95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Lang. Sci. , 08 July 2024

Sec. Bilingualism

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/flang.2024.1377977

This article is part of the Research Topic Heritage Languages at the Crossroads: Cultural Contexts, Individual Differences, and Methodologies View all 19 articles

Introduction: This paper studies the pragmatic force that heritage speakers may convey through the use of the diminutive in everyday speech. In particular, I analyze the use of the Spanish diminutive in 49 sociolinguistic interviews from a Spanish–English bilingual community in Southern Arizona, U.S. where Spanish is the heritage language. I compare the use of the diminutive in heritage Spanish to the distribution of the diminutive in the speech of a Spanish monolingual community (18 sociolinguistic interviews) from the same dialectal region. Although Spanish and English employ different morphosyntactic strategies to express diminutive meaning, the analysis reveals that the diminutive morpheme -ito/a is a productive morphological device in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Southern Arizona (i.e., similar diminutive distributions to their monolingual counterparts). While heritage speakers employed the diminutive -ito/a to express the notion of “smallness” in their Spanish-discourse, the analysis indicates that these language users are more likely to invoke a subjective evaluation through the diminutive -ito/a when talking about their family members and/or childhood experiences. This particular finding suggests that the concept “child” is the semantic/pragmatic driving force of the diminutive in heritage Spanish as a marker of speech by, about, to, or with some relation to children. The analysis further suggests that examining the pragmatic dimensions of the diminutive in everyday speech can provide important insights into how heritage speakers encode and create cultural meaning in their heritage languages.

Methods: In this study, I analyze the use of Spanish diminutives in two U.S.-Mexico border regions. The first data set is representative of a Spanish–English bilingual community in Southern Arizona, U.S., provided in the Corpus del Español en el Sur de Arizona (The CESA Corpus). The CESA Corpus comprises 49 sociolinguistic interviews of ~1 h each for a total of ~305,542 words. The second data set comprises 18 sociolinguistic interviews of predominantly monolingual Spanish speakers from the city of Mexicali, Baja California in Mexico, provided in the Proyecto Para el Estudio Sociolingüístico del Español de España y de América (PRESEEA). The Mexicali data set consists of ~119,162 words.

Results: The analysis revealed that the Spanish diminutive morpheme -ito/a is a productive morphological device in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Southern Arizona. In addition to its prototypical meaning (i.e., the notion of “smallness”), the diminutive morpheme -ito/a conveyed an array of pragmatic functions in the everyday speech of Spanish heritage speakers and their monolingual counterparts from the same dialectal region. Importantly, these pragmatic functions are mediated by speakers' subjective perceptions of the entity in question. Unlike their monolingual counterparts, heritage speakers are more likely to invoke a subjective evaluation through the diminutive -ito/a when talking about their family members and/or childhood experiences. Altogether, the study suggests that the concept “child” is the semantic/pragmatic driving force of the diminutive in heritage Spanish as a marker of speech by, about, to, or with some relation to children.

Discussion: In this study, I followed Reynoso's framework to study the pragmatic dimensions of the diminutive in everyday speech, that is, speakers' publicly conveyed meaning. The analysis revealed that heritage speakers applied most of the pragmatic functions and their respective values observed in Reynoso's cross-dialectal study of Spanish diminutives, and hence providing further support for her framework. Similarly, the study provides further evidence to Jurafsky's proposal that morphological diminutives arise from semantic or pragmatic links with children. Finally, the analysis indicated that examining the semantic/pragmatic dimensions of the diminutive in everyday speech can provide important insights into how heritage speakers encode and create cultural meaning in their heritage languages, which can in turn have further ramifications for heritage language learning and teaching.

Diminutive formation is a morphological process of word formation through suffixation, prefixation, reduplication and infixation (Grandi and Körtvélyessy, 2015). This morphological device has been characterized as a marker of speech by, about, to, or with some relation to children (Jurafsky, 1996). Diminutives are, then, a sub-class of evaluative morphology expressing at least two pragmatic dimensions: a quantitative evaluation relying on the real and objective properties of the entity in context (i.e., an object's tangible characteristics such as size or shape) and/or a qualitative evaluation involving the speaker's subjective perceptions of the referred entity (Dressler and Merlini Barbaresi, 1994; Reynoso, 2001, 2005; Grandi and Körtvélyessy, 2015). The use of the diminutive in everyday speech is, therefore, semantically and pragmatically driven where the same diminutive affix (or any other morphological device) attached to the same lexical base can express different pragmatic senses.1 For instance, the Spanish diminutive morpheme -ito attached to the lexical base chico “small” in (1a) refers to the tangible characteristics of the head noun “radio,” whereas the same morpheme conveys the speaker's subjective perception of age in (1b).2

(1a) Me acuerdo un tiempo, mi papá me compró un radio chiquito (CESA006)

I remember one time, my dad bought me a radio small-DIM

(1b) Quisiera decir que cuando yo era chiquito no teníamos celulares (CESA070)

“I would say that when I was small-DIM there were no cell phones”

The examples in (1) illustrate that contextually based inferences play a crucial role in mediating the pragmatic force that speakers wish to convey through the diminutive in everyday speech.

Current studies on diminutives in heritage bilingualism are primarily concerned with diminutive formation (El Haimeur, 2019; Vanhaverbeke and Enghels, 2021; Kpogo et al., 2023). Examining the semantic/pragmatic dimensions of the diminutive in everyday speech can provide important insights into how heritage speakers encode and create cultural meaning in their heritage languages. The present study, then, aims to provide a framework to study (i) how Spanish heritage speakers express diminutive meaning in their Spanish-discourse, (ii) the pragmatic force that heritage speakers may convey through the use of the diminutive in everyday speech compared to their monolingual counterparts from the same dialectal region, and (iii) to explore the role of sociocultural meaning unique to the heritage experience through the use of the diminutive in heritage Spanish.3 In this paper, “pragmatic force” refers to the illocutionary force of an utterance (Leech, 1983), and hence the current study aims to relate the sense of the diminutive to its pragmatic force in the everyday speech of Spanish–English bilinguals from Southern Arizona, U.S.

The present study adopts a sociolinguistic perspective to examine the use of diminutives in heritage Spanish. In particular, I analyze spontaneous speech from two U.S.-Mexico border regions. The first data set comprises 49 sociolinguistic interviews (31 female and 18 male informants) from a Spanish–English bilingual community in Southern Arizona, U.S. where Spanish is the heritage language, provided in the Corpus del Español en el Sur de Arizona (The CESA Corpus, Carvalho, 2012). The second data set comprises 18 sociolinguistic interviews (10 females, eight males) of predominantly monolingual Spanish speakers from Mexicali, Baja California, Mexico, provided in the Proyecto Para el Estudio Sociolingüístico del Español de España y de América (PRESEEA, https://preseea.uah.es/). Importantly, in the Methods section I provide evidence indicating that Spanish heritage speakers in Southern Arizona and their monolingual counterparts in Baja California are language users of the Spanish variety spoken in Northern Mexico.

Heritage bilingualism is well-documented in Southern Arizona, U.S. In particular, previous studies examining linguistic and sociolinguistic features in this bilingual community indicate that Spanish is the socio-politically minority language acquired from birth as a first language or together with English (DuBord, 2004; Casillas, 2013; Bessett, 2015; Llompart, 2016; Kern, 2017, 2020; Cruz, 2018, 2021; Fernández Flórez, 2022). That is, Spanish heritage speakers in this geographical region of the U.S. experience a short period of Spanish monolingual learning but are subsequently exposed to English during the first years of life through daycare and/or preschool. Conditions of reduced exposure and language use during late childhood can negatively affect the heritage language (Montrul, 2023), but previous studies indicate that the Spanish heritage population in Southern Arizona is highly proficient in both Spanish and English (Bessett, 2015; Kern, 2017, 2020; Cruz, 2021, 2022). Moreover, Spanish is well-represented across many social domains, including churches and supermarkets, in this geographical region of the U.S. (Jaramillo, 1995; Francom, 2012).

In this study, I adopt Reynoso's (2001, 2005) framework to study the pragmatic force that Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona and their monolingual counterparts from Mexicali, Mexico may convey through the use of the Spanish diminutive in everyday speech. In this framework, speakers can employ a pragmatic force ranging from an objective (i.e., expressing an object's tangible characteristics such as size or shape) to a subjective evaluation of the entity in question. Moreover, sociocultural norms play a crucial role in modulating the degree of subjectivity that speakers may employ when evaluating an entity in context. For example, Mexican Spanish speakers are more likely to use the diminutive to embrace sociocultural norms linked to their Mexican identity and culture (Reynoso, 2001, 2005; Company, 2002). Considering that the diminutive is a means of social interaction in child-directed speech (Melzi and King, 2003; Marrero et al., 2007), in this paper “sociocultural norms” refer to the indexical relationship between sociocultural meaning and language form, that is, how speech acts are expressed in the heritage language within and across social scales (Pinto and Raschio, 2007; Park, 2008; He, 2011).

In this section, I discuss the morphosyntactic strategies that Spanish and English employ to express diminutive meaning in relation to how the Spanish–English bilingual may express diminutive meaning in her heritage language.

There are cross-linguistic differences between Spanish and English that make the study of diminutives in heritage Spanish an intriguing one. While there are many diminutive suffixes in Spanish (-ito, -illo, -ín, -ico, -ete, -ejo, -uelo, among others), the -ito/a morpheme (i.e., carr-ito “car-DIM.MASC” and cas-ita “house-DIM.FEM') is the most productive form across the Spanish-speaking regions (Reynoso, 2001; Travis, 2004; Regúnaga, 2005; Paredes García, 2015), especially in child-directed speech (Melzi and King, 2003; Marrero et al., 2007).4 In terms of its morphological formation, the -ito/a morpheme has two allomorphs conditioned by word class (in the sense of Harris, 1991) for realization: the -ito/a allomorph attaches to word classes with a terminal element (terminal elements are -a, -o and -e) and the -cito/a allomorph attaches to words with no terminal element, that is, words that do not end in -a, -o, or -e (i.e., luz→lucecita “light-DIM.FEM”) (Colina, 2003, see also Vadella, 2017 on the syntax of diminutives in Spanish). These allomorphs can appear with most Spanish words including nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and interjections (Reynoso, 2001). The prototypical meaning of the diminutive in Spanish is the notion of “smallness,” but pragmatic values such affection, intimacy, contempt and politeness are also attributed to this semantic/pragmatic category (Travis, 2004; Mendoza, 2005; Regúnaga, 2005; Marrero et al., 2007; Eddington, 2017).

Similar to Spanish, English also has morphological devices for expressing diminutive meaning (i.e., the suffixes -y/-ie, -let and -ette) (Dressler and Merlini Barbaresi, 1994; Schneider, 2013), but this morphological strategy is limited to a set of semantic categories pertaining to animals and proper names (Sifianou, 1991; Bysrov et al., 2020). For example, in a study of English diminutives in children's books, Bysrov et al. (2020) reported 169 diminutive forms, whereby only 19 of these are morphological diminutives and 104 are analytic (or paraphrastic) diminutives of the form “little + either common or proper noun” as in little child. That is, analytic diminutives of the form “little + noun” are more prevalent than the morphological diminutive in English. In addition to expressing “smallness,” English analytic diminutives can convey positive or negative emotions, contempt, and affection, among other pragmatic values (Schneider, 2013; Bysrov et al., 2020). Similar to English, Spanish also has analytic forms to express the notion of “smallness” (i.e., pequeño or chico “little/small”), but these analytic forms are relatively infrequent in Spanish (Jurafsky, 1996), especially in heritage Spanish as I show next. In terms of diminutive formation, then, it is fair to say that English employs an analytic strategy to express diminutive meaning, whereas Spanish applies a morphological strategy for this linguistic function.

In a cross-linguistic study, Jurafsky (1996) presented empirical evidence for the claim that the origin of the morphological diminutive is the sense/concept of “child.” In Jurafsky's terms, “every case in which a historical origin can be determined for a diminutive morpheme, the source was either semantically related to “child” (e.g., a word meaning “child” or “son”), or pragmatically related to “child” (e.g., a hypocoristic suffix on names)” (1996, p. 562). Based on these observations, Jurafsky developed a universal radical category (a graphical representation) for the semantics/pragmatics of the diminutive. In this radical category, “child” is the central sense of the diminutive, and pragmatic values such as “affection” and “sympathy” are extensions of the diminutive as “a marker of speech by, about, to, or with some relation to children” (Jurafsky, 1996 p. 563). On the other hand, Jurafsky (1996) further suggested that the core meaning of analytic diminutives in languages like English is the sense “small.” That is, semantic values such as approximation (i.e., little tired) and small type (i.e., little finger) of English diminutives arise from the sense “small,” which can also convey contempt as a pragmatic value (i.e., you little-so-and-so) [see Bysrov et al. (2020) for more pragmatic values of English analytic diminutives, though it is not clear whether the concept “child” is the pragmatic source of the pragmatic functions reported in Bysrov et al. (2020)]. In Jurafsky's proposal, then, morphological diminutives in languages like Spanish convey pragmatic values attributed to the central sense/concept “child,” whereas English analytic “little + noun” expresses semantic/pragmatic values arising from the sense “small.” In short, Spanish and English employ different morphosyntactic strategies arising from different semantic senses to express diminutive meaning.

Considering these cross-linguistic differences in bilingual contexts, a crucial question arises: what diminutive strategies do Spanish–English bilinguals employ to express diminutive meaning in their two languages? This question concerns, on the one hand, the everyday use of the Spanish morphological diminutive (i.e., -ito/a, or other suffixes) compared to its analytic counterpart pequeño or chico “little,” and, on the other hand, the use of English analytic diminutives (i.e., “little”) compared to its morphological counterpart (i.e., the suffixes -y/-ie). A bilingual corpus where Spanish–English bilingual informants freely alternate between their two languages throughout their spontaneous conversations would be the ideal data source to test out these predictions. The Bangor Miami Corpus (Deuchar, 2008) provides a first insight into the question that concern us here.

The Bangor Miami Corpus (Deuchar, 2008) consists of 56 spontaneous Spanish–English bilingual conversations involving 84 informants who lived in Miami, Florida, U.S. at the time of the data collection, for a total of 35 h of recorded conversation. The bilingual practices of this bilingual community are well-documented in the literature (Fricke and Kootstra, 2016; Valdés Kroff, 2016; Vanhaverbeke and Enghels, 2021). In an analysis of Spanish and English diminutives in this corpus, Vanhaverbeke and Enghels (2021) found that, in their Spanish-discourse, Spanish–English bilinguals produced the morphological strategy (i.e., -ito/a) at an 88.57% (527/595) rate compared to a 11.43% (68/595) rate for its analytic counterpart (i.e., pequeño “small').5 In their English-discourse, on the other hand, the same bilinguals produced the English analytic strategy at an 86.15% (255/296) rate compared to a 13.85% (41/296) rate for its morphological counterpart. Interestingly, the diminutive morpheme -ito/a represented 91.08% (480/527) of the morphological strategy applied in Spanish-discourse, while English “little” represented 89.01% of the analytic strategy in English-discourse. When these morphological/analytic strategies were further analyzed for their pragmatic function, Vanhaverbeke and Enghels reported that these bilinguals used English analytic diminutives to express real and objective properties of the entity in question (a quantitative value), while the same bilinguals used the Spanish morphological strategy to convey a qualitative evaluation based on the speaker's subjective perception of the entity in context.6

While the diminutive category is a productive morphological device for expressing diminutive meaning in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Miami, diminutive formation (a morphological process) has in fact been reported to be a challenging feature in heritage languages in contact with English. For example, Kpogo et al. (2023) noted that Twi and English use a morphological strategy (i.e., diminutive morpheme) and an analytic strategy to express diminutive meaning, but Twi speakers prefer the morphological strategy, whereas English speakers prefer the analytic one (similar to the Spanish–English contrast discussed above). In an experimental study, Kpogo et al. (2023) then investigated the linguistic strategy that second-generation (G2) Twi speakers in the U.S. preferred compared to the strategy preferred by first-generation (G1) Twi speakers. They found that G2 Twi heritage speakers preferred the analytic over the morphological strategy to express the notion of “smallness” in heritage Twi, whereas the G1 Twi speakers exhibited the opposite preference. The authors suggested that the complexity of linguistic options for expressing diminutive meaning in Twi combined with cross-linguistic influence at the level of preferences can explain Twi heritage speakers' preferences for the analytic over the morphological strategy in heritage Twi (see also El Haimeur, 2019 for similar findings for diminutive formation in heritage Moroccan Arabic in France).

Summarizing, Vanhaverbeke and Enghels' (2021) analysis of the Bangor Miami Corpus indicates that Spanish–English bilinguals from Miami resorted to the morphosyntactic strategies of their two respective languages to express diminutive meaning in bilingual contexts. Moreover, and similar to other Spanish-speaking regions in non-contact situations, the diminutive morpheme -ito/a is the most productive morphological device in their Spanish-discourse conveying “affective” pragmatic values. On the other hand, Twi heritage speakers in the U.S. preferred the analytic over the morphological strategy to express diminutive meaning in their heritage language, while G1 Twi speakers preferred the morphological strategy in this language. A possible explanation for the preference of the morphological over the analytic strategy in the Bangor Miami Corpus is the possibility that these bilinguals were, more likely than not, exposed the morphological strategy early in their language learning trajectory because diminutives are a salient feature of child-directed speech. Twi heritage speakers in the U.S., on the other hand, may experience a different language learning trajectory (i.e., more English exposure during childhood) compared to the Spanish heritage population and this could explain the preference for the analytic strategy in heritage Twi, although only experimental data has been reported for the Twi heritage population in the U.S. The studies discussed in this section provide important insights into diminutive formation in heritage bilingualism, but the pragmatic force that heritage speakers may convey through the use of the diminutive in everyday speech remains unexplored territory. The present study aims to fill this gap in the literature.

Jurafsky's (1996) universal structure for the semantics/pragmatics of the diminutive is primarily based on historical empirical evidence, that is, it does not concern the everyday use of diminutives. While the pragmatic extensions of the central sense “child” in this universal structure can be studied independently for any language, a framework that can capture the pragmatic force of the diminutive as a collective force deriving from the speaker's subjective evaluation of the entity in context is desirable. I believe Reynoso's (2001, 2005) framework offers a promising approach to studying the pragmatic force that heritage speakers wish to convey through the use of the diminutive in everyday speech. It should be noted that Jurafsky's (1996) proposal for the semantics/pragmatics of the diminutive and Reynoso's framework to study the everyday use of the diminutive should be conceived as two frameworks that can complement each other, rather than two different frameworks examining the same linguistic phenomenon.

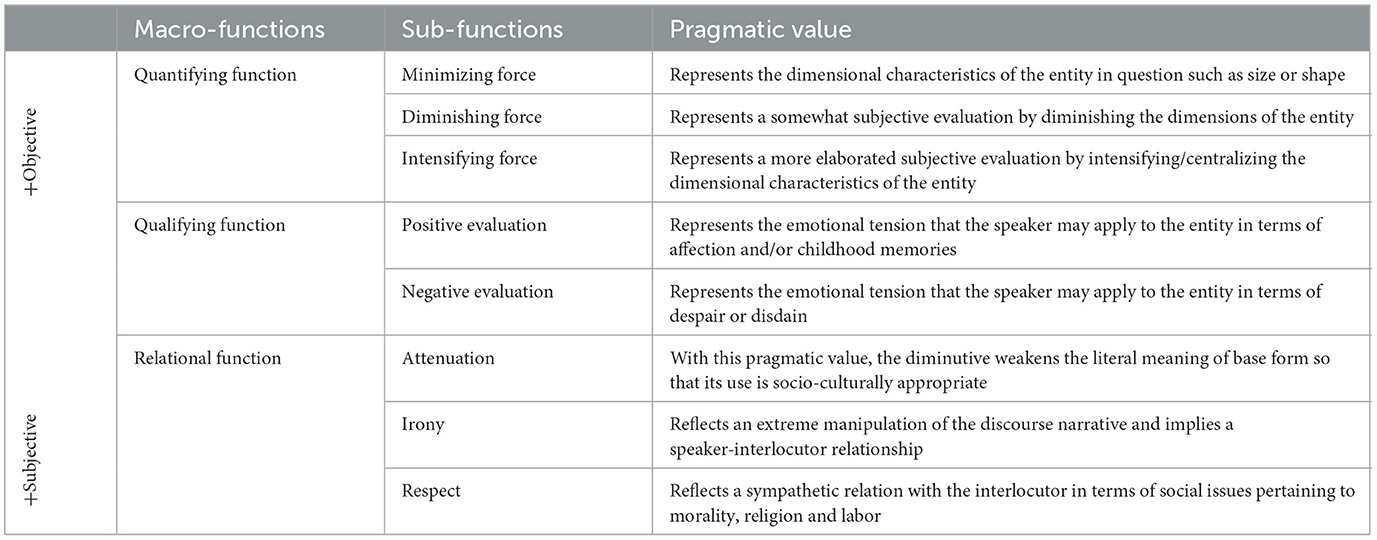

In a study of Argentine, Andean, Peninsular and Mexican Spanish, Reynoso (2001) found that historical events (i.e., colonization) and sociocultural norms motivate the presence or absence of the diminutive in these Spanish-speaking regions. In particular, Reynoso emphasized that some Spanish-speaking regions, but not others, exploit diminutive morphology to manifest sociocultural norms unique to a speech community (i.e., attenuating negative or positive events in life such as death or fortune), which in turn leads to higher frequency of the diminutive in these communities. Based on these observations, she developed a framework to study the pragmatic force of the Spanish diminutive across the Spanish-speaking regions included in her study. Reynoso (2001) identified three pragmatic functions in her cross-dialectal data, which together make a continuum ranging from an objective to an extremely subjective conceptualization of the entity in question, as illustrated in Table 1.7

Table 1. Pragmatic functions of the Spanish diminutive based on Reynoso (2001, 2005).

At the objective end of the spectrum (+objective) in Table 1, the speaker can apply a QUANTIFYING function that involves almost no subjective evaluation of the entity in question, but rather a purely objective evaluation where the use of the diminutive refers to an entity's tangible characteristics such as size and shape. For example, in (2a) the diminutive form -ita is used to express the dimensional characteristics of a physical object.8 Within the QUANTIFYING function in Table 1, the speaker can further “diminish” or “intensify/centralize” her evaluation by invoking a certain degree of subjectivity. For instance, in (2b), the speaker applies the diminutive form -ita to the lexical base cosa “thing” to diminish the canonical meaning of “dinner.”

(2a) el chofer no sé por qué decidió estacionarse en la pura orillita de un cerro (CESA004)

‘the driver, I don't know why he decided to park right by the edge-DIM of a hill'

(2b) Y la cena, pues cenan muy liviano, algo, cualquier cosita (CESA016)

“As for dinner, well they eat very light, like, any-thing-DIM really”

When the speaker applies the QUALIFYING function in Table 1, s/he invokes a greater degree of subjectivity to conceptualize the entity in question and assigns a positive or negative pragmatic value to this evaluation. Importantly, sociocultural norms play a crucial role in determining the positive/negative pragmatic value of the speaker's evaluation. For example, grandparents and children are often conceived as family members that deserve affection in Mexican culture (Reynoso, 2001), and other cultures as well. Thus, the use of the diminutive is likely to express a positive value when referring to children or grandparents as illustrated in (3a), but a negative value when the speaker expresses despair or anger about other human beings (3b), or any other entity in general.

(3a) Desde que se murieron mis abuelitos no regreso [a México] (CESA013)

‘Since my grandparent-DIM.PL died I haven't returned [to Mexico]'

(3b) Conozco a una cubana, a una cubanita por ahí que no sé. Nunca le he caído bien (CESA013)

“I know a Cuban, a Cuban-DIM.FEM somewhere that I am not sure (of what she thinks of me). I have never gotten along with her”

At the other end of the spectrum in Table 1, the speaker can apply the RELATIONAL function, which involves the maximum degree of subjectivity by manipulating the discourse or expressing respect toward entities that are highly respected in a speech community such as religious figures like God or Virgen Mary. With this pragmatic function, the speaker establishes a relationship with the interlocutor who must be able to decode the pragmatic force of the diminutive; if the speaker believes the interlocutor cannot decode this pragmatic force, s/he would not apply such force to the diminutive in first place. Similar to the QUALIFYING function, sociocultural norms play a crucial role in the RELATIONAL function as illustrated in (4), where the interlocutor presumably understands what woman-like behavior looks like.

(4) y jugaba allá a las muñecas y así. XY es muy diferente, es más mujercita (CESA016)

“and she would play with dolls and things like that. XY [girl's name] is different, she is more woman-like-DIM”

Reynoso's (2001) work revealed that speakers across all four Spanish varieties included in her study applied the pragmatic functions and their respective pragmatic values illustrated in Table 1. Interestingly, the Andean and Mexican varieties, which represent the mestizo population in Reynoso's study, applied the pragmatic functions that involve a more subjective evaluation more frequently than the Peninsular and Argentine Spanish varieties. Based on these results, Reynoso (2001, 2005) suggested that sociocultural norms are particularly relevant for the use of the diminutive in Mexican and Andean Spanish. More recent studies have also adopted Reynoso's framework to study the pragmatic force of the Spanish diminutive in other Spanish-speaking regions and have provided further support for this framework (Paredes García, 2015; Słowik, 2017; Malaver and Paredes García, 2020).

Thus, I believe that Reynoso's (2001, 2005) framework is suitable for studying the pragmatic force that Spanish heritage speakers wish to convey through the use of the diminutive in their heritage language. In the next section, I provide some empirical evidence indicating that Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona and their monolingual counterparts from Mexicali, Mexico are language users of the Spanish variety spoken in Northern Mexico. I further compare the use of the diminutive in heritage Spanish to their monolingual counterparts in Mexicali to tease out sociocultural norms unique to each speech community. The next section presents the methodology of the present study.

Considering that Spanish and English employ different morphosyntactic strategies arising from different semantic senses to express diminutive meaning as described above, this study addresses the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What is the relative frequency of the Spanish morphological diminutive compared to its analytic counterpart in the Spanish-discourse of Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona?

RQ2: What pragmatic force do heritage speakers from Southern Arizona convey through the use of the morphological diminutive in their Spanish-discourse and how does it compare to their monolingual counterparts from the same dialectal region?

RQ3: What role do sociocultural norms unique to the heritage experience play in the everyday use of Spanish diminutives in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Southern Arizona?

In this study, I analyze the use of Spanish diminutives in two U.S.-Mexico border regions. The first data set is representative of a Spanish–English bilingual community in Southern Arizona, U.S., provided in the Corpus del Español en el Sur de Arizona (The CESA Corpus, Carvalho, 2012). The CESA Corpus is an on-going research project directed by linguist Ana M. Carvalho and aims at documenting and disseminating Spanish varieties spoken in Arizona, U.S., which borders with the state of Sonora in Mexico. At the time of the data collection, the CESA informants lived, worked and/or studied in Tucson, Arizona, U.S, which has a population of 542,629 habitants, 42.17% of whom identify as Hispanic or Latino (United States Census Bureau, 2020). According to the 2020 Census data, 69.2% of Tucson's habitants speak English at home and 26.1% speak Spanish. Although English is the majority language spoken in Tucson, Arizona, Spanish is well-represented across different social domains in this bilingual community, including the church and supermarkets (Jaramillo, 1995; Francom, 2012).

Currently, the CESA Corpus consists of 78 sociolinguistic interviews of ~1 h each. The sociolinguistic interviews archived in this corpus were carried out by graduate and undergraduate students, the researcher included, who were trained in conducting a sociolinguistic interview following Labov (1972) protocol (Bessett et al., 2024). In particular, informants were asked about childhood memories, current social issues at their local community, and questions about language use in their communities and within their families, among other questions. The interviews were conducted in Spanish, but informants were encouraged to freely alternate between languages if they wished to. The CESA informants provided demographic information about themselves and their parents.

Only 49 of the existing 78 sociolinguistic interviews in the CESA Corpus are included in the present study. The remaining interviews were excluded because (i) informants were born or raised in Mexico, (ii) the interview lacks informant's language background information, or (iii) the informant did not produce any instances of the target token; two informants who were born in Mexico but raised in the U.S. from childhood are included in the 49 total sample because their bilingual profile is not different from that of informants born in the U.S. All the informants included in the current sample were raised in Southern Arizona, mainly in the cities of Tucson and Phoenix, and all of them lived in Tucson at the time of the data collection. The CESA data set analyzed here consists of ~305,542 words.

The second data set comprises 18 sociolinguistic interviews of predominantly monolingual Spanish speakers from the city of Mexicali, Baja California in Mexico, which borders with the state of California in the U.S. side and the state of Sonora in the Mexican side of the border. These sociolinguistic interviews are provided in the Proyecto Para el Estudio Sociolingüístico del Español de España y de América (PRESEEA, https://preseea.uah.es/), a large research project coordinated by the University of Alcalá in Spain. This project aims at documenting the speech of Spanish speakers who live and work in urban settings across the Spanish-speaking regions (Moreno-Fernández, 2005). Similar to the CESA Corpus, the PRESEEA Corpus follows a sociolinguistic interview protocol for data collection. The interviews analyzed here include informants' demographic information, including sex, age, and level of education. These interviews are ~40 min long and were conducted by a team of sociolinguists at the Autonomous University of Baja California in Mexico. All the informants lived and worked in the city of Mexicali in Mexico at the time of the data collection. The Mexicali data set consists of ~119,162 words.

Spanish speakers in these two U.S.-Mexico border regions are representative language users of the Northern variety of Mexican Spanish. For instance, Bessett (2015) analyzed the use of variable copula estar “to be” (i.e., estar occurring in contexts where one would normally expect the use of copula ser “to be”) in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Southern Arizona compared to variable copula estar in the speech of Spanish monolinguals from the state of Sonora, Mexico. Bessett's study revealed that Spanish heritage speakers (or bilinguals in his terms) exhibited similar usage patterns to their monolingual counterparts from the state of Sonora, Mexico regarding the extension of variable estar: i.e., 20.8% for heritage speakers from Southern Arizona vs. 16.2% for monolinguals from Sonora, Mexico. Similarly, the implementation of the diagraph “ch” as either an affricate [t∫] or a fricative [∫] is a key phonetic feature of Northern Mexican Spanish (López Velarde and Simonet, 2019), and Casillas (2012) found that Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona also produced this phonetic variation in their Spanish-discourse. Finally, it is important to mention that Spanish speakers from Baja California, Mexico have positive attitudes about bilingualism and the U.S. culture in general (Rábago et al., 2008). It is therefore fair to suggest that the informants in the present study are language users of the same Spanish variety.

Bilingual informants from the CESA Corpus are 31 females and 17 males ranging between the ages of 18 and 55 (M = 25.08; SD = 7.80), while those from the Mexicali corpus are 10 females and 8 males ranging from 21 to 68 (M = 46.11; SD = 16.77) years old. Bilingual informants completed a bilingual language profile (BLP) questionnaire adopted from Birdsong et al. (2012). They reported acquiring both Spanish (M = 1.97; SD = 1.56 years-old) and English (M = 3.57; SD = 2.01 years-old) relatively early in life and assigned themselves overall high proficiency in speaking, listening, reading and writing for both Spanish (M = 4.61; SD = 0.01) and English (M = 4.45; SD = 0.01) as shown in Table 2. Most bilingual informants reported to use both Spanish and English on a regular basis with friends, family and at school/work (see Table 2). Furthermore, 41 of the 49 bilingual informants have a parent who was born in Mexico, and most of them (n = 47) have visited Mexico at least once and/or have close family in Mexico (n = 39). That is, Mexican heritage is an important factor for this bilingual sample. And thus, our bilingual sample is representative of heritage Spanish speakers who were immersed in a bilingual experience from early on in life and have high fluency in the heritage language (i.e., Valdés, 2005). While the Mexicali corpus does not provide data on informants' linguistic profiles, the interviews indicate that these speakers are predominantly monolingual in Spanish (i.e., some informants explicitly state in the interviews that they only speak Spanish).

Every interview from the CESA and Mexicali corpora was carefully analyzed for the target token, both audio and the written text of the interviews were considered. Target tokens (diminutives) were coded for the following parameters in both data sets:

(a) Diminutive suffix: -ito, -illo, -ín, -ico, -ete, -ejo, -uelo

(b) Allomorph of the -ito/a morpheme: -ito/a and -cito/a

(c) Word category: noun, verb, adjective, adverb or interjection

(d) Lexicalization: lexicalized form vs. pragmatic force

(e) Pragmatic force: the macro-pragmatic functions in Table 1 and their respective pragmatic values

(f) Semantic sense: child sense vs. small sense

Every diminutive token that conveyed a pragmatic force was coded according to Reynoso's (2001, 2005) framework in Table 1. In the coding procedure, the macro-pragmatic functions in Table 1 were determined on the basis of the degree of subjectivity that the speaker applied when using the diminutive in context. Speaker's intentions (i.e., what kind of pragmatic force is the speaker conveying through the diminutive) further helped us determine the sub-functions (pragmatic values) in Table 1. The researcher carefully analyzed the context where the diminutive occurred to determine the pragmatic force for each diminutive token in both corpora. It is important to mention that the researcher is a language user of Mexican Spanish and participated in the data collection of the CESA Corpus while living in the community. Next, I provide examples from the CESA Corpus to illustrate each of the pragmatic values in Table 1.

Within the QUANTIFYING function in Table 1, which is more objective than subjective, the speaker can “minimize,” “diminish,” or “intensify/centralize” the pragmatic force of the diminutive in a given context. For example, in (5a) the diminutive “minimizes” the dimensional characteristics of the entity in question, whereas in (5b) it “diminishes” the prototypical meaning of the referred entity where palabritas implies “irrelevant words.” The speaker can also intensify/centralize the prototypical meaning of a base form, as illustrated in (5c) where the diminutive morpheme attaches to the adjective exacto “exact” that expresses a precise measure or idea. The diminutive in (5c), then, intensifies or centralizes the meaning of the adjective exacto.

(5a) El dedo se le cortó y lo tenía colgando como por un hilito (CESA021)

‘He cut his finger and it was hanging by a string-DIM'

(5b) A ella nunca le hablo en inglés. Nunca, nada más palabritas (CESA045)

I never speak English to her. Never, just little word-DIM.PL.

(5c) Así como lo tiene ella [el pelo], así exactito (CESA041)

‘the way she has it [the hair], like that exact-DIM'

Importantly, note that the speaker's evaluation is maximally objective in (5a), but it involves a degree of subjectivity in (5b) and (5c) because the speaker deliberately chooses to diminish or intensify the meaning of the base form, respectively. The examples in (5), then, illustrate the QUANTIFYING function and its respective pragmatic values in the coding system adopted here.

Unlike the QUANTIFYING function, the QUALIFYING function in Table 1 involves a greater degree of subjectivity and can trigger a positive or a negative value as illustrated in examples (6a) and (6b), respectively.

(6a) Ay me encantaba ir a México porque era en el campo o sea mis abuelitos eran campesinos

“I loved going to Mexico because it was in the countryside, I mean, my grandparent-DIM-PL were peasants” (CESA009)

(6b) Usualmente la gente [risa] con los carritos más feitos…son la gente más especial (CESA021)

“Usually, people who have ugly-DIM.PL car-DIM-PL…are more especial”'

In a positive evaluation, the speaker applies the diminutive to express affection toward something or someone as clearly demonstrated in (6a). The example in (6b) further illustrates that a subjective evaluation can also trigger a negative value, that is, the speaker uses the diminutive forms carritos “car-DIM-PL” and feitos “ugly-DIM.PL” in (6b) to express his/her annoyance about clients' complaints. Similarly, a positive evaluation can also be conveyed when referring to institutions that deserve respect or places that trigger nostalgia as illustrated in (6c), where use of the possessive pronoun mi “my” indicates that the speaker feels nostalgia toward his/her hometown, which could in fact be much bigger than the prototypical size of a small town.

(6c) Me acuerdo de mi pueblito porque así se veía (CESA036)

‘I remember my hometown-DIM because it looked just like that'

In short, the examples in (6a)–(6c) illustrate how the diminutive form can convey a positive or negative subjective evaluation in the everyday speech of Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona.

The RELATIONAL function in Table 1 involves the maximum degree of subjectivity, namely because this function conveys pragmatic values that are socio-culturally sensitive in the sense that some cultures are more likely to buffer positive or negative events in society through the use of the diminutive (Reynoso, 2001, 2005; Company, 2002). Another key feature of this pragmatic function is the manipulation of discourse, that is, the speaker assumes that the interlocutor is part of the speech community who will be able to decode the pragmatic force assigned to the diminutive. For instance, in (7a) the speaker applies the diminutive to attenuate the speaker's perception that s/he is becoming of age. The use of the adjective vieja “old” instead of its diminutive form can be interpreted as a face-threatening act, and so the speaker applied the diminutive in (7a) to buffer the reality of becoming of age. In fact, the interlocutor may very well compliment the speaker's youth-looking as a way of adhering to the community's sociocultural norms (i.e., in a society that privileges young-looking).

(7a) ya me estoy haciendo viejita (CESA018)

“I am getting old-DIM already”

(7b) Pues agarré una idea bien, bien suave…se me prendió el foquito (CESA022)

“I had a very, very cool idea. I had an aha-DIM moment”

In (7b) the speaker uses the diminutive form to explain his/her aha moment. The speaker further presumes that the interlocutor will be able to decode this idiomatic expression. And thus, (7b) is an example of the “irony” value in Table 1 because the speaker engages the interlocutor in decoding the meaning of the diminutive form. Reynoso's (2001, 2005) study further revealed that speakers can apply the diminutive to express respect for religious figures or events (i.e., Diosito “God-DIM”), but there are no instances of this pragmatic value in either the CESA or the Mexicali corpora.

In order to test RQ1 in the CESA Corpus, I further analyzed all 49 sociolinguistic interviews for the use of the adjectives pequeño and chico “little/small.” Moreover, recall that Jurafsky (1996) proposed that morphological diminutives arise from the sense “child,” whereas the meaning of analytic diminutives stems from the sense “small.” Therefore, I also explored the pragmatic dimensions that the analytic forms pequeño and chico may convey in their diminutive form (i.e., chiquito/a). And thus, the parameter “semantic sense” above refers to whether the use of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a attached to the adjectives pequeño and chico denotes the tangible characteristics of the entity in question (“size sense”) or conveys the speaker's subjective perception of age and/or childhood experience (“child sense”).

A final note is in order to highlight the fact that some instances of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a do not convey a pragmatic force in the speech of heritage speakers or their monolingual counterparts. In other words, there are some lexicalized tokens of the diminutive in both data sets. Any instance of the diminutive that does not convey a pragmatic value was excluded from further analysis. Excluded tokens are food labels (8a) and continuous repetitions of a particular diminutive form (8b); in (8b), for example, the speaker used the diminutive form pueblito “town-DIM” early in the interview and throughout the interview when referring to the place where s/he was born.

(8a) Las alitas, me encantan las alitas (CESA031)

‘Wings, I love wings'

(8b) Yo nací: en un pueblito que se llama Morenci Arizona (CESA036)

‘I was born in a town-DM called Morenci Arizona'

In the Supplementary material that go along with this paper, the reader has access to the entire data sets where s/he can see the pragmatic value assigned to each target token in both corpora as well as all instances of the analytics pequeño and chico in the CESA Corpus.

As shown in Table 1, speakers' choice of the diminutive involves a continuum ranging from an objective to a subjective evaluation with three categories: a quantifying, a qualifying and a relational function. Multinomial logistic regression is then well-suited as an analytical tool to explore speakers' use of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in everyday speech. This statistical tool tests the probability or risk of being in a given category or level compared to other categories (Hilbe, 2009). Similar to logistic regression with a binary dependent variable, multinomial regression relies on log-odds ratios of the predictor variables for interpretation, providing direct analysis of a choice between two values of the dependent variable (Rosemeyer and Enrique-Arias, 2016; Fahy et al., 2021). Importantly, multinomial regression specifies one level of the dependent variable as the reference value (the baseline), and thus a fitted model “calculates the log odds of the other levels of the dependent variable relative to this reference value” (Fahy et al., 2021, p. 205). In multinomial regression, the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumption states that characteristics of one particular choice alternative do not impact the relative probabilities of choosing other alternatives, and can be tested employing the Hausman-McFadden test (Hilbe, 2009).

For the purpose of the present study, multinomial regressions were carried out using the multinom() function within the “nnet” R package (Ripley and Venables, 2023) in the statistical software application R (R Core Team, 2021). Since the “nnet” package does not provide built-in tests for the Hausman-McFadden test, I tested the IIA assumption using the mlogit package for R (Croissant, 2020). Following Hilbe (2009) suggestion, I checked the IIA by estimating the full model and then fitting a model reduced by a level (category) and employing the Hausman-McFadden test of IIA. As mentioned above, this study probes speakers' objective vs. subjective use of the diminutive, and so I tested the IIA assumption for the quanti(fying) and the quali(fying) subset of alternatives. The Hausman-McFadden test indicated that there is no violation of the IIA assumption for this subset of alternatives [χ2(3) = 0.068, p = 0.995].

Since the IIA is valid, I fitted a multinomial regression using the multinom() function to analyze speakers' use of the quanti(fying), quali(fying), and rela(tional) functions, which represent the dependent variable. In this model, the quanti(fying) function served as the reference value because this particular function expresses speaker's more objective use of the diminutive, and so speakers' more subjective use of the diminutive are compared against a more objective use. In other words, the model will identify the log-odds ratios of using the quali(fying) function over the quanti(fying) function and of using the rela(tional) function over the quanti(fying) function, based on the influence of the predictor variables. Corpus (heritage vs. monolingual) and informants' sex (female vs. male) are the predictor variables. In building this first model, I ran an “intercept-only model” (a model with no predictors) and then fitted a model for the predictors. The fitted model was significantly different from the intercept-only model [χ2(4) = 21.13, p = 000; AICfinalmodel = 1526.66; AICnullmodel = 1539.79], which confirmed that the final model is more parsimonious. I checked variance inflation factors (VIFs) for corpus = 1.35 and sex = 1.73, which confirmed that these predictors are not correlated. For a better interpretation of the model's coefficients, coefficients were transformed into probabilities using the package “effects” within R (Fox et al., 2019).

I ran a second multinomial regression using the multinom() function to explore whether Spanish proficiency modulates heritage speakers' use of the diminutive. For this second model, Spanish proficiency was coded for “mid” and “high” proficiency based on informants' self-reported proficiency in the bilingual language profile (BLP) questionnaire reported in Table 2. In this questionnaire, bilingual informants were asked to self-rate their Spanish proficiency on a scale of 0 to 6 for speaking, listening, reading, and writing. The ratings in Table 2 indicate that informants' overall Spanish proficiency across these four language skills ranged from 3.25 to 6 points. Consequently, informants who scored 5 and above for Spanish proficiency in the BLP (n = 25) were classified as the “high” proficiency group, and those who scored below 5 average points (n = 24) were classified as “mid” proficiency groups. Similar to the first model, this second model included speakers' use of the quanti(fying), quali(fying), and rela(tional) functions in Table 1 as the dependent variable, with quanti(fying) as the baseline. Spanish proficiency is the predictor variable. The same statistical tools used in the first model were applied to the second model to test the IIA assumption of multinomial regression. The Hausman-McFadden test indicated that there is no violation of the IIA assumption for the subset of alternatives [χ2(2) = −4304.3, p = 1].

In building this second model, I first ran a model with no predictors and then fitted a model with Spanish proficiency as a predictor. The fitted model was not significantly different from the intercept-only model [χ2(2) = 1.83, p = 0.40; AICfinalmodel = 1106.38; AICnullmodel = 1104.21]. The data files and the scripts used for these analyses are available at Open Science Framework (OSF: https://osf.io/m5gu8/).

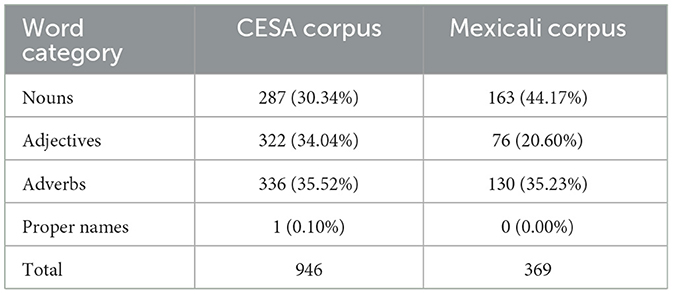

The analysis revealed a total of 946 diminutive tokens in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Southern Arizona and a total of 369 diminutive tokens in the Mexicali corpus. While the diminutive suffixes -illo/a (n = 12) and -ín (n = 1) were observed in the Mexicali corpus in addition to -ito/a, only the morpheme -ito/a was observed in the speech of heritage speakers. All diminutive tokens were further classified into their word category as reported in Table 3 for both corpora.

Table 3. Overall frequency of Spanish diminutives in the CESA Corpus and the Mexicali Corpus by word category.

As we can see in Table 3, diminutive morphology is well-represented across nouns, adjectives, and adverbs in both corpora. Recall that the diminutive morpheme -ito/a has two allomorphs in Spanish, namely -ito/a and -cito/a. There are 20 instances of the -cito/a allomorph in the CESA Corpus, and one of these tokens appeared with the unexpected word class, that is, the lexical base banco “stool” would normally take the -ito/a allomorph, and not -cito/a as applied in (9). As for the Mexicali corpus, there are 26 instances of the -cito/a allomorph, and all occurred with the expected word class.

(9) Cuando yo lavo los trastes, ella agarra su banquecito y me ayuda (CESA006)

‘When I wash the dishes, she gets her stool-DIM and helps me'

Interestingly, one bilingual informant also applied the diminutive morpheme -ito/a to English-origin words as illustrated in (10).

(10a) Y luego me agarré un Jeepesito, un nineteen ninety (CESA031)

“And then I bought a Jeep-DIM, a nineteen ninety”

(10b) Un muchacho que se pone unos shortsitos así y que anda enseñando el cuerpo

“A guy who wears some short-DIM-PL like that and is showing off his body” (CESA031)

As mentioned in the previous section, there are some diminutive tokens that do not convey a pragmatic force in the data sets analyzed here. These include food labels, continuous repetitions of a diminutive form, and proper names for a total of 29 tokens in the CESA Corpus and 3 tokens in the Mexicali corpus, all excluded from further analysis. In addition, a careful analysis of the adverb ahorita and its variant horita “now-DIM” indicates that this diminutive form encodes primarily the meaning “at the present moment” in both corpora as illustrated in following examples.

(11a) De hecho ahorita estoy hablando mejor que hace un mes porque he estado en una clase de español (CESA047)

‘In fact, right now-DIM I am speaking better than I did a month ago because I have been in a Spanish class'

(11b) Y ahorita apenas acabo de ver que están haciendo el tren (MXLI_H22_015)

‘And right now-DIM I saw that they are building the train'

According to Reynoso (2001) and Malaver and Paredes García (2020), when attached to the adverb ahora “now,” the diminutive form -ito/a augments the immediateness of the event being described or narrated. In Reynoso's (2001, 2005) framework adopted here, the “immediateness” pragmatic force of ahorita falls within the intensifying/centralizing value of the QUANTIFYING function in Table 1. However, Reynoso (2001) also noted that ahorita seems to be losing its intensifying force in Mexican Spanish, and she suggested that the duplication of the diminutive (i.e., ahoritita “now-DIM”) can serve as a testing ground to tease out whether ahorita conveys a pragmatic force or functions as a lexicalized form; duplication would presumably express the intensifying force of the diminutive. Indeed, ahorita is a very frequent form in the corpora analyzed here (248 tokens in the CESA Corpus and 106 in the Mexicali corpus), but there are no instances of diminutive duplication with ahorita in either corpora. In other words, we cannot carry out Reynoso's duplication test to delimit the pragmatic force of ahorita “now-DIM” in the data sets that concern us here. And thus, ahorita and its variant horita were excluded from further analysis in the present study.

The final data sets examined for the pragmatic force that heritage speakers and their monolingual counterparts wish to convey through the use of the diminutive consists of 669 diminutive tokens in the CESA Corpus (n = 49 informants) and 260 tokens in the Mexicali corpus (17 informants, one of the 18 informants in the initial data set produced lexicalized forms only). Of the 669 total diminutive tokens in the CESA Corpus, 57.55% (385) were produced by female bilingual informants and 42.45% (284) by male bilingual informants; similarly, 56.15% (146) were produced by female and 43.85% (114) by male informants in the Mexicali corpus.

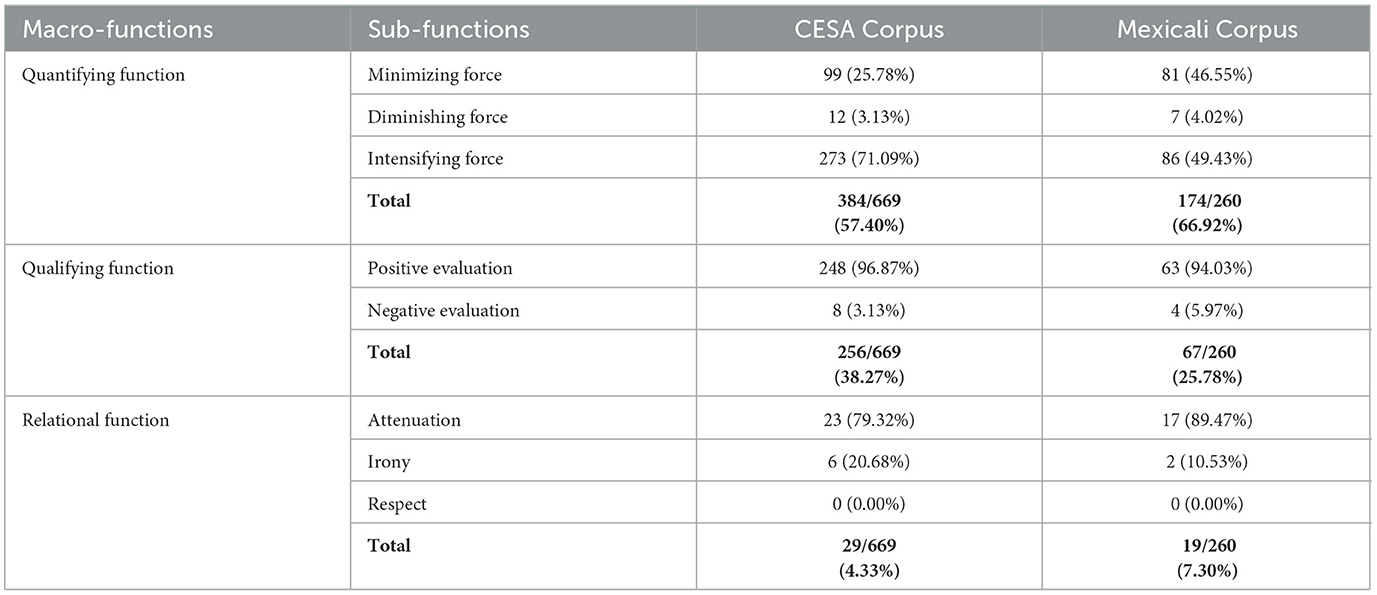

Table 4 reports the relative frequencies of the macro-functions and their respective pragmatic values found in the heritage corpus and the monolingual corpus.

Table 4. Percentages of pragmatic functions of the Spanish diminutive in the CESA Corpus and the Mexicali corpus.

The analysis revealed that heritage speakers and their monolingual counterparts employed most of the pragmatic values reported in Table 1; the “respect” pragmatic value is the only missing value in both corpora. In particular, the quantifying function represents 57.40% (384/669) of the heritage corpus and 66.92% (174/260) of the monolingual corpus. Within this function, the “minimizing force,” which involves an objective evaluation, is well-represented in the heritage corpus (25.78%) but is more prevalent in the monolingual corpus (46.55%). Similarly, the “intensifying force,” which centralizes the dimensional characteristics of the referred entity by invoking a certain degree of subjectivity from the speaker's perspective, is the most prevalent pragmatic force with a 71.09% (273/384) rate in the heritage corpus and a 49.43% (86/174) rate in the monolingual corpus. On the other hand, the “diminishing force” is relatively infrequent in both corpora (3.13% in the heritage corpus and 4.02% in the monolingual corpus). It should be noted, however, that several diminutive forms are very frequent in the quantifying function; for instance, there are 137 tokens of the adverb poquito/a “little,” 28 tokens of the adverb cerquita(s) “near-DIM” and 17 tokens of adjective chiquito/a “small-DIM,” which together represent 66.66% (182/273) of the total tokens in the “intensifying force” within the quantifying function in the heritage corpus as illustrated in Table 4.

The qualifying function in Table 4 represents 38.27% (256/669) of the heritage corpus and 25.78% (67/260) of the monolingual corpus. Within this function, a “positive evaluation” is overwhelmingly preferred (96.87%) over a “negative evaluation” (3.13%) in the heritage corpus and a similar pattern is observed in the monolingual corpus. The relative frequencies of the “positive evaluation” in Table 4 include 50 tokens of the diminutive form abuelito/as “grandparent-DIM” and 114 tokens of the diminutive chiquito/a “small-DIM,” which together represent 66.12% (164/248) of this pragmatic value within the qualifying function in the heritage corpus as illustrated in Table 4. Paredes García (2015) pointed out that “negative evaluations” within the qualifying function are relatively infrequent in sociolinguistic interviews because the interviewee may not feel comfortable sharing “negative evaluations” with the interviewer because they may not know each other.

Finally, the relational function, which involves the maximum degree of subjectivity from the speaker's perspective, represents only 4.33% (29/669) of the heritage corpus and 7.30% (19/260) of the monolingual corpus. Within this function, the “attenuating” force is more frequent than the “irony” force in both corpora. By employing the “attenuating” force, the speaker aims to buffer the literal meaning of the base form to be socio-culturally appropriate/acceptable.

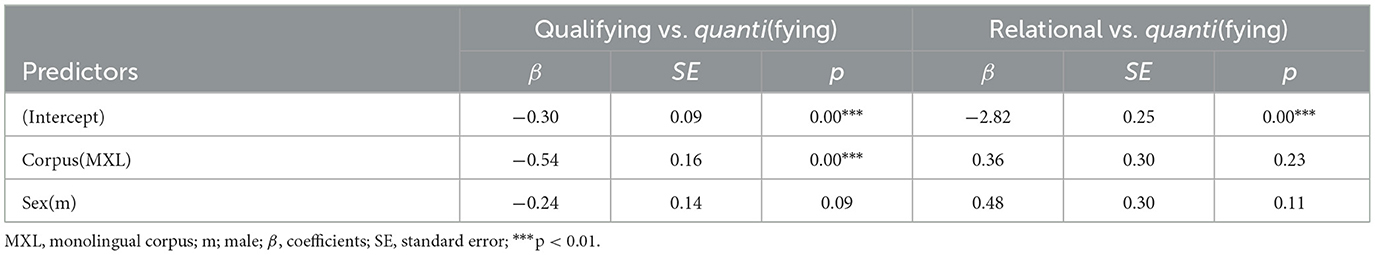

In order to draw statistical inference on the use of the diminutive across heritage speakers and their monolingual counterparts as per RQ2, I ran a multinomial logistic regression as described in the Analysis section of this paper. The fitted model identified the log-odds ratios of using the quali(fying) function over the quanti(fying) function and of using the rela(tional) function over the quanti(fying) function, based on the influence of the predictor variables. The “sign” and “magnitude” of the model coefficients indicate the direction and relative size, respectively, of the influence of a particular predictor variable on the dependent variable.

Table 5 reports the multinomial regression model coefficients for the corpus (heritage vs. monolingual) and informants' sex (female vs. male) predictors, where the quanti(fying) value is the baseline. In this model, the intercept log odds indicate that the probability of using the qualifying function over the quantifying function decreases by 0.30 (SE = 0.09) in the overall data set, which is a statistically significant decrease according to a z-test at p < 0.05 significance level. Similarly, the probability of using the relational function over the quantifying function decreases by 2.82 (SE = 0.25), which is also statistically significant as illustrated in Table 5. In other words, heritage speakers and their monolingual counterparts are significantly more likely to use a quantifying function over the relational or the qualifying function when employing the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in their everyday speech.

Table 5. Summary of multinomial logistic regression model for speakers' subjective evaluations of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a.

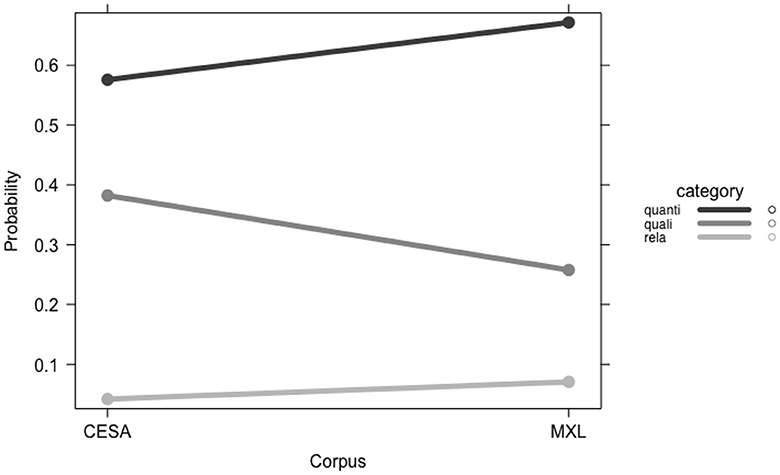

As for the predictors, the log-odds ratios (coefficient estimates) of the qualifying function occurring in place of the quantifying function (the baseline) decreased by 0.54 (SE = 0.16) in the monolingual corpus relative to the heritage corpus, a compassion that is statistically significant. On the other hand, the log-odds ratios of the relational function occurring in place of the quantifying function increased by 0.36 (SE = 0.30) in the monolingual corpus relative to the heritage corpus, a comparison that is not statistically significant as shown in Table 5. In other words, compared to the baseline value, heritage speakers are significantly more likely to apply a more subjective use of the diminutive (the qualifying function) relative to their monolingual counterparts, whereas monolingual speakers are more likely to apply a more objective use of the diminutive relative to their heritage counterparts, although this last comparison is not statistically significant as shown in Table 5. Figure 1 provides a visual illustration of these findings via predicted probabilities. In the next section, I explain the implications of this particular finding in relation to RQ2 of this paper.

Figure 1. Corpus effect plot for predicted probabilities across the macro-functions quanti(fying), quali(fying) and rela(tional).

As for informants' sex, the log-odds ratios of the qualifying function occurring in place of the quantifying function (the baseline) decreased by 0.24 (SE = 0.14) for male informants relative to female informants, a compassion that is not statistically significant, p = 0.09. On the other hand, the log-odds ratios of the relational function occurring in place of the quantifying function increased by 0.48 (SE = 0.30) for male informants relative to female informants, a comparison that is not statistically significant either, p = 0.11. In other words, informants' sex did not play a role in determining speakers' selection of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in their everyday speech.

As pointed out in the previous section, I ran a second multinomial model to explore whether Spanish proficiency modulates heritage speakers' selection of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in their Spanish-discourse. Bilingual informants were divided into “mid” and “high” proficiency based on their self-reported Spanish proficiency in the BLP questionnaire. Table 6 reports the coefficients for this second model. In this model, which includes the heritage speakers' data only, the log-odds ratios (coefficient estimates) of the qualifying function occurring in place of the quantifying function (the baseline) increased by 0.11 (SE = 0.16) for the “mid” proficiency group, a compassion that is not statistically significant, p = 0.49. On the other hand, the log-odds ratios of the relational function occurring in place of the quantifying function decreased by 0.45 (SE = 0.44) for the “mid” proficiency group, a comparison that is not statistically significant either, p = 0.31. In fact, it should also be noted that the fitted model was not significantly different from the intercept-only model. The analysis, then, indicated that, regardless of their proficiency in Spanish, heritage speakers apply a similar degree of subjectivity when using the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in their Spanish-discourse.

Table 6. Summary of multinomial logistic regression model for Spanish proficiency in modulating heritage speaker's use of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a.

A final note on the use of the analytic forms pequeño/a and chico/a is in order here. In particular, there are 33 instances of pequeño/as and 52 instances of chico/as in the heritage corpus, and 61.17% (52/85) of these expresses speakers' perception of age in relation to childhood experiences as illustrated in (12), and the remaining 38.83% refers to size or quantity of the referent.

(12a) So era casi igual como cuando yo estaba chica (CESA001)

‘So it was almost the same when I was little-FEM'

(12b) Me acuerdo que cuando estábamos pequeñas teníamos un Nintendo (CESA016)

‘I remember that when we were small-FEM we had a Nintendo'

Interestingly, the analysis further revealed that the diminutive counterpart (i.e., chiquito/as) of the analytic “chico” represents 26.15% (175/669) of the heritage corpus, and 67.42% (118/175) of these diminutive forms express the sense “child” as illustrated in (13a); the remaining 57 instances (or 32.58%) of the diminutive form chiquito/as refers to the referent's size or shape. There are only two instances of the diminutive form pequeñito/a in the heritage corpus and both refer to size or shape. On the contrary, the diminutive form chiquito/as represents only 7.30% (19/260) of the monolingual corpus, and 68.42% (13/19) of these expresses the sense “child” as illustrated in (13b); there are no tokens of the pequeñito/as form in the monolingual corpus. In short, the diminutive form chiquito/a is more prevalent in the speech of heritage speakers relative to their monolingual counterparts from the same dialectal region.

(13a) Cuando estaba chiquita era un [sic] tradición de ir a México (CESA023)

‘When I was mall-DIM it was a tradition to go to Mexico'

(13b) Nunca me han gustado [las películas de terror] de chiquita me dan pánico

‘I have never liked them [horror movies], never since I was little-DIM (MXLI_M21_050)

Summarizing, the study revealed that the diminutive morpheme -ito/a is a productive morphological device is the Spanish-discourse of Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona, whereas its analytic counterparts pequeño and chico are relatively infrequent in the everyday speech of this heritage community. The analysis further showed that the diminutive is a polysemous category conveying an array of pragmatic forces in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers and their monolingual counterparts from the same dialectal region. In particular, heritage speakers are significantly more likely to apply a more subjective use of the diminutive involving positive attitudes toward family members and/or childhood experiences. This positive perception is evident in the use of the diminutive form chiquito/a whose semantic core is the sense “child.” In the next section, I provide a possible interpretation of the results and their implications for the study of diminutives in heritage bilingualism.

In this paper, I highlighted that the Spanish language employs a morphological strategy to express diminutive meaning, whereas English prefers an analytic strategy. Following Jurafsky's (1996) universal structure of the semantics/pragmatics of the diminutive, I further emphasized that different semantic senses mediate these morphosyntactic strategies: the morphological strategy is semantically and pragmatically linked to the concept “child,” whereas the sense “small” is the semantic/pragmatic source of the analytic strategy. Importantly, only the concept “child,” but not “small,” can trigger pragmatic values such as “affection” and “sympathy” as extensions of the diminutive as a marker of speech by, about, to, or with some relation to children. Given these cross-linguistic differences, the present study examined how Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona, U.S. express diminutive meaning in their Spanish-discourse.

In particular, the current study examined the relative frequency of the morphological diminutive (i.e., -ito/a, or other suffixes) compared to its analytic counterparts pequeño and chico “little/small” in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers (RQ1). Excluding lexicalized items, heritage speakers produced 669 morphological diminutives conveying an array of pragmatic forces and 85 analytic forms (pequeño and chico “small”) expressing speakers' perceptions of an entity's size and/or age. As per RQ1, then, the results revealed that the diminutive morpheme -ito/a is a productive morphological device in the everyday speech of Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona. For example, the relative frequency of the diminutive -ito/a in the heritage corpus yielded similar frequencies across all the grammatical categories attested in the monolingual corpus (see Table 3). Interestingly, heritage speakers produced only the diminutive morpheme -ito/a, whereas other diminutive suffixes were observed in the speech of their monolingual counterparts from the same dialectal region. Moreover, the morphological diminutive chiquito/a, which is the counterpart of the analytic form chico, represents 26.15% (175/669) of the heritage corpus, and 67.42% (118/175) of these diminutive forms express the sense “child.” In short, the results indicated that Spanish heritage speakers overwhelmingly preferred the morphological strategy over its analytic counterpart in their Spanish-discourse.

RQ2 further explored the pragmatic force of the morphological diminutive in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Southern Arizona compared to their monolingual counterparts from the same dialectal region. In order to address this question, I followed Reynoso's (2001, 2005) framework in which speakers can employ a pragmatic force ranging from an objective to a subjective evaluation of the entity in question. The analysis revealed that heritage speakers and their monolingual counterparts applied most the pragmatic values attested in Reynoso's (2001) cross-dialectal study of the Spanish diminutive. As we can see in Table 4, the analysis indicated that these groups exhibited a similar distribution of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in their everyday speech. First, the quantifying function in Table 1 includes the notion of “smallness,” which is often taken to represent the prototypical meaning of the diminutive in Spanish (Eddington, 2017). The present analysis then suggests that Spanish heritage speakers from Southern Arizona maintain the prototypical meaning of the Spanish diminutive in their heritage language—though their everyday use of this prototypical meaning is less frequent compared to their monolingual counterparts (i.e., 25.78% vs. 46.55%, respectively). In this sense, heritage speakers maintain the semantics/pragmatics of the Spanish diminutive morpheme -ito/a, but the heritage experience triggers a greater degree of subjectivity in relation to family members and/or childhood experiences as I explain next.

In particular, a multinomial logistic regression revealed that heritage speakers are significantly more likely to apply a more subjective use of the diminutive (i.e., more likely to apply the qualifying function compared to the quantifying function) compared to their monolingual counterparts. As we can see in Table 1, the qualifying function involves a positive or a negative evaluation. The analysis showed that heritage speakers conveyed a positive rather than a negative evaluation through the use of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a. In particular, within the qualifying function, heritage speakers employed the morpheme -ito/a primarily to convey affection or endearment toward family members, including grandparents, siblings, cousins, and nephews and nieces. Moreover, heritage speakers applied the diminutive morpheme -ito/a to retrieve childhood experiences through the use of the diminutive form chiquito/a. These findings support Jurafsky's (1996) claim that morphological diminutives arise from the central sense “child,” which can in turn trigger pragmatic values such as “affection” and “sympathy.” In other words, the present analysis suggests that the concept “child” motivates the everyday use of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers as a marker of speech by, about, to, or with some relation to children.

In terms of speakers' sex (gender), there is no statistical significance between male and female speakers, suggesting that both groups exhibited similar distributions of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a across the objective-subjective continuum in Table 1. A second multinomial regression further showed that Spanish proficiency did not modulate heritage speakers' degree of subjectivity applied in using the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in their everyday speech.

The third RQ further explored the role of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in promoting cultural meaning related to the heritage experience in the Spanish-discourse of heritage speakers from Southern Arizona. In Reynoso's (2001, 2005) framework, sociocultural norms can exert the degree of subjectivity that speakers employ through the use of the diminutive. Reynoso further suggested that the relational function, which involves the maximum degree of subjectivity, is the pragmatic function that best captures how speakers manifest sociocultural norms unique to a speech community. In fact, the relational function occurred at a 21.28% (792/3,271) rate in Reynoso's corpus of Mexican Spanish, and the use of the diminutive manifested sociocultural norms linked to speakers' Mexican identity and culture. However, the reader may recall that the relational function is relatively infrequent in both the heritage (4.33%) and the monolingual (7.30%) corpora analyzed here. Instead, heritage speakers invoked a maximum degree of subjectivity to convey affection toward their family members and to retrieve childhood memories through the use of the diminutive morpheme -ito/a, two crucial factors in heritage language learning (Carreira and Kagan, 2011; Leeman, 2015; Xiao-Desai, 2019; Dubinina, 2021). Although more research is needed in terms of the linguistic forms that encode cultural meaning in heritage languages (see Park, 2008 for heritage Korean in the U.S.), the present analysis suggests that the diminutive morpheme -ito/a can be a promoter of cultural meaning in the heritage community studied here. The fact that the morpheme -ito/a is the only diminutive suffix observed in this speech community supports this suggestion.

While we do not have data from the kind of input that the heritage population studied here received during child language learning, child studies indicate that the diminutive morpheme -ito/a is the most productive form used by parents and their children in child-directed speech (Melzi and King, 2003; Marrero et al., 2007). Since most of the heritage speakers in the present study experienced a period of Spanish monolingual learning in the first years of life (see Table 2), it is likely that they were primarily exposed to the diminutive morpheme -ito/a during childhood. If so, sociocultural meaning linked to the heritage experience (i.e., how to interact with their Spanish-speaking grandparents and other relatives) was further instilled during the process of being socialized in the heritage language, and continued to expand in a bilingual context. It followed that the diminutive morpheme -ito/a eventually became the community norm in this speech community to the point that these language users did not adopt other diminutive suffixes to express diminutive meaning in their heritage language, even when they are exposed to other diminutive suffixes through interactions with monolingual speakers from Mexico because of the constant flow of people between Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora. In this sense, the diminutive morpheme -ito/a maintains its core semantic sense “child,” but its everyday use (or its pragmatic dimensions) has been conventionalized in this speech community to convey primarily speakers' subjective perceptions about their heritage language experience, which includes their Mexican heritage and growing up bilingual (Leeman, 2015).

In this study, heritage speakers from Southern Arizona employed the diminutive morpheme -ito/a in their Spanish-discourse to convey affection toward their family members. However, it should be noted that Aaron (2015) showed that Spanish–English bilinguals from New Mexico were more likely to use English-origin kinship terms such as grandma and daddy in their Spanish-discourse instead of the Spanish equivalents of these kinship terms (i.e., abuelito/a).9 Aaron further suggested that English-origin kinship terms “serve specific, locally determined discourse functions that have been conventionalized within this community” (p. 476). Aaron's study and the present study suggest that bilingual communities in the U.S. may employ different linguistic strategies to manifest community norms linked to the heritage (bilingual) experience. Moreover, Vanhaverbeke and Enghels' (2021) analysis of the Bangor Miami Corpus showed that Spanish–English bilinguals from Miami produced other diminutive suffixes in addition to the diminutive morpheme -ito/a, which is the only form observed in the heritage corpus in the present study. Finally, Kpogo et al. (2023) experimental study indicated that Twi heritage speakers in the U.S. exhibited different morphosyntactic strategies to express diminutive meaning compared to first generation Twi speakers.

These studies highlight the importance of studying diminutive formation and the semantic/pragmatic dimensions of the diminutive in heritage bilingualism as well as how heritage speakers encode and generate sociocultural meaning in their heritage languages. Future studies can adopt a similar framework to the one developed here to explore whether the concept “child” is the core sense of the diminutive in other heritage communities and the pragmatic (or illocutionary) force that these communities assign to the diminutive morpheme in their everyday speech. This line of research could shed new light on the diversity of pragmatic norms in heritage bilingualism, including speech acts (Pinto and Raschio, 2007; Elias, 2015; Bar On and Meir, 2022; Avramenko and Meir, 2023) and discourse/pragmatic markers (Park, 2008; Kern, 2014, 2017).