- 1School of Public Health, Institute for Human Rights, Southeast University, Nanjing, China

- 2Department of Architecture and Built Environment, Architecture and Urban Design, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo, China

- 3Network for Education and Research on Peace and Sustainability, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan

- 4Department of Humanities, South East Technological University, Carlow, Ireland

- 5School of Management—PPGOLD, Federal University of Parana—UFPR, Curitiba, Brazil

- 6Unit of Psychiatry, Department of Public Health and Medicinal Administration, University of Macau, Macao, Macao SAR, China

- 7Institute of Translational Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Macao, Macao SAR, China

- 8Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences, University of Macau, Macao, Macao SAR, China

- 9Institute of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Macau, Macao, Macao SAR, China

Background: Omicron scares and speculations are gaining momentum. Amid the nonstop debates and discussions about COVID-19 vaccines, the “vaccine fatigue” phenomenon may become more prevalent. However, to date, no research has systematically examined factors that shape people’s vaccine fatigue. To bridge the research gap, this study aims to investigate the antecedents that cause or catalyze people’s vaccine fatigue.

Methods: A narrative literature review was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and PsycINFO to identify factors that shape people’s vaccine fatigue. The search was completed on December 6, 2021, with a focus on scholarly literature published in English.

Results: A total of 37 articles were reviewed and analyzed. Vaccine fatigue was most frequently discussed in the context of infectious diseases in general at the pre-vaccination stage. Vaccine fatigue has been identified in the general public, the parents, and the doctors. Overall, a wide range of antecedents to vaccine fatigue has been identified, ranging from the frequency of immunization demands, vaccine side effects, misconceptions about the severity of the diseases and the need for vaccination, to lack of trust in the government and the media.

Conclusion: Vaccine fatigue is people’s inertia or inaction towards vaccine information or instruction due to perceived burden and burnout. Our study found that while some contributors to vaccine fatigue are rooted in limitations of vaccine sciences and therefore can hardly be avoided, effective and empathetic vaccine communications hold great promise in eliminating preventable vaccine fatigue across sectors in society.

Introduction

Omicron scares and speculations are gaining momentum (1, 2). While much remains unknown about the new variant of concern (3), especially in light of the unknowns associated with the BA.2 lineage of the Omicron variant (4), as evidence continues to accumulate, it is becoming clearer that mass vaccination might be one of the best defense mechanisms society has against the outbreaks (5). However, vaccine fatigue may compromise people’s vaccination intention. It is important to note that the nonstop emphasis on the importance and imperative of COVID-19 vaccines has lasted as long as the pandemic has catapulted into a public health crisis (6). In an analysis of 7,000 publishers of content in English in 2021, researchers found that among the 275 million hours people spent on reading about the most discussed topics, stories about vaccines accounted for 43 million of the total hours, whereas an additional 27 million reading hours were spent on content related to various variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (7).

The emergence of Omicron in the Northern Hemisphere’s winter season further suggests that the diverse and dividing debates and discussions about COVID-19 vaccines could become even more intense, if not polarizing (8). Ranging from issues centering on vaccine efficacy, vaccine equity, to the need for booster shots, the accumulated burden and burnout that are resulted from various calls for action could further deepen people’s “vaccine fatigue” (9–11). To make situations worse, confusing and conflicting media reports about vaccination may further complicate the situation. Across the pandemic continuum, chaotic reporting or corrosive informatics on COVID-19 vaccines seen in a wide array of media platforms could often be described as unreliable, unfounded, distorted, to deadly 12–14). Take the United States Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention for instance. As of February 3, 2022, a time when booster shots are part of the vaccination regime, the agency still keeping people confused about what means to be “fully vaccinated” (14). The agency’s most updated (as of January 16, 2022) definition states that “fully vaccinated means a person has received their primary series of COVID-19 vaccines” (15), which is in direct contrast with the agency’s recommendations given by government and health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci (16). This confusion, along with other competing directives and reports (17, 18), in turn, could increase the public’s skepticism about vaccination, and in turn, add avoidable stress to personal and public health (19), let alone their harms on pandemic control and prevention.

It is important to note that, though it has been poorly investigated, vaccine fatigue is not a new phenomenon (20). Vaccine fatigue could be particularly pronounced amid large infectious disease outbreaks, largely due to people’s pronounced needs to balance the burden and burnout associated with vaccination and “social conscience, solidarity, and feelings of duty” (21). However, due to a lack of research, little is known about what factors shape people’s vaccine fatigue. The importance of understanding the antecedents to vaccine fatigue is twofold. First, an in-depth understanding of the factors that cause or catalyze people’s vaccine fatigue can help government and health officials better address the issue. Overall, without knowing what factors influence people’s vaccine fatigue, it can be extremely difficult for stakeholders to develop evidence-based interventions to reduce vaccine fatigue’s impacts on mass vaccination. Furthermore, not having a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon and developing countermeasures against it could cause vaccine fatigue to progress into more permanent forms of vaccination non-adoption, such as vaccine hesitancy or hostility (22). This, in turn, could further hinder society’s mass vaccination efforts. Thus, to bridge the research gaps, this study aims to examine the antecedents that cause or catalyze people’s vaccine fatigue, and highlight potential solutions that could help alleviate vaccine fatigue in society.

Methods

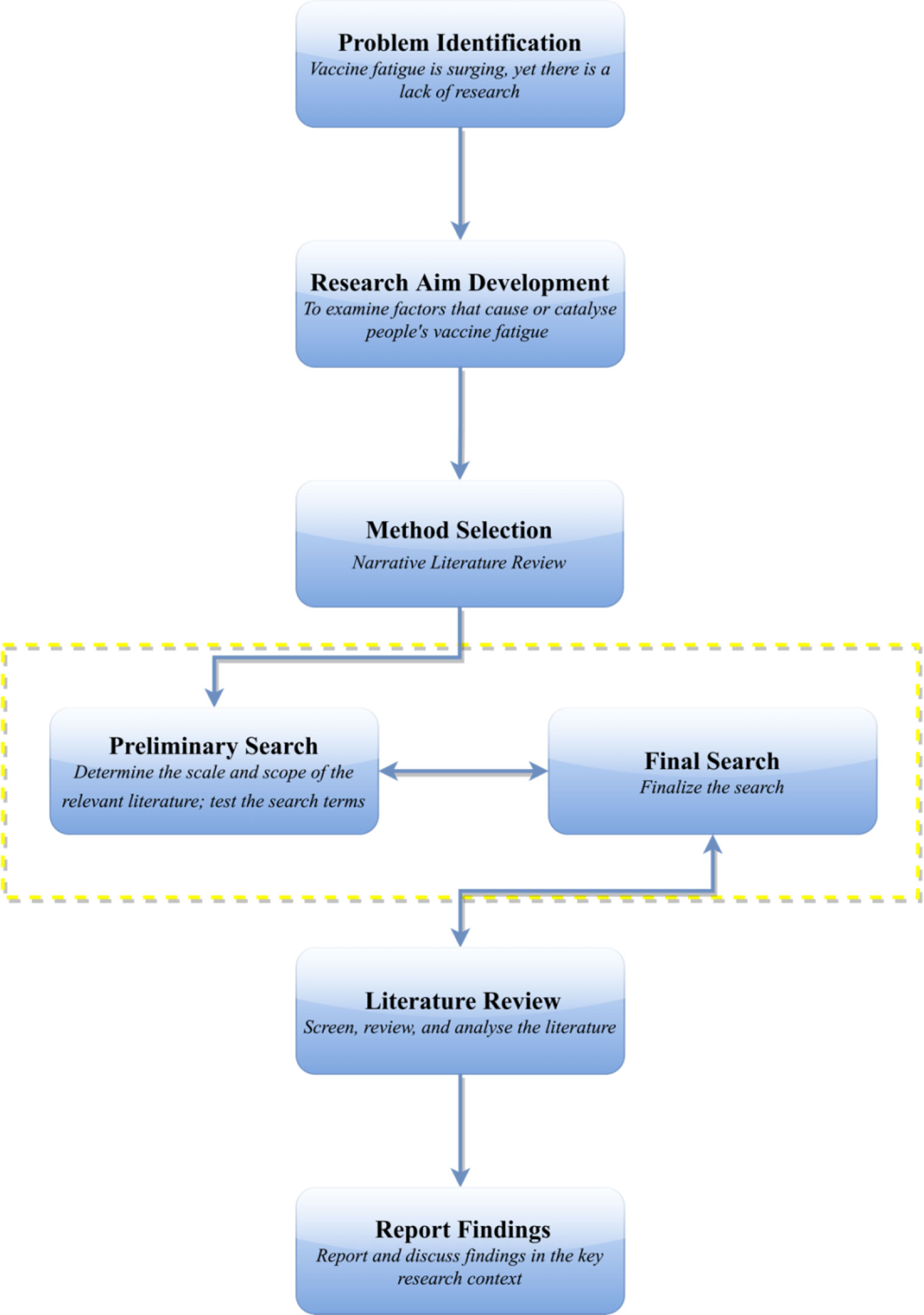

A literature review was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and PsycINFO to identify factors that introduce or intensify vaccine fatigue in society. The preliminary search was conducted on December 2, 2021, with the final search completed on December 6, 2021. All scholarly papers that addressed “vaccine fatigue”, “vaccination fatigue”, or “immunization fatigue” were examined. Records were excluded if: (1) they were not published in English, (2) the vaccines studied were not for humans [e.g., for dogs (23, 24) and poultry (25, 26)], and (3) they did not provide full text for review. In terms of theoretical framework, the narrative literature review approach was adopted, which could be understood as “an objective, thorough summary and critical analysis of the relevant available research and non-research literature on the topic being studied” (27). One key advantage of the narrative literature review approach is that it can help the researchers gain a systematic and structural understanding of what could be scattered literature in an effective manner (27). A flowchart of the research process could be found in Figure 1.

Results

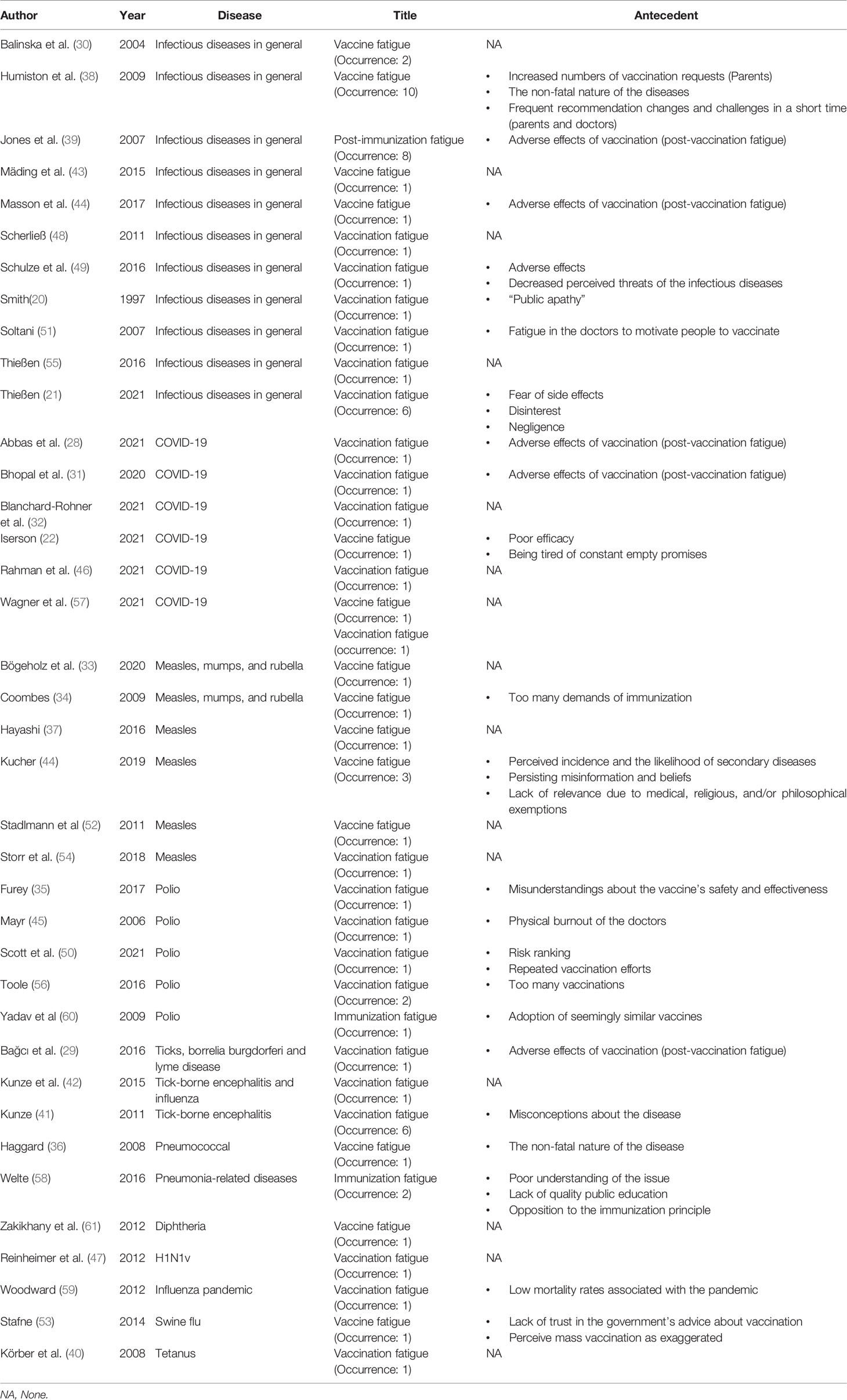

Overall, among all of the 47 articles found via the targeted search, ten papers were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria. A total of 37 articles were included in the final review and analysis, which yielded 70 combined occurrences of the phrases “vaccine fatigue”, “vaccination fatigue”, and “immunization fatigue” (20–22, 28–61).

Except for two pre-prints (at the time of the review) (31, 57), all of the included papers are peer-reviewed. The terms were most frequently discussed in the context of infectious diseases in general (N=11; 29.7%), followed by measles, mumps, and rubella (N=6; 16.2%), COVID-19 (N=6; 16.2%), and polio (N=5; 13.5%). The phenomenon was mainly discussed in the context of pre-vaccination, with only five articles focusing on post-vaccine fatigue syndrome (N=5; 13.5%). Most of the studies utilized the term to refer to vaccine fatigue among the public, with only two articles discussed the phenomenon from the doctors’ perspectives (45, 51), and one included both parents and doctors’ points of view (38). As detailed in Table 1, a large number of articles only briefly mentioned the phrases, with limited to no insights into their antecedents offered (N=16; 43.2%).

Discussion

This study set out to examine key factors that cause or catalyze people’s vaccine fatigue. This is the first research that systematically investigated the concept and phenomenon of vaccine fatigue. Vaccine fatigue could be understood as people’s inertia or inaction towards vaccine information or instruction due to perceived burden and burnout. By providing an in-depth and comprehensive understanding of the factors that form or fuel vaccine fatigue in society, the insights of the study can help government and health officials better design and develop countermeasures to limit the presence and prevalence of vaccine fatigue. Furthermore, our study could also help society prevent vaccine fatigue from progressing into worse forms of vaccine non-adoption (e.g., vaccine hostility), and in turn, contribute to the acceleration of mass vaccination in light of the Omicron scares and beyond. Overall, a wide range of antecedents to vaccine fatigue has been identified, ranging from the frequency of immunization demands, vaccine side effects, misconceptions about the severity of the diseases and the need for vaccination, to lack of trust in the government and the media.

Better Vaccine Science Is Needed

Largely due to the prevalence of infectious diseases and limitations to current medical sciences, vaccine fatigue may be difficult to avoid in certain circumstances. Our findings show that many antecedents of vaccine fatigue are rooted in flaws in vaccine sciences, such as adverse effects caused by vaccination (28, 29, 31, 39, 44), poor vaccine efficacy (21, 22, 49), as well as too many vaccination demands in a relatively short period of time (34, 50, 56, 60). A study on people who received the BioNTech-Pfizer doses, for instance, found that 83.3% of the vaccine recipients experienced post-vaccination fatigue (28). In countries such as Pakistan, many children may have already received 15 doses of vaccines, which could result in vaccine fatigue in both the children and the parents (56). The limitations in current vaccine technologies are also reflected in the similarity of the vaccines people are requested to adopt, which could further fuel vaccine fatigue in the public (60).

The effects of this “too much can be an overdose” phenomenon are also felt by healthcare professionals like doctors, in which case they could become too exposed to the ever-present imperative to motivate people to vaccinate (51), or experience too much physical burnout to carry out the tasks (45). Our findings bear great implications for the current pandemic, particularly in light of the knowns and unknowns about the compounding effects of the Omicron variant and the influenza virus (62). Even before the identification of Omicron, many societies across the world have already demanded the public to take a 3-dose regime for additional protection, often with conflicting and confusing guidelines and recommendations (63), within a timeframe and a digital reality where the promise of “one dose is enough” is still making echoes (64, 65). In other words, it is possible that, with increased urgency for mass vaccination that is fueled by concerns about Omicron and the influenza-induced syndemics (66), people’s vaccine fatigue may become more pronounced and prevalent.

These insights combined, overall, highlight the need for greater investments in vaccine sciences and technologies, so that more user-friendly vaccines, in terms of the overall efficacy, duration of their protection, and the logistics associated with dose administration, could become available to the public. From the dose administration perspective, for instance, vaccines that are less invasive, such as inhalable vaccines, edible vaccines, and skin-based immunization (67–69), may also hold promise in easing people’s vaccine fatigue. It is important to note that, as our findings suggest, the public’s perceived burden and burnout that cause or catalyze their vaccine fatigue could both be psychological and physical. Therefore, in addition to developing more competent vaccines, the government and health officials should also be more mindful about how vaccine communications are designed, developed, and deployed.

Ineffective Vaccine Communications

Our findings indicate that vaccine communications may play a critical role in shaping people’s vaccine fatigue. Overall, a wide range of antecedents to people’s vaccine fatigue is rooted in the lack of effective vaccine communications, ranging from misconceptions about vaccine efficacy and effectiveness (35, 58), poor understanding about the severity of the diseases or the urgency for vaccination (36, 41, 49, 50, 59), and erroneous or contradictory beliefs that hinder vaccination (44, 53). One way to address this issue, as indicated by previous research, is via developing effective education and communication programs, such as persuasive advertising campaigns (20, 21), as opposed to compulsory interventions. A key consideration for not employing stringent, if not draconian, measures to address people’s vaccine fatigue centres on the possibility that they may result in unintended consequences such as stigmatization or discrimination in the public (21, 55).

This consideration is in line with our findings, which suggest that rather than a permanent trait found in populations such as anti-vaxxers, vaccine fatigue broadly represents a transitory stage that is more common in people who hold a pro-vaccination view. Considering that compulsory interventions may result in potential consequences such as forcing the momentary vaccine fatigue into more aggressive and permanent forms of vaccine non-adoption, such as vaccine hostility, it is important that government and health officials adopt an empathetic approach to vaccine communications (70). This is particularly important considering that many nations worldwide have implemented or are considering establishing vaccine mandates amid COVID-19, even though considerable public backlash is present (71–73). The need for mindful and compassionate interactions with the public might be particularly pronounced in light of the potential unintended consequences vaccine communication could cause.

Lack of Trust

This study’s findings show that a lack of trust in the government and the media is also an antecedent to vaccine fatigue (53). As a vital bridge between science, scientists, and the public throughout health emergencies like COVID-19, the media industry is a critical link in society’s collective defence against the pandemic. Take COVID-19 for instance. Across the pandemic, both legacy media and social media platforms have played an indispensable role in informing almost every aspect about COVID-19 and more (74). However, what is also evident in the pandemic is that, due to the prevalence of COVID-19 infodemics and the polarizing role many media outlets have endorsed (12, 19, 75). The public’s trust over media reports on COVID-19, such as COVID-19 vaccines, has been deteriorating (76, 77).

It is also important to note that, even without the highly mediated influence of the news reports and analyses, the sheer scale and scope of negative events induced by COVID-19 may be enough to cause discomfort and distress in the public (19). It is possible that, to avoid potential or additional stress caused by the media reports on COVID-19 vaccines, people might develop a passive attitude towards news about the vaccines and the shots themselves, in the form of vaccine communication avoidance, and in turn, vaccine fatigue. In light of the dearth of research and the outsized influence of media on public’s health behaviors amid the beyond COVID-19 (78), more research and interventions are needed to ensure a healthy and symbiotic relationship can be formed between government and health officials, media professionals, citizen journalists, and the public in the context of vaccine communications.

Limitations

While our study bridges important gaps in the literature, it is not without limitations. For starters, we only reviewed and analyzed scholarly literature, which means that insights such as relevant media reports were not included in the review. Furthermore, only academic literature in English was considered in the current study. In light of the multifaceted nature of vaccine fatigue and its implications, future research could consider extending current understandings on vaccine fatigue by conducting country- or language-specific investigations on the phenomenon.

Conclusion

Vaccine fatigue is detrimental to both personal and public health. Our study found that effective vaccine communications hold great promise in limiting vaccine fatigue among key stakeholders. The role of trust is also incremental to shaping people’s compliance with vaccine-related directives, which in turn, further emphasizes the importance of developing safer and more efficacious vaccines, along with responsible and accountable public health directives in mitigating vaccine fatigue. Overall, in light of the knowns and unknowns about COVID-19, ranging from the high transmissibility of Omicron to the lack of knowledge about Omicron’s variant—BA.2, in order to effectively prevent vaccine fatigue from plaguing pandemic control and prevention efforts, more endeavors are needed to understand the causes and consequences of vaccine fatigue amid COVID-19 and beyond.

Author Contributions

ZS conceived the work, reviewed the literature, drafted, and edited the manuscript. AC, DM, CV, and Y-TX reviewed the literature and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by FHS Faculty funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the editor and reviewers for their constructive input and kind feedback.

References

1. Mallapaty S. Omicron-Variant Border Bans Ignore the Evidence, Say Scientists (2021). Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03608-x.

2. Su Z, McDonnell D, Ahmad J, Cheshmehzangi A, Xiang Y-T. Mind the “Worry Fatigue” Amid Omicron Scares. Brain Behavior Immun (2022) 101:60–1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.023

3. World Health Organization. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern.

4. Barnes O, Hollowood E, Mancini DP, Riordan P. BA.2: The Omicron Sub-Variant Outpacing its Predecessor (2022). Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/efa3ceaf-b777-4a06-b4ef-bf1330f105d6.

5. Mahase E. Covid-19: Do Vaccines Work Against Omicron—and Other Questions Answered. BMJ (2021) 375:n3062. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n3062

6. World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO's COVID-19 Response (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline.

7. The Economist. 2021’s Biggest Stories Were Covid-19 and America’s Presidential Transition (2021). Available at: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/12/18/2021s-biggest-stories-were-covid-19-and-americas-presidential-transition.

8. Hinsliff G. If Further Covid Restrictions are Needed, the Debate Could Get Uglier This Time (2021). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/dec/02/omicron-restrictions-prejudice-against-unvaccinated-people-virus.

9. Deutsche Welle. Germany's Fight Against Vaccine Fatigue (2021). Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-fight-against-vaccine-fatigue/a-58162123.

10. France24. Replete With Jabs, South Africa Now Battles Vaccine Apathy (2021). Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210819-replete-with-jabs-south-africa-now-battles-vaccine-apathy.

11. Neergaard L. It’s Flu Vaccine Time, Even If You’ve had Your COVID Shots (2021). Available at: https://www.latimes.com/science/story/2021-09-30/its-flu-vaccine-time-even-if-youve-had-your-covid-shots.

12. Evanega S, Lynas M, Adams J, Smolenyak K. Coronavirus Misinformation: Quantifying Sources and Themes in the COVID-19 ‘Infodemic’. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University (2021).

13. Gallotti R, Valle F, Castaldo N, Sacco P, De Domenico M. Assessing the Risks of ‘Infodemics’ in Response to COVID-19 Epidemics. Nat Hum Behav (2020) 4(12):1285–93. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-00994-6

14. Lukpat A. What Does it Mean to be ‘Fully Vaccinated’ Against Covid-19? (2022). Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/article/fully-vaccinated-covid.html.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Stay Up to Date With Your Vaccines (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.html#print.

16. Fauci A. Fauci Urges Americans to Get Covid Booster as US Surpasses 50m Positive Cases (2022). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/dec/12/fauci-covid-omicron-booster-shots.

17. Galewitz P. Health Experts Worry CDC’s Covid Vaccination Rates Appear Inflated (2021). Available at: https://khn.org/news/article/cdc-senior-covid-vaccination-rates-appear-inflated/.

18. Stanley-Becker I, Guarino B, Sellers FS, Cha AE, Sun LH. Cdc’s Mask Guidance Spurs Confusion and Criticism, as Well as Celebration (2021). Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/05/14/cdc-mask-update-decision-confusion/.

19. Su Z, McDonnell D, Wen J, Kozak M, Abbas J, Šegalo S, et al. Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 Media Coverage: The Need for Effective Crisis Communication Practices. Globalization Health (2021) 17(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00654-4

20. Smith SJ. Concluding Remarks to the Conference on Vaccinology: “Building Life-Long Immunity”. Biologicals (1997) 25(2):253–5. doi: 10.1006/biol.1997.0095

21. Thießen M. Security, Society, and the State Vaccination Campaigns in 19th and 20th Century Germany. Historical Soc Res / Historische Sozialforschung (2021) 46(4):211–315.

22. Iserson KV. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Vaccine Development and Production: An Ethical Way Forward. Cambridge Q Healthcare Ethics (2021) 30(1):59–68. doi: 10.1017/S096318012000047X

23. Halecker S, Bock S, Beer M, Hoffmann B. A New Molecular Detection System for Canine Distemper Virus Based on a Double-Check Strategy. Viruses (2021) 13(8):1–9. doi: 10.3390/v13081632

24. Schwedinger E, Kuhne F, Moritz A. What Influence do Vets Have on Vaccination Decision of Dog Owners? Results of an Online Survey. Veterinary Rec (2021) 189(7):e297. doi: 10.1002/vetr.297

25. Domenech J, Dauphin G, Rushton J, McGrane J, Lubroth J, Tripodi A, et al. Experiences With Vaccination in Countries Endemically Infected With Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza: The Food and Agriculture Organization Perspective. Rev Sci Tech (2009) 28(1):293–305. doi: 10.20506/rst.28.1.1865

26. Hinrichs J, Otte J. arge-Scale Vaccination for the Control of Avian Influenza: Epidemiological and Financial Implications. In: Zilberman D, Otte J, Roland-Holst D, Pfeiffer D, editors. Health and Animal Agriculture in Developing Countries. New York, NY: Springer New York (2012). p. 207–31.

27. Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. Undertaking a Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Approach. Br J Nurs (2008) 17(1):38–43. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.1.28059

28. Abbas S, Abbas B, Amir S, Wajahat M. Evaluation of Adverse Effects With COVID-19 Vaccination in Pakistan. Pakistan J Med Sci (2021) 37(7):1–6. doi: 10.12669/pjms.37.7.4522

29. Bağcı IS, Ruzicka T. Ticks, Borrelia Burgdorferi and Lyme Disease. Turk J Dermatol (2016) 10:116–21. doi: 10.4274/tdd.3038

30. Balinska MA. What is Vaccine Advocacy?: Proposal for a Definition and Action. Vaccine (2004) 22(11):1335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.01.039

31. Bhopal S, Olabi B, Bhopal R. Nature of, Immune Reaction to and Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccines: Synthesis of Information Including Exclusions From Ten Phase II Trials for Planning Vaccination Programmes. SSRN (2020) 1–16. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3732847

32. Blanchard-Rohner G, Caprettini B, Rohner D, Voth H-J. Impact of COVID-19 and Intensive Care Unit Capacity on Vaccination Support: Evidence From a Two-Leg Representative Survey in the United Kingdom. J Virus Eradication (2021) 7(2):100044. doi: 10.1016/j.jve.2021.100044

33. Bögeholz J, Russkamp NF, Wilk CM, Gourri E, Haralambieva E, Schanz U, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Antibody Titers Against Measles, Mumps, and Rubella in Recipients of Allogenic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant (2020) 26(3):581–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.10.027

35. Furey SG. Groundwater Governance for Poverty Eradication, Social Equity and Health. In: Villholth KG, López-Gunn E, Conti KI, Garrido A, Gun J, editors. Advances in Groundwater Governance. London: CRC Press (2017). p. 269–87.

36. Haggard M. Otitis Media: Prospects for Prevention. Vaccine (2008) 26:G20–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.009

37. Hayashi MAL. Integrating Mathematical Models of Behavior and Infectious Disease: Applications to Outbreak Dynamics and Control. (Doctor of Philosophy). University of Michigan (2016) 1–23. Available at: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/133434.

38. Humiston SG, Albertin C, Schaffer S, Rand C, Shone LP, Stokley S, et al. Health Care Provider Attitudes and Practices Regarding Adolescent Immunizations: A Qualitative Study. Patient Educ Couns (2009) 75(1):121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.012

39. Jones JF, Kohl KS, Ahmadipour N, Bleijenberg G, Buchwald D, Evengard B, et al. Fatigue: Case Definition and Guidelines for Collection, Analysis, and Presentation of Immunization Safety Data. Vaccine (2007) 25(31):5685–96. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.065

40. Körber A, Graue N, Rietkötter J, Kreuzfelder E, Grabbe S, Dissemond J. Insufficient Tetanus Vaccination Status in Patients With Chronic Leg Ulcers. Dermatology (2008) 217(1):69–73. doi: 10.1159/000127317

41. Kunze U. Tick-Borne Encephalitis: New Paradigms in a Changing Vaccination Environment. Wien Med Wochenschr (2011) 161(13-14):361–4. doi: 10.1007/s10354-011-0005-8

42. Kunze U, Kunze M. The Austrian Vaccination Paradox: Tick-Borne Encephalitis Vaccination Versus Influenza Vaccination. Cent Eur J Public Health (2015) 23(3):223–6. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a4169

43. Mäding C, Jacob C, Münch C, von Lindeman K, Klewer J, Kugler J. Vaccination Coverage Among Students From a German Health Care College. Am J Infect Control (2015) 43(2):191–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.019

44. Masson J-D, Crépeaux G, Authier F-J, Exley C, Gherardi RK. Critical Analysis of Reference Studies on the Toxicokinetics of Aluminum-Based Adjuvants. J Inorganic Biochem (2017) 181:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2017.12.015

45. Mayr A. Eradication and Elimination of Epidemics. In: Dtsch Arztebl, vol. 103. (2006)Berlin: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. p. 3115–8. Available at: www.aerzteblatt.de.

46. Rahman MA, Islam MS. Early Approval of COVID-19 Vaccines: Pros and Cons. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeutics (2021) 17(10):3288–96. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1944742

47. Reinheimer C, Doerr HW, Friedrichs I, Stürmer M, Allwinn R. H1N1v at a Seroepidemiological Glance: Is the Nightmare Over? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2012) 31(7):1467–71. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1465-x

48. Scherließ R. Delivery of Antigens Used for Vaccination: Recent Advances and Challenges. Ther Delivery (2011) 2(10):1351–68. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.80

49. Schulze K, Ebensen T, Riese P, Prochnow B, Lehr C-M, Guzmán CA. New Horizons in the Development of Novel Needle-Free Immunization Strategies to Increase Vaccination Efficacy. In: Stadler M, Dersch P, editors. How to Overcome the Antibiotic Crisis : Facts, Challenges, Technologies and Future Perspectives. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2016). p. 207–34.

50. Scott RP, Cullen AC, Chabot-Couture G. Disease Surveillance Investments and Administration: Limits to Information Value in Pakistan Polio Eradication. Risk Anal (2021) 41(2):273–88. doi: 10.1111/risa.13580

51. Soltani M. Routine Childhood Vaccinatio in Germany - Well-Founded? (Master). Department Gesundheitswissenschaften (2007). Available at: https://reposit.haw-hamburg.de/handle/20.500.12738/6209.

52. Stadlmann S, Lenggenhager DM, Alves VA, Nonogaki S, Kocher TM, Schmid H-R, et al. Histopathologic Characteristics of the Transitional Stage of Measles-Associated Appendicitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Hum Pathol (2011) 42(2):285–90. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.006

53. Stafne T. Human Papilloma Virus Awareness, Knowledge and Vaccine Acceptance Among Norwegian Adolescents (Master). University of Oslo (2014). Available at: https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/39982/7/StafneMasteroppgave09May2014.pdf.

54. Storr C, Sanftenberg L, Schelling J, Heininger U, Schneider A. Measles Status-Barriers to Vaccination and Strategies for Overcoming Them. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int (2018) 115(43):723–30. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0723

55. Thießen M. Risk as a Resource: On the Interplay Between Risks, Vaccinations and Welfare States in Nineteenth and Twentieth-Century Germany. Historical Soc Res (2016) 41(1(1 (155):70–90. doi: 10.12759/hrs.41.2016.1.70-90

56. Toole MJ. So Close: Remaining Challenges to Eradicating Polio. BMC Med (2016) 14(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0594-6

57. Wagner TR, Schnepf D, Beer J, Ruetalo N, Klingel K, Kaiser PD, et al. Biparatopic Nanobodies Protect Mice from Lethal Challenge with SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern. EMBO Rep (2021) 23(2):e53865. doi: 10.15252/embr.202153865

58. Welte T. Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine–Equally Effective for Everyone? Deutsches Arzteblatt Int (2016) 113(9):137–8. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0137

59. Woodward M. Immunisation of Older People. J Pharm Pract Res (2012) 42(4):316–22. doi: 10.1002/j.2055-2335.2012.tb00197.x

60. Yadav K, Rai SK, Vidushi A, Pandav CS. Intensified Pulse Polio Immunization: Time Spent and Cost Incurred at a Primary Healthcare Centre. Natl Med J India (2009) 22(1):13–7.

61. Zakikhany K, Efstratiou A. Diphtheria in Europe: Current Problems and New Challenges. Future Microbiol (2012) 7(5):595–607. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.24

62. Callaway E, Ledford H. How Bad is Omicron? What Scientists Know So Far (2021). Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03614-z.

63. Kim DKD, Kreps GL. An Analysis of Government Communication in the United States During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations for Effective Government Health Risk Communication. World Med Health Policy (2020) 12(4):398–412. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.363

64. Chen W. Promise and Challenges in the Development of COVID-19 Vaccines. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeutics (2020) 16(11):2604–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1787067

65. Su Z, McDonnell D, Cheshmehzangi A, Li X, Maestro D, Šegalo S, et al. With Great Hopes Come Great Expectations: Access and Adoption Issues Associated With COVID-19 Vaccines. JMIR Public Health Surveill (2021) 7(8):e26111. doi: 10.2196/26111

66. Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is Not a Pandemic. Lancet (2020) 396(10255):874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6

67. Heida R, Hinrichs WLJ, Frijlink HW. Inhaled Vaccine Delivery in the Combat Against Respiratory Viruses: A 2021 Overview of Recent Developments and Implications for COVID-19. Expert Rev Vaccines (2021), 1–18. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2021.1903878

68. Korkmaz E, Balmert SC, Sumpter TL, Carey CD, Erdos G, Falo LD. Microarray Patches Enable the Development of Skin-Targeted Vaccines Against COVID-19. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews (2021) 171:164–86. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.01.022

69. Sohrab SS. An Edible Vaccine Development for Coronavirus Disease 2019: The Concept. Clin Exp Vaccine Res (2020) 9(2):164–8. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2020.9.2.164

70. Attwell K, Ward JK, Tomkinson S. Manufacturing Consent for Vaccine Mandates: A Comparative Case Study of Communication Campaigns in France and Australia. Front Communication (2021) 6:598602(20). doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.598602

71. Largent EA, Persad G, Sangenito S, Glickman A, Boyle C, Emanuel EJ. US Public Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates. JAMA Network Open (2020) 3(12):e2033324–e2033324. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33324

72. McKie R. Scientists Urge Caution Over Proposals to Impose Vaccine Passports in UK (2021). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/nov/21/uk-vaccine-passports-scientists-urge-caution.

73. Smith LE, Hodson A, Rubin GJ. Parental Attitudes Towards Mandatory Vaccination; a Systematic Review. Vaccine (2021) 39(30):4046–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.018

74. Chemli S, Toanoglou M, Valeri M. The Impact of Covid-19 Media Coverage on Tourist's Awareness for Future Travelling. Curr Issues Tourism (2020) 25(2):179–86. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1846502

75. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. The COVID-19 Infodemic. Lancet Infect Dis (2020) 20(8):875. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30565-x

76. Dhanani LY, Franz B. The Role of News Consumption and Trust in Public Health Leadership in Shaping COVID-19 Knowledge and Prejudice. Front Psychol (2020) 11:560828(2812). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.560828

77. Lovari A. Spreading (Dis)Trust: Covid-19 Misinformation and Government Intervention in Italy. Media Communication (2020) 8(2). doi: 10.17645/mac.v8i2.3219

78. Chang A, Schnall AH, Law R, Bronstein AC, Marraffa JM, Spiller HA, et al. Cleaning and Disinfectant Chemical Exposures and Temporal Associations With COVID-19 - National Poison Data System, United States, January 1, 2020-March 31, 2020. MMWR Morbidity mortality weekly Rep (2020) 69(16):496–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6916e1

Keywords: COVID-19, vaccination, vaccine fatigue, public health, vaccine communications

Citation: Su Z, Cheshmehzangi A, McDonnell D, da Veiga CP and Xiang Y-T (2022) Mind the “Vaccine Fatigue”. Front. Immunol. 13:839433. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.839433

Received: 20 December 2021; Accepted: 18 February 2022;

Published: 10 March 2022.

Edited by:

Zuben E. Sauna, United States Food and Drug Administration, United StatesReviewed by:

Willy A. Valdivia-Granda, Orion Integrated Biosciences, United StatesIrina V. Kiseleva, Institute of Experimental Medicine (RAS), Russia

Copyright © 2022 Su, Cheshmehzangi, McDonnell, da Veiga and Xiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhaohui Su, c3poQHV0ZXhhcy5lZHU=; Yu-Tao Xiang, eXR4aWFuZ0B1bS5lZHUubW8=

†ORCID: Zhaohui Su, orcid.org/0000-0003-2005-9504

Ali Cheshmehzangi, orcid.org/0000-0003-2657-4865

Dean McDonnell, orcid.org/0000-0001-6043-8272

Claudimar Pereira da Veiga, orcid.org/0000-0002-4960-5954

Yu-Tao Xiang, orcid.org/0000-0002-2906-0029

Zhaohui Su

Zhaohui Su Ali Cheshmehzangi

Ali Cheshmehzangi Dean McDonnell

Dean McDonnell Claudimar Pereira da Veiga

Claudimar Pereira da Veiga Yu-Tao Xiang

Yu-Tao Xiang