94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 11 February 2021

Sec. Marine Biogeochemistry

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.617241

The burial of organic carbon (OC) in the river-dominated margin plays an important role in global carbon cycle, but its accumulation mechanism is not well understood. Here, we examined the concentration and distribution of water-extractable organic matter (WEOM) and base-extractable organic matter (BEOM) in surface sediments from the lower Yangtze River, estuary, and the East China Sea. Chemical characteristics of the WEOM and BEOM were described by multiple ultraviolet-visible and fluorescence spectral indicators. Concentrations of both WEOM and BEOM showed significant correlations with sediment grain size, suggesting that mineral surface area is a key factor for OC loadings on sediments. Three components (C1, C2, and C3) extracted from fluorescence excitation emission matrices-parallel factor analysis were assigned as terrigenous humic-like substance, mixed terrigenous/aquatic humic-like substance, and microbial protein-like substance, respectively. From the lower Yangtze River to the East China Sea, the C1%, specific UV absorbance at 254 nm (SUVA254), and humification index (HIX) of the WEOM decreased, while the C3%, fluorescence index (FI), and biological index (BIX) of the WEOM increased. This suggested the loss of terrigenous OC and addition of microbial OC in the WEOM. While for BEOM, the overall increase of C1% and HIX and the decrease of C3% and FI suggested selective removal of microbial OC and preferential preservation of terrigenous OC. Our study demonstrates complex behaviors of sediment organic matter (OM) during the land-to-sea transport that is largely controlled by the binding strength of OM–sediment association, and that the formation of BEOM is an important pathway for accumulation of terrigenous OM in the river-dominated margin.

Each year, rivers discharge approximately 0.4 × 1015 g of particulate organic carbon and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) to the sea (Hedges et al., 1997), representing a key conduit linking carbon pools of continent to ocean. During the transport from land to sea, dissolved organic matter (DOM) and particulate organic matter (POM) were partly degraded and transformed from each other (Bianchi et al., 2002; He et al., 2016). The physical and chemical protection by sediment matrix is an important mechanism for the stabilization of organic carbon (OC) in environments (Mayer, 1994; Kleber et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2011; Lalonde et al., 2012). The sequential extraction of sediment organic matter (OM) using water and base solutions provides an opportunity for separation of water-extractable organic matter (WEOM) and base-extractable organic matter (BEOM) that generally represent DOM and POM in sediments, respectively (Osburn et al., 2012). Compared to BEOM, WEOM is weakly associated with sediments and easily released into ambient waters that was then photo- and microbially degraded. Thus, the investigation of concentration, composition, and transformation of WEOM and BEOM could shed light on the degradation and preservation of OM in aquatic environments.

DOM in environments is a heterogeneous mixture of compounds that comprise up to >200,000 different molecular formulae (Koch et al., 2005). A variety of analytical techniques have been used for chemical characterization of DOM. Relative to mass spectroscopy, ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis) and fluorescence spectroscopy have advantages of high sensitivity, fast analysis, and being solvent-free for analyzing chromophoric and fluorescent DOM that is an optical active component of DOM (Chen and Hur, 2015). By examining distributions of sediment OM between dissolved and particulate phases in Korean streams/rivers using UV-Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy, He et al. (2016) found that OM molecules of the BEOM had higher aromatic contents and larger size compared with those of the WEOM. Thus, humic-like OM was selectively preserved. However, the study for the Neuse River Estuary (North Carolina) revealed that water-soluble DOM was composed of more high-molecular-weight and more aromatic components compared to POM (BEOM) (Osburn et al., 2012). These differences were attributed to different internal and external factors between two settings, such as total organic carbon (TOC), metal concentration, land use, and vegetation cover (He et al., 2016).

The Yangtze River is the fourth largest river in terms of water discharge (Yang et al., 2007) and the fifth largest river in terms of OC flux (Dagg et al., 2004; Raymond and Spencer, 2015). The intense human activities, such as the Three Gorges Dam and the South-to-North Water Transfer Project, have profoundly modified this river system. For example, the sediment load of the Yangtze River is 400 Mt year–1 pre-Three Gorges Dam and 100 Mt year–1 post-Three Gorges Dam (Yang et al., 2007), while the seasonal hypoxic zone off the Yangtze River Estuary has increased to over 10,000 km2 in summer and fall (Wei et al., 2015). Several studies have investigated DOM in water column (e.g., Guo et al., 2014; Bao et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2016) or pore water (Wang et al., 2013) in the Yangtze River-dominated margin. Their results showed spatial and temporal variations in concentrations and composition of DOM, presumably related to the Asian monsoon, water salinity, hydrology, and anthropogenic disturbance, among others. However, to the best of our knowledge, the comparison between WEOM and BEOM has never been reported, hampering our understanding of OC transport and accumulation in the Yangtze River-dominated margin.

In this study, we examined contents and optical characteristics of the WEOM and BEOM as well as bulk properties of surface sediments that were collected along the transect of lower Yangtze River to the East China Sea. Our aims are to: (1) determine spatial distributions in concentration and composition of WEOM and BEOM and (2) assess the relative importance of OC–sediment association for the transport and accumulation of WEOM and BEOM.

The Yangtze River is the largest river in China with the total length of 6,300 km and drainage area of 1.8 million km2. It originates in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (western China) at the altitude of >5,000 m, flows eastward, and finally drains into the East China Sea. Because of enormous amounts of water discharge and sediment load, the Yangtze River has profound influences on the geomorphology and biogeochemical cycle of the East China Sea and western Pacific (Liu et al., 2007). The climate of lower Yangtze River is controlled by the East Asian Monsoon, characterized by humid, warm summer and cold, dry winter. In July 2019, surface sediments were collected by a grab or box sampler at 12 sampling sites (R1–R6 and S1–S6) along the transect of the lower Yangtze River to the East China Sea (Figure 1). The water salinity was in situ measured by using a conductivity–temperature–depth (CTD) sensor (SBE 911plus, United States). The surface sediments (0–3 cm) were immediately stored at –20°C until transported to the laboratory at Shanghai Ocean University. The samples were then lyophilized at –40°C prior to analysis.

All chemicals used in our study are of analytical reagent grade or higher. The concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) is 36–38%, containing less than 0.0001% metals, whereas concentrated hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is 30%, containing less than 0.0002% metals. The purities of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium hexametaphosphate [(NaPO3)6] are >96 and >99.7%, respectively. Ultrapure water (18 mΩ cm–1) is provided by using MilliQ Elix Essential 10.

For analyses of TOC content and stable isotope of OC, about 1.5 g of dried sediments was reacted with excess diluted hydrochloric acid (1.0 M) for 72 h. The decarbonated sediments were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 15 min. After removal of the supernatant, the residues were washed with ultrapure water until pH is neutral. The decarbonated sediments were freeze-dried and homogenized with an agate mortar and pestle. Approximate 35–40 mg of decarbonated sediments were weighed and analyzed using a DELTA Plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany) and a Vario EL cube elemental analyzer (Elementar, Germany). All isotopic data were reported in δ notation. Acetanilide was used as both reference standard for carbon contents (71.09%) and intra-lab standard for δ13C (–29.53‰). The average standard deviation as determined by replicate analyses of acetylaniline was ± 0.09‰ for δ13C.

For particle size analysis, 0.2–1.5 g of sediments was reacted with H2O2 (10%) to remove OM and then by diluted hydrochloric acid (1.0 M) to remove carbonates. After that, (NaPO3)6 was added to reduce the gathered material in the dispersion system. The grain size was measured by a Mastersizer 2000 Laser Particle Size Analyzer. Each sample was measured three times, showing an averaged standard deviation of ±0.7 μm. The scan range was 0.02–2,000 μm, and the grains were categorized into three fractions: sand (62.5–2,000 μm), silt (3.9–62.5 μm), and clay (<3.9 μm). Since there was a strong positive correlation between the mean grain size and median grain size (r = 0.99, p < 0.01), only the data of median grain size were reported in this study.

About 10 g of freeze-dried sediments were mixed with 100 ml ultrapure water in centrifuge bottles. The samples were shaken for 24 h (300 rpm) and then centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatants (WEOM) were filtered through 0.7-μm GF/F pore-size filters (Thermo, F2700-18). The residues were freeze-dried and mixed with 100 ml of 0.1 M NaOH, which then were shaken for 24 h (300 rpm). This extract (BEOM) was centrifuged and filtered using the same protocol for WEOM. The filtrates were adjusted to neutral by addition of concentrated hydrochloric acid. Both WEOM and BEOM were kept in High density polyethylene (HDPE) bottles at 4°C.

The DOC concentration of each sample was determined by 3–5 injections on a Shimadzu TOC-VCPH analyzer using high-temperature combustion, and the coefficient of variance across measurements was <2%. In order to compare extractable OC among different sediments, the DOC concentrations of WEOM and BEOM were normalized to OC per dry weight sediment (dws) following the equation: , where DOC was determined by TOC analyzer, V is total volume of BEOM or WEOM, and dws is dry weight sediments extracted. The blank experiments showed insignificant OC contaminant (<10% of WEOM or BEOM from samples).

Before UV-Vis measurement, WEOM and BEOM were diluted with ultrapure water until the absorbance is around 0.1–0.2 at 254 nm. The UV-Vis absorbance was measured on a Shimadzu dual-beam UV-2600 spectrophotometer in 1-nm increment between 200 and 800 nm at ambient temperature of 23°C. Specific UV absorbance at 254 nm (SUVA254; L mg C–1 m–1) that was derived by dividing the decadic absorption coefficient (a; m–1) at 254 nm by the DOC concentration (mg C L–1) was calculated for estimating the dissolved aromatic carbon content in aquatic systems (Weishaar et al., 2003).

Fluorescence excitation emission matrices (EEMs) were collected over an excitation (ex) and emission (em) wavelength of 240–450 nm and 250–550 nm, in 5- and 1-nm increments, respectively, using Hitachi F-7000 fluorescence spectrophotometer. The obtained three-dimensional fluorescence spectra (3D-EEMs) were corrected by deducted internal filtration through the absorption of spectrum with the same sample in the band and the blank value of ultrapure water measurement before the sample measurement, which was then performed using Raman normalization. Parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC) was carried out to obtain different components of DOM (Matlab2018b Program; Murphy et al., 2013), all of which were in line with the reported component wavelength range (Fellman et al., 2010). Fluorescence index (FI), an indicator for assessing the relative abundance of terrigenous derived DOM (FI < 1.21) and microbial/algal DOM (FI > 1.55) (McKnight et al., 2001; Cory et al., 2010), is determined as the ratio of emission intensity at 470 and 520 nm with 370-nm excitation. The biological index (BIX), calculated as a ratio of the fluorescence intensity at an emission of 380 nm to that at 430-nm emission at an excitation of 310 nm, was used to indicate the recent autochthonous and biological contribution (Huguet et al., 2009). The humification index (HIX) represents the degree of DOM humification, which is a ratio of the areas under the emission spectra over 435–480 nm to that over 300–345 nm at excitation 255 nm (Zsolnay et al., 1999).

The program package Origin2018 was used for the statistical analyses. The Pearson correlation and principal component analysis were performed based on the data of bulk geochemical properties (e.g., mineral grain size and δ13C), optical parameters, and DOC concentrations. The significant level was set at p < 0.05.

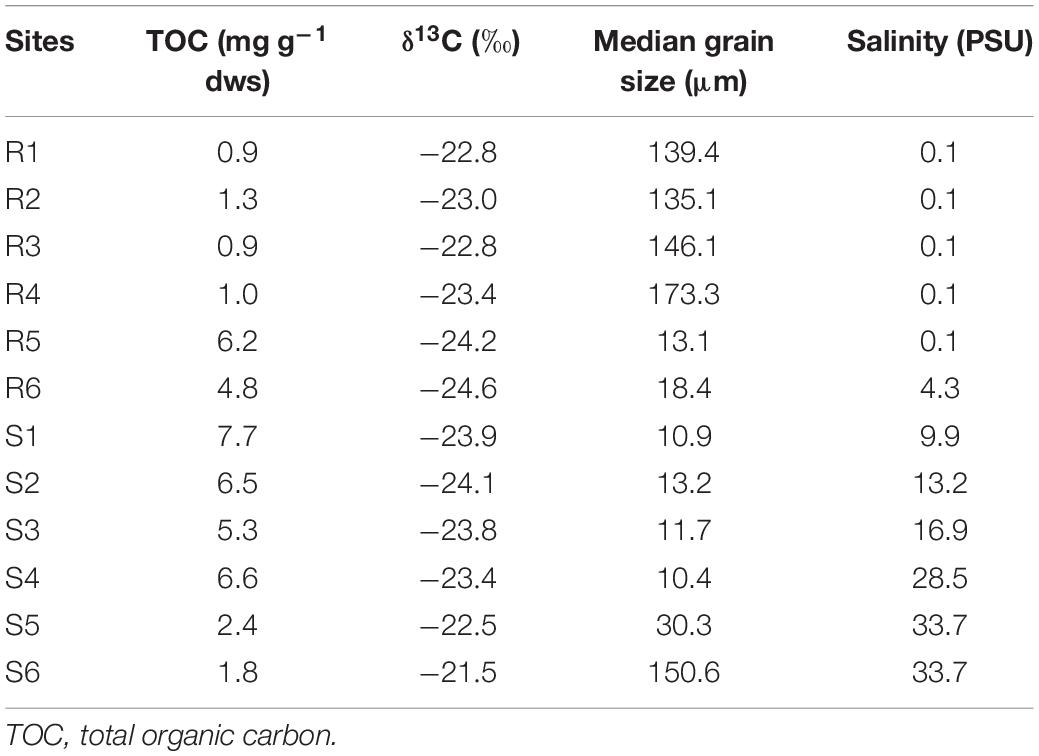

From the lower Yangtze River to East China Sea, the water salinity varied between 0.1 and 33.7 PSU, whereas the TOC content, δ13C, and median grain size of sediments fell in a range of 0.9–7.7 mg g–1 dws, –24.6‰ to –21.5‰, and 10.4–173.3 μm, respectively (Table 1). Such spatial heterogeneity is a common phenomenon in the river-dominated margins due to variable land–sea interaction, human disturbance, and climate change (Bianchi et al., 2002; Goñi et al., 2003; Jia and Peng, 2003; Wu et al., 2014). Salinity is a conservative indicator for the mixing of freshwater and seawater (Hur et al., 1999), whereas the δ13C is an indicator for OM source that marine plankton, riverine algae, and terrigenous C3 plants generally have δ13C values of –22‰ to –19‰, –40‰ to –30‰, and –32‰ to –25‰, respectively (Meyers, 1997). In the lower Yangtze River mainstream, –24.1‰ was designed as an end-member value of terrigenous OC based on isotopic compositions of POM (Xu et al., 2011). The mineral surface area is a pivotal factor for the adsorption of OM on minerals that fine particles having a larger surface area can absorb more OM compared with coarse particles (Mayer, 1994). Therefore, the spatial change in water salinity, TOC content, δ13C and median grain size of surface sediments in our study area reflected differences in seawater influence, OC loading and sources, as well as hydrodynamic sorting, respectively.

Table 1. Bulk characteristics of surface sediments and overlying surface waters in the Yangtze River-dominated margin.

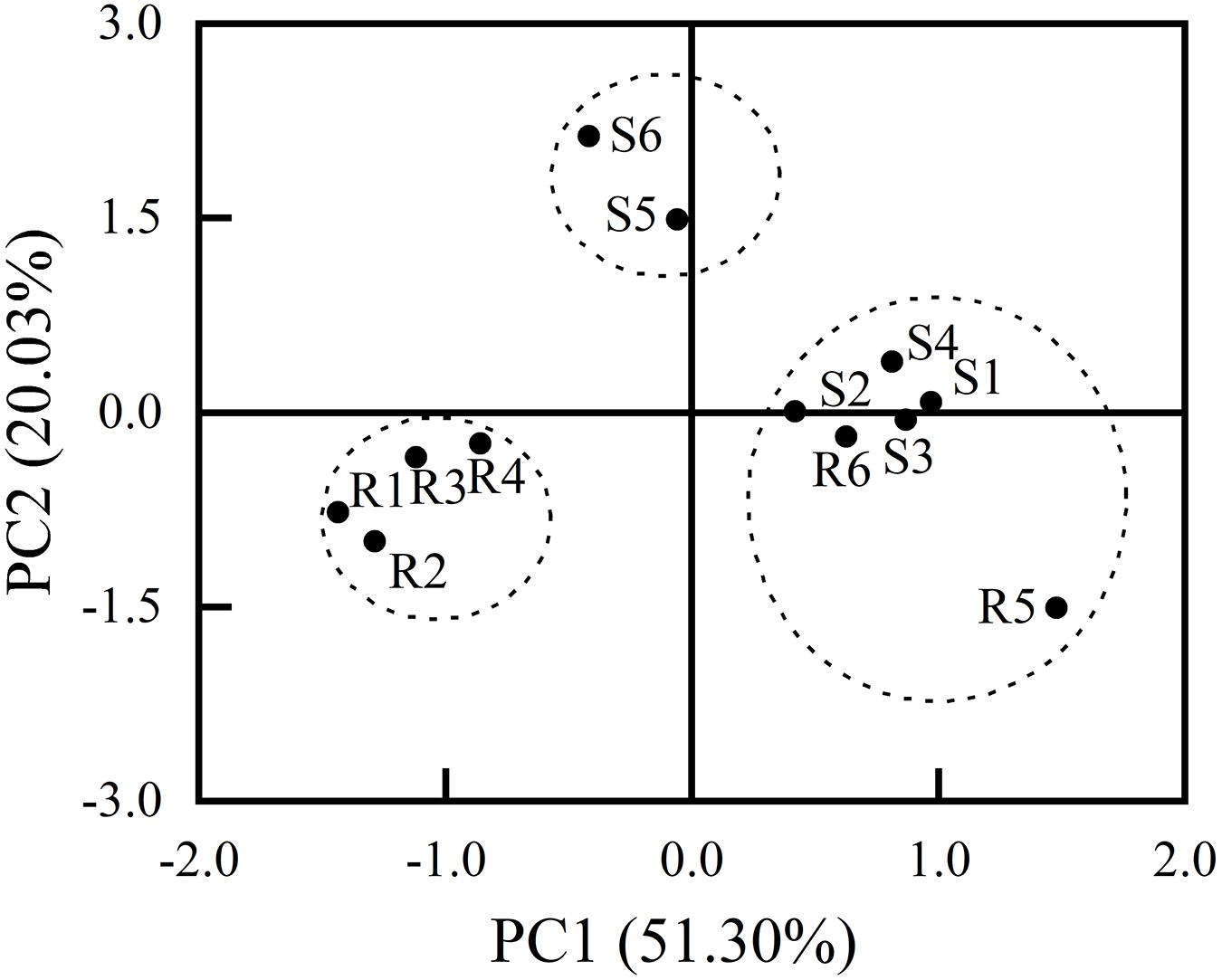

The principal component analysis based on the bulk parameters (e.g., median grain size, water salinity, δ13C, TOC) divided the samples into three groups (Figure 2). Group 1 included samples from sites R1 to R4 in the lower Yangtze River, characterized by the lowest salinity (0.1 PSU) and largest median grain size (135.1–173.3 μm) (Table 1). These characteristics were attributed to strong hydrodynamic sorting in summer when the monsoon precipitation is high (Ding, 1992). Under the high river discharge, coarse particles were preferentially deposited, resulting in the depletion of OC contents (0.9–1.3 mg g–1 dws). Intermediate δ13C values (–23.4‰ to –22.8‰) and low salinity suggested mixed contributions of OC from indigenous C3 plants and exotic C4 plants such as Spartina alterniflora that was introduced to the Yangtze River Estuary in the 1990s (Li et al., 2009). In addition, given that the lower Yangtze River is close to Shanghai, a megacity with over 23 million inhabitants (Figure 1), the anthropogenic input could be another source to the sedimentary OC that was reflected by the enrichment of protein-like, biolabile substance in the DOM of water columns (Guo et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Separation of sediment samples based on principal component analysis (PC1 and PC2) of bulk geochemical parameters [total organic carbon (TOC), δ13C, median grain size, and water salinity].

Group 2 included the samples from sites R5 to S4 in the estuary. These samples were characterized by the smallest median grain size (10.4–18.1 μm), the highest TOC contents (4.8–6.6 mg g–1 dws), and the lowest δ13C (–24.6‰ to –23.2‰) (Table 1). Correspondingly, the salinity dramatically increased from 0.1 to 28.5 PSU. In the Yangtze estuary, the water salinity displayed considerable intra-tide variability (>10 PSU) with the higher level during the flood tides and the lower level during the ebb tides (Gao et al., 2009). Thus, the extremely low salinity at site R5 was likely a snapshot for the sampling time (ebb tide) and could not reflect a long-term average. Nevertheless, the most negative δ13C values of the estuarine sediments suggested an enrichment of terrigenous C3 plant-derived OC that was associated with fine particles.

The samples in Group 3 were from two sites (S5 and S6) in the East China Sea (Figure 2). They had the highest δ13C values (–22.5‰ and –21.5‰) and intermediate levels of median grain size (30.3 and 150.6 μm) and TOC content (2.4 and 1.8 mg g–1 dws) (Table 1). Their water salinity was the highest (33.7 PSU), but still lower than that of open ocean. These results suggested the mixture of terrigenous and marine OC in bulk sedimentary OC. The increase of δ13C by 1‰ from S5 to S6 expectedly reflected a decrease in terrigenous OC seaward.

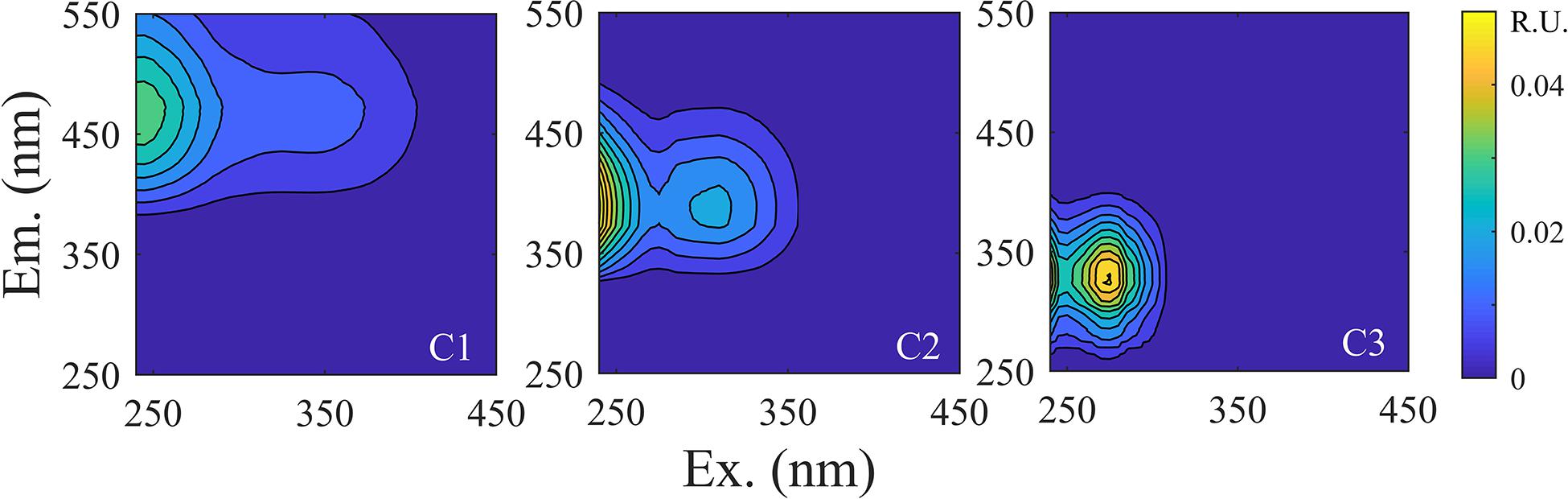

Three components were extracted from the fluorescence EEM-PARAFAC (Figure 3). They were identified by comparison of the maximum excitation/emission wavelengths with literature (Stedmon and Markager, 2003, 2005; Murphy et al., 2006; Fellman et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2016). The C1 peaking at Ex/Em wavelength of 245 (340) nm/472 nm represented terrigenous UVC humic-like substance with high molecular weight and aromaticity. The C2 peaking at Ex/Em wavelength of 310 nm/389 nm was assigned as UVA humic-like substance with relatively low molecular weight that could be ubiquitous in terrigenous and marine settings. The C3 peaking at Ex/Em wavelength of 275 nm/324 nm was typically a protein-like (tryptophan- or tyrosine-like) substance (e.g., amino acids and degraded peptides) that was mainly produced by algae/bacteria.

Figure 3. Typical three components (C1, C2, and C3) determined in the water-extractable organic matter (WEOM) and base-extractable organic matter (BEOM) by the parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC) of excitation emission matrices (EEMs).

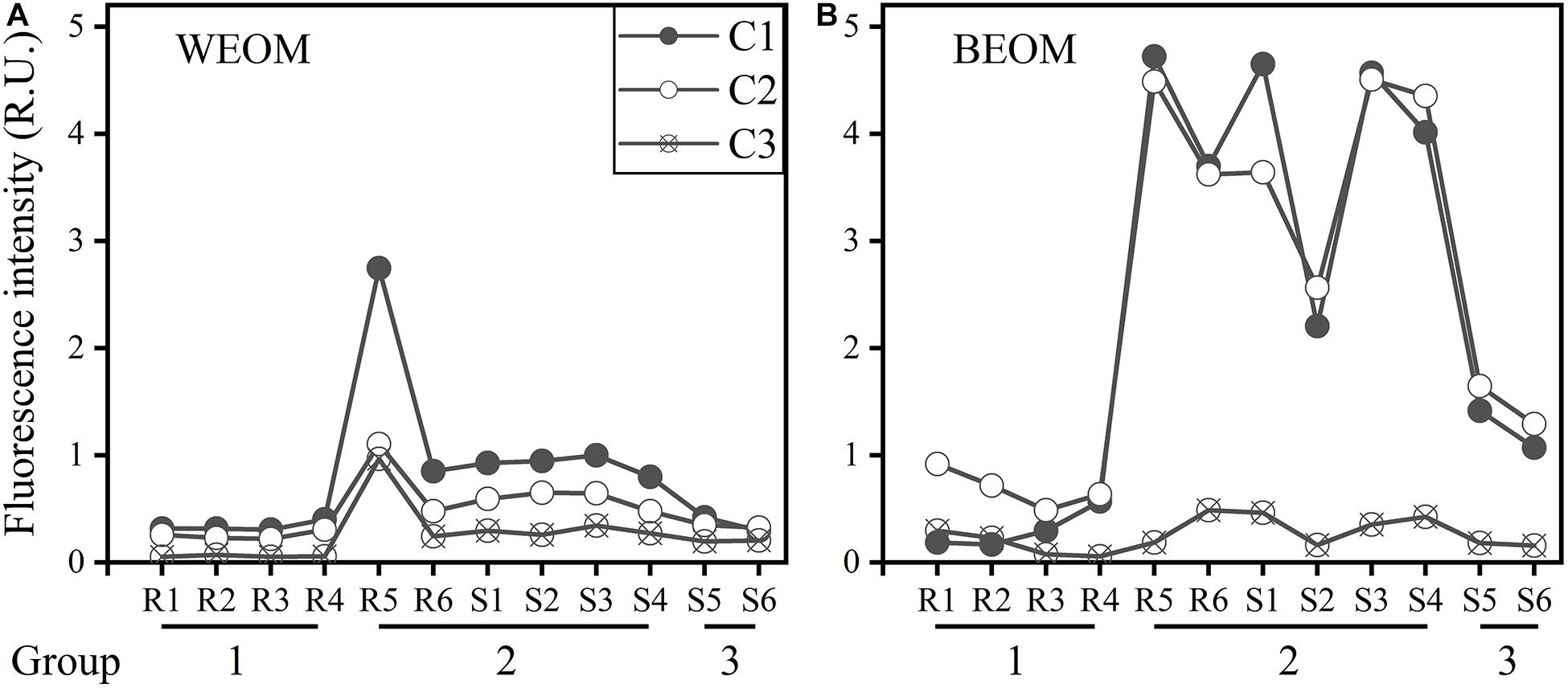

For the WEOM, the intensities of C1 (0.3–2.75 R.U.), C2 (0.22–1.11 R.U.), and C3 (0.05–0.97 R.U.) strongly correlated each other (r > 0.9, p < 0.01). They remained at low levels in the lower Yangtze River (Group 1: R1–R4). After dramatically increasing at site R5, the intensities of C1, C2, and C3 substantially decreased, but they were still higher than that of Group 1. For Group 3 (S5 and S6), the C1 and C2 had similar intensity with that in Group 1, while its C3 intensity was much higher than that of Group 1 (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Variability in fluorescence intensities of C1, C2, and C3 from the lower Yangtze River to the East China Sea in the water-extractable organic matter (WEOM) (A) and the base-extractable organic matter (BEOM) (B).

Compared to the WEOM, the BEOM showed larger amplitude variability for C1 (0.17–4.7 R.U.) and C2 (0.49–4.5 R.U.) and smaller amplitude variability for C3 (0.06–0.49 R.U.) (Table 2). Similar to the WEOM, positive correlations were observed among C1, C2, and C3 in the BEOM (r > 0.65, p < 0.02). However, their spatial distributions showed some contrasting patterns. For the C1 and C2 intensity, the WEOM showed a sharp peak at site R5, whereas the BEOM showed a broad peak from sites R5 to S4 (Figures 4A,B). This difference suggested that terrigenous OC (C1 and partly C2) that strongly bound to sediment minerals could be more efficiently dispersed seaward and buried in marine sediments.

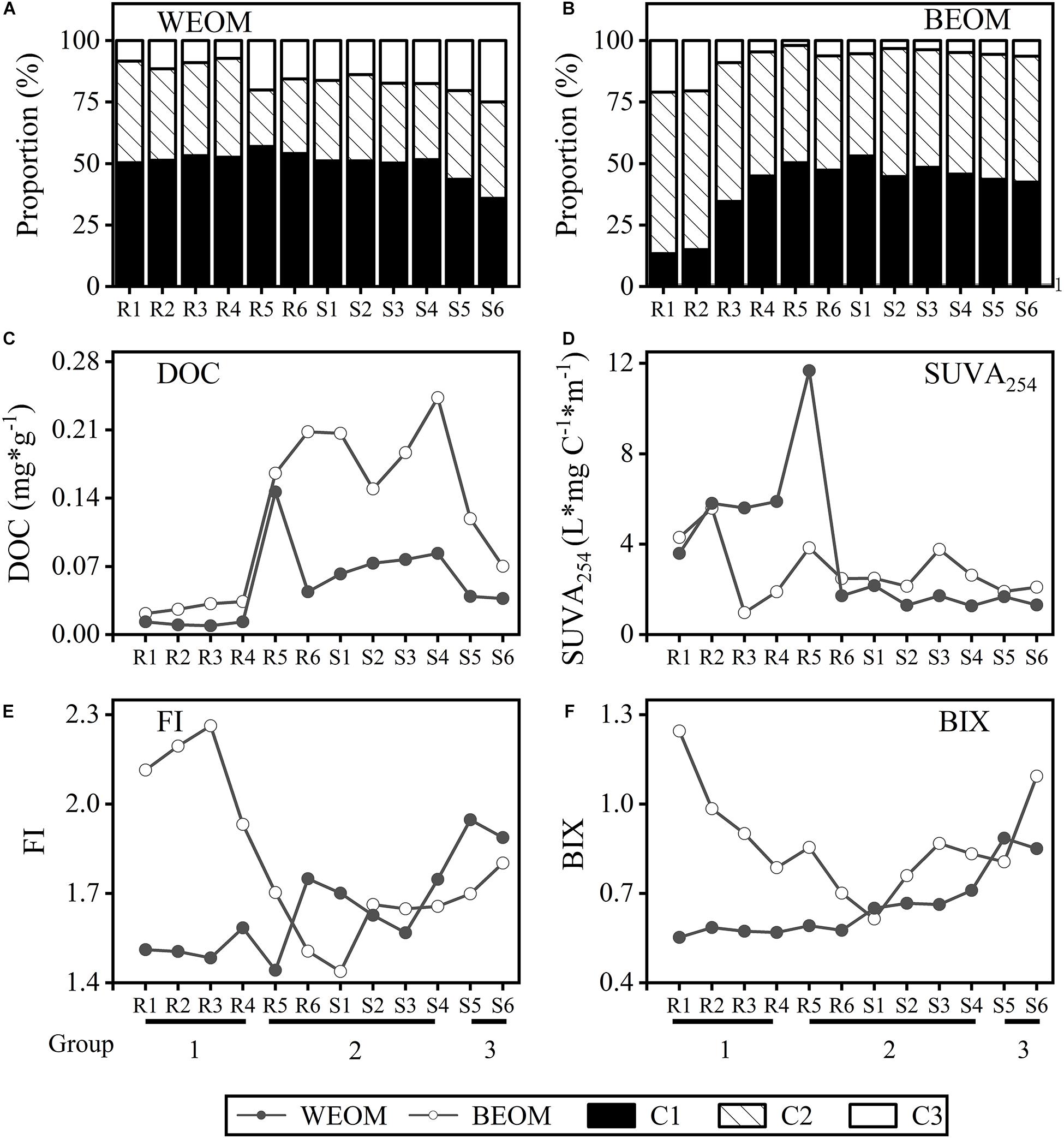

The proportions of C1 (35.8%–57.0%), C2 (23.0%–41.3%), and C3 (7.2%–25.0%) did not show a significant correlation between any two components of the WEOM (Table 3). From the lower Yangtze River to East China Sea, the C1% gradually increased from R1 to R5 but substantially decreased after out of the river mouth (Figure 5A), suggesting significant marine OC inputs and/or degradation of terrestrial WEOM. The C2% was higher in the river (R1–R4) and marine (S5, S6) sediments compared to the estuarine sediments (R5–S4) (Figure 5A). Such pattern suggested a mixed terrigenous/marine OC contribution to the C2. Overall, a seaward increasing trend was observed for the C3%, reflecting an enhanced contribution from aquatic (particularly marine) OC. These source assignments are consistent with the previous studies for the C1, C2, and C3 in the Yangtze River-dominated margin (Jiang et al., 2016).

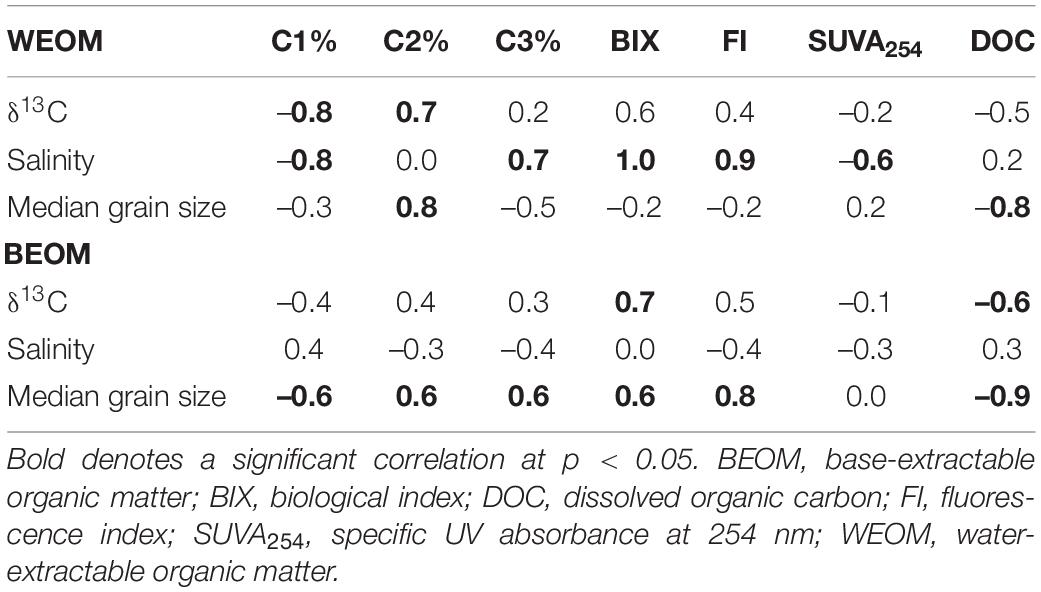

Table 3. Pearson correlations between optical indicators and bulk characteristics of the WEOM and BEOM.

Figure 5. Spatial distributions of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) contents and optical indicators in the water-extractable organic matter (WEOM) and base-extractable organic matter (BEOM). (A) Proportions of C1, C2 and C3 in WEOM; (B) proportions of C1, C2 and C3 in BEOM; (C) dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentration; (D) SUVA254; (E) FI; and (F) BIX.

However, the spatial distribution of C1%, C2%, and C3% was different between the BEOM and WEOM (Figures 5A,B). The percentages of C1, C2, and C3 in the BEOM varied from 13.3 to 53.1%, 41.6 to 65.7%, and 2.0 to 21.0%, respectively. The C1% negatively correlated with the C2% and C3% (r = –0.97, p < 0.01), whereas the C2% and C3% positively correlated each other (r = 0.88, p < 0.01) (Table 3). Thus, the C1 had different OC sources or different environmental behaviors from the C2 and C3 in the BEOM. The C1% increased substantially from sites R1 to R5 and remained at a high level from sites R6 to S6 (Figure 4B). The lack of a declining trend seaward is unexpected, since the C1 was presumably derived from terrigenous OC (Fellman et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2016). This could be explained by different environmental behaviors between the BEOM and WEOM. Being strongly associated with fine particles, terrigenous OC of the BEOM was retained within minerals and thus efficiently transported from the land to sea. In contrast, terrigenous OC in the WEOM, only weakly associated with sediment minerals, was released from sediment matrix and replaced by marine OM during river to sea transport. Consequently, the fractional abundance of the C1 decreased in the WEOM but remained at relatively constant levels in the BEOM during the river to sea transport. The BEOM had much higher DOC concentrations in the Yangtze River Estuary and East China Sea (R6–S6) compared to the WEOM (Figure 5C), also suggesting significant contributions of allochthonous terrigenous OC to the BEOM pool.

The C3% of the BEOM was substantially lower in the estuarine and coastal sediments, whereas the C2% of the BEOM was relatively constant along the river to sea transect (Figure 4B). This difference suggested that it was more difficult for protein-like substances to form strong OM–sediment associations compared with humic-like substances (C1 and partial C2). This difference may explain why marine OM is more labile than terrigenous OM in marine settings (Burdige, 2007).

The DOC, SUVA254, FI, HIX, and BIX of the WEOM and BEOM were shown in Table 2. The DOC concentrations of the WEOM and BEOM ranged from 0.01 to 0.15 mg OC g–1 dws and 0.02 to 0.24 mg∗g–1 dws, respectively, both presenting negative correlations with median grain size (r = –0.77 and –0.90; p < 0.05). Thus, similar to bulk sedimentary OC, the OC loadings of the WEOM and BEOM were also controlled by mineral grain size that fine particles with larger surface areas have a higher binding capability to OC compared to that of coarse particles (Mayer, 1994).

Unlike the abundance that was controlled by mineral grain size, the compositions of the WEOM and BEOM were affected by different factors. In the WEOM, BIX, FI, SUVA254, C1%, and C3% showed significant correlations with salinity but not with mineral grain size or δ13C (Table 3). This was likely due to the weak association between the WEOM and sediments, leading to the rapid desorption of the WEOM from mineral matrix. As a result, the compositions of the WEOM in surface sediments more represented autochthonous products that were related to local conditions (such as water salinity). While for the BEOM, all BIX, FI, C1%, C2%, and C3% significantly correlated with mineral grain size rather than salinity (Table 3). Thus, the compositions of the BEOM more reflected original signatures when OM was bounded to minerals that was controlled by intrinsic characteristics of sediments (e.g., mineral grain size). In addition, terrigenous component (C1) showed a strong correlation with fine-textured sediments; it again reflected an importance of binding strength between the BEOM and sediment matrix that contributed to the stabilization of terrigenous OM during the river to sea transport. These differences suggested that the binding strength of OM–sediment is a key factor for delivery and accumulation of OC in the river-dominated margin.

Besides mineral surface area (or mineral grain size), the mineral composition is also an important factor for accumulation of sedimentary OC in marine environment. Blattmann et al. (2019) found that in the South China Sea, continentally derived OM of pedogenic origin is stripped from smectite mineral surfaces upon discharge, dispersal, and sedimentation in distal ocean settings, whereas OM sourced from ancient rocks that is tightly associated with mica and chlorite endures in the marine realm. Thus, the future study should focus on the relationship between mineral compositions and OM in the lower Yangtze River–East China Sea continuum to better understand the source, transport, and accumulation of OC in the river-dominated margin.

Overall, the DOC contents of the WEOM and BEOM presented similar distribution patterns from the lower Yangtze River to East China Sea, which was lower in riverine sediments and higher in estuarine and coastal sediments (Figure 5C). However, from sites R5 to S6, the DOC content of the BEOM was three times higher than that of the WEOM, suggesting selective accumulation of BEOM-derived OC in the estuarine and coastal sediments. The terrigenous OM, such as humic-like substances (e.g., C1), although relatively bio-refractory because of high aromaticity, could be photo-degraded once released from the mineral matrix (McKnight and Aiken, 1998). This desorption–degradation pathway is more efficient for OC in the WEOM, leading to the selective accumulation of the BEOM in the mixing zone of freshwater and seawater.

Distributional patterns of SUVA254, FI, and BIX were different between the WEOM and BEOM (Figures 5D–F). For the WEOM, the SUVA254 values were higher in the lower Yangtze River (R1–R4) and site R5 compared to other sites (S1–S6), whereas for the BEOM, the SUVA254 values did not show a clear trend from the river to the sea. The SUVA254 of the WEOM in the lower Yangtze River (>3 L∗mg C–1 ∗m–1) was greater than that in Korean rivers (average 1.4 L∗mg C–1) (He et al., 2016). This was attributed to intense human activities and serious soil erosion in the lower Yangtze River. Unlike the SUVA254 and HIX, the FI and BIX of the WEOM displayed an increasing trend seaward (Figures 5E,F), suggesting enhanced contributions of algal/bacterial OC. While for the BEOM, the FI and BIX generally decreased during the seaward transport, reached the lowest level in the estuary (site S1) and slightly increased seaward from S2 (Figures 5E,F). These characteristics suggested that the proportion of terrigenous OC in the WEOM pool was the highest in the lower Yangtze River and the lowest in the East China Sea, whereas the proportion of microbial OC in the BEOM pool was the highest in the lower Yangtze River and the lowest in the estuary. These contrasting patterns may be explained by three factors: (1) large contribution of surface soil and plant-derived OC from surrounding areas that was weakly associated with sediments (WEOM) (Guo et al., 2014); (2) erosion of deep soil OC that was strongly associated with minerals (BEOM) and contained more than 50% OC from microbial necromass (Kogel-Knabner, 2002; Liang et al., 2019); and (3) limited photosynthesis of OC because of high turbidity in the Yangtze River Estuary (maximum turbidity zone), resulting in low fresh OC contribution to the WEOM (He and Lu, 2001; Yang et al., 2014).

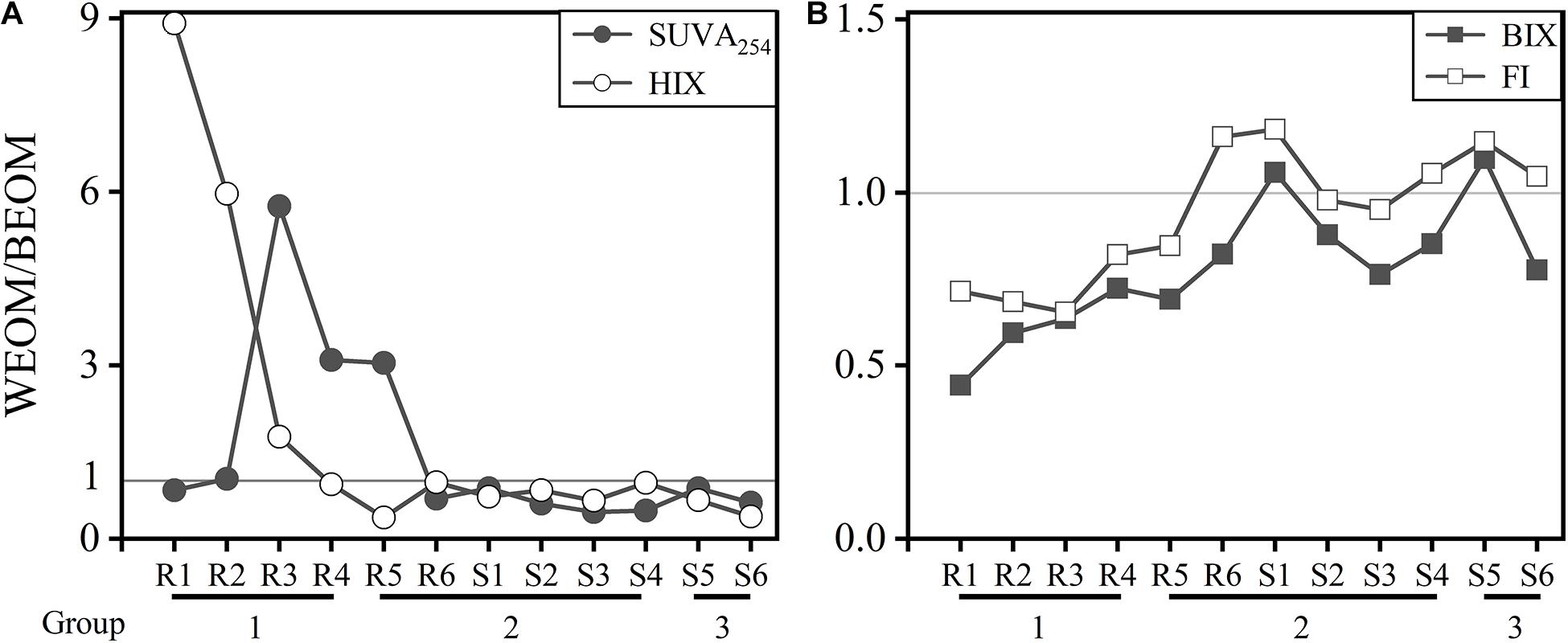

We calculated the ratios of optical indicators between the WEOM and BEOM in order to assess compositional differences. The ratio of (SUVA254)WEOM/BEOM was generally higher than 1 in the lower Yangtze River but lower than 1 in the East China Sea (Figure 6A). Similar spatial variations were observed for the HIXWEOM/BEOM that substantially decreased from site R1 (>8.0) to R5 (<0.4) and remained lower than 1 from S1 to S6. These results suggested that humic-like substance with high aromaticity was more abundant in weak OC–sediment association (WEOM), which was likely attributed to large terrigenous OC inputs by intense human activities. During the downriver transport, humic-like substances of the WEOM underwent fast exchange with ambient waters and may be degraded. However, a minor fraction of humic-like substances was strongly associated with sediments (BEOM) and could be transported from the river to the sea. This was consistent with higher intensities of C1 and C2 in the estuary and East China Sea (R4–S4) for the BEOM compared to the WEOM (Figure 4).

Figure 6. Optical indicator ratio [specific UV absorbance at 254 nm (SUVA254), humification index (HIX), fluorescence index (FI), and biological index (BIX)] between the water-extractable organic matter (WEOM) (A) and base-extractable organic matter (BEOM) (B).

The ratios of FIWEOM/BEOM (0.65–0.84) and BIXWEOM/BEOM (0.50–0.75) were lower than 1 at sites R1–R5, suggesting the depletion of algal/microbial OC in the WEOM and the enrichment of algal/microbial OC in the BEOM (Figure 6B). This agreed with the high ratios of (SUVA254)WEOM/BEOM (up to 5.60) and HIXWEOM/BEOM (up to 8.91) that suggested higher abundance of allochthonous terrigenous OC in the WEOM. Meanwhile, both FIWEOM/BEOM and BIXWEOM/BEOM displayed an increasing trend from sites R1 to R5, suggesting an increase of microbial OC contributions to the WEOM, or the selective removal of terrigenous OC in the WEOM during the downriver transport. The latter was also supported by downriver decreases of (SUVA254)WEOM/BEOM and HIXWEOM/BEOM (Figure 6A). After out of the river mouth, (SUVA254)WEOM/BEOM and HIXWEOM/BEOM were relatively constant. Thus, compared to highly dynamic changes in the lower river and estuary, the WEOM and BEOM in the East China Sea were subject to less selective transformation and degradation.

Our study suggests that optical spectroscopy is a useful technique for assessment of source, transport, and accumulation of OC in the Yangtze River-dominated margin. However, the combination between this cheap, high-throughput analysis and other analytical techniques, such as stable and radiocarbon isotopic techniques, is highly recommended for a coherent understanding of OC cycling (Wagner et al., 2020). Particularly, compound-specific stable and radiocarbon measurements provide information on source and turnover time of OC at the molecular level (biomarker with specific source) that can disentangle terrigenous and marine signals from complex environmental settings like the river-dominated margin. Thus, the future study will investigate biomarkers and their stable and radiocarbon isotopic compositions in sediments along the lower Yangtze River–East China Sea continuum that will be used to compare with our optical parameters.

In the present study, we have investigated concentrations and optical characteristics of OM between dissolved and particulate phases in surface sediments along the transect of lower Yangtze River–Estuary–East China Sea. Three conclusions were reached:

(1) Three components (C1, C2, C3) were extracted from the EEM-PARAFAC of the WEOM and BEOM, namely, terrigenous humic-like C1, terrigenous/aquatic humic-like C2, and microbial protein-like C3.

(2) Although the OC contents of the WEOM, BEOM, and bulk sediments presented similar distributional patterns (highest in the estuary, intermediate in the coastal sea, and lowest in the river) and strongly correlated with sediment grain size, the compositional distributions were apparently different between the WEOM and BEOM. The BIX, FI, SUVA254, C1%, and C3% correlated with water salinity and sediment grain size for the WEOM (in situ control) and BEOM (allochthonous control), respectively.

(3) During the downriver transport, significant loss of terrigenous OC in the WEOM was reflected by the decrease of the C1%, HIX, and SUVA254. The terrigenous humic-like substance was more abundant in the WEOM in the lower Yangtze River but becomes depleted compared to the BEOM in the East China Sea. In contrast, microbial OC was enriched in the BEOM in the lower Yangtze River but comparable between the BEOM and WEOM in the East China Sea due to in situ products of algal/bacterial OC to the latter. Our study demonstrates high dynamics in content and composition of sedimentary OM in the Yangtze River-dominated margin, which was significantly influenced by the binding strength of OM–sediment matrix. Future studies will investigate mineral compositions and compound-specific carbon isotopic compositions for a holistic understanding of OC cycling in this complex river-dominated margin.

The datasets are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13089143.v1.

LH contributed to the investigation, methodology, software, writing the original manuscript, and sample collection. YiW contributed to the software, investigation, methodology, and writing, review, and editing. YX contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, methodology, and writing, review, and editing, and funding acquisition. YaW contributed to the investigation, software, and writing, review, and editing. YZ contributed to the investigation, methodology, and software. JW contributed to the methodology, software, and writing, review, and editing. All authors contributed to the manuscript review and preparation.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41676058). Samples and partly data were collected onboard R/V “Zheyuke#2” implementing the open research cruise supported by NSFC Shiptime Sharing Project (NORC2019-03-02).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Bao, H., Wu, Y., and Zhang, J. (2015). Spatial and temporal variation of dissolved organic matter in the Changjiang: fluvial transport and flux estimation. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeol. 120, 1870–1886. doi: 10.1002/2015jg002948

Bianchi, T. S., Mitra, S., and McKee, B. A. (2002). Sources of terrestrially-derived organic carbon in lower Mississippi River and Louisiana shelf sediments: implications for differential sedimentation and transport at the coastal margin. Mar. Chem. 77, 211–223. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4203(01)00088-3

Blattmann, T. M., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Y., Haghipour, N., Montluçon, D. B., et al. (2019). Mineralogical control on the fate of continentally derived organic matter in the ocean. Science 366, 742–745. doi: 10.1126/science.aax5345

Burdige, D. J. (2007). Preservation of organic matter in marine sediments: controls, mechanisms, and an imbalance in sediment organic carbon budgets? Chem. Rev. 107, 467–485. doi: 10.1021/cr050347q

Chen, M., and Hur, J. (2015). Pre-treatments, characteristics, and biogeochemical dynamics of dissolved organic matter in sediments: a review. Water Res. 79, 10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.04.018

Cory, R. M., Miller, M. P., McKnight, D. M., Guerard, J. J., and Miller, P. L. (2010). Effect of instrument-specific response on the analysis of fulvic acid fluorescence spectra. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 8, 67–78. doi: 10.4319/lom.2010.8.0067

Dagg, M., Benner, R., Lohrenz, S., and Lawrence, D. (2004). Transformation of dissolved and particulate materials on continental shelves influenced by large rivers: plume processes. Cont. Shelf Res. 24, 833–858. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2004.02.003

Ding, Y. H. (1992). Summer monsoon rainfalls in China. J. Meteorol. Soc. JPN. 70, 373–396. doi: 10.2151/jmsj1965.70.1B_373

Fellman, J. B., Hood, E., and Spencer, R. G. M. (2010). Fluorescence spectroscopy opens new windows into dissolved organic matter dynamics in freshwater ecosystems: a review. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 2452–2462. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.6.2452

Gao, L., Li, D.-J., and Ding, P.-X. (2009). Quasi-simultaneous observation of currents, salinity and nutrients in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) plume on the tidal timescale. J. Mar. Syst. 75, 265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2008.10.006

Goñi, M. A., Teixeira, M. J., and Perkey, D. W. (2003). Sources and distribution of organic matter in a river-dominated estuary (Winyah Bay, SC, USA). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 57, 1023–1048. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7714(03)00008-8

Guo, W., Yang, L., Zhai, W., Chen, W., Osburn, C. L., Huang, X., et al. (2014). Runoff-mediated seasonal oscillation in the dynamics of dissolved organic matter in different branches of a large bifurcated estuary-The Changjiang Estuary. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeol. 119, 776–793. doi: 10.1002/2013jg002540

He, W., Jung, H., Lee, J.-H., and Hur, J. (2016). Differences in spectroscopic characteristics between dissolved and particulate organic matters in sediments: insight into distribution behavior of sediment organic matter. Sci. Total Environ. 547, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.146

He, W.-S., and Lu, J.-J. (2001). Effects of high-density suspended sediments on primary production at the Yangtze Estuary. Chinese J. Eco-Agric. 4:24.

Hedges, J. I., Keil, R. G., and Benner, R. (1997). What happens to terrestrial organic matter in the ocean? Org. Geochem. 27, 195–212. doi: 10.1016/s0146-6380(97)00066-1

Huguet, A., Vacher, L., Relexans, S., Saubusse, S., Froidefond, J. M., and Parlanti, E. (2009). Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Org. Geochem. 40, 706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.03.002

Hur, H. B., Jacobs, G. A., and Teague, W. J. (1999). Monthly variations of water masses in the Yellow and East China Seas. J. Oceanogr. 56, 171–184. doi: 10.1023/A:1007885828278

Jia, G.-D., and Peng, P.-A. (2003). Temporal and spatial variations in signatures of sedimented organic matter in Lingding Bay (Pearl estuary), southern China. Mar. Chem. 82, 47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4203(03)00050-1

Jiang, Y., Zhao, J., Li, P., and Huang, Q. (2016). Linking optical properties of dissolved organic matter to multiple processes at the coastal plume zone in the East China Sea. Environ. Sci. Proc. Imp. 18, 1316–1324. doi: 10.1039/C6EM00341A

Kleber, M., Sollins, P., and Sutton, R. (2007). A conceptual model of organo-mineral interactions in soils: self-assembly of organic molecular fragments into zonal structures on mineral surfaces. Biogeochemistry 85, 9–24. doi: 10.1007/s10533-007-9103-5

Koch, B. P., Witt, M. R., Engbrodt, R., Dittmar, T., and Kattner, G. (2005). Molecular formulae of marine and terrigenous dissolved organic matter detected by electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 3299–3308. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2005.02.027

Kogel-Knabner, I. (2002). The macromolecular organic composition of plant and microbial residues as inputs to soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 34, 139–162. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00158-4

Lalonde, K., Mucci, A., Ouellet, A., and Gélinas, Y. (2012). Preservation of organic matter in sediments promoted by iron. Nature 483, 198–200. doi: 10.1038/nature10855

Li, B., Liao, C.-H., Zhang, X.-D., Chen, H.-L., Wang, Q., Chen, Z.-Y., et al. (2009). Spartina alterniflora invasions in the Yangtze River estuary, China: an overview of current status and ecosystem effects. Ecol. Eng. 35, 511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.05.013

Li, P., Chen, L., Zhang, W., and Huang, Q. (2015). Spatiotemporal distribution, sources, and photobleaching imprint of dissolved organic matter in the Yangtze estuary and its adjacent sea using fluorescence and parallel factor analysis. PLoS One 10:e0130852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130852

Liang, C., Amelung, W., Lehmann, J., and Kästner, M. (2019). Quantitative assessment of microbial necromass contribution to soil organic matter. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3578–3590. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14781

Liu, J. P., Xu, K. H., Li, A. C., Milliman, J. D., Velozzi, D. M., Xiao, S. B., et al. (2007). Flux and fate of Yangtze River sediment delivered to the East China Sea. Geomorphology 85, 208–224. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.03.023

Mayer, L. M. (1994). Surface area control of organic carbon accumulation in continental shelf sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 1271–1284. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(94)90381-6

McKnight, D. M., and Aiken, G. R. (1998). “Sources and age of aquatic humus,” in Aquatic Humic Substances: Ecology and Biogeochemistry, eds D. O. Hessen and L. J. Tranvik (Berlin: Springer), 9–39.

McKnight, D. M., Boyer, E. W., Westerhoff, P. K., Doran, P. T., Kulbe, T., and Andersen, D. T. (2001). Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 38–48. doi: 10.4319/lo.2001.46.1.0038

Meyers, P. A. (1997). Organic geochemical proxies of paleoceanographic, paleolimnologic, and paleoclimatic processes. Org. Geochem. 27, 213–250. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00049-1

Murphy, K. R., Ruiz, G. M., Dunsmuir, W. T. M., and Waite, T. D. (2006). Optimized parameters for fluorescence-based verification of ballast water exchange by ships. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 2357–2362. doi: 10.1021/es0519381

Murphy, K. R., Stedmon, C. A., Graeber, D., and Bro, R. (2013). Fluorescence spectroscopy and multi-way techniques. PARAFAC. Anal. Methods 5, doi: 10.1039/c3ay41160e

Osburn, C. L., Handsel, L. T., Mikan, M. P., Paerl, H. W., and Montgomery, M. T. (2012). Fluorescence tracking of dissolved and particulate organic matter quality in a river-dominated estuary. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 8628–8636. doi: 10.1021/es3007723

Raymond, P. A., and Spencer, R. G. M. (2015). “Chapter 11 - Riverine DOM,” in Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter, 2nd Edn, eds D. A. Hansell and C. A. Carlson (Boston: Academic Press), 509–533.

Schmidt, M. W. I., Torn, M. S., Abiven, S., Dittmar, T., Guggenberger, G., Janssens, I. A., et al. (2011). Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 478, 49–56. doi: 10.1038/nature10386

Stedmon, C. A., and Markager, S. (2003). Behaviour of the optical properties of coloured dissolved organic matter under conservative mixing. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 57, 973–979. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7714(03)00003-9

Stedmon, C. A., and Markager, S. (2005). Tracing the production and degradation of autochthonous fractions of dissolved organic matter by fluorescence analysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 1415–1426. doi: 10.4319/lo.2005.50.5.1415

Wagner, S., Schubotz, F., Kaiser, K., Hallmann, C., Waska, H., Rossel, P. E., et al. (2020). Soothsaying DOM: a current perspective on the future of oceanic dssolved organic carbon. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:341. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00341

Wang, Y., Zhang, D., Shen, Z., Feng, C., and Chen, J. (2013). Revealing sources and distribution changes of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in pore wter of sediment from the Yangtze Estuary. PLoS One 8:e76633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076633

Wei, Q., Wang, B., Chen, J., Xia, C., Qu, D., and Xie, L. (2015). Recognition on the forming-vanishing process and underlying mechanisms of the hypoxia off the Yangtze River estuary. Sci. China Ear. Sci. 58, 628–648. doi: 10.1007/s11430-014-5007-0

Weishaar, J. L., Aiken, G. R., Bergamaschi, B. A., Fram, M. S., Fujii, R., and Mopper, K. (2003). Evaluation of specific ultraviolet absorbance as an indicator of the chemical composition and reactivity of dissolved organic carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 4702–4708. doi: 10.1021/es030360x

Wu, W., Ruan, J., Ding, S., Zhao, L., Xu, Y., Yang, H., et al. (2014). Source and distribution of glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers along lower Yellow River-estuary–coast transect. Mar. Chem. 158, 17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2013.11.006

Xu, F., Yang, S.-Y., Zhan, W. L. I., and Qian, P. (2011). Influence of the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir on the flux and isotopic composition of particulate organic carbon in the lower Changjiang mainstream. Geochimica 40, 199–208. doi: 10.19700/j.0379-1726.2011.02.009

Yang, S. L., Zhang, J., Dai, S. B., Li, M., and Xu, X. J. (2007). Effect of deposition and erosion within the main river channel and large lakes on sediment delivery to the estuary of the Yangtze River. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 112:F02005. doi: 10.1029/2006JF000484

Yang, Y., Li, Y., Sun, Z., and Fan, Y. (2014). Suspended sediment load in the turbidity maximum zone at the Yangtze River Estuary: the trends and causes. J. Geograph. Sci. 24, 129–142. doi: 10.1007/s11442-014-1077-3

Yu, X., Shen, F., and Liu, Y. (2016). Light absorption properties of CDOM in the Changjiang (Yangtze) estuarine and coastal waters: an alternative approach for DOC estimation. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 181, 302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2016.09.004

Keywords: Yangtze River, East China Sea, organic carbon, parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC), optical indicator

Citation: Han L, Wang Y, Xu Y, Wang Y, Zheng Y and Wu J (2021) Water- and Base-Extractable Organic Matter in Sediments From Lower Yangtze River–Estuary–East China Sea Continuum: Insight Into Accumulation of Organic Carbon in the River-Dominated Margin. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:617241. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.617241

Received: 14 October 2020; Accepted: 11 January 2021;

Published: 11 February 2021.

Edited by:

Selvaraj Kandasamy, Xiamen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Thomas Michael Blattmann, Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), JapanCopyright © 2021 Han, Wang, Xu, Wang, Zheng and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yunping Xu, eXB4dUBzaG91LmVkdS5jbg==; orcid.org/0000-0001-5693-7239; Jianqiang Wu, d3VqcUBzYWVzLnNoLmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.