95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Lang. Sci. , 02 February 2023

Sec. Psycholinguistics

Volume 2 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/flang.2023.1043619

Introduction: Previous aesthetic research has set its main focus on visual and auditory, primarily music, stimuli with only a handful of studies exploring the aesthetic potential of linguistic stimuli. In the present study, we investigate for the first time the effects of personality traits on phonaesthetic language ratings.

Methods: Twenty-three under-researched, “rarer” (less learned and therefore less known as a foreign language or L2) and minority languages were evaluated by 145 participants in terms of eroticism, beauty, status, and orderliness, subjectively perceived based on language sound.

Results: Overall, Romance languages (Catalan, Portuguese, Romanian) were still among the top six erotic languages of the experiment together with “Romance-sounding,” but less known languages like Breton and Basque. Catalan and Portuguese were also placed among the top six most beautiful languages. The Germanic languages (Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, and Icelandic) were perceived as more prestigious/higher in terms of status, however to some degree conditioned by their recognition/familiarity. Thus, we partly replicated the results of our earlier studies on the Romance language preferences (the so-called Latin Lover effect) and the perceived higher status of the Germanic languages and scrutinized again the effects of familiarity/language recognition, thereby calling into question the above mentioned concepts of the Latin Lover effect and the status of Germanic languages. We also found significant effects of personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness) on phonaesthetic ratings. Different personality types appreciated different aspects of languages: e.g., whereas neurotics had strong opinions about languages' eroticism, more conscientious participants gave significantly different ratings for status. Introverts were more generous in their ratings overall in comparison to extroverts. We did not find strong connections between personality types and specific languages or linguistic features (sonority, speech rate). Overall, personality traits were largely overridden by other individual differences: familiarity with languages (socio-cultural construals, the Romanization effect—perceiving a particular language as a Romance language) and participants' native language/L1.

Discussion: For language education in the global context, our results mean that introducing greater linguistic diversity in school and universities might result in greater appreciation and motivation to learn lesser-known and minority languages. Even though we generally prefer Romance languages to listen to and to study, different personality types are attracted to different language families and thus make potentially successful learners of these languages.

What is it that makes us find certain objects and sounds aesthetically appealing? Previous research has presented various approaches showing that aesthetic experience can be affected by diverse factors, such as structure, transparency, homogeneity, insight and simplicity (Von Kutschera, 1988; Reber et al., 2004; Sarasso et al., 2020), perception and diversity (Brandstätter, 2008; Brinck, 2018), or evolutionary (Zaidel et al., 2013), and social aspects, i.e., customs (Reber et al., 2004; Pandelaere et al., 2009; Chattaraman et al., 2010), or additional background information (e.g., Cleeremans et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Belfi et al., 2021). But maybe beauty is in the eye of the beholder: several studies have demonstrated that our sense of beauty might be also guided by personal characteristics, namely differences in personality (Child, 1965; Afhami and Mohammadi-Zarghan, 2018).

The most prominent theoretical model of personality is the Five-Factor model (the ‘Big Five') by Costa and McCrae (1985) that features five personality traits: extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience. Nettle (2007) presents an overview of these personality traits and their most prominent characteristics (Table 1).

Based on Costa and McCrae (1985) and Nettle (2007), the different personality traits and also personality types can be specified in the following way:

Extraversion: The factor of extraversion defines whether an individual is particularly outgoing and enjoys social contact or not. Individuals with high levels of extraversion—in contrast to individuals with low levels of extraversion who are therefore rather introverted—are thought to be very talkative, active, like to be the center of attention and are also more likely to thoroughly appreciate eroticism and romance. In addition to that, individuals with higher levels of extraversion also tend to feel positive emotions more easily but also more persistently and more intensely (Nettle, 2007, p. 82–84).

Neuroticism: The level of neuroticism affects how individuals experience different emotions. Individuals with high levels of neuroticism are prone to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety, worry, shame, guilt, disgust, or grief, far more strongly. This yields a difference in the attribution process of failure. Higher levels of neuroticism therefore cause individuals to find the reason for failure in themselves and to think that they are out of luck. As a result, high levels of neuroticism can also cause a predisposition for depression and a lack of self-confidence (Nettle, 2007, p. 104–121).

Conscientiousness: The level of conscientiousness is mostly concerned with the concept of impulse control and represents goal-orientedness and perseverance. Individuals with higher levels of conscientiousness are highly disciplined, seem to have less problems focusing on their individual goals and are less likely to be distracted. A high level of conscientiousness also helps to prevent making unfavorable decisions (Nettle, 2007, p. 141–142).

Agreeableness: The individual level of a person's agreeableness mostly affects social behavior and interactions and therefore determines one's interpersonal relationships. Individuals with high levels of agreeableness are thought to be highly cooperative, empathetic, trustful, affectionate, compliant, and helping. They also hardly feel anger and are altruistically oriented, humble, and gentle (Nettle, 2007, p. 162–170).

Openness to experience: An individual's level of openness to experience is considered to not only account for the willingness to expose one's own to the unknown, but also to determine for example cultural and artistic interest as well as (at least to some extent) intellect (Nettle, 2007, p 183–185). So, individuals with high levels of openness to experience are thought to be rather interested in culture and arts but also more likely to be well-educated.

Afhami and Mohammadi-Zarghan (2018) conducted a study investigating the effect of these personality traits on aesthetic judgements and art interest. The authors tested 253 university students from Tehran, Iran, with a mean age of 24.4 years (SD = 5.5). Participants took the Big-Five personality test and also were measured on their aesthetic expertise and familiarity with art-related topics. The background information such as sex, age, education, weekly art activities, and emotional stability were also taken into account. Afhami and Mohammadi-Zarghan showed that openness to experience predicted aesthetic expertise with more open participants enjoying visual arts more (Afhami and Mohammadi-Zarghan, 2018).

Similar research questions were asked in the study conducted by Greenberg et al. (2022), but this time concerning the experience of music. They conducted two studies investigating the effects of personality on the preference for certain styles of music with 284,935 participants in study 1 (57% females, 43% males) and 71,714 participants in study 2 (51% males, 48% females, 1% transgender or other). In these two studies, music styles were categorized into the following groups: “Mellow music (featuring romantic, slow, and quiet attributes as heard in soft rock, RandB and adult contemporary genres), Unpretentious (uncomplicated, relaxing, and unaggressive attributes as heard in country genres), Sophisticated (inspiring, complex, and dynamic features as heard in classical, operatic, avant-garde, and traditional jazz genres), Intense (distorted, loud, and aggressive attributes as heard in classic rock, punk, heavy metal, and power pop genres), and Contemporary (rhythmic, upbeat, and electronic attributes as heard in the rap, electronica, Latin, and Euro-pop genres)” (Greenberg et al., 2022, p. 287). Participants were asked to complete both a music preference test, namely the STOMP-R (Rentfrow and Gosling, 2003), and a personality test displaying a short overview of the individual levels of the Big Five personality traits, namely the TIPI (Gosling et al., 2003). Dwelling on the data the authors gathered they report a number of correlations summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Significant correlations between music styles and personality (Greenberg et al., 2022).

The most important discovery was not so much that personality traits were correlated with musical preferences in consistent and robust patterns but that it was a universal trend stretching out across 53 countries.

While the vast majority of studies focused on the aesthetic impressions of art (Ramachandran and Hirstein, 1999; Joy and Sherry, 2003; Bahrami-Ehsan et al., 2015; Myszkowski and Zenasni, 2016) or music (Vuust and Kringelbach, 2010; Reuter and Oehler, 2011; Brattico et al., 2013; Starcke et al., 2019), the studies that investigate the aesthetic judgements of linguistic stimuli are rare. Meanwhile, languages are routinely subjected to aesthetic judgments by the general public. There is almost universal agreement that Italian, Spanish, and French are appealing and melodious languages to the human ear (Burchette, 2014; Gasperetti, 2014). Yet, it is still a matter of debate if such preference is due to the sociocultural aura (associated culture and speakers of these languages) or it has to do with the languages' inherent properties.

The idea that some languages are evaluated more positively than others because of their linguistic (usually phonological) features such as pitch, isochrony or syllabic structure was introduced in the 70s as the inherent value hypothesis (Giles et al., 1974, 1979). The imposed norm hypothesis states that language attitudes have much to do with the speakers and the listeners of the judged languages rather than the language sound shape (Giles et al., 1974). Whereas, there is a substantial body of research investigating the imposed norm hypothesis [e.g., the work of Devyani Sharma, most recently Sharma et al. (2022)], the number of studies evaluating the theoretical validity of the imposed norm hypothesis is rather limited. Rabanus (2003) compared German and Italian alongside several phonological features (percentage of open and CV syllables, consonantal clusters, and vocalic share) with the pre-mediated assumption that German sounds less pleasant than Italian. His analysis demonstrated that German has a higher degree of syllabic variance with complex combinations, including consonant clusters, which makes this language sound rough or harsh. On the contrary, Schüppert et al. (2015) found only a weak connection between language attitudes and the properties of the evaluated languages. They investigated the attitudes of Danish and Swedish children and adolescents toward each other's languages. They concluded that the development of language attitudes relates to establishing one's identity and defining oneself and others, and is therefore closely associated with the group of listeners who judge the language, rather than with the languages per se. Chand (2009) supports this perspective: she explains language attitudes with pre-existing cultural stereotypes that we associate with the speakers of these languages or linguistic varieties. She argues that the global linguistic capital and social authority of a language's speakers are the most important factors in determining whether it is considered beautiful or not.

It is, however, entirely likely that phonaesthetics behave similarly to music, which is generally believed to be determined by both cultural and language inherent factors (Madden, 2014). Reiterer et al. (2020) measured phonaesthetics judgments of 16 European languages (including the celebrated Romance languages such as French, Italian, and Spanish) and found that although familiarity with languages (sociocultural factor) contributed to participants' judgments, endogenous linguistic properties such as language average sonority index and syllable structure also influenced participants' phonaesthetic decisions. In the follow up study, Kogan and Reiterer (2021) further reported that differences in judgements of the same 16 European languages were affected by music-like phonetic features such as pitch and rhythm with fast and flat (composed pitch) Romance languages leading the list (the Latin lover effect). On the other hand, the characteristics of the listener also mattered, namely the distance between the native language of the listener and the languages of the experiment, the number of foreign languages spoken, and musicality and singing ability. One factor these studies did not account for was differences in listeners' personality. Considering the growing body of research on the effects of personality on aesthetic judgment it seems important to include this variable to the equation. Investigating the contribution of personality sends us back to the imposed norm hypothesis (language attitudes are influenced by non-linguistic properties). The ideal scenario would be to capture the full picture: linguistic and non-linguistics factors.

Understanding the stereotypes that underlie the formation of language attitudes is an important endeavor. The situation in which a person is judged based on how pleasant their language sounds might have unfavorable social consequences (e.g., the inaccessibility of adequate medical care, housing, or employment). While not all stereotypes are harmful—after all, they are simply generalizations that can be statistically accurate and even helpful at times—some stereotypes are misconceptions that should be subjected to careful scrutiny, especially when they result in “linguistic self-hatred” (i.e., being ashamed of one's language; Giles and Niedzielski, 1998). Another practical application of the phonaesthetics research is in the foreign language classroom. Regardless of the nature of perceptual experiences that people have when listening to the sounds of foreign languages, such experiences have the potential to accompany and reinforce the process of second language acquisition. The moment one starts learning a new language, they get exposed to new phonaesthetic experiences. Enjoying the melody of a new language might activate additional affective learning pathways in the learner's brain and support auditory memory. Neuropsychological studies show that emotional events are remembered better than neutral events, thanks to the amygdala, which enhances the function of the medial temporal lobe memory system (Dolcos et al., 2004). Teachers can use the acoustic properties of the language-to-be-learned and complement the classroom work with synesthetic activities that emphasize specific phonological features (Wrembel, 2010).

The present study employs a new set of 23 European languages which are less prominent in linguistic research outside the countries where these languages are spoken, namely Albanian, Basque, Breton, Catalan, Czech, Danish, Estonian, Finnish, Greek, Hungarian, Icelandic, Irish, Latvian, Maltese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovene, Swedish, Turkish, Ukrainian, and Welsh (Table 3). This decision was motivated by an attempt to control and reduce the familiarity effect that strongly influenced participants' decisions in our previous studies (Reiterer et al., 2020; Kogan and Reiterer, 2021) and to capture the contribution of other variables to phonaesthetic judgments. Another important reason why we decided to use lesser-researched languages was to promote linguistic diversity and draw attention to the European languages outside the celebrated English-French-Spanish triad. Some of the languages in this study are minority languages and spoken by small communities of speakers, with a few languages facing the threat of extinction (e.g., Breton). In the case of Breton, the present political mood has been energetically undermining Breton, causing this language to practically vanish. As can be seen in Table 3, there are few speakers of Breton resisting the trend, with some of them tirelessly fighting for their mother tongue to survive and to be passed on. In order to raise awareness and support such lesser-researched languages, this experiment was designed featuring languages which might be unknown at least to some extent to many European participants. In presenting the sound of these languages in our experiment (still available under www.phonaesthetics.de), we hope to encourage the general public to consider these languages as part of their linguistic education and perhaps even start to learn them to raise the speaker numbers. We believe that every language can be perceived as aesthetic in its own way.

Some languages of the experiment (e.g., Greek, Portuguese, Turkish), although undoubtedly not minority languages in any sense, are seldomly acquired as foreign languages around the world and could be considered “minority” L2s. Our original expectations were that these languages would have a lower recognition rate in comparison to well-established in a school curriculum Spanish or French. However, this was not the case—the finding we will discuss later in this paper.

With this new linguistically diverse stimulus set, the aim of the current study is to explore if variance in phonaesthetic impressions, i.e., the experience of perceiving languages as pleasant sounding or not, is, among other factors, determined by personality traits. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical study investigating the effect of personality on the aesthetic judgements of linguistic stimuli. Based on previous personality research (Nettle, 2007; Bowling et al., 2011; Carleton, 2016; Proverbio et al., 2018), we expect extraverts to appreciate languages more in terms of their eroticism and beauty as opposed to other aesthetic dimensions (orderliness/well-structuredness and social status). Higher levels of neuroticism most likely trigger lower ratings overall across all phonaesthetic dimensions as neurotic individuals are susceptible to negative emotions, skepticism, and depression. Higher conscientiousness, characterized by order and discipline, would be associated with higher ratings for orderliness (how consistent or well-structured a particular language is) and status. Higher levels of agreeableness would yield in ratings consistent with common stereotypes, such as the erotic Romance languages (Catalan, Portuguese, and Romanian in our experiment), since more agreeable individuals often follow trends and like to be in sync with the prevailing opinion. Lastly, high levels of openness would lead to higher ratings for languages more distant from the native language due to openness to new experiences and curiosity.

We had 145 participants: 106 females, 37 males, and 2 participants identifying as other gender. Figure 1 shows the distribution of participants' age. Our oldest participant was born in 1948, while our youngest participant was born in 2009, leading to a range of 61 years. 74% of participants were between the ages of 21 and 40.

Furthermore, our participants showed a diverse sample in terms of foreign languages spoken, with most participants being self-proclaimed multilinguals and speaking up to 10 languages with a mean of 4.89 (SD = 1.96, min = 1, max = 10). Figure 2 illustrates the number of spoken languages in a pie chart. Predictably, English was the most common foreign language to speak, followed by German, Spanish, and French. In addition to that, we had a sample of participants having various native languages, as can be seen in Figure 3.

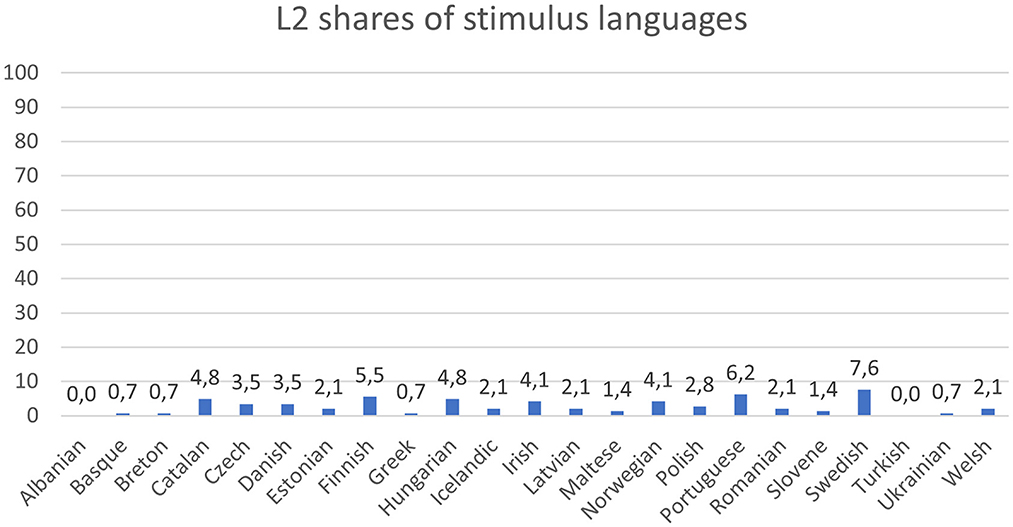

With 27 participants it was the case that their native language was among the stimulus languages, which caused us to exclude their ratings from the analysis. To illustrate the low rate of these L1 cases, this is equivalent to 0.8% of all experimental cases (27 out of 3,480). In 91 cases (2.6% of all cases) a language that served as a stimulus in this experiment had been learned as a foreign language by a participant (Figure 4). These ratings were also removed to prevent the familiarity bias.

Figure 4. Percentage of participants who spoke a particular language of the experiment as a foreign language (mean = 2.7% over all languages).

The language recordings which were displayed as stimuli in the experiment consisted of 46 recordings, two for each language to control for the effect of voices. Every participant listened to one voice for each language, so 23 recordings per participant. Forty four of these 46 recordings were recorded at the University of Vienna's MediaLab belonging to the Faculty of Philological and Cultural Studies. We recorded native speakers of each language, except for Breton. Native speakers of this language were hard to find in Vienna, so we had to rely on recordings sent to us by native speakers from Brittany (recorded at Radio Kreiz Breizh, http://www.rkb.bzh/). Reiterer et al. (2020) reported that in their experiment female voices were preferred by both male and female participants. For that reason, we only recorded female voices for the present study.

Each of the recordings was normalized with respect to volume. We used Aesop's fable The Northwind and the Sun, translated to the experiment languages by specialists. The voice-overs were instructed to speak slowly and in a friendly way, but also as naturally as possible using a variety of language which is close to standard. The most crucial issue we had to face in the process of collecting standard variety texts was the case of Breton. Many different dialects exist in Brittany with no such thing as a standard variety holding true for the entire region, and the existing smaller regional dialects differ strongly from each other. As a consequence, we had to decide on one of these dialects. The text was translated specifically for us and our experiment by Mark Kerrain, who also translated the Harry Potter series into the Breton language.

As stated above, in order to reduce the influence on the ratings caused by knowledge of the languages, some of the languages were less-known or minority languages. The selection of languages is shown in Table 3.

The experimental design consisted of two subparts, namely the language rating experiment designed based on the pilot study conducted by Reiterer et al. (2020), and secondly, the Big Five personality test which is freely available online, under https://www.truity.com/test/big-five-personality-test. This personality test is based on the Five-Factor model (the “Big Five”) by Costa and McCrae (1985) and displays the individual levels of the respective personality traits in percentages. Therefore, participants needed to fill in the online questionnaire consisting of 60 test items. These items, such as e.g., I have a kind word for everyone, needed to be labeled from inaccurate to accurate on a five point likert scale.

The language rating experiment was programmed as a website (https://phonaesthetics.de/), and made accessible online internationally. The only requirements to take part in the experiment were a computer/laptop and an email address, which served as means to receive an access code. After filling in the access code, the participants were asked to share their socio-demographic information, such as their year of birth, place of birth, biological gender and information concerning which countries they have stayed at for longer than 3 months (mobility). Additionally, participants had to give information with respect to their language background, providing up to ten languages they spoke with corresponding estimated proficiency levels from A1 to C2 as well as in numbers on a scale starting with 0 (knowing only a few words) up to 100 (fluent speech). They also had to provide information about their musicality and singing proficiency using numbers starting at 1 (low proficiency) to 10 (very high proficiency).

After finishing this questionnaire, the actual experiment started with a sound test, ensuring the functionality of the headphones (participants were advised to use headphones). As soon as a participant confirmed the correct functioning of the technical equipment, the languages were presented in random order. After listening to each language as often as desired, participants were asked to rate it concerning Eros (How sexy does this language sound to you? How erotic do you think it is?), Beauty/Sweetness (How beautiful/sweet does this language sound to you?), Status (What is your impression of the social status of this language? How high or low is its social status in your opinion? How respected or honored is it for you?), and Orderliness/Structure (How well-structured/orderly does this language sound to you?), using a scale from 0 to 100. In addition to that, participants were asked to state if the languages had sounded familiar to them and how much they had liked or disliked the voices (Do you like the voice?), again using a scale from 0 to 100. The last two questions concerned the identity of each language: which language the participants thought they had listened to, and which language might be a close relative to the current stimulus. All of these ratings and answers had to be given for each of the 23 languages displayed to each participant. After the last language was rated and the guessing task completed, the embedded link opened the website for the Big Five Personality test. As soon as the test was done, the participants were shown their results and asked to fill in the numbers in the spaces provided on the main experiment website.

The languages which received the highest mean rating in terms of Eros were Greek (mean = 53.87, SD = 19.93), Basque (mean = 5.71, SD = 20.28), Swedish (mean = 51.45, SD = 20.06), and Catalan (mean = 51.32, SD = 20.57). The lowest rated languages for Eros were Welsh (mean = 35.40, SD = 21.22), Danish (mean = 39.17, SD = 22.01), and Norwegian (mean = 41.65, SD = 22.05). For further details of the Eros ratings see Figure 5.

Similar to the Eros ratings, the three highest rated languages for Beauty were Greek (mean = 62.46, SD = 19.85), Basque (mean = 59.26, SD = 21.37), and Swedish (mean = 59.02, SD = 20.19). The lowest ratings were given to Danish (mean = 50.04, SD = 24.18), Welsh (mean = 50.56, SD = 24.27), and Turkish (mean = 50.63, SD = 21.68). Figure 6 illustrates the Beauty ratings.

Concerning Status, the Germanic languages—Swedish (mean = 59.02, SD = 18.59), Norwegian (mean = 57.96, SD = 18.09), and Danish (mean = 56.45, SD = 18.58) were rated the highest. The lowest Status ratings were for Turkish (mean = 47.57, SD = 18.89), Albanian (mean = 47.72, SD = 18.07), and Maltese (mean = 48.32, SD = 18.13). Figure 7 depicts further details of the distribution of Status ratings.

In terms of Orderliness, the languages which received the highest ratings were Slovene (mean = 63.35, SD = 17.48), Hungarian (mean = 62.00, SD = 19.08), and Norwegian (mean = 61.92, SD = 18.54). The languages which were rated the lowest were Turkish (mean = 54.25, SD = 19.61), Albanian (mean = 54.65, SD = 17.90), and Maltese (mean = 55.67, SD = 17.37). Figure 8 shows the ratings of the Orderliness factor.

In addition to Eros, Beauty, Status and Order ratings, we asked participants to rate the speaker voices. As we used two different stimulus sets of 23 recordings each, we had 46 different speakers, two for every language. Thus, voice was operationalized in two ways: by direct subjective opinion ratings (“voice rating”) and by an objective experimental manipulation unconscious to the participants (two different “stimulus voice sets”). The languages whose speakers received the highest mean voice ratings (subjective ratings) calculated of both stimulus sets were Greek (mean = 71.55, SD = 21.45), Swedish (mean = 70.75, SD = 20.79), and Latvian (mean = 69.97, SD = 19.90). The lowest rated voices were for Welsh (mean = 52.07, SD = 27.02), Turkish (mean = 63.24, SD = 24.43), and Catalan (mean = 63.72, SD = 22.79).

Voice (both “voice ratings” and “stimulus voice set”) was included in all hierarchical regression models with Eros, Beauty, Status and Order ratings as dependent variables and served as a potential covariate. Subjective voice ratings contributed about 30% of the variance in phonaesthetic judgments at a significant level of p < 0.001*** in all models. At the same time, the objective experimental voice manipulation “stimulus set” (each language had two voices and each participant listened to only one of the voices: either Stimulus set 1 or Stimulus set 2, randomly assigned) was not statistically significant in any of the regression models. Figure 9 shows the results of the speaker voice ratings of all languages. A word of caution must be added to the subjective voice ratings. Since those were collected always immediately after the language aesthetic ratings in the same experimental manner (same scoring procedure), they also resulted in much higher similarity and thus also higher correlation/influence on the aesthetic ratings than the more objective voice set manipulations do and therefore might represent a more biased response.

The recognition rating was conceptualized as a 4-point scale (0-1-2-3): participants received three points for correct identification of a language upon asking, What was the language you just heard? Two points were granted for naming a close language relative (e.g., Belorussian for Ukrainian—both languages belong to the East Slavic branch of the Slavic language family). One point was granted for naming the correct language family or another member thereof (e.g., Polish for Ukrainian—both languages belong to the Slavic language family but different branches). Lastly, zero points were given for naming a language that had nothing to do with the language of the recording (e.g., Spanish for Ukrainian) or responding with “no idea” or “I don't know.”

Of all language samples, participants recognized the correct language in 18.92% of attempts (SD = 0.11%). The top three recognized and correctly identified languages were: Portuguese (44%), Greek (43%), and Hungarian (30%) (Figure 10). The least recognized languages, on the other hand, were Albanian (6%), Latvian (6%), and Slovene (5%).

Speech rate was operationalized as the number of syllables per second based on the audio recordings of The Northwind and the Sun in its corresponding translations which were used as stimuli. Two voices per language created two sets of measurements for speech rate. The sets correlated significantly with each other (r = 0.81, p < 0.001***) and with the previously reported data from Kogan and Reiterer (2021)—r = 0.69, p = 0.03*. We used the mean value between two voices per language to signify each language's speech rate (Figure 11 for speech rates). Overall, participants gave higher ratings for faster languages (r = 0.36, p = 0.08.). Yet, speech rate was not significant in any of the hierarchical regression models with Eros, Beauty, Status and Order ratings as dependent variables.

An average sonority index was calculated for every language based on the two recordings available. We used Nemestothy (2022)'s universal sonority scale that adapts the sonority values from Fought et al. (2004) and extends them to the phonemes of the languages of the present experiment. Our previous findings on the relationship between phonaesthetic judgments and sonority showed that highly sonorous languages receive higher ratings for Eros and Beauty (Reiterer et al., 2020). We did not find the same pattern in the present study. Although overall people found more sonorous languages more erotic (r = 0.04, p = 0.84) and beautiful (r = 0.14, p = 0.52)—neither of these correlations has reached significance. The regression analysis with Eros and Beauty ratings as dependent variables confirmed this pattern; the contribution for sonority for Eros: B = 0.2, p = 0.56 and for Beauty: B = 0.37, p = 0.18.

In order to determine which personality factors contributed significantly to phonaesthetic ratings, we first explored the contribution of non-personality variables. We fitted four hierarchical regression models with Eros, Beauty, Status and Order ratings as dependent variables. Each model had two random effects (participants and the languages of the experiment, different intercepts only) and the following fixed effects: participant gender, self-reported musicality (How musical do you consider yourself?— on a 0–10 scale with 10 being very musical), the number of musical instruments played, self-reported singing skills (How well do you think you sing?—on a 0–10 scale with 10 being singing very well), language recognition rate, the number of foreign languages spoken, rating for voice (beautiful or not), the voice stimulus set, mobility (the number of countries visited or lived at for more than 3 months), and the distance between participants' native language (L1) and the languages of the experiment.

The L1 distance was operationally based on the Serva-Petroni distance (Serva and Petroni, 2008; Petroni and Serva, 2010; Kogan and Reiterer, 2021) and varies from 0 to 1 (zero represents theoretically maximal closeness/sameness, 1 is maximal distance). The Serva-Petroni distance is a modification of the Levenstein distance which is the minimum number of insertions, deletions, or substitutions of a single character needed to transform one word into the other. This measure is more appropriate for the present study in comparison to syntactic typology which takes into consideration the structural properties of language and primarily rely on grammatical rules to compare languages. Since our participants are only exposed to the auditory aspect of the languages, they could only judge the distance between languages based on the sound shape. Some languages sound similar even if they are typologically distant—e.g., Russian and Portuguese (Zaepernicková et al., 2017), and some typologically close languages sound rather distinct (e.g., Spanish and French). The ideal distance to estimate how close or far two languages are in terms of sound would be the phonological distance. Attempts have been made to calculate such a distance (Eden, 2018) but a systematic approach is still under development, and the Serva-Petroni distance continues to constitute the closest we can get to the phonological distance.

When the four random-intercept hierarchical regression models were fitted using maximum likelihood, voice (subjective voice ratings) and the recognition rate contributed significantly to Eros, Beauty, Status and Order ratings (p < 0.001*** across all models for both of these variables). The interaction term between the recognition rate and language for the Eros model demonstrated that the significant contribution of the recognition rate was only significant for highly recognized Portuguese (B = 3.86, p = 0.05*), other languages were not affected by the recognition rate at the significant level. The interaction term between the recognition rate and language for the Beauty model demonstrated that the significant contribution of the recognition rate was significant only for Norwegian (B = 4.82, p = 0.03*) and Portuguese (B = 4.11, p = 0.04*). The interaction term between the recognition rate and language for the Status model demonstrated that the significant contribution of the recognition rate was significant only for Icelandic (B = 4.06, p = 0.02*), Norwegian (B = 4.61, p = 0.02*), and Slovene (B = 6.08, p = 0.009**). The interaction term between the recognition rate and language for the Order model demonstrated that the significant contribution of the recognition rate was significant for Czech (B = 3.85, p = 0.05*), Icelandic (B = 4.82, p = 0.007**), Norwegian (B = 5.07, p = 0.008**), Swedish (B = 3.79, p = 0.04*), and Ukrainian (B = 5.24 p = 0.01*). Moreover, not every language benefited from being recognized: e.g.,: Breton, Danish, Icelandic, and Polish demonstrated negative relationships between the recognition rate and Eros ratings (more recognized, less erotic or less recognized, more erotic). We are not discussing these findings further as none of the negative relationships reached the significance level (p < 0.01).

In addition, the L1 distance contributed significantly to the ratings of Beauty with more distance between participants' L1 and the languages of the experiment corresponding to lower Beauty ratings (B = −10.41, p = 0.007**). Gender of the participants also resulted in significant results: men rated languages significantly lower for Status (B = −4.61, p = 0.04*) and Order (B = −4.94, p = 0.03*) than women. Lower self-reported singing ability (B = −1.04, p = 0.04*) and fewer foreign languages spoken (B = −1.06, p = 0.048*) resulted in higher ratings for Status.

Personality features—extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness were fitted to hierarchical regression models in the second step. The dependent variables stayed the same—Eros, Beauty, Status and Order ratings. The random effects included participants and the languages of the experiment (different intercepts only). The fixed effects included the significant fixed effects from Step 1 and the personality features. The addition of the personality features improved all Eros and Beauty models significantly (a chi-square difference test: p = 0.02* for Eros, p = 0.055* for Beauty) but not for Status and Order. In the case of Eros, the explained variance in the dependent variable increased by about 1% after the addition of personality features (R-square = 0.41 for the non-personality model and R-square = 0.42 for the personality model). The same was true for Beauty: (R-square = 0.50 for the non-personality model and R-square = 0.49 for the personality model).

In terms of individual personality factors, neuroticism contributed negatively and significantly to Eros ratings (B = −0.098, p = 0.035*) and extraversion contributed negatively and significantly to Beauty ratings (B = −0.09, p = 0.049*). At the trend level, agreeableness affected Beauty ratings positively (B = 0.11, p = 0.09) and conscientiousness affected Status positively as well (B = 0.12, p = 0.07).

The interaction term between the L1 distance and personality traits did not reach significance for Beauty ratings meaning that none of the personality traits affected Beauty ratings in a significantly different manner (e.g., openness resulted in preference for more distant language and agreeableness for less distant languages).

As mentioned earlier the recognition rate contributed significantly to all four phonaesthetic ratings changing the scores by as much as 1–2 points (positively for Eros, Beauty and Order—the more languages were recognized the more attractive they seemed alongside these dimensions, and negatively for Status—unrecognized languages were rated lower for Status).

In the next step of our analysis we only used the data points for languages that received the recognition rate equal to zero, meaning a completely different language was named in response to the question What was the language you just heard? The same variables were fitted in two-step hierarchical regression models as in Sections 3.2 and 3.3. Voice [“subjective voice ratings” (and not the objective “voice set”)] continued playing a significant role in all eight models (with and without personality factors, for Eros, Beauty, Status and Order). Neuroticism still affected Eros ratings negatively and significantly (B = −0.01, p = 0.04*). Extraversion affected Beauty ratings at the trend level (B = −0.08, p = 0.1) with agreeableness no longer in the picture, even at the trend level. We still observed the trend level effects of conscientiousness on Status ratings (B = 0.12, p = 0.07). The number of languages spoken continued affecting Status ratings negatively (B = −1.17, p = 0.04*), together with the trend level effects of singing ability (B = −0.6, p = 0.9). The effects of gender were no longer present in this dataset with unrecognized languages.

Interestingly, only one model improved significantly from addition of personality features: the Eros model (a chi-square difference test: p = 0.01*). Personality features explained about 1% of variance in Eros ratings with 0.44% driven by neuroticism alone.

Regarding the Latin Lover effect, Romance languages do not lead the list anymore, and now we have favored languages like Breton, Basque, Greek, and Swedish. Some of them (Breton, Basque, and Greek) were largely confused with Romance languages (in about 50% of cases). Once they are unrecognized, the Eros and Beauty of Portuguese and Catalan plunge down. This loss is especially pronounced for Catalan that goes from the average of 52 points to 38 for Eros and from 58 to 42 for Beauty. Unrecognized Catalan is also not praised for Order (from 58 to 50) and Status (from 53 to 44) anymore. Unrecognized Portuguese loses 4 points for Eros and 7 points for Beauty; its ratings for Order and Status are less affected. Interestingly, minority languages such as Breton and Basque win across all dimensions when unrecognized. Whereas, Danish and Norwegian seem to be less attractive in terms of Eros, Beauty, Order, and Status, when unrecognized.

The leaders are now: for Eros: Greek, Swedish and Breton; for Beauty: Greek, Breton and Basque; for Order: Hungarian, Latvian, and Icelandic; for Status: Swedish, Czech, and Polish.

The present study aimed to explore the contribution of personality traits to phonaesthetic judgments of 23 lesser-known European languages. Our participants rated the languages of the experiment in terms of eroticism, beauty, status, and orderliness. While analyzing the resulting data, we first explored the contribution of non-personality factors to phonaesthetic judgments. We found that participants' judgments of some languages were influenced by the recognition rate—how well they recognized these languages. Where these relationships were significant, the recognition meant a higher rating. In our previous studies (Reiterer et al., 2020; Kogan and Reiterer, 2021), familiarity with languages also increased their attractiveness. Decades of research into the connection between familiarity and liking have shown a robust positive correlation between the two (e.g., Birch and Marlin, 1982), the gist of which is summarized by an oft-quoted German proverb: “What a farmer does not know, he does not eat.” Evolutionary psychologists explain this preference as such: familiar objects are perceived as favorable because they have been proven harmless after the initial exposure (Bornstein, 989). More recent socio-cognitive explanations point to a facilitation effect, which occurs when a stimulus is processed on a second or third occasion (Winkielman and Cacioppo, 2001; Reber et al., 2004). Thus, familiar languages, requiring less effort to process, might be perceived as sounding more pleasant because they are easily recognized and processed by a listener. In this sense, the auditory pleasure derived from listening to the sounds of language resembles the pleasure derived from music: anticipation or expectancy (previous knowledge about a given language or music) is an essential mechanism of a pleasurable experience (Steinbeis et al., 2006; Vuust and Kringelbach, 2010).

Even though the general trend pointed in the direction of “more recognition—more liking,” in this study, the effects of recognition were different for different languages. Only some languages were rated significantly higher when recognized: e.g., well-recognized Portuguese was rated higher for Eros and Beauty; a higher recognition of the Scandinavian languages (Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish) resulted in higher ratings for Order. On the other hand, for some languages, recognition was not connected (either positively or negatively) to phonaesthetic judgments. Thus, the imposed norm hypothesis (Giles et al., 1974; Chand, 2009; Schüppert et al., 2015) can be only partially confirmed: it seems that the activation of socio-cultural aura influences the attitude only toward some languages, perhaps, the ones that have powerful stereotypes attached to them. In these experiments such languages were Portuguese (Eros and Beauty), Scandinavian and Slavic languages of the experiment. On average, Scandinavian (Germanic) and Slavic languages received higher ratings for Status and Order as a result of recognition. The analysis of the common stereotypes attached to these languages and cultures was outside of the scope of this study.

Another non-personality variable—the distance between participants' L1 and the languages of the experiment—contributed to phonaesthetic judgments of Beauty at a significant level. Overall, participants found languages more similar to their L1 sounding more beautiful. This effect was no longer present when only unfamiliar (unrecognized) languages were used for the analysis, leading us to the conclusion that the preference for languages closer to one's L1 was not so much based on the sound differences as on a sociocultural distance, i.e., participants preferred languages of neighboring countries (that were often also typologically closer). When participants could not make this socio-cultural connection (did not recognize the language), the relationships between L1 and the language heard disappeared. Speaking of language distance and personality, we predicted that higher levels of openness would lead to higher ratings for languages more distant from the native language. This hypothesis was based on the previous research showing that openness is often associated with the willingness to explore the unknown, openness to new experiences, curiosity (Nettle, 2007) and open-mindedness/risk-taking (Afhami and Mohammadi-Zarghan, 2018). We did not find relationships between L1 distance and openness. Participants higher in openness behaved the same way as other personality types preferring the language more similar to their L1. It seems that native language overrides personality when phonaesthetic judgments are involved. Phonaesthetics preferences for new linguistic stimuli might work differently in comparison to visual arts (Afhami and Mohammadi-Zarghan, 2018) or music (Greenberg et al., 2022) where more open individuals do not have a powerful prior system in place such as a native language when forming their preferences. We also expected that participants with a higher level of openness would speak more second languages in comparison to other personality types and be able to guess more languages correctly. In fact, our data confirmed the opposite: higher levels of openness led to lower recognition scores. These unexpected findings could be due to the fact that our participant group was a group of people with high openness-scores overall (mean score equated to 76% out of 100%). Afhami and Mohammadi-Zarghan (2018) observe that individuals with higher levels of openness show greater interest in aesthetic judgment tasks and experiments. That indeed was the case in our study.

We observed the significant effects of gender on Status and Order ratings with men rating languages for these dimensions lower than women. Our first explanation was that female listeners could sympathize with the female voices of the recordings more (e.g., Wilding and Cook, 2000). Another possible explanation was that women are more generous judges overall. For example, in their experiment on attitudes toward the dialects of the UK, Coupland and Bishop (2007) observed a similar effect with women rating the non-native dialects higher than men (and men preferring their own speech to other dialects). Yet, a recent study conducted by Sharma et al. (2022) with a similar design reported the absence of gender-based differences in modern UK. Interestingly, the effects of gender disappeared in our study when only unrecognized languages were involved: when participants were no longer able to identify the languages the ratings coming from men and women were not significantly different. It seems that women were more susceptible to the familiarity effects we described above—the finding concurrent with evolutionary research on sex differences in attraction to familair stimuli (Little et al., 2014).

The main goal of this study was to explore if personality contributes to phonaesthetics judgments. We found that higher levels of neuroticism resulted in lower ratings for Eros, meaning that these individuals found the languages of the experiment sounding less erotic in comparison to other personality types. This relationship remained significant even when only unrecognized languages were used for the analysis, thus removing any possible socio-cultural connotations. This confirmed our speculation that neurotics would not make happy raters due to their tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety, worry, shame, guilt, disgust, or grief, far more strongly than other personality types (Nettle, 2007). Yet, our hypothesis was only partially confirmed since neurotics did not differ from other participants when rating languages for Beauty, Status, and Order. It could be that eroticism is one dimension neurotics are not comfortable with not necessarily in linguistic terms but across modalities. A longitudinal study by Fisher and McNulty (2008) reported that a higher level of neuroticism was associated with less sexual satisfaction within and outside the marriage. Earlier studies on neuroticism also observed that individuals with higher levels of neuroticism tend to les enjoy intimacy, romantic and erotic life events (Costa et al., 1992; Goldenberg et al., 1999; Heaven et al., 2000). It seems that neurotics might have a limited understanding of eroticism as a phonaesthetic dimension and do not appreciate linguistic stimuli in such terms. In addition, neurotics rated the languages of the experiment in the more inconsistent way than other personality types, showing the highest variance in rating behavior. Previous research has shown that neurotics are not particularly appreciative of organized systems and the concept of structure and have difficulty following rules making them rather sporadic psycholinguistic experiment participants (Bowling et al., 2011).

Based on previous personality research (Nettle, 2007; Bowling et al., 2011; Carleton, 2016; Proverbio et al., 2018), we expected extraverts to appreciate languages more in terms of eroticism and beauty as opposed to other aesthetic dimensions (orderliness/well-structuredness and social status). Yet, it was the introverts who rated the languages of the experiment significantly higher for beauty (no relationships between extraversion/introversion and eroticism). This effect was also observed with the data consisting of unrecognized languages only but at a trend level. Proverbio et al. (2018) noticed that introverts have a higher arousal level compared to extraverts in response to auditory stimuli. Rizzo-Sierra et al. (2012) call it “the highly sensitive trait,” the ability to process sensory information at a deeper level—they associate this ability with introversion. Thus, it could be that introverts in our study were more responsive to the auditory dimension of linguistic stimuli overall, and thus, appreciated it more, which resulted in higher phonaesthetic ratings for beauty.

We also observed a tendency for individuals with higher levels of agreeableness rating languages higher for Beauty. This trend disappeared when only unrecognized languages were used. One of our hypotheses stated that higher levels of agreeableness would yield in ratings consistent with common stereotypes, such as the erotic Romance languages (Catalan, Portuguese, and Romanian in our experiment), since more agreeable individuals often follow trends and like to be in sync with the prevailing opinion (Nettle, 2007). Agreeable individuals in our study favored Breton, Latvian, and Swedish thus primarily supporting the non-Romance language families. We also hypothesized that higher conscientiousness, characterized by order and discipline, would be associated with higher ratings for Order (how consistent or well-structured a particular language sounds) and Status. This hypothesis was only confirmed for Status with individuals higher in conscientiousness rating languages higher for perceived prestige than other personality types. We concluded that personality only partially contributes to phonaesthetics rating with other powerful variables intertwining such as participants' native languages and familiarity with languages.

Throughout the experiment, we noticed that the same languages at times received opposite treatment by different personality types. For example, Breton was cherished by introverts for Eros and dismissed by neurotics alongside the same dimension. For languages on the verge of extinction, the phonaesthetic allure plays an important role giving them a strong support and a chance to survive. Introducing these languages in populations with a specific psychological profile (e.g., higher or lower on extraversion) might increase the rate of its learnability. As much as this idea might seem extreme, matching languages to learners' individual differences for optimal learning outcomes is a plausible direction in some educational environments (MacWhinney, 1995).

The data partially confirmed a phenomenon we described in our previous studies (Reiterer et al., 2020; Kogan and Reiterer, 2021), the Latin Lover effect. The Latin Lover effect states that, generally speaking, people find Romance languages (e.g., Spanish, French, Italian) sounding more erotic and beautiful than non-Romance languages. Our previous research showed that these languages sound attractive not only because of their socio-cultural aura (the imposed value hypothesis) but also because of the high sonority index and a regular CV (consonant-vowel) syllabic structure (the inherent value hypothesis). Since most of the languages of the present study were barely or not recognized, we hoped to observe a more prominent or pure effect of phonological features on phonaesthetic judgments and thus to be able to confirm that it is not only the associations that we have with languages that matter.

The Romance languages of the present study received conditional preferential treatment (on the condition of recognition) with higher ratings for Eros (Catalan, Portuguese, and Romanian) and Beauty (Catalan and Portuguese). Interestingly, Greek, Basque, and Swedish also led the list for these aesthetic parameters, unconditionally. Just like most Romance languages, language isolates like Basque or quasi isolates like Greek are highly sonorous languages, a linguistic feature typical for languages spoken in a warm climate (Maddieson, 2018). In our previous studies we showed that sonority is often associated with Eros and Beauty (Reiterer et al., 2020; Kogan and Reiterer, 2021; Nemestothy, 2022). That being said, in the current study we did not see a significant relationship between sonority and Beauty/Eros ratings. It could be that Eros and Beauty ratings were not that high in general in this experiment and we did not have the “big shots” such as French, Spanish, and Italian, the sonority champions. By investigating less-researched languages we might have leveled out the variance in the ratings. Overall, the concept of sonority is a debatable question with conflicting evidence of its acoustic correlates. Previous research described sonority as loudness (Ladefoged, 2010), intensity (Parker, 2011), and periodic energy (Albert and Nicenboim, 2020; Albert et al., 2022). With the lack of unanimity on the nature of the phenomenon it is also challenging to measure it accurately. Primarily based on English, the existing sonority scales do not allow for consistent measures cross-linguistically. We used the universal sonority scale developed by Nemestothy (2022) that has to be further tested and confirmed empirically.

Interestingly, highly rated Greek and Basque were frequently confused with Romance languages. When participants were asked what language they thought they had heard Basque was confused with mostly Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese or Romanian (57% of listeners thought it was a Romance language) and Greek with Portuguese, Spanish and Latin (30% of listeners). Considering the high ratings that Basque and Greek received for Eros and Beauty (top two positions), these findings could be discussed to hint at a possible subform of a Latin Lover effect or show a “masked Latin Lover effect.” Somehow Romance languages—genuine or not—still enjoy a preferential treatment by listeners. Breton, the third most erotic language of the experiment when unrecognized and the sixth most erotic language of the experiment when recognized (after Catalan, Basque, and Portuguese) was labeled by half of the participants as a Romance language with 9% identifying it as French. In essence, there is little to no Latin Lover effect observable in this study, yet these data are in favor of the imposed value hypothesis that states that listeners' attitudes are guided by their knowledge about the language, its speakers and the culture behind it. It looks like once participants labeled Greek, Basque, and Breton as Romance languages (to a high degree), they liked them more or this influenced their likability ratings. We called this the “Romanization effect” (Nemestothy, 2022).

It must be also noted that due to poor acoustic quality of the recording we had to exclude Corsican, one of the four Romance languages of experiment from the statistical analysis and further discussion. Thus, we ended up with only three representatives for this category (Portuguese, Catalan, Romanian) whereas all other languages families (Germanic and Slavic) had four languages per family. This is a clear limitation of the current study as we do not know how Corsican would have been perceived as a representative of a Romance language. This should be addressed and improved in future research and has to be kept in mind when discussing the Romance languages in this experiment.

For status, Germanic languages (Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, and Icelandic) were on the top of the list, conditioned moderately by recognition. This finding goes along with our previous research that demonstrated that Germanic languages are usually perceived as languages of higher status, at the same time sounding the least erotic or beautiful (Reiterer et al., 2020). Just as in Reiterer et al. (2020), orderliness yielded an inconsistent pattern of ratings with several language families occupying the top three positions, Germanic and Slavic usually amongst. What is interesting is that, once again, Romance languages were repeatedly not perceived as well-structured or ordered: Portuguese occupied the 15th place and Catalan the 16th with Romanian taking the 20th place out of the 23 languages of the experiment. 0% of Romance languages were in the top tertile of the orderliness scale-scorings (but again, we unfortunately do not know for Corsican).

We were not able to replicate the relationships between speech rate and phonaesthetic ratings that we observed in our previous research (Kogan and Reiterer, 2021). Just like with music (Juslin and Laukka, 2003; Ma and Thompson, 2015), participants in our previous studies found faster languages more arousing and excitable, rating them higher for Eros. Faster languages were also rated higher for Beauty. Although the direction of the relationship was the same in this study (faster languages, higher ratings for Eros and Beauty), this relationship did not reach the significance level. One explanation for these results could be that the measurements of speech rate were not accurate. This explanation is unlikely though: our speech rate measurements were based on two voices per language, and they correlated significantly with the measurements from Coupé et al. (2019) and our previous studies that used some of the languages of the current study. Another explanation for such results is the diverse linguistic sample of this study which poses many methodological struggles in conceptualizing certain segmental and suprasegmental phenomena. For example, languages allow different syllabic nuclei making it hard to define a concept of a syllable and thus counting the number of syllables per second to obtain the speech rate.

When only the cases with unrecognized languages were used in the dataset, Romance languages lost their allure, Germanic languages lost their status. Catalan and Portuguese were particularly affected, bringing us back to the imposed norm hypothesis: the phonaesthetics ratings of Romance languages are highly susceptible to the influence of the sociocultural aura. Once participants realize they are listening to a Romance language, they are immediately under an impression of eroticism and beauty.

One surprising discovery was how much Breton benefited from being unrecognized. This language was among the three most erotic and beautiful languages of the experiment when not recognized by participants. It seems that the socio-political tension around Breton contributed negatively to its charm. It appears like a “Latin-like-lover” which can compete on a phonaesthetic level with the charms of Romance languages.

In the present study, we tried to capture a number of individual differences that could potentially influence our results. In our previous studies, polyglotism (a number of foreign languages spoken) and musical abilities contributed to phonaesthetics judgments with polyglots and more musical individuals rating languages higher for Eros and Beauty (Reiterer et al., 2020; Kogan and Reiterer, 2021). There is also a fair guess that individuals who traveled extensively or lived abroad (mobility) were exposed to a variety of foreign languages and this could affect their judgments as well. None of these variables contributed to Eros and Beauty ratings in this study. Yet, a greater number of languages spoken and superior singing skills resulted in lower ratings for Status. More in-depth exploration of individual differences is necessary to disentangle these connections. For one, there is a growing body of research related to individual differences in linguistic perception that might be relevant to our study. Lidji et al. (2011) compared the rhythm perception of monolingual French and English participants as well as French-English bilinguals when tapping to French and English spoken sentences. The study revealed that both the listener's native language and the language-specific acoustics affected the obtained tapping patterns. Rathcke and Lin (2021) report individual differences in prosodic processing related to short-term memory (and dyslexia). Prosody is frequently referred to as music of the language (Patel et al., 2006; Chow and Brown, 2018), and thus, it is important to understand how differences in individual perception of prosody contribute to participants' auditory experience. We hope to explore it further in our future studies.

We observed some effects of personality traits on phonaesthetic judgments. In our previous studies (Reiterer et al., 2020; Kogan and Reiterer, 2021), we made a claim that the beauty of a language is at least partially (10–30%) an inherent characteristic of a linguistic system itself (sonority, speech rate). We did not confirm these findings in the current study. Instead, it seems that to some degree the sound-based beauty of language is “in the eye of the beholder” and quite individualistic within certain overarching socio-cultural construals. Participants, especially neurotics, introverts and individuals with higher conscientiousness levels, were influenced by their personality when they rated the linguistic stimuli for phonaesthetics dimensions.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study of human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

AW and SR contributed to conception and experimental design, and data collection and interpretation. AW and VK contributed to data analysis, helped in drafting, wrote, and revised the article critically. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to everybody who was and is involved in creating this experiment and enabling this research project to be conducted, namely the Phonaesthetics Research Group (SR, Max Sinnl, AW, and Lukas Nemestothy) as well as Žiga Bogataj and VK for their previous work and ongoing unstinting support as well as very much appreciated expertise. We would also like to express our deepest gratitude to the Faculty of Philology and Cultural Studies' MediaLab and its staff members (special thanks to the head of the lab, Dr. Jörg Mühlhans), who are indispensable, essential cooperation partners for this project. We are also grateful to each of our native speakers, who lend their voices to us, as well as to those who provided translations of the text we used or supported us with their advice and last but not least to the Breton Radio broadcaster Radio Kreiz Breizh (http://www.rkb.bzh/) who sent us high quality recordings (Sandrig Ar Gall, Russel Azzopardi, Jorge Balmaseda Hernandez, Alberta Borg, Aziliz Bourges, Josette Bouvet-Le Meur, Ivana Benatinská, Kateryna Bondareva, Camila, Kristine Cardella-Goetz, Lana Cerne, Iulia Chera, L. Cheveau, Jeanne Chevrel, Emma Chira, Amanda Christiansen, Christine, Christos, Yuna Cojean, Marta Csire, Laura Dalla Libera, Margherita de Gregorio, Joseph Debono, Gulsah Ekizer, Fanny, Daniela Estevao Fernandes, Froukje, Susan Gabriel-Dennis, Itsaso Garaikoetxea, Jan Geeraerts, Gloria, Regine Guillemot, Darija Halkic, Hanna, Hege, Heikki, Henrik, Ine, Nerys Jones, Joris, Masa Kajtazovic, Aleksandrs Kalejs, Katerina, Irmak Kapusiz, Fatos Kapusiz, Petra Kartela, Eirini Katrantzi, Mark Kerrain, Mona Khader, Dina Khiralla, Alan Kloareg, Tunvezh Gwlagen-Grandjean, Zlatan Kojadinovic, Kristina Kuli, Sandrine Laplanche, Rozenn Le Dreau, Olatz Leturiaga Angoitia, Madis Liias, Fiorda Llukmani, John Linder, Linnea, Aitor Lizardi Ituarte, Anna Louvrou, Megan, Melitza, Marjeta Merjasec, Rexhina Merkohitaj, Michelle, Catalina Anna Moragues Costa, Bridget Moran, Barbora Neradová, Maire Ni Charra, Tania Margarida Oliveira Amaral, Uxue Otxandorena Ieregi, Lenka Peugniez, Brisilda Plaku, Pamela M. Pereira, Lidia Zita Pimentel Pereira, Michel Priziac, Erla Ragenheið*ur, Tina Roenhovde Tiller, Karina Rurarz, Sif Rytter, Anna Sensat, Susan Shea, Alexander Sigmund, Anna Konstancja Skoczylas, Maya Stateva, Dina Talypova, Merit Tambu, Henna Talvensaari, Peter Thompson, Liisi Törmäkangas, Riina Treffner, Ellis Vaughan, Gabriela Vrzalová, Alina Yanni, Eleni Zotou, and Sintija Žubure). We had the privilege to work with wonderful people, who came from a very broad and interesting background, from various fields such as the arts, featuring pianists, composers, actresses or writers, from philosophy and languages, from the radio, university lecturers and scientists or also speakers from other domains, like international diplomacy. Many thanks to each of these contributors for being part of the project and making it an inspiringly enriching and enjoyable cooperation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/flang.2023.1043619/full#supplementary-material

Afhami, R., and Mohammadi-Zarghan, S. (2018). The Big Five, aesthetic judgment styles, and art interest. Eur. J. Psychol. 14, 764–775. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v14i4.1479

Albert, A., Cangemi, F., and Grice, M. (2022). “Using periodic energy to enrich acoustic representations of pitch in speech: a demonstration,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Speech Prosody. Wiley Online. doi: 10.21437/SpeechProsody.2018-162

Albert, A.,and Nicenboim, B. (2020). Modeling sonority in terms of pitch intelligibility with the Nucleus Attraction Principle. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/kvqy5

Bahrami-Ehsan, H., Mohammadi-Zarghan, S., and Atari, M. (2015). Aesthetic judgment style: conceptualization and scale development. Int. J. Arts 5, 33–39. doi: 10.5923/j.arts.20150502.01

Belfi, A. M., Samson, D. M., Crane, J., and Schmidt, N. L. (2021). Aesthetic judgments of live and recorded music: effects of congruence between musical artist and piece. Front. Psychol. 12, 618025. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.618025

Birch, L. L., and Marlin, D. W. (1982). I don't like it; I never tried it: Effects of exposure on two-year-old children?s food preferences. Appetite: J. Intake Res. 3, 353–360.

Bornstein, R. F. (1989). Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968-1987. Psychol. Bull. 106, 265–289.

Bowling, N. A., Burns, G. N., Stewart, S. M., and Gruys, M. L. (2011). Conscientiousness and agreeableness as moderators of the relationship between neuroticism and counterproductive work behaviors: a constructive replication. Int. J. Select. Assess. 19, 320–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2011.00561.x

Brandstätter, U. (2008). Grundfragen der Ästhetik. Bild. Musik. Sprache. Körper. Köln: Böhlau. doi: 10.36198/9783838530840

Brattico, E., Bogert, B., and Jacobsen, T. (2013). Toward a neural chronometry for the aesthetic experience of music. Front. Psychol. 4, 206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00206

Brinck, I. (2018). Empathy, engagement, entrainment: the interaction dynamics of aesthetic experience. Cogn Process 9, 201–213. doi: 10.1007/s10339-017-0805-x

Burchette, J. (2014). Sexiest Accents Poll: Where Do People Have the Voice of Seduction? CNN International. Available online at: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/sexy-accents/index.html (accessed September 18, 2018).

Carleton, R. N. (2016). Into the unknown: a review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J. Anxiety Disord. 39, 30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.007

Chand, V. (2009). [v]at is going on? Local and global ideologies about Indian English. Lang. Soc. 38, 393–419.

Chattaraman, V., Rudd, N. A., and Lennon, S. J. (2010). The malleable bicultural consumer: effects of cultural contexts on aesthetic judgments. J. Consumer Behav. 9, 18–31. doi: 10.1002/cb.290

Child, I. L. (1965). Personality correlates of esthetic judgment in college students. J. Pers. 33, 476–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1965.tb01399.x

Chow, I., and Brown, S. (2018). A musical approach to speech melody. Front. Psychol. 9, 247. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00247

Cleeremans, A., Ginsburgh, V., Klein, O., and Noury, A. (2016). What's in a name? The effect of an artist's name on aesthetic judgments. Empir. Stud. Arts 34, 126–139. doi: 10.1177/0276237415621197

Costa, P. T., Fagan, P. J., Piedmont, R. L., Ponticas, Y., and Wise, T. N. (1992). The five-factor model of personality and sexual functioning in outpatient men and women. Psychiatr. Med. 10, 199–215.

Costa, P. T., and McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO Personality Inventory. Manual Form S and Form R. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources. doi: 10.1037/t07564-000

Coupé, C., Oh, Y. M., Dediu, D., and Pellegrino, F. (2019). Different languages, similar encoding efficiency: comparable information rates across the human communicative niche. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw2594. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw2594

Coupland, N., and Bishop, H. (2007). Ideologised values for British accents 1. J. Sociolinguist. 11, 74–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00311.x

Dolcos, F., LaBar, K. S., and Cabeza, R. (2004). Interaction between the amygdala and the medial temporal lobe memory system predicts better memory for emotional events. Neuron. 42, 855–863.

Eden, S. E. (2018). Measuring Phonological distance between languages (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University College London, UK.

Fisher, T. D., and McNulty, J. K. (2008). Neuroticism and marital satisfaction: the mediating role played by the sexual relationship. J. Fam. Psychol. 22, 112–122. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.112

Fought, J. G., Munroe, R. L., Fought, C. R., and Good, E. M. (2004). Sonority and climate in a world sample of languages: Findings and prospects. Cross-Cult. Res. 38, 27–51.

Gasperetti, M. (2014). L'italiano ‘e la quarta lingua piu‘ studiata nel mondo [Italian is the fourth most studied language in the world]. Corriere della Sera. Available online at: https://www.corriere.it/scuola/14_giugno_16/dante-pizza-italiano-quarta-lingua-piu-studiata-mondo-4edfb4fe-f57a-11e3-ac9a-521682d84f63.shtml (accessed June 16, 2014).

Giles, H., Bourhis, R., and Davies, A. (1979). “Prestige speech styles: the imposed norm and inherent value hypotheses,” in Language and Society: Anthropological Issues, eds W. C. McCormack and S. A. Wurm (Berlin; New York, NY: De Gruyter Mouton), 589–596. doi: 10.1515/9783110806489.589

Giles, H., Bourhis, R., Trudgill, P., and Lewis, A. (1974). The imposed norm hypothesis: a validation. Quart. J. Speech 60, 405–410. doi: 10.1080/00335637409383249

Giles, H., and Niedzielski, N. (1998). “Myth 11: Italian is beautiful, German is ugly,” in Language Myths, eds L. Bauer and P. Trudgill (London: Penguin Group), 85–93.

Goldenberg, J. L., Pyszczynski, T., McCoy, S. K., Greenberg, J., and Solomon, S. (1999). Death, sex, love, and neuroticism: why is sex such a problem? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 1171–1187. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1173

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., and Swann, W. B. Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big Five personality domains. J. Res. Pers. 37, 504–528. doi: 10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

Greenberg, D. M., Wride, S. J., Snowden, D. A., Spathis, D., Potter, J., and Rentfrow, P. J. (2022). Universals and variations in musical preferences: a study of preferential reactions to Western music in 53 countries. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Processes Indiv. Diff. 122, 286–309. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000397

Heaven, P. C. L., Fitzpatrick, J., Craig, F. L., Kelly, P., and Sebar, G. (2000). Five personality factors and sex: preliminary findings. Pers. Individ. Diff. 28, 1133–1141. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00163-4

Joy, A., and Sherry, J. F. Jr. (2003). Speaking of art as embodied imagination: a multisensory approach to understanding aesthetic experience. J. Consumer Res. 30, 259–282. doi: 10.1086/376802

Juslin, P. N., and Laukka, P. (2003). Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: different channels, same code? Psychol. Bull. 129, 770. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.770

Kim, S., Burr, D., and Alais, D. (2019). Effect of presentation duration of artworks on aesthetic judgment and its positive serial dependence. J. Vis. 19, 96. doi: 10.1167/19.10.96

Kogan, V. V., and Reiterer, S. M. (2021). Eros, Beauty, and phon-aesthetic judgements of language sound. We like it flat and fast, but not melodious. Comparing phonetic and acoustic features of 16 European languages. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 578594. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.578594

Lidji, P., Palmer, C., Peretz, I., and Morningstar, M. (2011). Listeners feel the beat: entrainment to English and French speech rhythms. Psychonom. Bull. Rev. 18, 1035–1041. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0163-0

Little, A. C., DeBruine, L. M., and Jones, B. C. (2014). Sex differences in attraction to familiar and unfamiliar opposite-sex faces: men prefer novelty and women prefer familiarity. Arch. Sex. Behav. 43, 973–981. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0120-2

Ma, W., and Thompson, W. F. (2015). Human emotions track changes in the acoustic environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 14563–14568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515087112

MacWhinney, B. (1995). Language-specific prediction in foreign language learning. Lang. Test. 12, 292–320. doi: 10.1177/026553229501200303

Madden, K. (2014). “Aesthetic response,” in Music in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Encyclopedia, ed W. F. Thompson (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications), 22–25.

Maddieson, I. (2018). Language adapts to the environment: sonority and temperature. Front. Commun. 3, 28. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00028

Myszkowski, N., and Zenasni, F. (2016). Individual differences in aesthetic ability: the case for an aesthetic quotient. Front. Psychol. 7, 750. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00750

Nemestothy, L. (2022). Sense and sonority – the influence of sonority on language perception (Unpublished master's dissertation). University of Vienna, Vienna.

Nettle, D. (2007). Personality: What Makes You the Way You Are. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Pandelaere, M., Millet, K., and Van den Bergh, B. (2009). First is best: first exposure effects in aesthetic judgments. Adv. Consumer Res. 36, 753.

Parker, S. (2011). “Sonority,” in The Blackwell Companion to Phonology, ed M. van Oostendorpvan (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), 1160–1184.

Patel, A. D., Iversen, J. R., and Rosenberg, J. C. (2006). Comparing the rhythm and melody of speech and music: the case of British English and French. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 3034–3047. doi: 10.1121/1.2179657

Petroni, F., and Serva, M. (2010). Measures of lexical distance between languages. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Applic. 389, 2280–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2010.02.004

Proverbio, A. M., De Benedetto, F., Ferrari, M. V., and Ferrarini, G. (2018). When listening to rain sounds boosts arithmetic ability. PLoS ONE 13, e0192296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192296

Rabanus, S. (2003). Intonation and syllable structure: a cross-linguistic study of German and Italian conversations. Zeitschrift Sprachwissenschaft 22, 86–122. doi: 10.1515/zfsw.2003.22.1.86