95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 21 April 2015

Sec. Marine Ecosystem Ecology

Volume 2 - 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2015.00022

From photographic samples, we describe the benthic megafaunal communities in two north Svalbard fjords and on the adjacent continental shelf. We analyze the fauna in relation to abiotic factors of depth, bottom water temperature, percent cover of hard substrata, heterogeneity of stone size, and bottom-water turbidity to explore how these factors might affect the fauna and how they are related to the functional traits (size, morphology, mobility, colonial/solitary, and feeding type) of the megabenthos. Depth and bottom water temperature were consistently the strongest correlates with faunal composition and functional traits of the constituent species. A greater proportion of the variability in the functional traits of the megabenthos could be explained by abiotic factors rather than faunal composition, indicating that the abiotic factors of depth and temperature were strongly related to the functional traits of the megabenthos. On a local scale, stone size heterogeneity explained most variation in the functional traits of the megabenthos in one fjord. The results of this case study show a significant relationship between bottom water temperature and the functioning of north Svalbard megabenthic communities. If our results are representative for other areas, warming temperatures in the Arctic may decrease the variety of functional traits represented in Svalbard megabenthos, resulting in scavenger-dominated communities. A reduction in megabenthic biomass may also result, reducing energy availability to higher trophic levels.

The interplay between regional- and local-scale factors is an important determinant of diversity in biotic communities (Ricklefs, 1987), and marine benthic diversity can be influenced by factors at a variety of spatial scales (Gutt and Piepenburg, 2003; Gage, 2004; Robert et al., 2014). In the Arctic, environmental drivers such as depth, benthic food supply, and bottom oxygen affect megabenthic communities at regional scales, but factors such as substratum type and disturbance may be just as important in structuring communities on more local scales (Kuklinski et al., 2006a; Roy et al., 2014). Sensitivity of benthic communities to abiotic factors, therefore, will vary in different ways across these different scales, and this must be considered when monitoring programs are designed and their findings are interpreted.

Benthic communities off the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard are influenced by a variety of factors, including water mass distribution, sedimentation, climate forcing, availability of biotic and abiotic substrata, disturbance, and food input (Piepenburg et al., 1996; Kuklinski et al., 2006b; Carroll and Ambrose, 2012; Kędra et al., 2012; Kortsch et al., 2012; Bałazy and Kuklinski, 2013; Ronowicz et al., 2013). Despite recent research efforts (Sswat et al., 2015), our understanding of how abiotic factors influence the megabenthos around Svalbard remains limited. As future climatic changes are likely to be more dramatic in the Arctic than in other regions (ACIA, 2006; Mora et al., 2013), it is especially important to understand what factors influence these communities (Bergmann et al., 2011; Nephin et al., 2014).

Fjords are geologically young basins heavily influenced by terrestrial input (Syvitski et al., 1987). Fjord fauna are often considered to be subsets of shelf fauna, but recent evidence suggests this is not always the case (Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al., 2012). Generally, a decline in diversity is observed from outer to inner fjords, and this is usually attributed to gradients of glacial sedimentation (Görlich et al., 1987; Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al., 2005, 2012). Benthic megafaunal biomass and diversity are also generally lower in Arctic fjords compared to the shelf, a pattern that again is attributed to inorganic sedimentation (Syvitski et al., 1989; Piepenburg et al., 1996; Grange and Smith, 2013).

In the present analysis, we describe from photographic images the benthic megafaunal communities in two Svalbard fjords and on the north Svalbard shelf, as well as the dominant abiotic factors that appear to structure these communities. We focus in particular on functional traits of the benthic fauna.

Functional traits describe what organisms actually do in a community rather than their taxonomic classifications (Petchey and Gaston, 2002). Communities with greater functional diversity may be more resistant to invasion, have greater productivity or more efficient resource use, and provide a wider array of ecosystem services than those with lower functional diversity (Mason et al., 2005; Petchey and Gaston, 2006). Functional traits of the fauna may be more useful in explaining ecosystem processes than taxonomic analyses alone (Mokany et al., 2008; Bremner et al., 2013). Evenness of functional guilds has been found to decline from outer to inner regions of Svalbard fjords, with fewer suspension feeders, and more mobile, deposit-feeding organisms found in inner fjords (Włodarska-Kowalczuk, 2007; Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al., 2012). This most likely influences the complexity of ecosystem processes carried out by the benthos along the fjord gradient.

We set out to discern how the abiotic factors of depth, water temperature, availability of hard substrata, stone size heterogeneity, and inorganic sedimentation are related to megabenthic communities in north Svalbard fjords and on the nearby shelf. On the basis of previous macrofaunal studies, we expected that sedimentation would have a dominant effect on abundance and diversity. We also expected that assemblages of organisms with different functional traits would be found in different areas—shelf and inner and outer fjords—as a result of the influence of abiotic factors. We investigated different spatial scales by comparing stations among and within fjord and shelf areas.

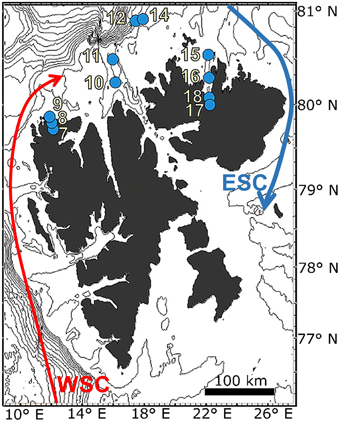

Photographs of the seafloor were recorded in Raudfjorden, Rijpfjorden, and on the north Svalbard shelf (Figure 1). Raudfjorden and Rijpfjorden are both predominantly north-facing fjords in the northern part of the Svalbard archipelago. Both have a maximum depth between 200 and 250 m (Holte and Gulliksen, 1998; Wang et al., 2013). Raudfjorden consists of a single basin and has a sill at the fjord mouth that rises to a depth of 130 m (Holte and Gulliksen, 1998). Rijpfjorden has a sill halfway down its length but opens widely onto a shallow shelf at 100–200 m depth (Ambrose et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2013).

Figure 1. Map of sampling stations in north Svalbard. Depth contours are shown every 150 m. WSC, West Spitsbergen Current (Atlantic Water); ESC, East Spitsbergen Current (Arctic Water).

Raudfjorden is largely influenced by Atlantic Water, a warm, saline water mass that continues onto the north Svalbard shelf (Muench et al., 1992; Holte and Gulliksen, 1998; Rudels et al., 2005). It also experiences a relatively high rate of inorganic sedimentation at 0.1–0.2 cm year−1 in the outer part of the fjord (Elverhøi et al., 1983), with sedimentation rate increasing toward the fjord head (Holte and Gulliksen, 1998).

In contrast, Rijpfjorden is a “true” Arctic fjord as it is primarily influenced by Arctic water and remains covered by ice for most of the year, from October to June or July (Morata et al., 2013). The melting process is dynamic, with snowmelt re-freezing as ice in the late spring (Wang et al., 2013). Even after landfast ice in Rijpfjorden has melted, ice floes are brought into the fjord by surface currents from the northeast, with the result that Rijpfjorden is covered by sea ice in various forms for most of the year (Ambrose et al., 2006; Leu et al., 2011). Because of its “true” Arctic character, Rijpfjorden has been the site of several studies designed to predict the effects of climate change on Arctic communities (Ambrose et al., 2006; Wallace et al., 2010; Leu et al., 2011; Morata et al., 2013).

The north Svalbard shelf stations included in this case study are located between 80 and 81°N. The north shelf is influenced by cooling AW at intermediate depth, though bottom water may be formed as dense plumes of cold brine that spill over the shelf following sea ice formation (Quadfasel et al., 1988; Rudels et al., 2005). The stations included in this case study are close to the winter ice edge, though the ice edge is dynamic and has retreated to the northeast since 1979 (Piechura and Walczowski, 2009; Onarheim et al., 2014). The stations in this case study are also in an area that may be subject to fishing activity (Norsk Fiskeridirektoratet).

Photographs were recorded using a downward-facing digital drop camera, as described by Sweetman and Chapman (2011). Photos were recorded at an altitude of approximately 2.5 m and were spaced about 10 m apart. Fixed laser points were used for size reference. All footage was recorded in September 2011 from the R/V Helmer Hanssen.

Images that were too dark, too turbid, showed evidence of fishing activity, or were at an anomalous altitude were considered ineligible for analysis. Of the eligible photos, 15 were randomly sub-selected from each station and analyzed using the cell counter function in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA). Percent cover of hard substrata was quantified as the number of random dots out of 100 overlying rock when projected on the image. Stone size heterogeneity was calculated as the coefficient of variation of the surface areas of 15 randomly sub-selected stones in each image (or all stones, if fewer than 15 were present).

Water temperature and turbidity were recorded with a Seabird SBE9/11+ CTD and attached turbidity sensor (Seapoint). Measurements were recorded at each station in August–September 2011 aboard the R/V Helmer Hanssen. Bottom temperature and bottom turbidity used for analysis in this case study are averaged over the bottom 10 m of the water column.

A conceptual outline of the statistical analyses in this study is shown in Figure 2. Biotic indices including total number of individuals (N), total number of species (S), Shannon–Wiener diversity (H′ based on natural log; Shannon and Weaver, 1963), Pielou evenness (J′; Pielou, 1969), and Margalef richness (d; Margalef, 1968), were calculated using Primer6 (Clarke and Gorley, 2006). Margalef richness was considered a more appropriate index of species richness than the number of species per image because the number of individuals per image varied widely among stations. Abiotic factors and biotic indices were compared among stations with a non-parametric analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis test, K-W) because data violated the assumption of homoscedasticity, even after log transformation. Dunn's test was used for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Multivariate analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) for all fauna was conducted based on a Bray–Curtis similarity matrix in Primer6. A DISTL-M procedure was used to discern the influence of abiotic factors on the fauna, and a dbRDA plot was constructed to visualize the fit of the DISTL-M model to the biotic data using the PERMANOVA+ add-on to Primer6 (Anderson et al., 2008).

In order to understand how abiotic factors related to the functional traits of organisms in the fjords and on the shelf, we constructed a “functional trait matrix” in which the abundance of individuals possessing each functional trait was listed instead of abundance of each morphotype. Functional traits included size, morphology (flat, mound, oblong, with walking legs, upright and simple, upright and branched), mobility (sessile, swimming, crawling), colonial/solitary (colony of zooids, sponge, single individual), and feeding mode (photosynthetic, suspension feeder, deposit feeder, predator, scavenger/opportunist). Because the functional traits we chose were categorical, it was not possible to use many of the indices which have been developed to measure functional diversity (Schleuter et al., 2010). We instead used multivariate statistical techniques and conducted the same analyses as we had done for the fauna sensu Bremner et al. (2013). A resemblance matrix was constructed based on Euclidean distances and was used as the basis for multivariate DISTL-M and dbRDA analyses (Figure 2).

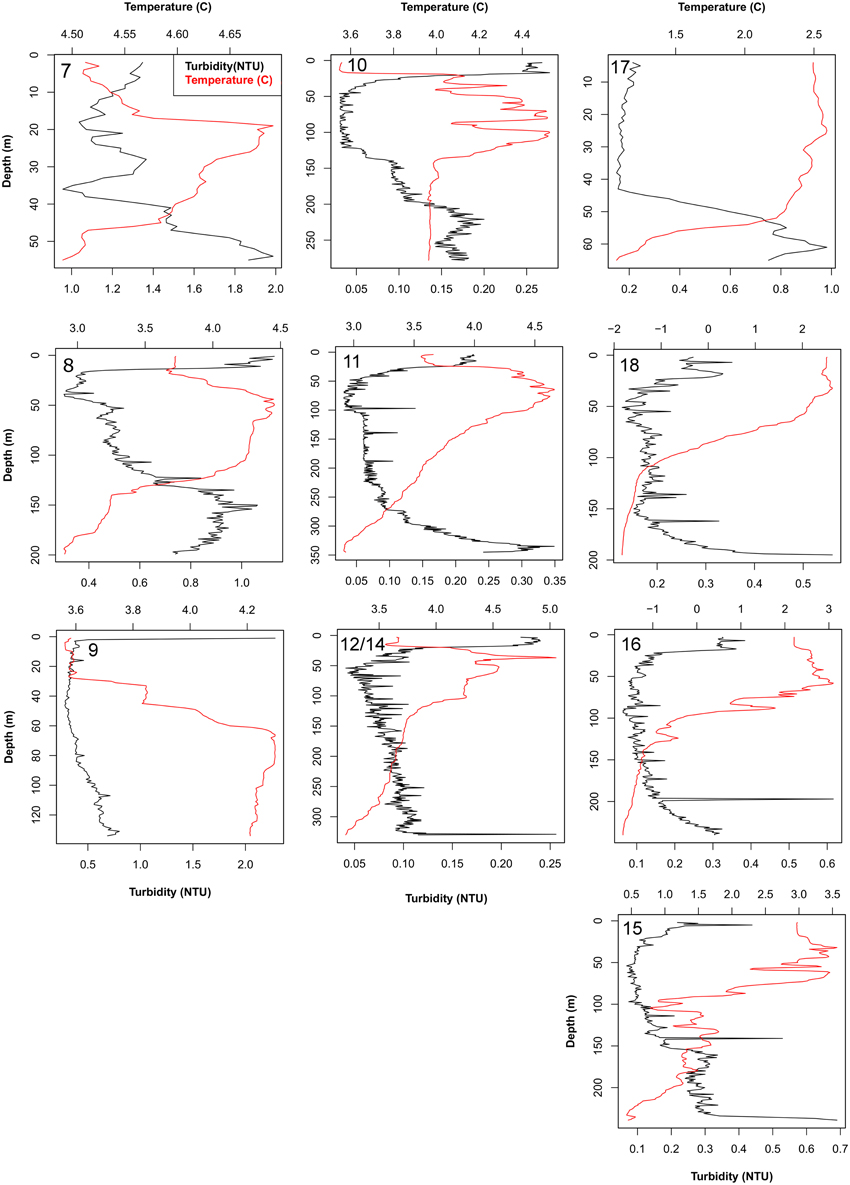

Bottom temperature was highest (+4.5°C) at station 7, in inner Raudfjorden, lower at the north shelf stations 11, 12, and 14 (2.92–3.25°C), and lowest in Rijpfjorden (−1.8–0.5°C; Figure 3). These values indicate greater influence of Atlantic water on stations in Raudfjorden and on the shelf and greater Arctic water influence in Rijpfjorden. Turbidity was highest at station 7, in Raudfjorden, and was generally much higher at stations in this fjord than at stations on the shelf. Rijpfjorden stations showed intermediate turbidity, with more turbid water being present at stations 17 and 18, in the inner part of the fjord (Figure 3).

Figure 3. CTD profiles showing temperature and turbidity of the water at each station. Numbers in bold indicate station. Note different scales of x- and y-axes.

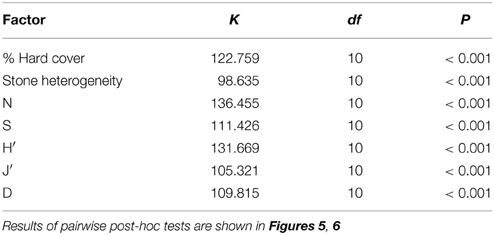

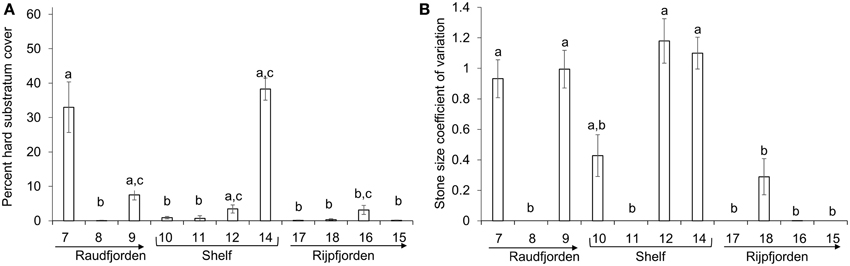

Percent hard substratum cover and stone size heterogeneity were found to be significantly different among stations (Table 1). A sample photo from each station is shown in Figure 4. Mean percent hard cover was highest at stations 7, in inner Raudfjorden (33.0 ± 7.4, mean ± standard error), and 14, on the north Svalbard shelf (38.3 ± 3.2), while stone size heterogeneity was highest at stations 7, 9, 12, and 14 (coefficients of variation 0.9–1.2; Figure 5).

Table 1. Results of Kruskal-Wallis tests for differences in biotic and abiotic factors among stations.

Figure 5. Abiotic factors at each north Svalbard station. (A) Average percent hard substratum cover per image, (B) average stone size heterogeneity (coefficient of variation) per image. Error bars represent standard error. Stations without any letters in common were found to be significantly different from each other in pairwise post-hoc analysis. Arrows point toward fjord mouth.

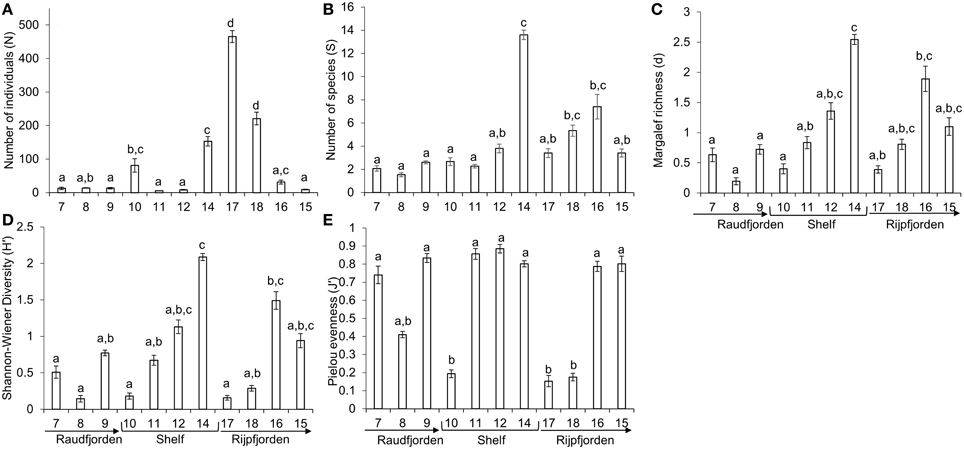

The distriubtions of each species and average densities at each station are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Multivariate analysis of similarity revealed overall significant differences among stations (ANOSIM, Global R = 0.827, p = 0.001). Significant differences were revealed for each of the indices N, S, H′, J′, and d among stations (Table 1). The highest average number of individuals (465.3 ± 17.8) was at station 17, in inner Rijpfjorden, and this was significantly different from every other station except station 18 in post-hoc analysis. However, the highest average number of species per image (13.6 ± 0.4) and the highest average H′ index (2.1 ± 0.04) were both found at station 14, on the north Svalbard shelf. Station 14 also showed the highest average Margalef richness (2.5 ± 0.1), though this was not significantly different from stations 12, 15, 16, or 18, on the outer shelf and in Rijpfjorden. Pielou evenness was significantly lower (0.15–0.19) at stations 10, 17, and 18, than all other stations except station 8 (0.41 ± 0.02) in mid Raudfjorden (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Biotic indices of richness, evenness, and diversity at each station in north Svalbard. (A) Average number of individuals per image, (B) average number of species per image, (C) Margalef richness, (D) Shannon-Wiener diversity index, (E) Pielou evenness index. Error bars represent standard error. Stations without any letters in common were found to be significantly different from each other in pairwise post-hoc analysis. Arrows point toward fjord mouth.

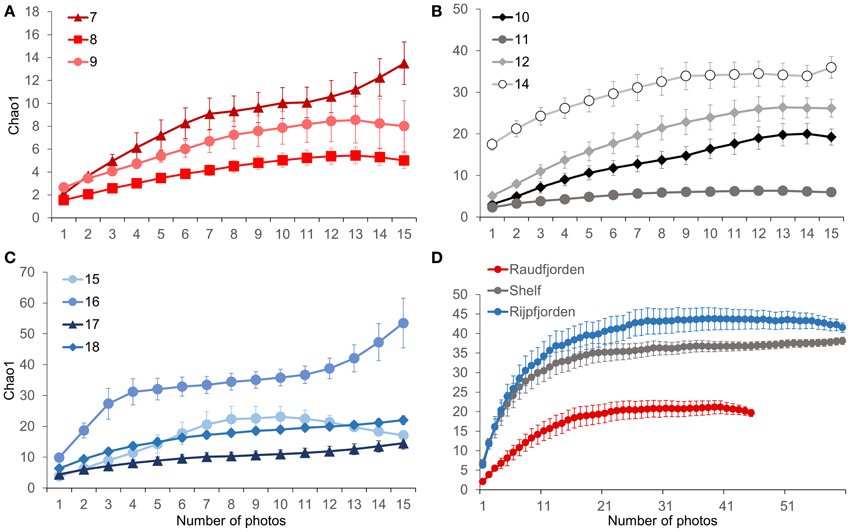

Because species-accumulation curves were not found to reach an asymptote for any station, we compared Chao1 richness values for each station using individual photos as replicates. Chao1 is a diversity index based on the number of rare species in a sample, designed to estimate species richness under the assumption that not every species present has been captured. Within Raudfjorden, station 7 in the inner fjord was found to have the highest estimated richness (13.5 ± 1.9), while station 8, in mid-Raudfjord, had the lowest (5.0 ± 0.7). On the shelf, stations 11 and 10, closer to land on the inner shelf, were found to have the lowest Chao1 richness (6.0 ± 0.7 and 19.3 ± 1.9, respectively), while stations 12 and especially 14 had the highest (26.2 ± 2.1 and 36.0 ± 2.6, respectively). Within Rijpfjorden, stations 17 and 18, in the inner fjord, had the lowest richness (14.5 ± 1.9 and 22.0 ± 1.4, respectively), but outermost station 15 also had similarly low richness (17.1 ± 0.6). It should be noted that the Chao1 richness values for these stations were still higher than for other stations in Raudfjorden and on the shelf, specifically 8, 9, and 11. Station 16 had the highest Chao1 richness within Rijpfjorden and indeed of all stations (53.5 ± 8.0; Figure 7). When Chao1 was calculated on a regional scale, with all Raudfjorden, shelf, and Rijpfjorden values combined, Rijpfjorden had the highest richness, though it was not significantly different from the shelf (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Chao1 species richness estimates. (A) Stations in Raudfjorden, (B) stations on the north Svalbard shelf, (C) stations in Rijpfjorden, (D) fjord and shelf regions combined. Error bars represent standard error.

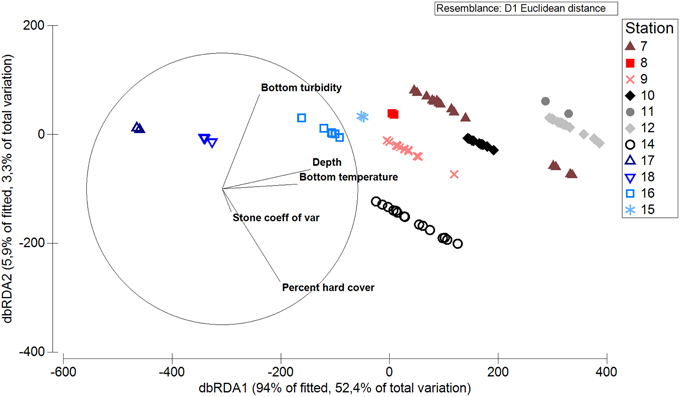

DISTL-M analysis revealed that each of the abiotic factors tested had a significant effect on the biotic data cloud (p = 0.001 for each factor in marginal tests). The abiotic factor that accounted for the highest proportion of variability in the biotic data was depth, with an R2-value of 0.11, followed in order by bottom temperature (R2 = 0.10), bottom turbidity (R2 = 0.08), percent hard substratum cover (R2 = 0.05), and stone size heterogeneity (R2 = 0.03). The best-fit forward-selected model included all abiotic variables and had an R2-value of 0.36, indicating that all abiotic factors together explained approximately 36% of the variability in the biotic data.

The accompanying dbRDA graph shows that stations separate along the axes of bottom temperature, bottom turbidity, and depth, indicating that these factors influence the differences in benthic communities among stations (Figure 8). Points belonging to the same station are spread out along the axes for percent hard substratum cover and stone size heterogeneity, indicating that these factors also influence the fauna but vary within stations. It should be noted that the y-axis captures much less (28%) of the variation in the data than the x-axis (40%). The four stations in Rijpfjorden are each represented by a close cluster of points, indicating lower intra-station heterogeneity of the community here than elsewhere. Points for Rijpfjorden are spatially separated from the other stations in the bottom left of the graph, indicating they are influenced by low temperature (Figure 8).

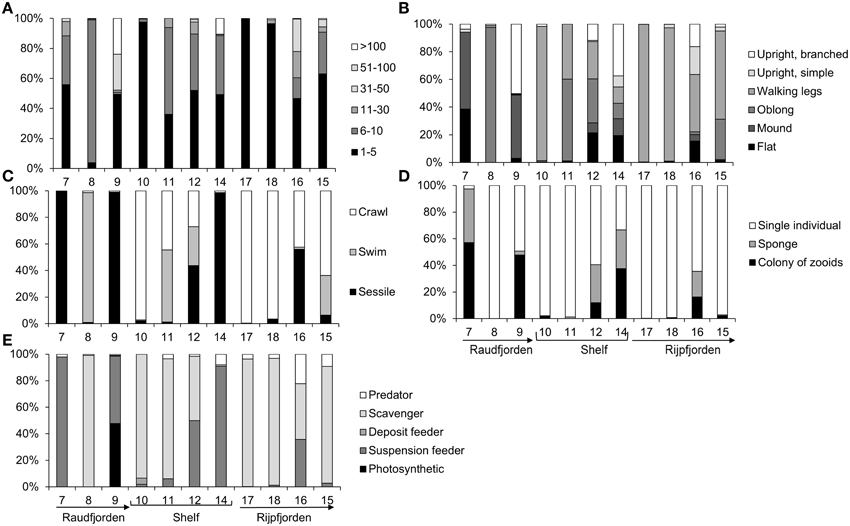

An examination of the functional traits of the fauna at each station reveals that stations 17 and 18, in inner Rijpfjorden, are almost entirely dominated by small, mobile, scavengers (Figure 9). Station 10 has a high proportion of mobile scavengers, while stations 8, 11, and 15 have high proportions of scavengers with various morphologies. Stations 7, 9, 12, 14, and 16 feature a high proportion of sessile suspension feeders, many of which are colonial (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Proportion of fauna at each north Svalbard station possessing different functional traits. (A) Size in vertically-facing view, cm, (B) basic morphology, (C) mobility, (D) colonial/solitary, (E) feeding mode. Arrows point toward mouth of each fjord.

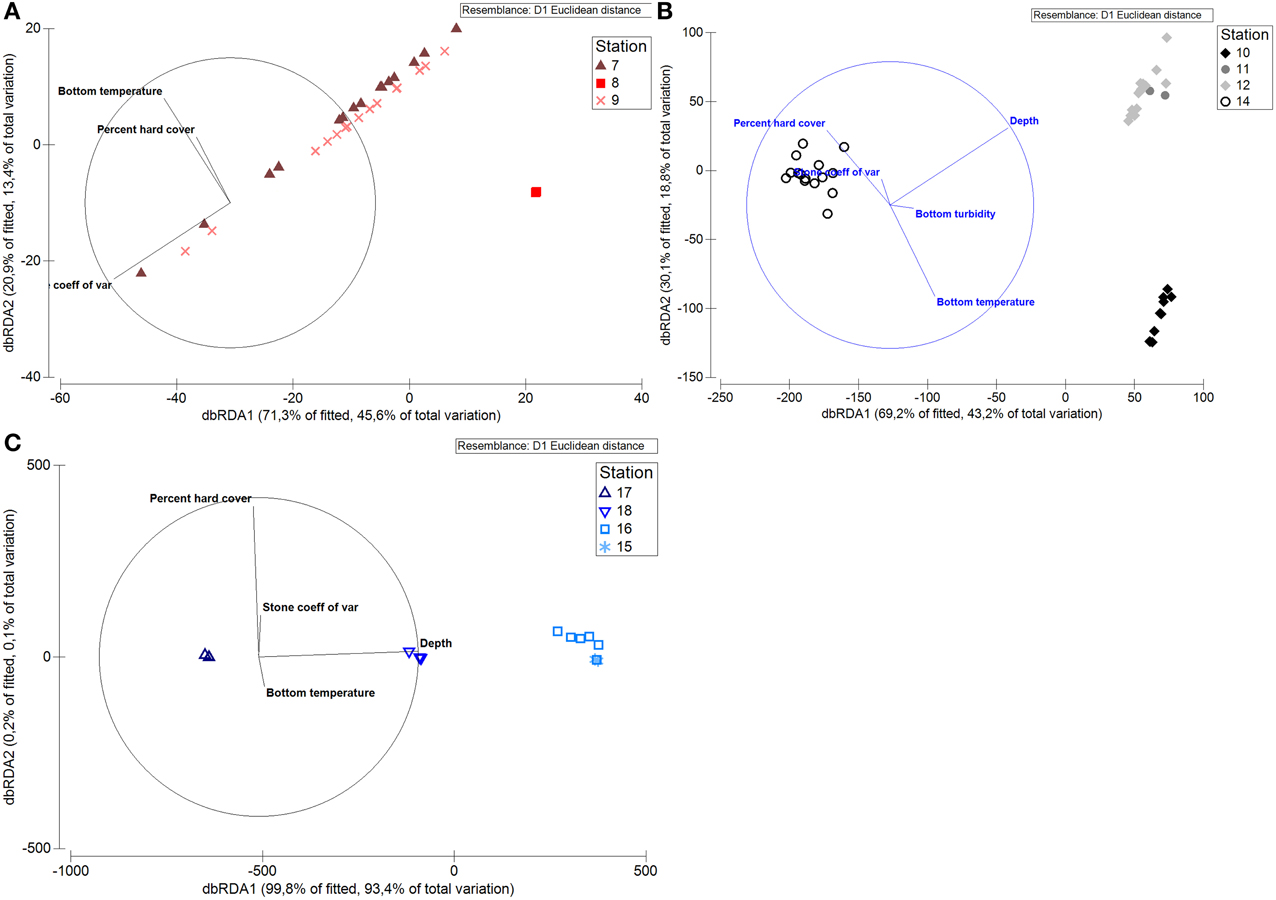

Results of a DISTL-M analysis show relationships between abiotic factors and the fauna at each station. All abiotic factors were found to be significantly related to the biotic data cloud (p = 0.001 in marginal tests) except for bottom turbidity (p = 0.203). The best-fit forward-selected model included all five abiotic factors and explained 56% of the variability in the functional trait data. Bottom temperature explained the largest amount of inter-station variability (36%; R2 = 0.36). Depth explained the second-largest amount of variation (12%; R2 = 0.12), and each of the other abiotic factors had R2-values orders of magnitude lower (0.04, 0.04, and 0.002 for bottom turbidity, percent hard substratum cover, and stone heterogeneity, respectively). In the accompanying dbRDA based on functional traits, stations separated widely along the axes of bottom temperature and depth. Some separation occurred between points from the same station along the axes relating to percent hard substratum cover and bottom turbidity, though a much lower proportion of variability was captured by this second axis (Figure 10).

Figure 10. dbRDA graph showing relationship of functional traits of north Svalbard fauna to abiotic factors.

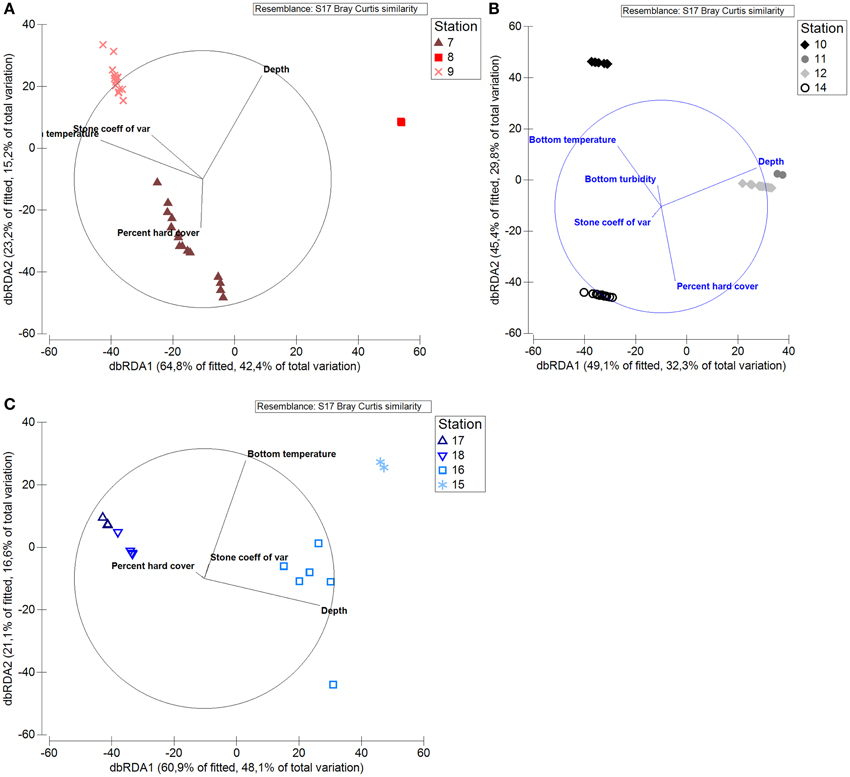

We also ran separate DISTL-M analyses for the shelf and each of the fjords. On this local scale, bottom temperature, and depth were once again the strongest correlates of fauna within Raudfjorden, Rijpfjorden, and the north Svalbard shelf, as they explained the largest proportions of variation in the biotic data within each local area. In Raudfjorden, R2-values were 0.38 and 0.19 for bottom temperature and depth, respectively. On the shelf, depth explained 31% of the variation in the data (R2 = 0.31) and temperature explained 27% (R2 = 0.27), while in Rijpfjorden, depth explained 40% of the variation in the data (R2 = 0.40) and bottom temperature explained 19% (R2 = 0.19). No other abiotic factors were nearly as important in explaining the variation in the data, as their R2-values were orders of magnitude lower (Figure 11).

Figure 11. dbRDA graph showing relationship of north Svalbard fauna to abiotic factors on local scale.(A) Stations in Raudfjorden, (B) stations on north Svalbard shelf, (C) stations in Rijpfjorden.

DISTL-M analysis of the functional traits on a local scale showed that functional traits of the fauna were influenced by different abiotic factors. For Raudfjorden, stone size heterogeneity explained 44% of the variability in the functional trait data cloud, and bottom temperature explained 13%. On the shelf, depth explained 38% of the variability in the functional trait data, and bottom temperature explained 20%. Depth was by far the most important factor in Rijpfjorden, explaining 93% of the variation in the data (Figure 12).

Figure 12. dbRDA graph showing relationship of functional traits of north Svalbard fauna to abiotic factors. (A) Stations in Raudfjorden, (B) stations on north Svalbard shelf, (C) stations in Rijpfjorden.

Our results indicated clear and significant differences in the benthic community within the same fjord, at stations spaced as little as 8 km apart. From this case study, we can therefore state that there was no single characteristic community for the fjords studied. Rather, distinct variations in the benthic community occurred along the fjord axis. Distributions of megafauna have seldom been documented for Svalbard fjords, so more research is required to determine if and to what extent patterns in the megafauna found in these fjords parallel patterns observed in other fjords and other major taxonomic groups (e.g., the macrofauna).

Roy et al. (2014) found that substratum type was more important in structuring benthic communities on local scales than on regional scales. However, in this case study, stone size heterogeneity explained only a small fraction of the variability in the local scale data, except for one case: the functional traits of fauna within Raudfjorden. Between fjords, stone size heterogeneity only explained a small fraction (3%) of the variability in the biotic data. While it is possible that habitat heterogeneity influences benthic megafauna on a larger spatial scale than was quantified here (approximately 40 m; Robert et al., 2014), it was not possible to quantify habitat heterogeneity on larger spatial scales in this case study. Nevertheless, our results do highlight the importance of considering habitat heterogeneity on different spatial scales.

Bottom water temperature and depth were the most important abiotic factors structuring both composition and functional traits of the fauna in every case except for Raudfjorden mentioned above. The results will therefore be discussed here in the context of temperature and depth primarily. Depth explained 11% of the variability in the composition and 12% of the variability in the functional traits of north Svalbard fauna in this case study. Strong depth gradients in the megabenthos have also been observed in the Kara Sea and in East Greenland (Mayer and Piepenburg, 1996; Jørgensen et al., 1999), though the latter case includes a greater range of depths than was quantified in this case study. In the Arctic, disturbance and competition have been shown to vary along depth gradients, but both factors are of little importance below approximately 40 m depth (Barnes and Kuklinski, 2004; Kuklinski, 2009). The sites included in this case study are located at 77–360 m, so of the factors correlated with depth, only benthic food supply is likely to be important. Food supply is generally negatively correlated with depth (Roy et al., 2014), but on local and meso-scales, structures such as polynyas and gyres can dramatically increase food supply to the benthos (Piepenburg, 2005). Lateral advection is also responsible for local-scale patterns of benthic food supply (Mayer and Piepenburg, 1996; Piepenburg, 2005). In a recent study, (Sswat et al., 2015) found that the north Svalbard shelf benthos was influenced by depth and substratum type, with higher diversity and abundance of sessile suspension feeders occurring at shallower stations. Station 14 in this case study had the highest abundance and diversity of suspension feeders and also the greatest availability of hard substrata (Figures 5, 9). This station sits at shallower depth (192 m) compared to the adjacent station 12 (360 m). It is possible that bottom currents at shallower depth carry away fine particles to expose large stones and also bring particulate food to the suspension feeders at station 14. A similar pattern has been observed at Hopen in the NW Barents Sea (Cochrane et al., 2009). Arctic megabenthic communities may also change as a function of depth because of distinct water masses impinging on the seafloor at different depths. In the Canadian Arctic, colder, fresher water of Pacific origin overlies warmer, saline Atlantic water, and this gradient has been hypothesized as a major structuring factor for the megafauna here (Roy et al., 2014). Horizontal gradients in water masses have also been shown to affect the megabenthos in the Barents Sea, with higher abundance of megafauna being found at Atlantic-influenced southern stations, where productivity was higher (Cochrane et al., 2009). Our results also show high abundance of megafauna at Atlantic-influenced shelf stations (Figure 6), but it cannot necessarily be stated that Atlantic water influence always leads to greater abundance and diversity of the megafauna, particularly in fjords because some Atlantic influenced fjord sites in this case study showed low megafaunal abundance and diversity (e.g., Stations 7–9, Figure 6).

Bottom water temperature (that was used as an indicator of Atlantic or Arctic water mass influence) at our sampling stations explained 10 and 36% of the variability in faunal composition and functioning, respectively. Stations in Raudfjorden were heavily influenced by Atlantic water masses (as indicated by the relatively higher temperatures, Figure 3) and showed lower faunal diversity, plus a lower variety of functional traits (primarily mobile scavengers with rare sessile suspension feeders, Figure 9). Stations in Raudfjorden had turbid bottom water (Figure 3), indicating heavy disturbance from glacial sedimentation, re-suspension, and/or terrestrial run-off. Inorganic sediment released by melting glaciers can smother organisms, clog filtering structures, dilute sediment organic material with inorganic particles, and reduce primary production by making the water column turbid, all of which can reduce biomass and diversity in glacial-influenced fjords (Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al., 2005). Stations in Raudfjorden had the lowest abundance of megafauna, indicating that it was difficult for more sedimentation-sensitive taxa to survive in this heavily-sedimented Atlantic-influenced fjord, such as sponges (that were dominant at the low turbidity station 14). Nevertheless, the dominant organisms at station 8 were shrimp of the species Pandalus borealis that have been shown to be sensitive to inorganic particles in the water (Dale et al., 2008).

By contrast, the low bottom water temperature in Rijpfjorden indicated that the fjord is heavily influenced by Arctic water masses. The Rijpfjorden megabenthic community had high diversity, as shown by the high Chao1 index (Figure 7) and also a wide variety of functional traits (e.g., predators, mobile scavengers, and sessile suspension feeders with various morphologies). A previous study at Arctic water mass-influenced stations in the Barents Sea has shown higher evenness and diversity of the megabenthos, despite lower abundance (Cochrane et al., 2009), and a body of recent research has shown that Arctic diversity is not as impoverished as previously believed (Piepenburg, 2005). The high diversity observed at the outer Rijpfjorden stations is reminiscent of Antarctic fjord communities, which show higher faunal and functional diversity than shelf stations at similar depth (Grange and Smith, 2013). Antarctic fjords are hypothesized to receive higher organic input than shelf stations in the form of macroalgal detritus, foraging krill, and whale excreta; however, the high diversity observed in Antarctic fjords more likely results from larval retention and lack of glacial sedimentation, because Antarctic fjords are at an earlier stage of warming than their Arctic counterparts (Grange and Smith, 2013). In this case study, Rijpfjorden was found to be primarily influenced by Arctic water masses and to have high faunal diversity and a variety of functional and trophic groups and relative low water column turbidity. It could thus be considered more comparable with diverse Antarctic fjords, which are at an earlier stage of warming and not heavily influenced by glacial sedimentation.

Changes in ocean temperature and biogeochemistry are predicted to be more extreme in the Arctic compared to other regions of the world ocean (Mora et al., 2013). The Arctic shelf seas are predicted to experience an increase in water temperature of 2–4°C by 2100, and this is a greater temperature increase than is predicted for the Antarctic (Mora et al., 2013, Figure 2A).

Food input to the seafloor may also increase in Arctic fjords with climate change if earlier ice break-up in spring leads to a mismatch between the spring bloom and the emergence of zooplankton, and tighter pelagic benthic coupling (Sokolova, 1994; Zajączkowski and Legeżyñska, 2001; Leu et al., 2011). It is unclear how north Svalbard megafauna may respond to increased benthic carbon flux, but it is possible that greater food flux could boost megafaunal biomass (Smith et al., 2008). However, warming will also potentially increase glacier activity, calving, and sedimentation (Hodson and Ferguson, 1999; Włodarska-Kowalczuk and Weslawski, 2001), which may in turn decrease megafaunal biomass and megabenthic functioning in north Svalbard. It is well documented that heavy inorganic sedimentation leads to reduced diversity and functional diversity of macrobiota (Syvitski et al., 1989; Piepenburg et al., 1996; Włodarska-Kowalczuk and Weslawski, 2001; Włodarska-Kowalczuk, 2007) and inorganic sedimentation can also reduce mesoscale heterogeneity of the benthic community (Włodarska-Kowalczuk and Weslawski, 2008). The diverse communities at stations 15 and 16 in outer Rijpfjorden and at stations on the shelf have a variety of trophic groups. By contrast, in the more heavily-sedimented inner fjord stations in both Raud- and Rijpfjorden, the community consists almost entirely of mobile scavengers. If our results are representative for other fjords and if it can be assumed that an Atlantic-influenced fjord is a good proxy for a warming Arctic fjord, an increase in sedimentation from rising temperatures and enhanced glacial melting may thus lead to a shift from suspension-feeding/detritivore communities to more necrophagous communities. If our results are indeed representative, warming temperatures could also lead to a reduction in megafauna abundance and biomass. Much higher megafaunal abundances were observed at the colder (17 and 18), and less turbid (18) stations in inner Rijpfjorden compared to the warmer, more turbid station 8 in Raudfjorden (Figure 6), even though all three stations were characterized by mobile scavengers and feature primarily soft substrata. Thus, warming and increased sedimentation, besides reducing functional diversity of the megabenthos, are likely to decrease the abundance and biomass. Such a reduction in abundance or biomass of the megabenthos may have major implications for Arctic fjord ecosystems (e.g., reducing energy transfer to predatory fishes and other higher trophic levels).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank the officers and crew of R/V Helmer Hanssen for their assistance at sea. Colin Griffiths processed CTD data. Robert Clarke (Plymouth Marine Laboratory) provided statistical guidance. We are grateful to Natalia Shunatova (Saint Petersburg State University), Dorte Janussen (Senckenberg Museum of Natural History), and Bjørn Gulliksen (University of Tromsø) for taxonomic assistance, and to Jørgen Berge for logistical support during the cruise. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-0829517. Additional support for this project was provided by the University Centre on Svalbard and Akvaplan-niva (to PER). AKS and PER collected the data; KSM analyzed the data; KSM wrote the manuscript; AKS, PER, and CMY edited the manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmars.2015.00022/abstract

ACIA. (2006). Arctic Climate Impact Assessment: Scientific Report. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ambrose, W. G., Carroll, M. L., Greenacre, M., Thorrold, S. R., and McMahon, K. W. (2006). Variation in Serripes groenlandicus (Bivalvia) growth in a Norwegian high-Arctic fjord: evidence for local- and large-scale climatic forcing. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 1595–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01181.x

Anderson, M. J., Gorley, R. N., and Clarke, K. R. (2008). PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods. Plymouth: PRIMER-E.

Bałazy, P., and Kuklinski, P. (2013). Mobile hard substrata—an additional biodiversity source in a high latitude shallow subtidal system. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 119, 153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2013.01.004

Barnes, D. K. A., and Kuklinski, P. (2004). Scale-dependent variation in competitive ability among encrusting Arctic species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 275, 21–32. doi: 10.3354/meps275021

Bergmann, M., Soltwedel, T., and Klages, M. (2011). The interannual variability of megafaunal assemblages in the Arctic deep sea: preliminary results from the HAUSGARTEN observatory (79°N). Deep Sea Res. I 58, 711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2011.03.007

Bremner, J., Rogers, S. I., and Frid, C. L. J. (2013). Assessing functional diversity in marine benthic ecosystems: a comparison of approaches. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 254, 11–25. doi: 10.3354/meps254011

Carroll, M. L., and Ambrose, W. G. (2012). Benthic infaunal community variability on the northern Svalbard shelf. Polar Biol. 35, 1259–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00300-012-1171-x

Cochrane, S., Denisenko, S. G., Renaud, P. E., Emblow, C. S., Ambrose, W. G., Ellingsen, I. H., et al. (2009). Benthic macrofauna and productivity regimes in the Barents Sea—ecological implications in a changing Arctic. J. Sea Res. 61, 222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2009.01.003

Dale, T., Kvassnes, A. J. S., and Iversen, E. R. (2008). Risikoen for Skader på Fisk og Blåskjell ved Gruveaktivitet på Engebøneset. Rapport Løpenr. 5689, Norsk Institutt for Vannforskning.

Elverhøi, A., Lønne, Ø., and Seland, R. (1983). Glaciomarine sedimentation in a modern fjord environment, Spitsbergen. Polar Res. 1, 127–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-8369.1983.tb00697.x

Gage, J. D. (2004). Diversity in deep-sea benthic macrofauna: the importance of local ecology, the larger scale, history and the Antarctic. Deep Sea Res. II 51, 1689–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2004.07.013

Görlich, K., Węsławski, J. M., and Zajączkowski, M. (1987). Suspension settling effect on macrobenthos biomass distribution in the Hornsund fjord, Spitsbergen. Polar Res. 5, 175–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-8369.1987.tb00621.x

Grange, L. G., and Smith, C. R. (2013). Megafaunal communities in rapidly warming fjords along the West Antarctic Peninsula: hotspots of abundance and beta diversity. Plos ONE 8:e77917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077917

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gutt, J., and Piepenburg, D. (2003). Scale-dependent impact on diversity of Antarctic benthos caused by grounding of icebergs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 253, 77–83. doi: 10.3354/meps253077

Hodson, A. J., and Ferguson, R. I. (1999). Fluvial suspended sediment transport from cold- and warm-based glaciers in Svalbard. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 24, 957–974.

Holte, B., and Gulliksen, B. (1998). Common macrofaunal dominant species in the sediments of some north Norwegian and Svalbard glacial fjords. Polar Biol. 19, 375–382. doi: 10.1007/s003000050262

Jørgensen, L. L., Pearson, T. H., Anisimova, N. A., Gulliksen, B., Dahle, S., Denisenko, S. G., et al. (1999). Environmental influences on benthic fauna associations in the Kara Sea (Arctic Russia). Polar Biol. 22, 395–416. doi: 10.1007/s003000050435

Kędra, M., Kukliński, K., Walkusz, W., and Legeżyńska, J. (2012). The shallow benthic food web structure in the high Arctic does not follow seasonal changes in the surrounding environment. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 114, 183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2012.08.015

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kortsch, S., Primicerio, R., Beuchel, F., Renaud, P. E., Rodrigues, J., Lønne, O. J., et al. (2012). Climate-driven regime shifts in Arctic marine benthos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 14052–14057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207509109

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kuklinski, P. (2009). Ecology of stone-encrusting organisms in the Greenland Sea—a review. Polar Res. 28, 222–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-8369.2009.00105.x

Kuklinski, P., Barnes, D. K. A., and Taylor, P. D. (2006a). Latitudinal patterns of diversity an abundance in North Atlantic intertidal boulder-fields. Mar. Biol. 149, 1577–1583. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0311-7

Kuklinski, P., Gulliksen, B., Lønne, O. J., and Weslawski, J. M. (2006b). Substratum as a structuring influence on assemblages of Arctic bryozoans. Polar Biol. 29, 652–661. doi: 10.1007/s00300-005-0102-5

Leu, E., Søreide, J. E., Hessen, D. O., Falk-Petersen, S., and Berge, J. (2011). Consequences of changing sea-ice cover for primary and secondary producers in the European Arctic shelf seas: timing, quantity, and quality. Prog. Oceanogr. 90, 18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2011.02.004

Mason, N. W. H., Mouillot, D., Lee, W. G., and Wilson, J. B. (2005). Functional richness, functional evenness, and functional divergence: the primary components of functional diversity. Oikos 111, 112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13886.x

Mayer, M., and Piepenburg, D. (1996). Epibenthic community patterns on the continental slope off East Greenland at 75°N. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 143, 151–164. doi: 10.3354/meps143151

Mokany, K., Ash, J., and Roxburgh, S. H. (2008). Functional identity is more important than diversity in influencing ecosystem processes in a temperate native grassland. J. Ecol. 96, 884–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01395.x

Mora, C., Wei, C.-L., Rollo, A., Amaro, T., Baco, A. R., Billett, D., et al. (2013). Biotic and human vulnerability to projected changes in ocean biogeochemistry over the 21st century. Plos Biol. 11:e1001682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001682

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Morata, N., Michaud, E., and Włodarska-Kowalczuk-Kowalczuk, M. (2013). Impact of early food input on the Arctic benthos activities during the polar night. Polar Biol. 38, 99–114. doi: 10.1007/s00300-013-1414-5

Muench, R. D., McPhee, M. G., Paulson, C. A., and Morison, J. H. (1992). Winter oceanographic conditions in the Fram Strait—Yermak Plateau region. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 3469–3483. doi: 10.1029/91JC03107

Nephin, J., Juniper, S. K., and Archambault, P. (2014). Diversity, abundance and community structure of benthic macro- and megafauna on the Beaufort shelf and slope. Plos ONE 9:e101556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101556

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Onarheim, I. H., Smedsrud, L. H., and Ingvaldsen, R. B. (2014). Loss of sea ice during winter north of Svalbard. Tellus A 66:23933. doi: 10.3402/tellusa.v66.23933

Petchey, O. L., and Gaston, K. J. (2002). Functional diversity (FD), species richness and community composition. Ecol. Lett. 5, 402–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00339.x

Petchey, O. L., and Gaston, K. J. (2006). Functional diversity: back to basics and looking forward. Ecol. Lett. 9, 741–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00924.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Piechura, J., and Walczowski, W. (2009). Warming of the West Spitsbergen current and sea ice north of Svalbard. Oceanologia 51, 147–164. doi: 10.5697/oc.51-2.147

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Piepenburg, D. (2005). Recent research on Arctic benthos: common notions need to be revised. Polar Biol. 28, 733–755. doi: 10.1007/s00300-005-0013-5

Piepenburg, D., Chernova, N. V., von Dorrien, C. F., Gutt, J., Neyelov, A. V., Rachor, E., et al. (1996). Megabenthic communities in the waters around Svalbard. Polar Biol. 16, 431–446. doi: 10.1007/s003000050074

Quadfasel, D., Rudels, B., and Kurz, K. (1988). Outflow of dense water from a Svalbard fjord into the Fram Strait. Deep Sea Res. 35, 1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/0198-0149(88)90006-4

Ricklefs, R. E. (1987). Community diversity: relative roles of local and regional processes. Science 235, 167–171. doi: 10.1126/science.235.4785.167

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Robert, K., Jones, D. O. B., and Huvenne, V. A. I. (2014). Megafaunal distribution and biodiversity in a heterogenous landscape: the iceberg-scoured Rockall Bank, NE Atlantic. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 501, 67–88. doi: 10.3354/meps10677

Ronowicz, M., Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M., and Kuklinski, P. (2013). Hydroid epifaunal communities in Arctic coastal waters (Svalbard): effects of substrate characteristics. Polar Biol. 36, 705–718. doi: 10.1007/s00300-013-1297-5

Roy, V., Iken, K., and Archambault, P. (2014). Environmental drivers of the Canadian Arctic megabenthic communities. Plos ONE 9:e100900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100900

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rudels, B., Göran, B., Nilsson, J., Winsor, P., Lake, I., and Nohr, C. (2005). The interaction between waters from the Arctic Ocean and the Nordic Seas north of Fram Strait and along the East Greenland Current: results from the Arctic Ocean-02 Oden Expedition. J. Mar. Syst. 55, 1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2004.06.008

Schleuter, D., Daufresne, M., Massol, F., and Argillier, C. (2010). A user's guide to functional diversity indices. Ecol. Monogr. 80, 469–484. doi: 10.1890/08-2225.1

Shannon, C. E., and Weaver, W. (1963). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Smith, C. R., De Leo, F. C., Bernardino, A. F., Sweetman, A. K., and Arbizu, P. M. (2008). Abyssal food limitation, ecosystem structure, and climate change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.002

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sokolova, M. N. (1994). Euphausiid “dead body rain” as a source of food for abyssal benthos. Deep Sea Res. I 41, 741–746. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(94)90052-3

Sswat, M., Gulliksen, B., Menn, I., Sweetman, A. K., and Piepenburg, D. (2015). Distribution and composition of the epibenthic megafauna north of Svalbard (Arctic). Polar Biol. doi: 10.1007/s00300-015-1645-8

Sweetman, A. K., and Chapman, A. (2011). First observations of jelly-falls at the seafloor in a deep-sea fjord. Deep Sea Res. I 58, 1206–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2011.08.006

Syvitski, J. P. M., Burrell, D. C., and Skei, J. M. (1987). Fjords: Processes and Products. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4632-9

Syvitski, J. P. M., Farrow, G. E., Atkinson, R. J. A., Moore, P. G., and Andrews, J. T. (1989). Baffin Island fjord macrobenthos: bottom communities and environmental significance. Arctic 42, 232–247. doi: 10.14430/arctic1662

Wallace, M. I., Cottier, F. R., Berge, J., Tarling, G. A., Griffiths, C., and Brierley, A. S. (2010). Comparison of zooplankton vertical migration in an ice-free and a seasonally ice covered Arctic fjord: an insight into the influence of sea ice cover on zooplankton behavior. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 831–845. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.55.2.0831

Wang, C., Shi, L., Gerland, S., Granskog, M. A., Renner, A. H. H., Li, Z., et al. (2013). Spring sea-ice evolution in Rijpfjorden (80°N), Svalbard, from in situ measurements and ice mass-balance buoy (IMB) data. Ann. Glaciol. 54, 253–260. doi: 10.3189/2013AoG62A135

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M. (2007). Molluscs in Kongsfjorden (Spitsbergen, Svalbard): a species list and patterns of distribution and diversity. Polar Res. 26, 48–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-8369.2007.00003.x

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M., and Weslawski, J. M. (2001). Impact of climate warming on Arctic benthic biodiversity: a case study of two Arctic glacial bays. Clim. Res. 18, 127–132. doi: 10.3354/cr018127

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M., and Weslawski, J. M. (2008). Mesoscale spatial structures of soft bottom macrozoobenthos communities: effects of physical control and impoverishment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 356, 215–224. doi: 10.3354/meps07285

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M., Pearson, T. H., and Kendall, M. A. (2005). Benthic response to chronic natural physical disturbance by glacial sedimentation in an Arctic fjord. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 303, 31–41. doi: 10.3354/meps303031

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M., Renaud, P. E., Weslawski, J. M., Cochrane, S. K. J., and Denisenko, S. G. (2012). Species diversity, functional complexity, and rarity in Arctic fjordic versus open shelf benthic systems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 463, 73–87. doi: 10.3354/meps09858

Keywords: Svalbard, benthic, image analysis, functional diversity, monitoring

Citation: Meyer KS, Sweetman AK, Young CM and Renaud PE (2015) Environmental factors structuring Arctic megabenthos—a case study from a shelf and two fjords. Front. Mar. Sci. 2:22. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2015.00022

Received: 08 December 2014; Accepted: 31 March 2015;

Published: 21 April 2015.

Edited by:

Alberto Basset, University of Salento, ItalyReviewed by:

Donata Melaku Canu, Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale, ItalyCopyright © 2015 Meyer, Sweetman, Young and Renaud. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew K. Sweetman, International Research Institute of Stavanger, Marine Environment, Mekjarvik 12, 4070 Randaberg, NorwayYW5kcmV3LnN3ZWV0bWFuQGlyaXMubm8=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.