- 1Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Surrey, Guildford, United Kingdom

- 2Graduate Institute of Biomedical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan

- 3Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects primarily macrophages in the lungs. Infected macrophages are surrounded by other immune cells in well organised structures called granulomata. As part of the response to TB, a type of macrophage loaded with lipid droplets arises which we call Foam cell macrophages. They are macrophages filled with lipid laden droplets, which are synthesised in response to increased uptake of extracellular lipids, metabolic changes and infection itself. They share the appearance with atherosclerosis foam cells, but their lipid contents and roles are different. In fact, lipid droplets are immune and metabolic organelles with emerging roles in Tuberculosis. Here we discuss lipid droplet and foam cell formation, evidence regarding the inflammatory and immune properties of foam cells in TB, and address gaps in our knowledge to guide further research.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). TB mortality rates increase with weaker immune systems caused by comorbidities such as diabetes, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), smoking, alcohol consumption, and undernutrition (WHO, Global Tuberculosis report 2020). TB is one of the deadliest diseases worldwide, especially in developing countries in communities with low income and poor nutrition. The WHO predicted that COVID will lead to a new TB crisis and anticipates an increase in TB deaths worldwide due to late diagnosis and treatment during peaks of the pandemic.

Macrophages are crucial in the response to Mtb and have the main role of containing and killing the pathogen. The main cytokine associated with Mtb killing and macrophage activation is IFN-γ. Other prototypic inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, and the inflammasome regulated IL-1β and IL-18 are also associated with macrophage responses to Mtb. Despite activation programmes, Mtb infects and kills many macrophages, and the pathogen survives inside death resistant macrophages, which are not well defined. Mtb utilises several strategies to persist inside macrophages. For example the pathogen inhibits phagolysosome maturation and acidification by stopping translocation of enzymes, inhibition of lysosomal enzymes, and by depleting calcium and hydrogen ions required for the fusion of the lysosome with the phagosome (1).

Mtb infected macrophages orchestrate a pro-inflammatory response leading to granuloma formation. Through TLR and pattern recognition receptor mediated activation (2), Mtb also alters inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress, inducing various forms of cell death and autophagy (1). Thus, cell death and abundant cellular material are hallmarks of the Mtb infection. Foam cells represent a predominant macrophage phenotype observed in TB granulomata surrounding necrotic material.

Foam cell appearance is due to the presence of lipid droplets in the cytoplasm, which grow and are consumed by the cells, as required. Lipid droplets are numerous in macrophages, similar to droplets in brown and beige adipose tissue. TB foam cells share similarities with macrophages that appear in other lipid disorders such as atherosclerosis (also termed foam cells), but their contents in TB are predominantly triglycerides and not cholesterol. The link between this lipid rich profile and the conventional IFN-γ Th1-macrophage response necessary to control Mtb, is ill defined.

Granulomata (plural of granuloma) are organised cellular foci that contain infected macrophages, granulocytes and T lymphocytes, encased by a fibrotic ring. In vivo, the various stages of granuloma include nascent, caseous, fibrocaseous and resolved states. Despite such variety, granulomata are always dominated by macrophages. Granulomata with a Th1/M1-like profile have been proposed to control the disease, whereas a Th2/M2 rich profile is associated with exacerbation (3). TB foam cells are predominant features of advanced mycobacterial granulomata associated with caseation. The caseum contains an abundance of triacylglycerols, cholesterol, cholesteryl esters and lactosylceramide, which derive mainly from dead cells (4), becoming the predominant component of foam cells themselves.

Using TB+ human lymph node samples, Peyron et al. showed that foam cells are always close to the necrotic core with a strong correlation, and appear infected by Mtb, as confirmed by Ziehl-Neelson acid-fast bacilli (AFB) positive staining of tissue sections (5). In vitro, using PBMC activation assays, they found that Mtb and Mycobacterium avium, but not Mycobacterium smegmatis, induce foam cell formation, ascribed to the presence of Mycolic acids. However, the mechanism of foam cell formation and the nature of the lipids driving this process are not clear since they did not demonstrate reproducible Mtb replication in foam cells, and in bulk. They also showed bacteria inside large lipid droplets by electron microscopy, but the data need further verification due to the fusion of lipids in processing samples for EM, and the challenge of studying subcellular events with pathogenic bacteria.

We can learn from atherosclerosis and adipose tissue research, since lipid droplet proteins and mechanisms are somewhat conserved. Progression of granulomata to caseation is associated with upregulation of lipid handling proteins such as ADFP, required for droplet formation, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member (ACSL1), involved in the de novo triglyceride synthesis pathway and the membranous lysosomal protein Saposin C (SapC), required to remodel the droplets (4). These three proteins involved in lipid metabolism were highly expressed in caseous and fibrocaseous granulomata. SapC was markedly positive in nascent granulomata, whereas ADFP was more prevalent in the foamy macrophage-rich centre of advanced disease, pointing to accumulation of lipid laden foam cells in granuloma formation, over time (4). LTA4H, which synthesises the proinflammatory mediator LTB4, is also highly expressed in the ring of foam cells. The interconversion between macrophages and foam cells and the migration and distribution of macrophages within granulomata deserve further scrutiny.

Biochemical Pathways Leading to Foam Cell Formation in TB

The main requirement for lipid droplet formation is the increase in neutral lipids in the cell. For uptake of exogenous lipid particles such as lipoproteins and fatty acid complexes, macrophages are equipped with a variety of receptors including scavenger receptors CD36, SR-A1, and SR-B1, the oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX-1), Macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO), the Fatty acid transport protein 1 (FATP1) and Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) (6). The interaction of macrophages with necrotic and apoptotic debris involves a distinct type of immune phagocytic synapse. Intracellular trafficking of fatty acid is supported by another group of proteins including the fatty acid binding proteins, FABP4 and FABP5 (7). CD36 is of particular interest due to its regulation and its role in the recognition of cellular debris, apoptotic cells, and oxidized LDL (oxLDL) (8, 9).

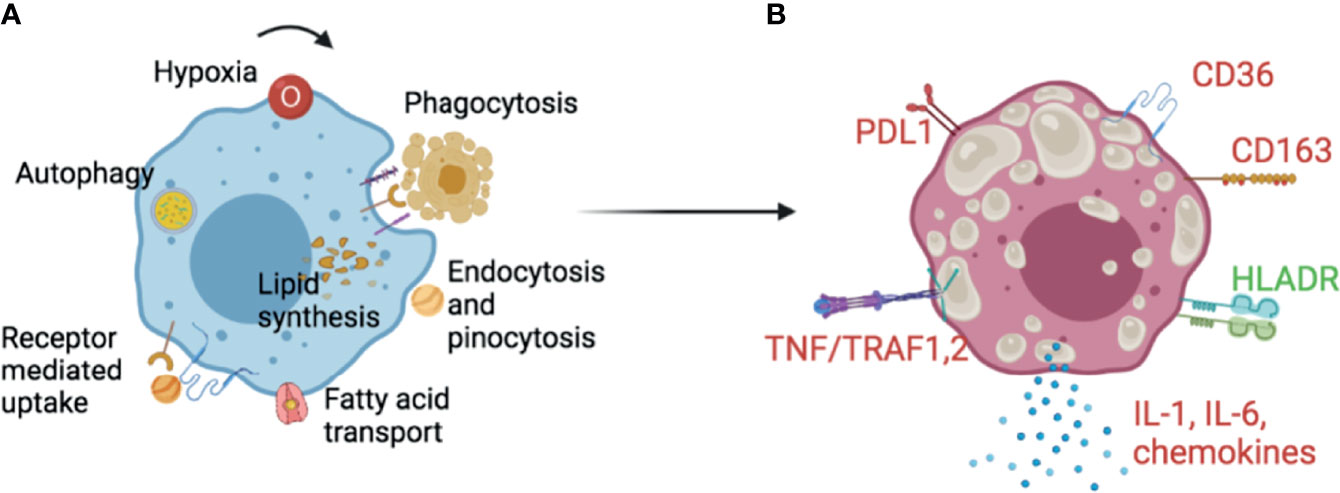

Lipid droplets accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum as the neutral lipid content between leaflets of the ER membrane reaches a high concentration (10). Triglycerides and their components need to be synthesised in order for cells to accumulate lipid droplets in TB. Fatty acids are synthesized de novo or more likely, incorporated from the extracellular space, e.g. by lipolysis of lipoproteins and dead cell debris, Figure 1A. The process is actively controlled by multiple isoforms of lipid enzymes and accessory proteins reviewed in detail in (11). Internalised complex lipids are degraded to fatty acids by the action of lysosomal acid lipases (LAL) in phagolysosomes (6). Lipophagy degrades particles by various hydrolases into basic components such as amino acids, glucose, nucleotides and free fatty acids (12, 13). Engulfment of lipids from necrotic cells induces triacylglyceride (TAG)- enriched lipid droplets, whereas inhibition of necrosis by the oxidation inhibitor IM54 prevents lipid droplet accumulation. The source of lipid is mainly esterified-lipid of necrotic cells, first degraded by lysosomes then mobilised into TAG, since inhibition of lysosomal lipases by chlorpromazine (CPZ) prevents the transfer of labelled fatty acids of necrotic cells into the TAG of recipient cells (14). Figure 1B provides an overall picture of foam cell markers with high scavenger receptors CD36, CD163, TNF receptors and T cell response inhibitors, and decreased HLADR expression.

Figure 1 Foam cells in TB. (A) Lipid droplet synthesis in macrophages can be triggered by external and internal stimuli. Extrinsic complex sources of lipids include phagocytosis of apoptotic or necrotic cells, or endocytosis, pinocytosis and receptor mediated uptake of lipoproteins. Simpler fatty acids can be transported by specialised machineries in the cell. Lysosomal activity and autophagy contribute to the degradation of accumulated lipid remnants in the cell to avoid lipotoxicity. Cytokines, hormones, growth factors and metabolic changes such as variations of glucose level, induce enzymes and proteins important for lipid synthesis and droplet stability. (B) Although there is no consensus, some markers appear repeatedly in Foam cell literature. Foam cells have been shown to have increased scavenger receptors- CD36, CD163, TNF-α/TRAF1,2, the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and the inflammasome dependent IL-1β. The checkpoint inhibitor PDL1 has been shown as increased while the antigen presentation related HLA-DR as decreased. Upregulated markers are colour coded in red and downregulated in green. These and other markers can guide needed translational histological studies on foam cells in multiple species and cell line models. It is early to ascertain the true nature of foam cells in TB, and more research in primary models is necessary since THP1 and primary macrophages behave differently. See text for references.

Triacylglyceride synthesis (TAG) requires de novo fatty acid production from cytosolic citrate. This step is produced by the Krebs cycle from oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA by citrate synthase (CS) and exported from mitochondria through the citrate carrier (CIC). Citrate is broken down by the ATP-citrate synthase-(ACLY), to oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA which is then used as a substrate for fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis (15). The Fatty Acyl Co-A synthetase (ACS) catalyses the formation of a thioester bond between a fatty acid and coenzyme-A to form fatty Acyl Co-A. Through the successive enzymatic actions of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT), 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase (AGPAT) and phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAP), fatty Acyl Co-A is esterified with Glycerol-3-phosphate to form Diacylglycerol (DAG). In the final step, DAG is esterified to TAG by the Acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferases-(DGAT1) and (DGAT2). DGAT1 is exclusively in the ER as a dimer or tetramer form, whereas DGAT2, in addition to the ER, localizes in droplets directly, as well as in mitochondria. DGAT1 preferentially uses exogenous FA while DGAT2 uses fatty acids of both exogenous and endogenous origin (16).

Specific to Mtb infection and inspired by the strong association between foam cells and necrotic areas, Jaisinghani et al. investigated the role of necrotic mixtures and their impact on inflammation, over all. In guinea pigs, they found foam cells close to necrotic areas and enrichment of the expression of TNF-α, in situ. In vitro, overexpression of DGAT1 in human THP1 cells lead to lipid droplet formation. Knockdown of DGAT1 by shRNA, lead to a decrease in TAG level with a concomitant decrease in quantity and size of lipid droplets in THP1 cells (14). Furthermore, inhibition of DGAT1 by its inhibitor T863 established in (17), precluded lipid droplet formation in IFN-γ activated and Mtb infected bone marrow derived mouse (BMDM) and human macrophages (18). Surprisingly, the key step controlled by fatty acid synthase (FASN), was downregulated in IFN-γ activated and Mtb infected macrophages. However, this did not affect droplet formation, which suggests that TAG synthesis and not the de novo synthesis of fatty acid is a major contributor to lipid droplets in Mtb infected macrophages (18).

Acetyl-CoA levels are also regulated by the rate-limiting enzymes Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC1 and ACC2). ACC1 is cytosolic and regulates de novo fatty acid synthesis, while ACC2 is mitochondrial and is involved in fatty acid oxidation. De novo fatty acid synthesis has been shown to be increased in Dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages in response to M bovis BCG, but in this model ACC1 or ACC2 inhibition in murine DCs and macrophages was not required to control infection (19). In CRISPR/Cas9 knock down experiments performed on ACC1 and ACC2 in BLaER1 cells (a human B and macrophage-like cell line), inhibition lowered foam cell formation and TAG levels in infected macrophages, while enhancing mitochondrial activity and limiting Mtb-induced necrotic cell death of macrophages (20). Mtb growth in ACC2, but not in ACC1 deficient cells was reduced compared to wild-type cells.

Of interest, Brandenburg et al. recently described an association between ACC2 and the Wnt family member 6 (WNT6). Immunohistochemical staining of human TB infected lung showed colocalized expression of WNT6 which correlated with Oil Red O signal. A similar colocalization was observed in the infected lungs of IL-13- overexpressing mice. WNT6- supported ACC2 activity increased intracellular TAG levels and Mtb survival in macrophages. A combination of ACC2 inhibitors with isoniazid improved the clinical outcome and reduced Mtb dissemination in mouse models of infection (20).

Although Foam cells in TB are predominantly TG rich, there are other components which are essential for any cellular membranes or droplet. Cholesterol esters are another component of droplets, generated by acyl-CoA: cholesterol O-acyltransferase (ACAT1 and ACAT2). The role of both enzymes is to process free cholesterol, derived from the diet or from endocytosed complex particles. ACAT1 and ACAT2 deficiency causes ER stress due to excess cholesterol (21, 22). ACAT1 is ubiquitous and abundant in macrophages, while ACAT2 is mainly expressed in hepatocytes and enterocytes in liver and intestine in the steady state (23). Both enzymes ACAT1 and ACAT2 are regulated by monocyte maturation into macrophages (24). ACAT2 positive macrophages appear in skin TB and sarcoidosis, among other pathologies (24). Recently, Genoula et al. found increased expression of CD36 and ACAT1 in human monocyte derived foam cells developed after exposure to TB-Pleural Effusions. This effect was IL-10 dependent (25). IL-10 activated STAT3 in these cells, which also bore high bacillary loads and showed an immunosuppressive phenotype as demonstrated by decreased production of TNF-α (25). We postulate that the inflammatory potential of foam cells might be a spectrum regulated by differences in TG and cholesterol accumulation.

Foam Cells in TB Inflammation

Mtb interacts with a variety of macrophage receptors. Mycolic acids do not seem to form the bulk of the lipids of the foam cell, but they may play a role in foam cell formation and function by regulating lipid-related genes downstream of TLR and scavenger receptor pathways. For example, TLR2, CD14 and MARCO are required for murine and human macrophage cytokine responses to mycobacterial trehalose dimycolate and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2). Mtb mannose-lipoarabinomannan (Man-LAM), lipomannan (LM), and mannosylated glycoproteins also interact with C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) such as Dectin-1, Mannose receptor, and DC-SIGN. Intracellular Nod-like receptors (NLRs) also participate in Macrophage recognition within the innate response to Mtb, reviewed in (26). Engagement of all these receptors can induce activation of intracellular kinases and of NF-kB and other inflammatory transcription factors, as well as lipid related PPAR receptors, leading to cell death and inflammation or survival and persistence, involving inflammatory cytokines and lipid related proteins.

An interesting autocrine loop mediated by TLR2 controls lipid droplet formation and TNF-α secretion by BCG-infected mouse peritoneal macrophages (27, 28). TLR2 stimulation by BCG triggers expression and activation of PPARγ and NF-kB. Inhibition of PPARγ by GW9662 inhibits droplet biogenesis, while inhibition of NF-kB by JSH-23 does not have any effect on lipid droplet accumulation (28). PPARγ- dependent lipid droplet accumulation depends on cooperation between TLR2 and CD36 with disruption resulting in the reduction of lipid droplets (28). Competition between the bacterium and the lipid ligands for CD36 and MARCO may bring about special signalling in foam cells, hitherto undefined.

Cytokines such as TNF-α act in an auto- and paracrine manner to promote droplet formation in Mtb infected human macrophages. TNFα recognition at the cell surface activates mTORC1 (mTOR complex 1) and caspase 8, which enhance lipid droplet formation by inhibition of lipophagy, promotion of mitochondrial dysfunction, and by activation of SREBP involvement in TAG synthesis (29). Furthermore, IL-10 in TB-PE promotes foamy phenotype in macrophages by activating STAT 3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) which in turn upregulates the expression of ACAT, leading to cholesterol accumulation in lipid droplets (25). Additionally, foam cells also show enhanced expression of CD36, required for the import of extracellular lipid.

In vitro, using human monocyte derived macrophages, we found that foam cell formation prevented cells from dying. This may be due to activation of inflammasome versus death pathways in foam cells. In THP1 cells, which are more resistant to infection than primary macrophages, foam cells displayed an increased production of inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and an increased IL-1β/IL-10 ratio, compared with macrophages. Increased TNF-α secretion in response to Mtb infection of oleic acid-derived-THP-1-foam cells, involved the NF-κB pathway (30).

Foam cells can function as factories of inflammatory eicosanoids, producing arachidonic acid (AA)- derived eicosanoids such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, thromboxanes, lipoxins, and related oxygenated lipid species, pro- or anti-inflammatory in nature. They can also produce resolvins and the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory lipid mediators influences the outcome of infection. Lipid droplets are sites for many of the AA enzymes including cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases. Specific GPCRs (G protein coupled receptors) sense these inflammatory lipids which act in a paracrine or autocrine manner. Examples include receptors for prostaglandin E2 and D2, leukotriene B4 and lipoxin (31). Fatty acids and leukotriene B4 bind directly to PPARα and PGJ2. Some derivatives of HETE bind PPARγ and modulate their effect on lipid metabolism (32). During Mtb infection, it has been demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition by both mepenzolate bromide (MPN) or siRNA, mediated reduction of GPR109A in THP-1 macrophages, resulting in less droplet formation and reduced bacterial loads (33). Infection of macrophages with Mtb or activation by ESAT-6, a virulence factor of Mtb, induces ketone body formation. Acetyl Co-A can be metabolised into 3HB (D-3-hydroxybutyrate) which activates GPR109A in a paracrine or autocrine manner to promote lipid droplet accumulation by exerting an antilipolytic effect (33). Fatty acids, intermediates of TAG synthesis such as diacylglycerol (DAG) and monoacylglycerol (MAG), acyl-coenzyme A and phosphatidic acid, are all potential signalling molecules in immunity (34).

Final Considerations and Conclusions

The designation “foam cells” covers a range of storage, genetic, metabolic, inflammatory and infectious conditions. In this review we briefly covered the lipid content and metabolism associated with macrophage foam cells in TB. The roles of lipids in pathogenesis of florid, subclinical and latent disease are still poorly defined, nor do we have insights into their contribution to the hallmarks of granuloma formation such as Langhans giant cell formation, macrophage inflammasome and antimicrobial activation, epithelioid cell transformation and the induction of life threatening systemic acute and chronic inflammatory syndromes.

This review sets the stage for further studies of lipid metabolism in TB by temporal and spatial analysis of single cell gene expression in situ, exemplified by the recent publication by Russell and colleagues where both susceptibility of the macrophage to infection and the metabolic state of the bacterium were used as important variables in a single cell RNAseq study (35). Combined with the resurgence of interest in immunometabolism, the availability of human and experimental material will transform our understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms at play, the basis for improved therapy. To date the most convincing data emerge from studies that address human pathology, thus more efforts at obtaining samples should be made worldwide.

It remains to establish whether foam cell formation is a beneficial host response to Mtb infection, or another of the mechanisms Mtb uses to survive inside the cells by controlling their metabolic environment. Numerous studies suggest that Mtb can access host TAG and sequester it in the form of intracytoplasmic lipid inclusions (ILI) during persistence, as a source of carbon and energy (36, 37). Moreover, Mtb can also metabolize host membrane cholesterol for energy production and to maintain microbial cell wall components during persistence in IFN-γ activated macrophages, as in chronic animal models of infection (38).

A red flag arises when we see that for host lipid acquisition, Mtb upregulates many genes involved in lipid metabolism including Tgs-1, Ppe4- a perilipin like protein- involved in TAG synthesis, and Mce1, Mce4, LucA, OmamB, Mce1D, MceG, and rv0966c-, contributing to lipid import (36, 38–42). Mtb itself also expresses many genes involved in lipid hydrolysis such as lipY, Msh1, lipF, lipH, lipJ, lipK, lipN, lipV, lipX, lipY, culp5, culp7, and culp6, which may contribute to the breakdown of host lipid (40, 43, 44). Studies indicate that apart from using lipid as energy source, Mtb also utilises lipid for the synthesis and maintenance of its cell wall, largely consisting of lipids including mycolic acid, phiocerol-dimycoseroic acid, poly-acylated trehaloses and sulfolipids (37, 45).

The reason why only some macrophages undergo foam cell formation in the same environment where other macrophages differentiate towards epithelioid and giant cells, is unknown. To date there is no information about the developmental origin of foam cells in Mtb and the fact that foam cells form in many locations in the body would suggest a general tissue macrophage property or a feature of recruited blood monocytes in particular. In the lungs of TB patients, foam cells could originate from alveolar, interstitial, or recruited monocyte-derived macrophages, or specific subsets of these. The cell- specific phenotype, not necessarily their origin, was implicated by Ordway et al. who showed high expression of DEC-205 and TRAF1,2, 3, (TNFR-associated factors) in foam cells, the latter associated with resistance to apoptosis (46). Further research into the origin of foam cells in the lung and lymph nodes will be important.

There are reports which demonstrate that infected foam cells can leave the alveoli and reach the upper bronchus by the propelling movement of mucus, from where they can be swallowed or expectorated (47), thus facilitating Mtb dissemination and spread. During regression of atherosclerosis, foam cells may acquire characteristics of DC, shown by upregulated expression CCR7 allowing them to migrate to lymph nodes (48). In post-primary TB showing extensive lipid pneumonia, infected foam cells are prominent in exudates from disrupted granulomata, as well as in the lung alveoli, and Mtb organisms are found in close association with lipid droplets (5, 49).

Proteomic analysis of granulomata is also highly informative. Colocalization of LTA4H with TNFα predominantly in the marginal area of caseum suggests a strong association of these factors in inflammation and tissue necrosis (50). LTB4 and enzymes ALOX5, ALOX5AP, and LTA4H were more pronounced in the caseum, as well as in the cells adjacent to the caseum. Their expression diminished as the distance from the necrotic centre increased. They further observed that prostanoids and COX1 and COX2 were prominently located in the surrounding cells and less prevalent in the necrotic core. Establishing co-expression of lipid handling molecules, with lipid droplet positive macrophages, and the balance of pro and anti-inflammatory lipids in the foam cell reaction to Mtb, will be important. Development of proteomics and lipidomics applied to TB, will help this subject to progress. The main challenge for now is developing robust human and humanised models that enable investigators to extract and work with these labile cells, developing phenotypic markers for their characterization in combination with infection readouts to establish bona fide Foam cell functions.

Author Contributions

PA, SG, and FM wrote the manuscript. PA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FM revised the manuscript and edited. SG edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

3HB, D-3-hydroxybutyrate; AA, Arachidonic acid; ACAT1,2, Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 and 2; ACC1, 2, Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 and 2; ACLY, ATP-citrate synthase; ACS, FattyAcylCo-A synthetase; ACSL1, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 1; ADFP or ADRP, Adipose Differentiation-Related Protein, aliases for Perilipin 2 PLIN2; AFB, Acid-fast bacilli; AGPAT, 1-acyl glycerol-3-phosphate O-acyl transferase; ALOX5, Arachidonate 5-Lipoxygenase; ALOX5AP, Arachidonate 5-Lipoxygenase Activating Protein; BCG, Bacille Calmette-Guerin; BLaER1, B-cell-derived human cancer cell line; BMDM, Bone marrow derived macrophages; Cas9, CRISPR-associated protein 9; CCTα, Phosphate Cytidylyltransferase 1A, Choline, PCYT1A; CD14, CD14 molecule; CD163, CD163 molecule; CD206, CD206 molecule, Mannose receptor; CD36, CD36 molecule; CIC, Citrate carrier SLC25A1 Gene; cKO, Conditional Knockout; COX1, Cyclooxygenase 1, PTGS1 prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1; COX2, Cyclooxygenase 2, PTGS2prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1; cPLA2, Cytosolic Phospholipase A2, PLA2G4A Gene Phospholipase A2 Group IVA; CRISPR, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; CS, Citrate synthase; culp5, Probable carboxylesterase Culp5; culp6, Carboxylesterase/lipase Culp6; culp7, Probable carboxylesterase Culp7; DAG, Diacylglycerol.; DCs, Dendritic cells; DEC-205, LY75 Gene; DGAT1,2, Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 1 and 2; ER, Endoplasmic reticulum; FA, Fatty acid; FABP3,4,5 7, Fatty acid binding protein 3, 4, 5 or 7; FASN, Fatty acid synthase gene; FATP1, Fatty acid transport protein 1; GPAT, Glycerol-3-phosphate acyl transferase; GPCRs, G Protein coupled receptors; GPR109A, Hydroxycarboxylic Acid Receptor 1 HCAR1; GTP, Guanosine triphosphate; GW9662, Antagonist of PPARgamma; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HETE, Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids; HIF-1a, Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 Subunit Alpha; Hig-2, Hypoxia Inducible Lipid Droplet; HLADR, Human Leukocyte Antigen – DR, isotype; IFNγ, Interferon Gamma; IM54, Necrosis inhibitor; ILI, Intracytoplasmic lipid inclusions; JSH-23, Inhibitor of NF-κB transcriptional activity; KO, Knockout; LAL, Lysosomal acid lipases; lipF, Carboxylesterase LipF; lipH, Lipase LipH; lipJ, Probable lignin peroxidase LipJ; lipK, Hydrolase LipK; lipN, Carboxylic ester hydrolase LipN; lipV, Lipase LipV; lipX, Lipase LipX; lipY, Lipase LipY; LOX-1oxidized, Low-density lipoprotein receptor1; LPL, Lipoprotein lipase; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; LTA4H, Leukotriene A4 Hydrolase; LTB4, Leukotriene B4; LucA, Rv3723/LucA integrates cholesterol and fatty acid uptake; MAPK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase; Marco, Macrophage receptor with collagenous structure; Mce1, Mce protein 1; Mce1D, Mce-family protein Mce1D; Mce4, Lipoprotein LprN; MceG, Putative ATPase subunit Rv0655/MceG; MPN, Mepenzolate bromide; MAG, Monoacylglycerol; Msh1, Mycobacterial secreted hydrolase 1; Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Mtb, ESAT-6; mTORC1, mTOR complex 1; Myd88, Myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NF-Kb, Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; OmamB, Putative components of the Mce1 fatty acid transporter (Rv0200/OmamB); oxLDL, Oxidized LDL; PAP, Phosphatidic acid phosphatase; PDL1, Programmed death-ligand 1; PGJ2, Prostaglandin J2; PLIN2, 3 Perilipin 2 and 3; PPARα, PPARγ, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha or gamma; Ppe4, perilipin like protein 4; rv0966c, Uncharacterized protein Rv0966c; SAPC, SaposinC; Septin9, Septin-9, MLL septin-like fusion; siRNA, Silencing Ribonucleic Acid; SR-A1, Scavenger receptor class A type 1; SR-B1, Scavenger receptor class B type I; SREBP-1, Sterolbregulatory element binding protein 1; TAG, Triacylglycerol; TB, Tuberculosis; TDM, Lipid trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate of Mtb; Tgs-1, Probable diacyglycerol O-acyltransferase tgs1; THP1, Monocytic cell line; TLR2, Toll like receptor 2; TLRs, Toll like receptors; TNFα, Tumor Necrosis factor Alpha; TRAF1,2,3, TNFR associated factors; WHO, World Health Organization; WNT6, Wnt family member 6

Glossary

References

1. Zhai W, Wu F, Zhang Y, Fu Y, Liu Z. The Immune Escape Mechanisms of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20:340. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020340

2. Bowdish DM, Sakamoto K, Kim MJ, Kroos M, Mukhopadhyay S, Leifer CA, et al. MARCO, TLR2, and CD14 Are Required for Macrophage Cytokine Responses to Mycobacterial Trehalose Dimycolate and Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog (2009) 5:e1000474. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000474

3. Flynn JL, Chan J, Lin PL. Macrophages and Control of Granulomatous Inflammation in Tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol (2011) 4:271–8. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.14

4. Kim MJ, Wainwright HC, Locketz M, Bekker LG, Walther GB, Dittrich C, et al. Caseation of Human Tuberculosis Granulomas Correlates With Elevated Host Lipid Metabolism. EMBO Mol Med (2010) 2:258–74. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000079

5. Peyron P, Vaubourgeix J, Poquet Y, Levillain F, Botanch C, Bardou F, et al. Foamy Macrophages From Tuberculous Patients' Granulomas Constitute a Nutrient-Rich Reservoir for M. Tuberculosis Persistence. PLoS Pathog (2008) 4:e1000204. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000204

6. Remmerie A, Scott CL. Macrophages and Lipid Metabolism. Cell Immunol (2018) 330:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.01.020

7. Menegaut L, Jalil A, Thomas C, Masson D. Macrophage Fatty Acid Metabolism and Atherosclerosis: The Rise of PUFAs. Atherosclerosis (2019) 291:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.10.002

8. Febbraio M, Hajjar DP, Silverstein RL. CD36: A Class B Scavenger Receptor Involved in Angiogenesis, Atherosclerosis, Inflammation, and Lipid Metabolism. J Clin Invest (2001) 108:785–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI14006

9. Stuart LM, Deng J, Silver JM, Takahashi K, Tseng AA, Hennessy EJ, et al. Response to Staphylococcus Aureus Requires CD36-Mediated Phagocytosis Triggered by the COOH-Terminal Cytoplasmic Domain. J Cell Biol (2005) 170:477–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501113

10. Olzmann JA, Carvalho P. Dynamics and Functions of Lipid Droplets. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2019) 20:137–55. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0085-z

11. Pol A, Gross SP, Parton RG. Review: Biogenesis of the Multifunctional Lipid Droplet: Lipids, Proteins, and Sites. J Cell Biol (2014) 204:635–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201311051

12. Petan T, Jarc E, Jusovic M. Lipid Droplets in Cancer: Guardians of Fat in a Stressful World. Molecules (2018) 23:1941. doi: 10.3390/molecules23081941

13. Saito T, Kuma A, Sugiura Y, Ichimura Y, Obata M, Kitamura H, et al. Autophagy Regulates Lipid Metabolism Through Selective Turnover of Ncor1. Nat Commun (2019) 10:1567. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08829-3

14. Jaisinghani N, Dawa S, Singh K, Nandy A, Menon D, Bhandari PD, et al. Necrosis Driven Triglyceride Synthesis Primes Macrophages for Inflammation During Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. Front Immunol (2018) 9:1490. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01490

15. Currie E, Schulze A, Zechner R, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr. Cellular Fatty Acid Metabolism and Cancer. Cell Metab (2013) 18:153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.017

16. Walther TC, Chung J, Farese RV Jr. Lipid Droplet Biogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol (2017) 33:491–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060608

17. Cao J, Zhou Y, Peng H, Huang X, Stahler S, Suri V, et al. Targeting Acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol Acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) With Small Molecule Inhibitors for the Treatment of Metabolic Diseases. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:41838–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245456

18. Knight M, Braverman J, Asfaha K, Gronert K, Stanley S. Lipid Droplet Formation in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infected Macrophages Requires IFN-Gamma/HIF-1alpha Signaling and Supports Host Defense. PLoS Pathog (2018) 14:e1006874. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006874

19. Stuve P, Minarrieta L, Erdmann H, Arnold-Schrauf C, Swallow M, Guderian M, et al. De Novo Fatty Acid Synthesis During Mycobacterial Infection Is a Prerequisite for the Function of Highly Proliferative T Cells, But Not for Dendritic Cells or Macrophages. Front Immunol (2018) 9:495. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00495

20. Brandenburg J, Marwitz S, Tazoll SC, Waldow F, Kalsdorf B, Vierbuchen T, et al. WNT6/ACC2-Induced Storage of Triacylglycerols in Macrophages Is Exploited by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J Clin Invest (2021) 131:e141833. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.26.174110

21. Devries-Seimon T, Li Y, Yao PM, Stone E, Wang Y, Davis RJ, et al. Cholesterol-Induced Macrophage Apoptosis Requires ER Stress Pathways and Engagement of the Type A Scavenger Receptor. J Cell Biol (2005) 171:61–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502078

22. Kedi X, Ming Y, Yongping W, Yi Y, Xiaoxiang Z. Free Cholesterol Overloading Induced Smooth Muscle Cells Death and Activated Both ER- and Mitochondrial-Dependent Death Pathway. Atherosclerosis (2009) 207:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.04.019

23. Brewer HB Jr. The Lipid-Laden Foam Cell: An Elusive Target for Therapeutic Intervention. J Clin Invest (2000) 105:703–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI9664

24. Sakashita N, Miyazaki A, Chang CC, Chang TY, Kiyota E, Satoh M, et al. And Takeya, MAcyl-Coenzyme A:cholesterol Acyltransferase 2 (ACAT2) Is Induced in Monocyte-Derived Macrophages: In Vivo and In Vitro Studies. Lab Invest (2003) 83:1569–81. doi: 10.1097/01.LAB.0000095687.17383.39

25. Genoula M, Marín Franco JL, Dupont ML, Kviatcovsky D, Milillo A, Schierloh P, et al. Formation of Foamy Macrophages by Tuberculous Pleural Effusions Is Triggered by the Interleukin-10/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Axis through ACAT Upregulation. Front Immunol (2018) 9:459. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00459

26. Kleinnijenhuis J, Oosting M, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Van Crevel R. Innate Immune Recognition of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Clin Dev Immunol (2011) 2011:405310. doi: 10.1155/2011/405310

27. D'Avila H, Melo RC, Parreira GG, Werneck-Barroso E, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Bozza PT. Mycobacterium Bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Induces TLR2-Mediated Formation of Lipid Bodies: Intracellular Domains for Eicosanoid Synthesis In Vivo. J Immunol (2006) 176:3087–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3087

28. Almeida PE, Roque NR, Magalhaes KG, Mattos KA, Teixeira L, Maya-Monteiro C, et al. Differential TLR2 Downstream Signaling Regulates Lipid Metabolism and Cytokine Production Triggered by Mycobacterium Bovis BCG Infection. Biochim Biophys Acta (2014) 1841:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.10.008

29. Guerrini V, Prideaux B, Blanc L, Bruiners N, Arrigucci R, Singh S, et al. Storage Lipid Studies in Tuberculosis Reveal That Foam Cell Biogenesis Is Disease-Specific. PLoS Pathog (2018) 14:e1007223. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007223

30. Agarwal P, Combes TW, Shojaee-Moradie F, Fielding B, Gordon S, Mizrahi V, et al. Foam Cells Control Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. Front Microbiol (2020) 11:1394. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01394

31. Im DS. Intercellular Lipid Mediators and GPCR Drug Discovery. Biomol Ther (Seoul) (2013) 21:411–22. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.080

32. Yu K, Bayona W, Kallen CB, Harding HP, Ravera CP, Mcmahon G, et al. Differential Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors by Eicosanoids. J Biol Chem (1995) 270:23975–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23975

33. Singh V, Jamwal S, Jain R, Verma P, Gokhale R, Rao KV. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis-Driven Targeted Recalibration of Macrophage Lipid Homeostasis Promotes the Foamy Phenotype. Cell Host Microbe (2012) 12:669–81. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.012

34. Jarc E, Petan T. A Twist of FATe: Lipid Droplets and Inflammatory Lipid Mediators. Biochimie (2020) 169:69–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.11.016

35. Pisu D, Huang L, Narang V, Theriault M, Le-Bury G, Lee B, et al. Single Cell Analysis of M. Tuberculosis Phenotype and Macrophage Lineages in the Infected Lung. J Exp Med (2021) 218: e20210615. doi: 10.1084/jem.20210615

36. Daniel J, Maamar H, Deb C, Sirakova TD, Kolattukudy PE. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Uses Host Triacylglycerol to Accumulate Lipid Droplets and Acquires a Dormancy-Like Phenotype in Lipid-Loaded Macrophages. PLoS Pathog (2011) 7:e1002093. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002093

37. Lee W, Vanderven BC, Fahey RJ, Russell DG. Intracellular Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Exploits Host-Derived Fatty Acids to Limit Metabolic Stress. J Biol Chem (2013) 288:6788–800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445056

38. Pandey AK, Sassetti CM. Mycobacterial Persistence Requires the Utilization of Host Cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2008) 105:4376–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711159105

39. Van der Geize R, Yam K, Heuser T, Wilbrink MH, Hara H, Anderton MC, et al. A Gene Cluster Encoding Cholesterol Catabolism in a Soil Actinomycete Provides Insight Into Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Survival in Macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007) 104:1947–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605728104

40. Daniel J, Kapoor N, Sirakova T, Sinha R, Kolattukudy P. The Perilipin-Like PPE15 Protein in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Is Required for Triacylglycerol Accumulation Under Dormancy-Inducing Conditions. Mol Microbiol (2016) 101:784–94. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13422

41. Nazarova EV, Montague CR, La T, Wilburn KM, Sukumar N, Lee W, et al. Rv3723/LucA Coordinates Fatty Acid and Cholesterol Uptake in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Elife (2017) 6:e26969. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26969

42. Nazarova EV, Montague CR, Huang L, La T, Russell D, Vanderven BC. The Genetic Requirements of Fatty Acid Import by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Within Macrophages. Elife (2019) 8:e43621. doi: 10.7554/eLife.43621

43. Rastogi S, Agarwal P, Krishnan MY. Use of an Adipocyte Model to Study the Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis to Store and Degrade Host Fat. Int J Mycobacteriol (2016) 5:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2015.10.003

44. Singh KH, Jha B, Dwivedy A, Choudhary E, N AG, Ashraf A, et al. Characterization of a Secretory Hydrolase From Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Sheds Critical Insight Into Host Lipid Utilization by M. Tuberculosis. J Biol Chem (2017) 292:11326–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.794297

45. Munoz-Elias EJ, Upton AM, Cherian J, Mckinney JD. Role of the Methylcitrate Cycle in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Metabolism, Intracellular Growth, and Virulence. Mol Microbiol (2006) 60:1109–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05155.x

46. Ordway D, Henao-Tamayo M, Orme IM, Gonzalez-Juarrero M. Foamy Macrophages Within Lung Granulomas of Mice Infected With Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Express Molecules Characteristic of Dendritic Cells and Antiapoptotic Markers of the TNF Receptor-Associated Factor Family. J Immunol (2005) 175:3873–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3873

47. Cardona PJ, Llatjos R, Gordillo S, Diaz J, Ojanguren I, Ariza A, et al. Evolution of Granulomas in Lungs of Mice Infected Aerogenically With Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol (2000) 52:156–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00763.x

48. Trogan E, Feig JE, Dogan S, Rothblat GH, Angeli V, Tacke F, et al. Gene Expression Changes in Foam Cells and the Role of Chemokine Receptor CCR7 During Atherosclerosis Regression in ApoE-Deficient Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2006) 103:3781–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511043103

49. Hunter RL, Jagannath C, Actor JK. Pathology of Postprimary Tuberculosis in Humans and Mice: Contradiction of Long-Held Beliefs. Tuberc (Edinb) (2007) 87:267–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.11.003

Keywords: tuberculosis, Mycobacterium, macrophage, foam cells, lipid droplets

Citation: Agarwal P, Gordon S and Martinez FO (2021) Foam Cell Macrophages in Tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 12:775326. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.775326

Received: 13 September 2021; Accepted: 29 November 2021;

Published: 15 December 2021.

Edited by:

Samantha Leigh Sampson, Stellenbosch University, South AfricaReviewed by:

Valentina Guerrini, Rutgers University, Newark, United StatesTobias Dallenga, Research Center Borstel (LG), Germany

Copyright © 2021 Agarwal, Gordon and Martinez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pooja Agarwal, cG9vamFiaW90ZWNoMjAwOUBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Fernando O. Martinez, Zi5tYXJ0aW5lemVzdHJhZGFAc3VycmV5LmFjLnVr

Pooja Agarwal

Pooja Agarwal Siamon Gordon

Siamon Gordon Fernando O. Martinez

Fernando O. Martinez