95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 04 April 2018

Sec. Microbial Immunology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00667

This article is part of the Research Topic Integrative Computational Systems Biology Approaches in Immunology and Medicine View all 24 articles

Sandra Timme1,2

Sandra Timme1,2 Teresa Lehnert1,3

Teresa Lehnert1,3 Maria T. E. Prauße1,2

Maria T. E. Prauße1,2 Kerstin Hünniger4,5

Kerstin Hünniger4,5 Ines Leonhardt3,4

Ines Leonhardt3,4 Oliver Kurzai3,4,5

Oliver Kurzai3,4,5 Marc Thilo Figge1,2,3*

Marc Thilo Figge1,2,3*

The condition of neutropenia, i.e., a reduced absolute neutrophil count in blood, constitutes a major risk factor for severe infections in the affected patients. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata are opportunistic pathogens and the most prevalent fungal species in the human microbiota. In immunocompromised patients, they can become pathogenic and cause infections with high mortality rates. In this study, we use a previously established approach that combines experiments and computational models to investigate the innate immune response during blood stream infections with the two fungal pathogens C. albicans and C. glabrata. First, we determine immune-reaction rates and migration parameters under healthy conditions. Based on these findings, we simulate virtual patients and investigate the impact of neutropenic conditions on the infection outcome with the respective pathogen. Furthermore, we perform in silico treatments of these virtual patients by simulating a medical treatment that enhances neutrophil activity in terms of phagocytosis and migration. We quantify the infection outcome by comparing the response to the two fungal pathogens relative to non-neutropenic individuals. The analysis reveals that these fungal infections in neutropenic patients can be successfully cleared by cytokine treatment of the remaining neutrophils; and that this treatment is more effective for C. glabrata than for C. albicans.

The human immune system protects the body against various environmental cues, such as microorganisms. It covers mechanisms on different levels ranging from physical barriers, like the skin and mucosal surfaces, down to cellular and molecular components of the innate and adaptive immune system (1). However, congenital or acquired diseases as well as medical treatments may impair proper functioning of the immune system, which can result in the loss of its protective ability. Neutrophils constitute the highest fraction of blood leukocytes, as they make up over 70% of all blood leukocytes (2). Since they can migrate to sites of infection and clear the organism from pathogens, they constitute an important part of the immune system.

Candida spp. cause 5–15% of all bloodstream infections and are associated with high mortality rates of 30–40% (3). A significant proportion (>50%, depending on the study setting) of the human population is colonized with Candida spp. The most prevalent species are Candida albicans and Candida glabrata that are both human commensals and reside predominantly on the human skin and mucosal surfaces (4–6). C. albicans is a morphotype-switching yeast, which in its commensal state exhibits the typical yeast form, while it forms hyphae when switching to its pathogenic state (7, 8). By contrast, C. glabrata does not form hyphae, neither in the commensal nor in the pathogenic state and is smaller than C. albicans (4, 9). In healthy people, both species usually stay in their commensal state. However, in immunocompromised patients, these human-pathogenic fungi can switch to their pathogenic state and cause superficial as well as systemic infections that are associated with high mortality rates.

To investigate host–pathogen interactions between the human innate immune system and these fungal pathogens, we applied a systems biology approach, where wet-lab experiments were combined with virtual infection models (10–13). Such virtual infection models have the great advantage of allowing for the identification and quantification of essential parameters that govern the biological system under consideration. This also makes them a powerful tool for hypothesis generation and uncovering new mechanisms, which consequently allows for minimizing the amount of animal experiments (14). Depending on the purpose, such in silico models can be built with different modeling techniques, such as differential equations, state-based models (SBMs) or spatial modeling techniques such as cellular automata, cellular Potts models or agent-based models (ABMs) (15). In a previous systems biology study, we established a human whole-blood infection assay (16), where blood was taken from healthy volunteers and infected with C. albicans cells. Then, subpopulations of alive, killed and extracellular fungal cells as well as fungal cells phagocytosed by monocytes and neutrophils were measured by association assays and survival assays. Based on these experimental data, we implemented an SBM that allowed for the quantification of immune-reaction rates, such as phagocytosis and killing rates, by fitting the simulated kinetics to the experimental data. In a subsequent study, we developed a bottom-up modeling approach that enabled not only quantification of immune-reaction rates but also the investigation of spatial aspects (17). Since the SBM simulates the temporal but not the spatial dynamics, we also developed an ABM that was based on a previous ABM implementation (18, 19). We combined both models in a bottom-up modeling approach (17): the SBM was used to determine non-spatial rates that were afterward transformed and used in the ABM to fit migration parameters of immune cells in human whole blood. We found that the in silico infection outcome for C. albicans was sensitive to changes in the diffusion coefficient of neutrophils, whereas that of monocytes had only minor impact on the system dynamics. This result reflected the more prominent role of neutrophils over monocytes in fighting C. albicans infection of human whole blood. Furthermore, immune dysregulation was investigated using the ABM, and the results showed that a reduced diffusion coefficient for neutrophils resembled conditions of neutropenia (17). This important observation is the main motivation of the present study, because it suggests how neutropenic patients may be treated to cope with bloodstream infections. Thus, increasing neutrophil activation in terms of phagocytic activity as well as migration strength is hypothesized to have the potential of balancing neutropenic conditions and clearance of infection. Based on this reasoning, we address infections in human whole blood by C. albicans and C. glabrata under neutropenic conditions in this study.

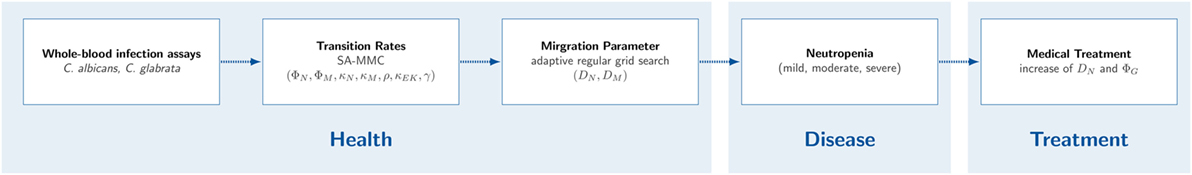

Diseases or medical treatments can evoke a reduced absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in blood and result into a condition called neutropenia. Neutropenia may result from congenital or acquired impairments, where the latter case is more frequent. A reduced ANC may arise due to a disturbed development of neutrophils in the bone marrow, a disturbed migration to the blood stream or a rapid consumption during an infection (20). In anti-cancer chemotherapy, neutropenia is the most abundant disorder of the immune system due to the relatively short life-span of these terminally differentiated cells (21). Neutropenia emerges in different degrees of severity that are classified by the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry (SCNIR) (20). The SCNIR distinguishes three degrees of severity: mild neutropenia with an ANC of 1,000–1,500 neutrophils/μl, moderate neutropenia with an ANC of 500–1,000 neutrophils/μl and severe neutropenia with an ANC of <500 neutrophils/μl. In this study, we focus on neutropenia treatment by stimulation and activation of present neutrophils by inflammatory cytokines and quantitatively investigate the impact on fungal infections by computer simulations. Thus, we aim to investigate a possible treatment strategy where the neutrophil activity is increased by a higher diffusion coefficient and/or phagocytosis rate. For this purpose, we apply the previously established protocol for whole-blood infection assays and perform the bottom-up modeling approach for the two human-pathogenic fungi. As is schematically shown in Figure 1, we first determine quantitative values for the immune-reaction rates as well as for diffusion coefficients of monocytes and neutrophils as the key immune cells of innate immunity in whole blood. Furthermore, we use this modeling approach to simulate neutropenia in silico and compare effects on the infection outcome between the different pathogens. To evaluate a possible treatment strategy, we simulate virtual neutropenic patients (VNP) with different degrees of severity and increase stepwise the phagocytosis rate and/or the diffusion coefficient of neutrophils to classify the infection outcome. Taken together, we could show that the increase of the phagocytosis rate and/or the migration parameter of neutrophils generally allowed balancing neutropenic conditions and clearance of infection. Furthermore, we predict that C. albicans compared with C. glabrata always requires stronger increases in the phagocytosis rate and the diffusion coefficient for the same conditions of neutropenia.

Figure 1. Workflow for studying neutropenia in silico. First, whole-blood infection assays with Candida albicans and Candida glabrata were performed in wet lab. Second, non-spatial immune-reaction rates were fitted using the state-based model. Third, the agent-based model (ABM) was used to estimate migration parameters for neutrophils and monocytes. Based on the fitted non-spatial immune-reaction rates and the fitted migration parameters, virtual neutropenic patients were simulated in the ABM by gradually reducing the neutrophil count. Eventually, a medical treatment of the virtual patients was simulated by increasing the diffusion coefficient and/or the phagocytosis rate of neutrophils.

This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Jena (permit number: 273-12/09). Written informed consent was obtained from all blood donors.

GFP expressing C. albicans strain [constructed as described in Ref. (16)] was grown in liquid yeast extract–peptone–dextrose (YPD) medium at 30°C. C. glabrata expressing GFP (22) was incubated at 37°C in YPD. In preparation for the whole-blood assay, both strains were reseeded after overnight culture in YPD medium and grown at 30 and 37°C, respectively, until they reached the mid-log-phase and finally harvested in HBSS until use.

Human peripheral blood from healthy individuals was infected with either of the two fungi C. albicans and C. glabrata, respectively. The assay was performed as described previously (16). In short, 1 × 106 Candida cells were added per ml of anti-coagulated blood and incubated at 37°C with gentle rotation for time points indicated. Following the incubation, cells were maintained at 4°C and analyzed immediately via flow cytometry. Flow cytometry gating strategy to investigate the distribution of fungal cells in human blood was performed as previously described (16) using FlowJo 7.6.4 software. Survival of fungal cells was determined in a plating assay by analysis of recovered colony-forming units after plating appropriate dilutions of all time points on YPD agar plates.

We established a bottom-up modeling approach for simulation and fitting of whole-blood infection assays in a previous study (17). This bottom-up modeling approach incorporates models with increasing complexity that build on one another, where each model focuses on different aspects of the infection process.

First, we applied the SBM to quantify and characterize immune-reaction rates for discrete entities of pathogens and innate immune cells. Therefore, the populations of innate immune cells, i.e., neutrophils and monocytes, as well as the pathogens were modeled by different states in the SBM. For the comparison with experimentally measured cell populations, we identified five combined units that are composed of specific states. The states representing extracellular cells are combined in the combined unit PE that is given by the following equation:

where the states PAE and PKE represent extracellular cells that are alive and killed, respectively. The states PAIE and PKIE describe pathogens that are either alive and evading the immune response or killed and evading the immune response. Pathogens that are in extracellular space and either alive (PAE) or killed (PKE) can be phagocytosed by two different immune cells, i.e., neutrophils (N) and monocytes (M). The combined unit PN comprises pathogens that are phagocytosed by neutrophils and is given by the following equation:

Similarly, pathogens that are phagocytosed by monocytes are combined in PM that is given by the following equation:

In Eqs 2 and 3, the indices i and j refer to the immune cell state that is defined by the number of internalized alive and killed pathogens, respectively.

Furthermore, the states representing alive and killed pathogens are combined in PK and PA, respectively, that are defined by the following equations:

The total number of pathogens is given by P ≡ PE + PN + PM or P ≡ PK + PA.

Transitions between these states are characterized by so-called transition rates and allow for dynamic state changes over time. The SBM of whole-blood infection comprises seven different transition rates that are given by the phagocytosis rate ϕM of monocytes, the phagocytosis rate ϕN of neutrophils, the intracellular killing rates κM and κN of both monocytes and neutrophils, the transition rates γ and , which define the extracellular killing by antimicrobial peptides, and the spontaneous immune evasion rate ρ. Note that, in the previous study by Lehnert et al. (17), a distinction between first and subsequent phagocytosis events by neutrophils was made, where the first phagocytosis event was assumed to activate the neutrophils and induce granulation. Since this fact is not experimentally validated for whole-blood infection with C. glabrata, we here did not distinguish between these two processes and used only one transition rate (ϕN) referring to both first and subsequent phagocytosis events. To determine a priori unknown transitions rates, the in silico data were fitted to the experimental data by applying the method of Simulated Annealing based on the Metropolis Monte Carlo scheme (SA-MMC). For a more detailed description of the model and the parameter estimation method, we refer to Hünniger et al. (16) and Lehnert et al. (17).

The ABM is based on a previous ABM implementation (18, 19) and was already used in the previous study by Ref. (17). In contrast to the SBM, it allows studying spatial aspects, such as immune cell migration, in whole-blood infection assays. The ABM simulates all cell types, i.e., pathogens as well as immune cells, as individual spherical objects that are referred to as agents. All agents migrate, act and interact in a rule-based fashion within a spatially continuous, three-dimensional environment that represents 1 μl of blood.

Furthermore, the ABM was fitted to the experimental data to determine diffusion coefficients of neutrophils (DN) and monocytes (DM). This was done by the bottom-up modeling approach, where the previously determined transition rates from the SBM were used in the ABM. However, space-dependent rates, like phagocytosis rates, had to be adequately transformed (17). Regarding the fitting procedure, we used an adaptive regular grid search that scans the parameter space within reasonable ranges and uses a more fine-grained grid in regions with relatively small least squares errors (LSEs).

The work flow of this study, comparing wet-lab and in silico experiments with different models is displayed in Figure 1. First, we performed whole-blood infection assays for the two fungal pathogens C. albicans and C. glabrata. Afterward, we applied for each of the two pathogens the following steps. The results from association and survival assays were used to fit the model parameters of the SBM to these data. The transition rates of the fit with the lowest LSE were then appropriately transformed and fed into the ABM. Subsequently, the grid search in the parameter space was applied to fit the ABM to the experimental data and, in this way, to estimate the diffusion coefficients of neutrophils and monocytes. The determined transition rates and migration parameters form the basis for all following investigations on neutropenia and possible treatment strategies in virtual patients with varying degree of neutropenia. In the following, each step of this work flow is described in more detail.

For the quantification of the immune response against the human-pathogenic fungi C. albicans and C. glabrata with normal neutrophil counts, we first determined the transition rates by fitting the SBM to the corresponding data from whole-blood experiments. These rates were used in the ABM and diffusion coefficients for neutrophils DN and monocytes DM were determined by fitting the ABM to the experimental data.

To examine the immune response of virtual patients under conditions of neutropenia, we performed simulations with the immune-reaction rates and migration parameters that were identified under non-neutropenic conditions and gradually decreased the number of neutrophils. Subsequently, we compared the infection outcome at 4 h post infection for varying degrees of severity of neutropenia.

Since the health of a patient is critically determined by the amount of killed pathogens PK as well as by the amount of alive and immune-evasive pathogens PAIE, we used these measures to characterize the infection outcome for the virtual patients.

We distinguish four different cases C for the infection outcome: an infection outcome corresponding to non-neutropenic immune conditions as well as the infection outcome under mild, moderate or severe neutropenia, i.e., C = {non–neutropenic, mild, moderate, severe}. To discriminate these classes, we calculated the patterns ψ = (μ(PK) ± σ(PK), μ(PAE) ± σ(PAE), μ(PAIE) ± σ(PAIE)) at the transition between consecutive degrees of neutropenia severity, in terms of the mean and SD. This resulted in the three patterns ψ = {ψnm, ψmm, ψms} at the transitions between two neutropenia severity levels: non-neutropenic–mild (nm), mild–moderate (mm), and moderate–severe (ms). For the classification of a particular simulation, we calculated the class of the values and at 4 h post infection. Then, we classified each of the three values of v(PK) = (μ(PK) + σ(PK), μ(PK), μ(PK) − σ(PK)) and v(PAIE) = (μ(PAIE) + σ(PAIE), μ(PAIE), μ(PAIE) − σ(PAIE)) separately. Thus, for each of the three values vi, we set:

The simulation’s infection outcome C is then assigned to the class that received the highest number of votes from the nine values of vi(PK) and vi(PAIE).

After the simulation of VNP, we simulated the medical treatment of these patients. Therefore, we selected virtual patients with certain degrees of severity of neutropenia. These are the number of neutrophils that are specific for a transition between two degrees of severity as well as the number of neutrophils between these transitions. Therefore, we simulate the following five VNP that are characterized by specific ANC: VNP-1 with 1,250 neutrophils/μl, VNP-2 with 1,000 neutrophils/μl, VNP-3 with 750 neutrophils/μl, VNP-4 with 500 neutrophils/μl, VNP-5 with 250 neutrophils/μl. Thus, the ANC of these VNP corresponds to a decrease in neutrophil number from the standard value by VNP-1: 75%, VNP-2: 80%, VNP-3: 85%, VNP-4: 90%, and VNP-5: 95%. Since the treatment with different drugs might improve the phagocytic activity and/or the migration parameter of neutrophils, we performed simulations with the ABM where the phagocytosis rate of neutrophils ϕN as well as their diffusion coefficient DN was increased. In the following, we refer to these parameters that are affected by the treatment as and .

For the sake of comparability of both values, we increased both values in a stepwise fashion. The increase of these values lead to an improvement in the infection outcome. For example, a virtual patient with moderate neutropenia and a simulated treatment might attain an infection outcome that corresponded to that of a patient with mild neutropenia or even to an infection outcome for an individual with a non-neutropenic immune status. Therefore, after simulating with a certain parameter set we classified the simulation outcome as described earlier.

The stepwise increase of the parameters was continued until a parameter configuration was found with an infection outcome for non-neutropenic individuals. For quantification of the improvement of the infection outcome, we fitted an exponential function at the transitions between two consecutive degrees of neutropenia severity. Here, the factors and are given by and , and denote the ratios between the treatment parameter values and the parameter values obtained from minimizing the LSE under non-neutropenic conditions.

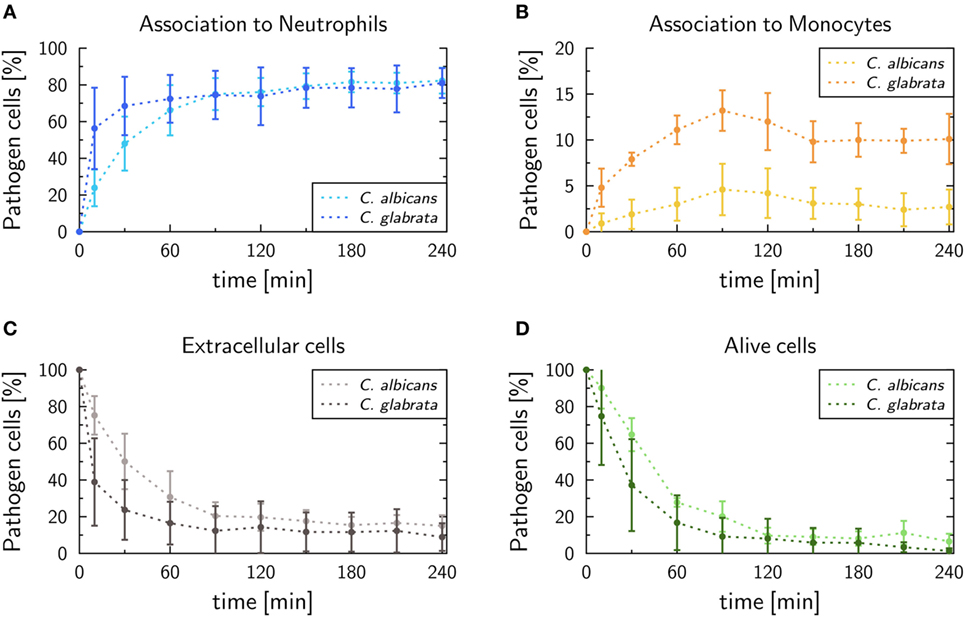

In this study, we performed human whole-blood infection assays with C. glabrata and compared the measured data with experimental measurements for C. albicans by applying a previously established protocol (16). The kinetics of pathogens associated with either neutrophils or monocytes can be seen in Figures 2A,B, respectively. In case of C. glabrata, 81.0 ± 8.1% cells were associated with neutrophils, which is similar to C. albicans with 82.3 ± 7%. However, the experimental data show different kinetics for the two species, since C. glabrata is phagocytosed by neutrophils in a shorter time. By contrast, the association with monocytes is higher for C. glabrata with 10.1 ± 2.7%, while only 2.7 ± 1.9% C. albicans cells were associated with monocytes 4 h post infection. Due to the phagocytosis of the pathogens by the immune cells, 4 h post infection, 8.9 ± 7.5% cells remained extracellular for C. glabrata and 15.0 ± 5.8% for C. albicans (see Figure 2C). The remaining extracellular cells are referred to as immune-evasive cells, as already introduced in previous studies (16, 17). Furthermore, 1.3 ± 1.5% C. glabrata cells remained extracellular and alive 4 h post infection (see Figure 2D), which is lower compared with C. albicans with 6.5 ± 4.2%. In comparison with C. albicans, the decrease in alive C. glabrata cells mainly occurred during the first 2 h of the experiment exhibiting a much faster kinetics than for C. albicans.

Figure 2. Experimental data of whole-blood infection assays for Candida albicans (light color) and Candida glabrata (dark color), respectively. After incubation populations of extracellular cells (A), alive cells (B), as well as pathogens phagocytosed by either neutrophils (C) or monocytes (D), were measured by flow cytometry and plating assays.

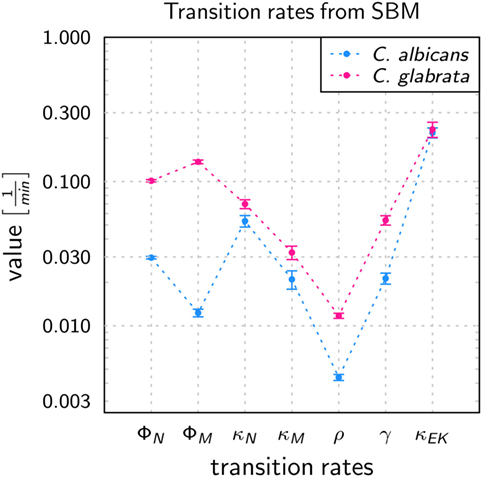

To quantify infection scenarios for the two pathogens, immune-reaction rates of the SBM were estimated by fitting to the experimental data as done previously for C. albicans in human whole blood (17). As explained in detail in Section “Material and Methods,” this was done by computing the so-called combined units, which are combinations of different pathogen states and were directly accessible in experiment. In terms of these combined units, we evaluated the quality of a simulation by calculating the LSE between the experimental data and the in silico data. To determine the immune-reaction rates representing the best fit to the experimental data, i.e., that are associated with the lowest LSE, we applied the method of Simulated Annealing based on the Metropolis Monte Carlo scheme. The resulting immune-reaction rates from the fitting procedure where used to simulate the infection with the pathogens in 1 ml of blood, containing 5 × 106 neutrophils, 5 × 105 monocytes, and 1 × 106 cells, and are shown in Figure 3 and in Table S1 in Supplementary Material.

Figure 3. Transition rates obtained from the calibration of the state-based model (SBM) to experimental data of the whole-blood infection assay for Candida albicans (blue) and Candida glabrata (pink), respectively. The values are compared for the phagocytosis rate for neutrophils (ϕN), and by monocytes (ϕM), killing rate for neutrophils (κN) and monocytes (κM), the rate at which the pathogens can evade the immune response with regard to phagocytosis and/or killing (ρ) as well as the rates that define the extracellular killing, i.e., γ and . Error bars correspond to SDs.

The values of immune-reaction rates for C. albicans infection of whole blood are in line with our previous results (17). The reaction rate values for C. glabrata infection mostly differ in comparison to reaction rates for C. albicans infection (see Figure 3). The phagocytosis rate of neutrophils in the infection scenario with C. glabrata is ϕN = 10.11 × 10−2 min−1, which is 3.5 times higher than for C. albicans infection. The phagocytosis rate for monocytes is with ϕM = 13.69 × 10−2 min−1 an order of magnitude higher than in the case of C. albicans infection. These higher phagocytosis rates arise due to the faster kinetics measured for C. glabrata in the experimental data (see Figure 2). Furthermore, the order in the magnitude of phagocytosis rates is reversed in comparison to C. albicans infection, because for C. glabrata the phagocytosis rate of monocytes is 1.4 times higher than that for neutrophils. The killing rate of neutrophils is for C. glabrata κN = 6.98 × 10−2 min−1, which is only slightly higher than for C. albicans infection. Furthermore, differences between the fungal pathogens are again observed in the killing rate for monocytes, which is 1.5 times higher for C. glabrata with κM = 3.22 × 10−2 min−1 compared with C. albicans. As was previously observed for C. albicans (16, 17), also C. glabrata was found to evade the immune response and to remain even hours post infection alive and non-phagocytosed in human whole blood (Figures 2C,D). The rate for fungal cells becoming evasive against the immune response is for both pathogens comparably low, i.e., ρ = 1.173 × 10−2 min−1 for C. glabrata and ρ = 0.439 × 10−2 min−1 for C. albicans. A comparison of both rates that define the extracellular killing by antimicrobial peptides (κEK(t)) showed that the value of is similar for both pathogens (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material) and γ is 2.5 times larger for infection scenarios with C. glabrata (γ = 5.39 × 10−2 min−1).

The time-resolved kinetics of the fits with the lowest LSE for the two fungal pathogens can be seen in Figures S1 and S2 in Supplementary Material, where the thickness of the simulation curves reflect random variations within the SDs of the immune-reaction rates. For both pathogens, the SBM adequately resembled the experimental data. Since the SBM neglects all spatial aspects of the infection scenarios, we performed a bottom-up modeling approach by combining the SBM with the ABM (17).

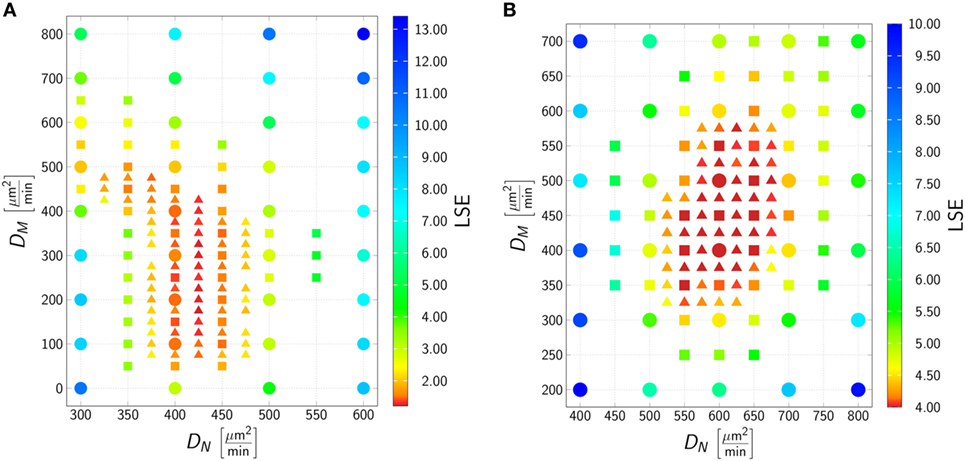

To determine the migration parameters of neutrophils and monocytes in whole-blood infection scenarios with the respective pathogens, we used the experimentally measured data as well as the fitted immune-reaction rates from the SBM to perform stochastic spatiotemporal simulations by the ABM in 1 μl of blood. As a result of this bottom-up modeling approach for whole-blood infection assays, we obtained the diffusion coefficients of the immune cells in response to C. albicans. This can be seen in Figure 4A, where the best solution, i.e., the parameter configuration of (DN, DM) that resulted in the smallest LSE, was identified to be . In line with our earlier findings (17), for C. albicans the LSE was sensitive for variations in DN but not for variations in DM. The range of DM that still lead to comparably low LSE values spans from approximately 100 μm2/min up to 500 μm2/min, whereas the range with comparably low LSE for DN was limited to 400–425 μm2/min. As shown in Figure S3 in Supplementary Material, the fitting results are in excellent agreement with the experimental data, and the stochasticity of the in silico experiments still give rise to low SDs in the simulation curves, as can be inferred from the thickness of the curves representing 30 runs.

Figure 4. Result of the agent-based model (ABM) parameter estimation for whole-blood infection assays with Candida albicans (A) and Candida glabrata (B). Adaptive regular grid search was applied to fit the ABM to the experimental data and diffusion coefficients for neutrophils (DN) and monocytes (DM) were determined. At each grid point 1 μl blood was simulated, and 30 realizations for each parameter configuration were performed. Three different refinement levels were performed: simulations of the first level are represented as dots, simulations of the second level are represented as squares, and simulations of the third level are represented as triangles. The best fit to the experimental data was found at for C. albicans and at for C. glabrata.

The best fit of the simulation curves to the experimental data of whole-blood infection assays for C. glabrata was achieved for diffusion coefficients for neutrophils and monocytes with values (see Figure 4). We note that the range in which the diffusion coefficient of monocytes can vary for comparable LSE values was found to be much more restricted than in the case of C. albicans, i.e., this range for DM was from 350 μm2/min up to 575 μm2/min for fitting results with comparable LSE. However, in the case of C. glabrata, neutrophils were not found to be restricted to the small range of only ± 12 μm2/min as for C. albicans, but could vary in a range of ± 80 μm2/min. As can be seen in Figure S4 in Supplementary Material, the experimentally determined kinetics of the infection scenario with C. glabrata is in excellent agreement with the simulation curves of the ABM.

Our previous considerations reveal that immune cells exhibit a qualitatively and quantitatively different response against C. albicans and C. glabrata in human whole-blood infection assays. Comparing C. glabrata to C. albicans infection, this is reflected by (i) increased phagocytosis rates and (ii) increased diffusion coefficients by factors of 1.4 and 2.4, respectively, for neutrophils and monocytes. In line with our previous work on the comparison between C. glabrata with C. albicans by live-cell imaging of phagocytosis assays (23–26), these quantitative differences are accompanied with the qualitative variation in the immune response that involves much stronger monocyte activation in the case of C. glabrata. Nevertheless, a prominent role is played by neutrophils that are quantitatively prevalent in cell number and qualitatively important in differently directing the immune response against these fungal pathogens (23).

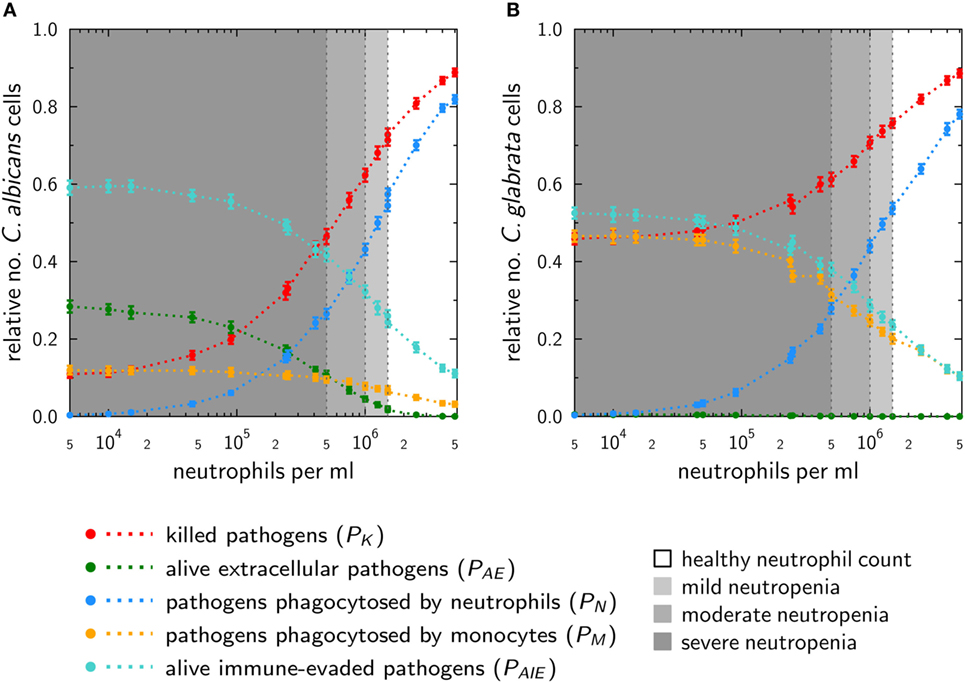

To investigate the impact of neutropenia on the infection outcome with a specific pathogen, we simulated VNP using the ABM. Here, the optimal immune-reaction rates and diffusion coefficients were used as previously determined for normal ANC values. In the virtual patients, we stepwise decreased the number of neutrophils to resemble different degrees of severity of neutropenia and simulated the early immune response during 4 h post infection. The contributions of the combined units—such as killed, phagocytosed and immune-evasive Candida cells at 4 h post infection—are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. In silico infections under neutropenic conditions with Candida albicans (A) and Candida glabrata (B) were performed by gradually decreasing the absolute neutrophil count in the agent-based model. Plots show the fraction of killed cells (red), alive and extracellular cells (green), phagocytosed cells by neutrophils (blue), and monocytes (yellow) as well as (alive) cells that are able to evade the immune system (turquoise) at 4 h post infection.

The phagocytosis by neutrophils is for both pathogens quite similar. For mild neutropenia the phagocytosis by neutrophils ranges for both fungal pathogens between ~40 and 50%, for mild neutropenia between ~25 and 40%, and is below ~25% for severe neutropenia. Interestingly, despite these similarities, the infection outcomes for the two pathogens under the condition of neutropenia are predicted to be remarkably different. As shown in Figure 5A, a stronger impact on the infection outcome can be observed for C. albicans, where in the scenario of severe neutropenia the number of killed fungal cells achieves only 10–45%. By contrast, killing of C. glabrata in severe neutropenia is more efficient, and the fraction of dead cells ranges between 45 and 60% of total fungal cells (see Figure 5B).

This difference is governed by the behavior of monocytes in response to the two fungal pathogens. Higher phagocytosis rates in case of C. glabrata compared with C. albicans enable monocytes to partially compensate for the loss of neutrophils under conditions of neutropenia. This compensatory effect is relatively low for C. albicans, where the fraction of cells that were phagocytosed by monocytes increased from 3% for normal ANC to only 12% under the condition of severe neutropenia (see Figure 5A). For C. glabrata, this increase in monocyte phagocytosis rose from 10 to 46% of the C. glabrata cells (see Figure 5B). Furthermore, the infection outcome is also characterized by the number of cells that are able to evade the immune response. Immune evasion is more pronounced for C. albicans, where also for normal ANC 15% of all fungal cells are able to evade the immune response (see Figure 5A). However, with stronger degrees of neutropenia the fraction of these cells even increases to about 60%. In the case of C. glabrata, only 10% of the cells can evade the immune response for normal ANC, while this fraction rises up to 50% under conditions of severe neutropenia (see Figure 5B). As explained in Section “Materials and Methods,” the infection outcome is mainly characterized by the fraction of killed as well as the fraction of alive and immune-evasive Candida cells. Therefore, we assigned the values of PK and PAIE at the boundaries to pattern that characterize the different degrees of severity of neutropenia (see Table S2 in Supplementary Material). Subsequently, with the help of these patterns, we were able to classify simulations of medical treatments in neutropenic patients.

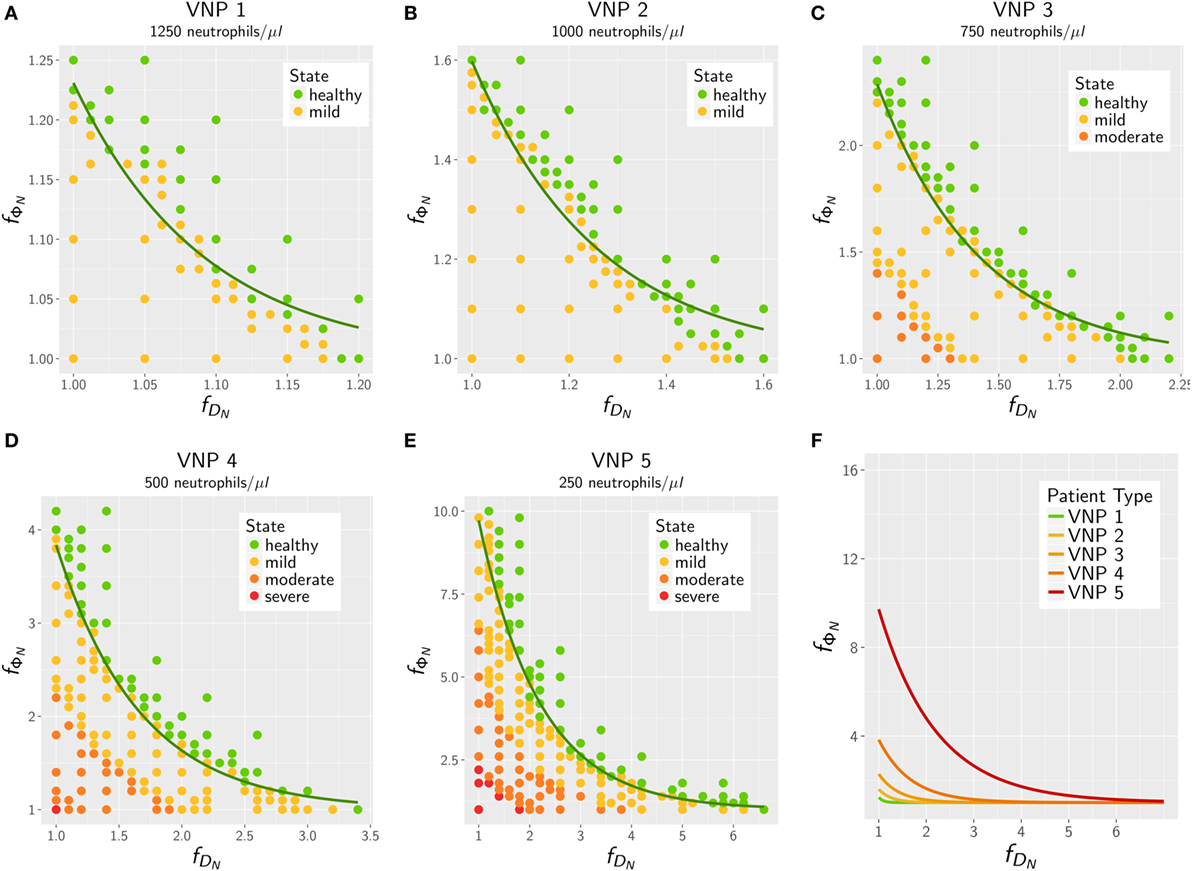

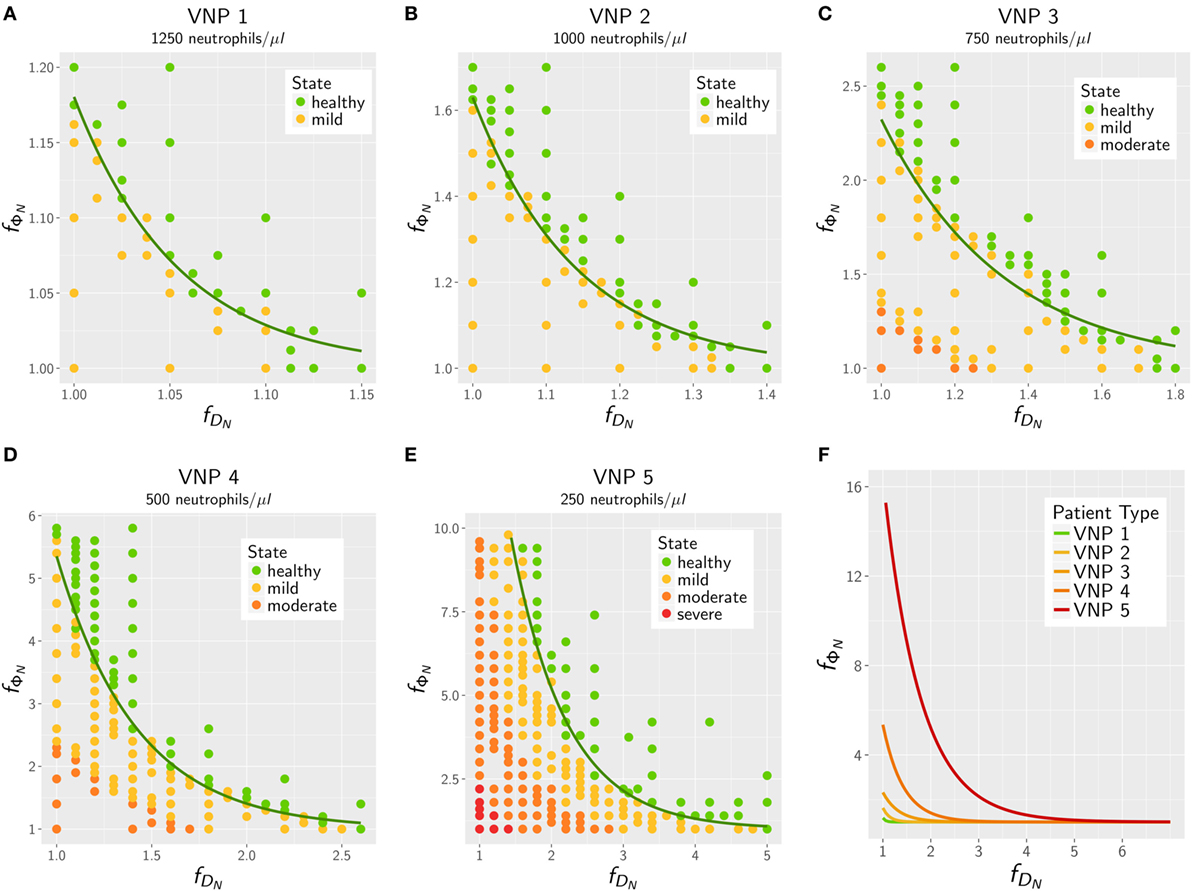

After we simulated the infection with the pathogens C. albicans and C. glabrata in VNP, we selected five types of VNP with different severity degrees of neutropenia for in silico treatment. The VNP-1 is characterized by an ANC of 1,250 neutrophils/μl representing patients with mild neutropenia. At the transition between mild and moderate, the ANC is 1,000 neutrophils/μl, and the corresponding VNP is referred to as VNP-2. Similarly, we defined VNP-3, VNP-4 and VNP-5 that are characterized, respectively, by ANC of 750 neutrophils/μl (moderate neutropenia), 500 neutrophils/μl (transition between moderate and severe neutropenia), and 250 neutrophils/μl (severe neutropenia). The in silico treatment involves the increase of neutrophil activation in terms of their phagocytosis rate and/or diffusion coefficient to quantitatively investigate its impact on the reduced numbers of neutrophils in these patients. Thus, increasing the phagocytosis rate and/or diffusion coefficient of neutrophils in a stepwise fashion, we simulated the infection with either of the two pathogens C. albicans and C. glabrata under neutropenic conditions. Afterward, the infection outcome of the simulation was classified according to the previously determined pattern (see Patterns and Classification of Simulations). To find a formal description of the increase of neutrophil phagocytosis rate and diffusion coefficient required for reaching the infection outcome for non-neutropenic individuals, we fitted an exponential function of the form at the transition where the non-neutropenic infection outcome is reached. Here, the factors and are defined as and , where and denote parameters that are affected by the treatment, and and refer to the parameter values obtained by minimizing the LSE under non-neutropenic conditions. We varied and over one order of magnitude, i.e., , and plotted the resulting curves for each type of VNP in Figure S5 in Supplementary Material for the fitting parameters a and b as provided in Table S3 in Supplementary Material.

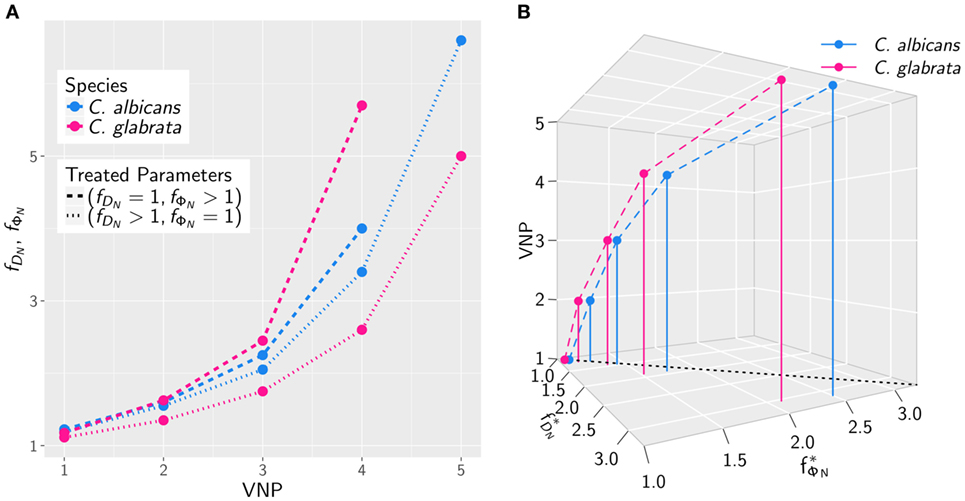

The results for the in silico treatment of VNP with C. albicans and C. glabrata infection are shown in detail in Figures 6 and 7, respectively. Performing more than 4 × 104 simulations, we generally found that all VNP do reach the infection outcome of non-neutropenic patients by increasing neutrophil activation in terms of phagocytosis rate and/or diffusion coefficient. As could be expected, the required increase in neutrophil activation depends on the severity degree of neutropenia in VNP. For VNP with severe neutropenia (VNP-5), reaching the infection outcome of non-neutropenic patients would require relatively high values for with , whereas the treatment was always successful for with . To compare the two fungal pathogens with each other, we first fixed either or and varied only one parameter, respectively, or . As can be seen in Figure 8A, for both fungal pathogens increasing the diffusion coefficient yields the infection outcome of non-neutropenic patients at smaller factors than increasing the phagocytosis rate, i.e., . Interestingly, increasing only the neutrophil diffusion, the in silico treatment was found to be more effective for C. glabrata, whereas it turned out to be more effective for C. albicans if only the phagocytosis rate was increased. The combined impact of increasing and yielded a pair of optimal values with minimal distance from where the infection outcome of non-neutropenic patients was reached. The results are shown in Figure 8B, where the comparison between C. albicans and C. glabrata predicts that for the optimal in silico treatment, i.e., the required relative increase of the diffusion coefficient is larger than that for the phagocytosis rate. Moreover, the optimal in silico treatment was reached for factors with lower values for all VNP in the case of C. glabrata.

Figure 6. In silico treatment of virtual neutropenic patients (VNP) infected with Candida albicans was simulated using the agent-based model. Stepwise increase of phagocytosis rate and diffusion coefficient of neutrophils was performed for VNP with various severity degrees of neutropenia: VNP1–5: 1,250 (A), 1,000 (B), 750 (C), 500 (D), and 250 (E) neutrophils/μl. Simulated points are classified according to the previously determined patterns: green points show a non-neutropenic infection outcome, yellow points show an infection outcome comparable to a mild neutropenia, orange points show an infection outcome comparable to a moderate neutropenia, and red points show an infection outcome comparable to a severe neutropenia. Solid lines depict the fitted exponential function at the transition to the non-neutropenic infection outcome. For comparison the fitted curves for the five VNP with their severity degrees of neutropenia are shown in panel (F).

Figure 7. In silico treatment of virtual neutropenic patients (VNP) infected with Candida glabrata was simulated using the agent-based model. Stepwise increase of phagocytosis rate and diffusion coefficient of neutrophils was performed for VNP with various severity degrees of neutropenia: VNP1–5: 1,250 (A), 1,000 (B), 750 (C), 500 (D), and 250 (E) neutrophils/μl. Simulated points are classified according to the previously determined patterns: green points show a non-neutropenic infection outcome, yellow points show an infection outcome comparable to a mild neutropenia, orange points show an infection outcome comparable to a moderate neutropenia, and red points show an infection outcome comparable to a severe neutropenia. Solid lines depict the fitted exponential function at the transition to the non-neutropenic infection outcome. For comparison, the fitted curves for the five VNP with their severity degrees of neutropenia are shown in panel (F).

Figure 8. The increase in neutrophil activation required to reach the infection outcome of non-neutropenic patients depends on the severity degree of neutropenia in VNP. (A) Comparison of Candida albicans (blue) and Candida glabrata (pink) infection for various VNP in terms of the factors and keeping either or fixed. (B) The same as in panel (A) allowing both factors to vary to attain the optimal values with minimal distance from at which the infection outcome of non-neutropenic patients is reached.

In this study, we investigated bloodstream infections with the fungal pathogens C. albicans and C. glabrata in human whole blood. Special focus was put on the infection scenario under neutropenic conditions as well as possible treatment strategies. These conditions are clinically relevant as it is well established that neutropenia promotes dissemination of Candida spp. during bloodstream infection and impairs prognosis. We used a previously established bottom-up modeling approach that combines different mathematical modeling approaches of increasing complexity based on wet-lab experiments (17). To investigate infection by different fungal pathogens, we first performed whole-blood infection assays using blood of healthy individuals. In the past, these whole-blood infection models have already been successfully applied to analyze the early immune response to clinically relevant pathogens (27–29) and to identify their virulence factors (30, 31). Furthermore, the influence of genetic polymorphisms on the immune response have been tested (32, 33) as well as potential therapeutic approaches and vaccine efficacy (34–38). In this study, we applied this experimental modeling approach to investigate early immune responses to the two Candida spp. in blood. The resulting experimental data showed that the immune response followed a faster kinetics for C. glabrata than for C. albicans, which is reflected by an earlier phagocytosis of this pathogen. In line with our previous studies (16, 17, 23), monocytes were found to contribute more to the immune response against C. glabrata compared with C. albicans.

The system behavior was quantified by estimating values for immune-reaction rates, such as phagocytosis and killing rates, based on fitting a SBM to the experimentally measured data (17). As expected from the observed difference in the kinetics of the immune response between C. albicans and C. glabrata, we found that the phagocytosis rates were orders of magnitude higher for C. glabrata with monocytes reaching the highest values (see Table S2 in Supplementary Material). Thus, for C. glabrata the phagocytosis rate for monocytes is higher than for neutrophils and this relation is inverted for C. albicans. Applying a bottom-up modeling approach (17), we used an ABM to estimate migration parameters for neutrophils and monocytes in response to the two fungal species. For C. glabrata these migration parameter were higher than for C. albicans. As previously shown for C. albicans the outcome of the immune response was restricted to a narrow regime of migration parameters for the neutrophils (17), whereas these migration parameters in the case of C. glabrata infections could vary over a significantly wider range to fit the experimental data. This is another indication for the observable fact that monocytes play a more important role in the defense against C. glabrata compared with C. albicans (23, 39).

Since fungal infections by Candida spp. are a major risk for immunocompromised patients, we extended the computer simulations for normal ANC by numerically studying infection scenarios in virtual patients with different severity degrees of neutropenia. Due to the pronounced importance of neutrophils in the immune response against C. albicans, these computer simulations predicted a strong negative impact on the infection outcome for VNP depending on the severity degree of neutropenia. Although the impact of neutropenia on the infection outcome during C. glabrata infection was not as strong as for C. albicans, the immune response was still to a large extent impaired. For example, this was observed by the prediction that the fraction of killed pathogens at 4 h post infection decreased from around 90% for both species under normal ANC to about 50 and 10% for C. glabrata and C. albicans for severe neutropenic conditions, respectively. Moreover, at 4 h post infection, a fraction of 30% C. albicans cells are still alive and extracellular in human blood that could contribute to the dissemination to other body parts in real patients. While the fraction of alive and extracellular C. glabrata cells is negligible at 4 h post infection, a large fraction of about 50% is phagocytosed by monocytes including a few percent of fungal cells that are still alive and may disseminate by eventually escaping from the monocytes. These data again point toward different virulence traits in the two Candida spp. (40).

The bottom-up modeling approach for the simulation of infection scenarios under neutropenic conditions was established to simulate the effects of medical treatments. To date there exist three different ways to approach neutropenia in the clinical setting, which comprise (i) the stimulation and activation of remaining neutrophils by medical treatment of the patient, (ii) the internal stimulation of neutrophil maturation and release from the bone marrow by medication of patients with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and (iii) the transfusion of G-CSF/steroid mobilized neutrophils from a donor. The latter treatment of healthy donors leads to a vast increase of peripheral blood neutrophils (41–44), which are subsequently extracted from the donor by leukapheresis and administered to the patient to increase the ANC in blood. This therapy shows higher rates of patient survival in the context of bacterial infections (43), whereas improvement in patient survival was not consistently observed for fungal infections (45–47). In particular, Gazendam et al. (48) show that the G-CSF/dexamethasone stimulation of donor neutrophils leads to a change in their granular content, which impairs the fungal killing capacity with regard to C. albicans. The cytokine treatment with G-CSF to trigger the neutrophil release from the bone marrow in patients is mainly applied in congenital neutropenia and causes a significant increase of the ANC in blood (49, 50). Before effective drugs were available, children with congenital neutropenia typically died in their first year of life due to bacterial and fungal infections (51, 52). The G-CSF treatment makes use of the emergency mobilization of neutrophils in response to an inflammatory signal and the secretion of chemokines leading to neutrophil migration into blood vessels (53). However, patients can be also low-responders or even non-responders exhibiting reduced effects of G-CSF (49, 54). Finally, instead of increasing the circulating number of neutrophils, the option to medically treat neutropenia by inflammatory cytokines, such as interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor α, yields a modulation of the immune response by the stimulation and activation of neutrophils in blood (41, 44). Both cytokines have been reported to enhance the neutrophil response against fungi, e.g., Candida spp. (55), Aspergillus spp. (56), and Cryptococcus spp. (57).

In this study, we focused on investigating the treatment of neutropenic patients by inflammatory cytokines to quantify the possibility of balancing neutropenic conditions and clearance of infection. The simulations of this in silico treatment revealed that an increase of the phagocytosis rate and/or the migration parameter of neutrophils generally improved the infection outcome. For both Candida spp. under investigation, conditions of mild neutropenia can be compensated resembling an infection outcome of non-neutropenic individuals by an increase in either the phagocytosis rate or the diffusion coefficient, or a combination of both, by less than 25% percent. The computer simulations allowed us to rigorously quantify the relative change in these parameters needed for any severity level of neutropenia. In the case of severe neutropenia, medical treatments would need to increase these parameters by at least 250% for the phagocytosis rate and at least 300% for the diffusion coefficient to reach infection outcomes in VNP comparable to individuals with normal ANC. It should be noted that the modulation of parameters has to be combined, because even a 10-fold increase of the phagocytosis rate alone would not recover the infection outcome of non-neutropenic individuals. Thus, the quantitative simulation of in silico treatments generates concrete predictions regarding the relative impact that treatments with inflammatory cytokines are required to exert on these two parameters. Moreover, our numerical experiments predict that C. albicans compared with C. glabrata always requires stronger increases in the phagocytosis rate and the diffusion coefficient for the same conditions of neutropenia.

Clearly, the underlying model assumptions (such as spatial homogeneity and absence of external forces) cannot be 1:1 translated into the in vivo situation—neither in small vessels nor in tissue. Despite this, several predictions resulting from the model could be confirmed in vivo or are in line with clinical findings (16). For this study, this also applies to the observations that (i) neutropenia may result in poor prognosis and a higher ratio of disseminated candidiasis [e.g., Ref. (58, 59)] and (ii) monocytes play a more important role in C. glabrata infection (23). Even though clinical studies will ultimately be required to validate our hypotheses, the first step would be to test these treatment strategies in whole-blood infection assays and our simulations for VNP can be used for this testing.

Our study may be extended in different ways. For example, computer simulations for various pathogens, such as Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp., which were shown to cause bacteremia and sepsis under conditions of neutropenia, could be performed (52, 60). Moreover, treatment strategies that lead to an increased ANC in neutropenic patients, like the transfusion therapy as well as the G-CSF treatment, could be simulated and compared with the cytokine treatment considered in this study. Furthermore, the bottom-up approach provides the possibility to investigate the impact of other immune disorders on the infection outcome with the pathogens under consideration. Moreover, the generated predictions of this study could be examined in future wet-lab experiments. Therefore, whole-blood infection assays with C. albicans or C. glabrata in human blood with reduced ANC could be performed. Such neutropenic blood samples could be taken from patients with neutropenia, where it should be considered that primary diseases of the patient may affect the experimental results. Another possibility may be to generate neutropenic blood samples in the wet lab by a controlled reduction of the neutrophil number. However, this poses a high challenge, since the remaining blood constituents will be affected by side effects that cannot be well controlled. Investigating such host–pathogen interactions by combining wet-lab and dry-lab studies is in the spirit of system biology. This approach provides a powerful tool to investigate biological systems in a qualitative as well as quantitative fashion and enables hypothesis generation in dry-lab as well as hypothesis testing in wet-lab studies.

Human peripheral blood was collected from healthy volunteers after informed consent. This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Jena (permit number: 273-12/09).

ST and MTF conceived and designed this study. MTF and OK provided computational resources and materials, respectively. Data processing, implementation, and application of the computational algorithm were done by ST, TL, MP, and MTF. Experiments were performed by KH and IL. ST, TL, MP, KH, IL, OK, and MTF evaluated and analyzed the results of this study; drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was financially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the excellence graduate school Jena School for Microbial Communication (JSMC), the CRC/TR124 FungiNet (project B4 to MTF and project C3 to OK), and the Center for Sepsis Control and Care (CSCC) (Project Quantim, FKZ 01EO1502 to MTF and OK) that is funded by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00667/full#supplementary-material.

1. Murphy KP, Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M. Janeway’s Immunobiology. 7th ed. New York, London: Garland Science (2008).

2. Schwartzberg LS. Neutropenia: etiology and pathogenesis. Clin Cornerstone (2006) 8:S5–11. doi:10.1016/S1098-3597(06)80053-0

3. Duggan S, Leonhardt I, Hünniger K, Kurzai O. Host response to Candida albicans bloodstream infection and sepsis. Virulence (2015) 6:316–26. doi:10.4161/21505594.2014.988096

4. Fidel PL Jr, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev (1999) 12:80–96.

5. Sardi JC, Scorzoni L, Bernardi T, Fusco-Almeida AM, Mendes Giannini MJ. Candida species: current epidemiology, pathogenicity, biofilm formation, natural antifungal products and new therapeutic options. J Med Microbiol (2013) 62:10–24. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.045054-0

6. Orasch C, Marchetti O, Garbino J, Schrenzel J, Zimmerli S, Mühlethaler K, et al. Candida species distribution and antifungal susceptibility testing according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and new vs. old Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute clinical breakpoints: a 6-year prospective candidaemia survey from the fungal infection network of Switzerland. Clin Microbiol Infect (2014) 20:698–705. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12440

7. Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B, Article M. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Clin Infect Dis (2002) 48105:119–28. doi:10.4161/viru.22913

8. Calderone RA, Clancy CJ, editors. Candida and Candidiasis. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press (2002).

9. Rodrigues CF, Silva S, Henriques M. Candida glabrata: a review of its features and resistance. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2014) 33:673–88. doi:10.1007/s10096-013-2009-3

10. Kitano H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science (2002) 295:1662–4. doi:10.1126/science.1069492

11. Aderem A. Systems biology: its practice and challenges. Cell (2005) 121:511–3. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.020

12. Bruggeman FJ, Westerhoff HV. The nature of systems biology. Trends Microbiol (2007) 15:45–50. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.11.003

13. Germain RN, Meier-Schellersheim M, Nita-Lazar A, Fraser IDC. Systems biology in immunology: a computational modeling perspective. Annu Rev Immunol (2011) 29:527–85. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101317

14. Horn F, Heinekamp T, Kniemeyer O, Pollmächer J, Valiante V, Brakhage AA. Systems biology of fungal infection. Front Microbiol (2012) 3:108. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00108

15. Medyukhina A, Timme S, Mokhtari Z, Figge MT. Image-based systems biology of infection. Cytometry A (2015) 87:462–70. doi:10.1002/cyto.a.22638

16. Hünniger K, Lehnert T, Bieber K, Martin R, Figge MT, Kurzai O. A virtual infection model quantifies innate effector mechanisms and Candida albicans immune escape in human blood. PLoS Comput Biol (2014) 10:e1003479. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003479

17. Lehnert T, Timme S, Pollmächer J, Hünniger K, Kurzai O, Figge MT. Bottom-up modeling approach for the quantitative estimation of parameters in pathogen-host interactions. Front Microbiol (2015) 6:608. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00608

18. Pollmächer J, Figge MT. Agent-based model of human alveoli predicts chemotactic signaling by epithelial cells during early Aspergillus fumigatus infection. PLoS One (2014) 9:e111630. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111630

19. Pollmächer J, Figge MT. Deciphering chemokine properties by a hybrid agent-based model of Aspergillus fumigatus infection in human alveoli. Front Microbiol (2015) 6:503. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00503

20. Dale DC, Cottle TE, Fier CJ, Bolyard AA, Bonilla MA, Boxer LA, et al. Severe chronic neutropenia: treatment and follow-up of patients in the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry. Am J Hematol (2003) 72:82–93. doi:10.1002/ajh.10255

21. Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Cancer (2004) 100:228–37. doi:10.1002/cncr.11882

22. Seider K, Brunke S, Schild L, Jablonowski N, Wilson D, Majer O, et al. The facultative intracellular pathogen Candida glabrata subverts macrophage cytokine production and phagolysosome maturation. J Immunol (2011) 187:3072–86. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003730

23. Duggan S, Essig F, Hünniger K, Mokhtari Z, Bauer L, Lehnert T, et al. Neutrophil activation by Candida glabrata but not Candida albicans promotes fungal uptake by monocytes. Cell Microbiol (2015) 17:1259–76. doi:10.1111/cmi.12443

24. Essig F, Hünniger K, Dietrich S, Figge MT, Kurzai O. Human neutrophils dump Candida glabrata after intracellular killing. Fungal Genet Biol (2015) 84:37–40. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2015.09.008

25. Brandes S, Mokhtari Z, Essig F, Hünniger K, Kurzai O, Figge MT. Automated segmentation and tracking of non-rigid objects in time-lapse microscopy videos of polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Med Image Anal (2015) 20(1):34–51. doi:10.1016/j.media.2014.10.002

26. Brandes S, Dietrich S, Hünniger K, Kurzai O, Figge MT. Migration and interaction tracking for quantitative analysis of phagocyte-pathogen confrontation assays. Med Image Anal (2017) 36:172–83. doi:10.1016/j.media.2016.11.007

27. Tena GN, Young DB, Eley B, Henderson H, Nicol MP, Levin M, et al. Failure to control growth of mycobacteria in blood from children infected with human immunodeficiency virus and its relationship to T cell function. J Infect Dis (2003) 187:1544–51. doi:10.1086/374799

28. Silva D, Ponte CGG, Hacker MA, Antas PRZ. A whole blood assay as a simple, broad assessment of cytokines and chemokines to evaluate human immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens. Acta Trop (2013) 127:75–81. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.04.002

29. Urrutia A, Duffy D, Rouilly V, Posseme C, Djebali R, Illanes G, et al. Standardized whole-blood transcriptional profiling enables the deconvolution of complex induced immune responses. Cell Rep (2016) 16:2777–91. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.011

30. Echenique-Rivera H, Muzzi A, Del Tordello E, Seib KL, Francois P, Rappuoli R, et al. Transcriptome analysis of Neisseria meningitidis in human whole blood and mutagenesis studies identify virulence factors involved in blood survival. PLoS Pathog (2011) 7:e1002027. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002027

31. Van Der Maten E, De Jonge MI, De Groot R, Van Der Flier M, Langereis JD. A versatile assay to determine bacterial and host factors contributing to opsonophagocytotic killing in hirudin-anticoagulated whole blood. Sci Rep (2017) 7:3–12. doi:10.1038/srep42137

32. Lin J, Yao YM, Yu Y, Chai JK, Huang ZH, Dong N, et al. Effects of CD14-159 C/T polymorphism on CD14 expression and the balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in whole blood culture. Shock (2007) 28:148–53. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e3180341d35

33. Duffy D, Rouilly V, Libri V, Hasan M, Beitz B, David M, et al. Functional analysis via standardized whole-blood stimulation systems defines the boundaries of a healthy immune response to complex stimuli. Immunity (2014) 40:436–50. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.002

34. Deslouches B, Islam K, Craigo JK, Paranjape SM, Montelaro RC, Mietzner TA. Activity of the de novo engineered antimicrobial peptide WLBU2 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in human serum and whole blood: implications for systemic applications. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2005) 49:3208–16. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.8.3208-3216.2005

35. Jemmett K, Macagno A, Molteni M, Heckels JE, Rossetti C, Christodoulides M. A cyanobacterial lipopolysaccharide antagonist inhibits cytokine production induced by Neisseria meningitidis in a human whole-blood model of septicemia. Infect Immun (2008) 76:3156–63. doi:10.1128/IAI.00110-08

36. Li M, Xue J, Liu J, Kuang D, Gu Y, Lin S. Efficacy of cytokine removal by plasmodia filtration using a selective plasma separator: in vitro sepsis model. Ther Apher Dial (2011) 15:98–104. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2010.00850.x

37. Plested JS, Welsch JA, Granoff DM. Ex vivo model of meningococcal bacteremia using human blood for measuring vaccine-induced serum passive protective activity. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2009) 16:785–91. doi:10.1128/CVI.00007-09

38. Sprong T, Brandtzaeg P, Fung M, Pharo AM, Høiby EA, Michaelsen TE, et al. Inhibition of C5a-induced inflammation with preserved C5b-9-mediated bactericidal activity in a human whole blood model of meningococcal sepsis. Blood (2003) 102:3702–10. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-03-0703

39. Jacobsen ID, Brunke S, Seider K, Schwarzmüller T, Firon A, D’Enfért C, et al. Candida glabrata persistence in mice does not depend on host immunosuppression and is unaffected by fungal amino acid auxotrophy. Infect Immun (2010) 78:1066–77. doi:10.1128/IAI.01244-09

40. Brunke S, Hube B. Two unlike cousins: Candida albicans and C. glabrata infection strategies. Cell Microbiol (2013) 15:701–8. doi:10.1111/cmi.12091

41. Posch W, Steger M, Wilflingseder D, Lass-Flörl C. Promising immunotherapy against fungal diseases. Expert Opin Biol Ther (2017) 17:861–70. doi:10.1080/14712598.2017.1322576

42. Marfin AA, Price TH. Granulocyte transfusion therapy. J Intensive Care Med (2015) 30:79–88. doi:10.1177/0885066613498045

43. Einsele H, Northoff H, Neumeister B. Granulocyte transfusion. Vox Sang (2004) 87:205–8. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6892.2004.00483.x

44. Armstrong-James D, Brown GD, Netea MG, Zelante T, Gresnigt MS, van de Veerdonk FL, et al. Immunotherapeutic approaches to treatment of fungal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis (2017) 17(12):e393–402. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30442-5

45. Strauss RG. Clinical perspectives of granulocyte transfusions: efficacy to date. J Clin Apher (1995) 10:114–8. doi:10.1002/jca.2920100303

46. Bhatia S, McCullough J, Perry EH, Clay M, Ramsay NK, Neglia JP. Granulocyte transfusions: efficacy in treating fungal infections in neutropenic patients following bone marrow transplantation. Transfusion (1994) 34:226–32. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34394196620.x

47. Safdar A, Hanna HA, Boktour M, Kontoyiannis DP, Hachem R, Lichtiger B, et al. Impact of high-dose granulocyte transfusions in patients with cancer with candidemia: retrospective case-control analysis of 491 episodes of Candida species bloodstream infections. Cancer (2004) 101:2859–65. doi:10.1002/cncr.20710

48. Gazendam RP, van de Geer A, van Hamme JL, Tool ATJ, van Rees DJ, Aarts CEM, et al. Impaired killing of Candida albicans by granulocytes mobilized for transfusion purposes: a role for granule components. Haematologica (2016) 101:587–96. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.136630

49. Fioredda F, Calvillo M, Bonanomi S, Coliva T, Tucci F, Farruggia P, et al. Congenital and acquired neutropenias consensus guidelines on therapy and follow-up in childhood from the Neutropenia Committee of the Marrow Failure Syndrome Group of the AIEOP (Associazione Italiana Emato-Oncologia Pediatrica). Am J Hematol (2012) 87:235–8. doi:10.1002/ajh.22225

50. Palmblad J, Papadaki HA, Eliopoulos G. Acute and chronic neutropenias. What is new? J Intern Med (2001) 250:476–91. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00915.x

51. Zeidler C, Boxer L, Dale DC, Freedman MH, Kinsey S, Welte K. Management of Kostmann syndrome in the G-CSF era. Br J Haematol. (2000) 109:490–5. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02064.x

52. Newburger PE. Disorders of neutrophil number and function. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program (2006) 2006:104–10. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.104

53. Köhler A, De Filippo K, Hasenberg M, van den Brandt C, Nye E, Hosking MP, et al. G-CSF-mediated thrombopoietin release triggers neutrophil motility and mobilization from bone marrow via induction of Cxcr2 ligands. Blood (2011) 117:4349–57. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-09-308387

54. Berliner N, Horwitz M, Loughran TP. Congenital and acquired neutropenia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Progr (2004) 2004:63–79. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.63

55. Kullberg BJ, t Wout JW, Hoogstraten C, van Furth R. Recombinant interferon-gamma enhances resistance to acute disseminated Candida albicans infection in mice. J Infect Dis (1993) 168:436–43. doi:10.1093/infdis/168.2.436

56. Nagai H, Guo J, Choi H, Kurup V. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha protect mice from invasive aspergillosis. J Infect Dis (1995) 172:1554–60. doi:10.1093/infdis/172.6.1554

57. Clemons KV, Lutz JE, Stevens DA. Efficacy of recombinant gamma interferon for treatment of systemic cryptococcosis in SCID mice. Society (2001) 45:686–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.3.686

58. Dutta A, Palazzi DL. Candida non-albicans versus Candida albicans fungemia in the non-neonatal pediatric population. Pediatr Infect Dis J (2011) 30:664–8. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e318213da0f

59. Delaloye J, Calandra T. Invasive candidiasis as a cause of sepsis in the critically ill patient. Virulence (2014) 5:154–62. doi:10.4161/viru.26187

Keywords: fungal infections, neutropenia, treatment strategies, bottom-up modeling approach, computer simulations

Citation: Timme S, Lehnert T, Prauße MTE, Hünniger K, Leonhardt I, Kurzai O and Figge MT (2018) Quantitative Simulations Predict Treatment Strategies Against Fungal Infections in Virtual Neutropenic Patients. Front. Immunol. 9:667. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00667

Received: 18 December 2017; Accepted: 19 March 2018;

Published: 04 April 2018

Edited by:

Lars Kaderali, Universitätsmedizin Greifswald, GermanyReviewed by:

Joshua J. Obar, Dartmouth College, United StatesCopyright: © 2018 Timme, Lehnert, Prauße, Hünniger, Leonhardt, Kurzai and Figge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marc Thilo Figge, dGhpbG8uZmlnZ2VAbGVpYm5pei1oa2kuZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.