- 1Clinical Tuberculosis and Epidemiology Research Center, National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Immunology, School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 3Mycobacteriology Research Center, National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (NRITLD), Masih Daneshvari Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 4Division of Pharmacology, Faculty of Science, Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 5Respiratory Section, Faculty of Medicine, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

- 6Priority Research Centre for Asthma and Respiratory Diseases, Hunter Medical Research Institute, The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Coronaviruses were first discovered in the 1960s and are named due to their crown-like shape. Sometimes, but not often, a coronavirus can infect both animals and humans. An acute respiratory disease, caused by a novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 or SARS-CoV-2 previously known as 2019-nCoV) was identified as the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as it spread throughout China and subsequently across the globe. As of 14th July 2020, a total of 13.1 million confirmed cases globally and 572,426 deaths had been reported by the World Health Organization (WHO). SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the β-coronavirus family and shares extensive genomic identity with bat coronavirus suggesting that bats are the natural host. SARS-CoV-2 uses the same receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), as that for SARS-CoV, the coronavirus associated with the SARS outbreak in 2003. It mainly spreads through the respiratory tract with lymphopenia and cytokine storms occuring in the blood of subjects with severe disease. This suggests the existence of immunological dysregulation as an accompanying event during severe illness caused by this virus. The early recognition of this immunological phenotype could assist prompt recognition of patients who will progress to severe disease. Here we review the data of the immune response during COVID-19 infection. The current review summarizes our understanding of how immune dysregulation and altered cytokine networks contribute to the pathophysiology of COVID-19 patients.

Introduction

In December 2019, a novel Coronavirus (nCoV), emerged in the Huanan wet food Market, where livestock animals are also traded, in Wuhan, Hubei Province in China. However, analysis of the first 41 hospitalized patients suggests that Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading (1).

This resulted in an epidemic of severe pneumonia of unknown cause (2). Genomic sequencing of viral isolates from five patients with pneumonia hospitalized from December 18 to December 29, 2019, indicated the presence of a previously unknown β-CoV strain in patients (3). This nCoV has subsequently spread from the site of the original outbreak in China and was named as SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (WHO) on January 12th 2020 and the disease as COVID-19 on 11th February 2020 (4). It was confirmed as having 75–80% resemblance to the coronavirus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) (5). COVID-19 currently affects 188 countries globally1 and up to July 14th 2020 the cumulative number of confirmed cases were 13.1 million people and at least 572,426 people have died with SARS-CoV-2 infection (6). The mortality rate varies from less than 1% up to 3.7% between countries (7) compared with a mortality rate of less than 0.1% from influenza2. Given the origin of the first case of COVID-19, the infection was probably transmitted from animal to human.

Coronaviruses have caused three epidemics in the past two decades namely, COVID-19, SARS, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) (8). No specific antiviral therapies currently exist but efforts to develop anti-viral therapies and a vaccine are urgently needed. This review summarizes the immune response against SARS-CoV-2 and indicates areas of interest for the development of specific anti-viral therapies against SARS-CoV-2.

Coronavirus

CoV belong to the genus Coronavirus in the Coronaviridae family. CoVs are pleomorphic RNA viruses with special crown-shape peplomers between 80 and 160 nM in size and a genome of 27–32 kb (8). Thus, enveloped CoV are some of the largest known RNA viruses (9, 10). Coronaviruses are able to infect a variety of hosts such as humans and several other vertebrates. They are associated with several respiratory and intestinal tract infections. Pulmonary coronaviruses have long been recognized as harmful pathogens in domesticated animals that also cause upper respiratory tract infections in humans (11).

Four coronavirus genera (α, β, γ, and δ) have been characterized so far, with human coronaviruses (HCoVs) detected as being in either the α (HCoV-229E and NL63) or β (MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1) genera (12). Coronaviruses have a high mutation rate and a high capacity to act as pathogens when present in humans and various animals presenting with a wide range of clinical features. The disease characteristics can range from an asymptomatic course to the requirement of hospitalization in an intensive care unit. Coronaviruses cause infections of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatic, heart, renal and neurologic systems and exacerbations of lung diseases, croup and bronchiolitis (12–23).

Coronaviruses were not considered as highly pathogenic for humans until the outbreak of SARS in 2002–2003. Before these outbreaks the two most well-known types of CoV were CoV OC43 and CoV 229E that induced mild infections in immunocompromised individuals (13, 24, 25). Furthermore, 10 years after the SARS epidemic, another highly pathogenic CoV, MERS-CoV emerged in Middle Eastern countries (2).

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2)

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) catalyses the formation of angiotensin II from angiotensin I and, thereby, plays a key role in the control of cardio-renal function and blood pressure (26). ACE is highly expressed in the human heart, kidney, and testis consistent with its role in cardio-renal function. ACE2 is a novel gene encoding a homolog of ACE (27) that efficiently cleaves the C-terminal residue from several peptides unrelated to the renin–angiotensin system (28). Although highest ACE2 mRNA expression levels were detected in the intestinal epithelium, pulmonary ACE2 expression and function have been given extensive attention in recent years due to the findings that ACE2 serves as the receptor for SARS-CoV (29, 30) and its role in acute lung injury (31). ACE2 expression within bronchial and nasal epithelial cells is mostly localized to goblet and mucociliary cells (30). Recent evidence shows that cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 via ACE2 could be inhibited by a pharmacologic inhibitor of the cellular serine protease TMPRSS2, which is employed by SARS-CoV-2 for S protein priming (32).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 acts as a binding site or receptor for the viral anchoring or spike (S) proteins present on the exterior surfaces of beta coronaviruses (33). Upon viral binding, ACE2 is released from the epithelial cell surface into the airway surface liquid (34) via cleavage by ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (ADAM17) and other sheddases (35, 36). ADAM17 activation also processes the membrane form of the interleukin (IL)-6 receptor (IL-6R)-α to the soluble form (sIL-6Ra) allowing gp130-mediated activation of the transcription factor STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) via an sIL-6Ra-IL-6 complex in a variety of IL-6R-α-negative non-immune cells including airway epithelial cells (37). STAT3 activation, in turn, induces full activation of the pro-inflammatory nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway (37). Thus, SARS-CoV-2 infection in the respiratory tract can activate both NF-κB and STAT3 in a feedforward mechanism (IL-6 amplifier or IL-6 Amp) leading to multiple inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (37). Since IL-6 is a functional marker of cellular senescence, the age-dependent enhancement of the IL-6 Amp might correspond to the age-dependent increase in COVID-19 mortality. Furthermore, the putative driving role of IL-6 in SARS-CoV-2 induced inflammation suggests that inhibition of Janus kinases may be an attractive therapy for severe COVID-19 patients (38).

Airway surface liquid can contain catalytically active shed or soluble ACE2 (sACE2) under both stimulated and constitutive conditions (39). sACE2 acts in a feedback loop to suppress viral entry into cells and suggests that reductions in ACE2 shedding might contribute to disease pathogenesis (40).

Modulation of ACE2 expression is seen in many lung diseases including acute lung injury (ALI). ALI is induced by viral and bacterial infections and by gastro-intestinal events such as diarrhea SARS infection induces ALI following binding to airway epithelial cells, it is known that as the virus binds to ACEs, the abundance on the cell surface, mRNA expression, and the enzymatic activity of ACE2 are significantly reduced due shedding/internalizing processes (41, 42). Interestingly in an animal model of SARS infection, binding of the virus to ACE2 results in decreased receptor expression and severe enhancement of acid aspiration pneumonia (43). Downregulation of ACE2 following SARS infection upregulates angiotensin (Ang) II which leads, in turn, to enhanced vessels permeability and induces lung injury (43). Importantly, ACE2 is endocytosed together with SARS-CoV, resulting in the reduction of ACE2 on cells, followed by an increase of serum Ang II (44). Severe lung inflammation itself may induce dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin pathway followed by ARDS development following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Indeed, SARS-CoV-induced ARDS in an animal model is prevented by inhibitors of angiotensin receptor type 1 (AT1R) (44).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is also implicated in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis as it modulates neutrophil infiltration in the lung by inhibiting the Ang II/AT1R axis, triggering lung fibrosis (45). In addition, the expression of Ang 1–7, an ACE2-mediated anti-inflammatory metabolite of Ang II, is dysregulated in asthma suggesting a role in asthma pathogenesis (5, 46). In addition, the expression of ACE2 is down-regulated by the asthma-associated cytokine IL-13 which may account for the lower expression of ACE2 in nasal epithelial cells of asthmatic subjects (47).

Human ACE2 is the receptor for SARS- CoV (48) as well as for SARS-CoV-2 (3, 49). The binding of the SARS-CoV-2 viral S protein appears not to be as strong as that seen with the SARS virus (3). However, other studies suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) exhibits a significantly higher binding affinity for ACE2 than SARS-CoV RBD (50). Furthermore, additional reports suggest that receptors such as dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4 or CD26), which are involved in SARS and MERS infection, may also be important in SARS-CoV-2 infection (51–54).

Immunopathology of COVID-19 Disease

The pathogenesis of COVID-19 is not defined but reports from many countries indicate that the virus has the same mechanism by which it enters or invades host cells as SARS-COV. The origin of SARS-CoV-2 is not well-established, however, it is established that bats are the source of related viruses and that human to human transmission plays a critical role in its pathogenesis (1, 49, 55, 56). After entering into target cells following Spike protein association with its receptor (57), viral RNA is encapsulated and polyadenylated, and encodes various structural and non-structural polypeptide genes. These polyproteins are cleaved by proteases that exhibit chymotrypsin-like activity (58, 59). Although transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) is the major protease associated with CoV activation and has been linked to SARS-CoV-2 activation, recent evidence from single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis shows that ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are not expressed in the same cell (30) suggesting the involvement of other proteases such as cathepsin B and L in this process.

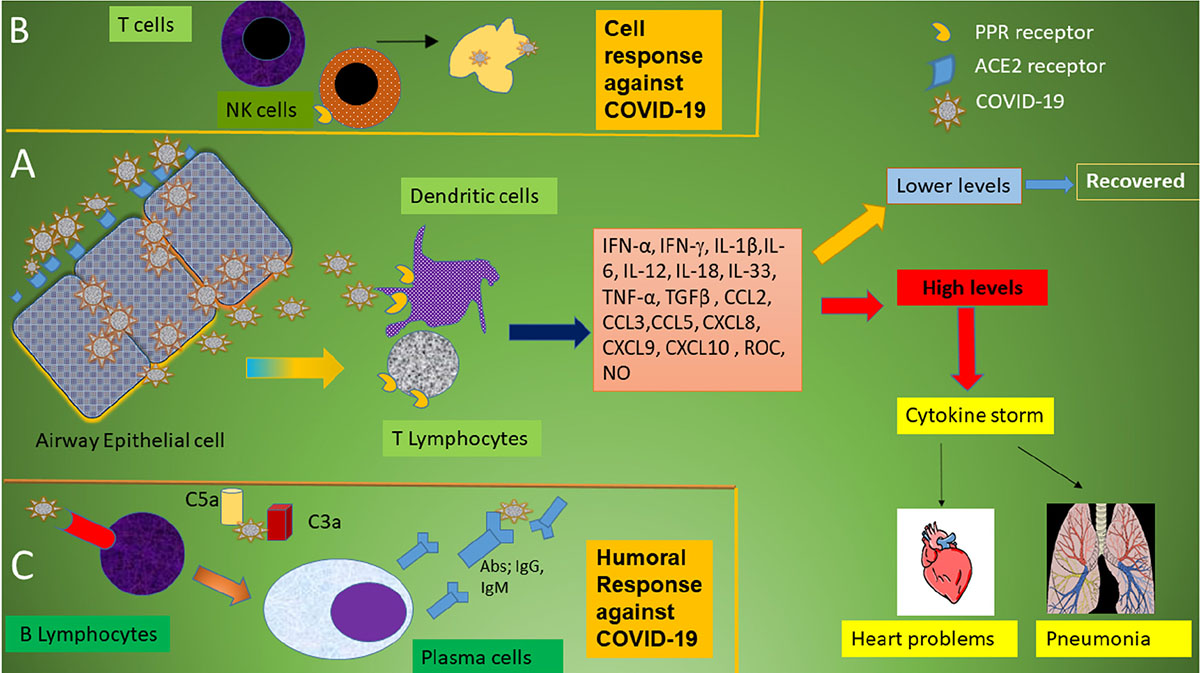

In general, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize invading pathogens including viruses (60). Viruses elicit several key host immune responses such as increasing the release of inflammatory factors, induction and maturation of dendritic cells (DCs) and increasing the synthesis of type I interferons (IFNs), which are important in limiting viral spread (60). Both the innate and acquired immune response are activated by SARS-CoV-2. CD4 + T cells stimulate B cells to produce virus-specific antibodies including immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM and CD8 + T cells directly kill virus-infected cells (Figure 1). T helper cells produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators to help the other immune cells. SARS-CoV-2 can block the host immune defense by suppressing T cell functions by inducing their programmed cell death e.g., by apoptosis. Furthermore, the host production of complement factors such as C3a and C5a and antibodies are critical in combating the viral infection (Figure 1) (61–64).

Figure 1. Schematic immune responses to CoVs. (A) When the SARS-CoV-2 virus invades the host, it is first recognized by the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) 2 receptor present on respiratory epithelial cells allowing viral entry. Following viral replication within the cells, the virus is released where it is met by the host’s innate immune system. T lymphocytes and dendritic cells are activated through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including C-type lectin-like receptors, Toll-like receptor (TLR), NOD-like receptor (NLR), and RIG-I-like receptor (RLR). The virus induces the expression of numerous inflammatory factors, maturation of dendritic cells, and the synthesis of type I interferons (IFNs) which limits the viral spread and accelerates macrophage phagocytosis of viral antigens resulting in clinical recovery. However, the N protein of SARS-CoV can help the virus escape from the immune responses and overreaction of the immune system generates high levels of inflammatory mediators and free radicals. These induce severe local damage to the lungs and other organs, and, in the worst scenario, multi-organ failure and even death. (B) The adaptive immune response joins the fight against the virus. T lymphocytes including CD4 + and CD8 + T cells play an important role in this defense. CD4 + T cells stimulate B cells to produce virus-specific antibodies whilst CD8 + T cells are able to directly kill virus-infected cells. T helper cells produce pro-inflammatory cytokines to help the defending cells. However, SARS-CoV-2 can inhibit T cells by inducing programmed cell death (apoptosis). (C) Humoral immunity including complement factors such as C3a and C5a and specific B cell-derived antibodies are also essential in combating SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Viral-Track is a novel computational approach that screens scRNA-seq data for viral RNAs (65). This approach identified a major change in the bronchoalveolar lavage immune cell landscape during severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Interestingly, Viral–Track identified co-infection of monocytes with human metapneumovirus following dampening of the IFN response.

The pathogenesis of COVID-19 is therefore as much a result of an abnormal host response or overreaction of the immune system in some patients with unknown etiology. This results in the local production of extremely high levels of a large number of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and free radicals locally that cause severe damage to the lungs and other organs. In the worst-case scenario, systemic overspill results in multi-organ failure and even death (66, 67). Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is the main death cause in COVID-19 (1). However, the precise reason for this being the common immunopathological event for SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV infections is unclear although it probably involves the generation of a cytokine storm (68). COVID-19 infection induces pneumonia which is characterized primarily by fever, cough, dyspnea, and bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging (1, 23, 69). Edema and prominent proteinaceous exudates, vascular congestion, and inflammatory clusters with fibrinoid material and multinucleated giant cells has also been reported in lungs of COVID-19 infected patients (70).

Overall, the transcriptional footprint of SARS-CoV-2 infection is distinct from other highly pathogenic coronaviruses and common respiratory viruses such as IAV, HPIV3, and RSV. It is noteworthy that, despite a reduced IFN-I and -III response to SARS-CoV-2, recent studies show a consistent chemokine signature (71).

Immune Response Against Coronavirus

In patients with COVID-19, the white blood cell count can vary between leukopenia, leukocytosis, and lymphopenia, although lymphopenia appears to be more common (1, 72). Importantly, the lymphocyte count is associated with increased disease severity in COVID-19 (73, 74). Lymphopenia and lower lymphocyte counts indicated a poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients (75, 73). ICU patients suffering from COVID-19 have lymphocyte counts of 800 cells/μl and a reduced chance for survival (23). The etiology and mechanisms of lymphopenia in COVID-19 patients is unknown but SARS-like viral particles and SARS-CoV RNA has been detected in T cells suggesting a direct effect of SARS virus on T cells potentially through apoptosis (74, 75, 76).

The role of DCs in the host defense against COVID-19 unclear. During infection with SARS-CoV, antigen-presenting cell (APC) function is altered and impaired DC migration results in reduced priming of T cells. This will lead to a fewer number of virus-specific T cells within the lungs (77, 78). After initial infection with virus, lung resident respiratory DCs (rDCs) seek out the invading pathogen or antigens from infected epithelial cells, and when activated, process antigen and migrate to the draining (mediastinal and cervical) lymph nodes (DLN). Once in the DLNs, rDCs present the processed antigen in the form of MHC/peptide complex to naïve circulating T cells. Engagement of the T cell receptor (TCR) with peptide-MHC complex and additional co-stimulatory signals induce T cell activation, vigorous proliferation and migration to the site of infection (79, 80).

Cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTLs) and natural killer (NK) cells are important for the control of viral infection, and the functional exhaustion of cytotoxic lymphocytesis may increase the severity of diseases. In patients with COVID-19, the total number of NK and CTLs are decreased which is in parallel with exhaustion of their function and upregulation of NK inhibitory receptor CD94/NK group 2 member A (NKG2A) (81). After successful recovery of COVID-19 patients, the number of NK and CD8+ T cells was restored with reduced expression of NKG2A. Furthermore, there is a lower percentage of CD107a + NK, IFN-γ+ NK, IL-2+ NK, and TNF-α+ NK cells in COVID-19 patients (81).

As indicated above, increased T cell apoptosis occurs in MERS infected patients (82, 83) and it is likely that this also happens in COVID-19 patients. Interestingly, the decreased number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients possess high proportions of HLA-DR (CD4 3.47%) and CD38 (CD8 39.4%) double-positive cells indicating highly activated cells (68). In addition, there was impaired activation of CD4 and CD8 cells evidenced by the appearance of CD25, CD28, and CD69 expression on these T cell subsets (84, 85). These factors may together account for the delayed development of the adaptive immune response and prolonged virus clearance in severe human SARS-CoV infection (86).

Decreased numbers of T cells strongly correlated with the severity of the acute phase of SARS disease in humans (87, 88). Both the S and N proteins of SARS-CoV contain immunogenic epitopes that are recognized by CD4 and CD8 T cells. Viral S protein induce neutralizing antibodies and immunization with vaccines encoding the virus N-protein able to induce eosinophilic response in animals (89). In order to produce neutralizing antibodies, it is important that the viral antigen is recognized by APC as these subsequently stimulate the body’s humoral immunity via virus-specific B and plasma cells (Figure 1). In SARS, IgM and IgG are important antibodies and the IgM antibody was detected in patient’s blood 3–6 days after infection and IgG could be detected after 8 days (90, 91). The SARS-specific IgM antibodies disappeared by the end of week 12, whilst the IgG antibody can last for a long time. This suggests that generation of IgG antibodies may be essential to provide a longer term protective role (92).

Understanding the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is crucial for vaccine development. HLA class I and II epitope pools have been used to detect CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 100 and 70% of convalescent COVID patients (93). The CD4+ responses to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein correlated with the magnitude of antiviral immunoglobulin titers although T cell responses were also found against M, N, and open viral proteins. Intriguingly, 40–60% of non-SARS-CoV-2 exposed individuals also possessed CD4 + cell responses against SARS-CoV-2 indicating a degree of cross-reactivity between CoVs (93).

In addition to cell-mediated and humoral-mediated defense by the immune system, pro-inflammatory cytokine release also helps against COVID-19 infection. Effector cytokines such as IFN-γ directly inhibit viral replication and enhance antigen presentation (94). However, it has been postulated that SARS-CoV-2, due to the secretion of a novel short protein encoded by orf3b, inhibits the expression of IFNβ and enhances viral pathogenicity (95). Chemokines produced by activated T cells recruit more innate and adaptive cells to control the pathogen burden. Cytotoxic molecules such as granzyme B directly kill infected epithelial cells and help eliminate the pathogen (96–99). One of the main mechanisms for ARDS induced by SARS-CoV-2 is the cytokine storm, the deadly uncontrolled systemic inflammatory response resulting from the release of large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines (100).

Besides lymphocytes, other innate immune cells also play a role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. For example, neutrophils and neutrophil-associated cytokines such as CXCL2 and CXCL8 are elevated in the blood and serum of COVID-19 patients (101). This may have prognostic value for identifying individuals at risk for developing severe disease.

The cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) is the result of an immune system running wild. In this condition the regulation of immune cells is often defective, resulting in the increased production of inflammatory proteins that can lead to organ failure and death. Among these inflammatory mediators released by immune effector cells are the cytokines IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-18, IL-33, TNF-α, and transforming growth factor (TGF)β and chemokines such as CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL8, CXCL9, and CXCL10 (1, 66, 86, 102). Early clinical (fever, confusion) and laboratory (blood hyperferritinemia, lymphopenia, prolonged prothrombin time, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, elevated IL-6, elevated C-reactive protein, elevated soluble CD25) results from critically ill COVID-19 patients suggest the presence of a CSS causing ARDS and multi-organ failure (23, 72, 103) as seen with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infection (68).

Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH) is an under-recognized, hyperinflammatory syndrome which is accompanied by a fulminant and fatal hyper cytokinaemia with multi-organ failure which has been reported following viral infections (104) and occurs in 3.7–4⋅3% of sepsis cases (105). A cytokine profile resembling sHLH is associated with COVID-19 disease severity, characterized by increased IL-2, IL-7, GCSF, IP-10, MCP-1, and MIP-α (1). All patients with severe COVID-19 should be screened for hyperinflammation such as increased ferritin, decreased platelet counts and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (106) to identify the subgroup of patients for whom immunosuppression could improve mortality. Therapeutic options include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, selective cytokine blockade (e.g., anakinra or tocilizumab) and JAK inhibition (107–111) and the results are eagerly awaited.

Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is an immunoregulatory cytokine with a pivotal role in initiation and perpetuation of many inflammatory diseases. GM-CSF links T-cell-driven acute pulmonary inflammation with an autocrine, self-amplifying cytokine loop that leads to monocyte and macrophage activation. This loop has been targeted in CSS and in chronic inflammatory disorders. Importantly, the expansion of GM-CSF-expressing CD4+ T cells (Th1), CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, and B cells are associated with disease severity in COVID-19 patients (112).

It is plausible that GM-CSF serves as an integral link between the severe pulmonary syndrome-initiating capacity of pathogenic CD4+ Th1 cells (GM-CSF+ IFNγ+) with the inflammatory signature of monocytes (CD14 + CD16 + with high expression of IL-6) (113). The potential risks associated with inhibition of GM-CSF in the context of viral infection and the challenges of doing clinical trials in this setting, highlight the fact that the mechanism(s) of induction of the cytokine storm are not well understood and that unknown genetic factors might be playing a role.

The reason for the resistance of children to COVID-19 is also unclear. However, it seems that their immune reactivity is lower than in adults and that although infants are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection the severity of the disease is generally low (114). In addition, other reports have hypothesized that the lower risk of infection among children is due to differential expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) which increases its gene expression within nasal epithelial with age (115).

A genetic predisposition to infectious viral disease has been ascribed to young and healthy adults who succumb to SARS-CoV-2 infection with resultant overt symptoms of COVID-19. However, there is limited evidence available as yet to delineate any specific genetic markers. Dementia has been associated with an enhanced risk of COVID-19 susceptibility and higher mortality in United Kingdom patients. The apolipoprotein E (ApoE) e4 genotype is associated with an increased risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Interestingly, within the United Kingdom Biobank, ApoE e4e4 homozygotes were 2.3–4.0-fold more likely to be COVID-19 test positives (OR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.65 to 3.24) and may relate to co-expression of ApoE e4 and ACE2 within type 2 alveolar epithelial cells (116). The risks for COVID-19 mortality were not associated with chronological age or age-related comorbidities. Further studies are needed to validate these results in another cohort and to understand the mechanisms linking ApoE genotypes to COVID-19 severity.

Furthermore, there is a global effort to define the human genetics of protective immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection (117). The goal is to compare extremes of SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility in young individuals with very severe disease and subjects with no infection despite high viral exposure.

The presence of metabolic balance syndrome/obesity, and particularly its complications, such as diabetes and hypertension, is associated with an increased propensity to develop a more serious illness, requiring hospital admission and probably invasive ventilation (111). Furthermore, patients with previous cardiovascular metabolic diseases also have a greater risk of developing severe disease highlighting the fact that the presence of comorbidities greatly affects the prognosis of the COVID-19 (118). Whether there is a genetic link to this increased risk in Caucasians is unknown but such a link is present between COVID-19 and ACE2 polymorphisms in disorders such as diabetic mellitus, cardiac diseases in Asian populations (119, 120).

In conclusion, the host immune response is the critical factor in driving COVID-19 and analysis of this response may provide a clearer picture as to how the host response impacts upon the disease severity in some individuals while most infected people only show mild symptoms or no symptoms at all. Early analysis of blood samples using scRNA-seq has revealed some interesting features (121). These include a varied IFN-stimulated response and HLA class II downregulation. Interestingly, in subjects with acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation a novel B cell-derived granulocyte population was identified. Importantly, circulating leukocytes do not express high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines suggesting that the COVID-19 cytokine storm is driven by cells within the lung.

Thus, the study of the host immune response from acute and convalescent individuals will provide molecular insights into mechanisms by which we may enable protection and long-term immune memory and enable the design of prophylactic and therapeutic measures to overcome future outbreaks of similar coronaviruses.

Author Contributions

EM wrote the original manuscript. PT, MV, GF, and IA revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

IA was supported by the EPSRC (EP/T003189/1), the UK MRC (MR/T010371/1), and by the Wellcome Trust (208340/Z/17/Z).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^ https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- ^ https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-similarities-and-differences-covid-19-and-influenza

References

1. Huang, C, Wang, Y, Li, X, Ren, L, Zhao, J, Hu, Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. (2020) 15:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

3. Lu, R, Zhao, X, Li, J, Niu, P, Yang, B, Wu, H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. (2020) 395:565–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8

4. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control data Geographical distribution of 2019- nCov cases. (2019). Available online at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases (accessed April 20, 2020).

5. Zheng, J. SARS-CoV-2: an emerging coronavirus that causes a global threat. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1678–85. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45053

6. WHO. Update WHO Report 2020. (2019) Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed April 20, 2020).

7. WHO. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report–52. (2019) Geneva: World Health Organization.

8. Wit, DE, Doremalen, VN, Falzarano, D, and Munster, JV. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2016) 14:523–34. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81

9. Siddell, S, Ziebuhr, J, and Snijder, EJ. Coronaviruses, toroviruses, and arteriviruses. Topley & Wilson’s microbiology and microbial infections. Hodder Arnold Lond. (2005) 1:823–56.

10. Su, S, Wong, G, Shi, W, Liu, J, Lai, KCA, Zhou, J, et al. Epidemiology, Genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. (2016) 24:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003

11. Weiss, SR, and Navas-Martin, S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. (2005) 69:635–64. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005

12. Perlman, S, and Netland, J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2009) 7:439–50. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2147

13. Yin, Y, and Wunderink, RR. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology. (2018) 23:130–7. doi: 10.1111/resp.13196

14. Peiris, J, Lai, ST, Poon, LLM, Guan, Y, Yam, LYC, Lim, W, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. (2003) 361:1319–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2

15. Lim, YX, Ng, YL, Tam, JP, and Liu, DX. Human coronaviruses: a review of virus−host interactions. Diseases. (2016) 4:26. doi: 10.3390/diseases40300262

16. Chan, KH, Cheng, VCC, Woo, PCY, Lau, SKP, Poon, LLM, Guan, Y, et al. Serological responses in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection and cross−reactivity with human coronaviruses 229E, OC43, and NL63. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. (2005) 12:1317–21. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.11.1317-1321.2005

17. Gill, EP, Dominguez, EA, Greenberg, SB, Atmar, RL, Hogue, BG, Baxter, BD, et al. Development and application of an enzyme immunoassay for coronavirus OC43 antibody in acute respiratory illness. J Clin Microbiol. (1994) 32:2372–76. doi: 10.1128/JCM.32.10.2372-2376.1994

18. Chan, CM, Tse, H, Wong, SSY, Woo, PCY, Lau, SKP, Chen, L, et al. Examination of seroprevalence of coronavirus HKU1 infection with S protein−based ELISA and neutralization assay against viral spike pseudotyped virus. J Clin Virol. (2009) 45:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.02.011

19. Dijkman, R, Jebbink, MF, El Idrissi, NB, Pyrc, K, Müller, MA, Taco, W, et al. Human coronavirus NL63and 229E seroconversion in children. J Clin Microbiol. (2008) 46:2368–237. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00533-08

20. Gorse, GJ, Donovan, MM, Patel, GB, Balasubramanian, S, and Lusk, RH. Coronavirus and other respiratory illnesses comparing older with younger adults. Am J Med. (2015) 128:1251.e11–e20 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.05.034

21. Gorse, GJ, O’Connor, TZ, Hall, SL, Vitale, JN, and Nichol, KL. Human coronaviruses and acute respiratory illnesses in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis. (2009) 199:847–57. doi: 10.1086/597122

22. Walsh, EE, Shin, JH, and Falsey, AR. Clinical impact of human coronaviruses229E and OC43 infection in diverse populations. J Infect Dis. (2013) 208:1634–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit393

23. Wang, D, Hu, B, Hu, C, Zhu, F, Liu, X, Zhang, J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. (2020) 323:1061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585

24. Liu, XD, Liang, QJ, and Fung, ST. Human Coronavirus-229E, -OC43, -NL63, and -HKU1. Refer Mod Life Sci. (2020). doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.21501-X

25. Zaki, AM, van Boheemen, S, Bestebroer, TM, Osterhaus, AD, and Fouchier, RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. (2012) 367:1814–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721

26. Tikellis, C, and Thomas, MC. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a key modulator of the renin angiotensin system in health and disease. Int J Pept. (2012) 2012:256294. doi: 10.1155/2012/256294

27. Donoghue, M, Hsieh, F, Baronas, E, Godbout, K, Gosselin, M, Stagliano, N, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res. (2000) 7:e1–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.5.e1

28. Vickers, C, Hales, P, Kaushik, V, Dick, L, Gavin, G, Tang, J, et al. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. (2002) 277:14838–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200

29. Yang, XH, Deng, W, Tong, Z, Liu, YX, Zhang, LF, Zhu, H, et al. Mice transgenic for human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 provide a model for SARS coronavirus infection. Comp Med. (2007) 57:450–9.

30. Sungnak, W, Huang, N, Bécavin, C, Berg, M, Queen, R, Litvinukova, M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med. (2020) 26:681–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6

31. Imai, Y, Kuba, K, Rao, S, Huan, Y, Guo, F, Guan, B, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. (2005) 436:112–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03712

32. Hoffmann, M, Kleine-Weber, H, Schroeder, S, Kruger, N, Herrler, T, Erichse, S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. (2020) 181:271–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052

33. Xu, X, Chen, P, Wang, J, Feng, J, Zhou, H, Li, X, et al. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Life Sci. (2020) 63:457–60. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5

34. Waters, CM, MacKinnon, AC, Cummings, J, Tufail-Hanif, U, Jodrell, D, Haslett, C, et al. Increased gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) receptor expression in tumour cells confers sensitivity to [Arg6,D-Trp7,9,NmePhe8]-substance P (6-11)-induced growth inhibition. Br J Cancer. (2003) 88:1808–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600957

35. Jia, HP, Look, DC, Tan, P, Shi, L, Hickey, M, Gakhar, L, et al. Ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in human airway epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. (2009) 297:L84–96. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2009

36. Lambert, DW, Yarski, M, Warner, FJ, Thornhill, P, Parkin, ET, Smith, AI, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha convertase (ADAM17) mediates regulated ectodomain shedding of the severe-acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2). J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:30113–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505111200

37. Murakami, M, Kamimura, D, and Hirano, T. Pleiotropy and specificity: insights from the interleukin 6 family of cytokines. Immunity. (2019) 50:812–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.027

38. Spinelli, FR, Conti, F, and Gadina, M. HiJAKing SARS-CoV-2? The potential role of JAK inhibitors in the management of COVID-19. Sci Immunol. (2020) 5:eabc5367. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc5367

39. Heurich, A, Hofmann-Winkler, H, Gierer, A, Liepold, T, Jahn, O, and Pöhlman, S. TMPRSS2 and ADAM17 Cleave ACE2 differentially and only proteolysis by TMPRSS2 augments entry driven by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J Virol. (2014) 88:1293–307. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02202-13

40. Alhenc-Gelas, F, and Drueke, BT. Blockade of SARS-CoV-2 infection by recombinant soluble ACE2. Kidney Int. (2020) 97:1091–3. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.009

41. Glowacka, I, Bertram, S, Herzog, P, Pfefferle, S, Steffen, I, Muench, MO, et al. Differential downregulation of ACE2 by the spike proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and human coronavirus NL63. J Virol. (2010) 84:1198–205. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01248-09

42. Dijkman, R, Jebbink, MF, Deijs, M, Milewska, A, Pyrc, K, Buelow, E, et al. Replication-dependent downregulation of cellular angiotensin- converting enzyme 2 protein expression by human coronavirus NL63. J Gen Virol. (2012) 93:1924–9. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043919-0

43. Kuba, K, Imai, Y, Rao, S, Gao, H, Guo, F, Guan, B, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. (2005) 11:875–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1267

44. Gheblawi, M, Wang, K, Viveiros, A, Nguyen, Q, Zhong, J, Turner, JA, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circ Res. (2020) 126:317015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015

45. Magalhaes, GS, Rodrigues-Machado, MG, Motta-Santos, D, Silva, AR, Caliari, MV, Prata, LO, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) attenuates airway remodelling and hyperresponsiveness in a model of chronic allergic lung inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. (2015) 172:2330–42. doi: 10.1111/bph.13057

46. El-Hashim, AZ, Renno, WM, Raghupathy, R, Abduo, HT, Akhtar, S, and Benter, IF. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits allergic inflammation, via the MAS1 receptor, through suppression of ERK1/2- and NF-kappaB-dependent pathways. Br J Pharmacol. (2012) 166:1964–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01905.x

47. Jackson, DJ, Busse, WW, Bacharier, LB, Kattan, M, O’Connor, GT, Wood, RA, et al. Association of respiratory allergy, asthma and expression of the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor, ACE2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2020) 146:203–6.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.009

48. Li, W, Moore, MJ, Vasilieva, N, Sui, J, Wong, SW, Berne, MA, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. (2003) 426:450–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02145

49. Wan, Y, Shang, J, Graham, R, Baric, RS, and Li, F. Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS. J Virol. (2020) 94:7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20

50. Tai, W, He, L, Zhang, X, Pu, J, Voronin, D, Jiang, S, et al. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol. (2020) 17:613–20. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4

51. Dong, N, Yang, X, Ye, L, Chen, K, Chan, EW-C, Yang, M, et al. Genomic and protein structure modelling analysis depicts the origin and infectivity of 2019-nCoV, a new coronavirus which caused a pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, China. bioRxiv. (2020). PMID[Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2020.01.20.913368

52. Raj, VS, Mou, H, Smits, SL, Dekkers, WHD, Müller, AM, Dijkman, R, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. (2013) 495:251–4. doi: 10.1038/nature12005

53. Pinheiro, MM, Stoppa, CL, Valduga, CJ, Okuyama, CE, Gorjão, R, Pereira, RMS, et al. Sitagliptin inhibits human lymphocyte proliferation and Th1/Th17 differentiation in vitro. Eur J Pharm Sci. (2017) 100:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.12.040

54. Sheikh, V, Zamani, A, Mahabadi-Ashtiyani, E, Tarokhian, H, Borzouei, S, and Alahgholi-Hajibehzad, M. Decreased regulatory function of CD4+ CD25+ CD45RA+ T cells and impaired IL-2 signalling pathway in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Scand J Immunol. (2018) 88:e12711. doi: 10.1111/sji.12711

55. Jia, HP, Look, DC, Shi, L, Hickey, M, Pewe, L, Netland, J, et al. ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J Virol. (2005) 79:14614–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005

56. Zhou, P, Yang, XL, Wang, XG, Hu, B, Zhang, L, Zhang, W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. (2020) 579:270–3.

57. Tortorici, MA, and Veesler, D. Structural insights into coronavirus entry. Adv Virus Res. (2019) 105:93–116. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2019.08.002

58. Coronavirinae. (2019). Available online at: https://viralzone.expasy.org/785 (accessed February 5, 2019).

59. Lambeir, AM, Durinx, C, Scharpe, S, and De Meester, I. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV from bench to bedside: an update on structural properties, functions, and clinical aspects of the enzyme DPP IV. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. (2003) 40:209–94. doi: 10.1080/713609354

60. Ben Addi, A, Lefort, A, Hua, X, Libert, F, Communi, D, Ledent, C, et al. Modulation of murine dendritic cell function by adenine nucleotides and adenosine: involvement of the A(2B) receptor. Eur J Immunol. (2008) 38:1610–20. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737781

61. Lu, X, Pan, J, Tao, J, and Guo, D. SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein antagonizes IFN-beta response by targeting initial step of IFN-beta induction pathway, and its C-terminal region is critical for the antagonism. Virus Genes. (2011) 42:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0544-x

62. Mathern, DR, and Heeger, PS. Molecules great and small: the complement system. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2015) 10:1636–50. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06230614

63. Traggiai, E, Becker, S, Subbarao, K, Kolesnikova, L, Uematsu, Y, Gismondo, MR, et al. An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nat Med. (2004) 10:871–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1080

64. Niu, P, Zhang, S, Zhou, P, Huang, B, Deng, Y, Qin, K, et al. Ultrapotent human neutralizing antibody repertoires against middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus from a recovered patient. J Infect Dis. (2018) 218:1249–60. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy311

65. Bost, P, Giladi, A, Liu, Y, Bendjelal, Y, Xu, G, David, EA, et al. Host-Viral infection maps reveal signatures of severe COVID-19 patients. Cell. (2020) 181:1475–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.006

66. Channappanavar, R, and Perlman, S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol. (2017) 39:529–39. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x

67. Collange, O, Tacquard, C, Delabranche, X, Leonard-Lorant, I, Ohana, M, Onea, M, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019: associated multiple organ damage. Open Forum Infect Dis. (2020) 7:ofaa249. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa249

68. Xu, Z, Shi, L, Wang, Y, Zhang, J, Huang, L, Zhang, C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Resp Med. (2020) 8:420–2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X

69. Guan, WJ, Ni, ZY, Hu, Y, Liang, WH, Ou, CQ, He, JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. (2020) 30:1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

70. Tian, S, Hu, W, Niu, L, Liu, H, Xu, H, and Xiao, YS. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. (2020) 15:700–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010

71. Blanco-Melo, D, Nilsson-Payant, EB, Liu, CW, Uhl, S, Hoagland, D, Møller, R, et al. Imbalance host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. (2020) 181:1036–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026

72. Chen, N, Zhou, M, Dong, X, Qu, J, Gong, F, Han, Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. (2020) 395:507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7

73. Yang, X, Yu, Y, Xu, J, Shu, H, Xia, J, Liu, H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:475–81. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5

74. Ruan, Q, Yang, K, Wang, W, Jiang, L, and Song, J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:846–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x

75. Liu, J, Li, S, Liu, J, Liang, B, Wang, X, Wang, H, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. (2020) 55:102763. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763

76. Gu, J, Gong, E, Zhang, B, Zheng, J, Gao, Z, Zhong, Y, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. (2005) 202:415–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828

77. Zhao, J, Zhao, J, Legge, K, and Perlman, S. Age-related increases in PGD(2) expression impair respiratory DC migration, resulting in diminished T cell responses upon respiratory virus infection in mice. J Clin Investigat. (2011) 121:4921–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI59777

78. Yoshikawa, T, Hill, T, Li, K, Peters, CJ, and Tseng, CT. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus-induced lung epithelial cytokines exacerbate SARS pathogenesis by modulating intrinsic functions of monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells. J Virol. (2009) 83:3039–48. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01792-08

79. Belz, GT, Smith, CM, Kleinert, L, Reading, P, Brooks, A, Shortman, K, et al. Distinct migrating and nonmigrating dendritic cell populations are involved in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation after lung infection with virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2004) 101:8670–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402644101

80. Larsson, M, Messmer, D, Somersan, S, Fonteneau, JF, Donahoe, SM, Lee, M, et al. Requirement of mature dendritic cells for efficient activation of influenza A-specific memory CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. (2000) 165:1182–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1182

81. Norbury, CC, Malide, D, Gibbs, JS, Bennink, JR, and Yewdell, JW. Visualizing priming of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by infected dendritic cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. (2002) 3:265–71. doi: 10.1038/ni762

82. Zheng, M, Gao, Y, Wang, G, Song, G, Liu, S, and Sun, D. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytesin COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. (2020) 17:533–5. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0402-2

83. Chu, H, Zhou, J, Wong, BH, Li, C, Chan, JF, Cheng, ZS, et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus Efficiently infects human primary T lymphocytes and activates the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. J Infect Dis. (2020) 213:904–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv380

84. Cai, C, Zeng, X, Ou, AH, Huang, Y, and Zhang, X. [Study on T cell subsets and their activated molecules from the convalescent SARS patients during two follow-up surveys]. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi Chinese J Cell Mol Immunol. (2004) 20:322–4.

85. Yu, XY, Zhang, YC, Han, CW, Wang, P, Xue, XJ, and Cong, YL. [Change of T lymphocyte and its activated subsets in SARS patients]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao Acta Acad Med Sin. (2003) 25:542–6.

86. Cameron, MJ, Bermejo-Martin, JF, Danesh, A, Muller, MP, and Kelvin, DJ. Human immunopathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Virus Res. (2008) 133:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.014

87. Li, T, Qiu, Z, Zhang, L, Han, Y, He, W, Liu, Z, et al. Significant changes of peripheral T lymphocyte subsets in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis. (2004) 189:648–51. doi: 10.1086/381535

88. Li, T, Qiu, Z, Han, Y, Wang, Z, Fan, H, Lu, W, et al. Rapid loss of both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets during the acute phase of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Chinese Med J. (2003) 116:985–7.

89. Bolles, M, Deming, D, Long, K, Agnihothram, S, Whitmore, A, Ferris, M, et al. A double-inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine provides incomplete protection in mice and induces increased eosinophilic proinflammatory pulmonary response upon challenge. J Virol. (2011) 85:12201–15. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06048-11

90. Lee, HK, Lee, BH, Seok, SH, Baek, WM, Lee, YH, Kim, JD, et al. Production of specific antibodies against SARS-coronavirus nucleocapsid protein without cross reactivity with human coronaviruses 229E and OC43. J Vet Sci. (2010) 11:165–7. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2010.11.2.165

91. Zhuoyue, W, Xin, Z, and Xinge, Y. IFA in testing specific antibody of SARS coronavirus. South China J Prev Med. (2003) 29:36–7.

92. Li, X, Chen, A, and Xu, A. Profile of specific antibodies to the SARS-associated coronavirus. N Engl J Med. (2003) 349:508–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200307313490520

93. Grifoni, A, Weiskopf, D, Ramirez, SI, Mateus, J, Dan, JM, Rydyznski Moderbacher, C, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. (2020) 181:1489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015

94. Saha, B, Jyothi Prasanna, S, Chandrasekar, B, and Nandi, D. Gene modulation and immunoregulatory roles of interferon gamma. Cytokine. (2010) 50:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.11.021

95. Chan, JF, Kok, KH, Zhu, Z, Chu, KK, Yuan, TS, Yuen, KY, et al. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microb Infect. (2020) 9:221–36. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902

96. Roman, E, Miller, E, Harmsen, A, Wiley, J, Von Andrian, UH, Huston, G, et al. CD4 effector T cell subsets in the response to influenza: heterogeneity, migration, and function. J Exp Med. (2002) 196:957–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021052

97. Swain, SL, Agrewala, JN, Brown, DM, and Roman, E. Regulation of memory CD4 T cells: generation, localization and persistence. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2002) 512:113–20. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0757-4_15

98. Cerwenka, A, Morgan, TM, and Dutton, RW. Naive, effector, and memory CD8 T cells in protection against pulmonary influenza virus infection: homing properties rather than initial frequencies are crucial. J Immunol. (1999) 163:5535–43.

99. Cerwenka, A, Morgan, TM, Harmsen, AG, and Dutton, RW. Migration kinetics and final destination of type 1 and type 2 CD8 effector cells predict protection against pulmonary virus infection. J Exp Med. (1999) 189:423–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.423

100. Zhao, M. Cytokine storm and immunomodulatory therapy in COVID-19: role of chloroquine and anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibodies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. (2020) 16:105982. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105982

101. Qian, Z, Travanty, EA, Oko, L, Edeen, K, Berglund, A, Wang, J, et al. Innate immune response of human alveolar type II cells infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. (2013) 48:742–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0339OC

102. Williams, AE, and Chambers, RC. The mercurial nature of neutrophils: still an enigma in ARDS? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. (2014) 306:L217–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00311.2013

103. Lei, C, Huigo, L, Wei, L, Liu, J, Liu, K, Shang, J, et al. Analysis of clinical features of 29 patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis. (2020) 43:E005.

104. Ramos-Casals, M, Brito-Zeron, P, Lopez-Guillermo, A, Khamashta, MA, and Bosch, X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. (2014) 383:1503–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61048-X

105. Karakike, E, and Giamarellos-Bourboulis, EJ. Macrophage activation-like syndrome: a distinct entity leading to early death in sepsis. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:55. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00055

106. Fardet, L, Galicier, L, Lambotte, O, Marzac, C, Aumont, C, Chahwan, D, et al. Development and validation of the H Score, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2014) 66:2613–20. doi: 10.1002/art.38690

107. Zha, L, Li, S, Pan, L, Tefsen, B, Li, Y, French, N, et al. Corticosteroid treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Med J Aust. (2020) 9:416–20. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50577

108. Xie, Y, Cao, S, Dong, H, Li, Q, Chen, E, Zhang, W, et al. Effect of regular intravenous immunoglobulin therapy on prognosis of severe pneumonia in patients with COVID-19. J Infect. (2020) 81:318–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.044

109. Radbel, J, Narayanan, N, and Bhatt, PJ. Use of tocilizumab for COVID-19 infection-induced cytokine release syndrome: a cautionary case report. Chest. (2020) 25:24. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.024

110. Cron, RQ, and Chatham, WW. The question of whether to remain on therapy for chronic rheumatic diseases in the setting of the covid-19 pandemic. J Rheumatol. (2020) 25:jrheum.200492. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200492

111. Simonnet, A, Chetboun, M, Poissy, J, Raverdy, V, Noulette, J, Duhamel, A, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2020). doi: 10.1002/oby.22831

112. Zhou, Y, Fu, B, Zheng, X, Wang, D, Zhao, C, Qi, Y, et al. Pathogenic T cells and inflammatory monocytes incite inflammatory storm in severe COVID-19 patients. Natl Sci Rev. (2020) 13:nwaa041. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa041

113. Mehta, P, Porter, CJ, Manson, JJ, Isaacs, DJ, Openshaw, MJP, McInnes, IB, et al. Therapeutic blockade of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation: challenges and opportunities. Lancet. (2020) 16:8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30267-8

114. Dong, Y, Mo, X, Hu, Y, Qi, X, Jiang, F, Jiang, Z, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. (2020) 145:e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702

115. Bunyavanich, S, Do, A, and Vicencio, A. Nasal gene expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in children and adults. JAMA. (2020) 323:2427–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8707

116. Kuo, CL, Pilling, CL, Atkins, LJ, Masoli, HAJ, Delgado, J, Kuchel, AG, et al. APOE e4 genotype predicts severe COVID-19 in the UK Biobank community cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2020) 26:glaa131. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.07.20094409

117. Casanova, JL, and Su, CHA. Global effort to define the human genetics of protective immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell. (2020) 181:61194–9.

118. Li, B, Yang, J, Zhao, F, Zhi, L, Wang, X, Liu, L, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. (2020) 11:1–8.

119. Liu, C, Li, Y, Guan, T, Lai, Y, Shen, Y, Zeyaweiding, A, et al. ACE2 polymorphisms associated with cardiovascular risk in Uygurs with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovas Diabetol. (2018) 17:127. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0771-3

120. Fang, L, Karakiulakis, G, and Roth, M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet. (2020) 8:e21. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30116-8

Keywords: coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, IL-6, pathogenesis, cytokines storm

Citation: Mortaz E, Tabarsi P, Varahram M, Folkerts G and Adcock IM (2020) The Immune Response and Immunopathology of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 11:2037. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02037

Received: 02 May 2020; Accepted: 27 July 2020;

Published: 26 August 2020.

Edited by:

Alexis M. Kalergis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, ChileReviewed by:

Abel Viejo-Borbolla, Hannover Medical School, GermanyJianzhong Zhu, Yangzhou University, China

Copyright © 2020 Mortaz, Tabarsi, Varahram, Folkerts and Adcock. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ian M. Adcock, SWFuLkFkY29ja0BpbXBlcmlhbC5hYy51aw==

Esmaeil Mortaz

Esmaeil Mortaz Payam Tabarsi

Payam Tabarsi Mohammad Varahram

Mohammad Varahram Gert Folkerts

Gert Folkerts Ian M. Adcock

Ian M. Adcock