- 1College of Marine Life Sciences, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Marine Genetics and Breeding of Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 3Department of Pharmacy, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases (MAPKKKs) are pivotal components of MAPK cascades. Pyropia yezoensis, belonging to Rhodophyta, is an important macroalga growing in the intertidal zone of temperate Japan and China. At present, little is known about MAPKKKs and their potential regulatory mechanisms in response to environmental stressors in red algae, particularly with regard to how this gene family retained its ancient characteristics. In this study, we identified 33 MAPKKK genes in P. yezoensis by bioinformatics analysis. Phylogenetic analysis classified them into Raf, MEKK and ZIK groups, which contained conserved kinase motif with minor variations. The number of intron of all PyMAPKKK is few, up to 3. Regulatory elements prediction indicated that the cis-acting elements included many motifs involved in the stress response. Furthermore, expression analysis of PyMAPKKKs under different stress conditions revealed that numerous PyMAPKKK genes were involved in various signaling pathways with different expression patterns. Additionally, 16 PyMAPKKK genes were validated their expression patterns by Realtime-PCR analysis. An interactome network of PyMAPKKK was constructed to show that most of the interacting proteins were serine/threonine protein kinases, MAPKs, and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Our study provided helpful information for understanding the evolution and function of the MAPKKK family in P. yezoensis.

Introduction

Plants are confronted by many biotic and abiotic stresses that challenge their survival. To deal with such stresses, plants have evolved various and complicated biochemical and physiological mechanisms. These molecular pathway involved in adaption to stress include multiple inter-linked regulatory networks, such as protein kinase signaling cascades (Hamel et al., 2006). The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade is the best characterized kinase based on amplification cascades and is an evolutionarily conserved and fundamental signal transduction pathway that plays roles in the transduction of extracellular stimuli into intracellular responses in eukaryotes (Xu and Zhang, 2015). The MAPK cascade has been found to be involved in response to various abiotic and biotic stresses, such as drought (Colcombet and Hirt, 2008), low temperature (Zhao et al., 2017), high salt (Li et al., 2016), osmotic stress (Colcombet and Hirt, 2008), oxidative stress (Colcombet and Hirt, 2008), and pathogen infection (Meng and Zhang, 2013).

The typical MAPK cascade comprise three kinase modules: MAPKKK/MEKK, MAPKK/MKK, and MAPK/MPK (Mészáros et al., 2006). MAPKKK proteins in the beginning of the cascade receive upstream signals to activate the MAPKK proteins by phosphorylating the serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) residues in the conserved motif (Ser/Thr-X3–5-Ser/Thr; X indicates any amino acid) (Mishra et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006). The activated MAPKK proteins further activate of downstream MAPK proteins in the T-X-Y motif (Mishra et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006). The phosphorylated MAPK proteins then activate multiple downstream target proteins, including transcription factors, protein kinases, and cytoskeletal components (Mishra et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006). To date, different MAPK cascade gene family members have been identified in many plants following the completion of the sequencing of various genomes, such as 80 MAPKKK, 10 MAPKK, and 20 MAPK in Arabidopsis thaliana, 75 MAPKKK, 8 MAPKK, and 17 MAPK genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.) (Jonak et al., 2002; Colcombet and Hirt, 2008; Rao et al., 2010; Sinha et al., 2011), 74 MAPKKK, 9 MAPKK, and 19 MAPK maize (Zea mays L.), 89 MAPKKKs, 6 MAPKKs, and 16 MAPKs in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) (Kong et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014), 58 MAPKKKs, 6 MAPKKs, and 14 MAPKs in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.), and 78 MAPKKKs, 11 MAPKKs, and 28 MAPKs in cotton (Gossypium spp.) (Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016).

Compared to MAPKs and MAPKKs, MAPKKKs in higher plants have more members, and the structures and compositions of their conserved domain are more complex (Hamel et al., 2014). Based on the long N- or C- terminal regions, MAPKKK can be subdivided into Raf, MEKK, and ZIK groups (Wrzaczek and Hirt, 2001; Jonak et al., 2002). Phylogenetic characteristics of MAPKKK genes in various species has revealed quantitative diversity among the three major subgroups in plants. There are 46 Raf MAPKKKs in maize, 43 in rice, 27 in grapevine, and 48 in A. thaliana, and there are 22 MEKK group members in maize, 22 in rice, nine in grapevine, and 21 in A. thaliana. However, there are only six MAPKKKs in maize, 10 in rice, nine in grapevine, and 11 in A. thaliana that are grouped into the ZIK group (Jonak et al., 2002; Rao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2014). Structure domain analysis of MAPKKKs in higher plants indicates that most Raf proteins contain a long N-terminal regulatory domain and a C-terminal kinase domain. In contrast, members of the ZIK group contain the N-terminal kinase domain, while members of the MEKK group contain a less conserved kinase domain that exists in either N- or C-terminal or in the central part of the protein (Popescu et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015).

In plants, the detailed MAPK cascade pathways mediated by MAPKKK that are involved in various environmental stresses have been identified in detail in some model species (Gao and Xiang, 2008; Ning et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012; Benhamman et al., 2017). In A. thaliana, the cascade MEKK1-MKK4/5-MPK3/6-WRKY22/WRKY29 was found to participate in resistance against multiple pathogens (Asai et al., 2002). The YODA, an MAPKKK that activates the downstream module MKK4/MKK5-MPK3/MPK6, functions as a key regulator of stomatal patterning and flower formation in A. thaliana (Wang et al., 2007; Meng et al., 2012). The MEKK1-MKK2-MPK4/MPK6 cascade mediates cold and salt stress responses in A. thaliana (Teige et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2017), and the MEKK1-MKK1/Mkk2-MPK4 cascade regulates negatively innate immune responses (Gao et al., 2008), while tobacco MAPK cascade NPK1-MEK1-Ntf6 funtions in tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) resistance (Jin et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2004). More recently, the MAPKKK17/18-MKK3-MPK1/2/7/14 cascade was found to be involved in abscisic acid (ABA) responding to abiotic stress (Danquah et al., 2015). However, little is known about MAPKKK information in macroalgae. Parages reported that p38- and JNK-like MAPKs existed in Arctic kelps and responded to desiccation, high ultraviolet irradiance and temperature (Parages et al., 2012, 2014). Pyropia yezoensis (Rhodophyta) is an important macroalga growing in the intertidal zone. Compared with higher plants, foliar thalli of Pyropia consist of only one or two layers of cells. For the characters of intertidal zone, it periodically suffered from various potentially stressful environmental factors, including desiccation, osmotic stress, high light, and high and low temperatures (Li et al., 2018). There is limited information about MAPKKKs of red algae and their potential role in its adaptation to the environment. Sequencing of the P. yezoensis genome has provided a great opportunity to analyze gene family evolution. Previously, we systematically analyzed the P. yezoensis MAPK gene family and putative expression profiles after exposing the alga to temperature and desiccation (Li et al., 2018). To further clarify how the MAPK cascade operates and whether it responds to a variety of stresses in P. yezoensis, we further surveyed the MAPKKK gene family in the P. yezoensis genome using bioinformatics analysis in this study. Our findings will not only be helpful for deeply analyzing MAPK cascade signal pathways in P. yezoensis, but should also improve our understanding of the mechanisms of stress signal transduction in P. yezoensis.

Materials and Methods

Algal Material and Stress Treatment

The pure line PY4-7 of P. yezoensis, established by our laboratory at Ocean University of China, was used in this study. Fresh leafy gametophytes were cultured in sterilized seawater with Provasoli’s enriched seawater medium at 12°C and 60 μmol photons ⋅ m–2.s–1 with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. The seawater was bubbled continuously with filter-sterilized air and renewed every 3 days. For water stress, the thalli were desiccated until the total water content lost 30, 50, and 80% of full hydration. And then after losing 80% water content, the samples were recovered in normal seawater for 30 min. Three biological replicates were set for each treatment. These samples were harvested and placed in liquid nitrogen for gene expression analysis.

Identification of the MAPKKK Gene Family in P. yezoensis

The P. yezoensis MAPKKK gene family was identified following the methods described by Rao et al., with some modifications (Rao et al., 2010; Li et al., 2018). Our laboratory has completed the sequencing of P. yezoensis genome and the sequencing data were deposited under DDBJ/ENA/GenBank WMLA00000000. Firstly, the local protein database predicted by our laboratory was blasted with 155 known MAPKKK gene sequences including A. thaliana (80) and O. sativa (75). The threshold was e-value of le–5. The alignments of all the putative MAPKKK sequences were further used to construct hidden Markov model (HMM) profile using the hmmbuild tool in HMMER3.01, and then the HMM profile was searched against the local protein database. HMMER and BLAST hits were compared and the common sequences were selected as the putative PyMAPKKK proteins, which were submitted to the NCBI Batch CD-search database2 and PFAM database3 to confirm the presence of the kinase domain. Finally, 33 proteins remained and were considered to be PyMAPKKKs. The prediction methods of MAPKKKs for other red algae (Cyanidioschyzon merolae, P. haitanensis, Porphyra umbilicalis, and Porphyridium purpureum) were the same as above. Their genomes have been sequenced and the accession numbers are GCA_000091205.1, GCA_008729055.1, GCA_002049455.2, and GCA_000397085.1, respectively. The theoretical pI and Mw of the putative PyMAPKKKs were calculated using the Compute pI/Mw tool in the ExPASy database4. Subcellular localization of each PyMAPKKK cascade kinase was predicted by the WoLF PSORT tool5.

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Construction

The kinase domain sequences of the predicted MAPKKKs in P. yezoensis, the four red algae species mentioned above, and A. thaliana and O. sativa were multi-aligned using the MUSCLE (Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation) program. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MrBayes version 3.2.5 (Ronquist et al., 2012) with the following parameter settings: prset aamodelpr = mixed, mcmc ngen = 10 million samplefreq = 10. The operation terminated when the standard deviation of the split frequencies was ≤ 0.01, and the operation results were visualized using sump burnin = 250 and sumt burnin = 250.

Gene Promoters and Structure Analysis

The DNA sequences of PyMAPKKK gene containing exon sequences were submitted to Gene Structure Display Server6 to display the exon/intron structures. To assess the regulatory elements of PyMAPKK genes, 2-kb upstream sequences of gene ORF were selected. All the sequences were submitted to the PlantCARE database7 to identify the cis-acting regulatory elements (Lescot et al., 2002).

MAPKKK Gene Expression Analysis

In order to gain insight into the expression characteristics of the PyMAPKKK gene family when the alga is exposed to different stressors, including different dehydration and temperature treatments, transcriptome sequencing data were obtained to investigate the differential expression of PyMAPKKKs. The RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) data were obtained from a previous study by our laboratory under the accession numbers PRJNA236059 and PRJNA401507 (Sun et al., 2015). The treatments of water and temperature stress were set according to RNA-sequencing. Three biological replicates were tested for each condition. TopHat and Cufflinks were used to analyze gene expression based on the RNA-Seq data (Trapnell et al., 2012). The FPKM value (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) of each PyMAPKKK gene was calculated, and the log2-transformed values of the 33 PyMAPKKK genes were used to generate heatmaps. The heatmaps and dendrograms were created in R × 86_64-w64-mingw32/ × 64 platform (64-bit) (Maindonald, 2008).

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (OMEGA) according to the manufacturer’s procedure. qRT-PCR analysis was followed by Kong et al. (2017). Then 1 μg total RNA was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Germany). qRT-PCR was performed with Light Cycler®480 (Roche, Germany). Sequence-specific primers of the genes studied in this research were designed using Primer 5.0 software (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, United States) (Table 1). The PyTub1 and PyeIF4A were selected as internal controls. The 2–ΔΔCt method was used to assess the expression level of genes (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The expression levels were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (P < 0.05) in SPSS 19.0 software. The qPCR results shown were the average (± SD) of three biological repeats.

Protein Interaction Network Analysis

Protein.links.v10.5.txt.gz and protein.sequences.v10.5.fa.gz were download from STRING8 (Szklarczyk et al., 2010). Protein.sequences.v10.5.fa.gz was used as a standard database, and the PyMAPKKK and P. yezoensis protein databases were compared against the standard database, and then the links file (Protein.links.v10.5.txt.gz) was used to establish the relevance of the two databases (PyMAPKKK sequence database and P. yezoensis protein database). Furthermore, sequences with an interaction score ≥ 400 were selected, and the functional annotations were searched in the non-redundant (Nr) database. Finally, the network was visualized using Cytoscape version 3.5.1. Additionally, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was also performed using OmicShare Tools9.

Results and Discussion

The Identification of the MAPKKK Family at Genome Level in P. yezoensis

PyMAPKKK gene family members were identified based on the complete genome sequence of P. yezoensis. A total of 155 known MAPKKK protein sequences were used as a query to search the P. yezoensis protein database by local BLAST search. 56 hits were obtained as candidate sequences. Out of these hits, only 33 MAPKKK protein sequences contained a kinase domain and their genes contained the full-length ORF. The filtered MAPKKK genes in P. yezoensis were designated as PyMAPKKK1 to PyMAPKKK33.

The length of the cDNA of the PyMAPKKK genes ranged from 642 bp (PyMAPKKK1) to 6,762 bp (PyMAPKKK5). The encoded polypeptides ranged from 213 to 2,253 amino acids (aa). The predicted molecular weight (Mw) ranged from 22.74 kDa (PyMAPKKK1) to 219.15 kDa (PyMAPKKK5), and the isoelectric point (pI) values ranged from 5.45 (PyMAPKKK11) to 11.14 (PyMAPKKK32). The subcellular location prediction indicated that most of the MAPKKK proteins were localized in the chloroplast (57.6%), followed by the nucleus (27.3%) and the cytoplasm (12.1%). Only PyMAPKKK2 was predicted to localize in the plasma membrane. The diverse subcellular localization of the PyMAPKKK is similar with that of higher plants. The accession number, the length of the cDNA and protein, the Mw, and the pI and subcellular localization of the PyMAPKKKs are summarized in Table 1.

Furthermore, we also analyzed the MAPKKK family in other red algae, including single-cellular and multi-cellular species for which complete genome sequences were available. The results showed that there are 19 MAPKKKs in C. merolae, 43 MAPKKKs in P. purpureum, 31 MAPKKKs in P. umbilicalis, and 28 MAPKKKs in P. haitanensis (Table 2). As mentioned above, there are over 60 putative MAPKKK genes in higher plants. This indicated that the number of MAPKKK genes from P. yezoensis and red algae is significantly lower than in higher plants.

Table 2. Comparison of the gene abundance in three subfamilies of MAPKKK genes in different plants and red algae.

Phylogenetic and Conserved Domains Analysis of PyMAPKKKs

In plants, the MAPKKK family can be divided into MEKK, Raf, and ZIK subfamilies based on their conserved domain. The MEKK-specific signature is G (T/S) PX (F/Y/W) MAPEV; ZIK members have a GTPEFMAPE (L/V) (Y/F) conserved signature motif; and Raf members possess the GTXX (W/Y) MAPE motif (Feng et al., 2016). To subcategorize PyMAPKKKs, we further analyzed the conserved signature motif in PyMAPKKKs. In our research, 33 PyMAPKKK members contained three types of conserved motifs. Twenty-five PyMAPKKKs contained G (T/S) xxxxAPE, which is similar to the Raf type. PyMAPKKK1, PyMAPKKK2, PyMAPKKK10, PyMAPKKK13, PyMAPKKK17, and PyMAPKKK19 contained G (T/S) P (L/F/Y) WMAPE (L/V), which is similar to the ZIK type. PyMAPKKK1 and PyMAPKKK21 contained the signature of GTPHxxAPE, which is similar to MEKK (Figure 1). Based on the results, the Raf subfamily was the largest subfamily, whereas the MEKK subfamily was the smallest subfamily in P. yezoensis. In comparison to the conserved signature motifs of higher plant MAPKKKs, some minor variations existed in the PyMAPKKKs, yet the similar classification results indicated that the divergence of the MAPKKK gene family occurred prior to the separation of higher plants and rhodophytes.

Figure 1. The alignment of MAPKKK protein kinase domain sequence in P. yezoensis. Alignment was performed using MUSCLE (Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation) program and DNAMAN. The highlighted part shows the conserved signature motif.

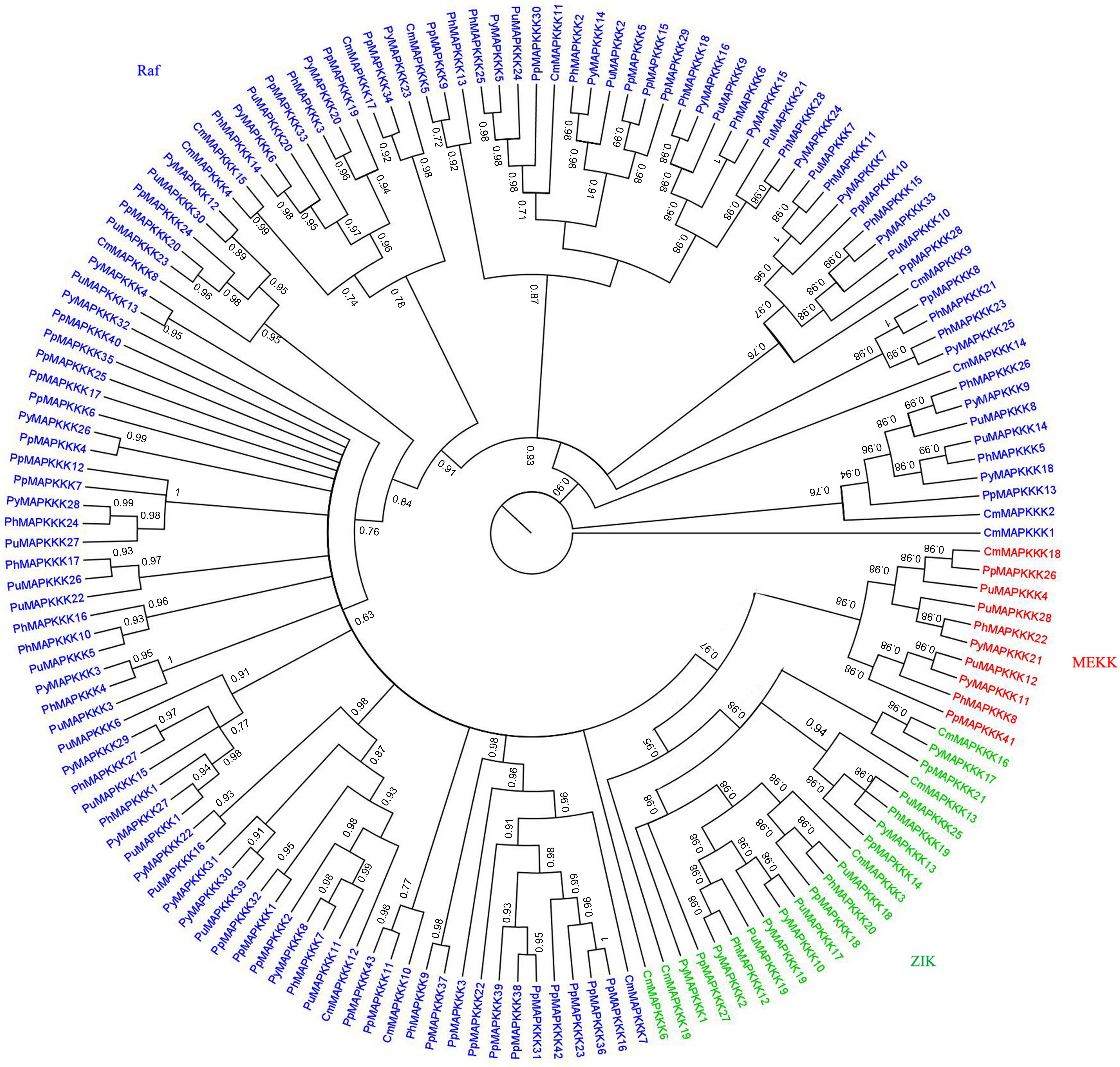

To further analyze the phylogenetic relationships of the MAPKKK genes in P. yezoensis, the kinase domain sequences of MAPKKKs from P. yezoensis and four other Rhodophyta species including three macroalgae and two primitive algae were aligned and a Bayesian phylogenetic tree was constructed. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, the PyMAPKKK family could be classified into three major groups with strong bootstrap values, each including members of the Raf, ZIK, and MEKKs subfamily, respectively (Figure 2). For PyMAPKKKs, 25 members clustered together, forming the largest group (Raf group), whereas PyMAPKKK11 and PyMAPKKK21 clustered together and formed the smallest group (MEKK group). Others, including PyMAPKKK1, PyMAPKKK2, PyMAPKKK10, PyMAPKKK17, and PyMAPKKK19 formed the ZIK group (Figure 2). In the Raf group, 25 members could be further divided into two subgroups with 10 and 15 members, respectively. This may indicate that obvious gene expansion or divergence occurred in the Raf group of PyMAPKKK during evolution, forming two sister groups. The phylogenetic tree from five red algae species also showed three groups with strong bootstrap values (Figure 3 and Table 2). Similar with PyMAPKKK classification, the Raf subfamily was the largest, followed by the ZIK subfamily, and MEKK subfamily was the least. Yet in higher plants, Raf subfamily was also the largest, while ZIK subfamily was the least subfamily. In general, most members containing the typical signal domain were classified into the major group, especially for Raf and MEKK family members. In ZIK family, CmMAPKKK6 did not cluster together with other members and formed a single clade. It was inferred that it was an independent member of CmMAPKKK. Furthermore, the MAPKKK orthologs of the multicellular red algae clearly clustered together, and the PyMAPKKKs almost clustered together with the PuMAPKKKs and PhMAPKKKs, which was in consistent with the evolutionary relationship of species. Compared to the numbers of MAPKKKs in unicellular algae, it maybe that the MAPKKK gene family of multicellular red algae experienced significant evolutionary expansion. Gene expansion event also existed in MAPKKK gene family of higher plants, especially in Raf and MEKK subfamily (Feng et al., 2016).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships, gene structures and protein structure of 33 PyMAPKKKs, (A) is the picture of PyMAPKKK evolutionary trees, (B) is the gene structure of PyMAPKKKs, (C) is the protein structure of PyMAPKKKs.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree of MAPKKKs from P. yezoensis, C. merolae, P. haitanensis, P. umbilicalis and P. purpureum. Phylogenetic tree was created using bayes_3.2.5, using protein kinase domain of 155 MAPKKK proteins. Red labeled MEKK subfamily, green labeled ZIK subfamily, blue labeled Raf subfamily.

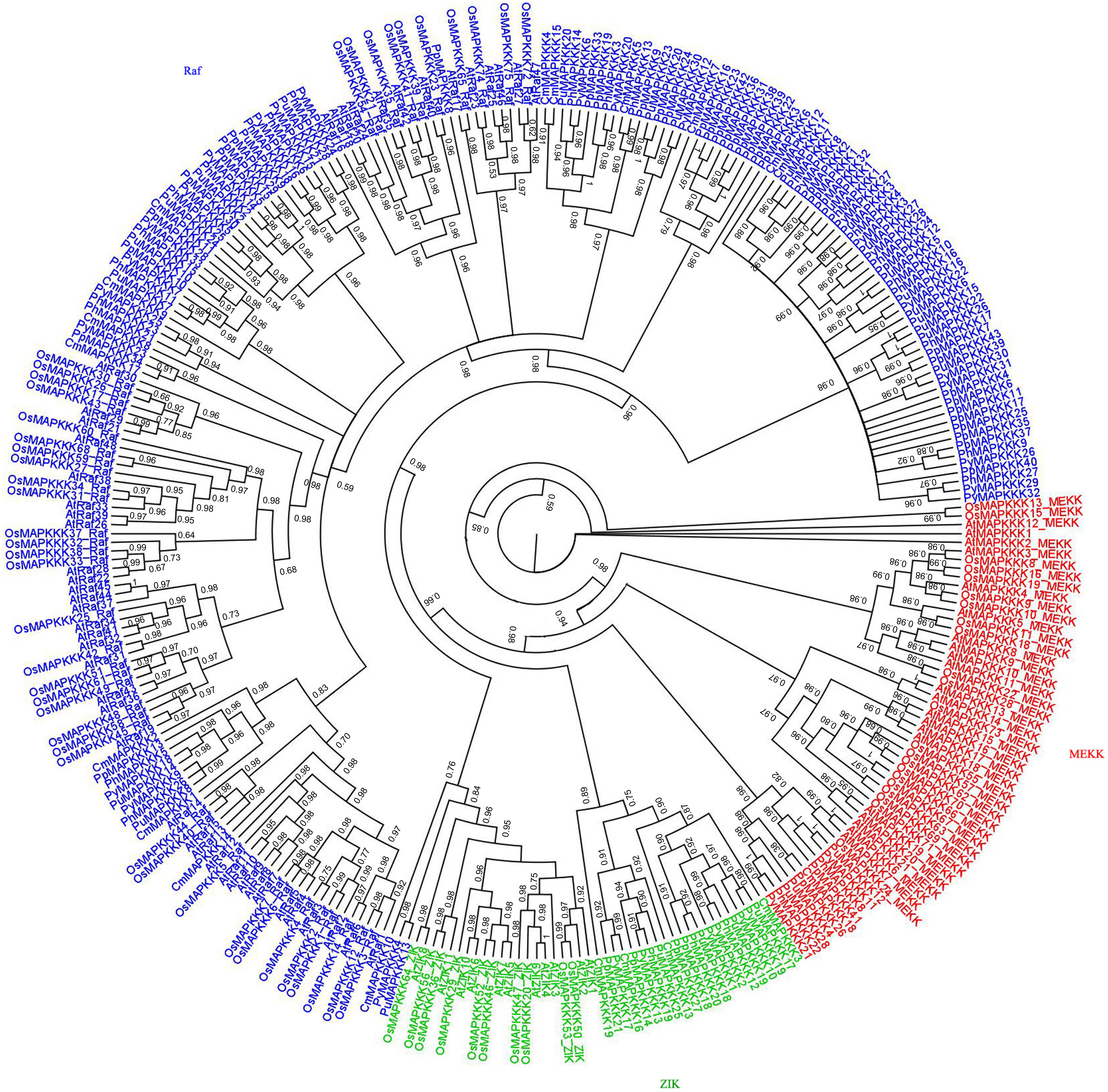

To analyze the evolutionary relationships of MAPKKK proteins between rhodophytes and higher plants, a phylogenetic tree was built based on an alignment of the amino acid sequences of all 309 MAPKKK kinase domains (33 in P. yezoensis, 19 in C. merolae, 43 in P. purpureum, 31 in P. umbilicalis, 28 MAPKKKs in P. haitanensis, 80 in Arabidopsis, and 75 in rice). As indicated in Figure 4, most MAPKKKs still formed three large groups with strong bootstrap values, suggesting that the divergence of the three MAPKKKs subfamilies occurred prior to the divergence of rhodophytes and green plants. It is worth noting that CmMAPKKK10, PyMAPKKK4 and PuMAPKKK13 belonging to Raf subfamily, were clustered with ZIK subfamily members. It was inferred that although they contained typical kinase domain, yet more variations occurred in other domain of their protein. Furthermore, in each group, a few MAPKKKs clustered together with those of higher plants, while most red algae MAPKKKs clustered together, indicating that some rhodophyte MAPKKKs evolved independently. ML phylogenetic tree was also constructed to show the same topological tree (Supplementary Figure 1), which indicated the constructing tree method with Bayesian was reliable.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic tree of MAPKKKs from five red algae, rice, and Arabidopsis. Phylogenetic tree was created using bayes_3.2.5, using protein kinase domain of 307 MAPKKK proteins, using protein kinase domains of 152 red algae, 75 rice and 80 Arabidopsis MAPKKK proteins. Red labeled MEKK subfamily, green labeled ZIK subfamily, blue labeled Raf subfamily.

Protein kinases play roles by protein phosphorylation (Jiang et al., 2015). In this research, we found that a kinase domain (IPR00719) existed in all the PyMAPKKK proteins, and most of proteins contained the Ser/Thr kinase active site (IPR008271) in the central part of the catalytic domain, except for five PyMAPKKKs (PyMAPKKK1, PyMAPKKK2, PyMAPKKK10, PyMAPKKK12, and PyMAPKKK13). The existence of these typical features reflected the MAPKKK conservation of structure and function, which is the same in red algae and green higher plants. The ATP-binding site (IPR017441) is also located on the catalytic domain of most PyMAPKKKs, which is a conserved sequence in the kinase family (Wang et al., 2015), suggesting that ATP as a substrate is involved in the PyMAPKKK phosphorylation cascade, activating the activity of downstream protein kinases to complete the signal transduction process. In addition, the PyMAPKKKs also possessed some other conserved domains. For example, an ankyrin repeat-containing domain (IPR020683), which is related to protein-protein interaction and has been found in different kinds of proteins, such as cell cycle regulators, ion transporters, transcriptional initiators, the cytoskeleton, and signal transducers (Gorina and Pavletich, 1996; Sedgwick and Smerdon, 1999), also existed in the domain of PyMAPKKK4 and PyMAPKKK5. PyMAPKKK23 possesses the TyrA (ACT) domain, which is involved in metabolic enzymes by responding to amino acid concentrations changes (Aravind and Koonin, 1999). PyMAPKKK11 and PyMAPKKK21 possess the armadillo-like helical (IPR011989), which has been implicated in protein-protein interactions (Han et al., 2012). PyMAPKKK9 and PyMAPKKK18 contain the domain of the toll/interleukin-1 receptor homology (IPR000157), which has been demonstrated to play a role in immune responses for pathogen recognition (Wang et al., 2016b), and thus PyMAPKKK9 and PyMAPKKK18 may be involved in the regulation of innate immunity in P. yezoensis. Identification and analysis of these conserved domains demonstrated that the PyMAPKKKs possess a variable functional domain, which may be helpful in the adaptation to harsh abiotic and biotic intertidal zone environments. These conserved domains were also found in the MAPKKK proteins of higher plants, indicating that the functions of MAPKKKs were conserved during in evolution.

Gene Structure Analysis of PyMAPKKK Genes and the Promoter Regions of PyMAPKKKs

Gene structure analysis facilitates a better understanding of gene evolution, function, and regulation (Wu et al., 2014). The gene structure of the PyMAPKKKs was relatively variable. Generally, 15 PyMAPKKK gene members contained no intron, 14 members contained one intron, three members contained two introns, and only one gene contained three introns (Figure 2). Although the number of introns among the three subfamilies did not show too much variation, the MEKK group contained the highest variation in structure among the three groups. Among the Raf subfamily, two out of 25 genes had two introns, 10 genes had one intron, and 13 gens had no intron, while two of these genes (PyMAPKKK5 and PyMAPKKK22) had longer introns. Overall, the number of MAPKKK introns in P. yezoensis was less than that in higher plants, which usually contain seven to eight introns per gene, and up to 20 introns in total (Feng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016a). Intron gain or loss are considered to be the result of selection pressures during evolution, and thus it can be inferred that the speed of intron gain in P. yezoensis was much slower than that of green plants during gene evolution. The genes of P. yezoensis have few introns with 0.63 of the number of introns per gene (Nakamura et al., 2013). This phenomenon is also very common in the P. yezoensis genome. A low number of introns has also found in other red algae genes and is possibly a reason resulting in a reduction in genome size of red algae (Collén et al., 2013; Nakamura et al., 2013).

The promoter is the DNA region of the transcription factor recognizing and binding and plays a key role in the regulation of gene spatial and temporal expression (Kong et al., 2012). Prediction analysis of the 2 kb upstream region of the start codon ATG of PyMAPKKKs was used to screen for cis-regulatory elements (Supplementary Table 1). The results showed that the cis-acting element could be divided into two groups: motifs related to plant growth and development and motifs related to the stress response, which is similar to results obtained in Brachypodium, tomato, and cucumber (Wu et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Plant growth and development-related motifs include five categories: light response elements (G-box, sp1, ACE, 3-AF1 binding site), meristem expression elements (CAT-box and CCGTCC-motif), an endosperm expression element (sk-1_motif), a metabolism related element (O2-site), and a circadian clock control element (circadian motif). Abiotic stress-related motifs include five categories: a cis-acting regulatory element essential for anaerobic induction (ARE), a cold-stress related element (LTR), drought related elements (TC-repeat/DRE and MBS), wounding related elements (Box-W1, W-box, and box S), and hormonal regulation related elements (ABRE, CE3, AuxRR-core, P-box, CARE-motif, TGA-element, TCA-motif, CGTCA-motif, and TGACG-motif), indicating that PyMAPKKKs may be involved in regulating various stress responses and hormone signaling transduction processes. It was noted that nine PyMAPKKKs contained LTR, and 26 PyMAPKKK genes possessed the drought stress related elements TC-repeat/DRE and MBS, which are involved in an ABA-independent pathway in response to dehydration and salt stress (Dolan-O’Keefe and Ferl, 2000). This indicates that PyMAPKKKs play an important role in the adaptation of P. yezoensis to the inter-tidal environment where it is exposed to low temperatures and desiccation. Various regulatory elements related to hormones, including a TCA-element related to salicylic acid (SA) expression, P-motif and CARE-motif related to gibberellic acid (GA)-responsive elements, a TGA-element related to an auxin-responsive element, and CGTCA-motif and TGACG-motifs related to methyl jasmonate (MeJA)-responsiveness, were also identified in the PyMAPKKKs (Zheng et al., 2017). In particular, 31 PyMAPKKK contained an ABA responsive element (ABRE element), which is involved in ABA responsiveness. ABRE is a key cis-regulatory element in ABA signaling and mediates plant responses to many biotic and abiotic stresses, such as water stress, high salinity, temperature extremes, and exposure to UV light (Watanabe et al., 2017). For example, OsMAPK5 was shown to be activated by ABA and was found to further increase tolerance to abiotic (pathogen infection) and biotic (wounding, drought, salt, and cold) stresses in rice (Xiong and Yang, 2003), and thus it was inferred that PyMAPKKK genes may be involved in the mediation of ABA in the response of P. yezoensis to abiotic stress.

Expression Analysis of PyMAPKKK Genes When Exposed to Different Stressors

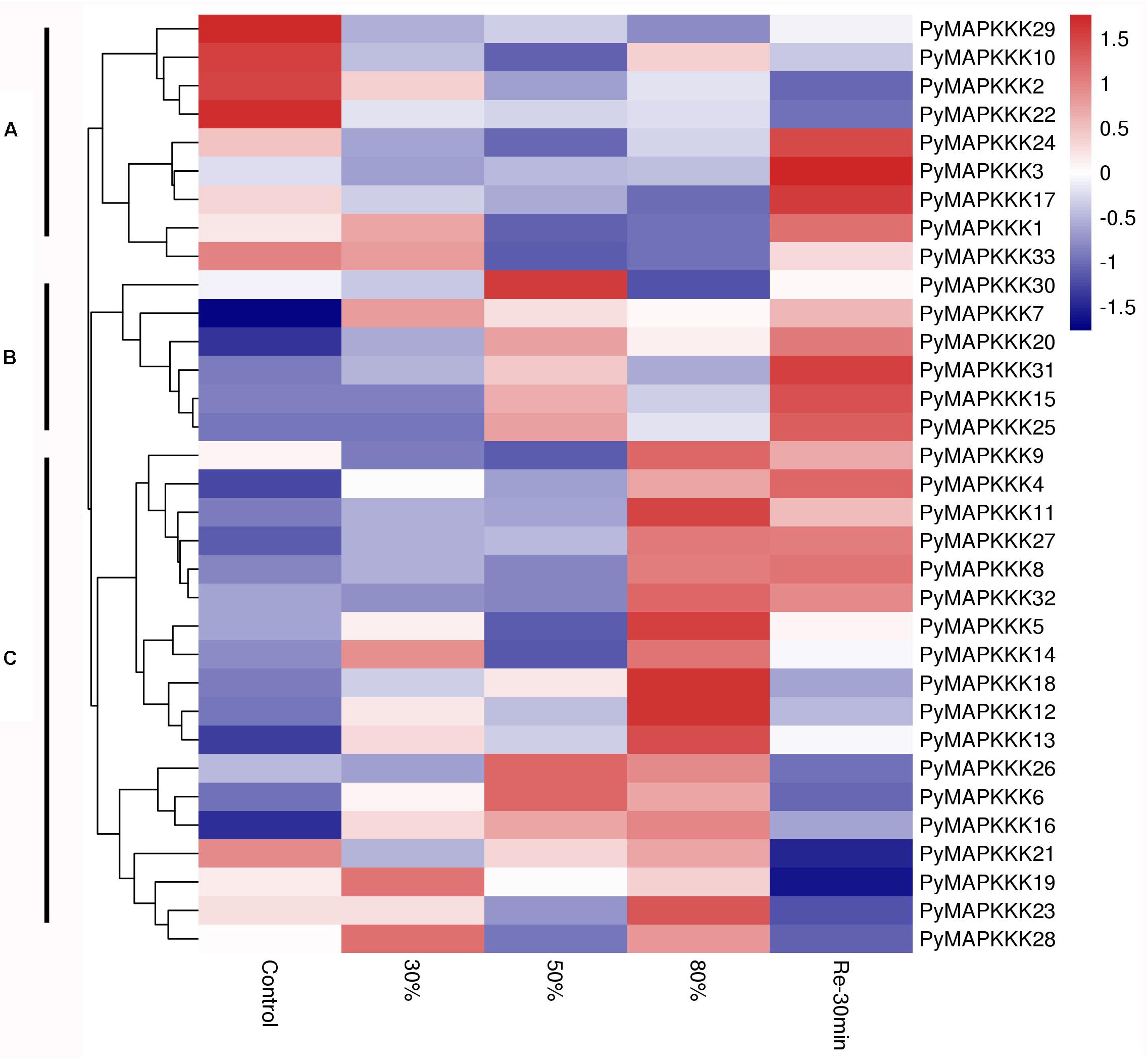

To gain further insight into the spatial and temporal patterns of different MAPKKK family members in P. yezoensis in response to stress factors, their expression profiles under dehydration and temperature stress were compared. The 33 PyMAPKKK genes were investigated using available RNA-Seq data for two different stress conditions. The heatmaps in Figures 5, 6 represent the abundance of each transcript at hydration and temperature stress. The expression levels of the PyMAPKKKs varied significantly in the different conditions based on the log2-transformed (FPKM) values. As indicated in studies in higher plants, drought can seriously limit the productivity and distribution of plants. As the core regulatory components of the MAPK cascade, MAPKKKs participate widely in the response of plants to abiotic stress (Shou et al., 2004; Shitamichi et al., 2013; Virk et al., 2015; Jia et al., 2016). To assess the expression profiles of PyMAPKKK genes under dehydration stress, the samples were treated with different degrees of dehydration and rehydration stress (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 2). Generally, the expression profiles of the 33 PyMAPKKKs under dehydrated conditions showed three different patterns. Cluster A showed that, with an increase in water loss, the expression of MAPKKKs was down-regulated. Following rehydration, yet their expression showed a different trendency, especially PyMAPKKK1, PyMAPKKK13, PyMAPKKK117, and PyMAPKKK24 with up-regulation expression pattern. The set of MAPKKK transcripts in Cluster B first increased in abundance at mild dehydration (50%) and then decreased, and then further increased following rehydration. PyMAPKKK transcripts in Cluster C showed that gene expression increased with an increase in water loss, with the highest expression level observed at 80% dehydration. After rehydration, expression level further decreased. In summary, the different gene family members exhibited great disparities under different dehydration and rehydration stresses. This phenomenon also exists in many higher plants (Wang et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2016). In addition, many cis-acting regulatory elements were identified in response to drought stress, clearly indicating that the PyMAPKKK gene family is involved in dehydration and rehydration, not only at a transcript level but also at a regulatory level.

Figure 5. Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of all 33 PyMAPKKK genes in different drought stress. Log2-transformed expression values were used to create the heat map. The red or blue color represent the higher or lower relative abundance of each transcript in each sample, compared to the median expression value of that gene in the whole sample set. Genes were clustered (A–C) according to their expression profiles. 30 represents water loss 30%, 50 represents water loss 50%, 80 represents water loss 80%, Re30min represents rehydration 30 min after water loss 80%.

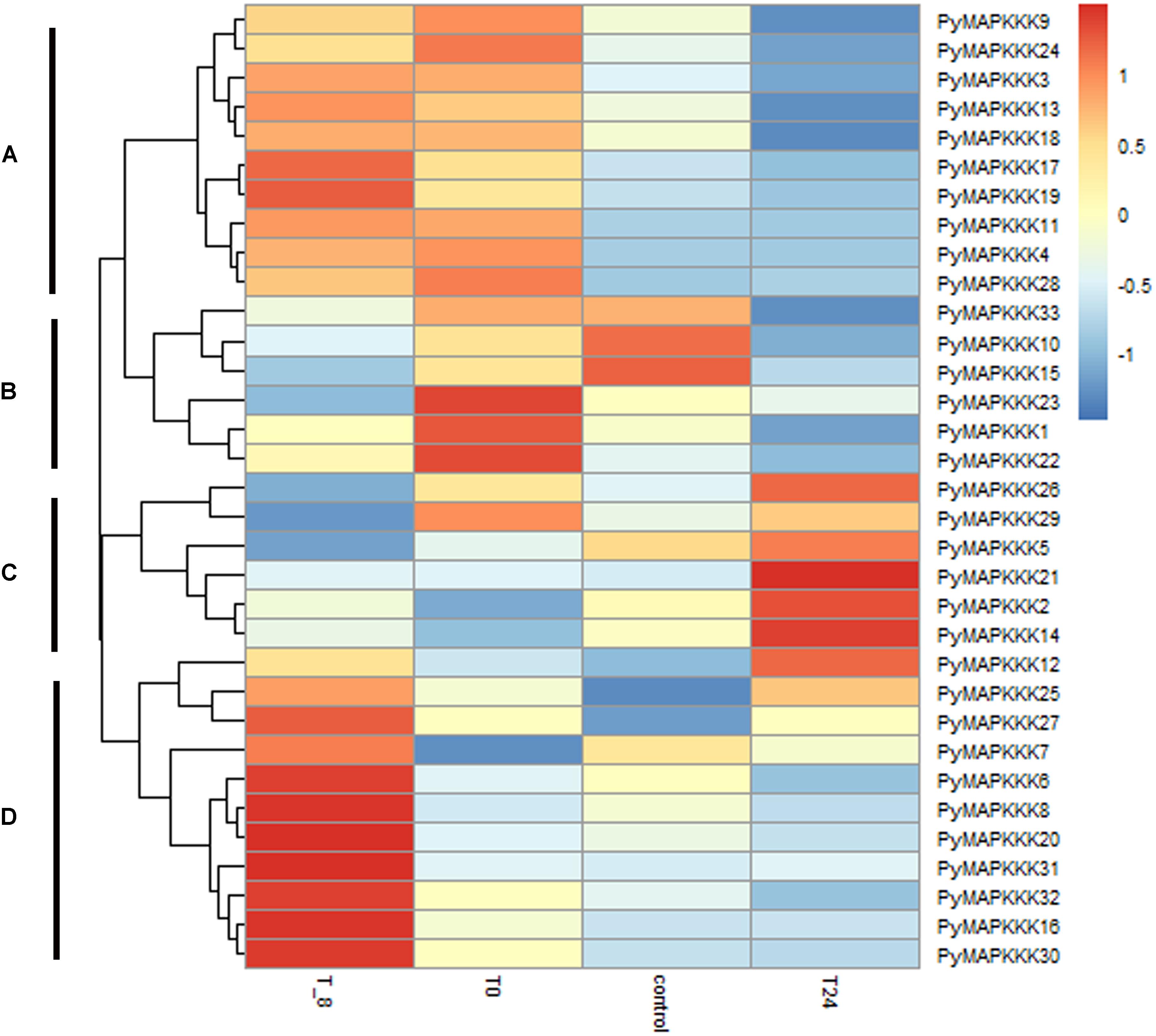

Figure 6. Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of all 33 PyMAPKKK genes in different temperature stress. Log2-transformed expression values were used to create the heat map. The red or blue color represent the higher or lower relative abundance of each transcript in each sample, compared to the median expression value of that gene in the whole sample set. Genes were clustered (A–D) according to their expression profiles.T_8 represent under –8°C temperature stress, T0 represent under 0°C temperature stress, T24 represent under 24°C temperature stress, control represents the material cultured at 10°C.

As an intertidal zone species, the thalli of P. yezoensis are exposed to air during tidal changes and endure dramatic changes in temperature, which fluctuates from 10 to 20°C. To evaluate the role of PyMAPKKK genes under temperature stress, their expression was analyzed under different temperature stress treatments. The expression profile of PyMAPKKK genes under temperature conditions is provided in Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 3. Overall, it is evident that the different gene members differ in their sensitivity to different temperature stresses. The expression profiles could be grouped into four main clusters: cluster A showed that high temperature could inhibit some PyMAPKKK gene expression, while low temperature induced PyMAPKKK gene expression. Furthermore, with the decrease in temperature, the expression patterns of these genes also showed variable sensitivity; for example, the expression levels of PyMAPKKK17 and PyMAPKKK19 increased significantly at −8°C. In cluster B, extreme low temperature and high temperature dramatically inhibited the expression of some genes, particularly PyMAPKKK33, PyMAPKKK15, and PyMAPKKK10. In cluster C, high temperature (24°C) significantly induced gene expression, while low temperature inhibited gene expression to some extent. In contrast, in cluster D, only at an extremely low temperature (−8°C) did the expression of this set of genes increase significantly, while no significant changes were observed under the other temperature stresses. Many studies in higher plants have indicated the role of MAPKs in temperature stress, including low temperature and high temperature (Teige et al., 2004; Sinha et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2014; Jia et al., 2016). Furthermore, as observed with drought-related cis-regulatory elements, some PyMAPKKK genes also contained elements related to temperature, such as the LTR motif, which further confirmed that PyMAPKKs respond to low and high temperature at transcript and regulatory levels, exhibiting diverse expression patterns.

In addition to the differential expression patterns of gene members under a single stress factor, we also found that the same gene member could respond to more than one stress. For example, PyMAPKKK12, PyMAPKKK30, and PyMAPKKK31 were up-regulated under drought stress and were also specifically expressed under extreme cold stress. In higher plants, paralogous genes show similar or different expression profiles responding to the same stressors; for example, among the MAPKKK genes belonging to the Raf family in bread wheat, three genes showed specific expression under salt stress, while another two genes were specifically expressed under drought stress (Wang et al., 2014, 2016a). This phenomenon was also observed in the present study. PyMAPKKK4/PyMAPKKK11/PyMAPKKK13 and PyMAPKKK1/PyMAPKKK2/PyMAPKKK19 showed similar expression patterns under cold stress and drought stress treatments, while PyMAPKKK10/PyMAPKKK17 and PyMAPKKK10/PyMAPKKK19 exhibited different expression patterns under the same stress treatments. This suggested that different paralogous genes in the same gene family experienced different selective pressures during evolution, and their functions show convergence or differentiation in stress factor adaptation. Regardless, these stress-induced MAPKKK genes still are helpful for further revealing the roles of PyMAPKKKs in the response of P. yezoensis to diverse stress processes.

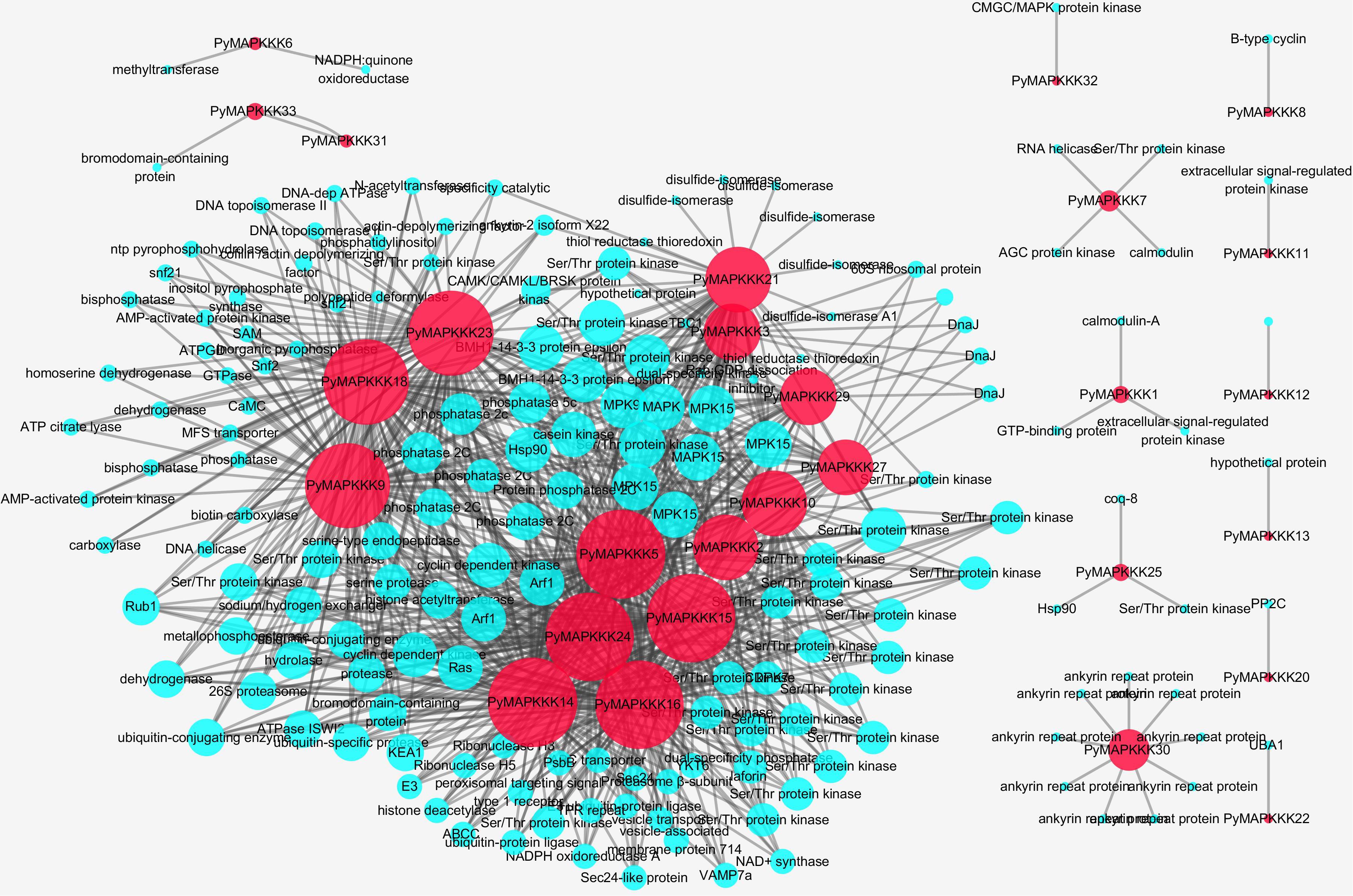

Regulatory Network Between PyMAPKKK Genes and Other P. yezoensis Genes

To understand the interaction between PyMAPKKKs and other P. yezoensis genes, their regulatory networks were predicted using the STRING database and local BLAST (Figure 7). A total of 28 PyMAPKKKs interacted with 965 proteins, while five PyMAPKKKs (PyMAPKKK4, PyMAPKKK17, PyMAPKKK19, PyMAPKKK26, and PyMAPKKK28) did not interact with any proteins, suggesting that PyMAPKKKs are widely involved in regulatory networks and metabolic processes in P. yezoensis.

Figure 7. The interaction network of PyMAPKKK genes in P. yezoensis. The red circle identifies PyMAPKKKs, the blue circle identifies interacted genes with PyMAPKKKs.

Among these interacting proteins, very few interacted with MEKKK subfamily members (PyMAPKKK11/PyMAPKKK21). PyMAPKKK11 only interacted with an extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase, and PyMAPKKK21 was predicted to interact with a hypothetical protein. In the ZIK subfamily, 66 proteins were predicted to interact with three ZIK members (PyMAPKKK1, PyMAPKKK2, PyMAPKKK10 and PyMAPKKK13), among which 52 proteins were Ser/Thr protein kinases. Other predicted proteins included MAPK, ADP-ribosylation factors, and heat shock proteins. Another two ZIK members (PyMAPKKK17 and PyMAPKKK19) were predicted to have no interaction. In the largest Raf subfamily, among the interacted proteins, the majority of proteins were protein kinases (Ser/Thr protein kinase, MAPK, and protein phosphatase 2C), followed by ubiquitin related enzymes or proteins (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, ubiquitin-like protein, ubiquitin-protein ligase E3, and ubiquitin-specific protease).

Of the total predicted interacting proteins, Ser/Thr kinases were the most abundant, followed by MAPKs. Ser/Thr protein kinases, believed to be the predominant protein kinases in eukaryotes, function in signal transduction related to various stress responses by catalyzing protein phosphorylation (Pereira et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2017). Therefore, Ser/Thr kinases may act as an upstream switch of PyMAPKKK to activate the MAPK signaling pathway of P. yezoensis by phosphorylating PyMAPKKK. In this research, 12 PyMAPKKKs were predicted to interact with MAPK, among which five PyMAPKKKs (PyMAPKKK2, PyMAPKKK3, PyMAPKKK5, and PyMAPKKK9) each interacted with seven PyMAPKs. A previous experiment demonstrated that OMTK1 in alfalfa interacts with MMK3 to form a complex involved in hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death (Nakagami et al., 2004). Furthermore, we found that four MAPKKKs (PyMAPKKK9, PyMAPKKK21, PyMAPKKK23, and PyMAPKKK24) interacted with both the 14-3-3 protein and protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C), and thus the activity of the four PyMAPKKKs may be regulated by 14-3-3 and PP2C. A point mutation experiment in HEK293 Epstein–Bar nuclear antigen (EBNA) cells showed that the 14-3-3 is associated with MEKK3 phosphorylation and can prevent dephosphorylation by PP2A (Fritz et al., 2006). In addition, PyMAPKKK2 and PyMAPKKK14 were predicted to interact with Hsp90 and E3 ubiquitin ligase, and the transcriptome expression profile also showed that their expression was up-regulated at 24°C. Further experiments are thus required to evaluate whether they interact to establish a pathway in response to high temperature stress. In A. thaliana, ZEITLUPE E3 ubiquitin ligase can interact with HSP90 to lead to proteasomal degradation, and further enhance the plants resistance to high temperature (Gil et al., 2017).

Interestingly, we also found some new proteins that interacted with PyMAPKKKs, such as histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC), which interacted with PyMAPKKK14 and PyMAPKKK24. Studies have demonstrated that HAT and HDAC contain nuclear receptor complexes that can modify the chromatin structure through binding the promoter of target genes and thus regulate their transcription through the MEK/ERK1/2 pathway (Zassadowski et al., 2012). The manner in which PyMAPKKK14 and PyMAPKKK24 phosphorylate HAT and HDAC to target the substrate and regulate gene transcription requires further experimental validation. Furthermore, PyMAPKKK2 interacted with a calcium dependent protein kinase, and 10 PyMAPKKKs interacted with casein kinase. As is well-known, calcium dependent protein kinases and casein kinases are Ser/Thr-selective enzymes that function as regulators of signal transduction pathways in most eukaryotes (Knippschild et al., 2005; Valmonte et al., 2014). This indicated that a cross-link signaling pathway existed in P. yezoensis in response to environment stress.

GO functional enrichment analysis was performed to evaluate the potential functions of the predicted genes. The results showed that a total of 606 interacting proteins were enriched to GO terms, involved in diverse modules related to biological processes (43%), molecular functions (30%), and cellular components (27%) (Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4). In the biological process category, the ZIK genes interacting with proteins were significantly enriched in metabolic processes, cellular processes, and single-organism processes, and the MEKK and Raf genes were mostly enriched in cellular processes and metabolic processes. In the cellular component category, the MEKK and Raf genes interacting with proteins were significantly enriched in cell part, while none within the ZIK subfamily were enriched in this term. In molecular function category, the MEKK, Raf, and ZIK genes interacting with proteins were all enriched in binding protein and catalytic activity. It has been shown that most MAPKKK sequences consist of long C-terminal regions with a catalytic domain that interact with other signaling molecules to regulate their function and direct their activity in MAPK pathways (Wu et al., 1999).

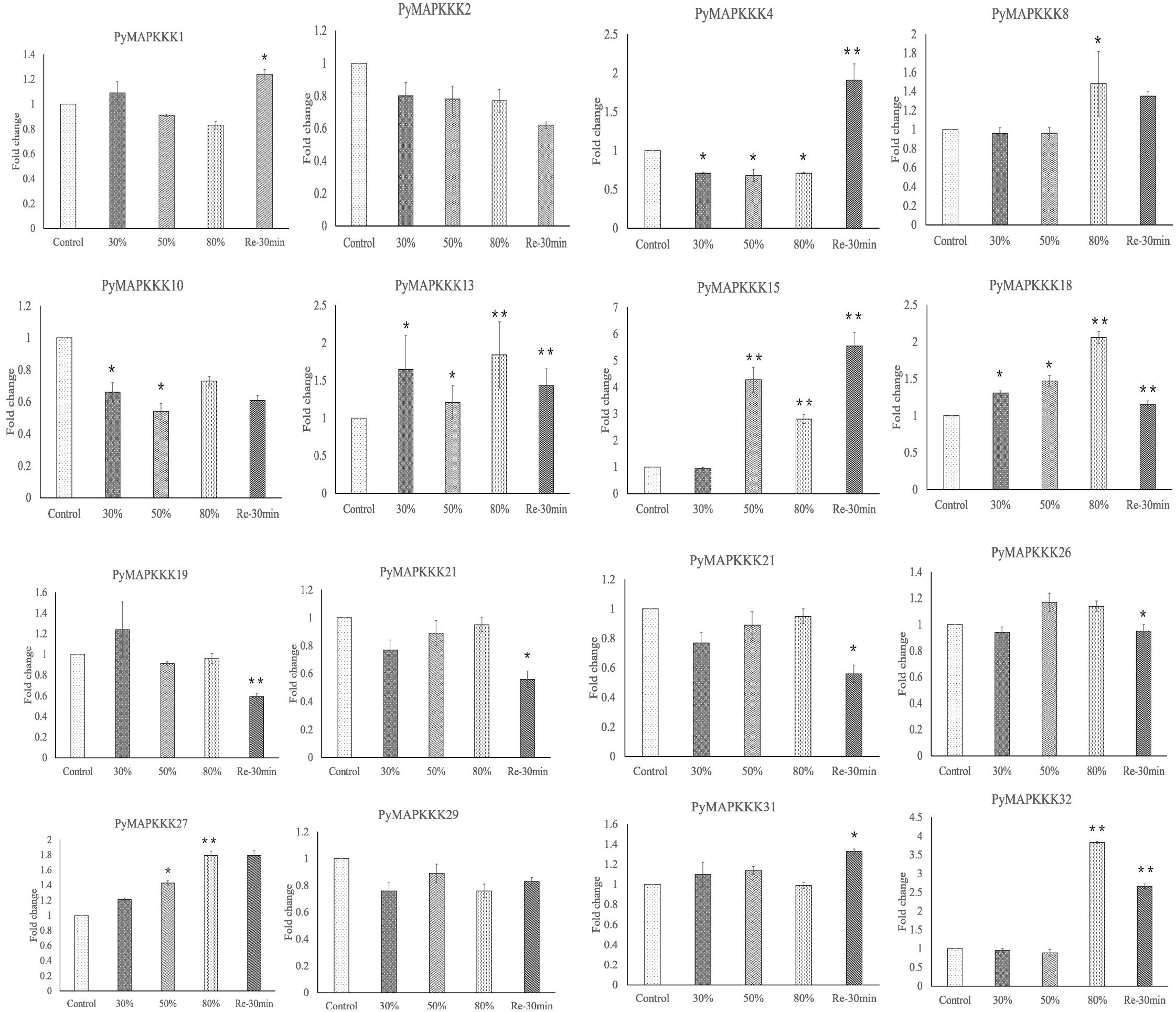

Validation of the Expression of PyMAPKKKs by qRT-PCR Analysis

Gene expression profiles provide the important clue for understanding the function of PyMAPKKKs genes responding to abiotic stress. To further verify the expression patterns of these PyMAPKKKs, 16 genes with significant differences were selected to detect their expression patterns through qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 8). Among them, 15 genes showed highly consistent with those using RNA-seq except from PyMAPKKK4. These results further suggested PyMAKKK were involved in dehydration/rehydration-stress and can be as the candidates for further studying their function in Pyropia abiotic response.

Figure 8. Validation of the expression level of PyMAPKKKs by qRT-PCR analysis. Fold changes in gene expression are shown in terms of log2-fold. Bars show means ± SE of three biological replicates. * and ** means significant difference.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank WMLA00000000, PRJNA236059, and PRJNA401507.

Author Contributions

FK and YM designed and supervised the experiments, and improved the manuscript. MC and NL performed the bioinformatic analysis. MC conducted the qRT-PCR analysis. BS prepared the samples. MS improved the manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 41976146 and 31672641) and Shandong Province Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2019GHY112008).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2020.00193/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Phylogenetic tree of MAPKKK proteins in red algae. The tree was constructed based on a complete protein sequence alignment by the ML method with bootstrapping analysis (2000 replicates).

FIGURE S2 | Gene ontology (GO) enrichment of interact genes with PyMAPKKKs. The abscissa represents the function of the gene and the ordinate represents the number of genes.

TABLE S1 | Cis-regulatory elements found in the promoters of 33 PyMAPKKK genes.

TABLE S2 | FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) values of the PyMAPKKK gene under water stress (drought and rehydration).

TABLE S3 | FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) values of the PyMAPKKK gene under temperature stress (heat and cold).

TABLE S4 | GO (Gene ontology) enrichment of PyMAPKKKs.

Footnotes

- ^ http://hmmer.org/download.html

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi

- ^ http://pfam.xfam.org/

- ^ http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/

- ^ https://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html

- ^ http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/

- ^ http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/

- ^ https://string-db.org/cgi/download.pl?UserId=Lfn1HLLUvpmT&sessionId=I43QP8bDcvuZ

- ^ http://www.omicshare.com/tools/Home/Index/index.html

References

Aravind, L., and Koonin, E. V. (1999). Gleaning non-trivial structural, functional and evolutionary information about proteins by iterative database searches. J. Mol. Biol. 287, 1023–1040. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2653

Asai, T., Tena, G., Plotnikova, J., Willmann, M. R., Chiu, W.-L., Gomez-Gomez, L., et al. (2002). MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 415, 977–983. doi: 10.1038/415977a

Benhamman, R., Bai, F., Drory, S., Loubert-Hudon, A., Ellis, B., and Matton, D. (2017). The Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 20 (MKKK20) acts upstream of MKK3 and MPK18 in two separate signaling pathways involved in root microtubule functions. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1352. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01352

Colcombet, J., and Hirt, H. (2008). Arabidopsis MAPKs: a complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem. J. 413, 217–226. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080625

Collén, J., Porcel, B., Carré, W., Ball, S. G., Chaparro, C., Tonon, T., et al. (2013). Genome structure and metabolic features in the red seaweed Chondrus crispus shed light on evolution of the Archaeplastida. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5247–5252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221259110

Danquah, A., Zélicourt, A., Boudsocq, M., Neubauer, J., Frei Dit Frey, N., Leonhardt, N., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of an ABA-activated MAP kinase cascade in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 82, 232–244. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12808

Dolan-O’Keefe, M., and Ferl, R. J. (2000). “Adh as a model for analysis of the integration of stress response regulation in plants,” in Plant Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses in Agriculture: Role of Genetic Engineering, eds J. H. Cherry, R. D. Locy, and A. Rychter (Berlin: Springer), 269–284. doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-4323-3_19

Feng, K., Liu, F., Zou, J., Xing, G., Deng, P., Song, W., et al. (2016). Genome-wide identification, evolution, and co-expression network analysis of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases in Brachypodium distachyon. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1400. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01400

Fritz, A., Brayer, K. J., Mccormick, N., Adams, D. G., Wadzinski, B. E., and Vaillancourt, R. R. (2006). Phosphorylation of serine 526 is required for MEKK3 activity, and association with 14-3-3 blocks dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6236–6245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m509249200

Gao, L., and Xiang, C.-B. (2008). The genetic locus At1g73660 encodes a putative MAPKKK and negatively regulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 125–134. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9306-8

Gao, M., Liu, J., Bi, D., Zhang, Z., Cheng, F., Chen, S., et al. (2008). MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2 and MPK4 function together in a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to regulate innate immunity in plants. Cell Res. 18, 1190–1198. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.300

Gil, K.-E., Kim, W.-Y., Lee, H.-J., Faisal, M., Saquib, Q., Alatar, A. A., et al. (2017). ZEITLUPE contributes to a thermoresponsive protein quality control system in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 29, 2882–2894. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00612

Gorina, S., and Pavletich, N. P. (1996). Structure of the p53 tumor suppressor bound to the ankyrin and SH3 domains of 53BP2. Science 274, 1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.1001

Hamel, L.-P., Nicole, M.-C., Sritubtim, S., Morency, M.-J., Ellis, M., Ehlting, J., et al. (2006). Ancient signals: comparative genomics of plant MAPK and MAPKK gene families. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.02.007

Hamel, L.-P., Sheen, J., and Séguin, A. (2014). Ancient signals: comparative genomics of green plant CDPKs. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.10.009

Han, B., Kim, K., Lee, S., Jeong, K., Cho, J., Noh, K., et al. (2012). Helical repeat structure of apoptosis inhibitor 5 reveals protein-protein interaction modules. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 10727–10737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.317594

Hu, W., Wang, L., Tie, W., Yan, Y., Ding, Z., Liu, J., et al. (2016). Genome-wide analyses of the bZIP family reveal their involvement in the development, ripening and abiotic stress response in banana. Sci. Rep. 6:30203. doi: 10.1038/srep30203

Jia, H., Hao, L., Guo, X., Liu, S., Yan, Y., and Guo, X. (2016). A Raf-like MAPKKK gene, GhRaf19, negatively regulates tolerance to drought and salt and positively regulates resistance to cold stress by modulating reactive oxygen species in cotton. Plant Sci. 252, 267–281. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.07.014

Jiang, M., Wen, F., Cao, J., Li, P., She, J., and Chu, Z. (2015). Genome-wide exploration of the molecular evolution and regulatory network of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades upon multiple stresses in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genomics 16:228. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1452-1

Jin, H., Axtell, M. J., Dahlbeck, D., Ekwenna, O., Zhang, S., Staskawicz, B., et al. (2002). NPK1, an MEKK1-like mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, regulates innate immunity and development in plants. Dev. Cell 3, 291–297. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00205-8

Jonak, C., Ökrész, L., Bögre, L., and Hirt, H. (2002). Complexity, cross talk and integration of plant MAP kinase signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 415–424. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00285-6

Kim, J.-M., Woo, D.-H., Kim, S.-H., Lee, S.-Y., Park, H.-Y., Seok, H.-Y., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis MKKK20 is involved in osmotic stress response via regulation of MPK6 activity. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 217–224. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1157-0

Knippschild, U., Gocht, A., Wolff, S., Huber, N., Löhler, J., and Stöter, M. (2005). The casein kinase 1 family: participation in multiple cellular processes in eukaryotes. Cell. Signal. 17, 675–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.12.011

Kong, F., Wang, J., Cheng, L., Liu, S., Wu, J., Peng, Z., et al. (2012). Genome-wide analysis of the mitogen-activated protein kinase gene family in Solanum lycopersicum. Gene 499, 108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.048

Kong, F., Yang, X., Li, N., Zhao, H., and Mao, Y. (2017). Identification and characterization of PyAQPs from Pyropia yezoensis, which are involved in tolerance to abiotic stress. J. Appl. Phycol. 29, 1695–1706. doi: 10.1007/s10811-016-1042-x

Kong, X., Lv, W., Zhang, D., Jiang, S., Zhang, S., and Li, D. (2013). Genome-wide identification and analysis of expression profiles of maize mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase. PLoS One 8:e57714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057714

Lescot, M., Déhais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., Van De Peer, Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Li, C., Kong, F., Sun, P., Bi, G., Li, N., Mao, Y., et al. (2018). Genome-wide identification and expression pattern analysis under abiotic stress of mitogen-activated protein kinase genes in Pyropia yezoensis. J. Appl. Phycol. 30, 2561–2572. doi: 10.1007/s10811-018-1412-7

Li, Z., Wang, W., Li, G., Guo, K., Harvey, P., Chen, Q., et al. (2016). MAPK-mediated regulation of growth and essential oil composition in a salt-tolerant peppermint (Mentha piperita L.) under NaCl stress. Protoplasma 253, 1541–1556. doi: 10.1007/s00709-015-0915-1

Liu, Y., Schiff, M., and Dinesh-Kumar, S. (2004). Involvement of MEK1 MAPKK, NTF6 MAPK, WRKY/MYB transcription factors, COI1 and CTR1 in N-mediated resistance to tobacco mosaic virus. Plant J. 38, 800–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02085.x

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Maindonald, J. H. (2008). Using R Data Analysis and Graphics: Introduction, Code and Commentary. Canberra: Australian National University.

Meng, X., Wang, H., He, Y., Liu, Y., Walker, J. C., Torii, K. U., et al. (2012). A MAPK cascade downstream of ERECTA receptor-like protein kinase regulates Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture by promoting localized cell proliferation. Plant Cell 24, 4948–4960. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104695

Meng, X., and Zhang, S. (2013). MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 245–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314

Mészáros, T., Helfer, A., Hatzimasoura, E., Magyar, Z., Serazetdinova, L., Rios, G., et al. (2006). The Arabidopsis MAP kinase kinase MKK1 participates in defence responses to the bacterial elicitor flagellin. Plant J. 48, 485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2006.02888.x

Mishra, N. S., Tuteja, R., and Tuteja, N. (2006). Signaling through MAP kinase networks in plants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 452, 55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.05.001

Nakagami, H., Kiegerl, S., and Hirt, H. (2004). OMTK1, a novel MAPKKK, channels oxidative stress signaling through direct MAPK interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26959–26966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m312662200

Nakamura, Y., Sasaki, N., Kobayashi, M., Ojima, N., Yasuike, M., Shigenobu, Y., et al. (2013). The first symbiont-free genome sequence of marine red alga, Susabi-nori (Pyropia yezoensis). PLoS One 8:e57122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057122

Ning, J., Li, X., Hicks, L. M., and Xiong, L. (2010). A Raf-like MAPKKK gene DSM1 mediates drought resistance through reactive oxygen species scavenging in rice. Plant Physiol. 152, 876–890. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.149856

Pan, J., Zha, Z., Zhang, P., Chen, R., Ye, C., and Ye, T. (2017). Serine/threonine protein kinase PpkA contributes to the adaptation and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 113, 5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.10.017

Parages, M. L., Capasso, J. M., Meco, V., and Jiménez, C. (2012). A novel method for phosphoprotein extraction from macroalgae. Bot. Mar. 55, 261–267. doi: 10.1515/bot-2011-0051

Parages, M. L., Capasso, J. M., Niell, F. X., and Jiménez, C. (2014). Responses of cyclic phosphorylation of MAPK-like proteins in intertidal macroalgae after environmental stress. J. Plant Physiol. 171, 276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.08.005

Pereira, S. F., Goss, L., and Dworkin, J. (2011). Eukaryote-like serine/threonine kinases and phosphatases in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 192–212. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00042-10

Popescu, S. C., Popescu, G. V., Bachan, S., Zhang, Z., Gerstein, M., Snyder, M., et al. (2009). MAPK target networks in Arabidopsis thaliana revealed using functional protein microarrays. Genes Dev. 23, 80–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.1740009

Rao, K. P., Richa, T., Kumar, K., Raghuram, B., and Sinha, A. K. (2010). In silico analysis reveals 75 members of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family in rice. DNA Res. 17, 139–153. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq011

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., Van Der Mark, P., Ayres, D., Darling, A., Höhna, S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029

Sedgwick, S. G., and Smerdon, S. J. (1999). The ankyrin repeat: a diversity of interactions on a common structural framework. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01426-7

Shitamichi, N., Matsuoka, D., Sasayama, D., Furuya, T., and Nanmori, T. (2013). Over-expression of MAP3Kδ4, an ABA-inducible Raf-like MAP3K that confers salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. 30, 111–118. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.13.0108a

Shou, H., Bordallo, P., and Wang, K. (2004). Expression of the Nicotiana protein kinase (NPK1) enhanced drought tolerance in transgenic maize. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1013–1019. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh129

Sinha, A. K., Jaggi, M., Raghuram, B., and Tuteja, N. (2011). Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants under abiotic stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 196–203. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.2.14701

Sun, P., Mao, Y., Li, G., Cao, M., Kong, F., Wang, L., et al. (2015). Comparative transcriptome profiling of Pyropia yezoensis (Ueda) MS Hwang & HG Choi in response to temperature stresses. BMC Genomics 16:463.

Szklarczyk, D., Franceschini, A., Kuhn, M., Simonovic, M., Roth, A., Minguez, P., et al. (2010). The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973

Teige, M., Scheikl, E., Eulgem, T., Dóczi, R., Ichimura, K., Shinozaki, K., et al. (2004). The MKK2 pathway mediates cold and salt stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 15, 141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.023

Trapnell, C., Roberts, A., Goff, L., Pertea, G., Kim, D., Kelley, D. R., et al. (2012). Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7, 562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016

Valmonte, G. R., Arthur, K., Higgins, C. M., and Macdiarmid, R. M. (2014). Calcium-dependent protein kinases in plants: evolution, expression and function. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 551–569. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct200

Virk, N., Li, D., Tian, L., Huang, L., Hong, Y., Li, X., et al. (2015). Arabidopsis Raf-Like mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene Raf43 is required for tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses. PLoS One 10:e0133975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133975

Wang, G., Lovato, A., Polverari, A., Wang, M., Liang, Y.-H., Ma, Y.-C., et al. (2014). Genome-wide identification and analysis of mitogen activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera). BMC Plant Biol. 14:219. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0219-1

Wang, H., Ngwenyama, N., Liu, Y., Walker, J. C., and Zhang, S. (2007). Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 63–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048298

Wang, J., Pan, C., Wang, Y., Ye, L., Wu, J., Chen, L., et al. (2015). Genome-wide identification of MAPK, MAPKK, and MAPKKK gene families and transcriptional profiling analysis during development and stress response in Cucumber. BMC Genomics 16:386. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1621-2

Wang, M., Yue, H., Feng, K., Deng, P., Song, W., and Nie, X. (2016a). Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expressional profiles of mitogen activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genomics 17:668. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2993-7

Wang, Y., Bi, X., Chu, Q., and Xu, T. (2016b). Discovery of toll-like receptor 13 exists in the teleost fish: Miiuy croaker (Perciformes, Sciaenidae). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 61, 25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.03.005

Watanabe, K., Homayouni, A., Gu, L., Huang, K., Ho, T., and Shen, Q. (2017). Transcriptomic analysis of rice aleurone cells identified a novel abscisic acid response element. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 2004–2016. doi: 10.1111/pce.13006

Wrzaczek, M., and Hirt, H. (2001). Plant MAP kinase pathways: how many and what for? Biol. Cell 93, 81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(01)01121-2

Wu, C., Leberer, E., Thomas, D., and Whiteway, M. (1999). Functional characterization of the interaction of Ste50p with Ste11p MAPKKK in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2425–2440. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.7.2425

Wu, J., Wang, J., Pan, C., Guan, X., Wang, Y., Liu, S., et al. (2014). Genome-wide identification of MAPKK and MAPKKK gene families in tomato and transcriptional profiling analysis during development and stress response. PLoS One 9:e103032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103032

Xiong, L., and Yang, Y. (2003). Disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance in rice are inversely modulated by an abscisic acid–inducible mitogen-activated protein kinase. Plant Cell 15, 745–759. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008714

Xu, J., and Zhang, S. (2015). Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in signaling plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.10.001

Zassadowski, F., Rochette-Egly, C., Chomienne, C., and Cassinat, B. (2012). Regulation of the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors by the MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. Cell. Signal. 24, 2369–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.08.003

Zhang, A., Jiang, M., Zhang, J., Tan, M., and Hu, X. (2006). Mitogen-activated protein kinase is involved in abscisic acid-induced antioxidant defense and acts downstream of reactive oxygen species production in leaves of maize plants. Plant Physiol. 141, 475–487. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.075416

Zhang, X., Xu, X., Yu, Y., Chen, C., Wang, J., Cai, C., et al. (2016). Integration analysis of MKK and MAPK family members highlights potential MAPK signaling modules in cotton. Sci. Rep. 6:29781. doi: 10.1038/srep29781

Zhao, C., Wang, P., Si, T., Hsu, C., Wang, L., Zayed, O., et al. (2017). MAP kinase cascades regulate the cold response by modulating ICE1 protein stability. Dev. Cell 43, 618.e5–629.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.024

Keywords: P. yezoensis, MAPKKK family, gene structure, cis-regulatory element, expression profiles, interactome network

Citation: Kong F, Cao M, Li N, Sun B, Sun M and Mao Y (2020) Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogeny, and Expressional Profiles of the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase (MAPKKK) Gene Family in Pyropia yezoensis. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:193. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00193

Received: 27 November 2019; Accepted: 12 March 2020;

Published: 08 April 2020.

Edited by:

Pei-Yuan Qian, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong KongReviewed by:

Jian-Wen Qiu, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong KongJerome Hui, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China

Copyright © 2020 Kong, Cao, Li, Sun, Sun and Mao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fanna Kong, Zm5rb25nQG91Yy5lZHUuY24=; Yunxiang Mao, eXhtYW9Ab3VjLmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Fanna Kong

Fanna Kong Min Cao

Min Cao Na Li1,2

Na Li1,2