94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol., 06 February 2023

Sec. Multiple Sclerosis and Neuroimmunology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1088039

Samuel J. Duesman1†

Samuel J. Duesman1† Sandra Ortega-Francisco2,3†

Sandra Ortega-Francisco2,3† Roxana Olguin-Alor3

Roxana Olguin-Alor3 Naray A. Acevedo-Dominguez2

Naray A. Acevedo-Dominguez2 Christine M. Sestero4

Christine M. Sestero4 Rajeshwari Chellappan5

Rajeshwari Chellappan5 Patrizia De Sarno6

Patrizia De Sarno6 Nabiha Yusuf1

Nabiha Yusuf1 Adrian Salgado-Lopez2

Adrian Salgado-Lopez2 Marisol Segundo-Liberato2,3

Marisol Segundo-Liberato2,3 Selina Montes de Oca-Lagunas2

Selina Montes de Oca-Lagunas2 Chander Raman1*

Chander Raman1* Gloria Soldevila2,3*

Gloria Soldevila2,3*The transforming growth factor receptor III (TβRIII) is commonly recognized as a co-receptor that promotes the binding of TGFβ family ligands to type I and type II receptors. Within the immune system, TβRIII regulates T cell development in the thymus and is differentially expressed through activation; however, its function in mature T cells is unclear. To begin addressing this question, we developed a conditional knock-out mouse with restricted TβRIII deletion in mature T cells, necessary because genomic deletion of TβRIII results in perinatal mortality. We determined that TβRIII null mice developed more severe autoimmune central nervous neuroinflammatory disease after immunization with myelin oligodendrocyte peptide (MOG35-55) than wild-type littermates. The increase in disease severity in TβRIII null mice was associated with expanded numbers of CNS infiltrating IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells and cells that co-express both IFNγ and IL-17 (IFNγ+/IL-17+), but not IL-17 alone expressing CD4 T cells compared to Tgfbr3fl/fl wild-type controls. This led us to speculate that TβRIII may be involved in regulating conversion of encephalitogenic Th17 to Th1. To directly address this, we generated encephalitogenic Th17 and Th1 cells from wild type and TβRIII null mice for passive transfer of EAE into naïve mice. Remarkably, Th17 encephalitogenic T cells from TβRIII null induced EAE of much greater severity and earlier in onset than those from wild-type mice. The severity of EAE induced by encephalitogenic wild-type and Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre Th1 cells were similar. Moreover, in vitro restimulation of in vivo primed Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre T cells, under Th17 but not Th1 polarizing conditions, resulted in a significant increase of IFNγ+ T cells. Altogether, our data indicate that TβRIII is a coreceptor that functions as a key checkpoint in controlling the pathogenicity of autoreactive T cells in neuroinflammation probably through regulating plasticity of Th17 T cells into pathogenic Th1 cells. Importantly, this is the first demonstration that TβRIII has an intrinsic role in T cells.

Transforming growth factor receptor III (TβRIII), also known as Betaglycan, is a surface proteoglycan that is broadly expressed in many tissues and cell types (1). It is involved in multiple cellular processes including activation, proliferation, adhesion, migration, and organogenesis (2–4); therefore, Tgfbr3 knockout mice die before E18 embryonic stage (5). Most recently, TβRIII has taken relevance in cancer progression, as its loss promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and enhances the migratory potential of malignant cells, being proposed as an important marker for metastasis prognosis (6–9). The TGFβ superfamily is composed of more than 30 ligands that can be classified into 3 subfamilies: activins and inhibins, bone morphogenic proteins (BMP’s), and TGFβs (including TGFβ1, 2, and 3). The canonical pathway triggered by these ligands involves their binding to TβRII and the subsequent recruitment of TβRI, leading to the phosphorylation of R-SMAD proteins and the activation of the common SMAD protein (SMAD4) which is then translocated to the nucleus to regulate gene expression.

TβRIII has been classically described as a co-receptor promoting the binding of all three isoforms of TGFβ to TβRII (1, 10, 11). TβRIII also binds inhibins, BMPs and Fibroblast Growth Factor (2, 11). In addition to promoting high affinity binding of TGFβ to TβRI and TβRII, TβRIII can also be cleaved from the cell membrane where it binds soluble TGFβ, thereby acting as a ligand trap (12). Considering the key role of TGFβ and other ligands of the TGFβ superfamily in T cell biology (13–15), it is not surprising that TβRIII has been described as an important regulator of T cell maturation and differentiation. This receptor is important for the survival and differentiation of T cells in the thymus, as fetal thymocytes lacking TβRIII exhibit higher apoptosis and a delay in T cell development (16); therefore it is reasonable to think that TβRIII would function as a regulator of mature T cell proliferation and differentiation. In a previous work, we demonstrated that TβRIII is expressed on T cells, highly expressed on CD4+ T cells (preferentially on naïve and central memory CD4+ T subpopulations) compared to CD8+ T cells, but not on B cells, both in mouse and human (17). Additionally, TβRIII was upregulated after TCR stimulation, with similar expression kinetics to other activation markers such as CD25, CD69, and CD44. Interestingly, both thymic and induced Tregs expressed very low levels of TβRIII, as Foxp3 expression is associated with a decreased expression of TβRIII (17). These data suggest that TβRIII may play an important function during T cell activation and/or during TGFβ mediated lineage differentiation.

The activation and differentiation of T cells is a highly regulated process involving several signaling pathways, and under certain circumstances the lack of signal regulation triggers pathologies, such as autoimmune diseases. In this context, TGFβ signaling is crucial as TβRI deficiency in CD4 cells in mice results in the development of spontaneous autoimmunity in mice (18). Similarly, when TβRII is deleted in CD4+ T cells, mice develop lethal inflammation and multi-organ autoimmune inflammatory infiltration (19), however the role of TβRIII in autoimmunity is not yet described.

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), though imperfect, is the best model to study immunopathogenic mechanisms of human multiple sclerosis (MS) (20, 21). CD4+ T cells reactive to myelin antigens initiate the disease and both Th1 and Th17 cells mediate an auto-inflammatory response which results in demyelination and axonal damage in the central nervous system leading to ascending paralysis (22). The developmental of EAE and severity of disease is sensitive to factors that tune thresholds of T cell activation, as well as those that have an impact on differentiation to effector populations. Simply stated, enhanced CD4+ T cell activation, such as attenuation of inhibitory signals or augmentation of co-stimulation will lead to increased disease severity. Conversely, factors that attenuate T cell activation such as increased inhibitory signals or loss of co-stimulation will decrease EAE severity. Factors that promote differentiation to Th1 cells and pathogenic Th17 cells also enhance EAE severity. IL-6 and TGF-β are key first-step cytokines involved in the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells to Th17 cells followed by IL-23 that promotes stability and pathogenicity of Th17 cells (23, 24). Additionally, at least in vitro, low concentrations of TGF-β promote generation of inflammatory Th17 while strong TGF-β signaling will shift balance to regulation (13, 25). After exposure to certain cytokine (IL-23 and IL-12) cues and signals, Th17 cells can also undergo a process described as plasticity that leads transdifferentiation to IFN-γ expressing Th1-like cells through an intermediate that expresses both IL-17 and IFN-γ (Th17/1 cells) (26, 27). The transdifferentiation promotes pathogenicity in EAE. During this transdifferentiation process, Th17 cells gain the expression of Tbet and may downmodulate expression of the master regulator RORγt (28). Severity of EAE and by extension progression of MS disease will be impacted by molecules that modulate Th17 pathogenicity and transdifferentiation.

To interrogate the function of TβRIII in T cells, we generated a mature T cell specific loss of function mutant mouse. Using this novel mouse, we show that T cell specific TβRIII null mice develop normally, have no obvious alterations in peripheral T cell populations and they respond equivalent to wild type to in vitro activation and CD4+ effector T cell differentiation. Induction of EAE in TβRIII null mice leads to greater severity of disease that is associated with expansion of IFN-γ and Th17/1 cells but not Th17 in the central nervous system (CNS). However, encephalitogenic TβRIII null Th17 cells but not Th1 cells are more pathogenic in the context of ability to induce EAE in naïve recipient mice. Overall, our data uncovers a biology of CD4+ T cell specific expression of TβRIII in restraining Th17 pathogenicity.

Tgfbr3fl/fl mice were generated at UAB transgenic/ES core facility using ES cells obtained from EUCOMM. B6.Cg-Tg(Lck-icre)3779Nik/J (dLckCre) were obtained from JAX and bred to Tgfbr3fl/fl mice to generate Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and littermate Tgfbr3fl/fl mice. Female and male eight- to twelve-week-old littermate mice were used in all the experiments. All animals were bred and maintained in the animal facility at the University of Alabama and the Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas (IIB, UNAM, Mexico), in specific pathogen-free conditions, according to the ethical guidelines from the National Institute of Health, the Committee of Animal Care and Use at UAB and the Comité para el Cuidado y Uso de Animales de Laboratorio (CICUAL) at the IIB UNAM (protocol #176), that describe methods of sacrifice, methods of anesthesia and/or analgesia, and efforts to alleviate suffering.

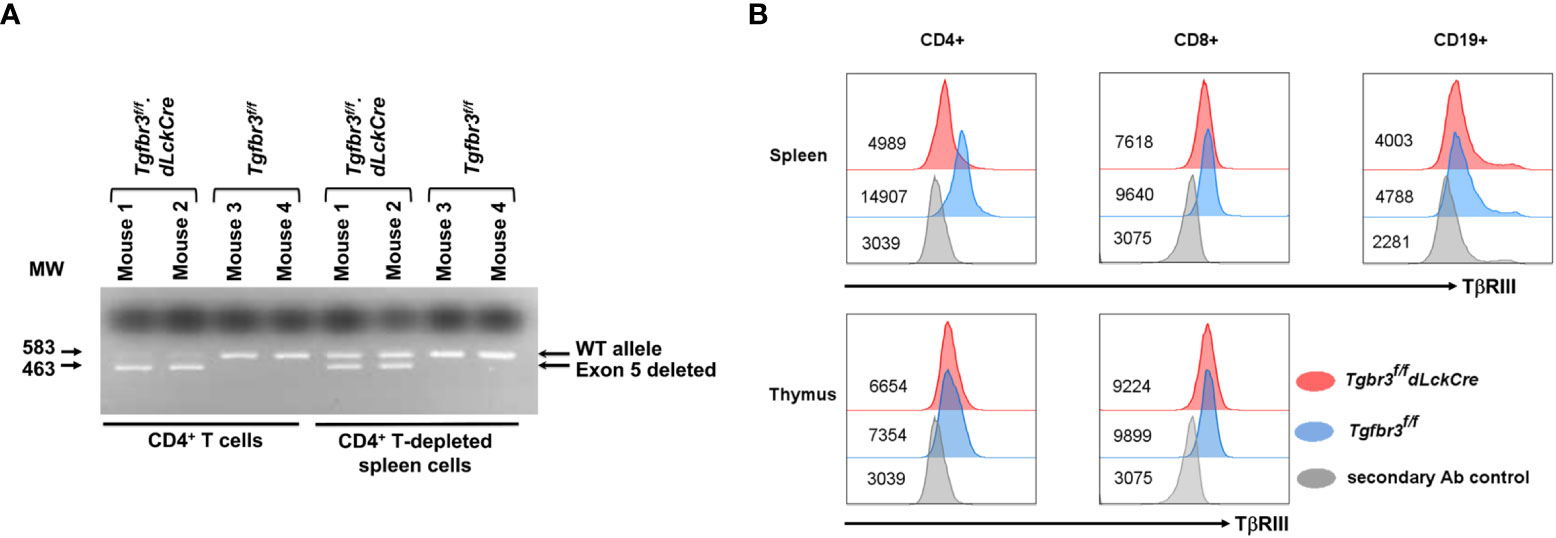

The deletion of Tgfbr3 Exon 5 was assessed by PCR on DNA isolated from T CD4+ cells and compared with CD4-depleted splenocytes using the following primers: forward (TGF5FOR1) TGTTGTGGTGACTGTTGGCA and reverse (TGFEX1FOR1) GTTTCGGAGGGTTCTGTGGT. PCR was performed using the AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Thermo fisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

To evaluate the loss of TβRIII expression on peripheral T cells, we used a goat anti-mouse TβRIII antibody followed by incubation with a donkey anti-goat IgG AF488 secondary antibody on live CD4+, CD8+, and CD19+ cells. Specifications of antibodies used can be found on Supplementary Material (Table 1) . Secondary antibody (Ab) staining was used as negative control for both thymocytes and splenocytes from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice. Samples were acquired in the NxT cytometer (Thermo fisher) and analyzed with FlowJo X software (BD, San Jose, CA).

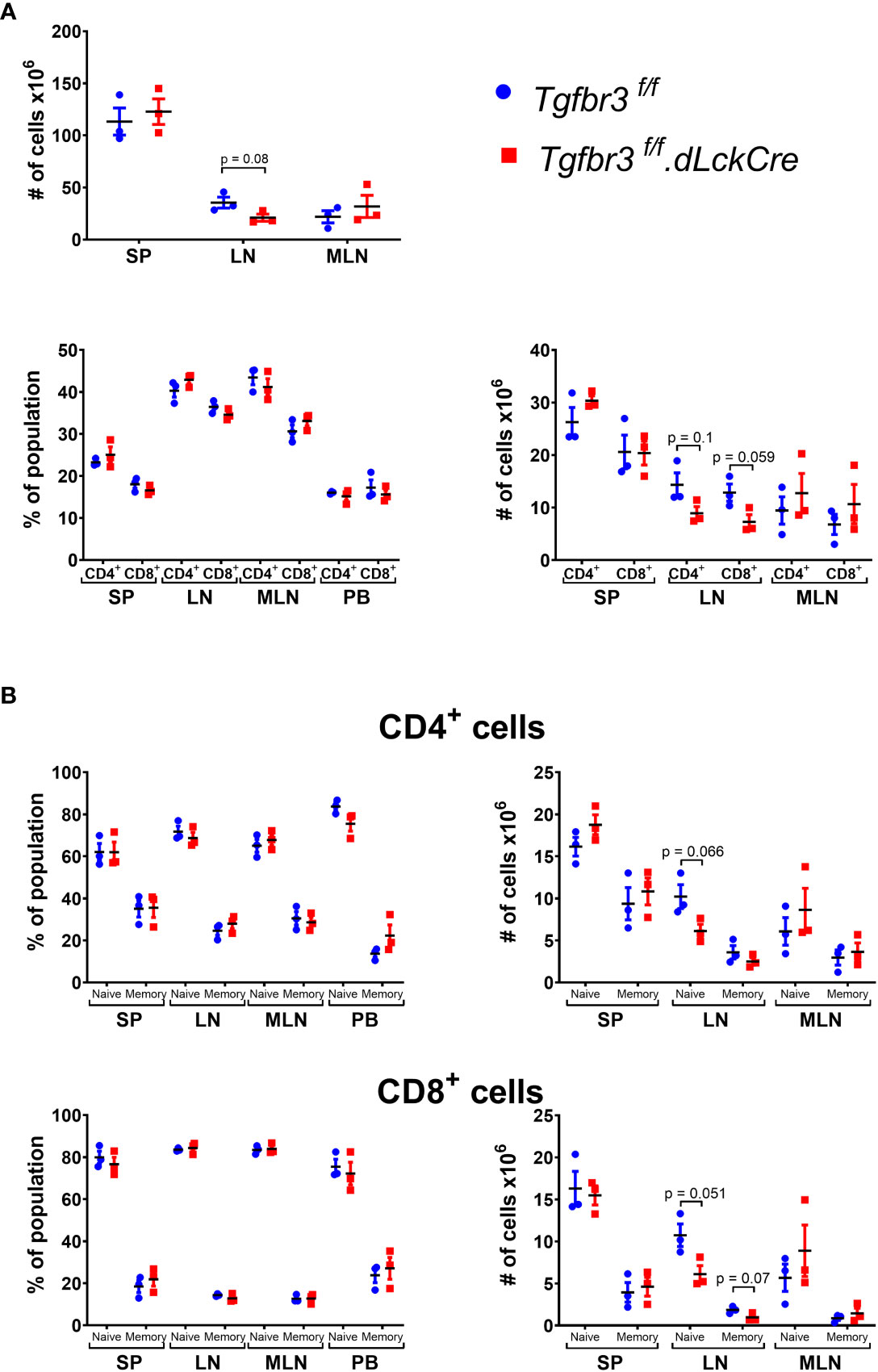

Spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, peripheral lymph nodes, and blood samples were obtained from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice. Cells were homogenized, counted, and 1x106 cells were stained with different antibody panels to analyze B cells (CD19+), T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) and among these, naïve T cells (CD44lo CD62Lhi CCR7+), central memory (CD44hiCD62L+CCR7+), and effector memory T cells (CD44hiCD62L-CCR7-). The complete list of antibodies is shown in Supplementary Material (Table 1). Briefly, antibodies were diluted in PBS and cells stained with 50μL of the antibody mix for 30 min at 37°C (for optimal staining of CCR7). Then, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 5 min, washed and resuspended in FACs buffer before acquisition. In the case of blood, erythrocyte lysis was performed after staining with ACK buffer. Samples were acquired in the Cytoflex S (Beckman Coulter) cytometer and sample data analysis was done using FlowJo X software (BD).

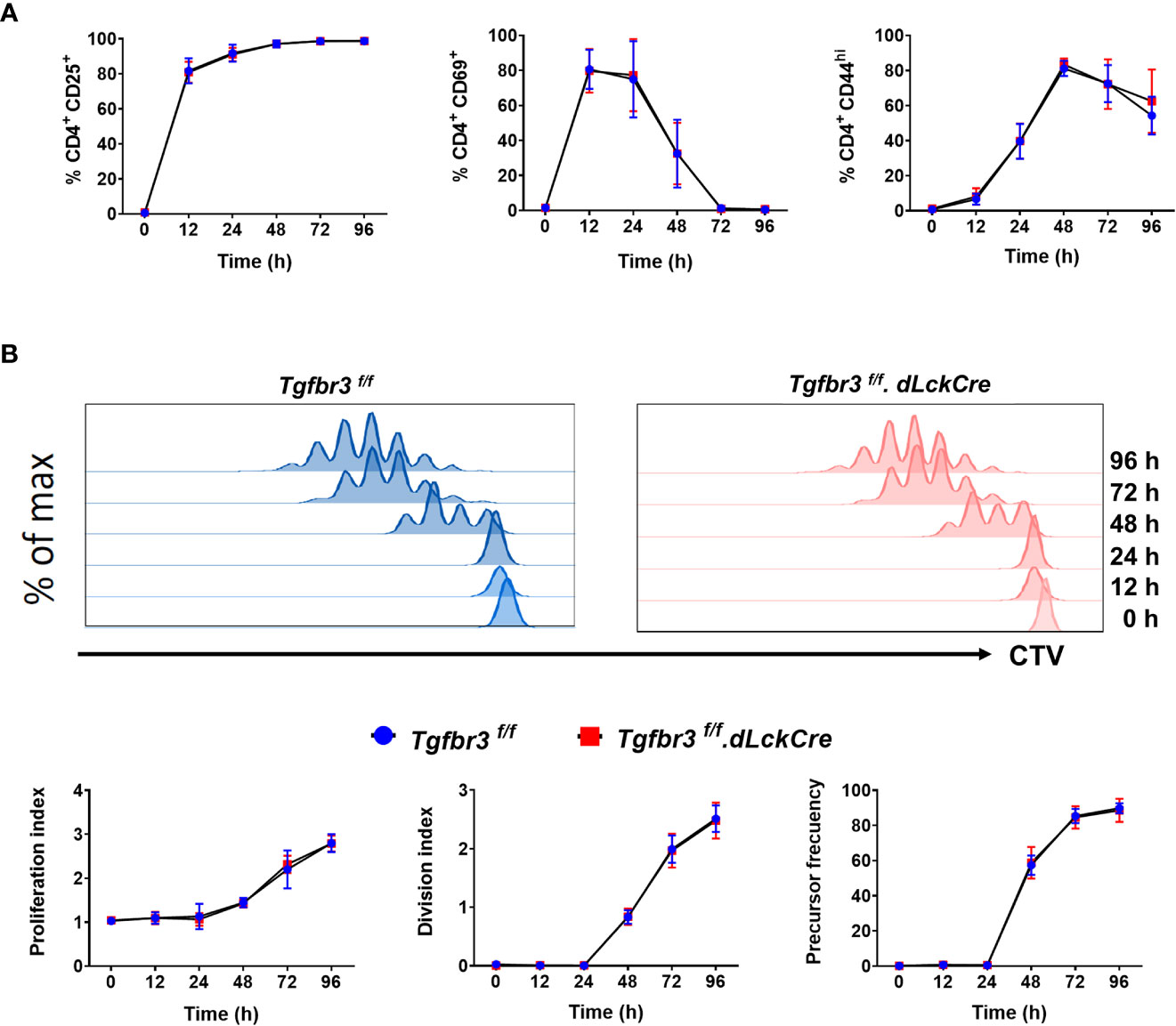

Naïve T cells (CD4+ CD25- CD44lo CD62Lhi) from spleen and peripheral lymph nodes were sorted on the MoFlow FACS sorter and stained with Cell Trace Violet (CTV) following manufacturer’s instructions. 5x104 CTV+ cells per well were cultured in a 96-well plate with Dynabeads® Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Invitrogen) at a 2:1 beads/cell ratio and complete RPMI medium for 4 days. Cells were recovered at 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours and stained for the detection of CD4, CD25, CD44, and CD69 and viability. Zombie NIR dye (Biolegend) and antibodies were diluted in PBS and cells were incubated with the mix for 15 min at room temperature, washed, fixed, and acquired in the Attune NxT Cytometer (Thermo Fisher). Data analysis was done using FlowJo X software.

For the proliferation index, division index, and precursor frequency calculations, the number of cells of G0, G1, G2, G3 …. were obtained and the following algorithms were used:

Division index = # of divisions/# of cells at start of culture

Proliferation index = # of divisions/# of cells that went into division

Precursor frequency = (division index/proliferation index) * 100

where:

# of divisions = (G1/2)*1 + (G2/4)*2 + (G3/8)*3 ….

# of cells at the start of culture = G0 + (G1/2) + (G2/4) + (G3/8) ….

# of cells that went into division = (G1/2) + (G2/4) + (G3/8) ….

CD4+ CD25- CD44lo CD62Lhi Naϊve T cells from spleen and peripheral lymph nodes were sorted on the MoFlow FACs sorter and stained with CTV. 5 x104 cells per well were cultured in a 96-well plate for 3 days with Dynabeads® Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Invitrogen) at a 2:1 beads/cell ratio and complete RPMI medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL IL-12 (R&D Systems) and 10 µg/mL anti-IL4 (Biolegend) for Th1 differentiation and 1.5 ng/mL TGF-β1 (Peprotech), 20 ng/mL IL-6 (R&D Systems), 10 ng/mL IL-23 (R&D Systems), 10 µg/mL anti-IL-4 (Biolegend), and 10 µg/mL anti-IFN-γ (Biolegend) for Th17 differentiation. On day 3, cells were restimulated with 50 ng/mL PMA and 500 ng/mL ionomycin and treated with 5 µg/mL brefeldin A (GolgiPlug™, BD) for 5 hours at 37°C. Surface staining with viability dye and anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 was performed at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with 100 μL of Foxp3/Transcription Factor Fix/Perm Solution (Tonbo) for 1 hour at room temperature. After permeabilization, Fc receptors were blocked with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Biolegend) for 20 min at room temperature. Intracellular staining with anti-IFNγ and anti-IL-17A was performed for 30 min at room temperature. Th1 and Th17 polarized cells were identified as CD4+ IFN-γ+ and CD4+IL-17A+, respectively, and samples were acquired in an Attune NxT cytometer (Thermo Fisher) and analyzed with FlowJo X software (BD, San Jose, CA).

Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre mice (n=9) and Tgfbr3fl/fl.mice (n=8) were immunized with 150 μg of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 35-55 peptide (MOG35-55, GL Biochem Ltd.) emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant containing 500 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (BD). Ten days following immunization, cells from spleen and peripheral lymph nodes of Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl.mice were obtained. After RBC lysis, 5x106 cells from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre mice and Tgfbr3fl/fl. mice were cultured in a 48-well plate with 10 μg/mL MOG35-55 under either Th1 or Th17 polarizing conditions. Th1 polarizing conditions consisted of 10 ng/mL IL-12 (Biolegend) and 0.5 μg/mL anti-IL-4 (Biolegend) in IMDM complete culture media. Th17 polarizing conditions consisted of 20 ng/mL IL-6 (Tonbo Biosciences), 20 ng/mL IL-23 (Biolegend), 1 ng/mL TGF-β1 (Tonbo Biosciences), 10 μg/mL anti-IFN-γ (Biolegend), and 0.5 μg/mL anti-IL-4 (Biolegend) in IMDM complete culture media. After 3 days, 50 ng/mL of PMA (Biolegend), 500 ng/mL of ionomycin (Biolegend), and 5 μg/mL of brefeldin A (Biolegend) were added to each well and cells were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C (29). Cells were stained with Zombie NIR (Biolegend) followed by surface staining with anti-CD4 BV650 (Biolegend) and anti-CD5 PE (Biolegend). Permeabilization and intracellular staining with anti-IFN-γ APC (Biolegend) and anti-IL-17A AF488 (Biolegend) antibodies was then performed. Samples were acquired with an Attune Nxt flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher) and analyzed with FlowJo X software (BD).

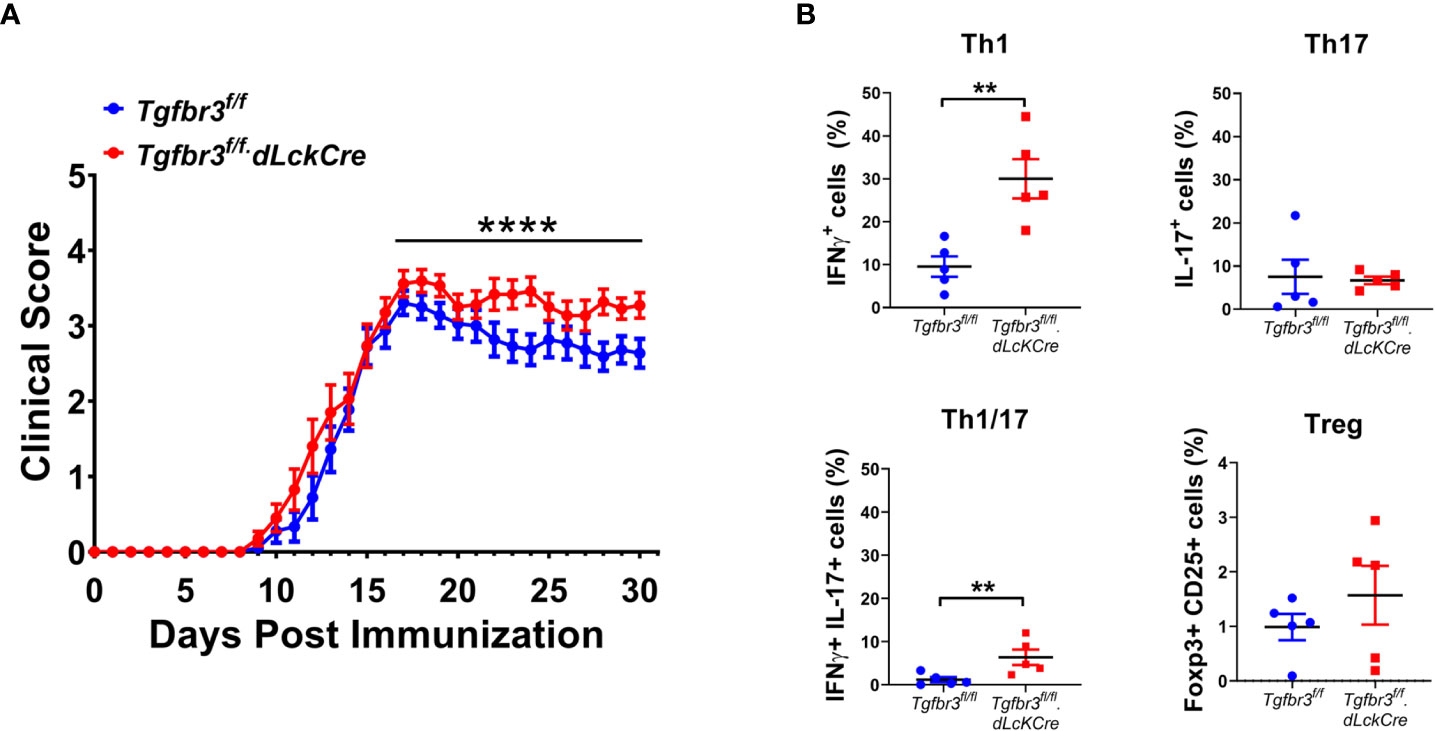

Active EAE model was induced as previously described (30). Briefly, mice were immunized with 150 μg of MOG35-55 (GL Biochem Ltd.) emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant containing 500 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (BD). Mice also received an intraperitoneal injection of 200 ng pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, INC.) immediately following immunization, as well as 2 days after immunization. Mice were scored daily to assess clinical symptoms of EAE for 30 days. The EAE scoring system ranges from a score of 0 to 6, as described below, with higher scores representing increased paralysis and disease severity (31).

The onset of disease presents with a partial loss of tail tone scored as a “1”. The disease progresses to a “2” when the tail is completely flaccid and does not respond to stimulation. A score of “3” is accompanied by the paralysis of one hind limb, but not both. A score of “4” is ascribed for complete paralysis of both hind limbs, but the ability to maneuver around the cage and access food and water using the fore limbs. Once a mouse does not have the ability to access food and water, or they have lost over 20% of their baseline body weight, the mouse is scored as a “5” and humanely euthanized. If a mouse is found dead in its enclosure, it is scored as a “6”. If a mouse dies during the observation period, or is euthanized, it is removed from analysis the day after death/euthanization.

For passive induction of EAE, MOG35-55 reactive Th1 or Th17 cells were prepared as described previously (32, 33). Briefly, donor Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice were immunized with 150 µg MOG35-55 in complete Freund’s adjuvant containing 500 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (BD). Ten days following immunization, cells from peripheral lymph nodes and spleen were restimulated with 10 μg/mL MOG35-55 under either Th1 or Th17 polarizing conditions for 3 days. Th1 polarizing conditions consisted of 10 ng/mL IL-12 (Biolegend) and 0.5 μg/mL anti-IL-4 (Biolegend) in IMDM complete culture media. Th17 polarizing conditions consisted of 20 ng/mL IL-6 (Tonbo Biosciences), 20 ng/mL IL-23 (Biolegend), 1 ng/mL TGF-β1 (Tonbo Biosciences), 10 μg/mL anti-IFN-γ (Biolegend), and 0.5 μg/mL anti-IL-4 (Biolegend) in IMDM complete culture media. The differentiated cells were harvested, pooled, and dead cells were removed using a Ficoll gradient. These cells were used as “donor cells’’. The number of transferred donor cells was normalized based on the percentage of live CD4+ cells; sublethally irradiated (350 rads) naïve mice were injected with 5x106 cells (Th1 or Th17) resuspended in 500 μL of PBS via intravenous tail injections. Recipient mice were also intraperitoneally administered 200 ng of the pertussis toxin same as for active EAE and they were scored daily to assess clinical symptoms of EAE for 30 days, as described above (34–36).

Anti-TNP primary and secondary Ab response was determined by immunizing (primary) mice with 50 µg TNP-KLH (Sigma) in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) followed by boost on day 21 with 50 µg TNP-KLH in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA). Mice were bled at baseline (before immunization), day 7, 14, and 21 after primary immunization, and day 28, 36, and 42 post boost. Levels of anti-TNP in serum were measured by ELISA using anti-TNP-BSA (1:4) as antigen. Responses for IgM, IgG1, IgG2c, and IgG3 anti-TNP were assayed.

A nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was performed from day 15 to day 30, for the in vivo experiments and independent sample t tests were conducted for in vitro assays. Prism (GraphPad) was used to perform the analysis.

To investigate the function of the TβRIII protein in mature T lymphocytes, we bred the Tgfbr3fl/fl mouse with the distal Lck promoter Cre transgenic mice to generate Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice (37, 38). PCR analysis of purified CD4+ T cells from spleen show a prominent 463 bp band, the product after deletion of exon 5, and a faint 583 bp band representing wild type (Figure 1A). In contrast, CD4+ T cell-depleted splenocytes, predominantly containing B cells and CD8+ T cells, presented the wild type (583 bp) and deleted (463 bp) bands, respectively. We next assessed the expression of TβRIII protein on the cell surface of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD19+ B cells from peripheral tissue and blood by flow cytometry. On CD4+ T cells from all peripheral tissues (spleen, LN, MLN, and blood), we detected very little expression of TβRIII on CD4+ T cells fromTgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice compared to Tgfbr3fl/fl controls (Figure 1B and data not shown). The low levels of TβRIII probably represent incomplete deletion that is evident in the PCR results. Although the TβRIII levels on CD8+ T cells from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice were lower than those from Tgfbr3fl/fl mice, its expression was clearly detected as compared to secondary Ab control staining. In the thymus, Tgfbr3fl/fl mice and Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre had equivalent levels of TβRIII on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, an expected result since the dLck promoter becomes active only in mature T cells in the periphery (37). A very small population of B cells express Lck and therefore TβRIII expression was mostly unaltered in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice. Furthermore, B cells express very low levels of TβRIII, as previously reported (17).

Figure 1 Inactivation of TβRIII in peripheral CD4 T cells in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre mice. The TβRIII deletion was assessed by PCR and by flow cytometry on CD4+ T cells. (A) Representative electrophoresis gel for presence of Tgfbr3 5 (583 bp) or its deletion (463 bp) in CD4+ cells or CD4-depleted spleen cells from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl control mice. (B) Representative histograms for TβRIII expression on CD4+, CD8+, and CD19+ cells from spleen and thymus of Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre (red) and Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) control mice, including the secondary antibody control (gray) for each population, median expression is represented next each histogram.

TβRIII is differentially expressed on CD4 and CD8 T cell populations with increased expression on naïve and central memory CD4 T cell subpopulations (17), suggesting that TβRIII may be involved in T cell homeostasis. We did not observe any differences in frequencies or total numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, nor subpopulations of CD4+ T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs or blood (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 1). The total number of cells in spleen (SP) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) was similar in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice, however, in peripheral lymph nodes (LN) there was a slight decrease in total cell numbers, as well as CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cell numbers in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre compared to control Tgfbr3fl/fl mice (Figure 2A). This decrease in LN was primarily within the naïve CD4 and CD8 T cell subsets (Figure 2B).

Figure 2 Evaluation of lymphocyte populations in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice at homeostasis. (A) Scatter plots show the of total number of cells in spleen (SP), peripheral lymph nodes (LN) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre (red) and Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) (upper graphs) and the percentages and absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ populations in the secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral blood from (bottom graphs) of the same mouse strains. (B) Percentage of naïve (CD62Lhi/CD44lo) or memory population (CD62L-/CD44hi) from CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in spleen (SP), peripheral lymph nodes (LN) mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and peripheral blood from Tgfbr3fl/fl dLcKCre (red) and Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) control mice. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. n = 3-4 mice, from 3 independent experiments.

Autoreactive CD4+ T cells initiate the disease in EAE, the mouse model to study MS (34). Molecules that modulate strength of the CD4 T cell response and/or ability to differentiate into pathogenic effector populations such as Th1, Th17 directly impact both the development and severity of EAE disease (24). Thus, this in vivo model is a robust approach to determine to what extent TβRIII impacts CD4 T cell activation and/or differentiation to effector Th cells. We immunized female and male Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice with MOG35-55 and followed the development and progression of EAE over 30 days. We observed that Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice developed EAE with significantly greater severity than Tgfbr3fl/fl mice, with a median clinical score of 3.28 and 2.76, respectively (Figure 3A). Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre showed greater mortality than Tgfbr3fl/fl mice from EAE, however, overall survival as assessed by Kaplan-Meier analysis was not significantly different between the two groups (data not shown). It is important to note that the survival analysis only included mice that died spontaneously and none that were euthanized due to severe disease (more than 20% of loss in body weight or clinical score ≥ 3.5). Disease onset was not different between TβRIII null and controls (Figure 3A).

Figure 3 T cell specific TβRIII null mice develop more severe EAE after immunization with MOG35-55. (A) EAE clinical score of Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre (red, N=20) and Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue, n=18) mice immunized with MOG35-55 peptide in CFA. (B) Th17, Th1, Th17/1 and Treg cells in spinal cord of Tgfbr3fl/fl dLcKCre (red) and Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) mice at peak of disease. Littermate mice were immunized with 150 µg MOG35-55 peptide in CFA and clinical course of disease was determined. Mice with an EAE clinical score above 4 or a drop in weight of over 20%, mice were humanely euthanized. After a mouse was euthanized, it ceased to be scored and was therefore removed from future analysis. In (B) each dot represents an individual mouse. Data is mean ± SEM; Non-parametric t-test for (A) and parametric t-test for (B). **=p<0.01,, ****=p<0.0001.

Th1 and Th17 cells contribute to EAE severity and Treg cells suppress disease (39), therefore we interrogated if increased disease severity in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice is associated with changes in these effector CD4 T cell populations. Mice were euthanized around the peak of disease, and the T cell populations in the spinal cord were analyzed for frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ, IL-17 or CD25 and FoxP3. Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice had a significantly higher proportion of IFN-γ+ (Th1) and IFN-γ/IL-17 double positive cells in the spinal cord compared to Tgfbr3fl/fl mice (Figure 3B). No significant differences were observed between Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice for the proportion of IL-17+ (Th17) (Figure 3B). Although, the total numbers of CD4+ T cells in the spinal cord were not significantly different between Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice, TβRIII null mice had significantly higher numbers of Th1 (IFN-γ+) T cells in the spinal cord compared to controls (Supplementary Figure 3). We also performed an analysis of CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure 3B) and CD8+ T cells (not shown) and found no significant differences in the spinal cord of Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre compared to Tgfbr3fl/fl mice with active EAE.

These results indicate that loss of TβRIII leads to expansion of Th effector cells expressing IFN-γ in vivo. This inference is supported by an independent experiment showing greater anti-trinitrophenyl (TNP) secondary IgG2c and IgG3, but not IgG1 and IgG2b, antibody response following immunization with TNP-KLH (Supplementary Figure 2). Class switch to IgG2c and IgG3 is promoted by IFN-γ expressing CD4 T cells (40).

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the increase in IFN-γ expressing Th cells contributing to the enhanced EAE and perhaps the IFN-γ dependent IgG class switch antibody response observed in TβRIII null mice, we performed a set of functional experiments.

We previously reported that expression of TβRIII on CD4+ T cells is induced upon CD3 and CD28 crosslinking, concomitantly with increased expression of CD25, CD69, and CD44 (17), suggesting that this coreceptor could be functionally relevant for T cell activation and differentiation. Therefore, we stimulated CD4+ T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 and assayed for the induced expression of activation markers including CD25, CD44, and CD69 as a readout for T cell activation. We found no difference in induction and levels of expression of the three activation markers on CD4+ T cells from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice (Figure 4A). In addition, CD3/CD28 co-stimulation induced T cell proliferation measured by CTV dilution was equivalent between TβRIII null and wild type CD4+ T cells at all time-points between 24 to 96 hours of stimulation (Figure 4B). This was the case for proliferation index, division index and precursor frequency.

Figure 4 In vitro activation of CD4+T cells from Tgfbr3fl/fl and Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice. (A) Expression of the activation markers CD25, CD44 and CD69 was analyzed at 0, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h on sorted naïve T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28. (B) Proliferation of naïve T cells from Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) and Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre (red) mice was evaluated by CTV dilution. Histograms from a representative experiment are shown. Data are expressed as proliferation index, division index and precursor frequency for each time point (see methods). Graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 5 independent experiments, 5 mice per group).

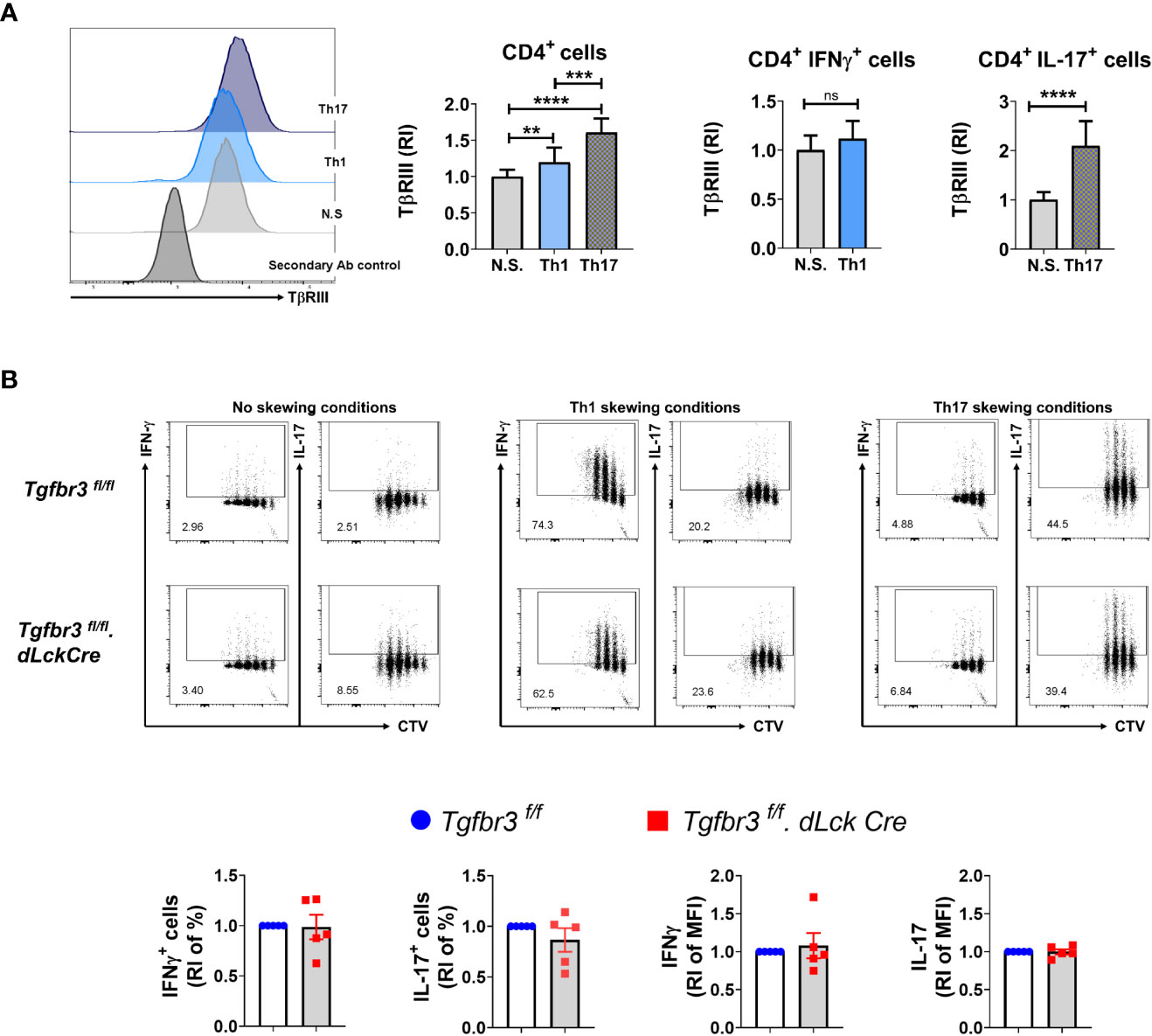

We have previously reported that expression of TβRIII is modulated by T cell activation. Interestingly, TβRIII expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 expression levels during in vitro iTreg differentiation in the presence of TGFβ (17). To determine if TβRIII expression is differentially modulated during polarization of CD4+ T cells into Th1 and Th17 cells, we isolated naïve CD4+ T cells and cultured them under appropriate skewing conditions. We observed that TβRIII expression was higher on CD4+ T cells cultured in either Th1 or Th17 polarizing conditions than non-skewed CD4+ T cells (Figure 5A). Furthermore, expression of TβRIII was greater on Th17 skewed cells compared to Th1 skewed cells. Focusing on only cytokine-expressing cells, we observed that IL-17+ and not IFN-γ+ expression was associated with enhanced upregulation of TβRIII expression. This led us to hypothesize that TβRIII might contribute to Th17 differentiation more than Th1 differentiation. However, in ex vivo Th differentiation cultures, naïve CD4+ T cells from Tgfbr3fl/fl and Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice differentiated similarly under Th1 and Th17 skewing conditions (Figure 5B). There was a trend towards increase in IFN-γ+ cells in TβRIII null T cells, but the difference was not significant. We tested if TβRIII impact on Th differentiation is dependent cell division using CTV dilution assay. Here again we were unable to identify any difference between Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl CD4+ T cells (Figure 5B). Overall, these results indicate that under conventional ex vivo culture conditions, the activation and differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells is not altered by the presence or absence of TβRIII.

Figure 5 TβRIII on Th1 and Th17 cells in vitro differentiated CD4+ T cells. The expression of TβRIII was evaluated on CD4+ T cells under Th1, Th17 and non skewing (N.S) conditions. (A) TβRIII expression on CD4+ T cells under non skewing, Th1 and Th17 conditions. Representative histograms TβRIII expression on Th1, Th17, NS and secondary Ab control (left). Graphs of the increased TβRIII expression relative to non skewing conditions on CD4+, CD4+IFNγ+ and CD4+IL17+ T cells (right). (B) Representative dot plots of IFN-γ+ CTV+ and IL-17+ CTV+ live CD4+T cells following in vitro Th1 and Th17 differentiation from Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre (red) and Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) mice; below are the graphs of IFN-γ or IL-17 increased percentage and median fluorescence relative to non skewing compared to Th1 and Th17 skewing conditions. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. n =5 independent experiments for all conditions ****p<0.0001.

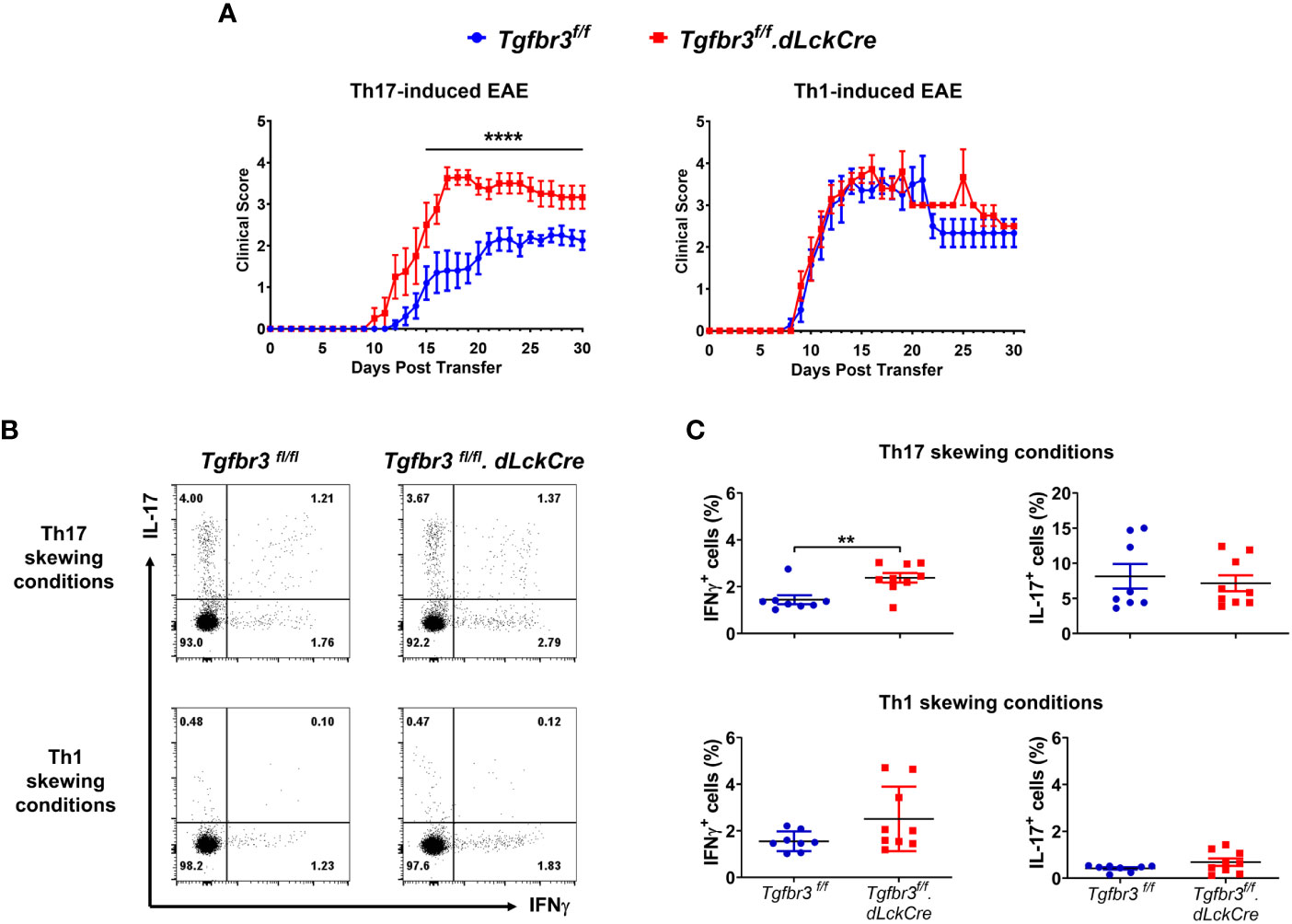

As previously described, independent and overlapping cytokine-mediated mechanisms regulate pathogenicity of encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells in their ability to passively induce EAE in naïve mice (32, 41, 42). Relevant to this, increased severity of EAE in TβRIII null mice was associated with a greater proportion and numbers of IFN-γ expressing Th cells in spinal cords (Figure 3). This led us to predict that TβRIII likely restrains pathogenicity of effector Th cells, particularly Th1 cells. To test for this, we generated encephalitogenic Th17 or Th1 cells by immunizingTgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice or Tgfbr3fl/fl mice, isolated in vivo primed/activated T cells and subsequent ex vivo antigen (MOG35-55) induced expansion in the presence of Th17 or Th1 skewing conditions. These encephalitogenic Th1 or Th17 cells were transferred into naïve mice and progression of EAE was determined. Recipients of TβRIII null Th17 cells developed EAE with earlier onset, beginning day 10, vs controls beginning day 12 (Figure 6A). TβRIII null Th17 cells also induced EAE with much greater severity than controls. There was no mortality in either of the recipient groups. In contrast to Th17 transfers, there was no difference between wild type and TβRIII encephalitogenic Th1 cells to induce EAE and the majority of recipients died within the 30-day time period (Figure 6B). We characterized the encephalitogenic Th17 and Th1 cells that were in vivo primed, and ex vivo restimulated/skewed. We determined that CD4+ T cells from TβRIII null mice skewed under Th17 conditions with MOG35-55 had an expanded proportion of IFN-γ expressing cells but equivalent IL-17+ cells to controls (Figure 6C upper graph). There was no difference between TβRIII null and controls for cells skewed under Th1 conditions (Figure 6C bottom graph). Overall, these data indicate that TβRIII restrains the pathogenicity of encephalitogenic Th17 cells likely by a mechanism regulating the transition to IFN-γ expressing Th cells.

Figure 6 TβRIII regulates the ability of encephalitogenic Th17 to induce EAE. Encephalitogenic Th17 or Th1 cells were generated from Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) or Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre (red) donor mice and transferred to naïve Tgfbr3fl/fl recipients. (A) Clinical scores of passive EAE after transfer of encephalitogenic Th17 and Th1 T cells from both strains into naïve wild-type recipients. The data is expressed as mean ± SEM. For Th17 transfer experiments: TβRIII control (n=10) and TβRIII null (n=8). For Th1 transfer experiments: TβRIII control (n=7) and TβRIII null (n=7). Non parametric ****p ≤ 0.0001. (B, C) Frequency of IL-17 and IFN-γ expressing Th cells in Th17 skewed or Th1 skewed cultures of T cells from MOG35-55 peptide immunized Tgfbr3fl/fl or Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre mice. (B) Representative dot plots (left) and scatter plots (right). Each dot in the scatter plot represents an individual mouse and data is mean ± SEM. Parametric student t-test **p ≤ 0.01.

TβRIII is expressed on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at all stages of development, however its role in these populations has been elusive. Our group previously demonstrated from experiments in fetal thymic organ cultures that TβRIII plays a protective role in thymocyte survival. Furthermore, we showed that the expression of the coreceptor is upregulated upon T cell activation and therefore we hypothesized that TβRIII modulates processes downstream of TCR signaling. However, the ability to examine the function of TβRIII has been a challenge, as this coreceptor plays a key role in several developmental processes during fetal life such that its developmental knockout results in neonatal mortality (5). To overcome this limitation, we generated a Tgfbr3fl/fl mouse and bred it with the dLck.Cre mouse for conditional deletion of TβRIII in mature T cells (37). We confirmed that Cre-mediated deletion was very effective by PCR analysis of genomic DNA for Cre-mediated deletion of Tgfbr3 exon 5. In CD4+ T depleted spleen cells, two bands were observed: the lower band likely corresponds to CD8+ T cells (delete exon 5), and the upper band attributable to B cells (wild type band). CD4+ T cells were not further segregated into subpopulations since they all express high levels of TβRIII (17).

Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that TβRIII expression was selectively abrogated in CD4+ T cells (Figure 1B) and moderately on CD8+T cells, but not in thymic CD4+ T cells and CD19+ B cells, as the Lck distal promoter is selectively active in late mature T cells. Tgfbr3 exon 5 deletion did not result in complete protein ablation, and although we cannot exclude that the remaining expression of TβRIII is functional, its dramatic decrease in expression observed in Tgfbr3f/f.dLckCre mice was sufficient to increase the severity of EAE induced by active immunization with MOG35-55 peptide or by passive immunization with encephalitogenic Th17 cells.

Although we did not find significant differences in the proportion of T cell subsets between Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre and Tgfbr3fl/fl mice, there was a trend towards a decrease in LN CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers, which was not present in spleen and MLN, suggesting a possible LN-specific homing defect. Consistent with our previous report, TβRIII was differentially expressed between subpopulations of T cells, with greater levels on CD4+ compared to CD8+ T cells (17). This is especially relevant given that this receptor modulates cell migration and metastasis in different cancer type cells (3). We have previously shown that TβRIII is upregulated upon TCR crosslinking in concomitantly to other activation markers, such as CD69, CD25 and CD44 (17). Therefore, we speculated that this coreceptor might be involved in T cell activation. However, we found that under non-skewing conditions, T cell activation was not significantly affected by the absence of TβRIII.

Given the role of TβRIII in the modulation of TGFβ signaling (43) and our recent report showing that the expression of TβRIII is decreases with increase in Foxp3 expression during induced-Treg (iTreg) culture conditions (17), we predicted that this correceptor may modulate differentiation of naive CD4 T cells to Th17 and/or Th1 effector cells. The differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells following under appropriate polarizing conditions induced greatly elevated expression of TβRIII on Th17 cells, at levels greater than that on Th1 cells. However, the loss of TβRIII had no effect on the ability of naive T cells to differentiate into Th1 and Th17 under in vitro polarizing conditions. It is important to appreciate that TβRIII interacts with several different molecules; these include activins, inhibins, bone morphogenic proteins, in addition to TGFβs (1). The in vitro culture conditions do not replicate any of these interactions and therefore does exclude the possibility that TβRIII plays a role in Th1 and Th17 functional activities in vivo. In autoimmune diseases, including MS and its mouse model EAE, the importance of Th1 and Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of disease is well established (32). We found that TβRIII null mice developed more severe EAE than littermate controls. The severity of EAE was associated with an expanded proportion of Th1 and Th17/1 (IFN-γ+IL-17+) cells but not Th17 cells. The Th17/1 cells represent Th17 cells undergoing transition from Th17 to Th1, a process defined as plasticity (44). We and others have shown that these Th17/1 cells likely contribute more to pathogenicity in MS and EAE (45–47). The expanded Th1 cells in the spinal cord of TβRIII null mice may represent a function of TβRIII to restrict the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th1 cells. This concept is supported by the observation that class switch of antibody to IFNγ-dependent isotypes (IgG2c and IgG3) was significantly greater in TβRIII null mice, although it was moderately observed for IgG1 and IgG2b.

Passive transfer of in vivo generated, ex vivo expanded encephalitogenic Th17 cells from TβRIII null mice induced significantly greater EAE than controls. The enhanced disease was not due to differences in numbers of transferred Th17 cells, but there was a small but significantly greater number of IFN-γ expressing cells generated from TβRIII null donors under Th17 conditions. It is unlikely that the increased pathogenicity is merely due to the presence of IFN-γ expressing Th cells as we did not observe any difference for Th1 transfers between TβRIII null and controls. This indicates to us that in the absence of TβRIII, T cells receiving Th17 environmental cues are more pathogenic. It is well appreciated that specific cues can shift the pathogenicity balance of Th17 cells (44, 48, 49).

The original view of the function of TβRIII as merely an accessory coreceptor for augmenting signals from TβRII-TβRII heterodimer needs to be reevaluated. TβRI or TβRII deficiency in CD4 cells results in the development of spontaneous autoimmunity in mice (18–20). If the main role of TβRIII is to function as a co-receptor for TβRI and TβRII, we would expect mice lacking TβRIII on CD4+ T cells to also exhibit spontaneous autoimmunity and death. However, we have studied theTgfbr3fl/fl.CD4Cre mouse, which lacks TβRIII in all CD4+ T cells, and this mouse does not develop spontaneous autoimmunity up to 18 months of age, data not shown. Additionally, when we crossed this mouse with a dLckCre mouse to generate a Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mouse, which deletes TβRIII on mature T cells, no hyperactivation was observed as reported for TβRII null mice generated in a similar (38).

Results showed that TβRIII in T cells functions to restrict the development of pathogenic effector cells necessary for disease progression and severity in MOG35-55 immunization induced active EAE disease. This is evident by the fact that Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice developed significantly more severe EAE than Tgfbr3fl/fl mice by both immunization with MOG35-55 and induction via the passive transfer of Th17 polarized T cells. The increase in disease severity in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice was also associated with an increased number and proportion of IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells present in the spinal cord. However, there was no difference in IL-17 positive cells in the spinal cord of mice with EAE.

The passive transfer of Th1 polarized cells, regardless of the presence of TβRIII on T cells, resulted in rapid onset of severe disease and high mortality. This high level of mortality and disease was present despite the relatively low level of pathogenic T cell populations seen in culture prior to transfer compared to Th17 transfers. Additionally, the same level of sub-lethal radiation was applied to both Th1 and Th17 recipients and there was no mortality observed in Th17 transfer recipients. This may suggest a high level of pathogenic expansion in the Th1 passive transfer recipient mice regardless of the presence of TβRIII (50). The in vitro MOG restimulation/polarization data also suggests that TβRIII has no effect on the ability of naïve T cells to polarize towards Th1. Although the possibility cannot be excluded entirely, EAE induced by passive transfer of encephalitogenic Th1 cells from TβRIII sufficient and TβRIII null mice were indistinguishable even when the numbers of T cells transferred were reduced to as low as 2x106 cells (data not shown). This indicates to us that the role of TβRIII in Th1 generation and/or pathogenicity may be subtle or needs to be addressed with other disease models.

The passive transfer Th17 EAE experiments showed that naïve recipient mice developed more severe disease after being injected with MOG-specific CD4+ T cells lacking TβRIII which had undergone Th17 polarization. However, investigation of these cells prior to transfer suggests that the primary cytokine produced by Th17 cells, IL-17, is likely not responsible for the difference in disease. The percentage of IL-17 producing cells was no different in cells lacking TβRIII and wild type in Th17 polarized MOG-restimulated cultures. Instead, MOG-specific CD4+ T cells lacking TβRIII which had undergone Th17 polarization produced a significantly higher proportion of the cytokine IFN-γ than cells from donor wild type mice. This supports our data showing increased IFN-γ expressing cells in the spinal cord of mice with active EAE.

These results suggest that MOG restimulated Th17 polarized CD4+ T cells lacking TβRIII may have undergone what is known as plasticity. Th17 cells with appropriate cytokine signals, such as IL-23 and IL-12 can transdifferentiate into IFN-γ producing Th1 cells (51). During conversion, the IL-17 expressing CD4+ T cells go through an intermediate stage expressing both IFN-γ and IL-17; in fact, it was observed that TβRIII null EAE mice had a greater proportion of the double cytokine producing cells than TβRIII sufficient mice [31]. Th1 cells generated from Th17 cells are also defined as ex-Th17 cells (27, 52, 53). Other effector populations such as Th1 and Th2 cells are fixed in their lineage and are thought to be unable to undergo this process of change to other effector cell populations (27). When Th17 cells begin to downregulate the expression of the master regulator RORγt and begin to upregulate the master regulator T-bet, they begin to take on the profile of Th1 cells and produce IFN-γ. The transdifferentiation of Th17 to Th1 cells is important for normal immune system function, such as promoting anti-tumor growth (54). However, there is evidence that suggests Th17 cells that transdifferentiate into Th1 cells can be particularly pathogenic. For example, the so-called ex-Th17 cells that produce IFN-γ are thought to be the main drivers of intestinal pathology in humans with inflammatory bowel disease and colitis (55, 56). Additionally, evidence suggests that ex-Th17 cells produce higher levels of cytokines than classical Th1 or Th17 cells and are also resistant to Treg suppression of proliferation and cytokine production (53).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the "Comité Interno para el Cuidado y Uso de Animales de Laboratorio, (CICUAL), Protocol #176 at the Biomedical Research Institute, UNAM, and the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

GS and CR contributed to conception and design of the study. SOF, ROA, and SJD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SOF, SJD, CMS, NAD, SMO, MSL, RC, PDS, NY, and ASL performed the experiments. SOF, ROA, and SJD organized the database and analyzed data. GS and CR wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by a Grant from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico DGAPA PAPIIT IN213319. CR was supported from NIH Grants R21 MD015319, R21 AI107748. UAB Flow Cytometry and Single Cell Core Facility was supported by AI027767 and CA013148.

We would like to thank the UAB mouse facility and the National Laboratory of Flow cytometry for technical assistance, especially to MsC Anaí Fuentes and QFB Carlos Castellanos for FACS sorting of samples. We also would like to thank MVZ Oscar Hernández Campos technical support in typing of mice.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1088039/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Gating strategy for the evaluation of lymphocyte populations in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice. CD4+ T cell subsets analysis was performed using the singlet cells, lymphocyte live cells (live and dead blue negative) gating. Then, cells were further gated for CD4+ and CD8+ and Naive Vs Memory subsets were evaluated using CD62L Vs CD44 markers. Finally, CCR7 analysis was performed from naive and memory subsets. CCR7 positive gate was adjusted based on the FMO controls of each subpopulation.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Class switch to IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c and IgG3 antibody secondary response in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLckCre mice. Graphs of anti-trinitrophenyl (TNP) secondary IgM, IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c and IgG3, antibody response following immunization with TNP-KLH in Tgfbr3fl/fl.dLcKCre (red) or Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) littermate control mice. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001 (n =4).

Supplementary Figure 3 | Absolute numbers of Th cells infiltrating the spinal cord in EAE model. Th1, Th17, Th1/17 cells in the spinal cord of Tgfbr3fl/fl dLcKCre (red) and Tgfbr3fl/fl (blue) mice at peak of disease. Data represent mean ± SEM; *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. (n = 5 mice for each strain).

1. Bilandzic M, Stenvers KL. Betaglycan: A multifunctional accessory. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2011) 339(1-2):180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.014

2. Mythreye K, Blobe GC. The type III TGFbeta receptor regulates directional migration: new tricks for an old dog. Cell Cycle (Georgetown Tex) (2009) 8(19):3069–70. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.19.9419

3. Gatza CE, Oh SY, Blobe GC. Roles for the type III TGF-beta receptor in human cancer. Cell signal (2010) 22(8):1163–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.016

4. Olivey HE, Barnett JV, Ridley BD. Expression of the type III TGFbeta receptor during chick organogenesis. Anat Rec Part A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol (2003) 272(1):383–7. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10049

5. Stenvers KL, Tursky ML, Harder KW, Kountouri N, Amatayakul-Chantler S, Grail D, et al. Heart and liver defects and reduced transforming growth factor beta2 sensitivity in transforming growth factor beta type III receptor-deficient embryos. Mol Cell Biol (2003) 23(12):4371–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4371-4385.2003

6. Pawlak JB, Blobe GC. TGF-β superfamily co-receptors in cancer. Dev Dynamics (2022) 251(1):137–63. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.338

7. Cook LM, Frieling JS, Nerlakanti N, McGuire JJ, Stewart PA, Burger KL, et al. Betaglycan drives the mesenchymal stromal cell osteogenic program and prostate cancer-induced osteogenesis. Oncogene (2019) 38(44):6959–69. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0913-4

8. Hempel N, How T, Dong M, Murphy SK, Fields TA, Blobe GC. Loss of betaglycan expression in ovarian cancer: Role in motility and invasion. Cancer Res (2007) 67(11):5231–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0035

9. Ajiboye S, Sissung TM, Sharifi N, Figg WD. More than an accessory: Implications of type III transforming growth factor-beta receptor loss in prostate cancer. BJU Int (2010) 105(7):913–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08999.x

10. Dong M, How T, Kirkbride KC, Gordon KJ, Lee JD, Hempel N, et al. The type III TGF-beta receptor suppresses breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest (2007) 117(1):206–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI29293

11. Mythreye K, Blobe GC. Proteoglycan signaling co-receptors: Roles in cell adhesion, migration and invasion. Cell signal (2009) 21(11):1548–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.05.001

12. Velasco-Loyden G, Arribas J, López-Casillas F. The shedding of betaglycan is regulated by pervanadate and mediated by membrane type matrix metalloprotease-1. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(9):7721–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306499200

13. Li MO, Flavell RA. TGF-beta: A master of all T cell trades. Cell (2008) 134(3):392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.025

14. Licona-Limón P, Alemán-Muench G, Chimal-Monroy J, Macías-Silva M, García-Zepeda EA, Matzuk MM, et al. Activins and inhibins: Novel regulators of thymocyte development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2009) 381(2):229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.029

15. Yoshioka Y, Ono M, Osaki M, Konishi I, Sakaguchi S. Differential effects of inhibition of bone morphogenic protein (BMP) signalling on T-cell activation and differentiation. Eur J Immunol (2012) 42(3):749–59. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141702

16. Aleman-Muench GR, Mendoza V, Stenvers K, Garcia-Zepeda EA, Lopez-Casillas F, Raman C, et al. Betaglycan (TβRIII) is expressed in the thymus and regulates T cell development by protecting thymocytes from apoptosis. PloS One (2012) 7(8):e44217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044217

17. Ortega-Francisco S, de la Fuente-Granada M, Alvarez Salazar EK, Bolaños-Castro LA, Fonseca-Camarillo G, Olguin-Alor R, et al. TβRIII is induced by TCR signaling and downregulated in FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2017) 494(1-2):82–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.081

18. Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature (1992) 359(6397):693–9. doi: 10.1038/359693a0

19. Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Abrogation of TGFbeta signaling in T cells leads to spontaneous T cell differentiation and autoimmune disease. Immunity (2000) 12(2):171–81. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80170-3

20. Steinman L, Zamvil SS. Virtues and pitfalls of EAE for the development of therapies for multiple sclerosis. Trends Immunol (2005) 26(11):565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.014

21. Marie JC, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-beta receptor. Immunity (2006) 25(3):441–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.012

22. Steinman L. A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat Med (2007) 13(2):139–45. doi: 10.1038/nm1551

23. Gaublomme JT, Yosef N, Lee Y, Gertner RS, Yang LV, Wu C, et al. Single-cell genomics unveils critical regulators of Th17 cell pathogenicity. Cell (2015) 163(6):1400–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.009

24. Leung S, Liu X, Fang L, Chen X, Guo T, Zhang J. The cytokine milieu in the interplay of pathogenic Th1/Th17 cells and regulatory T cells in autoimmune disease. Cell Mol Immunol (2010) 7(3):182–9. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.22

25. Oh SA, Li MO. TGF-β: guardian of T cell function. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2013) 191(8):3973–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301843

26. Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, Oliver JR, Chen D, Elson CO, et al. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity (2009) 30(1):92–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005

27. Muranski P, Restifo NP. Essentials of Th17 cell commitment and plasticity. Blood (2013) 121(13):2402–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-378653

28. Bending D, Newland S, Krejcí A, Phillips JM, Bray S, Cooke A. Epigenetic changes at Il12rb2 and Tbx21 in relation to plasticity behavior of Th17 cells. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2011) 186(6):3373–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003216

29. Flaherty S, Reynolds JM. Mouse naïve CD4+ T cell isolation and in vitro differentiation into T cell subsets. J vis exp (2015) (98):52739. doi: 10.3791/52739

30. Bittner S, Afzali AM, Wiendl H, Meuth SG. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35-55) induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in C57BL/6 mice. J Vis Exp (2014) (86):51275. doi: 10.3791/51275

31. De Sarno P, Axtell RC, Raman C, Roth KA, Alessi DR, Jope RS. Lithium prevents and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2008) 181(1):338–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.338

32. Axtell RC, de Jong BA, Boniface K, van der Voort LF, Bhat R, De Sarno P, et al. T Helper type 1 and 17 cells determine efficacy of interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis and experimental encephalomyelitis. Nat Med (2010) 16(4):406–12. doi: 10.1038/nm.2110

33. Sestero CM, McGuire DJ, De Sarno P, Brantley EC, Soldevila G, Axtell RC, et al. CD5-dependent CK2 activation pathway regulates threshold for T cell anergy. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2012) 189(6):2918–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200065

34. McCarthy DP, Richards MH, Miller SD. Mouse models of multiple sclerosis: experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and theiler's virus-induced demyelinating disease. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton NJ). (2012) 900:381–401. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-720-4_19

35. Larabee CM, Hu Y, Desai S, Georgescu C, Wren JD, Axtell RC, et al. Myelin-specific Th17 cells induce severe relapsing optic neuritis with irreversible loss of retinal ganglion cells in C57BL/6 mice. Mol vision (2016) 22:332–41.

36. Lazarski CA, Ford J, Katzman SD, Rosenberg AF, Fowell DJ. IL-4 attenuates Th1-associated chemokine expression and Th1 trafficking to inflamed tissues and limits pathogen clearance. PloS One (2013) 8(8):e71949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071949

37. Zhang DJ, Wang Q, Wei J, Baimukanova G, Buchholz F, Stewart AF, et al. Selective expression of the cre recombinase in late-stage thymocytes using the distal promoter of the lck gene. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2005) 174(11):6725–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6725

38. Zhang N, Bevan MJ. TGF-β signaling to T cells inhibits autoimmunity during lymphopenia-driven proliferation. Nat Immunol (2012) 13(7):667–73. doi: 10.1038/ni.2319

39. Esposito M, Ruffini F, Bergami A, Garzetti L, Borsellino G, Battistini L, et al. IL-17- and IFN-γ-secreting Foxp3+ T cells infiltrate the target tissue in experimental autoimmunity. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2010) 185(12):7467–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001519

40. Barr TA, Brown S, Mastroeni P, Gray D. B cell intrinsic MyD88 signals drive IFN-gamma production from T cells and control switching to IgG2c. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2009) 183(2):1005–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803706

41. Naves R, Singh SP, Cashman KS, Rowse AL, Axtell RC, Steinman L, et al. The interdependent, overlapping, and differential roles of type I and II IFNs in the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2013) 191(6):2967–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300419

42. Rowse AL, Naves R, Cashman KS, McGuire DJ, Mbana T, Raman C, et al. Lithium controls central nervous system autoimmunity through modulation of IFN-γ signaling. PloS One (2012) 7(12):e52658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052658

43. López-Casillas F, Payne HM, Andres JL, Massagué J. Betaglycan can act as a dual modulator of TGF-beta access to signaling receptors: mapping of ligand binding and GAG attachment sites. J Cell Biol (1994) 124(4):557–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.557

44. Wu C, Yosef N, Thalhamer T, Zhu C, Xiao S, Kishi Y, et al. Induction of pathogenic TH17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature (2013) 496(7446):513–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11984

45. Axtell RC, Xu L, Barnum SR, Raman C. CD5-CK2 binding/activation-deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: protection is associated with diminished populations of IL-17-expressing T cells in the central nervous system. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2006) 177(12):8542–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8542

46. Stockinger B, Veldhoen M, Martin B. Th17 T cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity. Semin Immunol (2007) 19(6):353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.008

47. Bettelli E, Sullivan B, Szabo SJ, Sobel RA, Glimcher LH, Kuchroo VK. Loss of T-bet, but not STAT1, prevents the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med (2004) 200(1):79–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031819

48. Poholek CH, Raphael I, Wu D, Revu S, Rittenhouse N, Uche UU, et al. Noncanonical STAT3 activity sustains pathogenic Th17 proliferation and cytokine response to antigen. J Exp Med (2020) 217(10):e20191761. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191761

49. Xu H, Agalioti T, Zhao J, Steglich B, Wahib R, Vesely MCA, et al. The induction and function of the anti-inflammatory fate of T(H)17 cells. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):3334. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17097-5

50. O'Connor RA, Prendergast CT, Sabatos CA, Lau CW, Leech MD, Wraith DC, et al. Cutting edge: Th1 cells facilitate the entry of Th17 cells to the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2008) 181(6):3750–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3750

51. Kamali AN, Noorbakhsh SM, Hamedifar H, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Yazdani R, Bautista JM, et al. A role for Th1-like Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders. Mol Immunol (2019) 105:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.11.015

52. Loos J, Schmaul S, Noll TM, Paterka M, Schillner M, Löffel JT, et al. Functional characteristics of Th1, Th17, and ex-Th17 cells in EAE revealed by intravital two-photon microscopy. J neuroinflamm (2020) 17(1):357. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02021-x

53. Basdeo SA, Cluxton D, Sulaimani J, Moran B, Canavan M, Orr C, et al. Ex-Th17 (Nonclassical Th1) cells are functionally distinct from classical Th1 and Th17 cells and are not constrained by regulatory T cells. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2017) 198(6):2249–59. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600737

54. Guéry L, Hugues S. Th17 cell plasticity and functions in cancer immunity. BioMed Res Int (2015) 2015:314620. doi: 10.1155/2015/314620

55. Stockinger B, Omenetti S. The dichotomous nature of T helper 17 cells. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17(9):535–44. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.50

Keywords: autoimmunity, EAE, pathogenic Th17, Th1, IFN-g, polarization

Citation: Duesman SJ, Ortega-Francisco S, Olguin-Alor R, Acevedo-Dominguez NA, Sestero CM, Chellappan R, De Sarno P, Yusuf N, Salgado-Lopez A, Segundo-Liberato M, de Oca-Lagunas SM, Raman C and Soldevila G (2023) Transforming growth factor receptor III (Betaglycan) regulates the generation of pathogenic Th17 cells in EAE. Front. Immunol. 14:1088039. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1088039

Received: 02 November 2022; Accepted: 23 January 2023;

Published: 06 February 2023.

Edited by:

Abdelhadi Saoudi, U1043 Centre de Physiopathologie de Toulouse Purpan (INSERM), FranceReviewed by:

Lennart T. Mars, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), FranceCopyright © 2023 Duesman, Ortega-Francisco, Olguin-Alor, Acevedo-Dominguez, Sestero, Chellappan, De Sarno, Yusuf, Salgado-Lopez, Segundo-Liberato, de Oca-Lagunas, Raman and Soldevila. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chander Raman, Y2hhbmRlcnJhbWFuQHVhYm1jLmVkdQ==; Gloria Soldevila, c29sZGV2aUB1bmFtLm14

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.