- 1Advanced Technology Innovation Center for Future Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 3State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 4Department of Psychology and Social Behavior, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA

Behavioral studies have reported that males perform better than females in 3-dimensional (3D) mental rotation. Given the important role of the hippocampus in spatial processing, the present study investigated whether structural differences in the hippocampus could explain the sex difference in 3D mental rotation. Results showed that after controlling for brain size, males had a larger anterior hippocampus, whereas females had a larger posterior hippocampus. Gray matter volume (GMV) of the right anterior hippocampus was significantly correlated with 3D mental rotation score. After controlling GMV of the right anterior hippocampus, sex difference in 3D mental rotation was no longer significant. These results suggest that the structural difference between males’ and females’ right anterior hippocampus was a neurobiological substrate for the sex difference in 3D mental rotation.

Introduction

The hippocampus plays an important role in spatial processing. The “place cells” in the hippocampus are the core part in the “GPS” of the brain that processes spatial information (O’Keefe, 1976; Fyhn et al., 2004; Sargolini et al., 2006). Both animal and human studies have shown that the hippocampal volume is related to spatial ability. For example, homing pigeons have larger hippocampi than non-homing pigeons (Rehkämper et al., 1988). The birds that need to store their food have larger hippocampi than the ones who do not (Krebs et al., 1989; Sherry et al., 1989). In terms of the mammals, the rats that store their food in a distributed manner have larger hippocampi than the ones that store their food in one central location (Jacobs and Spencer, 1994).

Human studies also showed that the hippocampus plays an important role in spatial processing (for a recent summary see Lee et al., 2012). First, patients who suffered from developmental topographical disorders (DTD) have damages to the hippocampus (in addition to the retrosplenial cortex, fusiform gyrus, and lingual gyrus) and show impaired performance on navigation tasks (Aguirre and D’Esposito, 1999; Iaria and Barton, 2010). Damages to the hippocampus also result in a deficit in spatial working memory (Abrahams et al., 1997; Bohbot et al., 1998; Holdstock et al., 2000). Second, neuroimaging studies found that the hippocampus is activated by navigation tasks (Maguire et al., 1998; Mellet et al., 2000; Hartley et al., 2003; Iaria et al., 2003, 2008) and spatial memory tasks (Maguire, 1997; Burgess et al., 2002). Moreover, when performing the spatial memory task, only spatial strategies (but not non-spatial strategies) elicited activation in the hippocampus (Iaria et al., 2003; Bohbot et al., 2004). Third, the size of the hippocampus may change dynamically due to a long-term or sustained demand of spatial processing. Experienced taxi drivers have larger posterior hippocampi than the control subjects (Maguire et al., 2000). Spatial navigation training has been found to increase the gray matter of the hippocampus (Lövdén et al., 2010, 2012; Kühn and Gallinat, 2014; Kühn et al., 2014).

Neuroimaging studies have further shown differentiated functions of the anterior and posterior hippocampus (Chua et al., 2007; Ghetti et al., 2010; DeMaster and Ghetti, 2013). Based on the results of 54 previous studies, Lepage et al. (1998) proposed the Hippocampus Encoding/Retrieval (HIPER) Model that specifies the anterior hippocampus’s role in acquiring or encoding new visuospatial information and the posterior hippocampus’s role in retrieval. Subsequent studies have further supported this model (Strange and Dolan, 2001; Hartley et al., 2003; Kumaran and Maguire, 2005; Maguire et al., 2006a; Iaria et al., 2007). Most of the previous studies had focused on spatial memory and have thus implicated the posterior hippocampus for such a function. For example, the “place cells” were found only in the posterior hippocampus in monkeys (Colombo et al., 1998). Taxi drivers’ constant retrieval of city maps can lead to increased gray matter volume (GMV) of the posterior hippocampus (Woollett and Maguire, 2011).

If the hippocampus plays a crucial role in visuospatial processing (in particular, the anterior hippocampus’s role in spatial information encoding), would its structural variations explain one of the most well-documented sex differences—that in visuospatial processing? Decades of behavioral research have shown that sex differences in visuospatial ability are stable across different age groups (Voyer et al., 1995) and that males’ advantage is particularly obvious in mental rotation (Linn and Petersen, 1985; Maeda and Yoon, 2013; Reilly and Neumann, 2013; Lütke and Lange-Küttner, 2015). Moreover, compared to 2-dimensional (2D) mental rotation, 3-dimensional (3D) mental rotation (which requires more spatial processing) has a larger and more consistent sex effect across age groups (Peters et al., 1995; Roberts and Bell, 2003; for a meta-analysis, see Linn and Petersen, 1985). Overall, sex differences are robust based on large-scale studies (e.g., 109,612 men and 88,509 women in Maylor et al., 2007, study; 90,000 women and 111,000 men in Lippa et al., 2010 study) and meta-analysis studies (Geiser et al., 2008; Maeda and Yoon, 2013; Reilly and Neumann, 2013). These sex differences are so robust that only special experimental designs (e.g., positive instructions to women, different delivery modes) or training would reduce or sometimes eliminate them (Goldstein et al., 1990; Peters et al., 1995; Roberts and Bell, 2003; Peters, 2005; Feng et al., 2007; Monahan et al., 2008; Moè, 2009; Glück and Fabrizii, 2010; Tzuriel and Egozi, 2010; Maeda and Yoon, 2013).

In support of a possible neural basis of sex differences in mental rotation, especially, 3D mental rotation, neuroimaging studies have found structural and functional differences between male and female hippocampi. Structurally, the total volume of the hippocampus was larger for females than for males (Giedd et al., 1997; Goldstein et al., 2001). Males showed a significant correlation between the size of the hippocampus and age (from 18 years to 42 years), which was not significant for females (Pruessner et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2005), suggesting that the growth of the hippocampus occurred earlier in females (Giedd et al., 1997). Functionally, when performing a navigation task, males have been found to depend more on the hippocampus, whereas females depend more on the parietal and frontal lobes (Grön et al., 2000). Thus far, however, no study has examined whether structural differences in the hippocampus would account for sex differences in 3D mental rotation.

In the current study, we examined the relationship between GMV of the hippocampus (especially its anterior part) and sex differences in 3D mental rotation. The anterior part is particularly relevant because mental rotation tasks mainly involve the encoding of spatial information, rather than the retrieval of previously stored spatial information. We hypothesized that males would have larger volumes in the anterior hippocampus than would females, and such a difference would explain a large part of sex differences in 3D mental rotation.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 431 college students (192 males and 239 females, mean age = 19.9 years, ranging from 18 to 24 years) from Beijing Normal University. No participants had a history of neurological or psychiatric disorders or head injury. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Imaging Center for Brain Research in the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning at Beijing Normal University.

MRI Acquisition

Whole brain structural MRI scans were performed on a Siemens 3T Trio scanner (Munich, Germany) by using a T1-weighted three-dimensional gradient echo sequence (TR = 2350 ms, TE = 3.39 ms; flip angle = 7°; field of view = 100 mm; matrix = 256 × 256; voxel size = 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm).

Behavioral Tasks

The three-dimensional mental rotation task was based on Shepard’s mental rotation task (Shepard and Metzler, 1971; Peters et al., 1995). Participants were presented one 3D picture as the target and four as answer choices, and they were asked to select the answer that matched the target after rotation. This task had 24 items, which were divided into two 3-min blocks. The total score was analyzed.

Motor-Free Visual Perception Test, Third Edition (MVPT-3) was used to test the general visual perception ability (Colarusso and Hammill, 1972). Five categories of visual perception were measured: spatial relationship, visual closure, visual discrimination, visual memory and figure ground. Total score was analyzed. This task was used to control the general visual perception ability.

Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM; Raven and Court, 1998) was used to assess general intelligence. Subjects were given 30 min to complete as many items as possible. For each test item, subjects were asked to select from several alternatives of the missing segment that would complete a larger pattern. The number of correct trials was analyzed.

Data Analysis

Structural Whole Brain Analysis

Data were analyzed by using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) implemented in Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology) and executed in MATLAB (R2012b, Mathworks, Sherborn, MA, USA). Following the procedures described by Ashburner and Friston (2000) and Good et al. (2001), we conducted the following steps of data pre-processing: extraction of the brain, spatial normalization into the stereotactic space by using the standard SPM gray template, segmentation into gray and white matter and CSF compartments, and correction for volume changes induced by spatial normalization (modulation). The spatially normalized images were written in voxels of 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm. The smoothing with a 12 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel was applied. In the current study, the GMV was analyzed. Two-sample t-test was used to investigate sex differences in GMV of the hippocampus.

Structural ROI Analysis

The current study focused only on the hippocampus arch, which can be divided into three parts: anterior, middle and posterior hippocampus. This segmentation method has been commonly used to study the different parts of hippocampus arch (Huang et al., 2013; Travis et al., 2014; for a review see Malykhin and Coupland, 2015). The segmentation process was executed in MATLAB (Mathworks, Sherborn, MA, USA). A sagittal view of the hippocampus from Anatomical Automatic Labeling (AAL) was projected onto a plane and the maximum values in the right-left direction and the top-down direction were calculated. After marking the hippocampus into four quarters, it was divided into the anterior, middle, and posterior parts, with the ratios of 1:2:1 (Duvernoy, 2005), which were then used as the mask for structural ROI analysis. To control for sex differences in overall brain size, the whole brain GMV was used as a covariate. A separate analysis was conducted without controlling for the whole brain GMV (see Supplementary Material).

Statistical analysis of the behavioral data was conducted in SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Behavioral Results

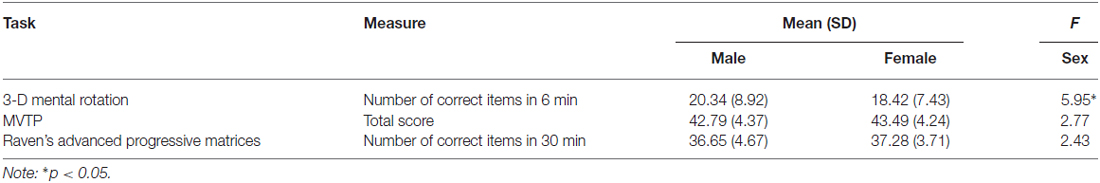

The behavioral tasks showed that males performed better than females on the 3D mental rotation task (F(1,429) = 5.95, p = 0.015, d = 0.234). This sex difference became even slightly greater (F(1,427) = 7.65, p = 0.006, d = 0.254), after controlling for general visual perception and intelligence (RAPM) even though these two correlates did not show significant sex differences (for visual perception, F(1,429) = 2.77, p = 0.097; and for RAPM, F(1,429) = 2.43, p = 0.120; see Table 1).

Structural ROI Analysis

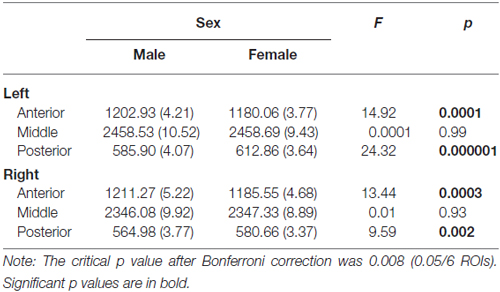

The structural ROI analysis involved six brain areas (bilateral anterior, middle and posterior hippocampus), so we used Bonferroni correction to adjust for the significance thresholds: p = 0.05/6 = 0.008. Controlling for the whole brain GMV, the GMV of the anterior hippocampus was significantly larger for males than for females (F(1,428) = 14.92, p < 0.008, for the left hemisphere, and F(1,428) = 13.44, p < 0.008, for the right hemisphere), whereas the posterior hippocampus was significantly larger for females than males (F(1,428) = 24.32, p < 0.008, for the left hemisphere, and F(1,428) = 9.59, p < 0.008, for the right hemisphere; see Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1S). There was no significant sex difference in GMV of the middle hippocampus (F(1,428) = 0.001, n.s., for the left hemisphere; F(1,428) = 0.01, n.s., for the right hemisphere). After controlling for the whole brain GMV, there also were no significant sex differences in GMV of the whole left hippocampus (F(1,428) = 0.07, n.s.) and the whole right hippocampus (F(1,428) = 0.19, n.s.).

Table 2. Mean scores (and standard error) and sex differences in gray matter volumes (mm3) of the left and right anterior, middle and posterior hippocampus (with the gray matter volume of the whole brain as a covariate).

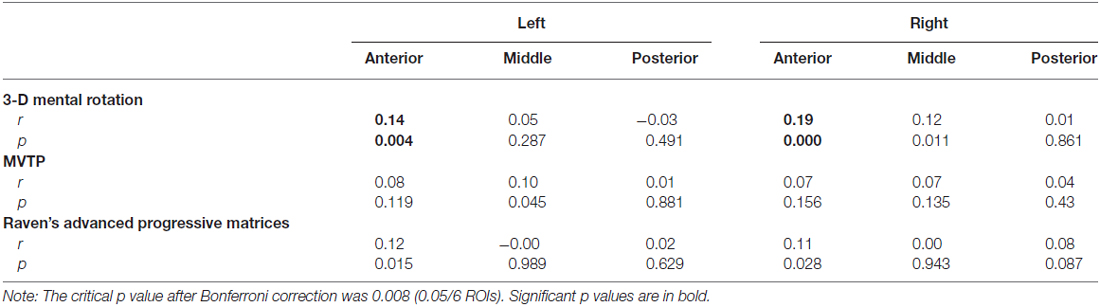

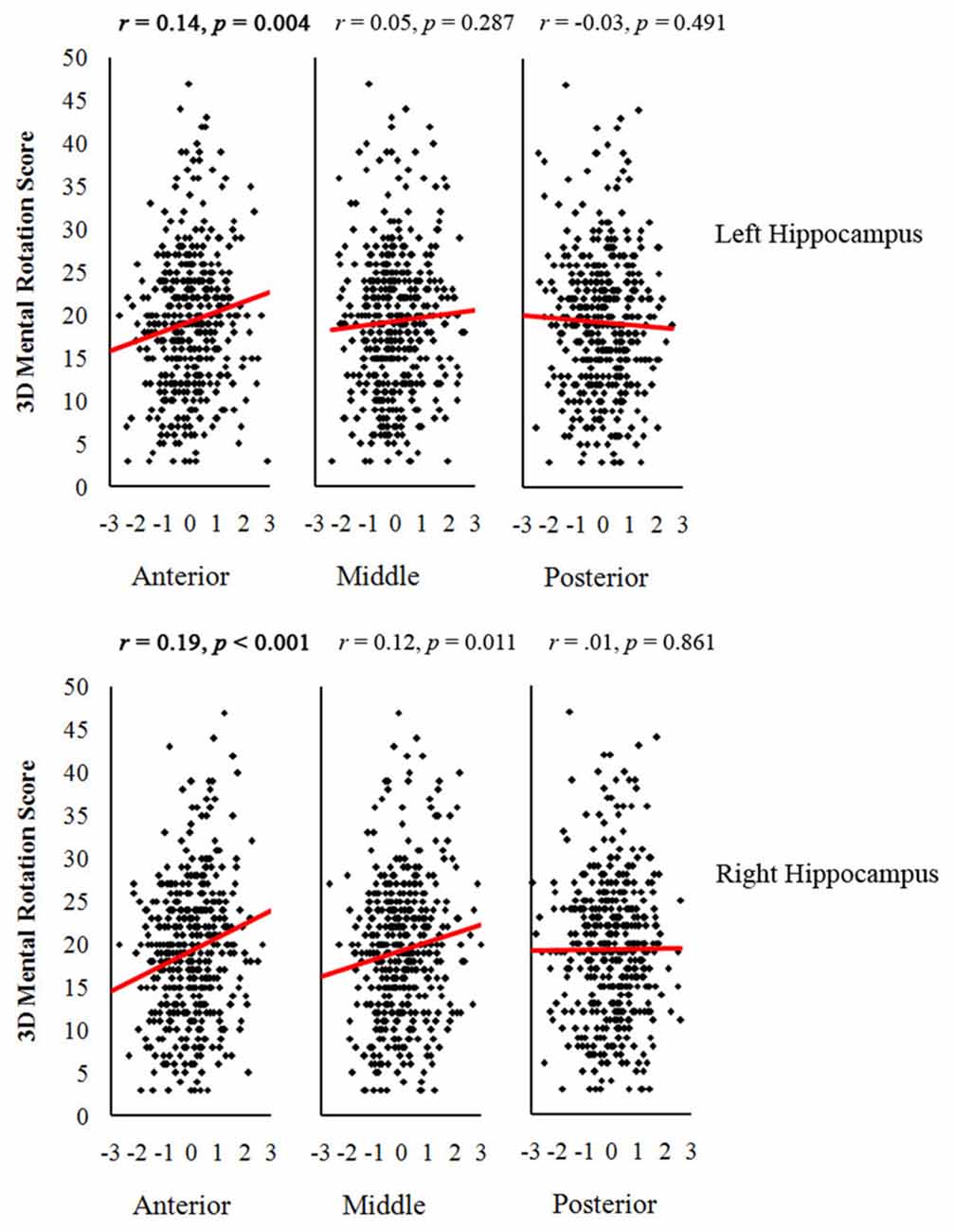

Table 3 shows the correlations between GMVs of the different parts of the hippocampus and the scores of 3D mental rotation and the other two cognitive tasks after controlling for the whole brain GMV (see Supplementary Table 2S). The results showed that GMVs of the left and right anterior hippocampus were significantly correlated with performance on the 3D mental rotation task (left, r = 0.14, p < 0.008; right, r = 0.19, p < 0.008; see Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1S). After controlling for visual perception, the correlations between 3D mental rotation and the GMVs of the left and right anterior hippocampus remained significant (left, r = 0.14, p < 0.008; right, r = 0.19, p < 0.008). After controlling for intelligence, the correlation between 3D mental rotation and the GMVs of the right anterior hippocampus remained significant (right, r = 0.17, p < 0.008). After controlling for both visual perception and intelligence, the correlation between 3D mental rotation and the GMV of the right anterior hippocampus also remained significant (right, r = 0.18, p < 0.008). The correlations between mental rotation and the GMV of the left anterior hippocampus (r = 0.12, controlling for either intelligence alone or both intelligence and visual perception) were no longer significant after Bonferroni correction.

Table 3. Correlation coefficients between gray matter volumes of the left and right hippocampus and behavioral performance (with the gray matter volume of the whole brain as a covariate).

Figure 1. Scatter plots between gray matter volumes (GMV) of anterior, middle and posterior hippocampus and 3-dimensional (3D) mental rotation performance (with the GMV of the whole brain as a covariate). The critical p value after Bonferroni correction was 0.008 (0.05/6 ROIs). Significant p values are in bold.

ANCOVA was conducted to test whether the sex difference in 3D mental rotation could be explained by sex differences in GMVs of the hippocampus. After controlling for GMVs of the right anterior hippocampus and the whole brain, the sex difference in 3D mental rotation was no longer significant (F(1,427) = 3.04, p = 0.070). The change in sex difference was statistically significant (t = 3.47, p < 0.01).

Whole-Brain Analysis

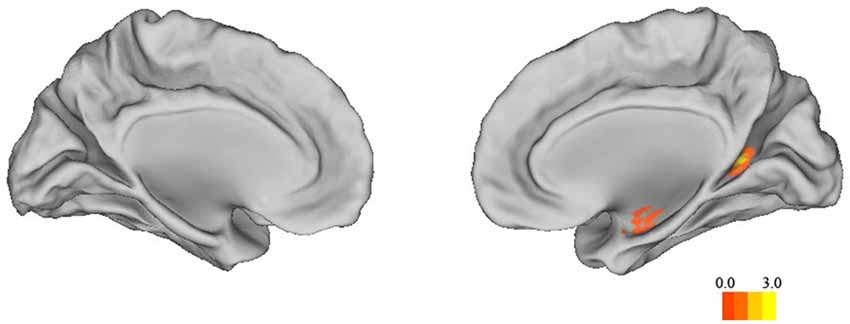

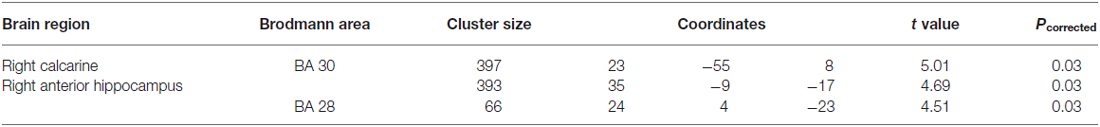

To supplement the structural ROI analysis, we conducted a whole-brain analysis in SPM. Sex differences in the whole brain GMV are shown in Table 4. Correlation analysis confirmed that the structure of left and right anterior hippocampus was correlated with 3D mental rotation (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected for multiple comparison, peak, left: x = −34, y = −9, z = −19, t = 3.80; right: x = 35, y = −9, z = −17, t = 4.69; see Figure 2). In addition, GMV in the calcarine was significantly and positively associated with 3D mental rotation (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected for multiple comparison, cluster size >50; Table 5).

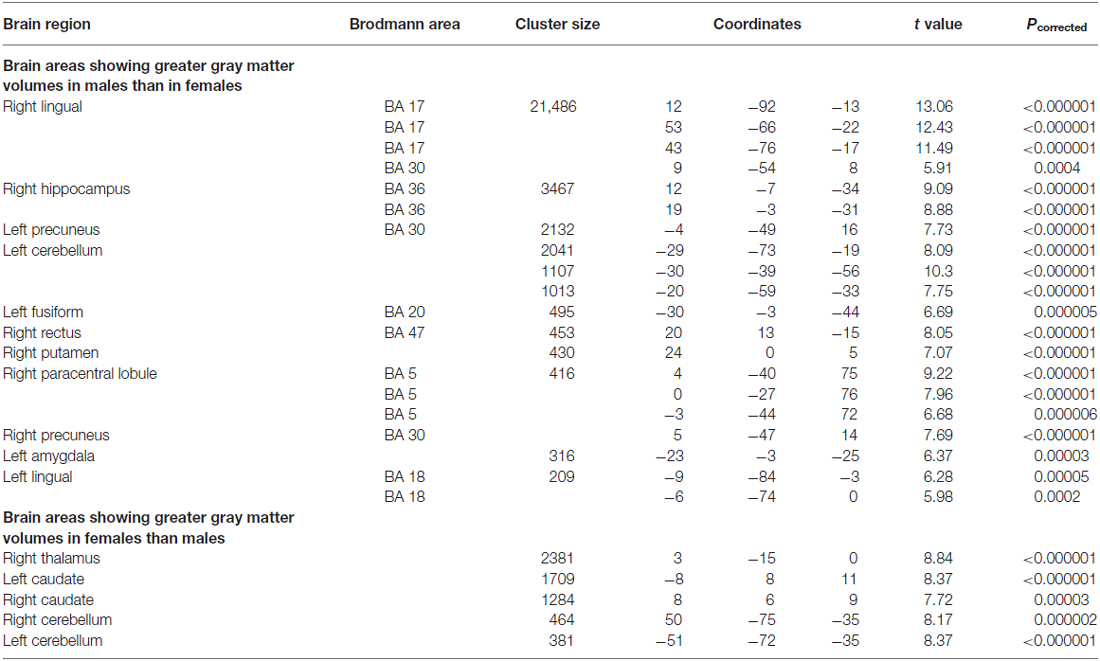

Table 4. Loci showing significant sex differences in gray matter volume based on the whole brain analysis (p < 0.001, FWE-corrected for multiple comparisons, cluster size >200).

Figure 2. The correlation map between 3D mental rotation performance and GMV of the whole brain (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected for multiple comparisons, cluster size >50).

Table 5. Loci showing positive correlations between 3-dimensional (3D) mental rotation and gray matter volumes based on the whole brain analysis (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected for multiple comparisons, cluster size >50).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that, compared to females, males performed better in 3D mental rotation and had greater GMV in the anterior hippocampus. The GMV of the right anterior hippocampus was significantly correlated with 3D mental rotation performance, even after controlling for visual perception and general intelligence. The sex difference in 3D mental rotation disappeared after controlling for GMV of the right anterior hippocampus.

Sex Differences in Spatial Abilities

Our behavioral results were consistent with many previous studies that showed a stable male advantage in spatial ability, especially in 3D mental rotation. This male advantage may have had an evolutionary origin because of males’ role in hunting, for which a good sense of direction and a superior ability in spatial relations (throwing spears at the games) had been critical (Geary, 1995; Ecuyer-Dab and Robert, 2004). In modern-day life, males may no longer need to hunt, but they still prefer activities involving spatial processing such video games and sports (Okagaki and Frensch, 1994; Ozel et al., 2004; Robert and Héroux, 2004; Cherney and London, 2006), which may have continued to help males gain an advantage in spatial ability. Males and females have also been found to use different strategies when performing a navigation task, with males using spatial strategies and females using both verbal and spatial strategies (Merrill et al., 2016).

It is worth mentioning that, although Raven’s Progressive Matrices test also involves spatial processing and mental rotation, it did not show sex differences in our study. This result is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Raven, 1938; Eysenck and Kamin, 1981; Wei et al., 2012; Lütke and Lange-Küttner, 2015). There are at least two possible reasons. First, Raven’s Progressive Matrices aims to test general intelligence, so it includes measures of both visuospatial ability and reasoning. Using structural equation modeling, Schweizer et al. (2007) showed that the component of reasoning explained 46% of the variance of the total score, whereas mental rotation explained only 7% (Schweizer et al., 2007). Second, Raven’s mental rotation task involves only 2D rotation, which has smaller sex differences than 3D rotation (Peters et al., 1995; Roberts and Bell, 2003; Lütke and Lange-Küttner, 2015).

Neural Basis of Sex Differences in Spatial Abilities

Sex difference in spatial processing has been associated with the volume and activation of the hippocampus. In nonhuman animals, the sex that is responsible for searching for food and nesting has a larger hippocampus (Clayton et al., 1997, and for a review see Lee et al., 1998). Our results showed that compared to females, males had a larger anterior hippocampus, which accounted for their advantage in 3D mental rotation. Consistently, previous research has linked a larger anterior hippocampus to better performance in encoding new spatial information (Maguire et al., 2006b). Our results on the role of the anterior hippocampus in mental rotation are consistent with the HIPER model (Lepage et al., 1998). According to this model, the anterior hippocampus is responsible for acquiring or encoding new visuospatial information, more specifically, coding information for head directions and angular features (Maguire et al., 1998), and registering new and abstract spatial environment (Save et al., 1992; Hartley et al., 2003; Sperling et al., 2003; Jackson and Schacter, 2004; Maguire et al., 2006b; Chua et al., 2007; Iaria et al., 2007; Doeller et al., 2008). Functional MRI studies also found that imagination tasks activated anterior hippocampus more than did memory tasks (Addis et al., 2007, 2009). The 3D mental rotation task seems to meet the requirements of this particular type of spatial information processing because it involves head directions and angular features and the 3D figures were likely to be new and abstract to the participants. Therefore, it seems likely that the anterior hippocampus subserves 3D mental rotation as tested in our project. Furthermore, it was the right anterior hippocampus that had a high correlation with 3D mental rotation after controlling for covariates. Consistent with such hemispheric specialization, previous fMRI studies have found that navigation tasks activate the right anterior hippocampus (Maguire et al., 1998; Mellet et al., 2000; Iaria et al., 2003, 2009; Doeller et al., 2008) and lesion studies have found that damages to the right anterior hippocampus impair spatial memory while damages to the left anterior hippocampus impair verbal memory (Abrahams et al., 1997; Bohbot et al., 1998). In sum, structural differences between males and females in the right anterior hippocampus seem to explain sex differences in 3D mental rotation.

Interestingly, the sex difference in the posterior hippocampus was opposite of that in the anterior hippocampus. Consequently, the whole hippocampus did not show sex difference in GMV. Some of the previous studies, however, have shown sex difference in the total GMV of the hippocampus (Giedd et al., 1997; Goldstein et al., 2001). One possible reason is age differences between studies. Goldstein et al. (2001) found that females in their 30 s (mean = 36.3 years of age) showed a larger hippocampus than their male counterparts and Pruessner et al. (2001) found that males in their 30 s began to show a decrease in their hippocampus. Our participants were all college students. Indeed previous studies found sex differences in developmental trajectories of the size of the hippocampus (Giedd et al., 1997; Pruessner et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2005).

It should be mentioned that, although our study focused on the hippocampus’s role in 3D mental rotation, our whole-brain analysis also found that the right calcarine was associated with 3D mental rotation. The calcarine sulcus is an important part of the primary visual cortex (V1; Sereno et al., 1995), which is important for all types of visual processing, but its specific role in 3D mental rotation needs further research. In addition to these two regions, previous studies found that mental rotation also elicited activation in other brain regions, but with mixed results on sex differences. One study found that males activated the frontal gyrus, cingulate cortex and occipital gyrus more than did females (Semrud-Clikeman et al., 2012), whereas another study found that females activated the middle temporal gyrus, frontal gyrus and primary motor cortex more than did males (Kucian et al., 2005). These cross-study differences in other brain regions may have been due to different levels of difficulty of the tasks (Roberts and Bell, 2003) or the particular paradigms used in different studies. Previous studies also found that the parietal lobe, rather than the hippocampus, had the highest correlation with spatial ability (Corbetta et al., 2000; Koscik et al., 2009; Hänggi et al., 2010). There are three possible explanations. First, the hippocampus is involved during the early brief stage of the spatial tasks (Iaria et al., 2003; Etchamendy et al., 2012), and thus its activation may be overshadowed by later stages of processing. Event-related potentials (ERP) studies also showed a late posterior negativity related to mental rotation tasks (Peronnet and Farah, 1989; Heil, 2002). Second, there are sex differences in neural bases of spatial processing, which might have complicated previous findings: males depend more on the hippocampus for spatial processing, whereas females depend more on the parietal and frontal lobes (Grön et al., 2000). Third, as mentioned earlier, task differences (using spatial or verbal strategies) affect the involvement of the hippocampus (Iaria et al., 2003; Bohbot et al., 2004).

Finally, although this study found significant sex differences in 3D mental rotation which could be accounted for by structural differences in the right anterior hippocampus, we should recognize that the brain is plastic and the structure of the hippocampus could be changed through training (Lövdén et al., 2010; Kühn and Gallinat, 2014; Kühn et al., 2014), even in the case of the aging brain (Kempermann et al., 1998; Maguire et al., 2000, 2006a; Lövdén et al., 2012). Training has been found to improve spatial ability (Sanchez, 2012; Sorby et al., 2013) and reduce or eliminate its sex difference (Terlecki and Newcombe, 2005; Feng et al., 2007; Spence et al., 2009; Tzuriel and Egozi, 2010). In addition, some researchers have also found that the GMV of females’ posterior hippocampus changes with menstrual cycle, showing increases from the early follicular phase to the late follicular phase (Lisofsky et al., 2015). Such an influence should be considered in future research of sex differences in the hippocampus, especially the posterior hippocampus.

Author Contributions

CC, QD and XZ designed the study. WW analyzed the data. WW, CC and XZ wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (no. 2014CB846100), two grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31521063 and 31271187), a grant from Advanced Technology Innovation Center for Future Education, Beijing Normal University, and the 111 Project (B07008). We thank Chunhui Chen, Qinghua He, Jin Li, Mingxia Zhang, Bi Zhu, Xuemei Lei, and many others for helping collect the data.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00580/full#supplementary-material

References

Abrahams, S., Pickering, A., Polkey, C. G., and Morris, R. E. (1997). Spatial memory deficits in patients with unilateral damage to the right hippocampal formation. Neuropsychologia 35, 11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(96)00051-6

Addis, D. R., Pan, L., Vu, M.-A., Laiser, N., and Schacter, D. L. (2009). Constructive episodic simulation of the future and the past: distinct subsystems of a core brain network mediate imagining and remembering. Neuropsychologia 47, 2222–2238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.10.026

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., and Schacter, D. L. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia 45, 1363–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016

Aguirre, G. K., and D’Esposito, M. (1999). Topographical disorientation: a synthesis and taxonomy. Brain 122, 1613–1628. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.9.1613

Ashburner, J., and Friston, K. J. (2000). Voxel-based morphometry—the methods. Neuroimage 11, 805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582

Bohbot, V. D., Iaria, G., and Petrides, M. (2004). Hippocampal function and spatial memory: evidence from functional neuroimaging in healthy participants and performance of patients with medial temporal lobe resections. Neuropsychology 18, 418–425. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.418

Bohbot, V. D., Kalina, M., Stepankova, K., Spackova, N., Petrides, M., and Nadel, L. (1998). Spatial memory deficits in patients with lesions to the right hippocampus and to the right parahippocampal cortex. Neuropsychologia 36, 1217–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00161-9

Burgess, N., Maguire, E. A., and O’Keefe, J. (2002). The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory. Neuron 35, 625–641. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00830-9

Cherney, I. D., and London, K. (2006). Gender-linked differences in the toys, television shows, computer games and outdoor activities of 5-to 13-year-old children. Sex Roles 54, 717–726. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9037-8

Chua, E. F., Schacter, D. L., Rand-Giovannetti, E., and Sperling, R. A. (2007). Evidence for a specific role of the anterior hippocampal region in successful associative encoding. Hippocampus 17, 1071–1080. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20340

Clayton, N. S., Reboreda, J. C., and Kacelnik, A. (1997). Seasonal changes of hippocampus volume in parasitic cowbirds. Behav. Processes 41, 237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(97)00050-8

Colarusso, R. P., and Hammill, D. D. (1972). Motor-Free Visual Perception Test. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications.

Colombo, M., Fernandez, T., Nakamura, K., and Gross, C. G. (1998). Functional differentiation along the anterior-posterior axis of the hippocampus in monkeys. J. Neurophysiol. 80, 1002–1005.

Corbetta, M., Kincade, J. M., Ollinger, J. M., McAvoy, M. P., and Shulman, G. L. (2000). Voluntary orienting is dissociated from target detection in human posterior parietal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 292–297. doi: 10.1038/73009

DeMaster, D. M., and Ghetti, S. (2013). Developmental differences in hippocampal and cortical contributions to episodic retrieval. Cortex 49, 1482–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.08.004

Doeller, C. F., King, J. A., and Burgess, N. (2008). Parallel striatal and hippocampal systems for landmarks and boundaries in spatial memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105, 5915–5920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801489105

Duvernoy, H. M. (2005). The Human Hippocampus: Functional Anatomy, Vascularization and Serial Sections with MRI. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Ecuyer-Dab, I., and Robert, M. (2004). Have sex differences in spatial ability evolved from male competition for mating and female concern for survival? Cognition 91, 221–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.09.007

Etchamendy, N., Konishi, K., Pike, G. B., Marighetto, A., and Bohbot, V. D. (2012). Evidence for a virtual human analog of a rodent relational memory task: a study of aging and fMRI in young adults. Hippocampus 22, 869–880. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20948

Feng, J., Spence, I., and Pratt, J. (2007). Playing an action video game reduces gender differences in spatial cognition. Psychol. Sci. 18, 850–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01990.x

Fyhn, M., Molden, S., Witter, M. P., Moser, E. I., and Moser, M.-B. (2004). Spatial representation in the entorhinal cortex. Science 305, 1258–1264. doi: 10.1126/science.1099901

Geary, D. C. (1995). Sexual selection and sex differences in spatial cognition. Learn. Individ. Differ. 7, 289–301. doi: 10.1016/1041-6080(95)90003-9

Geiser, C., Lehmann, W., and Eid, M. (2008). A note on sex differences in mental rotation in different age groups. Intelligence 36, 556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2007.12.003

Ghetti, S., DeMaster, D. M., Yonelinas, A. P., and Bunge, S. A. (2010). Developmental differences in medial temporal lobe function during memory encoding. J. Neurosci. 30, 9548–9556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3500-09.2010

Giedd, J. N., Castellanos, F. X., Rajapakse, J. C., Vaituzis, A. C., and Rapoport, J. L. (1997). Sexual dimorphism of the developing human brain. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 21, 1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(97)00158-9

Glück, J., and Fabrizii, C. (2010). Gender differences in the Mental Rotations Test are partly explained by response format. J. Individ. Differ. 31, 106–109. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000019

Goldstein, D., Haldane, D., and Mitchell, C. (1990). Sex differences in visual-spatial ability: the role of performance factors. Mem. Cognit. 18, 546–550. doi: 10.3758/bf03198487

Goldstein, J. M., Seidman, L. J., Horton, N. J., Makris, N., Kennedy, D. N., Caviness, V. S., et al. (2001). Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb. Cortex 11, 490–497. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.490

Good, C. D., Johnsrude, I., Ashburner, J., Henson, R. N., Friston, K. J., and Frackowiak, R. S. (2001). Cerebral asymmetry and the effects of sex and handedness on brain structure: a voxel-based morphometric analysis of 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage 14, 685–700. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0857

Grön, G., Wunderlich, A. P., Spitzer, M., Tomczak, R., and Riepe, M. W. (2000). Brain activation during human navigation: gender-different neural networks as substrate of performance. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 404–408. doi: 10.1038/73980

Hänggi, J., Buchmann, A., Mondadori, C. R., Henke, K., Jäncke, L., and Hock, C. (2010). Sexual dimorphism in the parietal substrate associated with visuospatial cognition independent of general intelligence. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 139–155. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21175

Hartley, T., Maguire, E. A., Spiers, H. J., and Burgess, N. (2003). The well-worn route and the path less traveled: distinct neural bases of route following and wayfinding in humans. Neuron 37, 877–888. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00095-3

Heil, M. (2002). The functional significance of ERP effects during mental rotation. Psychophysiology 39, 535–545. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.3950535

Holdstock, J., Mayes, A., Cezayirli, E., Isaac, C., Aggleton, J., and Roberts, N. (2000). A comparison of egocentric and allocentric spatial memory in a patient with selective hippocampal damage. Neuropsychologia 38, 410–425. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00099-8

Huang, Y., Coupland, N. J., Lebel, R. M., Carter, R., Seres, P., Wilman, A. H., et al. (2013). Structural changes in hippocampal subfields in major depressive disorder: a high-field magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.005

Iaria, G., and Barton, J. J. (2010). Developmental topographical disorientation: a newly discovered cognitive disorder. Exp. Brain Res. 206, 189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2256-9

Iaria, G., Bogod, N., Fox, C. J., and Barton, J. J. (2009). Developmental topographical disorientation: case one. Neuropsychologia 47, 30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.08.021

Iaria, G., Chen, J. K., Guariglia, C., Ptito, A., and Petrides, M. (2007). Retrosplenial and hippocampal brain regions in human navigation: complementary functional contributions to the formation and use of cognitive maps. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 890–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05371.x

Iaria, G., Lanyon, L. J., Fox, C. J., Giaschi, D., and Barton, J. J. (2008). Navigational skills correlate with hippocampal fractional anisotropy in humans. Hippocampus 18, 335–339. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20400

Iaria, G., Petrides, M., Dagher, A., Pike, B., and Bohbot, V. D. (2003). Cognitive strategies dependent on the hippocampus and caudate nucleus in human navigation: variability and change with practice. J. Neurosci. 23, 5945–5952.

Jackson, O. III, and Schacter, D. L. (2004). Encoding activity in anterior medial temporal lobe supports subsequent associative recognition. Neuroimage 21, 456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.050

Jacobs, L. F., and Spencer, W. D. (1994). Natural space-use patterns and hippocampal size in kangaroo rats. Brain Behav. Evol. 44, 125–132. doi: 10.1159/000113584

Kempermann, G., Kuhn, H. G., and Gage, F. H. (1998). Experience-induced neurogenesis in the senescent dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 18, 3206–3212.

Koscik, T., O’Leary, D., Moser, D. J., Andreasen, N. C., and Nopoulos, P. (2009). Sex differences in parietal lobe morphology: relationship to mental rotation performance. Brain Cogn. 69, 451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.09.004

Krebs, J. R., Sherry, D. F., Healy, S. D., Perry, V. H., and Vaccarino, A. L. (1989). Hippocampal specialization of food-storing birds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 86, 1388–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1388

Kucian, K., Loenneker, T., Dietrich, T., Martin, E., and Von Aster, M. (2005). Gender differences in brain activation patterns during mental rotation and number related cognitive tasks. Psychol. Sci. 47, 112–131.

Kühn, S., and Gallinat, J. (2014). Amount of lifetime video gaming is positively associated with entorhinal, hippocampal and occipital volume. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 842–847. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.100

Kühn, S., Gleich, T., Lorenz, R. C., Lindenberger, U., and Gallinat, J. (2014). Playing Super Mario induces structural brain plasticity: gray matter changes resulting from training with a commercial video game. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 265–271. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.120

Kumaran, D., and Maguire, E. A. (2005). The human hippocampus: cognitive maps or relational memory? J. Neurosci. 25, 7254–7259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1103-05.2005

Lee, D. W., Miyasato, L. E., and Clayton, N. S. (1998). Neurobiological bases of spatial learning in the natural environment: neurogenesis and growth in the avian and mammalian hippocampus. Neuroreport 9, R15–R27. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00076

Lee, A. C., Yeung, L.-K., and Barense, M. D. (2012). The hippocampus and visual perception. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:91. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00091

Lepage, M., Habib, R., and Tulving, E. (1998). Hippocampal PET activations of memory encoding and retrieval: the HIPER model. Hippocampus 8, 313–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:4<313::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I

Linn, M. C., and Petersen, A. C. (1985). Emergence and characterization of sex differences in spatial ability: a meta-analysis. Child Dev. 56, 1479–1498. doi: 10.2307/1130467

Lippa, R. A., Collaer, M. L., and Peters, M. (2010). Sex differences in mental rotation and line angle judgments are positively associated with gender equality and economic development across 53 nations. Arch. Sex. Behav. 39, 990–997. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9460-8

Lisofsky, N., Mårtensson, J., Eckert, A., Lindenberger, U., Gallinat, J., and Kühn, S. (2015). Hippocampal volume and functional connectivity changes during the female menstrual cycle. Neuroimage 118, 154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.012

Lövdén, M., Schaefer, S., Noack, H., Kanowski, M., Kaufmann, J., Tempelmann, C., et al. (2010). Performance-related increases in hippocampal N-acetylaspartate (NAA) induced by spatial navigation training are restricted to BDNF Val homozygotes. Cereb. Cortex 21, 1435–1442. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq230

Lövdén, M., Schaefer, S., Noack, H., Bodammer, N. C., Kühn, S., Heinze, H. J., et al. (2012). Spatial navigation training protects the hippocampus against age-related changes during early and late adulthood. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 620.e9–620.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.013

Lütke, N., and Lange-Küttner, C. (2015). Keeping it in three dimensions: measuring the development of mental rotation in children with the rotated colour cube test (RCCT). Int. J. Dev. Sci. 9, 95–114. doi: 10.3233/dev-14154

Maeda, Y., and Yoon, S. Y. (2013). A meta-analysis on gender differences in mental rotation ability measured by the Purdue spatial visualization tests: visualization of rotations (PSVT: R). Educ. Psychol. Rev. 25, 69–94. doi: 10.1007/s10648-012-9215-x

Maguire, E. A. (1997). Hippocampal involvement in human topographical memory: evidence from functional imaging. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 352, 1475–1480. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0134

Maguire, E. A., Burgess, N., Donnett, J. G., Frackowiak, R. S., Frith, C. D., and O’Keefe, J. (1998). Knowing where and getting there: a human navigation network. Science 280, 921–924. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.921

Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., Good, C. D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S., et al. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 97, 4398–4403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070039597

Maguire, E. A., Nannery, R., and Spiers, H. J. (2006a). Navigation around London by a taxi driver with bilateral hippocampal lesions. Brain 129, 2894–2907. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl286

Maguire, E. A., Woollett, K., and Spiers, H. J. (2006b). London taxi drivers and bus drivers: a structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus 16, 1091–1101. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20233

Malykhin, N. V., and Coupland, N. J. (2015). Hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depressive disorder. Neuroscience 309, 200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.047

Maylor, E. A., Reimers, S., Choi, J., Collaer, M. L., Peters, M., and Silverman, I. (2007). Gender and sexual orientation differences in cognition across adulthood: age is kinder to women than to men regardless of sexual orientation. Arch. Sex. Behav. 36, 235–249. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9155-y

Mellet, E., Bricogne, S., Tzourio-Mazoyer, N., Ghaëm, O., Petit, L., Zago, L., et al. (2000). Neural correlates of topographic mental exploration: the impact of route versus survey perspective learning. Neuroimage 12, 588–600. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0648

Merrill, E. C., Yang, Y., Roskos, B., and Steele, S. (2016). Sex differences in using spatial and verbal abilities influence route learning performance in a virtual environment: a comparison of 6- to 12-year old boys and girls. Front. Psychol. 7:258. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00258

Moè, A. (2009). Are males always better than females in mental rotation? Exploring a gender belief explanation. Learn. Individ. Differ. 19, 21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2008.02.002

Monahan, J. S., Harke, M. A., and Shelley, J. R. (2008). Computerizing the mental rotations test: are gender differences maintained? Behav. Res. Methods 40, 422–427. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.2.422

Okagaki, L., and Frensch, P. A. (1994). Effects of video game playing on measures of spatial performance: gender effects in late adolescence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 15, 33–58. doi: 10.1016/0193-3973(94)90005-1

O’Keefe, J. (1976). Place units in the hippocampus of the freely moving rat. Exp. Neurol. 51, 78–109. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90055-8

Ozel, S., Larue, J., and Molinaro, C. (2004). Relation between sport and spatial imagery: comparison of three groups of participants. J. Psychol. 138, 49–64. doi: 10.3200/jrlp.138.1.49-64

Peronnet, F., and Farah, M. J. (1989). Mental rotation: an event-related potential study with a validated mental rotation task. Brain Cogn. 9, 279–288. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(89)90037-7

Peters, M. (2005). Sex differences and the factor of time in solving Vandenberg and Kuse mental rotation problems. Brain Cogn. 57, 176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.052

Peters, M., Laeng, B., Latham, K., Jackson, M., Zaiyouna, R., and Richardson, C. (1995). A redrawn Vandenberg and Kuse mental rotations test-different versions and factors that affect performance. Brain Cogn. 28, 39–58. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1995.1032

Pruessner, J., Collins, D., Pruessner, M., and Evans, A. (2001). Age and gender predict volume decline in the anterior and posterior hippocampus in early adulthood. J. Neurosci. 21, 194–200.

Raven, J. C., and Court, J. H. (1998). Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford, UK : Oxford Psychologists Press.

Rehkämper, G., Haase, E., and Frahm, H. D. (1988). Allometric comparison of brain weight and brain structure volumes in different breeds of the domestic pigeon, Columba livia fd (fantails, homing pigeons, strassers). Brain Behav. Evol. 31, 141–149. doi: 10.1159/000116581

Reilly, D., and Neumann, D. L. (2013). Gender-role differences in spatial ability: a meta-analytic review. Sex Roles 68, 521–535. doi: 10.1007/s11199-013-0269-0

Robert, M., and Héroux, G. (2004). Visuo-spatial play experience: forerunner of visuo-spatial achievement in preadolescent and adolescent boys and girls? Infant Child Dev. 13, 49–78. doi: 10.1002/icd.336

Roberts, J. E., and Bell, M. A. (2003). Two-and three-dimensional mental rotation tasks lead to different parietal laterality for men and women. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 50, 235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(03)00195-8

Sanchez, C. A. (2012). Enhancing visuospatial performance through video game training to increase learning in visuospatial science domains. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 19, 58–65. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0177-7

Sargolini, F., Fyhn, M., Hafting, T., McNaughton, B. L., Witter, M. P., Moser, M.-B., et al. (2006). Conjunctive representation of position, direction and velocity in entorhinal cortex. Science 312, 758–762. doi: 10.1126/science.1125572

Save, E., Poucet, B., Foreman, N., and Buhot, M.-C. (1992). Object exploration and reactions to spatial and nonspatial changes in hooded rats following damage to parietal cortex or hippocampal formation. Behav. Neurosci. 106, 447–456. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.106.3.447

Schweizer, K., Goldhammer, F., Rauch, W., and Moosbrugger, H. (2007). On the validity of Raven’s matrices test: does spatial ability contribute to performance? Pers. Individ. Dif. 43, 1998–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.008

Semrud-Clikeman, M., Fine, J. G., Bledsoe, J., and Zhu, D. C. (2012). Gender differences in brain activation on a mental rotation task. Int. J. Neurosci. 122, 590–597. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.693999

Sereno, M. I., Dale, A., Reppas, J., Kwong, K., Belliveau, J., Brady, T., et al. (1995). Borders of multiple visual areas in humans revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Science 268, 889–893. doi: 10.1126/science.7754376

Shepard, R. N., and Metzler, J. (1971). Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science 171, 701–703. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3972.701

Sherry, D. F., Vaccarino, A. L., Buckenham, K., and Herz, R. S. (1989). The hippocampal complex of food-storing birds. Brain Behav. Evol. 34, 308–317. doi: 10.1159/000116516

Sorby, S., Casey, B., Veurink, N., and Dulaney, A. (2013). The role of spatial training in improving spatial and calculus performance in engineering students. Learn. Individ. Differ. 26, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2013.03.010

Spence, I., Yu, J. J., Feng, J., and Marshman, J. (2009). Women match men when learning a spatial skill. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 35, 1097–1103. doi: 10.1037/a0015641

Sperling, R., Chua, E., Cocchiarella, A., Rand-Giovannetti, E., Poldrack, R., Schacter, D. L., et al. (2003). Putting names to faces: successful encoding of associative memories activates the anterior hippocampal formation. Neuroimage 20, 1400–1410. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00391-4

Strange, B. A., and Dolan, R. J. (2001). Adaptive anterior hippocampal responses to oddball stimuli. Hippocampus 11, 690–698. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1084

Suzuki, M., Hagino, H., Nohara, S., Zhou, S.-Y., Kawasaki, Y., Takahashi, T., et al. (2005). Male-specific volume expansion of the human hippocampus during adolescence. Cereb. Cortex 15, 187–193. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh121

Terlecki, M. S., and Newcombe, N. S. (2005). How important is the digital divide? The relation of computer and videogame usage to gender differences in mental rotation ability. Sex Roles 53, 433–441. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-6765-0

Travis, S. G., Huang, Y., Fujiwara, E., Radomski, A., Carter, R., Seres, P., et al. (2014). High field structural MRI reveals specific episodic memory correlates in the subfields of the hippocampus. Neuropsychologia 53, 233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.016

Tzuriel, D., and Egozi, G. (2010). Gender differences in spatial ability of young children: the effects of training and processing strategies. Child Dev. 81, 1417–1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01482.x

Voyer, D., Voyer, S., and Bryden, M. P. (1995). Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: a meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychol. Bull. 117, 250–270. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.250

Wei, W., Lu, H., Zhao, H., Chen, C., Dong, Q., and Zhou, X. (2012). Gender differences in children’s arithmetic performance are accounted for by gender differences in language abilities. Psychol. Sci. 23, 320–330. doi: 10.1177/0956797611427168

Keywords: sex difference, mental rotation, anterior hippocampus, brain structure

Citation: Wei W, Chen C, Dong Q and Zhou X (2016) Sex Differences in Gray Matter Volume of the Right Anterior Hippocampus Explain Sex Differences in Three-Dimensional Mental Rotation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10:580. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00580

Received: 21 January 2016; Accepted: 02 November 2016;

Published: 15 November 2016.

Edited by:

Claudia Voelcker-Rehage, Chemnitz University of Technology, GermanyReviewed by:

Rachael D. Seidler, University of Michigan, USAChris Lange-Küttner, London Metropolitan University, UK

Copyright © 2016 Wei, Chen, Dong and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution and reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinlin Zhou, emhvdV94aW5saW5AYm51LmVkdS5jbg==

Wei Wei

Wei Wei Chuansheng Chen

Chuansheng Chen Qi Dong

Qi Dong Xinlin Zhou

Xinlin Zhou