94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 22 November 2017

Sec. Inflammation

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01549

Scott M. Seki1,2,3

Scott M. Seki1,2,3 Alban Gaultier1*

Alban Gaultier1*

At the beginning of the twentieth century, discoveries in cancer research began to elucidate the idiosyncratic metabolic proclivities of tumor cells (1). Investigators postulated that revealing the distinct nutritional requirements of cells with unchecked growth potential would reveal targetable metabolic vulnerabilities by which their survival could be selectively curtailed. Soon thereafter, researchers in the field of immunology began drawing parallels between the metabolic characteristics of highly proliferative cancer cells and those of immune cells that respond to perceived threats to host physiology by invading tissues, clonally expanding, and generating vast amounts of pro-inflammatory effector molecules to provide the host with protection. Throughout the past decade, increasing effort has gone into elucidating the biosynthetic and bioenergetic requirements of immune cells during inflammatory responses. It is now well established that, like tumor cells, immune cells must undergo metabolic adaptations to fulfill their effector functions (2, 3). Unraveling the metabolic adaptations that license inflammatory immune responses may lead to the development of novel classes of therapeutics for pathologies with prominent inflammatory components (e.g., autoimmunity). However, the translational potential of discoveries made toward this end is currently limited by the ubiquitous nature of the “pathologic” process being targeted: metabolism. Recent works have started to unravel unexpected non-metabolic functions for metabolic enzymes in the context of inflammation, including signaling and gene regulation. One way information gained through the study of immunometabolism may be leveraged for therapeutic benefit is by exploiting these non-canonical features of metabolic machinery, modulating their contribution to the immune response without impacting their basal metabolic functions. The focus of this review is to discuss the metabolically independent functions of glycolytic enzymes and how these could impact T cells, agents of the immune system that are commonly considered as orchestrators of auto-inflammatory processes.

Upon activation, T cells increase biomass, proliferate, and produce inflammatory cytokines—processes that are bioenergetically and biosynthetically demanding, and likewise, necessitate a conversion from a relatively quiescent metabolism (2–5). One mechanism by which this is accomplished is through elevated glycolytic flux. As a result, many groups are pursuing the promise of anti-glycolytic therapy for inflammatory indications (6, 7). Conversely, there is also interest in interventions to restore T cell metabolism in diseases of pathologic immunosuppression (e.g., cancer) (8–10). Intriguingly, many glycolytic enzymes serve moonlighting functions in the cell that can impact the nature and quality of an inflammatory response. Such idiosyncrasies may represent exploitable opportunities by which immune responses may be therapeutically modulated. The goal of this review is to present non-metabolic functions of glycolysis enzymes and the ways in which these idiosyncrasies may be exploited to impact inflammatory responses, particularly those of T cells.

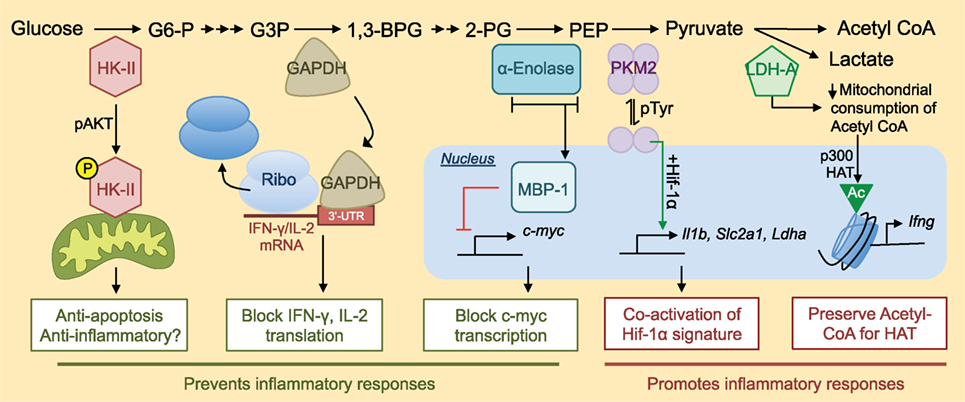

Hexokinase is the first enzyme involved in glycolysis, catalyzing the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) (Figure 1). Induction of HK-II, one of four isoforms of hexokinase, appears to be tightly linked to activation of inflammatory programs in immune cells (11, 12) and tumorigenic programs in cancer cells (10). Phosphorylated AKT stabilizes the localization of HK-II to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). At this location, mitoHK-II has increased access to mitochondrially derived ATP, which it can then use to phosphorylate glucose to G6P, thereby trapping glucose in the cell (13). MitoHK-II also plays an anti-apoptotic role, preventing the formation of the mitochondria permeability transition pore by Bcl-2 family proteins like Bax (14, 15). The mechanism behind this process involves PI3K-AKT-mediated phosphorylation of Thr473 in HK-II, a modification that prevents G6P-mediated dissociation of HK-II from the mitochondria (16). Thus, posttranslational modifications to HK-II both facilitate its activity as a glycolytic enzyme and promote its anti-apoptotic functions.

Figure 1. Non-metabolic functions of glycolytic enzymes and their roles in inflammation. Many pieces of glycolytic machinery have non-metabolic functions that can contribute to the inflammatory response. An abridged version of the glycolytic cascade is listed with enzymes depicted at their appropriate level in glycolysis along with their alternative non-metabolic functions. For a more complete view of the glycolytic cascade, please see Ref. (17). G6-P, glucose 6-phosphate; G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 2-PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Ribo, ribosome; Slc2a1, gene encoding glucose transporter 1 (Glut-1); HAT, histone acetyltransferase.

Upon activation, immune cells upregulate HK-II (17) as well as other HK family members (18). HK-targeted interventions block glycolysis, effector function, and survival of cells involved in driving inflammatory responses (6), and for myeloid cells, this is especially true in the context of gram-negative bacterial challenges (19). However, this may not be true of all inflammatory responses. N-acetylglucosamine, a peptidoglycan derivative from the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria, has recently been shown to bind HK-II and promote its dissociation from the OMM. This dissociation results in the accumulation of mitochondrial DNA in the cytosol and NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent production of mature IL-1β and IL-18 in macrophages (20). Thus, while dissociation of HK-II from the OMM might, on the one hand, abrogate the efficiency of flux through the glycolytic cascade and thus block inflammation, on the other hand, it may potentiate signals that promote secretion of major soluble transducers of inflammation depending on context. Inflammasome components (21, 22), hexokinase (6), and mitochondrial dynamics (23) are all known modulators of T cell functions; however, whether or not HK relocalization can induce inflammasome activity in T cells, and what consequences this may have, remains unclear.

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase is the enzyme that catalyzes conversion of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate in glycolysis (Figure 1). GAPDH is well known for its numerous non-metabolic functions. In many bacteria, GAPDH is a major component of the cell surface. Multiple mechanisms are involved in this localization of GAPDH, including active transport (24) and lysis-mediated release of GAPDH which then decorates the surface of neighboring bacterial cells (25). Cell surface GAPDH binds fibronectin, plasminogen, and other tissue components (24–26) and is an important facilitator of bacterial adherence to and invasion of host tissues. These findings translate to eukaryotic systems. In response to inflammatory cues, macrophages recruit GAPDH to the cell surface where it functions as a plasminogen receptor. In this paradigm, plasminogen bound to GAPDH digests extracellular matrix thereby facilitating macrophage migration (27). GAPDH can also localize to numerous other subcellular compartments (28). For example, oxidative stress, as occurs during neutrophil respiratory burst, drives S-nitrosylation of GAPDH (29), redistributing it from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and mitochondria where it is broadly implicated as a regulator of cell survival [reviewed in Ref. (28)]. GAPDH itself has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties, as systemic administration of GAPDH prior to LPS-induced sepsis reduces cytokine storm and mortality (30), though the mechanism of this immunomodulatory effect remains unknown.

Recent work in T cells implicates GAPDH as an energy sensor that regulates translation of inflammatory cytokine mRNA in response to the availability of glucose in the cell. When glucose concentrations are low, GAPDH binds to the AU-rich elements in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA, including those encoding interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and IL-2 (31, 32). Binding of GAPDH to these transcripts represses their translation, thus restricting cytokine production during glucose deprivation. 3′AU-rich elements are not unique features of IFN-γ and IL-2 mRNA, and it is likely that GAPDH can regulate translation beyond these two cytokines (33). The glycolytic reaction catalyzed by GAPDH requires nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), an essential indicator of cellular redox state, and intriguingly, Nagy and colleagues identified the NAD+ binding fold of GAPDH as its RNA-binding domain (34). This finding suggests any NAD+-dependent enzyme [in glycolysis, this is GAPDH and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)] may be endowed with RNA-binding capabilities. Glucose deprivation, however, increases levels of intracellular NAD+ which might be expected to compete with GAPDH for RNA binding (35). Thus, there are likely additional layers of regulation governing the role of GAPDH as a translational repressor that functions during glucose deprivation and or in response to fluctuations in NAD+. Context-specific nuances that influence how NAD+ affects the mRNA-binding functions of glycolytic machinery offer an intriguing line of inquiry into the interplay between metabolism and the many fundamental processes (36, 37) regulated by NAD+.

α-Enolase catalyzes the conversion of 2-phosphoglycerate to phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) in glycolysis (Figure 1). The gene that encodes α-enolase (Eno1) produces a single transcript with two translational start sites. Depending on the site of translation initiation, Eno1 can generate a full-length canonical α-enolase (48 kDa) enzyme that participates in glycolysis, or a truncated version of α-enolase (37 kDa), also known as Myc promoter-binding protein 1 (MBP-1) that represses the pro-proliferative transcription factor c-myc (38–41). Wang and colleagues identified c-myc as the master regulator of metabolic adaptation in T cells (17), demonstrating impaired growth and proliferation in c-myc deficient T cells treated with mitogenic stimuli. MBP-1 represses c-myc by binding to and inhibiting formation of the transcription initiation complex at the c-myc promoter (40, 41). Whereas α-enolase localizes to the cytoplasm, MBP-1 preferentially traffics to the nucleus where it serves these repressive functions (38). The signals that influence differential translation of α-enolase versus MBP-1 are unclear, though hypoxia may be one cue that favors translation of full-length α-enolase (42). The internal translation start site that generates MBP-1 off of Eno1 is not present in β or γ-enolase, potentially providing an added layer of specificity for future MBP-1 modulating interventions.

Intriguingly, it seems that the induction of MBP-1 functionally impacts T cell inflammatory responses in the context of autoimmunity. A recent study (43) revealed that an anti-inflammatory population of human CD4+ T cells, known as regulatory T cells (Tregs), expresses high levels of MBP-1. Moreover, MBP-1 in Tregs potentiates transcription of a specific spliced isoform of FoxP3 known to potently suppress inflammatory immune responses, particularly those mediated by the transcription factor RAR-related orphan receptor gamma T (RORγT). RORγT is a known driver of IL-17A (44) and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (45), pro-inflammatory cytokines strongly associated with auto-inflammatory diseases (46–48), and the therapeutic potential of its inhibition is under investigation for numerous inflammatory indications (49, 50). Interestingly, Tregs seem to elevate expression of both Eno1 gene products, suggesting that the suppressive effects of MBP-1 may dominate over metabolic contributions to inflammation facilitated by full-length α-enolase or elevated glycolysis (43, 51). Thus, inducing transcriptional activity at Eno1 may be sufficient to increase MBP-1 protein levels to immunosuppressive levels without blocking glycolysis. How the α-enolase/MBP-1 axis affects conventional T cell responses is unclear. Taken together, whereas Hk2 encodes a single protein that can play metabolic and non-metabolic roles in a cell, Eno1 encodes two gene products that differ drastically in their contributions to metabolism and inflammation (38, 39).

Pyruvate kinase is the ATP-generating enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of PEP to pyruvate during glycolysis (Figure 1). Four isoforms of the PK enzyme exist, with the M1 (PKM1) and M2 (PKM2) isoforms being most predominant in leukocytes of the adult animal (52). PKM2 is the major isoform expressed at the protein level by lymphocytes (52). Interestingly, many cancer cell lines also exclusively express PKM2 (53), and cancer researchers have likewise identified many pro-proliferative and non-canonical functions that are specifically attributed to this particular isozyme (54–63). PKM1 and PKM2 are alternatively spliced isoforms of the PK enzyme that differ by inclusion of a single exon (exon 9 for PKM1 versus exon 10 for PKM2), of which only 22 amino acid residues differ (64). The structures of PKM1 and PKM2 are extremely similar (65), but importantly, the minute difference in amino acid sequence allows PKM2 to uniquely contribute to proliferative responses in cancer cells and inflammatory responses of immune cells (66–69). Whereas PKM1 exists solely as a tetramer that functions as a glycolytic enzyme, PKM2 can exist as a tetramer with similar functions as PKM1 or as a dimer that loses activity as a glycolytic enzyme, but can perform numerous other non-glycolytic functions in the cell. From the perspective of glycolysis, this dynamic feature of PKM2 reduces its efficiency as a glycolytic enzyme and allows for the accumulation of upstream glycolytic intermediates, thereby promoting de novo amino acid and lipid biosynthesis—processes that are critical for the production of a daughter cell (70). From the perspective of inflammation, the PKM2 dimer can localize to the nucleus (58) where it is a well-known co-activator of Hif-1α gene signatures (54, 66, 67). In macrophages, this interaction is critical for the appropriate transcriptional activation of metabolic machinery, such as lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A) and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β (66). Similarly, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (55) and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (71) also require interaction with PKM2 for appropriate DNA binding. Thus, the PKM2 dimer seems to play a unique role as a direct modulator of proliferative and inflammatory programs. Relating to T cells, AhR, STAT3, and Hif-1α are all well-known regulators of Th17 cell differentiation perhaps implicating PKM2 as a regulator of this cell type.

Many groups in cancer research (56, 57, 60) and immunology (66–69, 72) are exploring the therapeutic potential of enforcing PKM2 tetramerization with pharmacologic compounds (62, 73). The major endogenous driver of PKM2 tetramerization is fructose 1,6 bisphosphate (FBP) (65), the product of the phosphofructokinase-catalyzed step in glycolysis. Phosphotyrosine residues generated by growth factor signaling (57, 59) can bind to PKM2 and promote release of FBP, and along with posttranslational modifications, such as PKM2 phosphorylation (74), oxidation (61), acetylation (58), and succinylation (75, 76), are endogenous drivers of tetramer dissociation. Synthetic activators of PKM2 tetramerization, originally characterized in cancer models as tumor-blocking agents (62), also potently block inflammation in numerous disease models (66, 67, 77). Thus, enforcing PKM2 tetramerization shows promise as a metabolic machinery-based paradigm for controlling inflammatory responses without overtly inhibiting metabolism itself.

Lactate dehydrogenase is a tetrameric enzyme variably composed of A and B subunits that, when combined, form a complex with the capability of converting pyruvate to lactate (Figure 1). This reaction is the defining step of aerobic glycolysis (78), the form of metabolism engaged by activated immune cells, which increase their regeneration of NAD+ consumed during glycolysis by producing lactate regardless of environmental oxygen content (2, 3). Peng and colleagues (79) recently showed that T cells almost exclusively express the A subunits of LDH, which they further upregulate upon activation, and expression of LDH-A is critical for the proper production of the inflammation-promoting cytokine IFN-γ. They found that genetic ablation of LDH-A in T cells heightened consumption of glycolysis-derived acetyl-CoA through the tricarboxylic cylic acid cycle and depleting intracellular stores of this metabolic byproduct of glucose catabolism. This acetyl-CoA depletion impaired activation-induced permissive histone acetylations that are required for opening of the Ifng locus during T cell activation. These findings and others (80–82) suggest that metabolic adaptations like aerobic glycolysis are important (1) as a means of generating sufficient ATP and metabolic intermediates to support anabolic processes and (2) as drivers of the epigenetic changes that are responsible for facilitating engagement of the inflammatory program [reviewed in Ref. (83)]. In addition to its ability to indirectly modulate the epigenetic landscape of the activated T cell, there is evidence to suggest that LDH-A may also be capable of directly influencing inflammatory responses. In a manner reminiscent of direct repression of IFN-γ and IL-2 mRNA translation by the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH (31, 32), LDH-A has been reported to bind to 3′AU-rich elements in GM-CSF mRNA (84). It remains unclear how the mRNA-binding properties of LDH-A affects downstream protein expression and, additionally, if this non-metabolic function is related to the level of flux through the glycolytic cascade or enzymatic activity. Inflammatory T cells are major producers of GM-CSF, a prominent driver of autoimmune responses (45–47, 85, 86), and a detailed study elucidating the metabolic requirements for GM-CSF production in vivo, including how it may relate to LDH-A, is warranted.

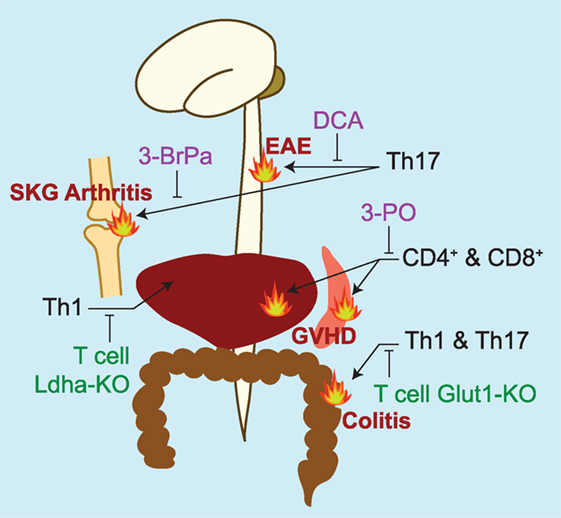

Seminal in vitro studies defined the metabolic peculiarities of inflammatory T cell subtypes (87–89) and paved the way for future works assessing the impact of glycolytic manipulations on T cell-driven inflammation in vivo (Figure 2) (10, 12, 90–94). Recent studies, however, question the strength of the relationship between glycolysis and inflammation in the in vivo setting. Peripheral blood T cells isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis show defects in glycolytic flux, rather than elevated glycolysis (95, 96). Likewise, impaired glycolysis is also detected in peripheral blood T cells isolated from multiple sclerosis patients and type 1 diabetics (43). One potential explanation for these findings may be that T cells at sites of pathology may maintain a distinct metabolism from those in circulation. Alternatively, the metabolic signatures of immune cells generated in vitro versus in vivo may be fundamentally different, and investigating the similarities and differences between these cells could reveal aspects of the metabolism–inflammation relationship that are currently being overlooked (97). The study of Treg metabolism provides a great example of the discrepancies between in vivo and in vitro-derived cells. Whereas Tregs (Tregs) generated by standard in vitro protocols maintain a metabolic profile that favors mitochondrial respiration over aerobic glycolysis, Tregs isolated ex vivo seem to be profoundly glycolytic (51, 98), and this metabolic signature is proposed to favor their transcriptional activity at Eno1 to produce α-enolase and MBP-1 (43). Indeed, the association between glycolytic flux and inflammation is likely not as clear in vivo as it is in vitro. Nevertheless, the non-metabolic functions of glycolytic machinery, including their relationship to inflammation, have been convincingly demonstrated in vivo and represent intriguing therapeutic opportunities for the future development of metabolically focused interventions for inflammatory disease. Toward this end, it will be important to determine the non-metabolic functions of glycolytic enzymes in other systems. For example, the mitochondrial localization of HK-II is important for cardiomyocyte function and interventions at this level of glycolysis might be anticipated to impact the heart (15, 16). In the kidney, podocytes were recently shown to express high levels of PKM2, and the non-metabolic functions of the enzyme in this context appear to play essential disease-potentiating roles in the context of diabetic nephropathy (77). Indeed, an important step toward realizing the therapeutic potential of targeting the non-metabolic functions of glycolytic enzymes during inflammation is to better understand these functions within and beyond the context of immunity. Finally, just as particular inflammatory processes are often associated with a unique cytokine profile (e.g., TNF-α and rheumatoid arthritis or IL-17A and psoriasis), the metabolic proclivities and peculiarities of cells driving inflammation may also differ based on disease-specific contexts. Further investigation into the nuances of immune cell metabolism in the in vivo setting and how this relates to their inflammatory functions are needed to better elucidate and potentially target the relationship between metabolism and inflammation during disease.

Figure 2. Summary of studies targeting glycolytic machinery in vivo to treat pathologies with prominent inflammatory T cell contributions. Pharmacologic inhibitors of glycolysis are listed in purple. DCA, dichloroacetate, an inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (12); 3-BrPa, 3-bromopyruvate, an inhibitor of hexokinase and GAPDH (93); 3-PO, 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one, an inhibitor of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3, PFK2) (91). Genetic models targeting glycolytic machinery in T cells are listed in green. LDH-A, lactate dehydrogenase A (79); Glut-1, glucose transporter 1 (90). In vivo models of inflammation studied are experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)—a murine model of multiple sclerosis, SKG arthritis [a model of rheumatoid arthritis that spontaneously develops in the SKG strain of mice (99)]; graft versus host disease (GVHD), and colitis.

The metabolic requirements that support immune-mediated inflammatory responses are well established in vitro and increasingly so in vivo. Elevated consumption of glucose plays an important role in inflammatory responses of T cells, where glycolytic processes can serve to generate ATP, produce metabolic intermediates that are important for anabolic processes and even alter the epigenetic landscape of the activated cell. To achieve this, activated immune cells must upregulate expression of metabolic machinery, many of which serve non-metabolic functions in the cell that are directly linked to modulating the inflammatory response. Research in cancer cells has led to the identification of many non-metabolic functions of glycolytic enzymes (100, 101), and only recently are these functions beginning to be assessed in the context of inflammation. Just as research into the metabolic activity of cancer cells provided the foundations for immunometabolic studies to identify the unique bioenergetic requirements of immune cell subsets, so too may the non-metabolic functions of glycolytic enzymes discovered in cancer cells instruct an alternative way of looking at the relationship between metabolism and inflammation. Importantly, this alternative approach may generate interventions that are more readily translatable to the clinical setting than therapies that overtly impinge on enzymatic activity of metabolic machinery.

In addition to those listed here, other isoforms of glycolytic machinery with known non-metabolic properties in cancer cells, such as phosphofructokinase-1 (102), seem to be selectively induced in immune cells in response to distinct stimuli. Determining how these contribute to the T cell inflammatory program is of interest. Conversely, activation-induced proteins that are not classically associated with metabolism, such as CD69 (103), may also play metabolic roles that are important for inflammatory immune responses. In addition, byproducts of metabolic processes, such as PEP (10), lactate (104, 105), succinate (19, 66, 106–108), citrate (109), 2-hydroxyglutarate (110), α-ketoglutarate (111), and others (102), are gaining increasing recognition for the non-metabolic roles they play as direct modulators of inflammation. Further exploration into the unique ways in which metabolic processes contribute to immune responses may reveal exploitable opportunities to destabilize the relationship between metabolism and inflammation for therapeutic benefit.

Both the authors have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors are supported by NIH grants R01 NS083542 (AG), T32 GM008328 (SS), T32 GM007267 (SS), and F31 NS103327 (SS).

1. Warburg O. The metabolism of carcinoma cells. Cancer Res (1925) 9:148–63. doi:10.1158/jcr.1925.148

2. Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med (2015) 212:1345–60. doi:10.1084/jem.20151159

3. Buck MD, Sowell RT, Kaech SM, Pearce EL. Metabolic instruction of immunity. Cell (2017) 169:570–86. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.004

4. MacIver NJ, Michalek RD, Rathmell JC. Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol (2013) 31:259–83. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095956

5. Pearce EL, Poffenberger MC, Chang C-H, Jones RG. Fueling immunity: insights into metabolism and lymphocyte function. Science (2013) 342:1242454. doi:10.1126/science.1242454

6. Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, Vogel P, Neale G, Green DR, et al. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med (2011) 208:1367–76. doi:10.1084/jem.20110278

7. Lee CF, Lo YC, Cheng CH, Furtmüller GJ, Oh B, Andrade-Oliveira V, et al. Preventing allograft rejection by targeting immune metabolism. Cell Rep (2015) 13:760–70. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.036

8. Gross G, Eshhar Z. Therapeutic potential of T cell chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) in cancer treatment: counteracting off-tumor toxicities for safe CAR T cell therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol (2016) 56:59–83. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124844

9. Scharping NE, Menk AV, Moreci RS, Whetstone RD, Dadey RE, Watkins SC, et al. The tumor microenvironment represses T cell mitochondrial biogenesis to drive intratumoral T cell metabolic insufficiency and dysfunction. Immunity (2016) 45:374–88. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.009

10. Ho P, Bihuniak JD, Macintyre AN, Staron M, Liu X, Amezquita R, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate is a metabolic checkpoint of article phosphoenolpyruvate is a metabolic checkpoint of anti-tumor T cell responses. Cell (2015) 162:1217–28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012

11. Marjanovic S, Eriksson I, Nelson BD. Expression of a new set of glycolytic isozymes in activated human peripheral lymphocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta (1990) 1087:1–6. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(90)90113-G

12. Gerriets VA, Kishton RJ, Nichols AG, Macintyre AN, Inoue M, Ilkayeva O, et al. Metabolic programming and PDHK1 control CD4+ T cell subsets and inflammation. J Clin Invest (2015) 125:194–207. doi:10.1172/JCI76012

13. Roberts DJ, Miyamoto S. Hexokinase II integrates energy metabolism and cellular protection: Akting on mitochondria and TORCing to autophagy. Cell Death Differ (2014) 22:248–57. doi:10.1038/cdd.2014.173

14. Pastorino JG, Shulga N, Hoek JB. Mitochondrial binding of hexokinase II inhibits Bax-induced cytochrome c release and apoptosis *. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:7610–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109950200

15. Miyamoto S, Murphy AN, Brown JH. Akt mediates mitochondrial protection in cardiomyocytes through phosphorylation of mitochondrial hexokinase-II. Cell Death Differ (2008) 15:521–9. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4402285

16. Roberts DJ, Tan-sah VP, Smith JM, Miyamoto S. Akt phosphorylates HK-II at Thr-473 and increases mitochondrial HK-II association to protect cardiomyocytes *. J Biol Chem (2013) 288:23798–806. doi:10.1074/jbc.A113.482026

17. Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, Milasta S, Carter R, Finkelstein D, et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity (2011) 35:871–82. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.021

18. Moon JS, Hisata S, Park MA, DeNicola GM, Ryter SW, Nakahira K, et al. MTORC1-induced HK1-dependent glycolysis regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Rep (2015) 12:102–15. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.046

19. Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature (2013) 496:238–42. doi:10.1038/nature11986

20. Wolf AJ, Reyes CN, Liang W, Becker C, Shimada K, Wheeler ML, et al. Hexokinase is an innate immune receptor for the detection of bacterial peptidoglycan. Cell (2016) 166:624–36. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.076

21. Bruchard M, Rebé C, Derangère V, Togbé D, Ryffel B, Boidot R, et al. The receptor NLRP3 is a transcriptional regulator of T H 2 differentiation. Nat Immunol (2015) 16(8):859–70. doi:10.1038/ni.3202

22. Lukens JR, Gurung P, Shaw PJ, Barr MJ, Zaki MH, Brown SA, et al. The NLRP12 sensor negatively regulates autoinflammatory disease by modulating interleukin-4 production in T cells. Immunity (2015) 42:654–64. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.006

23. Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Klein Geltink RI, Curtis JD, Chang CH, Sanin DE, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics controls T cell fate through metabolic programming. Cell (2016) 166:63–76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.035

24. Jin H, Agarwal S, Agarwal S, Pancholi V. Surface export of GAPDH/SDH, a glycolytic enzyme, is essential for Streptococcus pyogenes virulence. MBio (2011) 2:9–11. doi:10.1128/mBio.00068-11

25. Terrasse R, Amoroso A, Vernet T, Di Guilmi AM. Streptococcus pneumoniae GAPDH Is released by cell lysis and interacts with peptidoglycan. PLoS One (2015) 10(4):e0125377. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125377

26. Pancholi V, Fischetti VA. A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. J Exp Med (1992) 176:13–6. doi:10.1084/jem.176.2.415

27. Chauhan AS, Kumar M, Chaudhary S, Patidar A, Dhiman A, Sheokand N, et al. Moonlighting glycolytic protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH): an evolutionarily conserved plasminogen receptor on mammalian cells. FASEB J (2017) 31:2638–48. doi:10.1096/fj.201600982R

28. Tristan C, Shahani N, Sedlak TW, Sawa A. The diverse functions of GAPDH: views from different subcellular compartments. Cell Signal (2011) 23:317–23. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.003

29. Hara MR, Agrawal N, Kim SF, Cascio MB, Fujimuro M, Ozeki Y, et al. S-nitrosylated GAPDH initiates apoptotic cell death by nuclear translocation following Siah1 binding. Nat Cell Biol (2005) 7(7):665–74. doi:10.1038/ncb1268

30. Takaoka Y, Goto S, Nakano T, Tseng HP, Yang SM, Kawamoto S, et al. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) prevents lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced, sepsis-related severe acute lung injury in mice. Sci Rep (2014) 4:5204. doi:10.1038/srep05204

31. Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB Jr, Faubert B, Villarino AV, O’Sullivan D, et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell (2013) 153:1239–51. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016

32. Blagih J, Coulombe F, Vincent EE, Dupuy F, Galicia-Vázquez G, Yurchenko E, et al. The energy sensor AMPK regulates T cell metabolic adaptation and effector responses in vivo. Immunity (2015) 42:41–54. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.030

33. Millet P, Vachharajani V, McPhail L, Yoza B, McCall CE. GAPDH binding to TNF-alpha mRNA contributes to posttranscriptional repression in monocytes: a novel mechanism of communication between inflammation and metabolism. J Immunol (2016) 196:2541–51. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1501345

34. Nagy E, Henics T, Eckert M, Miseta A, Lightowlers RN, Kellermayer M. Identification of the NAD(+)-binding fold of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as a novel RNA-binding domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2000) 275:253–60. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3246

35. Schwartz JP, Johnson GS. Metabolic effects of glucose deprivation and of various sugars in normal and transformed fibroblast cell lines. Arch Biochem Biophys (1976) 173:237–45. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(76)90255-1

36. Sasaki Y, Nakagawa T, Mao X, Diantonio A, Milbrandt J. NMNAT1 inhibits axon degeneration via blockade of SARM1-mediated NAD+ depletion. Elife (2016) 5:1–15. doi:10.7554/eLife.19749

37. Katsyuba E, Auwerx J. Modulating NAD+ metabolism, from bench to bedside. EMBO J (2017) 36:2670–83. doi:10.15252/embj.201797135

38. Feo S, Arcuri D, Piddini E, Passantino R, Giallongo A. ENO1 gene product binds to the c-myc promoter and acts as a transcriptional repressor: relationship with Myc promoter-binding protein 1 (MBP-1). FEBS Lett (2000) 473:47–52. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01494-0

39. Subramanian A, Miller DM. Structural analysis of alpha-enolase. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:5958–65. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.8.5958

40. Ray R, Miller DM. Cloning and characterization of a human c-myc promoter-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol (1991) 11:2154–61. doi:10.1128/MCB.11.4.2154

41. Chaudhary D, Miller DM. The c-myc promoter binding protein (MBP-1) and TBP bind simultaneously in the minor groove of the c-myc P2 promoter. Biochemistry (1995) 34:3438–45. doi:10.1021/bi00010a036

42. Sedoris KC, Thomas SD, Miller DM. Hypoxia induces differential translation of enolase/MBP-1. BMC Cancer (2010) 10:157. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-157

43. De Rosa V, Galgani M, Porcellini A, Colamatteo A, Santopaolo M, Zuchegna C, et al. Glycolysis controls the induction of human regulatory T cells by modulating the expression of FOXP3 exon 2 splicing variants. Nat Immunol (2015) 16(11):1174–84. doi:10.1038/ni.3269

44. Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature (2008) 453:236–40. doi:10.1038/nature06878

45. Codarri L, Gyülvészi G, Tosevski V, Hesske L, Fontana A, Magnenat L, et al. RORγt drives production of the cytokine GM-CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:560–7. doi:10.1038/ni.2027

46. Pierson ER, Goverman JM. GM-CSF is not essential for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis but promotes brain-targeted disease. J Clin Investig Insight (2017) 2:1–10. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.92362

47. Croxford AL, Lanzinger M, Hartmann FJ, Schreiner B, Mair F, Pelczar P, et al. The cytokine GM-CSF drives the inflammatory signature of CCR2+ monocytes and licenses autoimmunity. Immunity (2015) 43:502–14. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.010

48. Kebir H, Kreymborg K, Ifergan I, Dodelet-Devillers A, Cayrol R, Bernard M, et al. Human TH17 lymphocytes promote blood-brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nat Med (2007) 13:1173–5. doi:10.1038/nm1651

49. Huh JR, Littman DR. Small molecule inhibitors of ROR γ t: targeting Th17 cells and other applications. Eur J Immunol (2012) 42:2232–7. doi:10.1002/eji.201242740

50. Xiao S, Yosef N, Yang J, Wang Y, Zhou L, Zhu C, et al. Small-molecule ROR g t antagonists inhibit T helper 17 cell transcriptional network by divergent mechanisms. Immunity (2014) 40:477–89. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.004

51. Procaccini C, Carbone F, Di Silvestre D, Brambilla F, De Rosa V, Galgani M, et al. The proteomic landscape of human ex vivo regulatory and conventional T cells reveals specific metabolic requirements. Immunity (2016) 44:406–21. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.028

52. Dayton TL, Gocheva V, Miller KM, Israelsen WJ, Bhutkar A, Clish CB, et al. Germline loss of PKM2 promotes metabolic distress and hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev (2016) 30:1020–33. doi:10.1101/gad.278549.116

53. Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, et al. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature (2008) 452:230–3. doi:10.1038/nature06734

54. Luo W, Hu H, Chang R, Zhong J, Knabel M, O’Meally R, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a PHD3-stimulated coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell (2011) 145:732–44. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.054

55. Gao X, Wang H, Yang JJ, Liu X, Liu ZR. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates gene transcription by acting as a protein kinase. Mol Cell (2012) 45:598–609. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.001

56. Yang W, Xia Y, Hawke D, Li X, Liang J, Xing D, et al. PKM2 phosphorylates histone H3 and promotes gene transcription and tumorigenesis. Cell (2012) 150:685–96. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.018

57. Yang W, Xia Y, Ji H, Zheng Y, Liang J, Huang W, et al. Nuclear PKM2 regulates β-catenin transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature (2011) 480:118–22. doi:10.1038/nature10598

58. Lv L, Xu YP, Zhao D, Li FL, Wang W, Sasaki N, et al. Mitogenic and oncogenic stimulation of K433 acetylation promotes PKM2 protein kinase activity and nuclear localization. Mol Cell (2013) 52:340–52. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.004

59. Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Wu N, Asara JM, Cantley LC. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a phosphotyrosine-binding protein. Nature (2008) 452:181–6. doi:10.1038/nature06667

60. Lunt SY, Muralidhar V, Hosios AM, Israelsen WJ, Gui DY, Newhouse L, et al. Pyruvate kinase isoform expression alters nucleotide synthesis to impact cell proliferation. Mol Cell (2015) 57:95–107. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.027

61. Anastasiou D, Poulogiannis G, Asara JM, Boxer MB, Jiang JK, Shen M, et al. Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive Oxygen Species contributes to cellular antioxidant responses. Science (2011) 334:1278–83. doi:10.1126/science.1211485

62. Anastasiou D, Yu Y, Israelsen WJ, Jiang JK, Boxer MB, Hong BS, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 activators promote tetramer formation and suppress tumorigenesis. Nat Chem Biol (2012) 8:839–47. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1060

63. Israelsen WJ, Dayton TL, Davidson SM, Fiske BP, Hosios AM, Bellinger G, et al. PKM2 isoform-specific deletion reveals a differential requirement for pyruvate kinase in tumor cells. Cell (2013) 155:397–409. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.025

64. Noguchi T, Inoue H, Tanaka T. The MI- and M2-type isozymes of rat pyruvate kinase are produced from the same gene by alternative RNA splicing. J Biol Chem (1986) 261:13807–12.

65. Dombrauckas JD, Santarsiero BD, Mesecar AD. Structural basis for tumor pyruvate kinase M2 allosteric regulation and catalysis. Biochemistry (2005) 44:9417–29. doi:10.1021/bi0474923

66. Palsson-McDermott EM, Curtis AM, Goel G, Lauterbach MA, Sheedy FJ, Gleeson LE, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates Hif-1α activity and IL-1β induction and is a critical determinant of the Warburg effect in LPS-activated macrophages. Cell Metab (2015) 21:65–80. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.017

67. Shirai T, Nazarewicz RR, Wallis BB, Yanes RE, Watanabe R, Hilhorst M, et al. The glycolytic enzyme PKM2 bridges metabolic and inflammatory dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J Exp Med (2016) 213:337–54. doi:10.1084/jem.20150900

68. Yang L, Xie M, Yang M, Yu Y, Zhu S, Hou W, et al. PKM2 regulates the Warburg effect and promotes HMGB1 release in sepsis. Nat Commun (2014) 5:1–9. doi:10.1038/ncomms5436

69. Xie M, Yu Y, Kang R, Zhu S, Yang L, Zeng L, et al. PKM2-dependent glycolysis promotes NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun (2016) 7:1–13. doi:10.1038/ncomms13280

70. Chaneton B, Hillmann P, Zheng L, Martin ACL, Maddocks ODK, Chokkathukalam A, et al. Serine is a natural ligand and allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase M2. Nature (2012) 491:458–62. doi:10.1038/nature11540

71. Matsuda S, Adachi J, Ihara M, Tanuma N, Shima H, Kakizuka A, et al. Nuclear pyruvate kinase M2 complex serves as a transcriptional coactivator of arylhydrocarbon receptor. Nucleic Acids Res (2016) 44:636–47. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv967

72. Alves-Filho JC, Pålsson-McDermott EM. Pyruvate kinase M2: a potential target for regulating inflammation. Front Immunol (2016) 7:145. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00145

73. Boxer MB, Jiang JK, Vander Heiden MG, Shen M, Skoumbourdis AP, Southall N, et al. Evaluation of substituted N,N′-diarylsulfonamides as activators of the tumor cell specific M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase. J Med Chem (2010) 53:1048–55. doi:10.1021/jm901577g

74. Yang W, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Ji H, Chen X, Guo F, et al. ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat Cell Biol (2012) 14:1295–304. doi:10.1038/ncb2629

75. Bhardwaj A, Das S. SIRT6 deacetylates PKM2 to suppress its nuclear localization and oncogenic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2016) 113:E538–47. doi:10.1073/pnas.1520045113

76. Wang F, Wang K, Xu W, Zhao S, Ye D, Wang Y, et al. SIRT5 desuccinylates and activates pyruvate kinase M2 to block macrophage IL-1 b production and to prevent DSS-induced colitis in mice. Cell Rep (2017) 19:2331–44. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.065

77. Qi W, Keenan HA, Li Q, Ishikado A, Kannt A, Sadowski T, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 activation may protect against the progression of diabetic glomerular pathology and mitochondrial dysfunction. Nat Med (2017) 23(6):753–62. doi:10.1038/nm.4328

78. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science (2009) 324:1029–33. doi:10.1126/science.1160809

79. Peng M, Yin N, Chhangawala S, Xu K, Leslie CS, Li MO. Aerobic glycolysis promotes T helper 1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism. Science (2016) 354:481–4. doi:10.1126/science.aaf6284

80. Arts RJ, Novakovic B, Ter Horst R, Carvalho A, Bekkering S, Lachmandas E, et al. Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell Metab (2016) 24:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.008

81. Donohoe DR, Bultman SJ. Metaboloepigenetics: interrelationships between energy metabolism and epigenetic control of gene expression. J Cell Physiol (2012) 227:3169–77. doi:10.1002/jcp.24054

82. Cheng S-C, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1alpha-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science (2014) 345:1250684–1250684. doi:10.1126/science.1250684

83. Phan AT, Goldrath AW, Glass CK. Metabolic and epigenetic coordination of T cell and macrophage immunity. Immunity (2017) 46:714–29. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.016

84. Pioli PA, Hamilton BJ, Connolly JE, Brewer G, Rigby WFC. Lactate dehydrogenase is an AU-rich element-binding protein that directly interacts with AUF1 *. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:35738–45. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204002200

85. Ponomarev ED, Shriver LP, Maresz K, Pedras-Vasconcelos J, Verthelyi D, Dittel BN. GM-CSF production by autoreactive T cells is required for the activation of microglial cells and the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (2007) 178:39–48. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.39

86. Spath S, Komuczki J, Hermann M, Pelczar P, Mair F, Schreiner B, et al. Dysregulation of the cytokine GM-CSF induces spontaneous phagocyte invasion and immunopathology in the central nervous system. Immunity (2017) 46:245–60. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.007

87. Jacobs SR, Herman CE, Maciver NJ, Wofford JA, Wieman HL, Hammen JJ, et al. Glucose uptake is limiting in T cell activation and requires CD28-mediated Akt-dependent and independent pathways. J Immunol (2008) 180:4476–86. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4476

88. Michalek RD, Gerriets VA, Jacobs SR, Macintyre AN, MacIver NJ, Mason EF, et al. Cutting edge: distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J Immunol (2011) 186:3299–303. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003613

89. Frauwirth KA, Riley JL, Harris MH, Parry RV, Rathmell JC, Plas DR, et al. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity (2002) 16:769–77. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00323-0

90. Macintyre AN, Gerriets VA, Nichols AG, Michalek RD, Rudolph MC, Deoliveira D, et al. The glucose transporter Glut1 is selectively essential for CD4 T cell activation and effector function. Cell Metab (2014) 20:61–72. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.004

91. Nguyen HD, Chatterjee S, Haarberg KM, Wu Y, Bastian D, Heinrichs J, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of alloantigen-activated T cells after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Invest (2016) 126:1–16. doi:10.1172/JCI82587

92. Seki SM, Stevenson M, Rosen AM, Arandjelovic S, Gemta L, Bullock TNJ, et al. Lineage-specific metabolic properties and vulnerabilities of T cells in the demyelinating central nervous system. J Immunol (2017) 198(12):4607–17. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1600825

93. Okano T, Saegusa J, Nishimura K, Takahashi S, Sendo S, Ueda Y, et al. 3-Bromopyruvate ameliorate autoimmune arthritis by modulating Th17/Treg cell differentiation and suppressing dendritic cell activation. Sci Rep (2017) 7:42412. doi:10.1038/srep42412

94. Yin Y, Choi SC, Xu Z, Perry DJ, Seay H, Croker BP, et al. Normalization of CD4+ T cell metabolism reverses lupus. Sci Transl Med (2015) 7:274ra18. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0835

95. Yang Z, Fujii H, Mohan SV, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Phosphofructokinase deficiency impairs ATP generation, autophagy, and redox balance in rheumatoid arthritis T cells. J Exp Med (2013) 210:2119–34. doi:10.1084/jem.20130252

96. Yang Z, Shen Y, Oishi H, Matteson EL, Tian L, Goronzy JJ, et al. Restoring oxidant signaling suppresses proarthritogenic T cell effector functions in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med (2016) 8:ra38–331. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7151

97. Franchi L, Monteleone I, Hao LY, Spahr MA, Zhao W, Liu X, et al. Inhibiting oxidative phosphorylation in vivo restrains Th17 effector responses and ameliorates murine colitis. J Immunol (2017) 198:2735–46. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1600810

98. Melis D, Carbone F, Minopoli G, La Rocca C, Perna F, De Rosa V, et al. Cutting edge: increased autoimmunity risk in glycogen storage disease type 1b is associated with a reduced engagement of glycolysis in T cells and an impaired regulatory T cell function. J Immunol (2017) 198:3803–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1601946

99. Hata H, Sakaguchi N, Yoshitomi H, Iwakura Y, Sekikawa K, Azuma Y, et al. Distinct contribution of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-10 to T cell – mediated spontaneous autoimmune arthritis in mice. J Clin Invest (2004) 114:582–8. doi:10.1172/JCI200421795

100. Lincet H, Icard P. How do glycolytic enzymes favour cancer cell proliferation by nonmetabolic functions? Oncogene (2014) 34:3751–9. doi:10.1038/onc.2014.320

101. Yu X, Li S. Non-metabolic functions of glycolytic enzymes in tumorigenesis. Oncogene (2017) 6:2629–36. doi:10.1038/onc.2016.410

102. Araujo L, Khim P, Mkhikian H, Mortales C, Demetriou M. Glycolysis and glutaminolysis cooperatively control T cell function by limiting metabolite supply to N-glycosylation. Elife (2017) 6:e21330. doi:10.7554/eLife.21330

103. Cibrian D, Saiz ML, de la Fuente H, Sánchez-Díaz R, Moreno-Gonzalo O, Jorge I, et al. CD69 controls the uptake of L-tryptophan through LAT1-CD98 and AhR-dependent secretion of IL-22 in psoriasis. Nat Immunol (2016) 17:985–96. doi:10.1038/ni.3504

104. Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T, Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature (2014) 513:559–63. doi:10.1038/nature13490

105. Haas R, Smith J, Rocher-Ros V, Nadkarni S, Montero-Melendez T, D’Acquisto F, et al. Lactate regulates metabolic and pro-inflammatory circuits in control of T cell migration and effector functions. PLoS Biol (2015) 13(7):e1002202. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002202

106. Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, et al. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell (2005) 7:77–85. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.022

107. Rubic T, Lametschwandtner G, Jost S, Hinteregger S, Kund J, Carballido-Perrig N, et al. Triggering the succinate receptor GPR91 on dendritic cells enhances immunity. Nat Immunol (2008) 9:1261–9. doi:10.1038/ni.1657

108. Littlewood-Evans A, Sarret S, Apfel V, Loesle P, Dawson J, Zhang J, et al. GPR91 senses extracellular succinate released from inflammatory macrophages and exacerbates rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med (2016) 213(9):1655–62. doi:10.1084/jem.20160061

109. Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A, Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E, et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity (2015) 42:419–30. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005

110. Xu T, Stewart KM, Wang X, Liu K, Xie M, Kyu Ryu J, et al. Metabolic control of TH17 and induced Treg cell balance by an epigenetic mechanism. Nature (2017) 548:228–33. doi:10.1038/nature23475

Keywords: immunometabolism, inflammation, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, hexokinase, pyruvate kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, glycolysis

Citation: Seki SM and Gaultier A (2017) Exploring Non-Metabolic Functions of Glycolytic Enzymes in Immunity. Front. Immunol. 8:1549. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01549

Received: 22 September 2017; Accepted: 30 October 2017;

Published: 22 November 2017

Edited by:

Claudio Mauro, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, United KingdomReviewed by:

Martin V. Kolev, King’s College London, United KingdomCopyright: © 2017 Seki and Gaultier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alban Gaultier, YWc3aEB2aXJnaW5pYS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.