95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 22 January 2020

Sec. Marine Biogeochemistry

Volume 6 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00839

Oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) in the ocean are expanding. This expansion is attributed to global warming and may continue over the next 10 to 100 kyrs due to multiple climate CO2-driven factors. The expansion of oxygen-deficient waters has the potential to enhance organic carbon burial in marine sediments, thereby providing a negative feedback on global warming. Here, we study the response of dissolved oxygen in the ocean to increased phosphorus and iron inputs due to CO2-driven enhanced weathering and increased dust emissions, respectively. We use an ocean biogeochemical model coupled to a general ocean circulation model (the Hamburg Oceanic Carbon Cycle model, HAMOCC 2.0) to assess the impact of such regional deoxygenation on organic carbon burial in the modern ocean on time scales of up to 200 kyrs. We find that an increase in input of phosphorus and iron leads to an expansion of the area of the OMZ impinging on continental margin sediments and a significant decline in bottom water oxygen in the open ocean relative to pre-industrial conditions. The associated increase in organic carbon burial could contribute to the drawdown of ~1,600 Gt of carbon, which is equivalent to the total amount of CO2 in the atmosphere predicted for the year 2100 in a business as usual scenario, on time scales of up to 50 kyrs. The corresponding areal extent of sediments overlain by bottom waters with little or no oxygen as estimated by the model is not very different from the minimum area estimated for two major oceanic anoxic events in Earth's past. Such events were associated with major perturbations of the oceanic carbon cycle, including high rates of organic carbon burial. We conclude that organic carbon burial in low oxygen areas in the ocean could contribute to removal of anthropogenic CO2 from the atmosphere on long time scales.

Oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) in the ocean are currently expanding, likely due to global warming (e.g., Schmittner et al., 2008; Stramma et al., 2010; Cocco et al., 2013; Schmidtko et al., 2017; Breitburg et al., 2018). The long-term climate change initiated by anthropogenic CO2 emissions (Archer, 2005; Eby et al., 2009) is expected to continue in the future (Hansen, 2005; Friedlingstein et al., 2014a). Rising temperatures decrease the solubility of oxygen in surface waters and enhance stratification (Bopp et al., 2002; Stramma et al., 2009) thereby reducing the ventilation of the interior of the ocean. A 1°C warming throughout the upper ocean alone could result in a 3-fold increase in the volume of ocean waters containing <5 μM oxygen (Deutsch et al., 2011). Changes in dissolved oxygen in the ocean have major implications for biogeochemical cycles. Low oxygen levels alter the availability of key nutrients, such as phosphorus, iron and nitrogen (Duce, 1986). This can directly impact the carbon cycle by affecting rates of organic matter production, respiration and burial in the ocean. On time scales of a hundred thousand to a million years, increased burial of organic carbon acts as a sink for CO2 (e.g., Freeman and Hayes, 1992; Kuypers et al., 1999; Barclay et al., 2010) and provides a negative feedback on global warming. Most studies on ocean CO2 sinks on short to long-time scales (e.g., Cox et al., 2000; Archer, 2005; Friedlingstein et al., 2014b) focus on ocean uptake of CO2 through its solubility in seawater, the biological pump, reactions involving CaCO3 and silicate weathering. The role of organic carbon burial as a sink for CO2 in the future ocean has received little attention, despite its potential for long-term carbon storage.

Given current trends in fossil fuel emissions and the slow transition to decarbonization, atmospheric CO2 levels are likely to continue to increase in the near future (Friedlingstein et al., 2014a). After reaching a maximum, CO2 will decrease within a few centuries, but enough CO2 will likely persist on timescales of 100 kyrs to affect climate dynamics (Archer, 2005). The impact on dissolved oxygen is therefore expected to continue far into the future. Many studies have assessed the response of OMZs to climate change over the next 100 to 1,000 years (e.g., Oschlies et al., 2008; Hofmann and Schellnhuber, 2009; Stramma et al., 2010, 2012; Cabré et al., 2015), but only a few have looked into the longer-term consequences. In one such study, Watson et al. (2017), used a biogeochemical box model to assess the response of the ocean to anthropogenically driven phosphorus inputs and concluded that this could lead to an entirely oxygen depleted ocean within 2000 years. Results of several studies with general circulation models including marine biogeochemical processes suggest a significant expansion of OMZs in response to changes in either CO2-driven changes in phosphorus inputs from weathering, ocean circulation or oceanic temperatures on time scales of 10 to 100 kyrs. However, these models do not show evidence for full scale oceanic anoxia (Palastanga et al., 2011, 2013; Beaty et al., 2017; Niemeyer et al., 2017; Kemena et al., 2019).

Besides phosphorus, other nutrients may limit primary productivity, such as iron and nitrogen (Duce, 1986). In fact, most current marine productivity is limited by nitrogen. Whether this will still be the case in the future ocean is uncertain because the nitrogen inventory is strongly affected by ocean deoxygenation (e.g., Deutsch et al., 2007; Gruber, 2011; Oschlies et al., 2019). Moreover, at least 30% of modern marine primary productivity is iron-limited, particularly in the high nitrate, low chlorophyll regions (e.g., Martin et al., 1989, 1990; Martin, 1991; Price et al., 1991, 1994; Moore et al., 2001, 2013). Aeolian dust is a primary source for iron. Dust inputs are largely driven by atmospheric moisture, wind patterns, rainfall, soil moisture and vegetation cover (Duce, 1995), all of which are expected to change in the future. Despite large modeling efforts, predicting future changes in dust inputs remains a challenge (Jickells et al., 2005; Evan et al., 2014; Kok et al., 2018) and global warming may lead to a decrease or an increase in the input of aeolian dust (e.g., Harrison et al., 2001; Mahowald and Luo, 2003; Tegen et al., 2004; Mahowald et al., 2005). The most recent hypothesis is that rates of modern global dust emission may double in at least the next 100 years due to an increase in wind speed and a decrease in soil moisture in key source regions (Kok et al., 2018). Iron inputs from dust lead to important shifts in phytoplankton species and sizes, and alter nitrogen to iron ratios in the ocean. At least 30% of modern marine primary productivity is iron-limited, particularly in the high nitrate, low chlorophyll regions (e.g., Martin et al., 1989, 1990; Martin, 1991; Price et al., 1991, 1994; Moore et al., 2001, 2013). Consequently, changes in the oceanic iron cycle may lead to variability in global rates of ocean productivity, dissolved oxygen concentrations and organic carbon export (Moore et al., 2001, 2013; Altabet et al., 2002). Besides dust, continental margin sediments may also act as a key source of iron to ocean waters, and enhanced future supply to surface waters is expected as OMZs expand (Severmann et al., 2008; Homoky et al., 2012; Henderson et al., 2018).

At present, OMZs have a size of 100 × 106 km3, of which a tenth is considered the ‘core' of the OMZs, characterized by waters with an oxygen concentration of < ~20 μM (Paulmier and Ruiz-Pino, 2009). Permanent OMZs with suboxic cores are located in the Eastern South Pacific, Eastern (Sub-) Tropical North Pacific, Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal, and account for 0.8% of the global ocean's volume. In all areas, except the Eastern Tropical North Pacific, these OMZs also include large areas with permanently anoxic (or nearly anoxic) bottom waters (e.g., Stramma et al., 2008; Paulmier and Ruiz-Pino, 2009). The total area where suboxic or anoxic waters of permanent OMZs impinge on the seafloor is estimated at ~1.15 × 106 km2 (~0.3% of the total ocean floor). Anoxic waters account for 70% of this area (Helly and Levin, 2004). Note that the low oxygen area in the Eastern Atlantic is not considered an OMZ here because its core does not contain <20 μM of oxygen. Since the early 1960s, anoxia has also increased on continental shelves (e.g., Tropical Pacific and Atlantic, Northern Gulf of Mexico, and in coastal waters of Eastern USA, Western and Northern Europe, Korea, China, Taiwan and Japan) and in semi-enclosed basins (e.g., the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, and Mediterranean Sea) as summarized in Stramma et al. (2010) and Breitburg et al. (2018). Due to limitations in spatial resolution, such near coastal areas are not considered in this study.

Oxygen minimum zones play an essential role in the oceanic nitrogen cycle, by contributing to removal of nitrogen through denitrification and anammox and to the release of nitrous oxide, a powerful greenhouse gas (Codispoti et al., 2001). Denitrification requires low oxygen concentrations and is observed in sediments and the water column of OMZs where oxygen concentrations are <20 μM (Smethie, 1987). With the exception of the OMZ in the Eastern Sub-Tropical North Pacific, all permanent OMZs are associated with a denitrification zone. Together, these zones account for a third of the total volume of all OMZ cores (~3.4 million km3; Paulmier and Ruiz-Pino, 2009). The area where benthic denitrification occurs could be larger than that of water column denitrification (DeVries et al., 2013). Moreover, OMZs favor benthic recycling of nutrients (Fisher et al., 1982). In the sediments of OMZs, rates of organic carbon burial are typically enhanced due to a combination of a high primary productivity and increased preservation of organic matter under low oxygen conditions (Emerson, 1985; Arthur et al., 1998; Hedges et al., 2001).

In the geological past, episodes of widespread ocean anoxia that lasted for more than 100 kyrs also led to changes in organic carbon burial (Schlanger and Jenkyns, 1976). Key examples of such episodes are the mid-Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Event 2 (OAE 2; 94 Myr ago) and the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE, 183 Myr). Both events occurred during a period of frequent volcanic activity, high concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and global warming (e.g., Schlanger et al., 1987; Berner, 1992; Hesselbo et al., 2000; Huber et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2002; Kemp et al., 2005). During OAE 2, ~5% of the global sea floor was covered by anoxic and sulfidic bottom waters (Owens et al., 2013, 2016; Dickson et al., 2016). This area is thought to have been mainly limited to the proto-North Atlantic, including various of its continental margins (e.g., Schlanger and Jenkyns, 1976; Ruvalcaba Baroni et al., 2014; van Helmond et al., 2014) whereas the degree of oxygenation of the Pacific Ocean is uncertain. OAE 2 was attributed to a reduced solubility of oxygen due to high sea surface temperatures (Barron et al., 1993) and changes in ocean circulation, enhanced nutrient supply and recycling (e.g., Parrish and Curtis, 1982,?; Föllmi, 1999; Mort et al., 2007; Wagner et al., 2007; Kraal et al., 2010; Trabucho Alexandre et al., 2010; Topper et al., 2011; Poulton et al., 2015). Geochemical analysis revealed high rates of organic carbon burial in both the open and especially the coastal ocean (Owens et al., 2018) with an estimated removal of 26% of atmospheric CO2 during OAE 2 (Barclay et al., 2010).

The exact spatial extent of the anoxia during the T-OAE is less well-known than that for OAE 2. However, geological evidence and model results suggest that during T-OAE protracted anoxia/euxinia was geographically widespread (Gill et al., 2011; Them et al., 2018), but likely mainly confined to relatively shallow areas (e.g., van de Schootbrugge et al., 2005; Dickson et al., 2017). These areas account for at least ~0.3% of the seafloor (Ruvalcaba Baroni et al., 2018) and provide evidence for high rates of organic carbon burial. Trace metal and thallium isotope analysis further suggest that bottom water deoxygenation did not remain constant over the event (e.g., Montero-Serrano et al., 2015; Them et al., 2018). Organic carbon burial during T-OAE is thought to have contributed to at least 8 to 14% of the drawdown of atmospheric CO2 (Xu et al., 2017; Ruvalcaba Baroni et al., 2018). Both OAE 2 and T-OAE share similar biogeochemical characteristics, such as prolonged periods of regional photic zone euxinia, major losses in marine biodiversity, large perturbations in most elemental cycles and high rates of organic carbon burial (e.g., Schlanger and Jenkyns, 1976; Jenkyns, 1985, 2010; McArthur et al., 2008; Dickson et al., 2017).

In this study, we use a biogeochemical model coupled to a general ocean circulation model to assess changes in oxygen and organic carbon dynamics in the modern ocean in response to increased CO2-driven weathering inputs of phosphorus and increased inputs of iron from dust on time scales of up to 200 kyrs. We discuss the effects on ocean deoxygenation, export production and burial of organic carbon and the potential impact on CO2 drawdown from the atmosphere. Our study indicates that long term changes in oxygen concentrations and organic carbon burial in the modern ocean upon continued CO2-emissions could be comparable to those inferred for periods of widespread oceanic anoxia in the geological past.

We use the Hamburg Oceanic Carbon Cycle model (Maier-Reimer et al., 1993) in its annually averaged version (HAMOCC 2.0; Heinze et al., 1999, 2003, 2006), which is specifically designed for long-term integrations. The physical model has a horizontal resolution of 3.5° × 3.5° and includes 11 layers for the oceanic water column with a total ocean surface of 359 301 107 km2, a zonally mixed atmosphere compartment and a bioturbated sediment layer of 10 cm, separated into 11 sublayers. The model assumes a fixed modern ocean circulation and is based on the velocity and thermohaline fields of the Hamburg Large-Scale Geostrophic ocean general circulation model (Maier-Reimer et al., 1993). The biogeochemistry of the model describes the marine carbon, silicon, oxygen and phosphorus cycles (Heinze et al., 1999, 2003, 2006). Sedimentary phosphorus cycling and the oceanic iron cycle were implemented by Palastanga et al. (2011) (P-model) and Palastanga et al. (2013) (PFe-model), respectively. In the later study, the PFe-model was used to study glacial-interglacial variability. Here, we use their model version (that includes both phosphorus and iron) and their preindustrial configuration and apply it to study the modern ocean. For a full description of the model, we refer to these earlier papers.

The model includes both aerobic and anaerobic degradation of organic matter, assuming first-order kinetics, with the anaerobic pathway becoming active when oxygen is nearly depleted (i.e., below 5 μM). Rate constants for aerobic and anaerobic degradation of organic matter vary greatly between different depositional environments (Tromp et al., 1995). Here, rate constants for the aerobic and anaerobic degradation of organic matter were selected based on the best fit of particulate organic carbon (POC) in the surface sediments (Seiter et al., 2004). Differences in values of the first-order rate constants for continental margins (aerobic: 0.01 yr−1; anaerobic: 0.008 yr−1) and the deep sea (aerobic: 0.005 yr−1; anaerobic: 0.002 yr−1) reflect the lower quality of organic matter reaching the seafloor in the latter environment. The model pattern of POC in sediments is in good agreement with global observations of organic carbon contents in surface sediments as demonstrated by Palastanga et al. (2011). Key biogeochemical processes related to sediment phosphorus cycling in the model are degradation of organic phosphorus, precipitation of authigenic carbonate fluorapatite and binding of dissolved phosphate to and release from iron-oxides. The sedimentary iron cycle includes both formation and dissolution of iron oxides. When oxygen falls below 5 μM, anaerobic diagenesis becomes active and both iron and phosphorus are released to the porewater upon dissolution of the iron-oxides. The model simulates mixing and burial of all solid phases and diffusion of solutes. While the release of dissolved phosphate from the sediment to the overlying water is explicitly modeled, that of iron is prescribed using the parameterization of Moore and Braucher (2008). In the model, preferential regeneration of phosphorus in the open ocean accelerates the expansion of anoxia mainly in the eastern and western tropical Pacific Ocean, and the southeastern Pacific sector (Palastanga et al., 2011). Results of sediment phosphorus profiles for the pre-industrial ocean are in good agreement with observations in the open ocean and along continental margins (e.g., Wheat et al., 1996; Harrison et al., 2005; Parekh et al., 2005). For further details on the implementation of the sedimentary processes we refer to the work of Palastanga et al. (2011) and Palastanga et al. (2013) and key references therein (e.g., Ruttenberg and Berner, 1993; Filippelli and Delaney, 1996; Slomp et al., 1996). The model is forced with the preindustrial fields of annual mean ocean circulation from Winguth et al. (1999) and annual mean dust deposition from Mahowald et al. (2006), with a total input of 0.35 Tmol Fe yr−1 (Table 1) as described in detail by Palastanga et al. (2013).

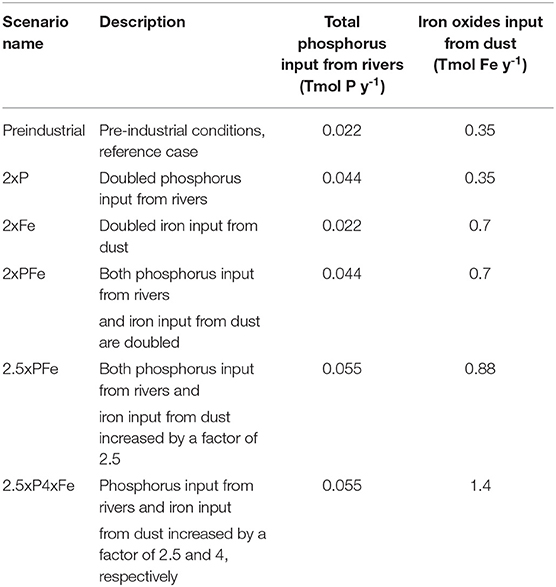

Table 1. Summary of the experiments performed with the model version of Palastanga et al. (2013) (PFe-model).

We performed 5 experiments with the model (Table 1): a preindustrial simulation (Palastanga et al., 2013), an experiment with a 2-fold increase of the input of phosphorus (2xP), an experiment with a 2-fold increase of the input of iron from dust (2xFe), an experiment with a 2-fold increase of the input of phosphorus from rivers and of iron from dust (2xPFe), the same but then with a 2.5-fold increase of both riverine phosphorus and dust iron (2.5xPFe), and finally, an experiment with 2.5-fold increase in phosphorus and 4-fold increase in iron (2.5xP4xFe). The pre-industrial simulation was run over 200 kyrs to ensure near-equilibrium state considering that the residence time of phosphorus in the ocean is about 120 kyrs. The other 4 experiments started from the pre-industrial scenario but with a stepwise increase in the nutrient supply and were further run over 200 kyrs. To assess the role of limitation of oceanic productivity by phosphorus alone vs. limitation by phosphorus and iron upon increased nutrient inputs, we compared the oxygen concentrations and POC export from our 2xPFe experiment to that presented for a doubling of the phosphorus input by Palastanga et al. (2011) (Supplementary Material S1). Due to different model characteristics, such as its horizontal and vertical low resolution, its yearly integrated forcing, its simplified topography and its assumed fixed rate constants for organic carbon degradation, complete loss of oxygen near the seafloor is strongly underestimated in HAMOCC 2.0. Therefore, we consider anoxia to occur when the model oxygen concentrations are close to zero (i.e., below 12 μM) and hereafter use this approximation. Consequently, the terms hypoxia and suboxia here refer to oxygen concentrations that are between 60 and 20 μM and between 20 and 12 μM, respectively. The range of phosphorus inputs from rivers tested here is in line with estimates of the change in rates of weathering for OAE 2 (Blättler et al., 2011). The iron concentrations in dust follow the hypothesis of a future increase in global dust emission as simulated by various Earth System models when forced by a new emission scheme that best captures dust emission measurements (Kok et al., 2018). Note that our 2.5xP4xFe scenario simulates an ocean where primary productivity is less limited by iron than in all other scenarios.

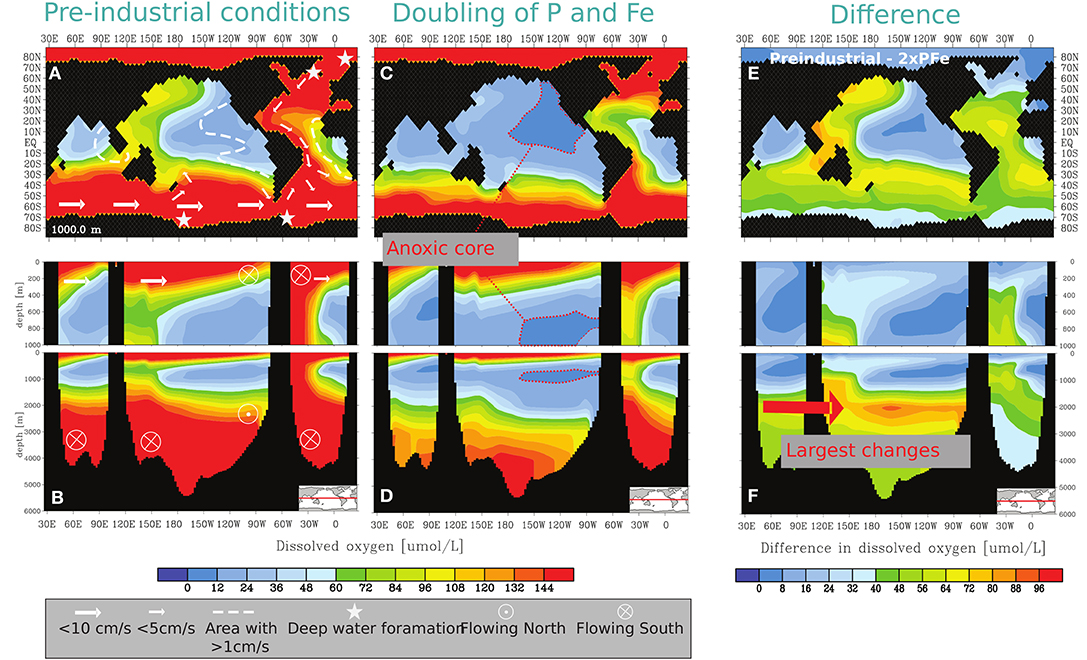

In our pre-industrial simulation (Figures 1A,B), the total volume of the suboxic and anoxic waters of the OMZs are 25.6 × 106 and 3.4 × 106 km3 (Table 2). These volumes account for ~2% and ~0.3% of the total ocean volume, respectively. When compared to recent volume estimates for modern open ocean waters containing <20 μM of O2 (~10.3 × 106 km3 with an average thickness of 340 m–i.e., accounting for 0.8% of the ocean volume; Paulmier and Ruiz-Pino, 2009), our pre-industrial simulation overestimates the volume of suboxic waters by nearly a factor of 3. Anoxic waters are present between water depths of 400 and 900 m over an area of ca. 9.6 × 106 km2, representing about 3% of the total ocean surface (Figures 1A,B and Table 2).

Figure 1. (A,B) Dissolved oxygen concentrations at a water depth of 1,000 m and along an equatorial transect in the Preindustrial scenario and (C,D) in the 2xPFe scenario and (E,F) the difference in dissolved oxygen concentrations between the Preindustrial and the 2xPFe scenario. Both scenarios were integrated for 200 kyrs. A simplified schematic of ocean dynamics, the location of the anoxic core of the Pacific OMZ and the location where the largest changes in oxygen concentrations in intermediate waters are found are indicated in the figure.

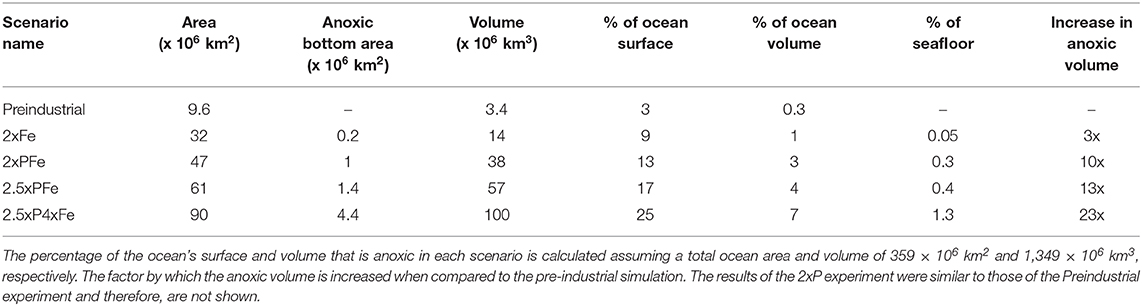

Table 2. Total extent of anoxic waters (<12 μM O2) per experiment after 200 kyrs separated into anoxic ocean area, anoxic bottom area and anoxic ocean volume.

Hypoxic bottom waters containing <60 μM of O2 are present over an area of 3.1 × 106 km2 (~0.6% of the ocean floor), of which 0.1 × 106 km2 contains < ~20 μM of O2 in the model (~0.03% of the ocean floor). The areal extent of naturally occurring suboxic bottom waters on continental margins is on the order of ~1.15 × 106 km2 (Helly and Levin, 2004), which is an order of magnitude higher than what we find in the model. Hence, the model overestimates the volume of the OMZs but underestimates the area where it impinges on the continental margins. Note however, that the bottom area considered in Helly and Levin (2004) may include some shallow areas that cannot be captured by our model resolution.

Upon a 2-fold increase in both phosphorus and iron inputs for 200 kyrs, a significant expansion of low oxygenation occurs when compared to pre-industrial conditions (Figures 1A–D). This expansion is even more pronounced when doubling the riverine phosphorus input in the P-model of Palastanga et al. (2011), as iron in all our scenarios acts as the limiting nutrient for POC export production in most of the ocean (Supplementary Material S1; Figures S1.1, S1.2). Otherwise well-oxygenated intermediate waters in the Southern and Western Pacific, and the Atlantic Ocean show a decrease in oxygen concentrations of ~40 to 70 μM (Figure 1E). Bottom water oxygen concentrations also decrease, with the largest change (of up to 80 μM of O2) observed for tropical and equatorial continental margins (Figure 1F). The most expanded OMZ is that of the Pacific Ocean, where a large anoxic core develops throughout most of the tropical and subtropical regions in the Eastern Pacific (Figure 1C). The volume of suboxic waters with <20 μM increases by a factor of 4.4 relative to the pre-industrial scenario (with a total volume of 128 x 106 km3), whereas the volume of the anoxic core increases by a factor of nearly 10 (Table 2). However, the anoxic volume remains confined to a relatively thin intermediate layer spanning from 450 to 1,000 m (Figure 1D and Figure S2). The sum of all anoxic waters in the 2xPFe experiment covers about 13% of the ocean surface (Figure S2a) with an area of 47 × 106 km2 (Table 2). Low-oxygen conditions in bottom waters increase and anoxic bottom waters now develop covering about 0.3% of the ocean floor (Table 2).

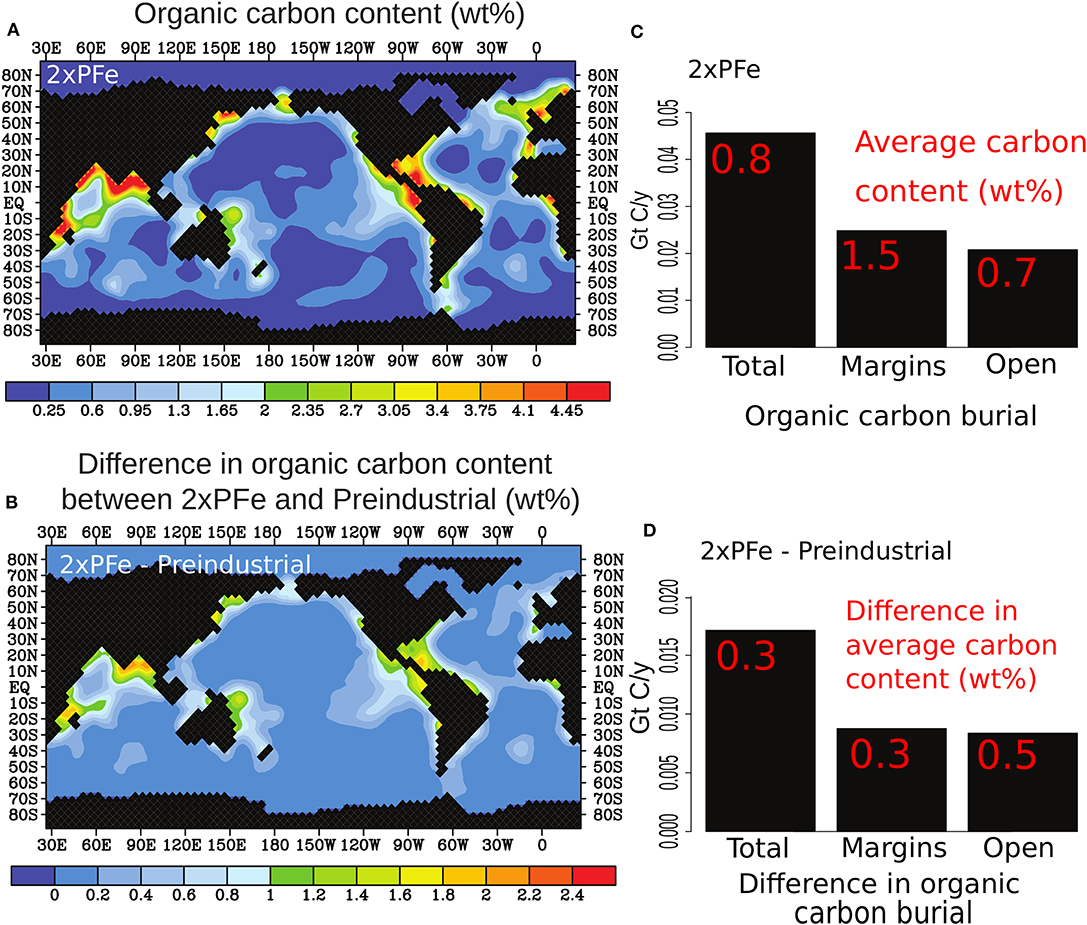

The spatial distribution in organic carbon burial in our 2xPFe scenario is similar to that in the pre-industrial simulation and is characterized by high burial rates on continental margins (Figures 2A,B). In the 2xPFe scenario, on average ca. 33% more organic carbon is buried than during the pre-industrial at a global rate of 0.045 Gt of carbon per year. Maximum carbon contents in sediments of the 2xPFe scenario are 4 wt% (vs. <3 wt% in the pre-industrial run), and are found in sediments of equatorial margins, along the northern margins of the Indian Ocean and eastern margins of the tropical Pacific Ocean, in the Gulf of Mexico and along the margins of northern Europe. In the 2xPFe scenario, the average organic carbon content of sediments at the global scale is ~0.8 wt%, while that for continental margins is 1.5 wt% and that for the open ocean is 0.7 wt% (Figure 2C). In all our scenarios with high nutrient inputs, the increase in organic carbon content in sediments of the open ocean is larger than that of the continental margins when comparing to pre-industrial conditions (e.g., Figure 2D).

Figure 2. (A) Organic carbon content averaged over the sediment layer in the model (10 cm) in the scenario with a doubling of riverine phosphorus and iron dust inputs (2xPFe), (B) difference in the organic carbon content in the 2xPFe scenario relative to the Preindustrial scenario, (C) rate of burial of organic carbon and (in red) average organic carbon content of sediments in the total ocean, on the margins and in the open ocean for the 2xPFe scenario and (D) the differences when compared to pre-industrial values. Results are shown for the run after 200 kyrs.

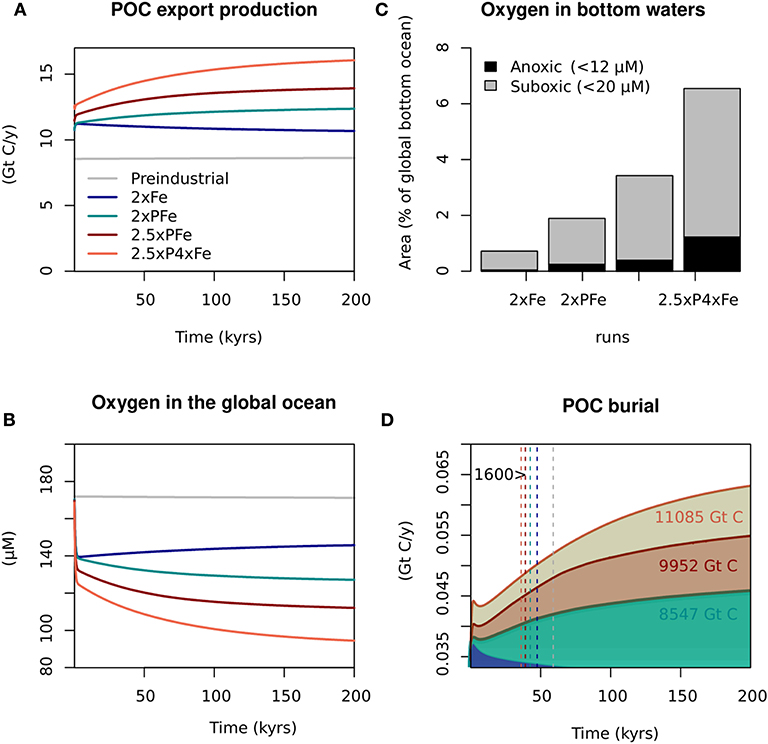

In an ocean where iron is limiting in 85% of the surface ocean, as is the case in the pre-industrial ocean in the model used here, increased iron input leads to an enhanced primary productivity. When, for example, the iron input from dust alone is doubled (2xFe), the area where primary productivity is limited by iron decreases to 65% of the surface ocean. Consequently, POC export production increases by 30% within 10 kyrs. However, a rise in iron alone cannot sustain this production and the iron consumption by primary producers and scavenging by sinking particles (see Palastanga et al. (2013)) leads to a gradual decrease of the iron concentrations by 10% at 200 kyrs (Figure 3A). Changes in oxygen demand follow those in POC export production and global oxygen concentrations rise slightly after an initial decline (Figure 3B). Results of the 2xP experiment are not shown because the lack of iron then limits primary productivity, resulting in rates similar to pre-industrial values. The response to an increase in the input of one single nutrient clearly contrasts with the rise in POC export and decline in oxygen observed when both iron and phosphorus inputs to the ocean are doubled, as in our 2xPFe scenario (Figures 3A,B). The rise in POC export and decline in oxygen is even more pronounced in the scenarios where nutrients are increased by a factor >2 (2.5xPFe and 2.5xP4xFe; Figures 3A,B). The associated increase in oxygen loss below the surface waters in the ocean leads to a major expansion of the OMZs (Figure S2b: depending on the exact scenario, between 1% to 8% of the ocean volume is anoxic at a depth of 1 000 m) and anoxic bottom waters cover between 0.3 to 1.3% of the seafloor (Figure 3C and Table 2). Increased POC export production and oceanic anoxia promote the burial of organic carbon. The cumulative organic carbon burial over 200 kyrs in the scenarios with both increased phosphorus and iron input ranges from 8,547 to 11,085 Gt of carbon (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Particulate organic carbon (POC) and oxygenation for key runs in this study. (A) POC export production, (B) global oxygen concentrations, (C) oxygen concentrations in bottom waters after 200 kyrs and (D) POC burial rates. Colored numbers in (D) indicate the total organic carbon permanently buried during the run (i.e., POC burial rates integrated over 200 kyrs). Colored dashed lines indicate the time needed for each respective scenario to remove 1,600 Gt of atmospheric carbon through organic burial alone.

In all our model experiments with increased phosphorus input, the average phosphorus concentration in the ocean increased during the experiment. This is because iron is limiting in large parts of the ocean and phosphorus is only partially consumed. To illustrate the consequences for the biogeochemistry of the ocean, we compared the results of the 2xPFe scenario (i.e., performed with the PFe-model) to those of the scenario in Palastanga et al. (2011) with a doubling of riverine phosphorus input (i.e., performed with the P-model). We find that in the latter model, the same increase in phosphorus input (i.e., a doubling), when compared to the pre-industrial ocean, leads to lower oxygen concentrations, higher POC export and higher rates of organic carbon burial after 200 kyrs (Figure S1.1).

In our model simulations, increased inputs of iron and phosphorus led to enhanced export production and ocean deoxygenation. Importantly, phosphorus in surface waters was not fully consumed by primary producers and, over time, enhanced riverine phosphorus inputs led to a significant increase in the oceanic phosphorus reservoir. Other biogeochemical ocean models also show such an increase in the global phosphorus inventory in response to increased riverine supply (e.g., Palastanga et al., 2011; Niemeyer et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2017; Kemena et al., 2019). However, the time-scale, magnitude, causes and consequences of the increase in oceanic phosphorus differs between models. Typically, the increase in phosphorus is largest in models where other nutrients, such as nitrogen and iron are also limiting, because this prevents full phosphorus uptake in surface waters. This is illustrated by our comparison of the model results of the P-model of Palastanga et al. (2011) to those of the PFe-model in this study (Figure S1.2). In models that consider phosphorus as the only limiting nutrient, primary productivity mainly follows phosphorus inputs. This may lead to an overestimation of ocean deoxygenation and organic carbon burial.

In our simulations, the productivity in most of the surface ocean is limited by iron, and any additional iron supply is rapidly consumed by primary producers. In the real ocean, spatial differences in iron to carbon ratios and, therefore, in iron limitation depend on the phytoplankton species and size (e.g., Moore et al., 2001, 2013). These effects are not included in our model, therefore, the corresponding detailed spatial variability in iron limitation and primary productivity is not captured in our results. However, future changes in the dust field are highly uncertain and our results show how sensitive the ocean is to dust input in the model: a 2-fold increase leads to a rise in global primary productivity and at least a 3-fold increase in the anoxic water volume in the ocean (Table 2).

Nitrogen also controls primary productivity (Duce, 1986; Tyrrell, 1999; Moore et al., 2013). A direct consequence of an OMZ expansion, such as that observed in our scenarios, is the spreading of its associated denitrification zone (Paulmier and Ruiz-Pino, 2009). The large increase in the anoxic core of the OMZs in our simulations (e.g., of a factor 10 in the 2xPFe scenario; Figure 1 and Table 2) suggests that denitrification in the water column indeed would be enhanced. Benthic denitrification could also increase due to the decline in bottom water oxygen (Middelburg et al., 1996; DeVries et al., 2013). Enhanced N-loss from the ocean and iron supply to the surface waters favor N2-fixation which could more than compensate for the N-loss, especially on long time scales (Codispoti, 1989; Tyrrell, 1999). However, whether such a compensation will actually occur in the future ocean is uncertain.

If we would assume that a doubling of phosphorus and iron inputs from weathering and dust, respectively, as implemented in our model, is a realistic scenario for the future ocean and that phosphorus and iron are the key limiting nutrients, this would imply a major expansion of low oxygen areas in the ocean on time scales of up to 200 kyrs. In our model simulations, low-oxygenated waters in the open ocean expand and spread from existing OMZs. Suboxic and anoxic bottom waters may cover 2 and 0.3% of the ocean's sea floor, respectively. Given that our model underestimates bottom water anoxia, these percentages are rather conservative. Such an oxygen depleted ocean unavoidably leads to major changes in ocean biogeochemistry and to a reduced biodiversity (e.g., Chameides and Perdue, 1997; Vaquer-Sunyer and Duarte, 2008; Wright et al., 2012).

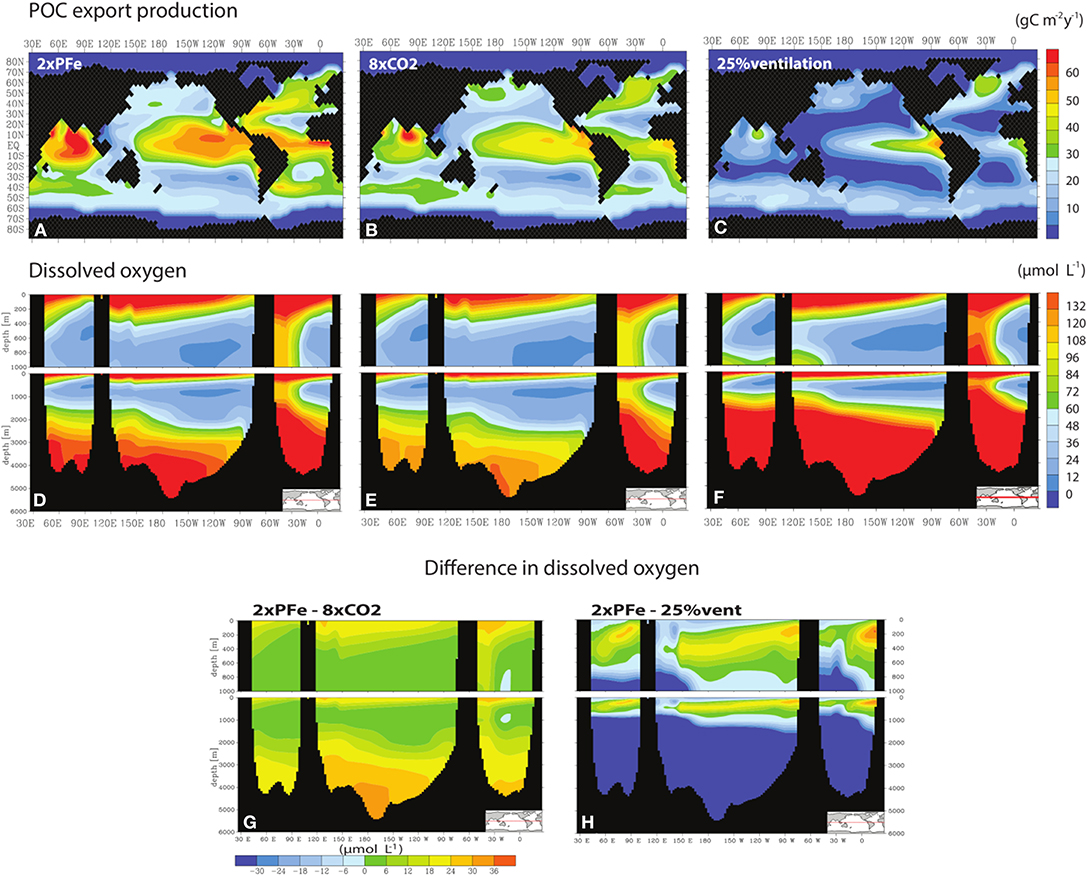

Oxygen concentrations in the ocean depend on the balance between oxygen demand and supply. In our model scenarios, we specifically focused on changes in oxygen demand in intermediate and bottom waters due to nutrient-driven increased export production. Recently, Beaty et al. (2017) used the same model (PFe-model) to assess changes in oxygen supply over 10 kyrs due to increased radiative CO2 forcing (2-8x pre-industrial pCO2 levels), in scenarios where the associated temperature rise affected oxygen solubility, while keeping POC export at pre-industrial values. Comparison of our results for the first 10 kyrs of the scenario with a doubling of nutrients (2xPFe) with these scenarios from Beaty et al. (2017) shows that only their most extreme scenario (8xCO2; i.e., an atmospheric pCO2 of 2238.24 ppmv and change in sea water temperature of 11.5 C°) results in a less-well oxygenated ocean than in our scenario (Figures 4A–D). This illustrates that while a reduced solubility due to warming of surface waters is a key driver of ocean deoxygenation (Bopp et al., 2002; Plattner et al., 2002; Keeling et al., 2009), changes in nutrient supply have the potential to become equally important on long time scales.

Figure 4. POC export production (A–C) and dissolved oxygen concentrations (D–F) after 10 kyrs for our scenario with a doubling of nutrients (2xPFe) and 2 scenarios of Beaty et al. (2017): one with a 8x increase in CO2 radiative forcing (8xCO2) and one with a reduction of 25% in the ocean ventilation (25%vent). Difference in oxygen concentrations (G,H) between our scenario and those of Beaty et al. (2017). Positive values indicate that changes in nutrient-driven oxygen demand are smaller than those in temperature- or ventilation-driven oxygen supply, hence allowing higher concentrations of oxygen to remain. Negative values indicate the opposite.

A striking difference between the results of the 2xPFe and 8xCO2 scenarios is that in the latter scenario bottom water oxygen concentrations in the Pacific Ocean are up to ~30 μM lower (Figures 4D,E,G). This suggests that bottom water concentrations in the ocean are particularly vulnerable to changes in oxygen supply. In a set of additional scenarios, Beaty et al. (2017) also assessed the response of ocean oxygen to a reduced ventilation, without changing the circulation pattern or the mixing due to diffusion. The results of these scenarios reveal that reducing ocean ventilation by up to 75% has a comparatively much smaller effect on oxygen concentrations than changes in oxygen solubility or POC export (Beaty et al., 2017). To illustrate this, we show the results of the scenario for a 25% reduction in ventilation from Beaty et al. (2017) and the difference with our 2xPFe scenario (Figures 4C,F,H). Overall, our results suggest that, on long time scales, increased nutrient input with or without a reduced oxygen solubility could lead to expanded OMZs and low oxygen concentrations in bottom waters, particularly in the Pacific Ocean.

Recent results from an earth-system model simulating global warming on millennial time scales show a gain of ~6% of dissolved oxygen concentrations in the ocean with respect to modern conditions (Oschlies et al., 2019). This gain of oxygen is largely explained by an increase in oxygen in deep waters due to a reduction in the typical aerobic remineralization pathway (which consumes oxygen) which is replaced by the anaerobic denitrification pathway. Additionally, earth-system models under radiative forcing typically show an oxygen gain in the ocean after several thousand years [e.g., about 16% in Ridgwell and Schmidt (2010)]. This has been attributed to warming-induced instabilities of the stratification and its final break down in the Southern Ocean surface. While earth-system models can account for changes in marine oxygen due to both warming and biogeochemistry, they do not yet account for enhanced nutrient supply due to CO2-induced weathering. When comparing our equilibrium results of oxygen concentrations in bottom waters for the 2xPFe and the pre-industrial scenarios (Figure 3B), we obtain a loss of about 25% of oxygen in the global ocean when a doubling of nutrient is applied. This highlights that the loss of oxygen caused by enhanced nutrient supply due to CO2-induced weathering is of the same order of magnitude as the possible gain of oxygen shown by earth-system models. Because all these drivers occur simultaneously but on different time scales, it is possible that on a given time the oxygen loss from enhanced weathering exceeds the oxygen gain. In such case, enhanced nutrient supply due to CO2-induced weathering could lead to widespread deoxygenation, explaining the occurrence of ocean anoxic events.

The modern atmosphere currently contains about ~870 Gt of carbon in the form of CO2 (Pachauri et al., 2014) and this is expected to increase to ca. 1600 Gt by the year 2100 (in a business-as-usual model scenario; Cox et al., 2000). Atmospheric CO2 is removed from the atmosphere by terrestrial and oceanic processes that can act on a range of time-scales and are sensitive to a range of environmental conditions. For example, the solubility of CO2 in seawater decreases with rising sea surface temperatures and is expected to turn the ocean into a less efficient sink for CO2 on decadal time scales (Sabine et al., 2004). In contrast, the rate of silicate weathering is expected to increase upon rising pCO2 and this sets the ultimate maximum duration of the anthropogenic carbon cycle perturbation, acting on timescales of ~100 kyrs (Sundquist, 1991).

Our scenarios show that increased organic carbon burial on continental margins and in the deep ocean could potentially bury 1600 Gt of carbon within 50 ± 10 kyrs (Figure 2 and Figure 3D). This implies that organic carbon burial alone could “permanently” remove all CO2 present in the atmosphere in the year 2100, when assuming no other sources and sinks. In reality, the atmosphere is continuously affected by CO2 fluxes and associated climate feedbacks. The model results suggest that 20 ± 10 kyrs are required to sequester the carbon from anthropogenic emissions (about half of the 1600 Gt) through organic carbon burial alone. The model results also suggest that, besides continental margins, sediments in the deep sea also contribute to organic carbon burial (Figure 2). Since our model does not include near-coastal areas, organic carbon burial on continental margins is likely underestimated.

In the model, the burial of organic carbon in the sediment depends on the input of POC from the overlying water and rates of organic carbon degradation in the sediment. The POC input depends on its export from the surface ocean and hence is critically dependent on nutrient availability, i.e., the assumed increase in river input of phosphorus and dust input of iron. This nutrient input must be sustained, otherwise productivity, ocean oxygen and rates of organic carbon burial will return to pre-industrial values. For example, if nutrient inputs are abruptly returned to pre-industrial inputs, after reaching equilibrium in the 2xPFe scenario, waters at 700 m and 1000 m depth reoxygenate within ~2000 and 500 years, respectively (Figure S3). While a 2-fold sustained increase of phosphorus input due to weathering is in line with the suggested response to high pCO2 based on the geological record (Blättler et al., 2011), the long term changes in input of iron are uncertain.

In the model, anaerobic degradation of organic matter is assumed to be a factor 0.8 and 0.4 slower than aerobic degradation in continental margin and deep sea sediments, respectively. This results in a global increase in POC burial of at least ~30% due to POC preservation under low-oxygen conditions alone. These are relatively conservative estimates for the change in degradation upon oxygen depletion when compared to data for modern systems and other model studies (Canfield, 1994; Hartnett et al., 1998; Moodley et al., 2005; Reed et al., 2011). This implies that our estimates of POC burial could be minimum values. We conclude that enhanced organic carbon burial upon ocean deoxygenation could contribute to long term removal of atmospheric CO2.

In all our scenarios with increased phosphorus and iron inputs, existing OMZs expanded and between 0.3 and 1.3% of the seafloor was covered by anoxic bottom waters after 50 kyrs. This compares well to the known areas with anoxic bottom waters during the Toarcian-OAE and the Cretaceous OAE 2, during which at least ~0.3% (Dickson et al., 2017; Ruvalcaba Baroni et al., 2018) and ~5% (Owens et al., 2013, 2016; Dickson et al., 2016) of the global ocean sea floor was overlain by waters depleted in oxygen, respectively. High atmospheric pCO2 and high rates of nutrient input, sustained over a longer period of time, similar to our scenario for the modern ocean, have been deduced for these past OAEs (e.g., Schlanger and Jenkyns, 1976; Poulsen et al., 2001; Cohen et al., 2004, 2007; Kemp et al., 2005; Barclay et al., 2010; Goddéris et al., 2012; van Bentum et al., 2012; Poulton et al., 2015).

An important difference between our model projections and conditions inferred for the past ocean relates to the location and intensity of the anoxia. In our model results, anoxic bottom waters are observed mostly along continental margins, in particular in the eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean (Figure 1). In our simulations (and those of Beaty et al., 2017), the OMZ expands and bottom water anoxia is most pronounced at intermediate water depths. In such a setting, widespread sulphidic conditions in the water column are unlikely to develop. In contrast, during the Toarcian and Cretaceous OAEs, most of the water column, i.e., from the seafloor to the bottom of the photic zone, was anoxic and sulphidic (e.g., Sinninghe Damsté and Köster, 1998; Dickson et al., 2017). This difference in vertical extent and intensity of the anoxia is likely due to the differences in continental configuration and ocean circulation, allowing parts of the ocean to be more prone to anoxia in the past than today (Donnadieu et al., 2006; Goddéris et al., 2012). During the Toarcian, this holds specifically for the northern European Epicontinental Shelf, which was subject to a flow pattern that promoted the development of anoxia (Ruvalcaba Baroni et al., 2018). During OAE 2, this was the case in the proto-North Atlantic (e.g., Sinninghe Damsté and Köster, 1998; Kuypers et al., 2002; Owens et al., 2013). Sedimentary rock records indicate that large amounts of organic-rich sediments were deposited in low oxygen areas in the ocean during the T-OAE and OAE 2 (Jenkyns, 1985, 2010). This is thought to have led to sequestration of atmospheric CO2 and may have contributed to the termination of these past events (Sinninghe Damsté and Köster, 1998; van Bentum et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2017; Ruvalcaba Baroni et al., 2018).

In our model simulations, we find that 1600 Gt of carbon can be sequestered in the modern ocean during a period of 50 kyrs (Figure 2). To assess whether this is realistic we can compare these values to the estimates of organic carbon burial for the T-OAE and OAE 2. During the T-OAE, the suboxic and anoxic areas on the European shelf alone are thought to have buried 2400 Gt of carbon during a period of 300-500 kyrs (Ruvalcaba Baroni et al., 2018). We note that nothing is known about the burial in other coastal settings and in open ocean environments at this time, hence, the total burial during the T-OAE will likely have been larger. More is known about the burial of organic carbon during OAE 2 and a recent calculation suggests it amounts to at least 41,000 Gt of carbon, as estimated by Owens et al. (2018) for an approximated event duration of 500 kyrs. In our scenarios, the average rate of organic carbon burial in the modern ocean (here, approximated as the final cumulative amount of organic carbon divided by the time of the run) range from ~0.032 to 0.055 Gt C yr−1 (Figure 3D). Our results compare well to the average rate of organic carbon burial estimated during, for example, OAE 2 (41,000 Gt C/500 krsy ≈0.082 Gt C yr−1), and therefore, are not unrealistic. The difference in the average rate of organic carbon burial in the modern ocean vs. that during OAE 2 may be explained by the widespread presence of anoxic and sulphidic bottom waters during the event, which will have promoted preservation of organic matter through sulfidization (e.g., Meyers, 2007; Raven et al., 2018) and, possibly, a higher productivity and hence higher input of organic matter to the sediment Recent findings on OAEs reveal a time lag between marine deoxygenation and significant organic carbon accumulation in sediments (Owens et al., 2016; Ostrander et al., 2017; Them et al., 2018). This suggests that the contribution of organic carbon burial to atmospheric CO2 sequestration became effective only upon widespread deoxygenation and the establishment of anoxic bottom waters. Our scenarios do not show such a time lag. This difference is related to differences in nutrient availability: while in our scenarios, nutrient inputs are elevated from the start of the simulation, in reality, nutrient input are expected to gradually increase and the timing of that increase can determine this time lag. However, we conclude that the rates of organic carbon burial in our scenario are realistic when compared to those for the geological record.

In conclusion, anthropogenic CO2 emissions as considered in the “business as usual” projection (i.e., no reduction of fossil fuel emissions for the next 100 years) could drive the modern ocean toward a state of long-term widespread anoxia and increased organic carbon burial. However, the time scale of recovery from anoxia may be different from that during an OAE. This is because anthropogenic emissions represent a single pulse of CO2 on geological time scales, whereas during the T-OAE and OAE 2, volcanic inputs replenished the CO2 in the atmosphere. Thus, if no new CO2 sources are activated, organic carbon burial could be more efficient as a sink for CO2 in the future ocean than it was in the past. However, this is highly dependent on the response of other natural carbon sources to global warming, such as, for example, the evasion of methane from permafrost, freshwater systems or clathrates, since this will affect the total carbon emission to the atmosphere.

Using a biogeochemical model coupled to a general circulation model for the modern ocean, we show that a long-term increase in nutrient inputs could lead to a major increase in the area and volume of suboxic and anoxic waters in the ocean. Existing oxygen minimum zones are projected to expand, with anoxia potentially impacting more than 20% of the area of the ocean. In all our scenarios, the expanding oxygen minimum zones impinge on the seafloor of continental margins. When accounting for a minimum of a 2-fold increase of nutrient inputs, at least 0.3 to 1.3% of the seafloor becomes covered by anoxic bottom waters.

Ocean deoxygenation is known to lead to major changes in ocean biogeochemistry. One major consequence of the nutrient-driven decline in ocean oxygen in our model is the increase in organic carbon burial on continental margins and in the deep sea. This increase is the combined result of increased production of organic matter in the surface ocean and enhanced preservation of organic matter. Our results suggest that, on a time scale of up to 50 kyrs, this burial of organic matter can significantly contribute to the removal of atmospheric carbon from fossil fuel burning and other human activities. Our results critically depend on increased nutrient inputs from CO2-driven enhanced weathering on land and from dust over longer periods of time. Such long-term changes in nutrient input, anoxic area and organic carbon burial are not unlike those that are thought to have occurred during periods of oceanic anoxia in Earth's past. This implies that modern human activities will likely impact marine life and ocean biogeochemistry beyond timescales of several hundred years and even create a new episode of long-term widespread ocean deoxygenation.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

IR, VP, and CS have made substantial intellectual contributions to this work and approved it for publication.

This research was funded by the Netherlands Earth System Science Centre (NESSC), financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW), and by the European Research Council under the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/200–2013)/ERC Starting Grant # 278364 and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO; Vici grant # 865.13.005).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Christoph Heinze for substantial modeling assistance and Teresa Beaty for providing her modeling results of scenarios with reduced ventilation and increased CO2. The code used in this study is available upon request.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2019.00839/full#supplementary-material

Altabet, M. A., Higginson, M. J., and Murray, D. W. (2002). The effect of millennial-scale changes in Arabian Sea denitrification on atmospheric CO2. Nature 415, 159–162. doi: 10.1038/415159a

Archer, D. (2005). Fate of fossil fuel CO2 in geologic time. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 110:C09S05. doi: 10.1029/2004JC002625

Arthur, M. A., Dean, W. E., and Laarkamp, K. (1998). Organic carbon accumulation and preservation in surface sediments on the Peru margin. Chem. Geol. 152, 273–286.

Barclay, R. S., McElwain, J. C., and Sageman, B. B. (2010). Carbon sequestration activated by a volcanic CO2 pulse during Ocean Anoxic Event 2. Nat. Geosci. 3, 205–208. doi: 10.1038/ngeo757

Barron, E. J., Fawcett, P. J., Pollard, D., Thompson, S., Berger, A., and Valdes, P. (1993). Model simulations of cretaceous climates: the role of geography and carbon dioxide. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 341, 307–316.

Beaty, T., Heinze, C., Hughlett, T., and Winguth, A. M. E. (2017). Response of export production and dissolved oxygen concentrations in oxygenminimum zones to pCO2 and temperature stabilization scenarios in the biogeochemical model HAMOCC 2.0. Biogeosciences 14, 781–797. doi: 10.5194/bg-14-781-2017

Blättler, C. L., Jenkyns, H. C., Reynard, L. M., and Henderson, G. M. (2011). Significant increases in global weathering during Oceanic Anoxic Events 1a and 2 indicated by calcium isotopes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 309, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.06.029

Bopp, L., Le Quéré, C., Heimann, M., Manning, A. C., and Monfray, P. (2002). Climate-induced oceanic oxygen fluxes: implications for the contemporary carbon budget. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 6–1. doi: 10.1029/2001GB001445

Breitburg, D., Levin, L. A., Oschlies, A., Grégoire, M., Chavez, F. P., Conley, D. J., et al. (2018). Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359:eaam7240. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7240

Cabré, A., Marinov, I., Bernardello, R., and Bianchi, D. (2015). Oxygen minimum zones in the tropical Pacific across CMIP5 models: mean state differences and climate change trends. Biogeosciences 12, 5429–5454. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-5429-2015

Canfield, D. E. (1994). Factors influencing organic carbon preservation in marine sediments. Chem. Geol. 114, 315–329.

Chameides, W. L., and Perdue, E. M. (1997). Biogeochemical Cycles: A Computer-Interactive Study of Earth System Science and Global Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cocco, V., Joos, F., Steinacher, M., Frölicher, T. L., Bopp, L., Dunne, J., et al. (2013). Oxygen and indicators of stress for marine life in multi-model global warming projections. Biogeosciences 10, 1849–1868. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-1849-2013

Codispoti, L. A. (1989). “Phosphorus vs. nitrogen limitation of new and export production,” in Productivity of the Ocean: Present and Past, eds W. H. Berger, V. S. Smetacek, and G. Wefer (New York, N: John Wiley), 377–394.

Codispoti, L. A., Brandes, J. A., Christensen, J. P., Devol, A. H., Naqvi, S. W. A., et al. (2001). The oceanic fixed nitrogen and nitrous oxide budgets: moving targets as we enter the anthropocene? Sci. Marina 65, 85–105. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2001.65s285

Cohen, A. S., Coe, A. L., Harding, S. M., and Schwark, L. (2004). Osmium isotope evidence for the regulation of atmospheric CO2 by continental weathering. Geology 32, 157–160. doi: 10.1130/G20158.1

Cohen, A. S., Coe, A. L., and Kemp, D. B. (2007). The Late Palaeocene–Early Eocene and Toarcian (Early Jurassic) carbon isotope excursions: a comparison of their time scales, associated environmental changes, causes and consequences. J. Geolog. Soc. 164, 1093–1108. doi: 10.1144/0016-76492006-123

Cox, P. M., Betts, R. A., Jones, C. D., Spall, S. A., and Totterdell, I. J. (2000). Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature 408, 184–187. doi: 10.1038/35041539

Deutsch, C., Brix, H., Ito, T., Frenzel, H., and Thompson, L. (2011). Climate-forced variability of ocean hypoxia. science 333, 336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1202422

Deutsch, C., Sarmiento, J. L., Sigman, D. M., Gruber, N., and Dunne, J. P. (2007). Spatial coupling of nitrogen inputs and losses in the ocean. Nature 445, 163–167. doi: 10.1038/nature05392

DeVries, T., Deutsch, C., Rafter, P. A., and Primeau, F. (2013). Marine denitrification rates determined from a global 3-D inverse model. Biogeosciences 10, 2481–2494. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-2481-2013

Dickson, A. J., Gill, B. C., Ruhl, M., Jenkyns, H. C., Porcelli, D., Idiz, E., et al. (2017). Molybdenum-isotope chemostratigraphy and paleoceanography of the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (Early Jurassic). Paleoceanog. Paleoclimate 32, 813–829. doi: 10.1002/2016PA003048

Dickson, A. J., Jenkyns, H. C., Porcelli, D., van den Boorn, S., and Idiz, E. (2016). Basin-scale controls on the molybdenum-isotope composition of seawater during Oceanic Anoxic Event 2 (Late Cretaceous). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 178, 291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.12.036

Donnadieu, Y., Pierrehumbert, R., Jacob, R., and Fluteau, F. (2006). Modelling the primary control of paleogeography on cretaceous climate. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett. 248, 426–437. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2006.06.007

Duce, R. A. (1986). “The impact of atmospheric nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron species on marine biological productivity,” in The Role of Air-Sea Exchange in Geochemical Cycling, ed P. Baut-Menard (Dordrecht: Reidel), 497–529.

Duce, R. A. (1995). “Sources, distributions, and fluxes of mineral aerosols and their relationship to climate,” in Dahlem Workshop on Aerosol Forcing of Climate, eds R. J. Charlson and J. Heintzenberg (New York, NY: John Wiley), 43–72.

Eby, M., Zickfeld, K., Montenegro, A., Archer, D., Meissner, K., and Weaver, A. (2009). Lifetime of anthropogenic climate change: millennial time scales of potential CO2 and surface temperature perturbations. J. Climate 22, 2501–2511. doi: 10.1175/2008JCLI2554.1

Emerson, S. (1985). Organic carbon preservation in marine sediments. Carbon Cycle Atmospheric CO2 Nat. Variat. Archean Present 32, 78–87.

Evan, A. T., Flamant, C., Fiedler, S., and Doherty, O. (2014). An analysis of aeolian dust in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 5996–6001. doi: 10.1002/2014GL060545

Filippelli, G. M., and Delaney, M. L. (1996). Phosphorus geochemistry of equatorial Pacific sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60, 1479–1495.

Fisher, T. R., Carlson, P. R., and Barber, R. T. (1982). Sediment nutrient regeneration in three North Carolina estuaries. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 14, 101–116.

Föllmi, K. B. (1999). The phosphorus cycle, phosphogenesis and marine phosphate-rich deposits. Earth Sci. Rev. 40, 55–124.

Freeman, K. H., and Hayes, J. M. (1992). Fractionation of carbon isotopes by phytoplankton and estimates of ancient CO2 levels. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 6, 185–198.

Friedlingstein, P., Andrew, R. M., Rogelj, J., Peters, G., Canadell, J. G., Knutti, R., et al. (2014a). Persistent growth of CO2 emissions and implications for reaching climate targets. Nat. Geosci. 7:709. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2248

Friedlingstein, P., Meinshausen, M., Arora, V. K., Jones, C. D., Anav, A., Liddicoat, S. K., and Knutti, R. (2014b). Uncertainties in CMIP5 climate projections due to carbon cycle feedbacks. J. Clim. 27, 511–526. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00579.1

Gill, B. C., Lyons, T. W., and Jenkyns, H. C. (2011). A global perturbation to the sulfur cycle during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 312, 484–496. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.10.030

Goddéris, Y., Donnadieu, Y., Lefebvre, V., Le Hir, G., and Nardin, E. (2012). Tectonic control of continental weathering, atmospheric CO2, and climate over Phanerozoic times. Compt. Rend. Geosci. 344, 652–662. doi: 10.1016/j.crte.2012.08.009

Gruber, N. (2011). Warming up, turning sour, losing breath: ocean biogeochemistry under global change. Philos. Transact. Roy. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 369, 1980–1996.

Hansen, J. E. (2005). A slippery slope: how much global warming constitutes “dangerous anthropogenic interference?” Clim. Change 68, 269–279. doi: 10.1007/s10584-005-4135-0

Harrison, J. A., Caraco, N., and Seitzinger, S. P. (2005). Global patterns and sources of dissolved organic matter export to the coastal zone: results from a spatially explicit, global model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19, 1–16. doi: 10.1029/2005GB002480

Harrison, S. P., Kohfeld, K. E., Roelandt, C., and Claquin, T. (2001). The role of dust in climate changes today, at the last glacial maximum and in the future. Earth Sci. Rev. 54, 43–80. doi: 10.1016/S0012-8252(01)00041-1

Hartnett, H. E., Keil, R. G., Hedges, J. I., and Devol, A. H. (1998). Influence of oxygen exposure time on organic carbon preservation in continental margin sediments. Nature 391, 572–574.

Hedges, J. I., Baldock, J. A., Gélinas, Y., Lee, C., Peterson, M., and Wakeham, S. G. (2001). Evidence for non-selective preservation of organic matter in sinking marine particles. Nature 409, 801–804. doi: 10.1038/35057247

Heinze, C., Gehlen, M., and Land, C. (2006). On the potential of 230Th, 31Pa, and 10Be for marine rain ratio determinations: a modeling study. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 20, 1–12. doi: 10.1029/2005GB002595

Heinze, C., Hupe, A., Maier-Reimer, E., Dittert, N., and Ragueneau, O. (2003). Sensitivity of the marine biospheric Si cycle for biogeochemical parameter variations. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1–18. doi: 10.1029/2002GB001943

Heinze, C., Maier-Reimer, E., Winguth, A. M., and Archer, D. (1999). A global oceanic sediment model for long–term climate studies. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 13, 221–250.

Helly, J. J., and Levin, L. A. (2004). Global distribution of naturally occurring marine hypoxia on continental margins. Deep Sea Res. I 51, 1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2004.03.009

Henderson, G. M., Achterberg, E. P., and Bopp, L. (2018). Changing trace element cycles in the 21st century ocean. Elem. Int. Magaz. Mineral. Geochem. Petrol. 14, 409–413. doi: 10.2138/gselements.14.6.409

Hesselbo, S. P., Gröcke, D. R., Jenkyns, H. C., Bjerrum, C. J., Farrimond, P., Bell, H. S. M., et al. (2000). Massive dissociation of gas hydrate during a Jurassic oceanic anoxic event. Nature 406, 392–395. doi: 10.1038/35019044

Hofmann, M., and Schellnhuber, H.-J. (2009). Oceanic acidification affects marine carbon pump and triggers extended marine oxygen holes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 106, 3017–3022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813384106

Homoky, W. B., Severmann, S., McManus, J., Berelson, W. M., Riedel, T. E., Statham, P. J., et al. (2012). Dissolved oxygen and suspended particles regulate the benthic flux of iron from continental margins. Mar. Chem. 134, 59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2012.03.003

Huber, B. T., Norris, R. D., and MacLeod, K. G. (2002). Deep-sea palaeotemperature record of extreme warmth during the Cretaceous. Geology 30, 123–126. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0123:DSPROE>2.0.CO;2

Jenkyns, H. C. (1985). The early toarcian and cenomanian-turonian anoxic events in Europe: comparisons and contrasts. Geolog. Rundschau 74, 505–518.

Jenkyns, H. C. (2010). Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 11, 1–30. doi: 10.1029/2009GC002788

Jickells, T., An, Z., Andersen, K. K., Baker, A., Bergametti, G., Brooks, N., et al. (2005). Global iron connections between desert dust, ocean biogeochemistry, and climate. science 308, 67–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1105959

Keeling, R. F., Körtzinger, A., and Gruber, N. (2009). Ocean deoxygenation in a warming world. Ann. Rev.. 2, 199–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163855

Kemena, T. P., Landolfi, A., Oschlies, A., Wallmann, K., and Dale, A. W. (2019). Ocean phosphorus inventory: large uncertainties in future projections on millennial timescales and their consequences for ocean deoxygenation. Earth Syst. Dynam. 10, 539–553. doi: 10.5194/esd-10-539-2019

Kemp, D. B., Coe, A. L., Cohen, A. S., and Schwark, L. (2005). Astronomical pacing of methane release in the Early Jurassic period. Nature 437, 396–399. doi: 10.1038/nature04037

Kok, J. F., Ward, D. S., Mahowald, N. M., and Evan, A. T. (2018). Global and regional importance of the direct dust-climate feedback. Nat. Commun. 9:241. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02620-y

Kraal, P., Slomp, C. P., Forster, A., and Kuypers, M. M. M. (2010). Phosphorus cycling from the margin to abyssal depths in the proto-Atlantic during oceanic anoxic event 2. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 295, 42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.05.014

Kuypers, M. M., Pancost, R. D., and Damste, J. S. S. (1999). A large and abrupt fall in atmospheric CO2 concentration during Cretaceous times. Nature 399:342. doi: 10.1038/20659

Kuypers, M. M. M., Pancost, R. D., Nijenhuis, I. A., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. (2002). Enhanced productivity led to increased organic carbon burial in the euxinic North Atlantic basin during the late Cenomanian oceanic anoxic event. Paleoceanography 17, 1–13. doi: 10.1029/2000PA000569

Mahowald, N. M., Artaxo, P., Baker, A. R., Jickells, T. D., Okin, G. S., Randerson, J. T., et al. (2005). Impacts of biomass burning emissions and land use change on Amazonian atmospheric phosphorus cycling and deposition. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19, 1–15. doi: 10.1029/2005GB002541

Mahowald, N. M., and Luo, C. (2003). A less dusty future? Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1–4. doi: 10.1029/2003GL017880

Mahowald, N. M., Yoshioka, M., Collins, W. D., Conley, A. J., Fillmore, D. W., and Coleman, D. B. (2006). Climate response and radiative forcing from mineral aerosols during the last glacial maximum, pre-industrial, current and doubled-carbon dioxide climates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33. doi: 10.1029/2006GL026126

Maier-Reimer, E., Mikolajewicz, U., and Hasselmann, K. (1993). Mean circulation of the Hamburg LSG OGCM and its sensitivity to the thermohaline surface forcing. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 23, 731–757.

Martin, J. H., Fitzwater, S. E., and Gordon, R. M. (1990). Iron deficiency limits phytoplankton growth in Antarctic waters. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 4, 5–12.

Martin, J. H., Gordon, R. M., Fitzwater, S., and Broenkow, W. W. (1989). VERTEX: phytoplankton/iron studies in the Gulf of Alaska. Deep Sea Res. Part A Oceanogr. Res. Papers 36, 649–680. doi: 10.1016/0198-0149(89)90144-1

McArthur, J., Algeo, T., Van de Schootbrugge, B., Li, Q., and Howarth, R. (2008). Basinal restriction, black shales, Re-Os dating, and the Early Toarcian (Jurassic) Oceanic Anoxic Event. Paleoceanog. Paleoclimate 23. doi: 10.1029/2008PA001607

Meyers, S. R. (2007). Production and preservation of organic matter: the significance of iron. Paleoceanog. Paleoclimatol. 22. doi: 10.1029/2006PA001332

Middelburg, J. J., Soetaert, K., Herman, P. M. J., and Heip, C. H. R. (1996). Denitrification in marine sediments: a model study. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 10, 661–673.

Montero-Serrano, J.-C., Föllmi, K. B., Adatte, T., Spangenberg, J. E., Tribovillard, N., Fantasia, A., et al. (2015). Continental weathering and redox conditions during the early Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event in the northwestern Tethys: insight from the Posidonia Shale section in the Swiss Jura Mountains. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 429, 83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.03.043

Moodley, L., Middelburg, J. J., Herman, P. M., Soetaert, K., and de Lange, G. J. (2005). Oxygenation and organic-matter preservation in marine sediments: Direct experimental evidence from ancient organic carbon–rich deposits. Geology 33, 889–892. doi: 10.1130/G21731.1

Moore, C., Mills, M., Arrigo, K., Berman-Frank, I., Bopp, L., Boyd, P., et al. (2013). Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 701–710. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1765

Moore, J., and Braucher, O. (2008). Sedimentary and mineral dust sources of dissolved iron to the world ocean. Biogeosciences 5, 631–656. doi: 10.5194/bg-5-631-2008

Moore, J. K., Doney, S. C., Glover, D. M., and Fung, I. Y. (2001). Iron cycling and nutrient-limitation patterns in surface waters of the world ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanog. 49, 463–507. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(01)00109-6

Mort, H. P., Adatte, T., Föllmi, K. B., Keller, G., Steinmann, P., Matera, V., et al. (2007). Phosphorus and the roles of productivity and nutrient recycling during oceanic anoxic event 2. Geology 35, 483–486. doi: 10.1130/G23475A.1

Niemeyer, D., Kemena, T. P., Meissner, K. J., and Oschlies, A. (2017). A model study of warming-induced phosphorus–oxygen feedbacks in open-ocean oxygen minimum zones on millennial timescales. Earth Syst. Dynam. 8:357. doi: 10.5194/esd-8-357-2017

Oschlies, A., Koeve, W., Landolfi, A., and Kähler, P. (2019). Loss of fixed nitrogen causes net oxygen gain in a warmer future ocean. Nat. Commun. 10:2805. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10813-w

Oschlies, A., Schulz, K. G., Riebesell, U., and Schmittner, A. (2008). Simulated 21st century's increase in oceanic suboxia by CO2–enhanced biotic carbon export. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22, 1–10. doi: 10.1029/2007GB003147

Ostrander, C. M., Owens, J. D., and Nielsen, S. G. (2017). Constraining the rate of oceanic deoxygenation leading up to a Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Event (OAE-2:˜ 94 Ma). Sci. Adv. 3:e1701020. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701020

Owens, J. D., Gill, B. C., Jenkyns, H. C., Bates, S. M., Severmann, S., Kuypers, M. M., et al. (2013). Sulfur isotopes track the global extent and dynamics of euxinia during Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Event 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 110, 18407–18412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305304110

Owens, J. D., Lyons, T. W., and Lowery, C. M. (2018). Quantifying the missing sink for global organic carbon burial during a Cretaceous oceanic anoxic event. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 499, 83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2018.07.021

Owens, J. D., Reinhard, C. T., Rohrssen, M., Love, G. D., and Lyons, T. W. (2016). Empirical links between trace metal cycling and marine microbial ecology during a large perturbation to earth's carbon cycle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 449, 407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.05.046

Pachauri, R. K., Allen, M. R., Barros, V. R., Broome, J., Cramer, W., Christ, R., et al. (2014). “Climate change 2014 synthesis report. contribution of working groups I, II, and III to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,” in Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report, eds R. Pachauri and L. Meyer (Geneva: IPCC), 151.

Palastanga, V., Slomp, C. P., and Heinze, C. (2011). Long–term controls on ocean phosphorus and oxygen in a global biogeochemical model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 25. doi: 10.1029/2010GB003827

Palastanga, V., Slomp, C. P., and Heinze, C. (2013). Glacial–interglacial variability in ocean oxygen and phosphorus in a global biogeochemical model. Biogeosciences 10, 945–958. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-945-2013

Parekh, P., Follows, M. J., and Boyle, E. A. (2005). Decoupling of iron and phosphate in the global ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19:GB2020. doi: 10.1029/2004GB002280

Parrish, J. T., and Curtis, R. L. (1982). Atmospheric circulation, upwelling, and organic rich rocks in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 40, 31–66.

Paulmier, A., and Ruiz-Pino, D. (2009). Oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) in the modern ocean. Progress Oceanog. 80, 113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2008.08.001

Plattner, G.-K., Joos, F., and Stocker, T. F. (2002). Revision of the global carbon budget due to changing air-sea oxygen fluxes. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 43–1. doi: 10.1029/2001GB001746

Poulsen, C. J., Barron, E. J., Arthur, M. A., and Peterson, W. H. (2001). Response of the mid-Cretaceous global oceanic circulation to tectonic and CO2 forcings. Paleoceanography 16, 576–592. doi: 10.1029/2000PA000579

Poulton, S. W., Henkel, S., März, C., Urquhart, H., Flögel, S., Kasten, S., et al. (2015). A continental-weathering control on orbitally driven redox-nutrient cycling during Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Event 2. Geology 43, 963–966. doi: 10.1130/G36837.1

Price, N., Ahner, B., and Morel, F. (1994). The equatorial Pacific Ocean: grazer-controlled phytoplankton populations in an iron-limited ecosystem 1. Limnol. Oceanog. 39, 520–534.

Price, N. M., Andersen, L. F., and Morel, F. M. (1991). Iron and nitrogen nutrition of equatorial Pacific plankton. Deep Sea Res. Part A Oceanog. Res. Papers 38, 1361–1378.

Raven, M. R., Fike, D. A., Gomes, M. L., Webb, S. M., Bradley, A. S., and McClelland, H.-L. O. (2018). Organic carbon burial during OAE2 driven by changes in the locus of organic matter sulfurization. Nat. Commun. 9:3409. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05943-6

Reed, D. C., Slomp, C. P., and de Lange, G. J. (2011). A quantitative reconstruction of organic matter and nutrient diagenesis in Mediterranean Sea sediments over the Holocene. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 5540–5558. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.07.002

Ridgwell, A., and Schmidt, D. N. (2010). Past constraints on the vulnerability of marine calcifiers to massive carbon dioxide release. Nat. Geosci. 3:196. doi: 10.1038/ngeo755

Ruttenberg, K. C., and Berner, R. A. (1993). Authigenic apatite formation and burial in sediments from non-upwelling, continental margin environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 991–1007.

Ruvalcaba Baroni, I., Pohl, A., van Helmond, N. A., Papadomanolaki, N. M., Coe, A. L., Cohen, A. S., et al. (2018). Ocean circulation in the Toarcian (Early Jurassic): a key control on deoxygenation and carbon burial on the European Shelf. Paleoceanog. Paleoclimatol. 33, 994–1012. doi: 10.1029/2018PA003394

Ruvalcaba Baroni, I., Topper, R. P. M., van Helmond, N. A. G. M., Brinkhuis, H., and Slomp, C. P. (2014). Biogeochemistry of the North Atlantic during oceanic anoxic event 2: role of changes in ocean circulation and phosphorus input. Biogeosciences 11, 977–993. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-977-2014

Sabine, C. L., Feely, R. A., Gruber, N., Key, R. M., Lee, K., Bullister, J. L., et al. (2004). The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Science 305, 367–371. doi: 10.1126/science.1097403

Schlanger, S. O., Arthur, M. A., Jenkyns, H. C., and Scholle, P. A. (1987). The Cenomanian-Turonian Oceanic Anoxic Event, I. Stratigraphy and distribution of organic carbon-rich beds and the marine δ13C excursion. Mar. Petrol. Source Rock Geol. Soc. Special Public. 6, 371–399.

Schlanger, S. O., and Jenkyns, H. C. (1976). Cretaceous oceanic anoxic events: causes and consequences. Geologie en Mijnbouw 55, 179–184.

Schmidtko, S., Stramma, L., and Visbeck, M. (2017). Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature 542:335. doi: 10.1038/nature21399

Schmittner, A., Oschlies, A., Matthews, H. D., and Galbraith, E. D. (2008). Future changes in climate, ocean circulation, ecosystems, and biogeochemical cycling simulated for a business-as-usual CO2 emission scenario until year 4000 AD. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22, 1–21. doi: 10.1029/2007GB002953

Seiter, K., Hensen, C., Schröter, J., and Zabel, M. (2004). Organic carbon content in surface sediments-defining regional provinces. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanog. Res. Papers 51, 2001–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2004.06.014

Severmann, S., Lyons, T. W., Anbar, A., McManus, J., and Gordon, G. (2008). Modern iron isotope perspective on the benthic iron shuttle and the redox evolution of ancient oceans. Geology 36, 487–490. doi: 10.1130/G24670A.1

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. and Köster, J. (1998). A euxinic southern North Atlantic Ocean during the Cenomanian-Turonian oceanic anoxic event. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 158, 165–173.

Slomp, C. P., van der Gaast, S. J., and van Raaphorst, W. (1996). Phosphorus binding by poorly crystalline iron oxides in North Sea sediments. Mar. Chem. 53, 55–73.

Smethie, W. M. (1987). Nutrient regeneration and denitrification in low oxygen fjords. Deep Sea Res. Part A Oceanog. Res. Papers 34, 983–1006.

Stramma, L., Johnson, G. C., Sprintall, J., and Mohrholz, V. (2008). Expanding oxygen–minimum zones in the tropical oceans. Science 320, 655–658. doi: 10.1126/science.1153847

Stramma, L., Oschlies, A., and Schmidtko, S. (2012). Mismatch between observed and modeled trends in dissolved upper–ocean oxygen over the last 50 yr. Biogeosciences 9, 4045–4057. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-4045-2012

Stramma, L., Schmidtko, S., Levin, L. A., and Johnson, G. C. (2010). Ocean oxygen minima expansions and their biological impacts. Deep Sea Res. I 57, 587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2010.01.005

Stramma, L., Visbeck, M., Brandt, P., Tanhua, T., and Wallace, D. (2009). Deoxygenation in the oxygen minimum zone of the eastern tropical North Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, 1–5. doi: 10.1029/2009GL039593

Sundquist, E. T. (1991). Steady-and non-steady-state carbonate-silicate controls on atmospheric CO2. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 283–296.

Tegen, I., Werner, M., Harrison, S., and Kohfeld, K. (2004). Relative importance of climate and land use in determining present and future global soil dust emission. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31. doi: 10.1029/2003GL019216

Them, T. R., Gill, B. C., Caruthers, A. H., Gerhardt, A. M., Gröcke, D. R., Lyons, T. W., et al. (2018). Thallium isotopes reveal protracted anoxia during the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) associated with volcanism, carbon burial, and mass extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, 6596–6601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803478115

Topper, R. P. M., Trabucho Alexandre, J., Tuenter, E., and Meijer, P. Th. (2011). A regional ocean circulation model for the mid-Cretaceous North Atlantic Basin: implications for black shale formation. Clim. Past 7, 277–297. doi: 10.5194/cp-7-277-2011

Trabucho Alexandre, J., Tuenter, E., Henstra, G. A., van der Zwan, K. J., van de Wal, R. S. W., Dijkstra, H. A., et al. (2010). The mid-cretaceous North Atlantic nutrient trap: black shales and OAEs. Paleoceanography 25, 1–14. doi: 10.1029/2010PA001925

Tromp, T., Van Cappellen, P., and Key, R. (1995). A global model for the early diagenesis of organic carbon and organic phosphorus in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 1259–1284.

Tyrrell, T. (1999). The relative influences of nitrogen and phosphorus on oceanic primary production. Nature 400, 525–531.

van Bentum, E. C., Reichart, G.-J., Forster, A., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. (2012). Latitudinal differences in the amplitude of the OAE-2 carbon isotopic excursion: pCO2 and paleo productivity. Biogeosciences 9, 717–731. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-717-2012

van de Schootbrugge, B., McArthur, J. M., Bailey, T., Rosenthal, Y., Wright, J., and Miller, K. (2005). Toarcian oceanic anoxic event: an assessment of global causes using belemnite C isotope records. Paleoceanography 20, 1–10. doi: 10.1029/2004PA001102

van Helmond, N. A., Baroni, I. R., Sluijs, A., Damsté, J. S. S., and Slomp, C. P. (2014). Spatial extent and degree of oxygen depletion in the deep proto-North Atlantic basin during Oceanic Anoxic Event 2. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 15, 4254–4266. doi: 10.1002/2014GC005528

Vaquer-Sunyer, R., and Duarte, C. M. (2008). Thresholds of hypoxia for marine biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15452–15457.

Wagner, T., Wallmann, K., Herrle, J. O., Hofmann, P., and Stuesser, I. (2007). Consequences of moderate 25,000 yr lasting emission of light CO2 into the mid-Cretaceous ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 259, 200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2007.04.045

Watson, A. J., Lenton, T. M., and Mills, B. J. (2017). Ocean deoxygenation, the global phosphorus cycle and the possibility of human-caused large-scale ocean anoxia. Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 375:20160318. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2016.0318

Wheat, C. G., Feely, R. A., and Mottl, M. J. (1996). Phosphate removal by oceanic hydrothermal processes: an update of the phosphorus budget in the oceans. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60, 3593–3608.

Wilson, P. A., Norris, R. D., and Cooper, M. J. (2002). Testing the Cretaceous greenhouse hypothesis using glassy foraminiferal calcite from the core of the Turonian tropics on Demerara Rise. Geology 30, 607–610. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0607:TTCGHU>2.0.CO;2

Winguth, A., Archer, D., Duplessy, J.-C., Maier-Reimer, E., and Mikolajewicz, U. (1999). Sensitivity of paleonutrient tracer distributions and deep-sea circulation to glacial boundary conditions. Paleoceanog. Paleoclimatol. 14, 304–323.

Wright, J. J., Konwar, K. M., and Hallam, S. J. (2012). Microbial ecology of expanding oxygen minimum zones. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 381–394. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2778

Keywords: oxygen minimum zones, ocean deoxygenation, organic carbon burial, nutrient input, bottom water anoxia, long-term carbon dioxide removal, oceanic anoxic events

Citation: Ruvalcaba Baroni I, Palastanga V and Slomp CP (2020) Enhanced Organic Carbon Burial in Sediments of Oxygen Minimum Zones Upon Ocean Deoxygenation. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:839. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00839

Received: 27 June 2019; Accepted: 31 December 2019;

Published: 22 January 2020.

Edited by:

Selvaraj Kandasamy, Xiamen University, ChinaReviewed by: