94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol., 02 June 2022

Sec. Comparative Immunology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.905899

This article is part of the Research TopicInsect immunity and its interactions with microorganisms and parasitoidsView all 31 articles

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are an emerging class of regulators that play crucial roles in regulating the strength and duration of innate immunity. However, little is known about the regulation of Drosophila innate immunity-related lncRNAs. In this study, we first revealed that overexpression of lncRNA-CR33942 could strengthen the expression of the Imd pathway antimicrobial peptide (AMP) genes Diptericin (Dpt) and Attacin-A (AttA) after infection, and vice versa. Secondly, RNA-seq analysis of lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies post Gram-negative bacteria infection confirmed that lncRNA-CR33942 positively regulated the Drosophila immune deficiency (Imd) pathway. Mechanistically, we found that lncRNA-CR33942 interacts and enhances the binding of NF-κB transcription factor Relish to Dpt and AttA promoters, thereby facilitating Dpt and AttA expression. Relish could also directly promote lncRNA-CR33942 transcription by binding to its promoter. Finally, rescue experiments and dynamic expression profiling post-infection demonstrated the vital role of the Relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMP regulatory axis in enhancing Imd pathway and maintaining immune homeostasis. Our study elucidates novel mechanistic insights into the role of lncRNA-CR33942 in activating Drosophila Imd pathway and the complex regulatory interaction during the innate immune response of animals.

Innate immunity plays the first and foremost role in the defense against pathogenic microorganisms (1). Drosophila melanogaster is a vital model for studying innate immunity because of the lack of highly specific adaptive immunity (2, 3). The Drosophila innate immune system comprises cellular immunity and humoral immunity which includes the production of many antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) (3, 4). The immune deficiency (Imd) signaling pathway is essential for Gram-negative bacterial invasion (5, 6). Once attacked by Gram-negative bacteria, the Imd pathway is activated and the downstream transcription factor Relish enters the nucleus to initiate the expression of AMPs (7). Although the major molecules of the Imd pathway have been identified, the complexity of immune regulation requires to explore more regulators to understand the immune homeostasis mechanism.

Dysregulation of immune homeostasis remarkably affects Drosophila survival and can lead to death (8, 9). Therefore, the intensity and duration of the immune response must be precisely regulated by many positive and negative regulators. For example, Akirin, Charon, sick, and STING can promote the Imd pathway by regulating the transcription factor Relish (10–13). In addition, some ubiquitin-related enzymes and peptidoglycan recognition proteins can positively regulate the Imd pathway (14–17). In contrast, some immune suppressors can restore immune homeostasis via preventing excessive activation of the Imd pathway (18–22). Our previous studies demonstrated that miR-9a, miR-981, and miR-277 could negatively regulate the Imd pathway by directly inhibiting the expression of Diptericin (Dpt), imd, and Tab2 (23, 24). However, the regulatory mechanisms involved in maintaining immune homeostasis by emerging noncoding RNAs require further study.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of RNAs of over 200 nucleotides that lack an open reading frames coding protein longer than 100 aa (25, 26).. lncRNAs exist widely in organisms, and their abundance is much higher than that of protein-coding RNAs (27). For example, the number of Drosophila lncRNA transcripts reached 42,848, and the number of lncRNA genes was 15,543 (28). To date, several studies have demonstrated that numerous lncRNAs participate in regulating a wide range of Drosophila biological processes, such as bristle formation (29, 30), embryo development (31–36), gonadal cell production (37, 38) and neuromuscular junctions (39, 40). A previous study has shown that lncRNA-VINR can defend against viruses by inducing AMPs (41). In addition, our previous studies demonstrated that lncRNA-CR46018, lncRNA-CR11538 and lncRNA-CR33942 could regulate Drosophila Toll innate immunity by interacting with the transcription factor Dif/Dorsal (42–44). Although some lncRNAs regulating Drosophila antiviral and Toll innate immunity have been discovered, it is largely unknown whether and how lncRNAs regulate the Imd signaling pathway against Gram-negative bacteria.

In this study, we first found that Drosophila lncRNA-CR33942 can promote the Imd signaling pathway using RNA sequencing, and then, we quantified the expression levels of AMPs Dpt and AttA in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies, lncRNA-CR33942 knockdown flies, and lncRNA-CR33942 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies after Escherichia coli infection. Second, using RIP-qPCR, ChIP-qPCR, and dual-luciferase reporter assays, we confirmed that lncRNA-CR33942 interacts with the transcription factor Relish and strengthens the binding between Relish and the promoters of Dpt and AttA, thereby enhancing Dpt and AttA transcription. Third, we verified that the transcription factor Relish could also directly activate the transcription of lncRNA-CR33942 via ChIP and dual-luciferase reporter assays. Finally, the dynamic expression of Dpt, AttA, Relish, and lncRNA-CR33942 in wild-type flies at different time points post-infection indicated the physiological function of this regulatory axis in the Imd immune pathway. In conclusion, our study discovered a novel Relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMP regulatory axis, which plays a vital role in enhancing the immune response and maintaining immune homeostasis.

The flies were raised in a standard corn flour/agar/yeast medium in a 25 ± 1°C incubator with a 12 h light/dark cycle. The fly stocks w1118 (#3605), Tub-Gal80ts; TM2/TM6B (#7019), Tub-Gal4/TM3, Sb1, Ser1 (#5138), lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi (#30509), UAS-FLAG-Rel68 (#55777), and Relish-RNAi (#28943) were purchased from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA). The UAS-lncRNA-CR33942 fly stock was constructed in our laboratory previously (44). To eliminate false positives caused by overexpression, we also constructed lncRNA-CR33942 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies to reduce the overexpression of lncRNA-CR33942. To explore whether Relish regulates the Imd pathway through lncRNA-CR33942, Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies were constructed. To overexpress or knockdown the corresponding gene in flies at a specific time, they were crossed with flies carrying Tub-Gal80ts and incubated at 18°C. The adults were transferred to a 29°C incubator and cultured for over 24 h to overexpress or knockdown the genes.

Sepsis experiments were conducted on adult males aged 3–5 d. The lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing, lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi, lncRNA-CR33942 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing, and control flies were infected with the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli. The infection experiment was performed via Nanoject instrument (Nanoliter, 2010; WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA). The glass capillary with full of E. coli suspension was inserted into the thorax and collecting the flies at the needed times for subsequent experiments. The survival assays post-infection indicate insufficient immune responses (45). The survival rate of ≥ 100 flies/group was monitored for 96-h after infection with Enterobacter cloacae concentrate.

The total RNA of flies with different genotypes and treatments was extracted using RNA isolator total RNA extraction reagent (Vazyme Biotech Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China). And then, cDNA was obtained using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). qPCR was performed using a BIO-RAD CFX Connect real-time PCR system (BIO-RAD, Hercules, California, USA) via AceQ SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China). Our RT-qPCR cycling conditions were: step 1: 95°C for 5 minutes; step 2: 95°C for 10 seconds; step 3: 60°C for 30 seconds, then steps 2 and 3 were cycled for 40 times. The rp49 expression levels were used as the control to normalize other mRNAs. All the primers used for RT-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All experiments were carried out in triplicate, and each biological sample was measured in triplicate by qPCR. The 2-△△Ct method was used for data analysis (14). All qPCR data was showed as the mean ± SEM.

RNA integrity was assessed with the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit for the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, mRNA was purified using poly T oligo-attached magnetic beads and fragmentated to about 370–420 bp. Library fragments were purified, and PCR was performed with index (X) primers and universal PCR primers. The PCR products were purified, and the library quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, index-coded samples were clustered on a cBot cluster generation system using the TruSeq PE cluster kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The reference genome index was built and paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using Hisat2 v2.0.5. FeatureCounts v.1.5.0-p3 enumerated the reads that mapped to each gene. Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 package of R v. 1.20.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Genes with adjusted P < 0.05 were deemed differentially expressed genes (DEGs). And using the clusterProfiler package in R 4.0.3 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) for Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses on the DEGs. The local version of the GSEA tool (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp) was used for GSEA analysis.

The interaction potential between lncRNA-CR33942 and Relish was predicted using RPISeq (RNA/protein interaction prediction tool, http://pridb.gdcb.iastate.edu/RPISeq/) (46), with known the interaction pair roX2 and msl-2 as the positive control.

To explore the effect of Relish on the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter, we obtained the upstream 2-kb promoter sequence of lncRNA-CR33942 from FlyBase (http://flybase.org) and cloned it into the pGL3-Basic plasmid. All the primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The pIEx4-Flag-Rel68, pGL3-Dpt-promoter, and pGL3-AttA-promoter plasmids were shared by Professor Xiaoqiang Yu (47). The pAc-lncRNA-CR33942 plasmid was constructed as described previously (44).

Drosophila S2 cells were grown in a 28°C constant temperature incubator using SFX insect medium (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Transfection was performed using the X-treme gene HP transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, S2 cells were transiently transfected with 200 μL of transfection complex containing 2000 ng plasmids in 6-mm plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) or 50 μL of transfection complex containing 500 ng plasmids in 24-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA).

The detailed process of the RIP experiment followed this protocol (48). Briefly, approximately 3 × 107 S2 cells transfected with Flag-Rel-N were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) and an RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 min on ice. The supernatants were pre-cleared for 1 h at 4°C using protein A agarose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After pre-clearing, anti-Flag-labelled or control anti-IgG antibodies (ABclonal Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Hubei, China) were separately added to the supernatants and the complexes were incubated at 4°C for 8-12 h. The next day, protein A agarose was joined and binding for 2 h. The beads were washed for five times using RIPA buffer. The remaining complexes were eluted using TE buffer with 1% (w/v) SDS. The eluted complexes of Flag-Rel-N and RNA were treated with protease K to separate the protein-bound RNA, and RNA was extracted and quantified using RT-qPCR.

ChIP-seq of Relish was obtained from the ENCODE project (https://www.encodeproject.org/). ChIP-seq peak analysis was performed using the ChIPseeker package in R (49). IGV 2.9.4 was used for peak visualization of ChIP-seq. The promoter sequences of Dpt, AttA, and lncRNA-CR33942 were obtained from FlyBase (http://flybase.org/). In addition, the Relish motif was obtained in this study (50). The promoter sequences of Dpt, AttA, lncRNA-CR33942 and Relish motifs were submitted to MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme) and PROMO (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3/). The RT-qPCR primers were designed based on the predicted binding sites.

ChIP experiments were performed following this paper (23). Briefly, S2 cells transfected with Flag-Rel-N were cross-linked using 1% (v/v) formaldehyde, lysed with RIPA and nuclear lysis buffers, and sonicated to shear to 200–800-bp fragments. ChIP incubation was performed using Dynabeads protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) which was coated with anti-Flag or anti-IgG antibodies (ABclonal Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Hubei, China). After five times washings using different buffers, Flag-Rel-N-bound DNA was eluted and the cross-links between Rel-N and DNA were reversed at 65°C overnight. The eluted DNA fragments were purified for subsequent qPCR analysis. the primers of ChIP-qPCR were listed in Supplementary Table 1. All experiments were carried out in triplicate, and each biological sample was measured in triplicate by qPCR using the AMP promoters.

To investigate the effects on the transcriptional regulation of lncRNA-CR33942, Dpt, and AttA promoters by Relish or lncRNA-CR33942, S2 cells were transfected using 50 μL of transfection complex containing pIEx4-Flag-Rel68, pGL3-Dpt-promoter, pGL3-AttA-promoter or pGL3-lncRNA-CR33942-promoter, pAc-empty or pAc-lncRNA-CR33942, and Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL). pRL plasmids (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) were used for normalization and normalization. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, luciferase activity was measured using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China).

Experimental data were collected from three independent biological replicates and are presented as the mean ± SEM. Significant differences between values under different experimental conditions were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Fly survival analysis was performed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests. Graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism v. 8.3 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and RStudio (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different from the control.

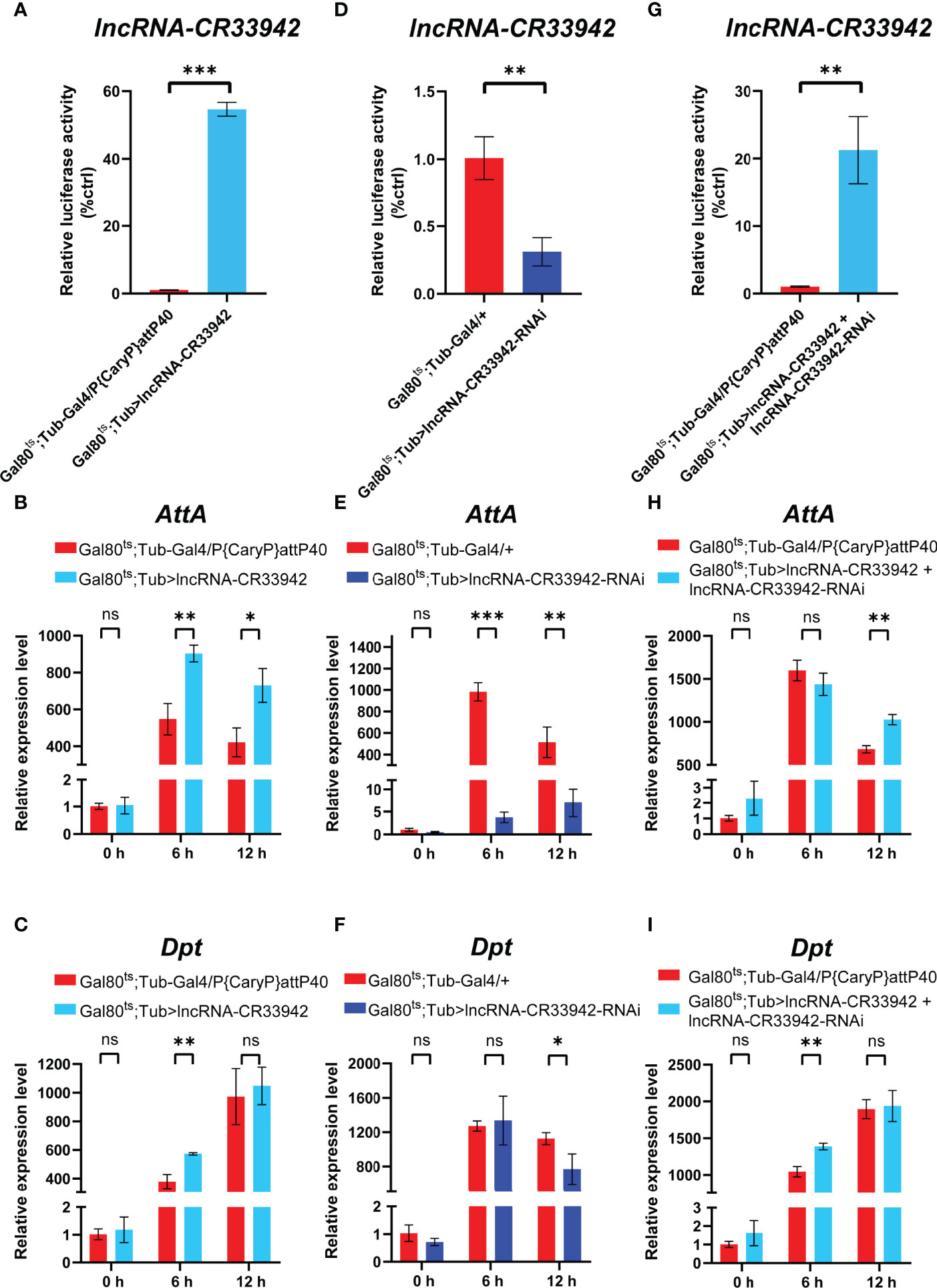

We demonstrated that lncRNA-CR33942 could interact with Dif/Dorsal and facilitate AMP transcription, enhancing Drosophila Toll immune responses (44). Interestingly, lncRNA-CR33942 may also regulate the Imd pathway through our previous RNA-seq in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies infected with Micrococcus luteus. To explore the effect of lncRNA-CR33942 on the Imd pathway, we examined the expression levels of Dpt and AttA, two marker AMPs of the Imd pathway, in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing, lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi, and lncRNA-CR33942 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies at different time points (0, 6, and 12 h) after E. coli infection. Our results showed that the expression of lncRNA-CR33942 in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies was approximately 60 fold than the control flies (Figure 1). Furthermore, the expression of AttA in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies was significantly upregulated compared to that in control flies at 6 and 12 h after E. coli infection, while the expression of Dpt was also significantly increased at 6 h post-infection (Figure 1C). In lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi flies with a 60% decrease in lncRNA-CR33942 expression, AttA expression was dramatically inhibited post-infection, and Dpt expression was also markedly downregulated at 12 h post-infection (Figures 1E, F). Remarkably, the knockdown of lncRNA-CR33942 seemed to block the induction of AttA from infection, and the expression level of AttA declined several hundred times compared to that in the control flies. To exclude the false-positive result of overexpression of lncRNA-CR33942, we constructed lncRNA-CR33942 rescued flies (lncRNA-CR33942 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies) with an approximately 20 fold upregulation of lncRNA-CR33942 expression (Figure 1). The expression of AttA at 12 h post-infection and the expression of Dpt at 6 h post-infection were also significantly enhanced (Figures 1I). However, lncRNA-CR33942 did not influence AMP expression under physiological conditions (0 h). Overall, these results indicate that lncRNA-CR33942 can fine-tune AMP production in response to E. coli invasion, suggesting that it may regulate the Drosophila Imd pathway.

Figure 1 lncRNA-CR33942 regulates Imd pathway AMPs after Escherichia coli infection. The expression levels of lncRNA-CR33942 (A, D, G), AttA (B, E, H) and Dpt (C, F, I) in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies, lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi flies, and lncRNA-CR33942 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies at different time points (0, 6, and 12 h) after E. coli infection. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different from the control.

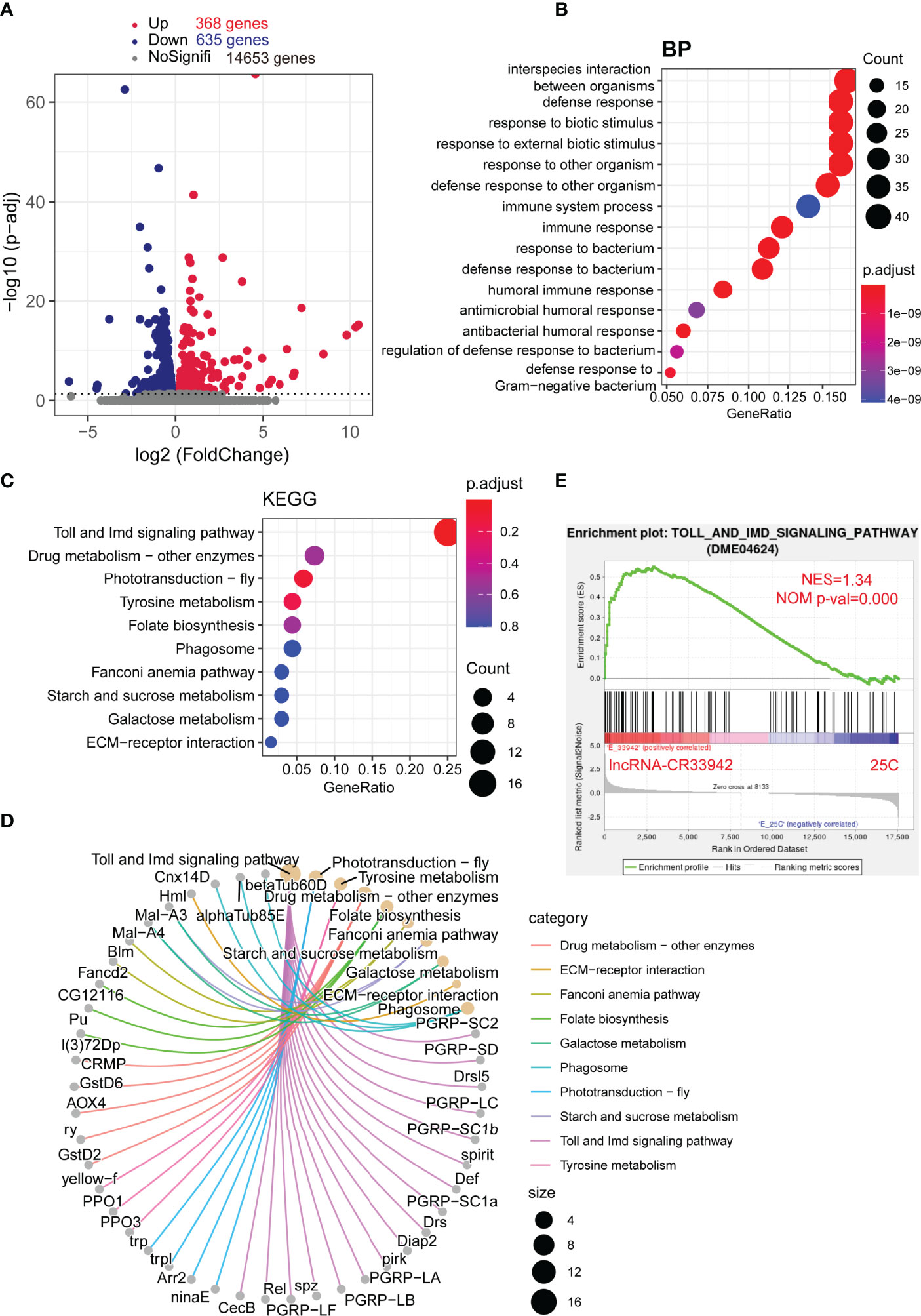

To further confirm the regulatory function of lncRNA-CR33942 in the Drosophila Imd pathway, we performed transcriptome sequencing of lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing and control flies 12 h after E. coli infection. DEGs were identified with an adjusted P < 0.05. The sequencing results revealed 368 upregulated and 635 downregulated DEGs, while the remaining 14,653 genes were not differentially expressed (Figure 2). The enrichment and annotation of biological processes (BP) for the 368 upregulated DEGs mainly focused on defense, immunity, and response to stimuli (Figure 2). Remarkably, the upregulated DEGs were only significantly enriched in the Toll and Imd signaling pathways (Figure 2), and 13/16 DEGs were AMPs and peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) (Figure 2). Considering that enrichment analysis with DEGs is biased, the overall pathway situation cannot be considered. We also used the GSEA algorithm to detect the expression of all the genes in the pathway (51). The results showed that the Toll and Imd signaling pathways were significantly enhanced in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies after infection with NES=1.34 and normal P value=0.000 (Figure 2). These results are consistent with the detection of AMPs, confirming that lncRNA-CR33942 positively regulates the Drosophila Imd pathway.

Figure 2 Enrichment analysis of DEGs in the lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies after infection with Escherichia coli. (A) Volcano map shows DEGs between lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing and control flies after E. coli infection. Red: upregulated DEGs (adjusted P < 0.05); blue: downregulated DEGs (adjusted P < 0.05). (B) Bubble chart shows biological process (BP) enrichment analysis of upregulated DEGs. (C) Bubble chart shows the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of upregulated DEGs. (D) Network chart displays the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis and corresponding upregulated DEGs. (E) GSEA of the RNA-seq data between the lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing and control flies.

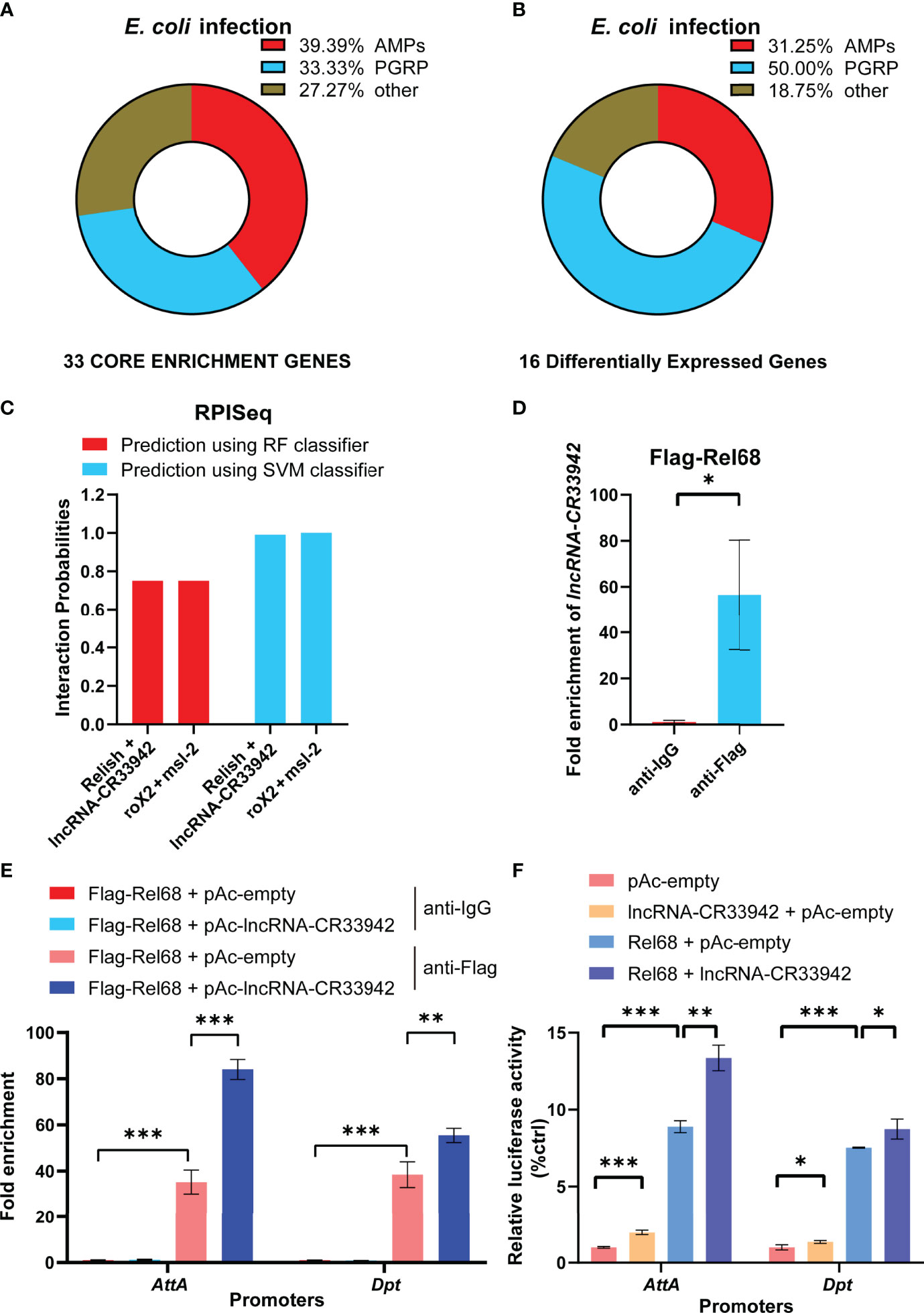

To explore how lncRNA-CR33942 positively regulates the Drosophila Imd signaling pathway, we analyzed the results of GSEA and DEGs in the RNA-seq data. GSEA showed that 39.39% of AMPs and 33.33% of PGRPs were core enriched in the Toll and Imd signaling pathways (Figure 3). Similarly, DEGs of the Toll and Imd signaling pathways contained 31.25% AMPs and 50% PGRPs (Figure 3). AMPs and PGRPs were mainly transcribed by NF-κB proteins (52–55). Considering that lncRNA-CR33942 functions in the nucleus and interacts with Dif/Dorsal to promote transcription, we speculated that lncRNA-CR33942 interacts with Relish to regulate AMP transcription (44). To test this hypothesis, the RPISeq website was used to predict the interaction between Relish and lncRNA-CR33942, with the known interaction pair of roX2 and msl-2 as a positive control (56, 57). The predicted interaction probability score of Relish and lncRNA-CR33942 was nearly consistent with those of the interaction pairs of roX2 and msl-2 (Figure 3). In addition, the results of RIP-qPCR experiments showed that the enrichment fold of Flag-Rel68 for lncRNA-CR33942 was approximately 60 times that of the control group, which further confirmed their interaction (Figure 3). Since the NF-κB transcription factor Relish mainly activates the transcription of AMPs, ChIP-qPCR and dual-luciferase reporter assays were performed to investigate how lncRNA-CR33942 influences the transcriptional regulatory function of Relish. The results of ChIP-qPCR revealed that the enrichment fold on the promoter of AttA and Dpt using anti-Flag was nearly 40 times that of anti-IgG, whereas the enrichment fold was further significantly enhanced after lncRNA-CR33942 overexpression (Figure 3). Similarly, the dual-luciferase reporter assay showed that Rel68 could promote AttA and Dpt promoter activity, which were further significantly enhanced after lncRNA-CR33942 overexpression (Figure 3). In summary, these results suggest that lncRNA-CR33942 interacts with Relish to promote its binding to the AMP promoter, thereby enhancing AMP expression.

Figure 3 lncRNA-CR33942 promotes Relish binding to the AMPs promoter via interaction. Classification analysis was performed on 33 core enriched genes from GSEA results (A) and 16 DEGs (B). (C) Predicted scores for interaction potential of lncRNA-CR33942 with Relish via RPISeq databases. (D) lncRNA-CR33942 enrichment fold was measured by RIP-qPCR using anti-Flag antibody to immunoprecipitate overexpressed Flag-Rel68 in S2 cells. (E) ChIP-qPCR was performed on lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing S2 cells with Flag-Rel68 overexpression normalized to control expression levels. (F) The dual-luciferase reporter assays were performed to detect the transcriptional activity of Rel68 on Dpt and AttA promoters with or without lncRNA-CR33942 overexpression or only overexpressing lncRNA-CR33942. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

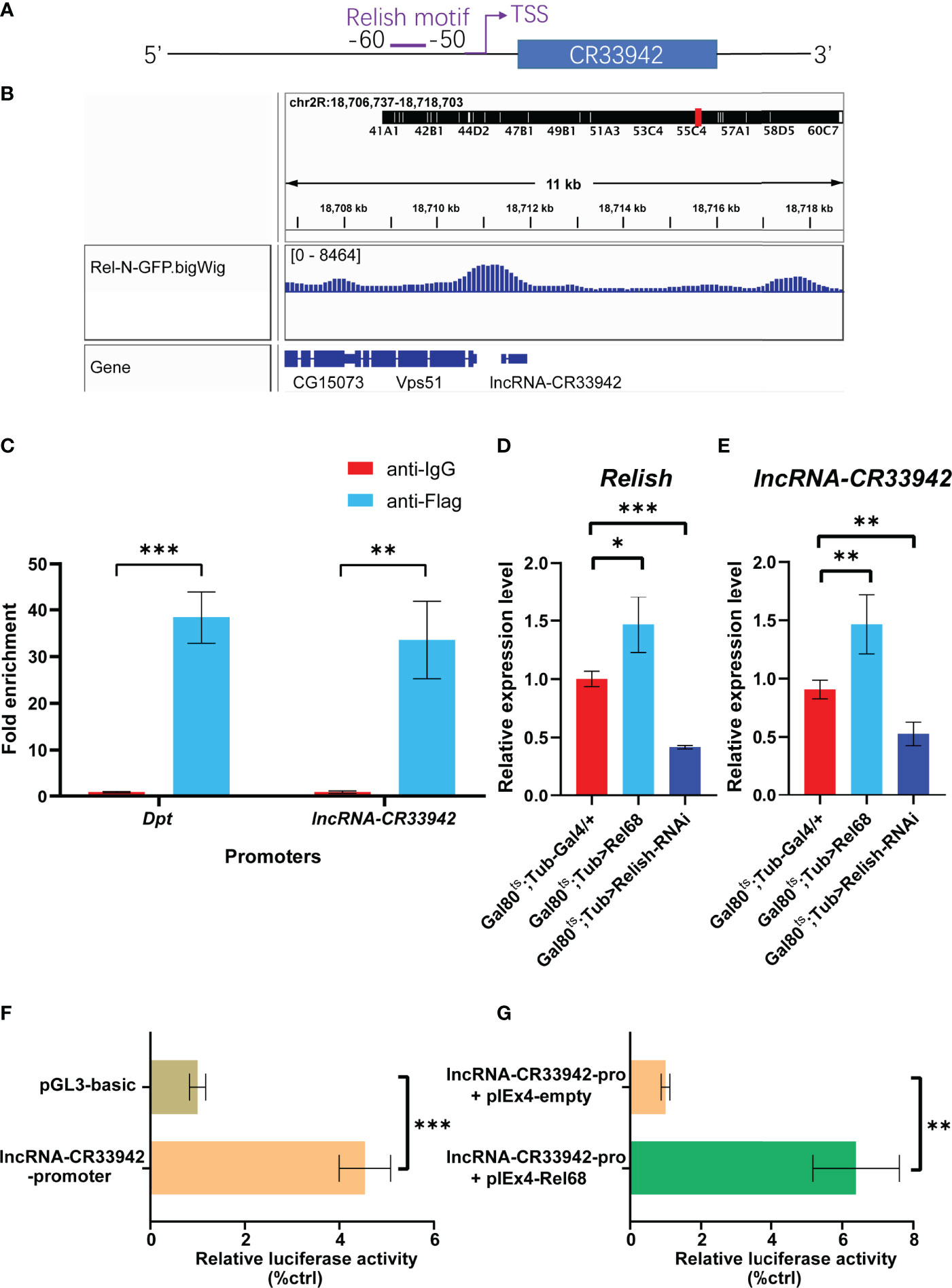

To analyze the critical role of lncRNA-CR33942 in the Imd pathway, we focused on the regulation of lncRNA-CR33942 in the Drosophila Imd immune response. We found the motif of Relish at -60 to -50 bp upstream of the TSS site of lncRNA-CR33942 using FIMO (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/fimo) and PROMO (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3/) website with default parameters (Figure 4). In addition, we downloaded the ChIP-seq data of Rel-N-GFP from the ENCODE database (https://www.encodeproject.org/) and visualized the peak using IGV 2.9.4. An evident peak from the ChIP-seq of Rel-N-GFP was enriched in the promoter region of lncRNA-CR33942 (Figure 4). To further confirm the authenticity of Relish binding to the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter, ChIP-qPCR was performed using S2 cells overexpressing Flag-Rel68. The results showed that the enrichment fold of the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter was approximately 30-fold higher than that of anti-IgG, which was close to the 40-fold enrichment fold of the positive control Dpt promoter (Figure 4). To investigate the function of Relish binding directly to the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter, we examined the expression levels of lncRNA-CR33942 in Rel68 overexpressing and Relish-RNAi flies using RT-qPCR. As expected, lncRNA-CR33942 expression was significantly upregulated in Rel68-overexpressing flies and significantly downregulated in Relish-RNAi flies compared to the controls (Figure E). Furthermore, similar results were confirmed using dual-luciferase reporter assays. First, we cloned the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter region into the pGL3-basic plasmid and detected its promoter activity (Figure 4). After Rel68 overexpression, the activity of the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter significantly increased (Figure 4). These results indicated that Relish could directly bind to the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter and promote its expression.

Figure 4 Relish directly activates the transcription of lncRNA-CR33942. (A) Schematic diagram of Relish motif in the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter region. (B) ChIP-seq visualization of Rel-N-GFP using IGV. (C) ChIP-qPCR was performed in Flag-Rel68 overexpressing S2 cells normalized to control expression levels. The expression levels of Relish (D) and lncRNA-CR33942 (E) in Rel68 overexpressing and Rel68-RNAi flies. (F, G) The dual-luciferase reporter assays were performed to detect the activity of the lncRNA-CR33942 promoter with or without Rel68 overexpression. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

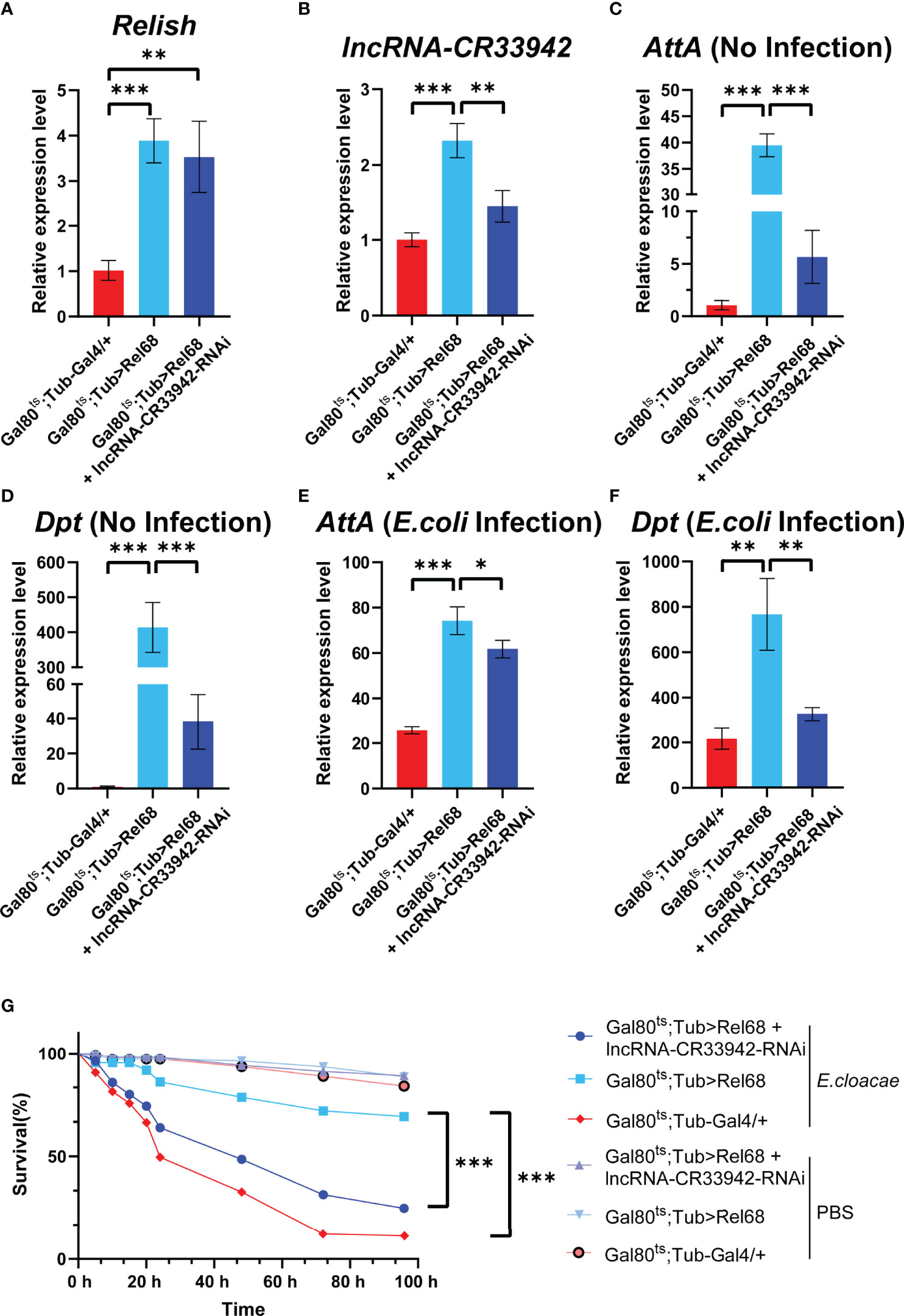

To determine whether Relish could promote the transcription of lncRNA-CR33942 to regulate the Imd pathway in vivo, we constructed Rel68 overexpressing and Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies and detected the expression of Relish and lncRNA-CR33942 in these flies to ensure a successful construction (Figure 5B). The expression levels of Dpt and AttA were examined in Rel68 overexpressing, Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing, and control flies at 12 h post-infection and no infection. In the absence of infection, AttA and Dpt expression levels were significantly upregulated approximately 40-fold and 400-fold, respectively, in Rel68-overexpressing flies compared with the controls, and significantly decreased in Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies (Figure 5D). At 12 h after E. coli infection, the expression levels of both AttA and Dpt in Rel68 overexpressing flies were approximately 4-fold higher than those in controls, while the expression levels of AttA and Dpt in Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies were significantly downregulated compared to those in Rel68 overexpressing flies (Figure 5F). Remarkably, we investigated the survival of these flies following septic injury by the lethal Gram-negative bacterium E. cloacae. Similar to the RT-qPCR results, the results showed that the survival rate of Rel68-overexpressing flies with the highest AMP levels was significantly prolonged. In contrast, the survival rate and AMP levels of Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies were notably decreased compared with Rel68-overexpressing flies (Figure 5). Overall, these results suggested that Relish can activate lncRNA-CR33942 transcription to enhance deficient immune responses and help extend the Drosophila survival rate.

Figure 5 Relish promotes lncRNA-CR33942 transcription to enhance Imd immune response. The expression levels of Relish (A) and lncRNA-CR33942 (B) in Rel68 overexpressing and Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies. AttA and Dpt expression levels in Rel68 overexpressing and Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing flies with no infection (C, D) and 12 h post-infection (E, F). (G) Changes in the survival rate of the Rel68 overexpressing, Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi co-overexpressing, and control flies were measured at 96 h after being treated with PBS or Enterobacter cloacae. Gal80ts; Tub-Gal4/+ - PBS (n = 109), Gal80ts; Tub> Rel68 - PBS (n = 107), Gal80ts; Tub> Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi - PBS (n = 104), Gal80ts; Tub-Gal4/+ - E. cloacae (n = 107), Gal80ts; Tub> Rel68 - E. cloacae (n = 109), Gal80ts; Tub> Rel68 + lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi - E. cloacae (n = 105). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

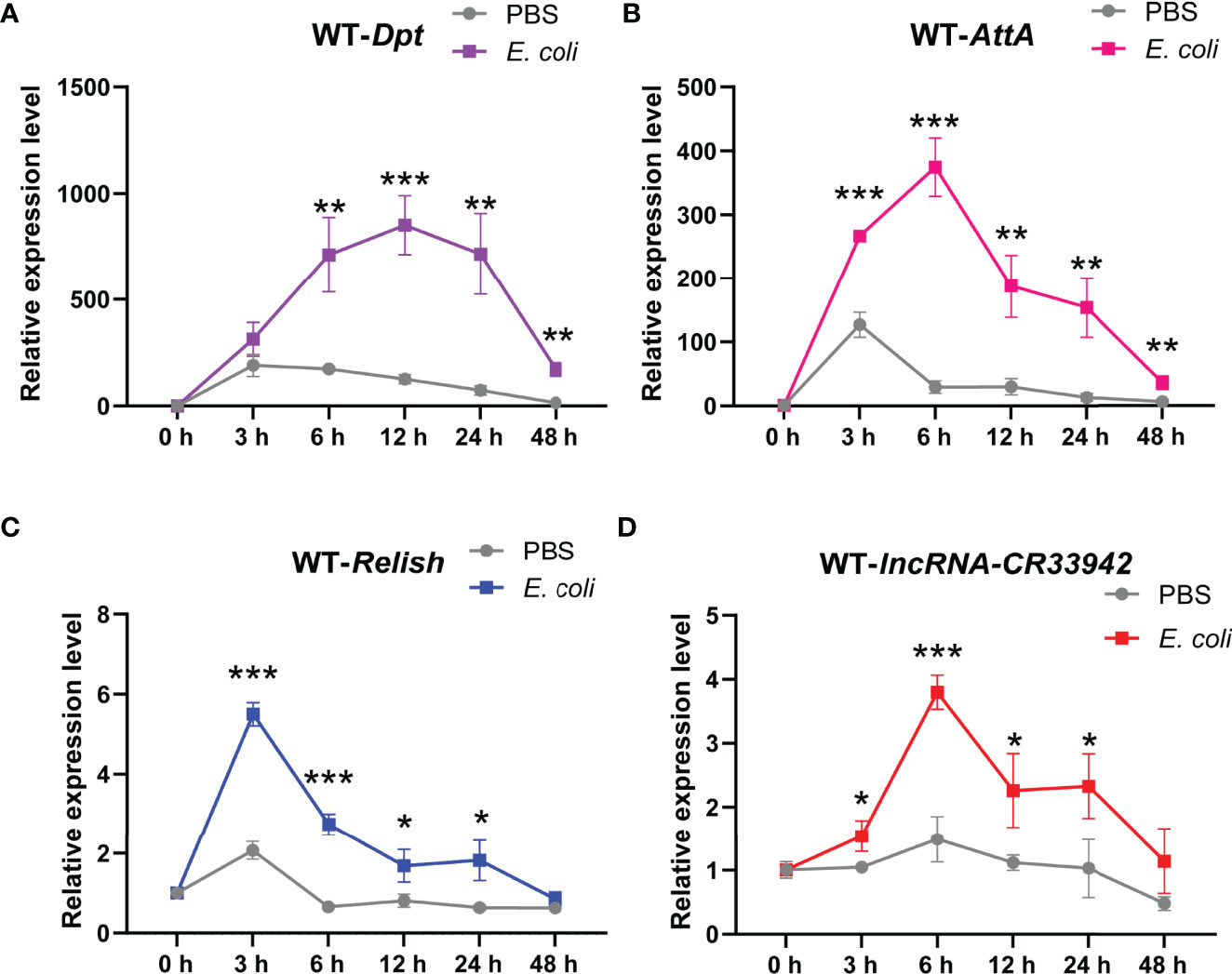

To further explore the physiological function of the Relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMPs regulatory axis, we monitored the dynamic expression of Relish, lncRNA-CR33942, Dpt, and AttA in wild-type flies (w1118) at different time points (0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h) after E. coli infection. The results showed that Dpt expression was significantly upregulated at 6 h after E. coli infection compared with the PBS-injected flies and reached a peak at 12 h, reaching approximately 1000-fold that of uninfected flies, and then decreased to close to the original level at 48 h (Figure 6). Similar to Dpt, the dynamic expression level of AttA was significantly increased at each time point after infection compared to the control, but the peak reached approximately 400 times that of uninfected cells at 6 h after infection (Figure 6). In contrast, the expression level of the transcription factor Relish had reached a peak at 3 h post infection and then decreased (Figure 6). The dynamic expression level of lncRNA-CR33942 was similar to that of AttA, except that the peak at 6 h was four times that of the control (Figure 6).

Figure 6 The Relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMPs regulatory axis contributes to the Drosophila Imd immune response. The expression levels of Dpt (A), AttA (B), Relish (C), and lncRNA-CR33942 (D) in wild-type flies (w1118) at different time points (0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h) after Escherichia coli infection. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

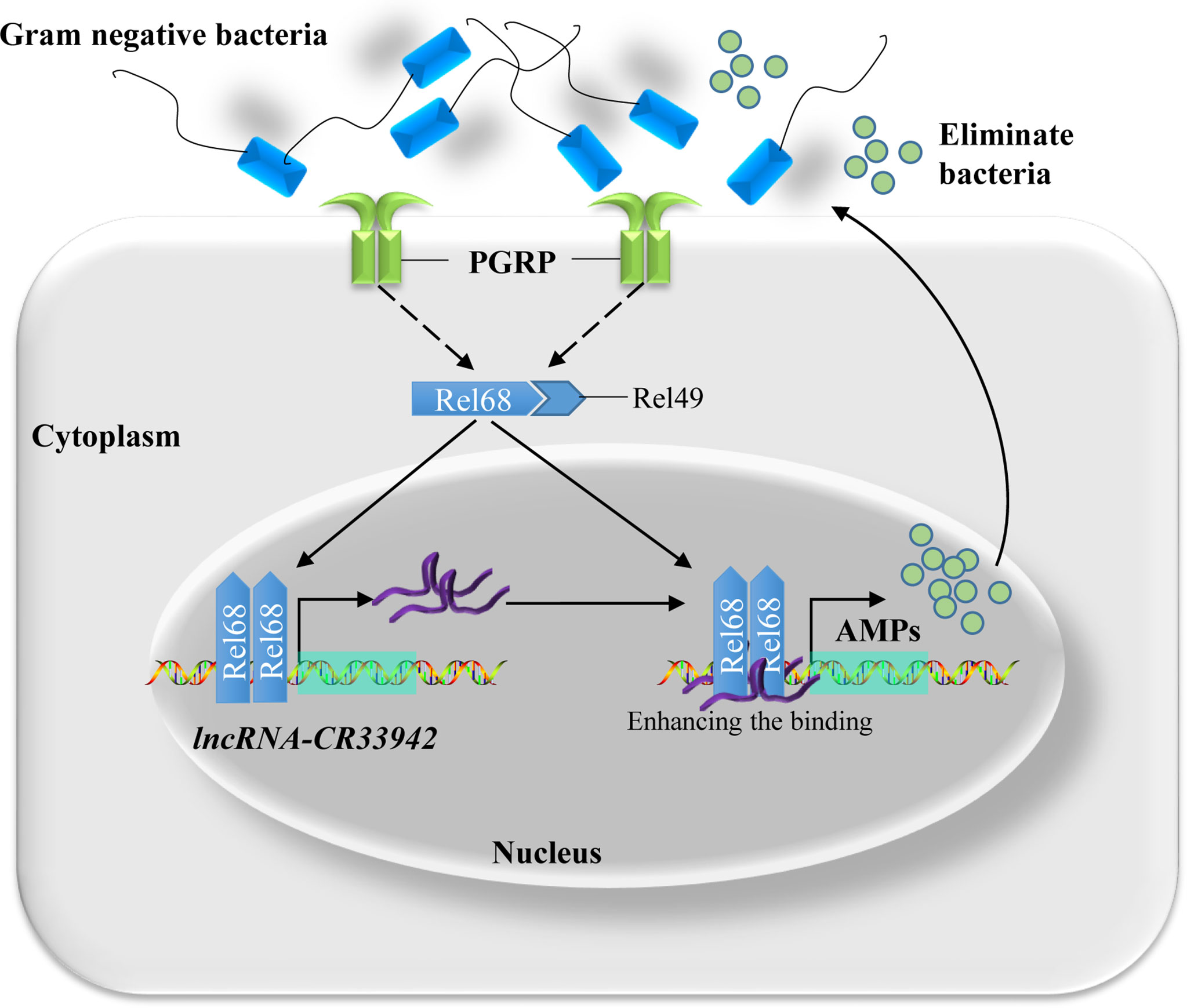

Based on the above results, we proposed a regulatory paradigm for the Relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMP axis in response to the Imd pathway. First, upon attack by Gram-negative bacteria, the Imd pathway is activated, and Relish enters the nucleus to activate the transcription of AMPs and simultaneously promote the expression of lncRNA-CR33942. Next, lncRNA-CR33942 would guide further binding of Relish to the AMP promoters, thereby enhancing the insufficient Imd immune response and maintaining immune homeostasis (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Schematic diagram of Relish-mediated lncRNA-CR33942 enhancing Drosophila Imd immune response and maintaining immune homeostasis. Gram-negative bacteria activated the Imd signaling pathway, and transcription factor Relish entered the nucleus to promote the expression of AMPs and lncRNA-CR33942. The latter interacted with Relish and enhanced its binding to the AMP promoters, which in turn strengthen the insufficient immune response and maintaining immune homeostasis.

The duration and strength of innate immunity need to be tightly regulated because it can be detrimental to the host and can lead to death (58, 59). lncRNAs are a class of heavily transcribed RNAs but lack translatable ORFs and play important regulatory functions in innate immunity. For example, in the differentiation and development of immune cells, lncRNA-H19 (60), lncRNA-Xist (61), lncRNA-HSC1, and lncRNA-HSC2 (62) can regulate quiescence and self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells. In addition, lncRNA-DC (63) and lncRNA-Morrbid (64) help differentiate into specific myeloid cells. However, the functions and mechanisms of lncRNAs in Drosophila innate immunity and their dynamic expression patterns are still poorly understood. In this study, we investigated how lncRNA-CR33942 positively regulates the Drosophila Imd pathway and the dynamic regulatory mechanism of the relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMP regulatory axis in Imd immune homeostasis. Together with previous study revealing the effect of lncRNA-CR33942 on the Toll pathway, the regulator mechanism of lncRNA-CR33942 in Drosophila innate immunity was further clarified (44). This further enriched our understanding of lncRNA regulation in Drosophila immune homeostasis.

LncRNA-CR33942, as an intergenic lncRNA, is located beside the protein-coding gene Vps51 (genomic loci 2R:18,711,391.18,711,951 [+]) and has not been well studied to date. We found the data in FlyAtlas showed that the most abundant distribution site of lncRNA-CR33942 was the fat body of larvae and adults, which is a crucial immune organ in Drosophila (65). In addition, upregulated DEGs in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies after infection were only significantly enriched in the Toll and Imd signaling pathways, and lncRNA-CR33942 was positively correlated with AMP expression (Figures 1, 2C). These results confirmed that lncRNA-CR33942 positively regulates the Drosophila Imd immune response. Notably, only lncRNA-VINR has been reported to regulate the Drosophila Imd pathway AMPs (41). IBIN, which is upregulated several hundred-fold upon M. luteus infection and is thought to regulate innate immunity and metabolism but was later identified as an encoding gene (66, 67). In contrast, the expression levels of lncRNA-CR33942 increased several-fold after infection with E. coli, unlike the hundred-fold increase in AMPs (Figure 6). This suggests that lncRNA-CR33942 is more likely to function as a regulator than as an effector.

The Drosophila Toll and Imd signaling pathways are crucial humoral immune pathways against Gram-positive bacterial/fungal and Gram-negative bacterial invasion, respectively, and are highly conserved with the mammalian TLR and TNFR signaling pathways (2, 68, 69). Our results implied that lncRNA-CR33942 could regulate both pathways and influence various AMPs in response to different pathogens. Notably, the regulation of different AMPs by lncRNA-CR33942 was different. For example, the expression level of AttA was decreased by hundreds of times in infected lncRNA-CR33942-RNAi flies and was increased two-fold in lncRNA-CR33942-overexpressing flies, whereas Dpt was fine-tuned (Figure 1). We speculated that the different regulatory functions of lncRNA-CR33942 on different AMPs may be because lncRNA-CR33942 affects the binding ability of Relish to the AMP promoter. Although the Toll and Imd pathways respond to different pathogens, some of their components, such as the NF-κB transcription factors Dif/Dorsal and Relish, are highly homologous. Therefore, mechanistically, lncRNA-CR33942 can interact with the NF-κB transcription factors of both pathways to promote AMP transcription, thereby enhancing the Drosophila Toll and Imd pathways in response to the invasion of various pathogens.

NF-κB is one of the most important transcription factors in the immune response and understanding how NF-κB regulates lncRNAs can reveal the dynamic regulatory mechanism of lncRNAs in immune processes and their important role in promoting immune homeostasis. However, regulation of lncRNA transcription by NF-κB has mainly been studied in mammals. For example, NF-κB promotes the expression of lncRNA-FIRRE to regulate expression of inflammatory genes (70). In addition, NF-κB-induced lincRNA-Cox2 acts as a co-activator of NF-κB to regulate late-stage inflammatory genes in macrophages (71). However, most of these studies were from immune cell lines, and systematic studies in vivo were lacking. Therefore, we systematically explored the immune regulatory axis of Relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMPs in Drosophila, which broadens our understanding of innate immune regulation and maintenance of homeostasis.

In conclusion, we revealed the mechanism by which the NF-κB transcription factor Relish-induced lncRNA-CR33942 regulates Imd immune responses and maintains immune homeostasis. Briefly, once invaded by Gram-negative bacteria, the Imd pathway is activated, and Relish is cleaved into the nucleus to facilitate lncRNA-CR33942 transcription. lncRNA-CR33942 further interacted with Relish to enhance the binding of Relish to AMP promoters, thereby enhancing the Drosophila Imd immune response and maintaining immune homeostasis (Figure 7). Our study not only discovered a novel Relish/lncRNA-CR33942/AMP regulatory axis, but also has important guiding significance for elucidating the complex regulatory mechanism of the innate immune response in animals.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE198991.

HZ, SW, RL, SL, and PJ were mainly responsible for experimental design. HZ, SW, and LL were responsible for experiment implementation and data analysis. HZ and PJ wrote the article. RL, SL, and PJ were responsible for providing fund support. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Youth Foundation of China (No. 32100390), the National Natural Science Youth Foundation of China (No. 31802015), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institute.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors thank their colleagues and collaborators for their contributions to this original research, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for the fruit fly stocks, Professor Xiaoqiang Yu for the gifts of the pIEx4-Flag-Rel68, pGL3-Dpt-promoter, and pGL3-AttA-promoter plasmids, and Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.905899/full#supplementary-material

1. Riera Romo M, Perez-Martinez D, Castillo Ferrer C. Innate Immunity in Vertebrates: An Overview. Immunology (2016) 148(2):125–39. doi: 10.1111/imm.12597

2. Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The Host Defense of Drosophila Melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol (2007) 25:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615

3. Hoffmann JA. Innate Immunity of Insects. Curr Opin Immunol (1995) 7(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80022-0

4. Hultmark D. Immune Reactions in Drosophila and Other Insects: A Model for Innate Immunity. Trends Genet (1993) 9(5):178–83. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90165-e

5. Khush RS, Leulier F, Lemaitre B. Drosophila Immunity: Two Paths to Nf-Kappab. Trends Immunol (2001) 22(5):260–4. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01887-7

6. Hoffmann JA, Kafatos FC, Janeway CA, Ezekowitz RA. Phylogenetic Perspectives in Innate Immunity. Science (1999) 284(5418):1313–8. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1313

7. Myllymaki H, Valanne S, Ramet M. The Drosophila Imd Signaling Pathway. J Immunol (2014) 192(8):3455–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303309

8. He X, Yu J, Wang M, Cheng Y, Han Y, Yang S, et al. Bap180/Baf180 Is Required to Maintain Homeostasis of Intestinal Innate Immune Response in Drosophila and Mice. Nat Microbiol (2017) 2:17056. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.56

9. Libert S, Chao Y, Chu X, Pletcher SD. Trade-Offs Between Longevity and Pathogen Resistance in Drosophila Melanogaster Are Mediated by Nfkappab Signaling. Aging Cell (2006) 5(6):533–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00251.x

10. Martin M, Hiroyasu A, Guzman RM, Roberts SA, Goodman AG. Analysis of Drosophila Sting Reveals an Evolutionarily Conserved Antimicrobial Function. Cell Rep (2018) 23(12):3537–50.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.029

11. Ji Y, Thomas C, Tulin N, Lodhi N, Boamah E, Kolenko V, et al. Charon Mediates Immune Deficiency-Driven Parp-1-Dependent Immune Responses in Drosophila. J Immunol (2016) 197(6):2382–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600994

12. Goto A, Matsushita K, Gesellchen V, El Chamy L, Kuttenkeuler D, Takeuchi O, et al. Akirins Are Highly Conserved Nuclear Proteins Required for Nf-Kappab-Dependent Gene Expression in Drosophila and Mice. Nat Immunol (2008) 9(1):97–104. doi: 10.1038/ni1543

13. Foley E, O'Farrell PH. Functional Dissection of an Innate Immune Response by a Genome-Wide Rnai Screen. PloS Biol (2004) 2(8):E203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020203

14. Aalto AL, Mohan AK, Schwintzer L, Kupka S, Kietz C, Walczak H, et al. M1-Linked Ubiquitination by Lubel Is Required for Inflammatory Responses to Oral Infection in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ (2019) 26(5):860–76. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0164-x

15. Iatsenko I, Kondo S, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Lemaitre B. Pgrp-Sd, an Extracellular Pattern-Recognition Receptor, Enhances Peptidoglycan-Mediated Activation of the Drosophila Imd Pathway. Immunity (2016) 45(5):1013–23. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.029

16. Park ES, Elangovan M, Kim YJ, Yoo YJ. Ubcd4, an Ortholog of E2-25k/Ube2k, Is Essential for Activation of the Immune Deficiency Pathway in Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2016) 469(4):891–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.062

17. Gendrin M, Zaidman-Remy A, Broderick NA, Paredes J, Poidevin M, Roussel A, et al. Functional Analysis of Pgrp-La in Drosophila Immunity. PloS One (2013) 8(7):e69742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069742

18. Thevenon D, Engel E, Avet-Rochex A, Gottar M, Bergeret E, Tricoire H, et al. The Drosophila Ubiquitin-Specific Protease Dusp36/Scny Targets Imd to Prevent Constitutive Immune Signaling. Cell Host Microbe (2009) 6(4):309–20. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.007

19. Maillet F, Bischoff V, Vignal C, Hoffmann J, Royet J. The Drosophila Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein Pgrp-Lf Blocks Pgrp-Lc and Imd/Jnk Pathway Activation. Cell Host Microbe (2008) 3(5):293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.04.002

20. Kleino A, Myllymaki H, Kallio J, Vanha-aho LM, Oksanen K, Ulvila J, et al. Pirk Is a Negative Regulator of the Drosophila Imd Pathway. J Immunol (2008) 180(8):5413–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5413

21. Persson C, Oldenvi S, Steiner H. Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein Lf: A Negative Regulator of Drosophila Immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol (2007) 37(12):1309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.08.003

22. Kim M, Lee JH, Lee SY, Kim E, Chung J. Caspar, a Suppressor of Antibacterial Immunity in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2006) 103(44):16358–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603238103

23. Li R, Zhou H, Jia C, Jin P, Ma F. Drosophila Myc Restores Immune Homeostasis of Imd Pathway Via Activating Mir-277 to Inhibit Imd/Tab2. PloS Genet (2020) 16(8):e1008989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008989

24. Li S, Shen L, Sun L, Xu J, Jin P, Chen L, et al. Small Rna-Seq Analysis Reveals Microrna-Regulation of the Imd Pathway During Escherichia Coli Infection in Drosophila. Dev Comp Immunol (2017) 70:80–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.01.008

25. Li K, Tian Y, Yuan Y, Fan X, Yang M, He Z, et al. Insights Into the Functions of Lncrnas in Drosophila. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20(18):4646. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184646

26. Kung JT, Colognori D, Lee JT. Long Noncoding Rnas: Past, Present, and Future. Genetics (2013) 193(3):651–69. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146704

27. Hangauer MJ, Vaughn IW, McManus MT. Pervasive Transcription of the Human Genome Produces Thousands of Previously Unidentified Long Intergenic Noncoding Rnas. PloS Genet (2013) 9(6):e1003569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003569

28. Fang S, Zhang L, Guo J, Niu Y, Wu Y, Li H, et al. Noncodev5: A Comprehensive Annotation Database for Long Non-Coding Rnas. Nucleic Acids Res (2018) 46(D1):D308–D14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1107

29. Xu M, Xiang Y, Liu X, Bai B, Chen R, Liu L, et al. Long Noncoding Rna Smrg Regulates Drosophila Macrochaetes by Antagonizing Scute Through E(Spl)Mbeta. RNA Biol (2019) 16(1):42–53. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1556148

30. Hardiman KE, Brewster R, Khan SM, Deo M, Bodmer R. The Bereft Gene, a Potential Target of the Neural Selector Gene Cut, Contributes to Bristle Morphogenesis. Genetics (2002) 161(1):231–47. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.1.231

31. Pek JW, Osman I, Tay ML, Zheng RT. Stable Intronic Sequence Rnas Have Possible Regulatory Roles in Drosophila Melanogaster. J Cell Biol (2015) 211(2):243–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201507065

32. Rios-Barrera LD, Gutierrez-Perez I, Dominguez M, Riesgo-Escovar JR. Acal Is a Long Non-Coding Rna in Jnk Signaling in Epithelial Shape Changes During Drosophila Dorsal Closure. PloS Genet (2015) 11(2):e1004927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004927

33. Herzog VA, Lempradl A, Trupke J, Okulski H, Altmutter C, Ruge F, et al. A Strand-Specific Switch in Noncoding Transcription Switches the Function of a Polycomb/Trithorax Response Element. Nat Genet (2014) 46(9):973–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.3058

34. Pease B, Borges AC, Bender W. Noncoding Rnas of the Ultrabithorax Domain of the Drosophila Bithorax Complex. Genetics (2013) 195(4):1253–64. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.155036

35. Pathak RU, Mamillapalli A, Rangaraj N, Kumar RP, Vasanthi D, Mishra K, et al. Aagag Repeat Rna Is an Essential Component of Nuclear Matrix in Drosophila. RNA Biol (2013) 10(4):564–71. doi: 10.4161/rna.24326

36. Nguyen D, Krueger BJ, Sedore SC, Brogie JE, Rogers JT, Rajendra TK, et al. The Drosophila 7sk Snrnp and the Essential Role of Dhexim in Development. Nucleic Acids Res (2012) 40(12):5283–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks191

37. Maeda RK, Sitnik JL, Frei Y, Prince E, Gligorov D, Wolfner MF, et al. The Lncrna Male-Specific Abdominal Plays a Critical Role in Drosophila Accessory Gland Development and Male Fertility. PloS Genet (2018) 14(7):e1007519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007519

38. Jenny A, Hachet O, Zavorszky P, Cyrklaff A, Weston MD, Johnston DS, et al. A Translation-Independent Role of Oskar Rna in Early Drosophila Oogenesis. Development (2006) 133(15):2827–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.02456

39. Muraoka Y, Nakamura A, Tanaka R, Suda K, Azuma Y, Kushimura Y, et al. Genetic Screening of the Genes Interacting With Drosophila Fig4 Identified a Novel Link Between Cmt-Causing Gene and Long Noncoding Rnas. Exp Neurol (2018) 310:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.08.009

40. Lo Piccolo L, Jantrapirom S, Nagai Y, Yamaguchi M. Fus Toxicity Is Rescued by the Modulation of Lncrna Hsromega Expression in Drosophila Melanogaster. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):15660. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15944-y

41. Zhang L, Xu W, Gao X, Li W, Qi S, Guo D, et al. Lncrna Sensing of a Viral Suppressor of Rnai Activates Non-Canonical Innate Immune Signaling in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe (2020) 27(1):115–28.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.12.006

42. Zhou H, Li S, Wu S, Jin P, Ma F. LnRNA-CR11538 Decoys Dif/Dorsal to Reduce Antimicrobial Peptide Products for Restoring Drosophila Toll Immunity Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22(18):10117. doi: 10.3390/ijms221810117

43. Zhou H, Ni J, Wu S, Ma F, Jin P, Li S. Lncrna-Cr46018 Positively Regulates the Drosophila Toll Immune Response by Interacting With Dif/Dorsal. Dev Comp Immunol (2021) 124:104183. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2021.104183

44. Zhou H, Li S, Pan W, Wu S, Ma F, Jin P. Interaction of Lncrna-Cr33942 With Dif/Dorsal Facilitates Antimicrobial Peptide Transcriptions and Enhances Drosophila Toll Immune Responses. J Immunol (2022) 208(8):1978–88. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2100658

45. Neyen C, Bretscher AJ, Binggeli O, Lemaitre B. Methods to Study Drosophila Immunity. Methods (2014) 68(1):116–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.023

46. Muppirala UK, Honavar VG, Dobbs D. Predicting Rna-Protein Interactions Using Only Sequence Information. BMC Bioinf (2011) 12:489. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-489

47. Chowdhury M, Zhang J, Xu XX, He Z, Lu Y, Liu XS, et al. An in Vitro Study of Nf-Kappab Factors Cooperatively in Regulation of Drosophila Melanogaster Antimicrobial Peptide Genes. Dev Comp Immunol (2019) 95:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2019.01.017

48. Gagliardi M, Matarazzo MR. Rip: Rna Immunoprecipitation. Methods Mol Biol (2016) 1480:73–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6380-5_7

49. Yu G, Wang LG, He QY. Chipseeker: An R/Bioconductor Package for Chip Peak Annotation, Comparison and Visualization. Bioinformatics (2015) 31(14):2382–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv145

50. Busse MS, Arnold CP, Towb P, Katrivesis J, Wasserman SA. A Kappab Sequence Code for Pathway-Specific Innate Immune Responses. EMBO J (2007) 26(16):3826–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601798

51. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2005) 102(43):15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102

52. Choe KM, Werner T, Stoven S, Hultmark D, Anderson KV. Requirement for a Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein (Pgrp) in Relish Activation and Antibacterial Immune Responses in Drosophila. Science (2002) 296(5566):359–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1070216

53. Hedengren M, Asling B, Dushay MS, Ando I, Ekengren S, Wihlborg M, et al. Relish, a Central Factor in the Control of Humoral But Not Cellular Immunity in Drosophila. Mol Cell (1999) 4(5):827–37. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80392-5

54. Wu LP, Anderson KV. Regulated Nuclear Import of Rel Proteins in the Drosophila Immune Response. Nature (1998) 392(6671):93–7. doi: 10.1038/32195

55. Dushay MS, Asling B, Hultmark D. Origins of Immunity: Relish, a Compound Rel-Like Gene in the Antibacterial Defense of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1996) 93(19):10343–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10343

56. Ilik IA, Quinn JJ, Georgiev P, Tavares-Cadete F, Maticzka D, Toscano S, et al. Tandem Stem-Loops in Rox Rnas Act Together to Mediate X Chromosome Dosage Compensation in Drosophila. Mol Cell (2013) 51(2):156–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.001

57. Lee CG, Reichman TW, Baik T, Mathews MB. Mle Functions as a Transcriptional Regulator of the Rox2 Gene. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(46):47740–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408207200

58. Badinloo M, Nguyen E, Suh W, Alzahrani F, Castellanos J, Klichko VI, et al. Overexpression of Antimicrobial Peptides Contributes to Aging Through Cytotoxic Effects in Drosophila Tissues. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol (2018) 98(4):e21464. doi: 10.1002/arch.21464

59. Ragab A, Buechling T, Gesellchen V, Spirohn K, Boettcher AL, Boutros M. Drosophila Ras/Mapk Signalling Regulates Innate Immune Responses in Immune and Intestinal Stem Cells. EMBO J (2011) 30(6):1123–36. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.4

60. Zhou J, Xu J, Zhang L, Liu S, Ma Y, Wen X, et al. Combined Single-Cell Profiling of Lncrnas and Functional Screening Reveals That H19 Is Pivotal for Embryonic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Development. Cell Stem Cell (2019) 24(2):285–98.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.023

61. Mitjavila-Garcia MT, Bonnet ML, Yates F, Haddad R, Oudrhiri N, Feraud O, et al. Partial Reversal of the Methylation Pattern of the X-Linked Gene Humara During Hematopoietic Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. J Mol Cell Biol (2010) 2(5):291–8. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq026

62. Luo M, Jeong M, Sun D, Park HJ, Rodriguez BA, Xia Z, et al. Long Non-Coding Rnas Control Hematopoietic Stem Cell Function. Cell Stem Cell (2015) 16(4):426–38. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.002

63. Wang P, Xue Y, Han Y, Lin L, Wu C, Xu S, et al. The Stat3-Binding Long Noncoding Rna Lnc-Dc Controls Human Dendritic Cell Differentiation. Science (2014) 344(6181):310–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1251456

64. Kotzin JJ, Spencer SP, McCright SJ, Kumar DBU, Collet MA, Mowel WK, et al. The Long Non-Coding Rna Morrbid Regulates Bim and Short-Lived Myeloid Cell Lifespan. Nature (2016) 537(7619):239–43. doi: 10.1038/nature19346

65. Krause SA, Overend G, Dow JAT, Leader DP. Flyatlas 2 in 2022: Enhancements to the Drosophila Melanogaster Expression Atlas. Nucleic Acids Res (2022) 50(D1):D1010–D5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab971

66. Valanne S, Salminen TS, Jarvela-Stolting M, Vesala L, Ramet M. Correction: Immune-Inducible Non-Coding RNA Molecule Lincrna-Ibin Connects Immunity and Metabolism in Drosophila Melanogaster. PloS Pathog (2019) 15(10):e1008088. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008088

67. Valanne S, Salminen TS, Jarvela-Stolting M, Vesala L, Ramet M. Immune-Inducible Non-Coding Rna Molecule LincRNA-Ibin Connects Immunity and Metabolism in Drosophila Melanogaster. PloS Pathog (2019) 15(1):e1007504. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007504

68. Brennan CA, Anderson KV. Drosophila: The Genetics of Innate Immune Recognition and Response. Annu Rev Immunol (2004) 22:457–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104626

69. Hoffmann JA, Reichhart JM. Drosophila Innate Immunity: An Evolutionary Perspective. Nat Immunol (2002) 3(2):121–6. doi: 10.1038/ni0202-121

70. Lu Y, Liu X, Xie M, Liu M, Ye M, Li M, et al. The Nf-Kappab-Responsive Long Noncoding Rna Firre Regulates Posttranscriptional Regulation of Inflammatory Gene Expression Through Interacting With Hnrnpu. J Immunol (2017) 199(10):3571–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700091

Keywords: lncRNA-CR33942, Relish, Imd signaling pathway, Drosophila melanogaster, transcriptional regulation, long noncoding RNA, survival

Citation: Zhou H, Wu S, Liu L, Li R, Jin P and Li S (2022) Drosophila Relish Activating lncRNA-CR33942 Transcription Facilitates Antimicrobial Peptide Expression in Imd Innate Immune Response. Front. Immunol. 13:905899. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.905899

Received: 28 March 2022; Accepted: 02 May 2022;

Published: 02 June 2022.

Edited by:

Erjun Ling, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Ioannis Eleftherianos, George Washington University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Zhou, Wu, Liu, Li, Jin and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ping Jin, amlucGluZ0Buam51LmVkdS5jbg==; Shengjie Li, bGlzaGVuZ2ppZUBuanh6Yy5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.