95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 25 February 2021

Sec. Global Change and the Future Ocean

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.576746

This article is part of the Research Topic Biogeochemical Consequences of Climate-Driven Changes in the Arctic View all 11 articles

Arctic marine ecosystems are undergoing a series of major rapid adjustments to the regional amplification of climate change, but there is a paucity of knowledge about how changing environmental conditions might affect reproductive cycles of seafloor organisms. Shifts in species reproductive ecology may influence their entire life-cycle, and, ultimately, determine the persistence and distribution of taxa. Here, we investigate whether the combined effects of warming and ocean acidification based on near-future climate change projections affects the reproductive processes in benthic bivalves (Astarte crenata and Bathyarca glacialis) from the Barents Sea. Both species present large oocytes indicative of lecithotrophic or direct larval development after ∼4 months exposure to ambient [<2°C, ∼400 ppm (CO2)] and near-future [3–5°C, ∼550 ppm (CO2)] conditions, but we find no evidence that the combined effects of acidification and warming affect the size frequency distribution of oocytes. Whilst our observations are indicative of resilience of this reproductive stage to global changes, we also highlight that the successful progression of gametogenesis under standard laboratory conditions does not necessarily mean that successful development and recruitment will occur in the natural environment. This is because the metabolic costs of changing environmental conditions are likely to be offset by, as is common practice in laboratory experiments, feeding ad libitum. We discuss our findings in the context of changing food availability in the Arctic and conclude that, if we are to establish the vulnerability of species and ecosystems, there is a need for holistic approaches that incorporate multiple system responses to change.

Ocean acidification and warming are synergistic environmental stressors (Byrne et al., 2013a) that can affect whole animal physiology (Pörtner and Farrell, 2008). However, the extent to which reproduction and life history strategy are vulnerable to environmental change has received comparatively little attention (Ross et al., 2011). Reproduction underpins the success of populations over time and, regardless of parental survivorship and tolerance capability, negative species responses to novel circumstances at early life cycle stages have the potential to serve as a bottleneck to long-term population survival (Dupont et al., 2010a). Species responses to changing environmental conditions have been shown to carry a high energetic cost in marine calcifiers (Spalding et al., 2017), especially at higher latitudes (Watson et al., 2017), and at earlier stages in the life cycle (Ross et al., 2011; Foo and Byrne, 2017). This is particularly concerning in polar environments where species responses to global climate change and ocean acidification are widely considered to be regionally amplified (Miller et al., 2010). Discerning the direction and generality of effect, however, is frustrated by the effects of transgenerational plasticity (Karelitz et al., 2019; Kong et al., 2019; Byrne and Hernández, 2020; Byrne et al., 2020), as well as intra-specific variations in sensitivity (Przeslawski et al., 2015) and response (Carr et al., 2006; Campbell et al., 2016; Boulais et al., 2017). In addition, maternal environmental history has been shown to affect egg size and volume (Braun et al., 2013) which, in turn, can induce phenotypic responses in larvae (Byrne et al., 2020).

Overall, the combined effects of ocean acidification and temperature on early gamete development are poorly constrained (Boulais et al., 2017) with most available information focused on gamete viability post spawning or larval development in a limited number of taxonomic groups (see review by Ross et al., 2011 and meta-analysis by Kroeker et al., 2010). By focusing on the later stages of a species reproductive cycle, sensitivities of gametogenesis or fertilization mechanisms are missed, stimulating debate about the potential for reproductive cycles to be disrupted (Dupont et al., 2010a; Hendriks and Duarte, 2010). Indeed, empirical evidence for the echinoderms indicates that ocean acidification can result in delayed but normal gametogenesis (Kurihara et al., 2013), reduced sperm volumes (Uthicke et al., 2013), lower gonad indices (Stumpp et al., 2012), or smaller eggs (Suckling et al., 2015). However, experimental manipulation of acidification in other taxa, including corals (Jokiel et al., 2008; Gizzi et al., 2017), annelids (Gibbin et al., 2017), molluscs (Parker et al., 2017), crustaceans (Thor and Dupont, 2015), and several miscellaneous species (for comprehensive list see Foo and Byrne, 2017), reveal no effects on egg size, gametogenesis, or development. Hence, considerable uncertainty exists in understanding the impact of climatic forcing on individual species within the context of the wider ecosystem, but it is clear that the earliest stages of gamete development need to be considered whilst adequately addressing variations within populations and regional environmental change (Dupont and Pörtner, 2013).

While many regionally abundant benthic invertebrate species have shown physiological tolerance to environmental forcing, often explained by, or attributed to, their boreal evolutionary histories (Richard et al., 2012), the viability of Arctic populations through their ability to reproduce is not currently known. Here, we used two abundant and functionally important benthic bivalves, Bathyarca glacialis and Astarte crenata from the Barents Sea (Cochrane et al., 2009; Solan et al., 2020), a region undergoing rapid change including ice retreat (Polyakov et al., 2012a), increasing sea surface temperatures (Polyakov et al., 2012b), and ocean acidification (Qi et al., 2017), to examine the combined effects of warming and ocean acidification on gamete development. Both species are reported to have large oocytes all year round indicative of lecithotrophic or direct development, and without seasonal or cyclic patterns of oocyte development (Saleuddin, 1965; Von Oertzen, 1972; Oliver et al., 1980). Our a priori expectation was that the physiological cost of near future conditions would indirectly affect reproduction, expressed via a trade-off with egg size or increased oocyte reabsorption, with consequences for the long-term viability of the population.

Specimens of the infaunal bivalves Bathyarca glacialis and Astarte crenata were collected in July 2017 and 2018, respectively, by Agassiz trawl in the Barents Sea (74–81°N, along 30°E meridian, 292–363 m depth, JR16006 and JR17007, RRS James Clark Ross, Supplementary Table 1). Similarly sized individuals of each species (Supplementary Table 2) were maintained in aerated seawater (salinity 35, 1.5 ± 0.5°C), and returned to the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Futures Facility, University of Southampton. Surficial sediment (less than 10 cm depth: year 2017, mean particle size = 28.06 μm, organic material, 6.74%; 2018, mean particle size = 26.51 μm, organic material, 6.21%; Solan et al., 2020, Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 1) was collected using SMBA box cores in the Barents Sea (year 2017, Station B13, 74.4998°N 29.9982°E, 346 m depth; year 2018, Station B16, 80.1167°N 30.0683°E, 280 m depth, and Station B17, 81.2816°N, 29.3269°E, 334 m depth), sieved to remove macrofauna (500 μm mesh), homogenized by stirring, and transported back to the University of Southampton at ambient temperature (1.5 ± 1°C).

We exposed individuals of Bathyarca glacialis and Astarte crenata to ambient [1–2°C, ∼400 ppm (CO2)] and near-future [3–5°C, ∼550 ppm (CO2)] based on IPCC RCP 4.5 and 6.0 future projections for around the year 2050–2080, IPCC, 2013) temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide scenarios for the Barents Sea. Aquaria (L × W × H: 20 cm × 20 cm × 34 cm, transparent acrylic) were continually aerated by bubbling a treatment-specific air-CO2 mixture through a glass pipette (Godbold and Solan, 2013) and were filled with 10 cm of homogenized sediment overlain by 20 cm of seawater (∼ 8 L, salinity 34). The aquaria were maintained in the dark and randomly distributed between two insulated water baths within each treatment (Solan et al., 2020). Three B. glacialis were introduced to each of twelve aquaria (n = 36) and six A. crenata were introduced to each of ten aquaria (n = 60). After acclimation to aquarium conditions at ambient temperature and CO2 [30 days, 1–2°C, ∼400 ppm (CO2)], temperature and (CO2) were adjusted manually (1°C and ∼100 ppm CO2 week–1) to achieve the near-future treatment conditions. No mortality was recorded during this period. We periodically measured pH [NBS scale, Mettler-Toledo (United States) InLab Expert Pro temperature–pH combination electrode], temperature and salinity (Mettler-Toledo InLab 737 IP67 temperature–conductivity combination electrode), and total alkalinity (HCl titration by Marianda VINDTA, Canada). Concentrations of bicarbonate (HCO3–), carbonate (CO32–), and pCO2 were calculated from measured pH, total alkalinity, temperature, and salinity (Dickson et al., 2007; Dickson, 2010) using CO2calc (Robbins et al., 2010) with appropriate solubility constants (Mehrbach et al., 1973, refit by Dickson and Millero, 1987) and KSO4 (Dickson, 1990; Supplementary Figures 2, 3).

The bivalves were fed consistently throughout the acclimation and experiment period ad libitum three times per week with 100 ml cultured live phytoplankton (mixed Isochrysis sp., Tetraselmis sp., and Phaeodactylum sp.) at peak culture densities of 15.6 × 106 cells ml–1, 8.6 × 105 cells ml–1, and 14.2 × 106 cells ml–1, respectively. This equates to ∼0.197 g algae per day and represents 9.93 and 6.42% of algal weight/bivalve wet mass in Astarte and Bathyarca, respectively. Uneaten food was observed settled on the sediment surface which was used as an indicator of feeding ad libitum, and overlying sea water was replaced weekly (partial exchange, ∼80%) to prevent the accumulation of excess nutrients. Experiments were run for 120 days (B. glacialis, 21/11/2017–20/03/2018) or 135 days (A. crenata, 8/10/2018 – 19/02/2019) after which animals were removed and fixed in 4% neutral buffered formaldehyde for approximately 1 month before being prepared for histological examination. No premature mortality was recorded.

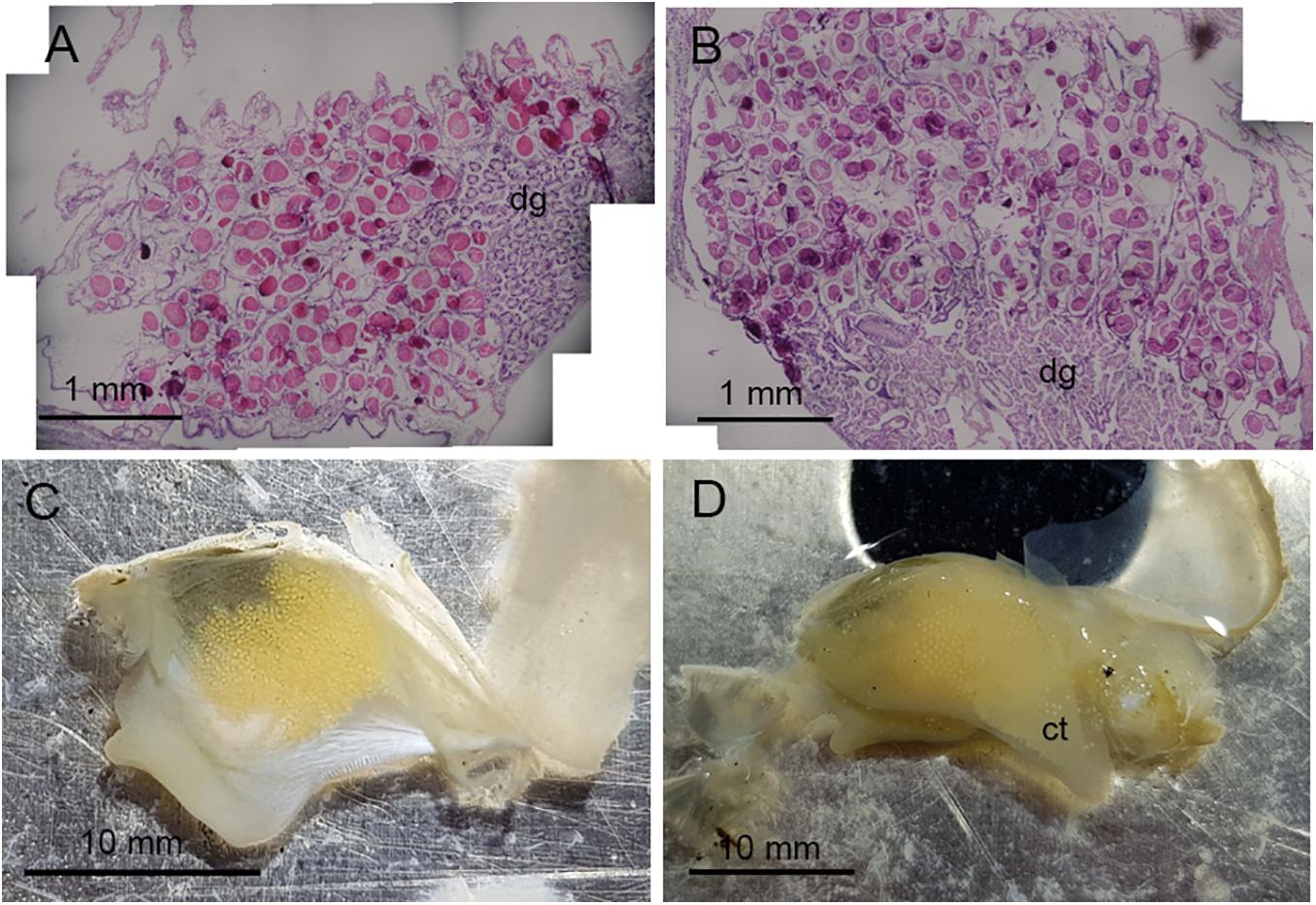

Bivalves were selected for histology within a defined size range (A. crenata 25–30 mm shell length; B. glacialis 20–25 mm shell length). For each individual [A. crenata, n = 37 (19 ambient, 18 future); B. glacialis, n = 24 (12 ambient, 12 future)], maximum shell length, height, and tumidity were measured using a digital caliper (±0.01 mm) (Supplementary Table 2), before soft tissue was removed from the shell, wet weighed (±0.001 g), and prepared for histology. Dissection revealed that both species have gonads which infiltrate and partially envelop the digestive diverticula (Figure 1A) so, as it was not tractable to perform a dissection of the germinal tissue, we adopted whole animal histology for reproductive analysis.

Figure 1. Oocyte development in Astarte crenata from the Barents Sea. Transverse histology sections show oocyte development (A) surrounding the digestive diverticula under ambient environmental conditions and (B) in the gonadal alveoli under representative future environmental conditions. Microphotographs show (C) the arrangement of oocytes when within the gonad and (D) oocytes loosely held within the supra-branchial chamber on the ctenidia found in the future environmental conditions. dg, digestive diverticula; ct, ctenidia.

Soft tissue of each specimen was processed for histology according to the protocols described by Lau et al. (2018). In brief, tissue was dehydrated in isopropanol (70–100%), cleared in XTF (CellPath Ltd., United Kingdom) and embedded in 25 mm × 50 mm paraffin wax blocks. Embedded tissue was cut at 6–7 μm, mounted onto slides and stained using hematoxylin Z (CellPath Ltd., United Kingdom), counter stained with eosin Y (CellPath, United Kingdom), and immediately cover-slipped using a DPX mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich, United Kingdom). Oocytes were captured using a Nikon D5000 digital SLR camera mounted onto an Olympus (BH-2) stereomicroscope and analyzed using ImageJ v 1.48 (Schneider et al., 2012).

Unique oocytes were measured only when a nucleus was visible to ensure the near maximum cross sectional diameter. The size of each oocyte was standardized to the diameter of a circle with an equal aggregate sectional area to the two dimensional section of the imaged oocyte [Equivalent Circular Diameter (ECD), Lau et al., 2018], comparable to the Oocyte Feret Diameter used in previous studies (Higgs et al., 2009; Reed et al., 2014). For each female with more than 100 sectioned oocytes, we calculated the ECD of 100 oocytes in each female (five females and 500 oocytes per treatment in each species). A Chi-squared test of independence was conducted between individual females in each experiment treatment to determine a statistically significant association in oocyte size frequencies (Supplementary Figures 4, 5). Oocyte length frequency distributions for each treatment were pooled to represent the natural variation within individuals, and were analyzed with a Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test between treatments. All analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2018 v.1.2.5019) and the fishmethods library was used for analysis of the length frequency distribution and K–S test (Nelson, 2019).

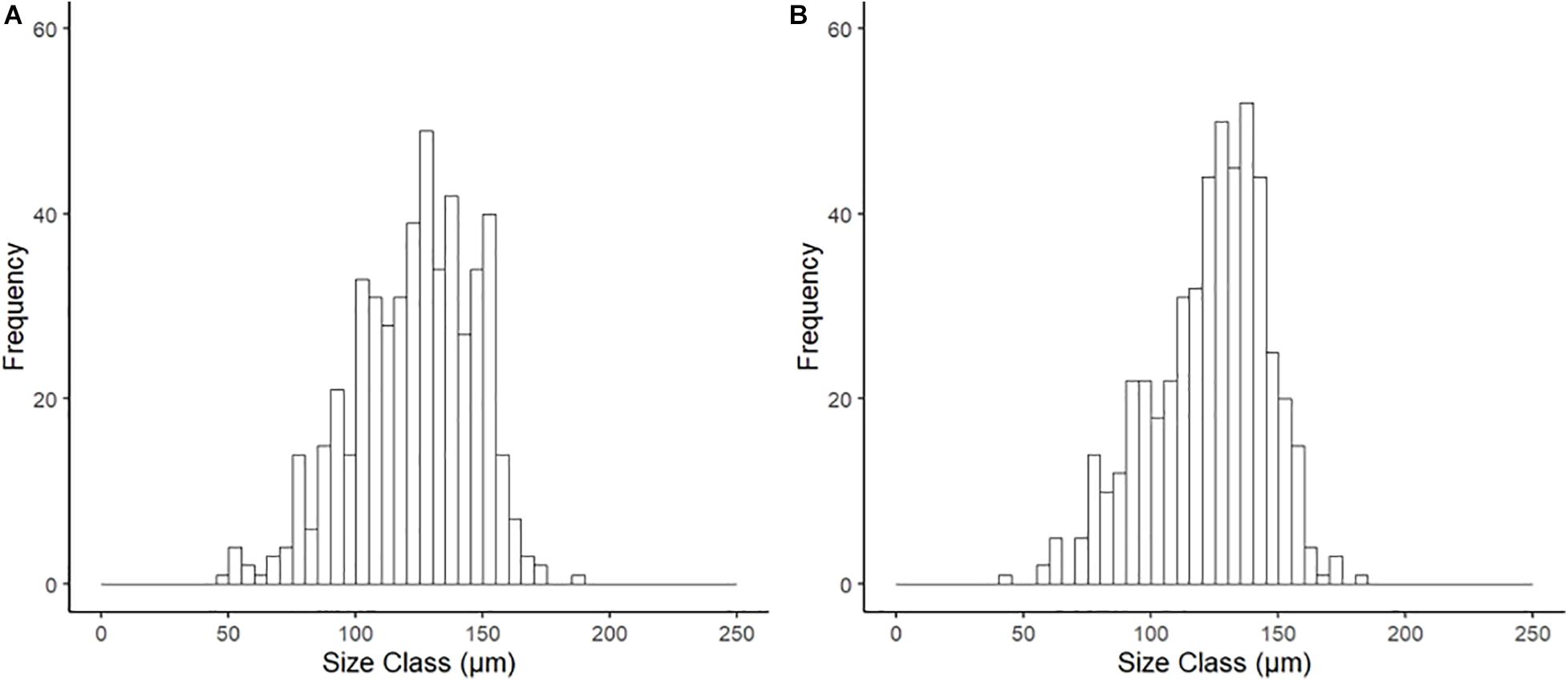

Examination of the reproductive organs of A. crenata confirmed 16 females and 21 males with no evidence of hermaphroditism, and one specimen with no discernible gonad tissue. Oocytes were developing in reproductive organs infiltrating the digestive diverticula (Figure 1A) and consisted of interconnected gonadal alveoli (Figures 1B,C). In four specimens in the future climate treatment, oocytes were loosely held within the supra-branchial chamber and reproductive organs simultaneously (Figure 1D). Evidence of primary oogenesis was not observed, however, oocytes measured between 46.96 and 185.08 μm (mean ± SD 122.61 ± 22.84 μm, n = 500) in the ambient conditions (Figure 2A), and 44.61–181.93 μm (mean ± SD 122.48 ± 24.08, n = 500) in the future conditions (Figure 2B), with no notable evidence of atresia. The oocyte size distributions were not treatment specific (2-tailed K–S test, D(116) = 0.062, p = 0.99), and showed a distributional peak between 100 and 150 μm.

Figure 2. Size frequency of oocytes for Astarte crenata from the Barents Sea following incubation (20 weeks) under (A) ambient and (B) representative future climate conditions. There was no difference in distribution between treatments (2-tailed K–S test, D(116) = 0.062, p = 0.99).

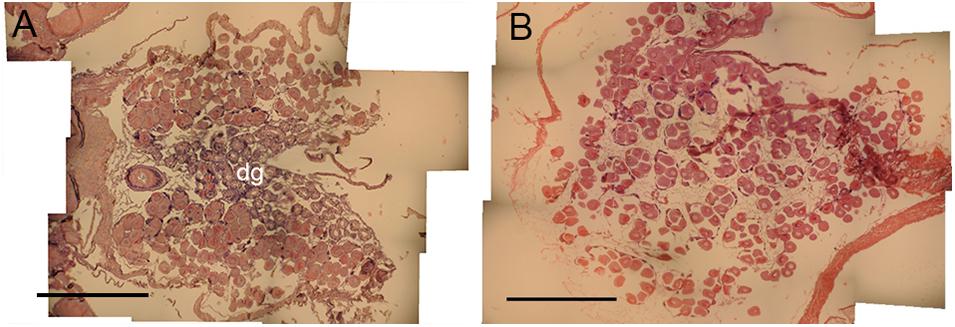

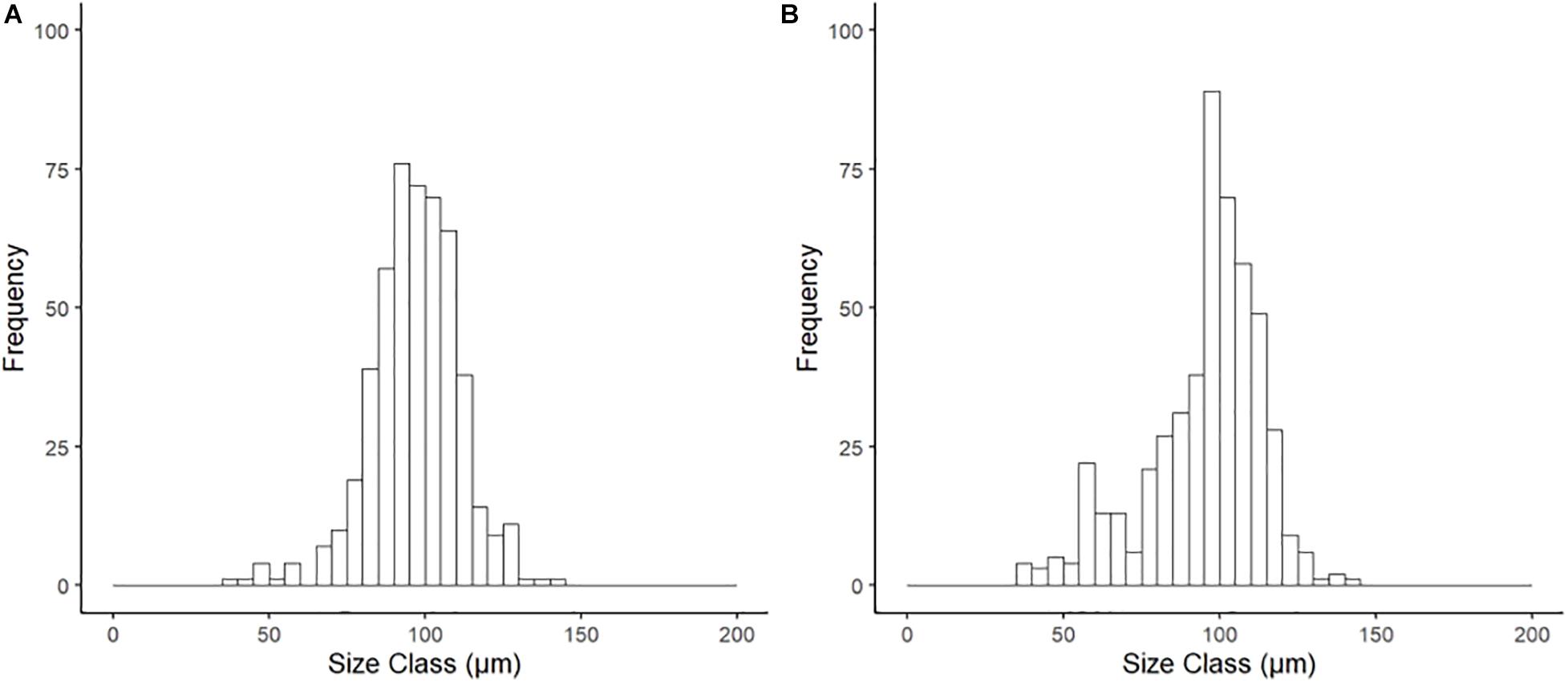

Histological examination of reproductive organs of B. glacialis revealed 10 females and 14 males with no evidence of hermaphroditism. Gonads were positioned partially infiltrating the digestive diverticula (Figure 3A) and were observed in densely packed anterior-posterior tubular pouches up to six oocytes across (Figures 3A,B). Oocytes measured between 39.60 and 144.77 μm (mean ± SD 96.77 ± 14.36 μm, n = 500) in the ambient conditions, and 35.07–144.90 μm (mean ± SD 95.03 ± 18.57 μm, n = 500) in the future conditions, with no notable evidence of atresia. The oocyte size distributions were not treatment specific (2-tailed K–S test, D(94) = 0.122, p = 0.81), but showed a peak at 85 μm following exposure to ambient conditions (Figure 4A) and 95 μm following exposure to future conditions (Figure 4B).

Figure 3. Oocyte development in Bathyarca glacialis from the Barents Sea. Transverse histology sections show (A) reproductive organs and oocytes infiltrating the digestive diverticula under ambient environmental conditions and (B) oocyte development under representative future environmental conditions. dg, digestive diverticula. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Figure 4. Size frequency of oocytes for Bathyarca glacialis from the Barents Sea following incubation (20 weeks) under (A) ambient and (B) representative future climate conditions. There was no significant difference in distribution between treatments (2-tailed K–S test, D(94) = 0.122, p = 0.81).

We have demonstrated, for two abundant species of Arctic-boreal bivalve, evidence of gametogenic resilience to projected near-future atmospheric carbon dioxide (550 ppm CO2) and sea temperature (+3°C), after a 20 week incubation. Our observations show no difference in oocyte size frequency or physical structure, and in this respect are consistent with other studies (Kurihara et al., 2013; Verkaik et al., 2017). However, the interpretation of reproductive resilience based on a gametogenic response risks the generalization of a fundamental physiological output impacting on population dynamics, and does not take into account prolonged developmental cycles in cold water (Peck, 2016; Moran et al., 2019), or the effects on viability, fertilization, and larval development (Dupont et al., 2010a). The maximum oocyte sizes in A. crenata and B. glacialis are slightly lower than those reported previously (∼200 and 170 μm, respectively, Von Oertzen, 1972; Oliver et al., 1980; see Supplementary Table 4), likely representing different stages of maturity, and are consistent with the current understanding of reproduction in these species. Both species have egg sizes which suggest direct development or short pelagic development (i.e., lecithotrophic) (Ockelmann, 1965), and the small variation in oocyte frequency observed within treatments (Supplementary Figures 4, 5) are akin to continuous spawners with an overlying seasonal intensity in reproduction (Lau et al., 2018), or natural variations in reproductive fitness. However, the presence of eggs in the supra-branchial chamber in four specimens of A. crenata exposed to future conditions is indicative of brooding, a previously unreported reproductive trait that is also supported by the large egg sizes, and formally hypothesized by the presence of adherent eggs and observed internal fertilization within Astartidae (Ockelmann, 1958; Marina et al., 2020).

It is tempting to conclude that our findings indicate resilience of the reproductive stage examined to near-term climatic forcing, but our observations of the successful progression of gametogenesis took place under standard laboratory conditions which, following accepted protocols (e.g., Pansch et al., 2018), include a constant supply of food. This may have inadvertently provided a sufficient supply of energy to overcome the metabolic costs of environmental stress (Cominassi et al., 2020) and mitigated the impact on gametogenesis. Increasing temperature and carbon dioxide concentrations affect species physiology through increased metabolism (Parker et al., 2013; Jager et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2020), and sometimes the suppression of feeding (Stumpp et al., 2012; Kurihara et al., 2013; Appelhans et al., 2014), which directly affects per offspring investment (Moran and McAlister, 2009; Pettersen et al., 2019), and gamete behavior post spawning (Verkaik et al., 2016). Energy stored as gametes can also be reabsorbed and act as a trade-off with fecundity (Stumpp et al., 2012; Verkaik et al., 2017; Rossin et al., 2019). However, considerable physiological resilience to ocean acidification has been demonstrated at various life-cycle stages in bivalves (Dell’Acqua et al., 2019), echinoderms (Verkaik et al., 2017), and corals (Gizzi et al., 2017), and during short incubations, appears to show no significant effects on growth and reproduction in benthic invertebrates (Dell’Acqua et al., 2019), even in food limited scenarios (Goethel et al., 2017). Laboratory experiments have shown that higher food quality and availability has a role in buffering the physiological effects of climate change and ocean acidification (Asnaghi et al., 2013), with positive effects reported in Calanus copepods (Pedersen et al., 2014), bivalves (Thomsen et al., 2013), and barnacles (Pansch et al., 2014). Further, a recent study has demonstrated that ad libitum feeding mediated fish growth rates in ocean acidification and warming scenarios, and suggest that this standard method may not reliably detect the impacts of environmental change in laboratory experiments (Cominassi et al., 2020). In our study, the supply of sufficient and nutrient rich food, common to laboratory experiments, is likely to have moderated the effects of near-future carbon dioxide and temperature controls (Thomsen et al., 2013; Ramajo et al., 2016; Cominassi et al., 2020), and provided the necessary nutrients for successful gamete development. Nevertheless, the physiological fitness of a species and production of gametes does not imply their viability, successful development, or recruitment to the environment (Caroselli et al., 2019).

Environmental change does not only have a direct physical effect on species physiology (Pörtner and Farrell, 2008), but also changes the wider ecosystem, including food-web structures (Wassmann et al., 2006). In polar regions, the seasonal input of nutrient rich primary production originating from ice algae contributes an important seasonal input of organic matter to the benthos (Wassmann et al., 2011; Degen et al., 2016), impacting on biomass (Kêdra et al., 2013), growth (Blicher et al., 2010; Carroll et al., 2011a,b, 2014), benthic community physiology (Ambrose et al., 2006; Carroll and Peterson, 2013), and reproduction (Boetius et al., 2013). It has been consistently shown in polar environments that food has a greater impact on invertebrate physiology than temperature (Brockington and Clarke, 2001; Blicher et al., 2010), and can drive multi-decadal scale patterns in growth (Ambrose et al., 2006; Carroll et al., 2009) and recruitment (Skazina et al., 2013; Dayton et al., 2016). Associated with environmental forcing in the Arctic, there is expected to be a shift in the timings and quality of organic matter input to the benthos, from nutrient-rich ice algae to pelagic phytoplankton derived primary productivity (Arrigo and van Dijken, 2015), associated with thinner sea ice (Lange et al., 2019), and the transition to ice free conditions (Grebmeier et al., 2006; Leu et al., 2011; Polyakov et al., 2012a). Arctic phytoplankton assemblages may display resilience to ocean acidification through natural tolerances and intraspecific diversity (Hoppe et al., 2018), but the increasing unpredictability in quality of organic matter input impacts on the tight pelagic-benthic coupling which characterizes the Arctic (Tamelander et al., 2006; Wassmann et al., 2011; Kêdra et al., 2015). However, the observation that benthic species such as Astarte spp. and Bathyarca glacialis display feeding plasticity also ensures efficient use of available food input throughout the year (Gaillard et al., 2015; De Cesare et al., 2017), which may result in reproductive viability in otherwise unfavorable conditions.

Although gametogenesis may remain unaffected or mediated by food supply as a consequence of near future environmental change, the viability of fertilization and larval development under projected environmental conditions could still compromise successful recruitment (Dupont et al., 2010b; Kroeker et al., 2010; Albright, 2011). Fertilization across taxa has often shown negative responses to increasing carbon dioxide and temperature (e.g., Kurihara et al., 2007; Ericson et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2015; Graham et al., 2015), but results are not always consistent between species (Clark et al., 2009), populations (Thor et al., 2018), sexes (Verkaik et al., 2016), or individuals (Campbell et al., 2016; Boulais et al., 2017). Meanwhile “carry-over” effects and transgenerational plasticity may affect subsequent life cycle stages (Parker et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2019), shifting the development “bottleneck” to later stages, or forcing trade-offs with alternative reproductive traits such as fecundity or egg volume (Chakravarti et al., 2016). Larval development and early life history have also shown inconsistencies in their response to ocean acidification and increasing temperature. The Antarctic urchin Sterechinus neumayeri showed no differences in growth of reproductive tissue (Morley et al., 2016), or larval skeletal development (Clark et al., 2009) after exposure to ocean acidification and increased temperature, but a significant decrease in fertilization, developmental success, and increased developmental aberrations in alternative experiments have been recorded (Ericson et al., 2012; Byrne et al., 2013b). Larval type is also considered important, and planktotrophic larvae which are reliant on pelagic food are considered to be more susceptible than direct developing or non-feeding lecithotrophic larvae (Gutowska and Melzner, 2009; Dupont et al., 2010c; Gray et al., 2019). Consequently, biogeographical variations in larval responses to environmental change are likely to follow global and regional patterns of dominant larval types (Marshall et al., 2012). Here, both A. crenata and B. glacialis have oocyte sizes akin to non-feeding lecithotrophic or direct development (brooding) (Ockelmann, 1965) which is common in Polar species (Marshall et al., 2012), and suggests that food availability will have limited impact on larval development directly.

The lack of consistency between studies demonstrates the complex relationships between ocean acidification and temperature as synergistic stressors on individual reproductive performance (Byrne et al., 2013a; Harvey et al., 2013) and/or natural variations in tolerances within populations (Smith et al., 2019). Recruitment and recovery from disturbance in polar environments is often very slow (years – decades) (Barnes and Kukliński, 2005; Konar, 2013) although our knowledge of Arctic invertebrate reproductive biology remains limited (Kuklinski et al., 2013). The rapid rates of environmental change, however, may be further exacerbated by extreme longevity of organisms at high latitudes (Moss et al., 2016), To understand the effects of environmental change on reproductive ecology it will be important to consider all life history stages (Dupont et al., 2010a), and the role of population variability and plasticity as mechanisms of population resilience to environment change (Byrne et al., 2020). The role of changing food resources in determining reproductive viability in regions experiencing rapid change is presently under appreciated, but will be necessary to understand the links between the environment and reproductive/larval physiology (Goethel et al., 2017). The complex interactions between physiology, the environment, and climate change (Byrne et al., 2013a) will determine future population distributions and local extinction risks (Murdoch et al., 2020). We put forward, therefore, that holistic approaches including projected changes to regional food sources, are required to understand how future conditions may affect reproduction and modify interactions with whole animal physiological characteristics (Pörtner and Farrell, 2008; Dupont and Pörtner, 2013).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. All histology image data are to be made openly available from the Discovery Metadata System (https://www.bas.ac.uk/project/dms/), a data catalogue hosted by The UK Polar Data Centre (UK PDC, https://www.bas.ac.uk/data/uk-pdc/).

AR and LG conceived the idea. AR conducted the laboratory work and image analysis and wrote the manuscript. JG and AR analyzed the data and produced the figures. MS, LG, and JG reviewed and provided critical comments on the manuscript prior to submission. All of the authors have contributed to the manuscript.

This work was supported by “The Changing Arctic Ocean Seafloor (ChAOS) – how changing sea ice conditions impact biological communities, biogeochemical processes, and ecosystems” project (NE/N015894/1 and NE/P006426/1, 2017-2021) funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) in the United Kingdom.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank the crew of cruise JR16006 and JR17007, RRS James Clark Ross, Robbie Robinson (University of Southampton) for assistance with the design of our experimental systems, Tom Williams and Matthew Carpenter-Liquorice for maintaining the experiments, and National Marine Facilities, Southampton and the British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge for logistical support.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.576746/full#supplementary-material

Albright, R. (2011). Reviewing the effects of ocean acidification on sexual reproduction and early life history stages of reef-building corals. J. Mar. Biol. 2011, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2011/473615

Ambrose, W. G., Carroll, M. L., Greenacre, M., Thorrold, S. R., and McMahon, K. W. (2006). Variation in Serripes groenlandicus (Bivalvia) growth in a Norwegian high-Arctic fjord: evidence for local and large-scale climatic forcing. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 1595–1607.1.

Appelhans, Y. S., Thomsen, J., Opitz, S., Pansch, C., Melzner, F., and Wahl, M. (2014). Juvenile sea stars exposed to acidification decrease feeding and growth with no acclimation potential. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 509, 227–239.1.

Arrigo, K. R., and van Dijken, G. L. (2015). Continued increases in Arctic Ocean primary production. Prog. Oceanogr. 136, 60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2015.05.002

Asnaghi, V., Chiantore, M., Mangialajo, L., Gazeau, F., Francour, P., Alliouane, S., et al. (2013). Cascading effects of ocean acidification in a rocky subtidal community. PloS one 8:e61978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061978

Barnes, D. K. A., and Kukliński, P. (2005). Low colonisation on artificial substrata in arctic Spitsbergen. Polar Biol. 29, 65–69.1.

Blicher, M. E., Rysgaard, S., and Sejr, M. K. (2010). Seasonal growth variation in Chlamys islandica (Bivalvia) from sub-Arctic Greenland is linked to food availability and temperature. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 407, 71–86. doi: 10.3354/meps08536

Boetius, A., Albrecht, S., Bakker, K., Bienhold, C., Felden, J., Fernández-Méndez, M., et al. (2013). Export of algal biomass from the melting Arctic sea ice. Science 339, 1430–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.1231346

Boulais, M., Chenevert, K. J., Demey, A. T., Darrow, E. S., Robison, M. R., Roberts, J. P., et al. (2017). Oyster reproduction is compromised by acidification experienced seasonally in coastal regions. Sci. Rep. 7:13276.1.

Braun, D. C., Patterson, D. A., and Reynolds, J. D. (2013). Maternal and environmental influences on egg size and juvenile life-history traits in Pacific salmon. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1727–1740. doi: 10.1002/ece3.555

Brockington, S., and Clarke, A. (2001). The relative influence of temperature and food on the metabolism of a marine invertebrate. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 258, 87–99.1.

Byrne, M., Foo, S. A., Ross, P. M., and Putnam, H. M. (2020). Limitations of cross- and multigenerational plasticity for marine invertebrates faced with global climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 80–102.1.

Byrne, M., Gonzalez-Bernat, M., Doo, S., Foo, S., Soars, N., and Lamare, M. (2013a). Effects of ocean warming and acidification on embryos and non-calcifying larvae of the invasive sea star Patiriella regularis. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 473, 235–246. doi: 10.3354/meps10058

Byrne, M., and Hernández, J. C. (2020). “Chapter 16 - Sea urchins in a high CO2 world: Impacts of climate warming and ocean acidification across life history stages,” in Developments in Aquaculture and Fisheries Science, ed. J. M. Lawrence (New York, NY: Elsevier), 281–297. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-819570-3.00016-0

Byrne, M., Ho, M. A., Koleits, L., Price, C., King, C. K., Virtue, P., et al. (2013b). Vulnerability of the calcifying larval stage of the Antarctic sea urchin Sterechinus neumayeri to near-future ocean acidification and warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 2264–2275.1.

Campbell, A. L., Levitan, D. R., Hosken, D. J., and Lewis, C. (2016). Ocean acidification changes the male fitness landscape. Sci. Rep. 6:31250.1.

Caroselli, E., Gizzi, F., Prada, F., Marchini, C., Airi, V., Kaandorp, J., et al. (2019). Low and variable pH decreases recruitment efficiency in populations of a temperate coral naturally present at a CO2 vent. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 1059–1069. doi: 10.1002/lno.11097

Carr, R. S., Biedenbach, J. M., and Nipper, M. (2006). Influence of potentially confounding factors on sea urchin porewater toxicity tests. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 51, 573–579.1.

Carroll, J. M., and Peterson, B. J. (2013). Ecological trade-offs in seascape ecology: bay scallop survival and growth across a seagrass seascape. Landsc. Ecol. 28, 1401–1413.1.

Carroll, M. L., Ambrose, W. G., Levin, B. S., Locke, W. L., Henkes, G. A., Hop, H., et al. (2011a). Pan-Svalbard growth rate variability and environmental regulation in the Arctic bivalve Serripes groenlandicus. J. Mar. Syst. 88, 239–251.1.

Carroll, M. L., Ambrose, W. G., Levin, B. S., Ryan, S. K., Ratner, A. R., Henkes, G. A., et al. (2011b). Climatic regulation of Clinocardium ciliatum (bivalvia) growth in the northwestern Barents Sea. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 302, 10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.06.001

Carroll, M. L., Ambrose, W. G. Jr., Locke V, W. L., Ryan, S. K., and Johnson, B. J. (2014). Bivalve growth rate and isotopic variability across the Barents Sea Polar Front. J. Mar. Syst. 130, 167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2013.10.006

Carroll, M. L., Johnson, B. J., Henkes, G. A., McMahon, K. W., Voronkov, A., Ambrose, W. G., et al. (2009). Bivalves as indicators of environmental variation and potential anthropogenic impacts in the southern Barents Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 59, 193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.02.022

Chakravarti, L. J., Jarrold, M. D., Gibbin, E. M., Christen, F., Massamba-N’Siala, G., Blier, P. U., et al. (2016). Can trans-generational experiments be used to enhance species resilience to ocean warming and acidification? Evol. Appl. 9, 1133–1146.1.

Clark, D., Lamare, M., and Barker, M. (2009). Response of sea urchin pluteus larvae (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) to reduced seawater pH: a comparison among a tropical, temperate, and a polar species. Mar. Biol. 156, 1125–1137. doi: 10.1007/s00227-009-1155-8

Cochrane, S. K. J., Denisenko, S. G., Renaud, P. E., Emblow, C. S., Ambrose, W. G., Ellingsen, I. H., et al. (2009). Benthic macrofauna and productivity regimes in the Barents Sea — Ecological implications in a changing Arctic. J. Sea Res. 61, 222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2009.01.003

Cominassi, L., Moyano, M., Claireaux, G., Howald, S., Mark, F. C., Zambonino-Infante, J.-L., et al. (2020). Food availability modulates the combined effects of ocean acidification and warming on fish growth. Sci. Rep. 10:2338.

Dayton, P., Jarrell, S., Kim, S., Thrush, S., Hammerstrom, K., Slattery, M., et al. (2016). Surprising episodic recruitment and growth of Antarctic sponges: implications for ecological resilience. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 482, 38–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2016.05.001

De Cesare, S., Meziane, T., Chauvaud, L., Richard, J., Sejr, M. K., Thebault, J., et al. (2017). Dietary plasticity in the bivalve Astarte moerchi revealed by a multimarker study in two Arctic fjords. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 567, 157–172. doi: 10.3354/meps12035

Degen, R., Jørgensen, L. L., Ljubin, P. I, Ellingsen, H., Pehlke, H., and Brey, T. (2016). Patterns and drivers of megabenthic secondary production on the Barents Sea shelf. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 546, 1–16. doi: 10.3354/meps11662

Dell’Acqua, O., Ferrando, S., Chiantore, M., and Asnaghi, V. (2019). The impact of ocean acidification on the gonads of three key Antarctic benthic macroinvertebrates. Aquat. Toxicol. 210, 19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2019.02.012

Dickson, A. G. (1990). Standard potential of the reaction AgCl(s)+0.5H2 (g) = Ag(s) + HCl(aq) and the standard acidity constant of the ion HSO4—in synthetic sea water from 273.15 to 318.15 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 22, 113–127. doi: 10.1016/0021-9614(90)90074-Z

Dickson, A. G. (2010). “The carbon dioxide system in seawater: equilibrium chemistry and measurements,” in Guide to Best Practices for Ocean Acidification Research and Data Reporting, eds U. Riebesell, V. J. Fabry, L. Hansson, and J.-P. Gattuso (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union), 260.

Dickson, A. G., and Millero, F. J. (1987). A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep Sea Res. A 34, 1733–1743. doi: 10.1016/0198-0149(87)90021-5

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L., and Christian, J. R. (eds) (2007). Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements, Vol. 3. Sidney, BC: North Pacific Marine Science Organization, 191.

Dupont, S., Dorey, N., and Thorndyke, M. (2010a). What meta-analysis can tell us about vulnerability of marine biodiversity to ocean acidification? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 89, 182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2010.06.013

Dupont, S., Lundve, B., and Thorndyke, M. (2010c). Near Future Ocean Acidification Increases Growth Rate of the Lecithotrophic Larvae and Juveniles of the Sea Star Crossaster papposus. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 314, 382–389.1.

Dupont, S., Ortega-Martinez, O., and Thorndyke, M. (2010b). Impact of near-future ocean acidification on echinoderms. Ecotoxicology 19, 449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10646-010-0463-6

Ericson, J. A., Ho, M. A., Miskelly, A., King, C. K., Virtue, P., Tilbrook, B., et al. (2012). Combined effects of two ocean change stressors, warming and acidification, on fertilization and early development of the Antarctic echinoid Sterechinus neumayeri. Polar Biol. 35, 1027–1034. doi: 10.1007/s00300-011-1150-7

Foo, S. A., and Byrne, M. (2017). Marine gametes in a changing ocean: impacts of climate change stressors on fecundity and the egg. Mar. Environ. Res. 128, 12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2017.02.004

Gaillard, B., Meziane, T., Tremblay, R., Archambault, P., Layton, K., Martel, A., et al. (2015). Dietary tracers in Bathyarca glacialis from contrasting trophic regions in the Canadian Arctic. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 536, 175–186. doi: 10.3354/meps11424

Gibbin, E. M., Chakravarti, L. J., Jarrold, M. D., Christen, F., Turpin, V., and Massamba N’Siala, G. (2017). Can multi-generational exposure to ocean warming and acidification lead to the adaptation of life history and physiology in a marine metazoan? J. Exp. Biol. 220, 551–563. doi: 10.1242/jeb.149989

Gizzi, F., de Mas, L., Airi, V., Caroselli, E., Prada, F., Falini, G., et al. (2017). Reproduction of an azooxanthellate coral is unaffected by ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 7:13049.

Godbold, J. A., and Solan, M. (2013). Long-term effects of warming and ocean acidification are modified by seasonal variation in species responses and environmental conditions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc.Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368:20130186. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0186

Goethel, C. L., Grebmeier, J. M., Cooper, L. W., and Miller, T. J. (2017). Implications of ocean acidification in the Pacific Arctic: experimental responses of three Arctic bivalves to decreased pH and food availability. Deep Sea Res. 2 Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 144, 112–124.1.

Graham, H., Rastrick, S. P. S., Findlay, H. S., Bentley, M. G., Widdicombe, S., Clare, A. S., et al. (2015). Sperm motility and fertilisation success in an acidified and hypoxic environment. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 783–790. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv171

Gray, M. W., Chaparro, O., Huebert, K. B., O’Neill, S. P., Couture, T., Moreira, A., et al. (2019). Life history traits conferring larval resistance against ocean acidification: the case of brooding oysters of the genus Ostrea. J. Shellfish Res. 38, 751–761. doi: 10.2983/035.038.0326

Grebmeier, J. M., Overland, J. E., Moore, S. E., Farley, E. V., Carmack, E. C., Cooper, L. W., et al. (2006). A major ecosystem shift in the Northern Bering Sea. Science 311, 1461–1464. doi: 10.1126/science.1121365

Guo, X., Huang, M., Pu, F., You, W., and Ke, C. (2015). Effects of ocean acidification caused by rising CO2 on the early development of three mollusks. Aqua. Biol. 23, 147–157. doi: 10.3354/ab00615

Gutowska, M. A., and Melzner, F. (2009). Abiotic conditions in cephalopod (Sepia officinalis) eggs: embryonic development at low pH and high pCO2. Mar. Biol. 156, 515–519.1.

Harvey, B. P., Gwynn-Jones, D., and Moore, P. J. (2013). Meta-analysis reveals complex marine biological responses to the interactive effects of ocean acidification and warming. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1016–1030. doi: 10.1002/ece3.516

Hendriks, I. E., and Duarte, C. M. (2010). Ocean acidification: separating evidence from judgment – a reply to Dupont et al. Estuar. Coastal Shelf Sci. 89, 186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2010.06.007

Higgs, N. D., Reed, A. J., Hooke, R., Honey, D. J., Heilmayer, O., and Thatje, S. (2009). Growth and reproduction in the Antarctic brooding bivalve Adacnarca nitens (Philobryidae) from the Ross Sea. Mar. Biol. 156, 1073–1081.1.

Hoppe, C. J. M., Wolf, K. K. E., Schuback, N., Tortell, P. D., and Rost, B. (2018). Compensation of ocean acidification effects in Arctic phytoplankton assemblages. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 529–533. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0142-9

IPCC (2013). “Summary for policymakers,” in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Jager, T., Ravagnan, E., and Dupont, S. (2016). Near-future ocean acidification impacts maintenance costs in sea-urchin larvae: identification of stress factors and tipping points using a DEB modelling approach. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 474, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2015.09.016

Jokiel, P. L., Rodgers, K. S., Kuffner, I. B., Andersson, A. J., Cox, E. F., and Mackenzie, F. T. (2008). Ocean acidification and calcifying reef organisms: a mesocosm investigation. Coral Reefs 27, 473–483.1.

Karelitz, S., Lamare, M. D., Mos, B., De Bari, H., Dworjanyn, S. A., and Byrne, M. (2019). Impact of growing up in a warmer, lower pH future on offspring performance: transgenerational plasticity in a pan-tropical sea urchin. Coral Reefs 38, 1085–1095. doi: 10.1007/s00338-019-01855-z

Kêdra, M., Moritz, C., Choy, E. S., David, C., Degen, R., Duerksen, S., et al. (2015). Status and trends in the structure of Arctic benthic food webs. Polar Res. 34:23775. doi: 10.3402/polar.v34.23775

Kêdra, M., Renaud, P. E., Andrade, H., Goszczko, I., and Ambrose, W. G. (2013). Benthic community structure, diversity, and productivity in the shallow Barents Sea bank (Svalbard Bank). Mar. Biol. 160, 805–819.1.

Konar, B. (2013). Lack of recovery from disturbance in high-arctic boulder communities. Polar Biol. 36, 1205–1214.1.

Kong, H., Jiang, X., Clements, J. C., Wang, T., Huang, X., and Shang, Y. (2019). Transgenerational effects of short-term exposure to acidification and hypoxia on early developmental traits of the mussel Mytilus edulis. Mar. Environ. Res. 145, 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2019.02.011

Kroeker, K. J., Kordas, R. L., Crim, R. N., and Singh, G. G. (2010). Meta−analysis reveals negative yet variable effects of ocean acidification on marine organisms. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1419–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01518.x

Kuklinski, P., Berge, J., McFadden, L., Dmoch, K., Zajaczkowski, M., Nygård, H., et al. (2013). Seasonality of occurrence and recruitment of Arctic marine benthic invertebrate larvae in relation to environmental variables. Polar Biol. 36, 549–560. doi: 10.1007/s00300-012-1283-3

Kurihara, H., Kato, S., and Ishimatsu, A. (2007). Effects of increased seawater pCO(2) on early development of the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Aqua. Biol. 1, 91–98. doi: 10.3354/ab00009

Kurihara, H., Yin, R., Nishihara, G. N., Soyano, K., and Ishimatsu, A. (2013). Effect of ocean acidification on growth, gonad development and physiology of the sea urchin Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus. Aqua. Biol. 18, 281–292. doi: 10.3354/ab00510

Lange, B. A., Haas, C., Charette, J., Katlein, C., Campbell, K., Duerksen, S., et al. (2019). Contrasting ice algae and snow−dependent irradiance relationships between first−year and multiyear sea ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10834–10843. doi: 10.1029/2019gl082873

Lau, S. C. Y., Grange, L. J., Peck, L. S., and Reed, A. J. (2018). The reproductive ecology of the Antarctic bivalve Aequiyoldia eightsii (Protobranchia: Sareptidae) follows neither Antarctic nor taxonomic patterns. Polar Biol. 41, 1693–1706.1.

Leu, E., Søreide, J., Hessen, D., Falk-Petersen, S., and Berge, J. (2011). Consequences of changing sea-ice cover for primary and secondary producers in the European Arctic shelf seas: timing, quantity, and quality. Prog. Oceanogr. 90, 18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2011.02.004

Leung, J. Y. S., Russell, B. D., and Connell, S. D. (2020). Linking energy budget to physiological adaptation: how a calcifying gastropod adjusts or succumbs to ocean acidification and warming. Sci. Total Environ. 715:136939. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136939

Marina, P., Urra, J., de Dios Bueno, J., Rueda, J. L., Gofas, S., and Salas, C. (2020). Spermcast mating with release of zygotes in the small dioecious bivalve Digitaria digitaria. Sci. Rep. 10:12605.

Marshall, D. J., Krug, P. J., Kupriyanova, E. K., Byrne, M., and Emlet, R. B. (2012). The biogeography of marine invertebrate life histories. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 43, 97–114. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145004

Mehrbach, C., Culberson, C., Hawley, J., and Pytkowicx, R. (1973). Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure 1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 18, 897–907. doi: 10.4319/lo.1973.18.6.0897

Miller, G. H., Alley, R. B., Brigham-Grette, J., Fitzpatrick, J. J., Polyak, L., Serreze, M. C., et al. (2010). Arctic amplification: can the past constrain the future? Quater. Sci. Rev. 29, 1779–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.02.008

Moran, A., Harasewych, M., Miller, B., Woods, H., Tobalske, B., and Marko, P. (2019). Extraordinarily long development of the Antarctic gastropod Antarctodomus thielei (Neogastropoda: Buccinoidea). J. Molluscan Stud. 85, 319–326. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eyz015

Moran, A. L., and McAlister, J. S. (2009). Egg size as a life history character of marine invertebrates: is it all it’s cracked up to be? Biol. Bull. 216, 226–242.1.

Morley, S. A., Suckling, C. C., Clark, M. S., Cross, E. L., and Peck, L. S. (2016). Long-term effects of altered pH and temperature on the feeding energetics of the Antarctic sea urchin Sterechinus neumayeri. Biodiversity 17, 34–45.1.

Moss, D. K., Ivany, L. C., Judd, E. J., Cummings, P. W., Bearden, C. E., Kim, W. J., et al. (2016). Lifespan, growth rate, and body size across latitude in marine Bivalvia, with implications for Phanerozoic evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283:7.

Murdoch, A., Mantyka-Pringle, C., and Sharma, S. (2020). The interactive effects of climate change and land use on boreal stream fish communities. Sci. Total Environ. 700:134518. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134518

Nelson, G. A. (2019). Package “Fish Methods”: Fishery Science Methods and Models. Version 11.1-1. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/fishmethods/fishmethods.pdf (accessed January, 2020).

Ockelmann, K. W. (1965). “Developmental types in marine bivalves and their distribution along the Atlantic coast of Europe,” in Proceedings of the 1st European Malacological Congress, 1962, eds L. R. Cox and J. Peake (London: Conchological Society of Great Britain & Ireland), 25–35.

Oliver, G., Allen, J. A., and Yonge, M. (1980). The functional and adaptive morphology of the deep-sea species of the Arcacea (Mollusca: Bivalvia) from the Atlantic. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 291, 45–76. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0127

Pansch, C., Hattich, G. S. I., Heinrichs, M. E., Pansch, A., Zagrodzka, Z., and Havenhand, J. N. (2018). Long-term exposure to acidification disrupts reproduction in a marine invertebrate. PLoS One 13:e0192036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192036

Pansch, C., Schaub, I., Havenhand, J., and Wahl, M. (2014). Habitat traits and food availability determine the response of marine invertebrates to ocean acidification. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 765–777.1.

Parker, L. M., O’Connor, W. A., Byrne, M., Coleman, R. A., Virtue, P., Dove, M., et al. (2017). Adult exposure to ocean acidification is maladaptive for larvae of the Sydney rock oyster Saccostrea glomerata in the presence of multiple stressors. Biol. Lett 13:20160798. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0798

Parker, L. M., Ross, P. M., and O’Connor, W. A. (2011). Populations of the Sydney rock oyster, Saccostrea glomerata, vary in response to ocean acidification. Mar. Biol. 158, 689–697.1.

Parker, L. M., Ross, P. M., O’Connor, W. A., Pörtner, H. O., Scanes, E., and Wright, J. M. (2013). Predicting the response of molluscs to the impact of ocean acidification. Biology 2, 651–692.1.

Peck, L. S. (2016). A cold limit to adaptation in the Sea. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.014

Pedersen, S. A., Haåkedal, O. J., Salaberria, I., Tagliati, A., Gustavson, L. M., Jenssen, B. M., et al. (2014). Multigenerational exposure to ocean acidification during food limitation reveals consequences for copepod scope for growth and vital rates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 12275–12284. doi: 10.1021/es501581j

Pettersen, A. K., White, C. R., Bryson-Richardson, R. J., and Marshall, D. J. (2019). Linking life-history theory and metabolic theory explains the offspring size-temperature relationship. Ecol. Lett. 22, 518–526.1.

Polyakov, I. V., Pnyushkov, A. V., and Timokhov, L. A. (2012b). Warming of the intermediate Atlantic water of the Arctic Ocean in the 2000s. J. Clim. 25, 8362–8370. doi: 10.1175/jcli-d-12-00266.1

Polyakov, I. V., Walsh, J. E., and Kwok, R. (2012a). Recent changes of Arctic multiyear sea ice coverage and the likely causes. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 145–151. doi: 10.1175/bams-d-11-00070.1

Przeslawski, R., Byrne, M., and Mellin, C. (2015). A review and meta-analysis of the effects of multiple abiotic stressors on marine embryos and larvae. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 2122–2140.1.

Qi, D., Chen, L., Chen, B., Gao, Z., Zhong, W., Feely, R. A., et al. (2017). Increase in acidifying water in the western Arctic Ocean. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 195–199. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3228

R Core Team (2018). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: RFoundation for Statistical Computing.

Ramajo, L., Pérez-León, E., Hendriks, I. E., Marbà, N., Krause-Jensen, D., Sejr, M. K., et al. (2016). Food supply confers calcifiers resistance to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 6:19374.

Reed, A. J., Morris, J. P., Linse, K., and Thatje, S. (2014). Reproductive morphology of the deep-sea protobranch bivalves Yoldiella ecaudata, Yoldiella sabrina, and Yoldiella valettei (Yoldiidae) from the Southern Ocean. Polar Biol. 37, 1383–1392. doi: 10.1007/s00300-014-1528-4

Richard, J., Morley, S. A., Deloffre, J., and Peck, L. S. (2012). Thermal acclimation capacity for four Arctic marine benthic species. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 424, 38–43.1.

Robbins, L. L., Hansen, M. E., Kleypas, J. A., and Meylan, S. C. (2010). CO2calc—A User-Friendly Seawater Carbon Calculator for Windows, Max OS X, and iOS (iPhone). US Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010–1280. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, 17.

Ross, P. M., Parker, L., O’Connor, W. A., and Bailey, E. A. (2011). The impact of ocean acidification on reproduction, early development and settlement of marine organisms. Water 3, 1005–1030. doi: 10.3390/w3041005

Rossin, A. M., Waller, R. G., and Stone, R. P. (2019). The effects of in-vitro pH decrease on the gametogenesis of the red tree coral, Primnoa pacifica. PLoS One 14:e0203976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203976

Saleuddin, A. (1965). The mode of life and functional anatomy of Astarte spp. (Eulamellibranchia). J. Molluscan Stud. 36, 229–257.

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., and Eliceiri, K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675.1.

Skazina, M., Sofronova, E., and Khaitov, V. (2013). Paving the way for the new generations: Astarte borealis population dynamics in the White Sea. Hydrobiologia 706, 35–49. doi: 10.1007/s10750-012-1271-1

Smith, K. E., Byrne, M., Deaker, D., Hird, C. M., Nielson, C., Wilson-McNeal, A., et al. (2019). Sea urchin reproductive performance in a changing ocean: poor males improve while good males worsen in response to ocean acidification. Proc. R. Soc. B 286:20190785. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0785

Solan, M., Ward, E. R., Wood, C. L., Reed, A. J., Grange, L. J., and Godbold, J. A. (2020). Climate driven benthic invertebrate activity and biogeochemical functioning across the Barents Sea Polar Front. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 378:20190365. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2019.0365

Spalding, C., Finnegan, S., and Fischer, W. W. (2017). Energetic costs of calcification under ocean acidification. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 866–877. doi: 10.1002/2016gb005597

Stumpp, M., Trübenbach, K., Brennecke, D., Hu, M. Y., and Melzner, F. (2012). Resource allocation and extracellular acid–base status in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis in response to CO2 induced seawater acidification. Aqua. Toxicol. 110-111, 194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.12.020

Suckling, C. C., Clark, M. S., Richard, J., Morley, S. A., Thorne, M. A. S., Harper, E. M., et al. (2015). Adult acclimation to combined temperature and pH stressors significantly enhances reproductive outcomes compared to short-term exposures. J. Anim. Ecol. 84, 773–784.1.

Tamelander, T., Renaud, P. E., Hop, H., Carroll, M. L., Ambrose, W. G. Jr., and Hobson, K. A. (2006). Trophic relationships and pelagic–benthic coupling during summer in the Barents Sea Marginal Ice Zone, revealed by stable carbon and nitrogen isotope measurements. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 310, 33–46. doi: 10.3354/meps310033

Thomsen, J., Casties, I., Pansch, C., Körtzinger, A., and Melzner, F. (2013). Food availability outweighs ocean acidification effects in juvenile Mytilus edulis: laboratory and field experiments. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 1017–1027.1.

Thor, P., and Dupont, S. (2015). Transgenerational effects alleviate severe fecundity loss during ocean acidification in a ubiquitous planktonic copepod. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 2261–2271. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12815

Thor, P., Vermandele, F., Carignan, M. H., Jacque, S., and Calosi, P. (2018). No maternal or direct effects of ocean acidification on egg hatching in the Arctic copepod Calanus glacialis. PLoS One 13:e0192496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192496

Uthicke, S., Pecorino, D., Albright, R., Negri, A. P., Cantin, N., and Liddy, M. (2013). Impacts of ocean acidification on early life-history stages and settlement of the coral-eating sea star Acanthaster planci. PLoS One 8:e82938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082938

Verkaik, K., Hamel, J. F., and Mercier, A. (2016). Carry-over effects of ocean acidification in a cold-water lecithotrophic holothuroid. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 557, 189–206. doi: 10.3354/meps11868

Verkaik, K., Hamel, J.-F., and Mercier, A. (2017). Impact of ocean acidification on reproductive output in the deep-sea annelid Ophryotrocha sp. (Polychaeta: Dorvilleidae). Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 137, 368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2016.05.022

Von Oertzen, J. A. (1972). Cycles and rates of reproduction of six Baltic Sea bivalves of different zoogeographical origin. Mar. Biol. 14, 143–149. doi: 10.1007/bf00373213

Wassmann, P., Duarte, C. M., Agusti, S., and Sejr, M. K. (2011). Footprints of climate change in the Arctic marine ecosystem. Glob. Chang. Biol. 17, 1235–1249.1.

Wassmann, P., Reigstad, M., Haug, T., Rudels, B., Carroll, M., Hop, H., et al. (2006). Food webs and carbon flux in the Barents Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 71, 232–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2006.10.003

Keywords: metabolic plasticity, functional response, oogenesis, life-history, dynamic energy-budget

Citation: Reed AJ, Godbold JA, Solan M and Grange LJ (2021) Invariant Gametogenic Response of Dominant Infaunal Bivalves From the Arctic Under Ambient and Near-Future Climate Change Conditions. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:576746. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.576746

Received: 26 June 2020; Accepted: 01 February 2021;

Published: 25 February 2021.

Edited by:

Rui Rosa, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Rejean Tremblay, Université du Québec à Rimouski, CanadaCopyright © 2021 Reed, Godbold, Solan and Grange. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adam J. Reed, YWRhbS5yZWVkQG5vYy5zb3Rvbi5hYy51aw==

†ORCID: Adam J. Reed, orcid.org/0000-0003-2200-5067; Jasmin A. Godbold, orcid.org/0000-0001-5558-8188; Martin Solan, orcid.org/0000-0001-9924-5574; Laura J. Grange, orcid.org/0000-0001-9222-6848

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.