94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 02 February 2018

Sec. Microbial Immunology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00134

This article is part of the Research Topic Continued Learning of Tissue-specific Immunity from the Immuno-Pathological Spectrum of Leprosy View all 16 articles

The spectrum of clinical forms observed in leprosy and its pathogenesis are dictated by the host’s immune response against Mycobacterium leprae, the etiological agent of leprosy. Previous results, based on metabolomics studies, demonstrated a strong relationship between clinical manifestations of leprosy and alterations in the metabolism of ω3 and ω6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and the diverse set of lipid mediators derived from PUFAs. PUFA-derived lipid mediators provide multiple functions during acute inflammation, and some lipid mediators are able to induce both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses as determined by the cell surface receptors being expressed, as well as the cell type expressing the receptors. However, little is known about how these compounds influence cellular immune activities during chronic granulomatous infectious diseases, such as leprosy. Current evidence suggests that specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators (SPMs) are involved in the down-modulation of the innate and adaptive immune response against M. leprae and that alteration in the homeostasis of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators versus SPMs is associated with dramatic shifts in the pathogenesis of leprosy. In this review, we discuss the possible consequences and present new hypotheses for the involvement of ω3 and ω6 PUFA metabolism in the pathogenesis of leprosy. A specific emphasis is placed on developing models of lipid mediator interactions with the innate and adaptive immune responses and the influence of these interactions on the outcome of leprosy.

Leprosy is a chronic granulomatous disease driven by interactions of the human host with Mycobacterium leprae an obligate intracellular pathogen that infects macrophages and Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system. M. leprae is the only mycobacterial infection that causes widespread demyelinating neuropathy, which results in severe and irreversible nerve tissue damage. The prevalence of leprosy is gradually decreasing in many countries due to multidrug therapy (MDT) (1). However, the rates of new case detection remain relatively stable in developing countries (1). India and Brazil are the countries that exhibit the highest incidence and account for 60 and 13% of the global new cases of leprosy, respectively (1).

Leprosy is well known for its bi-polarization of the immune response, and it is established that the nature and magnitude of the host immune response against M. leprae are critical factors for the pathogenesis of leprosy and its varied clinical manifestations. At one end of the spectrum, tuberculoid (TT) disease is typified by strong T-helper type 1 (Th1) cellular immunity and low bacterial load (2–4). This response promotes the protection against the pathogen via interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) activation of macrophage anti-microbicidal mechanisms (5). These patients also present robust T-helper type 17 (Th17) activity (6) that stimulates macrophages and enhances Th1 responses (7). The other end of the spectrum, lepromatous leprosy (LL), is characterized by a low or even absent Th1 response (8) but robust T-helper type 2 (Th2) and humoral responses. The diminished Th1 response in LL is partially explained by the highly suppressive activity of T regulatory (Treg) cells and the reduced frequency of Th17 cells (4, 6). Consequently, these patients manifest the most severe form of the disease and are unable to control M. leprae growth (2). Between these two clinical forms, patients with intermediate immune responses develop borderline clinical forms: borderline tuberculoid (BT), borderline-borderline (BB), and borderline lepromatous (BL). BT patients present with a dominant IFN-γ response, and also a higher activity of Th17 cells (6), while BL patients exhibit T-cell anergy, because of the higher frequency of Treg cells (4, 6), and a higher production of interleukin-4 (IL-4) (9–11). Peripheral neuropathy can occur in all clinical forms of leprosy but is most pronounced in patients who present with an exacerbated acute immune-inflammatory response, designated type 1 reaction (T1R). Multiple studies indicate that pathogenic CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses (12–14) and production of nitric oxide (NO) in M. leprae-infected macrophages are related with nerve injury in leprosy patients (15). Thus, the human immune response against M. leprae is involved with key aspects of leprosy pathogenesis.

Metabolomic-based studies reveal that M. leprae infection promotes several modifications in human metabolism. The most prominent of these metabolic changes is a correlation between the spectrum of clinical forms of leprosy and the metabolism of ω3 and ω6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (16–18). Of particular interest are the PUFA-lipid mediators: prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), leukotriene B4 (LTB4), lipoxin A4 (LXA4), and resolvin D1 (RvD1). Both PGE2 and PGD2 are found in elevated levels in the sera of LL patients as compared to BT patients (17). Additionally, PGD2 levels are increased in leprosy patients with T1R, while PGE2 levels decrease in patients with a T1R (18). BT and LL patients have similar levels of the pro-resolving lipid mediators, LXA4 and RvD1 (17). However, when compared with healthy individuals, the levels of LXA4 and RvD1 are elevated in the sera of BT and LL patients. In patients with T1R, the level of RvD1 is significantly decreased, as is the ratio of LXA4/LTB4 (18).

It is well established that lipid mediators derived from the metabolism of ω3 and ω6 PUFAs are able to modulate the innate and adaptive immune responses (19–26). Thus, we posit that the PUFA-derived lipid mediators are important factors in the pathogenesis of leprosy. The objectives of this review are to bring together metabolic and immunological data that support our hypothesis and to provide an understanding of how lipid mediators potentially function across the spectrum of disease. Specifically, we will focus the review on the five lipid mediators (PGE2, PGD2, LTB4, LXA4, and RvD1) found to be differentially produced in leprosy patients (17, 18).

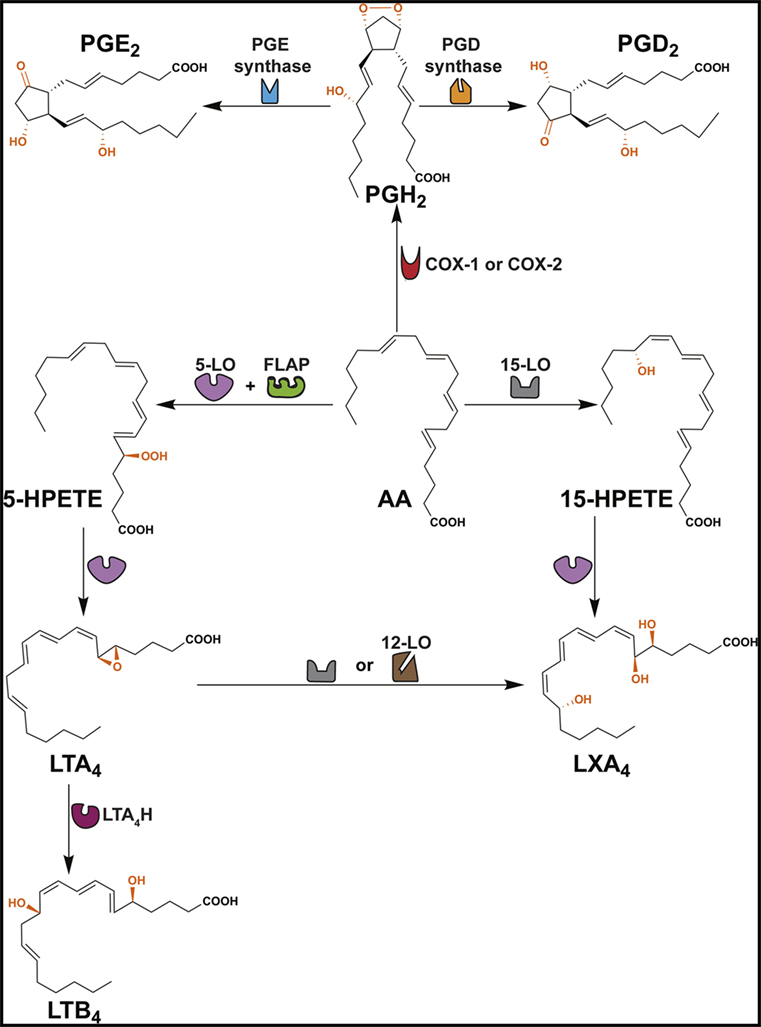

The ω6 PUFA, arachidonic acid (AA), is the precursor for a variety of lipid mediators (prostaglandins, leukotrienes, lipoxins, and thromboxanes) that exhibit immune-inflammatory functions (Figure 1; Table 1) (26–28). Importantly, AA can be metabolized by three separate pathways: cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway, lipoxygenase (LO) pathway, and epoxygenase pathway (the latter is not discussed in this review) (Figure 1) (29).

Figure 1. Formation of PGD2, PGE2, LTB4 and LXA4. This scheme shows that arachidonic acid (AA) is converted to several ω6 PUFA-derived lipid mediators through cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LO) pathways. COX enzymes (constitutive COX-1 or inducible COX-2) exhibit a COX activity that incorporates two molecules of oxygen into AA to form PGG2 (not shown) and peroxidase activity that catalyzes a 2-electron reduction of PGG2 to PGH2. PGH2 is the direct precursor of PGD2 and PGE2. Formation of LTB4 occurs via the precursors 5-HPETE and LTA4. LXA4 is derived from 15-HPETE and/or LTA4. FLAP, 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein; LTA4H, leukotriene A4 hydrolase.

The COX pathway converts AA into prostaglandins via two isoforms of COX, COX-1 and COX-2 (Figure 1) (29). Both enzymes convert AA into PGG2, which is reduced to PGH2 and then converted to PGD2 or PGE2 by PGD or PGE synthase, respectively (Figure 1) (74). PGE2 and PGD2 are involved with the early stages of inflammation, and it is well established that both lipid mediators exhibit a dual role in immune-inflammation due to their capacities to exert pro- and anti-inflammatory responses (Table 1) (38, 75). This might be partially explained by the fact that both prostaglandins are recognized by more than one prostaglandin receptor (PGE2 – EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4; PGD2 – DP1 and CRTH2) (see Table 1) (19, 37, 51, 52). Moreover, PGD2 and its metabolites (e.g., 15d-PGJ2) are ligands for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) (76, 77).

The LO pathway converts AA to leukotrienes and lipoxins (29). The production of LXA4 and LTB4 is dependent on 5-LO that converts AA to leukotriene A4 (LTA4) via 5-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HPETE) (Figure 1) (78–82). Subsequently, LTA4 hydrolase (LTA4H) catalyzes the conversion of LTA4 to LTB4 (83) and platelet-derived 12-LO or 15-LO uses LTA4 as a substrate for the production of LXA4 (Figure 1) (84, 85). LTB4 is involved in the initiating steps of the immune-inflammatory response and exerts its pro-inflammatory functions through two G-protein-coupled receptors BLT1 and BLT2 (Table 1) (86). More specifically, LTB4 has the capacity to act as a chemoattractant for leukocytes, activate inflammatory cells (30), and favor Th1 and Th17 responses (Table 1) (21, 32, 33, 87–89). In contrast, LXA4 is a specialized pro-resolving lipid mediator (SPM) that acts via the G-protein-coupled receptors ALX/FPR2 and GPR32 (Table 1) (63). An imbalance between the levels of LXA4 and LTB4 exacerbate the immune-inflammatory response and/or favor pathogen survival, including mycobacterial infections (21, 90). Importantly, the SPMs promote the resolution phase of inflammation by impairing the recruitment of leukocytes, stimulating the engulfment of apoptotic cells by phagocytes (known as efferocytosis) and inducing tissue repair (28, 69).

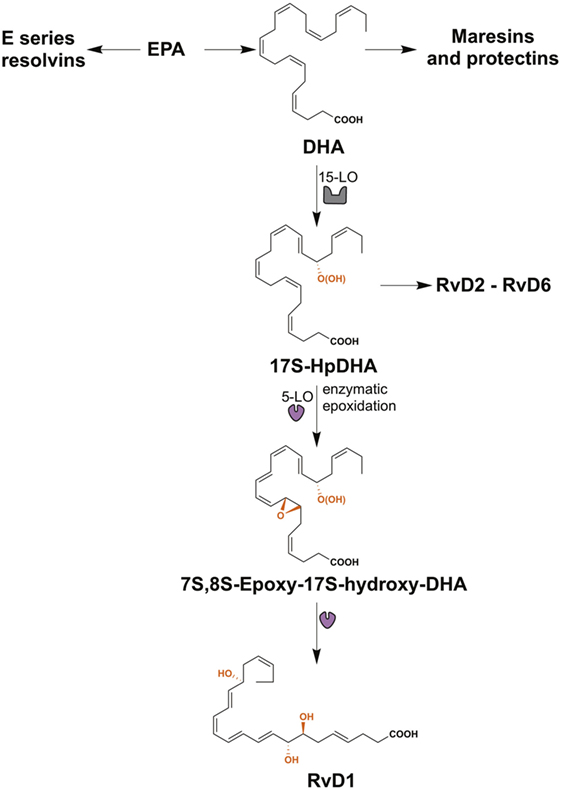

Lipid mediators derived from the essential ω3 PUFAs, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) include the resolvins, maresins, and protectins, all of which are SPMs (Figure 2) (28). The E-series resolvins (resolvins E1 to E3) are synthesized directly from EPA, while maresins (maresin-1 and maresin-2), protectins (protectin-1 and neuroprotectin-1), and D-series resolvins (resolvins D1 to D6) are produced from DHA (Figure 2). However, DHA itself can be produced from EPA by two elongation steps, desaturation and subsequent β-oxidation in the peroxisome (91, 92). Important in this review is the D-series resolvins and specifically RvD1. This SPM has overlapping activities with LXA4 and acts via the same G-protein-coupled receptors, ALX/FPR2 and GPR32 (Table 1) (63).

Figure 2. The biosynthesis of resolvin D1 (RvD1). The resolvins from the E-series (resolvins E1–E3) are synthesized from eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), while maresins (maresin-1 and maresin-2), protectins (protectin-1 and neuroprotectin-1), and resolvins of the series-D (resolvins D1–D6) are produced from docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). RvD1 is generated from the sequential oxygenation of DHA, a process catalyzed by 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO) and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO). The initial conversion of DHA to 17S-HpDHA is catalyzed by 15-LO, followed a second lipoxygenation via 5-LO, which gives a peroxide intermediate that is transformed to 7S-,8S-epoxid-17S-hydroxy-DHA. Subsequently, the enzymatic hydrolysis of this compound generates the trihydroxylated product RvD1.

The identification and quantitation of PUFA-derived lipid mediators have been a challenge due to the small quantities produced within tissues and cells. Thus, highly sensitive methods of gas and liquid chromatography-based separations coupled with detection by mass spectrometry (e.g., GC–MS, GC–MS/MS, LC–MS, and LC–MS/MS) and immunology-based assays [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)] have played a pivotal role in the analysis of lipid mediators (93, 94).

The separation of individual lipid mediators by GC or LC allows the analyses of multiple lipid mediators in a single biological sample, and the detection of the lipid mediators by MS or MS/MS provides a means for their identification and quantification (95). It is noted that many of the ω3 and ω6 PUFA-derived lipid mediators are isomers, therefore the fragmentation patterns generated my MS/MS provide additional structural information over what is obtained with an accurate mass measurement (MS) (96). However, some isomeric lipid mediators produce similar fragment ion profiles. Thus, it is important to apply authentic standards with rigorous chromatographic separation to confirm the identity of specific lipid mediators. A major advantage of LC–MS or LC–MS/MS as compared to GC–MS or GC–MS/MS is that derivatization to ensure volatility of the lipid mediators is not required (97). Nevertheless, GC-based approaches remain an important tool for confirming the structure and abundance of lipid mediators obtained via LC–MS or LC–MS/MS analyses (93, 94, 98).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is an orthogonal approach for the quantification of lipid mediators and offers relatively high sensitivity and selectivity (97). However, ELISA-based assays are commercially available for only certain lipid mediators, typically those that are best characterized for their biological activity. Cross-reactivity of antibodies between lipid mediators is a potential limitation of this technique; thus, antibody specificity should be checked with authentic standards (99).

Amaral et al. revealed that sera levels of RvD1 in BT and LL leprosy patients were similar, but increased in comparison with the sera of healthy individuals (17). Interestingly, after MDT serum levels of RvD1 in BT and LL patients were reduced to those of healthy controls (17). These data indicated that RvD1 is being produced in response to inflammation and possibly also associated with the presence of the pathogen or pathogen products. However, induction of RvD1 production via M. leprae infection has not been investigated.

A comprehensive study to define the biological activity of the D-series resolvins (RvD1 and RvD2) and maresin-1 on the adaptive immune response demonstrated that these SPMs reduce the production of IFN-γ and IL-17 by Th1 and Th17 cells, respectively (26). Moreover, RvD1 was shown to promote the de novo generation of FoxP3+ Treg cells, the expression of CTLA-4 (a surface marker of Treg cells) and IL-10 secretion. The similar levels of RvD1 in BT and LL patients, does not correlate well with this laboratory assessment of RvD1 activity, since BT patients present a strong Th1 and Th17 responses (3, 4, 6) and LL patients are characterized by T-cell anergy and increased frequency of Treg cells (4, 6). Nevertheless, it would be premature to conclude that RvD1 does not participate in the dichotomous immune responses of TT/BT and BL/LL patients. It is possible that the higher level of RvD1 down-modulates the Th1 immune response in TT/BT as well as BL/LL patients. Martins et al. demonstrated that peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from paucibacillary (TT/BT) leprosy patients possess a lower capacity to produce IFN-γ than healthy individuals exposed to M. leprae (3). Thus, the adaptive immune response in TT/BT individuals is still reduced as compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, it could be that RvD1 activity is related to the level of expression of its cognate receptors, GPR32 and ALX/FPR2. Thus, studies that assess the presence of these receptors in the T cells of TT/BT and BL/LL patients are required to fully understand the potential influence of RvD1 on the adaptive immune response across the spectrum of leprosy. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of the ALX/FPR2 gene resulting in a reduced expression of this receptor are known (100, 101). Thus, it would also be interesting to investigate whether polymorphisms exist between TT/BT and BL/LL patients in the promoter or functional regions of the GPR32 and ALX/FPR2 genes.

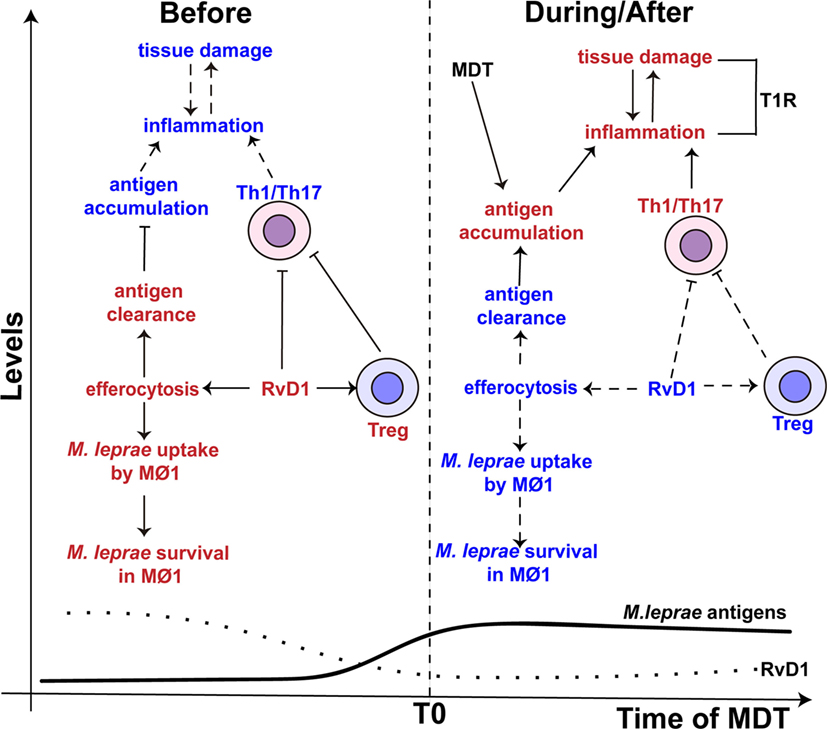

Besides the ability to reduce the activity of Th1 and Th17 cells, RvD1 also controls the activity of macrophages (102, 103). RvD1 induces efferocytosis in monocytes/macrophages (73), a process that engulfs apoptotic cells and is reported to play an important role in the clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium (104, 105). However, De Oliveira and colleagues indicated that this process might promote the persistence of M. leprae (106). Specifically, in the presence of M. leprae, efferocytosis alters the phenotype of the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage toward anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype with increased the uptake and survival of M. leprae. Therefore, in paucibacillary patients, where apoptotic bodies are present in higher number (107, 108), efferocytosis may play an important role in the in vivo persistence of M. leprae. The increased levels of RvD1 in TT/BT patients could help drive this process (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The proposed role of resolvin D1 (RvD1) in leprosy. (Left side) The levels of RvD1 (dotted line) are higher before the start (T0) of multidrug therapy (MDT). The higher levels of RvD1 are hypothesized to increase the host’s susceptibility to M. leprae infection. The increased levels of RvD1 prior to MDT could enhance the capacity of macrophages to engulf M. leprae antigens as well as the pathogen itself via efferocytosis. This would lead to antigen clearance, decreased antigen stimulation of T-helper type 1 (Th1) and T-helper type 17 (Th17) cells and favor the survival of M. leprae. Moreover, increased levels of RvD1 could directly inhibit Th1 and Th17 cells’ response and promote the activity of T regulatory (Treg) cells. (Right side) After the start of MDT, the levels of RvD1 decrease (dotted line), while the abundance of M. leprae antigens increase (solid line) due to lysis and degradation of the bacilli, especially in multi-bacillary patients. The reduction of RvD1 could eliminate the suppression of the Th1 and Th17 responses, reduce the activation of Treg cells, and also decrease the ability of macrophages to promote efferocytosis. This impairment in efferocytosis would favor antigen accumulation. Thus, response to mycobacterial antigens by Th1 and Th17 cells would increase resulting in an immune-inflammatory response and potentially a T1R. The red color represents an intensification or increase in a process or abundance of a product, while the blue color symbolizes an attenuation of the process or product abundance. Arrows with solid lines indicate that a process related to the associated RvD1 level is favored, while an arrow with a hashed line indicates the process is not favored. (⊢) Represents inhibition of a process or activity. MΦ1 – M1, pro-inflammatory macrophages.

Adding to the immunomodulatory activity of efferocytosis, it is recognized that M. leprae inhibits the capacity of macrophage to respond to IFN-γ stimulation (47) and impairs the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α) (109). Macrophages infected with M. leprae have been found to preferentially prime Treg cells over Th1 or cytotoxic T cells (110). Thus, RvD1 may have an additive or synergistic effect on macrophage function that further reduces the innate responses against M. leprae and consequently allows the survival of the pathogen in leprosy patients with a robust Th1 and Th17 cells response (Figure 3). However, studies are required to determine whether RvD1 preferentially drives the response of M. leprae-infected macrophage, as well as enhancement of M. leprae uptake in the context of efferocytosis. While we would hypothesize that RvD1 would influence macrophage polarization in the context of M. leprae infection, the involvement of other lipid mediators in this process cannot be excluded.

T1R is a major complication in borderline leprosy patients (BT, BB, and BL) and occurs before, during and after MDT (111). The increased inflammation of T1R driven by Th1 and Th17 cells in skin lesions and/or nerves can result in permanent loss of nerve function (112, 113).

A higher bacillary load and MDT are factors associated with the development of T1R pathology (114–116). Thus, it has been hypothesized that the release of M. leprae antigens promoted by MDT drive an enhanced immune-inflammatory response, especially in multi-bacillary patients (116, 117). Interestingly, the levels of RvD1 in leprosy patients decrease after the conclusion of MDT (17). Thus, a reduction in circulating SPM may remove suppressive activity being placed on Th1/Th17 cells and contribute to susceptibility of developing T1R in the presence of M. leprae antigens (Figure 3). Recently, a metabolomics study of sera from leprosy patients with and without T1R, and that had not started MDT, confirmed that the level of RvD1 was significantly increased (9.01-fold) in non-T1R leprosy patients as compared to T1R leprosy patients and healthy controls (18). These findings indicate a direct correlation with reduced RvD1 levels and destructive inflammation due to enhanced Th1/Th17 activity and revealed that reduced RvD1 production could occur during active disease.

As the balance of pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators are important in the development and control of inflammation, it is important to note that RvD1 also down-regulates the production of the pro-inflammatory lipid mediator LTB4 (68). LTB4 promotes chemotaxis of Th1 (32) and Th17 cells (33) and enhances the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with Th1 responses (TNF-α and IFN-γ) (22). Although the concentration of LTB4 in BT and LL patients are similar to healthy individuals (17), Silva and colleagues observed a significantly increased level of serum LTB4 during T1R (18). Studies to define the mechanisms of RvD1 activity revealed that this SPM inhibits the translocation of 5-LO to the nucleus and this inhibits the synthesis of LTB4 (68). This mechanism would explain why the levels of LTB4 were not increased in leprosy patients without T1R, but with a reduction of RvD1, they become elevated in T1R patients. However, it does not explain why the levels of LTB4 did not increase after MDT in leprosy patients without T1R since this treatment reduced RvD1 concentrations (17). It is possible that therapeutic elimination of infection reduces signals and stimuli leading to LTB4 production, as well as those that drive RvD1 production.

In conclusion, although increased RvD1 levels may favor M. leprae infection by modulating the protective innate and adaptive immune responses (i.e., bad with it), at the same time, RvD1 is likely important to avoid exacerbated inflammation that may cause skin and nerve injuries. Once the levels of the RvD1 drop in a leprosy patient (e.g., because of MDT or other factors), we hypothesize that this increases susceptibility to pathogenic Th1 and Th17 responses against M. leprae antigens (i.e., worse without it).

The study of Amaral et al. demonstrated that LXA4 is increased in leprosy patients (17). However, the biological function of LXA4 in M. leprae infection is not well understood, but has been studied in M. tuberculosis infection, another model of chronic infectious disease. In the murine model of tuberculosis, Bafica et al. showed that after 1 week of M. tuberculosis infection, LTB4 and LXA4 increase in abundance as compared to uninfected animals, but the levels of LTB4 decrease after 10 days while those of LXA4 persist during chronic M. tuberculosis infection (20). Interestingly, mice deficient for 5-LO (5-lo−/−) did not produce LXA4 increasing the resistance against M. tuberculosis due to higher production of Th1-derived cytokines (INF-γ and IL-12). Conversely, the 5-lo−/− mice treated with a LXA4 analog reduce the levels of Th1 cytokines resulting in increased susceptibility to M. tuberculosis (20). These results indicate that LXA4 has a more predominant effect than LTB4 during M. tuberculosis infection and that a high LXA4 favors the mycobacterial infection. Similar to the animal studies with M. tuberculosis, infection of humans by M. leprae and the presentation of leprosy, are associated with increased levels of LXA4, but not LTB4 (17). This likely reflects the capacity of an M. leprae infection to pass unnoticed for years (1–10 years), presumably due to a protective and non-pathogenic immune response. However, as observed for household contacts, a gradual increase in bacillary load and continuous exposure to antigen, down-modulates the immune response against M. leprae (3, 118). Thus, we hypothesize that the reduced capacity of the host to respond to M. leprae, even during an increase in the bacillary load, is exacerbated by a higher production of LXA4. Once this SPM and RvD1 are produced in sufficient amounts they would inhibit the production of LTB4 (68), and thus elevated levels of LXA4, together with RvD1, might favor the chronic infection of M. leprae.

It is suggested that LTB4 and LXA4 modulate the expression or the effects of TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved with the resistance/susceptibility to leprosy (21, 22, 119). Moreover, an imbalance in the ratio of the pro-resolving LXA4 to pro-inflammatory LTB4 (LXA4/LTB4) is related with a poor control of the immune-inflammatory response in humans (120, 121). Collectively, metabolomics data produced with sera of leprosy patients indicate that the balance between LXA4 and LTB4 is altered (17, 18). However, the mechanisms by which altered ratios of LXA4/LTB4 affect the immunopathology of leprosy remain undefined.

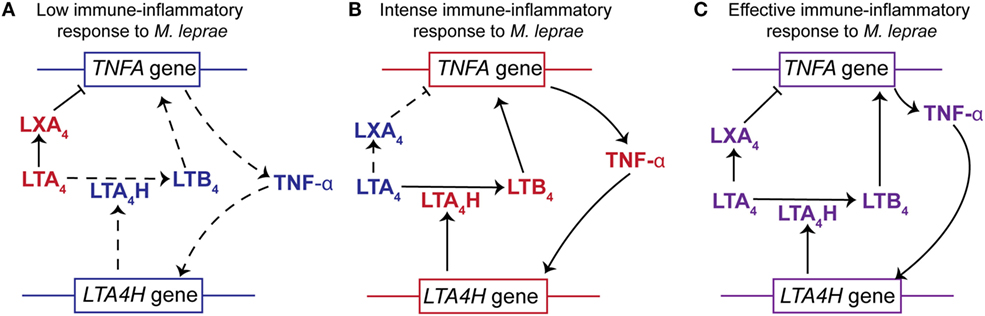

Previous works from Tobin et al. demonstrated that the LXA4/LTB4 ratio was an important factor in susceptibility of zebrafish larvae to Mycobacterium marinum, due to the modulation of TNF-α expression (21, 88, 89). Specifically, shunting LTA4 into LXA4 synthesis resulted in an increase in the LXA4/LTB4 ratio and consequently a down-modulation of TNF-α expression (21, 88, 89). This culminated in a high bacterial burden, death of infected macrophages and increase in the severity of the disease. In contrast, accumulation of LTB4 enhanced TNF-α expression and enabled macrophage control of infection, but an excess of TNF-α results in the necrosis of macrophages and a higher burden of infection (88, 89). Previous findings support a correlation between the levels of TNF-α and LXA4/LTB4 ratio in leprosy patients. Both paucibacillary and multi-bacillary leprosy patients exhibited similar levels of TNF-α, LTB4 and LXA4 (11, 17, 122). On the other hand, leprosy patients with T1R possess a lower LXA4/LTB4 ratio (18), which agrees with increased inflammation and higher levels of TNF-α observed in these patients (123). Thus, the balance between pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators is important to the outcome of infection.

Furthermore, support for the importance of a LXA4/LTB4 balance is provided through population genetics in humans (21). Vietnamese and Nepali individuals homozygous for a common promoter polymorphism at the human LTA4H locus display lower protection against tuberculosis and multi-bacillary leprosy, respectively. This polymorphism is associated with deficient (low activity alleles) or excessive (high activity alleles) expression of the LTA4H gene. Conversely, heterozygous individuals displayed a moderated expression of LTA4H gene and consequently a more balanced production of LXA4 and LTB4, due to the presence of both a low-activity allele and a high-activity allele (21, 88). As a consequence, heterozygous LTA4H individuals exhibited better protection against mycobacteria infection.

The connection between LTA4H and TNF-α is reciprocal, as TNF-α is able to modulate the expression of LTA4H (124–126). This suggests that the synthesis of TNF-α and the LXA4/LTB4 ratio could be regulated by a feedback loop generated by expression of TNFA and LTA4H (details in Figure 4). Interestingly, polymorphisms in the promoter region of the TNFA are associated with human susceptibility to leprosy (119, 127, 128).

Figure 4. The relationships between LTA4H gene polymorphisms, the LXA4/LTB4 ratios and TNF-α production to the outcome of Mycobacterium leprae infection. (A) Individuals homozygous for LTA4H locus with two low activity alleles display a higher concentration of LXA4 than LTB4 (high LXA4/LTB4 ratio). This would impair the production of TNF-α resulting in increased susceptibility to M. leprae. The higher levels of LXA4 not only inhibit the expression of TNFA but also block the immune-inflammatory responses. In addition, the lower levels of TNF-α do not stimulate the expression of LTA4H and therefore do not increase the synthesis of LTB4. (B) Subjects homozygous for LTA4H locus with two high activity alleles display a higher concentration of LTB4 than LXA4 (low LXA4/LTB4 ratio). The increased abundance of LTB4 stimulates the expression of TNFA and production of TNF-α. Increased levels of TNF-α further enhance expression of LTA4H. Thus, an intense immune-inflammatory response to M. leprae would occur resulting in damage to the host tissue. (C) Individuals heterozygous for LTA4H locus, with a high and a low activity allele, synthesize a balanced amount of LXA4 and LTB4 (moderated LXA4/LTB4). This results in the production of TNF-α to levels that promote an effective immune-inflammatory response against M. leprae and promote a balance in the LXA4/LTB4 ratio. This balance in product abundance or gene expression is represented by the purple font. The red font represents an increased abundance of a product or increased gene expression, while the blue font symbolizes an attenuation of product abundance or gene expression. Arrows with solid lines indicate that the production of a lipid mediator or cytokine is favored, while an arrow with a hashed line indicates that the production is not favored. (⊢)Indicates that LXA4 attenuates or impairs the expression of TNF-α.

Existing data strongly support the hypothesis that the LXA4/LTB4 ratio in leprosy disease is an important factor in regulation of TNF-α and hence the susceptibility or resistance to M. leprae infection. We hypothesize that an increase in the LXA4/LTB4 ratio leads to lower TNF-α secretion and reduced control of M. leprae replication (Figure 4). However, a decrease in LXA4/LTB4 ratio would promote higher TNFA expression and an intense inflammatory response as observed for leprosy patients with T1R.

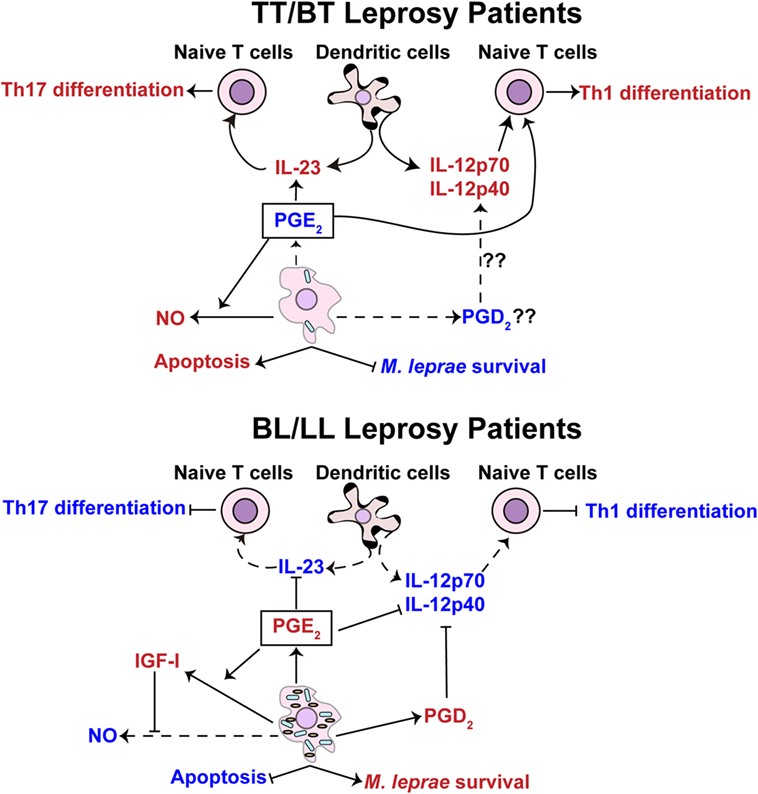

PGE2 and PGD2 are increased in LL patients (17), and previous studies indicate that foamy macrophages/Schwann cells, a classical hallmark of LL patients, are the main source of prostaglandins (129, 130). The higher levels of PGE2 in LL patients (17) together with the lower levels in T1R patients (18) suggest that PGE2 is related to the different clinical forms of leprosy. Indeed, this lipid mediator impairs the proliferation of T cells (39, 40) and inhibits the activation of macrophages by IFN-γ in M. leprae infection (47). Thus, levels of PGE2, produced by foamy macrophages/Schwann cells, can contribute to the inhibition of Th1 responses against M. leprae in LL patients. This may also indicate that lower levels of PGE2 in T1R patients favors the exacerbated acute responses of Th1 cells. Moreover, PGE2 has the ability to augment the suppressive capacity of human CD4+CD25+ Treg cells and up-regulate the expression of transcription factor FOXP3 (46). Garg and colleagues demonstrated that PGE2, but not PGD2, promotes the expansion of Treg cells during M. tuberculosis infection (45). Thus, the higher frequency of Treg cells, as well as the anergy of Th1 and Th17 cells in LL individuals, could be related with increased amounts of PGE2 secreted by foamy macrophages/Schwann cells (Figure 5). Other mechanisms through which higher levels of PGE2 might affect the differentiation of Th17 and Th1 cells in LL patients include, modulating the secretion of IL-23 by dendritic cells (Figure 5) (23) and impairment of IL-12 production by dendritic cells (19).

Figure 5. Prostaglandin E2 is hypothesized to exhibit different functions in pauci- and multi-bacillary leprosy patients. Tuberculoid (TT)/borderline tuberculoid (BT) leprosy patients (top panel) display a lower concentration of PGE2 in comparison with borderline lepromatous (BL)/lepromatous leprosy (LL) patients (lower panel). The lower concentration of PGE2 in TT/BT patients is hypothesized to facilitate the differentiation of T-helper type 17 (Th17) cells through upregulation of interleukin (IL)-23 cytokine production by dendritic cells. Findings from Yao et al. (44) provide evidence that small amounts of PGE2 may favor the differentiation of T-helper type 1 (Th1) cells in TT/BT individuals. The levels of PGE2 in TT/BT patients may also promote the production of nitric oxide (NO) in M. leprae-infected macrophages leading to the control of the bacterial load. In BL/LL patients M. leprae-infected foamy macrophages/Schwann cells produce a higher level of PGE2 that is hypothesized to inhibit the differentiation of Th1 cells through impairment of the production of IL-12p70 by dendritic cells. The higher concentration of PGD2, possibly secreted by foamy macrophages/Schwann cells from BL/LL patients, may also inhibit the production of IL-12p70. Additionally, the increased levels of PGE2 could potentially inhibit the production of IL-23 in dendritic cells, thus blocking the differentiation of Th17 cells. Increased release of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) stimulated via PGE2 might potentially inhibit NO synthesis and apoptosis. The capacity of PGE2 to prevent NO production and apoptosis favors the multiplication of M. leprae. The red color represents an intensification or increase in a process or abundance of a product, while the blue color symbolizes an attenuation of the process or product abundance. Arrows with solid lines indicate processes (production/secretion of cytokines, helper T-cell differentiation, apoptosis, and/or mycobacteria survival) that are favored or induced, while an arrow with a hashed line indicates processes that are not favored. (⊢) Represents inhibition of a process or activity.

There is evidence that at the proper concentration and in the presence of a co-stimulatory signal, PGE2 also stimulates Th1 response. Yao and colleagues showed that treatment of naive T cells with PGE2 and antibody stimulation of CD28 induces the differentiation of Th1 cells (24, 44). It is well known that PGE2, through interaction with EP2 and EP4, inhibits the differentiation of Th1 cells by increasing intracellular levels of cAMP (42, 43). However, with a concomitant stimulation of CD28, T cells are rescued from the inhibitory effects of cAMP and therefore differentiate to Th1 cells (24). Interestingly, M. leprae antigens are able to reduce the expression of B7-1 and CD28 molecules in PBMC cultures from healthy controls (131), and the levels of B7-1 and CD28 molecules in BL/LL patients, but not in BT patients, are reduced. Therefore, the higher levels of PGE2 that leads to an increase in the intracellular levels of cAMP together with lower expression of CD28 could inhibit the differentiation of Th1 cells in LL patients. Conversely, BT patients that secrete basal levels of PGE2 and express higher levels of CD28 would be expected to propagate and maintain a Th1 response. T1R patients also exhibit a basal level of PGE2 (18). Hence, our hypothesis is that lower PGE2 levels promote Th1 and Th17 cell activities in BT and T1R patients, but in LL patients, the higher concentration of this prostaglandin inhibits Th1 and Th17 responses (Figure 5). Together, these studies highlight the controversial role of PGE2 in the human adaptive immune response and underscore the need for studies to determine other possible roles of PGE2 in leprosy.

The prostaglandin PGE2 has been shown to also interfere with the control of cell death (48) and the production of NO by phagocytic cells (41). Studies using an experimental animal model of pulmonary tuberculosis demonstrated that at the early phase of M. tuberculosis infection, BALB/c mice produce lower amounts of PGE2 and this promotes the expression of the inducible form of NO synthase (iNOS). In contrast, at later stage of infection, higher amounts of PGE2 are produced and inhibit the expression of iNOS (41). These assays support the idea that lower production of PGE2 favors the bacterial control, and at higher concentrations, PGE2 inhibits microbicidal mechanisms in the murine model. In line with these observations, skin lesions of BT leprosy patients exhibit a higher expression of iNOS than those of BL patients (11), and macrophages isolated from BT patients secrete higher concentrations of nitrite, a marker for iNOS activity, than macrophages derived from LL patients (132). Thus, we hypothesize that the lower levels of PGE2 in BT patients (17) directly promote the microbicidal activities of phagocytic cells to control M. leprae replication as well as enhance the Th1 responses. Interestingly, the higher production of NO may cause nerve damage in BT patients as hypothesized in previous work (15). On the other hand, higher concentrations of PGE2 secreted by foamy macrophages/Schwann cells would inhibit these same antimicrobial activities and thus favor multi-bacillary disease (Figure 5).

A potential mechanism by which PGE2 would inhibit the production of NO in LL patients is through the induction of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I). PGE2 induces the expression of IGF-I in murine macrophages (133) and osteoblasts (134, 135), and IGF-I inhibits the NOS2 pathway (136). A recent study has demonstrated that increased amounts of IGF-I are found in the skin lesions of LL patients and that IGF-I inhibits signaling cascades required for NO production (137). Therefore, it is possible that the elevated levels of PGE2 could be linked to the inhibition of NO production via the induction of IGF-I in LL patients.

The production of IGF-I, possibly mediated by PGE2, may also promote M. leprae survival by inhibition of apoptosis. Live M. leprae induces the production of IGF-I in Schwann cells and this was found to prevent apoptosis (138). The inhibition of apoptosis could be a significant advantage for M. leprae since this mechanism of cell death promotes the presentation of mycobacterial antigens to T cells (139). Thus, via an IGF-I network, PGE2 may directly impact antigen presentation and favor M. leprae replication (Figure 5). However, a direct functional link between increased IGF-I and PGE2 levels in LL individuals and apoptotic activity needs to be experimentally established.

It is interesting to highlight that the role of PGE2 in M. leprae infection may greatly differ from the function of PGE2 during M. tuberculosis infection. It appears that, during the early phase of infection, virulent M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) inhibits the synthesis of PGE2, by inducing synthesis of LXA4, to prevent apoptosis and consequently inhibit early T-cell activation and promote necrosis of macrophages (48, 49, 139, 140). In contrast, at the chronic stage, PGE2 is highly produced (41), which could control the bacillary load by apoptosis. Furthermore, macrophages infected by the avirulent strain of M. tuberculosis (H37Ra) produced increased levels of PGE2 (48), promoting the protection against mitochondrial inner membrane perturbation and induced plasma membrane repair, crucial processes to avoid necrosis and induce apoptosis (48, 49). Thus, PGE2 might be crucial for the resistance against M. tuberculosis but promote susceptibility to M. leprae. These possible differences between M. tuberculosis and M. leprae infections could be partially related with different modulation of EP1-4 receptors by the two pathogens and should be explored in future studies.

Based on the several findings regarding PGD2 and its effects on the modulation of T cells we suggest that PGD2 production via foamy macrophages/Schwann cells promotes Th2 response in LL patients. It is well established that PGD2 decreases the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that produce IFN-γ and IL-2, through interactions with the DP1 receptor, while contributing to the Th2 responses with induction of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 by binding the CRTH2 receptor (60, 61). Besides a direct effect on T cells, PGD2 modulates the T-cell response through dendritic cells and their production of IL-12 (19, 59). Braga et al. has revealed that monocyte-derived dendritic cells from LL patients produced less IL-12 (25), and although a direct association has not been made, the decreased IL-12 levels in LL patients could be driven by increased PGD2 production and secretion by foamy macrophages/Schwann cells (Figure 5).

One observation that does not fit with the PGD2 immune suppressing scenario in leprosy is that PGD2 levels increase during a T1R (18). T1R is considered a delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction (141) and several works indicate that PGD2, or its metabolite 15d-PGJ2 (142), is highly produced during DTH to control the inflammatory activity in animal models (143). Thus, the increasing of PGD2 in T1R patients may be a response by the host to control inflammation.

Individuals with acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, an autoimmune disease that directly attack the peripheral nerve myelin (144), have increased levels of PGD synthase enzyme in their cerebrospinal fluid (145). In a murine model of spinal cord contusion injury, the levels of PGD synthase are also elevated (146). Interestingly, although the expression of PGD synthase was never determined, COX-2 is increased during T1R (147, 148). Thus, an increase in PGD2 is not unexpected during T1R as these leprosy patients suffer the most severe nerve damage. PGD2 is known to promote the myelination of neurons (55). In addition, mice that lack PGD synthase are unable to promote myelination of the neurons. These studies, as well as the fact that mast cells that are in close proximity to the peripheral nerve fibers in the tissue are the major producers of PGD2, support the hypothesis that increased PGD2 is a consequence of the T1R in leprosy and not a driver of the pathology.

Given the potentially varied activities of PGD2 at different stages of leprosy, it is important to determine not only the source of this prostaglandin, foamy macrophages/Schwann cells versus mast cells, but also the receptors that bind PGD2 during the different manifestations of leprosy and the cells that are expressing these receptors. Additionally, PGD2 potentiates the formation of edema (56, 57), a factor that might contribute to the nerve damage in leprosy (149). Therefore, further studies are required to determine if PGD2, through edema formation, can contribute to the pathology of leprosy lesions.

Through the multiple metabolomics studies performed with clinical samples from leprosy patients it is clear that alterations in the metabolism of lipid mediators derived from ω3 and ω6 PUFA occur with this disease. However, there is a lack of research that directly links these lipid mediators to the breadth of immune responses that occur across the clinical manifestations of leprosy. Detailed investigations to define enzymes and biochemical pathways for lipid mediator synthesis, along with elucidation of lipid mediator receptors and mechanisms by which lipid mediators influence both innate and adaptive immune responses, has nevertheless allowed the development of well supported hypothesis on the function of various lipid mediators in different manifestations of leprosy. A common theme that has emerged from existing studies is that several of the lipid mediators identified in the metabolomics studies of leprosy patients and discussed here (RvD1, LXA4, PGE2, and PGD2) down-regulate the immune-inflammatory responses promoted by Th1 and Th17 cells and facilitate the activity and proliferation Treg cells. This would indicate that M. leprae might exploit the pro-resolving activities of lipid meditators to maintain a persistent infection. Nonetheless, some of these lipid mediators such as PGE2 and PGD2, as well as LTB4 can influence the protective response against M. leprae. Another emerging theme is that alteration of the balance between pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators has the potential to dramatically skew the Th1/Th17 and Treg responses in leprosy. This same concept also applies to variations in the relative concentration of individual products such as PGE2. Thus, a coordination of the dynamics of the lipid mediator response and that of the adaptive and innate immune systems seems to be a driving factor in the specific presentation of leprosy.

As existing and future data are interpreted to develop models of lipid mediator involvement in the pathology and immunology of leprosy, it is important to consider the complexity of lipid mediator metabolism, and that most lipid mediators can serve as ligands for multiple receptors. Additionally, the spatial and temporal aspects of lipid mediator metabolism and receptor expression, along with the complementary or opposing activities of multiple lipid mediators must be addressed to fully elucidate the role lipid mediators play in leprosy. Mathematical models, as performed for M. tuberculosis infection (150), may be important to elucidate the influence PUFA-derived lipid mediator complexity in disease outcomes that might occur in individuals infected with M. leprae. It is also important to highlight that lipid mediators not identified or targeted in previous metabolomics studies on leprosy, may also contribute to immuno-pathogenesis. Thus, further targeted metabolomics investigations supported by orthogonal approaches, such as transcriptomics and proteomics, are needed to elucidate the full complement lipid mediators involved in leprosy and define how systemic alterations in their levels modify the phenotype of innate and adaptive immune cells in different presentations of leprosy. Future research efforts will not only provide an understanding of the contribution of lipid mediators to chronic infectious diseases but also provide the basis for the development of new diagnostic/prognostic and treatment approaches to address leprosy as a public health problem.

CS and JB contributed to the review of published literature, development of the concepts, and design of the review article, as well as the writing and editing of the manuscript. CS is responsible for the design and concepts of the figures.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer OM and handling editor declared their shared affiliation.

This work was supported by the Heiser Foundation for Leprosy Research of the New York Community Trust, grants P15-000827 and P16-000796 to JB as co-principle investigator (PI) and by the Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel through the Science without Borders program (10546-13-8, for the postdoctoral scholarship to CS).

1. WHO. Global leprosy update, 2015: time for action, accountability and inclusion. Wkly Epidemiol Rec (2016) 91(35):405–20.

2. Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis (1966) 34(3):255–73.

3. Martins MV, Guimaraes MM, Spencer JS, Hacker MA, Costa LS, Carvalho FM, et al. Pathogen-specific epitopes as epidemiological tools for defining the magnitude of Mycobacterium leprae transmission in areas endemic for leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2012) 6(4):e1616. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001616

4. Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, Bekele Y, Zewdie M, van der Ploeg-van Schip JJ, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2014) 8(4):e2773. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002773

5. Herbst S, Schaible UE, Schneider BE. Interferon gamma activated macrophages kill mycobacteria by nitric oxide induced apoptosis. PLoS One (2011) 6(5):e19105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019105

6. Sadhu S, Khaitan BK, Joshi B, Sengupta U, Nautiyal AK, Mitra DK. Reciprocity between regulatory T cells and Th17 cells: relevance to polarized immunity in leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2016) 10(1):e0004338. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004338

7. Bettelli E, Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. Induction and effector functions of T(H)17 cells. Nature (2008) 453(7198):1051–7. doi:10.1038/nature07036

8. Yamamura M, Uyemura K, Deans RJ, Weinberg K, Rea TH, Bloom BR, et al. Defining protective responses to pathogens: cytokine profiles in leprosy lesions. Science (1991) 254(5029):277–9. doi:10.1126/science.1925582

9. Nogueira N, Kaplan G, Levy E, Sarno EN, Kushner P, Granelli-Piperno A, et al. Defective gamma interferon production in leprosy. Reversal with antigen and interleukin 2. J Exp Med (1983) 158(6):2165–70. doi:10.1084/jem.158.6.2165

10. Misra N, Murtaza A, Walker B, Narayan NP, Misra RS, Ramesh V, et al. Cytokine profile of circulating T cells of leprosy patients reflects both indiscriminate and polarized T-helper subsets: T-helper phenotype is stable and uninfluenced by related antigens of Mycobacterium leprae. Immunology (1995) 86(1):97–103.

11. Venturini J, Soares CT, Belone Ade F, Barreto JA, Ura S, Lauris JR, et al. In vitro and skin lesion cytokine profile in Brazilian patients with borderline tuberculoid and borderline lepromatous leprosy. Lepr Rev (2011) 82(1):25–35.

12. Spierings E, De Boer T, Zulianello L, Ottenhoff TH. Novel mechanisms in the immunopathogenesis of leprosy nerve damage: the role of Schwann cells, T cells and Mycobacterium leprae. Immunol Cell Biol (2000) 78(4):349–55. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00939.x

13. Spierings E, de Boer T, Wieles B, Adams LB, Marani E, Ottenhoff TH. Mycobacterium leprae-specific, HLA class II-restricted killing of human Schwann cells by CD4+ Th1 cells: a novel immunopathogenic mechanism of nerve damage in leprosy. J Immunol (2001) 166(10):5883–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.5883

14. Renault C, Ernst J. Mycobacterium leprae (leprosy). In: Bennet J, Dolin R, Blaser M, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Infectious Disease Essentials. Philadelphia: Elsevier (2015). p. 2819–31.

15. Madigan CA, Cambier CJ, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Scumpia PO, Cheng TY, Zailaa J, et al. A macrophage response to Mycobacterium leprae phenolic glycolipid initiates nerve damage in leprosy. Cell (2017) 170(5):973–85.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.030

16. Al-Mubarak R, Vander Heiden J, Broeckling CD, Balagon M, Brennan PJ, Vissa VD. Serum metabolomics reveals higher levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids in lepromatous leprosy: potential markers for susceptibility and pathogenesis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2011) 5(9):e1303. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001303

17. Amaral JJ, Antunes LC, de Macedo CS, Mattos KA, Han J, Pan J, et al. Metabonomics reveals drastic changes in anti-inflammatory/pro-resolving polyunsaturated fatty acids-derived lipid mediators in leprosy disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2013) 7(8):e2381. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002381

18. Silva CA, Webb K, Andre BG, Marques MA, de Carvalho FM, de Macedo CS, et al. Type 1 reaction in leprosy patients corresponds with a decrease in pro-resolving and an increase in pro-inflammatory lipid mediators. J Infect Dis (2017) 215(3):431–9. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw541

19. Gosset P, Bureau F, Angeli V, Pichavant M, Faveeuw C, Tonnel AB, et al. Prostaglandin D2 affects the maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells: consequence on the polarization of naive Th cells. J Immunol (2003) 170(10):4943–52. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4943

20. Bafica A, Scanga CA, Serhan C, Machado F, White S, Sher A, et al. Host control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is regulated by 5-lipoxygenase-dependent lipoxin production. J Clin Invest (2005) 115(6):1601–6. doi:10.1172/jci23949

21. Tobin DM, Vary JC Jr, Ray JP, Walsh GS, Dunstan SJ, Bang ND, et al. The lta4h locus modulates susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in zebrafish and humans. Cell (2010) 140(5):717–30. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.013

22. Toda A, Terawaki K, Yamazaki S, Saeki K, Shimizu T, Yokomizo T. Attenuated Th1 induction by dendritic cells from mice deficient in the leukotriene B4 receptor 1. Biochimie (2010) 92(6):682–91. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2009.12.002

23. Poloso NJ, Urquhart P, Nicolaou A, Wang J, Woodward DF. PGE2 differentially regulates monocyte-derived dendritic cell cytokine responses depending on receptor usage (EP2/EP4). Mol Immunol (2013) 54(3–4):284–95. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2012.12.010

24. Yao C, Hirata T, Soontrapa K, Ma X, Takemori H, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E(2) promotes Th1 differentiation via synergistic amplification of IL-12 signalling by cAMP and PI3-kinase. Nat Commun (2013) 4:1685. doi:10.1038/ncomms2684

25. Braga AF, Moretto DF, Gigliotti P, Peruchi M, Vilani-Moreno FR, Campanelli AP, et al. Activation and cytokine profile of monocyte derived dendritic cells in leprosy: in vitro stimulation by sonicated Mycobacterium leprae induces decreased level of IL-12p70 in lepromatous leprosy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz (2015) 110(5):655–61. doi:10.1590/0074-02760140230

26. Chiurchiu V, Leuti A, Dalli J, Jacobsson A, Battistini L, Maccarrone M, et al. Proresolving lipid mediators resolvin D1, resolvin D2, and maresin 1 are critical in modulating T cell responses. Sci Transl Med (2016) 8(353):353ra111. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf7483

27. Lone AM, Tasken K. Proinflammatory and immunoregulatory roles of eicosanoids in T cells. Front Immunol (2013) 4:130. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2013.00130

28. Serhan CN, Chiang N, Dalli J. The resolution code of acute inflammation: novel pro-resolving lipid mediators in resolution. Semin Immunol (2015) 27(3):200–15. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.004

29. Harizi H, Corcuff JB, Gualde N. Arachidonic-acid-derived eicosanoids: roles in biology and immunopathology. Trends Mol Med (2008) 14(10):461–9. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2008.08.005

30. Tager AM, Luster AD. BLT1 and BLT2: the leukotriene B(4) receptors. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids (2003) 69(2–3):123–34. doi:10.1016/S0952-3278(03)00073-5

31. Yokomizo T. Leukotriene B4 receptors: novel roles in immunological regulations. Adv Enzyme Regul (2011) 51(1):59–64. doi:10.1016/j.advenzreg.2010.08.002

32. Tager AM, Bromley SK, Medoff BD, Islam SA, Bercury SD, Friedrich EB, et al. Leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 mediates early effector T cell recruitment. Nat Immunol (2003) 4(10):982–90. doi:10.1038/ni970

33. Lee W, Su Kim H, Lee GR. Leukotrienes induce the migration of Th17 cells. Immunol Cell Biol (2015) 93(5):472–9. doi:10.1038/icb.2014.104

34. Norel X. Prostanoid receptors in the human vascular wall. ScientificWorldJournal (2007) 7:1359–74. doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.184

35. Harizi H, Grosset C, Gualde N. Prostaglandin E2 modulates dendritic cell function via EP2 and EP4 receptor subtypes. J Leukoc Biol (2003) 73(6):756–63. doi:10.1189/jlb.1002483

36. Panzer U, Uguccioni M. Prostaglandin E2 modulates the functional responsiveness of human monocytes to chemokines. Eur J Immunol (2004) 34(12):3682–9. doi:10.1002/eji.200425226

37. Kawahara K, Hohjoh H, Inazumi T, Tsuchiya S, Sugimoto Y. Prostaglandin E2-induced inflammation: relevance of prostaglandin E receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta (2015) 1851(4):414–21. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.07.008

38. Kalinski P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J Immunol (2012) 188(1):21–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101029

39. Bahr GM, Rook GA, Stanford JL. Prostaglandin-dependent regulation of the in vitro proliferative response to mycobacterial antigens of peripheral blood lymphocytes from normal donors and from patients with tuberculosis or leprosy. Clin Exp Immunol (1981) 45(3):646–53.

40. Misra N, Selvakumar M, Singh S, Bharadwaj M, Ramesh V, Misra RS, et al. Monocyte derived IL 10 and PGE2 are associated with the absence of Th 1 cells and in vitro T cell suppression in lepromatous leprosy. Immunol Lett (1995) 48(2):123–8. doi:10.1016/0165-2478(95)02455-7

41. Rangel Moreno J, Estrada Garcia I, De La Luz Garcia Hernandez M, Aguilar Leon D, Marquez R, Hernandez Pando R. The role of prostaglandin E2 in the immunopathogenesis of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology (2002) 106(2):257–66. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01403.x

42. Betz M, Fox BS. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits production of Th1 lymphokines but not of Th2 lymphokines. J Immunol (1991) 146(1):108–13.

43. van der Pouw Kraan TC, Boeije LC, Smeenk RJ, Wijdenes J, Aarden LA. Prostaglandin-E2 is a potent inhibitor of human interleukin 12 production. J Exp Med (1995) 181(2):775–9. doi:10.1084/jem.181.2.775

44. Yao C, Sakata D, Esaki Y, Li Y, Matsuoka T, Kuroiwa K, et al. Prostaglandin E2-EP4 signaling promotes immune inflammation through Th1 cell differentiation and Th17 cell expansion. Nat Med (2009) 15(6):633–40. doi:10.1038/nm.1968

45. Garg A, Barnes PF, Roy S, Quiroga MF, Wu S, Garcia VE, et al. Mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan- and prostaglandin E2-dependent expansion of regulatory T cells in human Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Eur J Immunol (2008) 38(2):459–69. doi:10.1002/eji.200737268

46. Baratelli F, Lin Y, Zhu L, Yang SC, Heuze-Vourc’h N, Zeng G, et al. Prostaglandin E2 induces FOXP3 gene expression and T regulatory cell function in human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol (2005) 175(3):1483–90. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1483

47. Sibley LD, Krahenbuhl JL. Induction of unresponsiveness to gamma interferon in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun (1988) 56(8):1912–9.

48. Chen M, Divangahi M, Gan H, Shin DS, Hong S, Lee DM, et al. Lipid mediators in innate immunity against tuberculosis: opposing roles of PGE2 and LXA4 in the induction of macrophage death. J Exp Med (2008) 205(12):2791–801. doi:10.1084/jem.20080767

49. Divangahi M, Chen M, Gan H, Desjardins D, Hickman TT, Lee DM, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis evades macrophage defenses by inhibiting plasma membrane repair. Nat Immunol (2009) 10(8):899–906. doi:10.1038/ni.1758

50. Taketomi Y, Ueno N, Kojima T, Sato H, Murase R, Yamamoto K, et al. Mast cell maturation is driven via a group III phospholipase A2-prostaglandin D2-DP1 receptor paracrine axis. Nat Immunol (2013) 14(6):554–63. doi:10.1038/ni.2586

51. Nagata K, Hirai H, Tanaka K, Ogawa K, Aso T, Sugamura K, et al. CRTH2, an orphan receptor of T-helper-2-cells, is expressed on basophils and eosinophils and responds to mast cell-derived factor(s). FEBS Lett (1999) 459(2):195–9. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01251-X

52. Nagata K, Tanaka K, Ogawa K, Kemmotsu K, Imai T, Yoshie O, et al. Selective expression of a novel surface molecule by human Th2 cells in vivo. J Immunol (1999) 162(3):1278–86.

53. Tajima T, Murata T, Aritake K, Urade Y, Hirai H, Nakamura M, et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces macrophage migration via prostaglandin D(2) and prostaglandin E(2). J Pharmacol Exp Ther (2008) 326(2):493–501. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.137992

54. Moon TC, Campos-Alberto E, Yoshimura T, Bredo G, Rieger AM, Puttagunta L, et al. Expression of DP2 (CRTh2), a prostaglandin D(2) receptor, in human mast cells. PLoS One (2014) 9(9):e108595. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108595

55. Trimarco A, Forese MG, Alfieri V, Lucente A, Brambilla P, Dina G, et al. Prostaglandin D2 synthase/GPR44: a signaling axis in PNS myelination. Nat Neurosci (2014) 17(12):1682–92. doi:10.1038/nn.3857

56. Flower RJ, Harvey EA, Kingston WP. Inflammatory effects of prostaglandin D2 in rat and human skin. Br J Pharmacol (1976) 56(2):229–33. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb07446.x

57. Whelan CJ, Head SA, Poll CT, Coleman RA. Prostaglandin (PG) modulation of bradykinin-induced hyperalgesia and oedema in the guinea-pig paw – effects of PGD2, PGE2 and PGI2. Agents Actions Suppl (1991) 32:107–11.

58. Joo M, Sadikot RT. PGD synthase and PGD2 in immune resposne. Mediators Inflamm (2012) 2012:503128. doi:10.1155/2012/503128

59. Theiner G, Gessner A, Lutz MB. The mast cell mediator PGD2 suppresses IL-12 release by dendritic cells leading to Th2 polarized immune responses in vivo. Immunobiology (2006) 211(6–8):463–72. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.020

60. Tanaka K, Hirai H, Takano S, Nakamura M, Nagata K. Effects of prostaglandin D2 on helper T cell functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2004) 316(4):1009–14. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.151

61. Xue L, Gyles SL, Wettey FR, Gazi L, Townsend E, Hunter MG, et al. Prostaglandin D2 causes preferential induction of proinflammatory Th2 cytokine production through an action on chemoattractant receptor-like molecule expressed on Th2 cells. J Immunol (2005) 175(10):6531–6. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6531

62. Hirai H, Tanaka K, Yoshie O, Ogawa K, Kenmotsu K, Takamori Y, et al. Prostaglandin D2 selectively induces chemotaxis in T helper type 2 cells, eosinophils, and basophils via seven-transmembrane receptor CRTH2. J Exp Med (2001) 193(2):255–61. doi:10.1084/jem.193.2.255

63. Krishnamoorthy S, Recchiuti A, Chiang N, Yacoubian S, Lee CH, Yang R, et al. Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107(4):1660–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907342107

64. Lee TH, Horton CE, Kyan-Aung U, Haskard D, Crea AE, Spur BW. Lipoxin A4 and lipoxin B4 inhibit chemotactic responses of human neutrophils stimulated by leukotriene B4 and N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine. Clin Sci (Lond) (1989) 77(2):195–203. doi:10.1042/cs0770195

65. Godson C, Mitchell S, Harvey K, Petasis NA, Hogg N, Brady HR. Cutting edge: lipoxins rapidly stimulate nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by monocyte-derived macrophages. J Immunol (2000) 164(4):1663–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1663

66. Schwab JM, Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 and protectin D1 activate inflammation-resolution programmes. Nature (2007) 447(7146):869–74. doi:10.1038/nature05877

67. Borgeson E, Johnson AM, Lee YS, Till A, Syed GH, Ali-Shah ST, et al. Lipoxin A4 attenuates obesity-induced adipose inflammation and associated liver and kidney disease. Cell Metab (2015) 22(1):125–37. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.003

68. Fredman G, Ozcan L, Spolitu S, Hellmann J, Spite M, Backs J, et al. Resolvin D1 limits 5-lipoxygenase nuclear localization and leukotriene B4 synthesis by inhibiting a calcium-activated kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111(40):14530–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410851111

69. Serhan CN, Chiang N, Dalli J, Levy BD. Lipid mediators in the resolution of inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2015) 7(2):a016311. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016311

70. Claria J, Dalli J, Yacoubian S, Gao F, Serhan CN. Resolvin D1 and resolvin D2 govern local inflammatory tone in obese fat. J Immunol (2012) 189(5):2597–605. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201272

71. Liu G, Fiala M, Mizwicki MT, Sayre J, Magpantay L, Siani A, et al. Neuronal phagocytosis by inflammatory macrophages in ALS spinal cord: inhibition of inflammation by resolvin D1. Am J Neurodegener Dis (2012) 1(1):60–74.

72. Miki Y, Yamamoto K, Taketomi Y, Sato H, Shimo K, Kobayashi T, et al. Lymphoid tissue phospholipase A2 group IID resolves contact hypersensitivity by driving antiinflammatory lipid mediators. J Exp Med (2013) 210(6):1217–34. doi:10.1084/jem.20121887

73. Lee HN, Kundu JK, Cha YN, Surh YJ. Resolvin D1 stimulates efferocytosis through p50/p50-mediated suppression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression. J Cell Sci (2013) 126(Pt 17):4037–47. doi:10.1242/jcs.131003

74. Astudillo AM, Balgoma D, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. Dynamics of arachidonic acid mobilization by inflammatory cells. Biochim Biophys Acta (2012) 1821(2):249–56. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.11.006

75. Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol (2011) 31(5):986–1000. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.110.207449

76. Harris SG, Phipps RP. Prostaglandin D(2), its metabolite 15-d-PGJ(2), and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma agonists induce apoptosis in transformed, but not normal, human T lineage cells. Immunology (2002) 105(1):23–34. doi:10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01340.x

77. Arima M, Fukuda T. Prostaglandin D(2) and T(H)2 inflammation in the pathogenesis of bronchial asthma. Korean J Intern Med (2011) 26(1):8–18. doi:10.3904/kjim.2011.26.1.8

78. Corey EJ, Lansbury PT Jr. Stereochemical course of 5-lipoxygenation of arachidonate by rat basophil leukemic cell (RBL-1) and potato enzymes. J Am Chem Soc (1983) 105(12):4093–4. doi:10.1021/ja00350a059

79. Shimizu T, Radmark O, Samuelsson B. Enzyme with dual lipoxygenase activities catalyzes leukotriene A4 synthesis from arachidonic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1984) 81(3):689–93. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.3.689

80. Skoog MT, Nichols JS, Wiseman JS. 5-lipoxygenase from rat PMN lysate. Prostaglandins (1986) 31(3):561–76. doi:10.1016/0090-6980(86)90117-6

81. Ueda N, Kaneko S, Yoshimoto T, Yamamoto S. Purification of arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase from porcine leukocytes and its reactivity with hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids. J Biol Chem (1986) 261(17):7982–8.

82. Wiseman JS, Skoog MT, Nichols JS, Harrison BL. Kinetics of leukotriene A4 synthesis by 5-lipoxygenase from rat polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochemistry (1987) 26(18):5684–9. doi:10.1021/bi00392a016

83. Radmark O, Werz O, Steinhilber D, Samuelsson B. 5-Lipoxygenase, a key enzyme for leukotriene biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta (2015) 1851(4):331–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.012

84. Serhan CN, Hamberg M, Samuelsson B. Lipoxins: novel series of biologically active compounds formed from arachidonic acid in human leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1984) 81(17):5335–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.17.5335

85. Serhan CN, Sheppard KA. Lipoxin formation during human neutrophil-platelet interactions. Evidence for the transformation of leukotriene A4 by platelet 12-lipoxygenase in vitro. J Clin Invest (1990) 85(3):772–80. doi:10.1172/jci114503

86. Yokomizo T. Two distinct leukotriene B4 receptors, BLT1 and BLT2. J Biochem (2015) 157(2):65–71. doi:10.1093/jb/mvu078

87. Brach MA, de Vos S, Arnold C, Gruss HJ, Mertelsmann R, Herrmann F. Leukotriene B4 transcriptionally activates interleukin-6 expression involving NK-chi B and NF-IL6. Eur J Immunol (1992) 22(10):2705–11. doi:10.1002/eji.1830221034

88. Tobin DM, Roca FJ, Oh SF, McFarland R, Vickery TW, Ray JP, et al. Host genotype-specific therapies can optimize the inflammatory response to mycobacterial infections. Cell (2012) 148(3):434–46. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.023

89. Tobin DM, Roca FJ, Ray JP, Ko DC, Ramakrishnan L. An enzyme that inactivates the inflammatory mediator leukotriene b4 restricts mycobacterial infection. PLoS One (2013) 8(7):e67828. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067828

90. Pezato R, Swierczynska-Krepa M, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Derycke L, Bachert C, Perez-Novo CA. Role of imbalance of eicosanoid pathways and staphylococcal superantigens in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy (2012) 67(11):1347–56. doi:10.1111/all.12010

91. Das UN. Essential fatty acids: biochemistry, physiology and pathology. Biotechnol J (2006) 1(4):420–39. doi:10.1002/biot.200600012

92. Borgne F, Demarquoy J. Interaction between peroxisomes and mitochondria in fatty acid metabolism. Open J Mol Integr Physiol (2012) 2:27–33. doi:10.4236/ojmip.2012.21005

93. Yang R, Chiang N, Oh SF, Serhan CN. Metabolomics-lipidomics of eicosanoids and docosanoids generated by phagocytes. Curr Protoc Immunol (2011) Chapter 14:Unit 14.26. doi:10.1002/0471142735.im1426s95

94. Tsikas D, Zoerner AA. Analysis of eicosanoids by LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS: a historical retrospect and a discussion. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci (2014) 964:79–88. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.03.017

95. Le Faouder P, Baillif V, Spreadbury I, Motta JP, Rousset P, Chene G, et al. LC-MS/MS method for rapid and concomitant quantification of pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci (2013) 932:123–33. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.06.014

96. Deems R, Buczynski MW, Bowers-Gentry R, Harkewicz R, Dennis EA. Detection and quantitation of eicosanoids via high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol (2007) 432:59–82. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(07)32003-x

97. Lu Y, Hong S, Gotlinger K, Serhan CN. Lipid mediator informatics and proteomics in inflammation resolution. ScientificWorldJournal (2006) 6:589–614. doi:10.1100/tsw.2006.118

98. Serhan CN, Hong S, Gronert K, Colgan SP, Devchand PR, Mirick G, et al. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med (2002) 196(8):1025–37. doi:10.1084/jem.20020760

99. Chiang N, Bermudez EA, Ridker PM, Hurwitz S, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers antiinflammatory 15-epi-lipoxin A4 and inhibits thromboxane in a randomized human trial. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2004) 101(42):15178–83. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405445101

100. Simiele F, Recchiuti A, Mattoscio D, De Luca A, Cianci E, Franchi S, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the human FPR2/ALX gene: evidence of a heritable genetic variant that impairs promoter activity. FASEB J (2012) 26(3):1323–33. doi:10.1096/fj.11-198069

101. Zhang H, Lu Y, Sun G, Teng F, Luo N, Jiang J, et al. The common promoter polymorphism rs11666254 downregulates FPR2/ALX expression and increases risk of sepsis in patients with severe trauma. Crit Care (2017) 21(1):171. doi:10.1186/s13054-017-1757-3

102. Titos E, Rius B, Gonzalez-Periz A, Lopez-Vicario C, Moran-Salvador E, Martinez-Clemente M, et al. Resolvin D1 and its precursor docosahexaenoic acid promote resolution of adipose tissue inflammation by eliciting macrophage polarization toward an M2-like phenotype. J Immunol (2011) 187(10):5408–18. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1100225

103. Chiang N, Fredman G, Backhed F, Oh SF, Vickery T, Schmidt BA, et al. Infection regulates pro-resolving mediators that lower antibiotic requirements. Nature (2012) 484(7395):524–8. doi:10.1038/nature11042

104. Martin CJ, Booty MG, Rosebrock TR, Nunes-Alves C, Desjardins DM, Keren I, et al. Efferocytosis is an innate antibacterial mechanism. Cell Host Microbe (2012) 12(3):289–300. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.010

105. Martin CJ, Peters KN, Behar SM. Macrophages clean up: efferocytosis and microbial control. Curr Opin Microbiol (2014) 17:17–23. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2013.10.007

106. de Oliveira Fulco T, Andrade PR, de Mattos Barbosa MG, Pinto TG, Ferreira PF, Ferreira H, et al. Effect of apoptotic cell recognition on macrophage polarization and mycobacterial persistence. Infect Immun (2014) 82(9):3968–78. doi:10.1128/iai.02194-14

107. Walsh DS, Lane JE, Abalos RM, Myint KS. TUNEL and limited immunophenotypic analyses of apoptosis in paucibacillary and multibacillary leprosy lesions. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol (2004) 41(3):265–9. doi:10.1016/j.femsim.2004.04.002

108. Brito de Souza VN, Nogueira ME, Belone Ade F, Soares CT. Analysis of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression in polar forms of leprosy. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol (2010) 60(3):270–4. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00746.x

109. Fallows D, Peixoto B, Kaplan G, Manca C. Mycobacterium leprae alters classical activation of human monocytes in vitro. J Inflamm (Lond) (2016) 13:8. doi:10.1186/s12950-016-0117-4

110. Yang D, Shui T, Miranda JW, Gilson DJ, Song Z, Chen J, et al. Mycobacterium leprae-infected macrophages preferentially primed regulatory T cell responses and was associated with lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2016) 10(1):e0004335. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004335

111. Walker SL, Lockwood DN. Leprosy type 1 (reversal) reactions and their management. Lepr Rev (2008) 79(4):372–86.

112. Geluk A, van Meijgaarden KE, Wilson L, Bobosha K, van der Ploeg-van Schip JJ, van den Eeden SJ, et al. Longitudinal immune responses and gene expression profiles in type 1 leprosy reactions. J Clin Immunol (2014) 34(2):245–55. doi:10.1007/s10875-013-9979-x

113. Khadge S, Banu S, Bobosha K, van der Ploeg-van Schip JJ, Goulart IM, Thapa P, et al. Longitudinal immune profiles in type 1 leprosy reactions in Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia and Nepal. BMC Infect Dis (2015) 15:477. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1128-0

114. Ranque B, Nguyen VT, Vu HT, Nguyen TH, Nguyen NB, Pham XK, et al. Age is an important risk factor for onset and sequelae of reversal reactions in Vietnamese patients with leprosy. Clin Infect Dis (2007) 44(1):33–40. doi:10.1086/509923

115. Scollard DM, Martelli CM, Stefani MM, Maroja Mde F, Villahermosa L, Pardillo F, et al. Risk factors for leprosy reactions in three endemic countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg (2015) 92(1):108–14. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0221

116. Suchonwanit P, Triamchaisri S, Wittayakornrerk S, Rattanakaemakorn P. Leprosy reaction in Thai population: a 20-year retrospective study. Dermatol Res Pract (2015) 2015:253154. doi:10.1155/2015/253154

117. Spencer JS, Duthie MS, Geluk A, Balagon MF, Kim HJ, Wheat WH, et al. Identification of serological biomarkers of infection, disease progression and treatment efficacy for leprosy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz (2012) 107(Suppl 1):79–89. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762012000900014

118. Reis EM, Araujo S, Lobato J, Neves AF, Costa AV, Goncalves MA, et al. Mycobacterium leprae DNA in peripheral blood may indicate a bacilli migration route and high-risk for leprosy onset. Clin Microbiol Infect (2014) 20(5):447–52. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12349

119. Tarique M, Naqvi RA, Santosh KV, Kamal VK, Khanna N, Rao DN. Association of TNF-alpha-(308(GG)), IL-10(-819(TT)), IL-10(-1082(GG)) and IL-1R1(+1970(CC)) genotypes with the susceptibility and progression of leprosy in North Indian population. Cytokine (2015) 73(1):61–5. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2015.01.014

120. Balode L, Strazda G, Jurka N, Kopeika U, Kislina A, Bukovskis M, et al. Lipoxygenase-derived arachidonic acid metabolites in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medicina (Kaunas) (2012) 48(6):292–8.

121. Ringholz FC, Buchanan PJ, Clarke DT, Millar RG, McDermott M, Linnane B, et al. Reduced 15-lipoxygenase 2 and lipoxin A4/leukotriene B4 ratio in children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J (2014) 44(2):394–404. doi:10.1183/09031936.00106013

122. Parida SK, Grau GE, Zaheer SA, Mukherjee R. Serum tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 in leprosy and during lepra reactions. Clin Immunol Immunopathol (1992) 63(1):23–7. doi:10.1016/0090-1229(92)90088-6

123. Chaitanya VS, Lavania M, Nigam A, Turankar RP, Singh I, Horo I, et al. Cortisol and proinflammatory cytokine profiles in type 1 (reversal) reactions of leprosy. Immunol Lett (2013) 156(1–2):159–67. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2013.10.008

124. Canetti CA, Leung BP, Culshaw S, McInnes IB, Cunha FQ, Liew FY. IL-18 enhances collagen-induced arthritis by recruiting neutrophils via TNF-alpha and leukotriene B4. J Immunol (2003) 171(2):1009–15. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1009

125. Choi IW, Sun K, Kim YS, Ko HM, Im SY, Kim JH, et al. TNF-alpha induces the late-phase airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation through cytosolic phospholipase A(2) activation. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2005) 116(3):537–43. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.034

126. Chen M, Lam BK, Luster AD, Zarini S, Murphy RC, Bair AM, et al. Joint tissues amplify inflammation and alter their invasive behavior via leukotriene B4 in experimental inflammatory arthritis. J Immunol (2010) 185(9):5503–11. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1001258

127. Sapkota BR, Macdonald M, Berrington WR, Misch EA, Ranjit C, Siddiqui MR, et al. Association of TNF, MBL, and VDR polymorphisms with leprosy phenotypes. Hum Immunol (2010) 71(10):992–8. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2010.07.001

128. Mazini PS, Alves HV, Reis PG, Lopes AP, Sell AM, Santos-Rosa M, et al. Gene association with leprosy: a review of published data. Front Immunol (2015) 6:658. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00658

129. Mattos KA, D’Avila H, Rodrigues LS, Oliveira VG, Sarno EN, Atella GC, et al. Lipid droplet formation in leprosy: toll-like receptor-regulated organelles involved in eicosanoid formation and Mycobacterium leprae pathogenesis. J Leukoc Biol (2010) 87(3):371–84. doi:10.1189/jlb.0609433

130. Mattos KA, Oliveira VG, D’Avila H, Rodrigues LS, Pinheiro RO, Sarno EN, et al. TLR6-driven lipid droplets in Mycobacterium leprae-infected Schwann cells: immunoinflammatory platforms associated with bacterial persistence. J Immunol (2011) 187(5):2548–58. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101344

131. Agrewala JN, Kumar B, Vohra H. Potential role of B7-1 and CD28 molecules in immunosuppression in leprosy. Clin Exp Immunol (1998) 111(1):56–63. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00463.x

132. Moura DF, Teles RM, Ribeiro-Carvalho MM, Teles RB, Santos IM, Ferreira H, et al. Long-term culture of multibacillary leprosy macrophages isolated from skin lesions: a new model to study Mycobacterium leprae-human cell interaction. Br J Dermatol (2007) 157(2):273–83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07992.x

133. Fournier T, Riches DW, Winston BW, Rose DM, Young SK, Noble PW, et al. Divergence in macrophage insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) synthesis induced by TNF-alpha and prostaglandin E2. J Immunol (1995) 155(4):2123–33.

134. Bichell DP, Rotwein P, McCarthy TL. Prostaglandin E2 rapidly stimulates insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression in primary rat osteoblast cultures: evidence for transcriptional control. Endocrinology (1993) 133(3):1020–8. doi:10.1210/endo.133.3.8396006

135. McCarthy TL, Ji C, Chen Y, Kim K, Centrella M. Time- and dose-related interactions between glucocorticoid and cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate on CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-dependent insulin-like growth factor I expression by osteoblasts. Endocrinology (2000) 141(1):127–37. doi:10.1210/endo.141.1.7237

136. Vendrame CM, Carvalho MD, Rios FJ, Manuli ER, Petitto-Assis F, Goto H. Effect of insulin-like growth factor-I on Leishmania amazonensis promastigote arginase activation and reciprocal inhibition of NOS2 pathway in macrophage in vitro. Scand J Immunol (2007) 66(2–3):287–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01950.x

137. Batista-Silva LR, Rodrigues LS, Vivarini Ade C, Costa Fda M, Mattos KA, Costa MR, et al. Mycobacterium leprae-induced insulin-like growth factor I attenuates antimicrobial mechanisms, promoting bacterial survival in macrophages. Sci Rep (2016) 6:27632. doi:10.1038/srep27632

138. Rodrigues LS, da Silva Maeda E, Moreira ME, Tempone AJ, Lobato LS, Ribeiro-Resende VT, et al. Mycobacterium leprae induces insulin-like growth factor and promotes survival of Schwann cells upon serum withdrawal. Cell Microbiol (2010) 12(1):42–54. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01377.x

139. Divangahi M, Desjardins D, Nunes-Alves C, Remold HG, Behar SM. Eicosanoid pathways regulate adaptive immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(8):751–8. doi:10.1038/ni.1904

140. Keane J, Remold HG, Kornfeld H. Virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains evade apoptosis of infected alveolar macrophages. J Immunol (2000) 164(4):2016–20. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2016