- Faculdade de Medicina, Instituto de Medicina Molecular, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

γδ T cells are unconventional innate-like lymphocytes that actively participate in protective immunity against tumors and infectious organisms including bacteria, viruses, and parasites. However, γδ T cells are also involved in the development of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. γδ T cells are functionally characterized by very rapid production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while also impacting on (slower but long-lasting) adaptive immune responses. This makes it crucial to understand the molecular mechanisms that regulate γδ T cell effector functions. Although they share many similarities with αβ T cells, our knowledge of the molecular pathways that control effector functions in γδ T cells still lags significantly behind. In this review, we focus on the segregation of interferon-γ versus interleukin-17 production in murine thymic-derived γδ T cell subsets defined by CD27 and CCR6 expression levels. We summarize the most recent studies that disclose the specific epigenetic and transcriptional mechanisms that govern the stability or plasticity of discrete pro-inflammatory γδ T cell subsets, whose manipulation may be valuable for regulating (auto)immune responses.

γδ T cells, which were discovered three decades ago (1–3), remain a very puzzling population of lymphocytes. Together with αβ T cells and B cells, they make up the three somatically rearranged lineages that are found in all jawed and also in jawless vertebrates (lampreys and hagfish) (4, 5), thus highlighting a strong evolutionary pressure to keep the three lymphocyte lineages together.

One of the most striking characteristics of γδ T cells is their inherent ability to very rapidly secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines. This is likely attributable to the functional maturity of discrete γδ T cell subsets, producing either IFN-γ or IL-17, that readily populate secondary lymphoid organs (as well as peripheral tissues) where they make a key contribution to “lymphoid stress surveillance” (6). We (7) and others (8, 9) have shown that these functional γδ T cell subsets develop in the murine thymus before migration to peripheral sites (10). This review outlines our current molecular understanding of the development and function of γδ T cell subsets that influence both innate and acquired immunity.

Roles of IFN-γ and IL-17-Producing γδ T Cells in Immune Responses

By secreting large amounts of IFN-γ, γδ T cells participate in controlling infection through the activation of macrophages and cytotoxic lymphocytes. IFN-γ producing γδ T cells have been shown to play major protective roles during murine West Nile, herpes and influenza viral infections (11–13); Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, and Bordetella pertussis bacterial infections (14–18); and Plasmodium chabaudi and Toxoplasma gondii parasitic infections (19–22). Moreover, γδ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes constitute a critical early source of IFN-γ that controls tumor development in vivo (23, 24).

With respect to the production of IL-17, γδ T cells are a key component of the defense against infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, E. coli, L. monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and Pneumococci (18, 25–32). One of the main functions of these IL-17-producing γδ T cells is to enable extremely fast neutrophil recruitment at the site of infection.

On the other hand, IL-17-producing γδ T cells have pathogenic roles in various inflammatory and autoimmune disorders (and animal models thereof), including collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) (33), experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (8, 34–38), chronic granulomatous disease (39), uveitis (40), ischemic brain inflammation (41), colitis (42, 43), and psoriasis (44, 45). Moreover, IL-17 also seems to promote angiogenesis and consequently tumor growth (46) and metastasis (47).

Therefore, from a therapeutic point of view, it is of utmost importance: (i) to define in detail the γδ T cell subset(s) that perform each given function; (ii) to understand the extracellular clues that regulate the development of each subset; and (iii) to identify the molecular program(s) of differentiation that control the acquisition and maintenance of a specific effector function.

Here we will essentially focus on mouse models, but to emphasize the relevance of studying specific murine effector γδ T cell subsets we will highlight their human counterparts. For a comprehensive review on the differentiation of human γδ T cells please refer to Ref. (48). Moreover, although the present review focuses on IFN-γ- and IL-17-secreting γδ T cells, we note that some γδ cell subsets produce other cytokines including IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 (49–51), IL-10 (52, 53), and IL-22 (54–56).

Phenotypic Description of IFN-γ- or IL-17-Producing γδ T Cell Subsets

Functional γδ T cell subsets in the mouse have been traditionally defined by their TCR Vγ usage [please note that we use the nomenclature proposed by Heilig and Tonegawa (57)] and preferential tissue distribution. For example, epidermal Vγ5Vδ1 T cells are mainly associated with the production of IFN-γ (58), although they have also been shown to produce IL-17 in response to skin injury (59). Vγ6Vδ1 T cells that are present in the tongue, lungs, and reproductive tracts mainly produce IL-17. Moreover, Vγ1 T cells colonize the liver, spleen, and intestine preferentially secrete IFN-γ, whereas Vγ4 T cells, which recirculate through blood, spleen, and lymph nodes, and are also located in the lungs, favor IL-17 production. However, this dichotomy is not so strict as mouse Vγ4 T cells produce IFN-γ or IL-17 depending on the model studied (7, 60, 61).

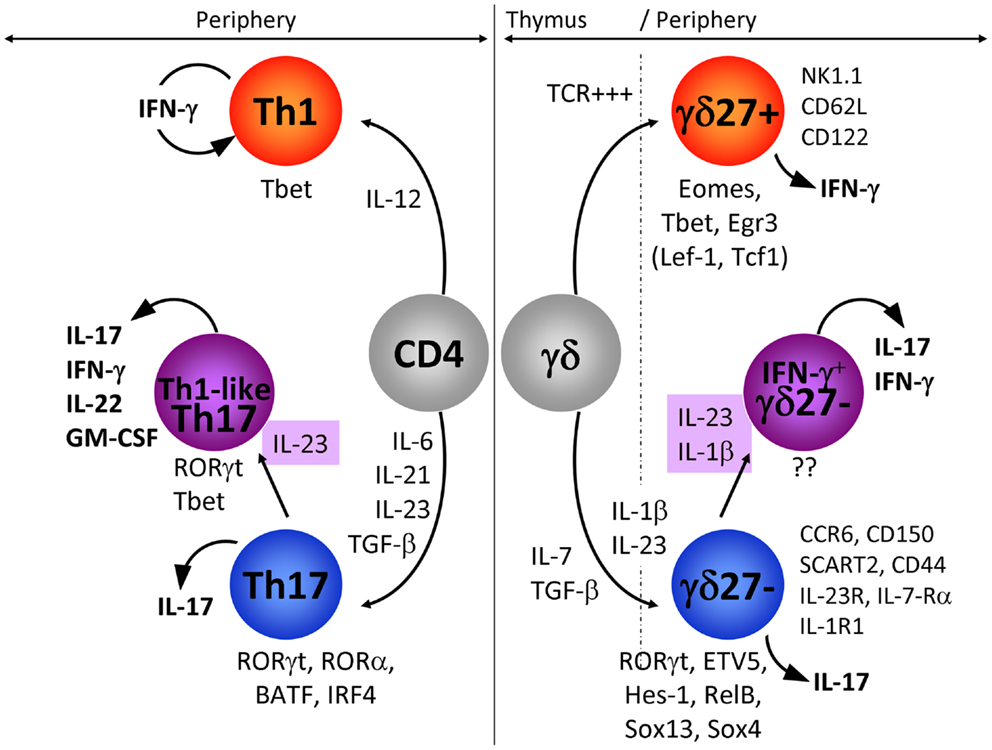

Although a genome-wide transcriptional profiling of γδ thymocytes segregated the expression of some genes associated with IFN-γ or IL-17 production with selective Vγ chain usage (62), work from our laboratory (7), together with others (8, 63), has shown that γδ T cell functions are not mutually exclusive between Vγ1 and Vγ4 T cell subsets. Our collective efforts have identified CD27 and CCR6 as useful markers of discrete pro-inflammatory γδ T cell subsets: CD27 is expressed on IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells whereas IL-17-producing γδ T cells are CD27(−) but express CCR6 (7, 54, 63) (see Figure 1 for further details). Of note, CD122 and NK1.1 constitute additional markers of IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells (8, 63). Consequently, we favor categorization of γδ T cell subsets based on their effector functions rather than on TCR Vγ usage (10). The definition of surface phenotypes associated with effector cell functions has greatly facilitated the dissection of the molecular mechanisms that control the differentiation of IFN-γ- or IL-17-producing γδ T cells.

Figure 1. IFN-γ-producing and IL-17-producing CD4 and γδ T cells. In this figure, we have compared the extracellular signals and the transcriptional networks that regulate IFN-γ or IL-17 production in CD4 (left: Th1 and Th17) and γδ (right: γδ27+ and γδ27−) T cells. In addition, the expression pattern of markers specifically associated with IFN-γ-producing γδ27+ and IL-17-producing γδ27− T cells is detailed. The emergence of IL-17+ IFN-γ+ T cells is highlighted for both CD4 and γδ T cells. Of note, the transcription factors in parenthesis (TCF1 and LEF1) below γδ27+ T cells have been proposed to inhibit IL-17 production in these cells.

Differences in Cytokine Production between γδ and CD4 T Cells

One of the main differences between cytokine production by γδ and CD4 T cells resides in the spontaneous release of cytokine by γδ T cells, which strikingly contrasts with the delayed response of naïve CD4 T cells. This can be explained by γδ T cells exiting the thymus already functionally competent to produce either IFN-γ or IL-17 (7–9, 64), whereas CD4 T cells require a long differentiation program in peripheral lymphoid organs that consists of activation, intense proliferation, and induction of transcription factors that selectively control the profile of cytokines produced (65). As CD4 T helper cells have been extensively studied, it is reasonable to question if the programs of differentiation that prevail in CD4 T cells also operate in γδ T cells. Here we will focus on the molecular mechanisms that govern the differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells into IFN-γ-producing (Th1) and IL-17-producing (Th17) cells, as counterparts to CD27+ (γδ27+) and CD27−CCR6+ (γδ27−) γδ T cell subsets, respectively.

Environmental Cues that Govern the Acquisition of Types 1 or 17 Effector Functions

Upon peripheral activation, naïve CD4 T cells are polarized toward the Th1 fate in the presence of IL-12 (66). As yet, there is no precise information as to the role of IL-12 in the development of γδ27+ T cells although IL-12 (in synergy with IL-18) induces the production of IFN-γ by γδ27+ T cells expressing NK1.1 (63). Our unpublished data suggest that IL-15 and, to a lesser extent IL-2, strongly promote IFN-γ production by γδ27+ T cells (Barros-Martins et al., manuscript in preparation).

Th17 polarization entails TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-1β, whereas IL-23 is required for maintenance and expansion (67–69). Although still controversial, the development of IL-17-producing γδ T cells in the thymus (and their maintenance in the periphery) appears to be dependent on TGF-β but mostly independent of IL-6 (9, 70–73). Unexpectedly, IL-7 induced rapid and substantial expansion of IL-17-producing γδ27−T cells (74). Furthermore, they require IL-23 and IL-1β for peripheral expansion and local induction of IL-17 (30, 75, 76). This is clearly evidenced by the significant reduction in IL-17-secreting γδ T cell numbers following L. monocytogenes infection in IL-23−/− and IL-23R−/− mice (72, 77) or in IL-1R1−/− mice upon EAE induction (36). It was also shown that IL-18 synergizes with IL-23 to promote IL-17 production by γδ T cells (78). IL-17 production by γδ T cells can be triggered independently of TCR signaling (36, 54, 76), but it is worth noting that a small subset of CD44+CD62L+ γδ T cells (a phenotype associated with γδ27+ cells; see Figure 1) selectively recognized phycoerythrin via the TCR and became CD44+++CD62L− cells that produced IL-17 (79). In this system too, propagation of the IL-17-response by PE-specific γδ T cells relies on IL-23. Finally, it has been shown that IL-17 derived from CD4 T cells is a negative regulator of IL-17+ γδ T cell development in adult thymus (64), underlying the potential danger that large numbers of these pro-inflammatory cells likely represent to the host.

Transcriptional Regulation of Cytokine Production in γδ and CD4 T Cells

During Th1 polarization of naïve CD4 T cells, IL-12 activates STAT4 (80), but it is unclear if this IL-12/STAT4 axis plays any role in IFN-γ production by γδ27+ T cells. The “master” transcription factor that regulates the production of IFN-γ in CD4 T cells is T-bet (81, 82). Whereas Th1 differentiation is fully abrogated in the absence of T-bet, γδ27+ T cells only partially require T-bet to produce IFN-γ (83–85). Other transcription factors that have been proposed to play major roles in γδ T cells include Eomes and Egr3 (58, 84), although the potential cooperation between these three transcription factors within specific γδ T cell subsets still needs to be clarified.

Th17 differentiation relies on cytokines that target STAT3 and lead to the expression of the master transcription factor retinoic-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt) (86) that synergizes with RORα (87), together with IRF4 (88) and BATF (89) to propagate IL-17 production. In vivo Th17 cell differentiation also involves the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (90, 91). All together this led to the concept that a specific transcriptional network is operating during initiation and stabilization of the Th17 phenotype (92).

IL-17 production by γδ27−T cells is also strictly dependent on RORγt (70, 85, 86, 93). However, the similarities between the Type 17 program of γδ and CD4 T cells end with this transcription factor, since STAT3 and IRF4 have been shown to be dispensable for the differentiation of IL-17+ γδ T cells (93, 94). Of note, detection of IL-17+ γδ T cells in STAT3-deficient mice further suggests that IL-6, IL-21, and IL-23 are unlikely to play major roles for their development, although they may be involved in peripheral reactivation of these γδ cells. AhR has also been shown to be dispensable for IL-17 but required for IL-22 production by γδ T cells (54). Finally, our unpublished data show that IL-17-producing γδ T cells are generated in the absence of RORα or BATF (Barros-Martins et al., manuscript in preparation). Thus, many transcription factors that are essential for Th17 development are not required for the differentiation of their IL-17+ γδ T cell counterparts.

In fact, γδ27−T cells appear to rely on distinct molecular pathways to regulate their production of IL-17. Namely, several transcription factors such as Sox13 and Sox4 (95, 96), Hes-1 (93), RelB (97), ETV5 (98) along with the kinase Blk (99), selectively participate in IL-17 production by γδ T cells. On the other hand, TCF1 and LEF1 are negative regulators of IL-17 expression in γδ T cells (96).

These data clearly highlight that distinct mechanisms govern the production of IFN-γ and IL-17 in CD4 and γδ T cells (Figure 1). Further studies are warranted to precisely delineate the molecular components of the Types 1 and 17 programs of γδ T cells.

Stability Versus Plasticity of γδ T Cell Subsets

Initially studies suggested that the segregation between IL-17 and IFN-γ production that emerged in the thymus appeared to be stable in the two γδ T cell subsets, including in peripheral lymphoid organs and upon challenge with infectious agents in vivo (7, 76). Furthermore, incubating the γδ27+ cells in Th17 conditioning milieu, or the γδ27− cells in Th1 conditioning milieu, failed to “convert” their cytokine production profile (63, 85). It was therefore assumed that, due to thymic “functional pre-commitment,” murine γδ T cells harbored little plasticity, in stark contrast with CD4 T cells (100).

To get further insight into the molecular mechanisms of stable commitment of the γδ27+ and γδ27− T cell subsets to their respective effector functions, we undertook the first genome-wide comparison of the chromatin landscape of these two γδ T cell subsets. We analyzed the distribution of methylation marks on histone H3 (H3). Methylation of lysine 4 (H3K4me2/3) signs actively transcribed loci, whereas methylation of lysine 27 (H3K27me3) represses the accessibility for the transcriptional machinery (101, 102). As expected, we found that gene loci associated with IL-17 production harbored active histone modifications only in γδ27−T cells. By contrast, and to our surprise, gene loci associated with IFN-γ showed active H3K4me2 profiles in both γδ T cell subsets. Furthermore, whereas Il17 and related genes were exclusively transcribed in γδ27−cells, Ifng and genes that control its expression were transcribed in both γδ27+ and γδ27−T cells (although to a lesser extent in the latter subset). Thus, Ifng and “Type 1” factors are epigenetically and transcriptionally primed for expression in both γδ27+ and γδ27−T cells, which led us to hypothesize that γδ27− T cells could acquire IFN-γ expression under specific conditions.

Identification of γδ IL-17+ IFN-γ+ Double Producers

By performing a series of in vitro experiments, we found that IL-1β strongly synergizes with IL-23 to induce IFN-γ expression specifically in IL-17-producing γδ27−cells (Figure 1). Importantly, epigenetic and transcriptional polarization of IL-1R1 and IL-23R predicted the responsiveness of γδ27− cells, but not γδ27+ cells, to these two inflammatory cytokines.

This plastic behavior of γδ27−T cells was also observed in vivo, as IL-17+ IFN-γ+ γδ27−cells could be found in the peritoneal cavity of mice bearing ovarian tumors (85). Moreover, these cells have been detected in the brain of mice suffering from early stages of EAE (103); and in the mesenteric lymph nodes of mice infected with L. monocytogenes (104).

Double producing IL-17+ IFN-γ+ γδ T cells have also been characterized in humans. Thus, while a fraction of neonatal and adult Vγ9Vδ2 T cells incubated with IL-6, IL-1β, and TGF-β in the presence of TCR agonists produced IL-17A, the addition of IL-23 resulted in IFN-γ co-production (105). Moreover, IL-17+ IFN-γ+ cells of both Vδ1 and Vδ2 subtypes were found in the circulation of HIV+ patients (106).

Thus, although their precise physiological relevance is still to be established, IL-17+ IFN-γ+ double producers can clearly be a distinct component of the γδ T cell response in scenarios of infection, cancer, and autoimmunity.

CD4 IL-17+ IFN-γ+ Double Producers and Their Biological Relevance

IL-17+ IFN-γ+ double producers have been well characterized in the CD4 T cell compartment (Figure 1). In particular, both murine (107, 108) and human (109–111) Th17 cells often show plasticity in acquiring IFN-γ production. Strikingly, these IFN-γ+ (Th1-like) Th17 cells have been strongly associated with pathogenicity in murine (107, 112, 113) and human (114) autoimmune syndromes. The molecular determinants of pathogenicity of Th1-like Th17 cells are still controversial, with studies either implicating T-bet and IFN-γ (108, 112, 115) or not (116–118). Nonetheless, it is clear that IL-23 is a major driver of Th1-like Th17 cell pathogenicity (108, 112, 117).

Similar studies on in vivo models should now explore the potential pathogenic role of γδ IL-17+ IFN-γ+ double producers. This notwithstanding, it has been proposed that, in response to L. monocytogenes, IL-17+/IFN-γ+ producing γδ27− cells become memory cells capable of providing enhanced protection against recall infection (104). Thus, γδ IL-17+ IFN-γ+ double producers may potentially play host-protective versus pathogenic roles in distinct disease models, which will be an interesting topic for future research.

Concluding Remarks

As a population, γδ T cells perform a wide variety of functions, but discrete subsets have more restricted effector properties. Although thymic development endows a significant fraction of murine γδ T cells with a “pre-determined” effector function, recent data provide strong evidence for functional plasticity in the periphery (particularly for γδ27−T cells).

Several fundamental questions remain unanswered. Is functional plasticity restricted to γδ T cells located in secondary lymphoid organs or does it extend to subsets that populate epithelial tissues/mucosas? Why did γδ T cells and CD4 T cells evolve different transcriptional networks to regulate the production of the same pro-inflammatory cytokines? What are the specific roles of γδ IL-17+ IFN-γ+ double producers in models of infection, cancer, and autoimmunity? More globally, it will be important to dissect the physiological stimuli that drive the activation of effector γδ T cells. It is particularly puzzling that we still know so little about the role of the TCRγδ, and the identity of its ligands, in the differentiation and activation of functional γδ T cell subsets. Answering these questions will improve our understanding of γδ T cell physiology and likely provide new avenues for the design of immunotherapeutic approaches.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joana Barros-Martins for unpublished data mentioned here and for reading the manuscript. Our work is funded by the European Research Council (StG_260352) and the European Molecular Biology Organization Young Investigator Program. Karine Serre is funded by an individual fellowship from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia.

References

1. Saito H, Kranz DM, Takagaki Y, Hayday AC, Eisen HN, Tonegawa S. Complete primary structure of a heterodimeric T-cell receptor deduced from cDNA sequences. Nature (1984) 309(5971):757–62. doi:10.1038/309757a0

2. Brenner MB, McLean J, Dialynas DP, Strominger JL, Smith JA, Owen FL, et al. Identification of a putative second T-cell receptor. Nature (1986) 322(6075):145–9. doi:10.1038/322145a0

3. Saito H, Kranz DM, Takagaki Y, Hayday AC, Eisen HN, Tonegawa S. A third rearranged and expressed gene in a clone of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature (1984) 312(5989):36–40. doi:10.1038/312036a0

4. Hirano M, Guo P, McCurley N, Schorpp M, Das S, Boehm T, et al. Evolutionary implications of a third lymphocyte lineage in lampreys. Nature (2013) 501(7467):435–8. doi:10.1038/nature12467

5. Li J, Das S, Herrin BR, Hirano M, Cooper MD. Definition of a third VLR gene in hagfish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013) 110(37):15013–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314540110

6. Hayday AC. Gammadelta T cells and the lymphoid stress-surveillance response. Immunity (2009) 31(2):184–96. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.006

7. Ribot JC, deBarros A, Pang DJ, Neves JF, Peperzak V, Roberts SJ, et al. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-gamma- and interleukin 17-producing gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat Immunol (2009) 10(4):427–36. doi:10.1038/ni.1717

8. Jensen KD, Su X, Shin S, Li L, Youssef S, Yamasaki S, et al. Thymic selection determines gammadelta T cell effector fate: antigen-naive cells make interleukin-17 and antigen-experienced cells make interferon gamma. Immunity (2008) 29(1):90–100. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022

9. Shibata K, Yamada H, Nakamura R, Sun X, Itsumi M, Yoshikai Y. Identification of CD25+ gamma delta T cells as fetal thymus-derived naturally occurring IL-17 producers. J Immunol (2008) 181(9):5940–7.

10. Prinz I, Silva-Santos B, Pennington DJ. Functional development of gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol (2013) 43(8):1988–94. doi:10.1002/eji.201343759

11. Carding SR, Allan W, McMickle A, Doherty PC. Activation of cytokine genes in T cells during primary and secondary murine influenza pneumonia. J Exp Med (1993) 177(2):475–82. doi:10.1084/jem.177.2.475

12. Wang T, Scully E, Yin Z, Kim JH, Wang S, Yan J, et al. IFN-gamma-producing gamma delta T cells help control murine West Nile virus infection. J Immunol (2003) 171(5):2524–31.

13. Nishimura H, Yajima T, Kagimoto Y, Ohata M, Watase T, Kishihara K, et al. Intraepithelial gammadelta T cells may bridge a gap between innate immunity and acquired immunity to herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol (2004) 78(9):4927–30. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.9.4927-4930.2004

14. Hiromatsu K, Yoshikai Y, Matsuzaki G, Ohga S, Muramori K, Matsumoto K, et al. A protective role of gamma/delta T cells in primary infection with Listeria monocytogenes in mice. J Exp Med (1992) 175(1):49–56. doi:10.1084/jem.175.1.49

15. Ferrick DA, Schrenzel MD, Mulvania T, Hsieh B, Ferlin WG, Lepper H. Differential production of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in response to Th1- and Th2-stimulating pathogens by gamma delta T cells in vivo. Nature (1995) 373(6511):255–7. doi:10.1038/373255a0

16. Takano M, Nishimura H, Kimura Y, Mokuno Y, Washizu J, Itohara S, et al. Protective roles of gamma delta T cells and interleukin-15 in Escherichia coli infection in mice. Infect Immun (1998) 66(7):3270–8.

17. Zachariadis O, Cassidy JP, Brady J, Mahon BP. Gammadelta T cells regulate the early inflammatory response to Bordetella pertussis infection in the murine respiratory tract. Infect Immun (2006) 74(3):1837–45. doi:10.1128/IAI.74.3.1837-1845.2006

18. Hamada S, Umemura M, Shiono T, Hara H, Kishihara K, Tanaka K, et al. Importance of murine Vdelta1gammadelta T cells expressing interferon-gamma and interleukin-17A in innate protection against Listeria monocytogenes infection. Immunology (2008) 125(2):170–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02841.x

19. Seixas EM, Langhorne J. Gammadelta T cells contribute to control of chronic parasitemia in Plasmodium chabaudi infections in mice. J Immunol (1999) 162(5):2837–41.

20. Lee YH, Shin DW, Kasper LH. Sequential analysis of cell differentials and IFN-gamma production of splenocytes from mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Korean J Parasitol (2000) 38(2):85–90. doi:10.3347/kjp.2000.38.2.85

21. Seixas E, Fonseca L, Langhorne J. The influence of gammadelta T cells on the CD4+ T cell and antibody response during a primary Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection in mice. Parasite Immunol (2002) 24(3):131–40. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3024.2002.00446.x

22. Lee YH, Kasper LH. Immune responses of different mouse strains after challenge with equivalent lethal doses of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasite (2004) 11(1):89–97.

23. Gao Y, Yang W, Pan M, Scully E, Girardi M, Augenlicht LH, et al. Gamma delta T cells provide an early source of interferon gamma in tumor immunity. J Exp Med (2003) 198(3):433–42. doi:10.1084/jem.20030584

24. Lanca T, Costa MF, Goncalves-Sousa N, Rei M, Grosso AR, Penido C, et al. Protective role of the inflammatory CCR2/CCL2 chemokine pathway through recruitment of type 1 cytotoxic gammadelta T lymphocytes to tumor beds. J Immunol (2013) 190(12):6673–80. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300434

25. Lockhart E, Green AM, Flynn JL. IL-17 production is dominated by gammadelta T cells rather than CD4 T cells during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol (2006) 177(7):4662–9.

26. Nakasone C, Yamamoto N, Nakamatsu M, Kinjo T, Miyagi K, Uezu K, et al. Accumulation of gamma/delta T cells in the lungs and their roles in neutrophil-mediated host defense against pneumococcal infection. Microbes Infect (2007) 9(3):251–8. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2006.11.015

27. Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol (2007) 178(7):4466–72.

28. Umemura M, Yahagi A, Hamada S, Begum MD, Watanabe H, Kawakami K, et al. IL-17-mediated regulation of innate and acquired immune response against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. J Immunol (2007) 178(6):3786–96.

29. Simonian PL, Roark CL, Wehrmann F, Lanham AM, Born WK, O’Brien RL, et al. IL-17A-expressing T cells are essential for bacterial clearance in a murine model of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Immunol (2009) 182(10):6540–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900013

30. Cho JS, Pietras EM, Garcia NC, Ramos RI, Farzam DM, Monroe HR, et al. IL-17 is essential for host defense against cutaneous Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. J Clin Invest (2010) 120(5):1762–73. doi:10.1172/JCI40891

31. Dejima T, Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Iwakura Y, Naito S, et al. Protective role of naturally occurring interleukin-17A-producing gammadelta T cells in the lung at the early stage of systemic candidiasis in mice. Infect Immun (2011) 79(11):4503–10. doi:10.1128/IAI.05799-11

32. Hamada S, Umemura M, Shiono T, Tanaka K, Yahagi A, Begum MD, et al. IL-17A produced by gammadelta T cells plays a critical role in innate immunity against Listeria monocytogenes infection in the liver. J Immunol (2008) 181(5):3456–63.

33. Roark CL, French JD, Taylor MA, Bendele AM, Born WK, O’Brien RL. Exacerbation of collagen-induced arthritis by oligoclonal, IL-17-producing gamma delta T cells. J Immunol (2007) 179(8):5576–83.

34. Olive C. Modulation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in mice by immunization with a peptide specific for the gamma delta T cell receptor. Immunol Cell Biol (1997) 75(1):102–6. doi:10.1038/icb.1997.14

35. Spahn TW, Issazadah S, Salvin AJ, Weiner HL. Decreased severity of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide 33 – 35-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice with a disrupted TCR delta chain gene. Eur J Immunol (1999) 29(12):4060–71. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<4060::AID-IMMU4060>3.0.CO;2-S

36. Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Brereton CF, Lavelle EC, Mills KH. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity (2009) 31(2):331–41. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001

37. Wohler JE, Smith SS, Zinn KR, Bullard DC, Barnum SR. Gammadelta T cells in EAE: early trafficking events and cytokine requirements. Eur J Immunol (2009) 39(6):1516–26. doi:10.1002/eji.200839176

38. Petermann F, Rothhammer V, Claussen MC, Haas JD, Blanco LR, Heink S, et al. Gammadelta T cells enhance autoimmunity by restraining regulatory T cell responses via an interleukin-23-dependent mechanism. Immunity (2010) 33(3):351–63. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.013

39. Romani L, Fallarino F, De Luca A, Montagnoli C, D’Angelo C, Zelante T, et al. Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature (2008) 451(7175):211–5. doi:10.1038/nature06471

40. Cui Y, Shao H, Lan C, Nian H, O’Brien RL, Born WK, et al. Major role of gamma delta T cells in the generation of IL-17+ uveitogenic T cells. J Immunol (2009) 183(1):560–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900241

41. Shichita T, Sugiyama Y, Ooboshi H, Sugimori H, Nakagawa R, Takada I, et al. Pivotal role of cerebral interleukin-17-producing gammadeltaT cells in the delayed phase of ischemic brain injury. Nat Med (2009) 15(8):946–50. doi:10.1038/nm.1999

42. Park SG, Mathur R, Long M, Hosh N, Hao L, Hayden MS, et al. T regulatory cells maintain intestinal homeostasis by suppressing gammadelta T cells. Immunity (2010) 33(5):791–803. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.014

43. Do JS, Visperas A, Dong C, Baldwin WM III, Min B. Cutting edge: generation of colitogenic Th17 CD4 T cells is enhanced by IL-17+ gammadelta T cells. J Immunol (2011) 186(8):4546–50. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1004021

44. Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity (2011) 35(4):596–610. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.001

45. Pantelyushin S, Haak S, Ingold B, Kulig P, Heppner FL, Navarini AA, et al. Rorgammat+ innate lymphocytes and gammadelta T cells initiate psoriasiform plaque formation in mice. J Clin Invest (2012) 122(6):2252–6. doi:10.1172/JCI61862

46. Wakita D, Sumida K, Iwakura Y, Nishikawa H, Ohkuri T, Chamoto K, et al. Tumor-infiltrating IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells support the progression of tumor by promoting angiogenesis. Eur J Immunol (2010) 40(7):1927–37. doi:10.1002/eji.200940157

47. Carmi Y, Rinott G, Dotan S, Elkabets M, Rider P, Voronov E, et al. Microenvironment-derived IL-1 and IL-17 interact in the control of lung metastasis. J Immunol (2011) 186(6):3462–71. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1002901

48. Caccamo N, Todaro M, Sireci G, Meraviglia S, Stassi G, Dieli F. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of human gammadelta T cells. Cell Mol Immunol (2013) 10(1):30–4. doi:10.1038/cmi.2012.42

49. Gerber DJ, Azuara V, Levraud JP, Huang SY, Lembezat MP, Pereira P. IL-4-producing gamma delta T cells that express a very restricted TCR repertoire are preferentially localized in liver and spleen. J Immunol (1999) 163(6):3076–82.

50. Grigoriadou K, Boucontet L, Pereira P. Most IL-4-producing gamma delta thymocytes of adult mice originate from fetal precursors. J Immunol (2003) 171(5):2413–20.

51. Strid J, Sobolev O, Zafirova B, Polic B, Hayday A. The intraepithelial T cell response to NKG2D-ligands links lymphoid stress surveillance to atopy. Science (2011) 334(6060):1293–7. doi:10.1126/science.1211250

52. Seo N, Tokura Y, Takigawa M, Egawa K. Depletion of IL-10- and TGF-beta-producing regulatory gamma delta T cells by administering a daunomycin-conjugated specific monoclonal antibody in early tumor lesions augments the activity of CTLs and NK cells. J Immunol (1999) 163(1):242–9.

53. Rhodes KA, Andrew EM, Newton DJ, Tramonti D, Carding SR. A subset of IL-10-producing gammadelta T cells protect the liver from Listeria-elicited, CD8(+) T cell-mediated injury. Eur J Immunol (2008) 38(8):2274–83. doi:10.1002/eji.200838354

54. Martin B, Hirota K, Cua DJ, Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity (2009) 31(2):321–30. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.020

55. Simonian PL, Wehrmann F, Roark CL, Born WK, O’Brien RL, Fontenot AP. Gammadelta T cells protect against lung fibrosis via IL-22. J Exp Med (2010) 207(10):2239–53. doi:10.1084/jem.20100061

56. Mielke LA, Jones SA, Raverdeau M, Higgs R, Stefanska A, Groom JR, et al. Retinoic acid expression associates with enhanced IL-22 production by gammadelta T cells and innate lymphoid cells and attenuation of intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med (2013) 210(6):1117–24. doi:10.1084/jem.20121588

57. Heilig JS, Tonegawa S. Diversity of murine gamma genes and expression in fetal and adult T lymphocytes. Nature (1986) 322(6082):836–40. doi:10.1038/322836a0

58. Turchinovich G, Hayday AC. Skint-1 identifies a common molecular mechanism for the development of interferon-gamma-secreting versus interleukin-17-secreting gammadelta T cells. Immunity (2011) 35(1):59–68. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.018

59. Macleod AS, Hemmers S, Garijo O, Chabod M, Mowen K, Witherden DA, et al. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin antimicrobial barrier function. J Clin Invest (2013) 123(10):4364–74. doi:10.1172/JCI70064

60. Lahn M, Kanehiro A, Takeda K, Joetham A, Schwarze J, Kohler G, et al. Negative regulation of airway responsiveness that is dependent on gammadelta T cells and independent of alphabeta T cells. Nat Med (1999) 5(10):1150–6. doi:10.1038/13476

61. Hahn YS, Taube C, Jin N, Takeda K, Park JW, Wands JM, et al. V gamma 4+ gamma delta T cells regulate airway hyperreactivity to methacholine in ovalbumin-sensitized and challenged mice. J Immunol (2003) 171(6):3170–8.

62. Narayan K, Sylvia KE, Malhotra N, Yin CC, Martens G, Vallerskog T, et al. Intrathymic programming of effector fates in three molecularly distinct gammadelta T cell subtypes. Nat Immunol (2012) 13(5):511–8. doi:10.1038/ni.2247

63. Haas JD, Gonzalez FH, Schmitz S, Chennupati V, Fohse L, Kremmer E, et al. CCR6 and NK1.1 distinguish between IL-17A and IFN-gamma-producing gammadelta effector T cells. Eur J Immunol (2009) 39(12):3488–97. doi:10.1002/eji.200939922

64. Haas JD, Ravens S, Duber S, Chennupati V, Fohse L, Oberdorfer L, et al. IL-17-mediated negative feedback restricts development of IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells to an embryonic wave. Immunity (2012) 37(1):48–59. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.003

65. Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*). Annu Rev Immunol (2010) 28:445–89. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212

66. Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type 1 and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood (1994) 84(12):4008–27.

67. Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature (2006) 441(7090):235–8. doi:10.1038/nature04753

68. Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature (2006) 441(7090):231–4. doi:10.1038/nature04754

69. Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity (2006) 24(2):179–89. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001

70. Lochner M, Peduto L, Cherrier M, Sawa S, Langa F, Varona R, et al. In vivo equilibrium of proinflammatory IL-17+ and regulatory IL-10+ Foxp3+ RORgamma t+ T cells. J Exp Med (2008) 205(6):1381–93. doi:10.1084/jem.20080034

71. Do JS, Fink PJ, Li L, Spolski R, Robinson J, Leonard WJ, et al. Cutting edge: spontaneous development of IL-17-producing gamma delta T cells in the thymus occurs via a TGF-beta 1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol (2010) 184(4):1675–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0903539

72. Riol-Blanco L, Lazarevic V, Awasthi A, Mitsdoerffer M, Wilson BS, Croxford A, et al. IL-23 receptor regulates unconventional IL-17-producing T cells that control bacterial infections. J Immunol (2010) 184(4):1710–20. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0902796

73. Hayes SM, Laird RM. Genetic requirements for the development and differentiation of interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Crit Rev Immunol (2012) 32(1):81–95. doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i1.50

74. Michel ML, Pang DJ, Haque SF, Potocnik AJ, Pennington DJ, Hayday AC. Interleukin 7 (IL-7) selectively promotes mouse and human IL-17-producing gammadelta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109(43):17549–54. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204327109

75. Duan J, Chung H, Troy E, Kasper DL. Microbial colonization drives expansion of IL-1 receptor 1-expressing and IL-17-producing gamma/delta T cells. Cell Host Microbe (2010) 7(2):140–50. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.005

76. Ribot JC, Chaves-Ferreira M, d’Orey F, Wencker M, Goncalves-Sousa N, Decalf J, et al. Cutting edge: adaptive versus innate receptor signals selectively control the pool sizes of murine IFN-gamma- or IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells upon infection. J Immunol (2010) 185(11):6421–5. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1002283

77. Meeks KD, Sieve AN, Kolls JK, Ghilardi N, Berg RE. IL-23 is required for protection against systemic infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol (2009) 183(12):8026–34. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901588

78. Lalor SJ, Dungan LS, Sutton CE, Basdeo SA, Fletcher JM, Mills KH. Caspase-1-processed cytokines IL-1beta and IL-18 promote IL-17 production by gammadelta and CD4 T cells that mediate autoimmunity. J Immunol (2011) 186(10):5738–48. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003597

79. Zeng X, Wei YL, Huang J, Newell EW, Yu H, Kidd BA, et al. Gammadelta T cells recognize a microbial encoded B cell antigen to initiate a rapid antigen-specific interleukin-17 response. Immunity (2012) 37(3):524–34. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.011

80. Bacon CM, Petricoin EF III, Ortaldo JR, Rees RC, Larner AC, Johnston JA, et al. Interleukin 12 induces tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT4 in human lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1995) 92(16):7307–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.16.7307

81. Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell (2000) 100(6):655–69. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80702-3

82. Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science (2002) 295(5553):338–42. doi:10.1126/science.1065543

83. Yin Z, Chen C, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Ray A, Craft J. T-bet expression and failure of GATA-3 cross-regulation lead to default production of IFN-gamma by gammadelta T cells. J Immunol (2002) 168(4):1566–71.

84. Chen L, He W, Kim ST, Tao J, Gao Y, Chi H, et al. Epigenetic and transcriptional programs lead to default IFN-gamma production by gammadelta T cells. J Immunol (2007) 178(5):2730–6.

85. Schmolka N, Serre K, Grosso AR, Rei M, Pennington DJ, Gomes AQ, et al. Epigenetic and transcriptional signatures of stable versus plastic differentiation of proinflammatory gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat Immunol (2013) 14(10):1093–100. doi:10.1038/ni.2702

86. Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell (2006) 126(6):1121–33. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035

87. Yang XO, Pappu BP, Nurieva R, Akimzhanov A, Kang HS, Chung Y, et al. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity (2008) 28(1):29–39. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.016

88. Brustle A, Heink S, Huber M, Rosenplanter C, Stadelmann C, Yu P, et al. The development of inflammatory T(H)-17 cells requires interferon-regulatory factor 4. Nat Immunol (2007) 8(9):958–66. doi:10.1038/ni1500

89. Schraml BU, Hildner K, Ise W, Lee WL, Smith WA, Solomon B, et al. The AP-1 transcription factor Batf controls T(H)17 differentiation. Nature (2009) 460(7253):405–9. doi:10.1038/nature08114

90. Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature (2008) 453(7191):106–9. doi:10.1038/nature06881

91. Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Christensen J, O’Garra A, Stockinger B. Natural agonists for aryl hydrocarbon receptor in culture medium are essential for optimal differentiation of Th17 T cells. J Exp Med (2009) 206(1):43–9. doi:10.1084/jem.20081438

92. Ciofani M, Madar A, Galan C, Sellars M, Mace K, Pauli F, et al. A validated regulatory network for Th17 cell specification. Cell (2012) 151(2):289–303. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.016

93. Shibata K, Yamada H, Sato T, Dejima T, Nakamura M, Ikawa T, et al. Notch-Hes1 pathway is required for the development of IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Blood (2011) 118(3):586–93. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-334995

94. Raifer H, Mahiny AJ, Bollig N, Petermann F, Hellhund A, Kellner K, et al. Unlike alphabeta T cells, gammadelta T cells, LTi cells and NKT cells do not require IRF4 for the production of IL-17A and IL-22. Eur J Immunol (2012) 42(12):3189–201. doi:10.1002/eji.201142155

95. Gray EE, Ramirez-Valle F, Xu Y, Wu S, Wu Z, Karjalainen KE, et al. Deficiency in IL-17-committed Vgamma4(+) gammadelta T cells in a spontaneous Sox13-mutant CD45.1(+) congenic mouse substrain provides protection from dermatitis. Nat Immunol (2013) 14(6):584–92. doi:10.1038/ni.2585

96. Malhotra N, Narayan K, Cho OH, Sylvia KE, Yin C, Melichar H, et al. A network of high-mobility group box transcription factors programs innate interleukin-17 production. Immunity (2013) 38(4):681–93. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.010

97. Powolny-Budnicka I, Riemann M, Tanzer S, Schmid RM, Hehlgans T, Weih F. RelA and RelB transcription factors in distinct thymocyte populations control lymphotoxin-dependent interleukin-17 production in gammadelta T cells. Immunity (2011) 34(3):364–74. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.019

98. Jojic V, Shay T, Sylvia K, Zuk O, Sun X, Kang J, et al. Identification of transcriptional regulators in the mouse immune system. Nat Immunol (2013) 14(6):633–43. doi:10.1038/ni.2587

99. Laird RM, Laky K, Hayes SM. Unexpected role for the B cell-specific Src family kinase B lymphoid kinase in the development of IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. J Immunol (2010) 185(11):6518–27. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1002766

100. Coomes SM, Pelly VS, Wilson MS. Plasticity within the alphabeta(+)CD4(+) T-cell lineage: when, how and what for? Open Biol (2013) 3(1):120157. doi:10.1098/rsob.120157

101. Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell (2007) 128(4):707–19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015

102. Zhou VW, Goren A, Bernstein BE. Charting histone modifications and the functional organization of mammalian genomes. Nat Rev Genet (2011) 12(1):7–18. doi:10.1038/nrg2905

103. Reynolds JM, Martinez GJ, Chung Y, Dong C. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in T cells promotes autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109(32):13064–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120585109

104. Sheridan BS, Romagnoli PA, Pham QM, Fu HH, Alonzo F III, Schubert WD, et al. Gammadelta T cells exhibit multifunctional and protective memory in intestinal tissues. Immunity (2013) 39(1):184–95. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.015

105. Ness-Schwickerath KJ, Jin C, Morita CT. Cytokine requirements for the differentiation and expansion of IL-17A- and IL-22-producing human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells. J Immunol (2010) 184(12):7268–80. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1000600

106. Fenoglio D, Poggi A, Catellani S, Battaglia F, Ferrera A, Setti M, et al. Vdelta1 T lymphocytes producing IFN-gamma and IL-17 are expanded in HIV-1-infected patients and respond to Candida albicans. Blood (2009) 113(26):6611–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-01-198028

107. Bending D, De la Pena H, Veldhoen M, Phillips JM, Uyttenhove C, Stockinger B, et al. Highly purified Th17 cells from BDC2.5NOD mice convert into Th1-like cells in NOD/SCID recipient mice. J Clin Invest (2009) 119(3):565–72. doi:10.1172/JCI37865

108. Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, Oliver JR, Chen D, Elson CO, et al. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity (2009) 30(1):92–107. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005

109. Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, Jarrossay D, Gattorno M, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol (2007) 8(6):639–46. doi:10.1038/ni1467

110. Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Santarlasci V, Maggi L, Liotta F, Mazzinghi B, et al. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J Exp Med (2007) 204(8):1849–61. doi:10.1084/jem.20070663

111. Boniface K, Blumenschein WM, Brovont-Porth K, McGeachy MJ, Basham B, Desai B, et al. Human Th17 cells comprise heterogeneous subsets including IFN-gamma-producing cells with distinct properties from the Th1 lineage. J Immunol (2010) 185(1):679–87. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1000366

112. Hirota K, Duarte JH, Veldhoen M, Hornsby E, Li Y, Cua DJ, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol (2011) 12(3):255–63. doi:10.1038/ni.1993

113. Muranski P, Borman ZA, Kerkar SP, Klebanoff CA, Ji Y, Sanchez-Perez L, et al. Th17 cells are long lived and retain a stem cell-like molecular signature. Immunity (2011) 35(6):972–85. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.019

114. Hamai A, Pignon P, Raimbaud I, Duperrier-Amouriaux K, Senellart H, Hiret S, et al. Human T(H)17 immune cells specific for the tumor antigen MAGE-A3 convert to IFN-gamma-secreting cells as they differentiate into effector T cells in vivo. Cancer Res (2012) 72(5):1059–63. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3432

115. Yang Y, Weiner J, Liu Y, Smith AJ, Huss DJ, Winger R, et al. T-bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. J Exp Med (2009) 206(7):1549–64. doi:10.1084/jem.20082584

116. Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, Quintana FJ, Xiao S, Peters A, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol (2012) 13(10):991–9. doi:10.1038/ni.2416

117. Duhen R, Glatigny S, Arbelaez CA, Blair TC, Oukka M, Bettelli E. Cutting edge: the pathogenicity of IFN-gamma-producing Th17 cells is independent of T-bet. J Immunol (2013) 190(9):4478–82. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1203172

Keywords: γδ T cells, T cell differentiation, interleukin-17, interferon-γ, transcription factors, cytokines

Citation: Serre K and Silva-Santos B (2013) Molecular mechanisms of differentiation of murine pro-inflammatory γδ T cell subsets. Front. Immunol. 4:431. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00431

Received: 31 October 2013; Paper pending published: 11 November 2013;

Accepted: 21 November 2013; Published online: 05 December 2013.

Edited by:

Francesco Dieli, University of Palermo, ItalyReviewed by:

Matthias Eberl, Cardiff University, UKJulie Marie Jameson, California State University San Marcos, USA

Copyright: © 2013 Serre and Silva-Santos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karine Serre and Bruno Silva-Santos, Faculdade de Medicina, Instituto de Medicina Molecular, Universidade de Lisboa, Avenida Professor Egas Moniz, Lisboa 1649-028, Portugal e-mail:a2FyaW5lQGtzZXJyZS5uZXQ=;YnNzYW50b3NAZm0udWwucHQ=

Karine Serre

Karine Serre Bruno Silva-Santos

Bruno Silva-Santos