- 1Respiratory Medicine Division, Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Federico II University, Naples, Italy

- 2Hematology−Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation Unit, Department of Hematology and Developmental Therapeutics, Istituto Nazionale Tumori-IRCCS-Fondazione G. Pascale, Naples, Italy

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most devastating progressive interstitial lung disease that remains refractory to treatment. Pathogenesis of IPF relies on the aberrant cross-talk between injured alveolar cells and myofibroblasts, which ultimately leads to an aberrant fibrous reaction. The contribution of the immune system to IPF remains not fully explored. Recent evidence suggests that both innate and adaptive immune responses may participate in the fibrotic process. Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent professional antigen-presenting cells that bridge innate and adaptive immunity. Also, they exert a crucial role in the immune surveillance of the lung, where they are strategically placed in the airway epithelium and interstitium. Immature DCs accumulate in the IPF lung close to areas of epithelial hyperplasia and fibrosis. Conversely, mature DCs are concentrated in well-organized lymphoid follicles along with T and B cells and bronchoalveolar lavage of IPF patients. We have recently shown that all sub-types of peripheral blood DCs (including conventional and plasmacytoid DCs) are severely depleted in therapy naïve IPF patients. Also, the low frequency of conventional CD1c+ DCs is predictive of a worse prognosis. The purpose of this mini-review is to focus on the main evidence on DC involvement in IPF pathogenesis. Unanswered questions and opportunities for future research ranging from a better understanding of their contribution to diagnosis and prognosis to personalized DC-based therapies will be explored.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive and devastating fatal lung disease that usually remains refractory to treatment (1–3), with an estimated median survival of 2 to 5 years from the first diagnosis. In the last two decades, disease incidence has steadily increased, varying from 2.8 to 19 cases per 100 .000 people per year in Europe and North America, respectively (1). Disease behavior is also highly variable, with associated comorbidities potentially exerting a detrimental impact on prognosis (4, 5). The current availability of anti-fibrotic drugs (i.e., nintedanib and pirfenidone) has improved patients’ short-term life expectancy through the slowdown of the lung function decline and the reduction of hospitalization rate and episodes of acute exacerbation (6). Despite many efforts, the pathogenesis of IPF has not yet been elucidated. No longer considered just an inflammatory disorder (7), IPF pathogenesis likely relies on the aberrant cross-talk between injured alveolar cells and myofibroblasts. This interaction ultimately promotes a pro-fibrotic microenvironment through the engagement of a vicious circle supported, among others, by oxidative stress (8–10). The immune system’s contribution to IPF remains poorly understood, with several pieces of emerging evidence suggesting that both innate and adaptive responses can orchestrate the fibrotic process (11–13). In this scenario, dendritic cells (DCs) may play a significant role because of their involvement in the lungs’ immune surveillance, where they are strategically placed within the airway epithelium and interstitium (14).

Notably, DCs encompass a heterogeneous family of bone marrow-derived cells recognized as the most specialized and potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the immune system (15, 16). DCs are located in almost all tissues, where they detect and process Ags for presentation to T lymphocytes, thus establishing a tailored link between innate and adaptive immune responses. Besides, DCs are pivotal in regulating the delicate interplay between immunity and tolerance (17–19) as they promote the deletion of clonal autoreactive immature T cells in the thymus. Conversely, DCs interact in the periphery with T cells to achieve immune tolerance by inducing T-cell anergy, T cell deletion, and amplification and stimulation of regulatory T cell (Treg) subsets (18, 19). Due to their pleiotropic functions and properties within the immune system, DCs have been broadly studied in different experimental and internal medicine areas, including transplantation, allergy, autoimmunity, infectious diseases, cancer (20), and, more recently, fibrosis. Significant efforts have explored the fibrogenesis of different organs, including the liver, the kidney, and the heart (21–24).

The present review aims to offer an overview including the most relevant contributions in the field of IPF to focus on the emerging evidence addressing the role of DCs in disease pathogenesis and clinical behavior and potentially in immune-targeted therapy development.

Development of Dendritic Cells

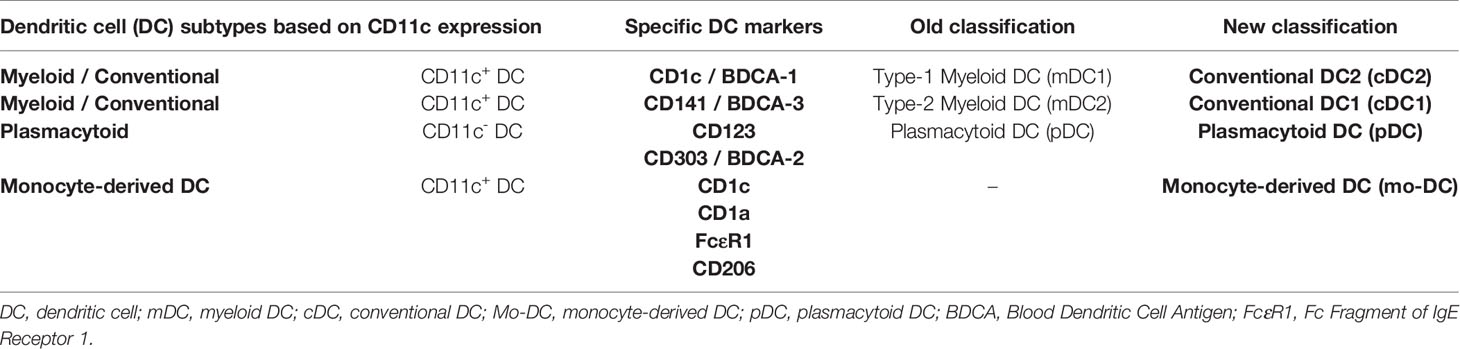

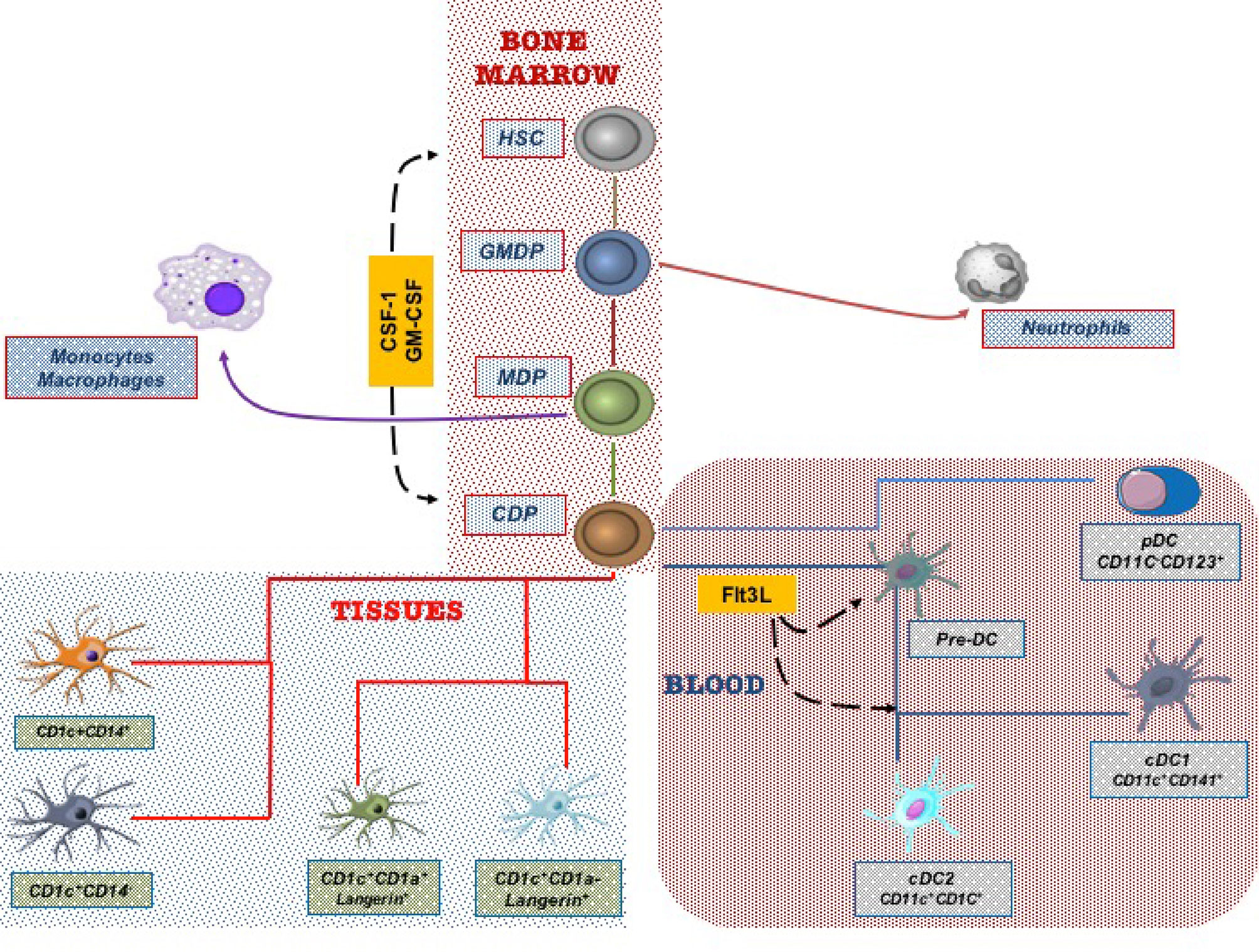

DCs originate from bone marrow progenitors through hematopoiesis, a finely regulated development process that involves several cellular and molecular events. Recent studies have identified a common DC precursor, the human granulocyte-monocyte-DC progenitor (GMDP), which supports the development of all the three major human DC subtypes (25). The GMDPs, through an intermediate maturation state into monocyte-dendritic progenitors (MDPs), differentiate into the common DC progenitors (CDPs). CDPs are restricted to the bone marrow, where they give rise to plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) and conventional DC precursors (pre-cDCs). Frequencies of pre-cDCs increase in response to circulating FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 Ligand (Flt3L) and then terminally differentiate into conventional DC (cDC) subsets in the periphery (25, 26). Accordingly, colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) are major cytokines required for human DC differentiation. In particular, Flt3L is a crucial regulator of DC commitment to both cDCs and pDCs (27–29). Additional transcription factors such as Ikaros, PU.1, growth factor independent 1 transcriptional repressor (GFi1), interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8), basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor 3 (BATF3), and inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (ID2) synergistically regulate DC development and subset specification through the engagement of different signaling pathways (30–35), as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Dendritic cells (DCs) derive from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. Progenitor cells give rise in the final step to Common Derived Progenitors (CDPs) that differentiate in the blood circulating DC subtypes and in lung tissue DC subsets.

Classification and Function of Dendritic Cell Subtypes

In humans, blood DC subtypes include CD11c+cDCs, that are CD1c+ or CD141+ cells, and CD11c- pDCs, including CD123+ or CD303+ cells. Conventional DCs, previously termed type-1 (CD1c+) and type-2 (CD141+) myeloid DCs (mDCs), have recently reclassified as cDC2 and cDC1, respectively (36–38) (Figure 1). Conventional DCs exert a key function ranging from pathogen detection to cancer immunity as they are critical, through antigen presentation, to initiate specific T-cell responses. On the other, pDCs display high anti-viral activities due to their ability to produce type I interferon and are thought to be involved in immune tolerance (39, 40).

Finally, a new DC subtype is represented by the so-called monocyte-derived DCs (mo-DCs). Evidence shows that mo-DCs arise from monocytes recruited to the inflammatory site and express CD11c, CD1c, CD1a, FcϵR1, IRF4, and ZBTB46. It is thought that mo-DCs promote CD4+ T cell polarization within inflammatory contexts (41). A synoptical view of the previous and actual classification of DCs is reported in Table 1.

Dendritic Cell Activation and Functional Maturation

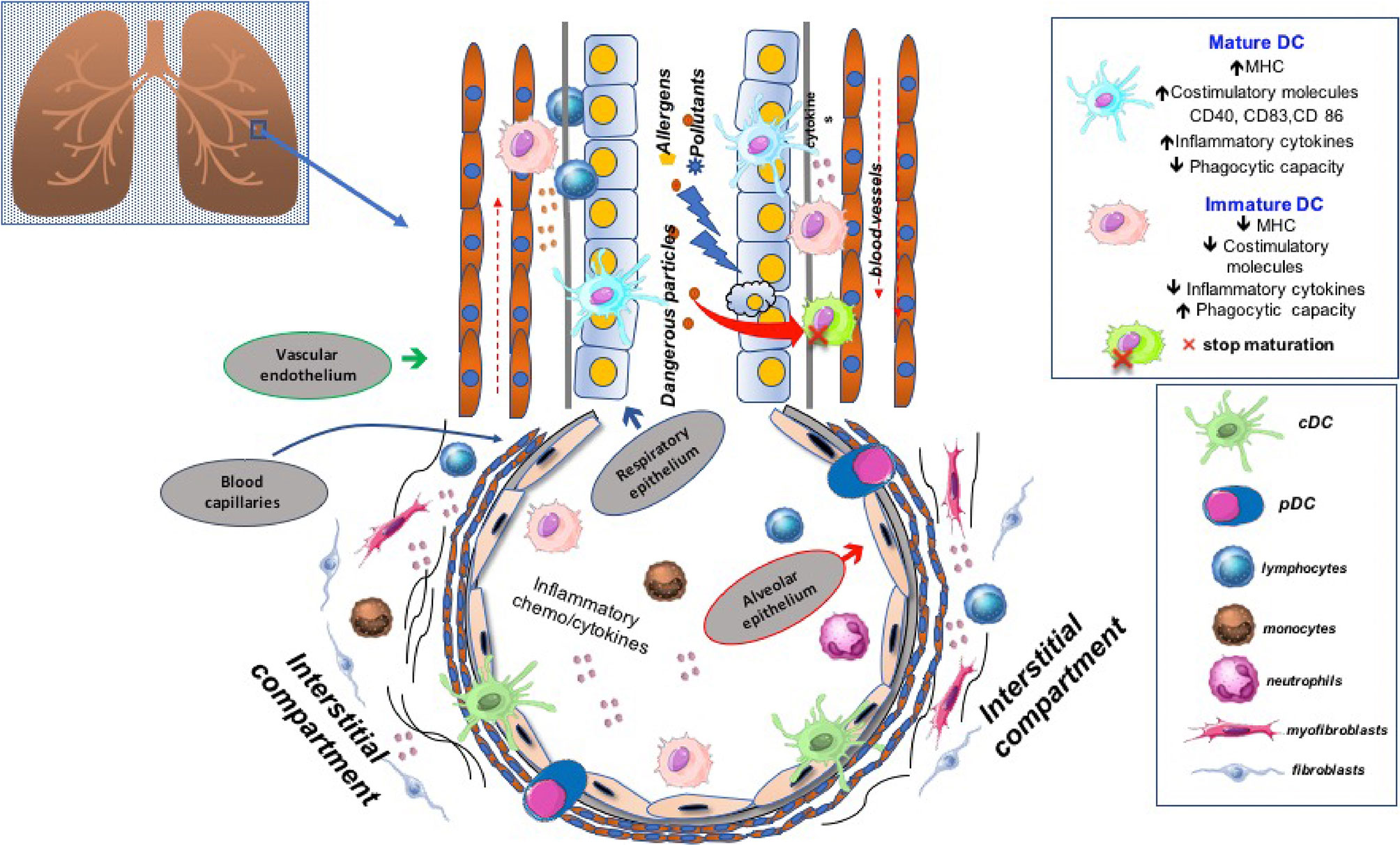

Mature DCs display phenotypic and functional profiles distinct from their naïve (immature) counterparts. Immature DCs express low levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and co-stimulatory molecules and are usually found in peripheral tissues where they play as sentinels for immune monitoring. These cells can endocytose and process antigens but are poorly effective in generating peptide-MHC complexes to ensure optimal antigen presentation and efficient T-cell activation (42–45). Tissue damage, inflammatory processes, microorganisms, and tumor-derived products may promote the maturation of DCs. After that, these cells lose endocytic activity, increase MHC-peptide complexes, up-regulate co-stimulatory molecules, and secrete inflammatory cytokines essential for the activation of T-cell responses (46, 47). Lastly, following maturation, DCs acquire an increased migratory potential that allows them to move into different compartments, such as non-lymphoid and lymphoid tissues and blood (48, 49).

Dendritic Cell Subsets in the Human Lung Microenvironment

Due to their anatomy and function, the lungs are vital organs constantly exposed to the external environment. Consequently, inhaled particles of different nature and origin and potential pathogens need to be efficiently counteracted by a finely adjusted immune response to preserve lung health (50). The activity of lung DCs mainly depends on their organ distribution. For instance, DCs located in the alveolar septa have many dendritic projections able to continuously sample, while those located in the conducting airways seem to do so most rarely (51). Usually, DCs exist in an immature state in the lung periphery, skilled to take up inhaled particulate and soluble antigens. Upon activation, lung DCs, as previously described, become qualified to (52) induce a tailor-made immune response by T-cells (T-helper cell (Th) type 1, Th2, or Th17, depending on the type of pathogen) and B-cells (53, 54).

The lack of validated markers and technical difficulties in obtaining human lung tissues for investigation has significantly limited human lung DC subsets’ characterization and functional studies. Since the first observations by Demetds et al., who initially identified human lung DC subsets through the BDCA markers previously applied to characterize blood DCs (55), understanding pulmonary DC subtypes has improved chiefly only in the last few years. In particular, both genomic and functional studies have shown that human epithelial-associated DCs can be divided into four major subpopulations: pDCs, cDC2 CD1c+, cDC1 CD141+, and mo-DCs (36–38, 41). More recently, lung DCs have been reclassified into five subtypes based on the differential expression of Langerin, CD1c, and CD14 (56). Interestingly, transcriptome analysis performed in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples has revealed in the human lower respiratory tract the existence of Langerin+, CD14+, and CD14− subsets of CD1c DCs functionally related with alveolar macrophages. Noteworthy, the higher mRNA expression levels of several dendritic cell-associated genes, including CD1, FLT3, CX3CR1, and CCR6, have disclosed a specific gene signature of DCs distinct from that of monocytes/macrophages (56). Figure 1 synthetically depicts the DC subtype differentiation in the lung.

The Role of DCs in IPF Pathogenesis

The involvement of DCs in the pathogenesis of IPF is a challenging field of relatively recent interest, with only a few reports available in humans.

In 2006 it was first reported that fully mature DCs expressing CD40, CD83, CD86, and DC-lysosome-associated membrane protein, along with non-proliferating B and T lymphocytes, contribute to the creation of ectopic organized lymphoid structures in the lung of IPF patients (57). Conversely, immature DC subsets seem to heavily infiltrate the IPF lungs, specifically in areas of epithelial hyperplasia and fibrosis, and to be present in the BAL fluid (58–60). It is thought that fibroblastic foci of IPF patients can orchestrate blood immature DC recruitment through chemokines’ expression (CCL19, CXCL12, and CCL21) (58, 61). This effect may maintain a condition of chronic inflammation by maturing DCs in situ within ectopic lymphoid follicles. Two physiologically relevant models showed that both human and mouse lung fibroblasts are critically involved in DC trafficking by secreting chemokines that play a crucial role in fibrosis and inflammation (62). Accordingly, co-cultures of DCs with lung fibroblasts from control subjects and IPF patients further confirmed the in vitro ability of lung fibroblasts to modulate the activation and maturation of DCs. These findings suggest that IPF fibroblasts might sustain chronic inflammation and immune responses by locally maintaining a pool of immature DCs (63). In a clinical trial published in 2015, the DC-specific growth factor Flt3L was found to increase cDC1 and cDC2 cell populations’ precursors in bone marrow biopsies and peripheral blood samples from healthy volunteers (64). Following this finding, Flt3L has further been shown to be up-regulated in the serum and lung tissue of IPF patients, likely contributing to the accumulation of lung DCs during pulmonary fibrogenesis (65).

We previously showed that quantitative reduction of blood DCs was a feature shared by other respiratory diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and obstructive sleep apnea (66–68). We have recently also investigated the distribution of peripheral DCs subtypes in a prospective cohort of therapy naïve IPF patients. All blood DC subsets were severely depleted in the context of a pro-inflammatory milieu characterized by high expression levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and interleukin (IL)-6. In agreement with data previously reported, we likely attributed such a depletion, at least in part, to an increased cell turnover and recruitment at the lung level. Noteworthy, IL-6 levels and perturbations of the cDC2 subset were not influenced by anti-fibrotic therapies but were associated with reduced survival. Of note, low frequencies of cDC2 were an independent predictive biomarker of worse prognosis (69). Figure 2 shows the role of DC subtypes undergoing the maturation process in the fibrotic lung tissue. Certainly, as mentioned, DCs involvement is not exclusive to IPF as it may also affect other respiratory diseases. In this context, it is worthy of note the report by Naessens T et al. The Authors have shown that cDC2 are potent inducers of T follicular helper cells and contribute to tertiary lymphoid tissue formation in the lung of COPD patients (70).

Figure 2 Dendritic cells (DC) are located in the lung interstitium and alveoli, where they act as sentinel cells. Any imbalance of their frequency distribution and functional status may have significant consequences in disease pathogenesis. Emerging evidence suggests that plenty of local factors along with different arrays of chemo-cytokines can modulate DCs maturation in the lung of patients affected by idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, thus affecting their tolerogenic or immunogenic properties.

The Way Forward: Similarities With Cancer Biology and Rationale for Immune-Targeted Therapies

In the light of the above evidence, DCs appear to play a role in the fibrotic process and, more specifically, in IPF pathogenesis. IPF notably shares many similarities with lung cancer, ranging from genetics to clinical behavior (71). It is also estimated that the overall cancer incidence in IPF patients is 29 cases per 1000 persons-years, with lung neoplasms being the most frequent ones (72). DC alterations have been widely studied and characterized in solid and blood malignancies (73). Like the liver fibrosis model leading to tumorigenesis (22), DC imbalance and functional impairment may represent a pathogenic bridge between IPF and cancer. This aspect merits further investigation for its prevention and therapeutic repercussions (13, 69). In this regard, DC-based treatments represent emerging alternatives to conventional chemotherapy in cancer patients (74), while such an approach is conceptually missing in fibrosis-related diseases. The lack of animal models that faithfully reproduce IPF pathogenesis is undoubtedly a significant limit in this setting. Despite this, the bleomycin model of inflammation-driven pulmonary fibrosis has still helped explore different purposes over time. In this regard, it has been shown that the immune-mediator VAG539 was able to attenuate the hallmarks of bleomycin-induced lung injury through the inactivation of DCs, suggesting a crucial role of these cells across the modulation of both inflammation and fibrosis (75). Likewise, infusion of CD11c-diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor (DTR) in bleomycin-treated mice prompted DCs depletion, thus mitigating lung fibrosis (76). Indeed, both studies have some limitations. First, the expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor as the key molecular target of VAG539 is not restricted to DCs (77), and, second, the infusion of DT to CD11c-DTR mice depletes not only DCs but also pulmonary macrophages as CD11c is highly expressed on both cell types (78). Even with the awareness of these limitations, we believe that this area of interest deserves wider attention. Accordingly, recent clinical trials have explored the safety and efficacy of recombinant human Flt3L in healthy volunteers and cancer therapy to trigger DC expansion in humans (79–81). Interestingly, recombinant Flt3L increased the numbers of CD11b+ DCs, reducing lung fibrosis in wild-type (WT) mice exposed to AdTGF-beta1 (65).

IPF remains, for the most part, an unexplored field due to the non-recognition of the trigger cause. Perturbations of the lung microbiome and viral infections have been hypothesized to have a potential link with the development of IPF (82–86). Therefore, it is not negligible that any dysregulation of DCs, as major APCs and anti-viral effectors, may actively contribute to the puzzle of IPF pathogenesis through a wider involvement at different levels. Overall, accumulated evidence and related considerations further strengthen the concept that participation of DCs in the fibrotic process could be a driving force for future deepening.

Conclusion

Interpreting the involvement of the immune response in the pathogenesis of IPF has become a prosperous field of investigation only in recent years. New reports reveal expanding potential pathogenic roles for DCs in lung fibrosis. These findings promise to open new scenarios to understand better the cause and the biological mechanisms underlying the disease. Further efforts and challenges will be to evaluate their potential in terms of easy to perform biomarkers predictive of clinical behavior and targets of immune-based treatments. In analogy with cancer, combination therapy strategies with anti-fibrotic drugs could optimistically represent a milestone shortly.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Hutchinson J, Fogarty A, Hubbard R, McKeever T. Global Incidence and Mortality of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Systematic Review. Eur Respir J (2015) 46(3):795–806. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00185114

2. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2018) 198(5):e44–68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST

3. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-Based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2011) 183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL

4. Kreuter M, Ehlers-Tenenbaum S, Palmowski K, Bruhwyler J, Oltmanns U, Muley T, et al. Impact of Comorbidities on Mortality in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. PloS One (2016) 11(3):e0151425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151425

5. Torrisi SE, Ley B, Kreuter M, Wijsenbeek M, Vittinghoff E, Collard HR, et al. The Added Value of Comorbidities in Predicting Survival in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Multicentre Observational Study. Eur Respir J (2019) 53(3):1–10. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01587-2018

6. Maher TM, Strek ME. Anti-Fibrotic Therapy for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Time to Treat. Respir Res (2019) 20(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1161-4

7. Selman M, Pardo A. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Misunderstandings Between Epithelial Cells and Fibroblasts? Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis (2004) 21(3):165–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2221PP

8. Selman M, Pardo A. Revealing the Pathogenic and Aging-Related Mechanisms of the Enigmatic Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Integral Model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2014) 189(10):1161–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2221PP

9. Hill C, Jones MG, Davies DE, Wang Y. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Contributes to Pulmonary Fibrosis Via Aberrant Epithelial/Fibroblastic Cross-Talk. J Lung Health Dis (2019) 3(2):31–5. doi: 10.29245/2689-999X/2019/2.1149

10. Bocchino M, Agnese S, Fagone E, Svegliati S, Grieco D, Vancheri C, et al. Reactive Oxygen Species are Required for Maintenance and Differentiation of Primary Lung Fibroblasts in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. PloS One (2010) 5(11):e14003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014003

11. Galati D, De Martino M, Trotta A, Rea G, Bruzzese D, Cicchitto G, et al. Peripheral Depletion of NK Cells and Imbalance of the Treg/Th17 Axis in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Patients. Cytokine (2014) 66(2):119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.12.003

12. Desai O, Winkler J, Minasyan M, Herzog EL. The Role of Immune and Inflammatory Cells in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front Med (Lausanne) (2018) 5:43. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00043

13. Shenderov K, Collins SL, Powell JD, Horton MR. Immune Dysregulation as a Driver of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Clin Invest (2021) 131(2):1–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI143226

14. Worbs T, Hammerschmidt SI, Forster R. Dendritic Cell Migration in Health and Disease. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17(1):30–48. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.116

15. Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, et al. Immunobiology of Dendritic Cells. Annu Rev Immunol (2000) 18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767

16. Steinman RM. Decisions About Dendritic Cells: Past, Present, and Future. Annu Rev Immunol (2012) 30:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-100311-102839

17. Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic Cells and the Control of Immunity. Nature (1998) 392(6673):245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588

18. Cools N, Ponsaerts P, Van Tendeloo VF, Berneman ZN. Balancing Between Immunity and Tolerance: An Interplay Between Dendritic Cells, Regulatory T Cells, and Effector T Cells. J Leukoc Biol (2007) 82(6):1365–74. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307166

19. Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking Dendritic Cells Into Medicine. Nature (2007) 449(7161):419–26. doi: 10.1038/nature06175

20. Lipscomb MF, Masten BJ. Dendritic Cells: Immune Regulators in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev (2002) 82(1):97–130. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2001

21. Baskic D, Vukovic V, Popovic S, Jovanovic D, Mitrovic S, Djurdjevic P, et al. Chronic Hepatitis C: Conspectus of Immunological Events in the Course of Fibrosis Evolution. PloS One (2019) 14(7):e0219508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219508

22. Lurje I, Hammerich L, Tacke F. Dendritic Cell and T Cell Cross-Talk in Liver Fibrogenesis and Hepatocarcinogenesis: Implications for Prevention and Therapy of Liver Cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(19):1–25. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197378

23. Rogers NM, Ferenbach DA, Isenberg JS, Thomson AW, Hughes J. Dendritic Cells and Macrophages in the Kidney: A Spectrum of Good and Evil. Nat Rev Nephrol (2014) 10(11):625–43. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.170

24. Wang H, Kwak D, Fassett J, Liu X, Yao W, Weng X, et al. Role of Bone Marrow-Derived CD11c(+) Dendritic Cells in Systolic Overload-Induced Left Ventricular Inflammation, Fibrosis and Hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol (2017) 112(3):25. doi: 10.1007/s00395-017-0615-4

25. Lee J, Breton G, Oliveira TY, Zhou YJ, Aljoufi A, Puhr S, et al. Restricted Dendritic Cell and Monocyte Progenitors in Human Cord Blood and Bone Marrow. J Exp Med (2015) 212(3):385–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141442

26. Breton G, Zheng S, Valieris R, Tojal da Silva I, Satija R, Nussenzweig MC. Human Dendritic Cells (Dcs) are Derived From Distinct Circulating Precursors That are Precommitted to Become CD1c+ or CD141+ Dcs. J Exp Med (2016) 213(13):2861–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161135

27. Maraskovsky E, Daro E, Roux E, Teepe M, Maliszewski CR, Hoek J, et al. In Vivo Generation of Human Dendritic Cell Subsets by Flt3 Ligand. Blood (2000) 96(3):878–84. doi: 10.1182/blood.V96.3.878.015k15_878_884

28. Marroquin CE, Westwood JA, Lapointe R, Mixon A, Wunderlich JR, Caron D, et al. Mobilization of Dendritic Cell Precursors in Patients With Cancer by Flt3 Ligand Allows the Generation of Higher Yields of Cultured Dendritic Cells. J Immunother (2002) 25(3):278–88. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200205000-00011

29. Anandasabapathy N, Feder R, Mollah S, Tse SW, Longhi MP, Mehandru S, et al. Classical Flt3L-Dependent Dendritic Cells Control Immunity to Protein Vaccine. J Exp Med (2014) 211(9):1875–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131397

30. Hambleton S, Salem S, Bustamante J, Bigley V, Boisson-Dupuis S, Azevedo J, et al. IRF8 Mutations and Human Dendritic-Cell Immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med (2011) 365(2):127–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100066

31. Anderson KL, Perkin H, Surh CD, Venturini S, Maki RA, Torbett BE. Transcription Factor PU.1 is Necessary for Development of Thymic and Myeloid Progenitor-Derived Dendritic Cells. J Immunol (2000) 164(4):1855–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1855

32. Wu L, Nichogiannopoulou A, Shortman K, Georgopoulos K. Cell-Autonomous Defects in Dendritic Cell Populations of Ikaros Mutant Mice Point to a Developmental Relationship With the Lymphoid Lineage. Immunity (1997) 7(4):483–92. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80370-2

33. Rathinam C, Geffers R, Yucel R, Buer J, Welte K, Moroy T, et al. The Transcriptional Repressor Gfi1 Controls STAT3-Dependent Dendritic Cell Development and Function. Immunity (2005) 22(6):717–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.007

34. Poulin LF, Reyal Y, Uronen-Hansson H, Schraml BU, Sancho D, Murphy KM, et al. DNGR-1 is a Specific and Universal Marker of Mouse and Human Batf3-Dependent Dendritic Cells in Lymphoid and non-Lymphoid Tissues. Blood (2012) 119(25):6052–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-406967

35. Spits H, Couwenberg F, Bakker AQ, Weijer K, Uittenbogaart CH. Id2 and Id3 Inhibit Development of CD34(+) Stem Cells Into Predendritic Cell (Pre-DC)2 But Not Into Pre-DC1. Evidence for a Lymphoid Origin of Pre-DC2. J Exp Med (2000) 192(12):1775–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1775

36. Villani AC, Satija R, Reynolds G, Sarkizova S, Shekhar K, Fletcher J, et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals New Types of Human Blood Dendritic Cells, Monocytes, and Progenitors. Science (2017) 356(6335):1–12. doi: 10.1126/science.aah4573

37. Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, et al. Nomenclature of Monocytes and Dendritic Cells in Blood. Blood (2010) 116(16):e74–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558

38. Mildner A, Jung S. Development and Function of Dendritic Cell Subsets. Immunity (2014) 40(5):642–56. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.016

39. Dai H, Thomson AW, Rogers NM. Dendritic Cells as Sensors, Mediators, and Regulators of Ischemic Injury. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2418. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02418

40. Haniffa M, Collin M, Ginhoux F. Ontogeny and Functional Specialization of Dendritic Cells in Human and Mouse. Adv Immunol (2013) 120:1–49. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00001-6

41. Collin M, Bigley V. Human Dendritic Cell Subsets: An Update. Immunology (2018) 154(1):3–20. doi: 10.1111/imm.12888

42. Lutz MB, Schuler G. Immature, Semi-Mature and Fully Mature Dendritic Cells: Which Signals Induce Tolerance or Immunity? Trends Immunol (2002) 23(9):445–9. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02281-0

43. Dudek AM, Martin S, Garg AD, Agostinis P. Immature, Semi-Mature, and Fully Mature Dendritic Cells: Toward a DC-Cancer Cells Interface That Augments Anticancer Immunity. Front Immunol (2013) 4:438. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00438

44. Mahnke K, Schmitt E, Bonifaz L, Enk AH, Jonuleit H. Immature, But Not Inactive: The Tolerogenic Function of Immature Dendritic Cells. Immunol Cell Biol (2002) 80(5):477–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01115.x

45. Manicassamy S, Pulendran B. Dendritic Cell Control of Tolerogenic Responses. Immunol Rev (2011) 241(1):206–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01015.x

46. Mellman I. Dendritic Cells: Master Regulators of the Immune Response. Cancer Immunol Res (2013) 1(3):145–9. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0102

47. Reis e Sousa C. Dendritic Cells in a Mature Age. Nat Rev Immunol (2006) 6(6):476–83. doi: 10.1038/nri1845

48. Bertho N, Adamski H, Toujas L, Debove M, Davoust J, Quillien V. Efficient Migration of Dendritic Cells Toward Lymph Node Chemokines and Induction of T(H)1 Responses Require Maturation Stimulus and Apoptotic Cell Interaction. Blood (2005) 106(5):1734–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3991

49. Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, et al. CCR7 Governs Skin Dendritic Cell Migration Under Inflammatory and Steady-State Conditions. Immunity (2004) 21(2):279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014

50. Schlitzer A, McGovern N, Ginhoux F. Dendritic Cells and Monocyte-Derived Cells: Two Complementary and Integrated Functional Systems. Semin Cell Dev Biol (2015) 41:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.03.011

51. Kopf M, Schneider C, Nobs SP. The Development and Function of Lung-Resident Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Nat Immunol (2015) 16(1):36–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.3052

52. Condon TV, Sawyer RT, Fenton MJ, Riches DW. Lung Dendritic Cells At the Innate-Adaptive Immune Interface. J Leukoc Biol (2011) 90(5):883–95. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311134

53. Lambrecht BN, Prins JB, Hoogsteden HC. Lung Dendritic Cells and Host Immunity to Infection. Eur Respir J (2001) 18(4):692–704.

54. Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Lung Dendritic Cells: Targets for Therapy in Allergic Disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol (2009) 188):99–114. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71029-5_5

55. Demedts IK, Brusselle GG, Vermaelen KY, Pauwels RA. Identification and Characterization of Human Pulmonary Dendritic Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2005) 32(3):177–84. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0279OC

56. Patel VI, Booth JL, Duggan ES, Cate S, White VL, Hutchings D, et al. Transcriptional Classification and Functional Characterization of Human Airway Macrophage and Dendritic Cell Subsets. J Immunol (2017) 198(3):1183–201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600777

57. Marchal-Somme J, Uzunhan Y, Marchand-Adam S, Valeyre D, Soumelis V, Crestani B, et al. Cutting Edge: non-Proliferating Mature Immune Cells Form a Novel Type of Organized Lymphoid Structure in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Immunol (2006) 176(10):5735–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5735

58. Marchal-Somme J, Uzunhan Y, Marchand-Adam S, Kambouchner M, Valeyre D, Crestani B, et al. Dendritic Cells Accumulate in Human Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2007) 176(10):1007–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200609-1347OC

59. Greer AM, Matthay MA, Kukreja J, Bhakta NR, Nguyen CP, Wolters PJ, et al. Accumulation of BDCA1(+) Dendritic Cells in Interstitial Fibrotic Lung Diseases and Th2-High Asthma. PloS One (2014) 9(6):e99084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099084

60. Tsoumakidou M, Karagiannis KP, Bouloukaki I, Zakynthinos S, Tzanakis N, Siafakas NM. Increased Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid CD1c Expressing Dendritic Cells in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Respiration (2009) 78(4):446–52. doi: 10.1159/000226244

61. Luther SA, Bidgol A, Hargreaves DC, Schmidt A, Xu Y, Paniyadi J, et al. Differing Activities of Homeostatic Chemokines CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 in Lymphocyte and Dendritic Cell Recruitment and Lymphoid Neogenesis. J Immunol (2002) 169(1):424–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.424

62. Kitamura H, Cambier S, Somanath S, Barker T, Minagawa S, Markovics J, et al. Mouse and Human Lung Fibroblasts Regulate Dendritic Cell Trafficking, Airway Inflammation, and Fibrosis Through Integrin Alphavbeta8-Mediated Activation of TGF-Beta. J Clin Invest (2011) 121(7):2863–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI45589

63. Freynet O, Marchal-Somme J, Jean-Louis F, Mailleux A, Crestani B, Soler P, et al. Human Lung Fibroblasts may Modulate Dendritic Cell Phenotype and Function: Results From a Pilot in Vitro Study. Respir Res (2016) 17:36. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0345-4

64. Breton G, Lee J, Zhou YJ, Schreiber JJ, Keler T, Puhr S, et al. Circulating Precursors of Human CD1c+ and CD141+ Dendritic Cells. J Exp Med (2015) 212(3):401–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141441

65. Tort Tarres M, Aschenbrenner F, Maus R, Stolper J, Schuette L, Knudsen L, et al. The FMS-Like Tyrosine Kinase-3 Ligand/Lung Dendritic Cell Axis Contributes to Regulation of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Thorax (2019) 74:947–57. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212603

66. Galati D, Zanotta S, Corazzelli G, Bruzzese D, Capobianco G, Morelli E, et al. Circulating Dendritic Cells Deficiencies as a New Biomarker in Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma. Br J Haematol (2019) 184(4):594–604. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15676

67. Galgani M, Fabozzi I, Perna F, Bruzzese D, Bellofiore B, Calabrese C, et al. Imbalance of Circulating Dendritic Cell Subsets in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Clin Immunol (2010) 137(1):102–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.010

68. Galati D, Zanotta S, Canora A, Polistina GE, Nicoletta C, Ghinassi G, et al. Severe Depletion of Peripheral Blood Dendritic Cell Subsets in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients: A New Link With Cancer? Cytokine (2020) 125:154831. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154831

69. Galati D, Zanotta S, Polistina GE, Coppola A, Capitelli L, Bocchino M. Circulating Dendritic Cells are Severely Decreased in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis With a Potential Value for Prognosis Prediction. Clin Immunol (2020) 215:108454. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108454

70. Naessens T, Morias Y, Hamrud E, Gehrmann U, Budida R, Mattsson J, et al. Human Lung Conventional Dendritic Cells Orchestrate Lymphoid Neogenesis During Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2020) 202(4):535–48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1123OC

71. Tzouvelekis A, Gomatou G, Bouros E, Trigidou R, Tzilas V, Bouros D. Common Pathogenic Mechanisms Between Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer. Chest (2019) 156(2):383–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.04.114

72. Lee HY, Lee J, Lee CH, Han K, Choi SM. Risk of Cancer Incidence in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Respirology (2021) 26(2):180–7. doi: 10.1111/resp.13911

73. Galati D, Corazzelli G, De Filippi R, Pinto A. Dendritic Cells in Hematological Malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2016) 108:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.10.006

74. Galati D, Zanotta S, Bocchino M, De Filippi R, Pinto A. The Subtle Interplay Between Gamma Delta T Lymphocytes and Dendritic Cells: Is There a Role for a Therapeutic Cancer Vaccine in the Era of Combinatorial Strategies? Cancer Immunol Immunother (2021). doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02805-3

75. Bantsimba-Malanda C, Marchal-Somme J, Goven D, Freynet O, Michel L, Crestani B, et al. A Role for Dendritic Cells in Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice? Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2010) 182(3):385–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1164OC

76. Ding L, Liu T, Wu Z, Hu B, Nakashima T, Ullenbruch M, et al. Bone Marrow Cd11c+ Cell-Derived Amphiregulin Promotes Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Immunol (2016) 197(1):303–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502479

77. Mulero-Navarro S, Fernandez-Salguero PM. New Trends in Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Biology. Front Cell Dev Biol (2016) 4:45. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00045

78. van Rijt LS, Jung S, Kleinjan A, Vos N, Willart M, Duez C, et al. In Vivo Depletion of Lung CD11c+ Dendritic Cells During Allergen Challenge Abrogates the Characteristic Features of Asthma. J Exp Med (2005) 201(6):981–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042311

79. Galati D, Zanotta S. Empowering Dendritic Cell Cancer Vaccination: The Role of Combinatorial Strategies. Cytotherapy (2018) 20(11):1309–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.09.007

80. Anandasabapathy N, Breton G, Hurley A, Caskey M, Trumpfheller C, Sarma P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of CDX-301, Recombinant Human Flt3L, At Expanding Dendritic Cells and Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Healthy Human Volunteers. Bone Marrow Transplant (2015) 50(7):924–30. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.74

81. Galati D, Zanotta S. Hematologic Neoplasms: Dendritic Cells Vaccines in Motion. Clin Immunol (2017) 183:181–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.08.016

82. Lipinski JH, Moore BB, O’Dwyer DN. The Evolving Role of the Lung Microbiome in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2020) 319(4):L675–L82. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00258.2020

83. Invernizzi R, Molyneaux PL. The Contribution of Infection and the Respiratory Microbiome in Acute Exacerbations of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev (2019) 28(152):1–6. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0045-2019

84. Tong X, Su F, Xu X, Xu H, Yang T, Xu Q, et al. Alterations to the Lung Microbiome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2019) 9:149. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00149

85. Sheng G, Chen P, Wei Y, Yue H, Chu J, Zhao J, et al. Viral Infection Increases the Risk of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Meta-Analysis. Chest (2020) 157(5):1175–87. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.10.032

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, dendritic cells, immunity, cancer, immunotherapy

Citation: Bocchino M, Zanotta S, Capitelli L and Galati D (2021) Dendritic Cells Are the Intriguing Players in the Puzzle of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Pathogenesis. Front. Immunol. 12:664109. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.664109

Received: 04 February 2021; Accepted: 15 April 2021;

Published: 30 April 2021.

Edited by:

Mats Bemark, University of Gothenburg, SwedenReviewed by:

Harry D. Dawson, Agricultural Research Service (USDA), United StatesUlrich Maus, Hannover Medical School, Germany

Copyright © 2021 Bocchino, Zanotta, Capitelli and Galati. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marialuisa Bocchino, bWFyaWFsdWlzYS5ib2NjaGlub0B1bmluYS5pdA==

Marialuisa Bocchino

Marialuisa Bocchino Serena Zanotta2

Serena Zanotta2