- 1Centre for Ecology and Evolution in Microbial Model Systems—EEMiS, Linnaeus University, Kalmar, Sweden

- 2Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute, Gothenburg, Sweden

Bacterioplankton communities regulate energy and matter fluxes fundamental to all aquatic life. The Baltic Sea offers an outstanding ecosystem for interpreting causes and consequences of bacterioplankton community composition shifts resulting from environmental disturbance. Yet, a systematic synthesis of the composition of Baltic Sea bacterioplankton and their responses to natural or human-induced environmental perturbations is lacking. We review current research on Baltic Sea bacterioplankton dynamics in situ (48 articles) and in laboratory experiments (38 articles) carried out at a variety of spatiotemporal scales. In situ studies indicate that the salinity gradient sets the boundaries for bacterioplankton composition, whereas, regional environmental conditions at a within-basin scale, including the level of hypoxia and phytoplankton succession stages, may significantly tune the composition of bacterial communities. Also the experiments show that Baltic Sea bacteria are highly responsive to environmental conditions, with general influences of e.g. salinity, temperature and nutrients. Importantly, nine out of ten experiments that measured both bacterial community composition and some metabolic activities showed empirical support for the sensitivity scenario of bacteria—i.e., that environmental disturbance caused concomitant change in both community composition and community functioning. The lack of studies empirically testing the resilience scenario, i.e., experimental studies that incorporate the long-term temporal dimension, precludes conclusions about the potential prevalence of resilience of Baltic Sea bacterioplankton. We also outline outstanding questions emphasizing promising applications in incorporating bacterioplankton community dynamics into biogeochemical and food-web models and the lack of knowledge for deep-sea assemblages, particularly bacterioplankton structure-function relationships. This review emphasizes that bacterioplankton communities rapidly respond to natural and predicted human-induced environmental disturbance by altering their composition and metabolic activity. Unless bacterioplankton are resilient, such changes could have severe consequences for the regulation of microbial ecosystem services.

Bacterioplankton Community and Functional Dynamics

Bacterioplankton communities have a remarkable capability in responding to environmental disturbances, such as changes in temperature, salinity and nutrients (Allison and Martiny, 2008; Logares et al., 2013; Cram et al., 2015; Salazar et al., 2016). Rapid responses are made possible thanks to relatively short generation times, and involve both adjustments in metabolic activity and restructuring of community composition (Box 1; Allison and Martiny, 2008; Brettar et al., 2016). There is now ample evidence that bacterioplankton activity and community composition play central roles in regulating biogeochemical cycles of elements, with particular focus on carbon in the form of dissolved organic matter (DOM) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC; Azam and Malfatti, 2007; Falkowski et al., 2008).

Box 1. Determining bacterioplankton community composition.

Marine bacteria and archaea, collectively known as bacterioplankton, are a fundamental part of the planktonic food-web and imperative for ecosystem functioning (Falkowski et al., 2008). Bacterioplankton community composition refers to the taxonomic identity of organisms and their frequency distribution in the ecosystem. However, phenotypic identification of bacterioplankton is problematic since only a small fraction of all bacterioplankton are easily cultivable and these typically do not mirror the complete bacterioplankton diversity (Pedros-Alio, 2006; Hagström et al., 2017). Microbial ecologists therefore use culture-independent genetic identification techniques to differentiate bacterioplankton taxa (see e.g., Hugerth et al., 2015; Sunagawa et al., 2015; Beier et al., 2017; Celepli et al., 2017). In general, identification of individual bacterioplankton taxa is done by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) or similar genetic fragments, processing raw sequence reads using bioinformatic methods (see e.g., Edgar, 2013; Callahan et al., 2015) and clustering these into specific phylotypes or operational taxonomic units (OTUs), followed by taxon delineation at a specific sequence identity threshold (typically 97–99% sequence identity; Hugerth and Andersson, 2017). Taxonomic annotation of these OTUs is then performed by matching a type- or centroid sequence of the OTU cluster against a database with taxonomic information (see e.g., Quast et al., 2013).

Technical advances in the last decade in the form of high-throughput sequencing have increased the sequencing resolution and thereby the detection levels of individual OTUs by several orders of magnitude at rapidly decreasing costs (Poisot et al., 2013; Hugerth and Andersson, 2017). As a result, the field of microbial ecology has advanced from primarily describing major bacterioplankton groups or a few dominant populations to resolving the distribution of thousands of populations over different temporal and spatial scales. This makes bacterioplankton attractive also for monitoring and thus important for stakeholders and marine management.

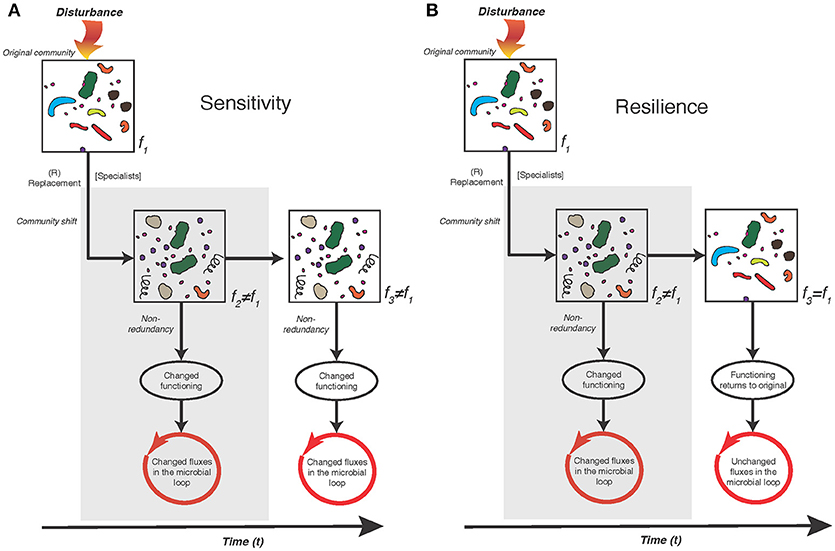

Given the importance of bacterioplankton-driven cycling of carbon, a fundamental question in microbial ecology is whether shifts in bacterioplankton community composition resulting from changes in environmental conditions also lead to changes in ecosystem functioning (Loreau, 2000, 2004; Langenheder et al., 2010; Comte and Del Giorgio, 2011; Beier et al., 2017). Bacterioplankton communities could, in theory, respond to environmental disturbances according to three scenarios termed sensitivity, resistance, and resilience [Box 2; sensu Allison and Martiny (2008); Shade et al. (2012)]. Each of these scenarios have distinctly different implications regarding how we interpret the consequences of environmental disturbances on the linkages between shifts in community composition and changes in community functioning. Ecosystem stability is linked with a community's response to disturbance. The stability depends on the sensitivity, resistance (insensitivity to disturbance), and the resilience (ability to return to original condition after disturbance) of the ecosystem (Shade et al., 2012). A disturbance is an event that can influence the community in pulses (discrete short-term events) or presses (long-term or continuous events). Shade et al. (2012) carried out a literature review to investigate bacterioplankton community responses to such disturbances in a variety of habitats. The authors identified that bacterioplankton communities are, in general, sensitive to disturbances but highlighted that empirical tests of resilience, i.e., studies that explicitly and comprehensively included the temporal dimension, were lacking.

Box 2. Bacterioplankton community responses to environmental disturbance

Below follows a brief description of three theoretical responses that bacterioplankton assemblages may undertake in the light of natural or human-induced changes in environmental conditions, sensu Allison and Martiny (2008), (Shade et al., 2012). The figure is laid so that it emphasizes the temporal dimension on the x-axis in the resilience scenario.

Sensitivity—when community composition is altered by environmental disturbance and the resulting community functioning (f2) is typically different from the initial functioning (f1).

Resistance—when community composition is not altered by environmental disturbance and community functioning (f2) may be different from, or the same as the initial f1.

Resilience—when community composition is initially altered by environmental disturbance but returns to the original composition and f2 is typically temporally different from the initial f1 but community functioning over time “returns to” f3 similar to the initial f1.

The Baltic Sea and Predicted Climate Change

The shallow brackish Baltic Sea system, with an average depth of ~54 m, varies in both hydrology and physicochemical features; it consists of a 2,000 km long salinity gradient ranging from truly marine to freshwater conditions through several basins of which three are major (the Baltic Sea Proper, the Bothnian Sea, and the Bothnian Bay; Omstedt et al., 2014). In addition to strong shifts in salinity, Baltic Sea basins are affected by different magnitudes of river discharges, transferring freshwater, and terrestrial DOM, so-called allochthonous DOM (i.e., DOM transported into the sea from terrestrial sources; Kritzberg et al., 2004), to coastal waters, with seasonal variation (Omstedt et al., 2014; Rowe et al., 2018). The Baltic Sea is periodically affected by seasonal phytoplankton blooms, including typical diatom/dinoflagellate spring blooms and massive blooms of cyanobacteria in summer (Legrand et al., 2015), producing so-called autochthonous DOM (i.e., DOM produced in situ by e.g., phytoplankton; Kritzberg et al., 2004).

Projections of human-induced climate change in aquatic environments, with global temperature increases of 1.4–5.8°C and a global atmospheric CO2 increase of 400 atm, resulting in lower pH by ~0.4 units until 2,100, implicate that ecosystem changes of unparalleled extent will occur (Brettar et al., 2016). In the Baltic Sea region the Swedish meteorological and hydrological institute (SMHI) projects increased precipitation by up to 48% until 2,100, leading to lower salinities and increased output of allochthonous matter from river discharge (Meier, 2006). Moreover, cyanobacterial blooms are increasing in magnitude due to human-driven climate change and the hydrography of this semi-enclosed system (Omstedt et al., 2014; Legrand et al., 2015). Eutrophication brings excess nutrients to the microbial food web, stimulating phytoplankton blooms that in turn influence the bacteria, resulting in increased community respiration rates through the degradation of phytoplankton DOM that sinks and ultimately causes bottom water and sediment hypoxia (Tamelander et al., 2017). Decreasing oxygen levels (< 2 mg ml−1 O2) at the seafloor and in sediments of the Baltic Sea have been documented in the last 100 years and decreases are predicted to intensify in the future (Carstensen et al., 2014). Taken together, future selective forces in the marine environment will include, among others, increased sea surface temperatures, lower pH, eutrophication, hypoxia, increased allochthonous carbon inputs, decreased salinity, and massive cyanobacterial blooms (Andersson et al., 2015). Thus, the Baltic Sea offers a unique study system to investigate, in depth, both the causes and consequences of shifts in bacterioplankton community composition and functioning responding to environmental perturbations.

Overview of Baltic Sea Bacterioplankton Studies

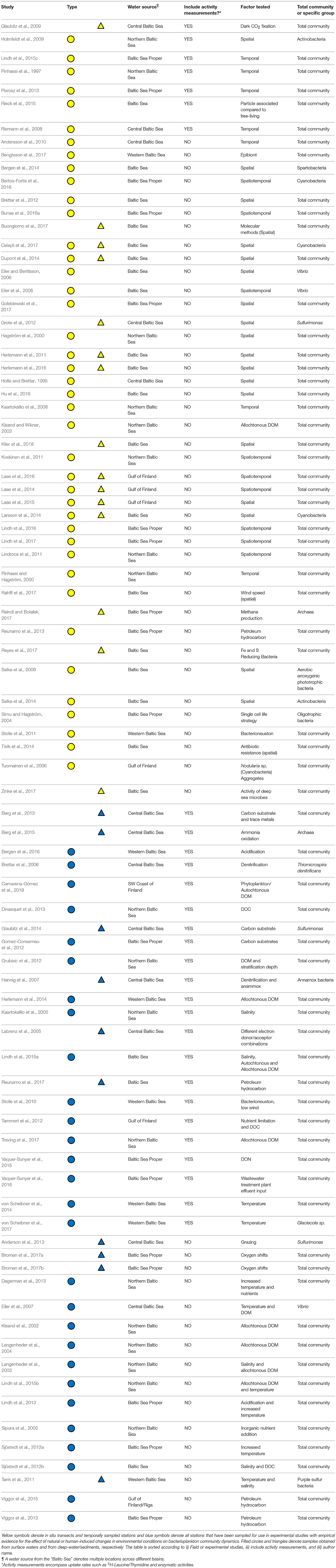

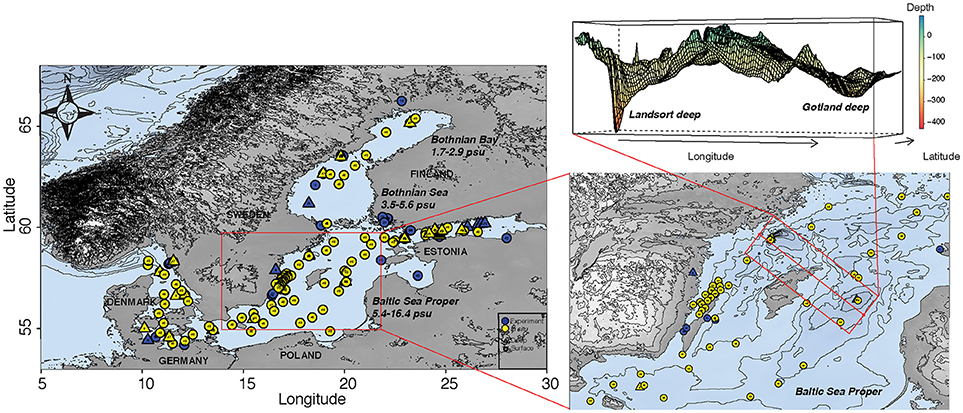

We identified a total of 86 articles carrying out field studies and/or experiments focusing on bacterioplankton community composition in the Baltic Sea, as summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. Studies performed in the Skagerrak and Kattegatt seas were examined (Supplementary Table 1), but were not included in the main analyses. Among the Baltic Sea studies, 48 were categorized as research performed in situ and 38 were experimental studies at different scales (micro- or mesocosms; Table 1). Twenty-six articles included samples from deep-waters/sediments. Among all articles, one third (n = 29) included some form of activity measurement and among the in situ studies less than one fifth (n = 9) measured metabolic activity. A majority of the articles focus on spatial distributions for in situ data (n = 27; 56% of all in situ studies) and on the effect of nutrient additions for experimental data (n = 22; 58% of all experimental studies; Table 1). The conducted studies have been performed throughout the Baltic Sea and include empirical evidence of shifts in bacterioplankton community composition in different basins (Figure 1). It is noteworthy that detailed temporal studies are typically limited to two sites in the Baltic Sea Proper (i.e., the Landsort Deep in the central Baltic Sea and at the Linnaeus Microbial Observatory off the coast of the island Öland in the Baltic Sea Proper) and that many deep-water/sediment samples have primarily been obtained from only two locations in the central Baltic Sea Proper (the Landsort and Gotland deeps in the central Baltic Sea; n = 10; 40% of all deep-water/sediment studies; Figure 1).

Table 1. Summary of Baltic Sea bacterioplankton studies in which data on community composition is available (n = 83).

Figure 1. Map showing in situ transects and temporally sampled stations (yellow symbols) and all stations that have been sampled for use in experimental studies with empirical evidence for the effect of natural or human-induced changes in environmental conditions on bacterioplankton community dynamics (blue symbols). Filled circles and triangles denote samples obtained from surface waters and from deep-water/sediment, respectively. Insert is a zoomed in map of the central Baltic Sea Proper with particularly many samples obtained, and a 3D rendition of the Gotland and Landsort Deep, frequently sampled to retrieve deep water and sediment samples. Dashed lines indicate boundaries for the three major basins; Bothnian Bay, Bothnian Sea and the Baltic Sea Proper. The map and bathymetry was produced using the package “marmap” (Pante and Simon-Bouhet, 2013) in R V.3.4.4 (R Core Development Team, 2017) and the bathymetry data was retrieved from NOAA (http://www.noaa.gov).

Temporal and Spatial Variability in Bacterioplankton

Extended temporal studies are scarce in the Baltic Sea, but there are four published reports of bacterioplankton dynamics extending over ≥1 year at semi- to high-resolution (Pinhassi and Hagström, 2000; Riemann et al., 2008; Andersson et al., 2010; Lindh et al., 2015c). They all show pronounced shifts in bacterioplankton community composition with fairly distinct spring, summer and autumn communities. In general, Bacteroidetes dominate in spring during the diatom and dinoflagellate bloom. In summer, particular populations of e.g., Verrucomicrobia increase in abundance, associated with pronounced blooms of picocyanobacterial populations and filamentous Cyanobacteria. In autumn, actinobacterial populations proliferate, potentially following changes in temperature, mixing of the water column, and/or autumn phytoplankton blooms. Changes in temperature over the yearly cycle typically explain around 0.45 (Pearson r) of total variation in community composition (Andersson et al., 2010; Lindh et al., 2015c).

There have been three major transects studies of bacterioplankton community composition across the entire salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea, showing that changes in salinity is the major driver of the distribution of bacterial populations (OTUs) at large spatial scales in the Baltic Sea (Herlemann et al., 2011, 2016; Dupont et al., 2014; Larsson et al., 2014; Celepli et al., 2017). Notably, salinity explained almost all of the observed variation in bacterioplankton community composition with r values ranging from 0.78 to 0.97. In contrast, in a transect across one particular basin, the Baltic Sea Proper, Bunse et al. (2016a) found that, instead of salinity, the advancing phytoplankton spring bloom had a substantial influence in structuring the bacterial community (i.e., the distribution of specific OTUs). The authors emphasized how interactions between bacterioplankton and phytoplankton populations may influence carbon cycling to higher trophic levels thus extending the importance of bacterioplankton dynamics for ecosystem services. In addition, there have been several transects performed at high-resolution spatial scales of which two locations are particularly well-studied; the western Gotland Sea (Bertos-Fortis et al., 2016; Lindh et al., 2016, 2017) and the Gulf of Finland (Laas et al., 2014, 2015, 2016). For example, Bertos-Fortis et al. (2016) show that Cyanobacteria have plastic responses to changes in environmental conditions where opportunistic picocyanobacteria and N2-fixing cyanobacteria may be able to utilize nutrients from filamentous Cyanobacteria during the summer bloom (Bertos-Fortis et al., 2016). An approach using metacommunity theory (Leibold et al., 2004) found that local environmental conditions rather than dispersal-driven assembly is the main mechanism for structuring bacterioplankton assemblages in the Baltic Sea (Lindh et al., 2016). Similarly, bacterioplankton communities in areas such as the Pacific Ocean and East China Sea are also mainly shaped by environmental factors and to a less extent by spatial factors (Yeh et al., 2015; Lindh et al., 2018). Moreover, deep-water bacterioplankton communities in the Gulf of Finland are structured by seasonally anoxic conditions where redox-specialized bacterioplankton populations proliferate (Laas et al., 2015). Surface seawater communities in that study, on the other hand, were largely assembled following variation in phytoplankton succession. Collectively, these studies indicate that whereas the salinity gradient sets the boundaries for bacterioplankton composition, regional environmental conditions at a within-basin scale, including the level of hypoxia and phytoplankton succession stages, may significantly tune the composition of bacterioplankton.

Experimental Manipulation of Environmental Conditions

Salinity

The in situ studies described above dictate that grand scale spatial distributions of particular OTUs in the Baltic Sea are driven by changes in salinity. In accordance, manipulated changes in salinity in micro- and mesocosm experiments also show that salinity can significantly shape bacterioplankton community composition (Langenheder et al., 2003; Kaartokallio et al., 2005; Sjöstedt et al., 2012b; Lindh et al., 2015a). For example, shifts in bacterioplankton community structure occurred in response to salinity changes following the experimental melting of sea ice (Kaartokallio et al., 2005). Compositional shifts occurred in response to a change in salinity and DOM conditions using chemostats, showing how rare or inactive taxa already present in the “seed bank,” proliferated over time (Sjöstedt et al., 2012b). Moreover, a transplant experiment showed how transfer of bacterioplankton assemblages from ambient to changed salinity (brackish compared to near freshwater) and DOM conditions (allochthonous compared to autochthonous) has a major impact on composition and metabolic activity (Lindh et al., 2015a). Still, how such changes in salinity affect bacterioplankton community functioning, with potential implications for ecosystem services, remains largely unknown.

Temperature and pH

Seasonal variation in temperature significantly affects bacterioplankton community dynamics in the Baltic Sea (Andersson et al., 2010; Lindh et al., 2015c). Empirical evidence from micro- and mesocosm experiments highlights temperature as a major driver of compositional shifts in bacterioplankton (Muren et al., 2005; Sommer et al., 2007; Hoppe et al., 2008; von Scheibner et al., 2014; Vaquer-Sunyer et al., 2015). Typically, OTUs affiliated with Gammaproteobacteria such as Glaciecola spp. proliferate at higher temperatures (von Scheibner et al., 2017). Gammaproteobacteria also increased in relative abundance in warming experiments of bacterioplankton amended with dissolved organic nitrogen sources and incubated in higher temperatures (Vaquer-Sunyer et al., 2015). Here it is also worthwhile to mention that cell size is influenced by increasing temperatures (Sjöstedt et al., 2012a), as also observed in other marine ecosystems (Morán et al., 2015).

Evidence for the effect of ocean acidification on Baltic Sea bacterioplankton community dynamics are few (Bergen et al., 2016). Still, there are some indications of synergistic effects between increased temperature and pCO2 levels (Lindh et al., 2013). This is in line with analyses from other systems suggesting that ocean acidification could affect bacterioplankton growth and physiology both directly and indirectly, e.g., by affecting DOM release and composition originating from higher trophic levels (Vega Thurber et al., 2009; Joint et al., 2011; Bunse et al., 2016b; Sala et al., 2016). Therefore, increased sea surface temperatures together with acidification due to climate change will likely affect the dynamics of particular bacterioplankton populations either alone or synergistically with potential amplification effects.

Nutrient Inputs

The quality and composition of DOM is partly dependent on its origin, which can be either allochthonous or autochthonous (Kritzberg et al., 2004; Nagata, 2008). Since bacteria are the main contributors to the biological transformation of marine DOM, much attention has been put into uncovering the role of bacterial community composition in this biogeochemical process. In the Baltic Sea, particular opportunistic bacterioplankton populations are capable of successfully utilizing elevated concentrations of labile, low-molecular weight (LMW) compounds (Gomez-Consarnau et al., 2012). Moreover, multiple studies report important effects of allochthonous DOM on Baltic Sea bacterioplankton responses in community composition (Kisand et al., 2002; Grubisic et al., 2012; Herlemann et al., 2014). An important and intriguing future challenge is to determine the relationship between DOM composition and bacterioplankton community composition and functioning. Curiously, we found few studies reporting on the direct effects of inorganic nutrient enrichments on Baltic Sea Bacterioplankton communities (but see Tammert et al., 2012). This is perhaps surprising given the importance nitrogen and phosphorus plays in eutrophication of the Baltic Sea (Conley et al., 2009). Simple experiments with bacterioplankton assemblages and nitrogen and phosphorus additions will be a promising avenue of future research to couple changes in inorganic nutrients and DOM to shifts in bacterioplankton community structure and its relationship with Baltic Sea ecosystem function.

Opportunistic Gammaproteobacteria—Bottle Effects or True Dynamics?

OTUs affiliated with Gammaproteobacteria often increase in relative abundance in micro- and mesocosm experiments. Such dynamics are sometimes attributed to the so-called “bottle effect” in which confinement of water causes shifts in bacterioplankton community composition and physiological rates (Fuchs et al., 2000; Massana et al., 2001; Baltar et al., 2012). Such effects are typically detected by rapidly increasing proportions of copiotrophic gammaproteobacterial populations and metabolic activity (see e.g., Gomez-Consarnau et al., 2012; Sjöstedt et al., 2012b). However, we note that particular gammaproteobacterial OTUs also peak in relative abundance in situ (Andersson et al., 2010; Lindh et al., 2015c). This pattern does not only occur in the Baltic Sea but also in the North Sea and Mediterranean Sea (Fodelianakis et al., 2014; Alonso-Saez et al., 2015; Teeling et al., 2016). These findings suggest that Gammaproteobacteria could respond faster to environmental disturbances aided by their copiotrophic lifestyle and thus potentially become dominant more frequently due to increased incidence of perturbation in situ. It remains to be determined whether such changes would significantly alter microbial-driven carbon cycling or if these Gammaproteobacteria perhaps carry functional redundancy (see e.g., Pedler et al., 2014).

Bacterioplankton Community Functioning is Correlated with Community Dynamics but Data is Scarce

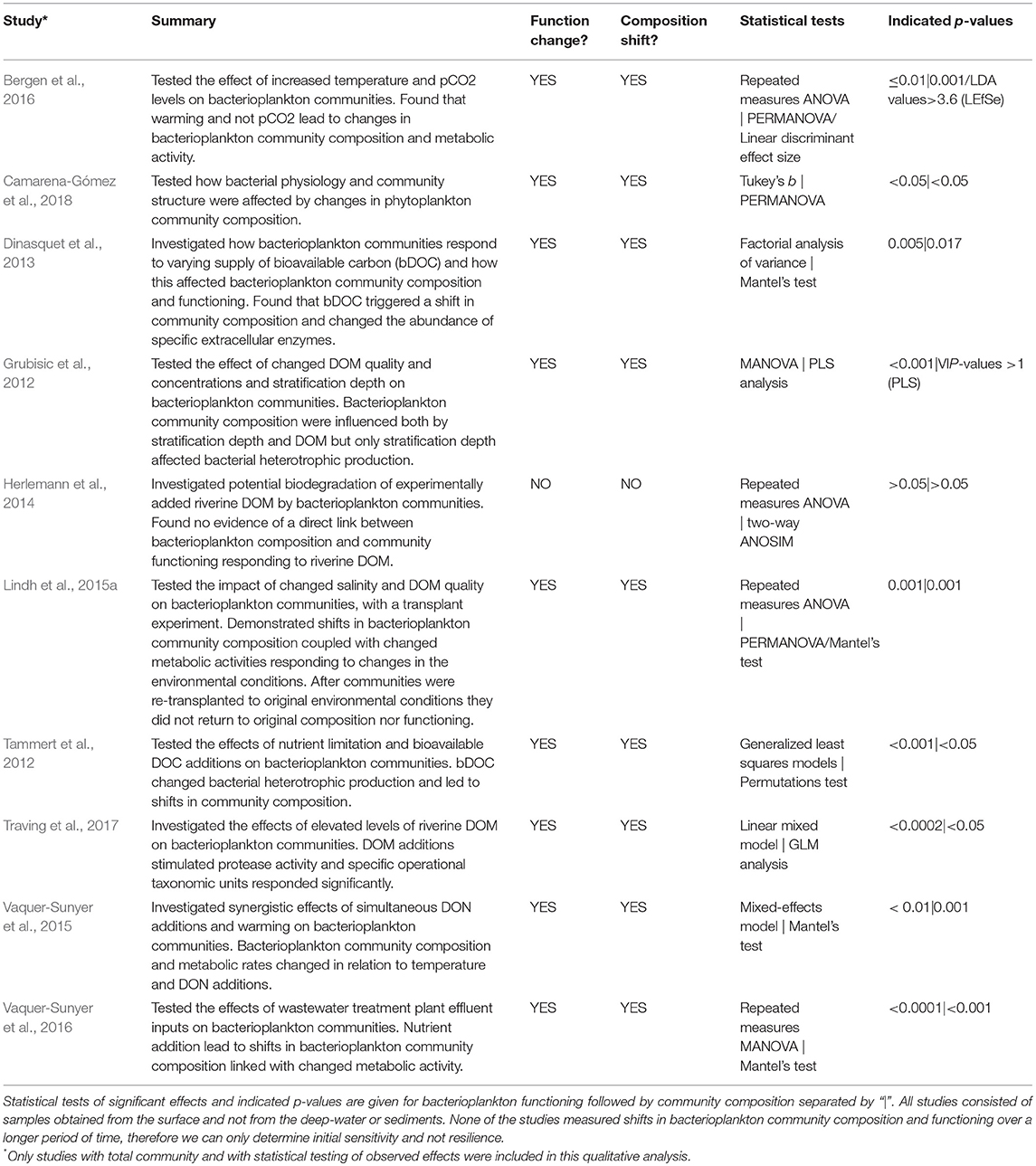

In this section we provide an overview of experimental studies that statistically tested the linkage between changes in bacterioplankton community composition and metabolic activity (i.e., functioning) upon environmental forcing (disturbance; Table 2). A few in situ studies have shown simultaneous shifts in bacterioplankton community composition and metabolic activity (Pinhassi et al., 1997; Riemann et al., 2008; Glaubitz et al., 2009; Holmfeldt et al., 2009; Piwosz et al., 2013; Lindh et al., 2015c; Rieck et al., 2015; Table 1), but as these measurements can be influenced by and/or auto-correlated to a number of undetermined environmental variables they were not included in the current analysis. A majority of experimental studies performed (non-quantitative) cluster-like analyses based on beta-diversity estimates that indicated shifts in composition (see e.g., Lindh et al., 2013; von Scheibner et al., 2014). Notably, most of the studies using cluster statistics methods show that functioning to some degree changes upon shift in composition. A number of studies focused on changes in the relative or absolute abundance of particular taxa or groups of bacterioplankton such as Sulfurimonas GD-1, Thiomicrospira denitrificans, and Glaciecola spp. and also measured metabolic activity of these populations (Brettar et al., 2006; Glaubitz et al., 2014; von Scheibner et al., 2017). Importantly, shifts in abundance of these particular populations were typically coupled to pronounced changes in metabolic activity when exposed to environmental disturbance.

Table 2. Summary of Baltic Sea bacterioplankton studies in which experimental data with empirical testing of the effect of natural or anthropogenically induced disturbances on total bacterioplankton community composition and functioning have been determined concomitantly (n = 10).

Relatively few studies have carried out statistical assessments with quantitative data for changes in both the overall bacterioplankton community composition and bacterial functioning (e.g., using multivariate statistics such as Mantel's test, PERMANOVA, or similar). We analyze in detail these studies to reach a general understanding of current quantitative data. We note a lack of deep-water or sediments studies that in a strict sense target such quantitative assessments. Consequently, only studies with surface water samples were included in this analysis (Table 2). Nine out of ten studies with measurements of total bacterioplankton community composition and metabolic activity show empirical evidence of concomitant shifts in community composition and functioning. One study, by Herlemann et al. (2014), found no significant effects on bacterioplankton community dynamics responding to riverine DOM additions, including limited growth, nor links between composition and functioning. Thus, a majority of studies highlight bacterioplankton assemblages responding to disturbances following the sensitivity scenario (Table 2; Box 2).

The studies showing statistical support for concomitant shifts in community composition and functioning essentially investigated the effect of nutrient amendments on bacterioplankton community composition dynamics and metabolic activity (Grubisic et al., 2012; Tammert et al., 2012; Degerman et al., 2013; Lindh et al., 2015a; Vaquer-Sunyer et al., 2015, 2016; Bergen et al., 2016; Traving et al., 2017; Camarena-Gómez et al., 2018). The Bergen et al. (2016) study emphasized how temperature significantly alters community composition and heterotrophic bacterial production but that pCO2 had a more limited effect. The authors noted how these changes in bacterioplankton dynamics could be indicative of changed carbon fluxes in a future ecosystem where heterotrophy may become more important compared to today. Dinasquet et al. (2013) showed that bioavailable DOC triggered a shift in community composition and changed the abundance of specific extracellular enzymes suggesting that bacterioplankton communities can respond, following the sensitivity scenario, to varying supplies of DOC ultimately affecting heterotrophic respiration. Vaquer-Sunyer et al. (2015) also noted that nutrient inputs of dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) and changed temperature may lead to a more heterotrophic system. In a different study by Vaquer-Sunyer et al. (2016), they showed an effect of wastewater treatment plant effluent inputs on bacterioplankton dynamics, with an increase in the relative abundance of Cyanobacteria responding to the influx of wastewater with concomitant changes in metabolic activity. A recent study by Camarena-Gómez et al. (2018) investigated the relationship between phytoplankton bloom dynamics (different phytoplankton species) and bacterioplankton community function and taxonomic structure. Their work emphasized how bacterial metabolic activity and community composition were affected by changes in the phytoplankton community—in particular the divergent bacterial responses to phytoplankton dominated by diatoms compared to dinoflagellates. Amendment of a diatom dominated community resulted in a significantly changed bacterial heterotrophic production and shift in bacterioplankton community structure compared controls, while amendment of a dinoflagellate community had overall smaller impact on both community function and composition Camarena-Gómez et al., 2018). It is noteworthy how the addition of riverine DOM could result in changed ecosystem function from shifts in bacterioplankton community dynamics toward a more heterotrophic system (Degerman et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2016). Also in the Gulf of Finland enrichment with labile DOC changed bacterial production and led to shifts in community composition, promoting filamentous bacteria - the authors indicate that this DOC source may impact diversity, food-web structure and biogeochemical processing of carbon (Tammert et al., 2012). Only three specific studies have directly determined the correlation between shifts in community composition and metabolic activity responding to environmental perturbations (Lindh et al., 2015a; Vaquer-Sunyer et al., 2015, 2016). These studies indicated that variation in bacterioplankton community functioning is often significantly explained by changes in metabolic activity explaining up to around 0.65 of the variance (Pearson r).

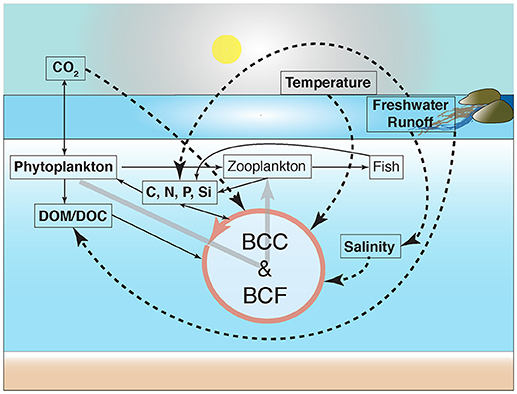

Although environmental disturbances can influence bulk bacterioplankton community composition, the replacement of sensitive taxa will occur at the individual OTU level. For example, although Bergen et al. (2016) implicated limited effects on bulk community dynamics resulting from increased pCO2, there was a substantial influence on particular populations with statistical support from linear discriminant effect size (LEfSe). Traving et al. (2017) performed statistical tests (generalized linear models) to determine the coupling between specific OTUs and amendment of riverine DOM where several OTUs were significantly correlated with changed environmental conditions. Although these shifts in the relative abundance of particular OTUs were not coupled directly to metabolic activity there were concomitant significant changes in protease activity. Taken together, the nine studies emphasize the sensitivity scenario of bacterioplankton communities in Baltic Sea, where particular populations respond to different sets of environmental forcing. The causal loop diagram in Figure 2 summarizes the significant effects of changes in environmental conditions for community composition and functioning included in this review. Overall, the studies in this section highlight how changes in environmental forcing may significantly impact pelagic remineralization of organic carbon and result in a drastic reduction in the flow of organic matter through the microbial loop.

Figure 2. Causal-loop diagram indicating potential ecosystem-wide effects in carbon cycling due to responses among bacterioplankton populations to natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Bacterioplankton community composition and functioning have been abbreviated to BCC and BCF, respectively. The figure is redrawn and modified from (Azam and Malfatti, 2007). Continuous and dashed arrows denote nutrient fluxes and changes in environmental variables with empirical evidence of significant effects on bacterioplankton community composition covered in this review, respectively. Changes in bacterioplankton community functioning, such as bacterial heterotrophic production and respiration, may occur due to increases in the availability of dissolved organic matter (DOM), resulting from, for example, increased freshwater runoff and phytoplankton blooms.

Outstanding Questions

Although the Baltic Sea bacterial communities are fairly well studied, research to integrate bacterioplankton dynamics and its consequences in food-web and biogeochemical models is much needed. We infer that such integration is necessary to allow predictions and counter measures of detrimental future climate change effects on microbial food webs and their ecosystem services.

Recent work on bacterial populations and their activity at the seafloor of the Baltic Sea has shown a plethora of interesting dynamics and lifestyles including, an active community that was previously deemed unlikely (Glaubitz et al., 2009, 2014; Berg et al., 2013, 2015; Broman et al., 2017a,b; Reyes et al., 2017; Zinke et al., 2017). Detailed studies with concomitant measurements of bacterioplankton community composition and function are required in deep-waters and sediments of the Baltic Sea to determine the role of bacteria in key biogeochemical cycles (e.g., of C, N, P, and S) in general, and in relation to hypoxia in particular.

Seasonal in situ studies of bacterioplankton community dynamics have emphasized how communities return to a similar composition and functioning in specific seasons year after year (Fuhrman et al., 2006; Andersson et al., 2010; Lindh et al., 2015c). This could indicate that bacterioplankton communities are in fact resilient to recurrent pulse and press disturbances, but could also indicate that the environmental conditions over seasons are “repeated” and that the same bacterial populations are repeatedly selected for. Overall, there is a recognized need to incorporate the long-term temporal dimension when quantifying resistance and resilience of microbial communities (Shade et al., 2012; Fodelianakis et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018). Only by including the temporal dimension can microbial ecologists fully understand the consequences of ocean change for bacterioplankton community dynamics, and we urgently need more information on changes occurring over time, preferably long-term studies. In particular, for experimental studies, there is a lack of data that empirically test the scenarios of resistance and resilience for Baltic Sea bacterioplankton communities. Nevertheless, in one study using a transplant and re-transplant experimental design (Lindh et al., 2015a), we showed how bacterioplankton community dynamics remain altered even after returning to the same environmental conditions as the original community experienced. One of the most important questions to address in future studies in the Baltic Sea will therefore be to empirically test whether bacterioplankton communities remain sensitive to an environmental disturbance or if the community can return to a similar original community structure and function following the resilience scenario. Presently, we observe that a majority of the Baltic Sea studies point toward the sensitivity scenario, and that it is necessary to await future research to make definite conclusions regarding the extent of resilience. Thus, within the time frame of 2 weeks, the studies indicate that sensitivity is more developed than resistance. Nevertheless, natural temporal changes in environmental conditions for time frames of more than a month will alter the composition and functioning of bacterioplankton communities, likely interfering with interpretations of the scenarios of sensitivity, resistance and resilience.

Summary

A majority of the studies included in this review show that bacterioplankton community composition is sensitive to changes in environmental conditions, in particular salinity and nutrient inputs, with empirical support for simultaneous changes also in community functioning. As noted also in other aquatic environments, pronounced shifts in composition and bacterial heterotrophic production occur following spring diatom and dinoflagellate blooms and summer blooms of filamentous Cyanobacteria. The sensitivity scenario and its impact on the microbial loop is highlighted in Figure 3A. Salinity singles out as a principal determinant of the distribution of bacterioplankton populations across basin-wide spatial scales in the Baltic Sea. Nevertheless, at regional (within-basin) scales, changes in nutrient availability and both autochthonous and allochthonous DOM influence the bacterioplankton community composition. Hence, this review provides a roadmap as to what ecological consequences climate change could have on the Baltic Sea ecosystem if bacterioplankton dynamics changes. Yet, although bacterioplankton communities are initially sensitive we know very little about the potential of resilience due to the lack of empirical studies testing this scenario (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Conceptual diagram of two possible scenarios of Baltic Sea bacterioplankton community dynamics, i.e., sensitivity (A), and resilience (B). In both the sensitivity and resilience scenario an environmental disturbance leads to the replacement of individual bacterioplankton populations and changed community functioning with potential impact on the microbial loop and carbon cycling. The scenarios differ in that over time the replacement of individual bacterioplankton populations and changed community functioning remains in (A), but returns to similar individual bacterioplankton populations and community functioning as the original community in (B). Scenarios with empirical evidence of significant effects on bacterioplankton community composition and functioning in the present review is the impact of dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) additions and increased temperatures Bergen et al. (2016), Vaquer-Sunyer et al. (2015). However, for Baltic Sea data, the lack of long-term studies precludes conclusions regarding whether the sensitivity or resilience scenario are the most prominent—currently studies have been designed primarily to determine the extent of the initial sensitivity (gray filled areas).

For quantifying the level of sensitivity or resilience of bacterioplankton communities to natural and human-driven changes in environmental conditions it is essential to investigate particular bacterioplankton populations and their responses to alternate physicochemical conditions and specific (in)organic nutrient sources, e.g., different DOM and DOC compounds. The sensitivity scenario has important implications for the Baltic Sea ecosystem: it dictates that environmental disturbances and climate change are likely to affect processes like the microbial-driven carbon pump and/or the general microbial regulation of energy and matter fluxes. We infer that knowledge of the linkages between bacterioplankton composition and bacterial cycling of carbon and other elements under varying environmental forcing is critically important for developing action plans to sustain microbial ecosystem services invaluable for all marine life.

Author Contributions

ML and JP both participated in the study design, analysis, and writing of the article.

Funding

The research was supported by the Swedish Research Council FORMAS strong research programme EcoChange, the Linnaeus University Center for Ecology and Evolution in Microbial model Systems (EEMiS), and by grants from the Swedish Research Council VR. This work resulted from the BONUS BLUEPRINT project which was supported by BONUS (Art 185), funded jointly by the EU and FORMAS.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article was partly inspired by work done in the Ph.D. thesis by Lindh (2014), in particular the section on synthesis on bacterioplankton communities responding to natural and anthropogenically induced environmental disturbances. We also thank Carina Bunse, Mireia Bertos-Fortis, Hanna Farnelid, Catherine Legrand, Christofer Karlsson, Saraladevi Muthusamy, Federico Baltar, and Sandra Martinez-García for enthusing discussions that inspired writing this article.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2018.00361/full#supplementary-material

References

Allison, S. D., and Martiny, J. B. (2008). Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105(Suppl. 1), 11512–11519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801925105

Alonso-Saez, L., Diaz-Perez, L., and Moran, X. A. (2015). The hidden seasonality of the rare biosphere in coastal marine bacterioplankton. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 3766–3780. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12801

Anderson, R., Wylezich, C., Glaubitz, S., Labrenz, M., and Juergens, K. (2013). Impact of protist grazing on a key bacterial group for biogeochemical cycling in Baltic Sea pelagic oxic/anoxic interfaces. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 1580–1594. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12078

Andersson, A., Meier, H. E. M., Ripszam, M., Rowe, O., Wikner, J., Haglund, P., et al. (2015). Projected future climate change and Baltic Sea ecosystem management. AMBIO 44, 345–356. doi: 10.1007/s13280-015-0654-8

Andersson, A. F., Riemann, L., and Bertilsson, S. (2010). Pyrosequencing reveals contrasting seasonal dynamics of taxa within Baltic Sea bacterioplankton communities. ISME J. 4, 171–181. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.108

Azam, F., and Malfatti, F. (2007). Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 782–791. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1747

Baltar, F., Lindh, M. V., Parparov, A., Berman, T., and Pinhassi, J. (2012). Prokaryotic community structure and respiration during long-term incubations. Microbiol Open 1, 214–224. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.25

Beier, S., Shen, D., Schott, T., and Jürgens, K. (2017). Metatranscriptomic data reveal the effect of different community properties on multifunctional redundancy. Mol Ecol. 26, 6813–6826. doi: 10.1111/mec.14409

Bengtsson, M. M., Bühler, A., Brauer, A., Dahlke, S., Schubert, H., and Blindow, I. (2017). Eelgrass leaf surface microbiomes are locally variable and highly correlated with epibiotic eukaryotes. Front. Microbiol. 8:1312. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01312

Berg, C., Beckmann, S., Jost, G., Labrenz, M., and Juergens, K. (2013). Acetate-utilizing bacteria at an oxic-anoxic interface in the Baltic Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85, 251–261. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12114

Berg, C., Listmann, L., Vandieken, V., Vogts, A., and Juergens, K. (2015). Chemoautotrophic growth of ammonia-oxidizing Thaumarchaeota enriched from a pelagic redox gradient in the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol. 5:786. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00786

Bergen, B., Endres, S., Engel, A., Zark, M., Dittmar, T., Sommer, U., et al. (2016). Acidification and warming affect prominent bacteria in two seasonal phytoplankton bloom mesocosms. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 4579–4595. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13549

Bergen, B., Herlemann, D. P. R., Labrenz, M., and Jürgens, K. (2014). Distribution of the verrucomicrobial clade Spartobacteria along a salinity gradient in the Baltic Sea. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 6:625–630. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12178

Bertos-Fortis, M., Farnelid, H. M., Lindh, M. V., Casini, M., Andersson, A., Pinhassi, J., et al. (2016). Unscrambling cyanobacteria community dynamics related to environmental factors. Front. Microbiol. 7:625. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00625

Brettar, I., Christen, R., and Hofle, M. G. (2012). Analysis of bacterial core communities in the central Baltic by comparative RNA-DNA-based fingerprinting provides links to structure-function relationships. ISME J. 6, 195–212. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.80

Brettar, I., Hoefle, M. G., Pruzzo, C., and Vezzulli, L. (2016). “Climate change effects on planktonic bacterial communities in the ocean - from structure and function to long-term and large-scale observations,” in Climate Change and Microbial Ecology: Current Research And Future Trends, ed Jürgen Marxsen. (Giessen: Caister Academic Press), 23–40.

Brettar, I., Labrenz, M., Flavier, S., Botel, J., Kuosa, H., Christen, R., et al. (2006). Identification of a thiomicrospira denitrificans-like epsilonproteobacterium as a catalyst for autotrophic denitrification in the central Baltic Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1364–1372. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1364-1372.2006

Broman, E., Sachpazidou, V., Pinhassi, J., and Dopson, M. (2017a). Oxygenation of hypoxic coastal baltic sea sediments impacts on chemistry, microbial community composition, and metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 8:2453. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02453

Broman, E., Sjöstedt, J., Pinhassi, J., and Dopson, M. (2017b). Shifts in coastal sediment oxygenation cause pronounced changes in microbial community composition and associated metabolism. Microbiome 5:96. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0311-5

Bunse, C., Bertos-Fortis, M., Sassenhagen, I., Sildever, S., Sjoqvist, C., Godhe, A., et al. (2016a). Spatio-temporal interdependence of bacteria and phytoplankton during a baltic sea spring bloom. Front. Microbiol. 7:517. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00517

Bunse, C., Lundin, D., Karlsson, C. M. G., Akram, N., Vila-Costa, M., Palovaara, J., et al. (2016b). Response of marine bacterioplankton pH homeostasis gene expression to elevated CO2. Nat. Clim. Change. 6, 483–487. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2914

Buongiorno, J., Turner, S., Webster, G., Asai, M., Shumaker, A. K., Roy, T., et al. (2017). Interlaboratory quantification of bacteria and archaea in deeply buried sediments of the Baltic Sea (IODP Expedition 347). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93:fix007. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix007

Callahan, B. J., Mcmurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J., and Holmes, S. P. (2015). DADA2: high resolution sample inference from amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

Camarena-Gómez, M. T., Lipsewers, T., Piiparinen, J., Eronen-Rasimus, E., Perez-Quemaliños, D., Hoikkala, L., et al. (2018). Shifts in phytoplankton community structure modify bacterial production, abundance and community composition. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 81, 149–170. doi: 10.3354/ame01868

Carstensen, J., Andersen, J. H., Gustafsson, B. G., and Conley, D. J. (2014). Deoxygenation of the Baltic Sea during the last century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 5628–5633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323156111

Celepli, N., Sundh, J., Ekman, M., Dupont, C. L., Yooseph, S., Bergman, B., et al. (2017). Meta-omic analyses of Baltic Sea cyanobacteria: diversity, community structure and salt acclimation. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 673–686. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13592

Comte, J., and Del Giorgio, P. A. (2011). Composition influences the pathway but not the outcome of the metabolic response of bacterioplankton to resource shifts. PLoS ONE 6:e25266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025266

Conley, D. J., Paerl, H. W., Howarth, R. W., Boesch, D. F., Seitzinger, S. P., Havens, K. E., et al. (2009). Controlling eutrophication: nitrogen and phosphorus. Science 323, 1014–1015. doi: 10.1126/science.1167755

Cram, J. A., Xia, L. C., Needham, D. M., Sachdeva, R., Sun, F., and Fuhrman, J. A. (2015). Cross-depth analysis of marine bacterial networks suggests downward propagation of temporal changes. ISME J. 9, 2573–2586. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.76

Degerman, R., Dinasquet, J., Riemann, L., De Luna, S. S., and Andersson, A. (2013). Effect of resource availability on bacterial community responses to increased temperature. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 68, 131–142. doi: 10.3354/ame01609

Dinasquet, J., Kragh, T., Schroter, M.-L., Sondergaard, M., and Riemann, L. (2013). Functional and compositional succession of bacterioplankton in response to a gradient in bioavailable dissolved organic carbon. Environ Microbiol. 15, 2616–2628. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12178

Dupont, C. L., Larsson, J., Yooseph, S., Ininbergs, K., Goll, J., Asplund-Samuelsson, J., et al. (2014). Functional tradeoffs underpin salinity-driven divergence in microbial community composition. PLoS ONE 9:e89549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089549

Edgar, R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

Eiler, A., and Bertilsson, S. (2006). Detection and quantification of Vibrio populations using denaturant gradient gel electrophoresis. J. Microbiol. Methods 67, 339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.04.002

Eiler, A., Gonzalez-Rey, C., Allen, S., and Bertilsson, S. (2007). Growth response of Vibrio cholerae and other Vibrio spp. to cyanobacterial dissolved organic matter and temperature in brackish water. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 60, 411–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00303.x

Eiler, A., Johansson, M., and Bertilsson, S. (2006). Environmental influences on Vibrio populations in northern temperate and boreal coastal waters (Baltic and Skagerrak Seas). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 6004–6011. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00917-06

Falkowski, P. G., Fenchel, T., and Delong, E. F. (2008). The microbial engines that drive earth's biogeochemical cycles. Science 320, 1034–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1153213

Figueroa, D., Rowe, O. F., Paczkowska, J., Legrand, C., and Andersson, A. (2016). Allochthonous carbon—a major driver of bacterioplankton production in the subarctic northern baltic sea. Microb. Ecol. 71, 789–801. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0714-4

Fodelianakis, S., Moustakas, A., Papageorgiou, N., Manoli, O., Tsikopoulou, I., Michoud, G., et al. (2017). Modified niche optima and breadths explain the historical contingency of bacterial community responses to eutrophication in coastal sediments. Mol. Ecol. 26, 2006–2018. doi: 10.1111/mec.13842

Fodelianakis, S., Papageorgiou, N., Pitta, P., Kasapidis, P., Karakassis, I., and Ladoukakis, E. D. (2014). The pattern of change in the abundances of specific bacterioplankton groups is consistent across different nutrient-enriched habitats in Crete. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3784–3792. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00088-14

Fuchs, B. M., Zubkov, M. V., Sahm, K., Burkill, P. H., and Amann, R. (2000). Changes in community composition during dilution cultures of marine bacterioplankton as assessed by flow cytometric and molecular biological techniques. Environ. Microbiol. 2, 191–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00092.x

Fuhrman, J. A., Hewson, I., Schwalbach, M. S., Steele, J. A., Brown, M. V., and Naeem, S. (2006). Annually reoccurring bacterial communities are predictable from ocean conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 13104–13109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602399103

Glaubitz, S., Abraham, W.-R., Jost, G., Labrenz, M., and Juergens, K. (2014). Pyruvate utilization by a chemolithoautotrophic epsilonproteobacterial key player of pelagic Baltic Sea redoxclines. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 87, 770–779. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12263

Glaubitz, S., Lueders, T., Abraham, W. R., Jost, G., Jürgens, K., and Labrenz, M. (2009). 13C-isotope analyses reveal that chemolithoautotrophic Gamma- and Epsilonproteobacteria feed a microbial food web in a pelagic redoxcline of the central Baltic Sea. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 326–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01770.x

Golebiewski, M., Calkiewicz, J., Creer, S., and Piwosz, K. (2017). Tideless estuaries in brackish seas as possible freshwater-marine transition zones for bacteria: the case study of the Vistula river estuary. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 9, 129–143. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12509

Gomez-Consarnau, L., Lindh, M. V., Gasol, J. M., and Pinhassi, J. (2012). Structuring of bacterioplankton communities by specific dissolved organic carbon compounds. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 2361–2378. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02804.x

Grote, J., Schott, T., Bruckner, C. G., Gloeckner, F. O., Jost, G., Teeling, H., et al. (2012). Genome and physiology of a model Epsilonproteobacterium responsible for sulfide detoxification in marine oxygen depletion zones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 506–510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111262109

Grubisic, L. M., Brutemark, A., Weyhenmeyer, G. A., Wikner, J., Bamstedt, U., and Bertilsson, S. (2012). Effects of stratification depth and dissolved organic matter on brackish bacterioplankton communities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 453, 37–48. doi: 10.3354/meps09634

Hagström, Å., Azam, F., Berg, C., and Zweifel, U. L. (2017). Isolates as models to study bacterial ecophysiology and biogeochemistry. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 80, 15–27. doi: 10.3354/ame01838

Hagström, Å., Pinhassi, J., and Zweifel, U. L. (2000). Biogeographical diversity among marine bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 21, 231–244. doi: 10.3354/ame021231

Hannig, M., Lavik, G., Kuypers, M. M. M., Woebken, D., Martens-Habbena, W., and Juergens, K. (2007). Shift from denitrification to anammox after inflow events in the central Baltic Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 1336–1345. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.4.1336

Herlemann, D. P., Labrenz, M., Jürgens, K., Bertilsson, S., Waniek, J. J., and Andersson, A. F. (2011). Transitions in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 5, 1571–1519. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.41

Herlemann, D. P. R., Lundin, D., Andersson, A. F., Labrenz, M., and Jürgens, K. (2016). Phylogenetic signals of salinity and season in bacterial community composition across the salinity gradient of the baltic sea. Front. Microbiol. 7:1883. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01883

Herlemann, D. P. R., Manecki, M., Meeske, C., Pollehne, F., Labrenz, M., Schulz-Bull, D., et al. (2014). Uncoupling of bacterial and terrigenous dissolved organic matter dynamics in decomposition experiments. PLoS ONE 9:e93945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093945

Hofle, M. G., and Brettar, I. (1995). Taxonomic diversity and metabolic-activity of microbial communities in the water column of the central baltic sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40, 868–874. doi: 10.4319/lo.1995.40.5.0868

Holmfeldt, K., Dziallas, C., Titelman, J., Pohlmann, K., Grossart, H. P., and Riemann, L. (2009). Diversity and abundance of freshwater Actinobacteria along environmental gradients in the brackish northern Baltic Sea. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2042–2054. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01925.x

Hoppe, H. G., Breithaupt, P., Walther, K., Koppe, R., Bleck, S., Sommer, U., et al. (2008). Climate warming in winter affects the coupling between phytoplankton and bacteria during the spring bloom: a mesocosm study. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 51, 105–115. doi: 10.3354/ame01198

Hu, Y. O. O., Karlson, B., Charvet, S., and Andersson, A. F. (2016). Diversity of pico- to mesoplankton along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol. 7:679. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00679

Hugerth, L. W., and Andersson, A. F. (2017). Analysing microbial community composition through amplicon sequencing: from sampling to hypothesis testing. Front. Microbiol. 8:1561. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01561

Hugerth, L. W., Larsson, J., Alneberg, J., Lindh, M. V., Legrand, C., Pinhassi, J., et al. (2015). Metagenome-assembled genomes uncover a global brackish microbiome. Gen. Biol. 16:279. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0834-7

Joint, I., Doney, S. C., and Karl, D. M. (2011). Will ocean acidification affect marine microbes? ISME J. 5, 1–7. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.79

Kaartokallio, H., Laamanen, M., and Sivonen, K. (2005). Responses of Baltic Sea ice and open-water natural bacterial communities to salinity change. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 4364–4371. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4364-4371.2005

Kaartokallio, H., Tuomainen, J., Kuosa, H., Kuparinen, J., Martikainen, P. J., and Servomaa, K. (2008). Succession of sea-ice bacterial communities in the Baltic Sea fast ice. Polar Biol. 31, 783–793. doi: 10.1007/s00300-008-0416-1

Kisand, V., Cuadros, R., and Wikner, J. (2002). Phylogeny of culturable estuarine bacteria catabolizing riverine organic matter in the northern Baltic Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 379–388. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.1.379-388.2002

Kisand, V., and Wikner, J. (2003). Combining culture-dependent and -independent methodologies for estimation of richness of estuarine bacterioplankton consuming riverine dissolved organic matter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 3607–3616. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3607-3616.2003

Klier, J., Dellwig, O., Leipe, T., Jürgens, K., and Herlemann, D. P. R. (2018). Benthic bacterial community composition in the oligohaline-marine transition of surface sediments in the Baltic Sea based on rRNA analysis. Front. Microbiol. 9:236. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00236

Koskinen, K., Hultman, J., Paulin, L., Auvinen, P., and Kankaanpää;, H (2011). Spatially differing bacterial communities in water columns of the northern Baltic Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 75, 99–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00987.x

Kritzberg, E., Cole, J. J., Pace, M. L., Granéli, W., and Bade, D. L. (2004). Autochthonous versus allochthonous carbon sources of bacteria: results from whole-lake C-13 addition experiments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 588–596. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.2.0588

Laas, P., Atova, E., Lips, I., Lips, U., Simm, J., Kisand, V., et al. (2016). Near-bottom hypoxia impacts dynamics of bacterioplankton assemblage throughout water column of the Gulf of Finland (Baltic Sea). PLoS ONE 11:e0156147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156147

Laas, P., Simm, J., Lips, I., Lips, U., Kisand, V., and Metsis, M. (2015). Redox-specialized bacterioplankton metacommunity in a temperate estuary. PLoS ONE 10:e0122304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122304

Laas, P., Simm, J., Lips, I., and Metsis, M. (2014). Spatial variability of winter bacterioplankton community composition in the Gulf of Finland (the Baltic Sea). J. Mar. Syst. 129, 127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2013.07.016

Labrenz, M., Jost, G., Pohl, C., Beckmann, S., Martens-Habbena, W., and Jürgens, K. (2005). Impact of different in vitro electron donor/acceptor conditions on potential chemolithoautotrophic communities from marine pelagic redoxclines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 6664–6672. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6664-6672.2005

Langenheder, S., Bulling, M. T., Solan, M., and Prosser, J. I. (2010). Bacterial biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relations are modified by environmental complexity. PLoS ONE 5:e10834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010834

Langenheder, S., Kisand, V., Lindstrom, E. S., Wikner, J., and Tranvik, L. J. (2004). Growth dynamics within bacterial communities in riverine and estuarine batch cultures. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 37, 137–148. doi: 10.3354/ame037137

Langenheder, S., Kisand, V., Wikner, J., and Tranvik, L. J. (2003). Salinity as a structuring factor for the composition and performance of bacterioplankton degrading riverine DOC. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45, 189–202. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00149-1

Larsson, J., Celepli, N., Ininbergs, K., Dupont, C. L., Yooseph, S., Bergman, B., et al. (2014). Picocyanobacteria containing a novel pigment gene cluster dominate the brackish water Baltic Sea. ISME J. 8, 1892–1903. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.35

Legrand, C., Fridolfsson, E., Bertos-Fortis, M., Lindehoff, E., Larsson, P., Pinhassi, J., et al. (2015). Interannual variability of phyto-bacterioplankton biomass and production in coastal and offshore waters of the Baltic Sea. AMBIO 44, 427–438. doi: 10.1007/s13280-015-0662-8

Leibold, M. A., Holyoak, M., Mouquet, N., Amarasekare, P., Chase, J. M., Hoopes, M. F., et al. (2004). The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecol. Lett. 7, 601–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x

Lindh, M., Sjöstedt, J., Casini, M., Andersson, A., Legrand, C., and Pinhassi, J. (2016). Local environmental conditions shape generalist but not specialist components of microbial metacommunities in the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol. 7:2078. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02078

Lindh, M. V. (2014). Bacterioplankton Population Dynamics in a Changing Ocean. Doctoral dissertation. Kalmar: Linnaeus University. Available online at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-38712

Lindh, M. V., Figueroa, D., Sjöstedt, J., Baltar, F., Lundin, D., Andersson, A., et al. (2015a). Transplant experiments uncover Baltic Sea basin-specific responses in bacterioplankton community composition and metabolic activities. Front. Microbiol. 6:223. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00223

Lindh, M. V., Lefebure, R., Degerman, R., Lundin, D., Andersson, A., and Pinhassi, J. (2015b). Consequences of increased terrestrial dissolved organic matter and temperature on bacterioplankton community composition during a Baltic Sea mesocosm experiment. AMBIO 44, S402–S412. doi: 10.1007/s13280-015-0659-3

Lindh, M. V., Maillot, B. M., Smith, C. R., and Church, M. J. (2018). Habitat filtering of bacterioplankton communities above polymetallic nodule fields and sediments in the Clarion-Clipperton zone of the Pacific Ocean. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 10, 113–122. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12627

Lindh, M. V., Riemann, L., Baltar, F., Romero-Oliva, C., Salomon, P. S., Graneli, E., et al. (2013). Consequences of increased temperature and acidification on bacterioplankton community composition during a mesocosm spring bloom in the Baltic Sea. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5, 252–262. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12009

Lindh, M. V., Sjöstedt, J., Andersson, A. F., Baltar, F., Hugerth, L. W., Lundin, D., et al. (2015c). Disentangling seasonal bacterioplankton population dynamics by high-frequency sampling. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 2459–2476. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12720

Lindh, M. V., Sjöstedt, J., Ekstam, B., Casini, M., Lundin, D., Hugerth, L. W., et al. (2017). Metapopulation theory identifies biogeographical patterns among core and satellite marine bacteria scaling from tens to thousands of kilometers. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 1222–1236. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13650

Lindroos, A., Marta Szabo, H., Nikinmaa, M., and Leskinen, P. (2011). Comparison of sea surface microlayer and subsurface water bacterial communities in the Baltic Sea. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 65, 29–42. doi: 10.3354/ame01532

Liu, Z., Cichocki, N., Bonk, F., Günther, S., Schattenberg, F., Harms, H., et al. (2018). Ecological stability properties of microbial communities assessed by flow cytometry. mSphere 3, e00564–17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00564-17

Logares, R., Lindstrom, E. S., Langenheder, S., Logue, J. B., Paterson, H., Laybourn-Parry, J., et al. (2013). Biogeography of bacterial communities exposed to progressive long-term environmental change. ISME J. 7, 937–948. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.168

Loreau, M. (2000). Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: recent theoretical advances. Oikos 91, 3–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.910101.x

Loreau, M. (2004). Does functional redundancy exist? Oikos 104, 606–611. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.12685.x

Massana, R., Pedrós Aliȯ, C., Casamayor, E. O., and Gasol, J. M. (2001). Changes in marine bacterioplankton phylogenetic composition during incubations designed to measure biogeochemically significant parameters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 1181–1188. doi: 10.4319/lo.2001.46.5.1181

Meier, H. E. M. (2006). Baltic Sea climate in the late twenty-first century: a dynamical downscaling approach using two global models and two emission scenarios. Climate Dyn. 27, 39–68. doi: 10.1007/s00382-006-0124-x

Morán, X.A., Alonso-Sáez, L., Nogueira, E., Ducklow, H. W., González, N., López-Urrutia, Á., et al. (2015). More, smaller bacteria in response to ocean's warming? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 282:20150371. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0371

Muren, U., Berglund, J., Samuelsson, K., and Andersson, A. (2005). Potential effects of elevated sea-water temperature on pelagic food webs. Hydrobiol 545, 153–166. doi: 10.1007/s10750-005-2742-4

Nagata, T. (2008). “Organic matter–bacteria interactions in seawater,” in Microbial Ecology of the Oceans, ed D. Kirchman. (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 1668–1681.

Omstedt, A., Elken, J., Lehmann, A., Leppäranta, M., Meier, H. E. M., Myrberg, K., et al. (2014). Progress in physical oceanography of the Baltic Sea during the 2003–2014 period. Progr. Oceanogr. 128, 139–171. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2014.08.010

Pante, E., and Simon-Bouhet, B. (2013). marmap: a package for importing, plotting and analyzing bathymetric and topographic data in R. PLoS ONE 8:e73051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073051

Pedler, B. E., Aluwihare, L. I., and Azam, F. (2014). Single bacterial strain capable of significant contribution to carbon cycling in the surface ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 111, 7202–7207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401887111

Pedros-Alio, C. (2006). Marine microbial diversity: can it be determined? Tr Microbiol 14, 257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.04.007

Pinhassi, J., and Hagström, Å. (2000). Seasonal succession in marine bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 21, 245–256. doi: 10.3354/ame021245

Pinhassi, J., Zweifel, U. L., and Hagström, Å. (1997). Dominant marine bacterioplankton species found among colony-forming bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3359–3366.

Piwosz, K., Salcher, M. M., Zeder, M., Ameryk, A., and Pernthaler, J. (2013). Seasonal dynamics and activity of typical freshwater bacteria in brackish waters of the Gulf of Gdansk. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 817–826. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.3.0817

Poisot, T., Pequin, B., and Gravel, D. (2013). High-throughput sequencing: a roadmap toward community ecology. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1125–1139. doi: 10.1002/ece3.508

Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., et al. (2013). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D.590–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219

R Core Development Team (2017). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/

Rahlff, J., Stolle, C., Giebel, H. A., Brinkhoff, T., Ribas-Ribas, M., Hodapp, D., et al. (2017). High wind speeds prevent formation of a distinct bacterioneuston community in the sea-surface microlayer. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93:fix041. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix041

Reindl, A. R., and Bolałek, J. (2017). Biological factor controlling methane production in surface sediment in the polish part of the Vistula Lagoon. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 46, 223–230. doi: 10.1515/ohs-2017-0022

Reunamo, A., Riemann, L., Leskinen, P., and Jorgensen, K. S. (2013). Dominant petroleum hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria in the Archipelago Sea in South-West Finland (Baltic Sea) belong to different taxonomic groups than hydrocarbon degraders in the oceans. Mar. Poll. Bull. 72, 174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.04.006

Reunamo, A., Yli-Hemminki, P., Nuutinen, J., Lehtoranta, J., and Jørgensen, K. S. (2017). Degradation of crude oil and pahs in iron–manganese concretions and sediment from the northern Baltic Sea. Geomicrobiol. J. 34, 385–399. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2016.1197987

Reyes, C., Schneider, D., Thürmer, A., Kulkarni, A., Lipka, M., Sztejrenszus, S. Y., et al. (2017). Potentially active iron, sulfur, and sulfate reducing bacteria in skagerrak and bothnian bay sediments. Geomicrobiol. J. 34, 840–850. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2017.1281360

Rieck, A., Herlemann, D., Jürgens, K., and Grossart, H.-P. (2015). Particle-associated differ from free-living bacteria in surface waters of the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol. 6:1297. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01297

Riemann, L., Leitet, C., Pommier, T., Simu, K., Holmfeldt, K., Larsson, U., et al. (2008). The native bacterioplankton community in the central Baltic sea is influenced by freshwater bacterial species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 503–515. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01983-07

Rowe, O. F., Dinasquet, J., Paczkowska, J., Figueroa, D., Riemann, L., and Andersson, A. (2018). Major differences in dissolved organic matter characteristics and bacterial processing over an extensive brackish water gradient, the Baltic Sea. Mar. Chem. 202, 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2018.01.010

Sala, M. M., Aparicio, F. L., Balagué, V., Boras, J. A., Borrull, E., Cardelús, C., et al. (2016). Contrasting effects of ocean acidification on the microbial food web under different trophic conditions. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 670–679. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv130

Salazar, G., Cornejo-Castillo, F. M., Benitez-Barrios, V., Fraile-Nuez, E., Alvarez-Salgado, X. A., Duarte, C. M., et al. (2016). Global diversity and biogeography of deep-sea pelagic prokaryotes. ISME J. 10, 596–608. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.137

Salka, I., Moulisova, V., Koblizek, M., Jost, G., Jürgens, K., and Labrenz, M. (2008). Abundance, depth distribution, and composition of aerobic bacteriochlorophyll a-producing bacteria in four basins of the central Baltic Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4398–4404. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02447-07

Salka, I., Wurzbacher, C., Garcia, S. L., Labrenz, M., Jürgens, K., and Grossart, H. P. (2014). Distribution of acI-actinorhodopsin genes in Baltic Sea salinity gradients indicates adaptation of facultative freshwater photoheterotrophs to brackish waters. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 586–597. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12185

Shade, A., Peter, H., Allison, S. D., Baho, D. L., Berga, M., Bürgmann, H., et al. (2012). Fundamentals of microbial community resistance and resilience. Front. Microbiol. 3:417. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00417

Simu, K., and Hagström, Å. (2004). Oligotrophic bacterioplankton with a novel single-cell life strategy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 2445–2451. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2445-2451.2004

Sipura, J., Haukka, K., Helminen, H., Lagus, A., Suomela, J., and Sivonen, K. (2005). Effect of nutrient enrichment on bacterioplankton biomass and community composition in mesocosms in the Archipelago Sea, northern Baltic. J. Plankt. Res. 27, 1261–1272. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbi092

Sjöstedt, J., Hagström, Å., and Zweifel, U. L. (2012a). Variation in cell volume and community composition of bacteria in response to temperature. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 66, 237–246. doi: 10.3354/ame01579

Sjöstedt, J., Koch-Schmidt, P., Pontarp, M., Canback, B., Tunlid, A., Lundberg, P., et al. (2012b). Recruitment of members from the rare biosphere of marine bacterioplankton communities after an environmental disturbance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1361–1369. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05542-11

Sommer, U., Aberle, N., Engel, A., Hansen, T., Lengfellner, K., Sandow, M., et al. (2007). An indoor mesocosm system to study the effect of climate change on the late winter and spring succession of Baltic Sea phyto- and zooplankton. Oecologia 150, 655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0539-4

Stolle, C., Labrenz, M., Meeske, C., and Jürgens, K. (2011). Bacterioneuston community structure in the southern Baltic sea and its dependence on meteorological conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 3726–3733. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00042-11

Stolle, C., Nagel, K., Labrenz, M., and Jürgens, K. (2010). Succession of the sea-surface microlayer in the coastal Baltic Sea under natural and experimentally induced low-wind conditions. Biogeosciences 7, 2975–2988. doi: 10.5194/bg-7-2975-2010

Sunagawa, S., Coelho, L. P., Chaffron, S., Kultima, J. R., Labadie, K., Salazar, G., et al. (2015). Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 348:1261359. doi: 10.1126/science.1261359

Tamelander, T., Spilling, K., and Winder, M. (2017). Organic matter export to the seafloor in the Baltic Sea: drivers of change and future projections. AMBIO 46, 842–851. doi: 10.1007/s13280-017-0930-x

Tammert, H., Lignell, R., Kisand, V., and Olli, K. (2012). Labile carbon supplement induces growth of filamentous bacteria in the Baltic Sea. Aquat. Biol. 15, 121–134. doi: 10.3354/ab00424

Tank, M., Bluemel, M., and Imhoff, J. F. (2011). Communities of purple sulfur bacteria in a Baltic Sea coastal lagoon analyzed by puf LM gene libraries and the impact of temperature and NaCl concentration in experimental enrichment cultures. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 78, 428–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01175.x

Teeling, H., Fuchs, B. M., Bennke, C. M., Krüger, K., Chafee, M., Kappelmann, L., et al. (2016). Recurring patterns in bacterioplankton dynamics during coastal spring algae blooms. eLife 5:e11888. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11888

Tiirik, K., Nõlvak, H., Oopkaup, K., Truu, M., Preem, J.-K., Heinaru, A., et al. (2014). Characterization of the bacterioplankton community and its antibiotic resistance genes in the Baltic Sea. Biotechn. Appl. Biochem. 61, 23–32. doi: 10.1002/bab.1144

Traving, S. J., Rowe, O., Jakobsen, N. M., Sorensen, H., Dinasquet, J., Stedmon, C. A., et al. (2017). The effect of increased loads of dissolved organic matter on estuarine microbial community composition and function. Front. Microbiol. 8:351. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00351

Tuomainen, J., Hietanen, S., Kuparinen, J., Martikainen, P., and Servomaa, K. (2006). Community structure of the bacteria associated with Nodularia sp. (cyanobacteria) aggregates in the Baltic Sea. Microb. Ecol. 52, 513–522. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9130-0

Vaquer-Sunyer, R., Conley, D. J., Muthusamy, S., Lindh, M. V., Pinhassi, J., and Kritzberg, E. S. (2015). Dissolved organic nitrogen inputs from wastewater treatment plant effluents increase responses of planktonic metabolic rates to warming. Environ. Sci. Techn. 49, 11411–11420. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00674

Vaquer-Sunyer, R., Reader, H. E., Muthusamy, S., Lindh, M. V., Pinhassi, J., Conley, D. J., et al. (2016). Effects of wastewater treatment plant effluent inputs on planktonic metabolic rates and microbial community composition in the Baltic Sea. Biogeosciences 13, 4751–4765. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-4751-2016

Vega Thurber, R., Willner-Hall, D., Rodriguez-Mueller, B., Desnues, C., Edwards, R. A., Angly, F., et al. (2009). Metagenomic analysis of stressed coral holobionts. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2148–2163. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01935.x

Viggor, S., Joesaar, M., Vedler, E., Kiiker, R., Paernpuu, L., and Heinaru, A. (2015). Occurrence of diverse alkane hydroxylase alkB genes in indigenous oil-degrading bacteria of Baltic Sea surface water. Mar. Poll. Bull. 101, 507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.10.064

Viggor, S., Juhanson, J., Joesaar, M., Mitt, M., Truu, J., Vedler, E., et al. (2013). Dynamic changes in the structure of microbial communities in Baltic Sea coastal seawater microcosms modified by crude oil, shale oil or diesel fuel. Microbiol Res. 168, 415–427. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.02.006

von Scheibner, M., Doerge, P., Biermann, A., Sommer, U., Hoppe, H.-G., and Juergens, K. (2014). Impact of warming on phyto-bacterioplankton coupling and bacterial community composition in experimental mesocosms. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 718–733. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12195

von Scheibner, M., Sommer, U., and Jürgens, K. (2017). Tight coupling of Glaciecola spp. and diatoms during cold-water phytoplankton spring blooms. Front. Microbiol. 8:27. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00027

Yeh, Y.-C., Peres-Neto, P. R., Huang, S.-W., Lai, Y.-C., Tu, C.-Y., Shiah, F.-K., et al. (2015). Determinism of bacterial metacommunity dynamics in the southern East China Sea varies depending on hydrography. Ecography 38, 198–212. doi: 10.1111/ecog.00986

Keywords: bacterial diversity, archaea, 16S rRNA, metabolic activity, ecosystem functioning, climate change

Citation: Lindh MV and Pinhassi J (2018) Sensitivity of Bacterioplankton to Environmental Disturbance: A Review of Baltic Sea Field Studies and Experiments. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:361. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00361

Received: 03 May 2018; Accepted: 19 September 2018;

Published: 10 October 2018.

Edited by:

Kristian Spilling, Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE), FinlandReviewed by:

Hermanni Kaartokallio, Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE), FinlandStilianos Fodelianakis, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2018 Lindh and Pinhassi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jarone Pinhassi, amFyb25lLnBpbmhhc3NpQGxudS5zZQ==

Markus V. Lindh

Markus V. Lindh Jarone Pinhassi

Jarone Pinhassi