95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Lang. Sci. , 14 October 2024

Sec. Psycholinguistics

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/flang.2024.1452971

This article is part of the Research Topic Interacting factors in the development of discourse practices from childhood to adulthood View all 5 articles

Introduction: While verbal irony is a pragmatic skill that plays a very important role in social interactions, its development has not been sufficiently studied, especially in the context of the Spanish language. This research aims to generate a deeper understanding of the development of irony, specifically among Mexican adolescents. One of the pragmatic aspects identified as an important factor to consider in the comprehension and production of verbal irony is the gender of the participants involved in the communicative interaction. Prior research with adults indicates that ironic statements produced by men are generally associated with positive discursive functions, whereas those made by women are often perceived negatively. This study aims to analyze the metapragmatic reflections of 37 Mexican adolescents aged 12 and 15 years old (20 and 17 participants, respectively, half women) on how the gender of the interlocutors influences the use of irony in various communicative situations.

Methods: Participants were presented with eight written scenarios that concluded with a written ironic statement (in order to minimize the effects of prosody). The scenarios were counterbalanced to account for the type of ironic remark (critical or praise irony), the gender of the ironist, and the gender of the audience. Through a semi- structured oral interview, the adolescents' reflections and the rationale behind their responses were examined.

Results: The results revealed significant differences in the interpretation of irony based on age, type of statement (criticism or praise), and the gender of the interlocutors, though not with respect to the gender of the audience. Additionally, a discrepancy was observed between the metapragmatic reflections expressed by adolescents regarding ironic statements and their actual interpretation of irony.

Discussion: These findings suggest that during adolescence, individuals develop an increasing capacity to consider factors related to gender roles that influence the pragmatic interpretation of ironic statements.

Verbal irony has been documented as the type of non-literal language of latest acquisition in studies on linguistic development during the school years (Banasik-Jemielniak et al., 2020; Glenwright et al., 2017; Pexman, 2023, 2024; Zajączkowska et al., 2020; Zufferey, 2016). It is a linguistic device, expressed either orally or in writing, where the real meaning is concealed or contradicts the literal meaning of the words (Colston, 2017; Giora and Attardo, 2014; Kalbermatten, 2010). Verbal irony may involve a discrepancy, negation, contradiction, or opposition between the speaker's intention and the utterance (Attardo, 2000, 2013). For instance, an expression such as What great weather for a picnic! uttered on a rainy day would be considered ironic, as the literal words contradict the speaker's intended meaning. Furthermore, irony is a mode of thought and communication that encourages individuals to perceive the world in new ways (Gibbs and Colston, 2023). It serves as a discursive strategy and choice of the speaker, conveying a range of pragmatic messages and often used for various purposes—including criticism, humor, status elevation, aggression, emotional control, and praise—though its prototypical function is typically criticism (Kalbermatten, 2010). The use of irony enables speakers to achieve complex social and interactive objectives, thereby fostering improved social relationships (Colston, 2017).

Research into how children and adolescents acquire verbal irony has increased in recent years (see Filippova, 2014; Pexman, 2023, and Fuchs, 2023, for further reference). These studies indicate that while children begin to interpret ironic statements around the age of nine, the ability to consider the various pragmatic aspects involved in the accurate understanding and production of irony continues to develop well into adolescence (Filippova, 2014; Fuchs, 2023; Nippold, 2016; Pexman, 2023). This ongoing development is attributed to the fact that interpreting verbal irony necessitates a range of linguistic, cognitive, communicative, and social skills. Specifically, research has demonstrated a direct relationship between the development of verbal irony and Theory of Mind skills, linguistic development, and social experience with ironic language (Filippova, 2014; Pexman, 2023; Szücs and Babarczy, 2017; Tolchinsky and Berman, 2023). To comprehend the meaning of an ironic expression, it is necessary to recognize the intentional meaning behind the words, which can only be accessed through pragmatic meaning contingent on the situational context (Attardo, 2013; Ruiz and Alvarado, 2013; Schnell and Varga, 2012).

Since the accurate interpretation of verbal irony involves pragmatic knowledge about the intentions of participants within a specific communicative context, it has been observed that the social roles of those involved in the ironic interaction—both the interlocutors and the audience—are crucial for interpreting ironic statements. One important factor to consider is the gender of the participants in the ironic event. Various studies have documented differences in how women and men interpret and use irony. These studies indicate that, generally, women perceive verbal irony as a discursive tool for reinforcing criticism and expressing discontent, whereas men view it primarily as a humorous device that mitigates criticism and can strengthen social bonds (Milanowicz, 2013; Milanowicz et al., 2017). Both men and women report using verbal irony more frequently when the interlocutor is another man rather than a woman (Milanowicz and Kałowski, 2016; Rockwell and Theriot, 2001). Additionally, men often use ironic conversation as means to assert their power and self-image, while women typically use it to maintain relationships and avoid causing offense, resulting in less frequent use of irony (Colston and Lee, 2004; Jorgensen, 1996; Milanowicz, 2013). Specifically, in studies involving children and adolescents, Hess et al. (2022) reported that individuals aged 9 and 15 (both male and female) find it easier to interpret verbal irony when at least one male is involved in the communicative interaction, either as the ironist or as the victim of the irony. Luna et al. (2023) discovered that in individuals aged 9–12, the processing of irony at the brain level varies depending on whether it is spoken by a woman or a man. Additionally, Hess et al. (2021) observed that as adolescents mature, they increasingly consider the gender of the audience when interpreting verbal irony, suggesting that the audience's gender may influence adolescents' perceptions of ironic statements.

An effective method for analyzing how children and adolescents interpret verbal irony is through their metapragmatic reflections on ironic statements. Metapragmatic ability refers to the capacity to consciously reflect on the relationship between the linguistic elements of an utterance and the communicative and social context in which it occurs (Adams et al., 2018; Ruiz-Gurillo, 2016; Szücs and Babarczy, 2017; Timofeeva-Timofeev, 2016), as well as the ability to verbalize the pragmatic rules governing the use of a linguistic expression (Baroni and Axia, 1989; Timofeeva, 2017). It has been observed that the capacity for metapragmatic reflection is directly related to the use of non-literal language—including irony—because both skills require transcending implicit knowledge structural properties used in everyday language to focus on the speaker's intention. In other words, they require the ability to “read” the interlocutor's mind and comprehend both the purpose behind the message and what is appropriate for a given context (Garfinkel et al., 2024; Tolchinsky and Berman, 2023).

In light of the preceding discussion, the purpose of this study is to analyze the metapragmatic reflections of Mexican adolescents aged 12 and 15 on verbal irony in different communicative situations where the gender of the interlocutors is a variable to consider. This study aims to answer the following research questions:

(1) Are there age-related differences in the interpretation of irony of 12 and 15-year-old adolescents?

(2) Does the social function of the ironic statement (criticism or praise) influence its interpretation?

(3) Is the interpretation of irony affected by the gender of the interlocutors or the gender of the audience in an ironic event?

(4) What types of metapragmatic reflections do adolescents have regarding the importance of interlocutor gender or audience gender in an ironic event?

The study involved 37 adolescents aged 12 and 15 from a school in Querétaro, Mexico (see Table 1). These age groups were selected because they correspond to the end of elementary and middle school education in Mexico, respectively. Additionally, previous research on metalinguistic reflections on verbal irony has indicated that significant changes in the interpretation of ironic statements occur at these ages (Hess et al., 2017, 2018, 2022, 2023). To qualify for the study, participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: be currently enrolled in school; be exactly 12 or 15 years old; demonstrate typical linguistic and cognitive development without reported difficulties in reading and writing as noted by their school, and not have repeated any school year. Furthermore, participants had to be native speakers of Mexican Spanish and capable of understanding ironic statements, which was confirmed using a screening instrument adapted from previous research (Hess et al., 2017, 2018), as explained further below. Prior to starting the study, an analysis was performed using G*Power 3 (Faul et al., 2007) to establish the optimal sample size. The study took into account a moderate F effect size of 0.33 ( = 0.1, Cohen, 1992) and a statistical power of 0.8 for an ANOVA with two groups and eight repeated measures. The analysis advised a total sample size of 40–42 people. As a result, it was decided that the optimal sample size would be 21 people in each group. However, data from some of the initial sample participants could not be included in the study due to inconsistencies in their responses, resulting in a total sample of 37 participants. Nonetheless, given the effect sizes reported in this study (refer to Section 3), this sample size is acceptable.

All adolescents were administered two tasks: a screening instrument to ensure their comprehension of ironic expressions and a metapragmatic reflection instrument to elicit their metapragmatic reflections in response to various ironic scenarios. The details of both instruments are described below.

To ensure that participants were capable of understanding verbal irony, which was essential for producing metapragmatic reflections, all adolescents were administered a screening instrument validated in previous studies on irony interpretation with similar populations (see Hess et al., 2017, 2018). The screening test comprises eight brief written stories: four conclude with a prototypical ironic statement (characterized by a discrepancy between the literal and intended meaning; and a critical function) and four conclude with a non-ironic statement. Only participants who correctly interpreted at least three out of the four ironic stories were included in the study. The screening instrument is provided in Appendix A.

To analyze the participants' metapragmatic reflections on ironic statements, an instrument was developed based on similar tools used in previous studies (see Hess et al., 2017, 2018, 2021). The instrument designed for this study presented various ironic scenarios, considering the following three variables:

• Social function of irony: criticism or praise. Psycholinguistic studies have indicated that criticism in language is often associated with male roles, whereas praise is linked to social cooperation and language styles typically used by women (Hoff, 2014; Merino and Mar, 2017; Jiménez, 2010; Lomas, 2007). It was anticipated that these gender-related differences could be reflected in the participants' metapragmatic reflections on ironic statements involving criticism or praise. Additionally, research has shown that ironic comments are more frequently directed at failures rather than successes (Jorgensen, 1996; Kalbermatten, 2006, 2010). Therefore, it was expected that adolescents would provide more nuanced metapragmatic reflections on critical irony compared to praise irony.

• Gender of the audience present in the ironic interaction: ironic statements to either a male audience or a female audience. Previous research indicates that interactions involving verbal irony differ based on whether the audience is male or female. Specifically, irony tends to be met with literal comments in interactions with female participants, while responses are more likely to be ironic when interacting with male participants (Milanowicz, 2013; Milanowicz and Kałowski, 2016). Therefore, it was anticipated that adolescents would consider the gender of the audience when reflecting on ironic statements.

• Gender of the interlocutors: irony produced between female interlocutors or male interlocutors. Research with adults has indicated that women often view verbal irony as a tool for reinforcing criticism and expressing discontent, whereas men perceive it as a humorous device that can mitigate criticism and strengthen social bonds (Milanowicz, 2013; Milanowicz and Kałowski, 2016). Consequently, it was expected that adolescents would consider the gender of the interlocutors when reflecting on ironic statements.

The three variables were combined to create the final instrument, which comprised eight scenarios organized as shown in Table 2.

In creating the scenarios, several factors were considered. Firstly, the scenarios were designed as brief narratives that provided sufficient context for adolescents to extract pragmatic information from the ironic event, including the gender of the interlocutors and the gender of the audience, for their reflections. The scenarios were constructed to be interpretable as ironic based on pragmatic context rather than solely on the ironic statement produced by the ironist. The length of the texts was controlled to ensure that all were brief, of approximately the same length and structure. Additionally, the grammatical structure of the sentences was kept simple, and the vocabulary common, appropriate for the participants' ages, and not intended to present an additional linguistic challenge to the reflection on irony. The interlocutors depicted in the scenarios were required to be of the same social hierarchy and to share a common goal. Additionally, care was taken to ensure that the activities undertaken by the interlocutors did not perpetuate gender stereotypes, to avoid influencing participants' reflections. The ironic comment, whether of criticism or praise, was always placed at the end of the text and directed toward an action performed by the victim of the irony within the narrative. The ironic statements included an adverb or adjective indicating a discrepancy between the literal and intended meaning. Finally, during the administration of the instrument, the scenarios were counterbalanced to prevent fatigue or learning effects among participants. The final scenarios are provided in Appendix B.

The instrument was administered to each adolescent in an individual session held in a space provided by the school. Each participant read the ironic stories one by one and, following each story, engaged in a semi-structured interview designed to elicit as many metapragmatic reflections as possible regarding the ironic statement. The interview was guided by a script focused on three key aspects: (1) interpretation of the statement as ironic (questions a and b); (2) the gender of the audience to whom the ironic statement was directed (question c); and (3) the gender of the interlocutors in the story (question d). The guiding questions for each aspect are outlined below:

(a) ¿Para qué dijo (ironista) esta frase (frase irónica)? “What did he/she (ironist) say this phrase (ironic phrase) for?” ¿Qué crees que quiso decir? “What do you think he/she meant?”¿Cómo sabes eso? “How do you know?” ¿Qué te dio la pista? “What gave you the clue?”

(b) ¿Pudo haberlo dicho de otra manera? “Could he/she have said it in another way?” ¿Cómo? “How?”¿Entonces, por qué crees que A (ironista) se lo dijo a B (víctima) así y no de otra manera? “Then why do you think that A (ironist) said it to B (victim) in this way and not in another way?”

(c) ¿Si A se lo hubiera dicho frente a un grupo de amigas mujeres/amigos hombres en lugar de amigas/amigos se valdría más? “If A had said it in front of a group of female friends/male friends instead, would it have been more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” ¿Cómo lo sabes? “How do you know?” ¿Qué te dio la pista? “What gave you the clue?”

(d) ¿Si A fuera mujer/hombre se valdría más? “If A were a woman/man, would it be more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” ¿Si B fuera mujer/hombre se valdría más? “If B were a woman/man, would it be more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?”

All interviews were transcribed and entered into a Microsoft Excel database, with each variable (interpretation and social function of irony, gender of the audience, and gender of the interlocutors) organized into separate sheets. Each sheet was coded according to the criteria detailed below. To ensure coding reliability, two independent coders assigned values to each response based on the established classifications for each variable. All discrepancies between the coders were reviewed by a third judge until 100% agreement was achieved.

An adaptation of the classification system similar to that proposed by Hess et al. (2018) and Hess et al. (2022) was employed for coding metapragmatic reflections focused on the level of ironic interpretation. Responses from adolescents to questions such as ¿Para qué dijo (ironista) esta frase (frase irónica)? “What did he/she (ironist) say this phrase (ironic phrase) for?” ¿Qué crees que quiso decir? “What do you think he/she meant?”¿Cómo sabes eso? “How do you know?” ¿Qué te dio la pista? “What gave you the clue?” were assigned scores ranging from 0 to 4, depending on the type of metapragmatic reflections provided (see Table 3). This coding aimed to assess whether participants were able to interpret the statements as ironic and to explicitly identify elements of verbal irony.

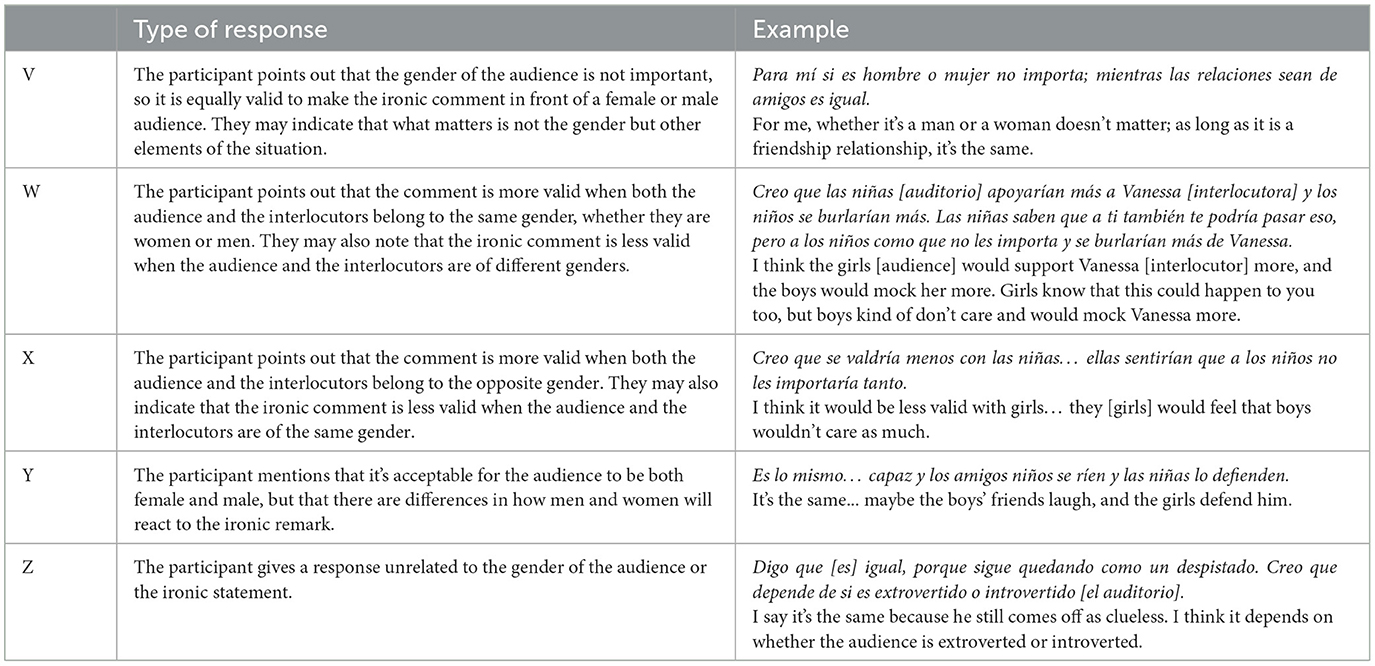

For all utterances that adolescents interpreted as ironic (responses of types 2, 3, 4, and 5 from the previous section), metapragmatic reflections regarding the gender of the audience to whom the ironic statement was addressed were coded. Specifically, reflections corresponding to the following questions were coded: ¿Si A se lo hubiera dicho frente a un grupo de amigas mujeres/amigos hombres en lugar de amigas/amigos se valdría más? “If A had said it in front of a group of female friends/male friends instead, would it have been more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” ¿Cómo lo sabes? “How do you know?” ¿Qué te dio la pista? “What gave you the clue?”. The coding according to this criterion is detailed in Table 4.

Table 4. Metapragmatic reflections on the importance of the gender of the audience in utterances interpreted as ironic.

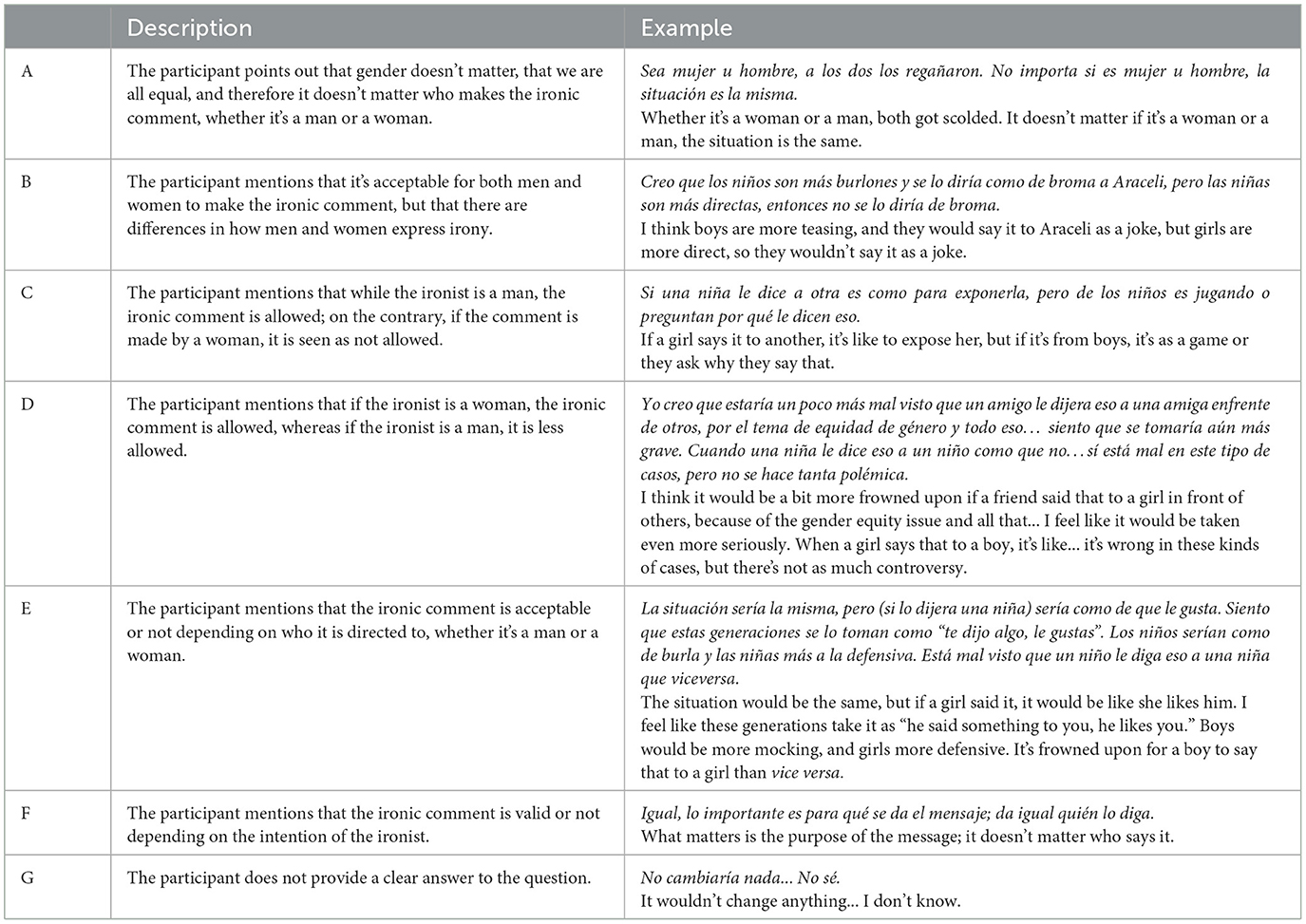

Similarly, metapragmatic reflections on the gender of the interlocutors in stories interpreted as ironic were also coded. Thus, responses from adolescents to the questions ¿Si A fuera mujer/hombre se valdría más? “If A were a woman/man, would it be more valid?”¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” ¿Si B fuera mujer/hombre se valdría más? “If B were a woman/man, would it be more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” were coded as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Metapragmatic reflections on the importance of the gender of the interlocutors in utterances interpreted as ironic (adapted from Hess et al., 2022).

As previously mentioned, the task for participants in the study involved reading eight scenarios that concluded with an ironic statement, followed by a series of questions designed to explore their metapragmatic reflections on the ironic situation present in the stories. The levels of irony interpretation, as described earlier, could be classified into literal interpretation (0 points), ironic interpretation without mentioning prototypical characteristics of irony (1 point), ironic interpretation with communicative function (2 points), dual interpretation (ironic interpretation or prosocial lie, 3 points), and ironic interpretation with explicitness (4 points) (see Table 3). Based on these classifications, a statistical analysis of the results was conducted using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with two between-group factors: age (12 and 15) and gender (male vs. female), and three repeated measures factors: type of irony according to its social function (criticism vs. praise), gender of the ironist (male vs. female), and gender of the audience in the ironic story (males vs. females). The analyses were performed using JASP Team (2024).

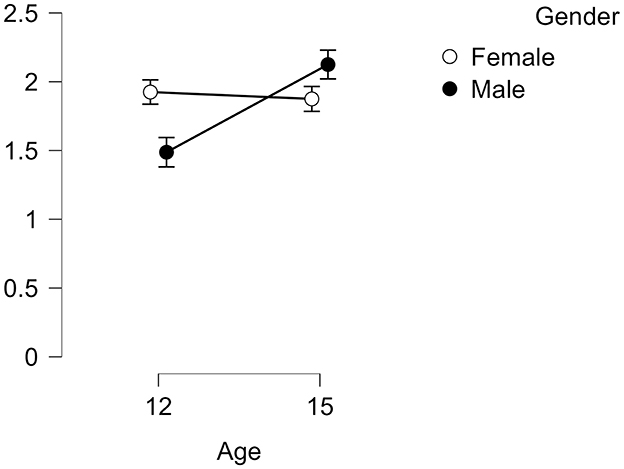

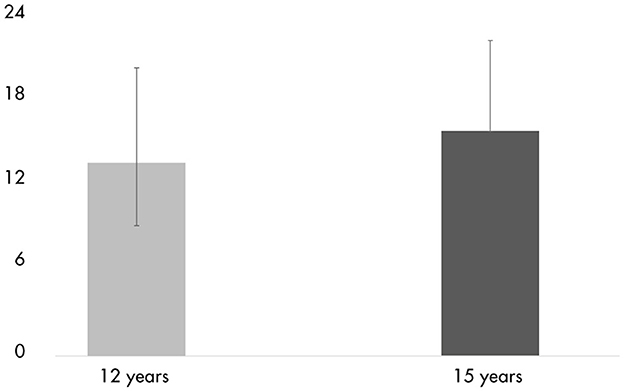

The first objective was to assess the level of interpretation demonstrated by participants according to their age group. The results of this initial analysis are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mean scores obtained in the level of interpretation of verbal irony by age group (the “X” axis shows the ages and the “Y” axis shows the mean number of interpretations present).

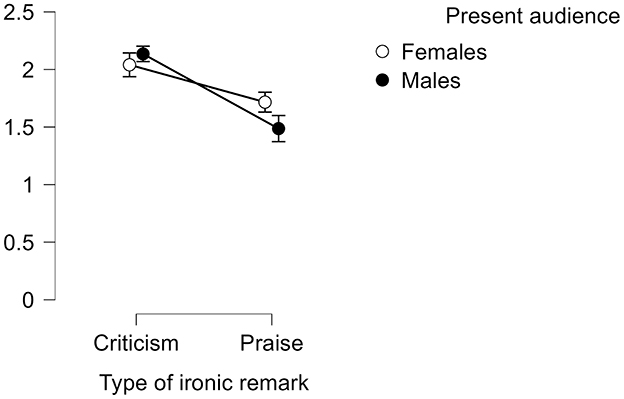

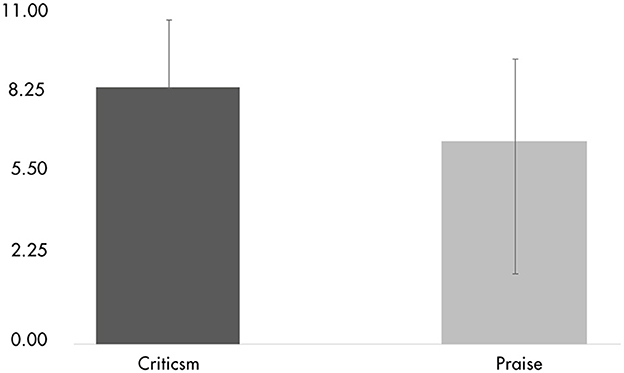

As shown in Figure 1, there is an increase in the level of interpretation of verbal irony in the reflections as age progresses. This difference was found to be statistically significant in the ANOVA, which revealed a main effect of age [F(1, 33) = 5.51, p = 0.025, = 0.14]. The results of the ANOVA did not show a main effect of participant gender, indicating that there are no significant differences in how adolescent boys and girls interpret the ironic stories [F(1, 33) = 0.56, p = 0.45]. Figure 2 shows that the mean score obtained for ironic utterances of criticism is higher than for those of praise. The ANOVA indicated a main effect of the type of utterance (criticism vs. praise) [F(1, 33) = 17.89, p < 0.001, 0.35] on the level of irony interpretation.

Figure 2. Mean scores obtained in the level of interpretation of verbal irony according to the type of utterance (criticism or praise) for the entire sample (the “X” axis shows the type of utterance according to its social function and the “Y” axis shows the mean number of interpretations present).

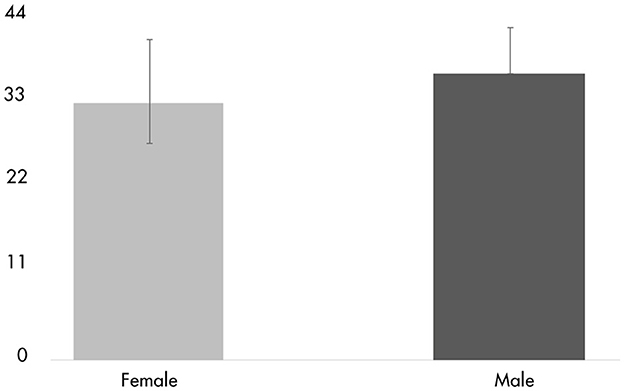

The results regarding whether there were differences in the level of interpretation of ironic utterances based on the gender of the interlocutors (male or female) in the ironic event are presented in Figure 3. The figure shows that the mean score for interpreting of ironic utterances produced by male interlocutors is higher than that for those expressed by female interlocutors. The effect of interlocutor gender was significant in the ANOVA conducted [F(1, 33) = 5.17, p = 0.03, 0.13].

Figure 3. Mean scores obtained in the level of interpretation of verbal irony according to the gender of the interlocutors (female or male) for the entire sample (the “X” axis shows the type of interlocutors and the “Y” axis shows the mean quantity of interpretations present).

On the other hand, the ANOVA results showed two significant interactions between variables. The first interaction occurred between the factors of participant gender and age [F(1, 33) = 7.54, p = 0.01, 0.18]. This suggests that females and males reflect differently on ironic utterances at different ages. While females show similar reflections (in quantity and quality) at ages 12 and 15, males exhibit less elaborate reflections at age 12 and a significant increase in the quality of their reflections as they get older, which was confirmed by a Holm post hoc test (p < 0.005) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Interaction between participant gender*age factors (the “X” axis shows ages, and the “Y” axis shows the level of interpretation of verbal irony).

Although the audience gender (male vs. female) variable did not have a significant effect on the interpretation of irony [F(1, 33) = 0.44, p = 0.51], an interaction was found between the factors of ironic utterance type and gender of the audience in the story [F(1, 33) = 7.0, p = 0.012, = 0.17]. This interaction suggests that ironic utterances (criticism or praise) are interpreted differently depending on the gender of the audience they are addressed to (male or female). Specifically, ironic utterances of criticism and praise received similar interpretation scores when presented to a female audience, whereas when presented to a male audience, praise received lower interpretation scores compared to criticism (p < 0.001, Holm post-hoc) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Interaction between the factors of ironic utterance type*audience gender in the story (the “X” axis shows the type of ironic utterance, and the “Y” axis shows the level of interpretation of irony).

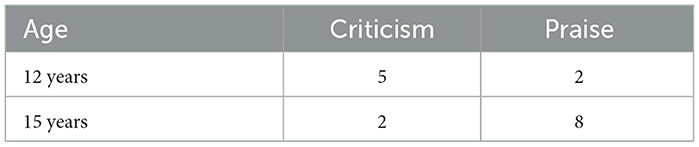

An additional aspect observed during the analysis of participants' responses from both age groups regarding the interpretation of verbal irony is that both age groups interpreted various ironic utterances (both praise and criticism) as prosocial lies. That is, several participants attributed to the ironic utterance the meaning of a lie where the intention is not to hurt the interlocutor's feelings but to benefit them (see type D responses in Table 3). A Chi-square test showed a dependency between age group and the type of utterance in interpreting irony as prosocial lies [ = 4.49, p = 0.03] (see Table 6).

Table 6. Interpretation of irony as prosocial lies by age and type of statement (criticism or praise).

As shown in Table 6, the 12-year-old participants more frequently interpreted irony as prosocial lies in the criticism utterances, whereas in the 15-year-old group, these interpretations occurred more often in praise utterances. Additionally, the analysis examined whether the presence of interpretations of irony as prosocial lies was related to the gender of the audience in front of which the ironic comment was made. This analysis was conducted for the entire sample (see Table 7).

In Table 7, it can be observed that the number of cases where irony is interpreted as a prosocial lie is more frequent when the audience witnessing the ironic interaction is female than when it is male. A Chi-square test showed that this effect was significant [ = 4.69, p = 0.03]. Similarly, the analysis sought to answer whether there were differences in the interpretation of irony as a prosocial lie based on the gender of the interlocutors in the ironic stories, as shown in Table 8 for the entire sample.

In Table 8, it is evident that participants from both age groups more frequently interpreted irony as a prosocial lie when both the ironist and victim were women, as opposed to when they were men. Conversely, instances where irony was not perceived as a prosocial lie were more common in interactions involving male interlocutors. This association was statistically significant, as confirmed by a Chi-square test [ = 9, p = 0.002].

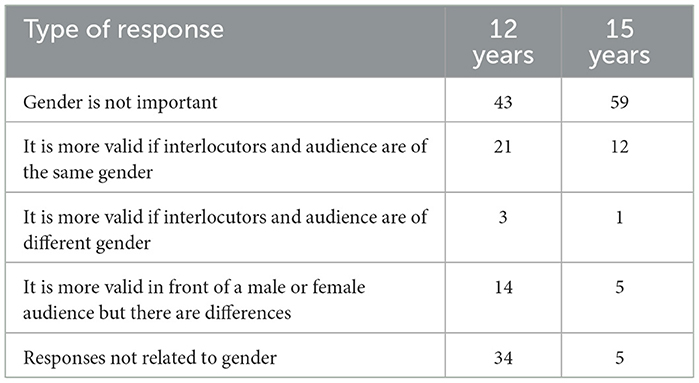

In the second stage of the analysis, participants' metapragmatic reflections on the significance of the audience's gender in ironic comments were examined. Responses to the interview questions, such as ¿Si A se lo hubiera dicho frente a un grupo de amigas mujeres/amigos hombres en lugar de amigas/amigos se valdría más? “If A had said it in front of a group of female friends/male friends instead, would it have been more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” ¿Cómo lo sabes? “How do you know?” ¿Qué te dio la pista? “What gave you the clue?” were included. The responses were categorized into the following groups: gender is not important, more valid among interlocutors and audience with the same gender, more valid among opposite-gender interlocutors and audience, gender is not important, but men and women react differently, and responses not related to gender (see Table 4). The results of this analysis are presented in Table 9.

Table 9. Frequency of metapragmatic reflections of the gender of the audience in utterances interpreted as ironic.

In Table 9, it can be observed that the type of responses varies according to the participants' age group. The 12-year-old group exhibited a higher frequency of responses not related to gender, while this type of response was less frequent in the 15-year-old group. Similarly, responses indicating that gender is not important were more prevalent among the 15-year-olds compared to the 12-year-olds. For both groups, the least common responses fell into the category of “more valid among opposite-gender interlocutors and audience.” A Chi-square test [Yates = 27.01, p < 0.001] demonstrated a significant dependency between the type of responses provided by adolescents and their age. This indicates that reflections on the importance of the audience's gender in the ironic event vary with age.

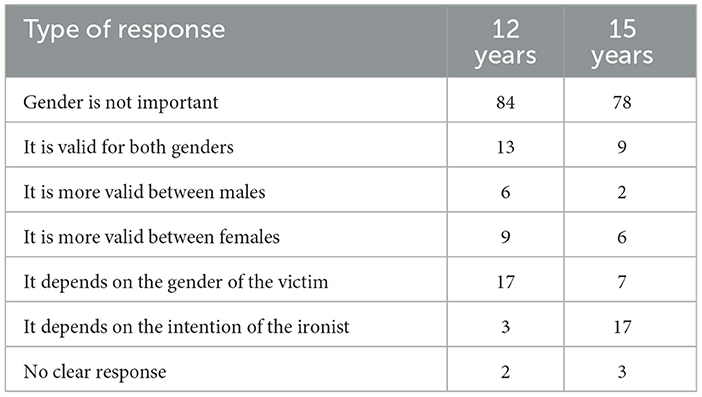

Finally, akin to the previous section, the metapragmatic reflections provided by the participants were analyzed based on the final questions of the semi-structured script: ¿Si A fuera mujer/hombre se valdría más? “If A were a woman/man, would it be more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” ¿Si B fuera mujer/hombre se valdría más? “If B were a woman/man, would it be more valid?” ¿Por qué piensas eso? “Why do you think that?” Participants' responses were categorized into the following options: gender is not important, valid in both genders, more valid in men, more valid in women, depends on the victim's gender, depends on the ironist's intention, and does not give a clear answer (see Table 5). The results of this analysis are presented in Table 10.

Table 10. Frequency of metapragmatic reflections of the gender of the interlocutors in utterances interpreted as ironic.

In Table 10, it can be observed that the type of responses varies according to the age group. Responses from the 12-year-olds are distributed among the first four categories, which focus on the gender of the interlocutors in the story). Conversely, the 15-year-olds, in addition to providing responses in these categories, also focused on an additional category: the intention of the ironist. A Chi-square test [Yates = 17.19, p = 0.03] showed a significant dependence between the type of responses given by adolescents and their age. This indicates that responses regarding the importance of the gender of the interlocutors in the ironic event differ according to each age group.

At a first stage, our findings reveal a significant increase in the ability to interpret verbal irony between the ages of 12 and 15. This trend aligns with previous studies on metalinguistic and metapragmatic reflections on irony, which have demonstrated that adolescence is a critical period for significant cognitive and interpretive developments that enhance young people's ability to understand and reflect on ironic utterances (Hess et al., 2017, 2018, 2021, 2022). Our results also support the idea that the age at which children and adolescents acquire the ability to interpret irony is influenced by the nature of the linguistic tasks they encounter, as suggested by Bernicot et al. (2007) and Fuchs (2023). Specifically, the data indicate that the capacity to produce metapragmatic reflections on verbal irony continues to evolve well into adolescence. This finding is consistent with Collins et al. (2014), who argue that producing metapragmatic judgments is a complex skill that develops later, because it requires an understanding of the speaker's intentions, the listener's expectations, the pragmatic nature of the speech act, and the context in which the utterance occurs.

Another important aspect highlighted by our study is that during adolescence, the development of the ability to interpret verbal irony progresses similarly for both girls and boys. However, we identified a correlation between gender and age. Specifically, our data revealed that girls showed consistent interpretative skills for ironic utterances at both ages 12 and 15. In contrast, boys exhibited a significant increase in this ability between these ages. This finding suggests that the linguistic development of girls and boys may not progress at the same rate, a phenomenon that has been observed in both early (Brooks and Kempe, 2012) and later stages of development (Merino and Mar, 2017; Jiménez, 2010). It is noted that while females and males experience analogous changes in brain development during puberty and adolescence, these changes do not occur at the same ages for both genders. For instance, research indicates that the volume of gray matter in the frontal and parietal lobes undergoes a notable increase during preadolescence, typically around age 11 in females and age 12 in males (Giedd et al., 1999). This difference may account for why our female participants' interpretation of irony remains consistent between ages 12 and 15, whereas males experience significant cerebral changes at age 12, leading to enhanced interpretation skills by age 15.

Regarding the interpretation of irony based on the type of ironic utterance (criticism or praise), our results indicated that ironic criticism was significantly easier to interpret than ironic praise. This outcome was anticipated, as ironic criticism is considered the most prototypical form of irony (Kalbermatten, 2010). Furthermore, existing literature suggests that young children struggle with interpreting ironic praise (Fuchs, 2023), and that this difficulty persists into adolescence (Hess et al., 2017). This challenge stems from the fact that ironic criticism necessitates the recognition of a discrepancy between the literal words and the speaker's intention, whereas ironic praise requires the detection of a double negation. The double negation involved in interpreting ironic compliments emerges because the listener must negate the inherently negative surface meaning of the utterance, a process that imposes an increased cognitive load (Whalen and Pexman, 2010).

Additionally, our findings revealed a dependent relationship between age group and type of irony (criticism or praise) in the interpretation of ironic utterances as prosocial lies. Specifically, 12-year-old adolescents more often interpreted critical utterances as prosocial lies, whereas 15-year-olds were more likely to interpret praise utterances in this manner. Given that both praise and prosocial lying are related with positive linguistic behaviors (Ditmarsch et al., 2020; Hess et al., 2022; Lavoie and Talwar, 2018), it appears that older adolescents are better equipped than their younger counterparts to recognize the positive social function embedded in ironic praise utterances.

The results of how irony is interpreted in relation to the gender of the audience revealed that, overall, adolescents interpret irony similarly regardless of whether it is directed at a female or male audience. However, the interaction between the type of ironic utterance (criticism or praise) and audience gender indicated that while critical irony is interpreted consistently across both female and male audiences, ironic praise irony is more challenging to interpret when directed at a male audience compared to a female audience. This finding initially suggests that adolescents may perceive critical ironic utterances universally applicable to any type of audience. However, these findings diverge from those reported in studies on ironic interactions among adults. Research suggests that men often use sarcastic irony more frequently with male friends to convey displeasure or disapproval toward specific individuals or objects, and that men are generally better at recognizing humor in such ironic expressions compared to women, who are more likely to feel offended or annoyed by ironic remarks (Colston and Lee, 2004; Milanowicz and Kałowski, 2016). This discrepancy between our results and those of the aforementioned studies may be attributable to two factors: (1) cultural variations in the perception of irony, suggesting that North American (Colston and Lee, 2004) and Polish (Milanowicz and Kałowski, 2016) populations might differ from the Mexican population in their interpretation of ironic utterances; and (2) the possibility that adolescents in our study have not yet developed an awareness that the gender of the audience is a relevant pragmatic factor in the interpretation of critical irony. This issue is explored further in the discussion below.

Furthermore, it is important to note that our adolescents experienced greater difficulty interpreting praise irony when it was directed at a male audience compared to a female audience. This difficulty aligns with expectations, given that adult studies indicate critical and aggressive irony is more prevalent in male groups than in female groups (Colston and Lee, 2004; Milanowicz and Kałowski, 2016). This pattern may suggest that the adolescents' challenges with interpreting praise irony in a male context reflect broader cultural tendencies observed in adult interactions. Therefore, it can be assumed that praise irony might be more prevalent in groups of women, given that girls and women are often noted for using more polite language to strengthen social bonds, emphasizing inclusivity, cooperation, and positive rapport (Brooks and Kempe, 2012; Colston and Lee, 2004). The difficulty our participants experienced in interpreting praise irony when it was directed at a male audience—regardless of whether the interlocutors of the irony are women or men—suggests that, in these instances, they do consider the gender of the audience. This contrasts with the interpretation of critical irony, indicating that the gender of the audience may play a more significant role in understanding praise irony.

The results showing that adolescents do not consider the gender of the audience in critical irony but do in praise irony reveal an interesting aspect of their interpretative processes. This apparent contradiction suggests that adolescents in our study, regardless of age group, face challenges in concurrently accounting for both the gender of the interlocutors and the gender of the audience when interpreting irony. Specifically, in the context of critical irony, adolescents seem to focus on the gender of the interlocutors rather than the audience. Conversely, when interpreting praise irony, they appear to be more attentive to the gender of the audience. This discrepancy highlights a developmental limitation in the adolescents' ability to integrate multiple contextual factors into their understanding of ironic expressions. Furthermore, the difficulties in considering both the gender of the audience and the interlocutors appear to stem from the requirement to account for the mental states (such as thoughts, perspectives, and expectations) and gender social roles of all four participants involved in the communicative interactions presented in our scenarios. This complex task seems to exceed the capabilities of 12- and 15-year-old adolescents. This finding is consistent with previous research, which indicates that during adolescence, the ability to consider the perspectives of an increasing number of interlocutors in ironic interactions is still developing (Hess et al., 2021).

Regarding the influence of the interlocutor gender on the interpretation of irony, our results indicated that ironic utterances were significantly easier for participants to interpret when produced by male interlocutors compared to female interlocutors. Additionally, irony occurring in exchanges between girls was more readily interpreted as a prosocial lie than irony occurring between boys. These findings align with previous research on adults showing that verbal irony is more frequently used among male interlocutors (Colston and Lee, 2004; Milanowicz and Kałowski, 2016; Rockwell and Theriot, 2001). Furthermore, studies on the development of irony have reported that children and adolescents more effectively interpret ironic utterances produced by male interlocutors (Hess et al., 2022), and that the brain processing of irony involving female interlocutors requires more cognitive resources compared to irony involving male interlocutors (Luna et al., 2023). In this context, it is evident that our participants are already able to account for the type of linguistic behavior socially expected from men and women when interpreting ironic utterances. Research has shown that the activation of socially stereotyped knowledge, such as gender stereotypes, is an immediate and automatic process during language processing rather than a result of deliberate inference (Lepore and Brown, 1997). Studies indicate that knowledge about gender can implicitly influence language processing at the semantic level or affect the inferences made while comprehending texts (Casado et al., 2023; Garnham et al., 2002; Molinaro et al., 2016). This influence is particularly pronounced in non-literal language, as interpreting such language often relies on social context information, including knowledge about social (Pexman et al., 2000) or gender stereotypes (Cocco and Ervas, 2012). Consequently, the gender-stereotyped knowledge held by participants in our study appears to impact their interpretation of irony.

Regarding the metapragmatic reflections exhibited by the participants concerning the importance of the audience's gender in ironic interactions, our results demonstrated that age was a significant factor. It was evident that the capacity to reflect on the relevance of the gender of participants in ironic events improved notably between the ages of 12 and 15. Specifically, responses unrelated to gender diminished, while those addressing gender increased. This challenge is likely due to the growing ability of individuals to make more nuanced metapragmatic reflections on utterances, as supported by the findings of Baroni and Axia, 1989, Crespo and Alfaro-Faccio (2010), and Timofeeva (2017).

Conversely, the results indicate that age is also a crucial factor in metapragmatic reflections concerning the importance of the interlocutors' gender in ironic interactions. While 12-year-old adolescents tended to focus their reflections on the gender of the interlocutors, 15-year-olds were more inclined to consider the ironist's intention. This finding is consistent with previous research, which suggests that 12-year-olds can distinguish the communicative function of verbal irony but may struggle to fully grasp the ironist's intention (Hess et al., 2018). By age 15, adolescents are generally better equipped to consider the mental states of both the speaker and other interlocutors involved in the ironic event (Hess et al., 2021).

To sum up, an interesting finding of this study —consistent with previous observations (Hess et al., 2022)— is that adolescents generally report that the gender of the participants in an ironic event is not crucial for interpretating irony. However, the results presented in earlier sections demonstrate that the gender of both the audience and interlocutors significantly influences adolescents' interpretation of both critical and praise irony. This discrepancy may stem from the fact that metapragmatic reflections require a more explicit analysis of gender and irony, which involves not only linguistic knowledge about ironic statements but also implicit knowledge about gender roles and morality (see also Hess et al., 2023). Research has shown that explicit gender stereotypes tend to evolve more rapidly in response to social changes (Charlesworth and Banaji, 2022), whereas implicit stereotypes remain relatively stable over time (Forscher et al., 2019). The differential rate of change may account for the seemingly contradictory results observed in our study. While participants explicitly assert that gender does not influence the interpretation of irony, their actual interpretations reveal an implicit reliance on gender information to assess the ironic nature of statements. This disparity between metapragmatic reflections and the actual interpretation of irony may stem from the divergence between an explicit analysis of the ironic expressions, which considered variables such as social roles and morals, and the implicit analysis occurring during the interpretation of ironic expressions. The interviewer in this study was an adult within a school context, a setting where adults are perceived as authority figures by students, akin to their teachers. This dynamic likely influenced the content of the students' reflections, aligning them with what they deemed socially appropriate and consistent with the explicit moral values prevalent in the country where the study was conducted, as well as the contemporary emphasis on gender equality. However, when participants were asked to interpret whether the stories were ironic, they were not explicitly prompted to consider the gender of the characters. As a result, the adolescents relied on their implicit gender knowledge during their analysis, which led to greater difficulty in interpreting stories with female characters as ironic compared to those with male characters. This suggests that while the adolescents are clearly cognizant of the principle of gender equality, they also recognize that society expects different behaviors from men and women, and this awareness influences their understanding of language features at the pragmatic level. Further research into this phenomenon, along with an examination of additional cognitive and social factors that impact the understanding of irony, could offer deeper insights into adolescents' pragmatic processing. Overall, these findings underscore that the interpretation of irony involves the integration of multiple factors, including cognitive and linguistic development, as well as both explicit and implicit social knowledge accumulated over time. Future research should include a broader sample of adolescents from diverse cultural backgrounds to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, studies involving real-life or recorded interactions are recommended to capture the full range of pragmatic cues associated with irony.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The recruitment of participants and the collection of data were at all times in adhered to the guidelines of the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Querétaro, Mexico. This committee analyzed this project based on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects from the Helsinki Declaration and the CIOMS Guidelines (World Medical Association, 2001; Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), 2016). First, an informed consent form was provided to the parents or legal guardians. This form included the objective of the research, the nature of the minors' participation, the potential applications of the study, and information regarding the use of the provided data. Subsequently, informed assent was obtained from the minors. They received a verbal explanation detailing the nature of their collaboration, the instructions they needed to follow, the procedures of the intervention, and the intended use of the collected data. The identity and confidentiality of the participants were maintained at all times. During transcription and data analysis, the minors' names were encoded. All adolescents participated voluntarily, without any monetary compensation. Additionally, both the guardians and the participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. If either party chose to withdraw, their data would be deleted, and their participation would be terminated without any repercussions.

KH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GA-R: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. AC-R received a scholarship from the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnología (CONAHCYT), which supported her master's studies and her involvement in the research project from which this work is derived.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Sonia Cruz Gallegos for her invaluable assistance in obtaining the interviews with the adolescents who participated in this research. They also extend their gratitude to Natalia García Hess for her contribution to data coding, which facilitated the inter-judge analysis, and to Tanya Almada for her meticulous revision of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/flang.2024.1452971/full#supplementary-material

Adams, C., Lockton, E., and Collins, A. (2018). Metapragmatic explicitation and social attribution in social communication disorder and developmental language disorder: a comparative study. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 61, 604–618. doi: 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-17-0026

Attardo, S. (2000). Irony as relevant inappropriateness. J. Pragmat. 32, 793–826. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00070-3

Attardo, S. (2013). “Intentionality and irony,” in Irony and Humor: From Pragmatics to Discourse, eds L. Ruiz-Gurillo, and M. Belén Alvarado Ortega (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 39–58.

Banasik-Jemielniak, N., Bosacki, S., Mitrowska, A., Walters, D. W., Wisiecka, K., Copeland, N. E., et al. (2020). ‘Wonderful! We've just missed the bus.' – Parental use of irony and children's irony comprehension. PLoS ONE 15:0228538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228538

Baroni, M. R., and Axia, G. (1989). Children's meta-pragmatic abilities and the identification of polite and impolite requests. First Lang. 9, 285–297. doi: 10.1177/014272378900902703

Bernicot, J., Laval, V., and Chaminaud, S. (2007). Nonliteral language forms in children: in what order are they acquired in pragmatics and metapragmatics? J. Pragmat. 79, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.12.002

Casado, A., Sa-Leite, A. R., Pesciarelli, F., and Paolieri, D. (2023). Exploring the nature of the gender-congruency effect: implicit gender activation and social bias. Front. Psychol. 14:1160836. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1160836

Charlesworth, T. E. S., and Banaji, M. R. (2022). Patterns of implicit and explicit stereotypes III: long-term change in gender stereotypes. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 13, 14–26. doi: 10.1177/1948550620988425

Cocco, R., and Ervas, F. (2012). Gender stereotypes and figurative language comprehension. Humana Mente J. Philos. Stud. 5, 43–56.

Collins, A., Lockton, E., and Adams, C. (2014). Metapragmatic explicitation ability in children with typical language development: development and validation of a novel clinical assessment. J. Commun. Disord. 52, 31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2014.07.001

Colston, H. L. (2017). “Irony and sarcasm,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Humor, ed. S. Attardo (New York, NY: Routledge), 234–249.

Colston, H. L., and Lee, S. Y. (2004). Gender differences in verbal irony use. Metaph. Symb. 19, 289–306. doi: 10.1207/s15327868ms1904_3

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) (2016). International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans. Geneva.

Crespo, N., and Alfaro-Faccio, P. (2010). Desarrollo tardío del lenguaje: la conciencia metapragmática en la edad escolar. Univ. Psychol. 9, 229–240. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.upsy9-1.dtlc

Ditmarsch, H., Hendriks, P., and Verbrugge, P. H. R. (2020). Editors' review and introduction: lying in logic, language, and cognition, in Topics in Cognitive Science 12, 466–484. doi: 10.1111/tops.12492

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

Filippova, E. (2014). “Irony production and comprehension,” in Pragmatic Development in First Language Acquisition, ed. D. Matthews (Amsterdam, PA: John Benjamins), 261–278.

Forscher, P. S., Lai, C. K., Axt, J. R., Ebersole, C. R., Herman, M., Devine, P. G., et al. (2019). A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 117, 522–559. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000160

Fuchs, J. (2023). 40 years of research into children's irony comprehension. Pragmat. Cognit. 30, 1–30. doi: 10.1075/pc.22015.fuc

Garfinkel, S., Rowe, M. L., Bosacki, S., and Banasik-Jemielniak, N. (2024). ‘Mom said it in quotation marks!' Irony comprehension and metapragmatic awareness in 8-year-olds. J. Child Lang. 51, 485–508. doi: 10.1017/S0305000923000399

Garnham, A., Oakhill, J., and Reynolds, D. (2002). Are inferences from stereotyped role names to characters' gender made elaboratively? Mem. Cognit. 30, 439–446. doi: 10.3758/BF03194944

Gibbs, R. W. Jr., and Colston, H. L., (eds.). (2023). The Cambridge Handbook of Irony and Thought. of Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giedd, J., Blumenthal, J., Jeffries, N., Castellanos, F. X., Liu, H., Zijdenbos, A., et al. (1999). Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158

Giora, R., and Attardo, S. (2014). “Irony,” in Encyclopedia of Humor Studies, ed. S. Attardo (Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications), 397–402.

Glenwright, M., Tapley, B., Rano, J. K. S., and Pexman, P. M. (2017). Developing appreciation for sarcasm and sarcastic gossip: it depends on perspective. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 60, 3295–3309. doi: 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-17-0058

Hess, K., Avecilla-Ramírez, G., and Salinas, A. K. (2023). Theory of mind, moral development, and irony in children and adolescents. Rev. ConCiencia EPG 8, 46–69. doi: 10.32654/ConCiencia.8-2.3

Hess, K., Fernández, G., and León, A. D. (2017). Some explorations on metalinguistic reflection on verbal irony in school years. Estudios Lingüíst. Apl. 66, 9–39. doi: 10.22201/enallt.01852647p.2017.66

Hess, K., Fernández, G., and Olguín, A. (2018). Development of metalinguistic reflection on different types of ironic utterances. Signos Lingüíst. 28, 28–63.

Hess, K., Fernández, G., and Silva, A. M. (2021). ¿Para qué ironizamos? Reflexiones de adolescentes de 12 y 15 Años sobre las funciones de la ironîa verbal. E-Journal EuroAm. J. Appl. Linguist. Lang. 8, 1–19. doi: 10.21283/2376905X.13.224

Hess, K., Salinas, A. K., and Avecilla-Ramírez, G. (2022). Does the gender of those who use irony matter? Metalinguistic reflections on verbal irony in children and adolescents. Cuadernos ALFAL 34, 104–126.

JASP Team (2024). JASP (Version 0.18. 3)[Computer Software]. Amsterdam: The JASP Team. Available at: https://jasp-stats.org/faq/how-do-i-cite-jasp/

Jiménez, E. (2010). El Factor Género En El Proceso de Adquisición de Lenguas: Revisión Crítica de Los Estudios Interdisciplinares. Linred 8, 2010–2011.

Jorgensen, J. (1996). The functions of sarcastic irony in speech. J. Pragmat. 26, 613–634. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(95)00067-4

Kalbermatten, M. I. (2006). Verbal Irony as a Prototype Category in Spanish: A Discoursive Analysis (PhD dissertation). University of Minnesota, Ann Arbor, MI, United States.

Kalbermatten, M. I. (2010). “Humor in verbal irony,” in Dialogue in Spanish: Studies in Functions and Contexts, eds. D. Koike, and L. Rodríguez-Alfano (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 69–88.

Lavoie, J., and Talwar, V. (2018). Care to share? Children's cognitive skills and concealing responses to a parent. Top. Cogn. Sci. 12, 485–503. doi: 10.1111/tops.12390

Lepore, L., and Brown, R. (1997). Category and stereotype activation: is prejudice inevitable? J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 72, 275–287. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.275

Lomas, C. (2007). ¿La Escuela Es Un Infierno?: Violencia Escolar y Construcción Cultural de La Masculinidad. Rev. Educ. 342, 83–102.

Luna, B., Hess, K., Díaz, L., and Avecilla-Ramírez, G. (2023). ¿Se vale ironizar si eres niña? Un estudio electrofisiológico. Nthé Spec. Edn. 18–24.

Merino, G., and Mar, M. (2017). La Identidad de Género a Través Del Humor En Niños y Niñas de 10 Años. Círculo Lingüística Aplicada Comun. 70, 99–118. doi: 10.5209/CLAC.56319

Milanowicz, A. (2013). Irony as a means of perception through communication channels. Emotions, attitude and Iq related to irony across gender. Psychol. Lang. Commun. 17, 115–132. doi: 10.2478/plc-2013-0008

Milanowicz, A., and Kałowski, P. (2016). Zing Zing Bang Bang: how do you know what she really meant. Gender bias in response to irony: the role of who is speaking to whom. Psychol. Lang. Commun. 20, 219–234. doi: 10.1515/plc-2016-0014

Milanowicz, A., Tarnowski, A., and Bokus, B. (2017). When sugar-coated words taste dry: the relationship between gender, anxiety, and response to irony. Front. Psychol. 8:307779. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02215

Molinaro, N., Su, J. J., and Carreiras, M. (2016). Stereotypes override grammar: social knowledge in sentence comprehension. Brain Lang. 155–156, 36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2016.03.002

Nippold, M. A. (2016). Later Language Development: School-Age Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Austin: Pro-Ed.

Pexman, P. M. (2023). “Persuasive language development: the case of irony and humour in children's language,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Persuasion, eds. J. Fahnestock, and R. Allen Harris (New York, NY: Taylor and Francis), 475–487.

Pexman, P. M. (2024). “Irony and thought: developmental insights,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Irony and Thought, eds. R. W. Gibbs and H. L. Colston (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 181–196.

Pexman, P. M., Ferretti, T. R., and Katz, A. N. (2000). Discourse factors that influence online reading of metaphor and irony. Discour. Process. 29, 201–222. doi: 10.1207/S15326950dp2903_2

Rockwell, P., and Theriot, E. M. (2001). Culture, gender, and gender mix in encoders of sarcasm: a self-assessment analysis. Commun. Res. Rep. 18, 44–52. doi: 10.1080/08824090109384781

Ruiz, L., and Alvarado, M. B., (eds.). (2013). “The pragmatics of irony and humor,” in Irony and Humor: from Pragmatics to Discourse (Amsterdam; Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins), 1–13. doi: 10.1075/pbns.231

Ruiz-Gurillo, L. (2016). Metapragmatics of Humor: Current Research Trends. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Schnell, Z., and Varga, E. (2012). “Humour, irony and social cognition,” in Hungarian Humour, eds. T. Litovkina, A. Szollosy, P. Medgyes, and W. Chłopicki (Cracow: Tertium Society for the Promotion of Language Studies), 253–270.

Szücs, M., and Babarczy, A. (2017). “The role of Theory of Mind, grammatical competence and metapragmatic awareness in irony comprehension,” in Pragmatics at its Interfaces, ed. S. Assimakopoulos (Berlin; Boston, MA: De Gruyter Mouton), 129–148.

Timofeeva, L. (2017). Metapragmática Del Humor Infantil. Círc. Ling. Aplicada Comun. 70, 5–19. doi: 10.5209/CLAC.56314

Timofeeva-Timofeev, L. (2016). “Children using phraseology for humorous purposes. The case of 9-to-10-year-olds,” in Metapragmatics of Humor: Current Research Trends, ed. L. Ruiz-Gurillo (Alicante: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 273–298.

Tolchinsky, L., and Berman, R. A. (2023). Growing into Language: Developmental Trajectories and Neural Underpinnings. Oxford: Oxford Academic.

Whalen, J. M., and Pexman, P. M. (2010). How do children respond to verbal irony in face-to-face communication? The development of mode adoption across middle childhood. Discour. Process. 47, 363–387. doi: 10.1080/01638530903347635

World Medical Association (2001). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull. World Health Org. 79, 373–374. Retrieved from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/268312

Zajączkowska, M., Abbot-Smith, K., and Kim, C. S. (2020). Using shared knowledge to determine ironic intent; a conversational response paradigm. J. Child Lang. 47, 1170–1188. doi: 10.1017/S0305000920000045

Keywords: later language development, verbal irony, metapragmatic reflections, adolescents, gender

Citation: Hess Zimmermann K, Avecilla-Ramírez GN and Castillo Romo AA (2024) Metapragmatic reflections of adolescents on gender in ironic interactions. Front. Lang. Sci. 3:1452971. doi: 10.3389/flang.2024.1452971

Received: 21 June 2024; Accepted: 13 September 2024;

Published: 14 October 2024.

Edited by:

Liliana Tolchinsky, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Hassan Banaruee, University of Education Weingarten, GermanyCopyright © 2024 Hess Zimmermann, Avecilla-Ramírez and Castillo Romo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karina Hess Zimmermann, a2FyaW5hLmhlc3NAdWFxLm14

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.