95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 14 February 2022

Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.807575

This article is part of the Research Topic Differential Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors due to Age and Sex Factors View all 5 articles

Objective: Several trials have shown that pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy was more effective in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) than chemotherapy monotherapy. However, whether pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy is still a better choice for first-line treatment in elderly patients (≥75 years old) remain unknown. We retrospectively compared the efficacy and safety of these two treatments in elderly patients.

Patients and Methods: We collected data of 136 elderly patients with advanced NSCLC who were treated with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy or chemotherapy monotherapy in our hospital from 2018 to 2020. We compared the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of patients and analyzed which subgroups might benefit more significantly from pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy.

Results: In total population, pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy showed superior PFS and OS than chemotherapy monotherapy (PFS: 12.50 months vs. 5.30 months, P<0.001; OS: unreached vs. 21.27 months, P=0.037). Subgroup analysis showed patients with positive PD-L1 expression, stage IV, good performance score (ECOG-PS <2), fewer comorbidities (simplified comorbidity score <9) or female patients had demonstrated a more evident OS benefit in pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. In terms of safety, the pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy group had higher treatment discontinuation (26% vs. 5%).

Conclusions: Elderly patients using pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy achieved longer PFS and OS, but were more likely to discontinue due to adverse effects, so disease stage, PD-L1 expression, ECOG-PS and comorbidities should be considered when selecting first-line treatment.

In recent years, immunotherapy, represented by PD-L1/PD-1 inhibitors, has developed rapidly, leading to a greatly improved prognosis for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without targetable oncogene alterations (1–4). Previous studies have shown that chemotherapy had immunomodulating effects enhancing the immunogenicity of tumors, thereby increasing the clinical benefit from immunotherapy (5, 6). Based on the Keynote series, Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (P+C) has been approved in China as first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC, regardless of PD-L1 expression (7–9).

It is widely believed that age-related decline of the immune system or immune senescence may lead to poor efficacy of immunotherapy in elderly patients (10, 11). A real-world study in Japan showed that using the same P+C treatment, elderly (≥75 years) patients with NSCLC had significantly shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than younger population (age <75 years) (PFS: HR=2.30 P=0.004; OS: HR=4.58 P<0.001) (12). Thus, our study aimed to explore whether P+C was still the best choice for first-line treatment in elderly patients.

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment in elderly patients and analyzed which subgroups might benefit more significantly.

This is an observational and retrospective study. Elderly patients who met all the following criteria from January 2018 to December 2020 were included. First, they were diagnosed with advanced NSCLC (TNM stage IIIB, IIIC or IV) without targetable oncogene alterations (EGFR/ALK/ROS-1). Second, they received chemotherapy or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment and had complete follow-up data in our hospital.

Baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients, including age, gender, tumor-nodal-metastasis (TNM) stage, performance score (ECOG PS), histology, tumor proportion score (TPS), comorbidity, and treatments were recorded. The simplified comorbidity score (SCS) system was used to classify patients (13), including smoking history, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, respiratory comorbidity, cardiovascular comorbidity, neoplastic comorbidity and alcoholism.

Tumor samples were obtained by tissue biopsy at the time of disease diagnosis. PD-L1 protein expression was detected by the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx assay and calculated by tumor proportion score (TPS), the percentage of viable tumor cells showing partial or complete membrane staining. It was classified into negative (TPS<1%) and positive (TPS≥1%).

The monotherapy group was administered chemotherapy including pemetrexed, gemcitabine, taxanes and vinorelbine, with or without platinum. The combination therapy group was given pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred. Adverse events (AEs) were graded by each physician according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.

Bases on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v1.1), patients were clinically evaluated every 6 to 8 weeks. The objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete or partial response, while the disease control rate (DFS) was defined as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete or partial response or stable disease. Progression-free survival (PFS) is defined as the time from the initiating first-line treatment to the occurrence of disease progression or the last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) is defined as the time from the initiating first-line treatment to death or the last follow-up. The last follow-up time was July 23, 2021.

Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables and continuous variables between groups as appropriate. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used for PFS and OS analysis to compare the prognosis of different groups. Cox proportional hazard models was used for univariable and multivariate analysis to evaluate the variants affecting PFS and OS. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed on the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, Chicago, IL version 22.0).

Among 373 elderly patients diagnosed as advanced NSCLC from January 2018 to December 2020 in our hospital, 212 were tested without targetable oncogene alterations (EGFR/ALK/ROS-1) (Figure 1). After excluding 25 patients receiving best supportive care, 39 receiving other regimens (such as pembrolizumab monotherapy, chemotherapy plus bevacizumab, other immunotherapy) as first-line treatment, and 12 without complete survival data, 136 patients were included in our analysis finally. Among them, 93 patients were treated with chemotherapy monotherapy (CM), while the other 43 cases received pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (P+C).

There was no significant difference between the two groups in age, gender, TNM stage, ECOG-PS, histology, and comorbidity (Table 1). In contrast, there were significantly more PD-L1 positive (TPS ≥ 1%) patients in the P+C group (46% vs. 24%), while patients with PD-L1 negative (TPS < 1%) (28% vs. 34%) and unknown PD-L1 (26% vs. 42%) were more in the CM group.

In chemotherapy monotherapy and combination therapy group, the objective response rate was 29% and 53% (P=0.006), and the disease control rate was 87% and 95%, respectively(P=0.24). Up to the final follow-up, 87 of 93 patients (94%) in CM group and 25 of 43 patients (58%) in P+C group had disease progression on first-line treatment. At the same time, 45 of 93 patients (48%) in CM group and 31 of 43 patients (72%) in the P+C group were still alive.

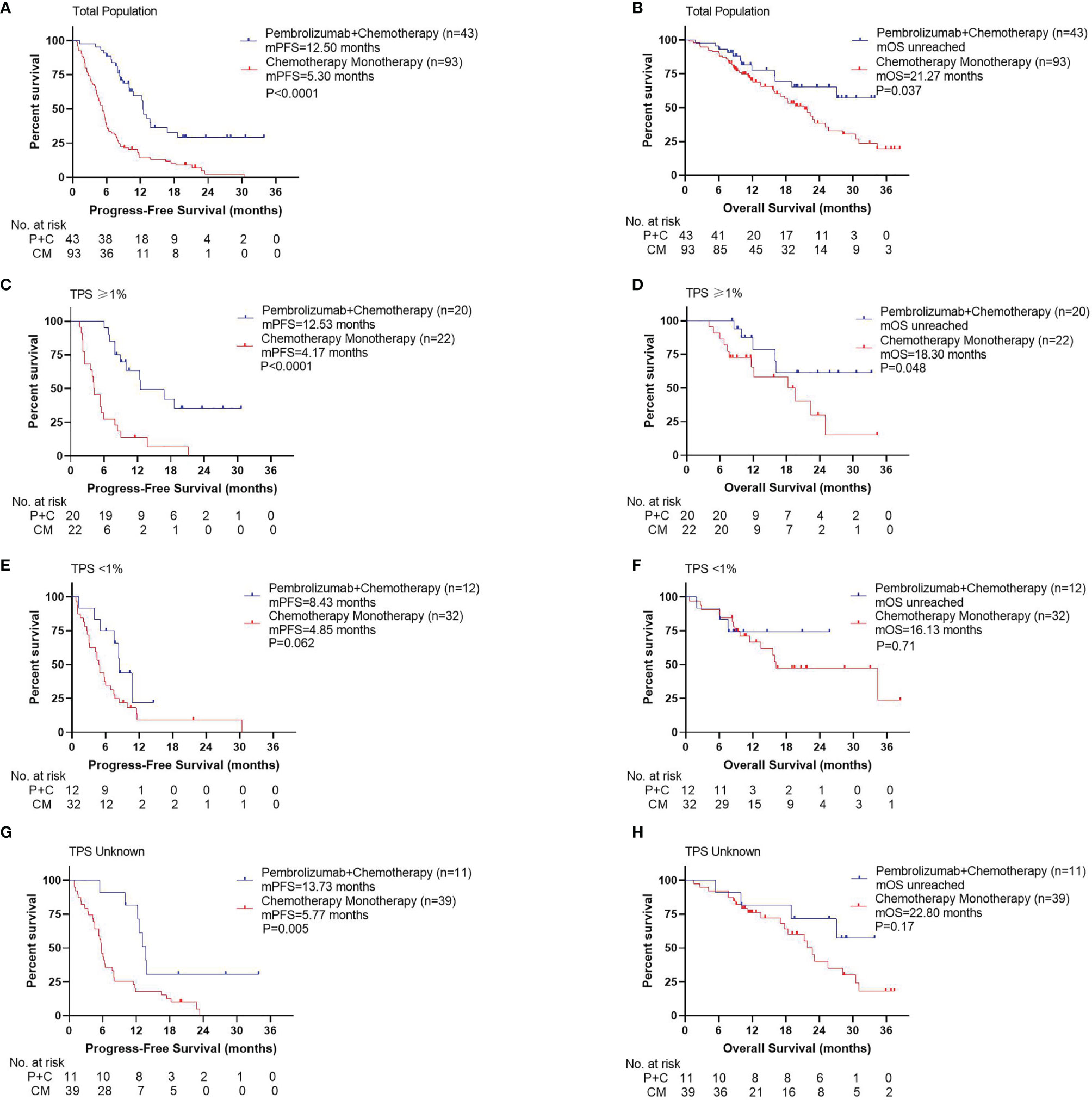

Compared with patients in the CM group, patients in the P+C group had significantly longer PFS (Figure 2A, 12.50 months vs. 5.30 months, P<0.001). OS was also significantly longer in the P+C group (Figure 2B, unreached vs. 21.27 months, P=0.037). In subgroup analysis by PD-L1 TPS, we found that in patients with TPS≥1%, PFS and OS in P+C group were significantly longer than those in CM group (PFS: Figure 2C, 12.53 months vs. 4.17 months, P<0.001; OS: Figure 2D, unreached vs. 18.30 months, P=0.048). However, in patients with TPS<1%, the PFS and OS benefit was not significant in the P+C group (PFS: Figure 2E, 8.43 months vs. 4.85 months, P=0.062; OS: Figure 2F, unreached vs. 16.13 months, P=0.71). In patients with unknown TPS, PFS showed significant difference while OS did not (PFS: Figure 2G, 13.73 months vs. 5.77 months, P=0.005; OS: Figure 2H, unreached vs. 22.80 months, P=0.17).

Figure 2 Survival curves for different treatments. (A) Progression-free survival, (B) Overall survival by treatments of total population. (C) Progression -free survival, (D) Overall survival by treatments of patients with TPS ≥1%. (E) Progression -free survival, (F) Overall survival by treatments of patients with TPS <1%. (G) Progression -free survival, (H) Overall survival by treatments of patients with TPS unknown.

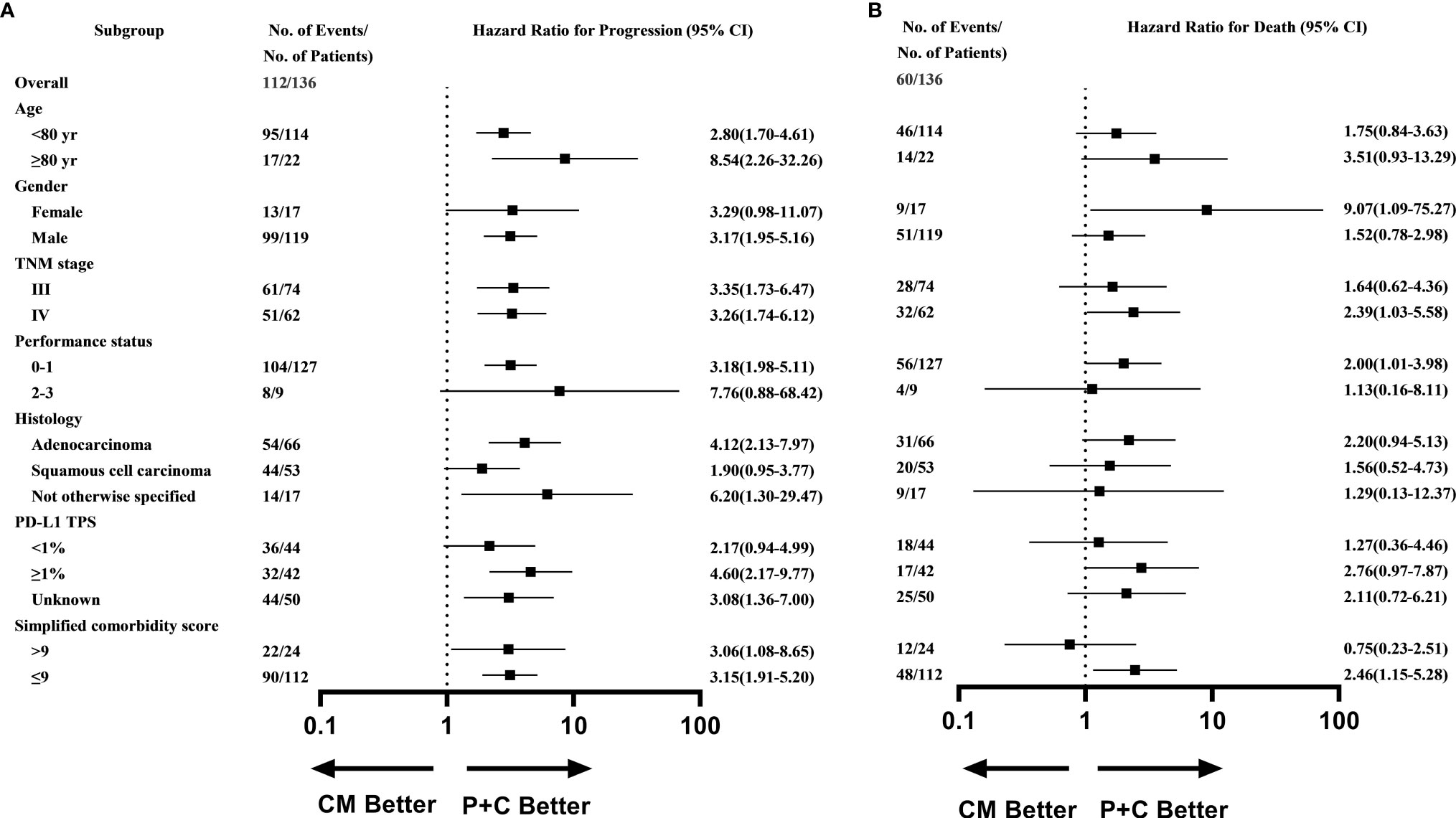

What’s more, subgroup analysis showed that most subgroups could access an evident PFS benefit with P+C (Figure 3A), except for patients with poor performance score (≥2), women, and patients with squamous cell carcinoma. While the subgroup analysis of OS showed that patients with TPS >1% (HR=2.76, 95%CI 0.97-7.87), stage IV (HR=2.39, 95%CI 1.03-5.58), good performance score (ECOG-PS <2) (HR=2.00, 95%CI 1.01-3.98), fewer comorbidities (SCS <9) (HR=2.46, 95%CI 1.15-5.28) or female patients (HR=9.07, 95%CI 1.09-75.27) could benefit more significantly from P+C (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 Subgroup analysis of (A) Progression-free survival (B) Overall survival in P+C and CM groups.

In multivariable analyses, the treatment regimen (PFS: P<0.001, HR=3.34, 95%CI 2.07-5.38; OS: P=0.005, HR=2.62, 95%CI 1.34-5.13) and comorbidities (PFS: P=0.033, HR=1.69, 95%CI 1.04-2.73; OS: P=0.020, HR=2.19, 95%CI 1.13-4.26) had significant effects on both PFS and OS (Table 2). What’s more, elder age (≥80years) (P=0.016, HR=2.17, 95%CI 1.16-4.08) and higher TNM stage (P=0.010, HR=2.01, 95%CI 1.18-3.43) had a negative effect on OS.

We analyzed reasons for discontinuing first-line therapy in two groups (Table 3A). In P+C group, 26% of patients discontinued due to adverse events (AEs) and 44% due to disease progression, compared with 5% and 88% in the CM group, respectively. However, there was no significant difference in deaths due to AEs between the two groups (5% vs. 4%, P=0.93). Of the 11 patients in the P+C group who discontinued due to AEs, 6 were due to pneumonia of any grade and 1 each to thrombocytopenia, myocarditis, hypothyroidism, skin rash and anemia. On the other hand, whether at 3, 6 or 12 months of treatment, more patients remained on first-line treatment in the P+C group than in the CM group.

We then collected adverse events during treatment in two groups (Table 3B). There was no difference in the incidence of serious AEs (grade 3 or higher) between the two groups, which was 67% and 61% in P+C and CM group, respectively (P=0.49). The most common AEs in both groups were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. The incidence of most adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups, except pneumonia (9% vs. 0%, P=0.009) and dyspnea (7% vs. 1%, P=0.093), which were more common in the P+C group.

Supplementary Table 1 listed the secondary therapies initiated in 25 patients of P+C group and 87 patients of CM group after failure of first-line treatments. Best supportive care without second-line therapy was chosen in 12 patients in the P+C group and 19 in the CM group, respectively. A total of 20 CM patients were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in the second line, with or without other treatments; 2 patients in the P+C group underwent immunotherapy re-challenge with nivolumab and 4 received pembrolizumab plus bevacizumab. Anlotinib, an oral small-molecular multi-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was selected by 3 patients in the P+C group and 11 patients in the CM group. Local treatment, including radiotherapy and ablation, was administered in 7 patients.

For patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without targetable oncogene alterations (EGFR, ALK, ROS-1, etc.), chemotherapy used to be the best first-line treatment. However, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), especially those targeting the programmed cell death protein (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1), have revolutionized this situation (1, 4). Several trials have demonstrated the efficacy of pembrolizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC, regardless of tumor PD-L1 expression (7, 8, 14).

The phase 2 KEYNOTE-021 cohort G first showed a higher benefit of P+C compared to chemotherapy monotherapy (CM) in patients with advanced NSCLC (PFS: 24.5 months vs. 9.9 months; OS: 34.5 months vs. 21.1 months) (9). KEYNOTE 189 and KEYNOTE 407 further demonstrated that compared to CM, P+C significantly improved PFS and OS in patients with metastatic non-squamous and squamous NSCLC, respectively (non-squamous: PFS: 9.0 months vs. 4.9 months; OS: 22.0 months vs. 10.7 months; squamous: PFS: 8.0 months vs. 5.1 months; OS: 17.1 months vs. 11.6 months) (7, 8).

Due to the aging population, the incidence of NSCLC in the elderly (≥75 years old) is increasing (15, 16). Nevertheless, elderly patients are often excluded from clinical trials because of their reduced ability to tolerate treatment (e.g., performance score [ECOG PS] ≥2), comorbidities, and potential differences in drug metabolism (17, 18). A recent study showed that elderly patients receiving first-line P+C had significantly shorter PFS and OS than younger patients (PFS: 6.2 months vs. 9.7 months, P= 0.004; OS: 11 months vs. not reached, P<0.001) (19). Elderly patients in our cohort had longer PFS and OS, possibly because there were more stage III patients.

In our cohort, about half of elderly NSCLC patients were PD-L1 negative, and a proportion of patients did not undergo PD-L1 testing. However, the results of subgroup analysis showed no significant difference in OS between these patients using P+C and CM. Meanwhile, some subgroups, including male patients, patients with stage III, PS score ≥2, squamous cell carcinoma and undetermined pathology, simple comorbidity score > 9, did not benefit significantly from P+C. This might be related to the small sample size of our study, but it also reflected that P+C was more suitable for elderly patients with metastatic disease or a better performance status.

Safety was another topic of concern for elderly patients. Age-related physiological changes and comorbidities may increase treatment-related toxicities and reduce tolerance to therapy (20, 21). Compared with chemotherapy, pembrolizumab monotherapy was associated with fewer treatment-related AEs and fewer discontinuations (4, 22, 23). Subgroup analysis of elderly patients showed advanced age was not associated with increased toxicity with pembrolizumab (24). For P+C, data from clinical trials showed patients could benefit from the combination therapy without additional toxicity compared to CM (7, 8). In this study, the discontinuation rate in elderly patients (26%) was slightly higher to that of general population in previous studies (16.2% in Keynote407, 17% in Keynote021-G) (8, 9), possibly because AEs had a more significant impact on quality of life and treatment, leading to higher discontinuation of treatment even when no serious toxicity occurred (12, 25).

Our research has the following limitations. First, as a retrospective single-center study, loss of follow-up and selective bias in the treatment were inevitable. However, patients were enrolled consecutively and adjusted using multivariable analysis to reduce the bias. Second, because AEs were only collected from medical records, we simply analyzed AEs of grade 3 or higher. Further studies are needed to analyze the safety of P+C in elderly patients in more detail.

In conclusion, our study evaluated first-line therapy for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC without targetable oncogene alterations. Elderly patients using P+C were more likely to discontinue due to adverse effects, so disease stage, PD-L1 expression, performance score and comorbidities should be considered when selecting first-line treatment.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by institutional review board of Shanghai Chest Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ZY, YC, and YW all have substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, the collection and analysis of data, the writing and edit of the article. The rest authors have given substantial contributions to the work by providing editing and writing assistance. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the foundation of Shanghai Chest Hospital (Project No. YJXT20190102); the program of system biomedicine innovation center from Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Project No. 15ZH4009); Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Project No. 15ZH1008) and the foundation of Chinese society of clinical oncology (Project No. Y2019AZZD-0355).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thanks to all patients and their families for their contributions to this research.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.807575/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Treatments after disease progression in different treatment groups.

1. Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, et al. Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2015) 373(17):1627–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643

2. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, et al. Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2015) 373(2):123–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627

3. Fehrenbacher L, von Pawel J, Park K, Rittmeyer A, Gandara DR, Ponce Aix S, et al. Updated Efficacy Analysis Including Secondary Population Results for OAK: A Randomized Phase III Study of Atezolizumab Versus Docetaxel in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2018) 13(8):1156–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.039

4. Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, et al. Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2016) 375(19):1823–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774

5. Kersten K, Salvagno C, de Visser KE. Exploiting the Immunomodulatory Properties of Chemotherapeutic Drugs to Improve the Success of Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol (2015) 6:516. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00516

6. Galluzzi L, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunological Mechanisms Underneath the Efficacy of Cancer Therapy. Cancer Immunol Res (2016) 4(11):895–902. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0197

7. Gadgeel S, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Speranza G, Esteban E, Felip E, Domine M, et al. Updated Analysis From KEYNOTE-189: Pembrolizumab or Placebo Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum for Previously Untreated Metastatic Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38(14):1505–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136

8. Paz-Ares L, Vicente D, Tafreshi A, Robinson A, Soto Parra H, Mazieres J, et al. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Patients With Metastatic Squamous NSCLC: Protocol-Specified Final Analysis of KEYNOTE-407. J Thorac Oncol (2020) 15(10):1657–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.06.015

9. Awad MM, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, Patnaik A, Yang JC, Powell SF, et al. Long-Term Overall Survival From KEYNOTE-021 Cohort G: Pemetrexed and Carboplatin With or Without Pembrolizumab as First-Line Therapy for Advanced Nonsquamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol (2021) 16(1):162–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.09.015

10. Elias R, Karantanos T, Sira E, Hartshorn KL. Immunotherapy Comes of Age: Immune Aging & Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Geriatr Oncol (2017) 8(3):229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2017.02.001

11. Daste A, Domblides C, Gross-Goupil M, Chakiba C, Quivy A, Cochin V, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Elderly People: A Review. Eur J Cancer (2017) 82:155–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.044

12. Wozniak AJ, Kosty MP, Jahanzeb M, Brahmer JR, Spigel DR, Leon L, et al. Clinical Outcomes in Elderly Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results From ARIES, a Bevacizumab Observational Cohort Study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) (2015) 27(4):187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.12.002

13. Colinet B, Jacot W, Bertrand D, Lacombe S, Bozonnat MC, Daures JP, et al. A New Simplified Comorbidity Score as a Prognostic Factor in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients: Description and Comparison With the Charlson's Index. Br J Cancer (2005) 93(10):1098–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602836

14. Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Patnaik A, Powell SF, et al. Carboplatin and Pemetrexed With or Without Pembrolizumab for Advanced, Non-Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomised, Phase 2 Cohort of the Open-Label KEYNOTE-021 Study. Lancet Oncol (2016) 17(11):1497–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30498-3

15. Nakamura K, Ukawa S, Okada E, Hirata M, Nagai A, Yamagata Z, et al. Characteristics and Prognosis of Japanese Male and Female Lung Cancer Patients: The BioBank Japan Project. J Epidemiol (2017) 27(3S):S49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.12.010

16. Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin (2019) 69(5):363–85. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565

17. Pang HH, Wang X, Stinchcombe TE, Wong ML, Cheng P, Ganti AK, et al. Enrollment Trends and Disparity Among Patients With Lung Cancer in National Clinical Trials, 1990 to 2012. J Clin Oncol (2016) 34(33):3992–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.7088

18. Sacher AG, Le LW, Leighl NB, Coate LE. Elderly Patients With Advanced NSCLC in Phase III Clinical Trials: Are the Elderly Excluded From Practice-Changing Trials in Advanced NSCLC? J Thorac Oncol (2013) 8(3):366–8. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827e2145

19. Morimoto K, Yamada T, Yokoi T, Kijima T, Goto Y, Nakao A, et al. Clinical Impact of Pembrolizumab Combined With Chemotherapy in Elderly Patients With Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer (2021) 161:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.08.015

20. Dawe DE, Ellis PM. The Treatment of Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the Elderly: An Evidence-Based Approach. Front Oncol (2014) 4:178. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00178

21. Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, Mohile SG, Muss HB, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Improving the Evidence Base for Treating Older Adults With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement. J Clin Oncol (2015) 33(32):3826–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0319

22. Mok TSK, Wu YL, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho BC, Turna HZ, et al. Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Previously Untreated, PD-L1-Expressing, Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (KEYNOTE-042): A Randomised, Open-Label, Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet (2019) 393(10183):1819–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7

23. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab Versus Docetaxel for Previously Treated, PD-L1-Positive, Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet (2016) 387(10027):1540–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7

24. Nosaki K, Saka H, Hosomi Y, Baas P, de Castro G Jr., Reck M, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Pembrolizumab Monotherapy in Elderly Patients With PD-L1-Positive Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Pooled Analysis From the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 Studies. Lung Cancer (2019) 135:188–95. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.07.004

Keywords: pembrolizumab, chemotherapy – oncology, non-small-cell lung cancer, first line therapy, elderly patients

Citation: Yang Z, Chen Y, Wang Y, Hu M, Qian F, Zhang Y, Zhang B, Zhang W and Han B (2022) Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Monotherapy as a First-Line Treatment in Elderly Patients (≥75 Years Old) With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Immunol. 13:807575. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.807575

Received: 02 November 2021; Accepted: 24 January 2022;

Published: 14 February 2022.

Edited by:

Pei Pei Chong, Taylor’s University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Yang Xiao, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Yang, Chen, Wang, Hu, Qian, Zhang, Zhang, Zhang and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baohui Han, MTg5MzA4NTgyMTZAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Wei Zhang, emh3ZWkyMDAyQDEyNi5jb20=; Bo Zhang, emIxMDYzMjUzMDc4QDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.