94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 22 October 2021

Sec. Molecular Innate Immunity

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.699563

This article is part of the Research Topic Macrophage Plasticity in Sterile and Pathogen-Induced Inflammation View all 18 articles

Elisa Jentho1,2*

Elisa Jentho1,2* Sebastian Weis2,3*

Sebastian Weis2,3*The ability to remember a previous encounter with pathogens was long thought to be a key feature of the adaptive immune system enabling the host to mount a faster, more specific and more effective immune response upon the reencounter, reducing the severity of infectious diseases. Over the last 15 years, an increasing amount of evidence has accumulated showing that the innate immune system also has features of a memory. In contrast to the memory of adaptive immunity, innate immune memory is mediated by restructuration of the active chromatin landscape and imprinted by persisting adaptations of myelopoiesis. While originally described to occur in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns, recent data indicate that host-derived damage-associated molecular patterns, i.e. alarmins, can also induce an innate immune memory. Potentially this is mediated by the same pattern recognition receptors and downstream signaling transduction pathways responsible for pathogen-associated innate immune training. Here, we summarize the available experimental data underlying innate immune memory in response to damage-associated molecular patterns. Further, we expound that trained immunity is a general component of innate immunity and outline several open questions for the rising field of pathogen-independent trained immunity.

Monocytes and macrophages (Mφ) are professional phagocytotic cells (1), a feature first described by Elie Metchnikoff almost 150 years ago (2). Circulating monocytes originate from the bone marrow and can differentiate into monocyte-derived Mφ and dendritic cells upon stimulation (3, 4) and subsequently elicit a robust inflammatory response, which includes the secretion of cytokines. This qualifies these cells as initiators of inflammation and places them in the first line of defense against invading pathogens (3, 5). In contrast, tissue resident Mφ, derived from the yolk sac or the fetal liver, are thought to regulate organ development and homeostasis as well as to control resolution of inflammation (5, 6). However, this is not a fixed dichotomy and under specific conditions, monocyte-derived Mφ can also acquire a phenotype that promotes homeostasis and tissue repair similar to tissue-resident Mφ (5).

In contrast to adaptive immunity that develops antigen-specific memory, the cellular components of the innate immune system, including monocytes and Mφ, were long thought not to remember previous stimulation. Instead after a transient phase of recovery, it was assumed that they would react in a similar and repetitive way to inflammatory stimuli (7).

The above-described perspective was challenged during the last 15 years by several independent discoveries that showed persistent histone modifications in Mφ in response to the bacterial cell-wall component Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the fungal cell wall component β-1,3-D-glucan among others (8–10). The phenomenon of acquired and persistent alterations of innate immune responses was coined as innate immune memory and presents typically as tolerance, referring to a reduced response or trained immunity (TRIM), referring to an enhanced response upon restimulation (10).

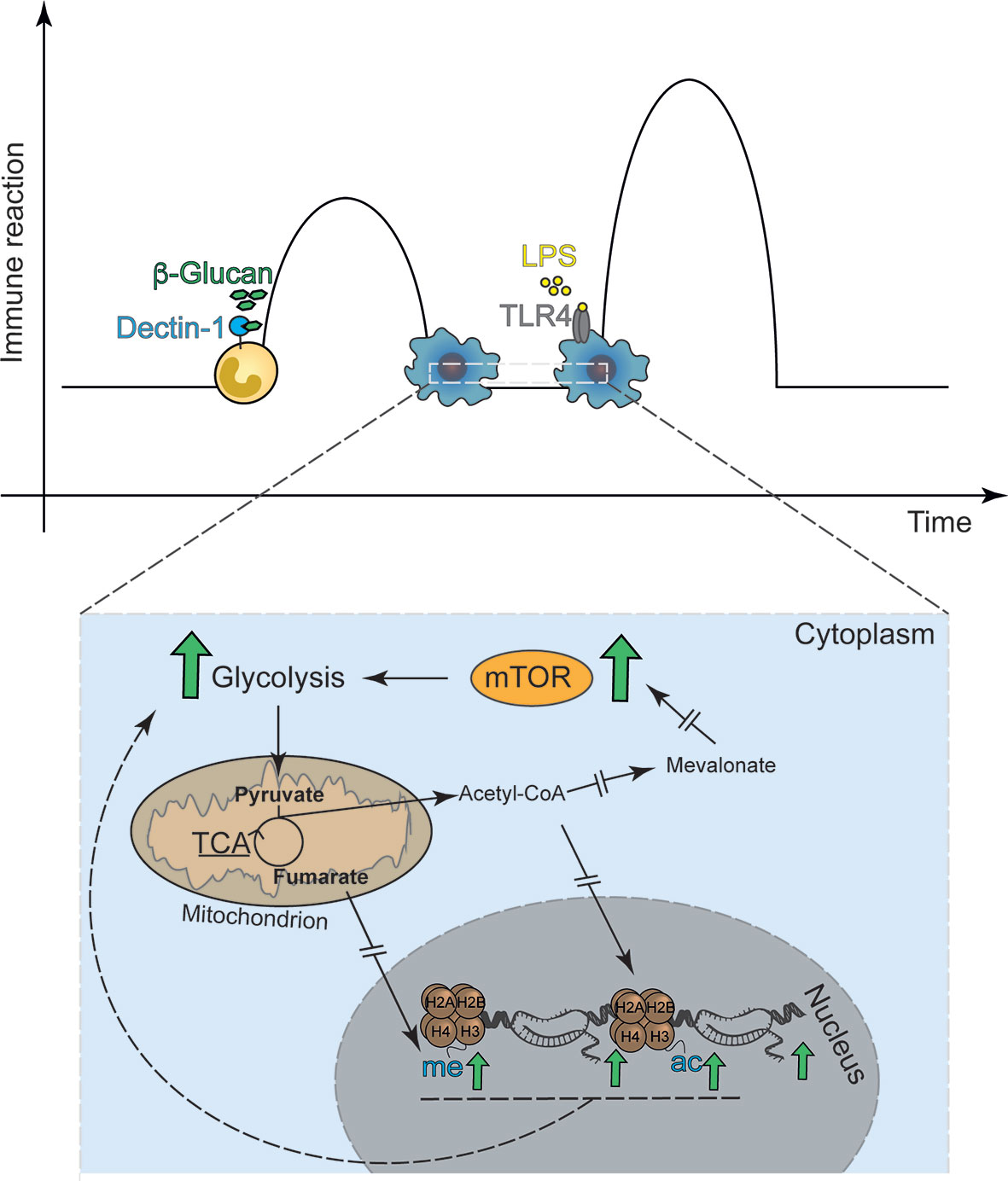

The first observation that LPS-mediated Toll-like receptor (TLR)-signaling induced gene-specific chromatin modifications were made by Foster et al. when aiming to understand immunotolerance (8). The authors revealed a set of gene-specific chromatin modifications that are associated with gene silencing or enhanced response to re-exposure (8). In addition, it was established that a subset of genes could be persistently tolerized while others remained unaffected or even had enhanced transcription, the latter set being described as non-tolerizeable genes. Subsequent work by other groups revealed that the fungal cell wall component β-1,3-D-glucan and other inflammatory stimuli can also induce specific and persistent modifications of histone acetylation and methylation, underlying a long-term modulation of the innate immune response (Figure 1) (9, 11). Both phenomena share common characteristics, e.g., exposure to a given stimuli ensues long-term modulation of the innate immune response to that same or related stimuli and are associated with long-term modification of gene transcription (8, 9). TRIM in vivo and in vitro was first demonstrated using the fungal cell wall component of Candida albicans β-1,3-D-glucan, a bona fide pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) or the Bacille-Calmette Guerin (BCG) the live-bacteria tuberculosis vaccine (9, 11–13). These molecules commonly use the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to induce TRIM to activate specific downstream metabolic adaptations (14, 15). In fact, in myeloid cells, TRIM relies on alterations of the cellular energy metabolism involving glycolysis, itaconate synthesis, glutaminolysis and fumarate metabolism (16–18). While the increase in glycolysis seems to be a shared mechanism between the different trained immunity inducers, the regulation of OXPHOS, e.g. repression or activation, appears to be stimulus-specific. Exposure to β-glucan also leads to increased abundance of histone marks H3K4me3 and H3K27ac especially at promotors of genes encoding proteins regulating glycolysis. In addition, glutaminolysis, which is activated during trained immunity fuels the TCA cycle, accumulating specific metabolites, such as fumarate, which even further increases histone marks at H3K4me3 and H3K27ac. Fumarate, can also directly inhibit the activity of histone demethylases (17) placing it at a central hub to for the metabolic control of β-glucan induced TRIM. Consistently, inhibition of glycolysis and glutaminolysis reduced these histone marks at the promotors of IL6 and TNFA. In addition, increased amounts of mevalonate, a metabolite involved in cholesterol synthesis (18, 19) upregulate the IGF-I signaling pathway, which in turn promotes the activation of the mTOR pathway and glycolysis. This results most likely in the accumulation of acetyl-CoA an important donor for acetyl groups for histone acetylation (20). This data is suggestive for a strong interaction of metabolic and inflammatory pathways, underling trained immunity (14, 17, 18, 21).

Figure 1 Classical in vitro model of trained immunity. Trained immunity describes a functional, metabolic and epigenetic adaptation of innate immune cells to previous stimuli with ensuing increased immune response, i.e. cytokine release, to secondary stimulation. (A) The classical model applies the Dectin-1 agonist β-1,3-D Glucan as the first stimulus and the TLR-4 agonist LPS as the second stimulus. (B) The basis for β-1,3-D Glucan induced trained immunity are metabolic adaptations, including the mTOR signal-transduction enhanced glycolysis. Interrupted errors indicate that many more proteins are involved in the signaling cascade, which are not depicted in the figure.

TRIM can be induced in vivo in mice via a mechanism that is at least partially based on modified hematopoiesis, favoring myelopoiesis and potentially increasing host resistance to infection (22–25).

As described before, LPS tolerance is associated with specific gene silencing or enhanced response to re-exposure (8). It is conceivable that the same would occur in TRIM, i.e. that innate immune training includes not only trainable but also non-trainable genes probably including tolerizeable genes. This raises the possibility that training, and tolerance are not unrelated phenomena but rather dependent on the re-writing of gene activation and repression programs via specific stimuli-induced signaling pathways to specify the reaction pattern of the innate immune cells. This notion is supported by the finding that LPS-induced histone modifications can be reversed at specific loci by different secondary stimuli (26). We speculated that this regulation underlies why training and tolerance are detrimental in some and protective in other models (14, 22). However, this needs further experimental evidence, which is why we use the TRIM terminology to describe memory that induces enhanced responses.

The prevailing concept since the 1950s that the immune system evolved to distinguish self from non-self was challenged in a seminal essay by Polly Matzinger (27). She proposed that the immune system does not exclusively differentiate between foreign and self but instead evolved to detect cues indicating danger. Matzinger´s danger theory was primarily intended to understand T-cell biology. This theory contains specifically the idea that professional antigen presenting cells are activated “in the presence of tissue destruction” (27). Whether this is a completely novel approach or a reappraisal of earlier thoughts is not the topic of this review (28). According to Matzinger, immune cells are primarily made for sensing detecting danger and only sense invading microorganisms for the reason that infections typically are associated with danger, in the form of cellular stress and damage (27, 29). In the classical concept of immune recognition, DAMPs would in fact be considered as “self”. However, it has become clear that certain host-derived molecules can activate innate immunity and induce an inflammatory response regardless whether they are triggered by infection or by sterile inflammation (30). These molecules have been designated as damage or danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) and are also referred to as alarmins by some authors. An overview of the different terminology is shown in Table 1.

Overall, DAMPs are a rather heterogenous group of molecules with shared common features. They are a) host-derived and not pathogen- or environment-derived and b) induce an innate immune response. In order to acknowledge their heterogeneity, DAMPs have recently been further subclassified as continuous DAMPs (cDAMPs), inducible DAMPs (iDAMPs) (Table 1) (42, 43). In this classification, cDAMPs are intracellular molecules that are not present in the circulation under non-pathological conditions and are set-free without modifications upon cellular damage. iDAMPs are secreted and/or induced molecules, released from dying cells and have been proposed to reflect various stress and damage pathways activated during stress (43). DAMPs are heterogenous in their origin and function. Yet, they induce a rather homogenous sterile inflammation that equally involves cytokine release, neutrophil recruitment and the induction of T-cell immunity equally to the response elicited by PAMPs (30). The recently classified group of lifestyles—associated molecular patterns (LAMP) consist of molecules increased with western lifestyle hat induce a sterile inflammation. These are distinct from DAMPs as they cannot be cleared, and if persistent, lead to a chronic inflammation. This group includes cholesterol, monosodium urate or oxidized LDL and others (42) (Table 2).

Monocytes and Mφ express different sets of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that bind to PAMPs (50) and DAMPs (51–53). There are four distinct classes of PRR that are identified so far: Toll-like receptors (TLR), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)- Leucine-rich repeats (LRR)-containing receptors (NLR), retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-1) -like receptors (RLR), and the C-type lectin receptors (CLR) (54). Binding of PAMPs and DAMPs by PRRs triggers distinct signaling transduction pathways which elicit the expression of immunomodulatory molecules, e.g. cytokines, indispensable for an appropriate immune reaction against an exogenous or endogenous threat.

TRIM can be induced by different classes of PRRs, as illustrated by β-glucan, which binds to the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 activating the noncanonical Raf-1 pathway signaling (12). So far only one intracellular PRR has been identified to result in TRIM upon engagement, namely, NOD-2/Rip2 in response to BCG (11). This is fundamentally different to the immunological tolerance which involves TLR-4 activation and the NF-κB/MAPK pathway (55). We here posit that DAMP-induced TRIM shall not involve cytoplasmatic PRR such as NLR or RIG-1. This is because by definition, a DAMP is an endogenous, i.e. cytoplasmatic or nucleic, molecule that is released in the circulation and then bound by extracellular receptors, with the potential to be endocytosed after ligand-binding (56). In contrast, cell intrinsic stress responses mount conserved stress-control pathways that prevent tissue damage (57). the release of DAMPs and as a consequence also the ensuing activation of the immunes system.

Compared to PAMP-induced TRIM, DAMP-induced TRIM is less well studied and understood. Five years ago, Crisan et al. had speculated on the existence on DAMP-induced trained immunity and summarized concepts and early data (58). During the last years, increasing amounts of evidence shows that endogenous molecules promote in fact TRIM include the iron-containing tetrapyrrole heme (22), the intermediate filament vimentin (45), oxidized low-density-lipoproteins (oxLDL) (46) and the mineralocorticoid aldosterone (59). An overview of the studies is provided in Table 2. As aldosterone is a hormone and not considered a DAMP, it will not be discussed further in this review.

Both heme and vimentin are alarmins that can activate PRR signaling either by TLR-4 or Dectin-1, respectively (37, 38). OxLDLs are a heterogenous group of molecules that, depending on their oxidation status, bind to different PRR. Minimally modified LDL can directly bind to cluster of differentiation (CD)14, TLR-2 and -4 triggering immune activation (48, 60, 61). Further oxidized OxLDL is recognized by a family of scavenger receptors including the lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1), CD36 and the scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) (62). In the following paragraphs we will briefly summarize the findings for the individual TRIM-promoting DAMPs.

Heme is a tetrapyrrole with a central iron atom found in hemoglobin and other hemoproteins. The reactive central iron, which is responsible for the biological heme functions can reversibly change its oxidation state from ferric (Fe3+) to ferrous (Fe2+) to accept or donate electrons, respectively. This reactive core makes heme not only an indispensable molecule for many physiological processes, but it also bears the risk for cytotoxicity when unbound to proteins. As such, heme is able to oxidize lipids and proteins and can induce DNA damage (63, 64). Additionally, heme can promote the generation of free radicals e.g. when reacting with other organic hydroperoxides, further imposing cellular damage (63, 64). Under homeostatic conditions heme production and degradation are tightly controlled processes. Following hemolysis or tissue damage, heme is passively released into the circulation. There it is bound non-covalently by serum scavenger proteins and taken up by Mφ (65–70). As far as we know now, there is no active heme export.

With increasing concentrations, the buffering capacity of serum protein becomes exhausted resulting in the accumulation of cell-free, ‘labile’ heme in the plasma (70, 71). This contributes critically to the pathogenesis of severe acute infectious disease, as demonstrated for malaria (72) and for bacterial sepsis (73–75). Labile heme is a pro-type alarmin that is sensed by TLR-4 but also activates the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) pathway both inducing cytokine expression, including the cytokines IL-6 and pro-IL-1β in innate immune cells (37, 76). As heme synergized with LPS with regards to cytokine release, it was assumed that heme would bind to a distinct pocket of TLR-4 and specifically induced MyD88 signaling (77). How heme triggers Syk signaling is currently unknown (37, 76, 78). We have recently described that heme is a potent inducer of TRIM which is mediated by the activation of Syk (22). In contrast to other TRIM inducers this is independent of mTOR. However, in vivo heme training causes comparable expansion of myeloid primed long-term hematopoietic stem cells as seen in PAMP-induced TRIM (19, 79).

In line with the above, Schrum et al. identified that damaged red blood cells and hemozoin crystals, as a result of a malaria-inducing Plasmodium falciparum infection, induce TRIM in primary monocytes in vitro (80). Plasmodium spp. replicate in erythrocytes and regularly disrupt their cell membrane to be released into the circulation which is accompanied by the release of the Plasmodium -metabolic byproduct hemozoin (81, 82). This study perceives the Plasmodium induced TRIM to be a result of PAMPs and does not consider that damaged red blood cells as well as hemozoin are major sources of labile heme. Together with the findings of Jentho et al. (22), TRIM seems to be an inherent component of innate immune cells considering the wide range of infections associated to release of labile heme. Given the human-pathogen co-evolution especially with Plasmodium spp. these studies raise the question what kind of evolutionary advantage is achieved by inducing TRIM.

Oxidized LDL encompasses a number of different particles such as protein and fatty acids with varying oxidation states (83, 84). Application of in vitro oxLDL induces TRIM in Mφ, as well as in non-hematopoietic lineage cells such as endothelial cells and human coronary smooth muscle cells (46, 48, 49). OxLDL bind to a family of scavenger receptors that include CD36 (62) which in turn can activate TLR-4 and TLR-6 signaling (85). Mechanistically, as seen in β-glucan, oxLDL-TRIM is associated with mTOR signaling, H3K4 methylation and increased glycolysis (46, 86). The same, sensing by TLR and signaling via mTOR pathways are involved in TRIM in vascular smooth muscle cells (48). Potentially this explains why training effects by oxLDL have been shown for non-myeloid tissues that also express the same receptors. In fact, this should also hold true for the other mediators of TRIM, but this, to our knowledge, has not been addressed experimentally

OxLDL may, however, also be considered in light of the recently suggested concept of LAMPs, which refers to molecules not associated with pathogens or cellular damage but instead arising from “failure-to-adapt-disease” such as observed in the context of atherosclerosis or gout. Key features of LAMPs have been defined as being persistent and having the ability to induce chronic disease (42). Furthermore, oxLDL cannot be cleared by the immune system and consequently induce chronic inflammation (30). We consider this potentially relevant for this topic as acute oxLDL exposure induces TRIM (46, 49), while LAMP-induced TRIM would involve a non-resolved stimulus and persistent activation, with the associated pro-inflammatory phenotype in phagocytes. Whether the observed link between high-fat diet, the predominant factor for the development of atherosclerosis, NLRP-3 inflammasome-dependent induction of TRIM in mice (87) is also mediated by oxLDL signaling is currently unclear.

Vimentin is an intermediate filament protein involved in inflammatory responses and in Mφ endocytosis (88). Vimentin is a classical alarmin, sensed by Dectin-1 (38). While investigating donor allografts in a model of heart transplantation Braza et al. showed in the ex vivo second hit model, that isolated Mφ exposed to first vimentin and subsequent to HMGB-1 had an enhanced cytokine release of TNF and IL-6 (45). HMGB-1 is a DNA chaperone that mainly signals via extracellular receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), a DAMP-specific receptor that also recognized S100 members and TLR-4 (89). This experimental set-up detaches the phenomenon of TRIM from any pathogen and clearly links it to sterile inflammation (30). However, as a limitation the authors here only provide direct ex vivo data and do not show whether each single component or a switched cadence would equally result in enhanced cytokine release. Of note, data using isolated splenocytes that were incubated first with HMGB-1 for eight days and then subsequently stimulated with LPS had a six-fold increase of TNF release in contrast to non-HMGB-1 exposed cells (90). While in this setting it is possible that HMGB-1 provides a continuous stimulation, the long protocol also could suggest that HMGB-1 can act as a trainer.

In this review, we describe DAMPs for which it was experimentally shown that they induce innate immune training. We also want to highlight, that at least in our hands, exposure to certain other DAMPs does not lead to trained immunity. Potentially, this was also observed in other laboratories but not reported. This could indicate shared characteristic of those DAMPs that induce TRIM, which still have to be identified. Exemplarily, we were not able to induce innate immune training with the short-lived ATP that binds to P2YR and P2XR and provokes immune activation in other models (91). The lack of ATP-induced TRIM might be explained by the fact that ATP does not bind the classical PRRs in contrast to the TRIM-inducing DAMPs. Furthermore, it is unclear, at least in the in vitro models, whether Mφ can clear TRIM-inducing DAMPs or their degradation products, whereas ATP for example is rapidly used by the cell and cleared (91).

In his introduction to the Cold Spring Harbour Symposium in 1989 Charles Janeway introduced the idea of PRR and the necessity of a two-signal system for immune activation (31). In subsequent work he proposed that a danger signal from the host is in fact a co-stimulation for the host that can act additionally to the classical pathogen-derived co-stimulation providing the needed signal two (92). While activation of adaptive immunity requires signals from two cells, in the evolutionarily older innate immune cell, no such co-stimulation existed and a meaningful second signal could have come from a different endogenous source. This could be the evolutionary justification for the observed phenomenon of innate immune memory. The changes in the bone marrow might be the reflection of the long-term consequences as cellular memory might evolutionarily not have yet been possible due to a lack of adaptive immunity. Why some DAMPs can act as signal one while others do not, remains to be established.

Over the last 15 years it has become clear that memory is a general feature of innate immunity. Strikingly, DAMP- and PAMP-induced trained immunity show comparable molecular reaction pattern. Recognition of both induce histone modifications and long-term persistent alteration of myelopoiesis that impact on the immune response upon secondary stimulation. This coherence hints towards an evolutionary conserved program, with logical advantages and so far, not understood disadvantages for the host mounting a secondary inflammatory program. Yet, it remains unclear under which conditions it is beneficial and when it is deleterious. This needs to be addressed for future application of the TRIM concept especially if applied in clinical settings.

Several further questions remain to us. Why are certain DAMPs worth remembering while others apparently not? How does DAMP-induced TRIM affect leukocyte trafficking, adaptive immunity, iNKT cell regulation and repair? Especially as damage signaling should result in the induction of a repair response. Is there an intracellular signaling funnel via which this reaction pattern is transmitted or can only DAMPs that can activate extracellular PRR-signaling lead to innate immune training? If intracellular PRR recognize DAMPs and initiate innate immune training, how would a constant immune activation be prevented? And ultimately does an epigenetic imprinting in the myeloid compartment have an evolutionary advantage to defend against pathogens? We are confident that the next years will shed light on some of these questions.

EJ and SW wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

There was no specific funding for this review. EJ is currently funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany´s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2051 – Project-ID 390713860. SW is currently funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG, project number WE 4971/6-1 and The Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) project number 01EN2001.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Boris Novakovic, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia for insightful comments on the manuscript.

1. Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and Pathogenic Functions of Macrophage Subsets. Nat Rev Immunol (2011) 11(11):723–37. doi: 10.1038/nri3073

2. Metschnikow E. Untersuchungen Über Die Mesodermalen Phagocyten Einiger Wirbeltiere. Biol Zbl (1883) 3(18):560–5.

3. Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, et al. Monitoring of Blood Vessels and Tissues by a Population of Monocytes With Patrolling Behavior. Science (2007) 317(5838):666–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883

4. Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood Monocytes: Development, Heterogeneity, and Relationship With Dendritic Cells. Annu Rev Immunol (2009) 27:669–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557

5. Watanabe S, Alexander M, Misharin AV, Budinger GRS. The Role of Macrophages in the Resolution of Inflammation. J Clin Invest (2019) 129(7):2619–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI124615

6. Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and Macrophages: Developmental Pathways and Tissue Homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14(6):392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671

7. Fearon DT, Locksley RM. The Instructive Role of Innate Immunity in the Acquired Immune Response. Science (1996) 272(5258):50–3. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.50

8. Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-Specific Control of Inflammation by TLR-Induced Chromatin Modifications. Nature (2007) 447(7147):972–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05836

9. Saeed S, Quintin J, Kerstens HH, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Matarese F, et al. Epigenetic Programming of Monocyte-to-Macrophage Differentiation and Trained Innate Immunity. Science (2014) 345(6204):1251086. doi: 10.1126/science.1251086

10. Divangahi M, Aaby P, Khader SA, Barreiro LB, Bekkering S, Chavakis T, et al. Trained Immunity, Tolerance, Priming and Differentiation: Distinct Immunological Processes. Nat Immunol (2021) 22(1):2–6. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00845-6

11. Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F, Joosten LA, Jacobs C, Xavier RJ, et al. BCG-Induced Trained Immunity in NK Cells: Role for non-Specific Protection to Infection. Clin Immunol (2014) 155(2):213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.10.005

12. Quintin J, Saeed S, Martens JH, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ifrim DC, Logie C, et al. Candida Albicans Infection Affords Protection Against Reinfection via Functional Reprogramming of Monocytes. Cell Host Microbe (2012) 12(2):223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.006

13. Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F, Joosten L, Ifrim D, Saeed S, et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin Induces NOD2-Dependent Nonspecific Protection From Reinfection via Epigenetic Reprogramming of Monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109(43):17537–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109

14. Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, et al. Mtor- and HIF-1alpha-Mediated Aerobic Glycolysis as Metabolic Basis for Trained Immunity. Science (2014) 345(6204):1250684. doi: 10.1126/science.1250684

15. Arts RJW, Carvalho A, La Rocca C, Palma C, Rodrigues F, Silvestre R, et al. Immunometabolic Pathways in BCG-Induced Trained Immunity. Cell Rep (2016) 17(10):2562–71. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.011

16. Dominguez-Andres J, Novakovic B, Li Y, Scicluna BP, Gresnigt MS, Arts RJW, et al. The Itaconate Pathway is a Central Regulatory Node Linking Innate Immune Tolerance and Trained Immunity. Cell Metab (2019) 29(1):211–20.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.09.003

17. Arts RJ, Novakovic B, Ter Horst R, Carvalho A, Bekkering S, Lachmandas E, et al. Glutaminolysis and Fumarate Accumulation Integrate Immunometabolic and Epigenetic Programs in Trained Immunity. Cell Metab (2016) 24(6):807–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.008

18. Bekkering S, Arts RJW, Novakovic B, Kourtzelis I, van der Heijden C, Li Y, et al. Metabolic Induction of Trained Immunity Through the Mevalonate Pathway. Cell (2018) 172(1-2):135–46 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.025

19. Mitroulis I, Ruppova K, Wang B, Chen LS, Grzybek M, Grinenko T, et al. Modulation of Myelopoiesis Progenitors is an Integral Component of Trained Immunity. Cell (2018) 172(1-2):147–61.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.034

20. Ryan DG, O’Neill LAJ. Krebs Cycle Reborn in Macrophage Immunometabolism. Annu Rev Immunol (2020) 38:289–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-081619-104850

21. Mourits VP, van Puffelen JH, Novakovic B, Bruno M, Ferreira AV, Arts RJ, et al. Lysine Methyltransferase G9a is an Important Modulator of Trained Immunity. Clin Transl Immunol (2021) 10(2):e1253. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1253

22. Jentho E, Ruiz-Moreno C, Novakovic B, Kourzelis I, Megchelenbrink W, Martins R, et al. Trained Innate Immunity, Long-Lasting Epigenetic Modulation and Skewed Myelopoiesis by Heme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2021) 118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2102698118

23. Chavakis T, Mitroulis I, Hajishengallis G. Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells as Integrative Hubs for Adaptation to and Fine-Tuning of Inflammation. Nat Immunol (2019) 20(7):802–11. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0402-5

24. Kaufmann E, Sanz J, Dunn JL, Khan N, Mendonca LE, Pacis A, et al. BCG Educates Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Generate Protective Innate Immunity Against Tuberculosis. Cell (2018) 172(1-2):176–90.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.031

25. Cirovic B, de Bree LCJ, Groh L, Blok BA, Chan J, van der Velden W, et al. BCG Vaccination in Humans Elicits Trained Immunity via the Hematopoietic Progenitor Compartment. Cell Host Microbe (2020) 28(2):322–34 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.014

26. Novakovic B, Habibi E, Wang SY, Arts RJW, Davar R, Megchelenbrink W, et al. Beta-Glucan Reverses the Epigenetic State of LPS-Induced Immunological Tolerance. Cell (2016) 167(5):1354–68.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.034

27. Matzinger P. Tolerance, Danger, and the Extended Family. Annu Rev Immunol (1994) 12:991–1045. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.005015

28. Pradeu T, Cooper EL. The Danger Theory: 20 Years Later. Front Immunol (2012) 3:287. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00287

29. Matzinger P. An Innate Sense of Danger. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2002) 961:341–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb03118.x

30. Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile Inflammation: Sensing and Reacting to Damage. Nat Rev Immunol (2010) 10(12):826–37. doi: 10.1038/nri2873

31. Janeway CA Jr. Approaching the Asymptote? Evolution and Revolution in Immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol (1989) 54 Pt 1:1–13. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1989.054.01.003

32. Raetz CR, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide Endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem (2002) 71:635–700. doi: 10.1038/35092620

33. Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune Recognition. A New Receptor for Beta-Glucans. Nature (2001) 413:36–37. doi: 10.1038/35092620

34. Seong SY, Matzinger P. Hydrophobicity: An Ancient Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern that Initiates Innate Immune Responses. Nat Rev Immunol (2004) 4:469–78. doi: 10.1038/nri1372

35. Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, Nakao A, Fink MP, Lotze MT, et al. The Nuclear Factor HMGB1 Mediates Hepatic Injury After Murine Liver Sschemia-Reperfusion. J Exp Med (2005) 201:1135–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042614

36. Idzko M, Ferrari D, Eltzschig HK. Nucleotide Signalling During Inflammation. Nature (2014) 509:310–317. doi: 10.1038/nature13085

37. Figueiredo RT, Fernandez PL, Mourao-Sa DS, Porto BN, Dutra FF, Alves LS, et al. Characterization of Heme as Activator of Toll-Like Receptor 4. J Biol Chem (2007) 282(28):20221–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610737200

38. Thiagarajan PS, Yakubenko VP, Elsori DH, Yadav SP, Willard B, Tan CD, et al. Vimentin is an Endogenous Ligand for the Pattern Recognition Receptor Dectin-1. Cardiovasc Res (2013) 99(3):494–504. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt117

39. Oppenheim JJ, Yang D. Alarmins: Chemotactic Activators of Immune Responses. Curr Opin Immunol (2005) 17:359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.06.002

40. Yang D, Chen Q, Su SB, Zhang P, Kurosaka K, Caspi RR, et al. Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin Acts as an Alarmin to Activate the TLR2-MyD88 Signal Pathway in Dendritic Cells and Enhances Th2 Immune Responses. J Exp Med (2005) 205:79–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062027

41. Mendy B, Wang'ombe MW, Radakovic ZS, Holbein J, Ilyas M, Chopra D, et al. Arabidopsis Leucine-Rich Repeat Receptor-Like Kinase NILR1 Is Required for Induction Of Innate Immunity to Parasitic Nematodes. PLoS Pathog (2017) 13:e1006284. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006284

42. Zindel J, Kubes P. Damps, Pamps, and Lamps in Immunity and Sterile Inflammation. Annu Rev Pathol (2020) 15:493–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012419-032847

43. Yatim N, Cullen S, Albert ML. Dying Cells Actively Regulate Adaptive Immune Responses. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17(4):262–75. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.9

44. Wang X, Wang Y, Antony V, Sun H, Liang G. Metabolism-Associated Molecular Patterns (Mamps). Trends Endocrinol Metab (2020) 31(10):712–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.07.001

45. Braza MS, van Leent MMT, Lameijer M, Sanchez-Gaytan BL, Arts RJW, Perez-Medina C, et al. Inhibiting Inflammation With Myeloid Cell-Specific Nanobiologics Promotes Organ Transplant Acceptance. Immunity (2018) 49(5):819–28 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.008

46. Bekkering S, Quintin J, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Riksen NP. Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Induces Long-Term Proinflammatory Cytokine Production and Foam Cell Formation via Epigenetic Reprogramming of Monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol (2014) 34(8):1731–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303887

47. Van Der Valk FM, Bekkering S, Kroon J, Yeang C, Van Den Bossche J, Van Buul JD, et al. Oxidized Phospholipids on Lipoprotein(a) Elicit Arterial Wall Inflammation and an Inflammatory Monocyte Response in Humans. Circulation (2016) 134:611–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.020838

48. Schnack L, Sohrabi Y, Lagache SMM, Kahles F, Bruemmer D, Waltenberger J, et al. Mechanisms of Trained Innate Immunity in Oxldl Primed Human Coronary Smooth Muscle Cells. Front Immunol (2019) 10:13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00013

49. Sohrabi Y, Lagache SMM, Voges VC, Semo D, Sonntag G, Hanemann I, et al. Oxldl-Mediated Immunologic Memory in Endothelial Cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol (2020) 146:121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.07.006

50. Janeway CA Jr., Medzhitov R. Innate Immune Recognition. Annu Rev Immunol (2002) 20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359

51. Kono H, Rock K. How Dying Cells Alert the Immune System to Danger. Nat Rev Immunol (2008) 8(4):279–89. doi: 10.1038/nri2215

52. Chen GY, Tang J, Zheng P, Liu Y. CD24 and Siglec-10 Selectively Repress Tissue Damage–Induced Immune Responses. Science (2009) 323(5922):1722–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1168988

53. Yang D, Han Z, Oppenheim JJ. Alarmins and Immunity. Immunol Rev (2017) 280(1):41–56. doi: 10.1111/imr.12577

54. Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern Recognition Receptors and Inflammation. Cell (2010) 140(6):805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022

55. Seeley JJ, Ghosh S. Molecular Mechanisms of Innate Memory and Tolerance to LPS. J Leukoc Biol (2017) 101(1):107–19. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3MR0316-118RR

56. Tan Y, Zanoni I, Cullen TW, Goodman AL, Kagan JC. Mechanisms of Toll-Like Receptor 4 Endocytosis Reveal a Common Immune-Evasion Strategy Used by Pathogenic and Commensal Bacteria. Immunity (2015) 43(5):909–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.008

57. Soares MP, Gozzelino R, Weis S. Tissue Damage Control in Disease Tolerance. Trends Immunol (2014) 35(10):483–94. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.08.001

58. Crisan TO, Netea MG, Joosten LA. Innate Immune Memory: Implications for Host Responses to Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns. Eur J Immunol (2016) 46(4):817–28. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545497

59. van der Heijden C, Keating ST, Groh L, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, Riksen NP. Aldosterone Induces Trained Immunity: The Role of Fatty Acid Synthesis. Cardiovasc Res (2020) 116(2):317–28. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz137

60. Miller YI, Viriyakosol S, Worrall DS, Boullier A, Butler S, Witztum JL. Toll-Like Receptor 4-Dependent and -Independent Cytokine Secretion Induced by Minimally Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein in Macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol (2005) 25(6):1213–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000159891.73193.31

61. Chavez-Sanchez L, Madrid-Miller A, Chavez-Rueda K, Legorreta-Haquet MV, Tesoro-Cruz E, Blanco-Favela F. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by Minimally Modified Low-Density Lipoprotein in Human Macrophages and Monocytes Triggers the Inflammatory Response. Hum Immunol (2010) 71(8):737–44. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.05.005

62. Mineo C. Lipoprotein Receptor Signalling in Atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res (2020) 116(7):1254–74. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz338

63. Aft RL, Mueller GC. Hemin-Mediated DNA Strand Scission. J Biol Chem (1983) 258(19):12069–72. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)44341-9

64. Aft RL, Mueller GC. Hemin-Mediated Oxidative Degradation of Proteins. J Biol Chem (1984) 259(1):301–5. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)43657-X

65. Kristiansen M, Graversen JH, Jacobsen C, Sonne O, Hoffman HJ, Law SK, et al. Identification of the Haemoglobin Scavenger Receptor. Nature (2001) 409(6817):198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594

66. Melamed-Frank M, Lache O, Enav BI, Szafranek T, Levy NS, Ricklis RM, et al. Structure-Function Analysis of the Antioxidant Properties of Haptoglobin. Blood (2001) 98(13):3693–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.13.3693

67. Philippidis P, Mason JC, Evans BJ, Nadra I, Taylor KM, Haskard DO, et al. Hemoglobin Scavenger Receptor CD163 Mediates Interleukin-10 Release and Heme Oxygenase-1 Synthesis: Antiinflammatory Monocyte-Macrophage Responses In Vitro, in Resolving Skin Blisters In Vivo, and After Cardiopulmonary Bypass Surgery. Circ Res (2004) 94(1):119–26. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109414.78907.F9

68. Paoli M, Anderson BF, Baker HM, Morgan WT, Smith A, Baker EN. Crystal Structure of Hemopexin Reveals a Novel High-Affinity Heme Site Formed Between Two Beta-Propeller Domains. Nat Struct Biol (1999) 6(10):926–31. doi: 10.1038/13294

69. Hvidberg V, Maniecki MB, Jacobsen C, Hojrup P, Moller HJ, Moestrup SK. Identification of the Receptor Scavenging Hemopexin-Heme Complexes. Blood (2005) 106(7):2572–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1185

70. Englert FA, Seidel RA, Galler K, Gouveia Z, Soares MP, Neugebauer U, et al. Labile Heme Impairs Hepatic Microcirculation and Promotes Hepatic Injury. Arch Biochem Biophys (2019) 672:108075. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2019.108075

71. Gouveia Z, Carlos AR, Yuan X, Aires-da-Silva F, Stocker R, Maghzal GJ, et al. Characterization of Plasma Labile Heme in Hemolytic Conditions. FEBS J (2017) 284(19):3278–301. doi: 10.1111/febs.14192

72. Ferreira A, Balla J, Jeney V, Balla G, Soares MP. A Central Role for Free Heme in the Pathogenesis of Severe Malaria: The Missing Link? J Mol Med (2008) 86(10):1097–111. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0368-5

73. Larsen R, Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Tokaji L, Bozza FA, Japiassu AM, et al. A Central Role for Free Heme in the Pathogenesis of Severe Sepsis. Sci Transl Med (2010) 2(51):51ra71. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001118

74. Soares MP, Bozza MT. Red Alert: Labile Heme is an Alarmin. Curr Opin Immunol (2015) 38:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.11.006

75. Weis S, Carlos AR, Moita MR, Singh S, Blankenhaus B, Cardoso S, et al. Metabolic Adaptation Establishes Disease Tolerance to Sepsis. Cell (2017) 169(7):1263–75 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.031

76. Dutra FF, Bozza MT. Heme on Innate Immunity and Inflammation. Front Pharmacol (2014) 5:115. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00115

77. Bozza MT, Jeney V. Pro-Inflammatory Actions of Heme and Other Hemoglobin-Derived Damps. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1323. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01323

78. Fernandez PL, Dutra FF, Alves L, Figueiredo RT, Mourao-Sa D, Fortes GB, et al. Heme Amplifies the Innate Immune Response to Microbial Molecules Through Spleen Tyrosine Kinase (Syk)-Dependent Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. J Biol Chem (2010) 285(43):32844–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146076

79. Gekas C, Graf T. CD41 Expression Marks Myeloid-Biased Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Increases With Age. Blood (2013) 121(22):4463–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457929

80. Schrum JE, Crabtree JN, Dobbs KR, Kiritsy MC, Reed GW, Gazzinelli RT, et al. Cutting Edge: Plasmodium Falciparum Induces Trained Innate Immunity. J Immunol (2018) 200(4):1243–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701010

81. Cowman AF, Crabb BS. Invasion of Red Blood Cells by Malaria Parasites. Cell (2006) 124(4):755–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.006

82. Sigala PA, Goldberg DE. The Peculiarities and Paradoxes of Plasmodium Heme Metabolism. Annu Rev Microbiol (2014) 68:259–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091313-103537

83. Levitan I, Volkov S, Subbaiah PV. Oxidized LDL: Diversity, Patterns of Recognition, and Pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal (2010) 13(1):39–75. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2733

84. Poznyak AV, Nikiforov NG, Markin AM, Kashirskikh DA, Myasoedova VA, Gerasimova EV, et al. Overview of Oxldl and Its Impact on Cardiovascular Health: Focus on Atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol (2020) 11:613780. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.613780

85. Stewart CR, Stuart LM, Wilkinson K, van Gils JM, Deng J, Halle A, et al. CD36 Ligands Promote Sterile Inflammation Through Assembly of a Toll-Like Receptor 4 and 6 Heterodimer. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(2):155–61. doi: 10.1038/ni.1836

86. Keating ST, Groh L, Thiem K, Bekkering S, Li Y, Matzaraki V, et al. Rewiring of Glucose Metabolism Defines Trained Immunity Induced by Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein. J Mol Med (Berl) (2020) 98(6):819–31. doi: 10.1007/s00109-020-01915-w

87. Christ A, Gunther P, Lauterbach MAR, Duewell P, Biswas D, Pelka K, et al. Western Diet Triggers Nlrp3-Dependent Innate Immune Reprogramming. Cell (2018) 172(1-2):162–75 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.013

88. Haversen L, Sundelin JP, Mardinoglu A, Rutberg M, Stahlman M, Wilhelmsson U, et al. Vimentin Deficiency in Macrophages Induces Increased Oxidative Stress and Vascular Inflammation But Attenuates Atherosclerosis in Mice. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):16973. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34659-2

89. Yang H, Wang H, Andersson U. Targeting Inflammation Driven by HMGB1. Front Immunol (2020) 11:484. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00484

90. Valdes-Ferrer SI, Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Lu B, Dancho ME, Li J, et al. High-Mobility Group Box 1 Mediates Persistent Splenocyte Priming in Sepsis Survivors: Evidence From a Murine Model. Shock (2013) 40(6):492–5. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000050

91. Venereau E, Ceriotti C, Bianchi ME. Damps From Cell Death to New Life. Front Immunol (2015) 6:422. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00422

Keywords: DAMP, trained innate immunity, heme, vimentin, oxLDL

Citation: Jentho E and Weis S (2021) DAMPs and Innate Immune Training. Front. Immunol. 12:699563. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.699563

Received: 23 April 2021; Accepted: 09 September 2021;

Published: 22 October 2021.

Edited by:

James Hewitson, University of York, United KingdomReviewed by:

Dipankar Nandi, Indian Institute of Science (IISc), IndiaCopyright © 2021 Jentho and Weis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elisa Jentho, ZWplbnRob0BpZ2MuZ3VsYmVua2lhbi5wdA==; Sebastian Weis, U2ViYXN0aWFuLldlaXNAbWVkLnVuaS1qZW5hLmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.