- 1Red Sea Research Center, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, Saudi Arabia

- 2School of Science, Centre for Marine Ecosystems Research, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA, Australia

- 3School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Centre for Integrative Ecology, Faculty of Science, Engineering and Built Environment, Deakin University, Burwood, VIC, Australia

- 4School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 5Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Silkeborg, Denmark

- 6Arctic Research Centre, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

- 7School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor University, Anglesey, United Kingdom

- 8Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States

- 9Departamento de Edafoloxía e Química Agrícola, Facultade de Bioloxía, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Blue carbon is the organic carbon in oceanic and coastal ecosystems that is captured on centennial to millennial timescales. Maintaining and increasing blue carbon is an integral component of strategies to mitigate global warming. Marine vegetated ecosystems (especially seagrass meadows, mangrove forests, and tidal marshes) are blue carbon hotspots and their degradation and loss worldwide have reduced organic carbon stocks and increased CO2 emissions. Carbon markets, and conservation and restoration schemes aimed at enhancing blue carbon sequestration and avoiding greenhouse gas emissions, will be aided by knowing the provenance and fate of blue carbon. We review and critique current methods and the potential of nascent methods to track the provenance and fate of organic carbon, including: bulk isotopes, compound-specific isotopes, biomarkers, molecular properties, and environmental DNA (eDNA). We find that most studies to date have used bulk isotopes to determine provenance, but this approach often cannot distinguish the contribution of different primary producers to organic carbon in depositional marine environments. Based on our assessment, we recommend application of multiple complementary methods. In particular, the use of carbon and nitrogen isotopes of lipids along with eDNA have a great potential to identify the source and quantify the contribution of different primary producers to sedimentary organic carbon in marine ecosystems. Despite the promising potential of these new techniques, further research is needed to validate them. This critical overview can inform future research to help underpin methodologies for the implementation of blue carbon focused climate change mitigation schemes.

Introduction

Blue carbon ecosystems (i.e., tidal marshes, mangrove and seagrass meadows) constitute hotspots of carbon cycling and are among the largest carbon sinks in the biosphere (Nellemann et al., 2009; Duarte et al., 2013). Among the multiple ecosystem services that coastal vegetated ecosystems provide, the potential to sequester and retain large carbon stocks over millennial timescales has generated interest among scientists and policy makers (Nellemann et al., 2009; Fourqurean et al., 2012; Duarte et al., 2013). Blue carbon strategies describe a range of activities for preventing or mitigating carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions through the conservation and restoration of coastal vegetated ecosystems (Wylie et al., 2016), which rank among the most threatened ecosystems on Earth (Duarte et al., 2013).

The accumulation of carbon stocks is the result of higher accretion rates than decomposition and erosion rates of C-containing materials (detritus and sediment). There are several reasons why blue carbon ecosystems accumulate organic matter and are hotspots of carbon sequestration. First, they are highly productive ecosystems converting CO2 into plant biomass. Second, above-ground macrophyte biomass enhances deposition through altering water flow, and the below-ground biomass reduces erosion and adds organic matter to anoxic soils. These characteristics result in the net accumulation of both living and dead organic material produced within the ecosystem (autochthonous), and/or from external sources (allochthonous) (Kennedy et al., 2010; Saintilan et al., 2013). Third, soils within blue carbon ecosystems have low oxygen concentrations which reduce decomposition, thereby contributing to the accumulation and preservation of organic carbon (Corg) in the marine environment (Nellemann et al., 2009; Mcleod et al., 2011; Duarte et al., 2013). Although soil and sediment can have distinct definitions, we use them interchangeably to facilitate comprehension among different disciplines.

The value of blue carbon ecosystems in sequestering Corg has intensified conservation interests as a measure to mitigate climate change and offset CO2 emissions. However, while both autochthonous and allochthonous sources contribute to the soil Corg pool in blue carbon ecosystems (Kennedy et al., 2010), the presence of allochthonous Corg complicates carbon accounting exercises, because of the risk of duplicating carbon sequestration gains that may have already been accounted for where allochthonous carbon from terrestrial environments is concerned. In contrast, carbon derived from seaweed (Krause-Jensen and Duarte, 2016; Krause-Jensen et al., 2018), epiphytes or plankton, also included in the allochthonous inventory (Kennedy et al., 2010), are not accounted elsewhere and could be included in reports of carbon inventories from blue carbon habitats.

Knowing the origin of Corg (often termed “provenance” within carbon accounting settings) in marine depositional environments is important to decipher biogeochemical cycles and underpin management as it indicates: (1) the key producers of organic matter accumulated within blue carbon ecosystems and other marine depositional environments; (2) the degree of connectivity within and among marine and terrestrial ecosystems; (3) the ultimate fate of the large Corg flux exported from vegetated coastal habitats; and (4) the potential shifts in ecosystem functioning under global change threats.

Knowledge of carbon sources and fluxes among terrestrial and marine ecosystems is useful for managers and policy-makers. This includes the determination of whether local site management is suitable to enhance or maintain blue carbon ecosystems, or whether activities that are off-site, for example those occurring in adjoining watersheds or habitats, are needed to achieve ecosystem management goals. For instance, epiphytic macroalgae are often abundant in seagrass meadows and associated with mangrove areal roots, yet the contribution of algae to soil Corg stocks, food webs or its export to adjacent habitats is debated (Howard et al., 2017). Additionally, carbon from macroalgae (Krause-Jensen and Duarte, 2016) and seagrass (Duarte and Krause-Jensen, 2017) growing in coastal habitats can be found in deep ocean environments, and there is the possibility that carbon from mangroves and tidal marshes is also exported to the deep ocean.

Thus, there is a need to elucidate both the sources of Corg in blue carbon soils as well as the contribution of these habitats and other primary producers to carbon sequestration in depositional environments (Krause-Jensen and Duarte, 2016; Duarte and Krause-Jensen, 2017). Understanding connectivity, in terms of carbon flows across marine ecosystems, is key to support blue carbon accounting as well as the successful management of aquatic ecosystems within land- and seascapes (Smale et al., 2018).

The purpose of this paper is to synthesize existing information on Corg provenance in marine systems and the methods used, and then determine what techniques could be used to improve our understanding of blue carbon sources. Although we focus on well-studied vegetated habitats, depositional environments in the open ocean can also provide an important global sink of blue carbon, including carbon from planktonic sources and carbon exported from blue carbon ecosystems reaching the deep sea (Duarte and Krause-Jensen, 2017). Export of carbon from the surface ocean to oceanic sinks is enhanced by oceanic fronts (Stukel et al., 2017), and marine canyons also concentrate carbon fluxes from coastal vegetated systems to oceanic sinks (Krause-Jensen and Duarte, 2016). Embedding deep ocean sinks into blue carbon frameworks is currently hindered by, among other things, difficulty in identifying the sources of carbon to those sinks (Krause-Jensen et al., 2018). The methods we discuss are also applicable to trace the Corg provenance in the deep ocean and possibly to track oceanic fronts (Khare and Chaturvedi, 2012).

Overview of Blue Carbon Provenance

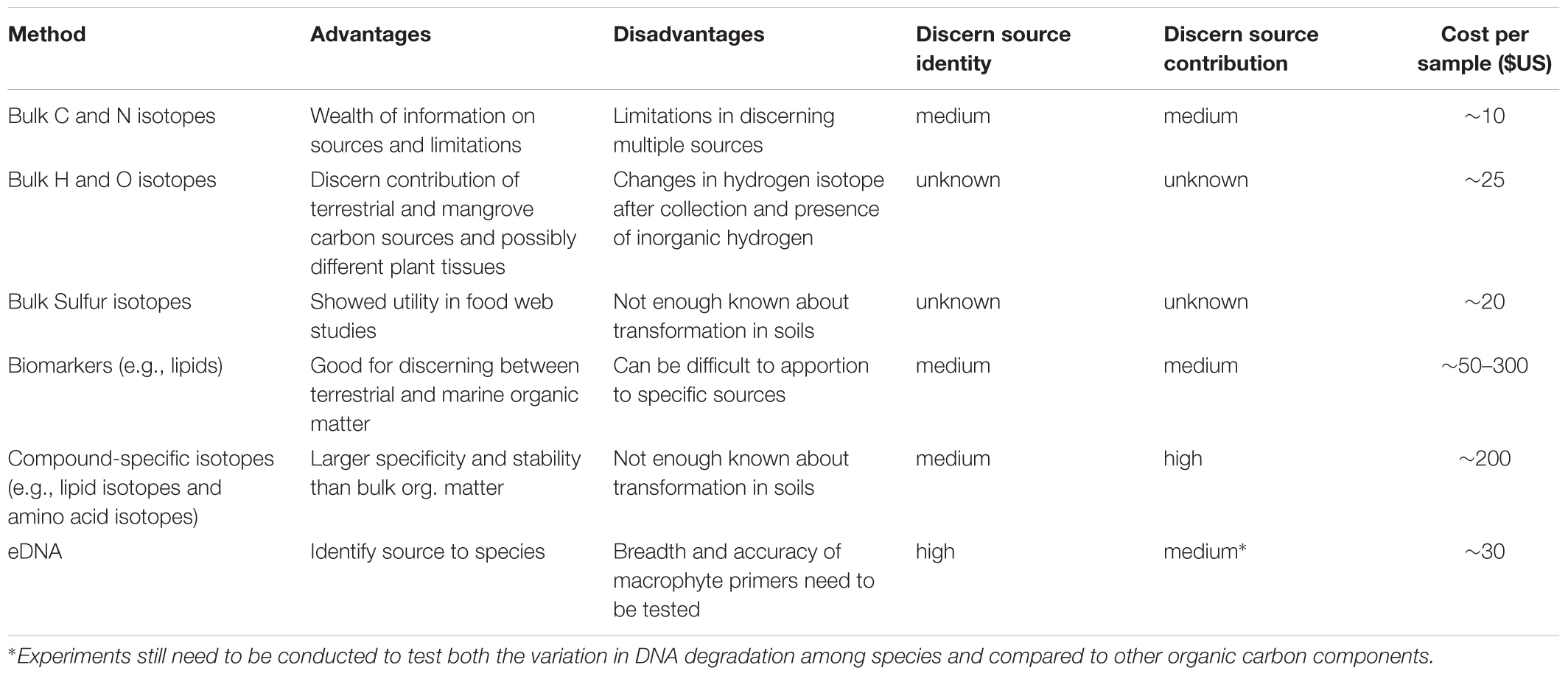

Bulk properties of soils such as C and N elemental (%) and stable isotopic (δ13C and δ15N) composition have been widely tested and used for quantifying sources of organic matter in mangrove, tidal marsh and seagrass soils (Kennedy et al., 2010; Greiner et al., 2016). These tracers have been used to differentiate between terrestrial and marine sources of organic matter (Fry and Sherr, 1989), among marine sources with distinct isotopic ratios such as seagrasses, seston, and macroalgae (e.g., Kennedy et al., 2010; Greiner et al., 2016) and between C3 and C4 vegetation (Smith and Epstein, 1970). Apportioning of organic matter sources using C and N concentration and isotopes depends on: (1) accurate knowledge of potential source values; (2) sources with significantly different values; and (3) the assumption of little or no alteration of source values during decomposition (Fourqurean and Schrlau, 2003; Bouillon et al., 2008). Yet, sources of organic matter in coastal ecosystems can be complex with variable and overlapping isotopic values among plant species, tissues, microhabitats, seasons and growth cycle, which complicates the use of bulk C and N isotopic ratios to discern Corg sources (Marchand et al., 2003; Blair and Aller, 2012). For example, it is difficult to distinguish the contribution of mangrove, tidal marsh and other terrestrial plants to soil Corg using δ13C because these sources have similar isotopic values (Saintilan et al., 2013). Thus, there is a need for methods to complement the information provided by C and N isotopic values (Cloern et al., 2002). Recent studies have highlighted that more specific markers, such as eDNA and compound-specific isotopes, could help reduce uncertainty when determining the sources of Corg (Reef et al., 2017). Therefore, the analyses of additional proxies that are reviewed here, have the potential to greatly enhance our understanding of the fluxes of Corg in marine systems (see Table 1 for summary).

Table 1. Summary of the advantages, and potential limitations for techniques to discern the flow of organic carbon in marine ecosystems.

Recent Developments in Tracing Carbon Provenance

Bulk Hydrogen, Oxygen and Sulfur Isotopes

In addition to δ13C and δ15N isotopic ratios, studies tracing the origin of organic matter in marine and freshwater ecosystems have measured δ18O, δ2H, and δ34S (Peterson and Fry, 1987). The emerging use of δ2H in marine soils has potential to provide evidence for the source of organic matter. δ2H values have been used to measure resource use by aquatic consumers demonstrating the utility of this method to potentially be used to track Corg provenance. For example, a combination of δ2H and C and N isotopes was used to determine clams’ consumption of organic matter derived from macroalgae and microalgae (Hondula and Pace, 2014). Discriminating the diet of clams was possible because microalgae, macroalgae, seagrass and wetland macrophytes differ in δ2H (Hondula and Pace, 2014). In addition, Duarte et al. (2018) recently showed that Red Sea seagrass and macroalgae have distinct δ2H signatures and that the combination of δ2H and δ13C holds promise to discriminate these carbon sources in Corg sediment stocks. Several factors such as photosynthesis, lipid content, isotopic discrimination during water uptake, biochemical and biophysical processes, and environmental seasonality allow differentiation of δ2H values in primary producers (Hondula et al., 2014; Ladd and Sachs, 2015; Adame et al., 2016).

A combination of δ18O with δ2H could be used to determine the provenance of Corg in sediment and although using this combination has not been used for this to our knowledge, the following examples demonstrate its relevance for tracking Corg provenance. While δ18O is not altered upon water uptake by plants (Roden et al., 2000), it is fractionated during photosynthesis leading to variation of δ18O values of plant biomass (Barbour et al., 2007). Variation of δ18O in mangrove woody biomass has been linked to variation in rainfall (Verheyden et al., 2004) and salinity (Ish-Shalom-Gordon et al., 1992). Yet, direct watershed comparison of δ18O of biomass from co-occurring terrestrial and aquatic species are needed to validate this technique. Moreover, the isotopic values of δ2H and δ18O of water in mangrove stem water are distinct from those of adjacent terrestrial plants (Wei et al., 2013) and vary with rainfall and among species (Santini et al., 2015; Lovelock et al., 2017), but direct comparison of isotopic values in water with biomass from the same plants have not yet been made.

There are complexities in using δ18O and δ2H ratios to identify unique carbon sources. First, isotopic composition of primary producers is not universal and second, the source materials are required to determine provenance on a case-by-case basis. Some complications such as the presence of inorganic hydrogen and the exchange of hydrogen after soil collection, may be overcome with the use of stringent extraction and drying methods (Chesson et al., 2009; Meier-Augenstein et al., 2013; Ruppenthal et al., 2013; Soto et al., 2017). However, other complications remain to be solved including measuring only a small fraction of total organic matter due to incomplete extraction (<80% of the total organic matter; Ruppenthal et al., 2013), accounting for source specific element ratios (i.e., C/H and C/O), isolating non-exchangeable H, and determining the effect of bacterial degradation on δ2H and δ18O. While these isotopic tracers are successfully used to study animal movement (Rubenstein and Hobson, 2004) and could assess food web interactions (Zanden et al., 2016), there is little or no information on how bulk values may change during decomposition. In summary, δ2H along with δ18O may be used to determine contribution of different primary producers to organic matter in soils or possibly even organic matter derived from mangrove trees in different environments. However, their use to discriminate sources of Corg in blue carbon sediments has not yet been attempted and the complications mentioned should be addressed to determine the accuracy of these methods.

Measuring sulfur isotopes also has the potential to discriminate sources of Corg in marine depositional environments. Exposure of plant roots to sulfide in marine soils affects their sulfur isotopic values due to incorporation of 34S-depleted sulfides (leading to lower δ34S values), which does not occur in non-rooted primary producers such as macroalgae (Peterson and Fry, 1987). When used in combination with other tracers, sulfur stable isotopes improve the elucidation of sources of organic matter. For instance, Moncreiff and Sullivan (2001) used δ34S, in combination with δ13C and δ15N, to resolve the contribution of seagrass and epiphytic algae to the diet of marine consumers. Connolly et al. (2004) reviewed estuarine and marine food web studies to conclude that the use of δ34S isotopes, in combination with δ13C, yields a high probability of distinguishing the contribution of different producers to aquatic food webs. However, whereas δ34S has been used extensively to resolve food sources in food web studies, the use of this isotope ratio to discriminate sources of Corg in marine soils is more complicated. Soils containing sulfide mineral are common when anoxic conditions pertain in the sediment and these minerals are about 40% depleted in 34S compared to seawater sulfate. Isotopic analysis for δ34S uses roughly the same technology as for δ13C and δ15N, but it is recommended that non-acidified samples are run to maintain the integrity of the soil δ34S for sulfur isotope analysis (Connolly and Schlacher, 2013), and if bulk soil is analyzed the resultant δ34S values is a measure of both inorganic and organic sulfur isotopic composition which can be much more isotopically depleted than any of the potential Corg sources (Oreska et al., 2018). Although this represents an untapped research opportunity, a first step would be to employ methodology that separates inorganic from organic sulfur in the soils prior to analysis. In addition, it remains to be investigated how the incorporation of reduced sulfur into organic matter affects the δ34S of Corg during diagenesis.

Molecular Properties of Bulk Organic Matter

There are multiple methods to characterize the chemical composition of organic carbon in soils (Derrien et al., 2017). The most common sources of organic matter in blue carbon ecosystems (vascular plants, macroalgae, phytoplankton, fungi, bacteria, zooplankton, etc.) can have different biopolymer chemical composition (e.g., polysaccharides, proteins, lignin, chitin, peptidoglycan). Differences in biopolymer identity and abundance can be analyzed with infrared spectroscopy (IR) to characterize marine Corg (Benner et al., 1992; Trevathan-Tackett et al., 2017). IR is a rapid, non-destructive and cost-efficient method and is therefore a very useful tool for bulk chemical characterization of blue carbon. However, a disadvantage of using IR is that some sources can have similar biopolymer fingerprints. Another complementary method to characterize the composition of Corg is nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (solid-state 13C NMR). Broad morphological, physical and chemical characteristics of organic matter fractions can be determined with 13C NMR, including dissolved and particulate Corg, and recalcitrant organic matter. Although 13C NMR has been used to describe Corg in terrestrial soils (Baldock et al., 2004), the use in marine systems maybe more complex because the marine Corg often undergoes greater levels of processing before deposition compared to Corg in terrestrial systems (Baldock et al., 2004; Hayes et al., 2017; Kelleway et al., 2017; Macreadie et al., 2017). An area for future research is to develop molecular mixing models with the application of chemometric approaches (Doucet et al., 2008) based on both IR and NMR results to characterize blue carbon sources.

Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) can also be applied to blue carbon fingerprinting. Similarly, pyrolysis has been used to discern allochthonous and autochthonous organic matter in mangrove soils (Marchand et al., 2008). GC-MS can identify the thermal or chemical degradation of macromolecules. For example, lignin composition differs between angiosperms vs. gymnosperms and between woody tissues vs. non-woody tissues (Haddad and Martens, 1987). Thus, lignin can be analyzed by GC-MS after cupric oxide oxidation, which can provide information on the abundance and source of plant material. Lignin can also be analyzed by thermal degradation using analytical pyrolysis which can then be analyzed with GC-MS (Py-GC-MS; Carr et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016). Due to the invasive nature of pyrolytic breakdown, Py-GC-MS is quantitatively weak but has the advantage that it also provides information on other macromolecular materials, such as polysaccharides, proteins, chitin (in zooplankton and fungi), peptidoglycan (in bacteria), chlorophyll (in phytoplankton), charred organic matter (an important type of recalcitrant organic matter) and others (e.g., cutin, suberin, algaenan, and tannin; Carr et al., 2010 and references therein). Such information can be useful not only as a molecular screening method to identify sources, but can also be used to compliment or validate less complex data from IR, elemental or isotopic analysis. Analysis of the molecular properties of bulk organic matter does necessitate specific and advanced analytical methodologies such as IR, NMR, GC-MS, and PY-GC-MS.

Biomarkers (Targeted Compounds)

Biomarkers, such as n-alkanes and phenolic compounds, have been proposed as taxonomic fingerprints and the biomarker profile of some marine primary producers has been characterized (Zidorn, 2016; Gachet et al., 2017). Lipids can provide convenient biomarkers to trace the source and fate of Corg and have great potential as a molecular biomarker for coastal systems (Derrien et al., 2017). For example, n-alkanes lipids together with stable C and N isotopic compositions, have been used to quantify the source of Corg along estuarine gradients (Jaffé et al., 2001; He et al., 2014). In addition, n-alkanes can indicate the relative proportion of terrestrial and marine sources of organic matter (Silliman et al., 1996; Ortiz et al., 2013) and can differentiate the source of organic matter within coastal systems among terrestrial sources, emergent aquatic plants, and submerged macrophytes (Sikes et al., 2009). Other compounds with the potential to fingerprinting Corg include proteins, such as glomalin which has been used to indicate terrestrial-derived carbon in blue carbon soils (Adame et al., 2012; López-Merino et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). In general, biogeochemical plasticity of biomarkers can exist within species based on their geographical distribution and through time (Derrien et al., 2017). Similar to molecular properties of bulk organic matter, biomarker analysis requires advanced analytical methodologies, for example liquid chromatography (LC, HPLC), GC and MS. Biogeochemical plasticity of biomarkers can exist within species based on their geographical distribution and through time (Derrien et al., 2017). A recent review provides a good overview of using biomarkers to trace organic matter (Derrien et al., 2017). To date, few studies have used this approach to fingerprint sources of Corg in blue carbon soils, and some studies have used biomarkers in combination with compound-specific isotopes (Apostolopoulou et al., 2015).

Compound-Specific Isotopes (Amino Acids, Carbohydrates, Lipids)

Compound-specific stable isotopes of organic matter can enable the molecular specificity and isotopic value of compounds to be exploited concomitantly to trace the origin and fate of organic matter (Evershed et al., 2007; Chikaraishi, 2014). Many types of amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipids have been used for isotopic fingerprinting and to trace Corg sources through food webs (De Troch et al., 2012; Larsen et al., 2013), with the finding that they seem to be considerably more stable and specific than that of the bulk organic matter (Larsen et al., 2015). The δ13C and δ2H values of sterols in living algae are consistent with those found in marine sediments, suggesting that the isotopic compositions of algal sterols are well-preserved in sediments and therefore could be used as tracers of Corg origin (Chikaraishi, 2006). Lastly, isotopes of amino acids, have also been identified as a powerful tracer of material origin, because environmental conditions have a minimal effect on δ13C patterns of different amino acids in seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) and giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) (Larsen et al., 2013). Thus, patterns of δ13C among individual amino acids have a much greater potential than bulk δ13C to distinguish between Corg derived from algae, seagrass, terrestrial plants, bacteria and fungi (Larsen et al., 2013). Over time, sedimentary diagenesis may lead to increased contribution of bacterial sources (Larsen et al., 2015), but the method still seems a promising complementary approach to overcome some of the limitations of bulk isotope analysis in estuaries and other complex environments with mixed aquatic and terrestrial inputs for determining the origin of organic matter. A few studies have used both bulk and compound-specific isotopes to track changes in the provenance of blue carbon including stable isotopes within higher plant leaf wax lipids (Johnson et al., 2007) or n-alkanes (Tanner et al., 2010).

Environmental DNA

Fingerprinting marine organisms through environmental DNA (eDNA) has recently become a widely used technique to determine the presence and abundance of individual macroorganisms (Rees et al., 2014; Thomsen and Willerslev, 2015). Most of the marine research using eDNA has targeted macrofauna, while minimal attention has been given to macroflora (Thomsen and Willerslev, 2015; Goldberg et al., 2016), with only one paper to our knowledge on eDNA of macrophytes in marine sediments (Reef et al., 2017). Given that approximately 3% of cellular Corg is DNA (Landenmark et al., 2015) and that eDNA can identify individual species, this approach has great potential for determining the provenance of Corg in soils of blue carbon ecosystems. In aquatic environments, phytoplankton identified from eDNA isolated from sediments in deep water were representative of the pelagic community (Corinaldesi et al., 2011; Capo et al., 2015). However, eDNA analysis may underrepresent phytoplankton that lack hard structures (Boere et al., 2011b), and underrepresent phytoplankton compared to terrestrial plants (Boere et al., 2011a), due to differential preservation of their DNA. Currently, the sole study using eDNA to measure the provenance of blue carbon found that seagrass meadows had a greater input of autochthonous Corg based on eDNA than when sources of Corg where estimated using δ13C and δ15N (Reef et al., 2017). This discrepancy between methods highlights the need to experimentally test the relationship between bulk organic carbon sources and sequenced eDNA during diagenesis at different timescales.

The basic steps in analyzing eDNA using metabarcoding include isolating DNA from sediment, replicating target DNA sequences through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), determining the base pairs of the replicated sequences using next generation sequencing, and matching the sequences to known taxa. The relationship between eDNA and natural abundance is better when focusing on single taxon or species using quantitative PCR or related techniques (Yates et al., 2019), as compared to using PCR and metabarcoding which may not have a relationship between initial DNA concentration and final sequences but have the benefit of uniquely identifying many species in a single sample. To relate the number of DNA sequences to the abundance of organisms based on metabarcoding, knowledge of the factors that affect eDNA quantity in sediment and PCR bias (i.e., the preferential replication of some DNA sequences relative to others) should be identified and measured (Yoccoz et al., 2012). When using eDNA reads as an indicator of blue carbon provenance, the factors that may alter the relationship between DNA and Corg should also be understood. Potential artifacts that deserve attention when using eDNA to track blue carbon include: (1) DNA may degrade at a faster rate than other Corg components, such as carbohydrates and other macromolecules (Volkman, 2006), so there is the potential for eDNA to underestimate allochthonous Corg and species with relatively less resistant cellular structure (e.g., algae vs. vascular plants); (2) primers need to be tested to ensure that the species thought to contribute to the Corg in soil are amplified because primer amplification is imperfect (Deagle et al., 2014); (3) the initial and amplified number of sequences may not be related when using PCR (Acinas et al., 2005); and (4) accurate fingerprinting requires that sequences for the putative source primary producers be deposited in reference data banks, which is not always the case. Recent studies have used mock samples to assess whether PCR amplicons are related to initial DNA concentration, finding that this relationship does exist for most species (Thomsen et al., 2016). Given that eDNA within aquatic sediments have been used to track changes over millennia in the surrounding terrestrial and aquatic autotroph communities (Capo et al., 2015; Sjögren et al., 2016) and Corg contributions (Coolen et al., 2007; Boere et al., 2011a), there is great potential for using eDNA to track the provenance and fate of Corg within blue carbon ecosystems (Reef et al., 2017). The potential resolution of eDNA to detail carbon contribution to species level, makes this approach unparalleled by any other approach used to fingerprint the sources of Corg in blue carbon soils. However, the limitations mentioned when using PCR should be addressed before inferring a relationship between metabarcoding results and contribution of Corg.

Common Methodological Issues

The disparate techniques described here share limitations that can likely be addressed to improve our ability to determine the provenance of sequestered Corg in the marine environment (Table 1). First, all the techniques assume conserved relationships between the source of specific markers and those in sedimentary Corg pools, yet changes in the markers through space and time may occur, hence these changes need to be quantified. Thus, some of these methods should be considered qualitative or semi-quantitative until this assumption has been tested. Second, all methods are based on known standards, such as a comprehensive library of known DNA sequences, isotopic values of source materials or biomarker profiles, and it requires a community effort to develop and expand these standards so as to enable the full power of these techniques. Third, these methods often depend on large databases and/or necessitate computationally intensive programs to match samples with standards. For example, mixing models are often used for stable isotopes but have multiple limitations (Fry, 2013), and advances have been made such as Bayesian methods that can include additional information to reduce uncertainty in undetermined systems (Moore and Semmens, 2008). Mixing models for isotope ratios of specific compounds are less developed than for bulk isotope ratios and need further refinement to validate their use. Finally, methods are constantly being developed and specialized to determine Corg properties and many are associated with specialized equipment that can be esoteric and too expensive for many researchers (see Table 1 for estimated cost). However, as is the case with DNA sequencing, many methods have and will become available to a broader scientific community as technology improves and costs continue to decrease, a consequence of the increasingly large number of researchers using these techniques.

Conclusion

We reviewed and critiqued multiple methods that have the potential to improve our understanding of the provenance and fate of Corg within and among coastal ecosystems. Our goal is to encourage research aimed at improving the assessment of the Corg origin in blue carbon ecosystems which is needed to decipher biogeochemical cycles and underpin management such as blue carbon initiatives. This advance would include assessment of species of macroalgae, microphytobenthos and epifauna, which can have high production rates, but their contribution to blue carbon has been illusive because of current limitations in tracking their origin and fate. In addition, recent research has suggested that coastal primary producers, such as macroalgae and seagrass, could significantly contribute to Corg sequestration beyond their habitat, including in the deep ocean (Krause-Jensen and Duarte, 2016; Duarte and Krause-Jensen, 2017), but direct measures of their contribution are limited at best. The ability to accurately determine the identity and contribution of primary producers to soil Corg will likely depend on a combination of the previously discussed methods that minimize the associated limitations. In our opinion, the methodologies with the greatest potential to determine the provenance of soil Corg are the C and N stable isotopes of lipids to determine the quantity of discerned taxa in combination with eDNA to identify the species that contribute to the isotopic composition. The ability to mitigate the negative effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 can be aided by management schemes that maintain existing carbon storage and promote carbon sequestration. The marine environment, and blue carbon ecosystems in particular, are hotspots of carbon storage. Enhanced knowledge of the sources and fate of Corg stored in marine sediments is important for both managing coastal carbon stocks and understanding carbon cycling.

Author Contributions

NG and CD conceived the idea of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and revising of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was initiated at the Blue Carbon Workshop held at KAUST on March 19th to the 23rd 2017 and was funded by KAUST. NG and CD were supported by KAUST through baseline funding and by the Tarek Ahmed Juffali Research Chair in Red Sea Ecology to CD. OS was supported by an ARC DECRA DE170101524. PM and CL acknowledge the support of an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant – LP160100242. HK was supported by the Ecosystem Services for Poverty Alleviation program Coastal Ecosystem Services in East Africa (NE/L001535/1). DK-J was supported by the Danish Center of the Environment’s eDNA synergy project and by the COCOA project under the BONUS program funded by the EU 7th framework program and the former Danish Research Council. MP was supported by the NSF Virginia Coast Reserve LTER project (DEB1237733 and DEB1832221).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Acinas, S. G., Sarma-Rupavtarm, R., Klepac-Ceraj, V., and Polz, M. F. (2005). PCR-induced sequence artifacts and bias: insights from comparison of two 16s rRNA clone libraries constructed from the same sample. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8966–8969. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8966-8969.2005

Adame, M. F., Fry, B., and Bunn, S. E. (2016). Water isotope characteristics of a flood: brisbane river, Australia. Hydrol. Process. 30, 2033–2041. doi: 10.1002/hyp.10761

Adame, M. F., Wright, S. F., Grinham, A., Lobb, K., Reymond, C. E., and Lovelock, C. E. (2012). Terrestrial–marine connectivity: patterns of terrestrial soil carbon deposition in coastal sediments determined by analysis of glomalin related soil protein. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 1492–1502. doi: 10.4319/lo.2012.57.5.1492

Apostolopoulou, M.-V., Monteyne, E., Krikonis, K., Pavlopoulos, K., Roose, P., and Dehairs, F. (2015). n-Alkanes and stable C, N isotopic compositions as identifiers of organic matter sources in Posidonia oceanica meadows of Alexandroupolis Gulf, NE Greece. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 99, 346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.07.033

Baldock, J. A., Masiello, C. A., Gélinas, Y., and Hedges, J. I. (2004). Cycling and composition of organic matter in terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Mar. Chem. 92, 39–64. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2004.06.016

Barbour, M. M., Farquhar, G. D., Hanson, D. T., Bickford, C. P., Powers, H., and Mcdowell, N. G. (2007). A new measurement technique reveals temporal variation in δ18O of leaf-respired CO2. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 456–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01633.x

Benner, R., Pakulski, J. D., Mccarthy, M., Hedges, J. I., and Hatcher, P. G. (1992). Bulk chemical characteristics of dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Science 255, 1561–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.255.5051.1561

Blair, N. E., and Aller, R. C. (2012). The fate of terrestrial organic carbon in the marine environment. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 4, 401–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142717

Boere, A. C., Rijpstra, W. I. C., De Lange, G. J., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Coolen, M. J. L. (2011a). Preservation potential of ancient plankton DNA in pleistocene marine sediments. Geobiology 9, 377–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2011.00290.x

Boere, A. C., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Volkman, J. K., and Coolen, M. J. L. (2011b). Source-specific variability in post-depositional DNA preservation with potential implications for DNA based paleoecological records. Org. Geochem. 42, 1216–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2011.08.005

Bouillon, S., Borges, A. V., Castañeda-Moya, E., Diele, K., Dittmar, T., Duke, N. C., et al. (2008). Mangrove production and carbon sinks: a revision of global budget estimates. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22:GB2013. doi: 10.1029/2007GB003052

Capo, E., Debroas, D., Arnaud, F., and Domaizon, I. (2015). Is planktonic diversity well recorded in sedimentary DNA? Toward the reconstruction of past protistan diversity. Microb. Ecol. 70, 865–875. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0627-2

Carr, A. S., Boom, A., Chase, B. M., Roberts, D. L., and Roberts, Z. E. (2010). Molecular fingerprinting of wetland organic matter using pyrolysis-GC/MS: an example from the southern cape coastline of South Africa. J. Paleolimnol. 44, 947–961. doi: 10.1007/s10933-010-9466-9

Chesson, L. A., Podlesak, D. W., Cerling, T. E., and Ehleringer, J. R. (2009). Evaluating uncertainty in the calculation of non-exchangeable hydrogen fractions within organic materials. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23, 1275–1280. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4000

Chikaraishi, Y. (2006). Carbon and hydrogen isotopic composition of sterols in natural marine brown and red macroalgae and associated shellfish. Org. Geochem. 37, 428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2005.12.006

Chikaraishi, Y. (2014). “Treatise on geochemistry,” in Treatise on Geochemistry—Organic Geochemistry, 2nd Edn, eds K. Turekian and H. Holland (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 95–123.

Cloern, J. E., Canuel, E. A., and Harris, D. (2002). Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope composition of aquatic and terrestrial plants of the San Francisco Bay estuarine system. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47, 713–729. doi: 10.4319/lo.2002.47.3.0713

Connolly, R. M., Guest, M. A., Melville, A. J., and Oakes, J. M. (2004). Sulfur stable isotopes separate producers in marine food-web analysis. Oecologia 138, 161–167. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1415-0

Connolly, R. M., and Schlacher, T. A. (2013). Sample acidification significantly alters stable isotope ratios of sulfur in aquatic plants and animals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 493, 1–8. doi: 10.3354/meps10560

Coolen, M. J. L., Volkman, J. K., Abbas, B., Muyzer, G., Schouten, S., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. (2007). Identification of organic matter sources in sulfidic late Holocene Antarctic fjord sediments from fossil rDNA sequence analysis. Paleoceanography 22:A2211. doi: 10.1029/2006PA001309

Corinaldesi, C., Barucca, M., Luna, G. M., and Dell’anno, A. (2011). Preservation, origin and genetic imprint of extracellular DNA in permanently anoxic deep-sea sediments. Mol. Ecol. 20, 642–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04958.x

De Troch, M., Boeckx, P., Cnudde, C., Van Gansbeke, D., Vanreusel, A., Vincx, M., et al. (2012). Bioconversion of fatty acids at the basis of marine food webs: insights from a compound-specific stable isotope analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 465, 53–67. doi: 10.3354/meps09920

Deagle, B. E., Jarman, S. N., Coissac, E., Pompanon, F., and Taberlet, P. (2014). DNA metabarcoding and the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I marker: not a perfect match. Biol. Lett. 10:20140562. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0562

Derrien, M., Yang, L., and Hur, J. (2017). Lipid biomarkers and spectroscopic indices for identifying organic matter sources in aquatic environments: a review. Water Res. 112, 58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.023

Doucet, F. R., Faustino, P. J., Sabsabi, M., and Lyon, R. C. (2008). Quantitative molecular analysis with molecular bands emission using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy and chemometrics. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 23, 694–701. doi: 10.1039/B714219F

Duarte, C. M., Delgado-Huertas, A., Anton, A., Carrillo-de-Albornoz, P., López-Sandoval, D. C., Agustí, S., et al. (2018). Stable Isotope (δ13C, δ15N, δ18O, δD) composition and nutrient concentration of red sea primary producers. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:298. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00298

Duarte, C. M., and Krause-Jensen, D. (2017). Export from seagrass meadows contributes to marine carbon sequestration. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:13. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00013

Duarte, C. M., Losada, I. J., Hendriks, I. E., Mazarrasa, I., and Marbà, N. (2013). The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 961–968. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1970

Evershed, R. P., Bull, I. D., Corr, L. T., Crossman, Z. M., van Dongen, B. E., Evans, C. J., et al. (2007). “Compound-specific stable isotope analysis in ecology and paleoecology,” in Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science, eds R. Michener and K. Lajtha (Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd), 480–540. doi: 10.1002/9780470691854.ch14

Fourqurean, J. W., Duarte, C. M., Kennedy, H., Marbà, N., Holmer, M., Mateo, M. A., et al. (2012). Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nat. Geosci. 5, 505–509. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1477

Fourqurean, J. W., and Schrlau, J. E. (2003). Changes in nutrient content and stable isotope ratios of C and N during decomposition of seagrasses and mangrove leaves along a nutrient availability gradient in Florida Bay, USA. Chem. Ecol. 19, 373–390. doi: 10.1080/02757540310001609370

Fry, B. (2013). Alternative approaches for solving undetermined isotope mixing problems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 472, 1–13. doi: 10.3354/meps10168

Fry, B., and Sherr, E. B. (1989). “δ13C measurements as indicators of carbon flow in marine and freshwater ecosystems,” in Stable Isotopes in Ecological Research, eds P. W. Rundel, J. R. Ehleringer, and K. A. Nagy (New York, NY: Springer).

Gachet, M. S., Schubert, A., Calarco, S., Boccard, J., and Gertsch, J. (2017). Targeted metabolomics shows plasticity in the evolution of signaling lipids and uncovers old and new endocannabinoids in the plant kingdom. Sci. Rep. 7:sre41177. doi: 10.1038/srep41177

Goldberg, C. S., Turner, C. R., Deiner, K., Klymus, K. E., Thomsen, P. F., Murphy, M. A., et al. (2016). Critical considerations for the application of environmental DNA methods to detect aquatic species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1299–1307. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12595

Greiner, J. T., Wilkinson, G. M., McGlathery, K. J., and Emery, K. A. (2016). Sources of sediment carbon sequestered in restored seagrass meadows. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 551, 95–105. doi: 10.3354/meps11722

Haddad, R. I., and Martens, C. S. (1987). Biogeochemical cycling in an organic-rich coastal marine basin: 9. Sources and accumulation rates of vascular plant-derived organic material. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 51, 2991–3001. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(87)90372-3

Hayes, M. A., Jesse, A., Hawke, B., Baldock, J., Tabet, B., Lockington, D., et al. (2017). Dynamics of sediment carbon stocks across intertidal wetland habitats of Moreton Bay, Australia. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4222–4234. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13722

He, D., Mead, R. N., Belicka, L., Pisani, O., and Jaffé, R. (2014). Assessing source contributions to particulate organic matter in a subtropical estuary: a biomarker approach. Org. Geochem. 75, 129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2014.06.012

Hondula, K. L., and Pace, M. L. (2014). Macroalgal support of cultured hard clams in a low nitrogen coastal lagoon. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 498, 187–201. doi: 10.3354/meps10644

Hondula, K. L., Pace, M. L., Cole, J. J., and Batt, R. D. (2014). Hydrogen isotope discrimination in aquatic primary producers: implications for aquatic food web studies. Aquat. Sci. 76, 217–229. doi: 10.1007/s00027-013-0331-6

Howard, J., Sutton-Grier, A., Herr, D., Kleypas, J., Landis, E., Mcleod, E., et al. (2017). Clarifying the role of coastal and marine systems in climate mitigation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 15:42–50. doi: 10.1002/fee.1451

Ish-Shalom-Gordon, N., Lin, G., and da Silveira Lobo Sternberg, L. (1992). Isotopic fractionation during cellulose synthesis in two mangrove species: salinity effects. Phytochemistry 31, 2623–2626. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83598-S

Jaffé, R., Mead, R., Hernandez, M. E., Peralba, M. C., and DiGuida, O. A. (2001). Origin and transport of sedimentary organic matter in two subtropical estuaries: a comparative, biomarker-based study. Org. Geochem. 32, 507–526. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00192-3

Johnson, B. J., Moore, K. A., Lehmann, C., Bohlen, C., and Brown, T. A. (2007). Middle to late Holocene fluctuations of C3 and C4 vegetation in a Northern New England Salt Marsh, Sprague Marsh, Phippsburg Maine. Org. Geochem. 38, 394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.06.006

Kelleway, J. J., Saintilan, N., Macreadie, P. I., Baldock, J. A., and Ralph, P. J. (2017). Sediment and carbon accumulation vary among vegetation assemblages in a coastal saltmarsh. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2017, 1–26. doi: 10.5194/bg-2017-15

Kennedy, H., Beggins, J., Duarte, C. M., Fourqurean, J. W., Holmer, M., Marbà, N., et al. (2010). Seagrass sediments as a global carbon sink: isotopic constraints. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 24:GB4026. doi: 10.1029/2010GB003848

Khare, N., and Chaturvedi, S. K. (2012). Tracing the signature of various frontal systems in stable isotopes (oxygen and carbon) of the planktonic foraminiferal species Globigerina bulloides in the Southern Ocean (Indian Sector). Oceanologia 54, 311–323. doi: 10.5697/oc.54-2.311

Krause-Jensen, D., and Duarte, C. M. (2016). Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nat. Geosci. 9, 737–742. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2790

Krause-Jensen, D., Lavery, P., Serrano, O., Marbà, N., Masque, P., and Duarte, C. M. (2018). Sequestration of macroalgal carbon: the elephant in the blue carbon room. Biol. Lett. 14:20180236. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0236

Ladd, S. N., and Sachs, J. P. (2015). Influence of salinity on hydrogen isotope fractionation in Rhizophora mangroves from Micronesia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 168, 206–221. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.07.004

Landenmark, H. K. E., Forgan, D. H., and Cockell, C. S. (2015). An estimate of the total dna in the biosphere. PLoS Biol. 13:e1002168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002168

Larsen, T., Bach, L. T., Salvatteci, R., Wang, Y. V., Andersen, N., Ventura, M., et al. (2015). Assessing the potential of amino acid 13C patterns as a carbon source tracer in marine sediments: effects of algal growth conditions and sedimentary diagenesis. Biogeosciences 12, 4979–4992. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-4979-2015

Larsen, T., Ventura, M., Andersen, N., O’Brien, D. M., Piatkowski, U., and McCarthy, M. D. (2013). Tracing carbon sources through aquatic and terrestrial food webs using amino acid stable isotope fingerprinting. PLoS One 8:e73441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073441

López-Merino, L., Serrano, O., Adame, M. F., Mateo, M. Á, and Martínez Cortizas, A. (2015). Glomalin accumulated in seagrass sediments reveals past alterations in soil quality due to land-use change. Glob. Planet. Change 133, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2015.08.004

Lovelock, C. E., Reef, R., and Ball, M. C. (2017). Isotopic signatures of stem water reveal differences in water sources accessed by mangrove tree species. Hydrobiologia 803, 133–145. doi: 10.1007/s10750-017-3149-8

Macreadie, P. I., Trevathan-Tackett, S. M., Baldock, J. A., and Kelleway, J. J. (2017). Converting beach-cast seagrass wrack into biochar: a climate-friendly solution to a coastal problem. Sci. Total Environ. 574, 90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.021

Marchand, C., Lallier-Vergès, E., and Baltzer, F. (2003). The composition of sedimentary organic matter in relation to the dynamic features of a mangrove-fringed coast in French Guiana. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 56, 119–130. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7714(02)00134-8

Marchand, C., Lallier-Vergès, E., Disnar, J.-R., and Kéravis, D. (2008). Organic carbon sources and transformations in mangrove sediments: a rock-eval pyrolysis approach. Org. Geochem. 39, 408–421. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2008.01.018

Mcleod, E., Chmura, G. L., Bouillon, S., Salm, R., Björk, M., Duarte, C. M., et al. (2011). A blueprint for blue carbon: toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9:552–560. doi: 10.1890/110004

Meier-Augenstein, W., Hobson, K. A., and Wassenaar, L. I. (2013). Critique: measuring hydrogen stable isotope abundance of proteins to infer origins of wildlife, food and people. Bioanalysis 5, 751–767. doi: 10.4155/bio.13.36

Moncreiff, C. A., and Sullivan, M. J. (2001). Trophic importance of epiphytic algae in subtropical seagrass beds: evidence from multiple stable isotope analyses. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 215, 93–106. doi: 10.3354/meps215093

Moore, J. W., and Semmens, B. X. (2008). Incorporating uncertainty and prior information into stable isotope mixing models. Ecol. Lett. 11, 470–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01163.x

Nellemann, C., Corcoran, E., Duarte, C. M., Valdés, L., De Young, C., Fonseca, L., et al. (2009). Blue carbon - the Role of Healthy Oceans in Binding Carbon. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11822/18520 (accessed June 4, 2017).

Oreska, M. P. J., Wilkinson, G. M., McGlathery, K. J., Bost, M., and McKee, B. A. (2018). Non-seagrass carbon contributions to seagrass sediment blue carbon. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, S3–S18. doi: 10.1002/lno.10718

Ortiz, J. E., Moreno, L., Torres, T., Vegas, J., Ruiz-Zapata, B., García-Cortés, Á, et al. (2013). A 220 ka palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the Fuentillejo maar lake record (Central Spain) using biomarker analysis. Org. Geochem. 55, 85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.11.012

Peterson, B. J., and Fry, B. (1987). Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 18, 293–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001453

Reef, R., Atwood, T. B., Samper-Villarreal, J., Adame, M. F., Sampayo, E. M., and Lovelock, C. E. (2017). Using eDNA to determine the source of organic carbon in seagrass meadows. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62, 1254–1265. doi: 10.1002/lno.10499

Rees, H. C., Maddison, B. C., Middleditch, D. J., Patmore, J. R. M., and Gough, K. C. (2014). Review: the detection of aquatic animal species using environmental DNA – a review of eDNA as a survey tool in ecology. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 1450–1459. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12306

Roden, J. S., Lin, G., and Ehleringer, J. R. (2000). A mechanistic model for interpretation of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios in tree-ring cellulose. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 64, 21–35. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00195-7

Rubenstein, D. R., and Hobson, K. A. (2004). From birds to butterflies: animal movement patterns and stable isotopes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.017

Ruppenthal, M., Oelmann, Y., and Wilcke, W. (2013). Optimized demineralization technique for the measurement of stable isotope ratios of nonexchangeable H in soil organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 949–957. doi: 10.1021/es303448g

Saintilan, N., Rogers, K., Mazumder, D., and Woodroffe, C. (2013). Allochthonous and autochthonous contributions to carbon accumulation and carbon store in southeastern Australian coastal wetlands. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 128, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2013.05.010

Santini, N. S., Reef, R., Lockington, D. A., and Lovelock, C. E. (2015). The use of fresh and saline water sources by the mangrove Avicennia marina. Hydrobiologia 745, 59–68. doi: 10.1007/s10750-014-2091-2

Sikes, E. L., Uhle, M. E., Nodder, S. D., and Howard, M. E. (2009). Sources of organic matter in a coastal marine environment: evidence from n-alkanes and their δ13C distributions in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Mar. Chem. 113, 149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2008.12.003

Silliman, J. E., Meyers, P. A., and Bourbonniere, R. A. (1996). Record of postglacial organic matter delivery and burial in sediments of Lake Ontario. Org. Geochem. 24, 463–472. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(96)00041-1

Sjögren, P., Edwards, M. E., Gielly, L., Langdon, C. T., Croudace, I. W., Merkel, M. K. F., et al. (2016). Lake sedimentary DNA accurately records 20th Century introductions of exotic conifers in Scotland. New Phytol. 213, 929–941. doi: 10.1111/nph.14199

Smale, D. A., Moore, P. J., Queirós, A. M., Higgs, N. D., and Burrows, M. T. (2018). Appreciating interconnectivity between habitats is key to blue carbon management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 16:71–73. doi: 10.1002/fee.1765

Smith, B. N., and Epstein, S. (1970). Biogeochemistry of the stable isotopes of hydrogen and carbon in salt marsh biota. Plant Physiol. 46, 738–742. doi: 10.1104/pp.46.5.738

Soto, D. X., Koehler, G., Wassenaar, L. I., and Hobson, K. A. (2017). Re-evaluation of the hydrogen stable isotopic composition of keratin calibration standards for wildlife and forensic science applications. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 31, 1193–1203. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7893

Stukel, M. R., Aluwihare, L. I., Barbeau, K. A., Chekalyuk, A. M., Goericke, R., Miller, A. J., et al. (2017). Mesoscale ocean fronts enhance carbon export due to gravitational sinking and subduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 1252–1257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609435114

Tanner, B. R., Uhle, M. E., Mora, C. I., Kelley, J. T., Schuneman, P. J., Lane, C. S., et al. (2010). Comparison of bulk and compound-specific δ13C analyses and determination of carbon sources to salt marsh sediments using n-alkane distributions (Maine, USA). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 86, 283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.11.023

Thomsen, P. F., Møller, P. R., Sigsgaard, E. E., Knudsen, S. W., Jørgensen, O. A., and Willerslev, E. (2016). Environmental dna from seawater samples correlate with trawl catches of subarctic, deepwater fishes. PLoS One 11:e0165252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165252

Thomsen, P. F., and Willerslev, E. (2015). Environmental DNA - An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 183, 4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019

Trevathan-Tackett, S. M., Macreadie, P. I., Sanderman, J., Baldock, J., Howes, J. M., and Ralph, P. J. (2017). A global assessment of the chemical recalcitrance of seagrass tissues: implications for long-term carbon sequestration. Front. Plant Sci. 8:925. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00925

Verheyden, A., Helle, G., Schleser, G. H., Dehairs, F., Beeckman, H., and Koedam, N. (2004). Annual cyclicity in high-resolution stable carbon and oxygen isotope ratios in the wood of the mangrove tree Rhizophora mucronata. Plant Cell Environ. 27, 1525–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01258.x

Volkman, J. K. (2006). Marine Organic Matter: Biomarkers, Isotopes and DNA. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Wang, Q., Lu, H., Chen, J., Hong, H., Liu, J., Li, J., et al. (2018). Spatial distribution of glomalin-related soil protein and its relationship with sediment carbon sequestration across a mangrove forest. Sci. Total Environ. 613–614, 548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.140

Wei, L., Lockington, D. A., Poh, S.-C., Gasparon, M., and Lovelock, C. E. (2013). Water use patterns of estuarine vegetation in a tidal creek system. Oecologia 172, 485–494. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2495-5

Wylie, L., Sutton-Grier, A. E., and Moore, A. (2016). Keys to successful blue carbon projects: lessons learned from global case studies. Mar. Policy 65, 76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.020

Yates, M. C., Fraser, D. J., and Derry, A. M. (2019). Meta-analysis supports further refinement of eDNA for monitoring aquatic species-specific abundance in nature. Environ. DNA. doi: 10.1002/edn3.7

Yoccoz, N. G., Bråthen, K. A., Gielly, L., Haile, J., Edwards, M. E., Goslar, T., et al. (2012). DNA from soil mirrors plant taxonomic and growth form diversity. Mol. Ecol. 21, 3647–3655. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05545.x

Zanden, V. B. H., Soto, D. X., Bowen, G. J., and Hobson, K. A. (2016). Expanding the isotopic toolbox: applications of hydrogen and oxygen stable isotope ratios to food web studies. Front. Ecol. Evol. 4:20. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00020

Zhang, Y., Du, J., Ding, X., and Zhang, F. (2016). Comparison study of sedimentary humic substances isolated from contrasting coastal marine environments by chemical and spectroscopic analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 75:378. doi: 10.1007/s12665-016-5263-8

Keywords: blue carbon, carbon accounting, environmental DNA, isotopes, organic carbon, sequestration

Citation: Geraldi NR, Ortega A, Serrano O, Macreadie PI, Lovelock CE, Krause-Jensen D, Kennedy H, Lavery PS, Pace ML, Kaal J and Duarte CM (2019) Fingerprinting Blue Carbon: Rationale and Tools to Determine the Source of Organic Carbon in Marine Depositional Environments. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:263. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00263

Received: 13 June 2018; Accepted: 02 May 2019;

Published: 22 May 2019.

Edited by:

Heliana Teixeira, University of Aveiro, PortugalReviewed by:

Teresa Alexandra Ribeiro Rodrigues, Portuguese Institute for the Ocean and Atmosphere (IPMA), PortugalBeverly Johnson, Bates College, United States

Copyright © 2019 Geraldi, Ortega, Serrano, Macreadie, Lovelock, Krause-Jensen, Kennedy, Lavery, Pace, Kaal and Duarte. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nathan R. Geraldi, bmF0aGFuLmdlcmFsZGlAa2F1c3QuZWR1LnNh

Nathan R. Geraldi

Nathan R. Geraldi Alejandra Ortega

Alejandra Ortega Oscar Serrano

Oscar Serrano Peter I. Macreadie

Peter I. Macreadie Catherine E. Lovelock

Catherine E. Lovelock Dorte Krause-Jensen

Dorte Krause-Jensen Hilary Kennedy

Hilary Kennedy Paul S. Lavery

Paul S. Lavery Michael L. Pace8

Michael L. Pace8 Carlos M. Duarte

Carlos M. Duarte