- 1Section of Pharmacology, Department of Medicine, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

- 2Department of Surgery and Biomedical Sciences, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

Glucocorticoid hormones regulate essential body functions in mammals, control cell metabolism, growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. Importantly, they are potent suppressors of inflammation, and multiple immune-modulatory mechanisms involving leukocyte apoptosis, differentiation, and cytokine production have been described. Due to their potent anti-inflammatory and immune-suppressive activity, synthetic glucocorticoids (GCs) are the most prescribed drugs used for treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. It is long been noted that males and females exhibit differences in the prevalence in several autoimmune diseases (AD). This can be due to the role of sexual hormones in regulation of the immune responses, acting through their endogenous nuclear receptors to mediate gene expression and generate unique gender-specific cellular environments. Given the fact that GCs are the primary physiological anti-inflammatory hormones, and that sex hormones may also exert immune-modulatory functions, the link between GCs and sex hormones may exist. Understanding the nature of this possible crosstalk is important to unravel the reason of sexual disparity in AD and to carefully prescribe these drugs for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. In this review, we discuss similarities and differences between the effects of sex hormones and GCs on the immune system, to highlight possible axes of functional interaction.

Introduction

The interaction between endocrine and immune systems ensures the correct function of immune system. Women mount stronger immune responses against foreign but also against self-antigens, and the prevalence of most autoimmune diseases (AD) is greatly increased in women compared to men (1–4). An important role underlying the difference in activity of immune cells in men and women is attributed to sex hormones (4, 5).

Steroid hormones, such as estrogens, prolactin, progesterone, and glucocorticoids (GCs) modulate the development and activity of both innate and adaptive immunity differently in men and women (2, 5–8). Therefore, characterization of the mechanisms of hormonal regulation of different immune cell types is important for understanding the regulatory circuits critical for keeping a competent and a healthy immune system and to improve therapy of AD.

The degree and the duration of the immune response is influenced by the number and the type of circulating immune cells; therefore, the effect of steroid hormones on survival and differentiation of T and B lymphocytes and cells of innate immune system will define the numeric leukocyte output in the periphery. Hormonal regulation of cytokine production impacts on differentiation of naïve T cells into the particular effector subtypes, thus defining the type of the mounted immune responses. Interestingly, since sex hormones and GCs are acting on the same cellular pathways that regulate leukocytes growth, differentiation, and survival, their simultaneous action would likely enhance or abrogate the effects elicited by individual factors. Therefore, biologic differences in endogenous GCs levels, as well as exposure of an individual to specific environmental stimuli, including presence of chronic inflammatory disease, prolonged stress, metabolic challenges or injuries, as well as pharmacologic administration of exogenous GCs, will alter the expected gender-related effects on immunity and ADs. The converging and diverging effects of GCs and sex hormones on different cells types of the immune system are discussed in this minireview.

Steroid Hormones: Mechanisms of Action

Corticosteroids and sex hormones are derived from cholesterol through the same sterodoigenic pathway, with common metabolic intermediate, progesterone, and are under the control of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal gland (HPA) axis (9). The main natural GCs (i.e., cortisol) are produced in the cortical part of the adrenal gland (9). Biosynthesis of androgens, including testosterone, occurs mainly in Leydig cells in male gonads, and small amounts are produced by the ovary and adrenal cortex in females (9). The androgens dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), androstenedione, and testosterone are the precursors of estrogens, produced in females primarily in ovaries (9).

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are essential endocrine regulators of body functions in homeostasis and adaptation to environmental changes. One important feature of GCs regulation is the circadian control of GCs secretion by the HPA axis. The rhythmically released GCs may have an impact on immunity regulation (10). Endogenous GCs act on a variety of cell types to regulate the expression of genes controlling cellular metabolism, growth, differentiation, and apoptosis (11, 12). Thus, proper production and activity of the endogenous GCs is critical for the regulation of inflammatory events during tissue repair and pathogens elimination. Due to their potent immune-suppressive and anti-inflammatory function, synthetic GCs are extensively used in clinic to treat acute and chronic inflammation (13, 14).

The GCs act via genomic (transcriptional) and non-genomic (transcription-independent) mechanisms. Most cellular actions of GCs are mediated by binding to its cognate intracellular receptor (GR), transcription factor of the nuclear receptors (NR) superfamily (15). GR shares functional domains with other NR that include an N-terminal transactivation domain, a highly conserved central DNA binding domain, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (11). After ligand-induced conformational changes, GR translocates into the nucleus where it regulates transcription of hundreds of genes. It may bind directly to DNA via glucocorticoid recognition elements, or regulate gene expression via indirect mechanisms (16, 17). GR may directly interact with NF-κB (17, 18), a key transcription factor that activates many pro-inflammatory genes (19), as well as with other transcription factors (TFs), such as STAT-3 and -5 (20, 21), AP-1 (22), and CREB (23). GR does not interfere with the DNA binding activity of NF-κB, but inhibits its transcriptional activation function via preventing its nuclear translocation (17, 18), or interfering with transcriptional machinery by competition with co-factors such as p300/CBP (24), thus repressing the expression of pro-inflammatory genes, such as TNF-α, IL-1, and ICAM-1 (13, 25). Mechanisms of GCs actions also include induction of proteins with anti-inflammatory activities, such as glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) (26, 27), which mediates many of the GCs’ activities (28–31), including inhibition of RAS/RAF/MAPK pathways (32, 33), and of NF-κB and AP-1 activities (34–37). “Non-genomic” effects of GCs include direct interaction of liganded GR with diverse intracellular mediators and modulating several signaling pathways, including protein kinase C, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, and src kinase pathways (38–42).

Sex Hormones

Sex hormones regulate reproductive and metabolic body functions throughout the life of the subjects. Sex hormones influence immune cell function and inflammation: androgens are mainly anti-inflammatory (7), whereas estrogens have both pro- and anti-inflammatory roles, depending on several factors, such as type of immune response or variability of expression of different estrogen receptor (ER) isoforms (8).

Estrogens exert their effects through binding to ERα or ERβ, TFs of NR superfamily that regulate expression of genes involved in cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and reproductive functions (6, 43). Similar to GR, nuclear ERs bind DNA either directly through estrogen response elements, or indirectly, via ERE-independent TFs, such as NF-κB, SP1, AP-1, C/EBPβ (43–45), to induce or repress gene expression. Estrogens also elicit rapid (“non-genomic”) signal transduction effects, via modulation of intracellular calcium, cAMP, potassium currents, phospholipase C activation, and stimulation of PI3K/AKT and ERK pathways (44).

Estrogen receptors are expressed in various types of immune cells, including lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DC) (5, 8). Estrogens were shown to exert both, anti- and pro-inflammatory effects, depending on the context and combination of factors that include: the type of the immune cell target, the concentration of the hormone, the type of immune stimulus (foreign or auto-antigens), the target organ microenvironment, and the relative expression of ERα and ERβ. Estrogens may promote inflammation via regulation of the expression of inflammatory mediators via Akt/mTOR pathway (46, 47). However, pregnancy or higher doses of ectopic estrogens typically suppress immune responses (4), by repressing the expression of multiple NF-κB- and c-Jun-driven cytokine genes (45, 48–50), similar to GCs. ERα may displace p65 and CREB and their associated co-regulators from NF-κB binding site (51). Progesterone (P4) is produced at high levels during the menstrual cycle and during pregnancy. P4 signals through the progesterone receptor (PR) and to a lesser extent, through GR and mineralocorticoid receptors. P4 is expressed in different immune cells types, including NK, macrophages, DCs, and T cells (52), and have broad anti-inflammatory effects of the immune system by decreasing leukocytes activation and production of pro-inflammatory mediators (5). NF-κB inhibition is also suggested to play a role in these effects of P4 (53).

Similar to GCs, male steroid hormones demonstrate mostly the suppressive role in immune function (2, 54–57), via binding to androgen receptor (AR), also a member of NR superfamily, and regulation of target gene expression (58). AR recognizes directly the androgen response elements in the regulatory regions of AR target genes (59). Androgens, including dihydrotestosterone and testosterone, generally suppress immune cell activity, by reducing the inflammatory and promoting anti-inflammatory mediators’ expression by macrophages and T cells (5, 60–62). The levels of androgen DHEA are reduced in patients with RA (63) and inflammatory bowel disease (64) suggesting that DHEA may cover many aspects of immune regulatory effects of sex hormones.

Moreover, an indirect immunomodulatory effect of androgens may be related to the anti-inflammatory activity of endogenous GCs due to their effect on the HPA axis (65).

Modulation of Immune Responses by Steroid Hormones

Effect of Steroid Hormones on Innate Immunity

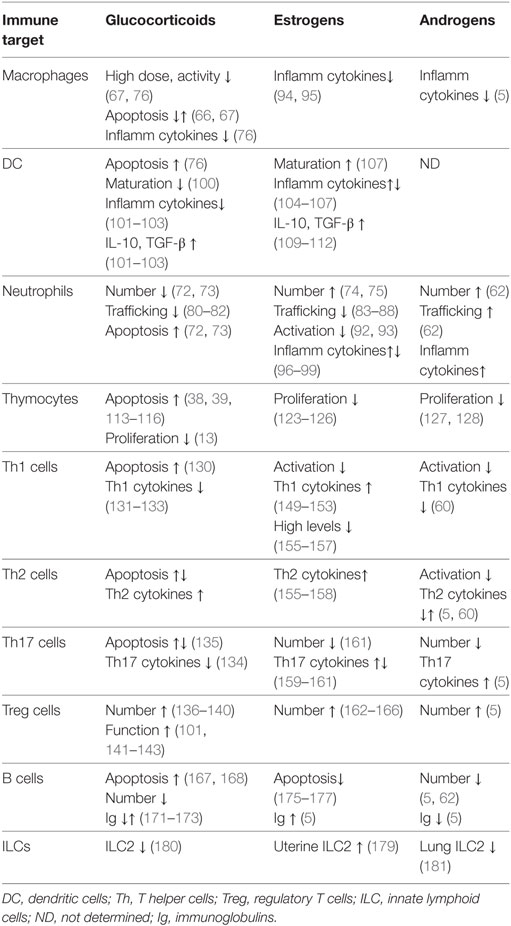

Both GCs and sex steroid modulate the development and function of various cells of innate immunity, including neutrophils, macrophages, natural killer cells, and DC (Table 1). GCs actions include regulation of apoptosis in many cell types: they exert a protective effect in macrophages, by inhibiting activation of caspases and contributing to inflammation resolution (66); however, prolonged usage of GCs promotes apoptosis in macrophages (67), natural killer cells (68), DC (69–71), neutrophils (72, 73), and eosinophils (72). To the contrary, estrogens and androgens increase the number of neutrophils (74, 75).

Glucocorticoids have mainly suppressive effects on the cells of innate immunity (Table 1). High doses of GCs inhibit most of the functions of tissue macrophages, such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis, proliferation, and antigen presentation (67, 76). GCs suppress the expression of various pro-inflammatory cytokines released by macrophages, such as IFN-γ, IL-1α, and IL-1β (76). In addition, the synthesis of anti-inflammatory molecules annexin A1 and GILZ in macrophages contributes to the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive action of GCs (28, 29, 77). GCs also inhibit monocytes’ chemotaxis by reducing expression of chemokines, such as CXCL-1, IL-8 and CXCL-2, and CCL2 (78, 79), control granulocyte trafficking by reducing expression of adhesion molecules, such as Mac-1 and L-selectin on neutrophils (80–82), thus limiting the inflammatory response. In addition, GCs prevent neutrophils migration into inflamed tissues via the upregulation of GILZ and annexin A1 (82). Similar to GCs, treatment with estrogens inhibits neutrophils’ activity by restricting their recruitment (83–88) and inhibiting the NFκB-dependent production of major neutrophil chemoattractants CXCL-1, CXCL2, CXCL3, and CXCL8 in experimental models of tissue injury (86–91). Estradiol inhibits neutrophil activation through a reduction in oxidative metabolism (92), adhesion to endothelial cells via upregulation of the anti-inflammatory protein annexin A1 (93), and attenuates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (94, 95) and in neutrophils and macrophages (96–99). Interestingly, the inhibition of NFκB activity is a central mechanism underlying these actions (83).

Glucocorticoids and estrogens have both convergent and divergent actions in DCs. GCs inhibit DC function in several ways: by promoting apoptosis (76), disturbing maturation of immature DCs (100), and inducing a tolerogenic phenotype, via downregulating the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II and co-stimulatory molecules and cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-12 (101, 102). Such changes are associated with reduced proliferative and T helper 1 (Th1) responses by T cells (103), and increase in immunosuppressive regulatory T (Treg) cells (101). Instead, estrogens promote DC cell differentiation and MHCII expression, and induce the expression of IL-6, IL-23, IL-12, and IL-1β (104–107), thus increasing the type-1 responses (108). On the other hand, similar to GCs, estrogens induce a tolerogenic phenotype in DC, by decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-12, CXCL8, and CCL2 (109–111), and upregulating inhibitory molecules PD-L1 and PD-L2, and regulatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β, thus also leading to a decrease in the Th1 cells activation and a shift toward production of Th2-type cytokines (109, 112).

Effect of Steroid Hormones on Adaptive Immunity

Controlled elimination of T cells during thymocyte development and T cell-mediated immune responses is essential to prevent immunopathologies, such as autoimmunity and cancer. GCs induce apoptosis in developing thymocytes (113–116) and regulate both “death by neglect” and positive selection (117). The GC-induced apoptosis in thymocytes is also attributed to non-genomic effects of GR (38, 39, 118, 119). Their role in positive selection is inferred from the antagonism between GCs and T cell repertoire (TCR)-activated signals, which allows cells with intermediate TCR affinity to be positively selected (120–122).

The growth suppressive effect of GCs on thymocytes is common to the action of female and male sex hormones. Similar to GCs, estrogens inhibit thymocyte proliferation (123) and induce thymic atrophy (124). Pregnancy is associated with accelerated thymic involution (125, 126). Androgens also restrain active cell cycling and the number of immature thymocytes (127). The number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is lower in males around 50–75 of age compared to females, and the diversity of the TCR in females is larger than in males of the same age (128).

Upon TCR activation and stimulation with particular cytokines, naïve mature CD4+ T cells differentiate in the periphery into one of several lineages of T helper (Th) cells that include Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cells (129). GCs promote the shift from Th1 to Th2 type immune responses by differentially regulating apoptosis of Th1 and Th2 cells (130), and by interfering with the activity of their master regulators T-bet and GATA-3, respectively (131–133). GCs can also suppress the production of TNF-α, IL-12, and IFN-γ and induce the production of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 (13, 130). GCs inhibit the production of Th17-type cytokines in AD (134), although the sensitivity of Th17 cells to GC-induced apoptosis varies dependent on disease-specific microenvironment (135). Treg cells play a critical role in regulating immune responses and peripheral tolerance. GCs upregulate expression of FoxP3, the master regulator of Treg cells, expand Treg cell population (136–140), and increase Treg function in AD (141–143). Expression of GCs’ target gene GILZ also contributes to the GC-mediated regulation of Th1/Th2 balance (144, 145), and the induction of Treg cells by promoting TGF-β-dependent FoxP3 expression (136).

Sex steroids also modulate the differentiation and function of all subsets of T cells (75, 146–148). Contrary to GCs, estrogens promote INF-γ production by Th1 cells in both human and mice (149–151), via potentially direct interaction of ER with the Ifng promoter (150, 152), upregulation of Th-1 transcription factor T-bet (151, 153), or via microRNA-dependent suppression of IFN-γ expression (154). However, high levels of estrogen skew the immune response from Th1 to Th2-type (155–157), similar to GCs. Estradiol also regulates anti-inflammatory Th2 shift by activating SGK1 kinase (158). The effects of estrogens on Th17 subset are different depending on experimental model, leading to enhancement (159, 160) or decrease (161) of Th17-dependent inflammation. Like GCs, estrogens promote the expansion of Treg cells (162, 163) by upregulating the expression of FoxP3, PD-1, and CTLA-4 (162–166), therefore, GCs and estrogens may co-operate in promoting the Treg development and activity.

Glucocorticoids and estrogens elicit opposite effects on B cells. GCs have a pro-apoptotic effect on developing B lymphocytes in the bone marrow (167, 168). On the other hand, B-lymphoblastic leukemia cells are resistant to GC-induced apoptosis, due to enhanced expression of B-cell lymphoma-2 protein (167, 169). GILZ mediates GC-induced apoptosis in B cells as shown by the accumulation of B cells in the bone marrow and in the periphery in GILZ-deficient mice, due to reduced B cell apoptosis (170). GCs affect directly humoral response by reducing circulating immunoglobulins (Igs) although some studies have shown an increase of IgE production in conjunction with IL-4 (171–173). Instead, enhanced antibody production is observed in women, suggesting that female sex hormones stimulate B cell-mediated responses. Estrogen treatment also interferes with normal tolerance of naive DNA-reactive B cells, thus contributing to the development of AD. Elevated estrogen alters the negative selection of DNA-reactive B cells in the periphery (174, 175), interfering with proper B cell receptor signaling and regulation of B cells activation and apoptosis (176, 177). Thus, pharmacologic treatment with synthetic GCs may be useful in suppression of the enhanced B cell activities in AD.

Effect of Steroid Hormones on Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC)

Innate lymphoid cell is a most recently identified immune cell type, which contributes to inflammation, immunity, and the maintenance of tissue integrity and homeostasis (178). Recent evidence demonstrated that group 2 ILC2s are present in the uterus under control of estrogens and are increased upon estrogen administration (179). It is, therefore, possible that estrogens modulate tolerance via ILC2-mediated modulation of the protective Th2 shift in pregnancy. Instead, ILC2 promote lung inflammation during asthma (180). Interestingly, male mice have reduced numbers of ILC2s in peripheral tissues compared to females, and the number of ILC2s in the lungs is negatively regulated by androgens (181), consistent with the overall suppressive role of male steroids in immunity. GCs were shown to modulate the cytokine production by the ILC2s, thus these finding suggests a modulatory role of steroid hormones in ILCs and homeostasis of specific tissues.

Interaction Between GR and Sex Hormone Receptors

GR, ER, and AR are ligand-activated TFs belonging to the NR superfamily (182). Experimental evidence shows that GR and sex hormone receptors share some common mechanisms of gene regulation, but they also exploit different mechanisms to repress pro-inflammatory genes depending on the target gene, cell type, and interactions with other TFs.

Estrogen receptor, AR, and GR induce expression of genes that control proliferation, differentiation, and cell death by directly binding to specific hormone response elements or by indirectly tethering through TFs, such as AP1 (22, 183–185), Sp1 (186, 187), Stat1 (188), and NFκB (189, 190). The potential crosstalk in the regulation of gene expression by GR and ER was studied mostly in non-immune cell types, which may, however, provide mechanistic evidence of the mechanisms potentially operating in cells of the immune system.

The functional interaction between GR and ER signaling has been observed in several cancer cell lines, and requires additional factors, such as MED14, SRC-2, and SRC-3 in the same complex, resulting in either cooperative or mutually inhibiting effects (191). GR may inhibit the action of ER via distinct mechanisms. GCs may inhibit the estrogen signaling indirectly, by inducing the estrogen-metabolizing enzyme in breast cancer cells (192). Synthetic GC dexamethasone (Dex) antagonizes ERα-regulated target gene expression in breast cancer cells treated with estrogen and Dex simultaneously via the direct protein–protein interaction and the recruitment of GR to ERα binding sites (193). This recruitment is facilitated by AP-1 and leads to a displacement of ERα from DNA and repression of its target genes transcription (193, 194).

Reciprocally, the ER-mediated inhibition of the GR function was also described. Treatment of the breast cancer cell line with estrogen agonists downregulates GR protein levels via proteosome-mediated degradation (195). On the other hand, in an experimental lung inflammation rat model, the ER antagonist (ICI 182780) blocked the anti-inflammatory effects of GCs, suggesting that GR and ER co-operate in this setting in their anti-inflammatory activity (196). A subset of pro-inflammatory genes was repressed by both ER and GR (CD69, MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8), and the ER antagonist blocked Dex-mediated repression of these genes (197), by preventing the recruitment of nuclear coactivator 2 by the GR necessary for trans-repression. These data suggest that GR and ER functionally cooperate on selected promoters.

The functional effect of the interaction of GR with PR and ER is less characterized. PR and GR were shown to interact in vitro, and in vivo. Progesterone acts via GR to repress IL-1β-driven COX-2 activation (198, 199). The AR and the GR form heterodimers at a common DNA site both in vitro and in vivo, and this interaction leads to mutual inhibition of transcriptional activity (200).

Conclusions

Most of the mechanistic insights into synergistic and antagonizing effects of GR and sex steroid receptors in gene expression were obtained in non-immune cells, and, to our knowledge, the interactions between GCs and sex hormones in immune cells have not been studied in vitro. However, receptors for both classes of hormones are present in variety of immune cells, where, as reviewed above, they have been separately shown to influence various aspect of immune cell activity, ranging from cell survival to differentiation and expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules (Table 1). Thus, the investigation of possible mutual influence of GCs and sex hormones in immune cells and its mechanisms is warranted.

The effects of female sex hormones on cells of adaptive immune system such as Th cell differentiation and B cells may underlie the higher predisposition of women to AD (4). The GC-mediated suppression of Th1 and promotion of Treg cell activity, as well as apoptotic effects on B cells may explain in part the cellular basis of GCs’ efficacy in dampening the symptoms of many AD (13). Development of novel therapies for immune cell type- and gender-specific modulation of immune system may represent future direction for treatment of AD.

Author Contributions

OB, SB, and CR wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Education and Research, Grants PRIN2015ZT9HXY to CR and RBFR13BN6Y to OB.

References

1. Grossman CJ. Interactions between the gonadal steroids and the immune system. Science (1985) 227(4684):257–61. doi:10.1126/science.3871252

2. Olsen NJ, Kovacs WJ. Gonadal steroids and immunity. Endocr Rev (1996) 17(4):369–84. doi:10.1210/edrv-17-4-369

3. Talal N. Sex steroid hormones and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum (1981) 24(8):1054–6. doi:10.1002/art.1780240811

4. Ortona E, Pierdominici M, Maselli A, Veroni C, Aloisi F, Shoenfeld Y. Sex-based differences in autoimmune diseases. Ann Ist Super Sanita (2016) 52(2):205–12. doi:10.4415/ANN_16_02_12

5. Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol (2016) 16(10):626–38. doi:10.1038/nri.2016.90

6. Hewitt SC, Winuthayanon W, Korach KS. What’s new in estrogen receptor action in the female reproductive tract. J Mol Endocrinol (2016) 56(2):R55–71. doi:10.1530/JME-15-0254

7. Gilliver SC. Sex steroids as inflammatory regulators. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (2010) 120(2–3):105–15. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.12.015

8. Straub RH. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev (2007) 28(5):521–74. doi:10.1210/er.2007-0001

9. Miller WL, Auchus RJ. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr Rev (2011) 32(1):81–151. doi:10.1210/er.2010-0013

10. Dumbell R, Matveeva O, Oster H. Circadian clocks, stress, and immunity. Front Endocrinol (2016) 7:37. doi:10.3389/fendo.2016.00037

11. Godowski PJ, Rusconi S, Miesfeld R, Yamamoto KR. Glucocorticoid receptor mutants that are constitutive activators of transcriptional enhancement. Nature (1987) 325(6102):365–8. doi:10.1038/325365a0

12. Grad I, Picard D. The glucocorticoid responses are shaped by molecular chaperones. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2007) 275(1–2):2–12. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2007.05.018

13. Cain DW, Cidlowski JA. Immune regulation by glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17(4):233–47. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.1

14. Riccardi C, Bruscoli S, Migliorati G. Molecular mechanisms of immunomodulatory activity of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Res (2002) 45(5):361–8. doi:10.1006/phrs.2002.0969

15. Vandewalle J, Luypaert A, De Bosscher K, Libert C. Therapeutic mechanisms of glucocorticoids. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2018) 29(1):42–54. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.010

16. Guido EC, Delorme EO, Clemm DL, Stein RB, Rosen J, Miner JN. Determinants of promoter-specific activity by glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Endocrinol (1996) 10(10):1178–90. doi:10.1210/me.10.10.1178

17. McEwan IJ, Wright AP, Gustafsson JA. Mechanism of gene expression by the glucocorticoid receptor: role of protein-protein interactions. Bioessays (1997) 19(2):153–60. doi:10.1002/bies.950190210

18. Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol (1998) 16:225–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225

19. Smale ST. Selective transcription in response to an inflammatory stimulus. Cell (2010) 140(6):833–44. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.037

20. Zhang Z, Jones S, Hagood JS, Fuentes NL, Fuller GM. STAT3 acts as a co-activator of glucocorticoid receptor signaling. J Biol Chem (1997) 272(49):30607–10. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.49.30607

21. Stocklin E, Wissler M, Gouilleux F, Groner B. Functional interactions between Stat5 and the glucocorticoid receptor. Nature (1996) 383(6602):726–8. doi:10.1038/383726a0

22. Jonat C, Rahmsdorf HJ, Park KK, Cato AC, Gebel S, Ponta H, et al. Antitumor promotion and antiinflammation: down-modulation of AP-1 (Fos/Jun) activity by glucocorticoid hormone. Cell (1990) 62(6):1189–204. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90395-U

23. Imai E, Miner JN, Mitchell JA, Yamamoto KR, Granner DK. Glucocorticoid receptor-cAMP response element-binding protein interaction and the response of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene to glucocorticoids. J Biol Chem (1993) 268(8):5353–6.

24. Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, et al. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell (1996) 85(3):403–14. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81118-6

25. Van Bogaert T, De Bosscher K, Libert C. Crosstalk between TNF and glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathways. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2010) 21(4):275–86. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.04.003

26. D’Adamio F, Zollo O, Moraca R, Ayroldi E, Bruscoli S, Bartoli A, et al. A new dexamethasone-induced gene of the leucine zipper family protects T lymphocytes from TCR/CD3-activated cell death. Immunity (1997) 7(6):803–12. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80398-2

27. Cannarile L, Zollo O, D’Adamio F, Ayroldi E, Marchetti C, Tabilio A, et al. Cloning, chromosomal assignment and tissue distribution of human GILZ, a glucocorticoid hormone-induced gene. Cell Death Differ (2001) 8(2):201–3. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4400798

28. Berrebi D, Bruscoli S, Cohen N, Foussat A, Migliorati G, Bouchet-Delbos L, et al. Synthesis of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) by macrophages: an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive mechanism shared by glucocorticoids and IL-10. Blood (2003) 101(2):729–38. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-02-0538

29. Hoppstadter J, Kessler SM, Bruscoli S, Huwer H, Riccardi C, Kiemer AK. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper: a critical factor in macrophage endotoxin tolerance. J Immunol (2015) 194(12):6057–67. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1403207

30. Ronchetti S, Migliorati G, Riccardi C. GILZ as a mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Front Endocrinol (2015) 6:170. doi:10.3389/fendo.2015.00170

31. Vago JP, Tavares LP, Garcia CC, Lima KM, Perucci LO, Vieira EL, et al. The role and effects of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper in the context of inflammation resolution. J Immunol (2015) 194(10):4940–50. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1401722

32. Ayroldi E, Zollo O, Macchiarulo A, Di Marco B, Marchetti C, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper inhibits the Raf-extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by binding to Raf-1. Mol Cell Biol (2002) 22(22):7929–41. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.22.7929-7941.2002

33. Bruscoli S, Velardi E, Di Sante M, Bereshchenko O, Venanzi A, Coppo M, et al. Long glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (L-GILZ) protein interacts with ras protein pathway and contributes to spermatogenesis control. J Biol Chem (2012) 287(2):1242–51. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.316372

34. Asselin-Labat ML, David M, Biola-Vidamment A, Lecoeuche D, Zennaro MC, Bertoglio J, et al. GILZ, a new target for the transcription factor FoxO3, protects T lymphocytes from interleukin-2 withdrawal-induced apoptosis. Blood (2004) 104(1):215–23. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-12-4295

35. Ayroldi E, Migliorati G, Bruscoli S, Marchetti C, Zollo O, Cannarile L, et al. Modulation of T-cell activation by the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper factor via inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB. Blood (2001) 98(3):743–53. doi:10.1182/blood.V98.3.743

36. Riccardi C, Bruscoli S, Ayroldi E, Agostini M, Migliorati G. GILZ, a glucocorticoid hormone induced gene, modulates T lymphocytes activation and death through interaction with NF-kB. Adv Exp Med Biol (2001) 495:31–9. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0685-0_5

37. Di Marco B, Massetti M, Bruscoli S, Macchiarulo A, Di Virgilio R, Velardi E, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ)/NF-kappaB interaction: role of GILZ homo-dimerization and C-terminal domain. Nucleic Acids Res (2007) 35(2):517–28. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl1080

38. Cifone MG, Migliorati G, Parroni R, Marchetti C, Millimaggi D, Santoni A, et al. Dexamethasone-induced thymocyte apoptosis: apoptotic signal involves the sequential activation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C, acidic sphingomyelinase, and caspases. Blood (1999) 93(7):2282–96.

39. Marchetti MC, Di Marco B, Cifone G, Migliorati G, Riccardi C. Dexamethasone-induced apoptosis of thymocytes: role of glucocorticoid receptor-associated Src kinase and caspase-8 activation. Blood (2003) 101(2):585–93. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-06-1779

40. Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M. Multiple actions of steroid hormones – a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol Rev (2000) 52(4):513–56.

41. Bruscoli S, Di Virgilio R, Donato V, Velardi E, Baldoni M, Marchetti C, et al. Genomic and non-genomic effects of different glucocorticoids on mouse thymocyte apoptosis. Eur J Pharmacol (2006) 529(1–3):63–70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.10.053

42. Croxtall JD, Choudhury Q, Flower RJ. Glucocorticoids act within minutes to inhibit recruitment of signalling factors to activated EGF receptors through a receptor-dependent, transcription-independent mechanism. Br J Pharmacol (2000) 130(2):289–98. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703272

43. Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, et al. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev (2007) 87(3):905–31. doi:10.1152/physrev.00026.2006

44. Kovats S. Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell Immunol (2015) 294(2):63–9. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.01.018

45. Cvoro A, Tzagarakis-Foster C, Tatomer D, Paruthiyil S, Fox MS, Leitman DC. Distinct roles of unliganded and liganded estrogen receptors in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell (2006) 21(4):555–64. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.014

46. Calippe B, Douin-Echinard V, Delpy L, Laffargue M, Lelu K, Krust A, et al. 17Beta-estradiol promotes TLR4-triggered proinflammatory mediator production through direct estrogen receptor alpha signaling in macrophages in vivo. J Immunol (2010) 185(2):1169–76. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0902383

47. Pratap UP, Sharma HR, Mohanty A, Kale P, Gopinath S, Hima L, et al. Estrogen upregulates inflammatory signals through NF-kappaB, IFN-gamma, and nitric oxide via Akt/mTOR pathway in the lymph node lymphocytes of middle-aged female rats. Int Immunopharmacol (2015) 29(2):591–8. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2015.09.024

48. Cvoro A, Tatomer D, Tee MK, Zogovic T, Harris HA, Leitman DC. Selective estrogen receptor-beta agonists repress transcription of proinflammatory genes. J Immunol (2008) 180(1):630–6. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.630

49. Stein B, Yang MX. Repression of the interleukin-6 promoter by estrogen receptor is mediated by NF-kappa B and C/EBP beta. Mol Cell Biol (1995) 15(9):4971–9. doi:10.1128/MCB.15.9.4971

50. An J, Ribeiro RC, Webb P, Gustafsson JA, Kushner PJ, Baxter JD, et al. Estradiol repression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha transcription requires estrogen receptor activation function-2 and is enhanced by coactivators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1999) 96(26):15161–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.26.15161

51. Nettles KW, Gil G, Nowak J, Metivier R, Sharma VB, Greene GL. CBP is a dosage-dependent regulator of nuclear factor-kappaB suppression by the estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol (2008) 22(2):263–72. doi:10.1210/me.2007-0324

52. Teilmann SC, Clement CA, Thorup J, Byskov AG, Christensen ST. Expression and localization of the progesterone receptor in mouse and human reproductive organs. J Endocrinol (2006) 191(3):525–35. doi:10.1677/joe.1.06565

53. Hardy DB, Janowski BA, Corey DR, Mendelson CR. Progesterone receptor plays a major antiinflammatory role in human myometrial cells by antagonism of nuclear factor-kappaB activation of cyclooxygenase 2 expression. Mol Endocrinol (2006) 20(11):2724–33. doi:10.1210/me.2006-0112

54. Roubinian JR, Talal N, Greenspan JS, Goodman JR, Siiteri PK. Effect of castration and sex hormone treatment on survival, anti-nucleic acid antibodies, and glomerulonephritis in NZB/NZW F1 mice. J Exp Med (1978) 147(6):1568–83. doi:10.1084/jem.147.6.1568

55. Steinberg AD, Roths JB, Murphy ED, Steinberg RT, Raveche ES. Effects of thymectomy or androgen administration upon the autoimmune disease of MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mice. J Immunol (1980) 125(2):871–3.

56. Ariga H, Edwards J, Sullivan DA. Androgen control of autoimmune expression in lacrimal glands of MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol (1989) 53(3):499–508. doi:10.1016/0090-1229(89)90011-1

57. Fox HS. Androgen treatment prevents diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Exp Med (1992) 175(5):1409–12. doi:10.1084/jem.175.5.1409

58. Chang CS, Kokontis J, Liao ST. Molecular cloning of human and rat complementary DNA encoding androgen receptors. Science (1988) 240(4850):324–6. doi:10.1126/science.3353726

59. MacLean HE, Warne GL, Zajac JD. Localization of functional domains in the androgen receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (1997) 62(4):233–42. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(97)00049-6

60. Liva SM, Voskuhl RR. Testosterone acts directly on CD4+ T lymphocytes to increase IL-10 production. J Immunol (2001) 167(4):2060–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2060

61. D’Agostino P, Milano S, Barbera C, Di Bella G, La Rosa M, Ferlazzo V, et al. Sex hormones modulate inflammatory mediators produced by macrophages. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1999) 876:426–9. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07667.x

62. Lai JJ, Lai KP, Zeng W, Chuang KH, Altuwaijri S, Chang C. Androgen receptor influences on body defense system via modulation of innate and adaptive immune systems: lessons from conditional AR knockout mice. Am J Pathol (2012) 181(5):1504–12. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.008

63. Straub RH, Harle P, Atzeni F, Weidler C, Cutolo M, Sarzi-Puttini P. Sex hormone concentrations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are not normalized during 12 weeks of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. J Rheumatol (2005) 32(7):1253–8.

64. Straub RH, Vogl D, Gross V, Lang B, Scholmerich J, Andus T. Association of humoral markers of inflammation and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate or cortisol serum levels in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol (1998) 93(11):2197–202. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00535.x

65. Da Silva JA. Sex hormones and glucocorticoids: interactions with the immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1999) 876:102–17; discussion 17–8. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07628.x

66. Barczyk K, Ehrchen J, Tenbrock K, Ahlmann M, Kneidl J, Viemann D, et al. Glucocorticoids promote survival of anti-inflammatory macrophages via stimulation of adenosine receptor A3. Blood (2010) 116(3):446–55. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-10-247106

67. Zhou JY, Zhong HJ, Yang C, Yan J, Wang HY, Jiang JX. Corticosterone exerts immunostimulatory effects on macrophages via endoplasmic reticulum stress. Br J Surg (2010) 97(2):281–93. doi:10.1002/bjs.6820

68. Migliorati G, Nicoletti I, D’Adamio F, Spreca A, Pagliacci C, Riccardi C. Dexamethasone induces apoptosis in mouse natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunology (1994) 81(1):21–6.

69. Brokaw JJ, White GW, Baluk P, Anderson GP, Umemoto EY, McDonald DM. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of dendritic cells in the rat tracheal mucosa. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (1998) 19(4):598–605. doi:10.1165/ajrcmb.19.4.2870

70. Kim KD, Choe YK, Choe IS, Lim JS. Inhibition of glucocorticoid-mediated, caspase-independent dendritic cell death by CD40 activation. J Leukoc Biol (2001) 69(3):426–34.

71. Cao Y, Bender IK, Konstantinidis AK, Shin SC, Jewell CM, Cidlowski JA, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor translational isoforms underlie maturational stage-specific glucocorticoid sensitivities of dendritic cells in mice and humans. Blood (2013) 121(9):1553–62. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-05-432336

72. Meagher LC, Cousin JM, Seckl JR, Haslett C. Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on the rate of apoptosis in neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes. J Immunol (1996) 156(11):4422–8.

73. Saffar AS, Ashdown H, Gounni AS. The molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoids-mediated neutrophil survival. Curr Drug Targets (2011) 12(4):556–62. doi:10.2174/138945011794751555

74. Jilma B, Eichler HG, Breiteneder H, Wolzt M, Aringer M, Graninger W, et al. Effects of 17 beta-estradiol on circulating adhesion molecules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1994) 79(6):1619–24. doi:10.1210/jcem.79.6.7527406

75. Robinson DP, Hall OJ, Nilles TL, Bream JH, Klein SL. 17beta-estradiol protects females against influenza by recruiting neutrophils and increasing virus-specific CD8 T cell responses in the lungs. J Virol (2014) 88(9):4711–20. doi:10.1128/JVI.02081-13

76. Baschant U, Tuckermann J. The role of the glucocorticoid receptor in inflammation and immunity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (2010) 120(2–3):69–75. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.058

77. Perretti M, Flower RJ. Measurement of lipocortin 1 levels in murine peripheral blood leukocytes by flow cytometry: modulation by glucocorticoids and inflammation. Br J Pharmacol (1996) 118(3):605–10. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15444.x

78. Shah S, King EM, Chandrasekhar A, Newton R. Roles for the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase, DUSP1, in feedback control of inflammatory gene expression and repression by dexamethasone. J Biol Chem (2014) 289(19):13667–79. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.540799

79. Cho H, Park OH, Park J, Ryu I, Kim J, Ko J, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor interacts with PNRC2 in a ligand-dependent manner to recruit UPF1 for rapid mRNA degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2015) 112(13):E1540–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1409612112

80. Nakagawa M, Bondy GP, Waisman D, Minshall D, Hogg JC, van Eeden SF. The effect of glucocorticoids on the expression of L-selectin on polymorphonuclear leukocyte. Blood (1999) 93(8):2730–7.

81. Caramori G, Adcock I. Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of glucocorticoids targeting granulocytes. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy (2005) 4(4):455–63. doi:10.2174/1568010054526331

82. Ricci E, Ronchetti S, Pericolini E, Gabrielli E, Cari L, Gentili M, et al. Role of the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper gene in dexamethasone-induced inhibition of mouse neutrophil migration via control of annexin A1 expression. FASEB J (2017) 31(7):3054–65. doi:10.1096/fj.201601315R

83. Nadkarni S, McArthur S. Oestrogen and immunomodulation: new mechanisms that impact on peripheral and central immunity. Curr Opin Pharmacol (2013) 13(4):576–81. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.007

84. MacNeil LG, Baker SK, Stevic I, Tarnopolsky MA. 17beta-estradiol attenuates exercise-induced neutrophil infiltration in men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol (2011) 300(6):R1443–51. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00689.2009

85. Chandrasekaran VR, Periasamy S, Liu LL, Liu MY. 17beta-Estradiol protects against acetaminophen-overdose-induced acute oxidative hepatic damage and increases the survival rate in mice. Steroids (2011) 76(1–2):118–24. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2010.09.008

86. Sheh A, Ge Z, Parry NM, Muthupalani S, Rager JE, Raczynski AR, et al. 17beta-Estradiol and tamoxifen prevent gastric cancer by modulating leukocyte recruitment and oncogenic pathways in Helicobacter pylori-infected INS-GAS male mice. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) (2011) 4(9):1426–35. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0219

87. Shih HC, Huang MS, Lee CH. Estrogen augments the protection of hypertonic saline treatment from mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock (2011) 35(3):302–7. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181f8b420

88. Yang SJ, Chen HM, Hsieh CH, Hsu JT, Yeh CN, Yeh TS, et al. Akt pathway is required for oestrogen-mediated attenuation of lung injury in a rodent model of cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Injury (2011) 42(7):638–42. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2010.07.242

89. Pioli PA, Jensen AL, Weaver LK, Amiel E, Shen Z, Shen L, et al. Estradiol attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine ligand 8 production by human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol (2007) 179(9):6284–90. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6284

90. Doucet D, Badami C, Palange D, Bonitz RP, Lu Q, Xu DZ, et al. Estrogen receptor hormone agonists limit trauma hemorrhage shock-induced gut and lung injury in rats. PLoS One (2010) 5(2):e9421. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009421

91. Xing D, Gong K, Feng W, Nozell SE, Chen YF, Chatham JC, et al. O-GlcNAc modification of NFkappaB p65 inhibits TNF-alpha-induced inflammatory mediator expression in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. PLoS One (2011) 6(8):e24021. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024021

92. Golecka-Bakowska M, Mierzwinska-Nastalska E, Bychawska M. Influence of hormone supplementation therapy on the incidence of denture stomatitis and on chemiluminescent activity of polymorphonuclear granulocytes in blood of menopausal-aged women. Eur J Med Res (2010) 15(Suppl 2):46–9.

93. Nadkarni S, Cooper D, Brancaleone V, Bena S, Perretti M. Activation of the annexin A1 pathway underlies the protective effects exerted by estrogen in polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol (2011) 31(11):2749–59. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.235176

94. Rogers A, Eastell R. The effect of 17beta-estradiol on production of cytokines in cultures of peripheral blood. Bone (2001) 29(1):30–4. doi:10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00468-9

95. Asai K, Hiki N, Mimura Y, Ogawa T, Unou K, Kaminishi M. Gender differences in cytokine secretion by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: role of estrogen in modulating LPS-induced cytokine secretion in an ex vivo septic model. Shock (2001) 16(5):340–3. doi:10.1097/00024382-200116050-00003

96. Toyoda Y, Miyashita T, Endo S, Tsuneyama K, Fukami T, Nakajima M, et al. Estradiol and progesterone modulate halothane-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Lett (2011) 204(1):17–24. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.03.031

97. Murphy AJ, Guyre PM, Pioli PA. Estradiol suppresses NF-kappa B activation through coordinated regulation of let-7a and miR-125b in primary human macrophages. J Immunol (2010) 184(9):5029–37. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0903463

98. Hsu JT, Kan WH, Hsieh CH, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, et al. Mechanism of estrogen-mediated attenuation of hepatic injury following trauma-hemorrhage: Akt-dependent HO-1 up-regulation. J Leukoc Biol (2007) 82(4):1019–26. doi:10.1189/jlb.0607355

99. Cuzzocrea S, Genovese T, Mazzon E, Esposito E, Di Paola R, Muia C, et al. Effect of 17beta-estradiol on signal transduction pathways and secondary damage in experimental spinal cord trauma. Shock (2008) 29(3):362–71. doi:10.1097/shk.0b013e31814545dc

100. Woltman AM, de Fijter JW, Kamerling SW, Paul LC, Daha MR, van Kooten C. The effect of calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids on the differentiation of human dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol (2000) 30(7):1807–12. doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200007)30:7<1807::AID-IMMU1807>3.0.CO;2-N

101. Chen L, Hasni MS, Jondal M, Yakimchuk K. Modification of anti-tumor immunity by tolerogenic dendritic cells. Autoimmunity (2017) 50(6):370–6. doi:10.1080/08916934.2017.1344837

102. Bros M, Jahrling F, Renzing A, Wiechmann N, Dang NA, Sutter A, et al. A newly established murine immature dendritic cell line can be differentiated into a mature state, but exerts tolerogenic function upon maturation in the presence of glucocorticoid. Blood (2007) 109(9):3820–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-07-035576

103. Vanderheyde N, Verhasselt V, Goldman M, Willems F. Inhibition of human dendritic cell functions by methylprednisolone. Transplantation (1999) 67(10):1342–7. doi:10.1097/00007890-199905270-00009

104. Seillet C, Rouquie N, Foulon E, Douin-Echinard V, Krust A, Chambon P, et al. Estradiol promotes functional responses in inflammatory and steady-state dendritic cells through differential requirement for activation function-1 of estrogen receptor alpha. J Immunol (2013) 190(11):5459–70. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1203312

105. Siracusa MC, Overstreet MG, Housseau F, Scott AL, Klein SL. 17beta-estradiol alters the activity of conventional and IFN-producing killer dendritic cells. J Immunol (2008) 180(3):1423–31. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1423

106. Cunningham MA, Naga OS, Eudaly JG, Scott JL, Gilkeson GS. Estrogen receptor alpha modulates toll-like receptor signaling in murine lupus. Clin Immunol (2012) 144(1):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2012.04.001

107. Douin-Echinard V, Laffont S, Seillet C, Delpy L, Krust A, Chambon P, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha, but not beta, is required for optimal dendritic cell differentiation and [corrected] CD40-induced cytokine production. J Immunol (2008) 180(6):3661–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3661

108. Delpy L, Douin-Echinard V, Garidou L, Bruand C, Saoudi A, Guery JC. Estrogen enhances susceptibility to experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis by promoting type 1-polarized immune responses. J Immunol (2005) 175(8):5050–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5050

109. Liu HY, Buenafe AC, Matejuk A, Ito A, Zamora A, Dwyer J, et al. Estrogen inhibition of EAE involves effects on dendritic cell function. J Neurosci Res (2002) 70(2):238–48. doi:10.1002/jnr.10409

110. Bachy V, Williams DJ, Ibrahim MA. Altered dendritic cell function in normal pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol (2008) 78(1):11–21. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2007.09.004

111. Papenfuss TL, Powell ND, McClain MA, Bedarf A, Singh A, Gienapp IE, et al. Estriol generates tolerogenic dendritic cells in vivo that protect against autoimmunity. J Immunol (2011) 186(6):3346–55. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1001322

112. Subramanian S, Yates M, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Oestrogen-mediated protection of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the absence of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells implicates compensatory pathways including regulatory B cells. Immunology (2011) 132(3):340–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03380.x

113. Brewer JA, Kanagawa O, Sleckman BP, Muglia LJ. Thymocyte apoptosis induced by T cell activation is mediated by glucocorticoids in vivo. J Immunol (2002) 169(4):1837–43. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1837

114. Vacchio MS, Ashwell JD. Glucocorticoids and thymocyte development. Semin Immunol (2000) 12(5):475–85. doi:10.1006/smim.2000.0265

115. Caron-Leslie LM, Schwartzman RA, Gaido ML, Compton MM, Cidlowski JA. Identification and characterization of glucocorticoid-regulated nuclease(s) in lymphoid cells undergoing apoptosis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (1991) 40(4–6):661–71. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(91)90288-G

116. Brunetti M, Martelli N, Colasante A, Piantelli M, Musiani P, Aiello FB. Spontaneous and glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in human mature T lymphocytes. Blood (1995) 86(11):4199–205.

117. Stephens GL, Ignatowicz L. Decreasing the threshold for thymocyte activation biases CD4+ T cells toward a regulatory (CD4+CD25+) lineage. Eur J Immunol (2003) 33(5):1282–91. doi:10.1002/eji.200323927

118. Cohen JJ, Duke RC. Glucocorticoid activation of a calcium-dependent endonuclease in thymocyte nuclei leads to cell death. J Immunol (1984) 132(1):38–42.

119. Wyllie AH. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation. Nature (1980) 284(5756):555–6. doi:10.1038/284555a0

120. Ashwell JD, Lu FW, Vacchio MS. Glucocorticoids in T cell development and function*. Annu Rev Immunol (2000) 18:309–45. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.309

121. Van Laethem F, Baus E, Smyth LA, Andris F, Bex F, Urbain J, et al. Glucocorticoids attenuate T cell receptor signaling. J Exp Med (2001) 193(7):803–14. doi:10.1084/jem.193.7.803

122. Chen Y, Qiao S, Tuckermann J, Okret S, Jondal M. Thymus-derived glucocorticoids mediate androgen effects on thymocyte homeostasis. FASEB J (2010) 24(12):5043–51. doi:10.1096/fj.10-168724

123. Aboussaouira T, Marie C, Brugal G, Idelman S. Inhibitory effect of 17 beta-estradiol on thymocyte proliferation and metabolic activity in young rats. Thymus (1991) 17(3):167–80.

124. Okuyama R, Abo T, Seki S, Ohteki T, Sugiura K, Kusumi A, et al. Estrogen administration activates extrathymic T cell differentiation in the liver. J Exp Med (1992) 175(3):661–9. doi:10.1084/jem.175.3.661

125. Phuc LH, Papiernik M, Berrih S, Duval D. Thymic involution in pregnant mice. I. Characterization of the remaining thymocyte subpopulations. Clin Exp Immunol (1981) 44(2):247–52.

126. Phuc LH, Papiernik M, Dardenne M. Thymic involution in pregnant mice. II. Functional aspects of the remaining thymocytes. Clin Exp Immunol (1981) 44(2):253–61.

127. Olsen NJ, Viselli SM, Shults K, Stelzer G, Kovacs WJ. Induction of immature thymocyte proliferation after castration of normal male mice. Endocrinology (1994) 134(1):107–13. doi:10.1210/endo.134.1.8275924

128. Britanova OV, Shugay M, Merzlyak EM, Staroverov DB, Putintseva EV, Turchaninova MA, et al. Dynamics of individual T cell repertoires: from cord blood to centenarians. J Immunol (2016) 196(12):5005–13. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1600005

129. Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*). Annu Rev Immunol (2010) 28:445–89. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212

130. Elenkov IJ. Glucocorticoids and the Th1/Th2 balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2004) 1024:138–46. doi:10.1196/annals.1321.010

131. Refojo D, Liberman AC, Giacomini D, Carbia Nagashima A, Graciarena M, Echenique C, et al. Integrating systemic information at the molecular level: cross-talk between steroid receptors and cytokine signaling on different target cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2003) 992:196–204. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03150.x

132. Almawi WY, Melemedjian OK, Rieder MJ. An alternate mechanism of glucocorticoid anti-proliferative effect: promotion of a Th2 cytokine-secreting profile. Clin Transplant (1999) 13(5):365–74. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130501.x

133. Liberman AC, Refojo D, Druker J, Toscano M, Rein T, Holsboer F, et al. The activated glucocorticoid receptor inhibits the transcription factor T-bet by direct protein-protein interaction. FASEB J (2007) 21(4):1177–88. doi:10.1096/fj.06-7452com

134. Liu M, Hu X, Wang Y, Peng F, Yang Y, Chen X, et al. Effect of high-dose methylprednisolone treatment on Th17 cells in patients with multiple sclerosis in relapse. Acta Neurol Scand (2009) 120(4):235–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01158.x

135. Banuelos J, Cao Y, Shin SC, Lu NZ. Immunopathology alters Th17 cell glucocorticoid sensitivity. Allergy (2017) 72(3):331–41. doi:10.1111/all.13051

136. Bereshchenko O, Coppo M, Bruscoli S, Biagioli M, Cimino M, Frammartino T, et al. GILZ promotes production of peripherally induced Treg cells and mediates the crosstalk between glucocorticoids and TGF-beta signaling. Cell Rep (2014) 7(2):464–75. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.004

137. Ugor E, Prenek L, Pap R, Berta G, Ernszt D, Najbauer J, et al. Glucocorticoid hormone treatment enhances the cytokine production of regulatory T cells by upregulation of Foxp3 expression. Immunobiology (2018) 223(4–5):422–31. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2017.10.010

138. Chen X, Oppenheim JJ, Winkler-Pickett RT, Ortaldo JR, Howard OM. Glucocorticoid amplifies IL-2-dependent expansion of functional FoxP3(+)CD4(+)CD25(+) T regulatory cells in vivo and enhances their capacity to suppress EAE. Eur J Immunol (2006) 36(8):2139–49. doi:10.1002/eji.200635873

139. Chung IY, Dong HF, Zhang X, Hassanein NM, Howard OM, Oppenheim JJ, et al. Effects of IL-7 and dexamethasone: induction of CD25, the high affinity IL-2 receptor, on human CD4+ cells. Cell Immunol (2004) 232(1–2):57–63. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.01.011

140. Stary G, Klein I, Bauer W, Koszik F, Reininger B, Kohlhofer S, et al. Glucocorticosteroids modify Langerhans cells to produce TGF-beta and expand regulatory T cells. J Immunol (2011) 186(1):103–12. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1002485

141. Suarez A, Lopez P, Gomez J, Gutierrez C. Enrichment of CD4+ CD25high T cell population in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis (2006) 65(11):1512–7. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.049924

142. de Paz B, Alperi-Lopez M, Ballina-Garcia FJ, Prado C, Gutierrez C, Suarez A. Cytokines and regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis and their relationship with response to corticosteroids. J Rheumatol (2010) 37(12):2502–10. doi:10.3899/jrheum.100324

143. Hu Y, Tian W, Zhang LL, Liu H, Yin GP, He BS, et al. Function of regulatory T-cells improved by dexamethasone in Graves’ disease. Eur J Endocrinol (2012) 166(4):641–6. doi:10.1530/EJE-11-0879

144. Cannarile L, Cuzzocrea S, Santucci L, Agostini M, Mazzon E, Esposito E, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper is protective in Th1-mediated models of colitis. Gastroenterology (2009) 136(2):530–41. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.024

145. Cannarile L, Fallarino F, Agostini M, Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Vacca C, et al. Increased GILZ expression in transgenic mice up-regulates Th-2 lymphokines. Blood (2006) 107(3):1039–47. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-05-2183

146. Lelu K, Laffont S, Delpy L, Paulet PE, Perinat T, Tschanz SA, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha signaling in T lymphocytes is required for estradiol-mediated inhibition of Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation and protection against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (2011) 187(5):2386–93. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101578

147. Priyanka HP, Krishnan HC, Singh RV, Hima L, Thyagarajan S. Estrogen modulates in vitro T cell responses in a concentration- and receptor-dependent manner: effects on intracellular molecular targets and antioxidant enzymes. Mol Immunol (2013) 56(4):328–39. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2013.05.226

148. Karpuzoglu-Sahin E, Zhi-Jun Y, Lengi A, Sriranganathan N, Ansar Ahmed S. Effects of long-term estrogen treatment on IFN-gamma, IL-2 and IL-4 gene expression and protein synthesis in spleen and thymus of normal C57BL/6 mice. Cytokine (2001) 14(4):208–17. doi:10.1006/cyto.2001.0876

149. Grasso G, Muscettola M. The influence of beta-estradiol and progesterone on interferon gamma production in vitro. Int J Neurosci (1990) 51(3–4):315–7. doi:10.3109/00207459008999730

150. Fox HS, Bond BL, Parslow TG. Estrogen regulates the IFN-gamma promoter. J Immunol (1991) 146(12):4362–7.

151. Karpuzoglu-Sahin E, Hissong BD, Ansar Ahmed S. Interferon-gamma levels are upregulated by 17-beta-estradiol and diethylstilbestrol. J Reprod Immunol (2001) 52(1–2):113–27. doi:10.1016/S0165-0378(01)00117-6

152. Maret A, Coudert JD, Garidou L, Foucras G, Gourdy P, Krust A, et al. Estradiol enhances primary antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses and Th1 development in vivo. Essential role of estrogen receptor alpha expression in hematopoietic cells. Eur J Immunol (2003) 33(2):512–21. doi:10.1002/immu.200310027

153. Karpuzoglu E, Phillips RA, Gogal RM Jr, Ansar Ahmed S. IFN-gamma-inducing transcription factor, T-bet is upregulated by estrogen in murine splenocytes: role of IL-27 but not IL-12. Mol Immunol (2007) 44(7):1808–14. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2006.08.005

154. Dai R, Phillips RA, Zhang Y, Khan D, Crasta O, Ahmed SA. Suppression of LPS-induced interferon-gamma and nitric oxide in splenic lymphocytes by select estrogen-regulated microRNAs: a novel mechanism of immune modulation. Blood (2008) 112(12):4591–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-04-152488

155. Marzi M, Vigano A, Trabattoni D, Villa ML, Salvaggio A, Clerici E, et al. Characterization of type 1 and type 2 cytokine production profile in physiologic and pathologic human pregnancy. Clin Exp Immunol (1996) 106(1):127–33. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-809.x

156. Matalka KZ. The effect of estradiol, but not progesterone, on the production of cytokines in stimulated whole blood, is concentration-dependent. Neuro Endocrinol Lett (2003) 24(3–4):185–91.

157. Sabahi F, Rola-Plesczcynski M, O’Connell S, Frenkel LD. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of T lymphocytes during normal human pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol (1995) 33(5):381–93. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1995.tb00907.x

158. Lou Y, Hu M, Wang Q, Yuan M, Wang N, Le F, et al. Estradiol suppresses TLR4-triggered apoptosis of decidual stromal cells and drives an anti-inflammatory TH2 shift by activating SGK1. Int J Biol Sci (2017) 13(4):434–48. doi:10.7150/ijbs.18278

159. Konermann A, Winter J, Novak N, Allam JP, Jager A. Verification of IL-17A and IL-17F in oral tissues and modulation of their expression pattern by steroid hormones. Cell Immunol (2013) 285(1–2):133–40. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.10.004

160. Wang Y, Cela E, Gagnon S, Sweezey NB. Estrogen aggravates inflammation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in cystic fibrosis mice. Respir Res (2010) 11:166. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-11-166

161. Molnar I, Bohaty I, Somogyine-Vari E. High prevalence of increased interleukin-17A serum levels in postmenopausal estrogen deficiency. Menopause (2014) 21(7):749–52. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000125

162. Polanczyk MJ, Hopke C, Huan J, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Enhanced FoxP3 expression and Treg cell function in pregnant and estrogen-treated mice. J Neuroimmunol (2005) 170(1–2):85–92. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.08.023

163. Tai P, Wang J, Jin H, Song X, Yan J, Kang Y, et al. Induction of regulatory T cells by physiological level estrogen. J Cell Physiol (2008) 214(2):456–64. doi:10.1002/jcp.21221

164. Adurthi S, Kumar MM, Vinodkumar HS, Mukherjee G, Krishnamurthy H, Acharya KK, et al. Oestrogen receptor-alpha binds the FOXP3 promoter and modulates regulatory T-cell function in human cervical cancer. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):17289. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-17102-w

165. Polanczyk MJ, Carson BD, Subramanian S, Afentoulis M, Vandenbark AA, Ziegler SF, et al. Cutting edge: estrogen drives expansion of the CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell compartment. J Immunol (2004) 173(4):2227–30. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2227

166. Polanczyk MJ, Hopke C, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Treg suppressive activity involves estrogen-dependent expression of programmed death-1 (PD-1). Int Immunol (2007) 19(3):337–43. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxl151

167. Gruver-Yates AL, Quinn MA, Cidlowski JA. Analysis of glucocorticoid receptors and their apoptotic response to dexamethasone in male murine B cells during development. Endocrinology (2014) 155(2):463–74. doi:10.1210/en.2013-1473

168. Lill-Elghanian D, Schwartz K, King L, Fraker P. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in early B cells from human bone marrow. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) (2002) 227(9):763–70. doi:10.1177/153537020222700907

169. Smith LK, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of healthy and malignant lymphocytes. Prog Brain Res (2010) 182:1–30. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(10)82001-1

170. Bruscoli S, Biagioli M, Sorcini D, Frammartino T, Cimino M, Sportoletti P, et al. Lack of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) deregulates B-cell survival and results in B-cell lymphocytosis in mice. Blood (2015) 126(15):1790–801. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-03-631580

171. Barnes PJ. Corticosteroids, IgE, and atopy. J Clin Invest (2001) 107(3):265–6. doi:10.1172/JCI12157

172. Jabara HH, Brodeur SR, Geha RS. Glucocorticoids upregulate CD40 ligand expression and induce CD40L-dependent immunoglobulin isotype switching. J Clin Invest (2001) 107(3):371–8. doi:10.1172/JCI10168

173. Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu Rev Physiol (2005) 67:259–84. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120816

174. Bynoe MS, Grimaldi CM, Diamond B. Estrogen up-regulates Bcl-2 and blocks tolerance induction of naive B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2000) 97(6):2703–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.040577497

175. Grimaldi CM, Michael DJ, Diamond B. Cutting edge: expansion and activation of a population of autoreactive marginal zone B cells in a model of estrogen-induced lupus. J Immunol (2001) 167(4):1886–90. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1886

176. Grimaldi CM, Cleary J, Dagtas AS, Moussai D, Diamond B. Estrogen alters thresholds for B cell apoptosis and activation. J Clin Invest (2002) 109(12):1625–33. doi:10.1172/JCI0214873

177. Grimaldi CM, Jeganathan V, Diamond B. Hormonal regulation of B cell development: 17 beta-estradiol impairs negative selection of high-affinity DNA-reactive B cells at more than one developmental checkpoint. J Immunol (2006) 176(5):2703–10. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2703

178. Klose CS, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol (2016) 17(7):765–74. doi:10.1038/ni.3489

179. Bartemes K, Chen CC, Iijima K, Drake L, Kita H. IL-33-responsive group 2 innate lymphoid cells are regulated by female sex hormones in the uterus. J Immunol (2018) 200(1):229–36. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1602085

180. Li BW, Hendriks RW. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells in lung inflammation. Immunology (2013) 140(3):281–7. doi:10.1111/imm.12153

181. Laffont S, Blanquart E, Savignac M, Cenac C, Laverny G, Metzger D, et al. Androgen signaling negatively controls group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J Exp Med (2017) 214(6):1581–92. doi:10.1084/jem.20161807

182. Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science (1988) 240(4854):889–95. doi:10.1126/science.3283939

183. Nilsson S, Makela S, Treuter E, Tujague M, Thomsen J, Andersson G, et al. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol Rev (2001) 81(4):1535–65. doi:10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1535

184. Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL, Scanlan TS, Shiau AK, Uht RM, et al. Estrogen receptor pathways to AP-1. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (2000) 74(5):311–7. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00108-4

185. Kerppola TK, Luk D, Curran T. Fos is a preferential target of glucocorticoid receptor inhibition of AP-1 activity in vitro. Mol Cell Biol (1993) 13(6):3782–91. doi:10.1128/MCB.13.6.3782

186. Safe S. Transcriptional activation of genes by 17 beta-estradiol through estrogen receptor-Sp1 interactions. Vitam Horm (2001) 62:231–52. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(01)62006-5

187. Ou XM, Chen K, Shih JC. Glucocorticoid and androgen activation of monoamine oxidase A is regulated differently by R1 and Sp1. J Biol Chem (2006) 281(30):21512–25. doi:10.1074/jbc.M600250200

188. Wyszomierski SL, Yeh J, Rosen JM. Glucocorticoid receptor/signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) interactions enhance STAT5 activation by prolonging STAT5 DNA binding and tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol Endocrinol (1999) 13(2):330–43. doi:10.1210/mend.13.2.0232

189. Biswas DK, Singh S, Shi Q, Pardee AB, Iglehart JD. Crossroads of estrogen receptor and NF-kappaB signaling. Sci STKE (2005) 2005(288):pe27. doi:10.1126/stke.2882005pe27

190. McKay LI, Cidlowski JA. Cross-talk between nuclear factor-kappa B and the steroid hormone receptors: mechanisms of mutual antagonism. Mol Endocrinol (1998) 12(1):45–56. doi:10.1210/me.12.1.45

191. Bolt MJ, Stossi F, Newberg JY, Orjalo A, Johansson HE, Mancini MA. Coactivators enable glucocorticoid receptor recruitment to fine-tune estrogen receptor transcriptional responses. Nucleic Acids Res (2013) 41(7):4036–48. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt100

192. Gong H, Jarzynka MJ, Cole TJ, Lee JH, Wada T, Zhang B, et al. Glucocorticoids antagonize estrogens by glucocorticoid receptor-mediated activation of estrogen sulfotransferase. Cancer Res (2008) 68(18):7386–93. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1545

193. Karmakar S, Jin Y, Nagaich AK. Interaction of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) with estrogen receptor (ER) alpha and activator protein 1 (AP1) in dexamethasone-mediated interference of ERalpha activity. J Biol Chem (2013) 288(33):24020–34. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.473819

194. Uht RM, Anderson CM, Webb P, Kushner PJ. Transcriptional activities of estrogen and glucocorticoid receptors are functionally integrated at the AP-1 response element. Endocrinology (1997) 138(7):2900–8. doi:10.1210/endo.138.7.5244

195. Kinyamu HK, Archer TK. Estrogen receptor-dependent proteasomal degradation of the glucocorticoid receptor is coupled to an increase in mdm2 protein expression. Mol Cell Biol (2003) 23(16):5867–81. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.16.5867-5881.2003

196. Cuzzocrea S, Bruscoli S, Crisafulli C, Mazzon E, Agostini M, Muia C, et al. Estrogen receptor antagonist fulvestrant (ICI 182,780) inhibits the anti-inflammatory effect of glucocorticoids. Mol Pharmacol (2007) 71(1):132–44. doi:10.1124/mol.106.029629

197. Cvoro A, Yuan C, Paruthiyil S, Miller OH, Yamamoto KR, Leitman DC. Cross talk between glucocorticoid and estrogen receptors occurs at a subset of proinflammatory genes. J Immunol (2011) 186(7):4354–60. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1002205

198. Lei K, Chen L, Georgiou EX, Sooranna SR, Khanjani S, Brosens JJ, et al. Progesterone acts via the nuclear glucocorticoid receptor to suppress IL-1beta-induced COX-2 expression in human term myometrial cells. PLoS One (2012) 7(11):e50167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050167

199. Demirpence E, Semlali A, Oliva J, Balaguer P, Badia E, Duchesne MJ, et al. An estrogen-responsive element-targeted histone deacetylase enzyme has an antiestrogen activity that differs from that of hydroxytamoxifen. Cancer Res (2002) 62(22):6519–28.

Keywords: glucocorticoids, sex hormones, innate immunity, adaptive immunity, glucocorticoid receptor, estrogen receptor alpha

Citation: Bereshchenko O, Bruscoli S and Riccardi C (2018) Glucocorticoids, Sex Hormones, and Immunity. Front. Immunol. 9:1332. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01332

Received: 30 March 2018; Accepted: 29 May 2018;

Published: 12 June 2018

Edited by:

Marina Pierdominici, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ItalyReviewed by:

Roberto Paganelli, Università degli Studi G. d’Annunzio Chieti e Pescara, ItalySilvia Piconese, Sapienza Università di Roma, Italy

Copyright: © 2018 Bereshchenko, Bruscoli and Riccardi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlo Riccardi, Y2FybG8ucmljY2FyZGlAdW5pcGcuaXQ=

Oxana Bereshchenko

Oxana Bereshchenko Stefano Bruscoli

Stefano Bruscoli Carlo Riccardi

Carlo Riccardi