95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 08 April 2021

Sec. Marine Pollution

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.619087

Eutrophic water bodies in coastal estuary areas usually show saline-alkaline characteristics influenced by tides. The purification performance of traditional planted floating beds in this water body is limited because of the poor growth of plants. A novel integrated floating bed with plants (Iris pseudoacorus), fillers (volcanic rocks and zeolites), and microbes named PFM was established, and the pollutant removal performance was studied. Results showed that the average ammonia nitrogen (NH4+-N), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and permanganate index (CODMn) removal efficiencies of PFM were higher with the value of 81.9, 78.5, 53.7, and 72.4%, respectively, when compared with the other floating beds containing plants (P), fillers (F), microbes (M), and plants and fillers (PF) in this study. Therein, the most of NH4+-N (30.1%), TN (27.9%), TP (22.5%), and CODMn (43.6%) were removed by microbes, higher than those removed by plants and fillers. Analysis of the microbial community revealed that the establishment of PFM led to a higher microbial richness than M, and Acinetobacter, as the main microbes with the function of salt tolerance and denitrification, were dominated in PFM with a relative abundance of 6.8%. It was inferred that the plants and fillers might enrich more salt-tolerance microbes for pollutants removal, and microbes favored the growth of plants via degradation of macromolecular substrates. Synergistic actions in the process of eutrophic brackish water purification were established. This study provided an idea for the application of integrated floating bed in eutrophic and brackish water bodies purification in coastal estuary areas.

Coastal estuaries are the ecotone of terrestrial and marine ecosystem with low water exchange rate, and susceptible to human activities. Thus, eutrophication is prone to occur. It is generally accepted that excessive nutrient input is the main reason of water eutrophication (Bhagowati and Ahamad, 2019). The consequences are the outgrowth of harmful algae, decreased light intensity, water body anoxia, and extinction of submerged plants and aquatic animals (Ma et al., 2019). More importantly, eutrophication may lead to serious health hazards to humans in various pathways. In addition to eutrophication, salt or brackish water bodies caused by NaCl or HCO3–-CO32– are also a challenge to the environment in coastal estuary areas. The growth of plants and microorganisms is inhibited under the influence of salt and alkali stress, and the self-purification ability of water bodies is restrained, resulting in a deterioration of waterfront ecological landscape (Zhao et al., 2005; Benzarti et al., 2014). Therefore, a suitable remediation method should be selected with the advantages of an effective water purification performance and the tolerance to salt and alkali when eutrophication occurs in the coastal estuary areas.

Integrated floating bed is an innovative water remediation technology developed from the conventional constructed wetlands. It is mainly composed of aquatic plants and microbial carrier packing. The plants in integrated floating beds grow in a hydroponic floating mass on the surface of water bodies, and the microbes are fixed mainly on the fiber fillers and plant roots (Li et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2016a). Integrated floating bed has been increasingly researched and applied to control the water eutrophication with the advantages of low investment, high efficiency, no additional land occupation, and flexible operation (Gottschall et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2020a). Wu et al. (2016) established the enhanced ecological floating beds with total nitrogen (TN), ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N), nitrate nitrogen (NO3–-N), total phosphorus (TP), and chemical oxygen demand (CODCr) removal efficiencies of 49.3, 49.2, 69.5, 48.7, and 70.6%, respectively. Olguín et al. (2017) assessed the performance of floating treatment wetlands for the water quality improvement of a eutrophic urban pond, and fecal coliforms and nitrate decreased by 86 and 76%, respectively, in 2 years. Nevertheless, most of the researches about integrated floating bed are related to fresh water purification according to previous studies (Huang et al., 2013; Abed et al., 2017), and the studies of integrated floating bed applied in coastal estuary areas for brackish water purification are limited. The stability of traditional floating bed is usually low in the actual application (Wang et al., 2020b), and it is a challenge to build a stable floating bed system.

Water purification would be achieved via the integrated floating bed with comprehensive effects of plant absorption, microbial degradation, and others (Wang et al., 2020a). Integrated floating beds have been applied in many field-scale river remediation projects, and the water purification processes indicated the synergistic effects of plants and microbes (Chang et al., 2012; Wang and Sample, 2014; Wang et al., 2015). Macromolecule pollutants would be decomposed into micromolecular substrates via enzymes secretion. On the other hand, some micromolecular substrates would be degraded by microbes, and others would be easily uptaken by plant roots (Wu et al., 2016; Urakawa et al., 2017). Meanwhile, the developed plant roots could provide the attachment sites for microbial growth, and oxygen released from plant roots would facilitate microbial growth and enhance biofilm formation (Keizer-Vlek et al., 2014; Saeed et al., 2016). The biofilm structure could resist lots of environmental stresses, such as salinity, pH, and toxic substance, and the interaction between microbes and plants in the integrated floating bed system would enhance the pollutants removal performance. There are diverse microbial communities in brackish aquatic ecosystems. In addition, lots of salinity-tolerance microbes could produce bioactive compounds and secondary metabolites to combat osmotic stress (Wang et al., 2020c). Nonetheless, the microbial community composition in brackish water ecosystems is poorly understood. Furthermore, Iris pseudoacorus is a common aquatic plant with a good landscape effect in the estuary area. It has been proved to have a high capacity to take up nutrients from the effluent water and retain N and P (Yousefi and Mohseni-Bandpei, 2010; Gacia et al., 2019).

The first objective of this study is to document the performance of the integrated floating bed for eutrophic brackish water purification in the coastal estuary areas. Six floating beds with different structures were established. The second objective is to evaluate the contribution of plants, fillers, and microbes for pollutants removal performance. The contribution rates of plants, fillers, and microbes to NH4+-N, TN, TP, and permanganate index (CODMn) removal were calculated. At last, the microbial community in integrated floating bed system were analyzed by 16S rRNA high-through sequencing, and the microbial diversity and structure were analyzed. Therefore, the third objective is to prove the synergistic action for water purification in the integrated floating bed in the aspect of microbial enrichment.

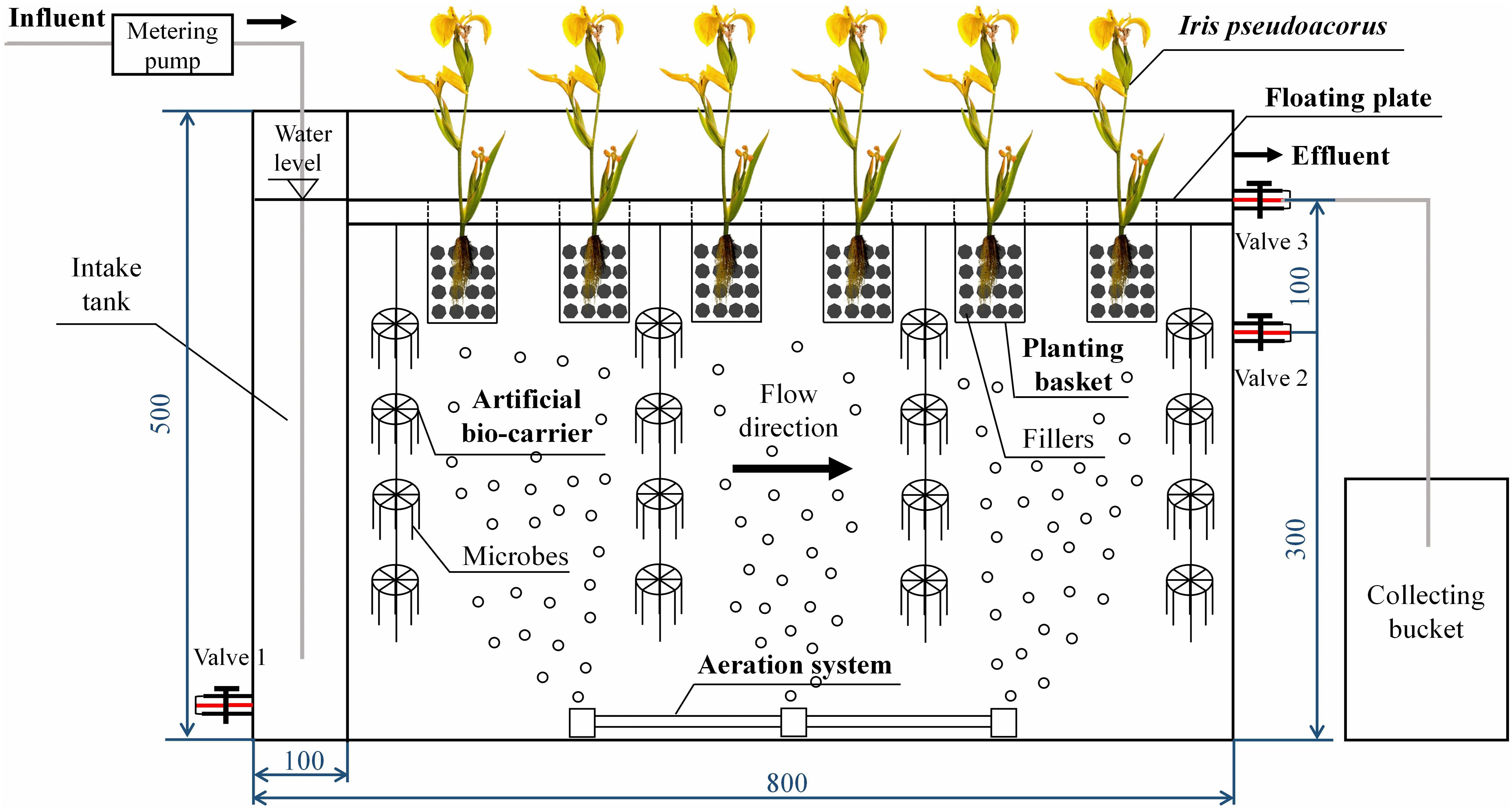

Six identical reactors were established with a size of 80 cm (length) × 20 cm (width) × 50 cm (height). The reaction zone was 70 cm × 20 cm × 40 cm and an effective volume of 56 L. The reactor consisted of a floating bed system, an aeration system, a water inlet system, and an effluent system (Figure 1). The floating bed system consisted of four parts: plants, floating plate, planting baskets, and artificial bio-carriers. A polyethylene foam board was placed in each device as a floating plate, and the size was 50 cm × 19 cm × 2.5 cm. Six planting holes with a diameter of 5 cm were set on each plate. The planting baskets made of 30 mesh gauze with a diameter of 5 cm and a height of 10 cm were installed in the holes. Fillers (30 g of volcanic rock and 30 g of zeolite) were placed at the bottom of each planting basket. Iris pseudoacorus was selected as the floating bed plant. It was planted in the basket and the root was fully in contact with the fillers (Figure 1). Four strings of artificial bio-carrier (aldehyde fiber) with the capability of enhancing microbial adhesion were hung under the floating plate, and each length was 35 cm. The artificial bio-carriers were hung for 3 days by the smoldering method before the start of the operation, and installed on the floating bed after the yellowish viscous biofilm appeared on them. An aeration system was installed at the bottom of the reaction zone.

Figure 1. Structure of the integrated floating bed. The integrated floating bed consisted of a floating bed system, an aeration system, a water inlet system, and an effluent system. The floating bed system consisted of four parts: plants, floating plate, planting baskets with fillers, and artificial bio-carriers.

The I. pseudoacorus was collected from the estuary areas of the Licun River. Before the reactor operation, I. pseudoacorus was cultured in water for 7 days, and the plants with a similar height and fresh weight were selected as the testing plants. The membrane-hanging microorganism was a compound microbial agent and an original bacterium concentrated one-generation probiotic powder provided by the Ningu Country Bacteria Password Biological Co., Ltd. NH4Cl, NaNO3, KH2PO4, and glucose were used to simulate the water quality of the estuary areas of the Licun River. The concentrations of NH4+-N, NO3–-N, TN, TP, and CODMn in the influent water were 3.6, 2.6, 6.2, 3.4, and 40.0 m⋅L–1, respectively. The salinity of the influent was 5‰, and pH was 8.0 (Table 1).

Six floating beds with different structures were constructed: plant floating bed (P), filler floating bed (F), microbe floating bed (M), plant + filler floating bed (PF), plant + filler + microbe integrated floating bed (PFM), and blank floating bed (CK). The operation time of the reactors was 31 days, and the dynamic test was carried out by continuous water inflow and effluent. The hydraulic retention time was 4 days, and the aeration rate was 0.8 L/min.

The plant characteristics were analyzed at the beginning and end of the operation for fresh and dry weight, water content, root activity, proline content, leaf relative conductivity, and chlorophyll content. The effluent of the six floating beds were analyzed after the start of operation, and the average concentrations and removal efficiencies of NH4+-N, TN, TP, and CODMn were calculated.

Plant height and root length were measured by scale. The fresh weight and the dry weight were determined by gravimetric method with an electronic analytical balance. Chlorophyll content, root activity, leaf relative conductivity, and root proline content were measured by N, N-dimethylformamide extraction, triphenyltetrazolium chloride method, immersion method, and acid ninhydrin colorimetry, respectively (Puniran-Hartley et al., 2014; Abdelaziz et al., 2017).

NH4+-N, TN, TP, and CODMn were measured by the Nesslerizatin colorimetric method, alkaline potassium persulfate-ultraviolet spectrophotometry, ammonium molybdate–antimony potassium tartrate–ascorbic acid spectrophotometry, and potassium permanganate method, respectively, according to the protocols described in the Chinese Standard Methods (State Environmental Protection Administration of China, and Editorial Board of Monitoring and Analytical Method of Water and Wastewater, 2002).

At the end of the operation, the fillers and artificial bio-carriers were crushed and mixed evenly with the effluent to prepare for DNA extraction. Total genome DNA from samples was extracted using the CTAB/SDS method. DNA concentration and purity were monitored on 1% agarose gels. According to the concentration, DNA was diluted to 1 ng/μL using sterile water. 16S rRNA genes of distinct regions (16S V4) were amplified using a specific primer (341F: CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG; 806R: GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT) with the barcode. All PCR reactions were carried out with the PhusionHigh-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs). Mix same volume of 1X loading buffer (contained SYB green) with PCR products and operate electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel for detection. Samples with a bright main strip between 400 and 450 bp were chosen for further experiments. PCR products was mixed in equidensity ratios. Then, the mixture PCR products was purified with the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Sequencing libraries were generated using the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations, and index codes were added. The library quality was assessed on the Qubit@ 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. At last, the library was sequenced on an IlluminaHiSeq2500 platform and 250 bp paired-end reads were generated.

The relative growth rate RGR (mg⋅g–1⋅d–1) was calculated as follows:

where W1 and W2 were the dry weight (g) of the plant at the beginning (t1) and at the end (t2) of the experiment, respectively.

In order to assess the role of plants and microbes in purifying eutrophic brackish water, the change of pollutant concentration in effluent was characterized by c/c0 based on the determination of pollutant indexes. c and c_0 were the concentration of effluent pollutant (mg⋅L–1) and influent pollutant (mg⋅L–1), respectively. The integrated floating bed removal efficiency ηPFM, other effects (aeration, illumination, etc.) removal efficiency, i.e., CK removal efficiency ηCK, filler removal efficiency ηF, plant removal efficiency ηP, microbe removal efficiency ηM, and synergistic removal efficiency ηS were calculated, respectively (Wang et al., 2012).

The average value, standard deviation, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were determined by using the SPSS software (PASW Statistics 20.0). The means were compared by using paired sample t-tests, and the significance level was p < 0.05.

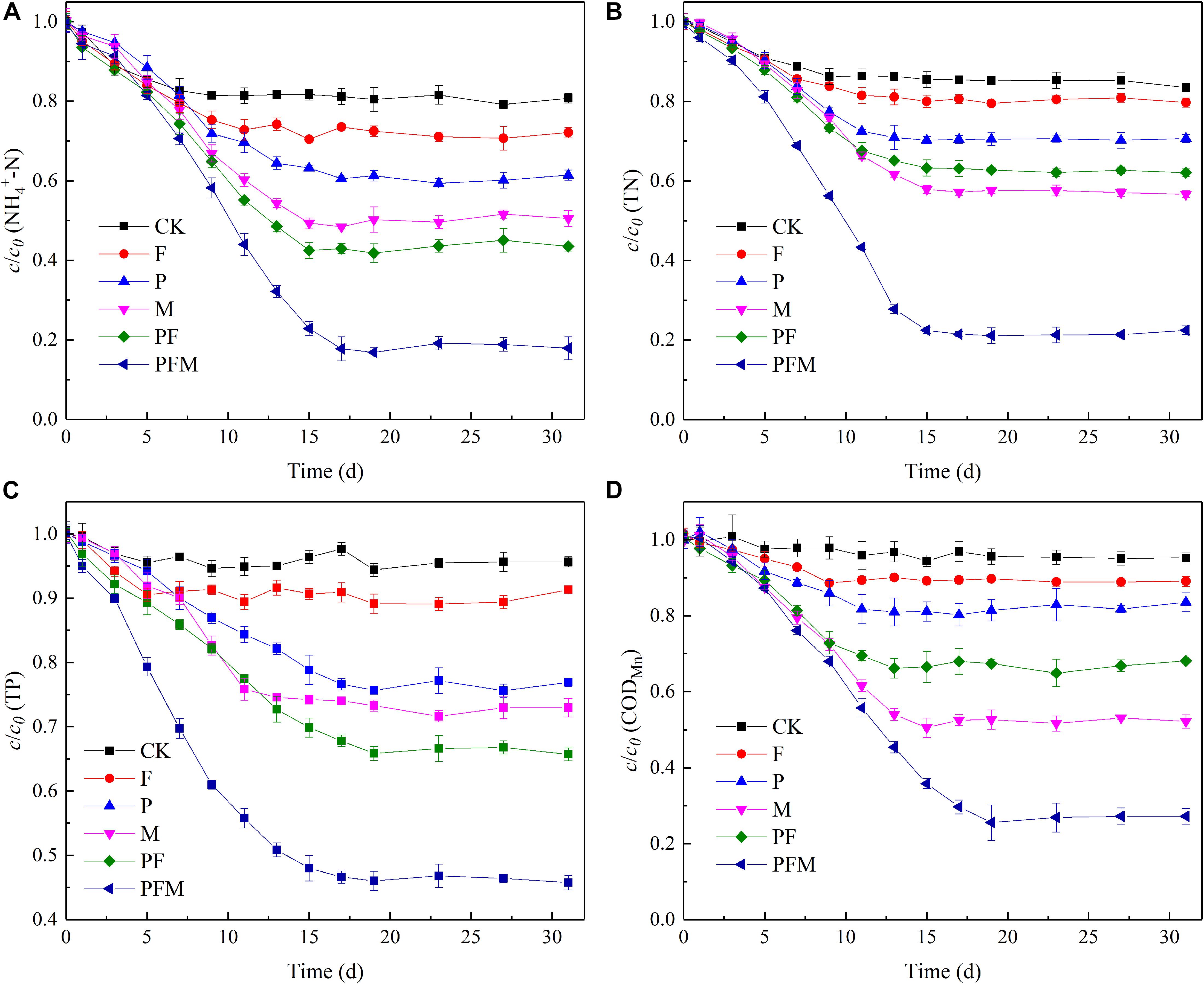

The concentrations of NH4+-N and TN in PFM decreased at the first 7 days, and gradually stabilized after Day 17 with effluent concentrations of 0.65 and 1.33 mg⋅L–1 and average removal efficiencies of 81.9 and 78.5%, respectively, higher than those of the other reactors. In addition, microbes and plants were the main reason for NH4+-N removal performance of PFM, ηM and ηP were 30.1 and 20.2%, respectively, at the end of the operation (Figure 2A). Similarly, the contribution of microbes and plants for TN removal performance was 27.9 and 14.9%, higher than the other factors (Figure 2B). The mechanisms of nitrogen removal in water mainly consist of physical adsorption, plant absorption, and microbial degradation. Zeolites are effective in the adsorption of ammonium as an ion exchanger. With the increase of other cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, the adsorption of the fillers was weakened and gradually maintained at a stable state (Wang and Peng, 2010). Plants could directly absorb and utilize NH4+-N to synthesize a variety of amino acids in an aerobic environment, while most NH4+-N is mainly converted into NO3–-N and NO2–-N by nitrifying bacteria. Most of the NO3–-N and NO2–-N are reduced to nitrogen during denitrification process by microbes, and others are absorbed and utilized by plants (Bartucca et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016a). In traditional plant floating bed systems, the growth rate and absorption capacity of plants limit the ability of pollutants purification, nevertheless, microbial nitrification-denitrification greatly improves nitrogen removal performance in the integrated floating bed (Sun et al., 2019). It was indicated that microbes may play a major role in the nitrogen removal process.

Figure 2. Change of pollutants concentration in different floating beds. (A) NH4+-N. (B) TN. (C) TP. (D) CODMn.

The effluent TP from P, M, PF, and PFM dropped sharply during the reactors’ operation, then tended to be stable, while changed less in CK and F (Figure 2C). The effluent TP in F gradually decreased at the first 5 days. After Day 5, the phosphate might be precipitated with the Ca2+ exchanged from fillers to be continuously removed (Karapınar, 2009), and reached a steady state, indicating that the adsorption of TP by the filler tended to be saturated at the end of the operation. In floating bed PFM, the effluent TP decreased sharply after Day 5, and basically stabilized after Day 17 (p < 0.05). Considering the effluent TP of PFM was the least, followed by that of PF and M, it was speculated that TP removal in the early operation period of floating bed PFM mainly relied on the absorption of plants and microbes, adsorption of the filler further enhanced TP removal performance of PFM at the first 5 days of operation (Guo et al., 2014). The results demonstrated the importance of plants and microbes for TP removal in floating bed systems.

During the reactors’ operation process, the effluent CODMn of F, P, M, PF, and PFM decreased continuously and tended to be stable on the 9th, 11th, 15th, 13th, and 19th day of operation, respectively (Figure 2D). The reactors of PFM and M obtained higher CODMn efficiency than others, and CODMn removal efficiency of PF was significantly higher than that of P and F. The results indicated the importance of microbes for CODMn removal in the floating bed system, and the obvious synergistic effect of fillers and plants for pollutants removal in the system. Based on the results above, it was indicated that the plants and microbes were the main factors for pollutants removal in the floating bed system, and the filler could enhance the pollutants removal performance with plants and microbes synergistically.

Plant growth and physiology are important factors for pollutant removal performance of plants. With the reactors’ operation, the roots of I. pseudoacorus penetrated the planting basket, plant height increased significantly with the growth of new shoots. In the three reactors planted with I. pseudoacorus, the plants in PFM obtained excellent growth characteristics with a relative growth rate (RGR), net increment of root length, and net increment of plant height of 11.59 mg⋅g–1⋅d–1, 9.31 cm, and 25.51 cm, respectively, at the end of the operation, significantly higher than those in PM and P (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The results indicated that fillers and microbes played important roles in enhancing the root and plant growth of I. pseudoacorus.

Saline-alkali could decrease root activity, increase proline content, and decrease chlorophyll content in plant cells (Puniran-Hartley et al., 2014). As shown in Table 3, the root activity and Chlorophyll content of I. pseudoacorus in PF and PFM were similar and higher than those in P. Especially the root activity of I. pseudoacorus, the value in PF and PFM was 1.13 and 1.18 mg⋅g–1⋅h–1, respectively, at the end of the operation, significantly (p < 0.05) higher than that in P. The results indicated that fillers and microorganisms could enhance the physiological characteristics of plants, particularly the root activity in the integrated floating bed. Accordingly, the salt tolerance of I. pseudoacorus in PFM was enhanced, and the proline content of I. pseudoacorus in PFM was 0.49 μmol⋅g–1 higher than the other two reactors. Also, the relative conductivity of the leaves in PFM was 11.96%, which is significantly lower than that in P and PF (Table 3). Microorganisms could colonize around the root zone through fillers and provide positive feedback for plant growth by discharging beneficial compounds in the rhizosphere (Ahemad and Kibret, 2014). In addition, salt-tolerance microorganisms could suppress the accumulation of reactive oxygen species and sodium accumulation in plants, and improve salt-tolerance characteristics of plants by stimulating the activities of antioxidant enzymes (Yasmeen et al., 2020). The results indicated that the integrated floating bed could facilitate the salt tolerance and root activity of I. pseudoacorus and increase the contribution of plants for pollutants removal.

The microbial structure was analyzed by 16S rRNA high throughput sequencing technology. The results showed that Acinetobacter, Bdellovibrio, Hydrogenophaga, and Shewanella were mainly enriched in PFM with a relative abundance of 6.8, 6.1, 4.7, and 3.1%, respectively, when compared with the microbial structure in M (Figure 3). According to previous studies, Acinetobacter, Bdellovibrio, and Hydrogenophaga showed the characteristic of salt tolerance and the function of nutrient removal performance in water (Hood et al., 2010; Ji et al., 2016; Zuo et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). Lots of species in Shewanella have been detected in hypersaline environments, and it has demonstrated its tolerance to a wide range of salt concentrations (Fu et al., 2014). In addition, Shewanella plays an important role in marine P transformation through producing a large amount of extracellular polymeric substances and showing a relatively high P removal performance under aerobic conditions (Jiang et al., 2018). Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas have great nitrogen removal ability, and could remove NH4+-N and NO3–-N via heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification, respectively (Huang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). Thus, it was inferred that plants in PFM could enrich more microbes with the function of salt tolerance and pollutant removal performance. Plants improved the salt tolerance of biofilm while strengthening their own growth, and ultimately, promoted the stability of the system and the effective removal of pollutants.

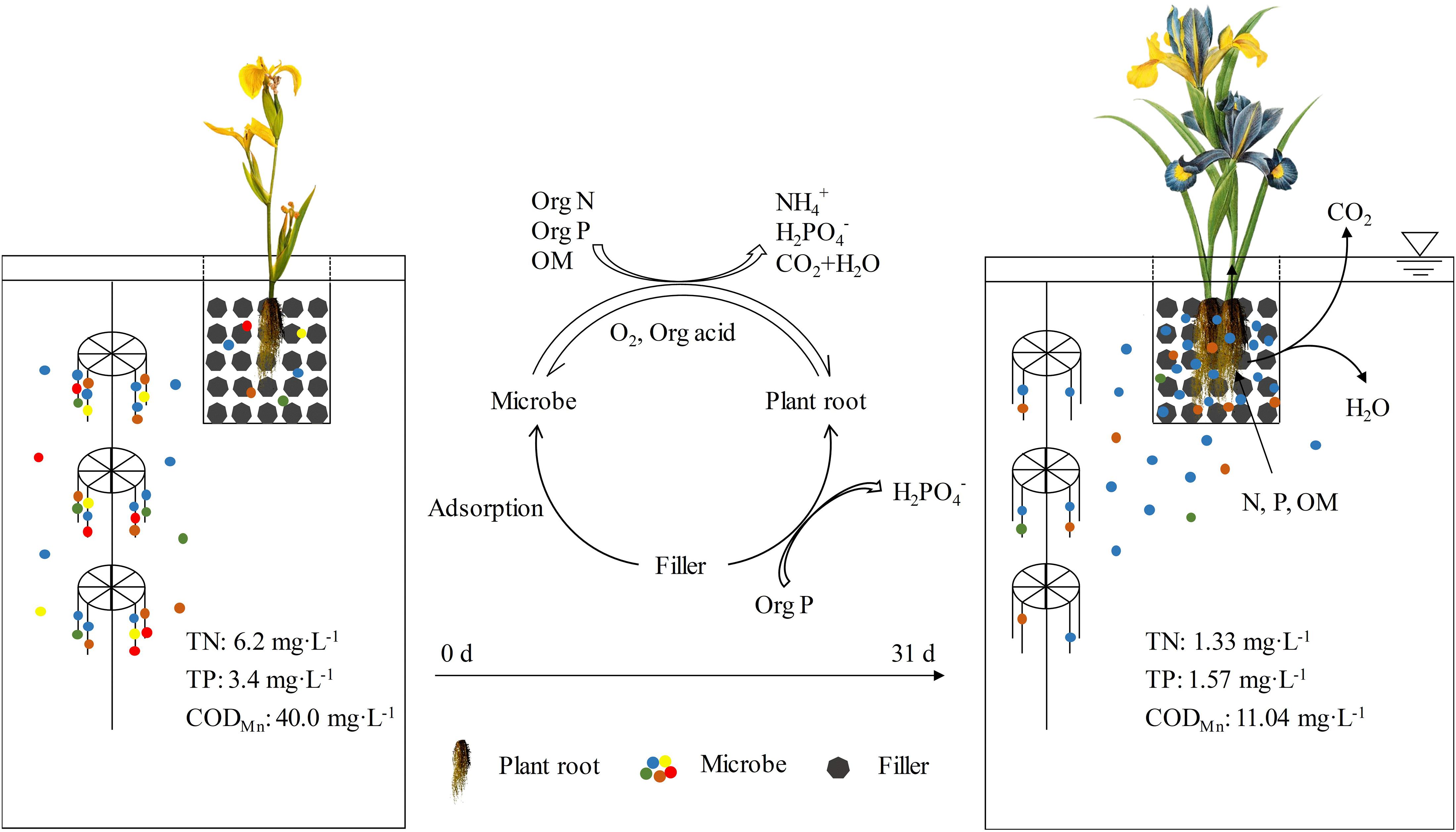

The synergistic action of I. pseudoacorus, filler, and microbe on the purification of brackish water was characterized by the synergistic pollutant removal efficiency (ηS) of the floating bed PFM. As shown in Table 4, the synergistic pollutant removal efficiency of NH4+-N, TN, TP, and CODMn in PFM was 3.9, 16, 1.9, and 4.2%, respectively. In a single ecosystem with only plants, assimilation by plant root and the associated denitrification are the main mechanisms of nitrogen removal. In the microbial system, various biochemical reaction, including nitrification and denitrification, existed in the nitrogen removal process as well (Liu et al., 2016a). Nevertheless, there are some different interactions occurring in an integrated plant and microbe ecosystem. The relative growth rate, root activity, and root proline content of plants in the integrated floating bed PFM were higher than those in P and PF (Tables 2, 3). It was indicated that the addition of microorganisms enhanced the salt tolerance of plant and promoted plant growth. On the one hand, the macromolecules could be degraded into micromolecules by microbes, the plants then directly absorbed and utilized these micromolecules (Figure 4). On the other hand, microorganisms could improve the survival ability of plants by remitting the toxicity of plant pathogens (Lu et al., 2015). Microorganisms can also alleviate water deficiency and increase antioxidant capacity of plants by establishing new ion balance (Kudoyarova et al., 2013).

Figure 4. Mechanism of synergistically purifying eutrophic brackish water by plants, microbes, and fillers. Microorganisms can degrade the macromolecules into micromolecules that can be directly absorbed and utilized by plants. Plant roots and fillers provide carriers for attachment and habitation of the functional bacteria. Plant roots can also secrete a variety of unstable carbon compounds, such as organic acids and amino acids that promote microbial metabolism and form biofilms on the root surface.

Previous studies have shown that the removal mechanisms of pollutants in water mainly include microbial degradation, plant root retention, and filler adsorption, among them, microbial degradation played a major role (Yu et al., 2019). This is consistent with the results of this study (Table 4). The relative abundance of functional bacteria for nitrogen and phosphorus removal increased in PFM according to the results of microbial community analysis (Figure 3), leading to a higher contribution rate of pollutant removal than plants and fillers. In the PFM system, fillers and plant roots provided carriers for attachment and habitation of the functional bacteria (Ning et al., 2014b; Keizer-Vlek et al., 2014) because oxygen secreted by plant roots could form many anaerobic–anoxic–oxic micro areas, which were equivalent to many series–parallel A2/O units. These units could enhance microbial nitrification and denitrification, and indirectly improve the denitrification efficiency (Cao and Zhang, 2014; Li et al., 2015). Furthermore, plant roots can also secrete a variety of unstable carbon compounds, such as organic acids and amino acids that promote microbial metabolism and form biofilms on the root surface (Figure 4; Rocha et al., 2015). As a result, microbial population, quantity and metabolic rate were improved. On the other hand, the metabolic process of microorganisms in the system could be further studied in the aspect of metabonomics, and the metabolic mechanism of the microorganisms would be illustrated more clearly.

A novel integrated floating bed (PFM) with plants (Iris pseudoacorus), fillers (volcanic rocks and zeolites), and microbes achieved excellent NH4+-N, TN, TP, and CODMn removal performance, and most of the pollutants were removed by microbes. In addition, the enrichment of Acinetobacter in PFM enhanced the salt tolerance and nitrogen removal performance of the system. The analysis of the synergistic action of PFM indicated that the plants and fillers could enrich more salt-tolerant microbes for pollutant removal, which in turn promoted the growth and salt-tolerance characteristics of plant. Plants and fillers had synergistic actions with microbes in the process of eutrophic brackish water purification. Finally, the novel integrated floating bed system for high-efficiency pollutants removal performance of eutrophic and brackish water bodies purification was established.

NCBI Sequence Read Archive, and the accession number is PRJNA691644. To browse the data, use SRA Run Selector: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=PRJNA691644.

ML and YC planned the experiments. ML and YW performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. JG and PS contributed to literature collection and data analysis. YC and ZZ participated in critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (ZR2019MD033).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abdelaziz, M. E., Kim, D., Ali, S., Fedoroff, N. V., and Al-Babili, S. (2017). The endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica enhances Arabidopsis thaliana growth and modulates Na+/K+ homeostasis under salt stress conditions. Plant Sci. 263, 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.07.006

Abed, S. N., Almuktar, S. A., and Scholz, M. (2017). Remediation of synthetic greywater in mesocosm—scale floating treatment wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 102, 303–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.01.043

Ahemad, M., and Kibret, M. (2014). Mechanisms and applications of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: current perspective. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 26, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2013.05.001

Bartucca, M. L., Mimmo, T., Cesco, S., and Buono, D. D. (2016). Nitrate removal from polluted water by using a vegetated floating system. Sci. Total Environ. 542, 803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.156

Benzarti, M., Rejeb, K. B., Messedi, D., Mna, A. B., Hessini, K., Ksontini, M., et al. (2014). Effect of high salinity on Atriplex portulacoides: growth, leaf water relations and solute accumulation in relation with osmotic adjustment. S. Afr. J. Bot. 95, 70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2014.08.009

Bhagowati, B., and Ahamad, K. U. (2019). A review on lake eutrophication dynamics and recent developments in lake modeling. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 19, 155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ecohyd.2018.03.002

Cao, W. P., and Zhang, Y. Q. (2014). Removal of nitrogen (N) from hypereutrophic waters by ecological floating beds (EFBs) with various substrates. Ecol. Eng. 62, 148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.10.018

Chang, N. B., Islam, K., Marimon, Z., and Wanielista, M. P. (2012). Assessing biological and chemical signatures related to nutrient removal by floating islands in stormwater mesocosms. Chemosphere 88, 736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.04.030

Fu, X. P., Wang, D. C., Yin, X. L., Du, P. C., and Kan, B. (2014). Time course transcriptome changes in Shewanella algae in response to salt stress. PLoS One 9:e96001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096001

Gacia, E., Bernal, S., Nikolakopoulou, M., Carreras, E., Morgado, L., Ribot, M., et al. (2019). The role of helophyte species on nitrogen and phosphorus retention from wastewater treatment plant effluents. J. Environ. Manage. 252:109585. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109585

Gottschall, N., Boutin, C., Crolla, A., Kinsley, C., and Champagne, P. (2007). The role of plants in the removal of nutrients at a constructed wetland treating agricultural (dairy) wastewater. Ont. Can. Ecol. Eng. 29, 154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2006.06.004

Guo, Y. M., Liu, Y. G., Zeng, G. M., Hu, X. J., Li, X., Huang, D. W., et al. (2014). A restoration-promoting integrated floating bed and its experimental performance in eutrophication remediation. J. Environ. Sci. 26, 1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(13)60500-8

Hood, M. I., Jacobs, A. C., Sayood, K., Dunman, P. M., and Skaar, E. P. (2010). Acinetobacter baumannii increases tolerance to antibiotics in response to monovalent cations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 1029–1041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00963-09

Huang, C., Liu, Q., Li, Z. L., Ma, X. D., Hou, Y. N., Ren, N. Q., et al. (2021). Relationship between functional bacteria in a denitrification desulfurization system under autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic conditions. Water Res. 188:116526. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116526

Huang, L. F., Zhuo, J. F., Guo, W. D., Spencer, R. G. M., Zhang, Z. Y., and Xu, J. (2013). Tracing organic matter removal in polluted coastal waters via floating bed phytoremediation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 71, 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.03.032

Ji, B., Chen, W., Zhu, L., and Yang, K. (2016). Isolation of aluminum-tolerant bacteria capable of nitrogen removal in activated sludge. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 106, 31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.03.051

Jiang, L., Wang, M., Wang, Y. R., Liu, F. J., Qin, M., Zhang, Y. Z., et al. (2018). The condition optimization and mechanism of aerobic phosphorus removal by marine bacterium Shewanella sp. Chem. Eng. J. 345, 611–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.01.097

Karapınar, N. (2009). Application of natural zeolite for phosphorus and ammonium removal from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 170, 1186–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.094

Keizer-Vlek, H. E., Verdonschot, P. F. M., Verdonschot, R. C. M., and Dekkers, D. (2014). The contribution of plant uptake to nutrient removal by floating treatment wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 73, 684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.09.081

Kudoyarova, G. R., Kholodova, V. P., and Veselov, D. S. (2013). Current state of the problem of water relations in plants under water deficit. Russ. J. Plant Physl. 60, 165–175. doi: 10.1134/S1021443713020143

Li, L. Z., He, C. G., Ji, G. D., Wei, Z., and Sheng, L. X. (2015). Nitrogen removal pathways in a tidal flow constructed wetland under flooded time constraints. Ecol. Eng. 81, 266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.04.073

Li, X. N., Song, H. L., and Li, W. (2010). An integrated ecological floating-bed employing plant, freshwater clam and biofilm carrier for purification of eutrophic water. Ecol. Eng. 36, 382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2009.11.004

Li, Z. L., Cheng, R., Chen, F., Lin, X. Q., Yao, X. J., Liang, B., et al. (2021). Selective stress of antibiotics on microbial denitrification: inhibitory effects, dynamics of microbial community structure and function. J. Hazard. Mater. 405:124366. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124366

Liu, J. Z., Wang, F. W., Liu, W., Tang, C. L., Wu, C. X., and Wu, Y. H. (2016a). Nutrient removal by up-scaling a hybrid floating treatment bed (HFTB) using plant and periphyton: from laboratory tank to polluted river. Bioresource Technol. 207, 142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.02.011

Lu, H. L., Ku, C. R., and Chang, Y. H. (2015). Water quality improvement with artificial floating islands. Ecol. Eng. 74, 371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.11.013

Ma, D. Y., Chen, S., Lu, J., and Liao, H. X. (2019). Study of the effect of periphyton nutrient removal on eutrophic lake water quality. Ecol. Eng. 130, 122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.02.014

Ning, D. L., Huang, Y., Pan, R. S., Wang, F. Y., and Wang, H. (2014b). Effect of eco-remediation using planted floating bed system on nutrients and heavy metals in urban river water and sediment: a field study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 485, 596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.03.103

Olguín, E. J., Sánchez-Galván, G., Melo, F. J., Hernández, V. J., and González-Portela, R. E. (2017). Long-term assessment at field scale of floating treatment wetlands for improvement of water quality and provision of ecosystem services in a eutrophic urban pond. Sci. Total Environ. 584, 561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.072

Puniran-Hartley, N., Hartley, J., Shabala, L., and Shabala, S. (2014). Salinity-induced accumulation of organic osmolytes in barley and wheat leaves correlates with increased oxidative stress tolerance: in planta evidence for cross-tolerance. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 83, 32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.07.005

Rocha, A. C. S., Almeida, C. M. R., Basto, M. C. P., and Vasconcelos, M. T. S. D. (2015). Influence of season and salinity on the exudation of aliphatic low molecular weight organic acids (ALMWOAs) by Phragmites australis and Halimione portulacoides roots. J. Sea Res. 95, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2014.07.001

Saeed, T., Paul, B., Afrin, R., Al-Muyeed, A., and Sun, G. Z. (2016). Floating constructed wetland for the treatment of polluted river water: a pilot scale study on seasonal variation and shock load. Chem. Eng. J. 287, 62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.10.118

State Environmental Protection Administration of China, and Editorial Board of Monitoring and Analytical Method of Water and Wastewater (2002). Monitoring and Analytical Method of Water and Wastewater. Beijing: China Environmental Science Press. (in Chinese).

Sun, S. S., Liu, J., Zhang, M. P., and He, S. B. (2019). Simultaneous improving nitrogen removal and decreasing greenhouse gas emission with biofilm carriers addition in ecological floating bed. Bioresource Technol. 292:121944. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121944

Urakawa, H., Dettmar, D. L., and Thomas, S. (2017). The uniqueness and biogeochemical cycling of plant root microbial communities in a floating treatment wetland. Ecol. Eng. 108, 573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.06.066

Wang, C. Y., and Sample, D. J. (2014). Assessment of the nutrient removal effectiveness of floating treatment wetlands applied to urban retention ponds. J. Environ. Manage. 137, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.02.008

Wang, G. F., Wang, X. J., Wu, L., and Li, X. N. (2012). Contribution and purification mechanism of bio-components to pollutants removal in an integrated ecological floating bed. J. Civil Arch. Environ. Eng. 34, 136–141. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4764.2012.04.022 (in Chinese with English abstract),

Wang, S. B., and Peng, Y. L. (2010). Natural zeolites as effective adsorbents in water and wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 156, 11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.10.029

Wang, W. H., Wang, Y., Sun, L. Q., Zheng, Y. C., and Zhao, J. C. (2020a). Research and application status of ecological floating bed in eutrophic landscape water restoration. Sci. Total Environ. 704:135434. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135434

Wang, W. H., Wang, Y., Wei, H. S., Wang, L. P., and Peng, J. (2020b). Stability and purification efficiency of composite ecological floating bed with suspended inorganic functional filler in a field study. J. Water Process Eng. 37:101482. doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101482

Wang, X. G., Yang, T. Y., Lin, B., and Tang, Y. B. (2017). Effects of salinity on the performance, microbial community, and functional proteins in an aerobic granular sludge system. Chemosphere 184, 1241–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.047

Wang, X. Y., Zhu, H., Yan, B. X., Shutes, B., Bañuelos, G., and Wen, H. Y. (2020c). Bioaugmented constructed wetlands for denitrification of saline wastewater: a boost for both microorganisms and plants. Environ. Int. 138:105628. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105628

Wang, Y. E., Li, J., Zhai, S. Y., Wei, Z. Y., and Feng, J. J. (2015). Enhanced phosphorus removal by microbial-collaborating sponge iron. Water Sci. Technol. 72, 1257–1265. doi: 10.2166/wst.2015.323

Wu, Q., Hu, Y., Li, S. Q., Peng, S., and Zhao, H. B. (2016). Microbial mechanisms of using enhanced ecological floating beds for eutrophic water improvement. Bioresource Technol. 211, 451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.03.113

Yasmeen, T., Ahmad, A., Arif, M. S., Mubin, M., Rehman, K., Shahzad, S. M., et al. (2020). Biofilm forming rhizobacteria enhance growth and salt tolerance in sunflower plants by stimulating antioxidant enzymes activity. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 156, 242–256. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.09.016

Yousefi, Z., and Mohseni-Bandpei, A. (2010). Nitrogen and phosphorus removal from wastewater by subsurface wetlands planted with Iris pseudacorus. Ecol. Eng. 36, 777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2010.02.002

Yu, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, C., Xue, Y. J., Shimizu, H., Wang, C. H., et al. (2019). Ecological responses of three emergent aquatic plants to eutrophic water in Shanghai. P. R. China. Ecol. Eng. 136, 134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.06.008

Zhao, W. Y., Wang, Q. S., Wu, L. B., Zhang, B., and Wang, X. Q. (2005). Qualitative analysis and quantitative simulation on Yin-Huang water salinization mechanism in Bei-Da-Gang Reservoir. J. Environ. Sci. 17, 853–856. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1001-0742.2005.05.031

Keywords: integrated floating bed, brackish water, synergistic action, microorganism, Iris pseudoacorus

Citation: Liu M, Chen Y, Wu Y, Guo J, Sun P and Zhang Z (2021) Synergistic Action of Plants and Microorganism in Integrated Floating Bed on Eutrophic Brackish Water Purification in Coastal Estuary Areas. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:619087. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.619087

Received: 19 October 2020; Accepted: 01 March 2021;

Published: 08 April 2021.

Edited by:

Zhiling Li, Harbin Institute of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Hong-Cheng Wang, Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Liu, Chen, Wu, Guo, Sun and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youyuan Chen, eW91eXVhbkBvdWMuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.