- 1Laboratory for Molecular and Cellular Therapy (LMCT), Translational Oncology Research Center (TORC), Department of Biomedical Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

- 2Laboratory for Molecular Imaging and Therapy (MITH), Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

- 3Department of Chemistry, University of Warwick, Warwick, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Thoracic Surgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 5Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel (UZ Brussel), Brussels, Belgium

- 6Department of Hematology, Team Hematology and Immunology (HEIM), Translational Oncology Research Center (TORC), Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel (UZ Brussel), Brussels, Belgium

- 7Department of Medical Oncology, Team Laboratory for Medical and Molecular Oncology (LMMO), Translational Oncology Research Center (TORC), Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel (UZ Brussel), Brussels, Belgium

Modest response rates to immunotherapy observed in advanced lung cancer patients underscore the need to identify reliable biomarkers and targets, enhancing both treatment decision-making and efficacy. Factors such as PD-L1 expression, tumor mutation burden, and a ‘hot’ tumor microenvironment with heightened effector T cell infiltration have consistently been associated with positive responses. In contrast, the predictive role of the abundantly present tumor-infiltrating myeloid cell (TIMs) fraction remains somewhat uncertain, partly explained by their towering variety in terms of ontogeny, phenotype, location, and function. Nevertheless, numerous preclinical and clinical studies established a clear link between lung cancer progression and alterations in intra- and extramedullary hematopoiesis, leading to emergency myelopoiesis at the expense of megakaryocyte/erythroid and lymphoid differentiation. These observations affirm that a continuous crosstalk between solid cancers such as lung cancer and the bone marrow niche (BMN) must take place. However, the BMN, encompassing hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, differentiated immune and stromal cells, remains inadequately explored in solid cancer patients. Subsequently, no clear consensus has been reached on the exact breadth of tumor installed hematopoiesis perturbing cues nor their predictive power for immunotherapy. As the current era of single-cell omics is reshaping our understanding of the hematopoietic process and the subcluster landscape of lung TIMs, we aim to present an updated overview of the hierarchical differentiation process of TIMs within the BMN of solid cancer bearing subjects. Our comprehensive overview underscores that lung cancer should be regarded as a systemic disease in which the cues governing the lung tumor-BMN crosstalk might bolster the definition of new biomarkers and druggable targets, potentially mitigating the high attrition rate of leading immunotherapies for NSCLC.

1 Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer related death, reflected by a staggering 1.79 million deaths in 2020 alone (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for ~85% of all cases and is further subdivided into adenocarcinoma (LUAD), squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma. The other 10-15% of lung cancers are represented by fast spreading small cell lung cancer, more slowly growing carcinoid tumors and rare types such as adenoid cystic carcinomas and sarcomas.

Though current lung cancer incidence mortality rates are highest in economically developed countries, they are gradually decreasing, mirroring declines in tobacco smoking next to therapeutic improvements for advanced-stage patients, including targeted and immunotherapies (1). At present, the main biological targets of immunotherapy are immune checkpoints, which aid cancer cells to deceive the patients’ immune system. Via delivery of immune checkpoint inhibitors, mostly monoclonal antibodies targeting the Programmed Death - (Ligand) 1 (PD-(L)1) or Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) pathways, antitumor immunity can be unleashed (2). Alas, immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) can coincide with serious immune-related adverse events, objective response rates remain <25% in unselected NSCLC patients and most responders eventually develop progressive disease. These sobering facts reflect the multitude of unaddressed resistance mechanisms to immunotherapy that remain today (3).

Histological expression of PD-L1 and tumor mutational burden (TMB) emerged as predictive biomarkers for response to ICB in NSCLC (4). Unfortunately, their predictive power is often unsatisfactory and doesn’t explain the nature of the resistance hubs that could aid oncologists during (combination) treatment decision making.

In search of additional biomarkers and targetable mechanisms of resistance to ICB, ample studies assigned a leading role to the tumor micro-environment (TME) (5, 6). Cytometry-based compositional analyses studies of the lung TME collectively demonstrated a predominance of T lymphocytes followed by B lymphocytes, neutrophils (Neu), and mononuclear phagocytes (7–11). Most bulk RNA sequencing studies of baseline NSCLC biopsies boil down to the observation that a ‘hot’ TME, characterized by activated effector T cells, interferon γ (IFNγ) signature and/or presence of an antigen presentation machinery, has strong predictive power for response to ICB. Noteworthy, most of these predictive gene signatures depart from a predefined lymphocyte-related gene set (12–15). As a result, most of these studies omit the relevance of the abundantly present Neu and mononuclear phagocytes for response and/or resistance to ICB.

By zooming in on the few studies that used a less or unbiased approach to establish an ICB predictive gene set (16–18), decisive roles for myeloid cell-related signatures have been demonstrated. When Hwang et al. tested the predictive value using a 395-gene panel, significant predictive power could be assigned to a T cell next to a M1 macrophage (Mac) characterizing signature (19). By using virtual microdissection of the bulk transcriptome of the TCGA LUAD cohort at single-cell resolution, Wu et al. defined two myeloid cell infiltration clusters, MSC1 and MSC2, significantly associated with a longer and shorter overall survival (OS) and response to ICB resp. In brief, the MSC2 signature was characterized by LAMP3+ dendritic cells (DCs), TIMP1+ Macs and S100A8+ Neu while the MSC1 profile showed higher levels of CD1c+ or CLEC9A+ DCs; IFITM2+, SELENOP+ or PPARg+ Macs and IFITM2+ Neu (20, 21). When Salcher et al. focused on the ICB predictive power of Neu subclusters within the NSCLC TME specifically, they defined a 38-gene encompassing tissue-resident Neu signature that was associated with anti-PD-L1 therapy failure in the randomized POPLAR and OAK clinical trials (22). Similarly, Peng et al. recently showed that NSCLC patients with a high TMB but low ‘Neu differentiation expression gene score’ were most likely to benefit from ICB (23).

Hence predictive signatures for ICB efficacy are likely to span more genes than the ones linked to activated lymphocytes and suggest that the lung tumor infiltrating myeloid cells (TIMs) deserve more attention for their biomarker potential to predict both response and resistance to ICB (9, 10, 21, 22, 24–28). Unlike lymphocytes, the proliferative and longevity potential of most myeloid cell subsets is low. This implies that TIM’s ampleness within the lung TME is the result of their continuous recruitment from their main cradle: the bone marrow niche (BMN). Nevertheless, the crosstalk between progressive solid cancers such as NSCLC and the distant BMN remains vastly understudied. This is attributable to the fact that in depth analysis of the BMN is hampered by the marrow’s inaccessible location, low fractions of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) (<1%) next to the heterogeneous and continuously differentiating character of hematopoiesis leading to its difficult nature to culture ex vivo. Thus, untapped biomarker and target potential might lie in the cues that govern tumor instituted alterations in hematopoiesis and TIM-propagating myelopoiesis in particular.

2 Recent insights in hematopoiesis

In adult life, the primary source of myeloid cells is the BMN, where the vital biological process known as hematopoiesis occurs. Hematopoiesis exhibits a continuous hierarchical differentiation process that is tightly regulated by lineage-determining transcription factors (TFs) of which many are highly conserved in mouse and human (29). During embryonal development, intra-aortic cells within the aorta-gonad-mesonephros generate the first multilineage hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). The latter represent a scarce population of self-renewing cells that translocate to the BMN to constitute most hematopoietic cells during adult life. In addition, HSC-independent hematopoiesis is also initiated during embryogenesis which partly persists in the adult hematopoietic system. HSC-independent lineages are either short-lived, such as primitive erythrocytes, or long-lived, such as tissue-resident Macs (30, 31). Myeloid cells represent a heterogeneous crowd of subsets with embryonic and/or hematopoietic origin (32–34). Fate mapping, transposon, Cre-loxP-mediated barcoding and single cell (sc) RNA-seq studies are continuing to refine our understanding of the compelling hematopoietic trajectories, of which we provide an updated overview below (35, 36).

2.1 LSK compartment: HSC and MPPs

The murine Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) or human CD34+ compartment represents the HSCs, including the multipotent progenitors (MPPs). They lodge at the top of the hierarchical ladder and withhold high self-renewing but low proliferative capacity (37). For years, HSCs were subdivided in long-term (LT-HSCs) and short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs) according to their reconstituting potential (38). Yet recent scRNA-seq-based characterization of the LSK compartment with functional reconstitution assays, redistributed this compartment into HSCs and six different types of MPPs (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1). Within the latter, erythroid-primed MPP2, myeloid-primed MPP3, and lympho-erythromyeloid-primed MPP4 have been defined (39, 40). Sommerkamp et al. further report on a close relationship between MPP1 and MPP5 placing them downstream of HSCs but upstream of the less potent MPP2/3/4, while MPP6 resides in a cloud with MPP5, be it with higher multilineage potential than the latter. Further, MPP5 seems to act as a reservoir during emergency myelopoiesis (37). These findings suggest that a functional hierarchy, consisting of progenitors at varying degrees of lineage priming is already installed within the multipotent HSC/MPP fraction. Multi- and oligopotency characterizing TFs are Hlf and ESAM which are downregulated upon specification and commitment resulting in progressive loss of alternative fates along all lineages (35, 39). Additionally, the stem/progenitor state is stabilized by the regulation of the Gata2, Tal1/Scl and Fli1 triad (41).

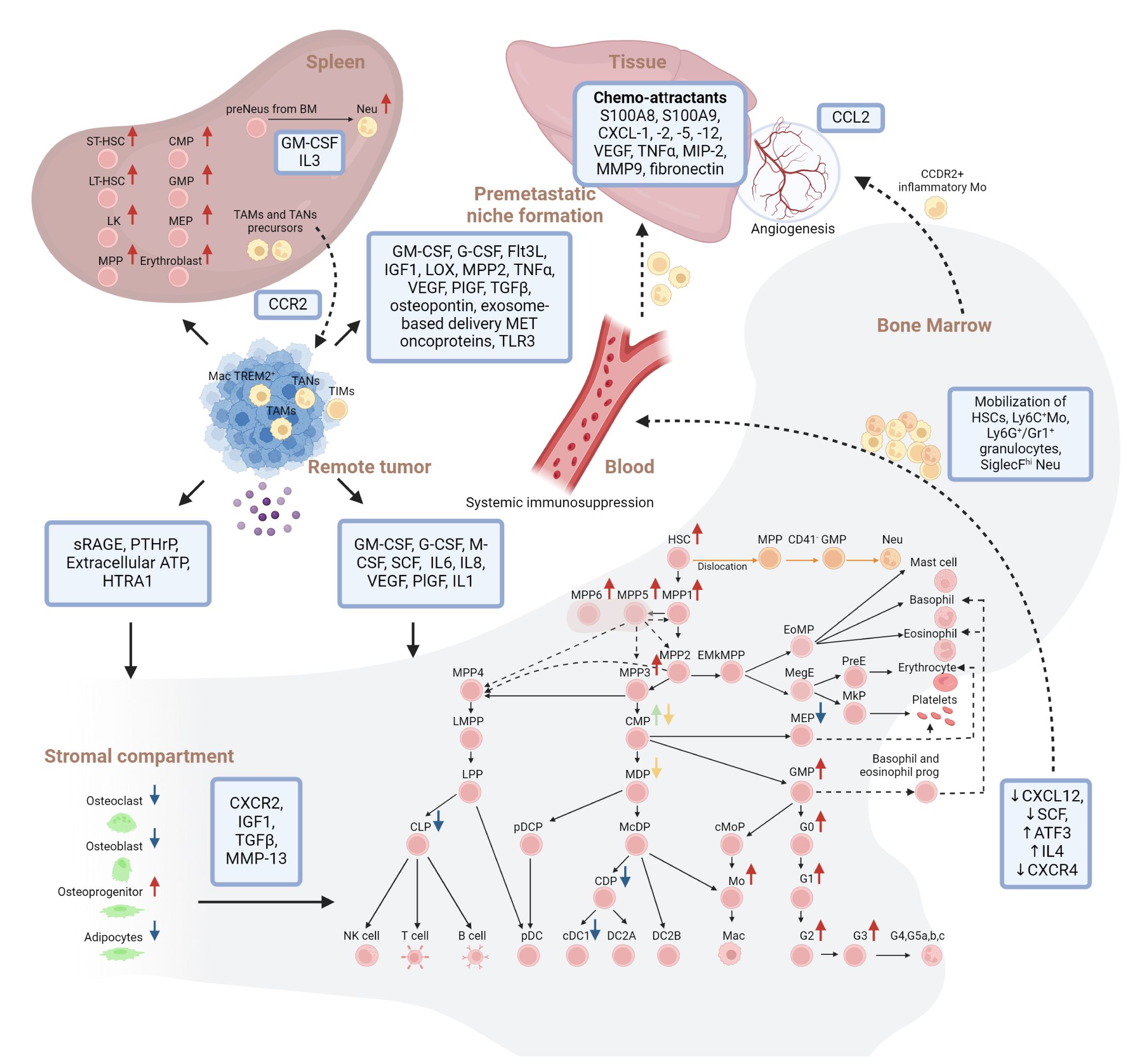

Figure 1 Overview of solid tumor installed cellular and molecular hematopoietic perturbations in human and mouse models. Hierarchical model of continuous hematopoiesis in mouse is shown. Interactions between remote tumor, Bone marrow, stromal compartment, spleen and premetastatic niche formation are indicated. Red arrows indicate increase, blue arrows indicate decrease, green and yellow arrows indicate lack of consensus on changes in the abundance of the respective populations within the bone marrow niche during solid cancer progression. Dashed lines indicate mobilization of cells. Orange lines indicate the alternative trajectory of neutrophils due to the bone marrow-tumor crosstalk. LK, Lin-Sca-1-c-Kit+; HSC, Hematopoietic Stem Cell; MPP 1/2/3/4/5/6, MultiPotent Progenitor 1/2/3/4/5/6; LMPP, Lymphoid-primed MultiPotent Progenitor; EMkMPP, Erythroid-Megakaryocyte-primed MultiPotent Progenitor; EoMP, Eosinophil-basophil-Mast cell Progenitor; MegE, pre-Megakaryocyte-Erythroid progenitor; PreE, Pre-colony-forming-Erythroid progenitor; MkP, Megakaryocyte Progenitor; CMP, Common Myeloid Progenitor; MEP, Megakaryocyte/Erythrocyte Progenitor; LPP, Lymphoid-Primed Progenitor; MDP, Monocyte/Dendritic cell Progenitor; GMP, Granulocyte/Monocyte Progenitor; GP, Granulocyte Progenitor; CLP, Common Lymphoid Progenitor; NK cell, Natural Killer cell; pDCP, plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Progenitor; McDP, Monocyte/conventional Dendritic cell Progenitor; cMoP, common Monocyte Progenitor; Mo, monocytes; CDP, Common Dendritic cell Progenitor; (c)DC1/2A/2B, (conventional) Dendritic Cell 1/2A/2B; pDC, plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell; G0, granulocyte progenitor; G1/G2/G3, pre/pro/immature neutrophils; G4,G5a,b,c, mature neutrophils; (pre)Neu, (pre)neutrophils; Mac, macrophage; (ST)/(LT)-HSC, Short-term/long-term- HSC; TA(M)/(N), Tumor associated Mac/Neu; TIM, Tumor infiltrated myeloid cells; sRAGE, soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; SCF, stem cell factor; IL1/4/6/8: Interleukin 1/4/6/8; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; PIGF, placental growth factor; ATF3, activating transcription factor 3; CXCR2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 2; IGF1, insulin-like growth factor 1; TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta; HTRA1, HtrA serine peptidase 1; LOX, hypoxia-installed lysyl oxidase. Created with BioRender.com.

2.2 Committed-lineage progenitors

Downstream of the multipotent HSCs and MPPs, the original lineage bifurcation model strictly separated oligopotent Common Lymphoid Progenitors (CLP) from Common Myeloid Progenitors (CMP) which could further diverge into Megakaryocyte/Erythrocyte Progenitors (MEPs), Monocyte (Mo)/Dendritic cell (DC) Progenitors (MDPs) and Granulocyte/Mo Progenitors (GMPs). However, this model has been the subject of ongoing revision in the scRNA-seq era. On the one hand, a Lymphoid-primed MultiPotent Progenitor (LMPP) with combined lymphoid and myeloid potential has been shown to gradually lose myeloid potential by upregulating the interleukin-7 receptor α-chain (IL7Rα) and differentiate into Dach1- Lymphoid-Primed Progenitors (LPPs) prior to CLPs (29, 33, 35, 42–45). On the other hand, erythroid-versus-myeloid fate decisions seem to be made prior to CMP commitment (36, 40, 46), calling for in-depth revision of all CMP progeny (MEPs, MDPs and GMPs) as well (46). While the Flt3L+CD115lo CMPs give rise to oligopotent MDPs, the Flt3-CD115- CMPs give rise to GMPs. The former are defined by TF co-expression of CEBPA, IRF8 and RUNX1 (44). MDPs can give rise to IRF8/SATB1 plasmacytoid DC (pDC) Progenitors (pDCPs) and HLA-DR/IRF8/CEBPA Mo/conventional DC (cDC) Progenitors (McDPs). The latter bifurcate in CD11c/CD172ab/CD14 (human) or Ly6C+ Mo (mouse) or IRF8/HLA-DR/CD84/CD172ab Common DC Progenitors (CDPs) (44). In contrast, GMPs (Kit, CD34, Sox4) are very heterogeneous at the transcriptomic and proteomic level and can adjust their functional output towards common Mo Progenitors (cMoP) and Granulocyte Progenitors (GPs) (32).

2.3 DC trajectory

In general, DC progenitors rely on Flt3 and Flt3L for their differentiation and proliferation into pDCs, cDC1 and cDC2. In addition, cDC1 and cDC2 differentiation depends on the specific TF expression of IRF8, BATF3 and ZFP366 versus IRF4 and KLF4 resp. While XCR1/Clec9A/CADM1 cDC1s seem to originate solely from CDPs, recent paradigm shifts are sharpening the ontogeny of cDC2s and pDCs. In case of cDC2s, murine T-bet+ DC2A and RORγt+ DC2B have been described which align with human CD5+ DC2s and CD14+ DC3s (47). Recently, Liu et al. further demonstrated these DC subsets have a different ontogeny. Whereas ESAM+ DC2s are derived from CDPs, the CD172a+ CD16/32+ DC3 fraction seems to develop directly from Ly6Chi McDPs (48). Further, CD123+ pDCs can be derived from MDPs, yet they predominantly originate from IL7Rα+ LPPs requiring high expression of IRF8 and TCF4 for pDC development and identity resp. Although MDP and LPP derived pDC subsets can secrete IFN type 1, only the former share with cDCs the ability to process and present antigens (49).

2.4 Monocyte differentiation

Both in mice and human, Mos are subdivided in IRF8-dependent Ly6Chi or CD14+CD16- classical and IRF8/Nur77-dependent Ly6C- or CD14loCD16+ non-classical Ly6C- Mo resp. Also, they can emerge from at least two different lineage tracks defined by the complementary oligopotent GMPs and MDPs (32, 34). Interestingly, GMPs produce “Neu-like” Ly6Chi Mo while MDP-derived Mo show similarities in gene expression with Macs and DCs. Both GMP- and MDP-derived Mo yield Macs but only the MDP pathway gives rise to MoDCs (32, 34). In general, Mos development largely depends on the expression of Csf1r (CD115) (48, 50) to result in the expression of Mo characterizing markers such as Fcer1g, F13a1, Irf8, Klf4, Zeb2 and Irf5 (35, 51). Relative to other myeloid cells, Mos have an exceedingly short transit time through the BMN and are rapidly released into the circulation after their last division, governed by CCR2 and CX3CR1, where the latter receptor prompts survival of Ly6Clo Mo. In contrast, CXCR4-signaling represents an anchoring force that retains Ly6Chi Mos in the BMN, identifying them as transitional pre-Mos that replenish the mature Mo pool for peripheral responses (35, 51). Notably, Mos also contribute to the replenishment of yolk sac-derived tissue-residing Macs in tissue and gender dependent fashion (32).

2.5 Granulopoiesis

The neutrophil differentiation trajectory is defined by at least 5 stages (G0-G5) where the earliest GPs (G0), embedded in the GMPs, initiate granulopoiesis through Runx1, Cebpa, Gstm1, Per3 and Ets1 expression (35, 52–55). Subsequent differentiation into proNeu (G1), results in full granulocyte commitment and maturation via TF ThPOK (35, 52–55). This is followed by a transcriptional shift to Gfi1 and Cebpe in the preNeu (G2) which represses Mos on MDP fate (Irf8, Klf4 and Zeb2). The latter are still proliferative in the BMN and spleen but hardly found in blood due to their poor motility. Further silencing of Gata1 and Gata2 results in non-proliferating immature Neu (G3). Finally, PU.1, Cebpd, Runx1, and Klf6 upregulation drives the generation of mature Neu (G4 mainly in BMN and G5a, b and c mainly in blood) which substitute their proliferative capacity for trafficking and effector functions. In line, they are characterized by Neu lineage characteristic expression of Elastase (Elane) and ficollin (Fcnb) (53). Notably, the temporal expression of the Cebp-family members mirrors the pattern of granule enzyme expression; primary (e.g. Mpo), secondary (e.g. Ltf) and tertiary granules (e.g. Mmp8) are expressed at the G0-G1, G2-G3 and G4-G5 stage, corresponding to Cebpa, Cebpe, and Cebpd expression resp. After maturation, Neus are retained in the BMN through CXCR4 while CXCR2 drives their release into the circulation (56). During inflammation, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) further potentiates their mobilization.

Recent scRNA-seq studies on murine and human myeloid progenitors suggest that eosinophils, basophils (characterized by high expression of TFs Gfi1, Il5ra, Prg2, Epx or Lmo4, Runx1 resp.) and mast-cells, bifurcate directly from MPPs instead of GMPs. Specifically, Gata1 expression has been shown to establish an early branch point to separate lineage-commitment. Whereas Gata1- progenitors commit to the LMPPs and GMPs to hatch lymphocytes and Neu/Mo-restricted lineages resp., Gata1+ progenitors give rise to co-segregated commitment of Eosinophil/basophil/Mast cell Progenitors (EoMP) and a Megakaryocyte/Erythroid lineage (MegE) (57–59). The inflection point at erythroid and megakaryocyte lineage bifurcation is characterized by downregulation of RUNX1, GATA2 and PBX1 (44).

2.6 Stromal involvement in hematopoietic regulation

In the highly specialized BMN, HSCs team up with stromal cells of mesenchymal, endothelial and neuronal origin (60–64). To safeguard the balance between HSC maintenance and output, extrinsic and intrinsic factors are continuously engaged. Extrinsic factors include hypoxia, growth factors (GFs), direct cell-cell contacts, and signaling pathway activating morphogens, next to intrinsic factors encompassing TFs, cell cycle regulators, epigenetic proteins, and miRNAs, as extensively reviewed elsewhere (65). The curated orchestration of hematopoiesis is further reflected in the establishment of bidirectional interactions between HSCs and a variety of endothelial cells and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in spatially restricted microanatomical niches (64, 66).

The type of blood vessels has been used to subdivide the BMN into a central sinusoidal niche, an arteriolar niche and a peripheral endosteal niche with transition zone vessels. While the former comprises highly permeable vessels to promote HSC proliferation, activation and leukocyte trafficking, the latter two support HSC regeneration and maintenance by keeping them in a quiescent state through reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) availability (67–69). In addition, the endosteum harbors bone-modulating osteoblasts and osteoclasts, shown to support HSC maintenance and retention amongst others mediated through production of G-CSF, stromal-cell-derived factor 1 (CXCL12 or SDF-1), stem cell factor (SCF) and Notch ligand jagged 1 (JAG1) (70–73).

The vast majority of HSCs reside in the central sinusoidal niche in direct contact with sinusoidal endothelial cells and perivascular mesenchymal progenitors including adipogenic leptin receptor+ CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells (69, 74–80). Via their paracrine secretion of CXCL12 and SCF, the CXCR4 and c-Kit receptor on HSCs are respectively triggered, cardinal for hematopoietic multilineage differentiation (76, 81, 82). Baccin et al. additionally allocated an osterix+ osteogenic CAR population to the vicinity of arterioles and non-vascular regions and concluded that the adipogenic- and osteogenic CAR cell populations represent the main producers of key cytokines and GFs (such as CXCL12), suggesting their localization within the sinusoidal and arteriolar niches resp. establishes unique hubs of HSC differentiation and maintenance (61). In addition, Li et al. recently defined 3 stromal niche populations with distinct HSC regulatory impact (64). In addition, they predicted that bidirectional communication enables HSCs and derivates to regulate stromal cells as well. Hence, homeostasis reinstating feedback mechanisms can be activated such as adipogenic CAR cell activation through IL1 secretion of activated platelets (83).

Overall, technological advances are currently sharpening our understanding of the intricate hematopoietic process. Nevertheless, we cannot speak of a complete fathoming of all hematopoietic tributaries yet, calling for continued research of the BMN in healthy and diseased subjects.

3 Recent advances in singe cell omics reveal a complex lung TIM crowd

scRNA-seq analysis represents a very powerful tool that recently barged into the onco-immunology field. Through this approach, unbiased and in-depth insights have emerged that foster an unprecedented understanding of biological phenomena on transcriptional single cell level. Especially compared to flow cytometry- and microscopy-based approaches which rely on antibodies to pre-defined markers. In recent years, scRNA-seq of NSCLC biopsies markedly deepened our understanding of the TME in which especially the TIM compartment appeared to hold an underestimated myriad of subsets with distinct progenitors and functions (21–23, 25–27, 84–89). Moreover, TIMs have garnered increasing attention for their potential as biomarkers to predict both response and resistance to ICB. Yet each scRNA-seq study used different tumor samples and sequencing techniques. As a result, a plethora of TIM subsets have been described, yet to our knowledge, no side-by-side overview of the most recent scRNA-seq studies has been generated to define the subsets, perpetuated by most of these studies.

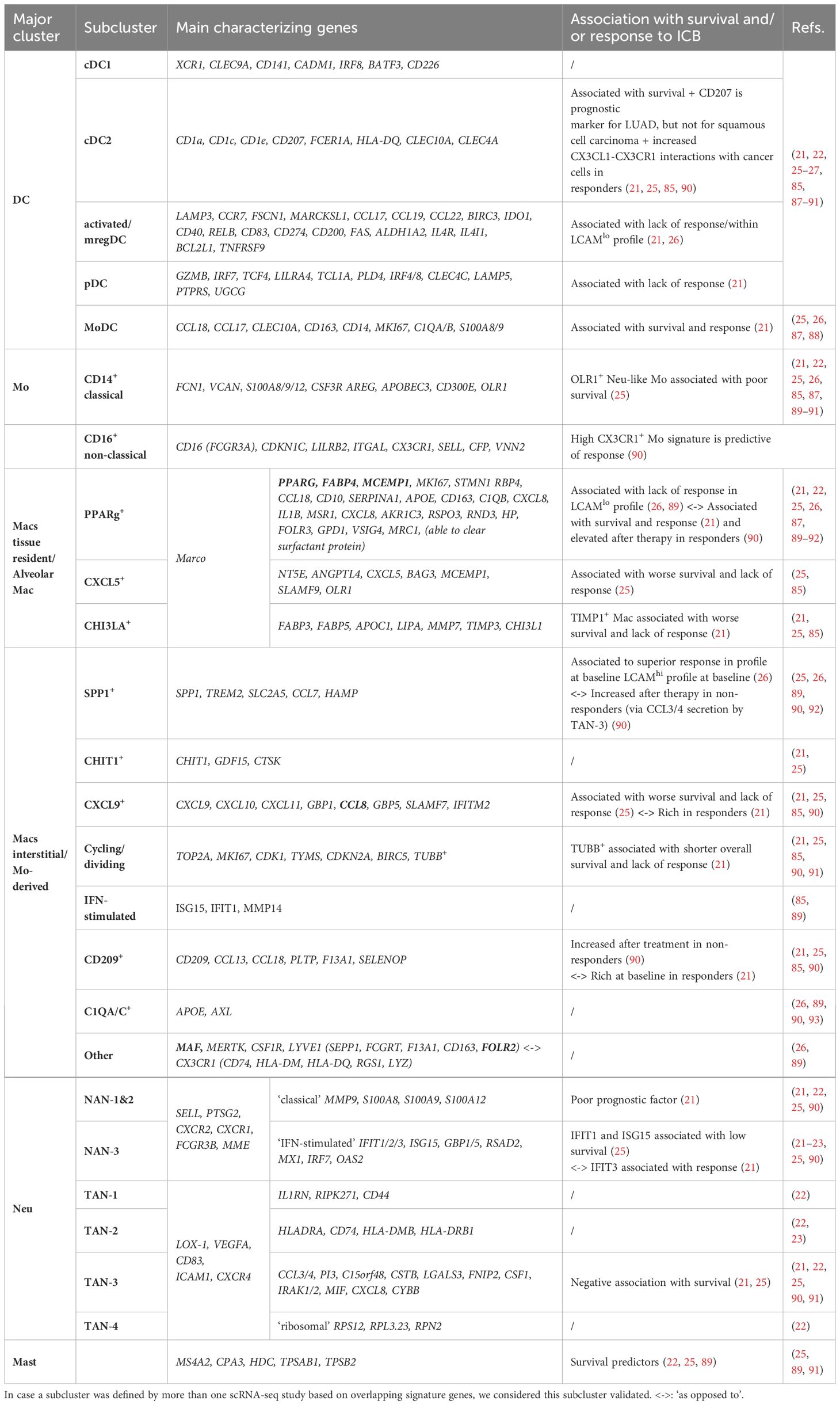

So far, consensus has been reached on at least 5 main ontogenetically discernable human lung TIM populations: DCs, Mos, Macs, Neus and mast cells (Table 1). For lung TME-associated DCs, 5 subclusters have consistently been defined: cDC1 and cDC2, mature regulatory DCs (mregDCs, derived from cDC1 and cDC2), pDCs and Mo-derived DCs (Mo-DCs). Lung tumor-associated Mos are repeatedly reported to be of classical or patrolling non-classical origin. In the case of Macs and Neus, much less consensus has been reached across different scRNA-seq studies. We found that for at least 11 Mac and 6 Neu subclusters, two or more independent scRNA-seq studies reported on their presence. The Mac subclusters comprise 3 tissue resident and 8 Mo-derived fractions, while Neus are represented by 2 normal adjacent tissue-associated Neu (NAN) and 4 tumor-associated Neu (TAN) fractions.

Table 1 Overview of major lung TIM clusters with respective subclusters defined by scRNA-seq and their respective reported association with response to ICB.

In terms of TIM subcluster specific prognostic and predictive biomarker potential, unanimity also remains scarce. If we only consider the correlations that were validated by more than one scRNA-seq-based study, consensus has been reached for the positive and negative association of cDC2 and mregDCs resp. with response to ICB. In addition, mast cells and TAN-3 have been associated with a better and worse OS, irrespective of the treatment type. Singular studies further ascribe a positive ICB predictive or prognostic role to MoDCs and CX3CR1hi Mo. In contrast, a negative correlation with response to ICB has been reported for pDCs, dividing TUBB+ Macs, CXCL5+ Macs and CHI3LA+ Macs while the presence of NAN 1&2, OLR1+ Mo, CXCL5+ Macs, dividing TUBB+ Macs, TIMP1+ Macs and CXCL9+ Macs has been associated with worse OS. However, subcluster specific discrepancies have been reported as well. For example, Leader et al. defined the Lung Cancer Activation Module (LCAM) to predict response to anti-PD-(L)1 therapy using scRNA-seq data from lung tumor biopsies at baseline (12). While NSCLC patients with high TMB, mutated TP53, and LCAMhi profile with SPP1+ Macs (next to PD1+ CXCL13+ T cells, IgG+ plasma cells) showed superior responses, the opposite held true for patients with low TMB, TP53 wild type and LCAMlo profile characterized by mregDCs and PPARg+ Macs (next to naïve and central memory T cells and reduced plasma/B cell ratios). Akin, Wu et al. found that LAMP3+ DCs were the only subtype enriched in non-responders, which seems partly in line with the resting mregDC-rich LCAMlo profile. In contrast, both Wu et al. and Hu et al. associated the enrichment of PPARg+ Macs (next to NAN-3) with a major pathological response to ICB, while Hu et al. further defined a negative correlation between SPP1+ Macs (next to TAN-3) and ICB response. Importantly, Hu et al. analyzed samples after neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 ICB with chemotherapy instead of baseline biopsies (21, 90).

The high variability in subcluster definitions and denoted biomarker potential of lung TIMs can be partly explained by the disparity of the scRNA-seq studies. First, the use of different scRNA-seq platforms has been shown to hamper proper data alignment (22). Second, scRNA-seq studies encompass tumor biopsies from patients with diverse profiles (early versus late stage, histological and genetic subtype) and sampling procedures (intra- versus peritumoral, derived from primary versus metastatic lesion, pre- or posttreatment) (22, 23, 85, 89). Considering that TIM subcluster phenotypes and functions are eminently impressionable by local traits in time and space, evaluation, and comparison of TIM subclusters between different tumor biopsies might be a clinical challenge. To illustrate, both tumor-associated cDC1 and cDC2 have been reported to execute antitumor immune promoting and suppressing activity (88, 94). Within the diversified family of tumor-associated Macs and Neus, this ambiguity seems even more pronounced with assigned functions ranging from pro-angiogenic, pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive to antigen presenting, CD8+ T cell stimulating and tumor eradicating (95, 96).

In conclusion, scRNA-seq delivered an overwhelming amount of new info regarding lung TIM subclusters. However, as the exact TIM clustering method is subject to tumor sample and experimental heterogeneity, their denoted identity and biomarker potential should always be interpreted with caution. Instead of using a snapshot of the TIM composition to predict response to therapy, the question arises whether it is not more interesting to systemically monitor which tumor-derived myelopoiesis perturbing cues are responsible for the influx of TIMs so these can serve as a means of biomarkers and potential targets simultaneously. To illustrate, macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF or CSF-1) is known to be secreted by tumors to alter remote myelopoiesis. While levels of plasma CSF-1 have been associated with resistance to ICB in NSCLC patients (97), blockade of its receptor CSF1R is currently being investigated to treat advanced malignancies (98).

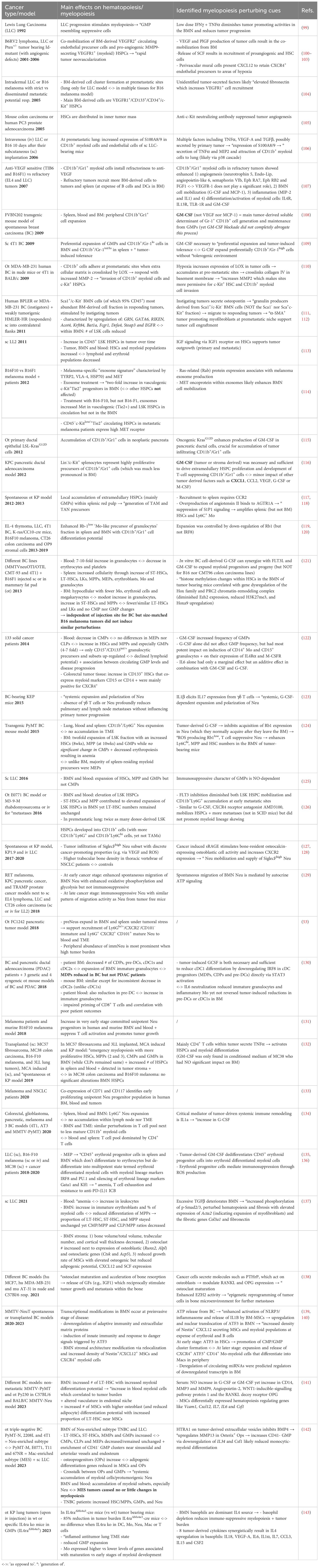

4 Crosstalk between solid cancer and the BMN

The lifespan of the majority of myeloid cell subsets is relatively short. Consequently, the abundance of TIMs within the TME reflects their ongoing recruitment from their primary reservoir: the BMN. Although the communication between solid cancers and the distant BMN remains largely unexplored, the wealth of preclinical and clinical investigations underscore that the progression of solid cancers is a systemic phenomenon, utilizing both intra- and extra-medullary hematopoiesis. Ample preclinical and clinical studies convey that solid cancer progression is a systemic process by exploiting intra- and extra-medullary hematopoiesis. After listing all studies that evaluated solid cancer-related hematopoietic alterations (Table 2), it becomes apparent that the latter are most often characterized by emergency myelopoiesis, commonly at the expense of megakaryocyte/erythroid and lymphoid differentiation (111–115, 121, 122, 124–126, 132, 134–137, 139, 140, 144).

Table 2 Overview of preclinical and clinical studies which investigated the type and location of hematopoiesis and myelopoiesis perturbing cues in tumor bearing subjects.

4.1 Emergency myelopoiesis

Paracrine signals from the tumor most often instigate emergency myelopoiesis, entailing activation, expansion and/or mobilization of HSPCs and immunosuppressive myeloid progenitors. In brief, most studies report on a drastic elevation of cells in the LSK compartment (HSCs and MPPs, mainly MPP3), GMPs and early stage committed Neu progenitors in the BMN (Figure 1), blood and even in the TME (53, 99, 109, 113, 119, 121, 122, 124–126, 129, 131–134, 141, 142, 145). Although immunosuppressive Ly6C+ Mo and Ly6G/Gr1+ granulocytic myeloid cells, a.k.a. mo- and g-myeloid-derived suppressor cells resp., have been shown to dominate peripheral blood and tumors (126, 146),, trends for BMN-residing CMPs are less clearly defined than for GMPs. For example, Wu et al. describes a marked decrease of CMPs in blood of 133 solid cancer patients (in contrast to significant increase in HSCs, MPPs and GMPs) (122). Akin, higher frequencies of GMPs but not CMPs have been reported in murine breast and lung cancer models (124, 125, 137, 142). In contrast, Al Sayed et al. showed in fibrosarcoma and different lung models that next to HSCs, MPPs and GMPs also CMPs increased due to their higher proliferative capacity within the BMN (132). In addition, Meyer et al. observed that the increase in immature granulocytes was at the expense of CDPs, pre-DCs and especially cDC1s (130).

4.2 Secreted myelopoiesis perturbing cues

Cancer-forced emergency myelopoiesis is orchestrated by tumor secreted myeloid-lineage-specific GFs and cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), G-CSF, M-CSF, SCF, IL6, IL8, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Placental growth factor (PlGF) and IL1 (100, 101, 108, 109, 115, 116, 121, 122, 147). GM-CSF is by far the most documented tumor-derived hematopoietic perturbator with reported role in amongst others, the expansion of GMPs and immunosuppressive Ly6C+ Mo and Ly6G+/Gr1+ granulocytes in BM, blood and spleen. Moreover, it has been linked to the de-differentiation of erythroid progenitors to multipotent immunosuppressive myeloid progenitors leading to anemia. Notably, anemia is shown to be strongly associated with poor prognosis in most cancer types as well as a compelling risk factor that can obstruct ICB therapy efficacy (122, 124, 135–137). Less consensus has been reached on the role of G-CSF with reports ranging from ‘essential for suppressive Neu expansion and polarization’ at the expense of cDC1 generation (123, 124, 130) over ‘minor impact on HSPC and GMP proliferation and/or immunosuppressive myeloid cell skewing’ (109, 116, 122, 126). Notably several studies reported on the lack of hematopoietic perturbation similarity between different tumor models (121, 130, 142), calling for careful interpretation of studies using different mouse models in terms of tumor type, stage, site and mode of engraftment.

4.3 Stromal involvement in hematopoietic regulation during cancer

Interestingly, recent studies on how tumor secreted factors are molding hematopoiesis exactly, are revealing a key role for BMN-residing stromal and differentiated immune cells. Akin, cancer-related bone loss as a result of deteriorated osteoclast and osteoblast numbers and activity has been reported (127, 128, 137, 138). It seems that this mainly involves the direct crosstalk between tumor cells and MSCs, which are skewed towards osteoprogenitors at the expense of adipogenic differentiation (141, 142). Mechanistically, spontaneous orthotopic lung cancer models have been shown to secrete a soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) which can provoke osteocalcin+ osteoblast activity with enhanced CXCR2 expression and subsequent mobilization of tumor-infiltrating SiglecFhi Neu (127, 128). Zhang et al. further describe the involvement of tumor-derived parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) which bolsters osteoblast maturation by modulating the expression of RANKL and its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin (OPG) (138). Osteoclast activity can subsequently release niche and hematopoiesis perturbing factors such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and TGFβ (137, 138). In addition, breast cancer-derived ATP has been shown to activate the NLRP3/inflammasome and release IL1β by BMN-residing Nestin1+ CXCL12 secreting MSCs which results in decreased CXCL12 and SCF expression to increase HSC mobilization, ATF3 promoting CMP/GMP cluster formation and expansion of CD14+ Mo that differentiate to tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (139, 140). Finally, HtrA serine peptidase 1 (HTRA1) on tumor-derived vesicles has been reported to upregulate MMP13 in osteoprogenitors which subsequently induce CD41- GMP clustering and systemic accumulation of protumoral Neu (142).

Aside from stromal cells, also BMN-residing basophils were recently shown to fuel emergency myelopoiesis via their production of IL4 during orthotopic lung tumor progression, resulting in GMP expansion and subsequent increase in the number of lung TIMs such as TREM2+ Macs (143). From these relatively disparate findings, it appears that further research is needed to ascertain the exact tumor-specific direct and indirect crosstalk with the different members of the BMN to install tumor promoting emergency hematopoiesis.

4.4 Extra-medullary alterations in hematopoiesis

Next to intra- also extra-medullary alterations in hematopoiesis have been reported (108, 119, 120, 124, 132, 134–136). Bayne et al. used the pancreatic adenocarcinoma model KPC to show that Lin-/c-Kit+ HSCs within the spleen were highly proliferative precursors of Neu and that this phenomenon was much less pronounced in the BMN (116). In line, Sio et al. report on increased splenic but not BMN cellularity with increase in ST-HSCs, LT-HSCs, LKs (Lin-Sca-1-c-Kit+), MPPs, CMPs, GMPs, MEPs and erythroblasts. In contrast, the BMN only revealed an increase in ST-HSCs, MPPs and GMPs whereas the number of LT-HSCs, LKs, MEPs and CMPs decreased (121). In contrast, Casbon et al. found in the PyMT transgenic breast carcinoma (BC) model that the BMN was the main site of Ly6G+ cell generation, in accordance with increased frequencies of marrow but not splenic HSCs, MPPs and GMPs (124). Unlike BM, the majority (80–90%) of spleen-residing myeloid progenitors were MEPs, which is in line with later studies on the generation of erythroid differentiated myeloid cells in tumor bearing subjects (135, 136). As such the splenic red pulp acts as an extra reservoir of immunosuppressive TAM and TAN precursors (recruitment to tumor via CCR2) that promote solid tumor progression and metastasis (117). Mechanistically, overproduction of the peptide hormone angiotensin II in tumor bearing mice triggers S1P1 signaling in HSCs and as such amplifies splenic but not BM-derived HSCs which acts upstream of a potent Mac amplification program (118). These findings indicate HSPC mobilization from the BMN to the spleen as well as extramedullary HSPC proliferation (107, 116). For emergency granulopoiesis specifically, preNeus have not been found in blood, ruling out their mobilization from the BMN to spleen making their splenic expansion likely attributable to the production of GM-CSF and IL3 in the spleen microenvironment (53, 148).

4.5 Premetastatic niche formation

In addition, systemic tumor-HSPC crosstalk represents a cornerstone for tissue specific premetastatic niche formation. On the one hand systemic release of tumor-derived factors can downregulate CXCR4 resulting in the proliferation and mobilization of HSPCs like VEGFR1+ HSPCs, myeloid cell skewed LSKs and α-SMA+ cancer-associated fibroblasts activating Sca-1+c-Kit- cells to the premetastatic niche (104, 111–113). Primary tumor-derived factors reported to be involved in these processes are GM-CSF, G-CSF, Flt3L, IGF1, hypoxia-installed lysyl oxidase (LOX), MMP2, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), VEGF, PlGF, TGFβ and osteopontin (5, 100–103, 106, 110–113, 121, 126, 132, 137, 138) as well as exosome-based delivery of MET oncoproteins and TLR3 triggering small nuclear RNAs (114, 149). These factors support recruitment of HSPCs next to Ly6G+ Neu and Ly6C Mo myeloid cell skewing at the premetastatic niche which further involves the expression of chemo-attractants like S100A8 and S100A9, CXCL-1, -2, -5 and -12 next to VEGF, TNFα, MIP-2, MMP9, fibronectin, largely dictated by the cellular composition of the TME (25, 106, 149, 150). On the other hand, the BMN is also actively involved in the provision of angiogenic cells such as BM-derived VEGFR2+ endothelial progenitor cells and vasculogenic c-Kit+Tie2+ progenitor cells that contribute to neovascularization of premetastatic sites (101, 151). As such, solid cancer - BMN crosstalk not only impacts hematopoiesis but also tumor vascularization and even angiogenesis as CCL2 gradients recruit CCR2+ inflammatory Mos, which produces VEGF to increase vascular permeability (107, 128). This is further strengthened by the observation that anti-c-Kit neutralizing antibody treatment suppressed tumor angiogenesis in a murine colon and human prostate model (105).

Overall, the distant solid tumor – BMN crosstalk can result in a plethora of hematopoiesis perturbing cues which ultimately result in the lamentable characteristics of tumor progression ranging from metastasis over bone loss and anemia. Although this crosstalk may thus be the ideal target to nip the progression of solid tumors in the bud, the exact signals, and cellular actors of this crosstalk are just begun to be uncovered. Our overview further shows that so far both similar and different observations have been made, based on the experimental setup and tumor type, ratifying a great deal of research remains to be done.

5 Clinical targeting of myelopoiesis perturbing cues

From the extensive list of identified solid cancer installed myelopoiesis perturbing cues (Table 2), only a handful have so far been clinically targeted in NSCLC patients. These include IL6 with Tocilizumab (152–154); CCL2 with Carlumab (155), IL1β with Canakinumab (156–162), VEGF-A with Bevacizumab (163) or Ramucirumab (anti-VEGFR2 (164)), CSF1R with Cabiralizumab (165) or Pexidartinib/PLX3397 (166), IGF1R with Figitumumab (167) and IL4 with Dupilumab (168). While Bevacizumab and Ramucirumab are FDA approved to treat advanced NSCLC in combination with chemo or targeted therapy based on their significant improvement in progression free survival and OS [161, 162], all other agents are still under clinical evaluation. This as monotherapy (Carlumab and Canakinumab) or in combination with chemotherapy (Canakinumab and Figitumumab) or ICB (Tocilizumab, Canakinumab, Cabiralizumab, Pexidaetinib and Dupilumab). As these are mainly represented by phase I/II clinical trials probing drug safety and tolerability, efficacy data are scarce (152–154, 156, 157, 159, 162, 165, 167). However, in case of anti-IL1β therapy with Canakinumab, at least three trials demonstrated a lack of efficacy when delivered as mono- or in combination with chemotherapy (158, 160, 161). Similarly, the phase I/IIa clinical trial in which the safety and ORR were evaluated in solid cancer patients upon combined CSF1R inhibitor Pexidaetinib with anti-PD-1 Pembrolizumab, was terminated prematurely due to lack insufficient evidence of clinical efficacy (166). Concerning Carlumab (anti-CCL2), although preliminary antitumor activity was demonstrated in different solid cancers, including NSCLC (155), it failed to prove clinical benefit in a phase II study in metastatic prostate cancer (169). Interestingly, IL-4Rα blocking antibody dupilumab given in conjunction with PD-(L)1 ICB in NSCLC patients who had progressed on ICB alone reduced circulating Mo, expanded tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, and in one out of six patients, drove a near-complete clinical response two months after treatment, advocating for its further clinical evaluation (143).

6 Conclusion and future perspectives

TIMs within the TME stand as prominent culprits in fostering resistance against ICB, while the BMN serves as the principal nurturing ground for myeloid cells throughout adulthood. Based on recent and, whenever possible, scRNA-seq data, we provide a comprehensive overview of solid cancer-mediated hematopoietic alterations with particular focus on myelopoiesis in the BMN of NSCLC patients. Overall numerous hematopoiesis perturbing cues have been identified that boil down to emergency myelopoiesis following rise in TIMs, at the expense of megakaryocyte/erythroid and lymphoid differentiation. Despite the wealth of novel information provided by cutting edge technologies such as scRNA-seq, this has led to an ongoing evolution in our understanding of hematopoiesis and the identification of lung TIM subcluster, often hampering consensus in terms of their predictive value for OS to ICB. Recent studies also reveal a previously undescribed role for the MSCs in the BMN, advocating for more research into the latter instead of blood- and tumor-derived HSPCs and immune cells. Overall, these findings emphasize that NSCLC should be considered as a systemic disease, underscoring the need for further investment in biomarker monitoring by integration of innovative technologies and models that extend beyond snapshots of the primary disease site. Additionally, we believe hematopoietic perturbing cues hold untapped target potential to improve the current sobering response rates to immunotherapy for advanced NSCLC patients.

Author contributions

EC-E: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. KR: Writing – original draft, Investigation. TB: Writing – original draft, Investigation. YJ: Writing – review & editing. DV: Writing – review & editing. RH: Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – review & editing. IR: Writing – review & editing. LD: Writing – review & editing. CG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. EC-E was supported by Eutopia PhD co-tutelle fellowship and Wetenschappelijk Fonds Willy Gepts of the UZ Brussel, KR was supported by Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO, G041721N) and Kom op tegen Kanker Emmanuel van der Schueren, TB was supported by an ORC Cancer Research fellowship and Kom op tegen Kanker Emmanuel van der Schueren, RH was supported by the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO, 1SE9324N) and CG was supported by FWO, Eutopia and Wetenschappelijk Fonds Willy Gepts of the UZ Brussel.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1397469/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Surface markers of murine hematopoietic cell subsets.

Glossary

References

1. Leiter A, Veluswamy RR, Wisnivesky JP. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2023) 20:624–39. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3

2. Ferrara R, Ricciuti B, Ambrogio C, Trapani D. The anti–programmed cell death protein-1/programmed death-ligand 1 me-too drugs tsunami: hard to be millennials among baby boomers. J Thorac Oncol. (2023) 18:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.11.001

3. MacManus M, Hegi-Johnson F. Overcoming immunotherapy resistance in NSCLC. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:191–3. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00711-7

4. Pan Y, Fu Y, Zeng Y, Liu X, Peng Y, Hu C, et al. The key to immunotherapy: how to choose better therapeutic biomarkers for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. biomark Res. (2022) 10:1–12. doi: 10.1186/S40364-022-00355-7/TABLES/1

5. Altorki NK, Markowitz GJ, Gao D, Port JL, Saxena A, Stiles B, et al. The lung microenvironment: an important regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. (2019) 19:9–31. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0081-9

6. Baci D, Cekani E, Imperatori A, Ribatti D, Mortara L. Host-related factors as targetable drivers of immunotherapy response in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:914890/BIBTEX. doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2022.914890/BIBTEX

7. Kargl J, Busch SE, Yang GHY, Kim K-H, Hanke ML, Metz HE, et al. Neutrophils dominate the immune cell composition in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:14381. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14381

8. Stankovic B, Bjørhovde HAK, Skarshaug R, Aamodt H, Frafjord A, Müller E, et al. Immune cell composition in human non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. (2019) 9:3101. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03101

9. Reijmen E, De Mey S, De Mey W, Gevaert T, De Ridder K, Locy H, et al. Fractionated radiation severely reduces the number of CD8+ T cells and mature antigen presenting cells within lung tumors. Int J Radiat OncologyBiologyPhysics. (2021) 11:272–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.04.009

10. De Ridder K, Locy H, Piccioni E, Zuazo MI, Awad RM, Verhulst S, et al. TNF-α-secreting lung tumor-infiltrated monocytes play a pivotal role during anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:811867/BIBTEX. doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2022.811867/BIBTEX

11. Lavin Y, Kobayashi S, Leader A, Amir ED, Elefant N, Bigenwald C, et al. Innate immune landscape in early lung adenocarcinoma by paired single-cell analyses. Cell. (2017) 169:750–765.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.014

12. Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2016) 387:1837–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0

13. Higgs BW, Morehouse CA, Streicher K, Brohawn PZ, Pilataxi F, Gupta A, et al. Interferon gamma messenger RNA Signature in tumor biopsies predicts outcomes in patients with non–small cell lung carcinoma or urothelial cancer treated with durvalumab. Clin Cancer Res. (2018) 24:3857–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3451/73799/AM/INTERFERON-GAMMA-MESSENGER-RNA-SIGNATURE-IN-TUMOR

14. Thompson JC, Davis C, Deshpande C, Hwang WT, Jeffries S, Huang A, et al. Gene signature of antigen processing and presentation machinery predicts response to checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. (2020) 8:e000974. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000974

15. Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, Murphy E, Loboda A, Kaufman DR, et al. IFN-γ–related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:2930–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI91190

16. Nielsen TJ, Ring BZ, Seitz RS, Hout DR, Schweitzer BL. A novel immuno-oncology algorithm measuring tumor microenvironment to predict response to immunotherapies. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e06438. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06438

17. Huang AC, Orlowski RJ, Xu X, Mick R, George SM, Yan PK, et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat Med. (2019) 25:454–61. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0357-y

18. Cristescu R, Nebozhyn M, Zhang C, Albright A, Kobie J, Huang L, et al. Transcriptomic determinants of response to pembrolizumab monotherapy across solid tumor types. Clin Cancer Res. (2022) 28:1680–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3329/674450/AM/TRANSCRIPTOMIC-DETERMINANTS-OF-RESPONSE-TO

19. Hwang S, Kwon AY, Jeong JY, Kim S, Kang H, Park J, et al. Immune gene signatures for predicting durable clinical benefit of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57218-9

20. Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X, et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med. (2018) 24:1550–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1

21. Wu H, Qin J, Zhao Q, Lu L, Li C. Microdissection of the bulk transcriptome at single-cell resolution reveals clinical significance and myeloid cells heterogeneity in lung adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:723908. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.723908

22. Salcher S, Sturm G, Horvath L, Untergasser G, Kuempers C, Fotakis G, et al. High-resolution single-cell atlas reveals diversity and plasticity of tissue-resident neutrophils in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. (2022) 40:1503–1520.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.10.008

23. Peng H, Wu X, Liu S, He M, Tang C, Wen Y, et al. Cellular dynamics in tumour microenvironment along with lung cancer progression underscore spatial and evolutionary heterogeneity of neutrophil. Clin Transl Med. (2023) 13. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1340

24. Sangaletti S, Ferrara R, Tripodo C, Garassino MC, Colombo MP. Myeloid cell heterogeneity in lung cancer: implication for immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2021) 70:2429–38. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-02916-5

25. Zilionis R, Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Savova V, Zemmour D, Saatcioglu HD, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human and mouse lung cancers reveals conserved myeloid populations across individuals and species. Immunity. (2019) 50:1317–1334.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.009

26. Leader AM, Grout JA, Maier BB, Nabet BY, Park MD, Tabachnikova A, et al. Single-cell analysis of human non-small cell lung cancer lesions refines tumor classification and patient stratification. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:1594–1609.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.10.009

27. Lambrechts D, Wauters E, Boeckx B, Aibar S, Nittner D, Burton O, et al. Phenotype molding of stromal cells in the lung tumor microenvironment. Nat Med. (2018) 24:1277–89. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0096-5

28. Awad RM, De Vlaeminck Y, Maebe J, Goyvaerts C, Breckpot K. Turn back the TIMe: targeting tumor infiltrating myeloid cells to revert cancer progression. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1977. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01977

29. Pellin D, Loperfido M, Baricordi C, Wolock SL, Montepeloso A, Weinberg OK, et al. A comprehensive single cell transcriptional landscape of human hematopoietic progenitors. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10291-0

30. Dzierzak E, Bigas A. Blood development: hematopoietic stem cell dependence and independence. Cell Stem Cell. (2018) 22:639–51. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.015

31. Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity. (2016) 44:439–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024

32. Liu Z, Gu Y, Chakarov S, Bleriot C, Kwok I, Chen X, et al. Fate mapping via ms4a3-expression history traces monocyte-derived cells. Cell. (2019) 178:1509–1525.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.009

33. Olsson A, Venkatasubramanian M, Chaudhri VK, Aronow BJ, Salomonis N, Singh H, et al. Single-cell analysis of mixed-lineage states leading to a binary cell fate choice. Nature. (2016) 537:698. doi: 10.1038/nature19348

34. Yáñez A, Coetzee SG, Olsson A, Muench DE, Berman BP, Hazelett DJ, et al. Granulocyte-monocyte progenitors and monocyte-dendritic cell progenitors independently produce functionally distinct monocytes. Immunity. (2017) 47:890–902.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.021

35. Giladi A, Paul F, Herzog Y, Lubling Y, Weiner A, Yofe I, et al. Single-cell characterization of haematopoietic progenitors and their trajectories in homeostasis and perturbed haematopoiesis. Nat Cell Biol. (2018) 20:836–46. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0121-4

36. Paul F, Arkin Y, Giladi A, Jaitin DA, Kenigsberg E, Keren-Shaul H, et al. Transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment in myeloid progenitors. Cell. (2015) 163:1663–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.013

37. Sommerkamp P, Romero-Mulero MC, Narr A, Ladel L, Hustin L, Schönberger K, et al. Mouse multipotent progenitor 5 cells are located at the interphase between hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. (2021) 137:3218–24. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007876

38. Challen GA, Pietras EM, Wallscheid NC, Signer RAJ. Simplified murine multipotent progenitor isolation scheme: Establishing a consensus approach for multipotent progenitor identification. Exp Hematol. (2021) 104:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2021.09.007

39. Klein F, Roux J, Cvijetic G, Rodrigues PF, von Muenchow L, Lubin R, et al. Dntt expression reveals developmental hierarchy and lineage specification of hematopoietic progenitors. Nat Immunol. (2022) 23:505–17. doi: 10.1038/s41590-022-01167-5

40. Rodriguez-Fraticelli AE, Wolock SL, Weinreb CS, Panero R, Patel SH, Jankovic M, et al. Clonal analysis of lineage fate in native haematopoiesis. Nature. (2018) 553:212–6. doi: 10.1038/nature25168

41. Laurenti E, Göttgens B. From haematopoietic stem cells to complex differentiation landscapes. Nature. (2018) 553:418–26. doi: 10.1038/nature25022

42. Amann-Zalcenstein D, Tian L, Schreuder J, Tomei S, Lin DS, Fairfax KA, et al. A new lymphoid-primed progenitor marked by Dach1 downregulation identified with single cell multi-omics. Nat Immunol. (2020) 21:1574–84. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0799-x

43. DeKoter RP, Singh H. Regulation of B lymphocyte and macrophage development by graded expression of PU.1. Science. (2000) 288:1439–42. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1439

44. Favaro P, Glass DR, Borges L, Baskar R, Reynolds W, Ho D, et al. Unravelling human hematopoietic progenitor cell diversity through association with intrinsic regulatory factors. bioRxiv. (2023). doi: 10.1101/2023.08.30.555623

45. Keita S, Diop S, Lekiashvili S, Chalmel F, Hussen KA, Canque B. Distinct subsets of multi-lymphoid progenitors support ontogeny-related changes in human lymphopoiesis. CellReports. (2023) 42:112618. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112618

46. Jacobsen SEW, Nerlov C. Haematopoiesis in the era of advanced single-cell technologies. Nat Cell Biol. (2019) 21:2–8. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0227-8

47. Dutertre CA, Becht E, Irac SE, Khalilnezhad A, Narang V, Khalilnezhad S, et al. Single-cell analysis of human mononuclear phagocytes reveals subset-defining markers and identifies circulating inflammatory dendritic cells. Immunity. (2019) 51:573–589.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.008

48. Liu Z, Wang H, Li Z, Dress RJ, Zhu Y, Zhang S, et al. Dendritic cell type 3 arises from Ly6C+ monocyte-dendritic cell progenitors. Immunity. (2023) 56:1761–1777.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.07.001

49. Rodrigues PF, Alberti-Servera L, Eremin A, Grajales-Reyes GE, Ivanek R, Tussiwand R. Distinct progenitor lineages contribute to the heterogeneity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. (2018) 19:711–22. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0136-9

50. Waskow C, Liu K, Darrasse-Jèze G, Guermonprez P, Ginhoux F, Merad M, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase Flt3 is required for dendritic cell development in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Nat Immunol. (2008) 9:676–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1615

51. Chong SZ, Evrard M, Devi S, Chen J, Lim JY, See P, et al. CXCR4 identifies transitional bone marrow premonocytes that replenish the mature monocyte pool for peripheral responses. J Exp Med. (2016) 213:2293–314. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160800

52. Basu J, Olsson A, Ferchen K, Titerina EK, ChEtal K, Nicolas E, et al. ThPOK is a critical multifaceted regulator of myeloid lineage development. Nat Immunol. (2023) 24:1295–307. doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01549-3

53. Evrard M, Kwok IWH, Chong SZ, Teng KWW, Becht E, Chen J, et al. Developmental analysis of bone marrow neutrophils reveals populations specialized in expansion, trafficking, and effector functions. Immunity. (2018) 48:364–379.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.002

54. Kwok I, Becht E, Xia Y, Ng M, Teh YC, Tan L, et al. Combinatorial single-cell analyses of granulocyte-monocyte progenitor heterogeneity reveals an early uni-potent neutrophil progenitor. Immunity. (2020) 53:303–318.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.005

55. Xie X, Shi Q, Wu P, Zhang X, Kambara H, Su J, et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling reveals neutrophil heterogeneity in homeostasis and infection. Nat Immunol. (2020) 21:1119–33. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0736-z

56. Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, Link DC. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest. (2010) 120:2423–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI41649

57. Drissen R, Thongjuea S, Theilgaard-Mönch K, Nerlov C. Identification of two distinct pathways of human myelopoiesis. Sci Immunol. (2019) 4:7148. doi: 10.1126/SCIIMMUNOL.AAU7148/SUPPL_FILE/AAU7148_TABLE_S5.XLSX

58. Drissen R, Buza-Vidas N, Woll P, Thongjuea S, Gambardella A, Giustacchini A, et al. Distinct myeloid progenitor-differentiation pathways identified through single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Immunol. (2016) 17:666–76. doi: 10.1038/ni.3412

59. Tusi BK, Wolock SL, Weinreb C, Hwang Y, Hidalgo D, Zilionis R, et al. Population snapshots predict early haematopoietic and erythroid hierarchies. Nature. (2018) 555:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nature25741

60. Ng AP, Alexander WS. Haematopoietic stem cells: Past, present and future. Cell Death Discovery. (2017) 3. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.2

61. Baccin C, Al-Sabah J, Velten L, Helbling PM, Grünschläger F, Hernández-Malmierca P, et al. Combined single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal the molecular, cellular and spatial bone marrow niche organization. Nat Cell Biol. (2019) 22:38–48. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0439-6

62. Ribatti D, D’amati A. Hematopoiesis and mast cell development. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24. doi: 10.3390/ijms241310679

63. Gomariz A, Helbling PM, Isringhausen S, Suessbier U, Becker A, Boss A, et al. Quantitative spatial analysis of haematopoiesis-regulating stromal cells in the bone marrow microenvironment by 3D microscopy. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04770-z

64. Li H, Bräunig S, Dhapolar P, Karlsson G, Lang S, Scheding S. Identification of phenotypically, functionally, and anatomically distinct stromal niche populations in human bone marrow based on single-cell RNA sequencing. Elife. (2023) 12. doi: 10.7554/eLife.81656

65. Mann Z, Sengar M, Verma YK, Rajalingam R, Raghav PK. Hematopoietic stem cell factors: their functional role in self-renewal and clinical aspects. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2022) 10:664261/BIBTEX. doi: 10.3389/FCELL.2022.664261/BIBTEX

66. Ding L, Morrison SJ. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature. (2013) 495:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11885

67. Khatib-Massalha E, Méndez-Ferrer S. Megakaryocyte diversity in ontogeny, functions and cell-cell interactions. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:840044. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.840044

68. Itkin T, Gur-Cohen S, Spencer JA, Schajnovitz A, Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP, et al. Distinct bone marrow blood vessels differentially regulate hematopoiesis. Nature. (2016) 532:323. doi: 10.1038/nature17624

69. Kunisaki Y, Bruns I, Scheiermann C, Ahmed J, Pinho S, Zhang D, et al. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. (2013) 502:637–43. doi: 10.1038/nature12612

70. Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. (2003) 425:841–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02040

71. Visnjic D, Kalajzic Z, Rowe DW, Katavic V, Lorenzo J, Aguila HL. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood. (2004) 103:3258–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4011

72. Lymperi S, Ersek A, Ferraro F, Dazzi F, Horwood NJ. Inhibition of osteoclast function reduces hematopoietic stem cell numbers in vivo. Blood. (2011) 117:1540–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282855

73. Kollet O, Dar A, Lapidot T. The multiple roles of osteoclasts in host defense: bone remodeling and hematopoietic stem cell mobilization. Annu Rev Immunol. (2007) 25:51–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141631

74. Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. (2012) 481:457. doi: 10.1038/nature10783

75. Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. (2006) 25:977–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016

76. Acar M, Kocherlakota KS, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Oguro H, Inra CN, et al. Deep imaging of bone marrow shows non-dividing stem cells are mainly perisinusoidal. Nature. (2015) 526:126–30. doi: 10.1038/nature15250

77. Omatsu Y, Seike M, Sugiyama T, Kume T, Nagasawa T. Foxc1 is a critical regulator of haematopoietic stem/progenitor cell niche formation. Nature. (2014) 508:536–40. doi: 10.1038/nature13071

78. Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, MacArthur BD, Lira SA, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. (2010) 466:829–34. doi: 10.1038/nature09262

79. Kfoury Y, Scadden DT. Mesenchymal cell contributions to the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. (2015) 16:239–53. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.019

80. Anthony BA, Link DC. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cells by bone marrow stromal cells. Trends Immunol. (2014) 35:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.002

81. Cordeiro Gomes A, Hara T, Lim VY, Herndler-Brandstetter D, Nevius E, Sugiyama T, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell niches produce lineage-instructive signals to control multipotent progenitor differentiation. Immunity. (2016) 45:1219–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.11.004

82. Greenbaum A, Hsu YMS, Day RB, Schuettpelz LG, Christopher MJ, Borgerding JN, et al. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature. (2013) 495:227–30. doi: 10.1038/nature11926

83. Luis TC, Barkas N, Carrelha J, Giustacchini A, Mazzi S, Norfo R, et al. Perivascular niche cells sense thrombocytopenia and activate hematopoietic stem cells in an IL-1 dependent manner. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41691-y

84. Xing X, Yang F, Huang Q, Guo H, Li J, Qiu M, et al. Decoding the multicellular ecosystem of lung adenocarcinoma manifested as pulmonary subsolid nodules by single-cell RNA sequencing. Sci Adv. (2021) 7. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd9738

85. Wu F, Fan J, He Y, Xiong A, Yu J, Li Y, et al. Single-cell profiling of tumor heterogeneity and the microenvironment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22801-0

86. Laughney AM, Hu J, Campbell NR, Bakhoum SF, Setty M, Lavallée VP, et al. Regenerative lineages and immune-mediated pruning in lung cancer metastasis. Nat Med. (2020) 26:259–69. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0750-6

87. Kim N, Kim HK, Lee K, Hong Y, Cho JH, Choi JW, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrates the molecular and cellular reprogramming of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Commun. (2020) 11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16164-1

88. Maier B, Leader AM, Chen ST, Tung N, Chang C, LeBerichel J, et al. A conserved dendritic-cell regulatory program limits antitumour immunity. Nature. (2020) 580:257–62. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2134-y

89. Cheng S, Li Z, Gao R, Xing B, Gao Y, Yang Y, et al. A pan-cancer single-cell transcriptional atlas of tumor infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell. (2021) 184:792–809.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.010

90. Hu J, Zhang L, Xia H, Yan Y, Zhu X, Sun F, et al. Tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Genome Med. (2023) 15:14. doi: 10.1186/s13073-023-01164-9

91. Sinjab A, Han G, Treekitkarnmongkol W, Hara K, Brennan PM, Dang M, et al. Resolving the spatial and cellular architecture of lung adenocarcinoma by multiregion single-cell sequencing. Cancer Discovery. (2021) 11:2506–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1285

92. Casanova-Acebes M, Dalla E, Leader AM, LeBerichel J, Nikolic J, Morales BM, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages provide a pro-tumorigenic niche to early NSCLC cells. Nature. (2021) 595:578–84. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03651-8

93. Chen H, Song A, Rehman FU, Han D. Multidimensional progressive single-cell sequencing reveals cell microenvironment composition and cancer heterogeneity in lung cancer. Environ Toxicol. (2023) 39:890–904. doi: 10.1002/TOX.24018

94. Kvedaraite E, Ginhoux F. Human dendritic cells in cancer. Sci Immunol. (2022) 7. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abm9409

95. Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Ricca JM, Gasmi B, De Henau O, Mangarin LM, Redmond D, et al. T cell immunotherapies trigger neutrophil activation to eliminate tumor antigen escape variants. SSRN Electronic J. (2020). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3596599

96. Quail DF, Amulic B, Aziz M, Barnes BJ, Eruslanov E, Fridlender ZG, et al. Neutrophil phenotypes and functions in cancer: A consensus statement. J Exp Med. (2022) 219. doi: 10.1084/jem.20220011

97. Takam Kamga P, Mayenga M, Sebane L, Costantini A, Julie C, Capron C, et al. Colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) signalling is predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. (2024) 188:107447. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2023.107447

98. Moeller A, Kurzrock R, Botta GP, Adashek JJ, Patel H, Lee S, et al. Challenges and prospects of CSF1R targeting for advanced Malignancies. Am J Cancer Res. (2023) 13:3257–65.

99. Young MRI, Young ME, Wright MA. Myelopoiesis-associated suppressor-cell activity in mice with lewis lung carcinoma tumors: Interferon-γ plus tumor necrosis factor-α synergistically reduce suppressor cell activity. Int J Cancer. (1990) 46:245–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460217

100. Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, Friedrich M, Ferris B, Hackett NR, et al. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of Kit-ligand. Cell. (2002) 109:625–37. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00754-7

101. Lyden D, Hattori K, Dias S, Costa C, Blaikie P, Butros L, et al. Impaired recruitment of bone-marrow-derived endothelial and hematopoietic precursor cells blocks tumor angiogenesis and growth. Nat Med. (2001) 7:1194–201. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1194

102. Kopp HG, Ramos CA, Rafii S. Contribution of endothelial progenitors and proangiogenic hematopoietic cells to vascularization of tumor and ischemic tissue. Curr Opin Hematol. (2006) 13:175. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000219664.26528.da

103. Ruzinova MB, Schoer RA, Gerald W, Egan JE, Pandolfi PP, Rafii S, et al. Effect of angiogenesis inhibition by Id loss and the contribution of bone-marrow-derived endothelial cells in spontaneous murine tumors. Cancer Cell. (2003) 4:277–89. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00240-X

104. Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. (2005) 438:820–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04186

105. Okamoto R, Ueno M, Yamada Y, Takahashi N, Sano H, Suda T, et al. Hematopoietic cells regulate the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Blood. (2005) 105:2757–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3317

106. Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. (2006) 8:1369–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb1507

107. Shojaei F, Wu X, Malik AK, Zhong C, Baldwin ME, Schanz S, et al. Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b +Gr1+ myeloid cells. Nat Biotechnol. (2007) 25:911–20. doi: 10.1038/nbt1323

108. Morales JK, Kmieciak M, Knutson KL, Bear HD, Manjili MH. GM-CSF is one of the main breast tumor-derived soluble factors involved in the differentiation of CD11b-Gr1- bone marrow progenitor cells into myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2010) 123:39–49. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0622-8

109. Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Ugel S, Marigo I, Gomez AF, Mesa C, et al. Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. Eur J Immunol. (2010) 40:22–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939903

110. Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, Lang G, Bird D, Koong A, et al. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. (2009) 15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012

111. Elkabets M, Gifford AM, Scheel C, Nilsson B, Reinhardt F, Bray MA, et al. Human tumors instigate granulin-expressing hematopoietic cells that promote Malignancy by activating stromal fibroblasts in mice. J Clin Invest. (2011) 121:784–99. doi: 10.1172/JCI43757

112. McAllister SS, Gifford AM, Greiner AL, Kelleher SP, Saelzler MP, Ince TA, et al. Systemic endocrine instigation of indolent tumor growth requires osteopontin. Cell. (2008) 133:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.045

113. Huynh HD, Zheng J, Umikawa M, Silvany R, Xie XJ, Wu CJ, et al. Components of the hematopoietic compartments in tumor stroma and tumor-bearing mice. PloS One. (2011) 6:18054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018054

114. Peinado H, Alečković M, Lavotshkin S, Matei I, Costa-Silva B, Moreno-Bueno G, et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med. (2012) 18:883–91. doi: 10.1038/nm.2753

115. Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Lee KE, Hajdu CH, Miller G, Bar-Sagi D. Oncogenic kras-induced GM-CSF production promotes the development of pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Cell. (2012) 21:836–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.024

116. Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, et al. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. (2012) 21:822–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025

117. Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A, Rauch PJ, Chudnovskiy A, Berger C, et al. Origins of tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2012) 109:2491–6. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1113744109/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.201113744SI.PDF

118. Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A, Ryan R, Pucci F, Sio SW, et al. Angiotensin II drives the production of tumor-promoting macrophages. Immunity. (2013) 38:296. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.015

119. Mastio J, Condamine T, Dominguez G, Kossenkov AV, Donthireddy L, Veglia F, et al. Identification of monocyte-like precursors of granulocytes in cancer as a mechanism for accumulation of PMN-MDSCs. J Exp Med. (2019) 216:2150–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181952

120. Youn JI, Kumar V, Collazo M, Nefedova Y, Condamine T, Cheng P, et al. Epigenetic silencing of retinoblastoma gene regulates pathologic differentiation of myeloid cells in cancer. Nat Immunol. (2013) 14:211–20. doi: 10.1038/ni.2526

121. Sio A, Chehal MK, Tsai K, Fan X, Roberts ME, Nelson BH, et al. Dysregulated hematopoiesis caused by mammary cancer is associated with epigenetic changes and Hox gene expression in hematopoietic cells. Cancer Res. (2013) 73:5892–904. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0842

122. Wu WC, Sun HW, Chen HT, Liang J, Yu XJ, Wu C, et al. Circulating hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells are myeloid-biased in cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2014) 111:4221–6. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1320753111/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.201320753SI.PDF

123. Coffelt SB, Kersten K, Doornebal CW, Weiden J, Vrijland K, Hau CS, et al. IL-17-producing γδ T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. (2015) 522:345–8. doi: 10.1038/nature14282

124. Casbon AJ, Reynau D, Park C, Khu E, Gan DD, Schepers K, et al. Invasive breast cancer reprograms early myeloid differentiation in the bone marrow to generate immunosuppressive neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2015) 112:E566–75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424927112

125. Pu S, Qin B, He H, Zhan J, Wu Q, Zhang X, et al. Identification of early myeloid progenitors as immunosuppressive cells. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep23115

126. Giles AJ, Reid CM, De Wayne Evans J, Murgai M, Vicioso Y, Highfill SL, et al. Activation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells promotes immunosuppression within the pre-metastatic niche. Cancer Res. (2016) 76:1335–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0204

127. Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Zilionis R, Da Silva Martins J, Bos SA, Courties G, et al. Osteoblasts remotely supply lung tumors with cancer-promoting SiglecFhigh neutrophils. Science. (2017) 358. doi: 10.1126/science.aal5081

128. Pfirschke C, Engblom C, Gungabeesoon J, Lin Y, Rickelt S, Zilionis R, et al. Tumor-promoting ly-6G+ SiglecFhigh cells are mature and long-lived neutrophils. Cell Rep. (2020) 32:108164. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108164

129. Patel S, Fu S, Mastio J, Dominguez GA, Purohit A, Kossenkov A, et al. Unique pattern of neutrophil migration and function during tumor progression. Nat Immunol. (2018) 19:1236–47. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0229-5

130. Meyer MA, Baer JM, Knolhoff BL, Nywening TM, Panni RZ, Su X, et al. Breast and pancreatic cancer interrupt IRF8-dependent dendritic cell development to overcome immune surveillance. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03600-6

131. Zhu YP, Padgett L, Dinh HQ, Marcovecchio P, Blatchley A, Wu R, et al. Identification of an early unipotent neutrophil progenitor with pro-tumoral activity in mouse and human bone marrow. Cell Rep. (2018) 24:2329–2341.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.097

132. Al Sayed MF, Amrein MA, Buhrer ED, Huguenin AL, Radpour R, Riether C, et al. T-cell-secreted TNFα Induces emergency myelopoiesis and myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation in cancer. Cancer Res. (2019) 79:346–59. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3026

133. Dinh HQ, Eggert T, Meyer MA, Zhu YP, Olingy CE, Llewellyn R, et al. Coexpression of CD71 and CD117 identifies an early unipotent neutrophil progenitor population in human bone marrow. Immunity. (2020) 53:319–334.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.017

134. Allen BM, Hiam KJ, Burnett CE, Venida A, DeBarge R, Tenvooren I, et al. Systemic dysfunction and plasticity of the immune macroenvironment in cancer models. Nat Med. (2020) 26:1125–34. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0892-6

135. Long H, Jia Q, Wang L, Fang W, Wang Z, Jiang T, et al. Tumor-induced erythroid precursor-differentiated myeloid cells mediate immunosuppression and curtail anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment efficacy. Cancer Cell. (2022) 40:674–693.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.04.018

136. Zhao L, He R, Long H, Guo B, Jia Q, Qin D, et al. Late-stage tumors induce anemia and immunosuppressive extramedullary erythroid progenitor cells. Nat Med. (2018) 24:1536–44. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0205-5

137. Wang B, Wang Y, Chen H, Yao S, Lai X, Qiu Y, et al. Inhibition of TGFβ improves hematopoietic stem cell niche and ameliorates cancer-related anemia. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2021) 12:65. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-02120-9

138. Zhang W, Bado IL, Hu J, Wan YW, Wu L, Wang H, et al. The bone microenvironment invigorates metastatic seeds for further dissemination. Cell. (2021) 184:2471–2486.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.011

139. Chiodoni C, Cancila V, Renzi TA, Perrone M, Tomirotti AM, Sangaletti S, et al. Transcriptional profiles and stromal changes reveal bone marrow adaptation to early breast cancer in association with deregulated circulating microRNAs. Cancer Res. (2020) 80:484–98. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1425

140. Perrone M, Chiodoni C, Lecchi M, Botti L, Bassani B, Piva A, et al. ATF3 reprograms the bone marrow niche in response to early breast cancer transformation. Cancer Res. (2022) 83:117–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-0651

141. Gerber-Ferder Y, Cosgrove J, Duperray-Susini A, Missolo-Koussou Y, Dubois M, Stepaniuk K, et al. Breast cancer remotely imposes a myeloid bias on haematopoietic stem cells by reprogramming the bone marrow niche. Nat Cell Biol. (2023) 25:1736–45. doi: 10.1038/s41556-023-01291-w