- 1Department of Marine and Coastal Environmental Science, Texas A&M University Galveston Campus, Galveston, TX, United States

- 2Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

Microorganisms produce soluble low-molecular-weight (LMW, <1 kDa) siderophores, one of the strongest Fe-binding agents, to respond to the scarcity of Fe in the ocean. The presence of siderophores in marine particles/colloids is mostly not considered. Here, experimental evidence is provided to suggest the possibility of siderophore incorporation into marine particles. An incubation experiment with a 59Fe-complexed desferrioxamine (DFO, siderophore-model compound) was conducted using natural seawater (<3 μm) at dark condition to examine the size re-distribution of DFO and its associated Fe during microbial growth. 59Fe and DFO in suspended particles/aggregates, colloids and dissolved phase were quantified after the incubation. Our results showed that ∼55% of the 59Fe, originally in the form of LMW DFO-Fe, was incorporated in the suspended particles/aggregates. Noticeably, a minor amount (0.395 ± 0.020%) of the DFO was incorporated into the particulate phase. This finding is novel in that while the DFO facilitating Fe incorporation into microbial biomass was released back into the dissolved phase, still a minor fraction of the siderophores could be “retained” in particles. This could have become cumulatively more important in more complex natural systems that involves the interplay between minerals, bacteria, phytoplankton and zooplankton. Furthermore, our results indirectly suggest a balance of two different mechanisms during the Fe-siderophore transport. Our results are in favor of the processes occurring outside of the cells (Fe dissociation from the Fe-siderophore complex followed by the microbial Fe uptake) but the second mechanism can also exist (uptake of intact Fe-siderophore complex into the microbial intracellular fractions), albeit to a lesser extent.

Introduction

Dissolved Fe (dFe) concentrations are at trace levels (≤1.0 nM) in the ocean compared to particulate Fe which consist of 74–99% of the total Fe pool (Boyd et al., 2010; Lam et al., 2012; Buck et al., 2015) although dFe concentration can be higher than 1.0 nM in deeper ocean (Bennett et al., 2008; Nishioka et al., 2013). This low dFe concentration can limit microalgal productivity (Quigg, 2016) by as much as 30–40% in the upper water column of oceans, particularly in high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll (HNLC) regions (Boyé et al., 2001; Moore et al., 2013; Fitzsimmons et al., 2016; Nishioka and Obata, 2017). In response to the scarcity of Fe, microorganisms produce a variety of Fe-binding ligands, e.g., siderophores, that create highly soluble forms of dFe by chelation that are then transformed to bioavailable Fe through microbial enzymatic solubilization reactions (Morel and Price, 2003; Gledhill and Buck, 2012; Hassler et al., 2015). As a consequence, essentially ≥99% of dFe in the ocean is complexed by naturally occurring organic ligands, of which some have been characterized as siderophores (Butler, 2005; Mawji et al., 2008; Boiteau et al., 2016, 2019; Bundy et al., 2018; Yarimizu et al., 2019).

Siderophores are typically multidentate, oxygen-donor ligands that include hydroxamate, catecholate, or α-hydroxy-carboxylate types, produced by microorganisms. Overall stability constants range from 16 to 62 (in terms of log, Boukhalfa and Crumbliss, 2002) at 25°C for complexation of Fe(H2O)63+ by the fully deprotonated ligand of hydroxamates showing a strong denticity effect on the redox potential, that enhances the stability of Fe(III) toward reduction. The presence of siderophores have been widely demonstrated to be ubiquitous in the ocean, regardless of the Fe status (Kraemer et al., 2005; Mawji et al., 2008; Ibisanmi et al., 2011; Gledhill and Buck, 2012). Most importantly, siderophore compounds are commonly detected only at low-molecular-weight (LMW, typically <1 kDa or 3 kDa) range in the ocean (Macrellis et al., 2001; Mawji et al., 2011), and the presence of siderophores in high-molecular-weight (HMW) range [i.e., marine particles (>0.4 μm)/colloids (1 kDa/3 kDa–0.4 μm)] are usually not considered or not measured in field work, due to the difficulty and high requirement in experimental condition to directly measure the particulate siderophore. Nevertheless, few studies (Chuang et al., 2013; Velasquez et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2020) have detected the presence of siderophore compounds in concentrated marine particles (e.g., sinking particles in sediment trap and marine colloids after natural seawater being concentrated by >100 times with ultrafiltration technique), implying the potential incorporation of siderophore into marine particles in the water column. However, direct evidence for this incorporation is still insufficient, while it can provide new insights into the transport and cycling of Fe in the ocean.

To examine the possible size re-distribution of originally LMW siderophore compounds during the microbial growth in seawater, as well as the transport of siderophore-complexed Fe, 59Fe was initially complexed with an hydroxamate siderophore model compound, followed by laboratory microbial incubation in filtered natural seawater. After the incubation, the partitioning of both 59Fe and siderophore model compound among dissolved, colloidal and particulate phases was determined. The main goal of the present study is to provide direct evidence for the partitioning of siderophore into marine particles using controlled laboratory experiments since observations for the existence of particulate siderophores in field samples from marine environments are still limited. The experimental data is further used to provide indirect evidence for the mechanisms responsible for the observed partitioning of Fe and siderophore in seawater. Furthermore, it can also provide new insights into the sources of the organic Fe- and other Fe-like trace metal-binding ligands in the particles that sink into the deep ocean.

Materials and Methods

Natural Seawater Culturing With Radiolabeled Siderophore

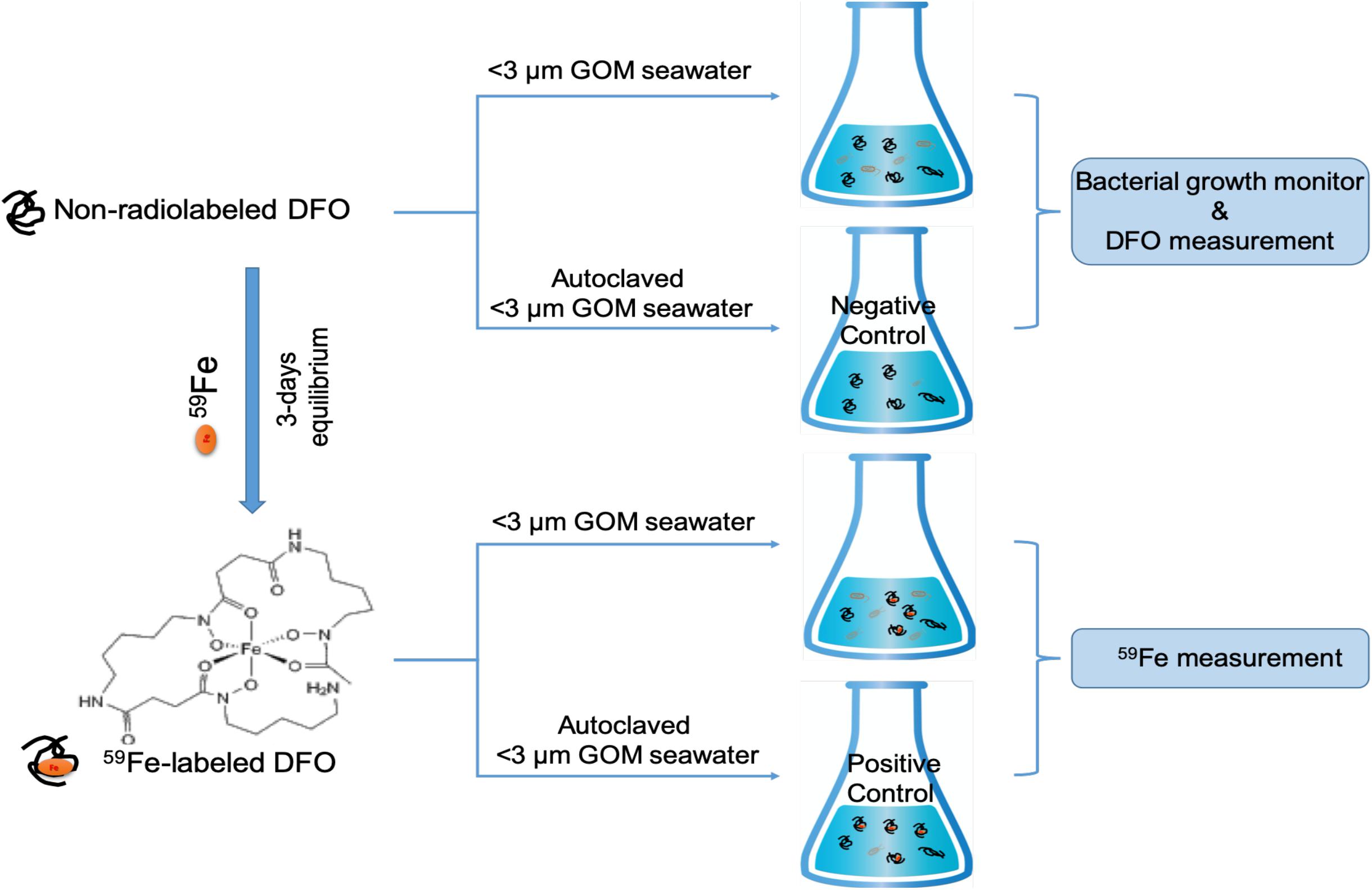

The incubation procedure, basically based on the procedure described in Xu et al. (2011), and culturing medium are briefly shown in Figure 1. Natural seawater was collected from the northern Gulf of Mexico (5 m of water depth, pH = 8.0, Salinity = 35, collected at NOAA center of Galveston island, TX, United States). The Northern Gulf of Mexico connects with more than 16 major estuarine systems and a number of smaller ones, with consistent river discharge and terrestrial inputs of nutrients and trace metals. Our seawater sampling location is close to the coastal areas and may not be a Fe-limited system, with certain abundance of nutrients (e.g., dissolved inorganic nitrogen of 10 μM and phosphate of 1.4 μM, Xu et al., unpublished data). For the culturing medium, this GOM seawater was filtered through 3 μm polycarbonate filters (Millipore) to remove most of the phytoplankton and their attached bacteria. Most of the free bacteria will stay in the <3 μm seawater filtrate, which was then used for the incubation experiment at the same day of sampling and filtration.

Figure 1. Brief procedure schematic for the incubation of Fe-DFO complex in northern Gulf of Mexico seawater. <3 μm GOM seawater and autoclaved <3 μm GOM seawater [i.e., “negative” control (without 59Fe) and “positive” control (with 59Fe)] are both amended with carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus sources in a Redfield ratio (i.e., 70.76 μM glucose, 64 μM NH4Cl, and 3.6 μM NaH2PO4).

For incubation, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus sources were added into the natural seawater in a Redfield ratio for the culturing medium (i.e., 70.76 μM glucose, 64 μM NH4Cl and 3.6 μM NaH2PO4, in ACS grade, Sigma-Aldrich). Prior to the culturing, the 59Fe-labeled siderophore was first prepared by a reaction of 59Fe (present in the form of 59FeCl3 in carrier free solution, PerkinElmer) with a siderophore model compound (desferrioxamine, DFO, ≥92.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) in ultrapure water for 3 days. Since DFO was amended at μM levels (1 μM), much higher than the chemical concentrations of 59Fe (2 fM), we can safely assume that all the 59Fe was complexed with DFO based on the high overall stability constant value of Fe-DFO complex (30.7 at 25°C in terms of log, Boukhalfa and Crumbliss, 2002).

59Fe-complexed DFO was then added to the seawater and incubated on a shaker at 150 rpm. All experiments were conducted in duplicate and in trace-metal-clean and dark condition at room temperature. One non-radiolabeled sample group was also included in the experiment, with the addition of non-radiolabeled DFO to determine the partitioning of DFO after the incubation. These non-radiolabeled samples were also used for monitoring the growth status of bacteria in the culture, measured as the change in optical density at 600 nm wavelength (OD600) with a UV-Vis spectrometer (Xu et al., 2011). It should be also mentioned here that in addition to free bacteria, 3 μm-filtered seawater can still contain small phytoplankton and mineral particles, which could contribute to the Fe and DFO partitioning, although the activity of small phytoplankton is limited due to the dark incubation condition.

In addition to the different treatments in this experiment, control samples were also included. Filtered GOM seawater (<3 μm) but autoclaved prior to the experiment was treated in the same way as the other treatment mentioned above: one with the addition of 59Fe-DFO (“positive” control, Figure 1) and another one with the addition of non-radiolabeled DFO (“negative” control, Figure 1) to monitor any potential influence of other particulate/colloidal sources (e.g., air dust) and abiotic scavenging on the partitioning of 59Fe and DFO.

After reaching the exponential phase (usually less than 1 week), the culture samples were filtered by 0.45 μm polycarbonate filters (Millipore) to quantify the incorporation of 59Fe and DFO into suspended particles/aggregates. Furthermore, the filtrate was further ultrafiltered using 3 kDa Microsep centrifugal filter tubes (Millipore) to collect the colloidal and dissolved (<3 kDa) phases. Therefore, the partitioning of 59Fe among particulate, colloidal and dissolved phases after incubation can be quantified through the gamma counting of the 59Fe activity using a Canberra ultra-high purity germanium well-type detector at 1099 keV. The samples were counted for enough time to obtain counting errors lower than 5%. The partitioning of Fe was presented in terms of 59Fe activity percentage in different phases, i.e., particulate/colloidal/dissolved 59Fe activity concentration divided by the total 59Fe activity concentrations (sum of particulate, colloidal and dissolved 59Fe activity concentrations).

Measurement of Hydroxamate Siderophore

The non-radiolabeled culture was also filtered and ultrafiltered for the measurement of size-fractionated DFO concentrations, using a modified “Csaky” method (Gillam et al., 1981; Xu et al., 2015, 2020). For the measurement of DFO in particulate phases, the suspended particles/aggregates were pretreated overnight with 5 mL of 10% HF on an orbital shaker at room temperature. After centrifugation to separate the HF from the sample, the pellet was thoroughly rinsed with 1 M HCl to eliminate any residual HF. The above extractant from suspended particles/aggregates, as well as colloidal and dissolved samples, were hydrolyzed by 1 mL of 3 M H2SO4 at 100°C for 4 h, with a hydrolysis rate of 20% for DFO (Xu et al., unpublished data). Two aliquots of the hydrolyzed solution were transferred into two screw capped glass test tubes, including one as a sample and the other one as a control to correct for interferences contributed by other organic compounds to the absorbance. After the addition of color producing reagent (α-naphthylamine, 0.05% wt/vol, and Sigma-Aldrich) and allowing the samples to stand for 18 h at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 543 nm with a UV-Vis spectrometer (BioTek Epoch Plate Reader). Acetohydroxamic acid (AHA, ≥98%, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the calibration standard. Our modified Csaky method has a detection limit of 1.5 μg-AHA equivalent/g-particles, with a precision better than 10% (Xu et al., 2015). It should be mentioned that we noticed a “browning” effect of this method when analyzing natural particle samples, likely caused by interactions with H2SO4 (Xu et al., 2020). This “browning” effect can then be corrected by subtracting the absorbance of a control sample aliquot without the addition of the coloring reagent. All the acids used above are in ACS grade, from Fisher Scientific.

Results

Size Distribution of Fe in the Culture

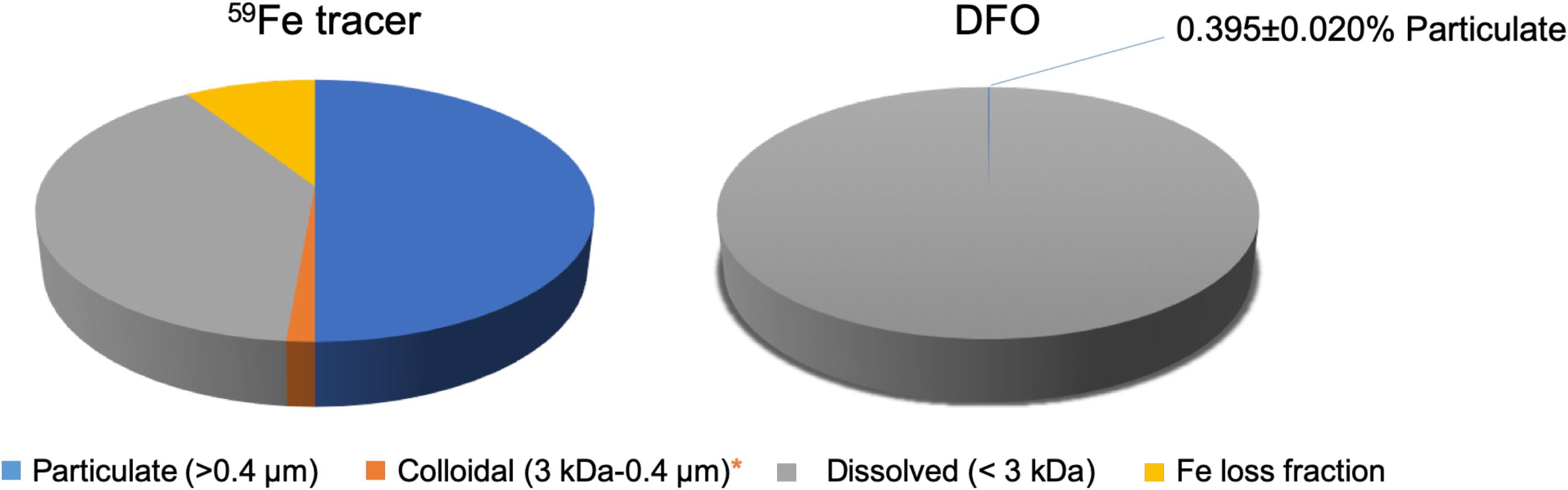

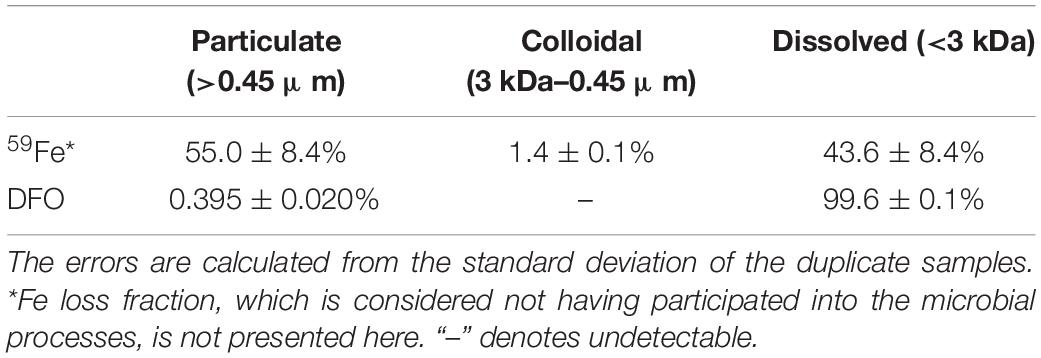

The mass balance of 59Fe in control samples and treatment samples was determined to assess possible losses during the incubation, e.g., wall effects. In general, the total recovery of 59Fe were all close to 90% (Figure 2), indicating that only minor losses of 59Fe during the incubation experiments. The losses of 59Fe were considered not being participated into the microbial growth in the present study since the adsorption losses of metals are usually irreversible under neutral conditions.

Figure 2. Partitioning of 59Fe (left) and DFO (right) among suspended particles/aggregates (0.45 μm), colloids (3 kDa–0.45 μm), and dissolved phase (<3 kDa) after the incubation in northern Gulf of Mexico seawater. Fe loss fraction (∼10%) is presented here, calculated from the difference between the total added 59Fe concentration and the sum of particulate-colloidal-dissolved 59Fe concentrations, which is considered not having participated into the microbial processes. *DFO is undetectable in the colloidal phase and only 1.4% of the total 59Fe was observed in the colloidal phase.

The partitioning of 59Fe among particulate, colloidal and dissolved phases after the incubation is shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. In contrast to the “positive” control samples (i.e., without particles/biomass in autoclaved seawater, Figure 1) showing all the 59Fe was detected in the dissolved phase, 55.0 ± 8.4% of the 59Fe was incorporated into the suspended particles/aggregates after the incubation (Table 1). Only 1.4 ± 0.1% of the 59Fe was found to be partitioned into the colloidal phase, leaving 43.6 ± 8.4% of the 59Fe in the dissolved fraction (Table 1). The significant difference between control (i.e., without microbes presence) and treatment samples demonstrated that the observed size partitioning of 59Fe was only resulted from the microbial processes in natural seawater, while the potential influence of other particulate/colloidal sources (e.g., air dust) and abiotic scavenging can be negligible, based on 100% of 59Fe remaining in the LMW dissolved phase for the control sample.

Table 1. Partitioning of 59Fe and DFO among suspended particles/aggregates (0.45 μm), colloids (3–0.45 μm), and dissolved phase (<3 kDa) after the incubation in northern Gulf of Mexico seawater.

Partitioning of Hydroxamate Siderophore in the Culture

Similar to the 59Fe, all the DFO in the “negative” control samples (Figure 1) was also observed to be only present in the LMW dissolved phases, suggesting that an abiotic process for DFO partitioning is minimal in our experiment. However, even though the 59Fe and DFO were originally present as a chelate before the incubation, our results showed distinctly different size distribution between 59Fe and DFO after the microbial growth. The mass balance of DFO in the treatment samples was close to 100%, with most of the DFO remaining in the LMW dissolved fractions (>99%) and leaving only 0.395% (±0.020%) of the DFO in the particulate phases after the incubation (Table 1), and undetectable DFO in the colloidal phase (Figure 2). Such a significant difference in microbial-derived size partitioning between 59Fe and DFO (55% vs. ∼0.4% in the particulate phase, Figure 2) is interesting, as it demonstrates their distinct transport pathways during microbial uptake and the incorporation into the suspended particles/aggregates.

Discussion

Fe is one of the most important micronutrients for the microbial growth and primary production in the ocean (Quigg et al., 2011, 2016), with most of the Fe being associated with strong organic ligands. In the present study, the Fe participates into the microbial growth process in the form of LMW Fe-siderophore complexes, one of the strongest Fe organic ligand compound in aquatic environments (Macrellis et al., 2001; Vong et al., 2007; Gledhill and Buck, 2012). Our observed incorporation of Fe into particulate phases (i.e., the Fe uptake by microbial) can be expected (Figure 2), consistent with the previous studies (e.g., Hutchins et al., 1999) showing the biological availability of the Fe-complexed siderophore to marine microbes (e.g., marine prokaryotes). Nevertheless, the DFO did not follow the size partitioning of Fe and their size partitioning had differed from each other after the incubation (Table 1 and Figure 2). This suggests that when Fe in the siderophore complexed form was transported from the dissolved to the particulate phase, most of the siderophore compound was released back into the LMW dissolved fraction after the siderophore compound finished its Fe-transport mission in the ocean. However, there still have been a minor amount of siderophore moieties that ended up in the particulate fraction. This observation of a minor amounts of siderophore compounds may partially explain why the field investigation in the ocean only detected siderophore compounds in the LMW fractions (Macrellis et al., 2001; Mawji et al., 2011), resulting in only scarce evidence for the presence of siderophore in marine particles. Concentrated marine particles, either from large volumes of natural seawater or from sediment traps (Chuang et al., 2013, 2015; Velasquez et al., 2016) are needed to detect the presence of particulate siderophore compounds in field sampling.

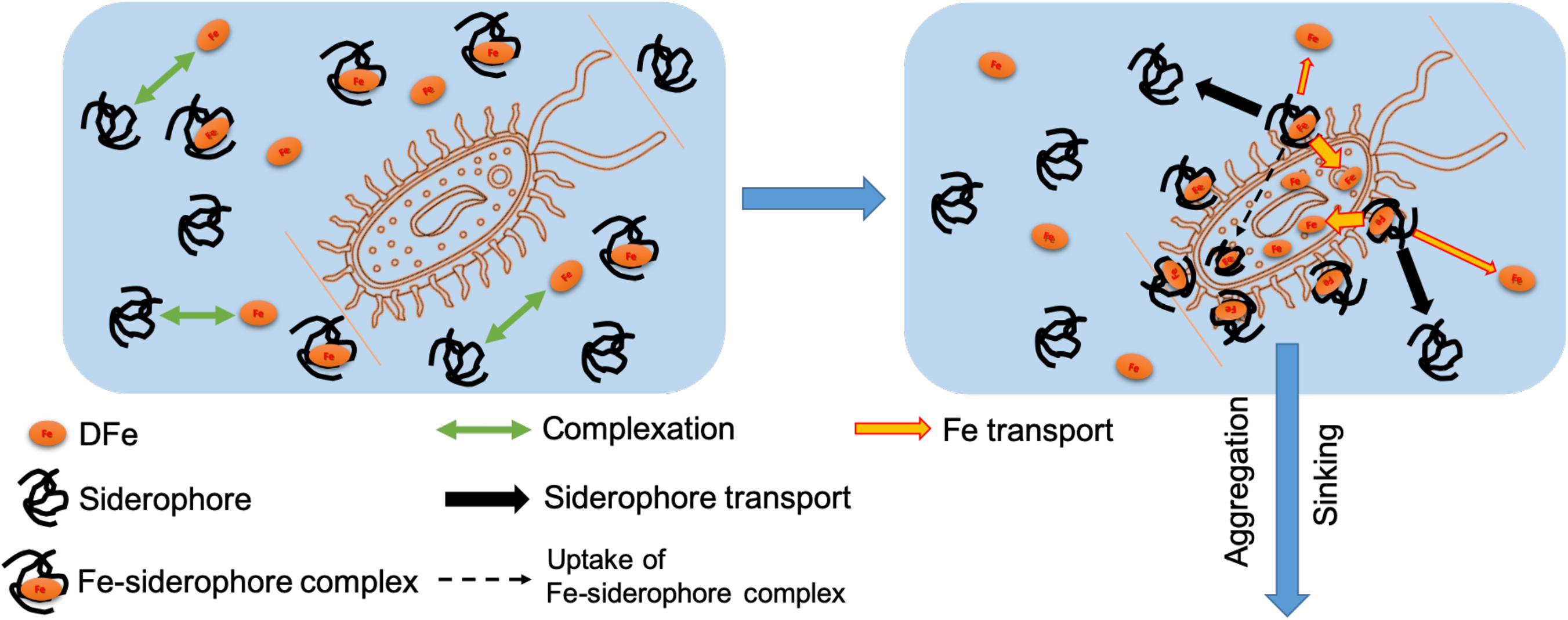

The observed partitioning of siderophore moieties into the suspended particles/aggregates could have resulted from several different mechanisms although one single mechanism cannot be identified completely with the present data. Nevertheless, our observed partitioning of Fe and DFO may still provide some indirect support for the following mechanisms (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Conceptual figure showing the transport pathway for the siderophore to the marine biomass/particles in the ocean.

First, different partitioning between Fe and DFO although they are initially complexed with each other (Figure 2) demonstrates the decomposition of the ferric complex by microbial cellular processes during the Fe uptake in seawater, corresponding well with previous studies indicating the exchange and release of Fe from a Fe-siderophore to an Fe-free organic receptor on the microbial cells (Leong and Neilands, 1976; Stintzi et al., 2000; Hannauer et al., 2010). During this course of the Fe release and transport, ligand exchange and redox-facilitated ligand exchange occurring concurrently give rise to a very stable Fe-siderophore complex with a negative redox potential, resulting in the reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) as a sensitive switch that facilitates the dissociation of Fe from the siderophore complex (Cooper et al., 1978; Dhungana and Crumbliss, 2007). During such a process, the Fe release from Fe-siderophore complex may be rapid without the penetration of the Fe-siderophore complex into the cellular matrix (Leong and Neilands, 1976; Dhungana and Crumbliss, 2007), thus resulting in the release of the siderophore back to the surrounding seawater (Figure 3). Additionally, our observed minor partitioning of particulate siderophore (Figure 2) also indicates another mechanism at work, consisting of slower uptake of the intact Fe-siderophore complex by the microbial cells (Leong and Neilands, 1976, black dash arrow in Figure 3) and transformation into more bioavailable Fe forms afterward inside the cells.

Therefore, our observed partitioning of the DFO (i.e., over 99% of the dissolved DFO and 0.4% of the particulate DFO, Figure 2) after the microbial growth may indirectly suggest that the balance of the two mechanisms (Figure 3) during the Fe-siderophore transport in natural seawater is in favor of the processes occurring outside of the cells (i.e., Fe dissociation from the Fe-siderophore complex followed by the microbial Fe uptake) but that the second mechanism also exists (i.e., the uptake of intact Fe-siderophore complex into the microbial intracellular fractions).

A microbially derived protein encapsulating mechanism can also serve as an alternative pathway (Xu et al., 2020) for the incorporation of Fe-siderophore complex into suspended particles/aggregates in the present study. For example, ferritin proteins, which are produced by marine microbes for Fe storage (Marchetti et al., 2009; Shire and Kustka, 2015), have been demonstrated to encapsulate siderophores into cavity-like structures (Dominguez-Vera, 2004), probably facilitating the incorporation of Fe-siderophore complex into the microbially-derived marine particles in our experiments. Nevertheless, the mechanisms responsible for this incorporation are still not clear and further studies are needed in future, either from the laboratory or field perspective in seawater.

Regardless of the mechanisms, our experimental results provide a minimum estimate for siderophore incorporation into marine particles, since in our experiment we only used one model siderophore compound (i.e., DFO), yet in the natural environment there are many other siderophore compounds that have yet to be identified to be involved. Our observation suggests that although this fraction is minor, siderophores can be indeed retained in the particulate phases after microbial uptake of Fe, providing direct evidence for the incorporation of the siderophore compounds and their associated Fe into the marine particles in the ocean. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that our samples were enriched with carbon source and nutrients (see section “Natural seawater culturing with radiolabeled siderophore”), higher than some open oceanic environments. Thus, the partitioning of siderophore into marine particles in the open ocean can be less dynamic (e.g., the processes in the open ocean can take more time) compared with the observation in the present study.

On the other hand, since the siderophore compound has a strong association with Fe, with the Fe-siderophore complex remaining intact without microbial processes, this may imply that the siderophore compounds can serve as one of the carriers for the Fe being removed into the deeper ocean, corresponding with the field observation in the deep North Atlantic Ocean (e.g., 3200 m) showing considerable fractions of the Fe-carrying organic molecules that were identified to contain hydroxamate siderophore functionalities (Xu et al., 2020).

Considering our incubation medium only included the bacteria, the incorporation of the particulate siderophore compounds could have become cumulatively more important in a more complex natural oceanic system that involves the interplay between bacteria, phytoplankton, zooplankton, and mineral particles. Phytoplankton are well-known to excrete a high abundance of expolymeric substances (EPS), enriched in proteins and polysaccharides, to the surrounding seawaters during their growth (Hassler et al., 2011; Quigg et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2017, 2020). Particle aggregation can occur by hydrostatic interaction of EPS containing a variety of negatively charged functional groups, resulting in hydrogen and metal ion bonding, as well as hydrophobic interactions that can lead to physicochemical cross linking (e.g., resulting in the protein/carbohydrate ratio being predictive for particle aggregation; Santschi et al., 2020). Such processes could have also happened in the present experiment and could have been responsible for the formation of this particulate hydroxamate siderophore compound, which may be enhanced in the more complex natural oceanic system due to the additional EPS contribution from phytoplankton and zooplankton. Similarly, the presence of the mineral particles in natural oceanic systems might also enhance the incorporation of siderophore compounds into marine particles via surface attachment and relatively weak forces (e.g., ionic interactions; Upritchard et al., 2007; Barber et al., 2017). Therefore, one could expect that siderophore compounds would be more abundant in marine particles than we observed here, especially in the upper water column where microbes are more abundant.

Last but not least, trace metals and radioisotopes (i.e., Th and Pa) with high particle affinity and similar binding properties to Fe, which have been used as tracers for oceanic geochemical processes, might follow the same pathways, i.e., the dissolved metal-siderophore incorporation into the marine particles, a relatively larger portion of metal yet a smaller amount of siderophore-like moieties fixed within sinking particles.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

PL, CX, and PS conceived and designed the experiment. PL and WX performed the incubation and partitioning experiment. CX and LS performed the hydroxamate measurement. PL performed the iron-59 measurement. PL and CX performed the data analysis. PL, CX, LS, and PS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was partially supported by a grant from NSF (OCE#1356453). The open access publishing fees for this article have been covered by the Texas A&M University Open Access to Knowledge Fund (OAKFund), supported by the University Libraries.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Barber, A., Brandes, J., Leri, A., Lalonde, K., Balind, K., Wirick, S., et al. (2017). Preservation of organic matter in marine sediments by inner-sphere interactions with reactive iron. Sci. Rep. 7:366.

Bennett, S. A., Achterberg, E. P., Connelly, D. P., Statham, P. J., Fones, G. R., and German, C. R. (2008). The distribution and stabilisation of dissolved Fe in deep-sea hydrothermal plumes. Earth Plant. Sci. Let. 270, 157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2008.01.048

Boiteau, R. M., Mende, D. R., Hawco, N. J., Mcllvin, M. R., Fitzsimmons, J. N., Saito, M. A., et al. (2016). Siderophore-based microbial adaptations to iron scarcity across the eastern Pacific Ocean. PNAS 113, 14237–14242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608594113

Boiteau, R. M., Till, C. P., Coale, T. H., Fitzsimmons, J. N., Bruland, K. W., and Repeta, D. J. (2019). Patterns of iron and siderophore distributions across the California Current System. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 376–389. doi: 10.1002/lno.11046

Boukhalfa, H., and Crumbliss, A. L. (2002). Chemical aspects of siderophore mediated iron transport. Biometals 15, 325–339.

Boyd, P. W., Ibisanmi, E., Sander, S. G., Hunter, K. A., and Jackson, G. A. (2010). Remineralization of upper ocean particles: implications for iron biogeochemistry. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1271–1288. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.3.1271

Boyé, M., van den Berg, C. M. G., de Jong, J. T. M., Leach, H., Croot, P., and de Baar, H. J. W. (2001). Organic complexation of iron in the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Res. I 48, 1477–1497. doi: 10.1016/s0967-0637(00)00099-6

Buck, K. N., Sohst, B., and Sedwick, P. N. (2015). The organic complexation of dissolved iron along the U.S. GEOTRACES (GA03) North Atlantic Section. Deep Sea Res. II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 116, 152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2014.11.016

Bundy, R. M., Boiteau, R. M., McLean, C., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Mcllvin, M. R., Saito, M. A., et al. (2018). Distinct siderophores contribute to iron cycling in the mesopelagic at Station ALOHA. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:61. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00061

Butler, A. (2005). Marine siderophores and microbial iron mobilization. Biometals 18, 369–374. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-3711-0

Chuang, C.-Y., Santschi, P. H., Ho, Y.-F., Conte, M. H., Guo, L., Schumann, D., et al. (2013). Role of biopolymers as major carrier phases of Th, Pa, Po, Pb and Be radionuclides in settling particles from the Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Chem. 157, 131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2013.10.002

Chuang, C.-Y., Santschi, P. H., Wen, L.-S., Guo, L., Xu, C., Zhang, S., et al. (2015). Binding of Th, Pa, Pb, Po and Be radionuclides to marine colloidal macromolecular organic matter. Mar. Chem. 173, 320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2014.10.014

Cooper, S. R., McArdle, J. V., and Raymond, K. N. (1978). Siderophore electrochemistry: relation to intracellular iron release mechanism. PNAS 75, 3551–3554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3551

Dhungana, S., and Crumbliss, A. L. (2007). Coordination chemistry and redox processes in siderophore-mediated iron transport. Geomicrobiol. J. 22, 87–98. doi: 10.1080/01490450590945870

Dominguez-Vera, J. M. (2004). Iron(III) complexation of desferrioxamine B encapsulated in apoferritin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 98, 469–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.12.015

Fitzsimmons, J. N., Conway, T. M., Lee, J.-M., Kayser, R., Thyng, K. M., John, S. G., et al. (2016). Dissolved iron and iron isotopes in the southeastern Pacific Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 1372–1395. doi: 10.1002/2015gb005357

Gillam, A. H., Lewis, A. G., and Andersen, R. J. (1981). Quantitative determination of hydroxamic acids. Analy. Chem. 53, 841–844. doi: 10.1021/ac00229a023

Gledhill, M., and Buck, K. N. (2012). The organic complexation of iron in the marine environment: a review. Front. Microbiol. 28:69. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00069

Hannauer, M., Barda, Y., Mislin, G. L. A., Shanzer, A., and Schalk, I. J. (2010). The ferrichrome uptake pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa involves an iron release mechanism with acylation of the siderophore and recycling of the modified desferrichrome. J. Bacteriol. 192, 1212–1220. doi: 10.1128/jb.01539-09

Hassler, C. S., Norman, L., Nichols, C. A. M., Clementson, L. A., Robinson, C., Schoemann, V., et al. (2015). Iron associated with exopolymeric substances is highly bioavailable to oceanic phytoplankton. Mar. Chem. 173, 136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2014.10.002

Hassler, C. S., Schoemann, V., Nichols, C. M., Butler, E. C. V., and Boyd, P. W. (2011). Saccharides enhance iron bioavailability to Southern Ocean phytoplankton. PNAS 108, 1076–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010963108

Hutchins, D. A., Witter, A. E., Butler, A., and Luther, G. W. (1999). Competition among marine phytoplankton for different chelated iron species. Nature 400, 858–861. doi: 10.1038/23680

Ibisanmi, E., Sander, S. G., Boyd, P. W., Bowie, A. R., and Hunter, K. A. (2011). Vertical distributions of iron-(III) complexing ligands in the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Res. II 58, 2113–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2011.05.028

Kraemer, S. M., Butler, A., Borer, P., and Cervini-Silva, J. (2005). Siderophores and the dissolution of iron-bearing minerals in marine systems. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 59, 53–84. doi: 10.1515/9781501509551-008

Lam, P. J., Ohnemus, D. C., and Marcus, M. A. (2012). The speciation of marine particulate iron adjacent to active and passive continental margins. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 80, 108–124. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.11.044

Leong, J., and Neilands, J. B. (1976). Mechanisms of siderophore iron transport in enteric bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 126, 823–830. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.2.823-830.1976

Lin, P., Xu, C., Xing, W., Sun, L., Schwehr, K. A., Quigg, A., et al. (2020). Partitioning of iron and plutonium to exopolymeric substances and intracellular biopolymers: a comparison study between the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi and the diatom Skeletonema costatum. Mar. Chem. 217:103735. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2019.103735

Lin, P., Xu, C., Zhang, S., Sun, L., Schwehr, K. A., Bretherton, L., et al. (2017). Importance of coccolithophore-associated organic biopolymers for fractionating particle-reactive radionuclides (234Th, 233Pa, 210Pb, 210Po, and 7Be) in the ocean. J. Geophy. Res. Biogeosci. 122, 2033–2045. doi: 10.1002/2017jg003779

Macrellis, H. M., Trick, C. G., Rue, E. L., Smith, G., and Bruland, K. W. (2001). Collection and detection of natural iron-binding ligands from seawater. Mar. Chem. 76, 175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4203(01)00061-5

Marchetti, A., Parker, M. S., Moccia, L. P., Lin, E. O., Arrieta, A. L., Ribalet, F., et al. (2009). Ferritin is used for iron storage in bloom-forming marine pennate diatoms. Nature 457, 467–470. doi: 10.1038/nature07539

Mawji, E., Gledhill, M., Milton, J. A., Tarran, G. A., Ussher, S., Thompson, A., et al. (2008). Hydroxamate siderophores: occurrence and importance in the Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 8675–8680. doi: 10.1021/es801884r

Mawji, E., Gledhill, M., Milton, J. A., Zubkov, M. V., Thompson, A., Wolff, G. A., et al. (2011). Production of siderophore type chelates in Atlantic Ocean waters enriched with different carbon and nitrogen sources. Mar. Chem. 124, 90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2010.12.005

Moore, C. M., Mills, M. M., Arrigo, K. R., Berman-Frank, I., Bopp, L., Boyd, P. W., et al. (2013). Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 701–710.

Morel, F. M. M., and Price, N. M. (2003). The biogeochemical cycles of trace metals in the oceans. Science 300, 944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1083545

Nishioka, J., and Obata, H. (2017). Dissolved iron distribution in the western and central subarctic Pacific: HNLC water formation and biogeochemical processes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62, 2004–2022. doi: 10.1002/lno.10548

Nishioka, J., Obata, H., and Tsumune, D. (2013). Evidence of an extensive spread of hydrothermal dissolved iron in the Indian Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Let. 361, 16–33.

Quigg, A., Irwin, A. J., and Finkel, Z. V. (2011). Evolutionary imprint of endosymbiosis of elemental stoichiometry: testing inheritance hypotheses. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 278, 526–534. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1356

Quigg, A., Passow, U., Chin, W.-C., Xu, C., Doyle, S., Bretherton, L., et al. (2016). The role of microbial exoploymers in determining the fate of oil and chemical dispersants in the ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 1, 3–26. doi: 10.1002/lol2.10030

Quigg, A. (2016). “Ch. 10 Micronutrients,” in The Physiology of Microalgae, Vol. 6, eds M. A. Borowitzka, J. Beardall, and J. A. Raven (Dordrecht: Springer), 211–231.

Santschi, P. H., Xu, C., Schwehr, K. A., Lin, P., Sun, L., Chin, W.-C., et al. (2020). Can the protein/carbohydrate (P/C) ratio of exopolymeric substances (EPS) be used as a proxy for their ‘stickiness’ and aggregation propensity? Mar. Chem. 218:103734. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2019.103734

Shire, D. M., and Kustka, A. B. (2015). Luxury uptake, iron storage and ferritin abundance in Prochlorococcus marinus (Synechococcales) strain MED4. Phycologia 54, 398–406. doi: 10.2216/14-109.1

Stintzi, A., Barnes, C., Xu, J., and Raymond, K. N. (2000). Microbial iron transport via a siderophore shuttle: a membrane ion transport paradigm. PNAS 97, 10691–10696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200318797

Upritchard, H. G., Yang, J., Bremer, P. J., Lamont, I. L., and McQuillan, A. J. (2007). Adsorption to metal oxides of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa siderophore pyoverdine and implications for bacterial biofilm formation on metals. Langmuir 23, 7189–7195. doi: 10.1021/la7004024

Velasquez, I. B., Ibisanmi, E., Maas, E. W., Boyd, P. W., Nodder, S., and Sander, S. G. (2016). Ferrioxamine siderophores detected amongst iron binding ligands produced during the remineralization of marine particles. Front. Mar. Sci. 3:172. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00172

Vong, L., Laes, A., and Blain, S. (2007). Determination of iron-porphyrin-like complexes at nanomolar levels in seawater. Analy. Chim. Acta 588, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.02.007

Xu, C., Lin, P., Sun, L., Chen, H., Xing, W., Kamalanathan, M., et al. (2020). Micolecular nature of marine particulate organic iron-carrying moieties revealed by electrospray ionization Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI-FTICRMS). Front. Earth Sci. Biogeosci. 8:266. doi: 10.3389/feart.2020.00266

Xu, C., Zhang, S., Chuang, C.-Y., Miller, E. J., Schwehr, K. A., and Santschi, P. H. (2011). Chemical composition and relative hydrophobicity of microbial exopolymeric substances (EPS) isolated by anion exchange chromatography and their actinide-binding affinities. Mar. Chem. 126, 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2011.03.004

Xu, C., Zhang, S., Kaplan, D. I., Ho, Y.-F., Schwehr, K. A., Roberts, K. A., et al. (2015). Evidence for hydroxamate siderophores and other N-containing organic compounds controlling 239,240Pu immobilization and remobilization in a wetland sediment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11458–11467. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02310

Yarimizu, K., Cruz-Lopez, R., Garcia-Mendoza, E., Edwards, M., Carter, M. L., and Carrano, C. J. (2019). Distributions of dissolved iron and bacteria producing the photoactive siderophore, vibrioferrin, in waters off Southern California and northern Baja. Biometals 32, 139–154. doi: 10.1007/s10534-018-00163-3

Keywords: iron, siderophore, marine particle, Gulf of Mexico, partitioning

Citation: Lin P, Xu C, Sun L, Xing W and Santschi PH (2020) Incorporation of Hydroxamate Siderophore and Associated Fe Into Marine Particles in Natural Seawater. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:584628. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.584628

Received: 17 July 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020;

Published: 12 November 2020.

Edited by:

Johan Schijf, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES), United StatesReviewed by:

Yoshiko Kondo, Nagasaki University, JapanThibaut Wagener, Aix-Marseille Université, France

Copyright © 2020 Lin, Xu, Sun, Xing and Santschi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peng Lin, cGVuZ0wxMTA0QHRhbXVnLmVkdQ==

Peng Lin

Peng Lin Chen Xu

Chen Xu Luni Sun

Luni Sun Wei Xing

Wei Xing Peter H. Santschi1,2

Peter H. Santschi1,2