94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 03 March 2025

Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1531249

This article is part of the Research Topic Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Novel Treatment Strategies - Volume III View all 19 articles

Background: Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) has emerged as a promising treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, the safety profiles of HAIC and its various combination therapies remain to be systematically evaluated.

Methods: We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases from inception to November 2024. Studies reporting adverse events (AEs) of HAIC monotherapy or combination therapies in HCC were included. The severity and frequency of AEs were analyzed according to different treatment protocols.

Results: A total of 58 studies (11 prospective, 47 retrospective) were included. HAIC monotherapy demonstrated relatively mild toxicity, primarily affecting hepatobiliary (transaminase elevation 53.2%, hypoalbuminemia 57.2%) and hematological systems (anemia 43.0%, thrombocytopenia 35.2%). HAIC with targeted therapy showed increased adverse events, including characteristic reactions like hand-foot syndrome (48.0%) and hypertension (49.9%). HAIC combined with targeted, and immunotherapy exhibited the highest adverse reaction rates (neutropenia 82.9%, transaminase elevation 97.1%), while HAIC with anti-angiogenic and immunotherapy showed a relatively favorable safety profile. Prospective studies consistently reported higher incidence rates than retrospective studies, suggesting potential underreporting in clinical practice.

Conclusions: Different HAIC-based regimens exhibit distinct safety profiles requiring individualized management approaches. We propose a comprehensive framework for patient selection, monitoring strategies, and AE management. These recommendations aim to optimize treatment outcomes while minimizing adverse impacts on patient quality of life.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide (1). In China, HCC not only maintains a high incidence rate but also shows a clear trend toward younger age groups, with new cases accounting for over 50% of the global total (2). Despite advances in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, the prognosis remains poor (3, 4). While surgical resection represents the most effective curative treatment for HCC, only approximately 30% of patients are eligible for surgery, primarily due to advanced disease stage at diagnosis or insufficient liver function reserve (5). Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) enables high concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents in tumor tissues while reducing systemic exposure through arterial administration (6). This localized delivery strategy not only enhances local drug concentrations but also reduces systemic adverse reactions, making it an important option for treating unresectable HCC (7).

In recent years, with the continuous development of targeted therapy and immunotherapy, HAIC-based combination treatment strategies have become increasingly diverse (8). From HAIC monotherapy to HAIC combined with targeted therapy, and further to HAIC + targeted/anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy, the complexity and efficacy of treatment regimens have steadily improved (9–12). However, as combination therapy protocols expand, the spectrum of adverse reactions has changed significantly, presenting new safety challenges. In clinical practice, we have observed multi-system, multi-type adverse reactions, some of which may seriously affect patients’ treatment progress and prognosis. Currently, there is a lack of systematic review of the characteristics of adverse reactions and management strategies for HAIC and its combination therapies.

This review aims to summarize the characteristics of adverse reactions associated with HAIC and its various combination therapies through comprehensive analysis of existing research data and propose targeted management strategy recommendations. We hope that through this study, we can provide clinicians with more comprehensive guidance for adverse reaction management, thereby optimizing the safety of treatment protocols, developing individualized monitoring and prevention strategies, improving early recognition and management of adverse reactions, and ultimately optimizing treatment selection and adjustment to enhance patient benefits.

This study systematically searched relevant literature published in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases from their inception until November 2024. The main search terms were: ((hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy [Title/Abstract]) OR (HAIC [Title/Abstract])) AND (hepatocellular carcinoma [Title/Abstract]). Additionally, to ensure search completeness, we supplemented with the strategy: ((“HAIC”) OR (“hepatic artery infusion”)) AND (“hepatocellular carcinoma” OR “liver cancer” OR “HCC”).

Inclusion criteria: (1) Clinical studies, including prospective and retrospective studies; (2) Study subjects were primary HCC patients; (3) Treatment protocols included HAIC monotherapy or combination therapy; (4) Complete adverse reaction data were reported; (5) Publications in English. Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies lacking adverse reaction data; (2) Duplicate publications; (3) Infusion protocols not based on oxaliplatin + 5-FU; (4) Sample size <5. For the systemic chemotherapy group, patients received FOLFOX4 regimen consisting of oxaliplatin 85 mg/m² administered intravenously (IV) on day 1, leucovorin (LV) 200 mg/m² IV infusion from hour 0 to 2 on days 1 and 2, followed by 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 400 mg/m² IV bolus at hour 2, and then 5-FU 600 mg/m² as a 22-hour continuous IV infusion on days 1 and 2. This regimen was repeated every 2 weeks. For the HAIC group, treatment consisted of hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin 85 mg/m², leucovorin 400 mg/m², and 5-fluorouracil 400 mg/m² as a bolus on day 1, followed by 5-fluorouracil 2400 mg/m² as a 24/46-hour continuous infusion. This regimen was administered every 3 weeks. All literature was independently screened by two researchers, with disagreements resolved through discussion.

The following information was extracted from included studies: (1) Specific treatment protocols; (2) Incidence and grading of adverse reactions; (3) Management measures for adverse reactions. All adverse reactions were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), categorized as mild-to-moderate (Grade I-II) and severe (Grade III-IV).

Studies were classified into four categories based on treatment protocols: HAIC monotherapy, HAIC + targeted therapy, HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy, and HAIC + anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy. Adverse reactions were categorized by organ systems, including hematological (leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia), hepatobiliary (transaminase elevation, bilirubin elevation, hypoalbuminemia), gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain), cardiovascular (hypertension), dermatological (hand-foot syndrome, rash), neurological (sensory neuropathy), and immune-related adverse reactions (RCCEP, hypothyroidism, immune hepatitis, etc.).

Descriptive statistical methods were used, with adverse reaction rates expressed as median and range (minimum-maximum). The top 20 high-incidence adverse reactions were analyzed in detail, with stratified analysis by system classification and severity. Analysis focused on: (1) Main adverse reaction spectrum of each treatment protocol; (2) Identification of high-incidence adverse reactions; (3) Characteristics of severe adverse reactions; (4) Newly emerging characteristic adverse reactions; (5) Toxicity accumulation effects of combination therapy. R software (R 4.2.2) was used for visualization.

This study included 58 studies, comprising 11 prospective clinical (9–11, 13–20) studies and 47 retrospective clinical studies (12, 21–67). Adverse reactions primarily involved hematological, hepatobiliary, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, dermatological, neurological systems, and immune-related reactions. Overall, hematological and hepatobiliary adverse reactions were most common, followed by gastrointestinal reactions. As treatment protocols became more complex, the spectrum of adverse reactions gradually expanded, with corresponding increases in characteristic adverse reactions.

Prospective clinical studies (11) and retrospective studies (47) showed consistency in adverse reaction distribution patterns, with similar rankings of major adverse reactions. In HAIC monotherapy, both types of studies showed hepatobiliary (transaminase elevation, hypoalbuminemia) and hematological (anemia, thrombocytopenia) adverse reactions as most common; in combination therapy protocols, both demonstrated characteristic adverse reactions (such as targeted therapy-related hand-foot syndrome, immunotherapy-related RCCEP). However, there were significant differences in adverse reaction incidence rates between the two types of studies.

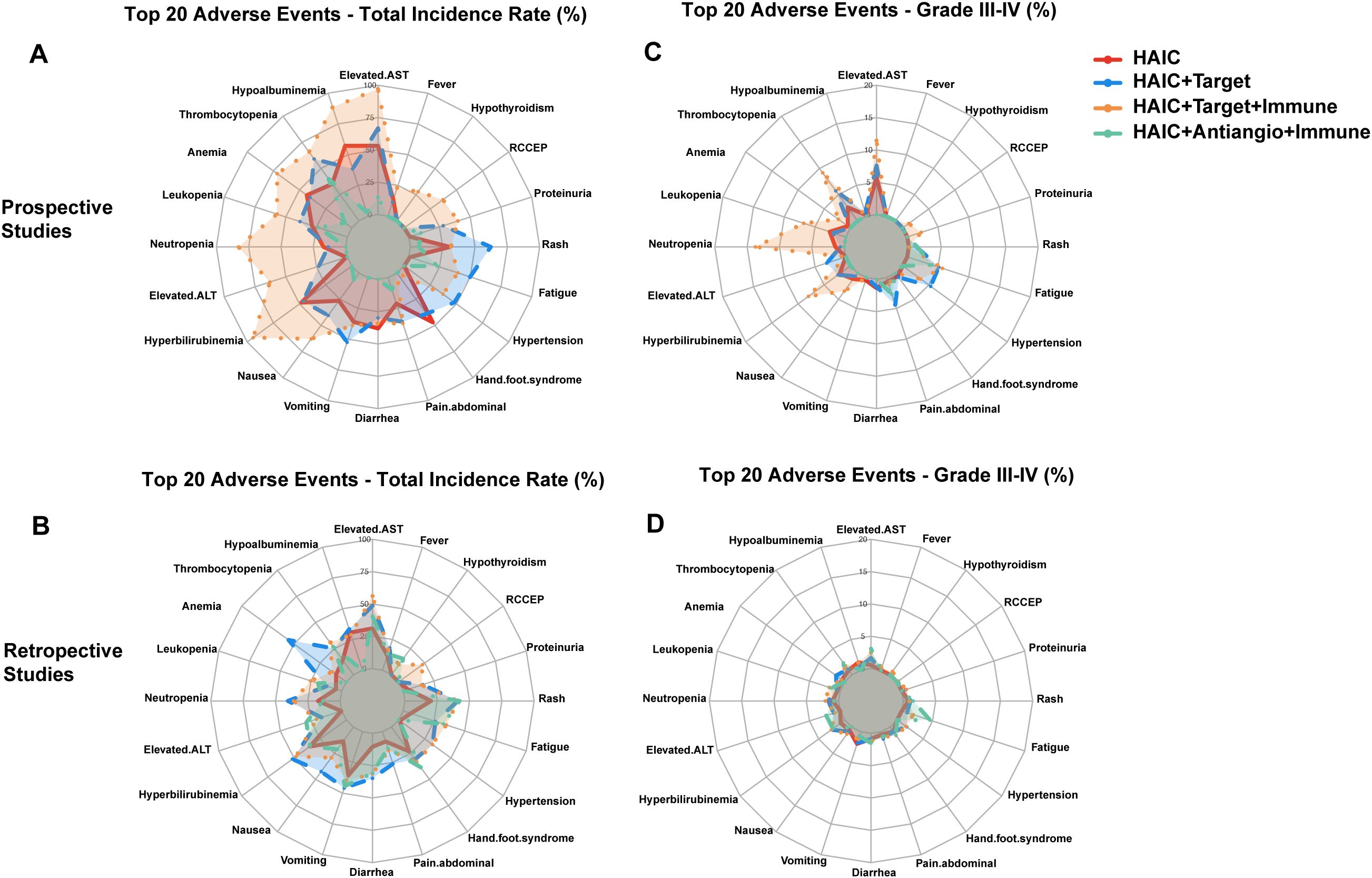

Prospective studies generally reported higher incidence rates of adverse reactions compared to retrospective studies. Taking HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy as an example, neutropenia (82.9% vs 36.1%), thrombocytopenia (65.7% vs 30.8%), and transaminase elevation (97.1% vs 56.1%) all showed significant differences (Figure 1A). Differences in Grade III-IV adverse reactions were equally notable, such as neutropenia (34.3% vs 5.2%) and transaminase elevation (28.6% vs 6.3%) (Figure 1B). This difference in incidence rates, while maintaining relatively consistent distribution characteristics of adverse reactions, suggests that prospective studies may have obtained more complete safety data.

Figure 1. Comparison of adverse reaction rates between prospective and retrospective studies. (A) Radar chart comparing overall adverse reaction rates; (B) Radar chart comparing Grade III-IV adverse reaction rates.

Different treatment protocols showed unique distribution characteristics of adverse reactions through radar chart analysis, with the spectrum of adverse reactions gradually expanding and severity increasing from HAIC monotherapy to multi-drug combination therapy. Given that adverse reactions are more comprehensively documented in prospective clinical trials, we conducted comparative analyses of adverse events between HAIC-based regimens and various standard treatments including systemic chemotherapy (FOLFOX4), targeted therapy, targeted therapy + immunotherapy, and anti-angiogenic therapy + immunotherapy.

HAIC monotherapy demonstrated a relatively mild adverse reaction spectrum. Adverse reactions primarily involved hepatobiliary and hematological systems, showing a “dual-peak” distribution. Prospective studies revealed that hepatobiliary manifestations mainly included transaminase elevation (53.2%) and hypoalbuminemia (57.2%), while hematological manifestations primarily included anemia (43.0%) and thrombocytopenia (35.2%) (Figure 2A). Although retrospective studies showed lower incidence rates, the distribution characteristics were similar, with transaminase elevation (31.1%) and thrombocytopenia (14.1%) remaining the primary manifestations. Gastrointestinal reactions such as nausea (35.9%), vomiting (38.0%), and abdominal pain (47.0%), although not infrequent, were almost entirely mild to moderate, with good overall patient tolerability (Figure 2B). Grade III-IV adverse reactions showed a “low-level dispersed” distribution, with only transaminase elevation reaching 14.5%, while others remained below 10% (Figures 2C, D).

Figure 2. Comparison of adverse reaction rates across HAIC and its combination therapies. (A) Overall incidence rates - prospective studies (B) Overall incidence rates - retrospective studies. (C) Grade III-IV adverse reaction rates - prospective studies (D) Grade III-IV adverse reaction rates - retrospective studies.

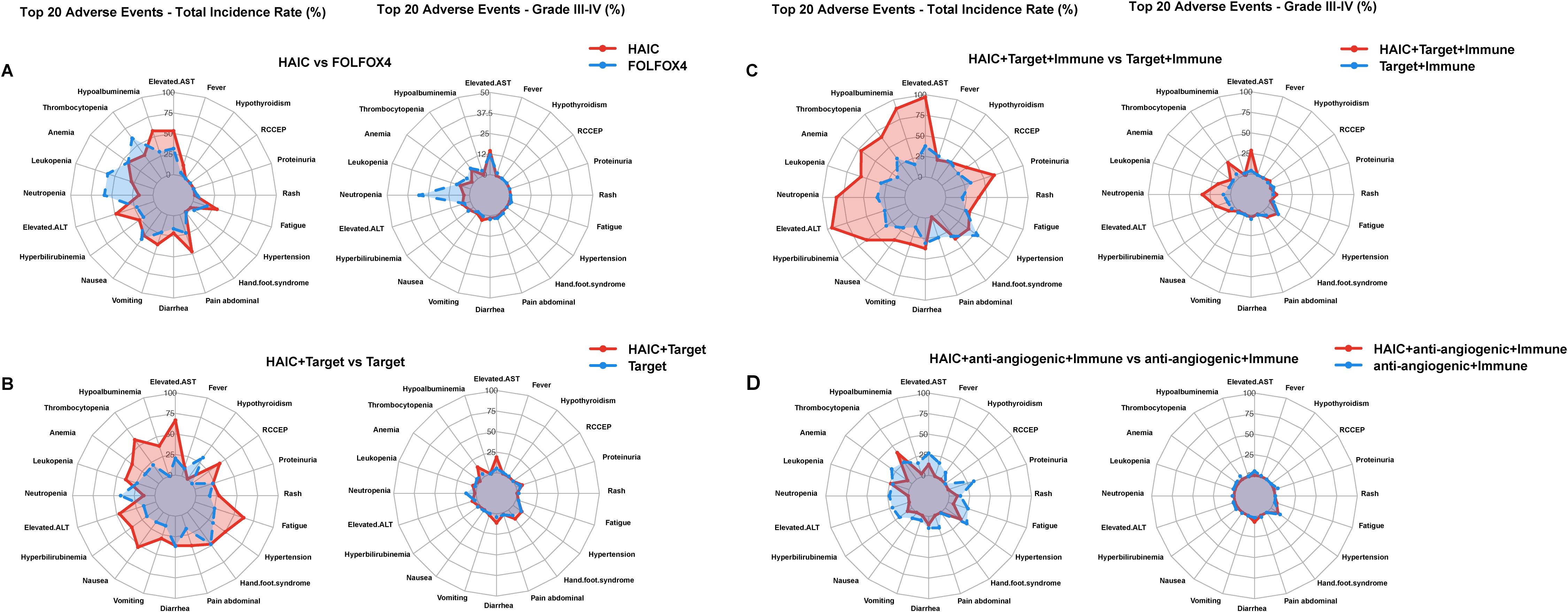

Compared to intravenous chemotherapy, HAIC demonstrated a milder adverse reaction profile with better tolerability (68, 69). While intravenous chemotherapy (FOLFOX4) showed higher incidences of hematological toxicity, including neutropenia (59.02%) and thrombocytopenia (60.66%), HAIC primarily involved hepatobiliary toxicity, such as transaminase elevation (53.2%) and hypoalbuminemia (57.2%). Notably, HAIC had significantly fewer Grade III-IV adverse reactions, with transaminase elevation at 14.5% as the most common, while severe hematological toxicities were rare (e.g., neutropenia 3.4%). In contrast, FOLFOX4 demonstrated a markedly higher rate of severe adverse reactions, particularly neutropenia (30.6%) and thrombocytopenia (7.65%), highlighting its stronger bone marrow suppressive effects (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Comparison of adverse reaction rates across HAIC and its other therapies. (A) Overall and Grade III-IV Adverse Events: HAIC versus FOLFOX4 in prospective studies; (B) Overall and Grade III-IV Adverse Events: HAIC + targeted versus targeted in prospective studies; (C) Overall and Grade III-IV Adverse Events: HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy versus targeted + immunotherapy in prospective studies; (D) Overall and Grade III-IV Adverse Events: HAIC + anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy versus anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy in prospective studies.

When HAIC was combined with targeted agents, both prospective and retrospective study data showed significantly expanded adverse reaction spectra, presenting a “multi-system balanced” distribution (Figures 2A, B). First, the incidence of thrombocytopenia increased significantly to 59.0%, with Grade III-IV reaching 14.3%; transaminase elevation increased to 66.7%, with Grade III-IV at 18.9%. Additionally, characteristic adverse reactions specific to targeted therapy emerged: hand-foot syndrome (48.0%, with Grade III-IV at 13.4%) and hypertension (49.9%, Grade III-IV at 12.8%) became issues requiring special attention. The incidence of fatigue (62.2%) also increased significantly compared to monotherapy (Figures 2C, D). Although overall adverse reaction rates increased, most remained controllable Grade I-II reactions.

Comparative analysis between HAIC + targeted therapy versus targeted therapy alone demonstrated distinct safety patterns (70–77). The HAIC combination showed higher incidences in several adverse events, particularly in hepatic dysfunction (elevated transaminases: 66.7% vs 20.35%, grade III-IV: 18.9% vs 5.3%) and certain hematological toxicities, especially thrombocytopenia (59.0% vs 21.1%, grade III-IV: 14.3% vs 4.1%). Interestingly, neutropenia was less frequent in the HAIC combination group (13.5% vs 41.5%, grade III-IV: 1.5% vs 12.0%). Gastrointestinal reactions showed varied patterns, with notably higher rates of nausea (52.5% vs 14.7%) but similar rates of diarrhea (35.8% vs 36.5%). The HAIC combination also resulted in increased incidences of fatigue (62.2% vs 25.0%) and hypertension (49.9% vs 31.5%). Although most adverse events remained grade I-II, these findings suggest that while the combination strategy may potentially offer therapeutic benefits, it requires careful monitoring, especially for hepatic function and platelet counts (Figure 3B).

HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy demonstrated the most complex adverse reaction characteristics, showing an “overall elevation” pattern (Figures 2A, B). The most significant changes were substantial increases in hematological toxicity: neutropenia reached 82.9%, leukopenia 57.1%, and anemia 71.4%. Liver function abnormalities reached peak levels, with transaminase and ALT elevations reaching 97.1% and 94.3%, respectively. Meanwhile, immune-related adverse reactions emerged as new challenges, including RCCEP (37.1%), hypothyroidism (27.8%), and immune-related dermatitis (16.7%). Furthermore, regarding more serious complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding, the incidence increased from 1.9% in the HAIC monotherapy group to 7.7% in the HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy group, with a notable increase in Grade III-IV bleeding (3.6%) (Figures 2C, D). This difference may be related to the additional effects of immunotherapy and anti-angiogenic therapy on gastrointestinal mucosa.

Grade III-IV adverse reactions showed a “prominent peak” pattern, with neutropenia (34.3%) and transaminase elevation (28.6%) showing markedly increased incidence rates. Although overall adverse reaction rates were highest, most were Grade I-II reactions, with relatively controllable proportions of Grade III-IV reactions.

Comparative analysis between HAIC + targeted therapy + immunotherapy versus targeted therapy + immunotherapy demonstrated notably increased adverse events (78–86). The HAIC combination showed significantly higher incidences of hepatic dysfunction (elevated transaminases: 97.1% vs 37.5%, grade III-IV: 28.6% vs 4.15%) and hematological toxicities, particularly in neutropenia (82.9% vs 33.3%, grade III-IV: 34.3% vs 8.75%), leukopenia (57.1% vs 31.55%, grade III-IV: 17.1% vs 3.1%), and thrombocytopenia (65.7% vs 33.55%, grade III-IV: 22.9% vs 5.8%). The combination also led to increased rates of hypoalbuminemia (88.6% vs 17.3%). Gastrointestinal reactions showed a similar pattern of elevation, with higher rates of nausea (38.9% vs 20.5%) and vomiting (34.3% vs 13.0%). While most adverse events remained at grade I-II, the substantial increase in grade III-IV events, particularly in hematological and hepatic parameters, suggests the need for more intensive monitoring and management strategies (Figure 3C).

Limited data is available for this combination therapy. Compared to other combination regimens, this showed milder toxicity characteristics, presenting a “relatively concentrated” pattern. Overall adverse reaction rates were significantly lower compared to other combination protocols (Figures 2A, B). Hematological toxicity was relatively mild, with leukopenia at only 23.3% and no Grade III-IV adverse reactions; liver function-related adverse reactions also decreased significantly, with transaminase elevation at only 13.3%. Special attention was required for hypertension (23.3%, Grade III-IV 10%) and proteinuria (28.8%). Gastrointestinal reactions were generally controllable, with diarrhea occurring in 10% of cases, including 6.7% Grade III-IV (Figures 2C, D). However, current data on this aspect is limited, possibly due to economic factors.

In contrast to other combination approaches, HAIC + anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy demonstrated unique safety characteristics (87–92). Unexpectedly, this combination showed lower incidence rates of adverse events in several aspects compared to anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy. Notably, reduced frequencies were observed in hepatic dysfunction (elevated transaminases: 13.3% vs 26.9%), anemia (6.7% vs 30.55%), and fatigue (6.7% vs 25.2%), suggesting better tolerability. The only markedly increased adverse event was thrombocytopenia (40.0% vs 25.8%). Furthermore, grade III-IV adverse events were relatively infrequent, with hypertension being the primary concern (10.0%). These findings suggest that HAIC plus anti-angiogenic and immunotherapy might represent a relatively well-tolerated treatment option, although careful monitoring of thrombocytopenia and hypertension remains essential (Figure 3D).

Based on the analysis of adverse reaction characteristics of HAIC and its combination therapies, we need to establish systematic management strategies, from patient selection to continuous monitoring, to ensure treatment safety and efficacy.

Patient baseline status is a key consideration when selecting treatment protocols. For patients with good liver function reserve and no significant underlying diseases, HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy may provide maximum benefit. However, this protocol has higher adverse reaction rates (neutropenia 82.9%, transaminase elevation 97.1%), and the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy requires caution in patients with high-risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding. Nevertheless, these adverse reactions are mostly controllable through standardized management. For patients with certain underlying diseases or moderate liver function reserve, HAIC combined with targeted therapy may be more suitable, with primary focus on specific adverse reactions such as hand-foot syndrome (48.0%) and hypertension (49.9%). For high-risk patients (poor liver function reserve or significant underlying diseases), HAIC monotherapy’s mild adverse reaction profile (transaminase elevation 53.2%, thrombocytopenia 35.2%) makes it a better choice.

Further research on the mechanisms of adverse reactions and their prevention is needed. For instance, a retrospective study showed that 64.6% of patients experienced abdominal pain during HAIC, possibly due to vascular spasm caused by oxalate (a degradation product of oxaliplatin) irritating blood vessels, or insufficient hepatic blood supply due to small vessel diameter (32). Effective pain management and the use of lidocaine for antispasmodic effects during infusion can effectively relieve abdominal pain during treatment.

Management of adverse reactions should be based on severity level. Grade I-II adverse reactions usually allow continued treatment with symptomatic support; Grade III reactions require considering treatment suspension or dose adjustment, with gradual resumption after improvement; Grade IV reactions require immediate drug discontinuation and active treatment. Specific monitoring plans should be developed for characteristic adverse reactions of different treatment protocols (Figure 4):

● HAIC: Focus on monitoring complete blood count and liver function

● HAIC + targeted therapy: Enhanced monitoring of hand-foot syndrome and blood pressure

● HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy: Comprehensive monitoring plan, especially for immune-related adverse reactions and gastrointestinal bleeding

● HAIC + anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy: Focus on blood pressure and proteinuria

Successful treatment requires a comprehensive long-term management system. First, establish standardized follow-up protocols, including regular efficacy assessment and adverse reaction monitoring. Second, enhance patient education to improve awareness of early adverse reaction symptoms, promoting early detection and management. Finally, maintain good physician-patient communication to ensure timely handling of problems.

This stratified management strategy should be based on standardized monitoring. Set appropriate monitoring items and frequencies according to different treatment protocols, including routine hematological examinations, biochemical indicator monitoring, and screening for specific adverse reactions. Meanwhile, regularly evaluate treatment effectiveness and adjust treatment protocols based on patient tolerance and response.

Overall, management of HAIC and its combination therapies should be an individualized and dynamically adjusted process. Through reasonable protocol selection, systematic monitoring systems, and timely intervention measures, adverse reactions’ impact can be minimized while ensuring treatment effectiveness and improving patient quality of life. Importantly, the higher adverse reaction rates shown in prospective studies suggest that we may need closer monitoring in actual clinical work to detect and address potential problems promptly.

As HAIC and its combination therapy protocols become widely used in HCC treatment, there remains room for further optimization in understanding and managing adverse reactions. The main limitation of current research lies in the significant data discrepancy between prospective and retrospective studies, suggesting potential inadequacies in adverse reaction monitoring and reporting in actual clinical work. For example, the reported incidence of leukopenia in prospective studies (28.8%) is much higher than in retrospective studies (4.7%), indicating the need for more standardized adverse reaction monitoring and reporting systems.

Future research should focus on several aspects: First, more high-quality prospective studies are needed to validate the safety characteristics of different combination protocols. Particularly for new combination protocols such as HAIC + anti-angiogenic + immunotherapy, their relatively low adverse reaction rates require more data support. Second, research on predictive factors and early identification indicators for immune-related adverse reactions is also important, which will help improve the safety of immunotherapy-containing protocols such as HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy. Finally, establishing standardized adverse reaction assessment systems to promote multi-center data comparability and reliability is crucial.

Regarding optimization of management strategies, there is a need to explore more individualized treatment selection criteria and establish prediction models based on patient characteristics for more accurate assessment of adverse reaction risks. Meanwhile, with the development of telemedicine technology, consideration should be given to establishing more convenient adverse reaction monitoring and follow-up systems to improve management efficiency.

Through systematic analysis of adverse reaction data from HAIC and its combination therapy protocols, this review finds that different treatment combinations have their unique safety characteristics. HAIC monotherapy shows a relatively mild adverse reaction spectrum, mainly manifesting as controllable hematological toxicity and liver function abnormalities. HAIC combined with targeted therapy adds specific reactions such as hand-foot syndrome and hypertension to the basic adverse reactions. Although HAIC + targeted + immunotherapy has the highest adverse reaction rates, most are controllable Grade I-II reactions. HAIC combined with anti-angiogenic and immunotherapy shows relatively favorable safety characteristics, providing a new option for specific patient populations.

The higher adverse reaction rates generally reported in prospective studies, compared to retrospective studies, more closely reflect real clinical situations, suggesting the need for more cautious and standardized monitoring strategies in actual practice. Based on these findings, we recommend individualized treatment selection and stratified management strategies, including protocol selection based on patient characteristics, systematic monitoring plans, and timely intervention measures.

For clinical practice, we recommend: First, strictly evaluate patient baseline status to select appropriate treatment protocols; second, establish comprehensive monitoring systems for early detection and timely intervention; finally, maintain regular follow-up and dynamically adjust treatment strategies. Only through such systematic management can we ensure treatment effectiveness while maximizing control of adverse reactions’ impact and improving patient benefits.

In the future, with the accumulation of more high-quality research data and optimization of management strategies, the application of HAIC and its combination therapies in HCC treatment will become more standardized and individualized, providing safer and more effective treatment options for patients.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, although we conducted a comprehensive review of adverse events across different treatment protocols, some relevant literature might have been missed despite our best efforts to minimize selection bias. Second, the heterogeneous nature of the source data, particularly the limited number of studies for certain combination therapies, may have introduced statistical bias in our comparative analyses. Third, baseline characteristics of patients varied across different studies, potentially confounding the comparison of adverse event profiles. Fourth, the safety data for some combination therapies, especially HAIC plus anti-angiogenic and immunotherapy, remains limited and requires further validation through larger, prospective clinical trials. These limitations underscore the need for more standardized, prospective studies with uniform adverse event reporting criteria to better evaluate the safety profiles of various HAIC-based combination therapies.

YW: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. ZZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. SC: Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. DZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. GT: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. DD: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (No. SZXK052).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, Salem R, Saborowski A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. (2022) 400:1345–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01200-4

2. Wang Y, Yan Q, Fan C, Mo Y, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Overview and countermeasures of cancer burden in China. Sci China. Life Sci. (2023) 66:2515–26. doi: 10.1007/s11427-022-2240-6

3. Li J, Liang YB, Wang QB, Li YK, Chen XM, Luo WL, et al. Tumor-associated lymphatic vessel density is a postoperative prognostic biomarker of hepatobiliary cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1519999. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1519999

4. Li YK, Wu S, Wu YS, Zhang WH, Wang Y, Li YH, et al. Portal venous and hepatic arterial coefficients predict post-hepatectomy overall and recurrence-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2024) 11:1389–402. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S462168

5. Maki H, Hasegawa K. Advances in the surgical treatment of liver cancer. Biosci Trends. (2022) 16:178–88. doi: 10.5582/bst.2022.01245

6. Sidaway P. HAIC-FO improves outcomes in HCC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2022) 19:150. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00599-0

7. Iwamoto H, Shimose S, Shirono T, Niizeki T, Kawaguchi T. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of chemo-diversity. Clin Mol Hepatol. (2023) 29:593–604. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2022.0391

8. Zheng K, Wang X. Techniques and status of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for primary hepatobiliary cancers. Ther Adv Med Oncol. (2024) 16:17588359231225040. doi: 10.1177/17588359231225040

9. Lyu N, Wang X, Li JB, Lai JF, Chen QF, Li SL, et al. Arterial chemotherapy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A biomolecular exploratory, randomized, phase III trial (FOHAIC-1). J Clin Oncol. (2022) 40:468–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01963

10. Zhang TQ, Geng ZJ, Zuo MX, Li JB, Huang JH, Huang ZL, et al. Camrelizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) plus apatinib (an VEGFR-2 inhibitor) and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C (TRIPLET): a phase II study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:413. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01663-6

11. Li QJ, He MK, Chen HW, Fang WQ, Zhou YM, Xu L, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus transarterial chemoembolization for large hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. (2022) 40:150–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00608

12. Huang Z, Chen T, Li W, He W, Liu S, Wu Z, et al. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab plus transarterial chemoembolization and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for patients with high tumor burden unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A multi-center cohort study. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 139:112711. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112711

13. Chen S, Wang X, Yuan B, Peng J, Zhang Q, Yu W, et al. Apatinib plus hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin and raltitrexed for hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: phase II trial. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:8857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52700-z

14. He MK, Le Y, Li QJ, Yu ZS, Li SH, Wei W, et al. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy using mFOLFOX versus transarterial chemoembolization for massive unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective non-randomized study. Chin J Cancer. (2017) 36:83. doi: 10.1186/s40880-017-0251-2

15. Lai Z, He M, Bu X, Xu Y, Huang Y, Wen D, et al. Lenvatinib, toripalimab plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in patients with high-risk advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A biomolecular exploratory, phase II trial. Eur J Cancer. (2022) 174:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.07.005

16. He MK, Zou RH, Li QJ, Zhou ZG, Shen JX, Zhang YF, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib combined with concurrent hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with major portal vein thrombosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. (2018) 41:734–43. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1874-z

17. Li SH, Mei J, Cheng Y, Li Q, Wang QX, Fang CK, et al. Postoperative adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX in hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: A multicenter, phase III, randomized study. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:1898–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01142

18. Liu D, Mu H, Liu C, Zhang W, Cui Y, Wu Q, et al. Sintilimab, bevacizumab biosimilar, and HAIC for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma conversion therapy: a prospective, single-arm phase II trial. Neoplasma. (2023) 70:811–8. doi: 10.4149/neo_2023_230806N413

19. Zheng K, Zhu X, Fu S, Cao G, Li WQ, Xu L, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma with major portal vein tumor thrombosis: A randomized trial. Radiology. (2022) 303:455–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.211545

20. He M, Li Q, Zou R, Shen J, Fang W, Tan G, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin vs sorafenib alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2019) 5:953–60. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0250

21. Wang W, Li R, Li H, Wang M, Wang J, Wang X, et al. Addition of immune checkpoint inhibitor showed better efficacy for infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma receiving hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy and lenvatinib: A multicenter retrospective study. Immunotargets Ther. (2024) 13:399–412. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S470797

22. Yuan W, Yue W, Wen H, Wang X, Wang Q. Analysis on efficacy of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy with or without lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Surg Res. (2023) 64:268–77. doi: 10.1159/000529475

23. Mei J, Li SH, Li QJ, Sun XQ, Lu LH, Lin WP, et al. Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy improves the efficacy of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2021) 8:167–76. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S298538

24. Xiao Y, Deng W, Luo L, Zhu G, Xie J, Liu Y, et al. Beneficial effects of maintaining liver function during hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with tyrosine kinase and programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitors on the outcomes of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. (2024) 24:588. doi: 10.1186/s12885-024-12355-x

25. Chen Y, Jia L, Li Y, Cui W, Wang J, Zhang C, et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of transarterial chemoembolization: hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy plus tyrosine kinase inhibitors with or without programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitors for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma-A retrospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. (2024) 31:7860–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-024-15933-2

26. Lin Z, Chen D, Hu X, Huang D, Chen Y, Zhang J, et al. Clinical efficacy of HAIC (FOLFOX) combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors vs. TACE combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus and arterioportal fistulas. Am J Cancer Res. (2023) 13:5455–65.

27. Lin ZP, Hu XL, Chen D, Zou XG, Zhong H, Xu SX, et al. Clinical efficacy of targeted therapy, immunotherapy combined with hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (FOLFOX), and lipiodol embolization in the treatment of unresectable hepatocarcinoma. J Physiol Pharmacol. (2022) 73. doi: 10.26402/jpp.2022.6.08

28. Liu B, Shen L, Liu W, Zhang Z, Lei J, Li Z, et al. Clinical therapy: HAIC combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitors versus HAIC alone for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2024) 11:1557–67. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S470345

29. Pan Y, Wang R, Hu D, Xie W, Fu Y, Hou J, et al. Comparative safety and efficacy of molecular-targeted drugs, immune checkpoint inhibitors, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy and their combinations in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: findings from advances in landmark trials. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). (2021) 26:873–81. doi: 10.52586/4994

30. Yang J, Shang X, Li J, Wei N. Comparative study on the efficacy and safety of transarterial chemoembolization combined with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for large unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. (2024) 15:346–55. doi: 10.21037/jgo-23-821

31. Chen S, Yuan B, Yu W, Wang X, He C, Chen C. Comparison of arterial infusion chemotherapy and chemoembolization for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter retrospective study. J Gastrointest Surg. (2022) 26:2292–300. doi: 10.1007/s11605-022-05421-x

32. Wu Z, Guo W, Chen S, Zhuang W. Determinants of pain in advanced hcc patients recieving hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy. Invest New Drugs. (2021) 39:394–9. doi: 10.1007/s10637-020-01009-x

33. Xin Y, Cao F, Yang H, Zhang X, Chen Y, Cao X, et al. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab combined with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:929141. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.929141

34. Long F, Chen S, Li R, Lin Y, Han J, Guo J, et al. Efficacy and safety of haic alone vs. Haic combined with lenvatinib for treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. (2023) 40:147. doi: 10.1007/s12032-023-02012-x

35. Yang M, Jiang X, Liu H, Zhang Q, Li J, Shao L, et al. Efficacy and safety of HAIC combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors versus HAIC monotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter propensity score matching analysis. Front Pharmacol. (2024) 15:1410767. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1410767

36. Zhang Y, Zhang H, Xu H, Wang Y, Feng L, Yi F. Efficacy and safety of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with lenvatinib and PD-1 inhibitors for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with macrovascular invasion. World J Surg Oncol. (2024) 22:122. doi: 10.1186/s12957-024-03396-4

37. Xu Y, Fu S, Mao Y, Huang S, Li D, Wu J. Efficacy and safety of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with programmed cell death protein-1 antibody and lenvatinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Med (Lausanne). (2022) 9:919069. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.919069

38. Liu Q, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Chen L, Yang Y, Liu Y. Efficacy and safety of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis in the main trunk. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1374149. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1374149

39. Lin LW, Ke K, Yan LY, Chen R, Huang JY. Efficacy and safety of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors plus programmed death-1 inhibitors for hepatocellular carcinoma refractory to transarterial chemoembolization. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1178428. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1178428

40. Lin ZP, Hu XL, Chen D, Huang DB, Zou XG, Zhong H, et al. Efficacy and safety of targeted therapy plus immunotherapy combined with hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (FOLFOX) for unresectable hepatocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. (2024) 30:2321–31. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i17.2321

41. Li Y, Liu W, Chen J, Chen Y, Guo J, Pang H, et al. Efficiency and safety of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) combined with anti-PD1 therapy versus HAIC monotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter propensity score matching analysis. Cancer Med. (2024) 13:e6836. doi: 10.1002/cam4.v13.1

42. Chang X, Li X, Sun P, Li Z, Sun P, Ning S. HAIC combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 versus lenvatinib plus PD-1 in patients with high-risk advanced HCC: A real-world study. BMC Cancer. (2024) 24:480. doi: 10.1186/s12885-024-12233-6

43. Li R, Wang X, Li H, Wang M, Wang J, Wang W, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined lenvatinib and PD-1 inhibitor showed improved survival for infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter cohort study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2024) 11:1727–40. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S477872

44. Liu G, Zhu D, He Q, Zhou C, He L, Li Z, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with lenvatinib and PD-1 inhibitors for managing arterioportal shunt in hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: A retrospective cohort study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2024) 11:1415–28. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S456460

45. Diao L, Wang C, You R, Leng B, Yu Z, Xu Q, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with lenvatinib and PD-1 inhibitors versus lenvatinib and PD-1 inhibitors for HCC refractory to TACE. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 39:746–53. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16463

46. Chang X, Wu H, Ning S, Li X, Xie Y, Shao W, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with lenvatinib plus humanized programmed death receptor-1 in patients with high-risk advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A real-world study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2023) 10:1497–509. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S418387

47. Mei J, Tang YH, Wei W, Shi M, Zheng L, Li SH, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with PD-1 inhibitors plus lenvatinib versus PD-1 inhibitors plus lenvatinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:618206. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.618206

48. Liang RB, Zhao Y, He MK, Wen DS, Bu XY, Huang YX, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without sorafenib as initial treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:619461. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.619461

49. Zuo M, Cao Y, Yang Y, Zheng G, Li D, Shao H, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy plus camrelizumab and apatinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. (2024) 18:1486–98. doi: 10.1007/s12072-024-10690-6

50. Chen S, Shi F, Wu Z, Wang L, Cai H, Ma P, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy plus lenvatinib and tislelizumab with or without transhepatic arterial embolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus and high tumor burden: A multicenter retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2023) 10:1209–22. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S417550

51. Wei Z, Wang Y, Wu B, Liu Y, Wang Y, Ren Z, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy plus lenvatinib with or without programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitors for advanced cholangiocarcinoma. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1235724. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1235724

52. Fu S, Xu Y, Mao Y, He M, Chen Z, Huang S, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, lenvatinib plus programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitors: A promising treatment approach for high-burden hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. (2024) 13:E7105. doi: 10.1002/cam4.v13.9

53. Huang Y, Zhang L, He M, Lai Z, Bu X, Wen D, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma refractory to transarterial chemoembolization: retrospective subgroup analysis of 2 prospective trials. Technol Cancer Res Treat. (2022) 21:15330338221117389. doi: 10.1177/15330338221117389

54. Li Y, Guo J, Liu W, Pang H, Song Y, Wu S, et al. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with camrelizumab plus rivoceranib for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis: a multicenter propensity score-matching analysis. Hepatol Int. (2024) 18:1286–98. doi: 10.1007/s12072-024-10672-8

55. Zhang B, Huang B, Yang F, Yang J, Kong M, Wang J, et al. High-risk hepatocellular carcinoma: hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus transarterial chemoembolization. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2024) 11:651–63. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S455953

56. Yoo JS, Kim JH, Cho HS, Han JW, Jang JW, Choi JY, et al. Higher objective responses by hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy following atezolizumab and bevacizumab failure than when used as initial therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study. Abdom Radiol (NY). (2024) 49:3127–35. doi: 10.1007/s00261-024-04308-6

57. Fu Y, Peng W, Zhang W, Yang Z, Hu Z, Pang Y, et al. Induction therapy with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy enhances the efficacy of lenvatinib and pd1 inhibitors in treating hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal vein tumor thrombosis. J Gastroenterol. (2023) 58:413–24. doi: 10.1007/s00535-023-01976-x

58. An C, Zuo M, Li W, Chen Q, Wu P. Infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: transcatheter arterial chemoembolization versus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:747496. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.747496

59. Guan R, Zhang N, Deng M, Lin Y, Huang G, Fu Y, et al. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma extrahepatic metastases can benefit from hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with lenvatinib plus programmed death-1 inhibitors. Int J Surg. (2024) 110:4062–73. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000001378

60. Wang D, Zhang Z, Yang L, Zhao L, Liu Z, Lou C. Pd-1 inhibitors combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors with or without hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of hbv-related advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2024) 11:1157–70. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S457527

61. Xiao Y, Zhu G, Xie J, Luo L, Deng W, Lin L, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic biomarkers in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with lenvatinib and camrelizumab. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2023) 10:2049–58. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S432134

62. An C, Yao W, Zuo M, Li W, Chen Q, Wu P. Pseudo-capsulated hepatocellular carcinoma: hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Acad Radiol. (2024) 31:833–43. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2023.06.021

63. Liu BJ, Gao S, Zhu X, Guo JH, Kou FX, Liu SX, et al. Real-world study of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy and tyrosine kinase inhibitors for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunotherapy. (2021) 13:1395–405. doi: 10.2217/imt-2021-0192

64. Tang HH, Zhang MQ, Zhang ZC, Fan C, Jin Y, Wang WD. The safety and efficacy of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with PD-(L)1 inhibitors and molecular targeted therapies for the treatment of intermediate and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma unsuitable for transarterial chemoembolization. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2023) 10:2211–21. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S441024

65. Zhao Y, Lai J, Liang R, He M, Shi M. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with oxaliplatin versus sorafenib alone for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Interv Med. (2019) 2:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jimed.2019.07.005

66. Xu YJ, Lai ZC, He MK, Bu XY, Chen HW, Zhou YM, et al. Toripalimab combined with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus lenvatinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat. (2021) 20:15330338211063848. doi: 10.1177/15330338211063848

67. Yu B, Zhang N, Feng Y, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Wang L. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors plus anti-PD-1 antibodies with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy or transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2023) 10:1735–48. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S431917

68. Qin S, Bai Y, Lim HY, Thongprasert S, Chao Y, Fan J, et al. Randomized, multicenter, open-label study of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin versus doxorubicin as palliative chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma from Asia. J Clin Oncol. (2013) 31:3501–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5643

69. Qin S, Cheng Y, Liang J, Shen L, Bai Y, Li J, et al. Efficacy and safety of the FOLFOX4 regimen versus doxorubicin in Chinese patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a subgroup analysis of the EACH study. Oncologist. (2014) 19:1169–78. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0190

70. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2017) 389:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9

71. Bruix J, Tak WY, Gasbarrini A, Santoro A, Colombo M, Lim HY, et al. Regorafenib as second-line therapy for intermediate or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicentre, open-label, phase II safety study. Eur J Cancer. (2013) 49:3412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.05.028

72. Casadei-Gardini A, Rimini M, Tada T, Suda G, Shimose S, Kudo M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A large real-life worldwide population. Eur J Cancer. (2023) 180:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.11.017

73. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the asia-pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. (2009) 10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7

74. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2018) 391:1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1

75. Qin S, Bi F, Gu S, Bai Y, Chen Z, Wang Z, et al. Donafenib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomized, open-label, parallel-controlled phase II-III trial. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39:3002–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00163

76. Qin S, Li Q, Gu S, Chen X, Lin L, Wang Z, et al. Apatinib as second-line or later therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (AHELP): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 6:559–68. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00109-6

77. Vogel A, Qin S, Kudo M, Su Y, Hudgens S, Yamashita T, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib for first-line treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: patient-reported outcomes from A randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 6:649–58. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00110-2

78. Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, et al. Phase ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:2960–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00808

79. Kim HD, Jung S, Lim HY, Ryoo BY, Ryu MH, Chuah S, et al. Regorafenib plus nivolumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: the phase 2 RENOBATE trial. Nat Med. (2024) 30:699–707. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02824-y

80. Llovet JM, Kudo M, Merle P, Meyer T, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib plus placebo for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Leap-002): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2023) 24:1399–410. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00469-2

81. Lv Z, Xiang X, Yong JK, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Li L, et al. Pembrolizumab in combination with LEnvatinib in participants with hepatocellular carcinoma before liver transplant as Neoadjuvant TherapY-PLENTY pilot study. Int J Surg. (2024) 110:6647–57. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000001813

82. Mei K, Qin S, Chen Z, Liu Y, Wang L, Zou J. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in second-line or above therapy for advanced primary liver cancer: cohort A report in a multicenter phase Ib/II trial. J Immunother Cancer. (2021) 9. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002191

83. Qin S, Chan SL, Gu S, Bai Y, Ren Z, Lin X, et al. Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (CARES-310): a randomised, open-label, international phase 3 study. Lancet. (2023) 402:1133–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00961-3

84. Xia Y, Tang W, Qian X, Li X, Cheng F, Wang K, et al. Efficacy and safety of camrelizumab plus apatinib during the perioperative period in resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A single-arm, open label, phase ii clinical trial. J Immunother Cancer. (2022) 10. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-004656

85. Xu J, Shen J, Gu S, Zhang Y, Wu L, Wu J, et al. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (RESCUE): A nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. (2021) 27:1003–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2571

86. Xu L, Chen J, Liu C, Song X, Zhang Y, Zhao H, et al. Efficacy and safety of tislelizumab plus lenvatinib as first-line treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 trial. BMC Med. (2024) 22:172. doi: 10.1186/s12916-024-03356-5

87. Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from imbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. Sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. (2022) 76:862–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030

88. Cheon J, Yoo C, Hong JY, Kim HS, Lee DW, Lee MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. (2022) 42:674–81. doi: 10.1111/liv.15102

89. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

90. Lee MS, Ryoo BY, Hsu CH, Numata K, Stein S, Verret W, et al. Atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (GO30140): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:808–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30156-X

91. Qin S, Chen M, Cheng AL, Kaseb AO, Kudo M, Lee HC, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus active surveillance in patients with resected or ablated high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave050): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2023) 402:1835–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01796-8

Keywords: hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, hepatocellular carcinoma, adverse events, combination therapy, safety management

Citation: Wu Y, Zeng Z, Chen S, Zhou D, Tong G and Du D (2025) Adverse events associated with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy and its combination therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Front. Immunol. 16:1531249. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1531249

Received: 20 November 2024; Accepted: 21 February 2025;

Published: 03 March 2025.

Edited by:

Ming Xu, Shimonoseki City University, JapanReviewed by:

Dainius Characiejus, Vilnius University, LithuaniaCopyright © 2025 Wu, Zeng, Chen, Zhou, Tong and Du. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Duanming Du, ZG1kdTY5QDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.