Mami Wata, 2018) has already constituted a Working Group to improve MSP regional capacity and share best practices. Meanwhile, decisions to support MSP development for sustainable development of the Western Indian Ocean’s blue economy have been agreed upon by parties in the Nairobi Convention (UNEP-Nairobi Convention, 2015).

Regional Ocean Economic Governance: Maritime Trade, Investment, Development, and Cooperation

Regional ocean economic governance is not a new topic. It has gained traction, particularly with the unsettled yet continued power imbalances and diffused international financial order (Girvan, 2007; Drezner, 2012; Boughton et al., 2017), as well as the recalibrations of regional integration rooted within the broader framework of social-political change and trade liberalisation (Jones, 2001; Doidge, 2007; Jiboku and Okeke-Uzodike, 2016). The 2008 global economic crises exacerbated the former (Young et al., 2013; Boughton et al., 2017), while the latter predominantly emanates from the scope of developmental regionalism and the paradigm of market-led regional integration (Doidge, 2007; Draper, 2010; Jiboku and Okeke-Uzodike, 2016). Perhaps, one of the earliest official forms of regional ocean economic governance is the defunct EU Community Fisheries Agreements (CPAs) of 1976, which has now metamorphosised into the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) (Failler, 2015). Other private regional economic governance also exists, for example, in the South Pacific, where some tuna agreements are managed by the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency, which since 1979 has facilitated regional cooperation (FFA, 2020).

Therefore, besides the growing importance of marine resources to regional economies, today’s conception of regional ocean economic governance is a consequence of the fragile and uneven processes of global maritime trade and investment and the realisation of a new maritime trade and investment paradigm capable of keeping pace with regional economic realities, integration and interdependence. Hence, regional ocean economic governance could be an economic process in which internal and external states of affair pushes rapid growth in intra-regional maritime trade, investment, agreement, and interest at the expense of the region’s maritime trade and investment with the rest of the world.

Although the wicked problems confronting today’s ocean warrants global cooperation, the ability of multilateral trade and investment institutions to deliver the policy coordination needed to stem the tide appears sub-optimal. The existing multilateral trading systems (e.g., the WTO, the 2009 UN Convention on the contract of international goods transported wholly or partially by sea, the UN Convention on transit trade of landlocked states of 1965, and the Convention on the facilitation of International Maritime Transport of 1965) are only clasping under past successes. They have proved relatively ineffective in dealing with the global ocean economy’s current challenges (OECD, 2016). For instance, the WTO has struggled over the past 20 years to end certain fisheries subsidies estimated at $20 billion that directly contribute to IUU fishing, overfishing overcapacity (Sumaila et al., 2019; UNCTAD, 2019). Ab initio, the lack of clarity of the UNCTAD financing, trade, integration, technical assistance, and shipping policies have also been raised. The criticism includes that its resolutions, memoranda, and agreements have, in principle, hindered the desperate need for developing countries to expand exports, furthering the South and North divide (Howell, 1968; Anis, 1972; Ramsay, 1984). Likewise, the argument that global governance benefits powerful economies’ interests in several ways is also recurrent (Graham and Litan, 2003; Maal, 2013). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought in a new form of cooperation between UNCTAD, Africa, and four other regions. UNCTAD has been working with the UN Regional Economic Commissions for Africa (ECA) on a three-cluster technical assistance project on transport and trade connectivity in times of COVID-19 to help countries “build better” in a Post COVID-19 world (UNCTAD, 2020). Also, African countries’ stories of participating actively in the global economy, but always marginalised and not benefiting fully, are not new (Ndikumana, 2015). This realisation has prompted the emergence of the agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a regional economic policy geared at easing international trading on Africa’s market while projecting the continent as an active participant in the global economy (Fofack, 2018). It commits countries to become critical maritime trade partners due to what Asongu et al. (2020) described as “globalisation-fuelled regionalisation,” focussing on the spirit of African solidarity, tariffs reduction, and the elimination of measures that inhibit cross-border trade.

Regional Socio-Political Ocean Governance: Sustaining and Improving Livelihood, Preventing Irregular Migration, Integrating Integrity, Human Rights, and Gender

Response to security, environmental and economic needs is not what regionalism and regional governance are all about (Kacowicz, 2018). Addressing the dynamics of social, environmental, economic, and political processes is vital in improving governance (UNDP, 2017). Ba and Hoffmann(eds) (2005) opined that the extent of political exercise taking place makes us aware of regional governance’s political aspects within the context of either conflict or cooperation. Perhaps, this is what prompted Avery et al. (2011) to believe that the prospect of future progress in ocean governance and strategies must fit within both social, economic, and geopolitical constraints.

In a 2017 report, the UNDP affirmed that ocean governance’s essential issues relate to how various interests are represented and how decisions are made, and the roles of power and politics (UNDP, 2017). It is, however, clear that regions of the world (e.g., Africa, Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Americas) are all aiming at ROG systems that can be considered not only efficient in tackling 21st-century oceanic challenges but also enhancing social capital, promoting inclusiveness, sustaining democratic values, human right and legitimacy. According to Pendleton et al. (2015), the reasons for this are not farfetched: marine ecosystems are highly interconnected and are spatial units defined by specific characteristics; also, the management of human activities in the marine environment is organised along political boundaries.

Meanwhile, issues bothering irregular maritime migration have been pushed to the top of the political agenda in North America, Europe, and Australia with the global refugee regime facing profound and threats and hostility. Many so-called sustainable solutions offered by international organisations and migrant rights advocates are unfeasible and politically untenable (Carling et al., 2015). However, regional governance actions appear to be the best bet in solving irregular maritime migration issues, as the causes of these issues can only be fully understood and managed in the context of domestic politics (McAuliffe and Mence, 2014). For example, the Yaoundé Code of Conduct4 provides a solid strategic and operational framework to curb the spate of illegal maritime migration within the waters of countries in West and Central Africa.

The Nexus Between ROG and GOG

Visbeck et al. (2014) and Töpfer et al. (2014) had earlier put forward what they perceived as the nexus and complexity between ROG and GOG. The former strongly argues that advancing a single (political or legal) global framework and coordination is needed for regional approaches to be practical due to ocean ecosystems’ global connectivity. The latter posits that global authorities and frameworks operate in isolation and have failed to use their full collective potential, resulting in the lack of institutional cooperation at both global and regional levels. This section is mainly concerned with the central research question: what are the possible linkages between ROG and GOG? For this question to be answered, a fivefold taxonomy of links between ROG and GOG is developed using an analytical approach that draws ideas and concepts from several pieces of literature on institutional interplay, complexes, and fragmentation of governance (Abbott and Snidal, 2009; Biermann et al., 2009; Keohane and Victor, 2011; Pattberg et al., 2014; Nolte, 2016; Isailovic et al., 2013). The evidence from these pieces of literature enabled identifying some level of cooperation or conflict pattern between regional and global ocean governance regimes. At the same time, the systematic analysis presented in previous sections of this paper (sections “Regional Ocean Governance: Pertinent Policy Domains of Concern,” “Regional Maritime Security Governance,” “Regional Ocean Environmental Governance,” “Regional Ocean Economic Governance: Maritime Trade, Investment, Development, and Cooperation,” and “Regional Socio-Political Ocean Governance: Sustaining and Improving Livelihood, Preventing Irregular Migration, Integrating Integrity, Human Rights, and Gender”) indicates the possible conflicts and synergies that exist between regional and global ocean governance (regarding divergent opinions, and principally in response to the forces of globalisation, contextual challenges, and regionalisation push).

Biermann et al. (2009) proposed three criteria (the degree of institutional integration and degree of overlaps between decision-making systems; the existence and degree of norm conflicts; and the type of actor constellations) to describe the degrees of fragmentation in global governance as synergistic, cooperative and conflictive. Similarly, an account of other empirically driven attempts at defining various taxonomies of linkages in the international and emerging transnational level of governance exists – including the regime complex approach by Keohane and Victor (2011) and the governance triangle approach by Abbott and Snidal (2009). Keohane and Victor (2011) approach is based on the description of a continuum of regulatory systems being on the one end – fully integrated with a detailed level of rules, in the middle – “nested regimes with identifiable cores and non-hierarchical but loosely coupled systems of institutions,” and the other end – fragmented, weak and lacklustre.

Meanwhile, Abbott and Snidal (2009) focussed on emerging modes of governance within a transnational regulatory space bounded by voluntary norms and standard arrangements. Their governance triangle approach focuses on mapping the strength and weakness of participation of three key actors (or a combination of actors), including the national states, institutions, and NGOs, on identifying the categories of arrangements in a particular transnational governance architecture. Building on three criteria from Biermann et al. (2009); Pattberg et al. (2014), for their part, included “discourse constellations” as additional criteria to understand the causes of fragmentation in global governance architecture – implying the level of competition or overlap discourses within an issue area. These four criteria are employed in this paper as indicators or analytical dimensions to create the taxonomy of linkages between regional and global ocean governance architecture (see Table 1). These criteria are adapted because they focus on different explanatory variables (including the role of power, interest and knowledge) critical to understanding the differences between degrees of fragmentation in governance and have complementarities that can conceptualise the nature, causatives and consequences of fragmentation in GOG.

However, to present the taxonomy of nexus between regional and global ocean governance, this section adopts the categorisation developed by Biermann et al. (2009) in their work on climate change governance and the Nolte (2016) study on comparative perspective in regional governance to distinguish between the different patterns of interaction between regional and global ocean governance. Biermann et al. (2009) differentiate between three different kinds of relationships that can occur in governance, including: (1) synergistic (in our case symmetrical), (2) cooperative, and (3) conflictive (in our case frictional). Nolte (2016) adhered to the synergistic, cooperative, and conflictive categorisation but introduced the fourth type of difference as “segmented” (in our case discrete) on the premise that consequences of fragmentation in governance might lead to neither cooperation, synergy, nor conflict but a new form of relationship between different governance components. However, the author adds a fifth category, “ambiguous,” arguing that the relationship between regional and global ocean governance is not clear-cut, particularly considering fundamental issues concerning past antecedents, trust, legitimacy, and national sovereignty.

Finally, a fivefold taxonomy of how the links between ROG and GOG is presented along the relationship spectrum being discrete, conflictual, cooperative, symmetric, and ambiguous (see Figure 2 and Table 2). This typology represents a set of logical possibilities or hypotheses on what types of nexus exists and could exist between regional and global ocean governance. Evidence from literature, a systematic analysis of GOG in the face of globalisation and the emergence of Africa’s ROG, and the general analysis of four policy domains of ocean governance mentioned earlier (maritime security, ocean environment, ocean economy, and socio-political dimension) lay the basis for identifying a typology of relationship between ROG and GOG mechanism. They provided the platform to diagnose the most prevalent arguments (e.g., Fazekas and Burns, 2012; Hofferberth, 2016; Meltzer, 2021) that regional governance’s effectiveness is directly related to the nature of the interaction between regional governance schemes and global governance; and vice-versa.

Figure 2. Nexus between ROG and GOG architecture with the degree of relationship and degree of fragmentation.

Discrete: The Dominance and Strategic Nature of GOG Frameworks Tending to Limit ROG

A discrete link between ROG and GOG is seen as a somewhat compulsive situation when (a) the norm, principles, and decision-making arrangements of GOG are satisfying, (b) regional institutions are too weak and need to rely on GOG to sustain them, and (c) credible alternatives are absent due to differing geographic, economic, and political interests. Though this might change due to shifting global dynamics (e.g., shifting geographic trade patterns, emerging economic powers, environmental dynamics, etc.), states in each region might connect directly to GOG rather than developing or strengthening regional schemes by themselves. The argument here is that it is only logical that, provided that some GOG schemes are presenting satisfactory regulation and measures, the tendency will be for there to be a little drive for regions to contemplate establishing or nurturing new ROG schemes. An example of this is evident in the policy domain of maritime shipping and trade through the regulations of global frameworks such as the UN Convention on the contract of international goods transported wholly or partially by sea (2009 Rotterdam Rules), the UN Convention on transit trade of landlocked states (1965), the Convention on the facilitation of International Maritime Transport (FAL Convention-1965), and even the WTO). Although downturn cycles are typical in the shipping industry (Stopford, 2009), the industry was particularly hard hit by the last global economic meltdown 2008–2019. Interestingly, the dynamics of the global free market offered by the G20 (Group of 20) crept in, allowing the shipping industry to regulate itself over time from the market downturn and to restore its balance regarding operation activities and costs, earnings from operating activities (Bhirugnath, 2009). Contrarily apart from the EU, such proactive actions did not surface at the ROG level to salvage the shipping industry.

Also, the increasing availability of trans-continental groupings and alliances whose operations are based on sectoral issues and similar development concerns, rather than geographical proximity, might limit the proliferation of the regional ocean agenda on specific problems but could lead to silos. For example, the Africa-EU Partnership has some of its focus on maritime migration and mobility, strengthening maritime security and peace; likewise, the ACP Group of States addressing issues of mutual concern through the Cotonou Agreement.

Frictional Relationship: ROG as a Form of Partial Objection to GOG

Here, a frictional relationship between ROG and GOG depicts a conflictive situation where an ocean policy domain is characterised by governance or institutional systems that: (a) are hardly connected or have different, unrelated norms and decision-making procedures guiding them, and (b) there are conflicting sets of drives and principles. The post-second World War and post-colonial era ushered in increased interest in national sovereignty and national governance capacity (Zürn, 2011; Held, 2018; Mahon and Fanning, 2019a). However, in the face of economic, social, environmental, and technological pressure and changes, the exigencies of “sovereignty” itself have begun to give way and become secondary, while the need for union and creation of international/supranational structures has heightened (Borgese, 1999). This is also exacerbated by the need to solve everyday challenges, especially those deemed transboundary. Hence, a frictional link between ROG and GOG appears to be a reactionary impetus to challenge what is perceived as towering supremacy, dominance, and subjugation of global mechanisms of ocean governance, and of course, coupled with the combination of regionalist/nationalist drive and need to overcome everyday challenges and capitalistic domination.

Nonetheless, propagating regional cooperation and developing regional [ocean] governance mechanism seems like a logical policy embrace for countries in the Global South as a way of displaying independence and self-sufficiency (Kacowicz, 2018). Now, old top-down ways of working, in which international organisations see themselves as the primary sources of ocean governance approaches that are transferred to states (particularly in the Global South), are no longer valid (see Jamal, 2016; Walker, 2018). There is now a better understanding of how marine management is conceived, which recognises that approaches have multiple sources (WWF/UN-ESADSD, 1999, p. 7). Marine Management and governance are now seen as part of a collective effort to create new technical and social options that rely more on local knowledge and less on a “one-size-fits-all” formula. Hence, the development of ROG schemes that enhance working in partnerships has become much more critical. Recent developments, such as the adoption of the 2050 Africa Integratedrrelated Maritime Strategy (AIMS), indicate that African states are increasing their capacity to tailor effort to the needs and realities of the region amidst new, shifting global dynamics (e.g., patterns in geographic trade, economic powers, environmental dynamics, etc.). As proposed in the AIMS, the quest to establish a Combined Exclusive Maritime Zone of Africa (CEMZA) – a common African maritime space devoid of barriers – is a transformational concept aimed at accelerating joint management, intra-African trade, and making administrative procedures in intra-Africa maritime transport more attractive, efficient, and competitive, as well as to protect the ocean.

Cooperative Relationship

The author speaks of a cooperative link between ROG and GOG when these ocean policy domains are characterised by (a) different institutions, actors, norms, principles, and loosely integrated decision-making procedures, (b) institutional norms and principles are related, and actors are unclear; and (c) there are core institutions that do not comprise all actors that are important in the policy domain. Also, the argument for this type of link is that ROG and GOG are in constant interaction, and a mutual relationship operates where the two systems are dedicated to addressing the sectoral or integrated marine issue(s), bringing individual experiences and resources, cross-fertilising ideas, and learning from each other (Campbell et al., 2016; Marine Regions Forum, 2020). Apart from the marine ecosystem not respecting respective national and legal boundaries, the oceans have connected cultures, civilisations, and commerce for a long time (McPherson, 1984; Al-Rodhan, 2017). The world has even transformed from being a “global village” to a “common area,” thanks to the advent of supercomputers and different cutting-edge technologies. This has aided networking between regulatory agencies, inter-government exchanges, and learning from counterparts (Zurn, 2003).

Therefore, the possible link between ROG and GOG might exhibit cooperation on common or overlapping interests and issues. This type of relationship has been more pronounced around maritime security and economic policy domains, maritime security and socio-political policy domains, and environmental and socio-political policy domain. With this type of relationship, policies are defined, decided, and monitored through different or core GOG institutions and individual ROG institutions that might not be affiliated with the core GOG institution.

A look at the ocean space shows that parallel processes of ROG and GOG are geared at fisheries, maritime security, migration, shipping, and conservation. For instance, on shipping issues, regional and global governance might interact in complex ways where ab initio, the preconditions enshrined in IMO’s regulations and protocols, might set the tone for cooperation. When this global precondition merges with regional concerns and needs, there might be a reinforcement of the two systems leading to healthy and seamless cooperation and even institutionalisation. For example, the MoU on the Establishment of a Sub-regional Integrated Coast Guard Function Network in West and Central Africa led to strengthening cooperation between the IMO and the Maritime Organisation of West and Central Africa. This type of relationship becomes contrasting and complex on maritime security issues, particularly when issues of national sovereignty vis-a-vis dimensions of regional and global security come into play. A case in question is in the Gulf of Guinea, where countries in the region have countered any idea of a Gulf of Aden-styled intervention where foreign militaries were allowed to intervene against maritime piracy (Osinowo, 2015; Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2021). Also, cooperation between regional and global ocean governance in Africa is evident through UNEP and the AU. On many fronts, UNEP cooperates with the AMCEN to develop and implement different AU processes geared at integrated management and governance of Africa’s maritime domain. For instance, UNEP’s Regional Seas Programme – the Barcelona Convention, Abidjan, Nairobi Convention, and Jeddah Convention are recognised regional platforms through which the AU intends to implement its Africa Integrated Marine Strategy 2050 and its Agenda 2063 on Ecosystem-Based Management Approaches (including Marine Spatial Planning) for marine resources within Member State’s EEZ (UNEP- Nairobi Convention, n.d.).

Symmetrical Relationship: ROG as a Component of GOG

The symmetrical relationship between ROG and GOG is conceived as situations when (a) the GOG includes (almost) all ROG mechanisms and (b) it provides for practical and detailed general principles that regulate the policies in different yet substantially integrated governance arrangements. The logic here is that ROG is a subset of GOG working in tandem in a synergistic relationship. This type of relationship allows for ROG initiatives to emerge into governance mechanisms recognised and embodied within the GOG arena. The importance of regional organisations and conventions for ocean affairs within and outside the UN system has grown as bases for action (Grip, 2016), where regional arrangements are connected to a global arrangement or programmes (Mahon and Fanning, 2019b). For example, Regional Seas Programmes, Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (FMOs), Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) MOUs, IMO Port State Control MOUs, etc., are all subsets of the UN ocean governance system. The need for this is that local strategies and planning would be insufficient because of the dynamics of global influence conditioning the regional seas and oceans (Henocque, 2010). Embracing this link allows for two-way piping of knowledge and understanding about the ocean in terms of gaps, challenges, opportunities, current status, threats, and solutions (Durussel et al., 2018). This thinking is substantiated principally on the principle of subsidiarity or social organisation – positing that governance activities occur at the most practical level, whether local, national, regional, or global.

Concerning governance of the ocean arena, UNCLOS (Article 197) already set the tune for another kind of symbiotic relationship between ROG and GOG upholding that states shall cooperate on a global or regional basis, either directly or through international arrangements, in formulating and enforcing rules, standards, procedures for the management of the marine environment, taking regional characteristics and features into account. Therefore, GOG goals and actions should accentuate multi-layered and multilateral logic based on a harmonic relationship with the regions and their actors. For example, while providing a platform for regions and states to agree on fisheries management, RFMOs occupy a critical position in resolving fisheries crises, particularly per the 1995 UN Fish Stock Assessment Agreement.

Following the principle of subsidiarity, systems of ROG appear as building blocks of all-encompassing GOG. Regional Seas schemes such as the Abidjan and Nairobi Conventions supervised by UNEP; Regional Fisheries bodies such as the Sub-regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC), South East Atlantic Fisheries Organisation (SEAFO) supervised by FAO; and the GCLME, CCLME, BCLME facilitated by several UN agencies are another layer of stones in the overall architecture of GOG.

Likewise, as the timing of treaty development usually corresponds with global interest in each topic (Al-Abdulrazzak et al., 2017), the AfCFTA regime is symmetrical with rules of other multilateral systems in some aspects. Some substantive areas covered in the AfCFTA have made disciplines of the WTO part of the deal, such as the trade remedies, safeguards, and standard administration.

Ambiguous Relationship: Bewilderment of ROG at the Shift of GOG Systems