94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 27 November 2018

Sec. T Cell Biology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02755

This article is part of the Research Topic Inhibitory Receptors and Pathways of Lymphocytes View all 15 articles

Costimulatory and coinhibitory receptors play a key role in regulating immune responses to infection and cancer. Coinhibitory receptors include programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), and T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), which suppress immune responses. Coinhibitory receptors are highly expressed on exhausted virus-specific T cells, indicating that viruses evade host immune responses through enhanced expression of these molecules. Human retroviruses, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1), infect T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. Therefore, one needs to consider the effects of coinhibitory receptors on both uninfected effector T cells and infected target cells. Coinhibitory receptors are implicated not only in the suppression of immune responses to viruses by inhibition of effector T cells, but also in the persistence of infected cells in vivo. Here we review recent studies on coinhibitory receptors and their roles in retroviral infections such as HIV and HTLV-1.

Various viruses cause acute and chronic infections in humans. Since the host immune system functions to eliminate exogenous virus and infected cells, viruses that cause chronic infections must evade host immune surveillance by various strategies. Some viruses that cause persistent infections are also associated with viral oncogenesis; these include hepatitis C virus (HCV) (1), hepatitis B virus (HBV) (2, 3), human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) (4, 5), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (6). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) also contributes to the development of cancers (7).

Costimulatory and coinhibitory receptor molecules play a key role in regulating immune responses to infections and cancers (8). When bound by their ligands, coinhibitory receptors suppress excess immune responses. In several cancers, tumor-infiltrating T cells express coinhibitory molecules that enable the tumors to escape the host immune response. Recent studies show that antibodies that block coinhibitory receptors, called immune checkpoint blocking antibodies, enhance immune responses to various cancers and exhibit remarkable clinical efficacy in cancer treatment (9).

Both virus-specific T cells and tumor-infiltrating T cells express coinhibitory molecules, and immune checkpoint pathways play a role in maintaining an exhausted T cell phenotype characterized by impaired cytokine production and cytotoxicity (10). The attenuated responses cannot eliminate viruses. In this review, we focus on coinhibitory receptors in retroviral infections.

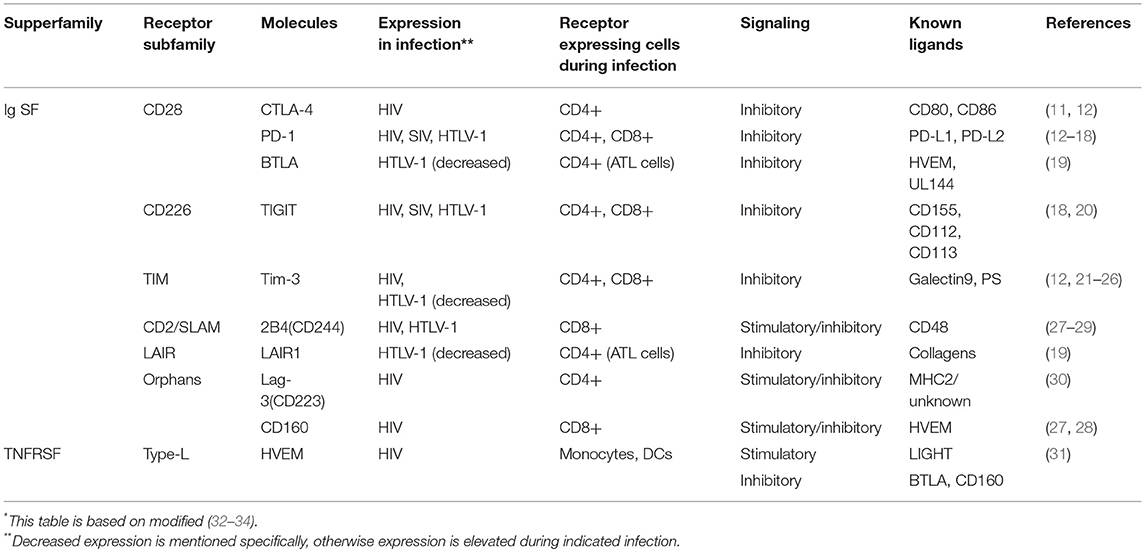

An increasing number of coinhibitory molecules and pathways have now been identified (Table 1). There are two major families of T cell cosignaling molecules: the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF), which includes the B7-CD28 subfamily, and the tumor necrosis factor superfamilies of ligands (TNFSF) and receptors (TNFRSF). The B7-CD28 subfamily includes the classic coinhibitory receptor cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) (35). B7 family molecules, such as CD80 and CD86, enhance TCR-mediated responses through binding to the co-stimulatory receptor CD28. On the other hand, CTLA-4 competes with CD28 for binding to CD80 and CD86 (36), thus playing a critical role in regulating T-cell activation and expansion (37–39). Thus, coinhibitory CD28 subfamily molecules negatively regulate T cell responses (8). Another representative molecule of this subfamily is programmed cell death 1 (PD-1: also known as Pdcd1). The IgSF also includes T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (Tim-3), T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), Lymphocyte activation gene-3 (Lag-3), and 2B4 (CD244, a member of the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) family of CD2-related receptors) (32, 40–42).

Table 1. Inhibitory Ig superfamily and TNF superfamily receptors and their stimulatory molecules expressing during retrovirus infection*.

The other major group of cosignaling molecules, members of the TNFSF and TNFRSF, elicit costimulatory and coinhibitory signals between various cells. Most TNFRSF members bind to their specific TNFSF ligands and elicit costimulatory signals; however, herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) binds to several different ligands, including both TNFSF members and IgSF members. These ligands provide both stimulatory and inhibitory signals from HVEM. Binding of HVEM to the IgSF member B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) triggers inhibitory signals (43). HVEM also binds to the IgSF member CD160 and elicits a coinhibitory signal (44). CD160 is involved in both NK cell activation and T cell exhaustion (43). Another TNFRSF member, Death receptor 6, has also been reported to be a regulatory receptor (45). Coinhibitory receptors that are expressed during retrovirus infection are shown in Table 1.

When T cells are chronically activated by viral infections, T cells tend to express coinhibitory receptors, and acquire exhausted phenotypes. Although most murine retroviruses establish chronic infection only when they infect neonatal mice, Friend virus (FV) causes acute and chronic infection even when it infects adult immunocompetent mice, suggesting that FV can evade the host immune responses and cause persistent infection (46). Regarding this, FV is similar to HIV and HTLV. As well as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection (47, 48), FV-specific effector CD8 T cells express multiple coinhibitory receptors, such as PD-1, Tim-3, Lag-3, and CTLA-4 during chronic FV infection. Those cells were shown to be dysfunctional and associated with exhaustion (49, 50). In murine retrovirus model of FV chronic infection, blocking of CTLA-4 showed augmented T cell response and decreased the viral load (51). In addition to enhanced expression of coinhibitory receptors, regulatory T (Treg) cells also increase, which is associated with inhibition of effector T cells during FV infection (49, 52, 53). Thus, combined treatment of depletion of Treg cells and blockade of coinhibitory receptors recover CD8 T cell responses to FV (52).

Although FV infection is one model of retrovirus infection, it should be pointed out that FV is a retrovirus which infects mainly erythroid precursor cells and causes erythroleukemia. The target cell type is different from that of human retroviruses, such as HIV and HTLV-1, which target immune cells including T cells. Next, we review the coinhibitory receptors and their roles in pathogenesis of human retrovirus infections, HIV and HTLV-1.

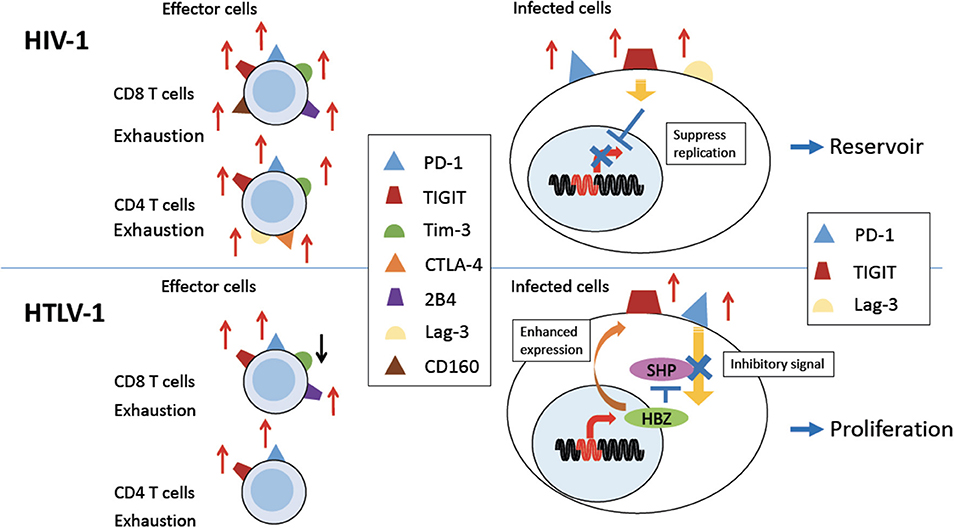

Coinhibitory receptors are also implicated in persistent infection with human retroviruses, HIV, and HTLV-1. However, one difference between these viruses and most others is that the target cells of these human retroviruses are the immune cells themselves, including T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells—cells that also express coinhibitory receptors. Moreover, inhibitory ligands are also expressed on retrovirus infected cells (54), which can cause dysfunction of effector cells through interaction with coinhibitory receptors. Therefore, we need to consider the effects of coinhibitory receptors on two types of cells: uninfected effector cells to the virus, and cells that are infected with the virus.

To established chronic infection, human retroviruses have to evade the host immune response. One mechanism is the escape mutations of epitopes that are recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL). Since viral reverse transcriptase is an error-prone DNA polymerase, vigorous viral replication generates vast number of mutations in the provirus. If the target epitope of CTL is mutated, this mutation enables the virus to escape from CTL responses. Furthermore, HIV impairs the immune function of effector cells to HIV infected cells through co-inhibitory receptors, which also helps virus to escape from immune responses (55). We are going to discuss about several co-inhibitory receptors.

PD-1 expression is upregulated on HIV-specific CD8 and CD4 T cells in humans (Figure 1, upper left). The expression of PD-1 on these cells is positively correlated with viral load and disease progression (13), suggesting that PD-1 expression allows viral replication in vivo. HIV infection also upregulates PD-L1 expression on infected cells, which impairs T-cell function through interaction with increased PD-1 on effector T cells (54). Blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway using antibodies against PD-L1 ex vivo restores the function of HIV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cells from anti-retroviral therapy naïve patients (13). Further studies investigated the effect of blocking the PD-1 pathway using an in vivo mouse model. The effect of PD-L1 blocking antibodies was analyzed in humanized mice chronically infected with HIV-1. The blockade of the PD-1 pathway decreased HIV-1 viral loads and suppressed disease progression, especially in animals with high levels of PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells (14, 15). A recent study showed that antibodies targeting BTLA and Tim-3 in combination with PD-1 antibody also enhanced HIV-specific CD8 T cells proliferation in vitro (56). These studies suggest that the blocking of these coinhibitory receptors is an effective strategy to restore the anti-virus T cell responses and suppress viral load in HIV-infected individuals. In particular, this strategy combined with “shock-and-kill” therapy and/or ART might be beneficial for control of HIV.

Figure 1. Expression of coinhibitory receptors in HIV-1 and HTLV-1 infection. Persistent HIV-1 (Upper Left) and HTLV-1 (Bottom Left) infection induces expression of various coinhibitory receptors on uninfected effector CD8 T cells, and some uninfected CD4 T cells, causing exhaustion of T cells (left). PD-1 and TIGIT and/or Lag-3 are also expressed on HIV-1 or HTLV-1 infected CD4 T cells (right). In HIV-1 infection, coinhibitory receptor expression is implicated in establishment of a viral reservoir (Upper Right). In HTLV-1 infection, expression of coinhibitory receptors is enhanced by the viral protein HBZ. Inhibitory signals from coinhibitory receptors are impaired by HBZ. Thus, infected cells are able to proliferate despite of increased expression of coinhibitory receptors (Bottom Right).

The SIV infected rhesus macaque is the in vivo model of HIV-1 infection. An in vivo experiment using rhesus macaques also showed that PD-1 blockade enhances SIV-specific CD8 T cell responses, reduced viremia, and prolonged survival of SIV-infected macaques (57, 58), especially in combination with antiretroviral therapy (ART) (31).

CTLA-4, another inhibitory receptor, is also upregulated in HIV-specific CD4 T cells, most of which co-express it with PD-1 (11) (Figure 1, upper left). CTLA-4 expression also positively correlates with disease progression. Blocking of CTLA-4 enhances HIV-specific CD4 T cell proliferation in response to HIV protein (11).

The exhaustion of HIV-specific CD8 T cells is also mediated by Tim-3 (Figure 1). The frequency of Tim-3 expressing dysfunctional T cells was elevated in HIV-1 infected individuals. In particular, Tim-3 expression was upregulated in HIV-specific CD8 T cells. Tim-3 expression was positively correlated with viral load and inversely correlated with CD4 T cell count (21). Tim-3 triggers cell death after interaction with its ligand, Galectin-9 (Gal-9) (22–24). Treg cells constitutively express Gal-9 and suppress proliferation of HIV-specific CD8 T cells with high level of Tim-3 expression (59). Furthermore, Tim-3 expressing HIV-specific CD8 T cells are defective in regard of degranulation (25). It has also been reported that PD-1, CTLA-4, and Tim-3 are co-expressed on HIV-specific CD4 T cells from untreated infected patients, and the co-expression of these three inhibitory receptors was strongly correlated with viral load (12).

TIGIT is often coexpressed with PD-1 at higher levels on HIV-specific CD8 T cells in HIV-infected patients, and this expression correlates with exhaustion of T cells and disease progression (Figure 1). TIGIT is highly expressed on intermediately differentiated memory CD8 T cells that are not fully mature effectors, which expand in HIV infection (20, 60). It has been reported that TIGIT+ cells produce less IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ and degranulate less (20). In addition, TIGIT expression on CD4 T cells is also associated with HIV viral load. As was the case for the other inhibitory receptors described above, blocking TIGIT and/or PD-L1 restores CD8 T cell responses in vitro (20).

Other inhibitory molecules are also implicated in HIV infection. HIV-specific CD8 T cells expressing PD-1 also express CD160 and 2B4 (27, 28) (Figure 1). Co-expression of these inhibitory receptors correlates with virus load and T cell responses. ART reduces the expression of these inhibitory molecules on the surfaces of HIV-specific CD8 T cells. Furthermore, blocking of the PD-1/PD-L1 and 2B4/CD48 pathways enhances the proliferation of virus-specific CD8 T cells (27). Higher expression of Lag-3 on CD4 T cells was also reported in rapid progressors of HIV infection (30) (Figure 1, upper left).

HVEM, which is a member of the TNFRSF and the ligand of CD160, is upregulated on monocytes and dendritic cells (DCs) in HIV chronically infected patients. Blocking the interaction between CD160 and HVEM also enhanced the proliferation of HIV-specific CD8 T cells (61).

So far we have discussed the effects of coinhibitory receptors on uninfected effector T cells to HIV (Figure 1, upper left). Next we need to consider the effects of these coinhibitory receptors on HIV infected cells themselves. Coinhibitory receptors suppress the proliferation and activation of infected cells (62) (Figure 1, upper right). First, PD-1 has been shown to associate with persistence of HIV in patients under ART treatment (63). The expression of the co-inhibitory receptors PD-1, TIGIT, and LAG-3, correlates with HIV-infected cells persisting in individuals treated with ART (64) (Figure 1, upper right). Thus, these studies suggest that co-inhibitory receptors play a important role in the formation of an HIV reservoir. It has been clarified that more than 95% of HIV-1 provirus in patients who receive ART are defective (65, 66). Such defective provirus does not kill infected cells since it cannot produce infectious virion. However, infected cells with defective provirus can produce viral proteins, which cause inflammation. It is likely that continuous inflammation upregulates PD-1, resulting in immune exhaustion and escape of infectious HIV-1 from host immune responses.

HTLV-1 causes adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) and inflammatory diseases including HTLV-1-asscociated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) (4, 67). The HTLV-1 bZIP factor (HBZ) gene plays a critical role in oncogenesis and inflammation. HBZ is constantly expressed in ATL cells and HTLV-1-infected cells in carriers, and furthermore, transgenic expression of HBZ induces T-cell lymphomas and systemic inflammatory diseases resembling those found in HTLV-1-infected individuals (68, 69). One prominent feature of HTLV-1 is that this virus transmits primarily through cell-to-cell contact. To facilitate its transmission, HTLV-1 increases the number of infected cells in vivo. Therefore, this virus has evolved strategies to promote the proliferation of infected cells and evade host immune surveillance. Although HTLV-1 can infect a variety of cells, it primarily infects CD4+CD45RO+CCR4+ T cells in vivo. It is thought that HTLV-1 increases this special subtype of CD4+ T cells in vivo. HBZ is thought to be critical for this special phenotype since HBZ converts infected cells to this special phenotype T cells (70).

Since HTLV-1 mainly infects CD4 T cells in vivo, we again need to consider the roles of coinhibitory receptors on two different kinds of cells: infected CD4 T cells and uninfected effector T cells (Figure 1). It has been reported that during chronic HTLV-1 infection, PD-1 expression is increased on HTLV-1-specific CD8 T cells (Figure 1) (16). At the same time, ATL cells and HTLV-1 infected CD4 T cells of HAM/TSP patients express high levels of PD-1 (17, 18). These infected cells also express high levels of TIGIT (Figure 1) (18). Interestingly, the expression of PD-1 and TIGIT is enhanced in HBZ gene-transduced T cells (18), whereas the expressions of other coinhibitory receptors, BTLA and LAIR-1, is suppressed (19). This selective enhanced expression of particular coinhibitory receptors appears to be unique to HTLV-1. Co-blocking of PD-1 and TIGIT ex vivo partially restores anti-Tax T-cell responses in some HAM/TSP patients.

Flow cytometry showed that PD-L1 expression is also upregulated in 21.7% of ATL cases (16). One possible mechanism of the upregulation of PD-L1 has been identified: 27% of ATL cases possess structural variations that commonly disrupt the 3' untranslated region of the PD-L1 gene, resulting in increased PD-L1 transcripts (71). This upregulated PD-L1 expression enables ATL cells to evade the host CTL responses by causing exhaustion of effector T cells.

HBZ-induced coinhibitory receptors on HTLV-1 infected cells likely impair anti-virus T cell responses (18). As a mechanism, high expression levels of TIGIT promote production of IL-10 from CD155 positive DCs by reverse signaling (i.e., signaling from coinhibitory receptor ligands, such as PD-L1 and/or PD-L2 for PD-1, and CD155 for TIGIT on DCs). IL-10 not only suppresses the host immune response, but also promotes proliferation of HTLV-1 infected cells and ATL cells (72). The reverse signaling reduces maturation of DCs and changes them to a suppressive phenotype (73, 74). Furthermore, TIGIT competes for the binding of CD155 with CD226, a stimulatory receptor on T cells (75). Thus, HTLV-1 induces expression of coinhibitory receptors on effector T cells not only by chronic infection resulting in exhaustion of effector T cells but also by direct effect of HBZ on HTLV-1 infected T cells (18).

Coinhibitory receptors normally inhibit the proliferation of expressing T cells through binding of their ligands (76). However, the enigma is that ATL cells and HTLV-1 infected T cells do proliferate in vivo. Coinhibitory receptors like PD-1 and TIGIT normally inhibit cell proliferation through the ITIM or ITSM domains of their cytoplasmic regions, which interact with the phosphatases SHP1 and SHP2. However, HBZ expressing cells are resistant to the growth-inhibitory effects of TIGIT. THEMIS forms complexes with Grb2 and SHP and recruits them to the ITIM or ITSM domains of the coinhibitory receptors (77). HBZ interacts with THEMIS and impairs the growth-suppressive signal through SHP (Figure 1, bottom right). Thus, HBZ induces the expression of coinhibitory receptors while it blocks their suppressive effects on the proliferation of expressing cells (19).

Mice with impaired IL-10 signaling were reported to develop autoimmune colitis, suggesting a critical role of IL-10 in regulating inflammation (78). IL-10 has various effects on many hematopoietic cells: IL-10 causes dendritic cells to downregulate stimulatory IL-12 production and expression of costimulatory molecules (78, 79). In addition, IL-10 decreases T-cell cytokine production (78). Thus, IL-10 is critical for suppressing immune responses. High levels of TIGIT induce IL-10 production, leading to a suppressed host immune response (74).

Recently, it has been reported that anti-PD-1 antibody induced rapid progression of ATL after its administration (80). It has been reported that PD-1 functions as a tumor suppressor in T-cell lymphomas (81). This is the case in some ATL cases. This finding suggests that HBZ partially hinders the suppressive effects of PD-1. Thus, the significance of coinhibitory receptors for ATL cells needs further study.

Another inhibitory receptor, 2B4 (CD244), is expressed at elevated levels on CD8 T cells in HTLV-1 infected patients and especially on HTLV-1 specific CD8 T cells. Blockade of the interaction between 2B4 and its ligand CD48 by antibody to CD48 in vitro enhances HTLV-1 specific CD8 T cell effector function measured by increased CD107a degranulation and perforin expression (29). On the other hand, Tim-3 expression is reduced on CD4 and CD8 T cells of HTLV-1 infected patients (26). This selective expression may be modulated by virus genes, such as HBZ, in order to have an advantage of virus survival.

Since exhausted T cells are also implicated in chronic viral infections as described in this review, immune checkpoint therapy could be a novel treatment for diseases associated with persistent viral infections as well as anti-tumor therapy (82). Notably for human retroviral infections, coinhibitory receptors on both effector cells and infected target cells play different roles in the pathogenesis. Coinhibitory receptors on target cells infected with HIV or HTLV-1 likely promote their survival by protecting target cells from immune responses or inhibiting viral production. Further studies are necessary to clarify the roles of coinhibitory receptors in chronic viral infections.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Dr. Linda Kingsbury for proofreading. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (JP16H05336 to MM), the Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREATE) (17cm0106306h0002 to MM), the Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (17fk0108227h0002 to MM). This study was also supported in part by the JSPS Core-to-Core Program A, Advanced Research Networks.

1. Urbani S, Amadei B, Tola D, Massari M, Schivazappa S, Missale G, et al. PD-1 expression in acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with HCV-specific CD8 exhaustion. J Virol. (2006) 80:11398–403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01177-06

2. Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. (2006) 44(Suppl. 1):S6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004

3. Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, Abubakar I, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet (2016) 388:1081–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7

4. Matsuoka M. Jeang KT. Human T-cell leukaemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infectivity and cellular transformation. Nat Rev Cancer (2007) 7:270–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc2111

5. Ishitsuka K, Tamura K. Human T-cell leukaemia virus type I and adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. (2014) 15:e517–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70202-5

6. Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med. (2000) 343:481–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008173430707

7. Yarchoan R, Tosato G, Little RF. Therapy insight: AIDS-related malignancies–The influence of antiviral therapy on pathogenesis and management. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. (2005) 2:406–15. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0253

8. Chen L. Co-inhibitory molecules of the B7–CD28 family in the control of T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. (2004) 4:336–47. doi: 10.1038/nri1349

9. Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science (2015) 348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172

10. Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol. (2003) 77:4911–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003

11. Kaufmann DE, Kavanagh DG, Pereyra F, Zaunders JJ, Mackey EW, Miura T, et al. Upregulation of CTLA-4 by HIV-specific CD4+ T cells correlates with disease progression and defines a reversible immune dysfunction. Nat Immunol. (2007) 8:1246–54. doi: 10.1038/ni1515

12. Kassu A, Marcus RA, D'Souza MB, Kelly-McKnight EA, Golden-Mason L, Akkina R, et al. Regulation of virus-specific CD4+ T cell function by multiple costimulatory receptors during chronic HIV infection. J Immunol. (2010) 185:3007–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000156

13. Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, Brown JA, Moodley ES, Reddy S, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature (2006) 443:350–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05115

14. Palmer BE, Neff CP, Lecureux J, Ehler A, Dsouza M, Remling-Mulder L, et al. In vivo blockade of the PD-1 receptor suppresses HIV-1 viral loads and improves CD4+ T cell levels in humanized mice. J Immunol. (2013) 190:211–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201108

15. Seung E, Dudek TE, Allen TM, Freeman GJ, Luster AD, Tager AM. PD-1 blockade in chronically HIV-1-infected humanized mice suppresses viral loads. PLoS ONE (2013) 8:e77780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077780

16. Kozako T, Yoshimitsu M, Fujiwara H, Masamoto I, Horai S, White Y, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 expression in human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 carriers and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patients. Leukemia (2009) 23:375–82. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.272

17. Shimauchi T, Kabashima K, Nakashima D, Sugita K, Yamada Y, Hino R, et al. Augmented expression of programmed death-1 in both neoplastic and non-neoplastic CD4+ T-cells in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Int J Cancer (2007) 121:2585–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23042

18. Yasuma K, Yasunaga J, Takemoto K, Sugata K, Mitobe Y, Takenouchi N, et al. HTLV-1 bZIP Factor impairs anti-viral immunity by inducing Co-inhibitory molecule, T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT). PLoS Pathog. (2016) 12:e1005372. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005372

19. Kinosada H, Yasunaga JI, Shimura K, Miyazato P, Onishi C, Iyoda T, et al. HTLV-1 bZIP factor enhances T-cell proliferation by impeding the suppressive signaling of co-inhibitory receptors. PLoS Pathog. (2017) 13:e1006120. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006120

20. Chew GM, Fujita T, Webb GM, Burwitz BJ, Wu HL, Reed JS, et al. TIGIT marks exhausted T cells, correlates with disease progression, and serves as a target for immune restoration in HIV and SIV infection. PLoS Pathog. (2016) 12:e1005349. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005349

21. Jones RB, Ndhlovu LC, Barbour JD, Sheth PM, Jha AR, Long BR, et al. Tim-3 expression defines a novel population of dysfunctional T cells with highly elevated frequencies in progressive HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. (2008) 205:2763–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081398

22. Zhu C, Anderson AC, Schubart A, Xiong H, Imitola J, Khoury SJ, et al. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat Immunol. (2005) 6:1245–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1271

23. Rangachari M, Zhu C, Sakuishi K, Xiao S, Karman J, Chen A, et al. Bat3 promotes T cell responses and autoimmunity by repressing Tim-3-mediated cell death and exhaustion. Nat Med. (2012) 18:1394–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.2871

24. Poonia B, Pauza CD. Levels of CD56+TIM-3- effector CD8 T cells distinguish HIV natural virus suppressors from patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e88884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088884

25. Sakhdari A, Mujib S, Vali B, Yue FY, MacParland S, Clayton K, et al. Tim-3 negatively regulates cytotoxicity in exhausted CD8+ T cells in HIV infection. PLoS ONE (2012) 7:e40146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040146

26. Abdelbary NH, Abdullah HM, Matsuzaki T, Hayashi D, Tanaka Y, Takashima H, et al. Reduced Tim-3 Expression on Human T-lymphotropic Virus Type I (HTLV-I) Tax-specific Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes in HTLV-I Infection. J Infect Dis. (2011) 203:948–59. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq153

27. Yamamoto T, Price DA, Casazza JP, Ferrari G, Nason M, Chattopadhyay PK, et al. Surface expression patterns of negative regulatory molecules identify determinants of virus-specific CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in HIV infection. Blood (2011) 117:4805–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317297

28. Buggert M, Tauriainen J, Yamamoto T, Frederiksen J, Ivarsson MA, Michaëlsson J, et al. T-bet and Eomes are differentially linked to the exhausted phenotype of CD8+ T cells in HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. (2014) 10:e1004251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004251

29. Ezinne CC, Yoshimitsu M, White Y, Arima N. HTLV-1 specific CD8+ T cell function augmented by blockade of 2B4/CD48 interaction in HTLV-1 infection. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e87631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087631

30. Rotger M, Dalmau J, Rauch A, McLaren P, Bosinger SE, Martinez R, et al. Comparative transcriptomics of extreme phenotypes of human HIV-1 infection and SIV infection in sooty mangabey and rhesus macaque. J Clin Invest. (2011) 121:2391–400. doi: 10.1172/JCI45235

31. McGary CS, Silvestri G, Paiardini M. Animal models for viral infection and cell exhaustion. Curr Opin HIV AIDS (2014) 9:492–9. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000093

32. Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. (2013) 13:227–42. doi: 10.1038/nri3405

33. Odorizzi PM, Wherry EJ. Inhibitory receptors on lymphocytes: insights from infections. J Immunol. (2012) 188:2957–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100038

34. Attanasio J, Wherry EJ. Costimulatory and coinhibitory receptor pathways in infectious disease. Immunity (2016) 44:1052–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.022

35. Schildberg FA, Klein SR, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. Coinhibitory pathways in the B7-CD28 ligand-receptor family. Immunity (2016) 44:955–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.002

36. Carreno BM, Collins M. Theb7 family ofligands anditsreceptors: new pathways for costimulation and inhibition of immune responses. Ann Rev Immunol. (2002) 20:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091101.091806

37. Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Lee KP, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science (1995) 270:985–8. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985

38. Bluestone JA. New perspectives of CD28-B7-mediated T cell costimulation. Immunity (1995) 2:555–9. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90000-4

39. Jenkins MK. The ups and downs of T cell costimulation. Immunity (1994) 1:443–6. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90086-8

40. Waggoner SN, Kumar V. Evolving role of 2B4/CD244 in T and NK cell responses during virus infection. Front Immunol. (2012) 3:377. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00377

41. Anderson AC, Joller N, Kuchroo VK. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity (2016) 44:989–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.001

42. Johnston RJ, Comps-Agrar L, Hackney J, Yu X, Huseni M, Yang Y, et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T cell effector function. Cancer Cell (2014) 26:923–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.018

43. Ward-Kavanagh LK, Lin WW, Šedý JR, Ware CF. The TNF Receptor Superfamily in Co-stimulating and Co-inhibitory Responses. Immunity (2016) 44:1005–19. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.019

44. Cai G, Freeman GJ. The CD160, BTLA, LIGHT/HVEM pathway: a bidirectional switch regulating T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. (2009) 229:244–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00783.x

45. Liu J, Na S, Glasebrook A, Fox N, Solenberg PJ, Zhang Q, et al. Enhanced CD4+ T cell proliferation and Th2 cytokine production in DR6-deficient mice. Immunity (2001) 15:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00162-5

46. Hasenkrug KJ, Chesebro B. Immunity to retroviral infection: the friend virus model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1997) 94:7811–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7811

47. Zajac AJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, Sourdive DJ, Suresh M, Altman JD, et al. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J Exp Med. (1998) 188:2205–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205

48. Blackburn SD, Shin H, Haining WN, Zou T, Workman CJ, Polley A, et al. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat Immunol. (2009) 10:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679

49. Zelinskyy G, Robertson SJ, Schimmer S, Messer RJ, Hasenkrug KJ, Dittmer U. CD8+ T-cell dysfunction due to cytolytic granule deficiency in persistent Friend retrovirus infection. J Virol. (2005) 79:10619–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10619-10626.2005

50. Takamura S, Tsuji-Kawahara S, Yagita H, Akiba H, Sakamoto M, Chikaishi T, et al. Premature terminal exhaustion of Friend virus-specific effector CD8+ T cells by rapid induction of multiple inhibitory receptors. J Immunol. (2010) 184:4696–707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903478

51. Teigler JE, Zelinskyy G, Eller MA, Bolton DL, Marovich M, Gordon AD, et al. Differential inhibitory receptor expression on T cells delineates functional capacities in chronic viral infection. J Virol. (2017) 91:e01263–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01263-17

52. Dietze KK, Zelinskyy G, Liu J, Kretzmer F, Schimmer S, Dittmer U. Combining regulatory T cell depletion and inhibitory receptor blockade improves reactivation of exhausted virus-specific CD8+ T cells and efficiently reduces chronic retroviral loads. PLoS Pathog. (2013) 9:e1003798. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003798

53. Iwashiro M, Messer RJ, Peterson KE, Stromnes IM, Sugie T, Hasenkrug KJ. Immunosuppression by CD4+ regulatory T cells induced by chronic retroviral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2001) 98:9226–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151174198

54. Akhmetzyanova I, Drabczyk M, Neff CP, Gibbert K, Dietze KK, Werner T, et al. PD-L1 expression on retrovirus-infected cells mediates immune escape from CD8+ T cell killing. PLoS Pathog. (2015) 11:e1005224. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005224

55. Letvin NL, Walker BD. Immunopathogenesis and immunotherapy in AIDS virus infections. Nat Med. (2003) 9:861–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-861

56. Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Stecher C, Zettl M, Rosskopf S, Rieger A, Zlabinger GJ, et al. Antibodies targeting BTLA or TIM-3 enhance HIV-1 specific T cell responses in combination with PD-1 blockade. Clin Immunol. (2017) 183:167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.09.002

57. Velu V, Titanji K, Zhu B, Husain S, Pladevega A, Lai L, et al. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature (2009) 458:206–10. doi: 10.1038/nature07662

58. Dyavar Shetty R, Velu V, Titanji K, Bosinger SE, Freeman GJ, Silvestri G, et al. PD-1 blockade during chronic SIV infection reduces hyperimmune activation and microbial translocation in rhesus macaques. J Clin Invest. (2012) 122:1712–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI60612

59. Elahi S, Dinges WL, Lejarcegui N, Laing KJ, Collier AC, Koelle DM, et al. Protective HIV-specific CD8+ T cells evade Treg cell suppression. Nat Med. (2011) 17:989–95. doi: 10.1038/nm.2422

60. Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, Klenerman P, Gillespie GM, Papagno L, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med. (2002) 8:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379

61. Peretz Y, He Z, Shi Y, Yassine-Diab B, Goulet JP, Bordi R, et al. CD160 and PD-1 co-expression on HIV-specific CD8 T cells defines a subset with advanced dysfunction. PLoS Pathog. (2012) 8:e1002840. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002840

62. Wykes MN, Lewin SR. Immune checkpoint blockade in infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. (2018) 18:91–104. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.112

63. Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, Trautmann L, Procopio FA, Yassine-Diab B, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med. (2009) 15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972

64. Fromentin R, Bakeman W, Lawani MB, Khoury G, Hartogensis W, DaFonseca S, et al. CD4+ T cells expressing PD-1, TIGIT and LAG-3 contribute to HIV persistence during ART. PLoS Pathog. (2016) 12:e1005761. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005761

65. Imamichi H, Dewar RL, Adelsberger JW, Rehm CA, O'Doherty U, Paxinos EE, et al. Defective HIV-1 proviruses produce novel protein-coding RNA species in HIV-infected patients on combination antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:8783–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609057113

66. Hughes SH, Coffin JM. What integration sites tell us about HIV persistence. Cell Host Microbe (2016) 19:588–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.010

67. Mesri EA, Feitelson MA, Munger K. Human viral oncogenesis: a cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host Microbe (2014) 15:266–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.011

68. Matsuoka M, Green PL. The HBZ gene, a key player in HTLV-1 pathogenesis. Retrovirology (2009) 6:71. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-71

69. Satou Y, Yasunaga J, Zhao T, Yoshida M, Miyazato P, Takai K, et al. HTLV-1 bZIP factor induces T-cell lymphoma and systemic inflammation in vivo. PLoS Pathog. (2011) 7:e1001274. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001274

70. Tanaka A, Matsuoka M. HTLV-1 alters T cells for viral persistence and transmission. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:461. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00461

71. Kataoka K, Shiraishi Y, Takeda Y, Sakata S, Matsumoto M, Nagano S, et al. Aberrant PD-L1 expression through 3'-UTR disruption in multiple cancers. Nature (2016) 534:402–6. doi: 10.1038/nature18294

72. Sawada L, Nagano Y, Hasegawa A, Kanai H, Nogami K, Ito S, et al. IL-10-mediated signals act as a switch for lymphoproliferation in human T-cell leukemia virus type-1 infection by activating the STAT3 and IRF4 pathways. PLoS Pathog. (2017) 13:e1006597. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006597

73. Kuipers H, Muskens F, Willart M, Hijdra D, van Assema FB, Coyle AJ, et al. Contribution of the PD-1 ligands/PD-1 signaling pathway to dendritic cell-mediated CD4+ T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. (2006) 36:2472–82. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635978

74. Yu X, Harden K, Gonzalez LC, Francesco M, Chiang E, Irving B, et al. The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. (2009) 10:48–57. doi: 10.1038/ni.1674

75. Stengel KF, Harden-Bowles K, Yu X, Rouge L, Yin J, Comps-Agrar L, et al. Structure of TIGIT immunoreceptor bound to poliovirus receptor reveals a cell-cell adhesion and signaling mechanism that requires cis-trans receptor clustering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:5399–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120606109

76. Arasanz H, Gato-Cañas M, Zuazo M, Ibañez-Vea M, Breckpot K, Kochan G, et al. PD1 signal transduction pathways in T cells. Oncotarget (2017) 8:51936–45. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17232

77. Paster W, Bruger AM, Katsch K, Grégoire C, Roncagalli R, Fu G, et al. A THEMIS:SHP1 complex promotes T-cell survival. EMBO J. (2015) 34:393–409. doi: 10.15252/embj.201387725

78. Coombes JL, Robinson NJ, Maloy KJ, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells and intestinal homeostasis. Immunol Rev. (2005) 204:184–94. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00250.x

79. Liu J, Cao S, Kim S, Chung EY, Homma Y, Guan X, et al. Interleukin-12: an update on its immunological activities, signaling and regulation of gene expression. Curr Immunol Rev. (2005) 1:119–37. doi: 10.2174/1573395054065115

80. Ratner L, Waldmann TA, Janakiram M, Brammer JE. Rapid progression of adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma after PD-1 inhibitor therapy. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:1947–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1803181

81. Wartewig T, Kurgyis Z, Keppler S, Pechloff K, Hameister E, Öllinger R, et al. PD-1 is a haploinsufficient suppressor of T cell lymphomagenesis. Nature (2017) 552:121–5. doi: 10.1038/nature24649

Keywords: co-inhibitory receptor, HTLV-1, HIV-1, PD-1, TIGIT

Citation: Yasuma-Mitobe K and Matsuoka M (2018) The Roles of Coinhibitory Receptors in Pathogenesis of Human Retroviral Infections. Front. Immunol. 9:2755. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02755

Received: 26 June 2018; Accepted: 08 November 2018;

Published: 27 November 2018.

Edited by:

Alexandre M. Carmo, i3S, Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde, PortugalReviewed by:

Ulf Dittmer, Universität Duisburg-Essen, GermanyCopyright © 2018 Yasuma-Mitobe and Matsuoka. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Masao Matsuoka, bWFtYXRzdUBrdW1hbW90by11LmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.