- 1Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

- 2Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

- 3HYDRA Marine Sciences GmbH, Sinzheim, Germany

- 4HYDRA, Elba Field Station, Campo nell’Elba, Italy

We report primary production and respiration of Posidonia oceanica meadows determined with the non-invasive aquatic eddy covariance technique. Oxygen fluxes were measured in late spring at an open-water meadow (300 m from shore), at a nearshore meadow (60 m from shore), and at an adjacent sand bed. Despite the oligotrophic environment, the meadows were highly productive and highly autotrophic. Net ecosystem production (54 to 119 mmol m–2 d–1) was about one-half of gross primary production. In adjacent sands, net primary production was a tenth- to a twentieth smaller (4.6 mmol m–2 d–1). Thus, P. oceanica meadows are an oasis of productivity in unproductive surroundings. During the night, dissolved oxygen was depleted in the open-water meadow. This caused a hysteresis where oxygen production in the late afternoon was greater than in the morning at the same irradiance. Therefore, for accurate measurements of diel primary production and respiration in this system, oxygen must be measured within the canopy. Generally, these measurements demonstrate that P. oceanica meadows fix substantially more organic carbon than they respire. This supports the high rate of organic carbon accumulation and export for which the ecosystem is known.

Introduction

Seagrass meadows are highly productive coastal habitats (Bay, 1984; Frankignoulle and Bouquegneau, 1987) that can be a net sink for atmospheric CO2 (Duarte et al., 2010). Net production commonly exceeds 1 kg C dry weight m–2 year–1 (Duarte and Chiscano, 1999). Seagrass meadows worldwide are threatened by eutrophication, turbidity, climate change, and other factors (Orth et al., 2006). Seagrass productivity for a given meadow is determined by the balance of photosynthesis and respiration. This balance is determined by the response to environmental factors such as nutrient availability (Short, 1987; Powell et al., 1989; Udy and Dennison, 1997), temperature (Bulthuis, 1987; Alcoverro et al., 1995; Collier and Waycott, 2014), water velocity (Fonseca and Kenworthy, 1987; Thomas et al., 2000; Peralta et al., 2006), CO2 availability (Zimmerman and Kremer, 1986; Koch, 1994), and irradiance (Dennison and Alberte, 1985; Peralta et al., 2002; Ralph et al., 2007). Among these factors, the photosynthetic response of seagrasses to irradiance is fundamental. However, the response of a complete meadow is not documented by in situ studies. Our understanding of the photosynthetic response of seagrass to irradiance is generally based on incubations of individual leaves or leaf fragments. High levels of irradiance saturate photosynthesis in these tissues (e.g., Pirc, 1986). In natural seagrass meadows, however, self-shading may allow seagrasses to utilize light up to peak midday summertime irradiance, without saturation of photosynthesis (Sand-Jensen et al., 2007). The interaction of steep solute and velocity gradients around seagrass leaves may also alter nutrient availability (Thomas et al., 2000) and photosynthetic rates (Koch, 1994). Additionally, because of temporal and spatial variability in metabolism, scaling up from incubations of leaves and leaf tissues is problematic. Therefore, in situ techniques are needed to improve our understanding of the response of seagrass meadows to changes in the drivers of metabolism.

The two primary techniques that have been used to quantify seagrass productivity in situ are benthic chambers and the diel-change technique (Odum, 1956; Howarth and Michaels, 2000). The diel-change technique makes measurements under true, in situ conditions, but it has substantial uncertainties. The upstream contributing area can be hundreds to thousands of meters in length (Reichert et al., 2009), diminishing the precision of measurement of metabolism in a discrete habitat of interest. Diel-change measurements of metabolism can also be biased by changes in circulation, by differing habitat types in the contributing area, by stratification, and by calculation of gas exchange at the air-water interface (Staehr et al., 2010; Long et al., 2015a). Conversely, benthic chambers allow measurements of community respiration and primary production over a discrete area with no gas-transfer correction. However, chambers are invasive. They are inserted into sediments, cutting through below-ground tissues and sediment layers. They also alter the light environment, prohibit hydrodynamic exchange, and accumulate the products of metabolism, potentially altering fluxes (Campbell and Fourqurean, 2011; Olivé et al., 2016). The effect of chambers on benthic metabolism has been studied in detail in permeable sediment. Organic matter mineralization in sands is enhanced by pore water advection (Huettel and Gust, 1992; Boudreau et al., 2001) with the result that oxygen uptake can be a function of the chamber stirring speed (Forster et al., 1996). Therefore, metabolism of sands determined with benthic chambers may differ from metabolism determined under dynamic in situ conditions (e.g., Berg et al., 2013).

An alternate in situ metabolism approach is the eddy covariance technique (Berg et al., 2003). Oxygen fluxes are quantified as the mean product of the fluctuating components of vertical velocity and oxygen concentration in turbulent flow over the habitat of interest. The resulting fluxes have a contributing area of tens of meters square (Berg et al., 2007). Fluxes are measured at high frequency (e.g., 5 Hz), allowing the user to quantify the diel photosynthetic response to light, among other variables. The technique has been used to quantify metabolism of Zostera marina, Thalassia testudinum, and Zostera noltii (Rheuban et al., 2014a, b; Long et al., 2015b; Lee et al., 2017; Attard et al., 2019; Berg et al., 2019). Among the discoveries is that over an annual cycle, Zostera marina meadows are heterotrophic or negligibly autotrophic (Rheuban et al., 2014a; Attard et al., 2019) although by particle-trapping they may still act as a net carbon sink (Greiner et al., 2013).

In contrast to many other seagrass species, P. oceanica meadows can be highly autotrophic, with a median ratio of community gross primary production to respiration of 1.65 (Duarte et al., 2010). On a mass-specific basis, the primary productivity of P. oceanica relative to other seagrasses is low. However, P. oceanica maintains a high meadow productivity due to its high biomass (Ott, 1980; Bay, 1984). Posidonia oceanica has greater above-ground biomass than many other seagrass species (Duarte and Chiscano, 1999). Self-shading, caused by horizontal fronds at the top of their canopies, reduces light penetration into their canopies by 50% (Dalla Via et al., 1998). Below-ground biomass for the species is commonly five to ten times greater than other species (Duarte and Chiscano, 1999) leading to the formation of a dense, fibrous “matte” of intertwined roots, rhizomes, and leaf sheaths resulting from the production and accretion of this material within the meadow over time (Mateo et al., 1997). Organic matter may remain in mattes for thousands of years (Mateo et al., 1997; Serrano et al., 2012) contributing to the formation of significant carbon deposits (37 kg m–2 within the first meter; Fourqurean et al., 2012). Because our understanding of P. oceanica community metabolism is based primarily on benthic chamber work, the measured rates of production and respiration of the ecosystem may differ from those occurring under in situ conditions. The lack of true, in situ measurements also leaves us without a quantitative understanding of the photosynthetic response of the ecosystem to light, among other drivers.

The objective of this study was to quantify the primary production and respiration of Posidonia oceanica meadows. The resulting measurements were used to quantify net ecosystem metabolism (NEM) and investigate photosynthesis as a function of irradiance. We used the eddy covariance technique (Berg et al., 2003) to make these measurements under in situ illumination and hydrodynamic conditions. Measurements were made near the seasonal peak of carbon acquisition to quantify how the potential for NEM in this ecosystem compares to other seagrasses. To capture some diversity in the potential differences in primary production and respiration between meadows, we selected two meadows located at the same water depths but at different distances from shore. We studied one meadow in 2016, and the second meadow in 2017. In both years, the study was conducted in the month of May under similar environmental conditions. Additional measurements of primary production and respiration were made over nearby sands in 2017.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

The study was conducted in the NW Mediterranean Sea, at the island of Elba, Italy in the Tuscan Archipelago. The island is surrounded by P. oceanica beds from depths of 5 to 40 m. The meadow examined in the first year of the study (open-water) was located 300 m from the southwest corner of the island (42.7421 N, 10.1183 E). The meadow examined in the second year of the study (nearshore) was located 60 m from the north shore (42.8087 N, 10.1472 E). Both meadows were located at 13 m depth. At each meadow, eddy covariance oxygen fluxes were measured for 2 days. At the open-water seagrass meadow the 2 days were continuous from 15 to 18 May 2016. At the nearshore meadow, the measurement days (13 and 25 May 2017) were not continuous. Both seagrass meadows were visually dense (e.g., Figure 1), with 60-cm-tall canopies, and were exposed to low water velocities during the study period (<3 cm s–1, Table 1). Surficial sediments beneath the meadows were typical of P. oceanica; they were composed of fibrous mats of intertwined rhizomes and roots in excess of 20 cm thick. In addition to seagrass meadows, eddy covariance oxygen fluxes were also measured over a broad area of bare sands (100 m × 50 m) adjacent to the nearshore meadow over two nights and one day on 23 May 2017. Eddy covariance instruments were positioned approximately 50 m from the seagrass edge in the predominant, along-shore current direction.

Figure 1. Eddy covariance instruments at the open-water seagrass meadow at Elba, Italy in May of 2016. The velocimeter is upright, in titanium, with three receivers aligned toward the measurement volume. Aligned beside the measurement volume are a prototype sensor (results not included in this study), and the pencil-sized eddy covariance oxygen minisensor.

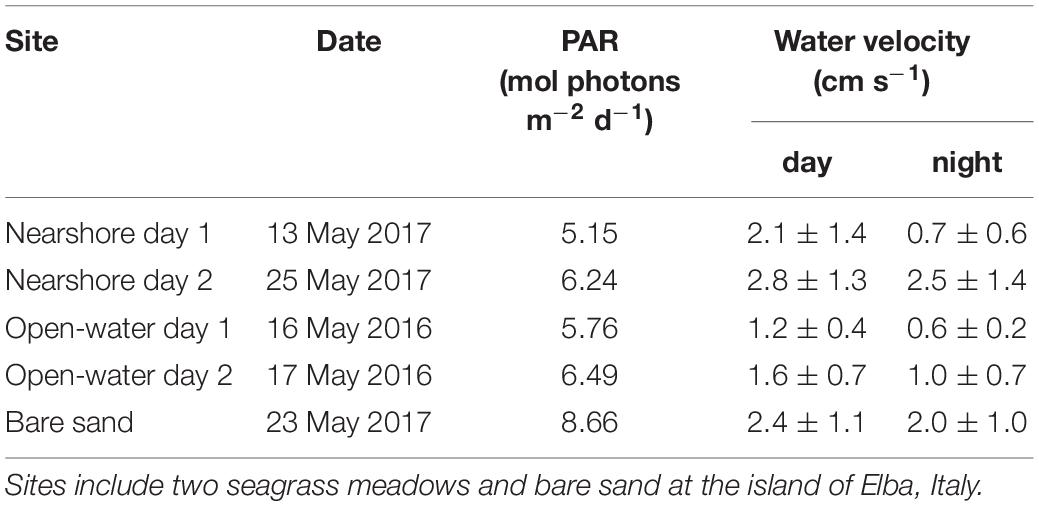

Table 1. Environmental conditions during oxygen flux measurements including integrated photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) and day/night water velocities (± s.d.) measured above the habitat of interest.

Eddy Covariance and Environmental Measurements

Water velocity for eddy covariance measurements was determined at 16 Hz with an acoustic Doppler velocimeter (ADV; Vector, Nortek AS). Oxygen concentration was determined at 5 Hz with high speed (t90 = 0.25 s) optode minisensors of 50 or 430 μm in diameter (PyroScience GmbH). Dissolved oxygen measurements were made by the manufacturer’s oxygen meter, which was placed in a submersible housing with an optical port for the fiber-optic cable of the minisensor. Optodes have been successfully used for eddy covariance measurements previously (Chipman et al., 2012; Berg et al., 2016) and they lack stirring sensitivity (Holtappels et al., 2015). Optodes were calibrated in air-saturated and anoxic water before and after each deployment. The instruments were mounted to a tripod frame with 4 cm-wide legs spaced 1.2 m apart. The sensors were aligned at a 40-degree angle to the velocimeter, and the tip located 2 cm from the edge of the velocimeter measuring volume. This distance was sufficient to minimize acoustic interference of velocity measurement in this low-backscatter environment. The legs of the frame were adjusted to allow for measurements at a height of about 0.3 m above the top of seagrass canopies (Figure 1) and 0.25 m over sands.

Multi-parameter probes that measured O2 concentration (RBR Ltd.) were mounted at heights of 0.2 m and 1.0 m above the seafloor at the open-water meadow. By an oversight, the lower probe was positioned 0.6 m above the seafloor for the deployments in year two at the nearshore meadow. This precluded within-canopy dissolved oxygen measurements at the nearshore meadow. A single eddy covariance instrument frame was used to collect all of the measurements made in this study. Irradiance was quantified with HOBO Pendant luminescence sensors (Onset Computer Corp.), cross-calibrated for photosynthetically active radiation (PAR, 400–700 nm) by a LI-192 (LI-COR, Inc.) sensor as demonstrated by Long et al. (2012). The instrument frame was deployed by divers at the research sites and was aligned to minimize tilt. The time series of mean O2 concentration variation recorded by the fast optodes reproduced those recorded by the O2 logger positioned above the canopy. Thus, fluctuations recorded by the fast optode were accurate.

Supporting measurements were made of nutrient concentrations at the open-water meadow in 2016. Water samples, collected 1 m above the bed by divers, were filtered over 0.2 μM and then frozen until analysis. Nutrient concentrations (NH4+, NO3–, PO43–) were determined with a segmented flow nutrient analyzer (QuAAttro, Seal Analytical GmbH). The detection limits of phosphate, nitrate, and ammonium were 0.010, 0.016, and 0.07 μmol L–1. Shoot density at each of the meadows was determined by divers using a negatively buoyant ring to define an area of 0.25 m2. Ten replicate measurements were made at random locations at each of the sites.

Eddy Covariance Calculations

The velocity and oxygen time series, recorded at 16 Hz by the ADV, were downsampled to the optode sampling frequency of 5 Hz and were processed similarly to the procedure described by Holtappels et al. (2013). The tilt of the ADV was corrected using the planar fit method by Wilczak et al. (2001). A running average with a window of 300 s was subtracted from the time series to calculate the fluctuating vertical velocity (w′) and O2 concentration (C′). At slow water velocities, a temporal offset of up to a few seconds can occur between the recording of an event’s velocity and its oxygen concentration (McGinnis et al., 2008). To account for this, the cross-correlation of w′ and C′ were calculated in hour-long intervals using stepwise time shifts to a maximum 4 s. The median time shift was 0.8 s. The time shift with the highest cross correlation coefficient was used to calculate the flux. The eddy covariance O2 flux (JEC) in the vertical direction was calculated as

where the overbar indicates averaging. Instantaneous fluxes () were added over time to calculate cumulative fluxes in hour-long intervals. Particle collision with the tip of O2 minisensors can cause erratic fluxes (e.g., Lorrai et al., 2010). We examined the dataset for spikes in the O2 data that co-occurred with abrupt changes in calculated fluxes. Few hour-long averaging intervals (4%) were affected and they were excluded from further analyses.

In a further step, we accounted for oxygen storage in the water layer between the measurement volume of the eddy covariance system and the sediment surface. In a first approximation, we assumed that the O2 concentration at the measurement volume represented the O2 concentration in the entire bottom layer. This assumes that there was no vertical oxygen gradient in the bottom layer. We made this correction according to Rheuban et al. (2014b).

where JEC is the eddy covariance flux, h is the height of the velocity measurement volume above the bed, and is the change in the O2 concentration at the measurement volume over time for each 1h interval. From these corrected fluxes, we infer hourly benthic biological O2 flux (Jbiotic). Where O2 production is negative there is benthic O2 consumption. Hourly fluxes are reported in diel units (mmol m–2 d–1) for calculation of diel metabolism.

The storage-corrected, hourly O2 fluxes were grouped by irradiance. Dark intervals were designated those that received <1% maximum diel irradiance. These were used to calculate respiration (R), gross primary production (GPP), and NEM in an approach similar to Hume et al. (2011). To accommodate datasets with observations in excess of 24 h, metabolic fluxes were calculated as

where Jbiotic dark is a nighttime flux of 1 h duration, Jbiotic light is a daytime flux of 1 h duration, and hlight and hdiel are the hours of daytime (14 during experimental measurements) and hours in a complete diel cycle (24). To examine the photosynthetic response of seagrass meadows to their changing light environment, photosynthesis-irradiance relationships were fit with a hyperbolic tangent function (Jassby and Platt, 1976) which was modified to account for respiration according to Rheuban et al. (2014a). The fit was calculated as

where Pmax is the maximum photosynthetic rate, Ik is the saturation irradiance, and RI is respiration. The irradiance at which net oxygen production equals zero is the irradiance compensation point (IC; Falkowski and Raven, 2013). To examine the effect of the open-water versus nearshore meadow on NEM we used a Student’s t-test at a significance level of p = 0.05. A separate Student’s t-test was performed to test if the mean seagrass meadow productivity was greater than that of nearshore sands.

Results

Environmental Conditions

During May of 2016 and May of 2017 a total of 139 h of eddy covariance fluxes were measured for the study. Percent areal coverage of P. oceanica in the meadows, estimated from plan-view underwater images, was high (95–99%) at both meadows. Shoot densities at the nearshore meadow (379 ± 56; uncertainty represents standard error, n = 10) were similar to the open-water meadow (434 ± 28, n = 10). Measurements were made on mostly sunny or completely sunny days. Photosynthetically active irradiance was similar above the seagrass meadows on measurement days (Table 1). Water velocities were lower at the open water meadow, and peaked during the day at both meadows. Water temperatures throughout the study periods across years were similar (17.4 to 18.8°C). Water column nutrients were determined in the water column above the open water meadow in 2016. N-nutrients were very depleted (the sum of NO3–, NO2– and NH4+ was 0.73 ± 1.0 μmol L–1, n = 7) and phosphates were below detection (0.01 μmol L–1).

Oxygen Storage in Seagrass Meadows

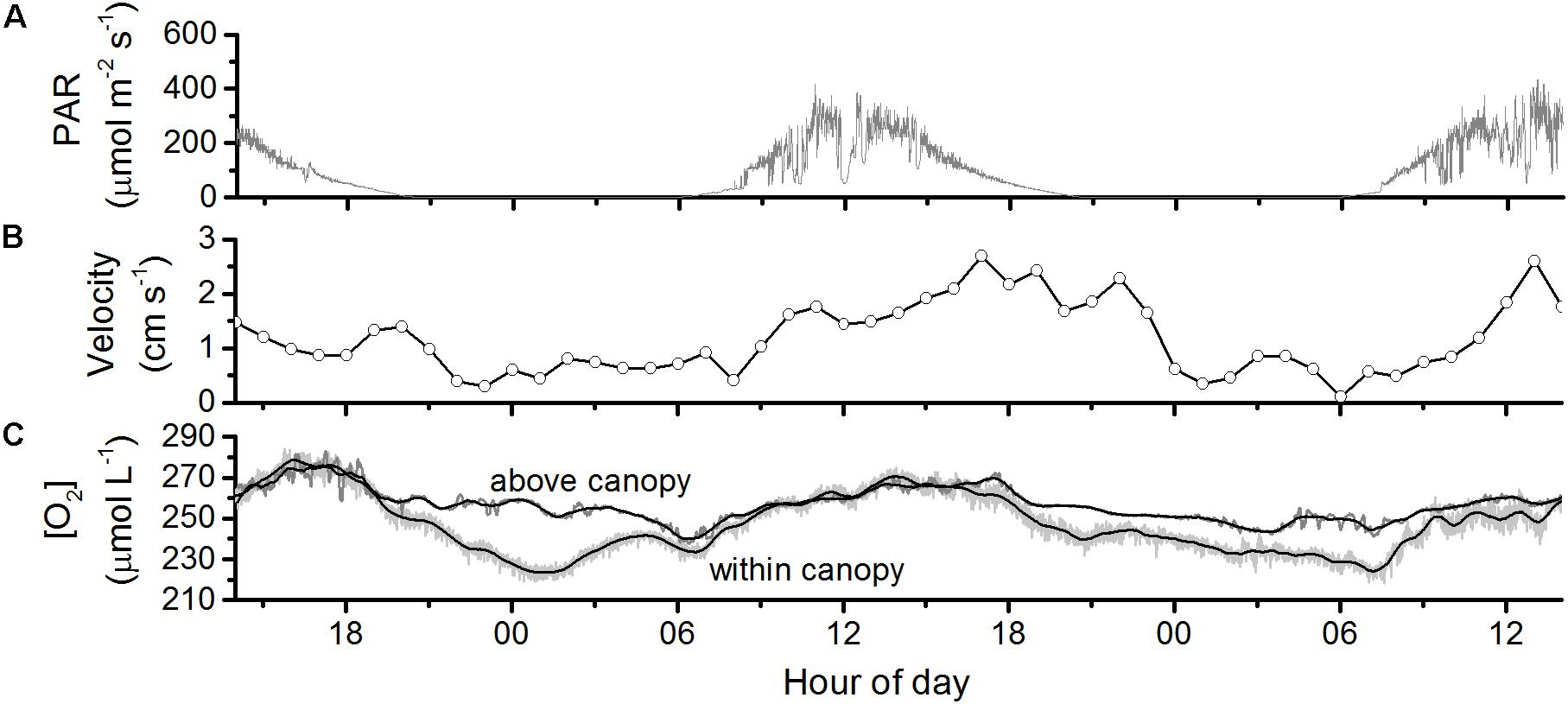

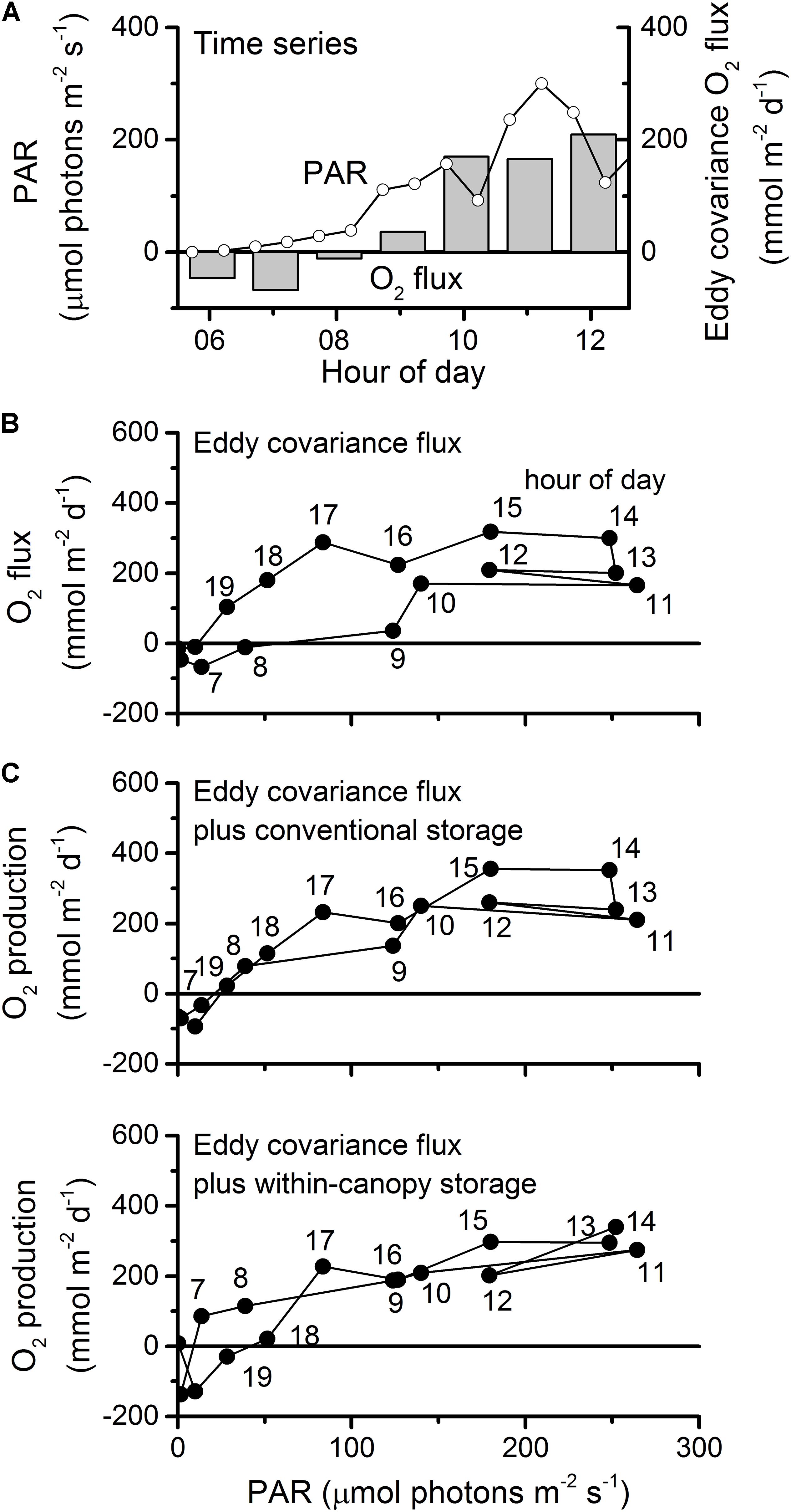

At the open-water meadow, nighttime dissolved oxygen within the canopy fell by 20–30 μM relative to overlying water (Figure 2). During the day, the dissolved oxygen levels within the canopy were equal to those in overlying water. The efflux of oxygen due to photosynthesis increased suddenly in the late morning (Figure 3A). When plotting eddy covariance fluxes versus light intensities we observed a hysteresis, namely oxygen fluxes were lower in the early morning than in the afternoon at the same light intensities (Figure 3B). For example, O2 flux at 17:00 h was 275 mmol m–2 d–1 while at greater light intensity in the morning (09:00) it was close to zero. The conventional correction for O2 storage below the eddy measurement volume, using the change in dissolved O2 at the measurement volume (Rheuban et al., 2014b), was insufficient to resolve the hysteresis (Figure 3C). This conventional correction relies on the assumption that turbulence mixes dissolved oxygen thoroughly through the seagrass canopy and down to the seafloor. This assumption may be valid where the seagrass canopy is small, biomass is low, or water velocities are high, one or more of which attributes are true in each of the prior studies of eddy covariance oxygen fluxes over seagrasses (their results are summarized in Supplementary Table S1). However, it was not valid for this P. oceanica meadow. Instead, we needed to account for the depletion and replenishment of dissolved O2 within the canopy to resolve the hysteresis (Figure 3D).

Figure 2. Diel changes in (A) photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), (B) water velocity, and (C) dissolved oxygen at the open-water seagrass meadow in May of 2016. Dissolved oxygen was measured immediately above the canopy and within it (0.2 m above the bed). Higher variance in the O2 signal within the canopy is due to lower sensor precision.

Figure 3. Correction of eddy covariance O2 flux for the storage of O2 in the water volume of the open-water canopy. (A) Morning PAR and eddy covariance O2 flux measured above the canopy. (B) O2 flux as a function of PAR showing hysteresis due to O2 storage. (C) O2 flux plus the conventional correction for storage using O2 measured above the canopy. (D) O2 flux plus our correction for O2 storage using O2 measured within the canopy.

In a novel approach, to account for depletion and replenishment of O2 within the meadow, we assumed a linear O2 concentration profile between the eddy measurement volume and an O2 logger placed 0.2 m above the bed. We chose a linear concentration profile to allow for turbulent mixing of overlying water into the canopy and its attenuation with depth (as decribed by Ikeda and Kanazawa, 1996). Storage was calculated from the change over time in the estimated mean O2 concentration below the eddy covariance measurement volume. Diel respiration and GPP, calculated from the thus-corrected O2 fluxes were 1.5 and 1.2 times the measured above-meadow fluxes, respectively. The above-canopy versus within-canopy storage correction was a small part (3–12%) of this correction, but it had a large effect on hourly productivity in the early morning and evening (the difference between Figures 3C,D). At the nearshore meadow, O2 production was also lower in the early morning than in the late afternoon at the same light levels (Supplementary Figure S1). The conventional storage correction was also insufficient to completely resolve the hysteresis at this meadow. Therefore, similar to the open-water meadow, the nearshore meadow may also have had reduced hydrodynamic exchange. However, the lack of oxygen measurements within the canopy of the nearshore meadow prevented further correction, so fluxes at that meadow are presented with the conventional storage correction only.

Primary Production and Respiration

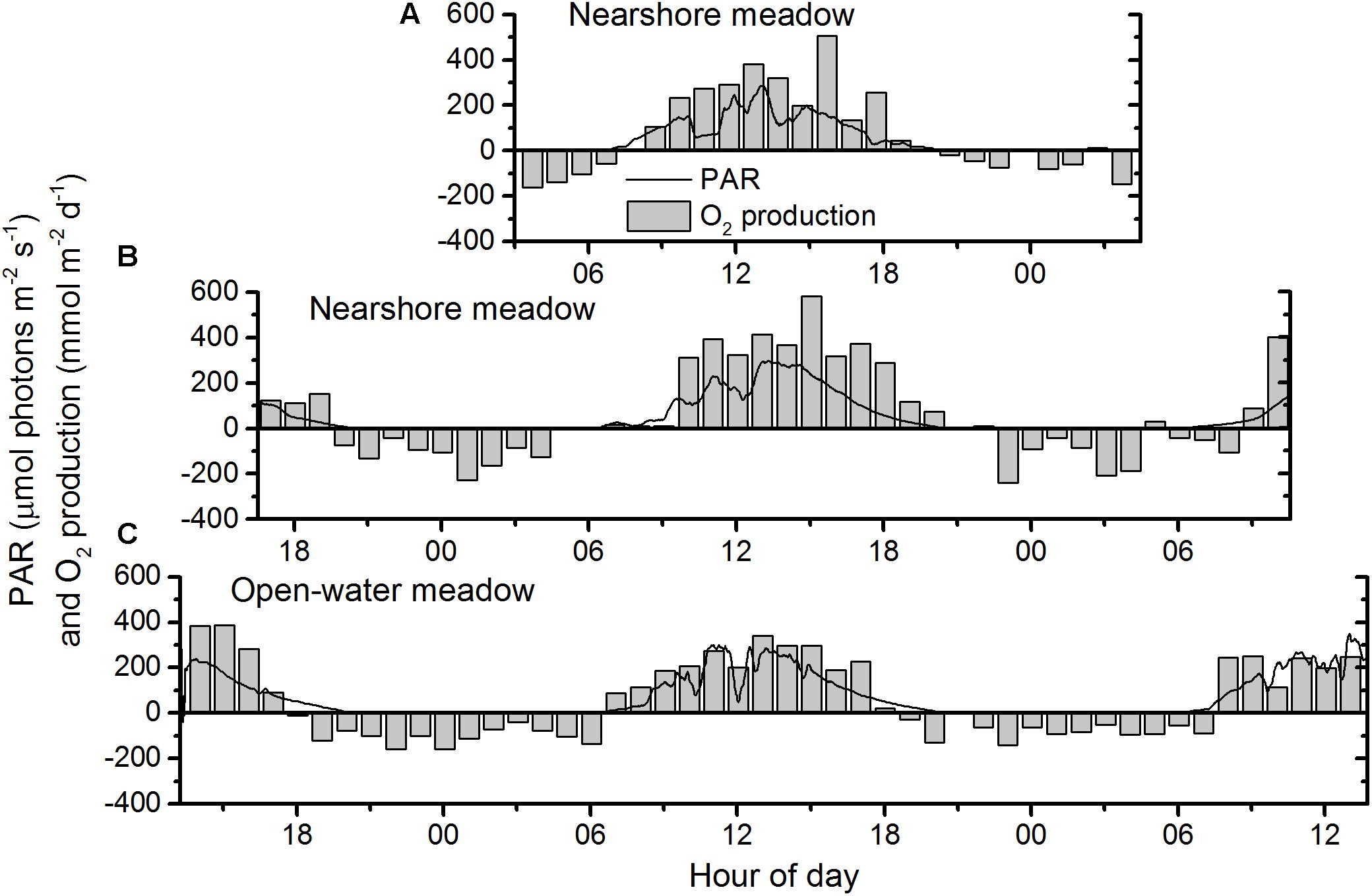

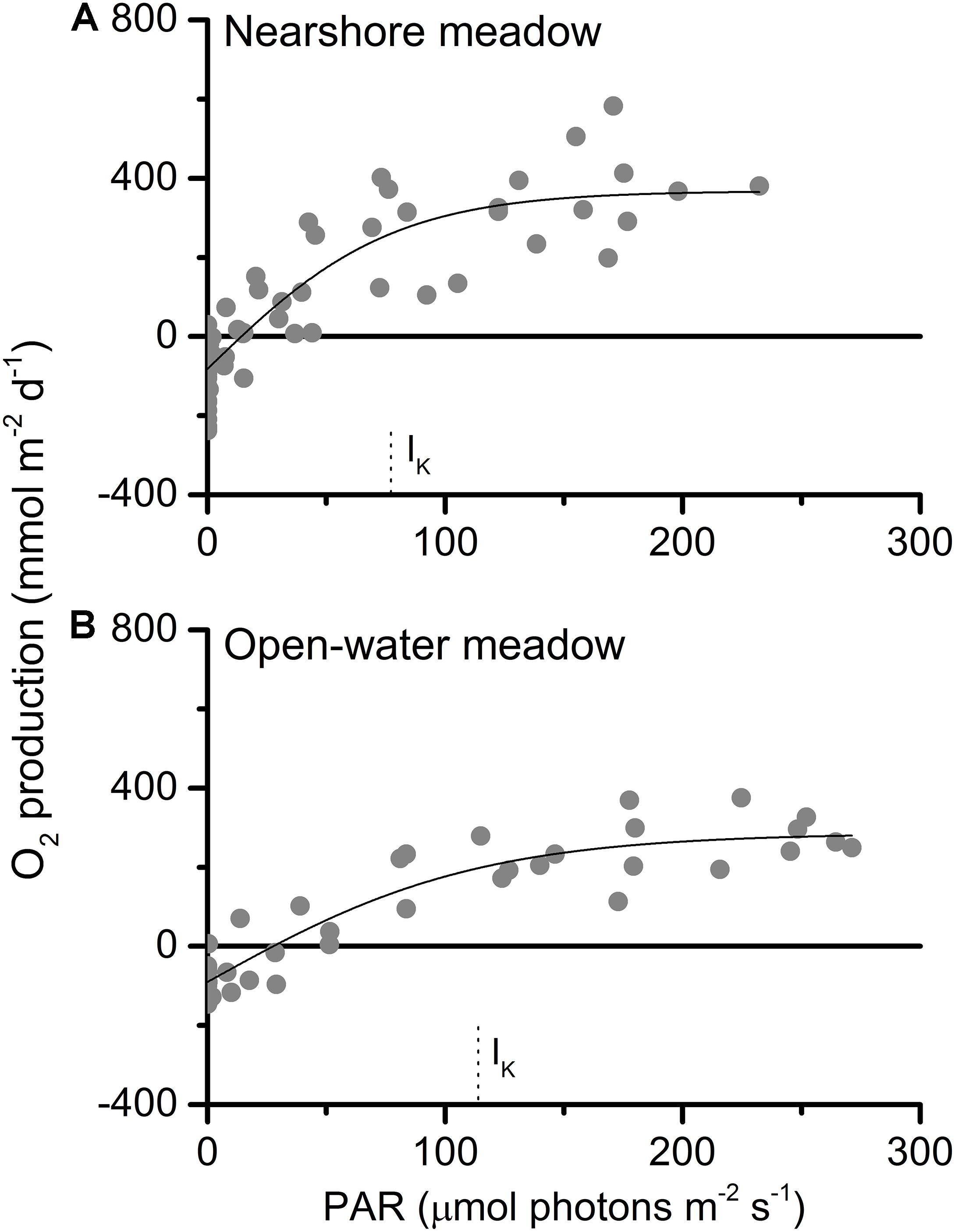

O2 production and consumption, calculated from storage-corrected fluxes, followed similar diurnal patterns at both meadows (Figure 4). Daytime O2 production exceeded nighttime O2 consumption on both days. Intermittent cloud cover reduced available light during the morning at each of the meadows. This resulted in temporary decreases in observed PAR of up to 80% (Figure 4) and lower overall PAR exposure on the first day at each of the meadows (Table 1). Plotted as a function of irradiance, diel oxygen flux resembled a saturation curve (Figure 5). The maximum photosynthetic response (Pmax) was not met in either meadow. However, the saturation irradiance (IK) was less than one-half of peak irradiance at both meadows. This indicates that at high irradiance, the photosynthetic response of both meadows was approaching light saturation, where greater irradiance yielded little gain in photosynthetic production. The light compensation point (IC) varied between 6 and 17% of the peak irradiance.

Figure 4. Diel PAR and net photosynthesis (O2 production > 0) and respiration (O2 production < 0) at the nearshore meadow on (A) day one and (B) day two of data collection, and at (C) the open-water meadow over 2 days of continuous data collection.

Figure 5. Oxygen production as a function of PAR at (A) nearshore and (B) open-water seagrass meadows. The photosynthetic maxima (Pmax) were 449 ± 36 and 375 ± 27 mmol m–2 d–1; the light compensation points (IC) were 15 and 28 μmol photons m–2 s–1; and the saturation irradiances (IK) were 77 ± 15 and 113 ± 21 μmol photons m–2 s–1.

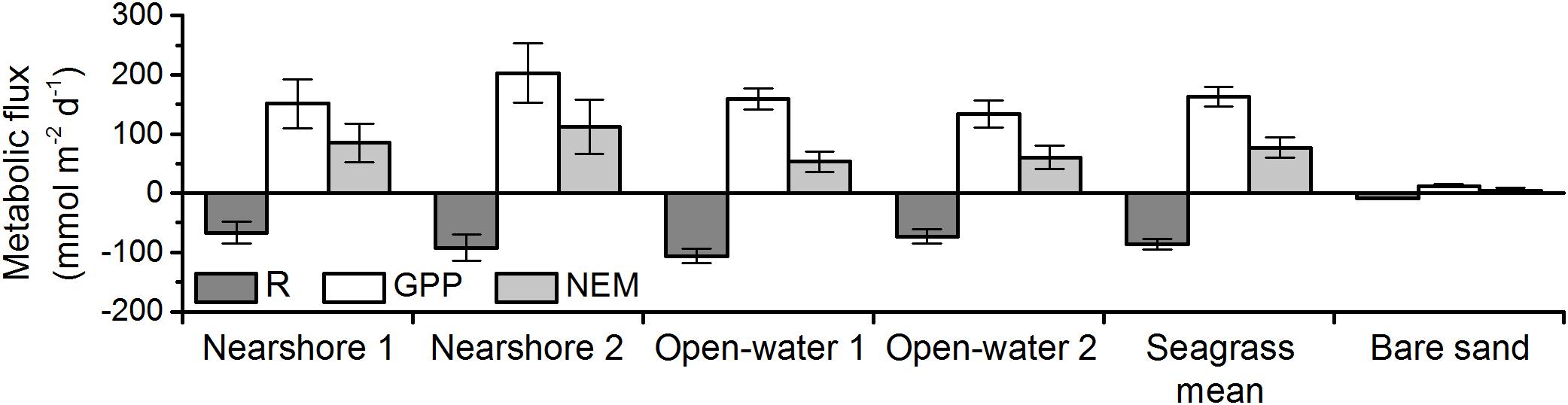

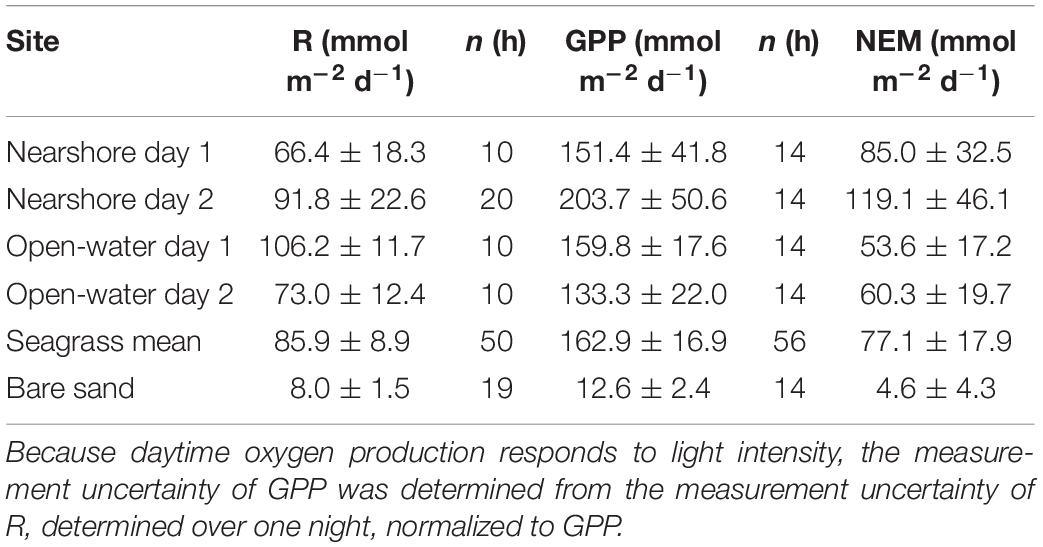

Respiration, gross primary production, and net ecosystem metabolism varied across sites, but all meadows were highly autotrophic (Figure 6 and Table 2). NEM at the nearshore meadow was somewhat elevated relative to the open-water meadow but the differences were not significant (Student’s t-test, p ≥ 0.05). Metabolic fluxes over bare sands were very small and net autotrophic. Bare sand GPP exceeded R by 50%. However, GPP was 10- to 16-fold smaller than meadow GPP. As a result, the NEM of sand was about 20-fold smaller than that of seagrass meadows.

Figure 6. Respiration (R), gross primary production (GPP), and net ecosystem metabolism (NEM) of seagrass meadows and bare sands in May of 2016 and 2017. Errors represent standard error. The number of replicates for each measurement is presented in Table 2. Seagrass mean NEM was significantly greater than that of bare sand (two-sample t-test; p < 0.05).

Table 2. Community metabolic fluxes including respiration (R), gross primary production (GPP), and net ecosystem metabolism (NEM; ± standard error).

Discussion

Photosynthetic Response to Irradiance

After the within-canopy storage correction, O2 production in the early morning was greater than O2 production in the evening at the same light levels (Figure 3D). This is consistent with enhanced respiration at the end of the day as observed in a Zostera marina meadow (Rheuban et al., 2014b). The resulting photosynthetic response of P. oceanica meadows to irradiance was surprisingly similar to the photosynthetic response of P. oceanica leaf segments to irradiance (Pirc, 1986; Ruiz and Romero, 2001). Self-shading within dense meadows is thought to allow seagrass to utilize all available irradiance, up to midday peaks in summer (Binzer et al., 2006; Sand-Jensen et al., 2007). This would result in a productive state of light limitation, where photosynthesis increases linearly with irradiance. In support of this possibility, P. oceanica meadows rely on carbohydrate reserves to fuel growth during the winter. This allows the canopies to be highly developed for light capture by late spring (Alcoverro et al., 2001b). However, P. oceanica meadows did not produce oxygen in proportion to irradiance up to peak irradiance at midday. In comparison of our results with other studies, it is important to note that the photosynthetic response to irradiance of P. oceanica leaves collected at different water depths is generally similar (Olesen et al., 2002), even where acclimation to depth occurs (Dattolo et al., 2014). Light saturation at the nearshore meadow (77 ± 15 μmol photons m–2 s–1) and at the open-water meadow (113 ± 21 μmol photons m–2 s–1) occurred at less than half of peak irradiance. These saturating irradiances substantially exceed those determined in other studies using rapid light curves to determine electron transport rates on P. oceanica leaves (Dattolo et al., 2014; Cox et al., 2016). However, our results match saturation irradiances of P. oceanica leaf segments in some laboratory incubations (Pirc, 1986; Ruiz and Romero, 2003), and are well within the range reported in the literature (Drew, 1979; Alcoverro et al., 1998, 2001b; Ruiz et al., 2001). The similarity of our results with laboratory incubations indicates that photosynthetic production of P. oceanica meadows, similar to individual leaves, is limited by the photosynthetic capacity of leaf tissues.

This response contrasts with the linear increase in photosynthesis of mature Z. marina and T. testudinum meadows in situ as irradiance increases up to the midday peak in irradiance during summer (Rheuban et al., 2014a; Long et al., 2015b). In those more eutrophic environments light attenuates at shallower depths due to greater suspended particulate material including phytoplankton. Therefore, light limitation of primary production in those environments is more likely. In P. oceanica meadows, the lack of light limitation suggests that a factor other than light may limit primary production. Nutrient limitation may contribute. Chlorophyll content and the maximum photosynthetic rate of seagrasses increase with nutrient availability (Agawin et al., 1996; Alcoverro et al., 1998; Lee and Dunton, 1999). Limited availability of N and P nutrients may limit their ability to make use of the abundant light. Further measurements would improve our understanding of this response.

The irradiance compensation points (IC) of P. oceanica meadows in our study, in contrast, were generally greater than those of P. oceanica leaf segments documented in the literature. Nearshore and open-water meadow IC were 15 and 28 μmol photons m–2 s–1, or 6 and 11% of peak irradiance (Figure 5). Literature values of leaf segment IC are between 4 and 14 μmol photons m–2 s–1 (Drew, 1979; Pirc, 1986; Ruiz and Romero, 2001, 2003; Ruiz et al., 2001; Olesen et al., 2002), with the exception of more eutrophic meadows in NE Spain with higher values (Alcoverro et al., 1998, 2001a,b). The elevated IC in P. oceanica meadows in our study indicates, unsurprisingly, that respiration of the meadow is greater than that of leaf tissues alone. Compared with the IC of other seagrass species determined using eddy covariance, P. oceanica has lower light requirements. It was less than that of Z. marina meadows in Virginia coastal bays (21% of peak irradiance, Rheuban et al., 2014a) and less than that of T. testudinum meadows in Florida Bay (24% of peak irradiance, Long et al., 2015b). Therefore, P. oceanica meadows require less light to generate a positive carbon balance. It is worth noting that the time-averaged IC for a light-stressed P. oceanica meadow can be far greater (Gacia et al., 2012).

Highly Autotrophic Production of Posidonia oceanica Meadows

The mean ratio of GPP to R of P. oceanica meadows in this study was 1.90 (Supplementary Table S1), indicating that almost one-half of the gross carbon fixed during photosynthesis either accumulates or is exported. This rate is higher than the median reported benthic chamber ratio of P. oceanica GPP to R (1.64, n = 18; Duarte et al., 2010). The high rate of net production of P. oceanica that we observe is sufficient to support the high storage and export of fixed carbon for which this ecosystem is known. The mean net oxygen production was 77.1 ± 17.9 mmol m–2 d–1 (Table 2). Assuming a photosynthetic quotient of 1.0, this results in a net carbon fixation of 0.93 g C m–2 d–1. Net organic carbon storage in P. oceanica sediments is estimated at 21 g m–2 y–1 (Serrano et al., 2012). This is equivalent to 4.8 mmol C m–2 d–1, or 6.2% of our measurements of NEM. The primary loss of fixed carbon in P. oceanica meadows (70%) is the annual export of sloughed leaves (Mateo et al., 2003). An additional pathway is dissolved organic carbon exudation. A median rate is 10.7 ± 2.9 mmol C m–2 d–1 in spring and summer (n = 18; Barrón and Duarte, 2009), equivalent to 14% of NEM. Combined, these loss estimates account for 90% of fixed carbon, indicating that the meadows can sustain them. Seasonal measurements of metabolism would be highly valuable for constraining the carbon budget further.

The installation and use of benthic chambers may affect seagrass metabolic fluxes. To investigate, we looked for systematic differences between our measurements and measurements of P. oceanica metabolism determined using benthic chambers (compiled by Duarte et al., 2010), including a more recent study (Gacia et al., 2012). We compared only measurements made at the seasonal peak of P. oceanica primary production in May and June (Frankignoulle and Bouquegneau, 1987), for a total of 11 benthic chamber measurements made at water depths of 4 to 22 m. We found that the median NEM of P. oceanica meadows determined with benthic chambers was half of our measurements (36 mmol m–2 d–1, with a range of −15 to 137 mmol m–2 d–1). This suggests that benthic chambers may underestimate the net production of seagrass meadows. An additional comparison can also be made to diel-change measurements of P. oceanica metabolism. May and June NEM of a P. oceanica meadow in Corsica determined with the diel-change technique (70 mmol m–2 d–1, n = 6; Champenois and Borges, 2012) matched the median NEM of our measurements. However, median R and GPP determined with the diel-change technique was 2- and 3-fold greater than our measurements, respectively. The shoot density in the Corsican meadow matched shoot density at Elba meadows. The differences between these measurements may be due to differences among the meadows, but biases in techniques may also contribute. Long residence times and stratification introduced high variance for diel change measurements of metabolism in T. testudinum, in comparison to eddy covariance measurements (Long et al., 2015a). Similar issues could contribute to the differences documented here.

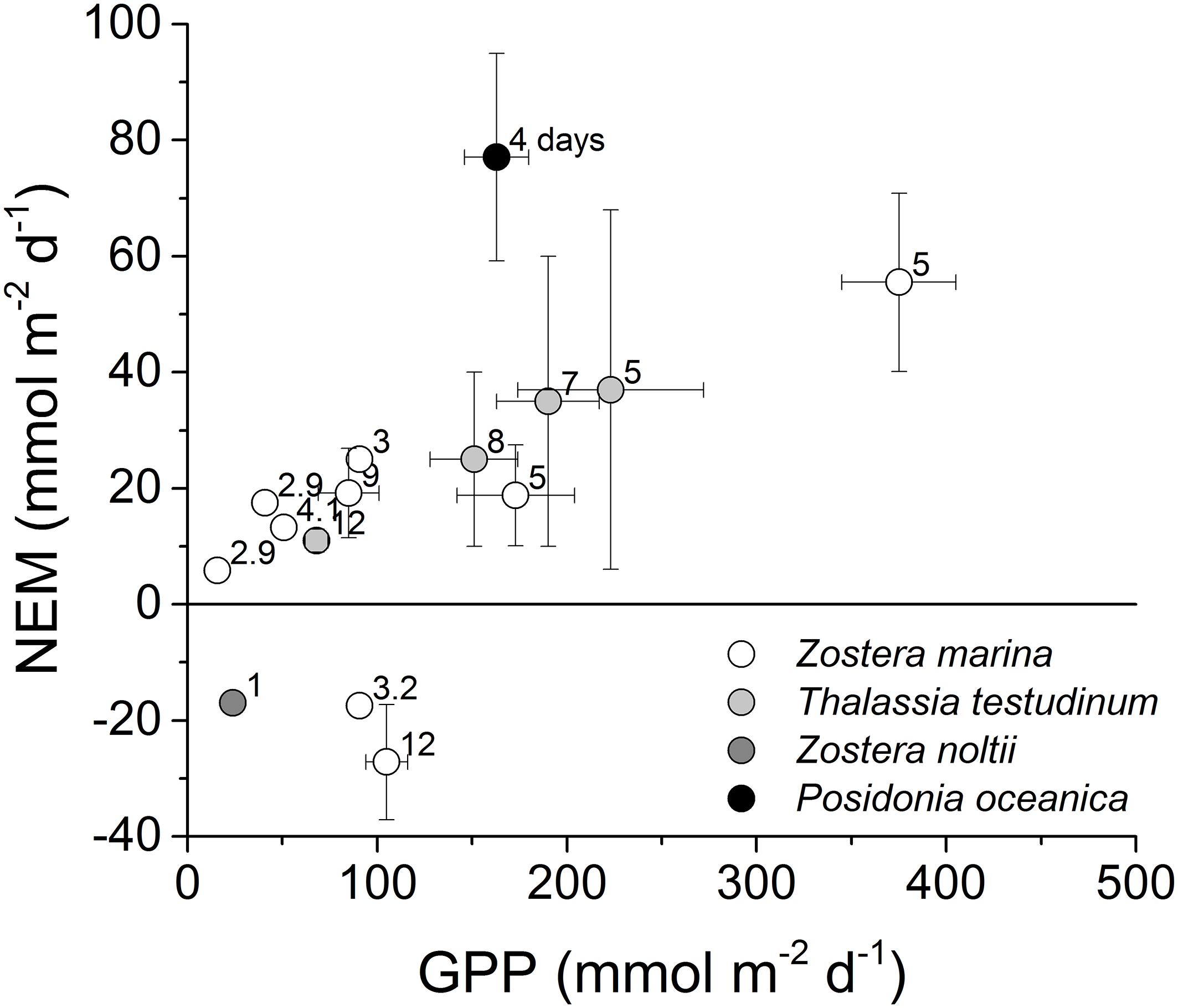

Prior studies utilizing the eddy covariance technique in spring and summer identified a lower rate of NEM as a fraction of GPP in Zostera marina meadows in Virginia coastal bays (Rheuban et al., 2014a), and in Thalassia testudinum meadows in Florida Bay, United States (Long et al., 2015b), than we observed in P. oceanica meadows (Figure 7). Gross primary production in P. oceanica meadows was less than that of these other meadows, but due to the low respiration of P. oceanica, their NEM was greater. More recent studies include summer eddy covariance measurements of Z. marina metabolism in the Baltic Sea (Attard et al., 2019), and Z. noltii in the Black Sea (Lee et al., 2017). The proportion of GPP to R was higher for Z. marina in the Baltic Sea than in Virginia coastal bays, but overall NEM was small, one-fourth or less that of P. oceanica (Figure 7). Net losses of biomass were observed for Z. noltii (Lee et al., 2017). For a complete evaluation of the metabolism of P. oceanica meadows, seasonal measurements are needed. Posidonia oceanica grows at the expense of carbon reserves for most of the year, only replenishing those reserves in the late spring and summer (Alcoverro et al., 2000). Therefore, spring and summer will be a period of maximum net organic carbon storage. The ecosystem may be net heterotrophic in other seasons. However, looking at metabolism in this season only, our measurements suggest that P. oceanica meadows store a greater proportion of organic production in the highly oligotrophic Mediterranean than Zostera and Thalassia meadows in more eutrophic seas. Our results suggest that diel organic carbon storage in P. oceanica in late spring is distinctly greater than that of Z. marina and T. testudinum. This distinct behavior can be examined in distinct aspects of its physiology and its environment.

Figure 7. Across-study comparison of spring and summer (March through August) seagrass ecosystem metabolism determined with aquatic eddy covariance. Labels indicate days of measurement. To evaluate autotrophy, net ecosystem metabolism (NEM) is presented as a function of gross primary production (GPP; ± s.e.). Literature sources for Z. marina: Hume et al. (2011), Rheuban et al. (2014a), Attard et al. (2019), and Berg et al. (2019); Z. noltii: Lee et al. (2017); T. testudinum: Long et al. (2015b); P. oceanica: this study.

Among the aspects of physiology that may contribute to high net production in P. oceanica meadows in late spring is the long turnover time of above- and below-ground biomass. Posidonia oceanica below-ground biomass is the highest among seagrasses, and above-ground biomass is among the highest (Duarte and Chiscano, 1999; Lavery et al., 2013). The energy spent on biomass production, however, is average (Duarte and Chiscano, 1999). To explain this discrepancy, P. oceanica roots and rhizomes have turnover times that exceed those of other seagrasses. Posidonia oceanica roots and rhizomes have a turnover time on the order of centuries (Romero et al., 1994), and leaves have a turnover time of nearly a year (Hemminga et al., 1999). As a result, P. oceanica maintains higher above- and below-ground biomass at a lower metabolic cost than other seagrasses (Olesen et al., 2002). This would allow for greater production as a fraction of GPP. Among these attributes, the maintenance of very high below ground biomass is surprising for a highly autotrophic species. Below-ground biomass confers an advantage in the acquisition of nutrients, but it is also a metabolic burden (Hemminga, 1998). Without oxygenation of roots, hydrogen sulfide intrusion can kill P. oceanica (Calleja et al., 2007). In one defense against this problem, P. oceanica roots and rhizomes have a high fiber and phenolic content (Harrison, 1989). This, in combination with low nutrient availability, would minimize their heterotrophic organic matter mineralization (Mateo et al., 1997; Serrano et al., 2012). As a result, sulfide production due to the anaerobic mineralization of this material by heterotrophic bacteria would also be minimized. Many other physiological factors would contribute to the net production of P. oceanica, including the low compensating irradiance of P. oceanica leaves (Alcoverro et al., 1998), and the export of sloughed leaves from the ecosystem.

Among the aspects of the environment that may contribute to the high net production in P. oceanica meadows in late spring are light availability, and the scarcity of nutrients and labile organic matter. Light availability in relation to Z. marina and T. testudinum was discussed briefly above. Nutrient addition enhances benthic respiration, reducing the organic carbon stored in P. oceanica sediments (Lopez et al., 1998). Persistent addition can drive a metabolic change from P. oceanica meadow autotrophy to net heterotrophy (Apostolaki et al., 2010). Allochthonous organic matter fuels net respiration in Z. marina meadows (Rheuban et al., 2014a), but it is almost absent from the oligotrophic Mediterranean in summer (Copin-Montégut and Avril, 1993). There are photosynthetic diatoms, foraminifera, and dinoflagellates in these sands that are capable of producing 14 mmol O2 m–2 d–1 (Sevilgen, 2008). The small nighttime oxygen uptake, and small net autotrophy over a diel cycle (Table 2) is evidence that there is little labile organic matter available for heterotrophs. Looking beyond seagrass meadows, when energy is abundant, carbohydrate storage can be stimulated by nutrient limitation in fungi, algae, plants, and bacteria (Lillie and Pringle, 1980; Zimmerman and Kremer, 1986; Wang and Tillberg, 1996; Børsheim et al., 2005). The high storage of organic carbon in P. oceanica meadows in late spring and summer may be similar. Additional ecological factors that could contribute to the high net production of P. oceanica meadows include the lower algal cover (McGlathery, 2001) and lower invertebrate densities (Boström and Bonsdorff, 1997).

Posidonia oceanica, an Oasis in the Desert

The high productivity of P. oceanica seagrass meadows is consistent with the high productivity of P. oceanica plants determined by laboratory-irradiance, benthic chambers, leaf-tagging, and biomass measurements (Drew, 1979; Ott, 1980; Libes, 1986; Pergent et al., 1994), thus emphasizing the importance of seagrass in the local organic carbon budget (Duarte et al., 2010). Implicit in these prior observations is the high productivity of P. oceanica relative to surrounding sands, but direct comparisons have rarely been made. In contrast to the high productivity of meadows, we also found that Mediterranean sands are unusually unproductive. Specifically, the respiration that we measured in Elba sands (Table 2) was among the lowest reported for coastal permeable sediments (reviewed by Huettel et al., 2014). Benthic fluxes determined with chambers can depend on the stirring speed (Janssen et al., 2005). Nevertheless, prior measurements of metabolic flux using benthic chambers in oligotrophic Mediterranean sands gave similar results to our study. The median benthic respiration in May and June in Mallorca sands was 8.6 mmol C m–2 d–1 (range of 6.9 to 9.1, n = 4; Barrón et al., 2006a). The median NEM elsewhere in the Spanish Mediterranean in May and June was −2.1 mmol m–2 d–1 (range of −4 to 11, n = 12; Holmer et al., 2004; Gazeau et al., 2005; Barrón et al., 2006a). Taken together, the results agree that there is little organic carbon production or mineralization in these sands. Consistent with this observation, organic matter concentrations in the epilimnion of the Mediterranean are so low in the summer that many benthic suspension feeders undergo dormancy to avoid starvation (Coma and Ribes, 2003).

The capacity of P. oceanica to flourish and produce abundant biomass in oligotrophic water can be explained in terms of the acquisition and retention of nutrients. Posidonia oceanica take up nutrients through roots and leaves primarily in winter and early spring, when nutrients are more abundant (Lepoint et al., 2002). Nutrients are reallocated before leaves are shed (Alcoverro et al., 2000). Seagrasses collect particles passively, through flow-attenuation and particle deposition (Gacia et al., 1999, 2002). Seagrasses also collect particles actively. Macro- and epifaunal suspension feeders enhance particle filtering by orders of magnitude over surrounding sands (Lemmens et al., 1996). The mineralization of these particles supplies nutrients for seagrass growth (Evrard et al., 2005; Barrón et al., 2006b).

Potential for Nutrient Recycling Within the Canopy

Our results suggest that the resistance to mass transfer of P. oceanica meadows may be useful for nutrient retention. Generally, hydrodynamic exchange is expected to enhance seagrass photosynthetic production by increasing the exposure of seagrass to nutrients in the surrounding environment (Thomas et al., 2000). It is surprising, then, that a resistance to mass transfer may be common in P. oceanica meadows (e.g., Hendriks et al., 2014). One explanation is that the reduction in dissolved oxygen within the meadow at night (Figure 2) is consistent with the retention of the products of ecosystem respiration. This would include remineralized nutrients. Posidonia oceanica take up phosphorus and nitrogen through roots and leaves (Fresi and Saggiomo, 1981; Lepoint et al., 2002). Nutrient uptake by roots, while supplemented by nitrogen-fixation (Garcias-Bonet et al., 2016), is diffusion-limited, and thus may be insufficient to meet nutrient requirements (Lepoint et al., 2002). Material deposited in seagrass meadows is typically low in nitrogen and phosphorus, but nevertheless over annual cycles can meet the demand of P. oceanica (Gacia et al., 2002). We estimated the potential benefit of nutrient retention by assuming Redfield ratios of nutrients in mineralized organic matter (C:N:P of 106:16:1, mineralized by 138 moles of O2; Redfield, 1958). Under the assumption that nitrogen is mineralized to nitrate, a 20 μmol L–1 O2-deficit between the meadow and overlying waters corresponds to a 2.3 μmol L–1 (i.e., 2.3 mmol m–3) increase in NO3–. For a 0.6 m-high canopy this amounts to 1.4 mmol m–2 of extra NO3–, or 12 mmol m–2 d–1 of GPP by the Redfield ratio. This is between 7 and 9% of GPP of the meadow. The same increase in GPP also applies to phosphorus. Given the high C:N:P of P. oceanica leaves (median of 534:21:1, Duarte, 1990), and that half of P. oceanica nutrients are translocated from old to new leaves for growth (Alcoverro et al., 2000), the importance of this source of new nutrients may be far greater. Due to hydrodynamic retention, nutrient concentrations at the base of P. oceanica meadows in summer are elevated to, e.g., 1 μmol L–1 NO3–, 1 μmol L–1 NH4+, and 0.1 μmol L–1 PO43−(Gobert et al., 2002). Without retention, these remineralized nutrients may be lost to overlying and surrounding waters.

Based on these observations, we propose that diel oscillations in water velocity caused by the diurnal sea breeze may benefit seagrasses growing in the Mediterranean. For a seagrass meadow to recycle nutrients that were mineralized during the night into daytime photosynthetic production, hydrodynamic exchange would need to be reduced during the night and into the morning. Late in the morning, after nutrients had been depleted, it may be an advantage for hydrodynamic exchange to be enhanced, to prevent accumulation of O2 which can cause photorespiration (Falkowski and Raven, 2013). Interestingly, as a result of the diurnal sea breeze, this is the diel pattern in water velocities at Elba (Table 1). This diel pattern is dominant on Mediterranean coasts from May into September (Furberg et al., 2002), and thus may be exploited by P. oceanica when nutrient limitation is at a maximum.

Data Availability Statement

Hourly aquatic eddy covariance fluxes and environmental data for this study will be made available through the PANGAEA data repository (https://www.pangaea.de/; Koopmans et al., 2020).

Author Contributions

DB conceived the study. All authors contributed to field work. MW coordinated field work. DK and MH analyzed the eddy covariance data. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the interpretation. DK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to it.

Funding

This project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 654462 (STEMM-CCS), it also received funding from the Max Planck Society and the Helmholtz Society.

Conflict of Interest

MW was employed at HYDRA Marine Sciences GmbH.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to scientists and divers of the HYDRA Field Station on Elba; to Anna Lichtschlag at the National Oceanography Centre; and to staff at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology including the Electronics Workshop, technicians of the Microsensor Group, the Mechanical Workshop, and technicians of the HGF MPG Joint Research Group for Deep-Sea Ecology and Technology. A pre-print of a prior version of this manuscript is available at Biogeosciences Discussions (Koopmans et al., 2018).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2020.00118/full#supplementary-material

References

Agawin, N. S., Duarte, C. M., and Fortes, M. D. (1996). Nutrient limitation of Philippine seagrasses (Cape Bolinao, NW Philippines): in situ experimental evidence. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 138, 233–243. doi: 10.3354/meps138233

Alcoverro, T., Cerbiān, E., and Ballesteros, E. (2001a). The photosynthetic capacity of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica: influence of nitrogen and light. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 261, 107–120. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0981(01)00267-2

Alcoverro, T., Manzanera, M., and Romero, J. (2001b). Annual metabolic carbon balance of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica: the importance of carbohydrate reserves. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 211, 105–116. doi: 10.3354/meps211105

Alcoverro, T., Duarte, C. M., and Romero, J. (1995). Annual growth dynamics of Posidonia oceanica: contribution of large-scale versus local factors to seasonality. Oceanogr. Lit. Rev. 10:887.

Alcoverro, T., Manzanera, M., and Romero, J. (1998). Seasonal and age-dependent variability of Posidonia oceanica (L.) delile photosynthetic parameters. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 230, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0981(98)00022-7

Alcoverro, T., Manzanera, M., and Romero, J. (2000). Nutrient mass balance of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica: the importance of nutrient retranslocation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 194, 13–21. doi: 10.3354/meps194013

Apostolaki, E. T., Holmer, M., Marbà, N., and Karakassis, I. (2010). Metabolic imbalance in coastal vegetated (Posidonia oceanica) and unvegetated benthic ecosystems. Ecosystems 13, 459–471. doi: 10.1007/s10021-010-9330-9

Attard, K. M., Rodil, I. F., Glud, R. N., Berg, P., Norkko, J., and Norkko, A. (2019). Seasonal ecosystem metabolism across shallow benthic habitats measured by aquatic eddy covariance. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 4, 79–86. doi: 10.1002/lol2.10107

Barrón, C., and Duarte, C. M. (2009). Dissolved organic matter release in a Posidonia oceanica meadow. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 374, 75–84. doi: 10.3354/meps07715

Barrón, C., Duarte, C. M., Frankignoulle, M., and Borges, A. V. (2006a). Organic carbon metabolism and carbonate dynamics in a Mediterranean seagrass (Posidonia oceanica), meadow. Estuar. Coasts 29, 417–426. doi: 10.1007/bf02784990

Barrón, C., Middelburg, J. J., and Duarte, C. M. (2006b). Phytoplankton trapped within seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) sediments are a nitrogen source: an in situ isotope labeling experiment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 1648–1653. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.4.1648

Bay, D. (1984). A field study of the growth dynamics and productivity of Posidonia oceanica (L.) delile in calvi bay, Corsica. Aquat. Bot. 20, 43–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(84)90026-3

Berg, P., Delgard, M. L., Polsenaere, P., McGlathery, K. J., Doney, S. C., and Berger, A. C. (2019). Dynamics of benthic metabolism, O2, and pCO2 in a temperate seagrass meadow. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 2586–2604. doi: 10.1002/lno.11236

Berg, P., Koopmans, D. J., Huettel, M., Li, H., Mori, K., and Wüest, A. (2016). A new robust oxygen-temperature sensor for aquatic eddy covariance measurements. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 14, 151–167. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10071

Berg, P., Long, M. H., Huettel, M., Rheuban, J. E., McGlathery, K. J., Howarth, R. W., et al. (2013). Eddy correlation measurements of oxygen fluxes in permeable sediments exposed to varying current flow and light. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 1329–1343. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.4.1329

Berg, P., Røy, H., Janssen, F., Meyer, V., Jørgensen, B. B., Huettel, M., et al. (2003). Oxygen uptake by aquatic sediments measured with a novel non-invasive eddy-correlation technique. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 261, 75–83. doi: 10.3354/meps261075

Berg, P., Røy, H., and Wiberg, P. L. (2007). Eddy correlation flux measurements: the sediment surface area that contributes to the flux. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 1672–1684. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.4.1672

Binzer, T., Sand-Jensen, K., and Middelboe, A.-L. (2006). Community photosynthesis of aquatic macrophytes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 2722–2733. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.6.2722

Børsheim, K. Y., Vadstein, O., Myklestad, S. M., Reinertsen, H., Kirkvold, S., and Olsen, Y. (2005). Photosynthetic algal production, accumulation and release of phytoplankton storage carbohydrates and bacterial production in a gradient in daily nutrient supply. J. Plankton Res. 27, 743–755. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbi047

Boström, C., and Bonsdorff, E. (1997). Community structure and spatial variation of benthic invertebrates associated with Zostera marina (L.) beds in the northern Baltic Sea. J. Sea Res. 37, 153–166. doi: 10.1016/s1385-1101(96)00007-x

Boudreau, B. P., Huettel, M., Forster, S., Jahnke, R. A., McLachlan, A., Middelburg, J. J., et al. (2001). Permeable marine sediments: overturning an old paradigm, EOS Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 82, 133–136.

Bulthuis, D. A. (1987). Effects of temperature on photosynthesis and growth of seagrasses. Aquat. Bot. 27, 27–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(87)90084-2

Calleja, M. L., Marbà, N., and Duarte, C. M. (2007). The relationship between seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) decline and sulfide porewater concentration in carbonate sediments. Estuar. Coastal Shelf Sci. 73, 583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2007.02.016

Campbell, J. E., and Fourqurean, J. W. (2011). Novel methodology for in situ carbon dioxide enrichment of benthic ecosystems. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 9, 97–109. doi: 10.4319/lom.2011.9.97

Champenois, W., and Borges, A. (2012). Seasonal and interannual variations of community metabolism rates of a Posidonia oceanica seagrass meadow. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 347–361. doi: 10.4319/lo.2012.57.1.0347

Chipman, L., Huettel, M., Berg, P., Meyer, V., Klimant, I., Glud, R., et al. (2012). Oxygen optodes as fast sensors for eddy correlation measurements in aquatic systems. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 10, 304–316. doi: 10.4319/lom.2012.10.304

Collier, C., and Waycott, M. (2014). Temperature extremes reduce seagrass growth and induce mortality. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 83, 483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.03.050

Coma, R., and Ribes, M. (2003). Seasonal energetic constraints in Mediterranean benthic suspension feeders: effects at different levels of ecological organization. Oikos 101, 205–215. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12028.x

Copin-Montégut, G., and Avril, B. (1993). Vertical distribution and temporal variation of dissolved organic carbon in the North-Western Mediterranean Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Papers 40, 1963–1972. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(93)90041-z

Cox, T. E., Gazeau, F., Alliouane, S., Hendriks, I., Mahacek, P., Le Fur, A., et al. (2016). Effects of in situ CO2 enrichment on structural characteristics, photosynthesis, and growth of the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Biogeosciences 13, 2179–2194. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-2179-2016

Dalla Via, J., Sturmbauer, C., Schönweger, G., Sötz, E., Mathekowitsch, S., Stifter, M., et al. (1998). Light gradients and meadow structure in Posidonia oceanica: ecomorphological and functional correlates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 163, 267–278. doi: 10.3354/meps171267

Dattolo, E., Ruocco, M., Brunet, C., Lorenti, M., Lauritano, C., D’esposito, D., et al. (2014). Response of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica to different light environments: insights from a combined molecular and photo-physiological study. Mar. Environ. Res. 101, 225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2014.07.010

Dennison, W. C., and Alberte, R. S. (1985). Role of daily light period in the depth distribution of Zostera marina(eelgrass). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 25, 51–61. doi: 10.3354/meps025051

Drew, E. A. (1979). Physiological aspects of primary production in seagrasses. Aquat. Bot. 7, 139–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(79)90018-4

Duarte, C. M. (1990). Seagrass nutrient content. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Oldendorf. 6, 201–207. doi: 10.3354/meps067201

Duarte, C. M., and Chiscano, C. L. (1999). Seagrass biomass and production: a reassessment. Aquat. Bot. 65, 159–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3770(99)00038-8

Duarte, C. M., Marbà, N., Gacia, E., Fourqurean, J. W., Beggins, J., Barrón, C., et al. (2010). Seagrass community metabolism: assessing the carbon sink capacity of seagrass meadows. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 24, 1–8. doi: 10.1029/2010GB003793

Evrard, V., Kiswara, W., Bouma, T. J., and Middelburg, J. J. (2005). Nutrient dynamics of seagrass ecosystems: 15N evidence for the importance of particulate organic matter and root systems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 295, 49–55. doi: 10.3354/meps295049

Falkowski, P. G., and Raven, J. A. (2013). Aquatic Photosynthesis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fonseca, M. S., and Kenworthy, W. J. (1987). Effects of current on photosynthesis and distribution of seagrasses. Aquat. Bot. 27, 59–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(87)90086-6

Forster, S., Huettel, M., and Ziebis, W. (1996). Impact of boundary layer flow velocity on oxygen utilisation in coastal sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 143, 173–185. doi: 10.3354/meps143173

Fourqurean, J. W., Duarte, C. M., Kennedy, H., Marbà, N., Holmer, M., Mateo, M. A., et al. (2012). Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nat. Geosci. 5:505. doi: 10.1002/eap.1489

Frankignoulle, M., and Bouquegneau, J. (1987). Seasonal variation of the diel carbon budget of a marine macrophyte ecosystem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 38, 197–199. doi: 10.3354/meps038197

Fresi, E., and Saggiomo, V. (1981). Phosphorous uptake and transfer in Posidonia oceanica (L.) delile. Rapports Procès-verbaux Réunions – Commiss. Int. Pour L’explor. Sci. Mer Méditerranée 27, 187–188.

Furberg, M., Steyn, D., and Baldi, M. (2002). The climatology of sea breezes on Sardinia. Int. J. Climatol. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 22, 917–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.03.023

Gacia, E., Duarte, C. M., and Middelburg, J. J. (2002). Carbon and nutrient deposition in a Mediterranean seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) meadow. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47, 23–32. doi: 10.4319/lo.2002.47.1.0023

Gacia, E., Granata, T., and Duarte, C. (1999). An approach to measurement of particle flux and sediment retention within seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) meadows. Aquat. Bot. 65, 255–268. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3770(99)00044-3

Gacia, E., Marbà, N., Cebrian, J., Vaquer-Sunyer, R., Garcias-Bonet, N., and Duarte, C. M. (2012). Thresholds of irradiance for seagrass Posidonia oceanica meadow metabolism. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 466, 69–79. doi: 10.3354/meps09928

Garcias-Bonet, N., Arrieta, J. M., Duarte, C. M., and Marbà, N. (2016). Nitrogen-fixing bacteria in Mediterranean seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) roots. Aquat. Bot. 131, 57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.08.004

Gazeau, F., Duarte, C. M., Gattuso, J.-P., Barrón, C., Navarro, N., Ruiz, S., et al. (2005). Whole-system metabolism and CO2 fluxes in a Mediterranean Bay dominated by seagrass beds (Palma Bay, NW Mediterranean). Biogeosciences 2, 43–60. doi: 10.5194/bg-2-43-2005

Gobert, S., Laumont, N., and Bouquegneau, J.-M. (2002). Posidonia oceanica meadow: a low nutrient high chlorophyll (LNHC) system? BMC Ecol. 2:9.

Greiner, J. T., McGlathery, K. J., Gunnell, J., and Mckee, B. A. (2013). Seagrass restoration enhances “blue carbon” sequestration in coastal waters. PLoS ONE 8:e72469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072469

Harrison, P. G. (1989). Detrital processing in seagrass systems: a review of factors affecting decay rates, remineralization and detritivory. Aquat. Bot. 35, 263–288. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(89)90002-8

Hemminga, M. (1998). The root/rhizome system of seagrasses: an asset and a burden. J. Sea Res. 39, 183–196. doi: 10.1016/s1385-1101(98)00004-5

Hemminga, M., Marba, N., and Stapel, J. (1999). Leaf nutrient resorption, leaf lifespan and the retention of nutrients in seagrass systems. Aquat. Bot. 65, 141–158. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3770(99)00037-6

Hendriks, I. E., Olsen, Y. S., Ramajo, L., Basso, L., Moore, T., Howard, J., et al. (2014). Photosynthetic activity buffers ocean acidification in seagrass meadows. Biogeosciences 11, 333–346. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-333-2014

Holmer, M., Duarte, C. M., Boschker, H., and Barrón, C. (2004). Carbon cycling and bacterial carbon sources in pristine and impacted Mediterranean seagrass sediments. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 36, 227–237. doi: 10.3354/ame036227

Holtappels, M., Glud, R. N., Donis, D., Liu, B., Hume, A., Wenzhöfer, F., et al. (2013). Effects of transient bottom water currents and oxygen concentrations on benthic exchange rates as assessed by eddy correlation measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 1157–1169. doi: 10.1002/jgrc.20112

Holtappels, M., Noss, C., Hancke, K., Cathalot, C., McGinnis, D. F., Lorke, A., et al. (2015). Aquatic eddy correlation: quantifying the artificial flux caused by stirring-sensitive O2 sensors. PLoS ONE 10:e0116564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116564

Howarth, R. W., and Michaels, A. F. (2000). “The measurement of primary production in aquatic ecosystems,” in Methods in Ecosystem Science, eds O. E. Sala, R. B. Jackson, H. A. Mooney, and R.W. Howarth (Berlin: Springer), 72–85. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-1224-9_6

Huettel, M., Berg, P., and Kostka, J. E. (2014). Benthic exchange and biogeochemical cycling in permeable sediments. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6, 23–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-051413-012706

Huettel, M., and Gust, G. (1992). Solute release mechanisms from confined sediment cores in stirred benthic chambers and flume flows. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 82, 187–197. doi: 10.3354/meps082187

Hume, A. C., Berg, P., and McGlathery, K. J. (2011). Dissolved oxygen fluxes and ecosystem metabolism in an eelgrass (Zostera marina) meadow measured with the eddy correlation technique. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 86–96. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.1.0086

Ikeda, S., and Kanazawa, M. (1996). Three-dimensional organized vortices above flexible water plants. J. Hydraulic Eng. 122, 634–640. doi: 10.1061/(asce)0733-9429(1996)122:11(634)

Janssen, F., Huettel, M., and Witte, U. (2005). Pore-water advection and solute fluxes in permeable marine sediments (II): benthic respiration at three sandy sites with different permeabilities (German Bight, North Sea). Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 779–792. doi: 10.4319/lo.2005.50.3.0779

Jassby, A. D., and Platt, T. (1976). Mathematical formulation of the relationship between photosynthesis and light for phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 21, 540–547. doi: 10.4319/lo.1976.21.4.0540

Koch, E. (1994). Hydrodynamics, diffusion-boundary layers and photosynthesis of the seagrasses Thalassia testudinum and Cymodocea nodosa. Mar. Biol. 118, 767–776. doi: 10.1007/bf00347527

Koopmans, D., Holtappels, M., Chennu, A., Weber, M., and De Beer, D. (2018). The response of seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) meadow metabolism to CO2 levels and hydrodynamic exchange determined with aquatic eddy covariance. Biogeosci. Discuss.

Koopmans, D., Holtappels, M., Chennu, A., Weber, M., and de Beer, D. (2020). Diel oxygen production and uptake by Posidonia oceanica meadows at Elba, Italy. PANGAEA. doi: 10.1594/PANGAEA.912944

Lavery, P. S., Mateo, M.-Á., Serrano, O., and Rozaimi, M. (2013). Variability in the carbon storage of seagrass habitats and its implications for global estimates of blue carbon ecosystem service. PLoS One 8:e73748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073748

Lee, J. S., Kang, D.-J., Hineva, E., Slabakova, V., Todorova, V., Park, J., et al. (2017). Estimation of net ecosystem metabolism of seagrass meadows in the coastal waters of the East Sea and Black Sea using the noninvasive eddy covariance technique. Ocean Sci. J. 52, 243–256. doi: 10.1007/s12601-017-0032-5

Lee, K.-S., and Dunton, K. H. (1999). Inorganic nitrogen acquisition in the seagrass Thalassia testudinum: development of a whole-plant nitrogen budget. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 1204–1215. doi: 10.4319/lo.1999.44.5.1204

Lemmens, J., Clapin, G., Lavery, P., and Cary, J. (1996). Filtering capacity of seagrass meadows and other habitats of Cockburn Sound, Western Australia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 143, 187–200. doi: 10.3354/meps143187

Lepoint, G., Millet, S., Dauby, P., Gobert, S., and Bouquegneau, J.-M. (2002). Annual nitrogen budget of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica as determined by in situ uptake experiments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 237, 87–96. doi: 10.3354/meps237087

Libes, M. (1986). Productivity-irradiance relationship of Posidonia oceanica and its epiphytes. Aquat. Bot. 26, 285–306. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01903

Lillie, S. H., and Pringle, J. R. (1980). Reserve carbohydrate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: responses to nutrient limitation. J. Bacteriol. 143, 1384–1394. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.3.1384-1394.1980

Long, M. H., Berg, P., and Falter, J. L. (2015a). Seagrass metabolism across a productivity gradient using the eddy covariance, Eulerian control volume, and biomass addition techniques. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 3624–3639. doi: 10.1002/2014jc010352

Long, M. H., Berg, P., McGlathery, K. J., and Zieman, J. C. (2015b). Sub-tropical seagrass ecosystem metabolism measured by eddy covariance. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 529, 75–90. doi: 10.3354/meps11314

Long, M. H., Rheuban, J. E., Berg, P., and Zieman, J. C. (2012). A comparison and correction of light intensity loggers to photosynthetically active radiation sensors. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 10, 416–424. doi: 10.4319/lom.2012.10.416

Lopez, N. I., Duarte, C. M., Vallespinós, F., Romero, J., and Alcoverro, T. (1998). The effect of nutrient additions on bacterial activity in seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) sediments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 224, 155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0981(97)00189-5

Lorrai, C., McGinnis, D. F., Berg, P., Brand, A., and Wüest, A. (2010). Application of oxygen eddy correlation in aquatic systems. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 27, 1533–1546. doi: 10.1175/2010jtecho723.1

Mateo, M., Romero, J., Pérez, M., Littler, M. M., and Littler, D. S. (1997). Dynamics of millenary organic deposits resulting from the growth of the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Estuar. Coastal Shelf Sci. 44, 103–110. doi: 10.1006/ecss.1996.0116

Mateo, M.-Á., Sanchez-Lizaso, J. -L., and Romero, J. (2003). Posidonia oceanica ‘banquettes’: a preliminary assessment of the relevance for meadow carbon and nutrients budget. Estuar. Coastal Shelf Sci. 56, 85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7714(02)00123-3

McGinnis, D. F., Berg, P., Brand, A., Lorrai, C., Edmonds, T. J., and Wüest, A. (2008). Measurements of eddy correlation oxygen fluxes in shallow freshwaters: towards routine applications and analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35:L04403. doi: 10.1029/2007GL032747

McGlathery, K. J. (2001). Macroalgal blooms contribute to the decline of seagrass in nutrient-enriched coastal waters. J. Phycol. 37, 453–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2001.037004453.x

Olesen, B., Enríquez, S., Duarte, C. M., and Sand-Jensen, K. (2002). Depth-acclimation of photosynthesis, morphology and demography of Posidonia oceanica and Cymodocea nodosa in the Spanish Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 236, 89–97. doi: 10.3354/meps236089

Olivé, I., Silva, J., Costa, M. M., and Santos, R. (2016). Estimating seagrass community metabolism using benthic chambers: the effect of incubation time. Estuaries Coasts 39, 138–144. doi: 10.1007/s12237-015-9973-z

Orth, R. J., Carruthers, T. J., Dennison, W. C., Duarte, C. M., Fourqurean, J. W., Heck, K. L., et al. (2006). A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. Bioscience 56, 987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2019.04.004

Ott, J. A. (1980). Growth and production in Posidonia oceanica (L.) delile. Mar. Ecol. 1, 47–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.1980.tb00221.x

Peralta, G., Brun, F. G., Pérez-Lloréns, J. L., and Bouma, T. J. (2006). Direct effects of current velocity on the growth, morphometry and architecture of seagrasses: a case study on Zostera noltii. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 327, 135–142. doi: 10.3354/meps327135

Peralta, G., Pérez-Lloréns, J., Hernández, I., and Vergara, J. (2002). Effects of light availability on growth, architecture and nutrient content of the seagrass Zostera noltii Hornem. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 269, 9–26. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0981(01)00393-8

Pergent, G., Romero, J., Pergent-Martini, C., Mateo, M. -A., and Boudouresque, C. -F. (1994). Primary production, stocks and fluxes in the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 106, 139–146. doi: 10.3354/meps106139

Pirc, H. (1986). Seasonal aspects of photosynthesis in Posidonia oceanica: influence of depth, temperature and light intensity. Aquat. Bot. 26, 203–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(86)90021-5

Powell, G. V., Kenworthy, J. W., and Fourqurean, J. W. (1989). Experimental evidence for nutrient limitation of seagrass growth in a tropical estuary with restricted circulation. Bull. Mar. Sci. 44, 324–340.

Ralph, P., Durako, M. J., Enriquez, S., Collier, C., and Doblin, M. (2007). Impact of light limitation on seagrasses. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 350, 176–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2007.06.017

Redfield, A. C. (1958). The biological control of chemical factors in the environment. Am. Sci. 46, 230A-221.

Reichert, P., Uehlinger, U., and Acuña, V. (2009). Estimating stream metabolism from oxygen concentrations: effect of spatial heterogeneity. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 114:G03016.

Rheuban, J. E., Berg, P., and McGlathery, K. J. (2014a). Ecosystem metabolism along a colonization gradient of eelgrass (Zostera marina) measured by eddy correlation. Limnol. Oceanogr. 59, 1376–1387. doi: 10.4319/lo.2014.59.4.1376

Rheuban, J. E., Berg, P., and McGlathery, K. J. (2014b). Multiple timescale processes drive ecosystem metabolism in eelgrass (Zostera marina) meadows. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 507, 1–13. doi: 10.3354/meps10843

Romero, J., Pérez, M., Mateo, M., and Sala, E. (1994). The belowground organs of the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica as a biogeochemical sink. Aquat. Bot. 47, 13–19. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(94)90044-2

Ruiz, J., and Romero, J. (2003). Effects of disturbances caused by coastal constructions on spatial structure, growth dynamics and photosynthesis of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 46, 1523–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2003.08.021

Ruiz, J. M., Pérez, M., and Romero, J. (2001). Effects of fish farm loadings on seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) distribution, growth and photosynthesis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 42, 749–760. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(00)00215-0

Ruiz, J. M., and Romero, J. (2001). Effects of in situ experimental shading on the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 215, 107–120. doi: 10.3354/meps215107

Sand-Jensen, K., Binzer, T., and Middelboe, A. L. (2007). Scaling of photosynthetic production of aquatic macrophytes–a review. Oikos 116, 280–294. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15093.x

Serrano, O., Mateo, M., Renom, P., and Julià, R. (2012). Characterization of soils beneath a Posidonia oceanica meadow. Geoderma 185, 26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2012.03.020

Sevilgen, D. (2008). Comparative Study of Benthic Primary Production in Silicate and Carbonate Sands of the Islands Elba and Pianosa (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). Diploma Thesis, University of Bremen, Bremen.

Short, F. T. (1987). Effects of sediment nutrients on seagrasses: literature review and mesocosm experiment. Aquat. Bot. 27, 41–57. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(87)90085-4

Staehr, P. A., Bade, D., Van De Bogert, M. C., Koch, G. R., Williamson, C., Hanson, P., et al. (2010). Lake metabolism and the diel oxygen technique: state of the science. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 8, 628–644. doi: 10.4319/lom.2010.8.0628

Thomas, F. I., Cornelisen, C. D., and Zande, J. M. (2000). Effects of water velocity and canopy morphology on ammonium uptake by seagrass communities. Ecology 81, 2704–2713. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2704:eowvac]2.0.co;2

Udy, J. W., and Dennison, W. C. (1997). Growth and physiological responses of three seagrass species to elevated sediment nutrients in Moreton Bay, Australia. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 217, 253–277. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0981(97)00060-9

Wang, C., and Tillberg, J. E. (1996). Effects of nitrogen deficiency on accumulation of fructan and fructan metabolizing enzyme activities in sink and source leaves of barley (Hordeum vulgare). Physiol. Plant. 97, 339–345. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1996.970218.x

Wilczak, J. M., Oncley, S. P., and Stage, S. A. (2001). Sonic anemometer tilt correction algorithms. Boundary Layer Meteorol. 99, 127–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1018966204465

Keywords: seagrass, Posidonia oceanica, Mediterranean, respiration, primary production, eddy covariance, oxygen flux, photosynthesis

Citation: Koopmans D, Holtappels M, Chennu A, Weber M and de Beer D (2020) High Net Primary Production of Mediterranean Seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) Meadows Determined With Aquatic Eddy Covariance. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:118. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00118

Received: 04 September 2019; Accepted: 13 February 2020;

Published: 10 March 2020.

Edited by:

Stelios Katsanevakis, University of the Aegean, GreeceReviewed by:

Karl Attard, University of Southern Denmark, DenmarkInés Mazarrasa, Environmental Hydraulics Institute (IHCantabria), Spain

Copyright © 2020 Koopmans, Holtappels, Chennu, Weber and de Beer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dirk Koopmans, ZGlyay5rb29wbWFuc0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Dirk Koopmans

Dirk Koopmans Moritz Holtappels

Moritz Holtappels Arjun Chennu

Arjun Chennu Miriam Weber3,4

Miriam Weber3,4 Dirk de Beer

Dirk de Beer