95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 13 August 2021

Sec. Antigen Presenting Cell Biology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.724601

This article is part of the Research Topic Local Immune Modulation of Macrophages and Dendritic Cells View all 14 articles

The ocular tissue microenvironment is immune privileged and uses several mechanisms of immunosuppression to prevent the induction of inflammation. Besides being a blood-barrier and source of photoreceptor nutrients, the retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE) regulate the activity of immune cells within the retina. These mechanisms involve the expression of immunomodulating molecules that make macrophages and microglial cells suppress inflammation and promote immune tolerance. The RPE have an important role in ocular immune privilege to regulate the behavior of immune cells within the retina. Reviewed is the current understanding of how RPE mediate this regulation and the changes seen under pathological conditions.

The eye is called immune privileged from the original observations of prolonged allograft survival within the anterior chamber even following immunization to alloantigens (1). This now includes immune regulation and immune tolerance to antigens and pathogens within the eye (2–4). The ocular microenvironment is delineated by blood barriers and the lack of direct lymphatic drainage. Within this microenvironment immune cells differentiate into cells that suppress inflammation and promote immune tolerance (5). The mediators of ocular immune regulation and tolerance are soluble, and membrane bound molecules. An important membrane bound molecule is membrane FasL (6, 7). Its expression by cells of the ocular blood-barriers, including the retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE), mediates a contact dependent induction of apoptosis in monocytes and lymphocytes preventing their accumulation and infiltration. Also, the RPE release extracellular membranes expressing membrane-FasL that also induce apoptosis in macrophages potentially away from the RPE monolayer (8). Many of the soluble mediators of ocular immunosuppression can be found in aqueous humor and in the supernatant of cultured RPE. These mediators include a wide range immunoregulating cytokines, neuropeptides, and soluble ligands. These include Transforming Growth Factor-beta2 (TGF-β2) and alpha-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone (α-MSH), which are highly conserved and potent regulators of immune cell activity and suppressors of inflammation (9–12). The current picture of ocular immune privilege is a tissue microenvironment that actively manipulates immune cells to promote the health of the visual axis, and to prevent the activation of inflammation. These mechanisms of ocular immune privilege are for most of us highly effective in preventing inflammation, and the mediators of immune privilege have potential to be therapeutically adapted to suppress inflammation within the eye and in other tissues.

One of the experimental examples of ocular immune privilege is the phenomena of anterior chamber associated immune deviation (ACAID) (13, 14). ACAID is induced by placing foreign antigen within the anterior chamber of the eye. The antigen is picked up and processed for presentation by F4/80 positive macrophages that migrate to the spleen (15, 16). In the spleen with the help of recruited B-cells and NK T cells, there is an antigen-specific activation and expansion of both CD8 and CD4 regulatory T cells (17–20). This brings about systemic tolerance to the foreign antigen. Placing foreign antigen in the subretinal space (the temporary pocket that forms when the photoreceptors are detached from the RPE) also induces an ACAID-like response (21). This has defined immune privilege to include the retina.

The placement of neonatal-retinal allografts into the retina are not immunologically rejected and moreover they differentiate (22). Also, there is induced tolerance to the alloantigen through an ACAID-like response. The induction of the ACAID-like response is mediated by TGF-β2 like in ACAID; however, it requires the expression of Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) (23). The TSP-1 is a known activator of latent TGF-β2 (24). In mice with TSP-1 knocked out the ACAID-like response cannot be induced; moreover, TSP-1 knock-out mice with experimental autoimmune disease (EAU) cannot self-resolve EAU like wild-type mice. The ACAID-like response cannot be induced when the integrity of the RPE monolayer is compromised through chemical or laser wounding (21, 25, 26). In addition, laser wounding not only causes the loss of immune privilege in the affected eye but also causes a loss of immune privilege in the untouched contralateral eye. This may be mediated by the release of Substance P by the retina (26). Together the results demonstrate the need for an intact RPE monolayer to maintain ocular immune privilege.

The ACAID-like response shows that the RPE directly affect the functionality of immune cells by maintaining the anti-inflammatory retinal microenvironment. One of the interesting findings is that the RPE soluble molecules induce and enhance regulatory activity in Treg cells (27–29). Also, the RPE release soluble factors that suppress the activation of effector T cells (23, 30). Of interest in this review is the ability of the RPE to regulate potential antigen presenting cells, the immune cells that sit at the interface of innate and adaptive immune response. The RPE have been found to suppress the activation of dendritic cells (31, 32), which would prevent naive T cell activation to antigen carried from the retina to a regional lymph node. In addition, the RPE promote the development and activation of myeloid suppressor cells from bone-marrow progenitor cells (33). These suppressor cells are highly capable of preventing and inhibiting adaptive immune responses. Interestingly, the RPE induction of these suppressor cells is mediated by IL-6, which is usually considered a proinflammatory cytokine and an anti-ACAID cytokine (34).

Using a technique of in situ RPE eyecup cultures, treating endotoxin-stimulated macrophages with the RPE eyecup conditioned culture-media suppresses proinflammatory cytokine production, while promoting anti-inflammatory activity (35–37). Moreover, the treatment of macrophages with the RPE soluble factors induces anti-inflammatory cytokine production and characteristics of myeloid suppressor cells (37). The mediators of this activity are the neuropeptides α-MSH, and Neuropeptide Y (NPY) produced by the RPE. The collective action of the soluble factors, constitutively produced by the RPE, induce macrophages, and resident microglial cells to be themselves mediators of anti-inflammatory activity and activators of Treg cells. These findings demonstrate the importance of the RPE monolayer in maintaining immune privilege.

The health and integrity of the RPE monolayer may very well be required for maintaining immune regulation along with maintaining a functional retina. The RPE is a cuboidal monolayer of hexagonal cells that lies between the photoreceptors and Bruch’s membrane (38). On the apical side, the RPE has microvilli that envelop the distal-ends of the photoreceptors with each RPE cell projecting towards 20-55 photoreceptors (39–41). On the basal side lies Bruch’s membrane a pentalaminar structure, which separates the RPE from the eye’s fenestrated choroidal capillaries (42). The RPE maintains this polarity through a complex network of tight junctions near the apical side that create a barrier to paracellular diffusion (43). The tight junctions include occludins and claudins both of which play essential regulatory roles in maintenance of the function of the tight junctions. The composition of claudins expressed in the RPE varies by species (44). In the human RPE, claudin 19 is the most predominant and mutations of CLDN10 gene that encodes it can lead to dysfunction of the tight junctions along with severe ocular abnormalities (43, 45).

The RPE plays a variety of critical roles in maintaining the function of the retina including acting as the outer blood-retina barrier and regulating the transport of waste and nutrients (46, 47). In order to accomplish these functions, the RPE exhibits polarity with an asymmetric distribution of organelles, proteins, and functionality allowing it to create a unique microenvironment for the retina (48). For example, melanosomes are preferentially located near the apical cell membrane with Golgi and mitochondria preferentially localize to basal cytoplasm (38). The visual cycle is dependent on the conversion of 11-cis-retinol to 11-trans-retinol and the RPE plays a key role in re-isomerizing 11-cis-retinol from 11-trans-retinol (39, 49, 50). Many of the key metabolic enzymes involved in this re-isomerization process are expressed in the RPE (39). The photoreceptors have a delicate equilibrium between nutrient renewal and damaged component disposal which sheds up to 10% of their volume. The RPE phagocytizes the end-processes allowing new end-processes to take their place (39).

In the healthy retina, the RPE separates the choroidal blood supply from photoreceptors and manages the microenvironment of the retina by regulating the flow of water and ions between the two spaces (51). The RPE contains tight junctions that play a role in its ability to act as the outer part of the blood-retina barrier (47). In studies on chicken RPE, it was shown that the tight junctions of the RPE have increased complexities with P-face-associated tight junctions vs the tight junctions in choroid vessels (52). This increased complexity may be necessary for the formation of an effective blood-retina barrier. However, in vitro studies have indicated that the functional barrier for macromolecules, specifically serum albumin, is similar between the RPE and the iris pigment epithelium (53). This suggests that at the very least the general barrier function of the RPE is like other tight-junction epithelial layers. The regulation of what can enter the retina is apparent as the outer blood-retinal barrier formed by the RPE sometimes poses a problem in the use of some systemic drugs for the treatment of retinal diseases (54). However, even with the blood-retina barrier of the RPE and its tight junctions, the retina is still susceptible to damage, as in the case of some systemic medications lead to retinal dysfunction and degeneration (21, 55).

In disease states like AMD and Alzheimer’s, the accumulation of Aβ in the RPE via RAGE/p38 MAPK-mediated endocytosis can lead to attenuation and disorganization of the tight junctions, and in some cases breakdown of the tight junctions (56, 57). In AMD the leading cause of visual impairment in western countries of people over 50 (58), damage to the RPE and RPE dysfunction are thought to be the initial insult in the atrophic variant which accounts for 85-90% of cases (40, 59). In the wet variant, while the choriocapillaris complex is thought to be the initial site of dysfunction, damage to the RPE soon follows and plays a key role in visual loss (59).

The breakdown of the blood-retina barrier created by the RPE has been shown to be one of the earliest pathologic changes that can be detected in some diseases like diabetes (60). In diabetic retinopathy, previous work has noted that the involvement of the inner blood-retina barrier due to endothelial cell dysfunction can lead to diabetic macular oedema and retinopathy (47). The dysfunction of the outer blood-retina barrier at the RPE may play a role in diabetic retinopathy in that the presence of cytokines, such as IL-6, have been shown to disrupt the outer blood-retina barrier through amplified recruitment of microglial cells and increased production of TNF- α (61). Additionally, high glucose states have been shown to lead to RPE cells downregulating GLUT-1 and a reduction in the levels of antioxidants potentially leading to retinal tissue damage (62). In some rodent studies the breakdown of the tight junctions in the RPE results in vascular leakage as visualized in diabetic and ischemic rodents (63). When the blood-retina barrier is compromised, it can lead to additional disease processes such as uveitic macular edema (64). Abnormal regulation of the RPE in mice lacking ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABCA1 and ABCG1) leads to discontinuities of the RPE and degeneration of the overlying photoreceptors (65). In some disease states like AMD and diabetic retinopathy the transplantation of RPE has even been explored as treatment options with some trials showing preliminary signs of success (66, 67). Interestingly in mice with degenerating photoreceptors, retinal microglia cells migrate from the inner retina to the subretinal space and undergo a transcriptional change to express homeostatic checkpoint and wound-responsive genes that protect the RPE (68). While it is not clear as to the signals that induced the migration, this does suggest that there is an initial attempt by the ocular microenvironment to preserve the functionality of the RPE and its blood-barrier under disease conditions. Therapeutic interventions that can maintain or restore RPE health could also maintain and restore immune privilege that would reduce the potential contribution of inflammation to many retinal degenerative diseases.

The growing use of lasers in the military, healthcare, laboratories, and academia causes an increased in ocular injury by misdirected lasers (69). In general, lasers are classified as I, II, IIIa, IIIb and IV. The first two Classes of Class II and Class IIIa are relatively safe while the last two are hazardous. Laser light is visible between 400 and 700 nm, and other sources are infrared and ultraviolet lasers. Usually, transient exposure to Class II or Class IIIa laser may not result in eye injury. Handheld laser pointers are usually Class IIIa and have comparatively low energy that is insufficient to cause injury at the ocular surface, but the focusing power of the eye causes a powerful amplification of irradiance that makes the retina susceptible to laser injury. The prolonged exposure to this laser may cause severe, permanent, and irreversible damage accompanied with vision loss (70, 71).

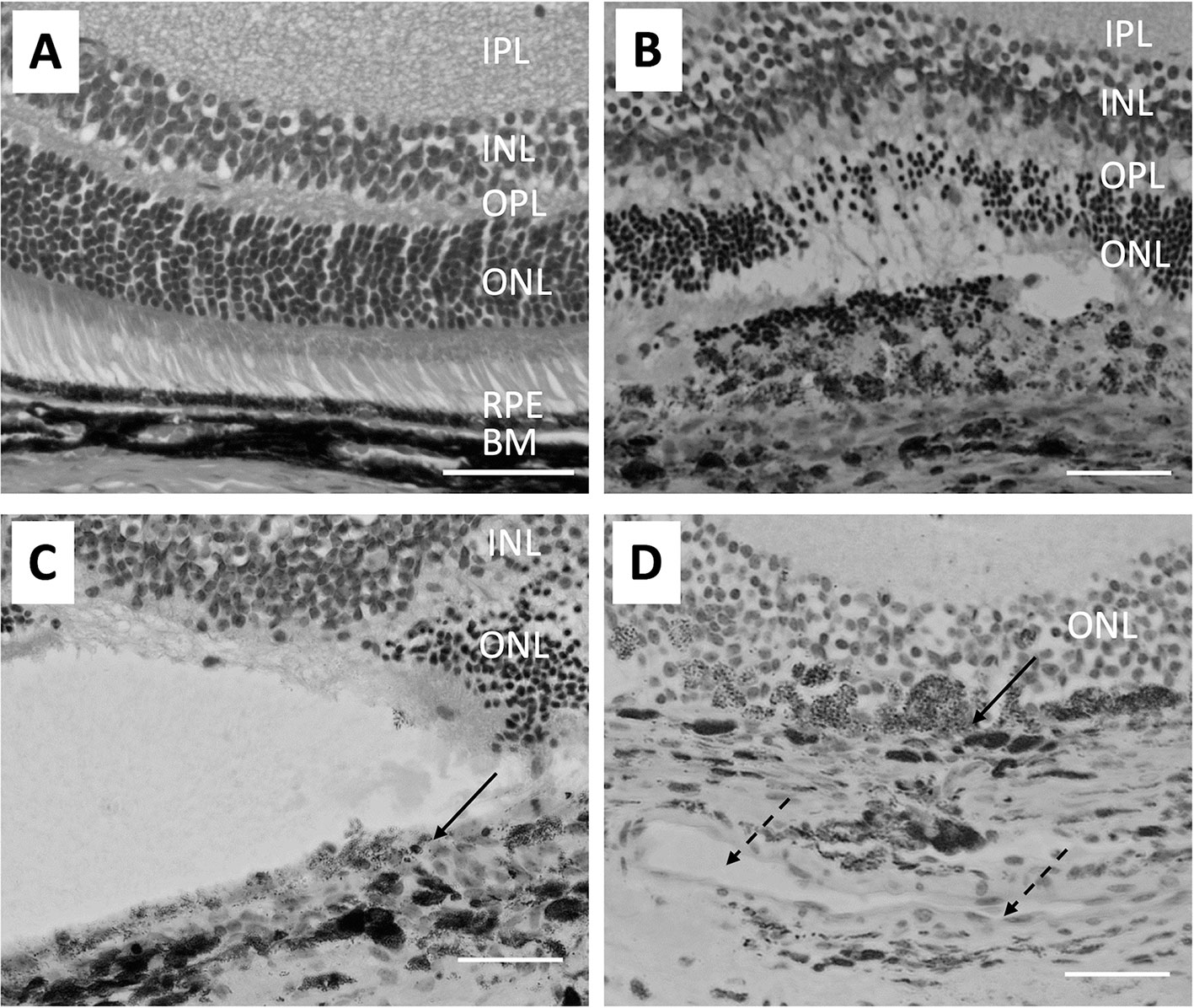

The coagulative irradiation of laser causes an initial destruction and secondary tissue responses (Figure 1). The initial destruction occurs from the thermal degradation of the incident energy absorbed by RPE pigment and changes are seen almost immediately (72–75). Coagulation necrosis of the RPE and the photoreceptor cells happens at this acute stage. The inner-nuclear-layer (INL) is usually unharmed. The RPE barrier breaks down and cell debris is found within and between disrupted RPE and in the outer retina. Three days after laser burn, Bruch membrane is disrupted and the subretinal space and the inner retina are infiltrated with macrophages. The RPE and photoreceptors become necrotic (Figure 1B). Five days after laser burn, all photoreceptor cells around the burn area are gone, but most of the INL cells are still intact (Figure 1C). There is vacuoling of cells in the IP and the retinal ganglion cell (RGC) layers are seen. By day 14, the RPE show placoid and are found to cover the laser injury site partially. There were many clusters of pigment-filled macrophages around the injury site including in the INL (Figure 1D). By day 120, the RPE covers the injury site (75).

Figure 1 Micrographs show the pathological changes of retina and choroid from day 0 to day 14 after laser injury. (A) shows a healthy naive retina. The RPE is a single cell layer. (B) shows the retina on day 3 after laser injury. Bruch’s membrane is disrupted and RPE cells and most ONL cells are lost at the laser injury site. Also, arrangement of pigmented cells in the choroid is disrupted. (C) Similar histological structures are seen on day 5 after retinal laser-injury. Solid arrow points to the discontinued RPE cells. (D) shows the retina 14 days after laser injury. A large capillary (broken arrows) forms in the choroid adjacent to the laser injury site. Macrophages filled with pigment are found in the ONL and some RPE (solid arrow) are found covering the injured site with a disrupted Bruch’s membrane. The size bar is 50 microns in length.

The RPE is not only a physical barrier but is also an important source of immune-suppressive molecules that contribute to the immune privileged status of the eye. In naive retinas, microglia are in the inner and outer plexiform layer and after laser injury they accumulate with macrophages and granulocytes at the site of the laser burn in the retina and choroid (76). Changes in retinal microglial cells can be seen 1 day after the laser injury with expression of MHC class II (75). In addition, co-stimulatory factors of CD40 and CD86 are found on these activated microglia. The condition media of cultured RPE eyecups from laser-wounded eyes contain significantly lower amounts of α-MSH (37). In the normal retina the microglia co-express NOS2 and Arginase1, but in laser wounded retinas co-expression of the two enzymes is not seen (37). Moreover, infiltrating the laser wound site are Arginase1-positive macrophages that are a source of VEGF to initiate choroidal neovascularization (37, 77). This corresponds with the loss of ACAID in both the eye with the laser injury and the unwounded counter-lateral eye (25, 26). This appears be mediated by the release of another neuropeptide Substance P. How this affects RPE regulation of immunity in the non-lasered eye is not understood; however, the laser wounded RPE monolayer does not induce the co-expression of NOS2 and Arginase 1 in macrophages (37). This further indicates the importance of an intact RPE monolayer for the RPE to regulate immune cells.

After the laser injury, the damage of the RPE and the surrounding neural retina and the underlying choroid, the retinal microglia and the choroidal inflammatory cells may mediate release of proinflammatory cytokines (78–80). These cytokines may exacerbate neuronal damage. Pro-angiogenic VEGF is the primary factor made and pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-3, IL-6 and TNF-α would be necessary as a wound repair process following laser photocoagulation. In addition, production of chemokines including MCP-1 and MIP-2 are increased (75, 81). These show that physical damage of the RPE monolayer promotes the infiltration of immune cells and the induction of an inflammatory response. This has implications not only on laser wounding, but also on retinal degenerative diseases like age related macular degeneration as RPE cells die.

Autoimmune uveitis is one of the leading causes of blindness in developed countries. The retina is usually the target, but the RPE cells may also be killed as collateral damage due to inflammation (82, 83). The common rodent models of experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) are induced with inter-photoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) emulsified in adjuvant, and other models use retinal arrestin, rhodopsin and RPE-65 (84–86). The IRBP-model has a prodromal phase till day 14 and usually reaches a score of 1 on the clinical grading system and peaks on day 21 with a clinical score of 3. Then the disease progresses into a chronic phase of sustained clinical scores of 3 until day 70 where the disease begins to self-resolve (87, 88).

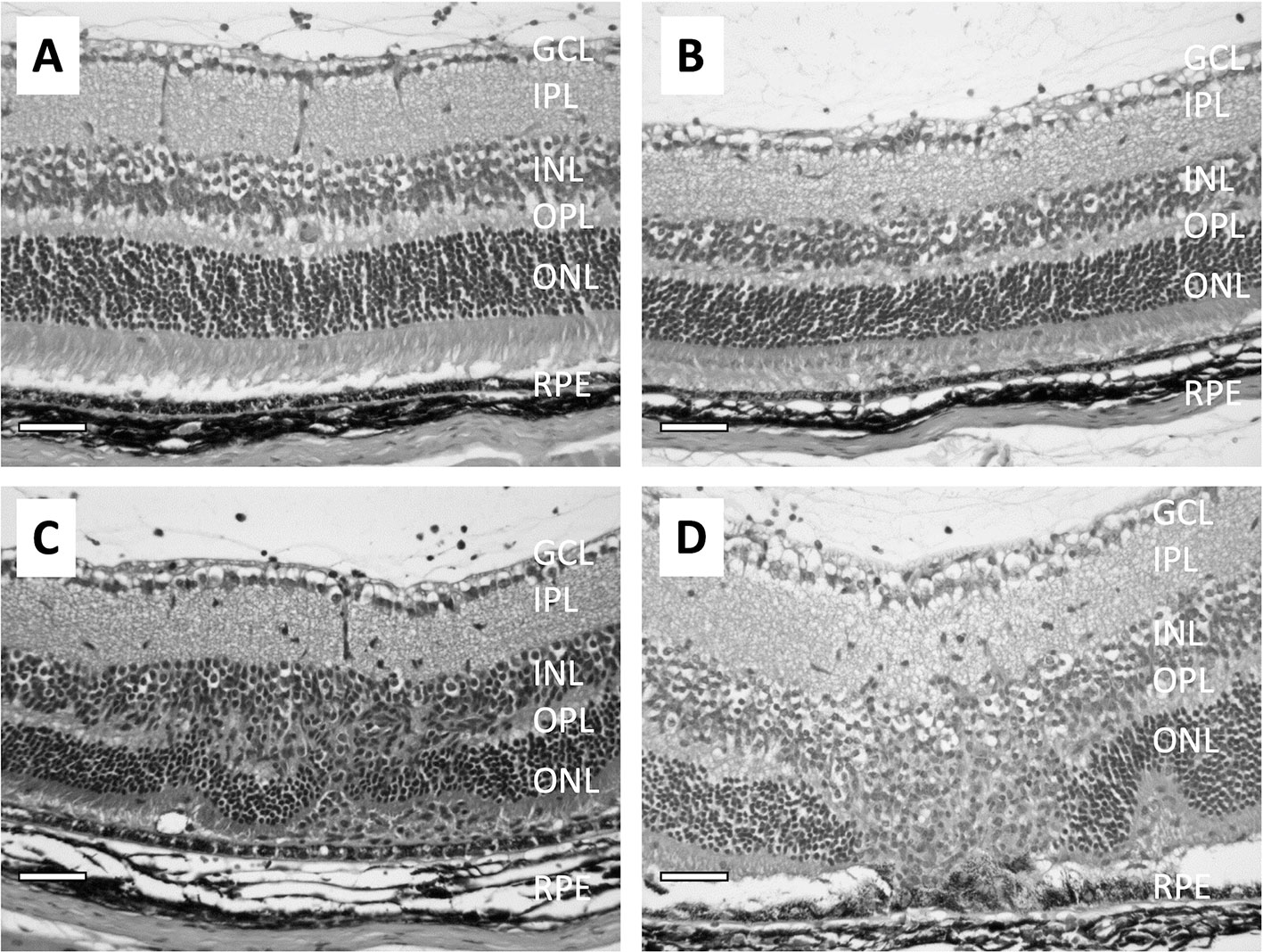

Histological evaluation of the eyes from rodents immunized to induce EAU show that the loss of the RPE monolayer is progressive along with the chronic nature of EAU (Figure 2) (89–91). Very little damage to the RPE is seen in the early stages of EAU (Figures 2A–C); however, As the disease progresses through the chronic phase, there is severe damage of both INL cells and photoreceptor cells, with the RPE shows damage with pigment-laden macrophages near the damaged RPE (Figure 2D).

Figure 2 Micrographs show the pathological changes of retina from mice with EAU clinical score ranging from 1 to 3. (A) shows a retina with EAU clinical score 1. The RPE is intact and there are no noted changes in the retina except for some inflammatory cells in the vitreous. (B) shows the retina with EAU clinical score 2. There are more infiltrating cells in the vitreous and the subretinal space. Both the retina and RPE are intact, with minor lesions found in the INL. (C) is the retina at early stage of chronic EAU, clinical score 3. The RPE is intact, and infiltration of inflammatory cells are found in the vitreous and in the retina with disruption of the INL and IPL with loss of the ONL cells. (D) shows the retina at a late stage of chronic EAU, sustained clinical score of 3. The RPE monolayer is disrupted and fused with the ONL and adjacent outer/inner segments of the photoreceptors gone. There are pigment-filled macrophages around sites of RPE cell loss. The size bar is 50 microns in length.

The pathogenesis of inflammatory disorders of EAU is associated with autoreactive effector CD4+ T cells. In the early stages of IRBP-induced EAU the effector T cells are polarized to the Th1 phenotype and produce IFNγ (92, 93). These effector Th1 cells are highly active and mediate EAU in naive recipient animals. However, neutralizing IFNγ does not suppress EAU but worsen the disease because of the activation of Th17 cells (94–97). The Th17 cells target the RPE, and the disruption of the blood-retinal barrier causes the influx of serum antibodies, which exacerbate EAU (98). Mice with TSP-1 knocked-out also suffer with severe and prolonged EAU. To initiate a T cell response there needs to be present an APC expressing MHC class II. Normally the expression of MHC along with co-stimulatory molecules within the eye is low to undetectable, and while initially the microglia do not express MHC, they increase in MHC expression as EAU progresses (93, 99). In addition, there is need for the microglia in a non-MHC dependent manner to recruit effector T cells and MHC-expressing monocytes into the retina (99).

Since the course of EAU is self-limiting, it has suggested that while the RPE may be targeted and affected by the retinal inflammation there is still some immunosuppressive activity. It was found that EAU resolution is associated with the emergence of a specific type of APC within the spleen that in an antigen-specific manner counter-converts effector T cells into inducible Treg cells (88, 100). This process is dependent on the expression of the melanocortin 5-receptor (MC5r), one of the receptors of α-MSH. Moreover, expression of MC5r is necessary to modulate the severity of EAU and the functions of APC (91). The RPE is important to maintain the health of the retina not only by phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments, recycling retinol and maintaining the blood-retinal barrier, it also provides support to maintain immune privilege within the eye.

ACAID demonstrates that macrophages with the potential of becoming antigen presenting cells (APC) are influenced by the ocular microenvironment to promote Treg cell activation. This has suggested that within the retina a similar influence should be seen with resident microglial cells. When assayed it is found that microglial cells are very much suppressed in immune activity; moreover, they co-express Nitric Oxide Synthase 2 (NOS2) with Arginase 1 (37). This co-expression of a M1 marker of inflammation-mediating cells and a M2 tissue repair/suppressor-mediating cells is characteristic of tumor associated myeloid cells that suppress immune attack of tumors (101, 102). Co-expression of NOS2 and Arginase 1 is induced by treating macrophages with the soluble factors of RPE. Specifically, it was found that the neuropeptides α-MSH and NPY produced by the RPE mediate this unique characterization of macrophages, which can enhance apoptosis in activated effector T cells (37). The soluble RPE factors also induce macrophages to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines even when the macrophages are treated with a pro-inflammatory signal such as endotoxin (35, 36, 103). This alternative activation of macrophages is mediated by α-MSH and provides for an anti-inflammatory response when there is an immune challenge within the ocular microenvironment (35). This potential for the retina to be a site of generating alternatively activated macrophages and myeloid-like suppressor cells makes the environment nor only anti-inflammatory but a site where immune cells are made to regulate other immune cells.

Phagocytizing materials is central for an APC to process antigen for presentation on MHC class II molecules (104). Recently we have found that the process of phagocytosis is also altered by the RPE through its release of α-MSH and NPY (105, 106). The neuropeptides mediate a differential regulation of phagocytic uptake of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (107). There is suppression in the number of gram-negative bacteria taken up and a suppression of the number of macrophages taking-up gram-positive bacteria. There is no change in the expression of scavenger receptors on the macrophages suggesting that this may be a change in how Toll-like receptor stimulation in the macrophages is suppressed (108, 109). If the bacteria are opsonized, there is no effect of the neuropeptide treatment on the up-take of opsonized-gram-negative and positive bacteria (107). However, activation of the phagolysosome is suppressed. The suppression is in part due to both downregulation of LAMP1, which is needed for phagolysosome acidification, and a blockade of the phagosome maturation pathway preventing the transition of phagosomes from early to intermediate (110). The suppression of phagocytosis and phagosome maturation by the RPE through the neuropeptides α-MSH and NPY would either prevent the processing of antigen within the retina or at least alter the processing of the antigen to unrecognizable amino-acid sequences that could be presented by APC in the retina (110). The RPE from eyes with autoimmune uveitis do not suppress the phagocytic pathway, and this may be associated with high levels of IL-6 expression (105). The regulation of phagolysosome activation is dependent also on the RPE maintaining an intact monolayer (106). Therefore, one potential contribution of the RPE to immune privilege is its suppression of the processing and presentation of self-antigens by retinal APC that would prevent the activation of autoimmune disease-mediating effector T cells. This importance of the RPE to mediate immune regulation and prevent induction of autoimmune disease indicates that changes to the RPE will have a corresponding change in the regulation of immune cells within the retina.

A key reason for understanding the molecular mechanisms of ocular immune privilege is to see whether these molecules that are normally regulating immune cell activity can be used to suppress uveitis and restore immune privilege. Since the neuropeptide α-MSH has its own immune regulating/anti-inflammatory properties as well as contributing to the mechanism of ocular immune privilege there is a strong potential of using α-MSH as a therapeutic approach to uveitis (111, 112). The neuropeptide is 13 amino acids long and is easily injected. When mice with EAU are treated with α-MSH at the beginning of the chronic phase the retinal inflammation begins to resolve within a week of the treatment (84, 91, 100). After 2 to 3 weeks EAU is fully resolved in comparison to another 8 weeks in the untreated EAU mice. In the spleen of the α-MSH-treated EAU mice are Treg cells specific for retinal autoantigen. These Treg cells provide the mice with protection from a memory immune response to the autoantigen. The same induction of Treg cell is found in the spleen of mice that have resolved EAU on their own (88, 113, 114). These Treg cells are derived from the population of effector T cells that are converted by APC into antigen-specific inducible Treg cells (88, 100). Under conditions of uveitis the RPE cannot suppress phagosome maturation and phagolysosome activation, and after α-MSH therapy the RPE recover their ability to suppress phagosome maturation and phagolysosome activation (91, 105). Therapeutic use of α-MSH in EAU suppresses uveitis, induces Treg cells to retinal autoantigen, and may very well reestablish RPE regulation of immune cell activity within the retina.

There is a dependency on MC5r for some of the EAU recovery. While MC5r-knockout mice recover on their own from EAU, like wild type mice, they lack the presence of the suppressor APC and the antigen-specific Treg cells within their spleens (100, 114, 115). While α-MSH treatment suppressed EAU in the knockout mice it does not protect the retina from the damage of inflammation, not did it promote recovery of RPE mediated suppression of phagolysosome activation (91). These results suggest that while the use of α-MSH in therapy to suppress inflammation is possible through its other receptors, it appears that the recovery of immune privilege is dependent on α-MSH working through MC5r. Also, by tailoring the therapy to specific melanocortin receptors different aspects of an immune response can be targeted for regulation (116). The experimental therapeutic use of α-MSH in EAU demonstrates that it is possible to use the mechanisms of ocular immune privilege, and potentially other RPE generated molecules, to suppress inflammation and reestablish ocular immune privilege and tolerance (117, 118).

The RPE holds an important role in the maintenance of ocular immune privilege in being a blood-barrier and a producer of immune regulatory molecules. These molecules are not just anti-inflammatory, they promote immune regulatory and suppressive behaviors within immune cells they target. It makes these different for other forms of therapy that either suppress all immune activity or block specific key cytokines. The change in immune cells behavior by the RPE allows for immune cell activity to be supportive of the retina while immune cells regulate themselves and other immune cells that may migrate into the retina. While it is not fully understood as to whether in retinal diseases the change is first in the retina or in the RPE, but once the RPE layer is injured it is difficult for the retina to function and to prevent the activation of damaging immune activity.

All three authors were involved in the planning, writing and editing of this review and agree to be accountable for the content of this work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work is supported in part by a grant from the NIH/NEI EY025961 and the Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund.

AT is a scientific advisor and recipient of a sponsored research agreement from Palatin Technologies Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Medawar P. Immunity to Homologous Grafted Skin. III. The Fate of Skin Homografts Transplanted to the Brain to Subcutaneous Tissue, and to the Anterior Chamber of the Eye. Br J Exp Pathol (1948) 29:58–69.

2. Taylor AW, Kaplan HJ. Ocular Immune Privilege in the Year 2010: Ocular Immune Privilege and Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm (2010) 18(6):488–92. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.525730

4. Forrester JV, McMenamin PG, Dando SJ. CNS Infection and Immune Privilege. Nat Rev Neurosci (2018) 19(11):655–71. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0070-8

5. Taylor AW, Ng TF. Negative Regulators That Mediate Ocular Immune Privilege. J Leukoc Biol (2018) 103:1179–87. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MIR0817-337R

6. Griffith TS, Brunner T, Fletcher SM, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Fas Ligand-Induced Apoptosis as a Mechanism of Immune Privilege. Science (1995) 270(5239):1189–92. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189

7. Levy O, Calippe B, Lavalette S, Hu SJ, Raoul W, Dominguez E, et al. Apolipoprotein E Promotes Subretinal Mononuclear Phagocyte Survival and Chronic Inflammation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. EMBO Mol Med (2015) 7(2):211–26. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404524

8. Sanjiv N, Osathanugrah P, Fraser E, Ng TF, Taylor AW. Extracellular Soluble Membranes From Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Mediate Apoptosis in Macrophages. Cells (2021) 10(5):1193. doi: 10.3390/cells10051193

9. Taylor AW, Streilein JW, Cousins SW. Identification of Alpha-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone as a Potential Immunosuppressive Factor in Aqueous-Humor. Curr Eye Res (1992) 11(12):1199–206. doi: 10.3109/02713689208999545

10. Cousins SW, Mccabe MM, Danielpour D, Streilein JW. Identification of Transforming Growth-Factor-Beta as an Immunosuppressive Factor in Aqueous-Humor. Invest Ophth Vis Sci (1991) 32(8):2201–11.

11. Granstein RD, Staszewski R, Knisely TL, Zeira E, Nazareno R, Latina M, et al. Aqueous-Humor Contains Transforming Growth-Factor-Beta and a Small (Less-Than 3500 Daltons) Inhibitor of Thymocyte Proliferation. J Immunol (1990) 144(8):3021–7.

12. Jampel HD, Roche N, Stark WJ, Roberts AB. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta in Human Aqueous Humor. Curr Eye Res (1990) 9(10):963–9. doi: 10.3109/02713689009069932

13. Streilein JW, Niederkorn JY. Induction of Anterior Chamber-Associated Immune Deviation Requires an Intact, Functional Spleen. J Exp Med (1981) 153(5):1058–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1058

14. Kaplan HJ, Streilein JW. Do Immunologically Privileged Sites Require a Functioning Spleen? Nature (1974) 251(5475):553–4. doi: 10.1038/251553a0

15. Wilbanks GA, Streilein JW. Studies on the Induction of Anterior Chamber-Associated Immune Deviation (ACAID). 1. Evidence That an Antigen-Specific, ACAID-Inducing, Cell-Associated Signal Exists in the Peripheral Blood. J Immunol (1991) 146(8):2610–7.

16. Wilbanks GA, Streilein JW. Macrophages Capable of Inducing Anterior Chamber Associated Immune Deviation Demonstrate Spleen-Seeking Migratory Properties. Reg Immunol (1992) 4(3):130–7.

17. Faunce DE, Stein-Streilein J. NKT Cell-Derived RANTES Recruits APCs and CD8+ T Cells to the Spleen During the Generation of Regulatory T Cells in Tolerance. J Immunol (2002) 169(1):31–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.31

18. D’Orazio TJ, Niederkorn JY. Splenic B Cells are Required for Tolerogenic Antigen Presentation in the Induction of Anterior Chamber-Associated Immune Deviation (ACAID). Immunology (1998) 95(1):47–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00581.x

19. Sonoda KH, Sakamoto T, Qiao H, Hisatomi T, Oshima T, Tsutsumi-Miyahara C, et al. The Analysis of Systemic Tolerance Elicited by Antigen Inoculation Into the Vitreous Cavity: Vitreous Cavity-Associated Immune Deviation. Immunology (2005) 116(3):390–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02239.x

20. Sonoda KH, Stein-Streilein J. Ocular Immune Privilege and CD1d-Reactive Natural Killer T Cells. Cornea (2002) 21(2 Suppl 1):S33–8. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200203001-00008

21. Wenkel H, Streilein JW. Analysis of Immune Deviation Elicited by Antigens Injected Into the Subretinal Space. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (1998) 39(10):1823–34.

22. Jiang LQ, Jorquera M, Streilein JW. Subretinal Space and Vitreous Cavity as Immunologically Privileged Sites for Retinal Allografts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (1993) 34(12):3347–54.

23. Zamiri P, Masli S, Kitaichi N, Taylor AW, Streilein JW. Thrombospondin Plays a Vital Role in the Immune Privilege of the Eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2005) 46(3):908–19. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0362

24. Taylor AW. Review of the Activation of TGF-Beta in Immunity. J Leukoc Biol (2009) 85(1):29–33. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708415

25. Qiao H, Lucas K, Stein-Streilein J. Retinal Laser Burn Disrupts Immune Privilege in the Eye. Am J Pathol (2009) 174(2):414–22. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080766

26. Lucas K, Karamichos D, Mathew R, Zieske JD, Stein-Streilein J. Retinal Laser Burn-Induced Neuropathy Leads to Substance P-Dependent Loss of Ocular Immune Privilege. J Immunol (2012) 189(3):1237–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103264

27. Sugita S, Horie S, Nakamura O, Futagami Y, Takase H, Keino H, et al. Retinal Pigment Epithelium-Derived CTLA-2alpha Induces TGFbeta-Producing T Regulatory Cells. J Immunol (2008) 181(11):7525–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7525

28. Kawazoe Y, Sugita S, Keino H, Yamada Y, Imai A, Horie S, et al. Retinoic Acid From Retinal Pigment Epithelium Induces T Regulatory Cells. Exp Eye Res (2012) 94(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.11.002

29. Imai A, Sugita S, Kawazoe Y, Horie S, Yamada Y, Keino H, et al. Immunosuppressive Properties of Regulatory T Cells Generated by Incubation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells With Supernatants of Human RPE Cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2012) 53(11):7299–309. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10182

30. Aderem A, Underhill DM. Mechanisms of Phagocytosis in Macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol (1999) 17:593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593

31. Sugita S, Kawazoe Y, Imai A, Usui Y, Iwakura Y, Isoda K, et al. Mature Dendritic Cell Suppression by IL-1 Receptor Antagonist on Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2013) 54(5):3240–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11483

32. Gregerson DS, Sam TN, McPherson SW. The Antigen-Presenting Activity of Fresh, Adult Parenchymal Microglia and Perivascular Cells From Retina. J Immunol (2004) 172(11):6587–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6587

33. Tu Z, Li Y, Smith D, Doller C, Sugita S, Chan CC, et al. Myeloid Suppressor Cells Induced by Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Inhibit Autoreactive T-Cell Responses That Lead to Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2012) 53(2):959–66. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8377

34. Ohta K, Yamagami S, Taylor AW, Streilein JW. IL-6 Antagonizes TGF-Beta and Abolishes Immune Privilege in Eyes With Endotoxin-Induced Uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2000) 41(9):2591–9.

35. Lau CH, Taylor AW. The Immune Privileged Retina Mediates an Alternative Activation of J774A.1 Cells. Ocul Immunol Inflamm (2009) 17(6):380–9. doi: 10.3109/09273940903118642

36. Zamiri P, Masli S, Streilein JW, Taylor AW. Pigment Epithelial Growth Factor Suppresses Inflammation by Modulating Macrophage Activation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2006) 47(9):3912–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1267

37. Kawanaka N, Taylor AW. Localized Retinal Neuropeptide Regulation of Macrophage and Microglial Cell Functionality. J Neuroimmunol (2011) 232(1-2):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.09.025

38. Sparrow JR, Hicks D, Hamel CP. The Retinal Pigment Epithelium in Health and Disease. Curr Mol Med (2010) 10(9):802–23. doi: 10.2174/156652410793937813

39. Kiser PD, Golczak M, Palczewski K. Chemistry of the Retinoid (Visual) Cycle. Chem Rev (2014) 114(1):194–232. doi: 10.1021/cr400107q

40. Binder S, Stanzel BV, Krebs I, Glittenberg C. Transplantation of the RPE in AMD. Prog Retin Eye Res (2007) 26(5):516–54. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.02.002

41. Bairati A Jr., Orzalesi N. The Ultrastructure of the Pigment Epithelium and of the Photoreceptor-Pigment Epithelium Junction in the Human Retina. J Ultrastruct Res (1963) 41:484–96. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5320(63)80080-5

42. Booij JC, Baas DC, Beisekeeva J, Gorgels TG, Bergen AA. The Dynamic Nature of Bruch’s Membrane. Prog Retin Eye Res (2010) 29(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.003

43. Naylor A, Hopkins A, Hudson N, Campbell M. Tight Junctions of the Outer Blood Retina Barrier. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 21(1):211. doi: 10.3390/ijms21010211

44. Rizzolo LJ, Peng S, Luo Y, Xiao W. Integration of Tight Junctions and Claudins With the Barrier Functions of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res (2011) 30(5):296–323. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.06.002

45. Konrad M, Schaller A, Seelow D, Pandey AV, Waldegger S, Lesslauer A, et al. Mutations in the Tight-Junction Gene Claudin 19 (CLDN19) are Associated With Renal Magnesium Wasting, Renal Failure, and Severe Ocular Involvement. Am J Hum Genet (2006) 79(5):949–57. doi: 10.1086/508617

46. Lehmann GL, Benedicto I, Philp NJ, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Plasma Membrane Protein Polarity and Trafficking in RPE Cells: Past, Present and Future. Exp Eye Res (2014) 126:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.04.021

47. Cunha-Vaz J, Bernardes R, Lobo C. Blood-Retinal Barrier. Eur J Ophthalmol (2011) 21:S3–9. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2010.6049

48. Burke JM. Epithelial Phenotype and the RPE: Is the Answer Blowing in the Wnt? Prog Retin Eye Res (2008) 27(6):579–95. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.08.002

49. Zhang J, Choi EH, Tworak A, Salom D, Leinonen H, Sander CL, et al. Photic Generation of 11-Cis-Retinal in Bovine Retinal Pigment Epithelium. J Biol Chem (2019) 294(50):19137–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011169

50. Jin M, Li S, Moghrabi WN, Sun H, Travis GH. Rpe65 is the Retinoid Isomerase in Bovine Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Cell (2005) 122(3):449–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.042

51. Strauss O. The Retinal Pigment Epithelium. In: Kolb H, Fernandez E, Nelson R, editors. Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System. Salt Lake City (UT): Webvision John Moran Eye Center (1995).

52. Kniesel U, Wolburg H. Tight Junction Complexity in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium of the Chicken During Development. Neurosci Lett (1993) 149(1):71–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90350-T

53. Rezai KA, Lappas A, Kohen L, Wiedemann P, Heimann K. Comparison of Tight Junction Permeability for Albumin in Iris Pigment Epithelium and Retinal Pigment Epithelium In Vitro. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (1997) 235(1):48–55. doi: 10.1007/BF01007837

54. Liu L, Liu X. Roles of Drug Transporters in Blood-Retinal Barrier. Adv Exp Med Biol (2019) 1141:467–504. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-7647-4_10

55. Tsang SH, Sharma T. Drug-Induced Retinal Toxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol (2018) 1085:227–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-95046-4_48

56. Park SW, Kim JH, Mook-Jung I, Kim KW, Park WJ, Park KH, et al. Intracellular Amyloid Beta Alters the Tight Junction of Retinal Pigment Epithelium in 5XFAD Mice. Neurobiol Aging (2014) 35(9):2013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.008

57. Park SW, Kim JH, Park SM, Moon M, Lee KH, Park KH, et al. RAGE Mediated Intracellular Abeta Uptake Contributes to the Breakdown of Tight Junction in Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Oncotarget (2015) 6(34):35263–73. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5894

58. Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, Ianchulev S, Adamis AP. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic Strategies. Surv Ophthalmol (2003) 48(3):257–93. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(03)00030-4

59. Bhutto I, Lutty G. Understanding Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): Relationships Between the Photoreceptor/Retinal Pigment Epithelium/Bruch’s Membrane/Choriocapillaris Complex. Mol Aspects Med (2012) 33(4):295–317. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.04.005

60. Cunha-Vaz J, Leite E, Sousa JC, de Abreu JR. Blood-Retinal Barrier Permeability and its Relation to Progression of Retinopathy in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. A Four-Year Follow-Up Study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (1993) 231(3):141–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00920936

61. Jo DH, Yun JH, Cho CS, Kim JH, Kim JH, Cho CH. Interaction Between Microglia and Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Determines the Integrity of Outer Blood-Retinal Barrier in Diabetic Retinopathy. Glia (2019) 67(2):321–31. doi: 10.1002/glia.23542

62. Ponnalagu M, Subramani M, Jayadev C, Shetty R, Das D. Retinal Pigment Epithelium-Secretome: A Diabetic Retinopathy Perspective. Cytokine (2017) 95:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.02.013

63. Xu HZ, Le YZ. Significance of Outer Blood-Retina Barrier Breakdown in Diabetes and Ischemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2011) 52(5):2160–4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6518

64. Sood G, Patel BC. Uveitic Macular Edema. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2021). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562158/.

65. Storti F, Klee K, Todorova V, Steiner R, Othman A, van der Velde-Visser S, et al. Impaired ABCA1/ABCG1-Mediated Lipid Efflux in the Mouse Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE) Leads to Retinal Degeneration. Elife (2019) 8:e45100. doi: 10.7554/eLife.45100

66. Radtke ND, Aramant RB, Petry HM, Green PT, Pidwell DJ, Seiler MJ. Vision Improvement in Retinal Degeneration Patients by Implantation of Retina Together With Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Am J Ophthalmol (2008) 146(2):172–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.009

67. Binder S, Krebs I, Hilgers RD, Abri A, Stolba U, Assadoulina A, et al. Outcome of Transplantation of Autologous Retinal Pigment Epithelium in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Prospective Trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2004) 45(11):4151–60. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0118

68. O’Koren EG, Yu C, Klingeborn M, Wong AYW, Prigge CL, Mathew R, et al. Microglial Function Is Distinct in Different Anatomical Locations During Retinal Homeostasis and Degeneration. Immunity (2019) 50(3):723–37e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.02.007

69. Barkana Y, Belkin M. Laser Eye Injuries. Surv Ophthalmol (2000) 44(6):459–78. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00112-0

70. Ajudua S, Mello MJ. Shedding Some Light on Laser Pointer Eye Injuries. Pediatr Emerg Care (2007) 23(9):669–72. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31814b2dc4

71. Marshall J, O’Hagan JB, Tyrer JR. Eye Hazards of Laser ‘Pointers’ in Perspective. Br J Ophthalmol (2016) 100(5):583–4. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308798

72. Marshall J, Bird AC. A Comparative Histopathological Study of Argon and Krypton Laser Irradiations of the Human Retina. Br J Ophthalmol (1979) 63(10):657–68. doi: 10.1136/bjo.63.10.657

73. Wallow IH. Repair of the Pigment Epithelial Barrier Following Photocoagulation. Arch Ophthalmol (1984) 102(1):126–35. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030104047

74. Takahashi K, Lam TT, Fu J, Tso MO. The Effect of High-Dose Methylprednisolone on Laser-Induced Retinal Injury in Primates: An Electron Microscopic Study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (1997) 235(11):723–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01880672

75. Ng TF, Turpie B, Masli S. Thrombospondin-1-Mediated Regulation of Microglia Activation After Retinal Injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2009) 50(11):5472–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2877

76. Eter N, Engel DR, Meyer L, Helb HM, Roth F, Maurer J, et al. In Vivo Visualization of Dendritic Cells, Macrophages, and Microglial Cells Responding to Laser-Induced Damage in the Fundus of the Eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2008) 49(8):3649–58. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1322

77. Liu J, Copland DA, Horie S, Wu WK, Chen M, Xu Y, et al. Myeloid Cells Expressing VEGF and Arginase-1 Following Uptake of Damaged Retinal Pigment Epithelium Suggests Potential Mechanism That Drives the Onset of Choroidal Angiogenesis in Mice. PloS One (2013) 8(8):e72935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072935

78. Richardson PR, Boulton ME, Duvall-Young J, McLeod D. Immunocytochemical Study of Retinal Diode Laser Photocoagulation in the Rat. Br J Ophthalmol (1996) 80(12):1092–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.12.1092

79. Wittchen ES, Nishimura E, McCloskey M, Wang H, Quilliam LA, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, et al. Rap1 GTPase Activation and Barrier Enhancement in Rpe Inhibits Choroidal Neovascularization In Vivo. PloS One (2013) 8(9):e73070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073070

80. Krause TA, Alex AF, Engel DR, Kurts C, Eter N. VEGF-Production by CCR2-Dependent Macrophages Contributes to Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization. PloS One (2014) 9(4):e94313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094313

81. Nagai N, Oike Y, Izumi-Nagai K, Koto T, Satofuka S, Shinoda H, et al. Suppression of Choroidal Neovascularization by Inhibiting Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme: Minimal Role of Bradykinin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2007) 48(5):2321–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1296

82. Horai R, Caspi RR. Cytokines in Autoimmune Uveitis. J Interferon Cytokine Res (2011) 31(10):733–44. doi: 10.1089/jir.2011.0042

83. Zhong Z, Su G, Kijlstra A, Yang P. Activation of the Interleukin-23/Interleukin-17 Signalling Pathway in Autoinflammatory and Autoimmune Uveitis. Prog Retin Eye Res (2021) 80:100866. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100866

84. Taylor AW, Yee DG, Nishida T, Namba K. Neuropeptide Regulation of Immunity. The Immunosuppressive Activity of Alpha-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (Alpha-MSH). Ann N Y Acad Sci (2000) 917:239–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05389.x

85. Nakamura H, Yamaki K, Kondo I, Sakuragi S. Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis Induced by Immunization With Retinal Pigment Epithelium-Specific 65-kDa Protein Peptides. Curr Eye Res (2005) 30(8):673–80. doi: 10.1080/02713680590968330

86. Caspi RR, Roberge FG, Chan CC, Wiggert B, Chader GJ, Rozenszajn LA, et al. A New Model of Autoimmune Disease. Experimental Autoimmune Uveoretinitis Induced in Mice With Two Different Retinal Antigens. J Immunol (1988) 140(5):1490–5.

87. Ohta K, Wiggert B, Yamagami S, Taylor AW, Streilein JW. Analysis of Immunomodulatory Activities of Aqueous Humor From Eyes of Mice With Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis. J Immunol (2000) 164(3):1185–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1185

88. Lee DJ, Taylor AW. Recovery From Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis Promotes Induction of Antiuveitic Inducible Tregs. J Leukoc Biol (2015) 97(6):1101–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A1014-466RR

89. McMenamin PG, Forrester JV, Steptoe R, Dua HS. Ultrastructural Pathology of Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis in the Rat. Autoimmunity (1993) 16(2):83–93. doi: 10.3109/08916939308993315

90. Chen J, Caspi RR. Clinical and Functional Evaluation of Ocular Inflammatory Disease Using the Model of Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis. Methods Mol Biol (2019) 1899:211–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8938-6_15

91. Ng TF, Manhapra A, Cluckey D, Choe Y, Vajram S, Taylor AW. Melanocortin 5 Receptor Expression and Recovery of Ocular Immune Privilege After Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm (2021) 22:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1849735

92. Xu H, Rizzo LV, Silver PB, Caspi RR. Uveitogenicity is Associated With a Th1-Like Lymphokine Profile: Cytokine-Dependent Modulation of Early and Committed Effector T Cells in Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis. Cell Immunol (1997) 178(1):69–78. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1121

93. Heng JS, Hackett SF, Stein-O’Brien GL, Winer BL, Williams J, Goff LA, et al. Comprehensive Analysis of a Mouse Model of Spontaneous Uveoretinitis Using Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019) 116(52):26734–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915571116

94. Caspi RR, Chan CC, Grubbs BG, Silver PB, Wiggert B, Parsa CF, et al. Endogenous Systemic IFN-Gamma has a Protective Role Against Ocular Autoimmunity in Mice. J Immunol (1994) 152(2):890–9.

95. Jones LS, Rizzo LV, Agarwal RK, Tarrant TK, Chan CC, Wiggert B, et al. IFN-Gamma-Deficient Mice Develop Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis in the Context of a Deviant Effector Response. J Immunol (1997) 158(12):5997–6005.

96. Yoshimura T, Sonoda KH, Miyazaki Y, Iwakura Y, Ishibashi T, Yoshimura A, et al. Differential Roles for IFN-Gamma and IL-17 in Experimental Autoimmune Uveoretinitis. Int Immunol (2008) 20(2):209–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm135

97. Luger D, Silver PB, Tang J, Cua D, Chen Z, Iwakura Y, et al. Either a Th17 or a Th1 Effector Response can Drive Autoimmunity: Conditions of Disease Induction Affect Dominant Effector Category. J Exp Med (2008) 205(4):799–810. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071258

98. Pennesi G, Mattapallil MJ, Sun SH, Avichezer D, Silver PB, Karabekian Z, et al. A Humanized Model of Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis in HLA Class II Transgenic Mice. J Clin Invest (2003) 111(8):1171–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI15155

99. Okunuki Y, Mukai R, Nakao T, Tabor SJ, Butovsky O, Dana R, et al. Retinal Microglia Initiate Neuroinflammation in Ocular Autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2019) 116(20):9989–98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820387116

100. Lee DJ, Taylor AW. Both MC5r and A2Ar are Required for Protective Regulatory Immunity in the Spleen of Post-Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis in Mice. J Immunol (2013) 191(8):4103–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300182

101. Gordon S. The Macrophage: Past, Present and Future. Eur J Immunol (2007) 37:S9–17. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737638

102. Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Schioppa T, Saccani A, Allavena P, et al. Infiltration of Tumours by Macrophages and Dendritic Cells: Tumour-Associated Macrophages as a Paradigm for Polarized M2 Mononuclear Phagocytes. Novartis Found Symp (2004) 256:137–45. discussion 46-8, 259-69.

103. Mo JS, Streilein JW. Immune Privilege Persists in Eyes With Extreme Inflammation Induced by Intravitreal LPS. Eur J Immunol (2001) 31(12):3806–15. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200112)31:12<3806::AID-IMMU3806>3.0.CO;2-M

104. Mantegazza AR, Magalhaes JG, Amigorena S, Marks MS. Presentation of Phagocytosed Antigens by MHC Class I and II. Traffic (2013) 14(2):135–52. doi: 10.1111/tra.12026

105. Wang E, Choe Y, Ng TF, Taylor AW. Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Suppress Phagolysosome Activation in Macrophages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2017) 58(2):1266–73. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-21082

106. Taylor AW, Dixit S, Yu J. Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cell Line Suppression of Phagolysosome Activation. Int J Ophthalmol Eye Sci (2015) Suppl 2(1):1–6. doi: 10.19070/2332-290X-SI02001

107. Phan TA, Taylor AW. The Neuropeptides Alpha-MSH and NPY Modulate Phagocytosis and Phagolysosome Activation in RAW 264.7 Cells. J Neuroimmunol (2013) 260(1-2):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.04.019

108. Taylor AW. The Immunomodulating Neuropeptide Alpha-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (Alpha-MSH) Suppresses LPS-Stimulated TLR4 With IRAK-M in Macrophages. J Neuroimmunol (2005) 162(1-2):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.01.008

109. Li D, Taylor AW. Diminishment of Alpha-MSH Anti-Inflammatory Activity in MC1r siRNA-Transfected RAW264.7 Macrophages. J Leukoc Biol (2008) 84(1):191–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0707463

110. Benque IJ, Xia P, Shannon R, Ng TF, Taylor AW. The Neuropeptides of Ocular Immune Privilege, Alpha-MSH and NPY, Suppress Phagosome Maturation in Macrophages. Immunohorizons (2018) 2(10):314–23. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1800049

111. Taylor AW, Lee D. Applications of the Role of Alpha-MSH in Ocular Immune Privilege. Adv Exp Med Biol (2010) 2010:681:143–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6354-3_12

112. Clemson CM, Yost J, Taylor AW. The Role of Alpha-MSH as a Modulator of Ocular Immunobiology Exemplifies Mechanistic Differences Between Melanocortins and Steroids. Ocul Immunol Inflamm (2017) 25(2):179–89. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2015.1092560

113. Kitaichi N, Namba K, Taylor AW. Inducible Immune Regulation Following Autoimmune Disease in the Immune-Privileged Eye. J Leukoc Biol (2005) 77(4):496–502. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204114

114. Lee DJ, Taylor AW. Following EAU Recovery There is an Associated MC5r-Dependent APC Induction of Regulatory Immunity in the Spleen. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2011) 52(12):8862–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8153

115. Lee DJ, Preble J, Lee S, Foster CS, Taylor AW. MC5r and A2Ar Deficiencies During Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis Identifies Distinct T Cell Polarization Programs and a Biphasic Regulatory Response. Sci Rep (2016) 6:37790. doi: 10.1038/srep37790

116. Spana C, Taylor AW, Yee DG, Makhlina M, Yang W, Dodd J. Probing the Role of Melanocortin Type 1 Receptor Agonists in Diverse Immunological Diseases. Front Pharmacol (2019) 9:1535. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01535

117. Nelson WW, Lima AF, Kranyak J, Opong-Owusu B, Ciepielewska G, Gallagher JR, et al. Retrospective Medical Record Review to Describe Use of Repository Corticotropin Injection Among Patients With Uveitis in the United States. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther (2019) 35(3):182–8. doi: 10.1089/jop.2018.0090

Keywords: ocular immune privilege, immune tolerance, retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE), retinal immunobiology, suppressor macrophages

Citation: Taylor AW, Hsu S and Ng TF (2021) The Role of Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells in Regulation of Macrophages/Microglial Cells in Retinal Immunobiology. Front. Immunol. 12:724601. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.724601

Received: 13 June 2021; Accepted: 28 July 2021;

Published: 13 August 2021.

Edited by:

Alexander Steinkasserer, University Hospital Erlangen, GermanyReviewed by:

Chen Yu, Duke University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Taylor, Hsu and Ng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew W. Taylor, YXd0YXlsb3JAYnUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.