- 1Department of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 2Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 3Health Economics Leadership and Translational Research Group, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

- 4Malaria Consortium, Cambridge Health, London, United Kingdom

- 5Department of Pediatrics, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

There has been significant progress in malaria prevention over the past 20 years, but the impact of current interventions may have peaked and in moderate to high malaria transmission areas, the earlier gains either have since stalled or reversed. Newer and more innovative strategies are urgently needed. These may include different chemoprevention strategies, vaccines, and injectable forms of long-acting antimalarial drugs used in combination with other interventions. In this paper, we describe the different chemoprevention strategies; their efficacy, cost-effectiveness, uptake, potential impact, and contextual factors that may impact implementation. We also assess their effectiveness in reducing the malaria burden and emerging concerns with uptake, drug resistance, stock-outs, funding, and equity and suggestions to improve application.

1 Introduction

Malaria remains a leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Recent progress in eradication (World Health Organization, 2023a) has mostly been achieved through increased investment in control strategies including the use of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), the use of larvicides, better access to diagnostic services, treatment with effective therapies (Bhatt et al., 2015) and lately, vaccines. Although the global malaria community is targeting a malaria-free world, progress towards elimination has stalled. In 2022, there was a 5 million global increase in cases compared with 2021 (World Health Organization, 2023a) and approximately 94% of these cases reported were in the WHO African Region. There is, therefore, an urgent need for innovations in control measures in addition to reviewing the current elimination strategies.

Chemoprevention as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is the use of full therapeutic courses of antimalarial medicines at prescheduled times, irrespective of infection status, to treat existing infections and prevent new infections and thus reduce malaria in people living in an endemic area (World Health Organization, 2023b). It differs from malaria chemoprophylaxis as this involves the administration of sub-therapeutic doses of antimalarial agents to prevent new infections and is primarily used by non-immune people traveling to malaria-endemic areas (World Health Organization, 2023b). Malaria chemoprevention strategies for children include perennial malaria chemoprevention (PMC) previously known as intermittent preventive treatment in infants (IPTi), intermittent preventive treatment in school-aged children (IPTsc), seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), and post-discharge malaria chemoprevention (PDMC) (World Health Organization, 2023b) (Table 1). These interventions may be deployed jointly or in combination with otherstrategies including malaria vaccines, monoclonal antibodies (Miura et al., 2024), injectable forms of long-acting antimalarial drugs, and genetically modified mosquitoes (Aleshnick et al., 2022; Jones, 2023; World Health Organization, 2023b; Wang et al., 2024).

This review examines the different malaria chemoprevention and vaccine strategies, challenges in their deployment, research gaps that may underpin further implementation, and the potential impact in reducing morbidity and mortality of malaria in children. It also makes available to policy and decision makers context-specific control interventions for different countries.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy

We conducted a search of PUBMED and Google Scholar for studies on malaria chemoprevention and vaccination strategies in sub-Saharan Africa between June 2023 to October 2023 published between 1st Jan 2008 to 31st Dec 2023. The search was revised and conducted again in April 2024 to update it to 30th April 2024. The search terms were ‘chemoprevention’, ‘chemoprophylaxis’, ‘malaria’, ‘Plasmodium falciparum’, ‘malaria vaccine’, ‘RTS, S’, ‘RTS, S/AS01’, ‘R21/Matrix-M’, ‘Mosquirix’, ‘approved’, ‘effectiveness’, ‘efficacy’, ‘cost’, ‘cost-effectiveness’, ‘feasibility’, ‘acceptability’, ‘challenges’, ‘perennial malaria chemotherapy’, ‘Intermittent preventive therapy’, ‘infants’, ‘school’, ‘children’, ‘seasonal malaria’ post-discharge malaria’, ‘sub-Sahara Africa’, ‘implementation challenges’, and ‘challenges’. Articles were also included if they reported on uptake, acceptability, and the impact of implementing chemoprevention and vaccines on malaria burden to help guide policy decisions. The search terms were combined using Boolean operations ‘OR’, and ‘AND’. Search articles were included if they were in English and peer-reviewed, and reported studies on malaria chemoprevention and/or vaccines in children (<15 years) in sub-Saharan Africa. Article screening was done in duplicate by two independent reviewers (WN and OM). Any disagreement between the reviewers was resolved through discussion and consensus. The articles from the search were transferred into Endnote and de-duplicated.

Extraction of data was done using a tool developer in Excel spreadsheet and focused on the following review outcomes, efficacy and effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, resistance, feasibility, acceptability, and implementation challenges. Data was analyzed using narrative synthesis.

3 Malaria chemoprevention and vaccine strategies in children

3.1 Perennial malaria chemoprevention

In moderate to high malaria transmission settings, perennial malaria chemoprevention (PMC) previously known as the intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in infants (IPTi) has been proposed. Table 1 Pooled data from randomized controlled trials by Esu et al. (2021) in Kenya, Mali, Uganda, Tanzania, Mozambique, Gabon, and Ghana demonstrated that overall, PMC had a protective efficacy of 30% (rate ratio 0.70, 95% CI 0.62–0.80) with monthly sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) having the least protective efficacy (rate ratio 0.78: 95% CI 0.69–0.88) compared with monthly Artesunate-Amodiaquine (AS-AQ) (rate ratio 0.75: 95% CI 0.61–0.94), and monthly dihydro-artemisinin piperaquine (DP) (rate ratio 0.42: 95% CI 0.33–0.54). The lower protective efficacy of SP was attributed to widespread resistance to SP and the potential reduction of its effectiveness as PMC. The strategy was also shown to benefit children 12 to 24 months (Kobbe et al., 2007; Bigira et al., 2014) and since then, the WHO recommended the removal of the 12-month age restriction and number of doses to be administered so that older children would also benefit.

3.1.1 Acceptability and delivery of PMC

Despite the anticipated benefits, implementation of PMC has been faced with multiple challenges resulting in low uptake in most malaria-endemic countries. First, the recommendation was made when there were significant concerns about increasing parasite resistance to SP in many endemic countries. Secondly, the process of translating the research into policy was slow. Indeed, by 2008, members of the then PMC consortium had already expressed concerns about the delays in the WHO review processes (Cruz and Walt, 2013). Also, the acceptability of PMC by policymakers was delayed because of inconsistencies in the reported protective effect of the intervention: 30% versus 59% from the first trial on PMC (De Sousa et al., 2012). Coupled with the lack of pediatric formulations and failure to fully understand PMC, these factors together contributed to a break in trust in PMC by the key stakeholders in communities (Looman and Pell, 2021). Despite these challenges, PMC has generally been well-accepted in the few areas where it has been implemented. This is especially when integrated into the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) (Pool et al., 2008; Gysels et al., 2009; De Sousa et al., 2012). Hence, we recommend that PMC be delivered through EPI platforms. Thus, in both Mozambique (Pool et al., 2006) and Tanzania (Pool et al., 2008), PMC was generally well accepted by the community and healthcare workers. In these studies, the high acceptance of PMC in the communities was because PMC resonated with the traditional belief that infants need protection and mothers took the infants to the EPI clinics with the hope that they would get protection from illness.

The lessons learned from the failings of PMC policy could help improve the deployment of other chemoprevention strategies. This includes the need for clarity in understanding and building consensus among groups with different stakeholders prior to implementation. There is also need for explicit and transparent program reviews, to provide an understanding of how health system challenges differ in real-life settings.

3.2 Seasonal malaria chemoprevention

Since 2012, there has been a shift towards targeted malaria control for specific populations and geographical areas defined by risk status and unique conditions (Ashley and Yeka, 2020). SMC is has been examined and implemented in especially the Sahel region, where malaria transmission is seasonal, and most childhood malaria illnesses and deaths occur during the rainy season (World Health Organization, 2023b) (Table 1). At least 17 countries (Mozambique, Uganda, Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, The Gambia, Mauritania, South Sudan and Senegal) have already embraced SMC (World Health Organization, 2023c).

In 2012, SMC was recommended for children aged 3 to 59 months living in the high yet seasonal malaria transmission areas of the Sahel using SP plus amodiaquine (SP+AQ) (World Health Organization, 2012). A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis of SMC among children up to 15 years of age and with up to six monthly SMC cycles with SP plus AQ, AQ plus AS, and SP plus AS found marked reductions in uncomplicated malaria (rate ratio 0.27: 95% CI 0.25–0.29 among children younger than 5 years and similar reductions, rate ratio 0.27: 95% CI 0.25–0.30, among children 5 years and older. The prevalence of malaria parasitemia measured within 4–6 weeks from the final SMC cycle was also markedly reduced: risk ratio 0.38: 95% CI 0.34–0.43 among children <5 years and risk ratio 0.23: 95% CI 0.11–0.48 among children 5 years and older (Thwing et al., 2024).

The WHO malaria guidelines have now been updated and it is recommended that the target age group for SMC should be guided by local data (World Health Organization, 2023b). For example, in Uganda, stratification and identification of regions most suitable for SMC were supported by modeling data that suggested SMC would be a viable prevention strategy in Karamoja, a region with high malaria prevalence rates yet seasonal malaria transmission (Owen et al., 2022). The Malaria Consortium is currently conducting a series of studies among children aged 3 to 59 months in the Karamoja region. Initial results from these study showed that SMC using SP-AQ is highly efficacious against malaria (Malaria Consortium, 2022; Nuwa et al., 2023).

3.2.1 Acceptability and delivery of SMC

SMC delivery and coverage differs across countries; in the Sahel, SMC is distributed in four cycles every year during the rainy season, with distribution intervals of about 28 days while in other areas, an additional cycle has been suggested due to longer transmission periods (World Health Organization, 2023c). Indeed, a scoping review that examined data from 2019 to 2023 noted that four courses of SMC are insufficient to cover the entire malaria transmission season and in areas where peak transmission lasts longer, additional doses are needed to consolidate SMC efforts (Xu et al., 2023).

The delivery approaches recommended are either door-to-door or fixed-point delivery (World Health Organization, 2023b). Studies in Mali showed that coverage of SMC was high for children who received SMC using the door-to-door approach at 74% (95% CI 69–80%) compared to fixed point delivery system with 60% (95% CI 50–70%; p=0.009) (Barry et al., 2018). Findings were similar in the Gambia, 74% versus 48% (Bojang et al., 2011). In Uganda, SMC was using the door-to-door delivery mechanism which achieved a high coverage of 98% (Kajubi et al., 2023; Nuwa et al., 2023). These successes suggest that SMC programs are best delivered using a door-to-door delivery mechanism.

A study conducted in eight countries (Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Uganda) showed SMC is highly acceptable (more than 80%) by the community (Audibert and Tchouatieu, 2021). The high levels of acceptability are especially attributed to the perceived effectiveness. In Ghana, mothers believed that the SMC drugs reduced the burden of malaria in the area (Chatio et al., 2019). In Nigeria, high acceptability was associated with the use of sweetened dispersible tablets, the switch to door-to-door delivery, the hiring of community drug distributors from the same communities where the participants come from, the participation of regional traditional leaders in the SMC campaign, and the capacity to establish rapport with caregivers (Ogbulafor et al., 2023).

3.3 Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in school-aged children

Standard malaria interventions and surveillance policies have largely targeted children under 5 years of age and pregnant women. School-age children have largely been neglected (Walldorf et al., 2015) due to the traditionally lower morbidity and occurrence of severe outcomes in this group (Van Nguyen et al., 2012). Today, the distribution of malaria cases stratified by age is changing with an increase of malaria cases in older children (Kigozi et al., 2020; Touré et al., 2022), hence the need for IPTsc (Table 1). A study in Mali found progressively declining malaria transmission levels, in children younger than 5 years and an increase among the children older than 10 years incidence rate 0.3 (0.2–0.5) vs. 0.6 (0.5–0.7) respectively, p=0.016) (Coulibaly et al., 2021). Currently, in some areas, these age groups exhibit peak parasite prevalence in symptomatic infections and even higher parasite densities in asymptomatic malaria (Van Nguyen et al., 2012). These factors have been identified as important contributors to the infection reservoir for onward transmission. The substantial burden of malaria parasitemia in school-age children may adversely affect school performance and also lead to other deleterious consequences like anemia and cognitive impairment (Nankabirwa et al., 2014; Cohee et al., 2021). The epidemiological importance of older age groups may increase as elimination efforts intensify and transmission patterns change (Noor et al., 9930). These changes raise important technical, risk communication and operational challenges as traditional control interventions are inadequate or even inappropriate to effectively address the risk populations.

In 2020, pooled data from a systematic and meta-analysis by Cohee et al. (2020) from 13 trials conducted in 7 SSA countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Senegal, and Uganda) showed that IPTsc was associated with a 72% reduction in the prevalence of P falciparum infection (risk ratio (RR) 0.27: 95% CI 0.17–0.43). In this review, although one study with SP alone as the intervention drug did not show benefit (RR 1.05: 95% CI 0.84–1.30), all combination intervention drugs i.e. SP plus AS (RR 0.04: 95% CI 0.02–0.05); SP plus AQ (RR 0.09: 95% CI 0.05–0.16); DP (RR 0.21: 95% CI 0.16–0.28); AS plus AQ (RR 0.30: 95% CI 0.14–0.68); AL (RR 0.32: 95% CI 0.20–0.51) showed benefit.

The cognitive and academic benefits of IPTsc have been reported in; Kenya, where a mean increase in code transmission test score of 6·05 (95% CI 2.83–9.27; p=0.0007 and counting sounds test score of 1.80 (0.19–3.41; p=0.03), compared with controls was reported (Clarke et al., 2008), Mali, where an increase in sustained attention (difference +0.23, 95% CI 0.10–0.36, p<0.001 was reported (Thuilliez et al., 2010), and in a study in The Gambia, the intervention group had higher educational attainment by 0.52 grades (95% CI −0.041–1.089; p=0.069 than the controls (Jukes et al., 2006).

3.3.1 Acceptability and delivery of IPTsc

School enrollment in SSA has grown substantially, with nearly 200 million children attending primary and secondary school (Roser and Ortiz-Ospina). With many of these children harboring asymptomatic parasitemia, the school platform presents a unique opportunity for the implementation of malaria control interventions (Temperley et al., 2008). Acceptability has been evaluated in a few studies although not directly (World Health Organization, 2023b). In Uganda, 85% of children were willing to take anti malarial medication while at school (Nankabirwa et al., 2014) while in Malawi, a study that evaluated the addition of mass treatment for malaria to existing school-based programs showed that, 87% of children received IPTsc supporting the possibility of combining this intervention with ongoing health programs in schools (Cohee et al., 2018).

The WHO has established the Health Promoting School framework to promote health initiatives in schools, as they have been associated with better overall student health (Langford et al., 2014). A study conducted in 10 primary schools in rural Malawi showed that school-based health programs do not interfere with the teachers’ administrative and teaching activities. It was observed that 24.3% of teachers’ time was spent on non-teaching activities and this time could partly be converted to providing school-based health programs (Chinkhumba et al., 2022). Another study in Kenya also showed that school-based malaria control interventions were acceptable to the teachers and caretakers. However, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, there were mixed perceptions on IPTsc. Thus, although some school teachers and parents perceived IPTsc as an important intervention because it reduced malaria cases, there were concerns about adverse events (Matangila et al., 2017). Also, coverage may be impacted by low enrollment and absenteeism, poor access to diagnostics, and the number of doses (World Health Organization, 2023b). For example, in Kenya, it was observed that it was not feasible for schools to use artemether-lumefantrine which required six doses (Okello et al., 2012).

3.4 Post-discharge malaria chemoprevention

Severe anemia is one of the leading causes of hospital admissions among children in high malaria transmission settings and a major risk factor for childhood mortality (Phiri et al., 2008; Kiguli et al., 2015). Also, children hospitalized with severe anemia in Africa are at high risk of readmission or death within six months after discharge (Phiri et al., 2008). These observations have been summarized in a review of 27 studies in 10 countries in SSA (Kwambai et al., 2022). The analysis reported that mortality after discharge among children previously admitted with severe anemia was 2.69 times higher than in children previously admitted without severe anemia (RR 2.69: 95% CI 1.59–4.53; p<0.0001; I2 = 69.2%). The reasons for this difference are still not completely understood but malarial re-infection during the immediate post-discharge before hemoglobin recovery is a major contributing factor (Kwambai et al., 2022).

Post-discharge malaria chemoprevention (PDMC) (Table 1) is aimed at the prevention of new infections during the hemoglobin recovery period after hospital discharge when they are at high risk of re-admission or death (World Health Organization, 2023b). The WHO recommends that the length of the drug’s protective efficacy, the length of the transmission season, and the viability of administering each successive PDMC treatment should all be taken into consideration when determining how frequently PDMC is administered (World Health Organization, 2023b). The protective effect of PDMC has been shown in a systematic and meta-analysis by Phiri et al. (Phiri et al., 2024). In this analysis three double-blind, placebo-controlled trials from Malawi, Uganda, Kenya, and The Gambia. In this review, monthly sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, artemether-lumefantrine, or monthly dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine were administered to participants. PDMC was associated with a 77% reduction in mortality (RR 0.23: 95% CI 0.08–0.70, p=0.0094, I2 = 0%) and a 55% reduction in all-cause readmissions (HR 0.45: 95% CI 0.36–0.56, p<0.0001) compared with placebo. However, the protective effect was limited to the intervention period.

There is need to understand the protective effect of PDMC; beyond six months, in children with non-malarial anemia, in children with nutritional deficiencies, and the possibility of combining PDMC with malaria vaccination or other interventions such as single injections of monoclonal antibodies that have shown efficacies (Kayentao et al., 2022; Wells and Donini, 2022; Miura et al., 2024). There is also a need to understand whether the clinical outcomes measured in the studies do not differ in specific vulnerable groups of children e.g., children with sickle cell anemia and HIV.

3.4.1 Acceptability and delivery of PDMC

Post Discharge Malaria Chemoprevention being focused on a small and more targeted group, has high acceptability since the caretakers already have established a good relationship with the health workers and regard PDMC as a follow-up treatment for their children (Nkosi-Gondwe et al., 2018; Svege et al., 2018). In Malawi, a study by Nkosi-Gondwe et al. (2018) assessed the acceptability and delivery of PDMC using two approaches; community-based and facility-based delivery strategies. PDMC was highly accepted by the community. Furthermore, in the community-based delivery, caregivers received all courses of PDMC on discharge, whereas for facility-based delivery, the caregiver had to collect the PDMC drugs from a health facility every month. Community-based delivery was preferred by caregivers and was associated with higher adherence compared to facility-based strategies (community: 70.6% vs. facility: 52.0%, p=0.006). Another study conducted in five countries in SSA (Uganda, Nigeria, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda) showed that PDMC was perceived by key opinion leaders and decision-makers as a useful intervention that may have a positive effect on the whole healthcare system, from individual patients to the larger healthcare system (Audibert and Rietveld, 2024). Acceptability has been measured based on views from caretakers that participate in trials, hence there is a need to assess the acceptability of PDMC taking into consideration caretakers from the general population that are not part of clinical trials.

3.5 Malaria chemoprevention among children with human immunodeficiency virus and sickle cell anemia

Sickle cell anemia and HIV are still public health concerns in SSA (Reithinger et al., 2009). Malaria is one of the factors associated with high morbidity among children with SCA. Although people with sickle cell trait are protected against severe malaria, those with SCA have a higher risk of severe morbidity and mortality if hospitalized with malaria (Aduhene and Cordy, 2023). Thus, malaria chemoprevention is a standard of care for children with SCA, although this is not uniformly implemented. First, due to high levels of parasite resistance, regimens such as monthly SP used in most of eastern and southern Africa are not as effective and efficacy is further declining (Plowe, 2022). Secondly, adherence to daily (proguanil) or weekly (chloroquine) regimens is poor (Nkosi-Gondwe et al., 2023). Third, in some West African countries, the recommendations are unclear with some countries providing no chemoprevention (Nkosi-Gondwe et al., 2023). Also, there is no consensus on the best chemo-preventive therapy among children with SCA in SSA. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine has been proposed (Gutman et al., 2017) but there is a need to set up strategies to protect it from selection for resistance (Nkosi-Gondwe et al., 2023). Clearly, more studies are needed.

HIV-positive children may have a compromised immune system, which makes it more difficult for malaria parasites to be cleared from the body and raises the possibility of a higher incidence of complications and hospitalization (Mirzohreh et al., 2022). In this population, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis without malaria chemoprevention has been reported to lower the prevalence of malaria in children with HIV. However, a study conducted in Uganda reported a reduction in the incidence of malaria among children receiving the lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimen compred to those receiving the Non-Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors-based regimen (1.3 vs. 2.3 episodes per person-year; incidence-rate ratio, 0.6; 95% CI 0.36–0.97; p=0.04) (Achan et al., 2012). Further studies on the impact of antiretroviral therapy on malaria incidence are needed for conclusive policy advise.

3.5 Malaria vaccination

Vaccination is the intervention that has saved most lives in global health (World Health Organization, 2023b). The RTS, S/AS01 was the first recombinant protein malaria vaccine to be developed and to be given to children in regions with moderate to high P. falciparum malaria transmission. The second vaccine to be approved by WHO is the R21/MatrixM (Mahase, 2023). Both target the circumsporozoite protein of P. falciparum (RTS SCTP, 2015) (Table 1).

The RTS,S/AS01E advanced to a phase 3 trial from 2009 to 2014 in Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Ghana, Gabon, Burkina Faso, and Mozambique. The reported efficacy of the vaccine was 31.3% (97.5%CI 23.6–38.3%, p<0.0001) for infants and 55.8% (97.5% CI 50.6–60.4%, p<0.0001) in the 5 to 17 month age group (RTS SCTP, 2015). However, there were reported safety concerns such as the increased risk of febril seizures, meningitis and cerebral malaria. Regarding sustainbality of the protection, a 7 year trial conducted in Kenya and Tanzania, reported a deline in the vaccine efficacy from 35.9% (95% CI 8.1–55.3; p=0.02) in the first year to 3.6% (95% CI −29.5–28.2; p=0.81) in the seventh year (Olotu et al., 2016). In 2019, a trial to assess feasibility, safety, and impact of the RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine when implemented through national immunization programs was conducted in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi. This trial reported that the vaccine was associated with a 32% reduction (95% CI 5–51%) in hospital admission with severe malaria and a 9% reduction (95% CI 0–18%) in all-cause mortality (Asante et al., 2023) and there were no safety concerns as reported in phase 3 trials (RTS SCTP, 2015; Klein et al., 2016).

In a phase 3 trial of the R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine across five sites in four African countries (Burkina Faso, Mali, Kenya, Tanzania), the 12-month vaccine efficacy was 75% (95% CI 71–79; p<0·0001) at sites with seasonal transmission and 68% (Roser and Ortiz-Ospina; Jukes et al., 2006; Clarke et al., 2008; Phiri et al., 2008; Temperley et al., 2008; Thuilliez et al., 2010; Okello et al., 2012; Langford et al., 2014; Kiguli et al., 2015; Matangila et al., 2017; Cohee et al., 2018; Nkosi-Gondwe et al., 2018; Svege et al., 2018; Cohee et al., 2020; Chinkhumba et al., 2022; Kayentao et al., 2022; Kwambai et al., 2022; Wells and Donini, 2022; Phiri et al., 2024) at sites with perennial transimission (Datoo et al., 2024). The WHO recently approved the R21 vaccine for malaria prevention in children <2 years (Adepoju, 2023). Overall, the 12 months vaccine-efficacy of the primary 3 dose-R21 vaccine was 77% (Datoo et al., 2021), and this is sustained at 24 months if the children had a booster at 12 months (Datoo et al., 2022). The safety profile is good and most adverse events are mild (Datoo et al., 2021; Datoo et al., 2022). Several African countries are introducing the R21 vaccine in their national infant vaccination schedules. However, only children <2 years are targeted but in SCA, the malaria burden remains high into late adolescence implying that a substantial high-risk population will be left out. Even if recommended, the immunogenicity and efficacy of the vaccine in older children especially with prior exposure to malaria is unknown. Also, optimal delivery mechanisms in SCA remain unstudied.

3.5.1 Malaria chemoprevention in combination with malaria vaccination

Polymorphisms in the essential blood-stage antigens have made it difficult to create an effective vaccine against blood-stage malaria (Thera et al., 2011). Malaria chemoprevention medications to which the parasite is sensitive can quickly kill any blood-stage parasite, regardless of the parasite strain, and provide protection. Therefore, a well-targeted combination of malaria vaccine, monoclonal antibodies and chemoprevention may be crucial in the fight against malaria.

Malaria vaccination combined with a successful chemoprevention program could significantly reduce the malaria burden in the African Sahel and sub-Sahel regions. This impact was observed in a SMC trial in young children in Burkina Faso and Mali In this trial, the protective efficacy of the combination as compared to the vaccine alone was 59.6% (95% CI 54.7–64.0), against clinical malaria, 70.6% (95% CI 42.3–85.0) against hospital admission, and 75.3% (95% CI 12.5–93.0) against death from malaria (Chandramohan et al., 2021).

Similarly, monoclonal antibodies could potentially be combined with malaria vaccines and or malaria chemopreventions. In 2021, a study that used mouce models showed that administration of monoclonal antibodies in combination with R21 provided an enhanced protection against sporozoite challenge when compared to vaccine or mAbs alone (Wang et al., 2021).

3.5.2 Acceptability and delivery of the malaria vaccine

Vaccine uptake may be hampered by the delay in acceptance of a vaccine despite its availability (Vaccine hesitancy) (MacDonald, 2015). In Nigeria, 48.7% of the caretakers were initially not willing to have their children take the malaria vaccine (Abdulkadir and Ajayi, 2015), while in Kenya, acceptance of the malaria vaccine varied between areas of high transmission (98.9%) and 23% in areas with low seasonal transmission (Ojakaa et al., 2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of caregiver acceptance of the malaria vaccine among caretakers of under-five children in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) reported that malaria vaccine acceptance varied by; place of residence, tribe, age, sex, occupation, religion, and level of education. While concerns over vaccine safety, efficacy profile, vaccine’s requirement for multiple injections, and poor level of awareness were linked with vaccine hesitancy (Sulaiman et al., 2022). These studies show the need for tailored trainingon both levels of malaria transmission, levels of vaccine misconceptions, and social demographic factors.

Based on studies conducted in Mali, in countries with similar transmission intensity, the vaccines may be delivered in four different ways: age-based vaccination through EPI; seasonal vaccination through EPI mass vaccination campaigns (MVCs); a combination of age-based priming vaccination doses administered through EPI clinics and seasonal booster doses administered via MVCs (Jane et al., 2023). In certain communities, receiving too many doses may be viewed as an ‘overload’ because children already receive other vaccines (Runge et al., 2023), hence national malaria control programs may need to heavily invest in and sensitize the community before the planned rollouts of 2024.

5 Cost-effectiveness of malaria chemoprevention and vaccination strategies

Efficient use of resources in the health sector may be guided by economic evaluations, such as cost-effectiveness analyses or cost-utility analyses, which provide essential information to decide between treatment strategies and determine policy recommendations for malaria control (Ocan et al., 2019).

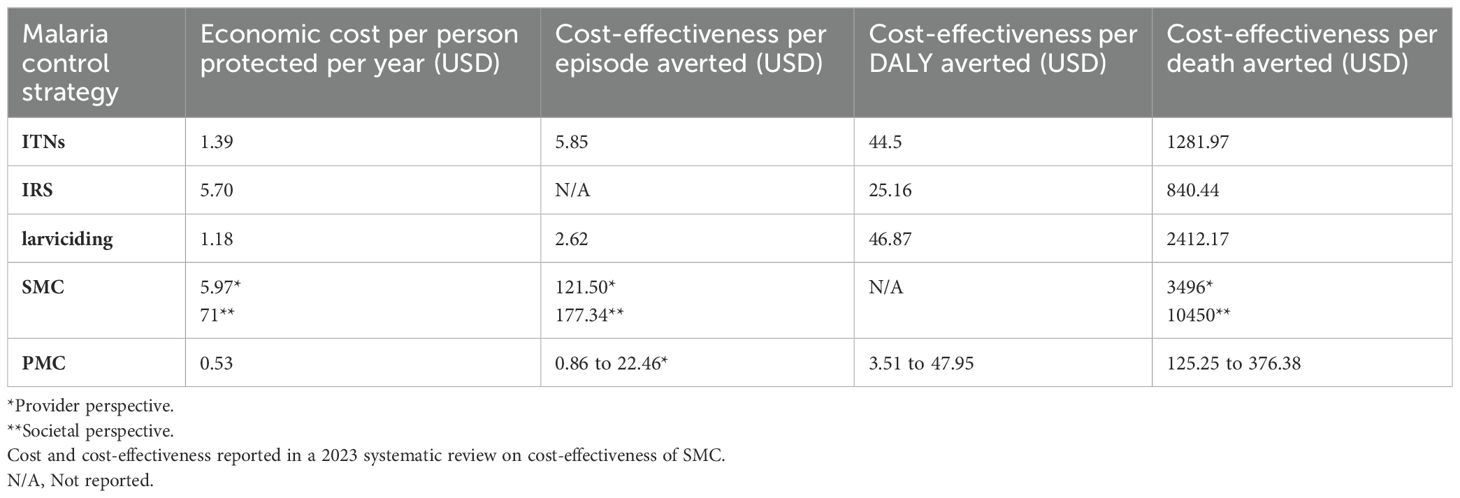

Overrall, chemoprevention strategies have been reported to be cost effective. The 2021 systematic literature review showed that PMC is more cost-effective compared to the other malaria control strategies i.e. versus SMC, Insectcide-Treated Nets (ITN), Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS), and larviciding. Table 2 In this review, the cost for the ITN was driven mainly by the cost of the nets, training, personnel, and transport. Cost for IRS and larviciding was driven by the cost of the insecticides, project management, and spray operations while SMC and PMC, costs were driven by training, supervision, and distribution of the medicines (Conteh et al., 2021). However, this cost-effectiveness study of malaria chemoprevention interventions (Conteh et al., 2021) did not include school-going children. Nonetheless, IPTsc has been described as a feasible and affordable strategy to address the burden of malaria in school children (Maccario et al., 2017). A study in Kenya confirmed this, estimating the annual cost for the delivery of IPT in schools at USD 1.88 per child and the cost per case of malaria parasitemia averted at USD 5.36 (Temperley et al., 2008), with drug and teacher training costs constituting the largest cost components.

Three months of PDMC in Kenya, Uganda, and Malawi was found to be cost-effective, compared to the standard of care (2-week anti-malarial regimen at discharge). Moreover, different delivery strategies of PDMC were compared. The community-based delivery strategy was cost-effective compared to repeated distribution of monthly doses at the hospital (facility delivery). Assuming a societal perspective, that is combining the households’ and the facilities’ costs, the cost of community-based PDMC per child treated in Malawi, Kenya, and Uganda was reduced on average by 49%, 50%, and 47%, respectively, compared to the standard of care. Facility-delivered PDMC incurred a smaller reduction of cost by an average of 31%, 35%, and 27%. The savings were mainly driven by the reduced costs of fewer readmissions, and, in addition, a need of blood transfusions per readmission (Kühl et al., 2022).

RTS, S has been predicted to be highly cost-effective in areas in SSA with moderate-to-high malaria transmission (Reithinger et al., 2009), especially in areas where there is high existing ITN usage, high SMC coverage, and where the level of malaria transmission is high (Topazian et al., 2023). The estimates of public health impact and cost-effectiveness vary depending on the level of malaria transmission and the use of other vector control strategies. One study found that RTS, S/AS01 was the most cost-effective strategy at a cost of less than 9.30 USD per dose and this led to significant case reductions, with a median of 2,653 (range: 1,741 to 3,966) per 100,000 people and 82,270 (range: 54,034 to 123,105) cases averted per 100,000 fully vaccinated children. In another modeling study, RTS, S/AS01 was predicted to prevent a median of 93,940 (20,490–126,540) clinical cases and 394 (127–708) deaths for the four-dose schedule cost of 5 USD per dose, per 100 000 fully vaccinated children (Topazian et al., 2023). About the integration of the malaria vaccine within EPI programs, a study in Malawi showed that this approach is cost-effective compared to the use of chemoprevention. In this study, the vaccine was found to have an ICER of USD 115 and 109 per DALY averted from the perspectives of the health system and society, respectively, compared to no vaccination (Ndeketa et al., 2021).

6 Challenges to the implementation of malaria chemoprevention and vaccines strategies

Parental and community acceptability is important for the successful implementation and sustainability of both the malaria chemoprevention and vaccine strategies. Factors that may influence acceptability include community perceptions of the intervention, mistrust in the healthcare providers, fear of adverse events, and the availability and accessibility of drugs (Staedke et al., 2018). Malaria chemoprevention and vaccination require a regular supply of drugs, and the unavailability of these drugs can be a barrier to the implementation of malaria control strategies. Ensuring a consistent supply and distribution of the drugs is key to the success of the program.

A study conducted in Benin, Madagascar and Senegal, showed that PMC was well accepted by both health workers and the community (Pool et al., 2008). Involving community members in the design and implementation programs may increase understanding of the intervention and its benefits and help address any concerns or misconceptions among community members. Regarding implementation of IPTsc. Other negative perceptions of IPTsc included fear that the drugs may affect the children’s memory and cognitive functions (Okello et al., 2012). There is need for community sensitizations and education regarding IPTsc. The information on the effects of asymptomatic parasitemia is required to reinforce understanding of the effects on schoolchildren’s health and education, as a lack of information may jeopardize seemingly healthy children’s complete adherence to treatment (Okello et al., 2012).

Other challenges such as poor adherence when the intervention is administered at home (Thwing et al., 2024) or mis-understanding of chemoprevention as a replacement for of immunization (Owen et al., 2022) may affect the uptake of immunization and should be taken note of. Like PMC, adherence to SMC medications is high when the first dose is given under observation by the health workers. However, the levels of adherence decline with the second and third doses (Chatio et al., 2019). Understanding and addressing the factors that lead to this reduction in adherence is needed.

To date, the major challenges faced by SMC implementation are mainly due to mobile populations such as the nomads in the Sahel region (Moukénet et al., 2022). These populations should receive chemoprevention both within or outside their usual place of residence but many times, they are missed in SMC census (Azoukalné et al., 2021). Increased coverage could be achieved through the integration of the nomad immunization clinics with the SMC services (Moukénet et al., 2022). High coverage however comes with challenges such as insufficient medicines and ensuring that medicines left with the mothers are used exclusively for SMC and in specific individuals. Lessons learned from the use of already existing drug delivery mechanisms such as EPI platforms could be leveraged (Greenwood, 2006). Other challenges include poor means of transportation and communication, and limited points of delivery (Pitt et al., 2012; Antwi et al., 2016).

Coverage is one of the factors that determine the effectiveness of the malaria service delivery (Shengelia et al., 2005; Karim, 2023). A study in the Kambia district, Sierra Leone, reported that the scale-up of PMC was not done smoothly because of the the gaps between IPTi and childhood vaccine coverage (Lahuerta et al., 2021). In addition, supply chain determinants such as availability of the antimalarial agents and malaria vaccines, and the infiltration of substandard and falsified antimalarial medication into the malaria endemic region (Newton et al., 2011; Karunamoorthi, 2014) affect the implementation of the strategies. WHO has reported a problem with drug quality in public and nongovernmental organization (NGO) distribution chains (Renschler et al., 2015). Falsified AL with labels resembling those on the quality-approved ACTs from the Global Fund/Affordable Medicines Facility (AMFm) were discovered to be widely distributed in Cameroon (World Health Organization, 2013). Even when the drugs meet the required standards, their quality may be compromised by the process of transportation especially medicines that require maintenance of specific temperature ranges (Renschler et al., 2015). However, this may not be the case where the chemoprevention and vaccination mass campaign programs are run by National Malaria Programs.

Chemoprevention strategies in children are delivered through different approaches which may influence the extent of adherence to the antimalarial agents by the caretakers. The PMC, for example, is delivered through EPI programs, while IPTsc is delivered through school schedules. Many of the studies on adherence depend on pill counts or self-reporting. However, self-reports have been associated with recall bias and overestimation of adherence (Somé et al., 2022). According to a study comparing several malaria prevention methods on children in Uganda, caregiver reports of adherence to a 3-day course of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine was higher (>100%) than drug concentration measures (52%) (Bigira et al., 2014). In Niger, a study that evaluated adherence in young children receiving SP plus AQ in an SMC environment found that only about 20% of children had complete adherence. Therefore, there is a need for more studies to assess adherence to malaria chemoprevention for PMC, SMC, IPTsc, and PDMC based on plasma concentrations respectively, and sensitization since poor adherence has been attributed to caretakers forgetting to give medicines to children or keeping the medicines for future use (Gysels et al., 2009). At the clinics, gender has been said to play a role in non-adherence as males considered this a role for the women (Gysels et al., 2009). The possibility of providing directly observed therapy to increase adherence to malaria chemoprevention in children needs to be explored. Poor medication adherence can potentially lead to selection for resistance.

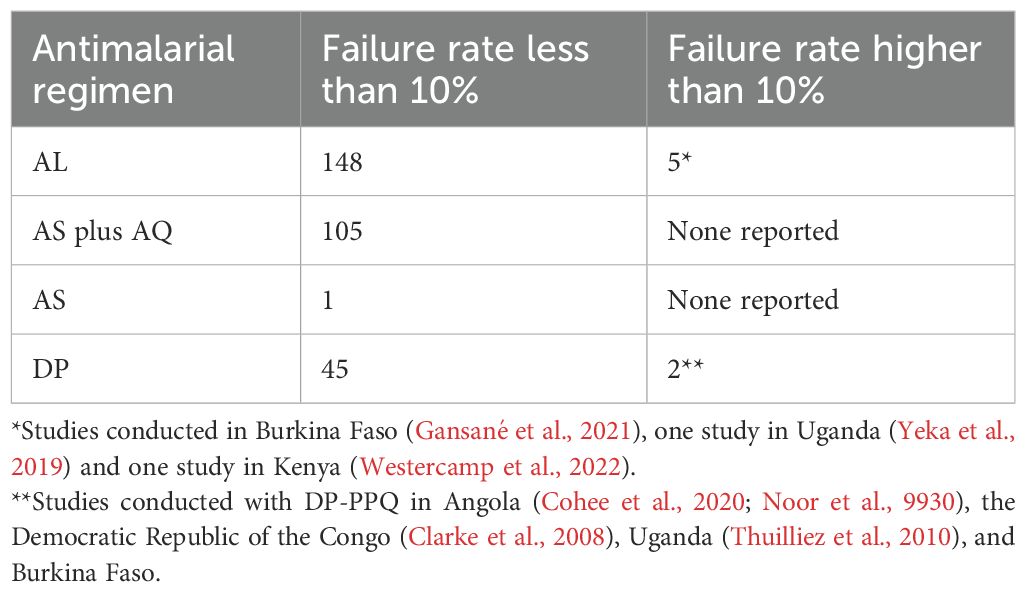

Plasmodium falciparum has gained resistance to most antimalarial drugs either through genomic changes or through non specific stress response based survival mechanisms like the ring stage temporary growth arrest phenomenon (Platon and Ménard, 2024). This phenomenon was reported in 2011 where parasite development was abruptly arrested following a single exposure to DP, with some parasites being dormant for up to 20 days (Teuscher et al., 2010). Malaria chemoprevention influences resistance not just in terms of the percentage of infections that harbor resistant parasites but also in terms of the percentage of persons that contract this kind of infection. In the WHO African Region, some studies have shown higher levels of treatment failure (World Health Organization, 2023c). This is observed in the 2020 WHO global data report on antimalarial drug efficacy and resistance (World Health Organization, 2019) (Table 3).

One major threat to the global endeavor to reduce the burden of malaria is the emergence of resistance to artemisinins and their partner drugs. Four countries in the WHO African region i.e. Eritrea (Mihreteab et al., 2023) and Ethiopia (Fola et al., 2023); parasites harboring both R622I and Pfhrp2/3 deletions; Rwanda; R561H mutations (Uwimana et al., 2020; Straimer et al., 2022); Uganda; 675V, 469F, 561H, 441L, mutations (Asua et al., 2021; Conrad et al., 2023) have been reported. Between 2005 and 2011, the use of PMC was classified based on an analysis of molecular marker data collected throughout. From this analysis, based on a 50% threshold for K540E prevalence, the classification showed that 14 Central and West African countries were suitable for SP, seven countries could not be classified due to a lack of current data, and eight East African countries were unsuitable (Naidoo and Roper, 2011). A study evaluating the cost-effectiveness of chemoprevention in infants and children noted that PMC was cost-effective across all levels of resistance, however, the analysis did not take into account the high-level resistance provided by dhps K540E, A581G, and A613S/T, restricting the study’s applicability to regions where these mutations are common (Ross et al., 2011).

Implementation of the vaccines in Africa has encountered challenges such as a lack of functioning cold chain equipment, vaccine hesitancy which is fueled by miscommunication and misconceptions about vaccines, and vaccine schedules not aligned with the existing EPI programs (Moree and Ewart, 2004; Kummervold et al., 2017). In Ghana, implementation of the malaria vaccine strategy was hampered by the lack of proper sensitization programs. There were community misconceptions through social media where communities were made to believe that the implementation of the malaria vaccine is similar to the Ebola vaccine controversy where it was believed that the Ebola vaccine was a secret trial aimed at introducing Ebola into the communities (Kummervold et al., 2017). Furthermore, the implementation of malaria vaccines is affected by inadequate funding for vaccine acquisition in certain African countries, poor administration follow-up, and the withdrawal of financial support from private institutions (Okesanya et al., 2024). In 2021, WHO reported that GlaxoSmithKline’s limited supply of the four-dose Mosquirix vaccine cannot adequately protect millions of African children until 2028, as GSK can only produce approximately 15 million doses annually (World Health Organization, 2021; Mumtaz et al., 2023).

In 2018, a systematic review reported that the potential challenges to the implementation of malaria vaccine programs in SSA. These included; inadequate community engagement resulting from the lack of information about the vaccine, fear of the vaccine’s side effects, inefficient delivery of the child immunization services, lack of health supplies at hospitals, unresponsive hospital staff, and the poor communication between hospital staff and patients, the reduction in attendance of clinics after nine months, the fear of the partial protection provided by the vaccines, difficulties with storage of the vaccines, and the socio-cultural practices and religious denominations against vaccination (Dimala et al., 2018).

7 Discussion

The different chemoprevention and vaccine strategies in children presented in this review are all effective in reducing the incidence of malaria. However, their effectiveness varies in different settings (World Health Organization, 2023b). This could be due to drug resistance, poor adherence or uptake, stockouts or irregular supply of medicines, and community attitudes. The variation in the effectiveness points to the need for deployment of combined strategies to enhance malaria control. Additionaly there is need to continue investing on innovative approaches for delivery mechanisms and real-time monitoring of their impact on malaria burden and hence guide implementation of the strategies.

The operational feasibility of combining deployment of malaria vaccines with chemoprevention in real-life settings is yet to be established. Some potential approaches could include co-deployment of malaria vaccine alongside SMC at the start of the malaria transmission season as reported in the study by Chandramohan et al. (Klein et al., 2016) in Burkina Faso and Mali. Also, incorporation of malaria vaccines into childhood immunization programs through the EPI systems could be adopted by all national malaria programs rolling out the vaccines (Adepoju, 2019). Additionally, developing vaccines that target multiple stages of the malaria life cycle could potentially lead to enhanced efficacy. A study by Sherrard-Smith et al. (2018) demonstrated that a combined efficacy in the pre-erythrocytic vaccines plus the transmission-blocking vaccines antibody group was higher than the estimated efficacy if the two antibodies acted independently. In addition, monoclonal antibodies could potentially be used to reduce the malaria burden in high-risk populations such as children with sickle cell anemia, and pregnant women. A phase 2 trial conducted in Mali showed that the efficacy of a monoclonal antibody, L9LS against Plasmodium falciparum infection (Kayentao et al., 2024).

On the other hand, malaria control interventions are largely impacted by the health system and the training and retention, identifying and granting access to eligible children, guaranteeing medicine supply availability, and accurate dosing (Pitt et al., 2012; Compaoré et al., 2017; Bicaba et al., 2020). For example, the implementation of chemoprevention is affected by the lack of training and supervisory visits limited by resource availability (Kombate et al., 2019; Okereke et al., 2023). These challenges may be mitigated by creating online systems that report real-time stock-outs like in a study in Kenya, that piloted a mobile phone text messaging program to report real-time stock data for SMC commodities (Githinji et al., 2013). To improve community uptake, door-to-door distribution techniques can be included in the chemoprevention initiatives (Gatiba et al., 2023). The high coverage of chemoprevention through door-to-door distribution indicates that community health workers may effectively reach many infants and children in hard-to-reach areas, hence addressing the equity gap.

Antimalaria drug resistance poses a threat to malaria control and elimination efforts in endemic countries. This review highlights the need for continuous updating of the guidelines and tools in the fight against malaria. Management of antimalarial resistance will require tools to effectively detect and monitor both genotypic and phenotypic parasite resistance (Jacob et al., 2021). The WHO recommends the adoption of the antimalarial therapeutic efficacy protocol for surveillance in endemic regions (World Health, 2018).

The population at risk of malaria is larger than the available number of vaccine donations in SSA (Okesanya et al., 2024). By 2026, the world’s annual demand for malaria vaccines is projected to reach 40–60 million doses increasing to 80–100 million doses by 2030 (World Health Organization, 2023d). Currently, 12 countries in Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Niger, Sierra Leone, and Uganda) have been allocated a total of 18 million doses of RTS, S/AS01 vaccine for 2023–2025 period (World Health Organization, 2023a). This is far below the population at risk of malaria in SSA which currently stands at 233 million cases. This gives a total deficit of 200 million doses, potentially impeding progress to malaria elimination. It is therefore key that governments in malaria-endemic countries of SSA find alternative sources of funding for the malaria vaccine to ensure uninterrupted supply and wider coverage. For example, the Abuja declaration calls for countries to allocate ≥ 15% of their annual budget to improve the health sector (African Union). In addition, a functional guide or framework may be necessary to steer nations in SSA through the procedures involved in equitably incorporating the malaria vaccine into their national immunization campaigns and utilizing it with other preventive measures such as bed nets and chemoprevention (El-Moamly and El-Sweify, 2023).

8 Conclusion

Despite the deployment of various interventions including vector control, chemoprevention, and vaccination malaria persists in most of SSA pausing a threat to the global target of malaria elimination by 2030. This therefore calls for the need to strengthen real-time monitoring of the different interventions and use of context specific evidence to inform the development of innovative implementation strategies. Additionally, there is a need for continued investment in the search for alternative approaches to malaria elimination in SSA.

Author contributions

WN: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MO: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BR: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RI: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work is supported through a grant from the Research Council of Norway, Global Health and Vaccination Research (GLOBVAC) program, Grant No. 285284.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdulkadir B. I., Ajayi I. O. (2015). Willingness to accept malaria vaccine among caregivers of under-5 children in Ibadan North Local Government Area, Nigeria. MalariaWorld. J. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10870005

Achan J., Kakuru A., Ikilezi G., Ruel T., Clark T. D., Nsanzabana C., et al. (2012). Antiretroviral agents and prevention of malaria in HIV-infected Ugandan children. New Engl. J. Med. 367, 2110–2118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200501

Adepoju P. (2019). RTS, S malaria vaccine pilots in three African countries. Lancet 393, 1685. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30937-7

Adepoju P. (2023). Malaria community welcomes WHO vaccine approval. Lancet 402, 1316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02276-6

Aduhene E., Cordy R. J. (2023). Sickle cell trait enhances malaria transmission. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 1609–1610. doi: 10.1038/s41564-023-01450-7

African Union 2001 Abuja declaration 2003. Available online at: https://au.int/en/file/32894-file-2001-abuja-declarationpdf (Accessed February 19).

Aleshnick M., Florez-Cuadros M., Martinson T., Wilder B. K. (2022). Monoclonal antibodies for malaria prevention. Mol. Ther. 1810–1821 doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.04.001

Amimo F., Lambert B., Magit A., Sacarlal J., Hashizume M., Shibuya K. (2020). Plasmodium falciparum resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in Africa: a systematic analysis of national trends. BMJ Global Health 5, e003217. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003217

Antwi G. D., Bates L. A., King R., Mahama P. R., Tagbor H., Cairns M., et al. (2016). Facilitators and barriers to uptake of an extended seasonal malaria chemoprevention programme in Ghana: a qualitative study of caregivers and community health workers. PloS One 11, e0166951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166951

Arya A., Kojom Foko L. P., Chaudhry S., Sharma A., Singh V. (2021). Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) and drug resistance molecular markers: A systematic review of clinical studies from two malaria endemic regions – India and sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs Drug Resist. 15, 43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2020.11.006

Asante K. P., Mathanga D. P., Milligan P., Akech S., Oduro A. R., Mwapasa V., et al. (2023). Feasibility, safety, and impact of the RTS, S/AS01 E malaria vaccine when implemented through national immunisation programmes: evaluation of cluster-randomized introduction of the vaccine in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi, 1660–1670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00004-7

Ashley E. A., Yeka A. (2020). Seasonal malaria chemoprevention: closing the know–do gap. Lancet 396, 1778–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32525-3

Asua V., Conrad M. D., Aydemir O., Duvalsaint M., Legac J., Duarte E., et al. (2021). Changing prevalence of potential mediators of aminoquinoline, antifolate, and artemisinin resistance across Uganda. J. Infect. Dis. 223, 985–994. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa687

Audibert C., Rietveld H. (2024). Perceived barriers and opportunities for the introduction of post-discharge malaria chemoprevention (PDMC) in five sub-Saharan countries: a qualitative survey amongst malaria key stakeholders. Malar. J. 23, 270. doi: 10.1186/s12936-024-05100-z

Audibert C., Tchouatieu A. M. (2021). Perception of malaria chemoprevention interventions in infants and children in eight sub-saharan african countries: an end user perspective study. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 6. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed6020075

Azoukalné M., Laura D., Zana C., Djiddi Ali S., Charlotte W. (2021). Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) in Chad: understanding barriers to delivery of SMC and feasibility and acceptability of extending to 5–10 year old children in Massaguet district. Ndjamena.: Malaria Consortium. 57. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04074-0

Balikagala B., Fukuda N., Ikeda M., Katuro O. T., Tachibana S.-I., Yamauchi M., et al. (2021). Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in Africa. New Engl. J. Med. 385, 1163–1171. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101746

Barry A., Issiaka D., Traore T., Mahamar A., Diarra B., Sagara I., et al. (2018). Optimal mode for delivery of seasonal malaria chemoprevention in Ouelessebougou, Mali: a cluster randomized trial. PloS One 13, e0193296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193296

Bazie V. B., Ouattara A. K., Sagna T., Compaore T. R., Soubeiga S. T., Sorgho P. A., et al. (2020). Resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine (Dhfr and Dhps) and artemisinin and its derivatives (K13): a major challenge for malaria elimination in West Africa. J. Biosci. Medicines 8, 82. doi: 10.4236/jbm.2020.82007

Bhatt S., Weiss D., Cameron E., Bisanzio D., Mappin B., Dalrymple U., et al. (2015). The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526, 207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature15535

Bicaba A., Serme L., Chetaille G., Kombate G., Bila A., Haddad S. (2020). Longitudinal analysis of the capacities of community health workers mobilized for seasonal malaria chemoprevention in Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 19, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03191-y

Bigira V., Kapisi J., Clark T. D., Kinara S., Mwangwa F., Muhindo M. K., et al. (2014). Protective efficacy and safety of three antimalarial regimens for the prevention of malaria in young Ugandan children: a randomized controlled trial. PloS Med. 11, e1001689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001689

Bojang K. A., Akor F., Conteh L., Webb E., Bittaye O., Conway D. J., et al. (2011). Two strategies for the delivery of IPTc in an area of seasonal malaria transmission in the Gambia: a randomised controlled trial. PloS Med. 8, e1000409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000409

Chandramohan D., Zongo I., Sagara I., Cairns M., Yerbanga R.-S., Diarra M., et al. (2021). Seasonal malaria vaccination with or without seasonal malaria chemoprevention. New Engl. J. Med. 385, 1005–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026330

Chatio S., Ansah N. A., Awuni D. A., Oduro A., Ansah P. O. (2019). Community acceptability of Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention of morbidity and mortality in young children: A qualitative study in the Upper West Region of Ghana. PloS One 14, e0216486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216486

Chinkhumba J., Kadzinje V., Jenda G., Kayange M., Mathanga D. P. (2022). Impact of school-based malaria intervention on primary school teachers’ time in Malawi: evidence from a time and motion study. Malar. J. 21, 301. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04324-1

Clarke S. E., Jukes M. C., Njagi J. K., Khasakhala L., Cundill B., Otido J., et al. (2008). Effect of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria on health and education in schoolchildren: a cluster-randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 372, 127–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61034-X

Cohee L. M., Chilombe M., Ngwira A., Jemu S. K., Mathanga D. P., Laufer M. K. (2018). Pilot study of the addition of mass treatment for malaria to existing school-based programs to treat neglected tropical diseases. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98, 95–99. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0590

Cohee L. M., Nankabirwa J. I., Greenwood B., Djimde A., Mathanga D. P. (2021). Time for malaria control in school-age children. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 5, 537–538. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00158-9

Cohee L. M., Opondo C., Clarke S. E., Halliday K. E., Cano J., Shipper A. G., et al. (2020). Preventive malaria treatment among school-aged children in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Lancet Global Health 8, e1499–ee511. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30325-9

Compaoré R., Yameogo M. W. E., Millogo T., Tougri H., Kouanda S. (2017). Evaluation of the implementation fidelity of the seasonal malaria chemoprevention intervention in Kaya health district, Burkina Faso. PloS One 12, e0187460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187460

Conrad M. D., Asua V., Garg S., Giesbrecht D., Niaré K., Smith S., et al. (2023). Evolution of partial resistance to artemisinins in malaria parasites in Uganda. New Engl. J. Med. 389, 722–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa22118

Conteh L., Shuford K., Agboraw E., Kont M., Kolaczinski J., Patouillard E. (2021). Costs and cost-effectiveness of malaria control interventions: a systematic literature review. Value. Health 24, 1213–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.01.013

Coulibaly D., Guindo B., Niangaly A., Maiga F., Konate S., Kodio A., et al. (2021). A decline and age shift in malaria incidence in rural Mali following implementation of seasonal malaria chemoprevention and indoor residual spraying. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene. 104, 1342. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0622

Cruz V. O., Walt G. (2013). Brokering the boundary between science and advocacy: the case of intermittent preventive treatment among infants. Health Policy Plann. 28, 616–625. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs101

Datoo M. S., Dicko A., Tinto H., Ouédraogo J.-B., Hamaluba M., Olotu A., et al. (2024). Safety and efficacy of malaria vaccine candidate R21/Matrix-M in African children: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 403, 533–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02511-4

Datoo M. S., Natama H. M., Somé A., Bellamy D., Traoré O., Rouamba T., et al. (2022). Efficacy and immunogenicity of R21/Matrix-M vaccine against clinical malaria after 2 years’ follow-up in children in Burkina Faso: a phase 1/2b randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00442-X

Datoo M. S., Natama M. H., Somé A., Traoré O., Rouamba T., Bellamy D., et al. (2021). Efficacy of a low-dose candidate malaria vaccine, R21 in adjuvant Matrix-M, with seasonal administration to children in Burkina Faso: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 397, 1809–1818. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00943-0

De Sousa A., Rabarijaona L. P., Ndiaye J. L., Sow D., Ndyiae M., Hassan J., et al. (2012). Acceptability of coupling Intermittent Preventive Treatment in infants with the Expanded Programme on Immunization in three francophone countries in Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health 17, 308–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02915.x

Dimala C. A., Kika B. T., Kadia B. M., Blencowe H. (2018). Current challenges and proposed solutions to the effective implementation of the RTS, S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine Program in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PloS One 13, e0209744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209744

El-Moamly A. A., El-Sweify M. A. (2023). Malaria vaccines: the 60-year journey of hope and final success—lessons learned and future prospects. Trop. Med. Health 51, 29. doi: 10.1186/s41182-023-00516-w

Esu E. B., Oringanje C., Meremikwu M. M. (2021). Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7. doi: 10.1002/14651858

Figueroa-Romero A., Bissombolo D., Meremikwu M., Ratsimbasoa A., Sacoor C., Arikpo I., et al. (2023). Prevalence of molecular markers of resistance to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine before and after community delivery of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country evaluation. Lancet Global Health 11, e1765–e1e74. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00414-X

Fola A. A., Feleke S. M., Mohammed H., Brhane B. G., Hennelly C. M., Assefa A., et al. (2023). Plasmodium falciparum resistant to artemisinin and diagnostics have emerged in Ethiopia. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 1911–1919. doi: 10.1038/s41564-023-01461-4

Gansané A., Moriarty L. F., Ménard D., Yerbanga I., Ouedraogo E., Sondo P., et al. (2021). Anti-malarial efficacy and resistance monitoring of artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine shows inadequate efficacy in children in Burkina Faso, 2017–2018. Malar. J. 20, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03585-6

Gatiba P., Laury J., Steinhardt L., Hwang J., Thwing J. I., Zulliger R., et al. (2023). Contextual factors to improve implementation of malaria chemoprevention in children: A systematic review. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.23-0478. tpmd230478-tpmd.

Githinji S., Kigen S., Memusi D., Nyandigisi A., Mbithi A. M., Wamari A., et al. (2013). Reducing stock-outs of life saving malaria commodities using mobile phone text-messaging: SMS for life study in Kenya. PloS One 8, e54066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054066

Greenwood B. (2006). Intermittent preventive treatment–a new approach to the prevention of malaria in children in areas with seasonal malaria transmission. Trop. Med. Int. Health 11, 983–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01657.x

Gutman J., Kovacs S., Dorsey G., Stergachis A., Ter Kuile F. O. (2017). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of repeated doses of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for prevention and treatment of malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, 184–193. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30378-4

Gysels M., Pell C., Mathanga D. P., Adongo P., Odhiambo F., Gosling R., et al. (2009). Community response to intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in infants (IPTi) delivered through the expanded programme of immunization in five African settings. Malar. J. 8, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-191

Jacob C. G., Thuy-Nhien N., Mayxay M., Maude R. J., Quang H. H., Hongvanthong B., et al. (2021). Genetic surveillance in the Greater Mekong subregion and South Asia to support malaria control and elimination. eLife 10, e62997. doi: 10.7554/eLife.62997

Jane G., Halimatou D., Seydou T., Fatoumata K., Jessica M., Issaka S., et al. (2023). Delivery strategies for malaria vaccination in areas with seasonal malaria transmission. BMJ Global Health 8, e011838. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-011838

Jones S. (2023). How genetically modified mosquitoes could eradicate malaria. Nature 618, 29–31. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-02051-4

Jukes M. C. H., Pinder M., Grigorenko E. L., Smith H. B., Walraven G., Bariau E. M., et al. (2006). Long-term impact of malaria chemoprophylaxis on cognitive abilities and educational attainment: follow-up of a controlled trial. PloS Clin. Trials 1, e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010019

Kajubi R., Ainsworth J., Baker K., Richardson S., Bonnington C., Rassi C., et al. (2023). A hybrid effectiveness-implementation study protocol to assess the effectiveness and chemoprevention efficacy of implementing seasonal malaria chemoprevention in five districts in Karamoja region, Uganda. Gates. Open Res. 7, 14. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.14287.2

Karim A.d. (2023). Effective coverage in health systems: evolution of a concept. Diseases 11, 35. doi: 10.3390/diseases11010035

Karunamoorthi K. (2014). The counterfeit anti-malarial is a crime against humanity: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Malar. J. 13, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-209

Kayentao K., Ongoiba A., Preston A. C., Healy S. A., Doumbo S., Doumtabe D., et al. (2022). Safety and efficacy of a monoclonal antibody against malaria in Mali. New Engl. J. Med. 387, 1833–1842. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206966

Kayentao K., Ongoiba A., Preston A. C., Healy S. A., Hu Z., Skinner J., et al. (2024). Subcutaneous administration of a monoclonal antibody to prevent malaria. New Engl. J. Med. 390, 1549–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2312775

Kigozi S. P., Kigozi R. N., Epstein A., Mpimbaza A., Sserwanga A., Yeka A., et al. (2020). Rapid shifts in the age-specific burden of malaria following successful control interventions in four regions of Uganda. Malar. J. 19, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03196-7

Kiguli S., Maitland K., George E. C., Olupot-Olupot P., Opoka R. O., Engoru C., et al. (2015). Anaemia and blood transfusion in African children presenting to hospital with severe febrile illness. BMC Med. 13, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0246-7

Klein S. L., Shann F., Moss W. J., Benn C. S., Aaby P. (2016). RTS,S malaria vaccine and increased mortality in girls. mBio 7, e00514–e00516. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00514-16

Kobbe R., Kreuzberg C., Adjei S., Thompson B., Langefeld I., Thompson P. A., et al. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of extended intermittent preventive antimalarial treatment in infants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45, 16–25. doi: 10.1086/518575

Koko V. S., Warsame M., Vonhm B., Jeuronlon M. K., Menard D., Ma L., et al. (2022). Artesunate–amodiaquine and artemether–lumefantrine for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Liberia: in vivo efficacy and frequency of molecular markers. Malar. J. 21, 134. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04140-7

Kombate G., Guiella G., Baya B., Serme L., Bila A., Haddad S., et al. (2019). Analysis of the quality of seasonal malaria chemoprevention provided by community health Workers in Boulsa health district, Burkina Faso. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4299-3

Kühl M.-J., Gondwe T., Dhabangi A., Kwambai T. K., Mori A. T., Opoka R., et al. (2022). Economic evaluation of postdischarge malaria chemoprevention in preschool children treated for severe anaemia in Malawi, Kenya, and Uganda: A cost-effectiveness analysis. EClinicalMedicine 52. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101669

Kummervold P. E., Schulz W. S., Smout E., Fernandez-Luque L., Larson H. J. (2017). Controversial Ebola vaccine trials in Ghana: a thematic analysis of critiques and rebuttals in digital news. BMC Public Health 17, 642. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4618-8

Kwambai T. K., Mori A. T., Nevitt S., van Eijk A. M., Samuels A. M., Robberstad B., et al. (2022). Post-discharge morbidity and mortality in children admitted with severe anaemia and other health conditions in malaria-endemic settings in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 6, 474–483. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00074-8

Lahuerta M., Sutton R., Mansaray A., Eleeza O., Gleason B., Akinjeji A., et al. (2021). Evaluation of health system readiness and coverage of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in infants (IPTi) in Kambia district to inform national scale-up in Sierra Leone. Malar. J. 20, 74. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03615-3

Langford R., Bonell C. P., Jones H. E., Pouliou T., Murphy S. M., Waters E., et al. (2014). The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2

Looman L., Pell C. (2021). End-user perspectives on preventive antimalarials: a review of qualitative research. Global Public Health, 753–767. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1888388

Maccario R., Rouhani S., Drake T., Nagy A., Bamadio M., Diarra S., et al. (2017). Cost analysis of a school-based comprehensive malaria program in primary schools in Sikasso region, Mali. BMC Public Health 17, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4490-6

MacDonald N. E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 33, 4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

Mahase E. (2023). WHO recommends second vaccine for malaria prevention in children (British Medical Journal Publishing Group) BMJ 383, p2291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p2291

Malaria Consortium. (2022). Insights from implementing the first seasonal malaria chemoprevention campaign in Mozambique. (London: Malaria Consortium).

Matangila J. R., Fraeyman J., Kambulu M.-L. M., Mpanya A., da Luz R. I., Lutumba P., et al. (2017). The perception of parents and teachers about intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in school children in a semi-rural area of Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar. J. 16, 19. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1670-2

Mihreteab S., Platon L., Berhane A., Stokes B. H., Warsame M., Campagne P., et al. (2023). Increasing prevalence of artemisinin-resistant HRP2-negative malaria in Eritrea. New Engl. J. Med. 389, 1191–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2210956

Mirzohreh S.-T., Safarpour H., Pagheh A. S., Bangoura B., Barac A., Ahmadpour E. (2022). Malaria prevalence in HIV-positive children, pregnant women, and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites Vectors. 15, 324. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05432-2

Miura K., Flores-Garcia Y., Long Carole A., Zavala F. (2024). Vaccines and monoclonal antibodies: new tools for malaria control. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 37, e00071–e00023. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00071-23

Moree M., Ewart S. (2004). Policy challenges in malaria vaccine introduction. The Intolerable Burden of Malaria II: What’s New, What’s Needed: Supplement to Volume 71 (2) of the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. (Seattle, Washington: Malaria Vaccine Initiative, Program for Appropriate Technology in Health)

Moukénet A., Honoré B., Smith H., Moundiné K., Djonkamla W.-M., Richardson S., et al. (2022). Knowledge and social beliefs of malaria and prevention strategies among itinerant Nomadic Arabs, Fulanis and Dagazada groups in Chad: a mixed method study. Malar. J. 21, 56. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04074-0

Mumtaz H., Nadeem A., Bilal W., Ansar F., Saleem S., Khan Q. A., et al. (2023). Acceptance, availability, and feasibility of RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine: a review. Immunity. Inflammation Dis. 11, e899. doi: 10.1002/iid3.899

Naidoo I., Roper C. (2011). Drug resistance maps to guide intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in African infants. Parasitology 138, 1469–1479. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000746

Nankabirwa J., Brooker S. J., Clarke S. E., Fernando D., Gitonga C. W., Schellenberg D., et al. (2014). Malaria in school-age children in A frica: an increasingly important challenge. Trop. Med. Int. Health 19, 1294–1309. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12374

Ndeketa L., Mategula D., Terlouw D. J., Bar-Zeev N., Sauboin C. J., Biernaux S. (2021). Cost-effectiveness and public health impact of RTS,S/AS01 (E) malaria vaccine in Malawi, using a Markov static model. Wellcome. Open Res. 5, 260. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16224.2

Newton P. N., Green M. D., Mildenhall D. C., Plançon A., Nettey H., Nyadong L., et al. (2011). Poor quality vital anti-malarials in Africa-an urgent neglected public health priority. Malar. J. 10, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-352

Nkosi-Gondwe T., Robberstad B., Blomberg B., Phiri K. S., Lange S. (2018). Introducing post-discharge malaria chemoprevention (PMC) for management of severe anemia in Malawian children: a qualitative study of community health workers’ perceptions and motivation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3791-5

Nkosi-Gondwe T., Robberstad B., Opoka R., Kalibbala D., Rujumba J., Galileya L. T., et al. (2023). Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine or sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for the chemoprevention of malaria in children with sickle cell anaemia in eastern and southern Africa (CHEMCHA): a protocol for a multi-centre, two-arm, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled superiority trial. Trials 24, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13063-023-07274-4

Noor A. M., Kinyoki D. K., Mundia C. W., Kabaria C. W., Mutua J. W., Alegana V. A., et al. (9930). The changing risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection in Africa: 2000–10: a spatial and temporal analysis of transmission intensity. Lancet 2014, 383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62566-0

Nuwa A., Baker K., Bonnington C., Odongo M., Kyagulanyi T., Bwanika J. B., et al. (2023). A non-randomized controlled trial to assess the protective effect of SMC in the context of high parasite resistance in Uganda. Malar. J. 22, 63. doi: 10.1186/s12936-023-04488-4

Ocan M., Akena D., Nsobya S., Kamya M. R., Senono R., Kinengyere A. A., et al. (2019). K13-propeller gene polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum parasite population in malaria affected countries: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Malar. J. 18, 60. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2701-6

Ogbulafor N., Uhomoibhi P., Shekarau E., Nikau J., Okoronkwo C., Fanou N. M., et al. (2023). Facilitators and barriers to seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) uptake in Nigeria: a qualitative approach. Malar. J. 22, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12936-023-04547-w

Ojakaa D. I., Jarvis J. D., Matilu M. I., Thiam S. (2014). Acceptance of a malaria vaccine by caregivers of sick children in Kenya. Malar. J. 13, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-172

Okello G., Ndegwa S. N., Halliday K. E., Hanson K., Brooker S. J., Jones C. (2012). Local perceptions of intermittent screening and treatment for malaria in school children on the south coast of Kenya. Malar. J. 11, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-185

Okereke E., Smith H., Oguoma C., Oresanya O., Maxwell K., Anikwe C., et al. (2023). Optimizing the role of ‘lead mothers’ in seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) campaigns: formative research in Kano State, northern Nigeria. Malar. J. 22, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12936-023-04447-z

Okesanya O. J., Atewologun F., Lucero-Prisno D. E. III, Adigun O. A., Oso T. A., Manirambona E., et al. (2024). Bridging the gap to malaria vaccination in Africa: Challenges and opportunities. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2, 100059. doi: 10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100059

Olotu A., Fegan G., Wambua J., Nyangweso G., Leach A., Lievens M., et al. (2016). Seven-year efficacy of RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine among young African children. New Engl. J. Med. 374, 2519–2529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515257

Owen B. N., Winkel M., Bonnington C., Nuwa A., Achan J., Opigo J., et al. (2022). Dynamical malaria modeling as a tool for bold policy-making. Nat. Med. 28, 610–611. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01756-9

Phiri K. S., Calis J. C., Faragher B., Nkhoma E., Ng’oma K., Mangochi B., et al. (2008). Long term outcome of severe anaemia in Malawian children. PloS One 3, e2903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002903

Phiri K. S., Khairallah C., Kwambai T. K., Bojang K., Dhabangi A., Opoka R., et al. (2024). Post-discharge malaria chemoprevention in children admitted with severe anaemia in malaria-endemic settings in Africa: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Global Health 12, e33–e44. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00492-8

Pitt C., Diawara H., Ouédraogo D. J., Diarra S., Kaboré H., Kouéla K., et al. (2012). Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in children: a qualitative study of community perceptions and recommendations in Burkina Faso and Mali. PloS One 7, e32900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032900

Platon L., Ménard D. (2024). Plasmodium falciparum ring-stage plasticity and drug resistance. Trends Parasitol. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2023.11.007