94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Lab Chip Technol., 25 March 2025

Sec. Medical Diagnostics

Volume 4 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frlct.2025.1549365

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Road toward Nano-Based Diagnostics for Health and DiseaseView all 9 articles

This study presents a novel point-of-care electrochemical sensor for dopamine (DA) detection, featuring a flexible laser-induced graphene (LIG) modified with a unique nanocomposite comprising Nb4C3Tx MXene, polypyrrole (PPy), and iron nanoparticles (FeNPs). The LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs is characterized by scanning electron microscopy to confirm the successful surface modification. The electrochemical performance of the fabricated sensor via cyclic voltammetry showed significant electrochemical activity upon Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs nanocomposite modification of the LIG surface with an increased peak anodic current (Ipa) from 43 μA to 104 μA. The sensor demonstrated high electrocatalytic activity and a wide linear detection range of 1 nM to 1 mM DA with excellent sensitivity of 0.283 μA/nM cm−2, and an ultralow detection limit of 70 pM. The LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor exhibited good recovery in biological samples and a remarkable selectivity for DA, effectively distinguishing it from common interfering compounds such as uric acid, ascorbic acid, glucose, sodium chloride, and their mixtures. This flexible LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor platform provides a reliable and accurate approach for detecting DA, even in complex biological matrices at point-of-care applications highlighting its potential for advanced biosensing applications.

Dopamine (DA) is a critical neurotransmitter in the brain, playing an essential role in motor control, behavior, and emotional regulation (Vallone et al., 2000; Hornykiewicz, 1966). Dopaminergic neurons are primarily located in regions such as the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area, with DA also found in peripheral tissues like the sympathetic ganglia and renal glomeruli. Imbalances in DA levels have profound physiological and pathological implications (Teng et al., 2021; Sonne et al., 2024; Latif et al., 2021; Cassidy et al., 2020). Elevated DA levels are linked to cardiotoxicity, rapid heart rates, hypertension, and heart failure, whereas reduced DA levels in the central nervous system are strongly associated with neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, stress, and depression (Bucolo et al., 2019). In Parkinson’s disease, for example, the degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra leads to decreased DA in the basal ganglia, resulting in the characteristic motor dysfunction of the disease (Salvatore, 2024). Consequently, the accurate monitoring of DA levels is of significant clinical importance (Balkourani et al., 2023).

DA can be detected in various bodily fluids, including blood, urine, and sweat (Louleb et al., 2020; Liu and Liu, 2021). Conventional analytical techniques for DA quantification, such as enzyme assays, liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, and capillary electrophoresis, provide high sensitivity and accuracy. Among these, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is widely regarded as a gold standard. However, these methods are often expensive, require specialized equipment, and are not suitable for point-of-care applications. The typical physiological range of DA concentrations in blood and urine are 0–0.25 nM and 0.3–3 μM, respectively, stressing the need for sensitive and selective detection techniques (Shinde et al., 2024). Notably, urine is a favorable sample matrix for non-invasive DA monitoring due to its relatively high DA levels, primarily derived from circulating DOPA, a dopamine precursor.

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as an attractive alternative for DA detection, offering advantages such as cost-effectiveness, rapid response, high sensitivity, and suitability for point-of-care applications (Liu and Liu, 2021). Within this field, non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors are particularly promising due to their durability, ease of use, and robustness compared to enzymatic counterparts. The development of advanced electrode materials has been a critical focus for enhancing sensor performance (Liu and Liu, 2021; Berni et al., 2022). Modifying electrode surfaces with nanostructured materials can significantly improve electrocatalytic activity, leading to enhanced sensitivity and selectivity for DA detection. Key strategies include the deposition of nanomaterials as redox mediators, functional groups to facilitate charge transfer, and nanostructures with high surface areas to increase sensitivity (Arjun et al., 2023).

The integration of laser-induced graphene (LIG) with two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials, particularly MXenes, has emerged as a promising approach to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of electrochemical biosensors (Xu et al., 2020). MXenes, despite lacking the three-dimensional network structure of graphene, possess a unique combination of properties that make them highly suitable for sensing applications (Ali et al., 2024). These include excellent mechanical strength, a large surface area, and superior electrical conductivity, all of which contribute to improved stability and efficient signal transduction in sensors. Among MXenes, Nb4C3Tx MXene has garnered attention for its remarkable chemical sensing capabilities, positioning it as a promising material for electrochemical biosensing (Shinde et al., 2024). Recent studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in detecting DA. Ti3AlC2 and Nb2AlC derivatives exhibit synergistic potential when combined with LIG and other MXenes, offering a versatile platform for biosensor development. By tailoring the composition of MXenes and incorporating complementary nanomaterials or dopants, highly sensitive and selective sensors suitable for a wide range of biological and clinical applications can be realized (Sarode et al., 2024). Additionally, the combination of MXene and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) has been reported to produce synergistic composites with enhanced performance, leveraging the complementary characteristics of both materials. MXene contributes high electrical conductivity and a chemically active surface, while CNTs provide exceptional electron mobility and mechanical robustness. Together, they form a three-dimensional interconnected network that mitigates MXene restacking, while also promoting strong interfacial adhesion and uniform dispersion. This structural and chemical synergy enhances charge transfer efficiency, increases the available surface area for electrochemical processes, and significantly improves the composite’s sensing capabilities and catalytic activity (Mohajer et al., 2023).

Several studies have explored the synergistic integration of LIG and MXene materials to enhance sensor performance, particularly in terms of limit of detection (LOD), sensitivity, and selectivity. For instance, Zhang et al. demonstrated that nitrogen- and sulfur-co-doped Nb2C MXene nanosheets significantly improved the sensitivity of DA detection under acidic conditions. The material exhibited enhanced hydrophilicity and electrochemical activity, achieving a remarkably low LOD of 0.12 µM (Zhang et al., 2023). Similarly, Mahmood et al. developed LIG formed from a biomass-based film composed of kraft lignin and cellulose nanofibers film on glassy carbon electrode for the detection of DA and the reported linear detection range (LDR) of 5–40 µM with a sensitivity of 4.39 μA μM−1 cm−2 (Mahmood et al., 2021). In another study, Amara et al. investigated Ti3C2TX MXene in combination with perylene diimide for DA detection. This hybrid composite material demonstrated improved charge transport and redox properties, achieving an LDR of 100–1,000 µM and an LOD of 240 nM (Amara et al., 2021).

Building on these advancements, this study introduces a flexible electrochemical biosensor based on LIG electrodes modified with Nb4C3Tx MXene, polypyrrole (PPy), and iron nanoparticles (FeNPs) nanocomposite for point-of-care DA monitoring. The LIG was fabricated on Pyralux® film, and the nanocomposite was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Electrochemical performance was evaluated using square wave voltammetry (SWV), revealing enhanced electrocatalytic activity and synergistic interactions between graphene, Nb4C3Tx MXene, PPy, and FeNPs. The Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor exhibited a wide linear detection range (1 nM–1 mM), high sensitivity, and excellent selectivity toward DA in the presence of common interferents. Despite limited exploration, the fabricated LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor demonstrates remarkable DA sensing capabilities and shows great promise for non-invasive, point-of-care monitoring of DA levels in bodily fluids such as urine, offering a user-friendly and accurate alternative for clinical diagnostics and personal health monitoring (Leng et al., 2015; Dalirirad and Steckl, 2020).

Pyralux® LF copper-clad laminate was procured from Dupont, Inc. Dopamine hydrochloride (C8H12ClNO2), potassium ferricyanide (K3[Fe(CN)6], sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium chloride (KCl), sodium phosphate monobasic (NaH2PO4), sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4), ascorbic acid (C6H8O6), uric acid (C5H4N4O3), glucose (C6H12O6), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), niobium aluminum carbide powder (Nb4AlC3), hydrochloric acid (HCl), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (CH3)2SO), polypyrrole ((C4H5N)n), lithium perchlorate (LiClO4), iron sulfate (FeSO4), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), calcium chloride (CaCl2), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and urea (CH4N2O) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (United States). All solutions were prepared using deionized (DI) water with a resistivity ≥18.2 MΩ·cm.

The structural characteristics of fabricated electrode materials, including LIG, LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene, LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy, and LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs, were evaluated using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Hitachi SU-8000, 20 kV). The electrochemical properties of the electrodes were analyzed using a Palmsense4 electrochemical analyzer system (BASi). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV) measurements were performed using a 5 mM potassium ferricyanide (K3[Fe(CN)6]) redox reporter solution in 0.1 M KCl as the electrolyte. Voltammograms were recorded at scan rates ranging from 10 to 100 mV/s, within a potential window of −0.6 to +1.0 V.

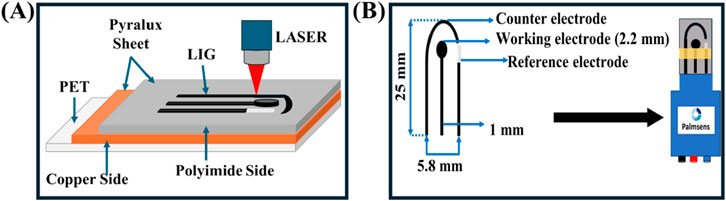

The LIG 3-electrode configurations were fabricated using a CO2 pulsed laser system (BOSS LS-1616) (Figure 1A). Graphene was synthesized on the polyimide side of the Pyralux® LF sheet, while the copper-clad side was passivated with polyethylene film. Laser power was set to 20% for both maximum and minimum thresholds, with a laser scanning speed of 200 mm/s. The fabricated working, counter, and reference electrodes had a thickzness of 1 mm. The working electrode area was defined with a diameter of 2.2 mm, and the reference electrode was coated with silver ink. The interconnecting graphene wire was passivated by applying non-conductive polyimide tape. The complete electrode assembly was mounted into a Palmsense adapter for subsequent electrochemical analysis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of (A) Laser induced graphene (LIG) electrode fabrication. (B) Fabricated sensor integration with Palmsens adapter.

The Nb4C3Tx MXene was prepared based on the protocol from (Shinde et al., 2024), wherein a modified etching method involving hydrofluoric acid (HF) was used. Specifically, 1 g of niobium aluminum carbide (Nb4AlC3) MAX phase was combined with 10 mL of HF and 13 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl) in a reaction vial. The mixture underwent gentle shaking and continuous stirring at 400 rpm for 72 h at room temperature. Following the etching process, the resulting Nb4C3Tx MXene suspension was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 minutes and washed several times with deionized water (DI) until the supernatant reached a pH between 6.5 and 7.4. Finally, the washed product was dried at 40°C for 10 min to yield stable Nb4C3Tx MXene powder.

PPy deposition was performed using an electrochemical polymerization process as reported in literature (Berni et al., 2022). A 0.1 M lithium perchlorate solution was used as the solvent to dissolve 0.15 M pyrrole monomer. A three-electrode setup was employed, with the fabricated LIG electrode serving as the working electrode. CV was performed within a potential window of −0.7 V to +0.7 V, at a scan rate of 50 mV/s for 10 cycles. After deposition, the electrode was rinsed with DI water and air-dried. To enhance conductivity and stability, the PPy-coated electrode underwent over-oxidation treatment in 0.1 M NaOH. CV was performed within a potential range of 0.0 V to +1.0 V, at a scan rate of 50 mV/s for three cycles.

FeNPs were deposited onto the LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy working electrode using chronoamperometry. This process was adopted from literature (Joshi and Slaughter, 2024). A stock solution of 50 mM iron sulfate was prepared by dissolving the salt in DI water and adding 80 µL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Before deposition, the solution was diluted to 15 mM with the addition of 30 mg of sodium sulfate. Morphologically tuned FeNPs were deposited by applying a potential of −1.1 V for 10 min at pH 3.5. The resulting electrodes were rinsed with DI water and air-dried before further characterization and testing.

Human urine primarily consists of water (approximately 95%), with the remaining 5% comprising organic and inorganic compounds, including urea (2%), creatinine (0.1%), uric acid (0.03%), and various ions such as chloride, sodium, potassium, sulfate, ammonium, and phosphate (Sarigul et al., 2019). The specific concentrations of key constituents used in this study were: calcium chloride (1.663 mM), potassium chloride (30.95 mM), sodium chloride (30.05 mM), sodium sulfate (11.96 mM), ammonium chloride (23.667 mM), and urea (249.750 mM). These components were dissolved and thoroughly mixed with DI water to prepare the synthetic urine solution.

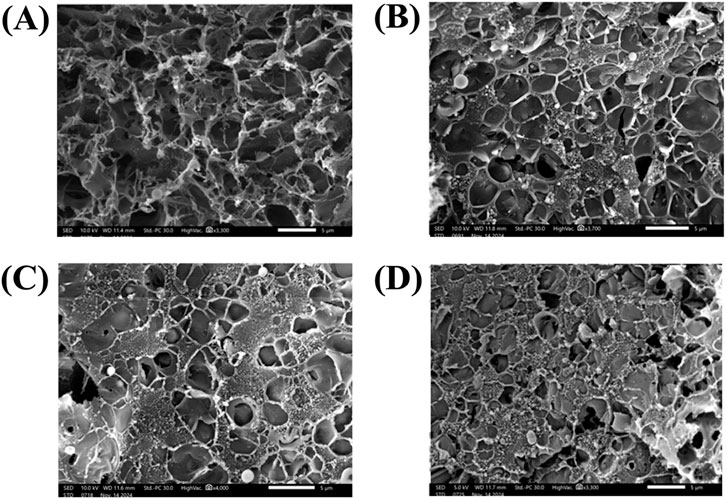

The LIG electrode, fabricated on a Pyralux® film and illustrated in Figure 2A, features a highly porous and sponge-like morphology. This structural porosity significantly expands the active surface area, enhancing its potential for electrocatalytic applications. The increased surface area improves charge transfer dynamics, facilitating efficient electron and ion mobility, which is essential for superior performance in electrochemical sensing systems (Ye et al., 2018; Thakur et al., 2022; Syugaev et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the porous nature of the material also leads to structural imperfections within the graphene framework. While these imperfections improve surface reactivity and adsorption capabilities, they can also compromise the electrode’s electrical conductivity and long-term stability (Girit et al., 2009). Therefore, additional structural enhancements are required to mitigate these limitations (Yang et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2020; Guirguis et al., 2020; Bhatt et al., 2022). To overcome these challenges and improve the electrode’s performance, a nanocomposite-based approach was implemented, where Nb4C3Tx MXene, polypyrrole (PPy), and iron nanoparticles (FeNPs) were sequentially deposited onto the LIG surface.

Figure 2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrograph of (A) bare LIG electrode. (B) LIG-Nb4C3TxMXene. (C) LIG-Nb4C3TxMXene-PPy. (D) LIG-Nb4C3TxMXene-PPy-FeNPs.

As illustrated in Figure 2B, depositing Nb4C3Tx MXene onto the LIG electrode partially occupied the porous network within the graphene structure. This integration not only enhanced the electrode’s electrical conductivity but also established a robust platform for the sequential deposition of additional nanomaterials. (Shinde et al., 2024; Arjun et al., 2023; Sarode et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2018). Additionally, the MXene layer created a dense network of conductive pathways, helping to counteract the structural imperfections of the bare LIG. After modifying the LIG with MXene, PPy was electrochemically deposited onto the LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene surface, leading to the creation of a three-dimensional porous structure, as seen in Figure 2C. The PPy layer further expanded the electrode’s surface area, forming an interconnected network that facilitated improved ion and electron transport. The heterogeneous nature of the LIG substrate played a crucial role in guiding the growth of PPy, resulting in a durable and evenly distributed layer (Berni et al., 2022; Sukumaran et al., 2025).

At the final stage, FeNPs were incorporated onto the LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy electrode, as depicted in Figure 2D. The FeNPs were evenly distributed across the electrode, forming a thin, uniform layer that boosted both conductivity and catalytic efficiency (Alzate et al., 2022). The tailored structure and composition of the FeNPs-modified electrode highlight its versatility, making it well-suited for applications requiring precise and sensitive detection (Joshi and Slaughter, 2024). The overall modification process transformed the bare LIG electrode into a highly engineered nanocomposite film through a series of steps from LIG to LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene, then to LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy, and finally to LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs. Each modification layer brought unique advantages, such as increased conductivity, a larger surface area, improved electrochemical stability, and the introduction of active sites for sensing. This stepwise integration of diverse nanomaterials presents an innovative approach for constructing high-performance electrodes (Alzate et al., 2022). The optimized morphology and composition of the FeNPs-decorated nanocomposite electrode suggest a high degree of tunability for applications requiring precise and sensitive detection capabilities (Joshi and Slaughter, 2024).

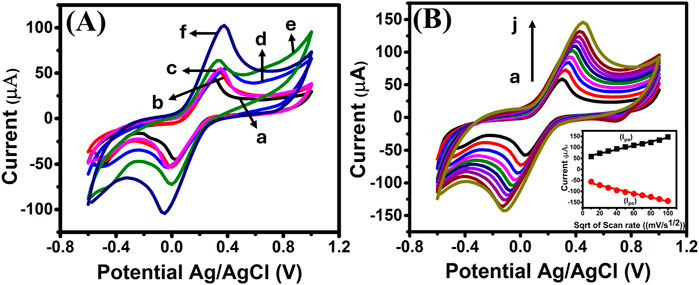

The CV results presented in Figure 3A demonstrate the electrochemical behavior of the LIG electrode across various configurations: bare LIG, LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene, LIG-PPPy, LIG-FeNPs, LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy, and the fully modified LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs electrodes. Scanned over a potential range from −0.6 V to +1.0 V at 50 mV/s in 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, all electrode configurations exhibited distinct oxidation and reduction peaks, indicative of reversible redox processes. The bare LIG electrode displayed an anodic peak current (Ipa) of approximately 40 µA (curve a), serving as the baseline for comparison. Upon modification with individual components Nb4C3Tx MXene, PPy, and FeNPs (curves b, c, and d, respectively), incremental increases in Ipa were observed. The Nb4C3Tx MXene, characterized by its exceptional electrical conductivity, high mechanical strength, and large surface area, provided a significant boost to the electrode’s electrochemical performance (Ankitha et al., 2024).

Figure 3. (A) CV overlay of (a) Bare LIG, (b) LIG-Nb4C3TxMXene, (c) LIG-PPy (d) LIG-FeNPs, (e) LIG-Nb4C3TxMXene-PPy (f) LIG-Nb4C3TxMXene-PPy-FeNPs electrodes measured in 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] containing in 0.1 M KCl. (B) Voltammograms for LIG-Nb4C3TxMXene-PPy-FeNPs electrode measured at various scan rates from 10 to 100 mV/s (a–j) in 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] containing in 0.1 M KCl. Inset: Calibration plot of Ipa and Ica vs. square root of the scan rate.

In the case of LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy (curve e), the anodic current increased to 65 μA, with slight improvement in the reaction kinetics. The PPy layer not only improved the electrode’s electrochemical performance but also contributed to the introduction of additional surface-active sites (Lakard et al., 2021). These sites, formed through partial removal of protons from the polymer backbone, increased the electrode’s sensitivity to specific redox-active species, thereby improving its applicability in biosensing (Zhuang et al., 2011; Qian et al., 2014; Santhosh Kumar et al., 2021). Moreover, the enhancement is attributed to the synergistic interaction between the MXene and the PPy layers, which collectively improved ion transport and conductivity. Conversely, these modifications also resulted in a decreased potential difference between the anodic and cathodic peaks. A smaller potential difference between the anodic and cathodic peaks indicates more efficient redox reactions, leading to improved performance.

The incorporation of FeNPs played a pivotal role in improving the electrode’s charge transfer kinetics by enhancing the conductivity of the electrode material. Notably, when further modified with FeNPs to form the LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs electrode (curve f), the anodic current exhibited a substantial increase to 103 µA. This improvement was accompanied by a reduction in the potential difference between the anodic and cathodic peaks, signifying faster charge transfer kinetics. The significant boost in current can be attributed to the synergistic effects of the LIG substrate, Nb4C3Tx MXene, PPy, and FeNPs, which collectively created a conductive nanocomposite network that significantly reduced surface resistance, enhanced electron transfer, and increased the electrode’s active surface area, thereby enhancing the electrode’s electrocatalytic properties. Additionally, the FeNPs introduced redox-active centers, which are essential for facilitating specific electrochemical reactions like DA sensing (Patel et al., 2024; Ouyang et al., 2022).

Further electrochemical characterization involved varying the scan rate from 10 to 100 mV/s, as shown in Figure 3B. The peak current values were observed to increase proportionally with the square root of the scan rate, indicating that the redox process is diffusion-controlled (Torati et al., 2024). The inset in Figure 3B confirms this relationship, with an excellent correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.9941), emphasizing the efficiency of the LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs electrode in facilitating rapid electron transfer. These findings highlight the electrode’s potential for use in electrochemical applications requiring high sensitivity and reproducibility.

The modified LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs electrode was tested for DA detection using SWV in 10 mM phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4). Successive additions of various concentrations of DA (1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, 10 μM, and 100 µM) to the electrode surface resulted in a clear and proportional increase in oxidation current (ca. 138 mV), as shown in Figure 4A. The calibration curve (inset) exhibited a wide linear range from 1 nM to 1 mM with a linear regression equation of I(μA) = 2.22 ln [DA] + 7.09 (R2 = 0.9990), where R2 is the correlation coefficient. A limit of detection (LOD) was calculated to be 70 pM based on equation 3 σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank (n = 3) and S is the slope of the calibration curve. When exposed to synthesized urine (pH 7.4), the sensor maintained excellent linearity (1 nM–1 mM) with a linear regression equation of I (μA) = 1.68 ln [DA] + 4.31 (R2 = 0.9940). In addition, the LOD was as low as 90 pM (Figure 4B). The peak shift (187 mV) observed with the synthetic urine is attributed to the complex composition of the synthetic urine. The variation in pH can alter the protonation state of DA and electrode surface properties, thereby affecting redox kinetics (Schindler and Bechtold, 2019). These values are significantly lower than the physiological DA concentration range in human urine, demonstrating the electrode’s superior sensitivity and practicality for real-world applications. The high recovery rates further validate the electrode’s reliability in complex biological matrices (Li et al., 2023).

Figure 4. SWV of (A) LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor exposed to varying concentrations of DA in PBS (pH 7.4) and (B) in synthesized urine.

The ultra-sensitive detection capability of the electrode can be attributed to the synergistic integration of its key components, each contributing uniquely to its enhanced electrocatalytic activity. Nb4C3Tx MXene, a material with excellent electronic properties, ensures efficient charge transfer and engages in π–π interactions with DA molecules, improving molecular binding and facilitating electron transfer (Ankitha et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2021). This property, combined with the high surface area of the nanocomposite, provides a platform where DA molecules can interact more effectively with the electrode surface, increasing the number of electroactive sites and enhancing sensitivity. PPy plays a critical role by forming a cation perm-selective film upon overoxidation, incorporating oxygen-containing groups such as carbonyl and carboxylic groups into its polymer backbone (Berni et al., 2022). These functional groups enhance the electronegativity and electron density of the electrode, creating a selective environment for DA oxidation while minimizing interference from other analytes. Additionally, the incorporation of FeNPs contributes to the electrode’s high surface area and introduces multiple electroactive sites, enabling sensitive and efficient electrocatalytic oxidation of DA. The FeNPs also improve the overall conductivity of the electrode, facilitating faster and more efficient electron transfer.

Overall, the combination of these materials, integrated with the LIG electrode, produces a nanocomposite with exceptional properties, including reduced surface resistance, enhanced electron mobility, and selective ion transport. This synergy results in a broader linear detection range and significantly lower LOD, critical for identifying DA at physiological levels in complex biological samples like urine. Mechanistically, DA detection is enabled by π–π stacking interactions with MXene and graphene, selective oxidation facilitated by the oxygen-containing functional groups in PPy, and rapid electron transfer enabled by the FeNPs. The sensor’s practical utility was further demonstrated through good recovery rates and R.S.D in synthetic urine as shown in Table 1. All experiments were performed in triplicates and at low DA concentrations (10 nM–10 μM), an average recovery rate of 85% with an average RSD of 2.27% was observed. However, at 1 nM and higher concentrations (100 μM and 1 mM), the sensor’s performance showed increased variability, indicating potential matrix interference and saturation. The better recovery rates for lower concentrations (10 nM–10 μM) further validate the electrode’s reliability in complex biological matrices. Table 2 compares previously reported DA electrochemical sensors constructed with various nanomaterials and surface modifications. The as-fabricated LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs electrode demonstrates superior sensitivity and a broader linear detection range for DA.

To assess selectivity, SWV was performed in the presence of common interfering species such as ascorbic acid (AA), uric acid (UA), glucose (Glu), and sodium chloride (NaCl), as well as a mixture of these interferents (Figure 5A). DA (1 µM) was tested alongside interfering analytes at 10 µM (10× the DA concentration). The results demonstrated no significant change in the oxidation current of DA in the presence of any individual interferent or their mixture. This high selectivity can be attributed to the electrode’s unique surface modifications. The PPy layer not only improved the electrode’s electrochemical stability but also contributed to its selectivity, as PPy is known for its excellent affinity for certain analytes (Chen et al., 2021). The overoxidation treatment of PPy added another dimension to its functionality by introducing additional functional groups and surface-active sites on the overoxidized PPy. Nb4C3Tx MXene also plays a critical role in enhancing the selective detection of DA through multiple synergistic mechanisms. Its surface chemistry enables strong electrostatic attraction, π–π interactions, and hydrogen bonding with DA molecules, promoting highly specific adsorption. This selective binding not only facilitates DA capture but also effectively suppresses interference from structurally similar species, such as ascorbic acid and uric acid (Lakard et al., 2021). Additionally, MXene’s exceptional electrocatalytic activity further accelerates DA oxidation, generating well-defined electrochemical signals that are readily distinguishable from those of interfering biomolecules.

Figure 5. (A) Selectivity of LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor when exposed to common interfering analytes. All experiments were performed in triplicates. (B) Stability profile of LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor.

The stability of LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor was assessed by monitoring the oxidation current of 1 µM DA over 10 days. As shown in Figure 5B, the electrode exhibited negligible signal degradation during this period, illustrating its robustness and durability and retaining 95.67% of its original activity. This stability is likely due to the strong interfacial bonding between the LIG substrate and the nanocomposite layers, which resist detachment and degradation under repeated electrochemical cycling. Thereby, the LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor offers a highly conductive, stable, and reproducible platform for DA detection. Its low LOD, extended linear range, and high selectivity make it an excellent candidate for clinical diagnostics and biosensing applications.

A flexible and ultra-sensitive electrochemical sensor for DA detection using a LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs nanocomposite has been developed. The synergistic integration of LIG with LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene, PPy, and FeNPs resulted in remarkable improvements in the electrode’s electrochemical characteristics. Key sensor performance included heightened sensitivity, excellent selectivity, and an extended linear detection range spanning from 1 nM to 1 mM. These attributes were complemented by a very low LOD, reaching 70 pM in PBS and 90 pM in synthetic urine. Such performance places this sensor among the leading tools for physiological DA monitoring, capable of detecting even trace concentrations in complex biological matrices. The exceptional functionality of the sensor is underpinned by its innovative design. Nb4C3Tx MXene contributed its high electrical conductivity and ability to engage in π–π interactions with DA molecules, facilitating efficient electron transfer. The overoxidized PPy introduced electron-rich oxygen-containing groups, enhancing the electrode’s selectivity and promoting charge transfer processes. Meanwhile, the FeNPs provided a high surface area and numerous electroactive sites, improving sensitivity and supporting rapid catalytic reactions. Together, these components formed a robust nanocomposite capable of overcoming common challenges in sensing, such as interference from other analytes, ensuring reliable detection of DA. By leveraging the unique properties of each component and their synergistic effects, the LIG-Nb4C3Tx MXene-PPy-FeNPs sensor establishes a benchmark for advanced biosensors, with potential applications extending beyond DA detection to other biologically relevant analytes in clinical and point-of-care settings.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

MS: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation. GS: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ali, A., Majhi, S. M., Siddig, L. A., Deshmukh, A. H., Wen, H., Qamhieh, N. N., et al. (2024). Recent advancements in MXene-based biosensors for health and environmental applications—a review. Biosensors 14 (10), 497. doi:10.3390/bios14100497

Alzate, M., Gamba, O., Daza, C., Santamaria, A., and Gallego, J. (2022). Iron/multiwalled carbon nanotube (Fe/MWCNT) hybrid materials characterization: thermogravimetric analysis as a powerful characterization technique. J. Therm. Analysis Calorim. 147, 12355–12363. doi:10.1007/s10973-022-11446-w

Amara, U., Mehran, M. T., Sarfaraz, B., Mahmood, K., Hayat, A., Nasir, M., et al. (2021). Perylene diimide/MXene-modified graphitic pencil electrode-based electrochemical sensor for dopamine detection. Microchim. Acta 188 (7), 230. doi:10.1007/s00604-021-04884-0

Ankitha, M., Shamsheera, F., and Rasheed, P. A. (2024). MXene-integrated single-stranded carbon yarn-based wearable sensor patch for on-site monitoring of dopamine. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 6 (1), 599–610. doi:10.1021/acsaelm.3c01668

Arjun, A. M., Shinde, M., and Slaughter, G. (2023). Application of MXene in the electrochemical detection of neurotransmitters: a Review. IEEE Sensors J. 23 (15), 16456–16466. doi:10.1109/jsen.2023.3285594

Balkourani, G., Brouzgou, A., and Tsiakaras, P. (2023). A review on recent advancements in electrochemical detection of dopamine using carbonaceous nanomaterials. Carbon 213, 118281. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2023.118281

Berni, A., Ait Lahcen, A., Salama, K. N., and Amine, A. (2022). 3D-porous laser-scribed graphene decorated with overoxidized polypyrrole as an electrochemical sensing platform for dopamine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 919, 116529. doi:10.1016/j.jelechem.2022.116529

Bhatt, M. D., Kim, H., and Kim, G. (2022). Various defects in graphene: a review. RSC Adv. 12 (33), 21520–21547. doi:10.1039/d2ra01436j

Bucolo, C., Leggio, G. M., Drago, F., and Salomone, S. (2019). Dopamine outside the brain: the eye, cardiovascular system and endocrine pancreas. Pharmacol. and Ther. 203, 107392. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.07.003

Cassidy, C. M., Carpenter, K. M., Konova, A. B., Cheung, V., Grassetti, A., Zecca, L., et al. (2020). Evidence for dopamine abnormalities in the substantia nigra in cocaine addiction revealed by neuromelanin-sensitive MRI. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 (11), 1038–1047. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20010090

Chen, S., Shi, M., Yang, J., Yu, Y., Xu, Q., Xu, J., et al. (2021). MXene/carbon nanohorns decorated with conductive molecularly imprinted poly(hydroxymethyl-3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for voltammetric detection of adrenaline. Microchim. Acta 188 (12), 420. doi:10.1007/s00604-021-05079-3

Dalirirad, S., and Steckl, A. J. (2020). Lateral flow assay using aptamer-based sensing for on-site detection of dopamine in urine. Anal. Biochem. 596, 113637. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2020.113637

Eom, G., Oh, C., Moon, J., Kim, H., Kim, M. K., Kim, K., et al. (2019). Highly sensitive and selective detection of dopamine using overoxidized polypyrrole/sodium dodecyl sulfate-modified carbon nanotube electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 848, 113295. doi:10.1016/j.jelechem.2019.113295

Girit, C. a.l.O., Meyer, J. C., Erni, R., Rossell, M. D., Kisielowski, C., Yang, L., et al. (2009). Graphene at the edge: stability and dynamics. science 323 (5922), 1705–1708. doi:10.1126/science.1166999

Guirguis, A., Maina, J. W., Zhang, X., Henderson, L. C., Kong, L., Shon, H., et al. (2020). Applications of nano-porous graphene materials–critical review on performance and challenges. Mater. Horizons 7 (5), 1218–1245. doi:10.1039/c9mh01570a

Hornykiewicz, O. (1966). Dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) and brain function. Pharmacol. Rev. 18 (2), 925–964. doi:10.1016/s0031-6997(25)07154-6

Huang, H., Shi, H., Das, P., Qin, J., Li, Y., Wang, X., et al. (2020). The chemistry and promising applications of graphene and porous graphene materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30 (41), 1909035. doi:10.1002/adfm.201909035

Joshi, A., and Slaughter, G. (2024). Multiwalled carbon nanotubes supported Fe nanostructured interfaces for electrochemical detection of uric acid. Microchem. J. 204, 110934. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2024.110934

Kim, Y.-R., Bong, S., Kang, Y.-J., Yang, Y., Mahajan, R. K., Kim, J. S., et al. (2010). Electrochemical detection of dopamine in the presence of ascorbic acid using graphene modified electrodes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 25 (10), 2366–2369. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2010.02.031

Koyun, O., Gursu, H., Gorduk, S., and Sahin, Y. (2017). Highly sensitive electrochemical determination of dopamine with an overoxidized polypyrrole nanofiber pencil graphite electrode. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 12 (7), 6428–6444. doi:10.20964/2017.07.41

Lakard, S., Pavel, I.-A., and Lakard, B. (2021). Electrochemical biosensing of dopamine neurotransmitter: a review. Biosensors 11 (6), 179. doi:10.3390/bios11060179

Latif, S., Jahangeer, M., Maknoon Razia, D., Ashiq, M., Ghaffar, A., Akram, M., et al. (2021). Dopamine in Parkinson's disease. Clin. Chim. acta 522, 114–126. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2021.08.009

Leng, Y., Xie, K., Ye, L., Li, G., Lu, Z., and He, J. (2015). Gold-nanoparticle-based colorimetric array for detection of dopamine in urine and serum. Talanta 139, 89–95. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2015.02.038

Li, Y., Chang, C.-C., Wang, C., Wu, W.-T., Wang, C.-M., and Tu, H.-L. (2023). Microfluidic biosensor decorated with an indium phosphate nanointerface for attomolar dopamine detection. ACS sensors 8 (6), 2263–2270. doi:10.1021/acssensors.3c00228

Liu, X., and Liu, J. (2021). Biosensors and sensors for dopamine detection. VIEW 2 (1), 20200102. doi:10.1002/viw.20200102

Louleb, M., Latrous, L., Rios, A., Zougagh, M., Rodríguez-Castellón, E., Algarra, M., et al. (2020). Detection of dopamine in human fluids using N-doped carbon dots. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3 (8), 8004–8011. doi:10.1021/acsanm.0c01461

Mahmood, F., Sun, Y., and Wan, C. (2021). Biomass-derived porous graphene for electrochemical sensing of dopamine. RSC Adv. 11 (25), 15410–15415. doi:10.1039/d1ra00735a

Mohajer, F., Ziarani, G. M., Badiei, A., Iravani, S., and Varma, R. S. (2023). MXene-carbon nanotube composites: properties and applications. Nanomaterials 13 (2), 345. doi:10.3390/nano13020345

Ouyang, Y., O'Hagan, M. P., and Willner, I. (2022). Functional catalytic nanoparticles (nanozymes) for sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 218, 114768. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2022.114768

Patel, K. D., Keskin-Erdogan, Z., Sawadkar, P., Nik Sharifulden, N. S. A., Shannon, M. R., Patel, M., et al. (2024). Oxidative stress modulating nanomaterials and their biochemical roles in nanomedicine. Nanoscale horizons 9 (10), 1630–1682. doi:10.1039/d4nh00171k

Qian, T., Yu, C., Zhou, X., Ma, P., Wu, S., Xu, L., et al. (2014). Ultrasensitive dopamine sensor based on novel molecularly imprinted polypyrrole coated carbon nanotubes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 58, 237–241. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2014.02.081

Salvatore, M. F. (2024). Dopamine signaling in substantia nigra and its impact on locomotor function—not a new concept, but neglected reality. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (2), 1131. doi:10.3390/ijms25021131

Santhosh Kumar, R., Govindan, K., Ramakrishnan, S., Kim, A. R., Kim, J.-S., and Yoo, D. J. (2021). Fe3O4 nanorods decorated on polypyrrole/reduced graphene oxide for electrochemical detection of dopamine and photocatalytic degradation of acetaminophen. Appl. Surf. Sci. 556, 149765. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149765

Sarigul, N., Korkmaz, F., and Kurultak, İ. (2019). A new artificial urine protocol to better imitate human urine. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 20159. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56693-4

Sarode, A., Torati, S. R., Hossain, M. F., and Slaughter, G. (2024). A photo-driven bioanode based on MXene-decorated graphene. Electrochimica Acta 498, 144637. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2024.144637

Schindler, S., and Bechtold, T. (2019). Mechanistic insights into the electrochemical oxidation of dopamine by cyclic voltammetry. J. Electroanal. Chem. 836, 94–101. doi:10.1016/j.jelechem.2019.01.069

Shinde, M., Ramulu Torati, S., and Slaughter, G. (2024). Nb4C3Tx MXene-AgNPs decorated laser-induced graphene for selective detection of dopamine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 959, 118180. doi:10.1016/j.jelechem.2024.118180

Sonne, J., Reddy, V., and Beato, M. R. (2024). Neuroanatomy, substantia nigra. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Sukumaran, R. A., Lakavath, K., Phani Kumar, V. V. N., Karingula, S., Mahato, K., and Kotagiri, Y. G. (2025). Eco-friendly synthesis of a porous reduced graphene oxide-polypyrrole-gold nanoparticle hybrid nanocomposite for electrochemical detection of methotrexate using a strip sensor. Nanoscale 17 (8), 4472–4484. doi:10.1039/d4nr04010d

Syugaev, A., Zonov, R., Mikheev, K., Maratkanova, A., and Mikheev, G. (2023). Electrochemical impedance of laser-induced graphene: frequency response of porous structure. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 181, 111533. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2023.111533

Teng, Y., Liu, Z., Chen, X., Liu, Y., Geng, F., Le, W., et al. (2021). Conditional deficiency of m6A methyltransferase Mettl14 in substantia nigra alters dopaminergic neuron function. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25 (17), 8567–8572. doi:10.1111/jcmm.16740

Thakur, A. K., Mahbub, H., Nowrin, F. H., and Malmali, M. (2022). Highly robust laser-induced graphene (LIG) ultrafiltration membrane with a stable microporous structure. ACS Appl. Mater. and interfaces 14 (41), 46884–46895. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c09563

Torati, S. R., Hanson, B., Shinde, M., and Slaughter, G. (2024). Gold deposited laser-induced graphene electrode for detection of miRNA-141. IEEE Sensors J. 24, 2154–2161. doi:10.1109/jsen.2023.3336165

Vallone, D., Picetti, R., and Borrelli, E. (2000). Structure and function of dopamine receptors. Neurosci. and Biobehav. Rev. 24 (1), 125–132. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00063-9

Wang, L., Xu, H., Song, Y., Luo, J., Wei, W., Xu, S., et al. (2015). Highly sensitive detection of quantal dopamine secretion from pheochromocytoma cells using neural microelectrode array electrodeposited with polypyrrole graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. and Interfaces 7 (14), 7619–7626. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b00035

Wang, Y., Zhao, P., Gao, B., Yuan, M., Yu, J., Wang, Z., et al. (2023). Self-reduction of bimetallic nanoparticles on flexible MXene-graphene electrodes for simultaneous detection of ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid. Microchem. J. 185, 108177. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2022.108177

Xu, B., Zhi, C., and Shi, P. (2020). Latest advances in MXene biosensors. J. Phys. Mater. 3 (3), 031001. doi:10.1088/2515-7639/ab8f78

Yang, G., Li, L., Lee, W. B., and Ng, M. C. (2018). Structure of graphene and its disorders: a review. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 19 (1), 613–648. doi:10.1080/14686996.2018.1494493

Ye, R., James, D. K., and Tour, J. M. (2018). Laser-induced graphene. Accounts Chem. Res. 51 (7), 1609–1620. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00084

Zhang, S., Zheng, J., Lin, J., Li, Y., Bao, Z., Peng, X., et al. (2023). Doped-nitrogen enhanced the performance of Nb2CTx on the electrocatalytic synthesis of H2O2. Nano Res. 16 (5), 6120–6127. doi:10.1007/s12274-022-5051-6

Zhu, M., Zeng, C., and Ye, J. (2011). Graphene-modified carbon fiber microelectrode for the detection of dopamine in mice Hippocampus tissue. Electroanalysis 23 (4), 907–914. doi:10.1002/elan.201000712

Keywords: dopamine, point-of-care, laser-induced graphene, MXene, polypyrrole, iron nanoparticles, electrochemical sensing

Citation: Shinde M and Slaughter G (2025) Advanced nanocomposite-based electrochemical sensor for ultra-sensitive dopamine detection in physiological fluids. Front. Lab Chip Technol. 4:1549365. doi: 10.3389/frlct.2025.1549365

Received: 21 December 2024; Accepted: 14 March 2025;

Published: 25 March 2025.

Edited by:

Felismina Moreira, Polytechnic Institute, PortugalReviewed by:

Abraham Samuel Finny, Waters Corporation, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Shinde and Slaughter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gymama Slaughter, Z3NsYXVnaHRAb2R1LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.