- 1Department of Animal Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction, College of Animal Science, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Agro-Animal Genomics and Molecular Breeding and Key Lab of Chicken Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction, Ministry of Agriculture, Guangzhou, China

Avian leukosis virus (ALV) is an avian oncogenic retrovirus causing enormous economic losses in the global poultry industry. Although ALV-related research has lasted for more than a century, there are no vaccines to protect chickens from ALV infection. The interaction between chickens and ALV remains not fully understood especially with regard to the host immunity. The current review provides an overview of our current knowledge of innate and adaptive immunity induced by ALV infection. More importantly, we have pointed out the unknown area involved in ALV-related studies, which is worthy of our serious exploring in future.

Introduction

Avian leukosis virus (ALV) is a notorious retrovirus causing neoplastic disease, immunosuppression, and other production problems. In chickens, the ALV are divided into six subgroups, including A, B, C, D, E, and J, based on their viral envelope glycoproteins responsible for viral interference patterns, virus neutralization, and host range (1). It is glorious that ALV-related studies provided Nobel laureates in 1966, 1975, and 1989 (1). Nowadays, ALV was almost eradicated in the western world (2, 3), but in China ALVs still persist in many bird species (4–8). Moreover, because Chinese poultry industry is less organized, especially among the local breeds of chickens, the ALV will exist for a long time and related studies would keep on in China.

Historically, the primary aims of ALV studies were concerned with the virus itself. This included elucidating mechanisms of tumorigenesis, viral transmission, virus isolation, viral replication, pathogenesis, and molecular biology. However, studies concerning the innate and adaptive immune responses to ALV have been neglected. Some reported studies are just limited on immunologic tolerance and immunosuppression induced by ALV (9, 10).

The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of progress in immunity against ALV, broaden the scope in new areas that are under active investigation.

Immunity Against ALV

Innate Immunity

The innate immune response provides the first line of defense against invading viruses and plays a key role in the subsequent activation of antiviral responses. During viral infection, virus pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are recognized by pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) that include toll-like receptors (TLRs) (11), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), NOD-like receptors (12), interferon-γ-inducible protein 16 (IFI16), and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) (13).

Virus recognition activates signaling pathways that lead to interferon (IFN) production as well as the activation of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (12). These immune factors recruit and activate innate immune cells including macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and natural killer (NK) cells that can control virus spread and activate and modulate the adaptive immune response (14). Moreover, hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) are induced through the JAK-STAT pathway and interact directly with viruses (15). Here, we will comprehensively discuss the interactions between ALV and host innate immunity regarding to the PRRs recognition, cytokine production, ISGs expression, and innate immune cells activation.

ALV Sensing

As single-stranded RNA retrovirus, ALV, like HIV, should theoretically be recognized by PRRs such as TLRs, RLRs, IFI16, and cGAS (13, 16–18). However, which specific innate sensors response to ALV is still elusive.

In DCs, TLR (1–4) expression changed significantly after ALV-J infection (19). However, the inclusion of lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-4 (IL-4) as pretreatments in these studies hampered the determination of which TLR was responsible (19). On the other hand, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) was found to have differential expression in ALV-J infected chickens identified through the use of transcriptome analysis with hybridization arrays and RNA-Seq (20, 21). In our laboratory, we demonstrated that ALV-J infection significantly increased TLR7 expression in chicks followed by MDA5 when the infection progressed to tumorigenesis (22). As a model, HIV-1 recognition by TLR7 requires only attachment and endocytosis, independent of retroviral replication (23). TLR-7 expression increased in ALV-J infected chicks at 1-day post-hatch and suggested that ALV-J was recognized by chicken TLR7 during the initial infection. RIG-I is a cytoplasmic sensor for HIV genomic RNA (23). Chickens lack RIG-I but MDA5 can compensate in immune activation (24). Our results showed that MDA5 expression was induced in the tumorigenesis phase, and we speculated that MDA5 was the primary sensing PRR during later infection stages (22).

In future, it is necessary to further verify that TLR7 and MDA5 are specific sensors of ALV via more experiments. Besides, other PRRs involved in ALV infection need be explored and identified.

Cytokine Production

The chicken spleen plays a dominant role in the generation of immune responses due to the absence of well-developed lymph nodes (25). This organ also functions in innate immune responses to ALV-J infection (26). In 1-day-old ALV-J-infected chicks, we could not detect any significant expression of IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β, or IFN-β in spleens from 1-day postinfection (dpi) to 7 dpi (22). In a similar study with ALV-J and 1-day-old chicks, IL-6, IL-18, IFN-α, and IFN-γ did not significantly change from 1 to 7 dpi, but they were significantly increased in spleens 9–12 dpi. The cytokine levels then sharply declined at 15 dpi when the ALV-J load reached its peak (26). Apparently, ALV-J does not induce an obvious antiviral innate immune response in 1-week-old chicks, and this helps to explain why ALV transmission primarily occurs at hatching or in the first week of life (27).

In the late stages of ALV-J infection, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, and IFN-β protein levels were significantly increased in the clinical infected chickens (22). In infected specific-pathogen-free chickens, IL-2 and IL-10 mRNA levels were significantly increased (28). IL-10 is a most important anti-inflammatory cytokine with immunosuppressive effects (29). High level of IL-10 (29) or large amounts of ALV-J might cause immunosuppression in chickens (26). In addition, these results suggest that IFN and interleukin play a role in the interaction of host innate immune system with ALV-J infection. We had previously determined that DF-1 (chicken embryo fibroblast) cells pretreated with recombinant chicken IFN-α were able to inhibit ALV-A/B/J replication (28). This study confirmed the importance of IFN in innate immunity against ALVs in vitro.

There have been few studies identifying specific inflammatory pathways in ALV-chicken interactions. However, a caspase-1-mediated inflammatory response could be triggered by ALV-J infection in chick livers (30). Caspase-1 expression combined with adaptor NLRP3 enabled IL-1β and IL-18 increases at 5 or 7 dpi (30). NLRP3 is an important initiator protein of the inflammasome, a multicomponent complex that activates caspase-1 and results in IL-1β and IL-18 secretion (31). However, this is the extent of this type of data but indicates that further research would yield fruitful results.

IFN-Stimulated Gene Induction

Many viruses trigger the IFN system that leads to the transcription of hundreds of ISGs. These genes exert antiviral effector functions, many of which are still not fully understood (15). In chickens, ISGs are not generally well described with the exception of the chicken ZAP and viperin genes (32, 33).

Avian leukosis virus-A/B/J infections increase the promoter activity of chicken interferon regulatory factors 3 (IRF3) [more similar to IRF7 (34)] (28). However, there are still no published reports on the activation of transcription factors such as IRF3, NF-κB, and those in the JAK-STAT pathway. Similarly, the identity of ISGs that directly act against ALV has only recently been reported.

In vivo studies demonstrated that ISG12-1, ISG12-2, OASL, and Mx increased in the chicken bursa of Fabricius at the 18th day of embryonation, and in 10- and 30-day-old with ALV-J infection (20). However, during the late stages of ALV-J infection or in the presence of a tumor, ISG12-1, ISG12-2, Mx, ZAP, IRF1, and STAT1 were significantly decreased or remained unchanged in chicken spleens (21, 22). This suggests that ALV may escape innate immunity result by decreasing some ISGs expression of during late infection stages (21, 22).

During ALV-J infection, miR-23b targeted IRF1 and down-regulated IFN-β expression, further promoting ALV-J replication (21). Interestingly, chicken biliary exosomes were found to contain ZAP and these inhibited ALV-J replication in vitro (35). Chicken ZAP is expressed in response to H5N1 and IBDV infections (32), but whether chicken ZAP is the key factor that inhibited ALV-J replication requires further study. It is important to identify and verify additional chicken ISGs to broaden our understanding of innate immune responses to develop protective strategies against ALV infections in chickens.

Innate Immune Cells

Virus sensing by PRRs leads to the immune activation of infected and accessory cells, accompanied by cytokine and chemokine production. The activation of innate immune cells may be a consecutive process, starting with macrophages and DCs and progressing to NK cells (13).

Macrophages

The macrophage is the component of the first line of immune defense against pathogens. It possesses a wide range of functions including cytokine and chemokine secretion, phagocytosis, production of nitric oxide, and antigen presentation (36, 37). Several years ago, it was found that chicken macrophages were susceptible to ALV-B/C, whereas ALV-A/D was excluded. These viruses could persist in macrophages for long periods (38, 39). However, the immunologic function of the macrophage-ALV interaction has not been followed up.

Recently, we determined that chicken primary monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) were susceptible to ALV-J (40). ALV-J strain SCAU-HN06 (41) rapidly increased the expression of Mx, ISG12-1, IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-β in MDM at early infection stages, but Mx, ISG12-1, and IL-10 expression decreased sharply at 36 h postinfection (40). This result indicated that ALV-J most likely escaped the innate immune response in chicken macrophages. Retroviruses have the ability to evade immune defense system and establish long-term persistence in the infected hosts. Macrophages play critical roles in HIV infection and can be a viral reservoir (42). We speculate that ALV-J also evades the innate immune response and establishes latent infections in chicken macrophages.

Dendritic Cells

As the most important professional antigen-presenting cells, DCs have a key role in the initiation and control of immunity (43). An ex vivo study demonstrated that ALV-J could infect bone marrow-derived DCs (BM-DCs) during the early stages of differentiation and trigger apoptosis (44). Further studies showed that ALV-J inhibits the differentiation and maturation of BM-DCs and alters cytokine expression, causing aberrant antigen presentation and an altered immune response (19).

As a central regulator of innate and adaptive immunity, DCs can stimulate T cells, antigen presentation, and secrete cytokines and chemokines (45, 46). In chickens, DCs-related research was initiated late because reproducible methods for culturing and characterizing this cell were only established in 2010 (47). The study on chicken DCs with ALV-J infection was still in the start stage, future studies are expected to unravel functions of chicken DCs.

Natural Killer Cells

Unfortunately, we only found one paper related to the interaction between NK cells and ALV infection (48). From an immunosuppression standpoint, this study indicated that ALV-J-infected chicken NK cells had a lower killing activity than the NK cells of the uninfected controls (48). This is a promising start and we await further work.

Natural killer cells play an important role in host defense and tumor surveillance, ending in target cell death and chemokine and cytokine secretion (49). In addition, NK cells have a key role in immune regulation. NK cells can regulate T cell and DC functions in mouse models of viral infection (50, 51). Given that ALV is tumorigenic and NK cells are central innate immune effectors, we believe that further exploration into NK cells and ALV interactions is worthwhile. This is especially important in terms of immune regulatory functions and tumor immunity.

Chicken macrophages and DCs can be directly infected by ALV and induce innate immunity (40, 44). However, we still have no clear knowledge of the regulation of the global innate immune response to ALV infection and ALV evasion of the host innate immune response. It is necessary to define the mechanisms of innate immune control in ALV infection to understand the virus-host relationship more deeply. This could result in a major contribution to ALV vaccine development by providing effective adjuvants that target innate immunity.

Adaptive Immune Responses

Humoral Immunity

Antibody responses to ALV are complex. Infection with ALV results in three classical infection profiles including (1) V+A− (viremia, no neutralizing antibody); (2) V+A+ (viremia, with neutralizing antibody); and (3) V−A+ (no viremia, with neutralizing antibody) (52, 53).

Congenital infection of chickens has been regarded as a classical model of immunologic tolerance that is demonstrated at the humoral level (10). Maternal antibodies against ALV-A influence the development of neutralizing antibody, viremia, and virus shedding (54). In general, an in ovo ALV infection results in persistent viremia lacking neutralizing antibody, and post-hatch ALV infection could potentially lead to clear the viruses by neutralizing antibody (55). Chickens infected with ALV-A after hatch often develop a transient viremia followed by an efficient neutralizing antibody response that is able to prevent viremia reappearance (52). However, high levels of ALV-J viremia can persist in the presence or absence of neutralizing antibody during the first 2 weeks post-hatch ALV-J infection (27, 56). This phenomenon suggests that an anti-ALV vaccine should be feasible.

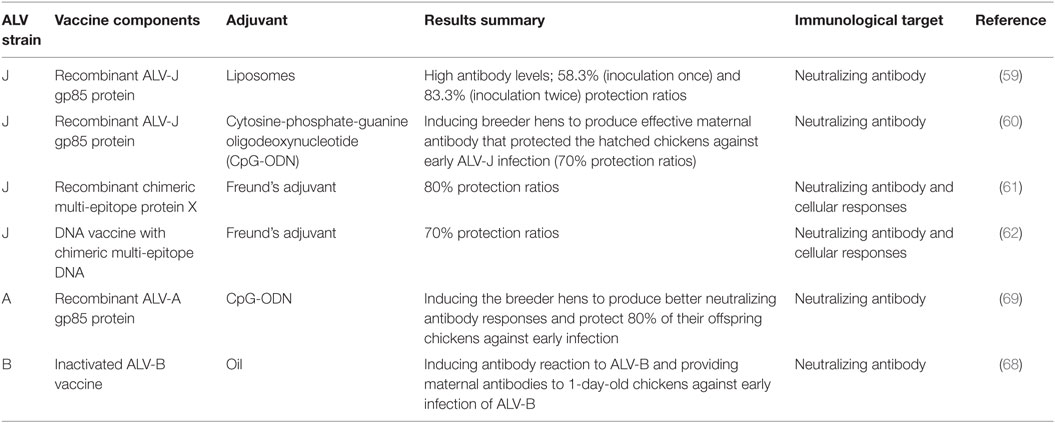

However, ALV is a retrovirus, like HIV-1, has an unstable genome especially concerning mutations in envelope glycoproteins (57, 58). Developing a vaccine to induce effective neutralization antibody for ALV prevention represents a great challenge. In addition, neutralization antibody may not be sufficient to counter variants (55). Despite this, numerous anti-ALV vaccines were still developed. The specific details on developed ALV vaccine could be found in Table 1.

The recombinant ALV-J gp85 protein vaccine provided with either a liposomal or a cytosine-phosphate-guanine oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODN) adjuvant did provide partial protection and elicited high antibody titers (59, 60). More interestingly, there has been a multi-epitope subunit vaccine developed that induced significant humoral and cellular immune responses in chickens against ALV-J infection (61). In a similar manner, a chimeric multi-epitope-based DNA vaccine can elicit higher antibody titers and cellular responses against an ALV-J challenge in chickens (62). The chimeric multi-epitope gene of ALV-J including 4 multi-epitope concentrated fragments (gag, pol, gp85, and gp37) encodes recombinant chimeric multi-epitope protein X containing both immunodominant B and T epitope (63). The vaccine with single antigen may lead to less immunogenicity and limited protection (64). However, multi-epitope based vaccines could increase immunogenicity and enhance immune responses due to containing epitopes of different target genes (65, 66). Thanks to cellular immune responses can complement antibody-mediated protection (67), we think the vaccine which provides antibody protection and induces cellular immune should be developed preferentially.

An inactivated ALV-B vaccine has been developed that could induce high antibody titers that protect from experimental ALV-B infections in chickens (68). An ALV-A gp85 protein subunit vaccine could induce neutralizing antibody when given with a CpG-ODN adjuvant to breeder hens. This protected 80% of their offspring chickens against early infections (69).

According to the published data, we found that the protection ratio of each developed vaccine is higher. However, we still doubt the vaccines’ effect because of fewer experimental animals and shorter monitoring time. In fact, none of the vaccines has a clinical application in chicken farms.

But nevertheless, the vaccine is still a kind of technical reserve to control ALV. What’s more, the development of an ALV vaccine may also serve as a model for HIV vaccine development. Therefore, exploring this avenue is worthy of our serious consideration. Recently, new B-cell epitopes in the P27 or gp85 proteins have been discovered, which holds promise as novel vaccine agents (70–72).

Cellular Immunity

There are limited studies concerning cellular immunity in ALV infections. A role for cellular immunity was correlated with immunosuppression of T-cell function in ALV-A infected chickens (73). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes were shown to play a role in the susceptibility or resistance of the various MHC-I haplotype chicken lines to ALV-A infection (74). However, the pathogenesis of immunosuppression caused by ALV-J may be associated with both B and T cells (9).

A key period for developing immunosuppression to ALV-J infection was identified as 3–4 weeks postinfection (9). At this stage, CD4+ T-cell numbers were significantly reduced and the CD8+ T-cell lymphocyte population increased in the spleen (9). Coincidentally, an untreated HIV infection is characterized by progressive CD4+ T cell depletion and CD8+ T cell expansion (75). Therefore, CD4+ T cells may be a primary target for ALV-J with CD8+ T cells playing an important role in host immunity.

Avian leukosis virus-J infection inhibits blood and splenic T lymphocyte proliferation and cytotoxicity in broilers. This effect can be enhanced by co-infection with reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV) (76). Interestingly, the joint application of Taishan Pinus massoniana pollen polysaccharides and propolis improved immune system effectiveness that included raising CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts as well as IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion in immunosuppressed chickens caused by ALV-J co-infection with REV (77). A separate study found chicken biliary exosomes significantly inhibited ALV-J replication and promoted proliferation of CD4+ (especially CD4+CD8–cells) as well as CD8+ T cells (35). However, whether the cellular immunity changed by biliary exosomes plays a dominant role by inhibiting ALV-J replication remains unknown.

A potential vaccine for ALV-J has been reported to induce significant increases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as IL-4 and IFN-γ levels in immunized chickens (61). Unfortunately, there have been few studies involved in the specific functions of T cells against ALV in the all cases described above.

We are sure that cellular immunity plays a critical role in ALV infection, but know little about the ALV-specific response. A full understanding of the ALV-specific cellular immune response is necessary to develop effective vaccines. Perhaps more importantly, this type of work can serve as a reference for HIV prevention and treatment with prophylactic vaccines or immunotherapies. Indeed, escape mutations and retrovirus latent infections are the main barriers in this effort.

Future Research

Many interesting scientific questions about ALV remain unresolved. Besides, cancer and AIDS are still great threats to human health. ALV studies might make a major contribution to conquer cancer and HIV as a research model. There are no vaccines to prevent HIV infection and many high-budget vaccine programs for HIV have continuously failed (78, 79). Developing ALV vaccine studies have a realistic significance and greater knowledge of immune system-ALV interactions may provide great insights into human retroviral diseases.

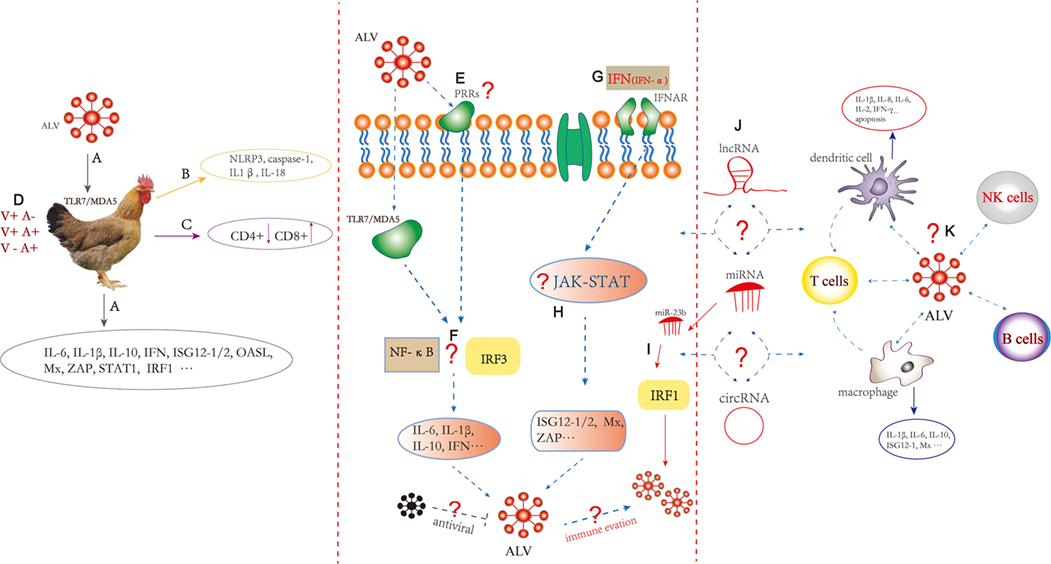

Figure 1 summarizes the comprehensive information in ALV immunology area and indicates that our future research should focus on chicken immunity system reacted with ALV. The specific PRRs, ISGs, and the activation of appropriate immune signaling pathways involved with ALV infection should be identified and characterized. The focus should lie on mechanisms of immune evasion and interactions with immune cell including macrophages, DCs, NK, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells. In addition, the function of endogenous avian leukemia virus in host immunity may be very important as well as interesting (80–82).

Figure 1. Innate and adaptive immune responses induced by Avian leukosis virus (ALV). (A) ALV infection in chickens may be recognized by TLR7 and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, followed by induction of innate immunity including differential expression of cytokine and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). (B) The expression of caspase-1 combined with adaptor NLRP3, IL-1β, and IL-18 increased in ALV-J-infected chick livers. (C) CD4+ T cell numbers decreased and CD8+ T cell numbers increased in the ALV-J-infected chicken spleen. (D) Infection with ALV results in three classical in vivo infection profiles including (1) V+A− (viremia, no neutralizing antibody); (2) V+A+ (viremia, with neutralizing antibody); and (3) V−A+ (no viremia, with neutralizing antibody). (E) The specific pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) to recognize ALV pathogen-associated molecular patterns should be further studied. (F) ALV-A/B/J infection can increase chicken interferon regulatory factors 3 (IRF3) promoter activity in DF-1 cells. Transcription factor such as IRF3 and NF-κB responses to ALV should be further clarified. (G) DF-1 cells pretreated with recombinant chicken IFN-α can inhibit the replication of ALV-A/B/J. (H) Immune signaling pathway such as PRRs signaling pathway (toll-like receptor, RIG-I-like receptors, interferon-γ-inducible protein 16, and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase) and JAK-STAT signaling pathway responses to ALV should be clarified; the specific mechanism of the inflammatory response, particularly the role of inflammasomes in sensing ALV should be further studied. What immune evasion strategies were used by ALV? Which antiviral factors inhibit the production of ALV? (I) miR-23b promotes ALV-J replication by targeting IRF1. (J) What is the role of non-coding RNAs including miRNA, long non-coding RNA, and circular RNA in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity induced by ALV? (K) ALV-J can infect chicken dendritic cells (DCs) during the early stages of differentiation and can trigger apoptosis. ALV-J inhibits the differentiation and maturation of DCs and alters cytokine expression that includes IL-1β, IL-8, and IFN-γ. Chicken macrophages are susceptible to ALV-J, and IL-1β, IL-6, ISG12-1, and Mx were altered. The interaction between ALV and macrophages, DCs, natural killer, B cells, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells needs to be further explored. The dotted line represents remaining processes not fully understood.

In the era of big data, we have access to lots of important information about the host or virus using new technologies such as RNA-Seq. Non-coding RNAs including miRNA, long non-coding RNA, and circular RNA are known to play roles in innate and adaptive immunity (21, 83, 84). Therefore, we also should pay attention to the role of non-coding RNAs in the host immune system with ALV infection.

Above all, we should insist on ALV vaccine development using the basic principles of immunology. Comprehensive understanding of the virus-host interaction would facilitate the development of a successful vaccine.

Conclusion

Avian leukosis virus-related immunology research is still in infancy. Despite our knowledge of immunosuppression, immunologic tolerance, and antibody response dynamics caused by ALV, there are still major gaps in our understanding of innate immunity and adaptive immunity against these viruses. Based on the limited references, we summarized the comprehensive information in ALV immunology area to assistance for further studies. We hope that the immunity studies of ALV contribute to a further understanding of cancer and AIDS in humans and in the poultry industry itself.

Author Contributions

MF and XZ drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Scientific Foundation of China (31571269) and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-42-G05).

References

1. Payne LN, Nair V. The long view: 40 years of Avian leukosis research. Avian Pathol (2012) 41:11–9. doi:10.1080/03079457.2011.646237

2. Malhotra S, Justice JT, Lee N, Li Y, Zavala G, Ruano M, et al. Complete genome sequence of an American Avian leukosis virus subgroup J isolate that causes hemangiomas and myeloid leukosis. Genome Announc (2015) 3:e01586–14. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01586-14

3. Pandiri AR, Gimeno IM, Mays JK, Reed WM, Fadly AM. Reversion to subgroup J Avian leukosis virus viremia in seroconverted adult meat-type chickens exposed to chronic stress by adrenocorticotrophin treatment. Avian Dis (2012) 56:578–82. doi:10.1637/9949-092611-ResNote.1

4. Zeng X, Liu L, Hao R, Han C. Detection and molecular characterization of J subgroup Avian leukosis virus in wild ducks in China. PLoS One (2014) 9:e94980. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094980

5. Li Y, Liu X, Liu H, Xu C, Liao Y, Wu X, et al. Isolation, identification, and phylogenetic analysis of two Avian leukosis virus subgroup J strains associated with hemangioma and myeloid leukosis. Vet Microbiol (2013) 166:356–64. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.06.007

6. Dong X, Zhao P, Li W, Chang S, Li J, Li Y, et al. Diagnosis and sequence analysis of Avian leukosis virus subgroup J isolated from Chinese Partridge Shank chickens. Poult Sci (2015) 94:668–72. doi:10.3382/ps/pev040

7. Wang Y, Li J, Li Y, Fang L, Sun X, Chang S, et al. Identification of ALV-J associated acutely transforming virus Fu-J carrying complete v-fps oncogene. Virus Genes (2016) 52:365–71. doi:10.1007/s11262-016-1301-6

8. Li D, Qin L, Gao H, Yang B, Liu W, Qi X, et al. Avian leukosis virus subgroup A and B infection in wild birds of Northeast China. Vet Microbiol (2013) 163:257–63. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.01.020

9. Wang F, Wang X, Chen H, Liu J, Cheng Z. The critical time of Avian leukosis virus subgroup J-mediated immunosuppression during early stage infection in specific pathogen-free chickens. J Vet Sci (2011) 12:235–41. doi:10.4142/jvs.2011.12.3.235

10. Qualtiere LF, Meyers P. A reexamination of humoral tolerance in chickens congenitally infected with an Avian leukosis virus. J Immunol (1979) 122:825–9.

11. Keestra AM, de Zoete MR, Bouwman LI, Vaezirad MM, van Putten JP. Unique features of chicken Toll-like receptors. Dev Comp Immunol (2013) 41:316–23. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2013.04.009

12. Chen H, Jiang Z. The essential adaptors of innate immune signaling. Protein cell (2013) 4:27–39. doi:10.1007/s13238-012-2063-0

13. Altfeld M, Gale M Jr. Innate immunity against HIV-1 infection. Nat Immunol (2015) 16:554–62. doi:10.1038/ni.3157

14. Loo YM, Gale M Jr. Viral regulation and evasion of the host response. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol (2007) 316:295–313.

15. Schoggins JW, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr Opin Virol (2011) 1:519–25. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.008

16. Nazli A, Kafka JK, Ferreira VH, Anipindi V, Mueller K, Osborne BJ, et al. HIV-1 gp120 induces TLR2- and TLR4-mediated innate immune activation in human female genital epithelium. J Immunol (2013) 191:4246–58. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1301482

17. Solis M, Nakhaei P, Jalalirad M, Lacoste J, Douville R, Arguello M, et al. RIG-I-mediated antiviral signaling is inhibited in HIV-1 infection by a protease-mediated sequestration of RIG-I. J Virol (2011) 85:1224–36. doi:10.1128/JVI.01635-10

18. Kane M, Case LK, Wang C, Yurkovetskiy L, Dikiy S, Golovkina TV. Innate immune sensing of retroviral infection via Toll-like receptor 7 occurs upon viral entry. Immunity (2011) 35:135–45. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.011

19. Liu D, Qiu Q, Zhang X, Dai M, Qin J, Hao J, et al. Infection of chicken bone marrow mononuclear cells with subgroup J Avian leukosis virus inhibits dendritic cell differentiation and alters cytokine expression. Infect Genet Evol (2016) 44:130–6. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2016.06.045

20. Hang B, Sang J, Qin A, Qian K, Shao H, Mei M, et al. Transcription analysis of the response of chicken bursa of Fabricius to Avian leukosis virus subgroup J strain JS09GY3. Virus Res (2014) 188:8–14. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.009

21. Li Z, Chen B, Feng M, Ouyang H, Zheng M, Ye Q, et al. MicroRNA-23b promotes Avian leukosis virus subgroup J (ALV-J) replication by targeting IRF1. Sci Rep (2015) 5:10294. doi:10.1038/srep10294

22. Feng M, Dai M, Xie T, Li Z, Shi M, Zhang X. Innate immune responses in ALV-J infected chicks and chickens with hemangioma in vivo. Front Microbiol (2016) 7:786. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00786

23. van Montfoort N, Olagnier D, Hiscott J. Unmasking immune sensing of retroviruses: interplay between innate sensors and host effectors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2014) 25:657–68. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.08.006

24. Magor KE, Navarro DM, Barber MRW, Petkau K, Fleming-Canepa X, Blyth GAD, et al. Defense genes missing from the flight division. Dev Comp Immunol (2013) 41:377–88. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2013.04.010

25. Mast J, Goddeeris BM. Development of immunocompetence of broiler chickens. Vet Immunol Immunopathol (1999) 70:245–56. doi:10.1016/S0165-2427(99)00079-3

26. Gao Y, Liu Y, Guan X, Li X, Yun B, Qi X, et al. Differential expression of immune-related cytokine genes in response to J group Avian leukosis virus infection in vivo. Mol Immunol (2015) 64:106–11. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2014.11.004

27. Witter RL, Fadly AM. Reduction of horizontal transmission of Avian leukosis virus subgroup J in broiler breeder chickens hatched and reared in small groups. Avian Pathol (2001) 30:641–54. doi:10.1080/03079450120092134

28. Dai M, Wu S, Feng M, Feng S, Sun C, Bai D, et al. Recombinant chicken interferon-alpha inhibits the replication of exogenous Avian leukosis virus (ALV) in DF-1 cells. Mol Immunol (2016) 76:62–9. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2016.06.012

29. Sabat R, Grutz G, Warszawska K, Kirsch S, Witte E, Wolk K, et al. Biology of interleukin-10. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2010) 21:331–44. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.002

30. Liu XL, Shan WJ, Jia LJ, Yang X, Zhang JJ, Wu YR, et al. Avian leukosis virus subgroup J triggers caspase-1-mediated inflammatory response in chick livers. Virus Res (2016) 215:65–71. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2016.01.011

31. Shrivastava G, Leon-Juarez M, Garcia-Cordero J, Meza-Sanchez DE, Cedillo-Barron L. Inflammasomes and its importance in viral infections. Immunol Res (2016) 64:1101–17. doi:10.1007/s12026-016-8873-z

32. Goossens KE, Karpala AJ, Ward A, Bean AG. Characterisation of chicken ZAP. Dev Comp Immunol (2014) 46:373–81. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2014.05.011

33. Goossens KE, Karpala AJ, Rohringer A, Ward A, Bean AG. Characterisation of chicken viperin. Mol Immunol (2015) 63:373–80. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2014.09.011

34. Magor KE, Miranzo Navarro D, Barber MR, Petkau K, Fleming-Canepa X, Blyth GA, et al. Defense genes missing from the flight division. Dev Comp Immunol (2013) 41:377–88. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2013.04.010

35. Wang Y, Wang G, Wang Z, Zhang H, Zhang L, Cheng Z. Chicken biliary exosomes enhance CD4(+)T proliferation and inhibit ALV-J replication in liver. Biochem Cell Biol (2014) 92:145–51. doi:10.1139/bcb-2013-0096

36. Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature (2013) 496:445–55. doi:10.1038/nature12034

37. Qureshi MA, Heggen CL, Hussain I. Avian macrophage: effector functions in health and disease. Dev Comp Immunol (2000) 24:103–19. doi:10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00067-1

38. Gazzolo L, Moscovici MG, Moscovici C, Vogt PK. Susceptibility and resistance of chicken macrophages to avian RNA tumor viruses. Virology (1975) 67:553–65. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(75)90455-9

39. Gazzolo L, Moscovici C, Moscovici MG. Persistence of avian oncoviruses in chicken macrophages. Infect Immun (1979) 23:294–7.

40. Feng M, Dai M, Cao W, Tan Y, Li Z, Shi M, et al. ALV-J strain SCAU-HN06 induces innate immune responses in chicken primary monocyte-derived macrophages. Poult Sci (2016):1–9. doi:10.3382/ps/pew229

41. Lai H, Zhang H, Ning Z, Chen R, Zhang W, Qing A, et al. Isolation and characterization of emerging subgroup J Avian leukosis virus associated with hemangioma in egg-type chickens. Vet Microbiol (2011) 151:275–83. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.03.037

42. Campbell JH, Hearps AC, Martin GE, Williams KC, Crowe SM. The importance of monocytes and macrophages in HIV pathogenesis, treatment, and cure. AIDS (2014) 28:2175–87. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000408

43. Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science (2010) 327:656–61. doi:10.1126/science.1178331

44. Liu D, Dai M, Zhang X, Cao W, Liao M. Subgroup J Avian leukosis virus infection of chicken dendritic cells induces apoptosis via the aberrant expression of microRNAs. Sci Rep (2016) 6:20188. doi:10.1038/srep20188

45. Izquierdo-Useros N, Lorizate M, McLaren PJ, Telenti A, Krausslich HG, Martinez-Picado J. HIV-1 capture and transmission by dendritic cells: the role of viral glycolipids and the cellular receptor Siglec-1. PLoS Pathog (2014) 10:e1004146. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004146

46. Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell (2001) 106:255–8. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00449-4

47. Wu Z, Rothwell L, Young JR, Kaufman J, Butter C, Kaiser P. Generation and characterization of chicken bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Immunology (2010) 129:133–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03129.x

48. Landman WJ, Post J, Boonstra-Blom AG, Buyse J, Elbers AR, Koch G. Effect of an in ovo infection with a Dutch Avian leukosis virus subgroup J isolate on the growth and immunological performance of SPF broiler chickens. Avian Pathol (2002) 31:59–72. doi:10.1080/03079450120106633

49. Paolini R, Bernardini G, Molfetta R, Santoni A. NK cells and interferons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2015) 26:113–20. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.11.003

50. Andrews DM, Estcourt MJ, Andoniou CE, Wikstrom ME, Khong A, Voigt V, et al. Innate immunity defines the capacity of antiviral T cells to limit persistent infection. J Exp Med (2010) 207:1333–43. doi:10.1084/jem.20091193

51. Waggoner SN, Cornberg M, Selin LK, Welsh RM. Natural killer cells act as rheostats modulating antiviral T cells. Nature (2011) 481:394–8. doi:10.1038/nature10624

52. Pandiri AR, Reed WM, Mays JK, Fadly AM. Influence of strain, dose of virus, and age at inoculation on subgroup J Avian leukosis virus persistence, antibody response, and oncogenicity in commercial meat-type chickens. Avian Dis (2007) 51:725–32. doi:10.1637/0005-2086(2007)51[725:IOSDOV]2.0.CO;2

53. Wang Q, Li X, Ji X, Wang J, Shen N, Gao Y, et al. A recombinant Avian leukosis virus subgroup j for directly monitoring viral infection and the selection of neutralizing antibodies. PLoS One (2014) 9:e115422. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115422

54. Fadly AM. Avian leukosis virus (ALV) infection, shedding, and tumors in maternal ALV antibody-positive and -negative chickens exposed to virus at hatching. Avian Dis (1988) 32:89–95. doi:10.2307/1590954

55. Pandiri AR, Mays JK, Silva RF, Hunt HD, Reed WM, Fadly AM. Subgroup J Avian leukosis virus neutralizing antibody escape variants contribute to viral persistence in meat-type chickens. Avian Dis (2010) 54:848–56. doi:10.1637/9085-092309-Reg.1

56. Fadly AM, Smith EJ. Isolation and some characteristics of a subgroup J-like Avian leukosis virus associated with myeloid leukosis in meat-type chickens in the United States. Avian Dis (1999) 43:391–400. doi:10.2307/1592636

57. Venugopal K, Smith LM, Howes K, Payne LN. Antigenic variants of J subgroup Avian leukosis virus: sequence analysis reveals multiple changes in the env gene. J Gen Virol (1998) 79(Pt 4):757–66. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-79-4-757

58. Nichol S, viruses RNA. Life on the edge of catastrophe. Nature (1996) 384:218–9. doi:10.1038/384218a0

59. Zhang L, Cai D, Zhao X, Cheng Z, Guo H, Qi C, et al. Liposomes containing recombinant gp85 protein vaccine against ALV-J in chickens. Vaccine (2014) 32:2452–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.091

60. Dou W, Li H, Cheng Z, Zhao P, Liu J, Cui Z, et al. Maternal antibody induced by recombinant gp85 protein vaccine adjuvanted with CpG-ODN protects against ALV-J early infection in chickens. Vaccine (2013) 31:6144–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.058

61. Xu Q, Ma X, Wang F, Li H, Zhao X. Evaluation of a multi-epitope subunit vaccine against Avian leukosis virus subgroup J in chickens. Virus Res (2015) 210:62–8. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2015.06.024

62. Xu Q, Cui N, Ma X, Wang F, Li H, Shen Z, et al. Evaluation of a chimeric multi-epitope-based DNA vaccine against subgroup J Avian leukosis virus in chickens. Vaccine (2016) 34:3751–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.004

63. Xu Q, Ma X, Wang F, Li H, Xiao Y, Zhao X. Design and construction of a chimeric multi-epitope gene as an epitope-vaccine strategy against ALV-J. Protein Expr Purif (2015) 106:18–24. doi:10.1016/j.pep.2014.10.007

64. Gil LA, da Cunha CE, Moreira GM, Salvarani FM, Assis RA, Lobato FC, et al. Production and evaluation of a recombinant chimeric vaccine against clostridium botulinum neurotoxin types C and D. PLoS One (2013) 8:e69692. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069692

65. Agallou M, Athanasiou E, Koutsoni O, Dotsika E, Karagouni E. Experimental validation of multi-epitope peptides including promising MHC class I- and II-restricted epitopes of four known Leishmania infantum proteins. Front Immunol (2014) 5:268. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00268

66. Grassmann AA, Felix SR, dos Santos CX, Amaral MG, Seixas Neto AC, Fagundes MQ, et al. Protection against lethal leptospirosis after vaccination with LipL32 coupled or coadministered with the B subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2012) 19:740–5. doi:10.1128/CVI.05720-11

67. Haynes BF, Shaw GM, Korber B, Kelsoe G, Sodroski J, Hahn BH, et al. HIV-host interactions: implications for vaccine design. Cell Host Microbe (2016) 19:292–303. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.02.002

68. Li X, Dong X, Sun X, Li W, Zhao P, Cui Z, et al. Preparation and immunoprotection of subgroup B Avian leukosis virus inactivated vaccine. Vaccine (2013) 31:5479–85. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.072

69. Zhang D, Li H, Zhang Z, Sun S, Cheng Z, Liu J, et al. Antibody responses induced by recombinant ALV-A gp85 protein vaccine combining with CpG-ODN adjuvant in breeder hens and the protection for their offspring against early infection. Antiviral Res (2015) 116:20–6. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.01.007

70. Hou M, Zhou D, Li G, Guo H, Liu J, Wang G, et al. Identification of a variant antigenic neutralizing epitope in hypervariable region 1 of Avian leukosis virus subgroup J. Vaccine (2016) 34:1399–404. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.039

71. Li X, Zhu H, Wang Q, Sun J, Gao Y, Qi X, et al. Identification of a novel B-cell epitope specific for Avian leukosis virus subgroup J gp85 protein. Arch Virol (2015) 160:995–1004. doi:10.1007/s00705-014-2318-6

72. Li X, Qin L, Zhu H, Sun Y, Cui X, Gao Y, et al. Identification of a linear B-cell epitope on the Avian leukosis virus P27 protein using monoclonal antibodies. Arch Virol (2016) 161:2871–7. doi:10.1007/s00705-016-2971-z

73. Fadly AM, Lee LF, Bacon LD. Immunocompetence of chickens during early and tumorigenic stages of Rous-associated virus-1 infection. Infect Immun (1982) 37:1156–61.

74. Thacker EL, Fulton JE, Hunt HD. In vitro analysis of a primary, major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to Avian leukosis virus (ALV), using target cells expressing MHC class I cDNA inserted into a recombinant ALV vector. J Virol (1995) 69:6439–44.

75. Freeman ML, Shive CL, Nguyen TP, Younes SA, Panigrahi S, Lederman MM. Cytokines and T-cell homeostasis in HIV infection. J Infect Dis (2016) 214(Suppl 2):S51–7. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw287

76. Guo H-J, Li H-M, Cheng Z-Q, Liu J-Z, Cui Z-Z. Influence of REV and ALV-J co-infection on immunologic function of T lymphocytes and histopathology in broiler chickens. Agric Sci China (2010) 9:1667–76. doi:10.1016/S1671-2927(09)60264-9

77. Li B, Wei K, Yang S, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Zhu F, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of Taishan Pinus massoniana pollen polysaccharide and propolis on immunosuppressed chickens. Microb Pathog (2015) 78:7–13. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2014.11.010

78. Hammer SM, Sobieszczyk ME, Janes H, Karuna ST, Mulligan MJ, Grove D, et al. Efficacy trial of a DNA/rAd5 HIV-1 preventive vaccine. N Engl J Med (2013) 369:2083–92. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310566

79. Yates NL, Liao HX, Fong Y, deCamp A, Vandergrift NA, Williams WT, et al. Vaccine-induced Env V1-V2 IgG3 correlates with lower HIV-1 infection risk and declines soon after vaccination. Sci Transl Med (2014) 6:228ra39. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3007730

80. Chuong EB, Elde NC, Feschotte C. Regulatory evolution of innate immunity through co-option of endogenous retroviruses. Science (2016) 351:1083–7. doi:10.1126/science.aad5497

81. Hurst TP, Magiorkinis G. Activation of the innate immune response by endogenous retroviruses. J Gen Virol (2015) 96:1207–18. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000017

82. Feng M, Tan Y, Dai M, Li Y, Xie T, Li H, et al. Endogenous retrovirus ev21 dose not recombine with ALV-J and induces the expression of ISGs in the host. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2016) 6:140. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2016.00140

83. Aune TM, Spurlock CF III. Long non-coding RNAs in innate and adaptive immunity. Virus Res (2016) 212:146–60. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2015.07.003

Keywords: ALV, innate immunity, adaptive immunity, chicken, retrovirus

Citation: Feng M and Zhang X (2016) Immunity to Avian Leukosis Virus: Where Are We Now and What Should We Do? Front. Immunol. 7:624. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00624

Received: 18 August 2016; Accepted: 08 December 2016;

Published: 21 December 2016

Edited by:

Wenzhe Ho, Temple University School of Medicine, USAReviewed by:

Xun Suo, China Agricultural University, ChinaYafeng Wang, Zhengzhou University, China

Ziqiang Cheng, Shandong Agricultural University, China

Copyright: © 2016 Feng and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiquan Zhang, eHF6aGFuZ0BzY2F1LmVkdS5jbg==

Min Feng

Min Feng Xiquan Zhang1,2*

Xiquan Zhang1,2*