- Hubei Key Laboratory of Cell Homeostasis, Frontier Science Center for Immunology and Metabolism, State Key Laboratory of Virology, College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) is a member of the MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK) family and has been implicated in the regulation of a wide range of physiological and pathological processes. TAK1 functions through assembling with its binding partners TAK1-binding proteins (TAB1, TAB2, and TAB3) and can be activated by a variety of stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and toll-like receptor ligands, and they play essential roles in the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs. Numerous studies have demonstrated that post-translational modifications play important roles in properly controlling the activity, stability, and assembly of TAK1-TABs complex according to the indicated cellular environment. This review focuses on the recent advances in TAK1-TABs-mediated signaling and the regulations of TAK1-TABs complex by post-translational modifications.

Introduction

The transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) plays central roles in a variety of cellular events, such as immune and inflammatory responses, cell proliferation, autophagy, tissue remodeling, and metabolic regulation (1–4). In resting cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm where it is associated with inhibitory proteins known as IκBs (5–7). In response to various stimuli, including proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and the viral or bacterial infections, the IκB proteins are rapidly phosphorylated by upstream IκB kinases (IKKs) (8, 9). These kinases, consisting of catalytic subunits IKKα, IKKβ, and NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO), phosphorylate serine 32 (Ser32) and Ser36 of IκBα, which leads to the polyubiquitination of IκBα by SCF-βTrCP E3 ligase (SKP1-CUL1-F-box ligase containing the F-box protein βTrCP) and subsequent degradation through 26S proteasome (10–12). NF-κB is then liberated and translocated to the nucleus, thereby initiating the transcription of specific target genes (6, 12–14).

Transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), a serine/theronine kinase, was first identified as a member of the MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK) family and was originally found to be a mediator of signal transduction in response to TGF-β or bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP-4) (15, 16). Over the years, it has been proved that TAK1 is activated by dozens of stimuli and then phosphorylates a series of target proteins, which elicits different signal transduction and cellular responses across different stresses or cell types (17). Genetic experiments have shown that the Drosophila dTAK1 functions downstream of the Imd protein and upstream of IKK complex in the Imd pathway, and activates JNK and NF-κB after immune stimulation (18, 19). It has been well characterized that TAK1 is essential for TNF receptor (TNFR)-, IL-1 receptor I (IL-1RI)-, and Toll like receptors (TLRs)-mediated activation of NF-κB and MAPKs (8, 12, 20, 21). In addition, TAK1 plays critical roles in adaptive immunity by mediating T cell and B cell receptor signaling (22–25). In all of these pathways, TAK1 is considered as a key regulator of activation of NF-κB and MAPKs, and it plays vital roles in transmitting the upstream signal from the indicated receptor complex to the downstream signalosomes (23, 26–28).

Conventional ablation of TAK1 results in embryonic lethality because of bone marrow and liver failure in mice (29–31). TAK1-deficiency in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) severely impairs TNFR1-, IL-1R-, and TLRs-mediated activation of NF-κB and MAPKs (20). However, TLR4-mediated activation of NF-κB, p38, and JNK, and the production of proinflammatory cytokines are increased in TAK1-deficient neutrophils, suggesting a cell type-specific role for TAK1 in TLR signaling (32).

TAK1 activation requires TAK1-binding protein 1 (TAB1), TAB2, and TAB3. TAB1 is an adaptor protein constitutively associated with N-terminal kinase domain of TAK1 even in the unstimulated cells, while TAB2 and TAB3 bind to the C-terminus of TAK1 through TAK1-binding domain after stimulation (33–36). Although the excessive production of TAB1 increases the kinase activity of TAK1 and acts as an activator of NF-κB signaling in vitro, TAB1-dificiency has minor effects on TNFα- and IL-1β-triggered activation of NF-κB and the induction of downstream inflammatory cytokines (20, 33, 37, 38). Interestingly, TAB1-deficiency dramatically impairs phosphorylation of TAK1 at theronine 187 (Thr187) after TNFα and IL-1β stimulations (39). In contrast, several studies proved that TAB2 and its homolog TAB3 play redundant roles in TAK1 activation (40, 41). Unlike TAB1, TAB2 and TAB3 do not activate TAK1 in vitro. Double deficiency of TAB2 and TAB3 has minor effects on TAK1 activation and production of downstream inflammatory cytokines at the early phase after IL-1β stimulation. But in late phase, IL-1β-triggered TAK1 activation and transcription of downstream genes were markedly declined in TAB2- and TAB3-double deficient cells, suggesting that TAB2 and TAB3 are not required in the early TAK1 activation but are essential for sustained TAK1 activation (20, 37, 40, 42).

The TAK1-TABs complex phosphorylates IKKβ at Ser177 and Ser181, which is required for the activation of NF-κB signaling (43–46). In addition, TAK1-TABs complex is also critical for the activation of MAPKs (20, 47). Several reports have demonstrated that the TAK1-TABs complex plays important roles in innate immune and inflammatory responses. It is also emerging that this complex controls a large amount of physiological and pathological processes (21, 48–51). Although the TAK1-TABs complex has been widely studied, the roles of the individual binding proteins and the molecular mechanisms responsible for their activation in different cell types remains to be addressed. In this review, we will summarize the latest advances in the understanding of TAK1-TABs-mediated signaling transduction and the regulation of their activities by post-translational modifications (PTMs).

The TAK1-TABs-Mediated Signaling Pathway

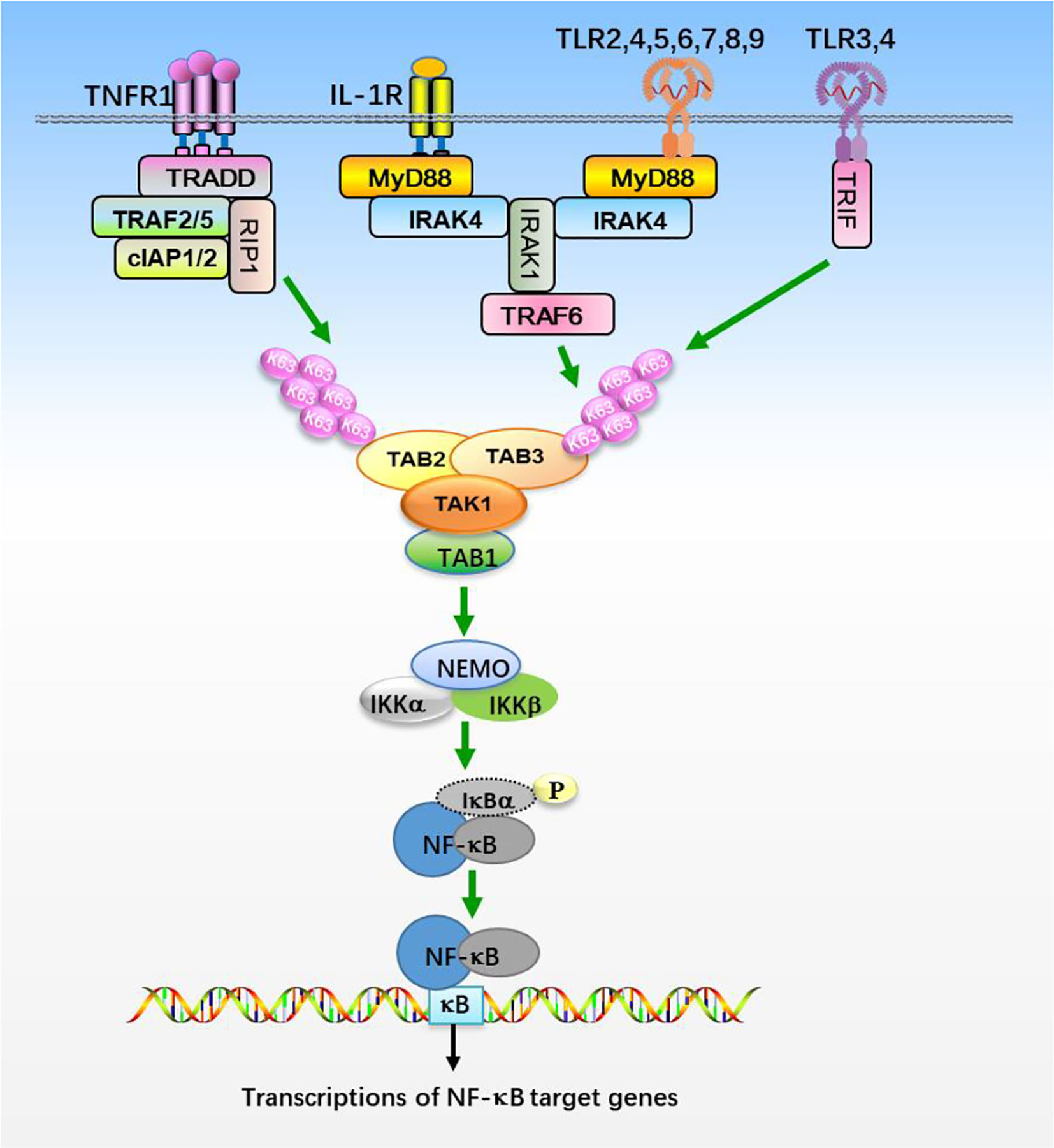

TAK1 is activated by proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-1β, and mediates activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 (19, 23, 52). IL-1β is an effective inflammatory cytokine that activates NF-κB and other signaling pathways, which are essential for an effective immune response against microbial infections (53, 54). IL-1β exerts its biological function through the binding to interleukin-1 receptor type 1 (IL-1R1), which contains intracellular Toll and IL1 receptor (TIR) domains (Figure 1). After binding to IL-1β, IL-1R1 forms hetero-oligomers with IL-1R accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) and recruits the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88). MyD88 in turn recruits IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) and IRAK1. IRAK4 phosphorylates IRAK1 and releases IRAK1 into the cytoplasm to form signalosome with E3 ligase TRAF6 and induce oligomerization of TRAF6, which in turn triggers its activation (55–61). Activated TRAF6 then functions with E2 enzymes Ubc13 and Uev1A to catalyze the synthesis of unanchored Lys-63 (K63)-linked polyubiquitin chains, which preferentially bind to highly conserved zinc finger (ZnF) domain of TAB2 and TAB3, leading to the oligomerization and autophosphorylation of TAK1 at Thr184 and Thr187 (28, 46, 62–66). TAK1 then phosphorylates IKKs and MAPKs, leading to the activation of NF-κB and AP-1. Interestingly, TRAF6 is also ubiquitinated in the presence of Ubc5 but not Ubc13-Uev1A, which specifically activates IKKs by directly binding to NEMO, thereby facilitating IKKs activation by TAK1 (62, 66, 67). TNF signals though two receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2 (Figure 1). The binding of TNF to TNFR triggers recruitment of downstream adaptor TNFR-associated protein with a death domain (TRADD) (68, 69). TRADD further recruits TRAF2, TRAF5, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (cIAP1), cIAP2, and receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) to form a receptor complex, where TRAF2 and TRAF5 catalyze K63-linked polyubiquitination of RIP1 (52, 70, 71). The K63 ubiquitin chains recruit TAB2 and TAB3 and form a signal complex with TAK1, which in turn activates TAK1 and leads to the phosphorylation and activation of IKKs (28, 62, 64, 66). IKKs further activates transcription factor NF-κB and elicits the transcription of downstream genes.

Figure 1 The NF-κB signaling pathway. Stimulation of TNFR1, IL-1R, and TLRs with their ligands promotes recruitments of the indicated adaptor proteins and E3 ligases, which catalyzes the synthesis of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains that preferentially bind to TAB2 and TAB3 subunits, resulting in the assembly and activation of TAK1-TABs complex. TAK1-TABs then phosphorylates IKKs, which activates transcription factor NF-κB and elicits the transcription of downstream genes.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are the most well-studied pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and responsible for recognizing the microbial components and intermediates produced during replication, leading to the activation of TAK1 and initiating immune and inflammatory responses (60, 61). Studies of mice deficient in each TLR have shown that TLRs are distinct in their ligand recognition and usage of intracellular adaptor proteins. TLRs have an ectodomain with leucine-rice repeat (LRR) that mediates recognition of pattern-associated recognition patterns (PAMPs), a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic tail with a Toll/interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor (TIR) domain that initiates signal transduction (Figure 1). Individual TLRs differentially recruit adaptors containing the TIR domain, such as MyD88, TRIF (TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β), TIRAP (TIR domain-containing adaptor protein), and TRAM (TRIF related adaptor molecule) (61). Except TLR3 signals through TRIF, most TLRs utilize MyD88 for signaling and ultimate activation of NF-κB and MAPKs (61, 72). After TLRs engagement, MyD88 is recruited to TIR domain of TLRs and forms a complex with IRAK1 and IRAK4, where IRAK1 is autophosphorylated or phosphorylated by other kinases (60, 61, 72). Then IRAK1 is released from MyD88 and interacts with E3 ligases TRAF3 and TRAF6. TRAF6 functions with E2 enzymes, Ubc13 and Uev1A, promotes K63-linked polyubiquitination of target proteins, including TRAF6 itself and NEMO (6, 46, 64, 72). Ubiquitinated TRAF6 subsequently recruits TAK1 and TABs, which then activates the IKK complex and MAPKs pathways, respectively (72). Thus the TAK1-TABs complex is critical for TLRs-mediated signaling.

Immune Regulation of TAK1-TABs-Mediated Signaling by Post-Translational Modifications

Because TAK1-TABs complex exerts essential roles in diverse signaling pathways in response to a wide range of immune stimulation, the regulation of TAK1-TABs-mediated signal cascades have been extensively investigated. TAK1-TABs complex is heavily and dynamically modulated by different post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, methylation, acylation, O-GlcNAcylation, and sumoylation, which play important roles in regulating the activity, stability, as well as assembly of TAK1-TABs complex, fine-turning the inflammatory responses. We next summarize the roles and mechanisms of the different PTMs of TAK1-TABs.

Phosphorylation-Mediated Regulation of TAK1-TABs Signalosome

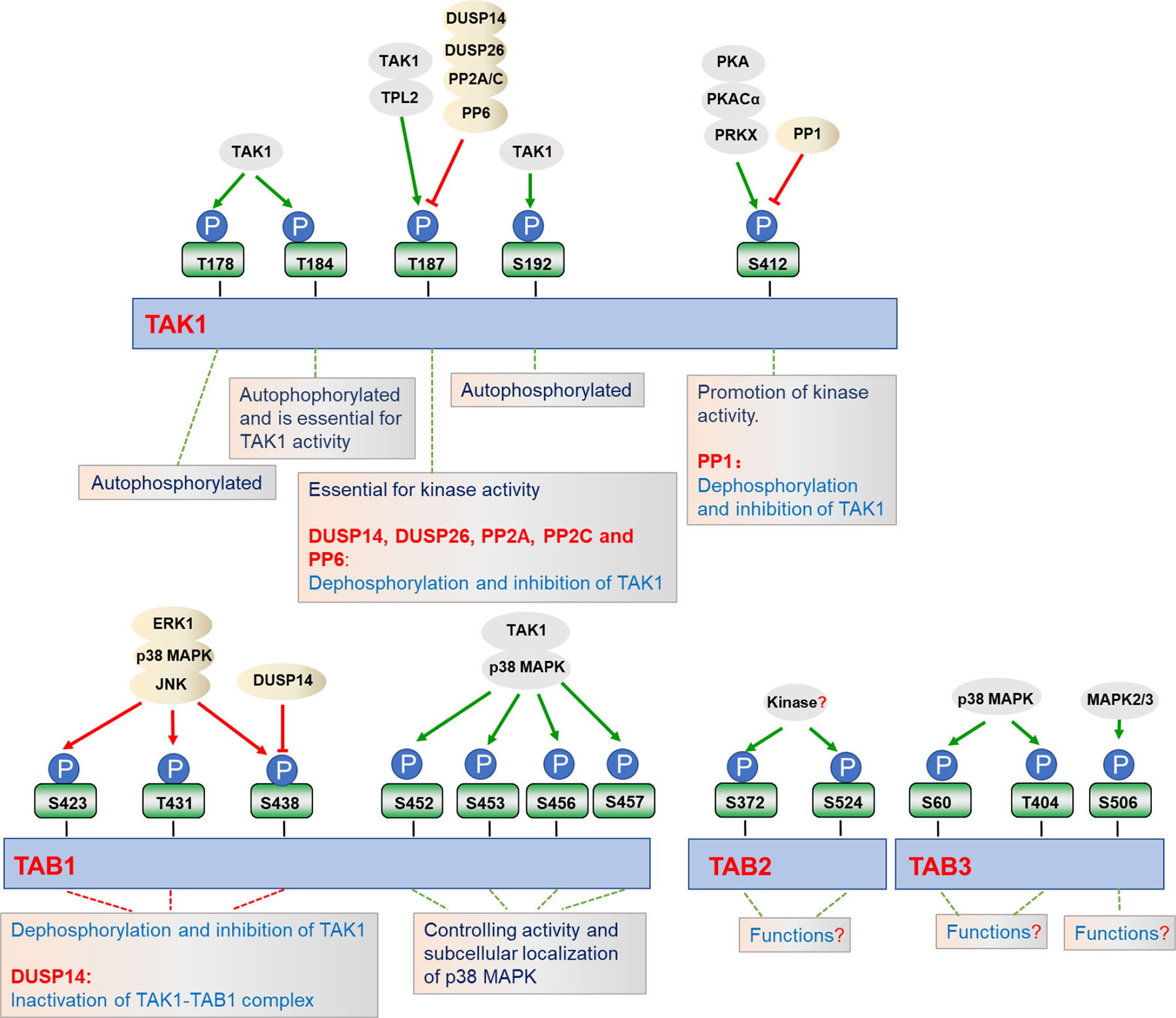

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of critical serine or threonine residues in the activation loop of TAK1 are critical for its kinase activity (Figure 2). Four conserved serine and threonine residues, Thr178, Thr184, Thr187, and Ser192, within the kinase activation loop of TAK1 have been reported to be essential for TAK1-mediated activation of NF-κB and AP-1 (23, 38, 63, 73–75). Upon stimulation with inflammatory cytokines, TAK1 undergoes autophosphorylation at Thr187 and Ser192, and then associates with TAB2 and TAB3 (75, 76). Interestingly, deficiency of TAB1 almost completely inhibits TAK1 kinase activity, but TAB1-deficiency has minor effects on phosphorylation of TAK1 at Thr187 and activation of NF-κB stimulated with TNF and IL-1, suggesting that the phosphorylation on Thr187 is dispensable for TAB1 and sufficient for TAK1-mediated activation of NF-κB and MAPKs (23, 37, 39, 77, 78). Prickett et al. have shown that the protein phosphatase subunit known as type 2A phosphatase-interacting protein (TIP) has TAB-qualified properties, so it is also named TAB4. TAB4 directly binds to and enhances the autophosphorylation of TAK1 at Thr178, Thr184, Thr187, and Ser192, which further specifically promotes the phosphorylation of IKKβ and the activation of NF-κB (79). The Thr187 of TAK1 is also phosphorylated by other kinases, such as tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2). TPL2 associates with and phosphorylates TAK1 at Thr187 after IL-17 stimulation, thereby promoting auto-immune neuroinflammation (80). The phosphorylation of TAK1 at Thr187 is critical for TAK1-mediated signal transduction, and a series of phosphatases have been reported to regulate TAK1 activity at different stages following stimulation (75). Dual-specificity phosphatase 14 (DUSP14) associates with and dephosphorylates TAK1 at Thr187, which inhibits TNFα- or IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation. In contrast, DUSP14 enzymatic-inactive mutant DUSP14 (C111S) lost its ability to dephosphorylate TAK1 or inhibit NF-κB activation after simulation (81, 82). Recently, Ye et al. found that another DUSP member, DUSP26, directly binds to TAK1 and mediates dephosphorylation of TAK1, resulting in the alleviation of hepatic steatosis and metabolic disturbance (83). In addition, protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) and PP6 also dephosphorylate TAK1 at Thr187, but they seem to function on different forms of TAK1. PP2C inhibits TAK1 activity in unstimulated cells, while releasing from TAK1 complex and participating in TAK1 activation after cytokines stimulation. In contrast, PP6 only dephosphorylates TAK1 in an IL-1β-dependent manner, but it has minor effects on TAK1 activity in the resting cells. Moreover, PP2A and PP2C also mediate dephosphorylation of TAK1 at Thr187 after TGF-α and IL-1β stimulation, respectively (84, 85). Yasuhiro et al. found that the phosphorylation at Ser412 is also important for TAK1 activation (86). cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) mediates the phosphorylation of TAK1 at Ser412, and enhanced activation of NF-κB and MAPKs, which is essential for cAMP/PKA-induced osteoclastic differentiation and cytokine production in precursor cells (76). Dr. Xia’s group showed that the phosphorylation of TAK1 at Ser412 is also mediated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit α (PKACα) and X-linked protein kinase (PRKX) in TLR- and IL-1R-triggered signaling independent of PKA activation agents (76). It remains to be investigated whether PKACα and PRKX collaborate in promoting the phosphorylation of TAK1 at Ser412. In contrast, PP1 together with its regulatory subunit DNA damage-inducible protein 34 (GADD34) synergistically dephosphorylate TAK1 at Ser412. PP1 and GADD34 associate with TAK1 in unstimulated cells, while disassociating immediately from TAK1 after ligand stimulation, and then quickly interacting with TAK1 again. The cycling of association and disassociation of TAK1 with PP1 thus dynamically controls the activation of IL-1R/TLR signaling and protects the host from excessive inflammatory immune responses (87).

Figure 2 Regulation of TAK1-TABs complex by phosphorylation. TAK1-TABs complex is heavily and dynamically modified with phosphorylation (P) and dephosphorylation by the indicated kinases or phosphatases, which regulates their activity and subcellular localizations.

In addition to the modifications of TAK1, TAK1-binding proteins TAB1, TAB2, and TAB3 are also phosphorylated in response to the different stimulation. It has been reported that the four serine residues of TAB1, including Ser452, Ser453, Ser456, and Ser457, can be phosphorylated by TAK1 as well as by p38 MAPK in response to IL-1α, anisemycin, and sorbitol. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of TAB1 at these four serine residues inhibits TAB1-dependent phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, but it does not affect the activation of TAK1, suggesting these phosphorylation may have unknown roles in stimulus-specific activation of TAK1-TAB1-mediated signaling (88). Through mass spectrometry and phosphosite-specific antibodies, TAB1 is also shown to be phosphorylated on S423, T431, and S438 by ERK1, p38 MAPK, or JNK, which in turn dephosphorylates and inactivates TAK1 (39, 42). Unlike TAB1, IL-1β-induced phosphorylation of TAB2 at Ser372 and Ser524 are dispensable for p38 MAPK or JNK. In contrast, Ser60 and Thr404 of TAB3 are phosphorylated directly by p38 MAPK, where Ser506 is phosphorylated by mitogen activating protein kinase (MAPK2) and MAPK3, protein kinases which are activated by p38 MAPK (39). Moreover, serine/threonine phosphatases PP2C-, PP6-, or calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation of TABs may cause their inactivation (84, 85, 89). In addition to their function at TAK1, DUSP14 also directly interacts with and dephosphorylates TAB1 at Ser438, leading to the inactivation of TAK1-TAB1 complex in T cells, which negatively regulates TCR signaling and immune responses (81). IL-1α and IL-1β induce phosphorylation of TAB2 at Ser372 and Ser524 or TAB3 at Ser60, Thr404, and Ser506, but the physiological roles of phosphorylation at these sites have yet to be determined (39). Although the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of TAK1-TABs complex have been extensively studied, the exact dynamic regulation in specific cells and tissues across different stresses are still largely unknown, and potential new kinases and phosphatases function at TAK1-TABs complex need to be identified in future studies.

Ubiquitination-Mediated Regulation of TAK1-TABs Signalosome

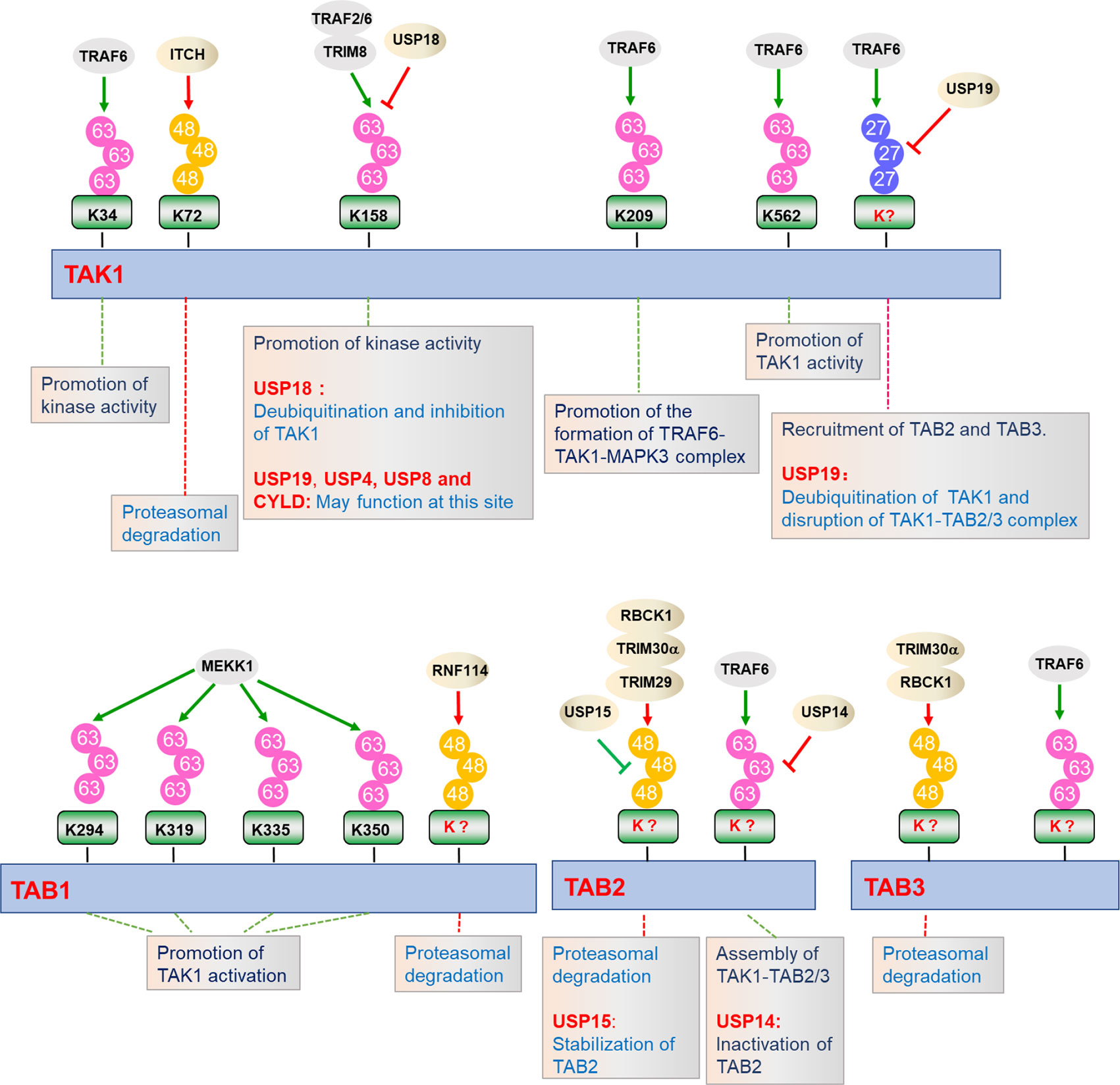

Ubiquitin is a 76 amino acids protein containing 7 lysine (K) residues, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63, any of which can participate in the formation of specific polyubiquitin chains, leading to different destiny of the target proteins (90, 91). It is well established that ubiquitination plays crucial roles in the regulation of TAK1-TABs complex activation (Figure 3). Several lysine residues of TAK1, such as Lys34, Lys158, Lys209, and Lys562, have been identified as potential sites for polyubiquitination. Among them, ubiquitination of TAK1 at K158 is required for TAK1-mediated signaling pathways (52, 92, 93). In response to IL-1β, IRAK1 is phosphorylated and released to the cytoplasm with TRAF6, and TRAF6 then collaborates with Ubc13-Uve1A to catalyze the synthesis of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains at Lys158 of TAK1 (52, 94). Our group has found that tripartite motif (TRIM)-containing proteins 8 (TRIM8) serves as a critical regulator of TNFα- and IL-1β-triggered NF-κB activation by mediating K63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys158 (67). Whether TRAF6 and TRIM8 collaborate or are redundant is unclear. In addition, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) potentiates TRAF6-mediated polyubiquitination of TAK1 at K158, which is essential for anti-H. pylori immune response (95). Chen et al. have further shown that K63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys562 is a prerequisite for the phosphorylation of TAK1 and specifically contributes to the activation of MAPKs, but had minor effect on the formation of TAK1-TABs complex (47). However, the studies of polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys34 and Lys209 are still controversial. It has been reported that TRAF6-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys34 is important for TAK1 activation in TGF-β signaling pathway (65, 96). When the Lys34 of TAK1 is replaced with arginine (R), the activation of NF-κB and p38 will be impaired after stimulated with LPS, TNFα, IL-1β, or TGF-β, which proves that polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys34 is important for the activation of p38 and NF-κB (96, 97). In addition, TRAF6 also mediates the polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys209 and promotes the formation of TRAF6-TAK1-MEKK3 signal complex, thereby promoting the continuous activation of NF-κB (65). However, Fan et al. showed that Lys34 and 209 are dispensable for IL-1β-triggered activation of TAK1. Reconstitution of TAK1-deficient MEFs with K209R or K34R mutant of TAK1 could restore the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs to the same level as wild-type TAK1 does after IL-1β stimulation, which suggest that TAK1 activation does not necessarily require polyubiquitination at Lys34 and Lys209 (92, 98). It is possible that Lys34 and Lys209 are differentially required for TAK1 activation in different signaling or different cell types or tissues. Therefore, further research is needed to investigate the physiological functions of K63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys34 and Lys209. In addition, TAK1 is also regulated by other types of polyubiquitination. Recently, our group found that TRAF6 mediates K27-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1, which is a prerequisite for the recruitments of TAB2 and TAB3 to TAK1 to form the TAK1-TABs complex (94).

Figure 3 Regulation of TAK1-TABs complex by ubiquitination. TAK1-TABs complex are dynamically modified with K27-, K48-, and K63-linked polyubiquitination by the indicated E3 ubiquitin ligases or deubiquitinating enzymes, which play important roles in regulating the stability, assembly, and activation of TAK1-TABs complex.

Polyubiquitination also functions to inhibit TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation by diverse mechanisms. Recently, it has been reported that ITCH (AIP4) inhibits doxycycline (Dox)-induced NF-κB activation by catalyzing K48-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at Lys72 residue and promoting TAK1 degradation. Lacking of ITCH results in continuous activation of TAK1 and increased cytokine production in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), leading to non-small-cell lung cancer (99, 100).

Emerging evidence indicates that TAB1, TAB2, and TAB3 are modified by a series of E3 ubiquitin ligases, determining their functionality. MEKK1 (also known as MAP3K1) is the only MAP3K that contains PHD motif, which is predicted to function as E3 ligase. During the ES-cell differentiation and tumorigenesis, MEKK1 promotes the ubiquitination of TAB1, which is critical for the activation of MAPKs (101, 102). On the contrary, E3 ubiquitin ligase ITCH directly binds to TAB1 and mediates K48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation of TAB1, which inhibits p38 signaling and skin inflammation in mice (103). RNF114 catalyzes K48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation of TAB1 during maternal to zygotic transition (MZT), which links maternal clearance to early embryo development (104). TAB2 and TAB3 are ubiquitinated by TRAF6 after TNFα and IL-1β stimulation, which facilitates assembly of TAK1-TABs complex (28, 40). TRIM30α is induced by TLR ligands in a NF-κB-dependent manner and targets TAB2 and TAB3 for ubiquitination and degradation, which inhibits TLRs-mediated inflammatory responses (105). Recently, another TRIM family member, TRIM29, has been reported to catalyze the ubiquitination and degradation of TAB2, which impairs IFN-γ production and disordered NK cell functions (106). RBCC (RING-finger, two B-boxes, and α-helical coiled-coil domain) protein interacting with protein kinase C1 (RBCK1) is associated with and ubiquitinates TAB2 and TAB3, which leads to their degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner. Deficiency of RBCK1 potentiates TNFα- and IL-1β-triggered activation of NF-κB (54). In addition, other E3 ligases, including RNF4 and TRIM38, are reported to promote degradation of TAB2 and TAB3 dispensable for their ubiquitin ligase activities (107–109).

Considering the important roles of ubiquitination in TAK1-TABs-mediated signaling, the reverse deconjugation process of ubiquitination would be as equally important (Figure 3). Deubiquitination is mediated by a group of proteins called deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which consists of four families. Among them, the ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) are widely studied and contribute to the regulation of inflammatory responses (110). Recently, our group found that USP19 is associated with TAK1 in a TNFα- or IL-1β-dependent manner and specifically deconjugates K63- and K27-linked polyubiquitin chains from TAK1, leading to the impairment of TAK1 activity and the disruption of TAK1-TAB2/3 complex. USP19-deficient mice produced higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines and were more susceptible to TNFα- and IL-1β-induced death (94). Unlike USP19, USP18 is an interferon inducible gene (ISG), which is upregulated by TLR ligands in immune cells. USP18 is associated with and removes K63-linked ubiquitin moieties from TAK1-TAB1 complex, thereby negatively regulating TAK1-TABs activity during Th17 differentiation (111, 112). USP18 is expressed at higher levels in Th0, Th1, and Th17 cells than in inducible regulatory T cells, Th2 cell, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). In contrast, USP19 is abundantly expressed in inducible regulatory T cells, Th2, BMDMs, and BMDCs but not in Th0, Th1, and Th17 cells. These observations suggest that USP18 and USP19 deubiquitinate TAK1 in a cell type-specific dependent manner (94, 111). In addition, another ubiquitin-specific protease, USP4, also serves as a critical inhibitor of TNFα-triggered NF-κB activation by removing the K63-linked polyubiquitin moieties from TAK1 (113). Recently, Wang et al. found that p38‐interacting protein (p38IP) inhibits TCR- and LPS-triggered cytokines production. Mechanistically, p38IP dynamically interacts with TAK1 and promotes USP4-dependent deubiquitination of TAK1. Moreover, p38IP also inhibits the unanchored K63-linked ubiquitin chains binding to TAK1 (114). TAK1 activity can also be terminated by deubiquitinase cylindromatosis (Cyld) and E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch complex. In response to TNFα and IL-1β, Cyld expression is upregulated to form a complex with Itch through WW-PPXY motif. Cyld specifically removes K63-linked polyubiquitin moieties from TAK1 and consequent to the inhibition of TAK1 activity. In addition, its partner Itch mediates K48-linked ubiquitination of TAK1, which is then degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner (99, 115). Consistently, Cyld- and Itch-double deficiency leads to chronic and sustained production of inflammatory cytokines by tumor-associated macrophages and aggressive growth of lung carcinoma (99, 100, 115–117). Intermittent hypoxia/reoxygenation (IHR) has been reported to contribute to the activation of NF-κB as well as the induction of inflammatory cytokines. Zhang et al. found that USP8 suppresses the IHR-induced activation of NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokines production by removing K63-linked polyubiquitination moieties from TAK1 (118).

In addition to TAK1, TABs are also regulated by deubiquitinating enzymes. Recently, Zhou et al. found that USP15 specifically removes K48-linked polyubiquitin moieties from TAB2 and prevents its lysosome-associated degradation in both DUB activity dependent and independent manner, thus stabilizing TAB2 after TNFα and IL-1β stimulation. On the other hand, USP15 inhibited autophagy cargo receptor 1 (NBR1)-mediated selective autophagic degradation of TAB3. Collectively, USP15 positively regulates TNFα- and IL-1β-triggered NF-κB activation by distinct mechanisms, which reflects the potential nonredundant roles of TAB2 and TAB3 (119). In contrast, USP14 interacts with and removes polyubiquitin moieties from TAB2 and inhibits TAB2 activity. USP14-deficient THP-1 cells showed enhanced activation of NF-κB and production of inflammatory cytokines after LPS stimulation, which suggests that USP14 negatively regulates TLR4-mediated inflammatory responses by deubiquitinating TAB2 (120).

While the ubiquitination and deubiquitination of TAK1-TABs have been extensively studied, and a large number of E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes have been identified, the exact dynamic regulation of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in specific cells in response to different stimuli are still unclear. Therefore, further investigations on these questions and other outstanding questions need to be clarified in future studies.

Unconventional PTMs-Mediated Regulation of TAK1-TAB Signalosome

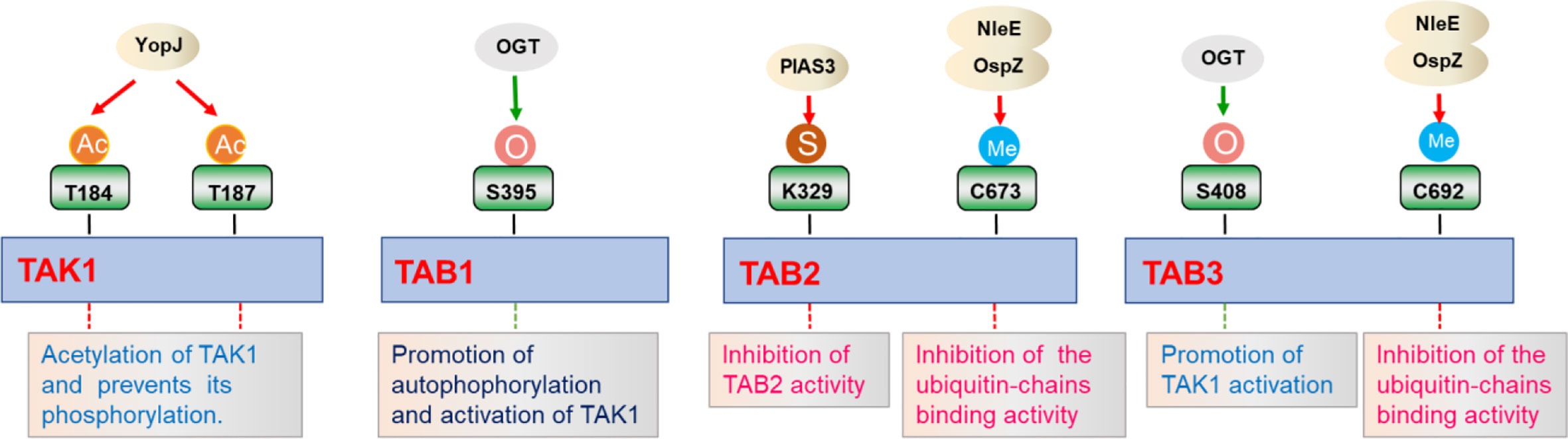

In addition to the more extensively characterized phosphorylation and ubiquitination, TAK1-TABs are also modified by other post-translational modifications, including methylation, O-GlcNAcylation, and sumoylation (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Regulation of TAK1-TABs complex by different post-translational modifications. TAK1-TABs complex is modified by various post-translational modifications including acylation (Ac), methylation (Me), sumoylation (S), and O-GlcNAcylation (O), which regulates the activation and the assembly of the complex in response to different stimulation.

Protein methylation is a post-translational modification that transfers a methyl group from the donor S-adenosyl-L-methionine to cytosine in CpG dinucleotides (121–123). Initially, protein methylation was first identified as a modification that regulates chromatin remodeling and gene transcription (121). Up to now, methylation of Lysine or Argine residues on non-histone proteins is an emerging field, displaying important roles in the regulation of signaling for diverse array of pathways (121). NleE, a bacterial type III secreted effector, harbored unprecedented S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase activity. After Escherichia coli infection, NleE is released into the cytoplasm and specifically methylates TAB2 at Cys673 and TAB3 at Cys692 in their NZF domain, which diminishes their ubiquitin binding capacity and consequent to the inhibition of inflammatory cytokines expression (121, 124, 125). Similar results are also observed for NleE homolog OspZ from Shigella flexneri, which reduces IL-8 transcription by methylating TAB2 and TAB3 (121, 126). In addition to methylation, protein acetylation is also one of the common post-translational modifications in eukaryotes. Bacterial effectors from Yersinia can act as acetyltransferases to mediate acetylation at the phosphorylation sites of MKK6, IKKα, and IKKβ, thereby inhibiting their phosphorylation and activation. YopJ is one of six effector proteins (Yops) injected into the host cell cytoplasm through type III secretion system during Yersinia pestis infection, and inhibits mammalian NF-κB and MAPKs signaling pathways (127, 128). Recent studies indicate that YopJ acts as a serine/threonine acetyltransferase that targets dTAK1. Acetylation of key serine/threonine residues in the activation loop of Drosophila TAK1 prevents its phosphorylation and subsequent inhibition of kinase activation. Furthermore, YopJ also inhibits TAK1 activity in mammalian cells. YopJ prevents phosphorylation of TAK1 by acetylating TAK1 at Thr184 and Thr187, inhibiting autophosphorylation of this kinase. These data demonstrate that YopJ inhibits innate immune responses by acylating TAK1 (129). However, work on methylation or acylation influencing NF-κB signaling pathway is relatively limited, and further exploration is need to identify new methyltransferases or acetyltransferases involved in TAK1-TABs-mediated signaling, especially in mammal cells.

Like other post-translational modifications, sumoylation is a dynamic process that is mediated by E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, and has a pivotal role in a range of cellular functions (130). SUMO is an ubiquitin-like protein that binds to many target proteins in a covalently binding manner. Wang et al. have shown that TAB2 could be modified by SUMO at evolutionarily conserved Lys 329. In addition, PIAS3 is identified as a SUMO E3 ligase that interacts with and promotes sumoylation of TAB2. Interestingly, PIAS3 inhibits TAB2 activity in a dose-dependent manner, while blocking of sumoylation caused by Lys 329 mutation enhanced TAB2 activity (131). Although this study provides evidence supporting a role of sumoylation in the regulation of TAK1-TABs-mediated signaling, the examination of sumoylation in vivo and related mechanisms needs to been further investigated. In addition, it will be interesting to identify other new E3 ligases or desumoylating enzymes that are responsible for modulating sumoylation states of TAK1-TABs complex.

O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) is a ubiquitous dynamic post-translational modification known to target more than 3,000 eukaryotic proteins (132). O-GlcNAcylation is thought to regulate proteins in a manner similar to protein phosphorylation, and this modification regulates many cellular functions, such as cellular stress responses. TAB1 is modified at Ser395 by O-GlcNAcylation, which is important for autophosphorylation of TAK1 at Thr187 and activation of NF-κB signaling (132, 133). This is one of the first cases of a single O-GlcNAcylation site on a signaling protein that regulates key innate immune signaling pathways. After that, Tao et al. found that TAB3 is also modified by O-GlcNAcylation at the Ser408 position, which is necessary for TAK1 activation. Excessive O-GlcNAcylation modification of TAB3 will over-induce the activation of TAK1, which is related to tumor progression (134). Collectively, the regulation of O-GlcNAcylation of TAK1-TABs complex is important for immune and inflammatory responses and tumorigenesis.

Conclusions and Perspectives

A series of knockout experiments proved that the TAK1-TABs complex is essential for IL-1R-, TNFR-, and TLRs-mediated signaling pathways that lead to activation of MAPKs and NF-κB (135). TAK1-TABs complex-mediated signaling is also correlated with a variety of diseases. TAK1-deficiency causes abnormal cell differentiation, increased cell death, and decreased inflammatory responses (49). In addition, TAK1-TABs is also associated with contact hypersensitivity (136) and neuronal death during cerebral ischemia (29). TAK1-TABs over-activation is related to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases and the development of cancer (49).

Although our understanding of the PTMs of TAK1-TABs has made significant progress, except for ubiquitination and phosphorylation, little is known about the functional role of other PTMs. And whether there are other forms of PTMs that have functional roles in regulating the TAK1-TABs complex and how these PTMs are related to each other is still unknown. In the future, we hope that more research will use high-resolution mass spectrometry measurement and advanced analysis technology platforms to perform more specific and sensitive detection of new protein changes of TAK1-TABs complex, and explore more detailed molecular mechanisms behind these modifications. These efforts will expand our understanding of inflammation and related cellular and molecular mechanisms, and provide new methods and strategies for effective control and treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Author Contributions

C-QL conceived and designed this review. Y-RX and C-QL performed manuscript preparation, literature search, and editing. C-QL and Y-RX wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research in the authors’ laboratory was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870870, 32070773), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042019kf0204), the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology Grant (SKLVEB2020KFKT002), the Wuhan University Experiment Technology Project Funding (WHU-2020-SYJS-05), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2018CFA016).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Medzhitov R, Horng T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9:692–703. doi: 10.1038/nri2634

2. Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature (2006) 444:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05485

3. Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature (2008) 454:428–35. doi: 10.1038/nature07201

4. Matsuzawa-Ishimoto Y, Hwang S, Cadwell K. Autophagy and Inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol (2018) 36:73–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053253

5. Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol (1998) 16:225–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225

6. Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev (2004) 18:2195–224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704

7. Baldwin AS Jr. The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol (1996) 14:649–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649

8. Chen ZJ. Ubiquitination in signaling to and activation of IKK. Immunol Rev (2012) 246:95–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01108.x

9. Xu M, Skaug B, Zeng W, Chen ZJ. A ubiquitin replacement strategy in human cells reveals distinct mechanisms of IKK activation by TNFalpha and IL-1beta. Mol Cell (2009) 36:302–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.002

10. Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. IkappaB kinases: key regulators of the NF-kappaB pathway. Trends Biochem Sci (2004) 29:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.003

11. Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, Chariot A. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB and IkappaB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends Biochem Sci (2005) 30:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.009

12. Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell (2008) 132:344–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020

13. Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:695–708. doi: 10.1038/ni.2065

14. Wullaert A, Bonnet MC, Pasparakis M. NF-kappaB in the regulation of epithelial homeostasis and inflammation. Cell Res (2011) 21:146–58. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.175

15. Shibuya H, Iwata H, Masuyama N, Gotoh Y, Yamaguchi K, Irie K, et al. Role of TAK1 and TAB1 in BMP signaling in early Xenopus development. EMBO J (1998) 17:1019–28. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1019

16. Yamaguchi K, Shirakabe K, Shibuya H, Irie K, Oishi I, Ueno N, et al. Identification of a member of the MAPKKK family as a potential mediator of TGF-beta signal transduction. Science (1995) 270:2008–11. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.2008

17. Mukhopadhyay H, Lee NY. Multifaceted roles of TAK1 signaling in cancer. Oncogene (2020) 39:1402–13. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1088-8

18. Vidal S, Khush RS, Leulier F, Tzou P, Nakamura M, Lemaitre B. Mutations in the Drosophila dTAK1 gene reveal a conserved function for MAPKKKs in the control of rel/NF-kappaB-dependent innate immune responses. Genes Dev (2001) 15:1900–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.203301

19. Silverman N, Zhou R, Erlich RL, Hunter M, Bernstein E, Schneider D, et al. Immune activation of NF-kappaB and JNK requires Drosophila TAK1. J Biol Chem (2003) 278:48928–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304802200

20. Shim JH, Xiao C, Paschal AE, Bailey ST, Rao P, Hayden MS, et al. TAK1, but not TAB1 or TAB2, plays an essential role in multiple signaling pathways in vivo. Genes Dev (2005) 19:2668–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.1360605

21. Takaesu G, Surabhi RM, Park KJ, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Gaynor RB. TAK1 is critical for IkappaB kinase-mediated activation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Mol Biol (2003) 326:105–15. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01404-3

22. Sun SC. The noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway. Immunol Rev (2012) 246:125–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01088.x

23. Dai L, Aye Thu C, Liu XY, Xi J, Cheung PC. TAK1, more than just innate immunity. IUBMB Life (2012) 64:825–34. doi: 10.1002/iub.1078

24. Chang JH, Hu H, Sun SC. Survival and maintenance of regulatory T cells require the kinase TAK1. Cell Mol Immunol (2015) 12:572–9. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.27

25. Shinohara H, Nagashima T, Cascalho MI, Kurosaki T. TAK1 maintains the survival of immunoglobulin lambda-chain-positive B cells. Genes to Cells (2016) 21:1233–43. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12442

26. Ajibade AA, Wang HY, Wang RF. Cell type-specific function of TAK1 in innate immune signaling. Trends Immunol (2013) 34:307–16. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.03.007

27. Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-I kappaB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature (1999) 398:252–6. doi: 10.1038/18465

28. Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat Cell Biol (2005) 7:758–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758

29. Neubert M, Ridder DA, Bargiotas P, Akira S, Schwaninger M. Acute inhibition of TAK1 protects against neuronal death in cerebral ischemia. Cell Death Differ (2011) 18:1521–30. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.29

30. Komatsu Y, Shibuya H, Takeda N, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yasui T, Miyado K, et al. Targeted disruption of the Tab1 gene causes embryonic lethality and defects in cardiovascular and lung morphogenesis. Mech Dev (2002) 119:239–49. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00391-X

31. Tang M, Wei X, Guo Y, Breslin P, Zhang S, Zhang S, et al. TAK1 is required for the survival of hematopoietic cells and hepatocytes in mice. J Exp Med (2008) 205:1611–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080297

32. Ajibade AA, Wang Q, Cui J, Zou J, Xia X, Wang M, et al. TAK1 negatively regulates NF-kappaB and p38 MAP kinase activation in Gr-1+CD11b+ neutrophils. Immunity (2012) 36:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.010

33. Shibuya H, Yamaguchi K, Shirakabe K, Tonegawa A, Gotoh Y, Ueno N, et al. TAB1: an activator of the TAK1 MAPKKK in TGF-beta signal transduction. Science (1996) 272:1179–82. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1179

34. Takaesu G, Kishida S, Hiyama A, Yamaguchi K, Shibuya H, Irie K, et al. TAB2, a novel adaptor protein, mediates activation of TAK1 MAPKKK by linking TAK1 to TRAF6 in the IL-1 signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell (2000) 5:649–58. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80244-0

35. Cheung PC, Nebreda AR, Cohen P. TAB3, a new binding partner of the protein kinase TAK1. Biochem J (2004) 378:27–34. doi: 10.1042/bj20031794

36. Besse A, Lamothe B, Campos AD, Webster WK, Maddineni U, Lin SC, et al. TAK1-dependent signaling requires functional interaction with TAB2/TAB3. J Biol Chem (2007) 282:3918–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608867200

37. Zhang J, Macartney T, Peggie M, Cohen P. Interleukin-1 and TRAF6-dependent activation of TAK1 in the absence of TAB2 and TAB3. Biochem J (2017) 474:2235–48. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170288

38. Kishimoto K, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase is activated by autophosphorylation within its activation loop. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:7359–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7359

39. Mendoza H, Campbell DG, Burness K, Hastie J, Ronkina N, Shim JH, et al. Roles for TAB1 in regulating the IL-1-dependent phosphorylation of the TAB3 regulatory subunit and activity of the TAK1 complex. Biochem J (2008) 409:711–22. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071149

40. Ishitani T, Takaesu G, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Shibuya H, Gaynor RB, Matsumoto K. Role of the TAB2-related protein TAB3 in IL-1 and TNF signaling. EMBO J (2003) 22:6277–88. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg605

41. Kanayama A, Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Hong M, Shaito A, et al. TAB2 and TAB3 activate the NF-kappaB pathway through binding to polyubiquitin chains. Mol Cell (2004) 15:535–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.008

42. Cheung PC, Campbell DG, Nebreda AR, Cohen P. Feedback control of the protein kinase TAK1 by SAPK2a/p38alpha. EMBO J (2003) 22:5793–805. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg552

43. Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. The IkappaB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKalpha and IKKbeta, necessary for IkappaB phosphorylation and NF-kappaB activation. Cell (1997) 91:243–52. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80406-7

44. Israel A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2010) 2:a000158. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000158

45. Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin-mediated activation of TAK1 and IKK. Oncogene (2007) 26:3214–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210413

46. Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature (2001) 412:346–51. doi: 10.1038/35085597

47. Chen IT, Hsu PH, Hsu WC, Chen NJ, Tseng PH. Polyubiquitination of Transforming Growth Factor beta-activated Kinase 1 (TAK1) at Lysine 562 Residue Regulates TLR4-mediated JNK and p38 MAPK Activation. Sci Rep (2015) 5:12300. doi: 10.1038/srep12300

48. Omori E, Matsumoto K, Sanjo H, Sato S, Akira S, Smart RC, et al. TAK1 is a master regulator of epidermal homeostasis involving skin inflammation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem (2006) 281:19610–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603384200

49. Sakurai H. Targeting of TAK1 in inflammatory disorders and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci (2012) 33:522–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.06.007

50. Roh YS, Song J, Seki E. TAK1 regulates hepatic cell survival and carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol (2014) 49:185–94. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0931-x

51. Totzke J, Gurbani D, Raphemot R, Hughes PF, Bodoor K, Carlson DA, et al. Takinib, a Selective TAK1 Inhibitor, Broadens the Therapeutic Efficacy of TNF-alpha Inhibition for Cancer and Autoimmune Disease. Cell Chem Biol (2017) 24:1029–39.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.07.011

52. Fan Y, Yu Y, Shi Y, Sun W, Xie M, Ge N, et al. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at lysine 158 is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-1beta-induced IKK/NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. J Biol Chem (2010) 285:5347–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076976

53. Dunne A, O’Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal transduction during inflammation and host defense. Sci STKE (2003) 2003:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.171.re3

54. Tian Y, Zhang Y, Zhong B, Wang YY, Diao FC, Wang RP, et al. RBCK1 negatively regulates tumor necrosis factor- and interleukin-1-triggered NF-kappaB activation by targeting TAB2/3 for degradation. J Biol Chem (2007) 282:16776–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701913200

55. Verstrepen L, Bekaert T, Chau TL, Tavernier J, Chariot A, Beyaert R. TLR-4, IL-1R and TNF-R signaling to NF-kappaB: variations on a common theme. Cell Mol Life Sci (2008) 65:2964–78. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8064-8

56. Wesche H, Korherr C, Kracht M, Falk W, Resch K, Martin MU. The interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) is essential for IL-1-induced activation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) and stress-activated protein kinases (SAP kinases). J Biol Chem (1997) 272:7727–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7727

57. Wesche H, Henzel WJ, Shillinglaw W, Li S, Cao Z. MyD88: an adapter that recruits IRAK to the IL-1 receptor complex. Immunity (1997) 7:837–47. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80402-1

58. Muzio M, Ni J, Feng P, Dixit VM. IRAK (Pelle) family member IRAK-2 and MyD88 as proximal mediators of IL-1 signaling. Science (1997) 278:1612–5. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1612

59. Cao Z, Henzel WJ, Gao X. IRAK: a kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Science (1996) 271:1128–31. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1128

60. Carpenter S, O’Neill LA. Recent insights into the structure of Toll-like receptors and post-translational modifications of their associated signalling proteins. Biochem J (2009) 422:1–10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090616

61. Kenny EF, O’Neill LA. Signalling adaptors used by Toll-like receptors: an update. Cytokine (2008) 43:342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.010

62. Xia ZP, Sun L, Chen X, Pineda G, Jiang X, Adhikari A, et al. Direct activation of protein kinases by unanchored polyubiquitin chains. Nature (2009) 461:114–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08247

63. Yu Y, Ge N, Xie M, Sun W, Burlingame S, Pass AK, et al. Phosphorylation of Thr-178 and Thr-184 in the TAK1 T-loop is required for interleukin (IL)-1-mediated optimal NFkappaB and AP-1 activation as well as IL-6 gene expression. J Biol Chem (2008) 283:24497–505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802825200

64. Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, et al. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell (2000) 103:351–61. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00126-4

65. Yamazaki K, Gohda J, Kanayama A, Miyamoto Y, Sakurai H, Yamamoto M, et al. Two mechanistically and temporally distinct NF-kappaB activation pathways in IL-1 signaling. Sci Signal (2009) 2:ra66. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000387

66. Wu ZH, Wong ET, Shi Y, Niu J, Chen Z, Miyamoto S, et al. ATM- and NEMO-dependent ELKS ubiquitination coordinates TAK1-mediated IKK activation in response to genotoxic stress. Mol Cell (2010) 40:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.010

67. Li Q, Yan J, Mao AP, Li C, Ran Y, Shu HB, et al. Tripartite motif 8 (TRIM8) modulates TNFalpha- and IL-1beta-triggered NF-kappaB activation by targeting TAK1 for K63-linked polyubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2011) 108:19341–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110946108

68. Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, Goeddel DV. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell (1996) 84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80984-8

69. Hsu H, Xiong J, Goeddel DV. The TNF receptor 1-associated protein TRADD signals cell death and NF-kappa B activation. Cell (1995) 81:495–504. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90070-5

70. Wu CJ, Conze DB, Li T, Srinivasula SM, Ashwell JD. Sensing of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitination by NEMO is a key event in NF-kappaB activation [corrected]. Nat Cell Biol (2006) 8:398–406. doi: 10.1038/ncb1384

71. Li H, Kobayashi M, Blonska M, You Y, Lin X. Ubiquitination of RIP is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem (2006) 281:13636–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600620200

72. Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol (2004) 4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391

73. Sakurai H, Miyoshi H, Mizukami J, Sugita T. Phosphorylation-dependent activation of TAK1 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase by TAB1. FEBS Lett (2000) 474:141–5. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01588-X

74. Scholz R, Sidler CL, Thali RF, Winssinger N, Cheung PC, Neumann D. Autoactivation of transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 is a sequential bimolecular process. J Biol Chem (2010) 285:25753–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093468

75. Singhirunnusorn P, Suzuki S, Kawasaki N, Saiki I, Sakurai H. Critical roles of threonine 187 phosphorylation in cellular stress-induced rapid and transient activation of transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) in a signaling complex containing TAK1-binding protein TAB1 and TAB2. J Biol Chem (2005) 280:7359–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407537200

76. Ouyang C, Nie L, Gu M, Wu A, Han X, Wang X, et al. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) activation requires phosphorylation of serine 412 by protein kinase A catalytic subunit alpha (PKACalpha) and X-linked protein kinase (PRKX). J Biol Chem (2014) 289:24226–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.559963

77. Bertelsen M, Sanfridson A. TAB1 modulates IL-1alpha mediated cytokine secretion but is dispensable for TAK1 activation. Cell Signal (2007) 19:646–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.08.017

78. Inagaki M, Omori E, Kim JY, Komatsu Y, Scott G, Ray MK, et al. TAK1-binding protein 1, TAB1, mediates osmotic stress-induced TAK1 activation but is dispensable for TAK1-mediated cytokine signaling. J Biol Chem (2008) 283:33080–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807574200

79. Prickett TD, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Broglie P, Muratore-Schroeder TL, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, et al. TAB4 stimulates TAK1-TAB1 phosphorylation and binds polyubiquitin to direct signaling to NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem (2008) 283:19245–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800943200

80. Xiao Y, Jin J, Chang M, Nakaya M, Hu H, Zou Q, et al. TPL2 mediates autoimmune inflammation through activation of the TAK1 axis of IL-17 signaling. J Exp Med (2014) 211:1689–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132640

81. Yang CY, Li JP, Chiu LL, Lan JL, Chen DY, Chuang HC, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 14 (DUSP14/MKP6) negatively regulates TCR signaling by inhibiting TAB1 activation. J Immunol (2014) 192:1547–57. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300989

82. Zheng H, Li Q, Chen R, Zhang J, Ran Y, He X, et al. The dual-specificity phosphatase DUSP14 negatively regulates tumor necrosis factor- and interleukin-1-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation by dephosphorylating the protein kinase TAK1. J Biol Chem (2013) 288:819–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.412643

83. Ye P, Liu J, Xu W, Liu D, Ding X, Le S, et al. Dual-Specificity Phosphatase 26 Protects Against Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice Through Transforming Growth Factor Beta-Activated Kinase 1 Suppression. Hepatology (2019) 69:1946–64. doi: 10.1002/hep.30485

84. Hanada M, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Komaki K, Ohnishi M, Katsura K, Kanamaru R, et al. Regulation of the TAK1 signaling pathway by protein phosphatase 2C. J Biol Chem (2001) 276:5753–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007773200

85. Kajino T, Ren H, Iemura S, Natsume T, Stefansson B, Brautigan DL, et al. Protein phosphatase 6 down-regulates TAK1 kinase activation in the IL-1 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem (2006) 281:39891–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608155200

86. Kobayashi Y, Mizoguchi T, Take I, Kurihara S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N. Prostaglandin E2 enhances osteoclastic differentiation of precursor cells through protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of TAK1. J Biol Chem (2005) 280:11395–403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411189200

87. Gu M, Ouyang C, Lin W, Zhang T, Cao X, Xia Z, et al. Phosphatase holoenzyme PP1/GADD34 negatively regulates TLR response by inhibiting TAK1 serine 412 phosphorylation. J Immunol (2014) 192:2846–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302537

88. Wolf A, Beuerlein K, Eckart C, Weiser H, Dickkopf B, Muller H, et al. Identification and functional characterization of novel phosphorylation sites in TAK1-binding protein (TAB) 1. PLoS One (2011) 6:e29256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029256

89. Liu Q, Busby JC, Molkentin JD. Interaction between TAK1-TAB1-TAB2 and RCAN1-calcineurin defines a signalling nodal control point. Nat Cell Biol (2009) 11:154–61. doi: 10.1038/ncb1823

90. Xu P, Duong DM, Seyfried NT, Cheng D, Xie Y, Robert J, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell (2009) 137:133–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041

91. Sun L, Chen ZJ. The novel functions of ubiquitination in signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol (2004) 16:119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.02.005

92. Mao R, Fan Y, Mou Y, Zhang H, Fu S, Yang J. TAK1 lysine 158 is required for TGF-beta-induced TRAF6-mediated Smad-independent IKK/NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. Cell Signal (2011) 23:222–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.09.006

93. Lamb A, Chen J, Blanke SR, Chen LF. Helicobacter pylori activates NF-kappaB by inducing Ubc13-mediated ubiquitination of lysine 158 of TAK1. J Cell Biochem (2013) 114:2284–92. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24573

94. Lei CQ, Wu X, Zhong X, Jiang L, Zhong B, Shu HB. USP19 Inhibits TNF-alpha- and IL-1beta-Triggered NF-kappaB Activation by Deubiquitinating TAK1. J Immunol (2019) 203:259–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900083

95. Lamb A, Yang XD, Tsang YH, Li JD, Higashi H, Hatakeyama M, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA activates NF-kappaB by targeting TAK1 for TRAF6-mediated Lys 63 ubiquitination. EMBO Rep (2009) 10:1242–9. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.210

96. Sorrentino A, Thakur N, Grimsby S, Marcusson A, von Bulow V, Schuster N, et al. The type I TGF-beta receptor engages TRAF6 to activate TAK1 in a receptor kinase-independent manner. Nat Cell Biol (2008) 10:1199–207. doi: 10.1038/ncb1780

97. Hamidi A, von Bulow V, Hamidi R, Winssinger N, Barluenga S, Heldin CH, et al. Polyubiquitination of transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta)-associated kinase 1 mediates nuclear factor-kappaB activation in response to different inflammatory stimuli. J Biol Chem (2012) 287:123–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.285122

98. Fan Y, Yu Y, Mao R, Zhang H, Yang J. TAK1 Lys-158 but not Lys-209 is required for IL-1beta-induced Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination and IKK/NF-kappaB activation. Cell Signal (2011) 23:660–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.017

99. Ahmed N, Zeng M, Sinha I, Polin L, Wei WZ, Rathinam C, et al. The E3 ligase Itch and deubiquitinase Cyld act together to regulate Tak1 and inflammation. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:1176–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.2157

100. Perry WL, Hustad CM, Swing DA, O’Sullivan TN, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. The itchy locus encodes a novel ubiquitin protein ligase that is disrupted in a18H mice. Nat Genet (1998) 18:143–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-143

101. Charlaftis N, Suddason T, Wu X, Anwar S, Karin M, Gallagher E. The MEKK1 PHD ubiquitinates TAB1 to activate MAPKs in response to cytokines. EMBO J (2014) 33:2581–96. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488351

102. Hunter T. The age of crosstalk: phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol Cell (2007) 28:730–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.019

103. Theivanthiran B, Kathania M, Zeng M, Anguiano E, Basrur V, Vandergriff T, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch inhibits p38alpha signaling and skin inflammation through the ubiquitylation of Tab1. Sci Signal (2015) 8:ra22. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005903

104. Yang Y, Zhou C, Wang Y, Liu W, Liu C, Wang L, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF114 and TAB1 degradation are required for maternal-to-zygotic transition. EMBO Rep (2017) 18:205–16. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642573

105. Shi M, Deng W, Bi E, Mao K, Ji Y, Lin G, et al. TRIM30 alpha negatively regulates TLR-mediated NF-kappa B activation by targeting TAB2 and TAB3 for degradation. Nat Immunol (2008) 9:369–77. doi: 10.1038/ni1577

106. Dou Y, Xing J, Kong G, Wang G, Lou X, Xiao X, et al. Identification of the E3 Ligase TRIM29 as a Critical Checkpoint Regulator of NK Cell Functions. J Immunol (2019) 203:873–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900171

107. Tan B, Mu R, Chang Y, Wang YB, Wu M, Tu HQ, et al. RNF4 negatively regulates NF-kappaB signaling by down-regulating TAB2. FEBS Lett (2015) 589:2850–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.051

108. Kim K, Kim JH, Kim I, Seong S, Kim N. TRIM38 regulates NF-kappaB activation through TAB2 degradation in osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation. Bone (2018) 113:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.05.009

109. Hu MM, Yang Q, Zhang J, Liu SM, Zhang Y, Lin H, et al. TRIM38 inhibits TNFalpha- and IL-1beta-triggered NF-kappaB activation by mediating lysosome-dependent degradation of TAB2/3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111:1509–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318227111

110. Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, et al. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell (2005) 123:773–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007

111. Liu X, Li H, Zhong B, Blonska M, Gorjestani S, Yan M, et al. USP18 inhibits NF-kappaB and NFAT activation during Th17 differentiation by deubiquitinating the TAK1-TAB1 complex. J Exp Med (2013) 210:1575–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122327

112. Yang Z, Xian H, Hu J, Tian S, Qin Y, Wang RF, et al. USP18 negatively regulates NF-kappaB signaling by targeting TAK1 and NEMO for deubiquitination through distinct mechanisms. Sci Rep (2015) 5:12738. doi: 10.1038/srep12738

113. Fan YH, Yu Y, Mao RF, Tan XJ, Xu GF, Zhang H, et al. USP4 targets TAK1 to downregulate TNFalpha-induced NF-kappaB activation. Cell Death Differ (2011) 18:1547–60. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.11

114. Wang XD, Zhao CS, Wang QL, Zeng Q, Feng XZ, Li L, et al. The p38-interacting protein p38IP suppresses TCR and LPS signaling by targeting TAK1. EMBO Rep (2020) 21:e48035. doi: 10.15252/embr.201948035

115. Reiley WW, Jin W, Lee AJ, Wright A, Wu X, Tewalt EF, et al. Deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD negatively regulates the ubiquitin-dependent kinase Tak1 and prevents abnormal T cell responses. J Exp Med (2007) 204:1475–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062694

116. Bernassola F, Karin M, Ciechanover A, Melino G. The HECT family of E3 ubiquitin ligases: multiple players in cancer development. Cancer Cell (2008) 14:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.001

117. Melino G, Gallagher E, Aqeilan RI, Knight R, Peschiaroli A, Rossi M, et al. Itch: a HECT-type E3 ligase regulating immunity, skin and cancer. Cell Death Differ (2008) 15:1103–12. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.60

118. Zhang Y, Luo Y, Wang Y, Liu H, Yang Y, Wang Q. Effect of deubiquitinase USP8 on hypoxia/reoxygenationinduced inflammation by deubiquitination of TAK1 in renal tubular epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med (2018) 42:3467–76. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3881

119. Zhou Q, Cheng C, Wei Y, Yang J, Zhou W, Song Q, et al. USP15 potentiates NF-kappaB activation by differentially stabilizing TAB2 and TAB3. FEBS J (2020) 287:3165–83. doi: 10.1111/febs.15202

120. Min Y, Lee S, Kim MJ, Chun E, Lee KY. Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 14 Negatively Regulates Toll-Like Receptor 4-Mediated Signaling and Autophagy Induction by Inhibiting Ubiquitination of TAK1-Binding Protein 2 and Beclin 1. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1827. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01827

121. Biggar KK, Li SS. Non-histone protein methylation as a regulator of cellular signalling and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2015) 16:5–17. doi: 10.1038/nrm3915

122. Wang Q, Liu Z, Wang K, Wang Y, Ye M. A new chromatographic approach to analyze methylproteome with enhanced lysine methylation identification performance. Anal Chim Acta (2019) 1068:111–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2019.03.042

123. Wang Q, Wang K, Ye M. Strategies for large-scale analysis of non-histone protein methylation by LC-MS/MS. Analyst (2017) 142:3536–48. doi: 10.1039/C7AN00954B

124. Zhang L, Ding X, Cui J, Xu H, Chen J, Gong YN, et al. Cysteine methylation disrupts ubiquitin-chain sensing in NF-kappaB activation. Nature (2011) 481:204–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10690

125. Yao Q, Zhang L, Wan X, Chen J, Hu L, Ding X, et al. Structure and specificity of the bacterial cysteine methyltransferase effector NleE suggests a novel substrate in human DNA repair pathway. PLoS Pathog (2014) 10:e1004522. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004522

126. Zhang Y, Muhlen S, Oates CV, Pearson JS, Hartland EL. Identification of a Distinct Substrate-binding Domain in the Bacterial Cysteine Methyltransferase Effectors NleE and OspZ. J Biol Chem (2016) 291:20149–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.734079

127. Mittal R, Peak-Chew SY, McMahon HT. Acetylation of MEK2 and I kappa B kinase (IKK) activation loop residues by YopJ inhibits signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2006) 103:18574–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608995103

128. Mukherjee S, Keitany G, Li Y, Wang Y, Ball HL, Goldsmith EJ, et al. Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by blocking phosphorylation. Science (2006) 312:1211–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1126867

129. Paquette N, Conlon J, Sweet C, Rus F, Wilson L, Pereira A, et al. Serine/threonine acetylation of TGFbeta-activated kinase (TAK1) by Yersinia pestis YopJ inhibits innate immune signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109:12710–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008203109

130. Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M. Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol (2006) 22:159–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093503

131. Wang X, Jiang J, Lu Y, Shi G, Liu R, Cao Y. TAB2, an important upstream adaptor of interleukin-1 signaling pathway, is subject to SUMOylation. Mol Cell Biochem (2014) 385:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1815-3

132. Groves JA, Lee A, Yildirir G, Zachara NE. Dynamic O-GlcNAcylation and its roles in the cellular stress response and homeostasis. Cell Stress Chaperones (2013) 18:535–58. doi: 10.1007/s12192-013-0426-y

133. Pathak S, Borodkin VS, Albarbarawi O, Campbell DG, Ibrahim A, van Aalten DM. O-GlcNAcylation of TAB1 modulates TAK1-mediated cytokine release. EMBO J (2012) 31:1394–404. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.8

134. Tao T, He Z, Shao Z, Lu H. TAB3 O-GlcNAcylation promotes metastasis of triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget (2016) 7:22807–18. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8182

135. Sato S, Sanjo H, Takeda K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T, et al. Essential function for the kinase TAK1 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol (2005) 6:1087–95. doi: 10.1038/ni1255

Keywords: TAK1, TABs, post-translational modifications, NF-κB, inflammation

Citation: Xu Y-R and Lei C-Q (2021) TAK1-TABs Complex: A Central Signalosome in Inflammatory Responses. Front. Immunol. 11:608976. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.608976

Received: 22 September 2020; Accepted: 09 November 2020;

Published: 05 January 2021.

Edited by:

Massimo Gadina, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), United StatesReviewed by:

Neil J. Grimsey, University of Georgia, United StatesJae Hyuck Shim, University of Massachusetts Medical School, United States

Copyright © 2021 Xu and Lei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cao-Qi Lei, Y2FvcWlsZWlAd2h1LmVkdS5jbg==

Yan-Ran Xu

Yan-Ran Xu Cao-Qi Lei

Cao-Qi Lei