- Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy (Development studies), University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Introduction: Bangladesh currently hosts over a million Rohingya refugees in 33 fetid, dire, and confined camps, with the majority arriving after the 2017 military crackdown in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. Although Rohingya refugees have been arriving in Bangladesh since the 1970s, the mass influx following the 2017 military hostilities in Myanmar’s Rakhine State marked a significant crisis escalation. Initially, the local host communities displayed positive, sympathetic attitudes toward the refugees. However, recent evidence suggests a significant decline in social cohesion and peaceful coexistence, with host communities expressing diminished sympathy and growing concerns over the refugees’ prolonged presence in Cox’s Bazar.

Objectives: This paper investigates the factors influencing the peaceful coexistence between Rohingya refugees and host communities, drawing on the perspectives of development and humanitarian service providers in the Ukhiya and Teknaf sub-districts of Cox’s Bazar.

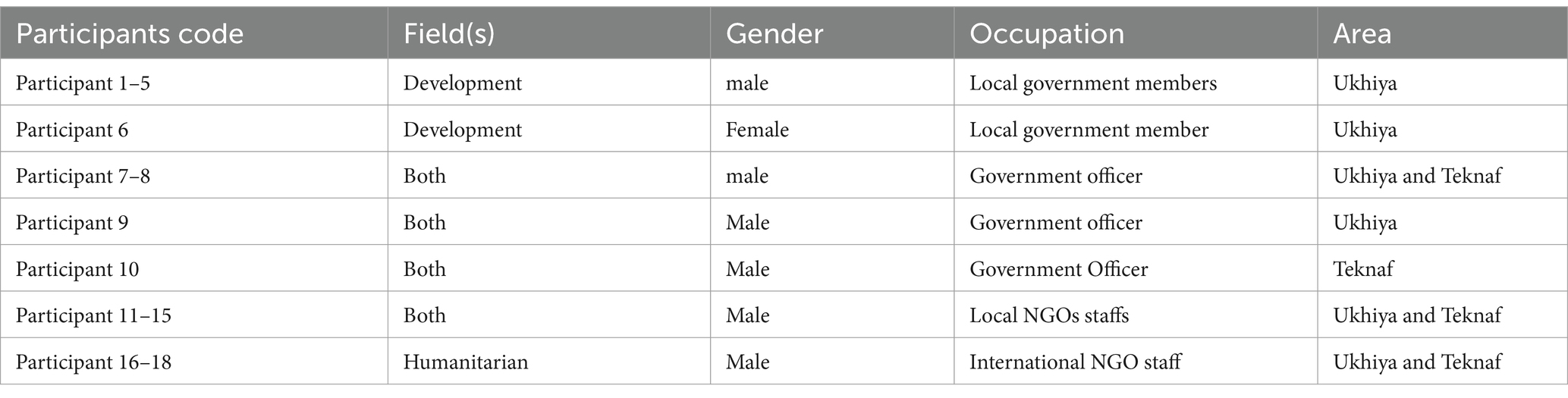

Methods: The study utilized a mix of theoretical literature and empirical data to identify five determining factors: economic, social, political, cultural, and environmental. Data collection included 18 in-depth key informant interviews, supplemented by analyses of secondary sources drawn from both gray and academic literature.

Findings: The findings indicate that perceived outgroup threats are increasingly undermining peaceful coexistence, despite the absence of direct conflicts between the host and refugees. While political and cultural factors have remained relatively stable, social, economic, and environmental factors continue to erode the current status of peace.

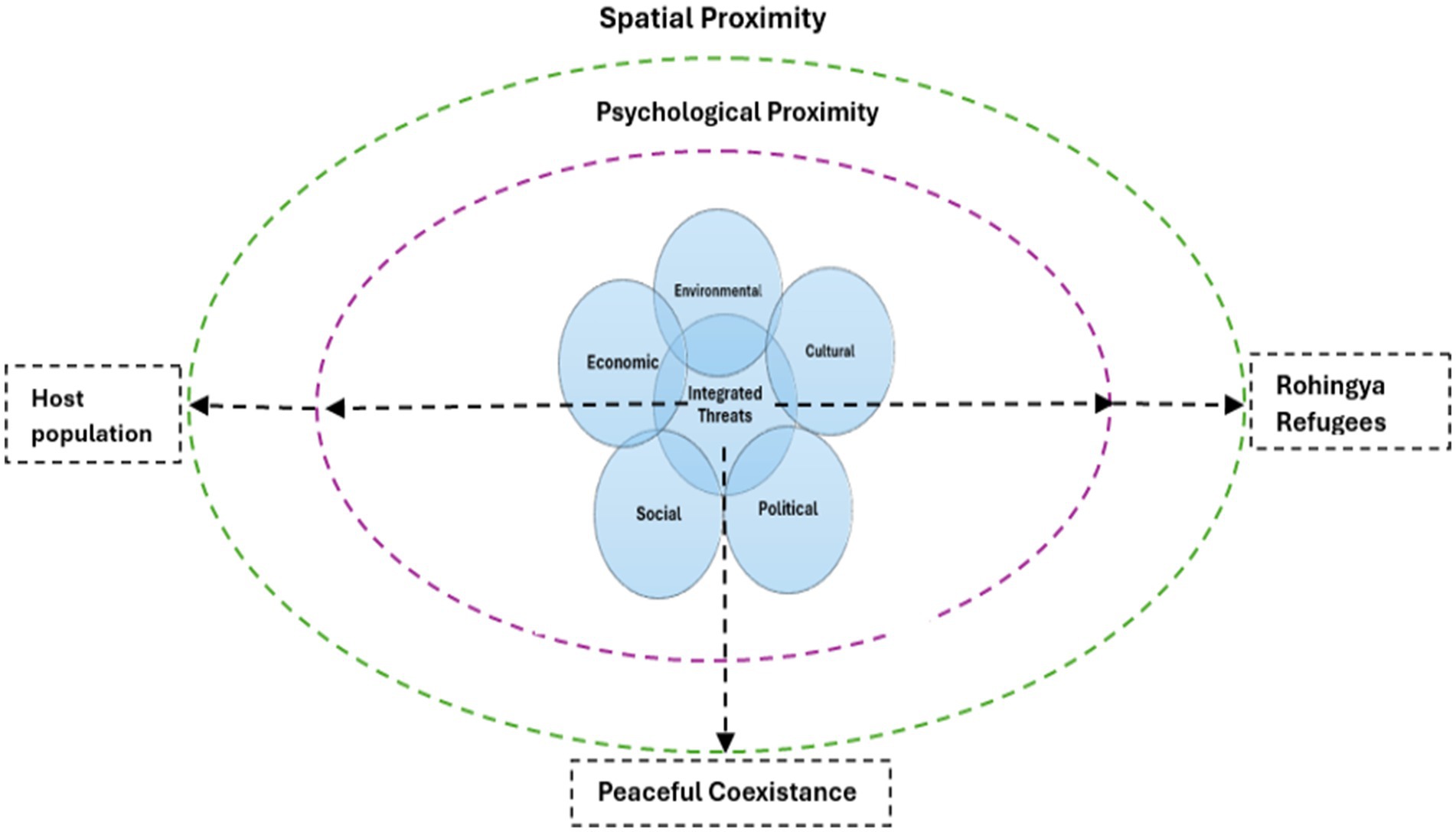

Discussion: The study highlights spatial and psychological proximity as critical overarching factors in fostering peaceful coexistence. It concludes that closer proximity heightens integrated threats, whereas maintaining optimal distance enhances the likelihood of peaceful coexistence. Therefore, the Rohingya response plan should incorporate conflict-sensitive strategies to tackle the adversity of threat factors while maintaining social cohesion as promoting peaceful coexistence between hosts and refugees.

1 Introduction

Since 2017, Bangladesh has experienced an unprecedented influx of Rohingya minorities onto its territory from Myanmar (Islam and Haque, 2024; Khan and Kontinen, 2022; Uddin, 2024). Predominantly, the Rohingyas are stateless, as Myanmar does not recognize their citizenship rights (Kamruzzaman et al., 2024; Sengupta, 2021) but rather labeling them as illegal Bengali migrants. Bangladesh, however, remains firmly opposed to any form of local integration of the Rohingyas within its territory. The statelessness of Rohingyas and their lack of legal recognition in both Myanmar and Bangladesh have led to severe marginalization, compelling them to live in conditions of extreme deprivation and indignity, often described as a “subhuman” life (Uddin, 2020). Currently, Bangladesh accommodates approximately 1.3 million Rohingya refugees1 in filthy, confined, and impoverished camp conditions. The sudden arrival of a mass influx of refugees induced a demographic change within the host community in Cox’s Bazar (Meem, 2024), making them a minority (Habib and Roy Chowdhury, 2023; Kamruzzaman et al., 2024) and susceptible to poverty (Ahmad and Naeem, 2020).

Initially, the host communities demonstrated a sympathetic attitude toward the Rohingya minorities through “everyday humanitarianism” (Lewis, 2019), likely due to their shared religious convictions and Muslim sentiment (Islam, 2024). However, within a few months, the same set of host communities became desperate, expressing hostility and disappointment with the Rohingyas, demanding their speedy return to Myanmar. The humanitarian actors in Cox’s Bazar are experiencing an increase in anti-refugee attitudes by the host communities (Siddiqi, 2022), which is further contributing to the creation of a hostile atmosphere for refugees.

Today, the level of progress toward a dignified and voluntary return is questionable (Uddin, 2024), as the situation in Myanmar remains unfavorable due to the 2022 military coup d’état. As a result, the situation in Myanmar has become increasingly complex, and the lack of a clear timeline for the voluntary repatriation of Rohingyas has exacerbated anxiety and fear among both communities (Meem, 2024). In reality, the Rohingyas may remain in the Bangladesh camps for an indefinite period until a viable solution to the crisis is found. The Bangladeshi government is steadfast in advocating for the local integration of Rohingya refugees within its territory. In fact, Bangladesh’s government has not finalized or implemented a comprehensive policy for the Rohingya refugee crisis for several decades (Siddiqi and Kamruzzaman, 2021). Therefore, host communities and refugees are evidently at odds over social cohesion in Cox’s Bazar (Cook and Ne, 2018). Notably, this article defines social cohesion as peaceful coexistence to avoid the ambiguity of the term and its relationship to the policy framework, given that invested agencies often politicize such policies (Meem, 2024).

Furthermore, the Rohingyas and the host communities encounter a variety of challenges in their efforts to extend the tenure of settlements surrounding Cox’s Bazar. Today, the tension between the host and refugee communities has escalated into social conflicts (Islam, 2024; Ansar and Khaled, 2021). For example, the rise in forcibly displace Rohingyas migration in Bangladesh has resulted in a corresponding rise in political instability (Olney et al., 2019). Moreover, concerns exist regarding the refugees’ involvement in illicit activities such as the smuggling of weapons, drugs, and human trafficking (Kamruzzaman et al., 2024), which has led to state security threats in Bangladesh stemming from the refugee crisis beyond its borders. Although Bangladesh’s policy prohibits Rohingyas from working outside of the camps, they are roaming freely and occupying local livelihoods, providing affordable labor for the adjacent paddy fields, salt farms, and other daily labor tasks (Hoque, 2021).

In addition, the Rohingyas are encroaching on the local market and negatively impacting employment prospects and the host community’s standard of living (Kudrat-E-Khuda, 2020). The local population also faces a shortage of potable water due to excessive groundwater extraction, leading to a decline in aquifer levels. Moreover, the ongoing turf conflict between the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) and the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO) in the camp areas further complicates peace measures (International Crisis Group, 2023; Khan, 2024). If the persistent tensions between host communities and Rohingya refugees remain unresolved, the hostile atmosphere could quickly degenerate into a conflict scenario (Masum, 2021). As a result, the host population’s initial empathy for the Rohingyas has gradually diminished, leading to a less peaceful cohabitation between the host and the refugees in Cox’s Bazar (Siddiqi et al., 2024).

Shedding light on the adverse impacts of Rohingya presence, this article investigates the factors influencing the peaceful coexistence between Rohingya refugees and host communities in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. The study asks the research question: How do various determining factors influence the peaceful coexistence of Rohingya refugees and host communities in Bangladesh? It uses 18 in-depth key informant interviews (KII) with development and humanitarian service providers in the Ukhiya and Teknaf subdistricts of Cox’s Bazar, as well as secondary data from the academic literature and the gray literature (e.g., organizational reports, policy briefs, working papers, etc.). The study identified five determining factors: economic, social, political, cultural, and environmental, which are increasing resentment among the ingroup host communities and threatening peaceful coexistence with outgroup Rohingya refugees. Political and cultural factors have remained relatively stable, while social, economic, and environmental factors continue to undermine the current status of peace. The study argues that spatial and psychological proximity are critical overreaching factors in fostering peaceful coexistence. It concludes that the closer proximity between two groups heightens the integrated threats, while maintaining an optimal distance proportionately increases the likelihood of peaceful coexistence.

2 Impacts of the Rohingya Crisis on Bangladesh: literature review

Identifying and analyzing the impacts of the Rohingya crisis and drawing insights from existing literature clarifies the root causes of host animosity. This understanding is important for operationalizing the factors that influence social cohesion and foster peaceful coexistence between hosts and refugees in Cox’s Bazar. However, under the current legislative framework for managing refugees in Bangladesh, social inclusion of Rohingyas in host communities remains a challenging undertaking (Siddiqi, 2022). Therefore, the understanding of the term “social cohesion” varies across different contexts. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines a cohesive society as one that works toward the wellbeing of all its members, fights exclusion and marginalization, creates a sense of belonging, promotes trust, and offers its members the opportunity of upward mobility (OECD, 2012).

Fonseca et al. (2019) cited sociologist Emile Durkheim’s (1897) well-known definition of social cohesion. According to Durkheim, social cohesion is a quality of a society that shows how its members depend on each other and is supported by two things: (i) the lack of hidden social conflict and (ii) strong social bonds. Until now, Bangladesh’s lack of a comprehensive refugee policy, which draws a clear distinction between social integration and the peaceful cohabitation of hosts and refugees in the absence of social cohesiveness, poses a significant obstacle to ensuring the Rohingyas’ numerous rights and the strategy for social cohesion (Siddiqi, 2022).

Furthermore, the comprehensive review of literature indicates that while a small number of host community members have improved their financial conditions because of the Rohingya displacement in Cox’s Bazar, the majority of locals became more miserable (Sultana, 2023). The World Bank’s “Cox’s Bazar Inclusive Growth Diagnostic” study reveals that the intensity of nightlights indicates increased economic activity in markets near the Rohingya camps, as indicated by the proliferation of nighttime lights (World Bank, 2022). However, the existing research on the impacts of Rohingya presence in Cox’s Bazar indicates an increased likelihood of recurring social turf conflicts between the host and refugees (Khan, 2023), while also emphasizing negative socio-economic impact on local livelihoods (Ullah et al., 2021).

According to Biswas et al. (2022), the primary source of conflict between the Rohingya and host communities in Cox’s Bazar is the scarcity of natural resources. The presence of Rohingya refugees in the camps and surrounding host areas has exerted significant pressure on natural resources and the environment, including deforestation, land degradation, depletion of groundwater, loss of biomass, ecological imbalance, and a decline in biodiversity (Habib and Roy Chowdhury, 2023). Kudrat-E-Khuda (2020) notes that the Rohingya crisis has led to significant alterations in the local economy and employment structures in Cox’s Bazar. Moreover, the locals are grappling with severe economic pressure due to a sharp rise in the cost of living in the areas surrounding the refugee camps, driven by price hikes and declining wages (Sattar, 2019). Siddiqi et al. (2024) assert that Bangladeshi law prohibits Rohingya refugees from earning a cash-based wage, with very few exceptions to those who work inside the camps. However, Rohingyas roam freely outside the camps and occupy the local labor markets, thereby impacting the livelihoods of locals.

Additionally, Habib and Roy Chowdhury (2023) found that the existing tension between hosts and refugees is becoming more intense because of forest resources (Sultana, 2023). In the immediate aftermath of the influx in 2017, Bangladesh allocated over 6,500 acres of land in the Ukhiya and Teknaf subdistricts in Cox’s Bazar (Habib, 2023; Habib and Roy Chowdhury, 2023). The immediate creation of settlement camps to accommodate the displaced Rohingya migrants resulted in significant destruction through extensive forest clearing (Ullah et al., 2021). The Department of Agriculture Extension (DoAE) data indicates that the refugee presence caused damage to around 100 hectares of cropland in Teknaf/Ukhiya, leading to the destruction of grazing land. Additionally, humanitarian organizations and refugee encampments have allocated around 76 hectares (Ha) of cultivable land without providing any financial compensation to the farmers (Hashim, 2019; Joireman and Haddad, 2023). Moreover, while managing hundreds and of thousands of refugees, the camps were generating approximately 10,000 tons of solid waste every month, which resulted in the blockage of canals and surrounding streams (Halim et al., 2021). During periods of heavy rainfall, surface water becomes contaminated, leading to the development of waterborne infections and diseases (Habib and Roy Chowdhury, 2023).

Additionally, the potential involvement of refugees in criminal activities such as arms smuggling, drug trafficking, and human trafficking has significantly impacted the social security system in Cox’s Bazar. For long, Myanmar is widely recognized as a “narco-state” (Rahman, 2010, p. 236). The Naf River delineates the boundary between Myanmar and Bangladesh, subsequently serving as a conduit for Myanmar drug traffickers and arms smugglers. According to Kamruzzaman et al. (2024), the Rohingya crisis has significantly deteriorated social security, and the government is grappling with the “Yaba epidemic”—a surge in methamphetamine drug pills originating from Myanmar. Furthermore, the Rohingya crisis has led to a surge in illicit activities, such as homicides and gang violence, extrajudicial killings by law enforcement agencies, and even violence among the Rohingya themselves within the camps. Furthermore, Mohiuddin and Molderez (2023) noted that marriages between the Rohingya and Bengali ethnic groups frequently result in discord, domestic violence, and instability, a situation further compounded by the growing prevalence of polygamy and child marriage within the Rohingya community. Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence of the integration of Rohingyas into the host communities through marriages by Bangladeshi citizens (Sultana, 2023).

Moreover, the Rohingya crisis is also jeopardizing the governance structure in Bangladesh. At the onset of the Rohingya crisis in 2017, the government of Bangladesh initially lacked domestic expertise in managing large-scale emergency responses. Consequently, the United Nations` (UN) and multiple international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) implemented a multi-sectoral strategy to tackle the refugee situation in Cox’s Bazar. Therefore, organizing and establishing an externally guided mechanism for delivering policy advice became progressively politicized within Bangladesh’s governmental system (Chowdhury, 1995). Due to the adverse impacts of the protracted Rohingya crisis, anti-refugee sentiment is rising in the host communities in Cox’s Bazar, creating a hostile environment for refugees. If ongoing tensions between Rohingya refugees and host communities remain unaddressed, the hostile environment might easily turn into a conflict situation (Masum, 2021), which threatens the peaceful coexistence of Rohingya refugees and host communities in Cox’s Bazar (Siddiqi, 2022).

Nevertheless, the negative attitudes and adverse impacts of the Rohingya presence and the hostile reflection toward the outgroup Rohingyas can be analysed through the lens of group conflict theory, as the in-groups feel threatened regarding their economic and cultural interests (Ullah et al., 2021). In the next chapter, I will introduce the theoretical framework that identifies the nature of these threats and discuss the peaceful coexistence of the two groups amidst the Rohingya crisis.

3 Theoretical concepts of this study

Social cohesion is an essential element for sustainable peace (Grossenbacher, 2020). Generally, the term “social cohesion” refers to the ties that hold people together within and between communities and the willingness of community members to engage and cooperate to survive and prosper (Kim et al., 2020). However, the definition of “social cohesion” varies depending on the context, as it serves a distinct response to conflicts, and plays a crucial role in fostering peaceful coexistence (Uddin et al., 2021) between host communities and Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Moreover, it is associated with a sense of belonging and trust—both in individuals and in institutions, vis-à-vis expressing respect to each other in the neighborhood (Grossenbacher, 2020). Conversely, the prevailing perception of threat and deep-seated mistrust between the groups significantly erodes the resilience required to sustain peace.

The intergroup threat theory (ITT) (Stephan and Stephan, 2000) is relevant to explain the conflict dynamics and the rising tensions between Rohingya refugees and host communities in Cox’s Bazar. ITT poses that when one group perceives another as capable of causing harm, conflict may arise (Stephan et al., 2009). Initially, known as integrated threat theory, ITT encompasses two fundamental categories of threats: realistic, involving concerns over physical harm or loss of resources, a group’s power, and overall wellbeing; and symbolic threats, which refer to undermining an individual’s self-identity or self-esteem. The Rohingya crisis presents the Rohingyas as outgroups and the host communities living near the camps as ingroups. Four main factors influence the perceived threat from another group: the intergroup relations between the groups, the cultural values of the group members, the interaction between the groups, and individual differences (Stephan et al., 2009).

Intergroup relations significantly shape the perception of threats, particularly the low-power groups, which are more vulnerable to both realistic (e.g., resource loss, violence) and symbolic (e.g., perceived social deviants) threats from high-power groups. The mass influx of Rohingya refugees into Cox’s Bazar has turned the host communities into a minority, leading them to view the Rohingyas as a threat to the host population. The cultural dimension concerns how collectivist societies, which include values, standards, rules, conventions, and beliefs, perceive greater symbolic threats from outgroups. Locals perceive the Rohingyas, who migrated from Rakhine State and speak the local Chittagong dialect, as a threat to Cox’s Bazar’s distinct culture, customs, and language, despite their shared cultural and religious ties.

The situation factors further exacerbate perceived threats because the interaction between groups, particularly when restricted by physical or social boundaries, influences group dynamics. In Cox’s Bazar, the Rohingyas movement beyond the camps has created fear and hostility among the host communities due to the intergroup armed violence and turf wars (e.g., between ARSA and RSO) within the camps, posing a tangible threat. The host’s behavior undergoes a significant transformation, and the situational elements pose a genuine threat to their communities.

Lastly, the individual difference variables, such as the strength of intergroup identity, knowledge of the outgroup, and quantity and nature of contact, influence the threat perception. Group members who have less familiarity with the outgroups are more vulnerable to threats compared to those who possess significant knowledge about them. Hence, group threats have a stronger correlation with individual difference variables, such as collective self-esteem and valuing social order, than with individual threats. The presence of refugees has resulted in a strain on local resources, environmental degradation, and heightened social insecurity, which in turn intensifies perceived threats to the outgroup Rohingya.

4 Materials and methods

To investigate the factors influencing peaceful coexistence between refugees and the host communities in Cox’s Bazar, this study employed a qualitative approach, using semi-structured key informant interviews (Given, 2008). The study conducted a total of 18 interviews with purposefully selected service providers (Berndt, 2020) who are involved in humanitarian and development fields, serving both host and refugee populations in the Cox’s Bazar district. The study sites are both Ukhiya and Teknaf subdistricts in Cox’s Bazar district, where the largest refugee camps are located.

The participants comprised government officials (camp in charge, Deputy Commissioner’s office), Upazilla (subdistricts) officials, local and international NGO workers, and the representatives of local government in Cox’s Bazar. During a field visit for academic research in October–November 2022, a total of three in-depth face-to-face interviews were conducted by the author himself with the specific questionnaire on social cohesion of host and refugees in Cox’s Bazar, comprising two with government officials and one with representatives of local NGOs. Data for the remaining 15 interviews were collected online through Zoom and WhatsApp voice telephony services between February and May 2024. It is noteworthy that the author conducted some interviews using the snowball technique, as he received referrals from other experts during the process. The non-probability sampling strategy ensured the inclusion of participants with relevant expertise regarding the Rohingya humanitarian crisis. While considering the overall research design, it is grounded in the social-constructivist paradigm, which asserts that meaning is not readily apparent and can only be revealed through deep reflection and analysis, in line with the epistemological stance of the constructivist paradigm (Schwandt, 2000).

Notably, direct interviews with both refugees and host communities were avoided due to the political sensitivities surrounding the ongoing Rohingya crisis. Since the onset of the influx in 2017, the government of Bangladesh has shown reluctance toward permitting any form of Rohingya integration and has refrained from granting formal refugee status. This stance reflects a politically sensitive issue, encompassing the judicial complexities associated with refugee rights. However, concepts like social cohesion and coexistence hold significant political implications for the local integration of refugees in Bangladesh, potentially causing more harm than good for the refugee population.

In order to mitigate any potential bias associated with political sensitivities surrounding the issue, a more impartial approach was adopted by conducting interviews with service providers. These individuals, who possess practical knowledge of the underlying factors, offered a neutral and informed perspective on the dynamics of peaceful coexistence between the host and refugees in Cox’s Bazar. While this strategy limited direct interaction with the affected populations, it facilitated a more objective understanding of the integrated threats and impact factors determining the peaceful coexistence between two groups.

The information about the participation list has been enlisted in the following Table 1.

Most of the interviews lasted for a duration ranging from 30 to 50 min, with one exception where a local representative’s interview lasted only 15 min. Each interview was recorded only after obtaining explicit consent from the participants, confirming the anonymity of any quotes used in this paper to uphold ethical standards. The recorded interviews were subsequently transcribed and translated from Bengali to English, followed by manually coding utilizing thematic analysis techniques (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

In the process of operationalization of data, Braun and Clarke's (2012) six-phase recursive approach guided the thematic analysis, encompassing the following stages: (i) familiarization with the data; (ii) initial coding; (iii) generating initial themes; (iv) reviewing and developing themes; (v) refining and defining themes; and (vi) writing up. This approach led to the identification of five main themes influencing the peaceful coexistence between the host community and refugees during the Rohingya crisis. To enhance the rigor and accuracy of the analysis, a cross-check was conducted with organizational gray literature, including organizational reports, working papers, and relevant articles. This comprehensive review of data focused on the enablers and barriers of peaceful coexistence between the host community and refugees in Cox’s Bazar. The triangulation of data sources significantly contributed to a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics on the ground.

5 Presentations of the findings

This section presents an overview of the findings concerning the factors that impede the peaceful coexistence between the Rohingya refugees and the host population in Cox’s Bazar. Five major factors have been identified: economic, social, political, cultural, and environmental. These factors significantly influence the perceived threats from the host community (ingroup) toward the Rohingya refugees (outgroup).

5.1 Economic factor

The mass influx of Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar has significantly heightened economic strain on the local host community, leading to price hikes, inflation, and intensified competition for jobs etc. (Uddin et al., 2021). The presence of Rohingya refugees in the local job market exacerbates socio-economic inequalities by introducing a pool of cheap labor, potentially resulting in conflict with the local workforce. One interviewee noted that.

“Currently, a significant number of Rohingyas work outside the camps and receive low wages. This has led to growing frustration among the community members. If someone hires Rohingyas to plough or harvest paddy fields, they can pay them 200 or 300 BDT/Bangladeshi Taka (roughly $2/3 USD), whereas the local laborers command a rate of almost 500 BDT ($5 USD) per day. The Rohingyas readily find employment in the vicinity of the camps.” (Participant 12, NGO practitioner).

The Rohingyas` freedom of movement beyond the camps has further depressed local labor prices, as they are willing to accept significantly lower pay (often less than half of the prevailing market rate) for work in sectors such as paddy fields or salt farming, despite having their basic needs met by humanitarian relief. Concurrently, the unemployment rate within the host community has reached an unprecedented level (Sultana, 2023). Moreover, escalating prices of daily commodities have adversely affected the livelihoods and food consumption of the host communities.

Before the arrival of the Rohingya refugees, the local host population was mainly dependent on agriculture and the forest-based economies. However, the prolonged Rohingya presence in Ukhiya and Teknaf subdistricts has significantly diminished these livelihood options. Several respondents highlighted these shifts, noting that many local fishermen had to change their occupations due to a fishing ban on the Naf River, which has rendered approximately 30,000 to 35,000 fishermen unemployed and severely affected in their annual income (Mohiuddin and Molderez, 2023). Additionally, the expansion of the Rohingya refugee camps and the accompanying deforestation have forced the honey collectors to pursue alternative livelihoods. Many local farmers have shifted their occupation from agricultural work to construction work for the makeshift settlements in the Rohingya camps (Ansar and Khaled, 2021).

Moreover, the Rohingyas benefit from substantial humanitarian assistance. Despite the Rohingyas’ reliance on aid, the availability of local Burmese products in the local market further undermines their economic stability. The surplus of aid and its subsequent trade within the local market have engendered growing resentment among local entrepreneurs and small business owners. This is largely due to the fact that Rohingyas frequently sell relief items in local markets, which adversely impacting the viability of local businesses (Kamruzzaman et al., 2024; Sultana, 2023). In this context, an interviewee made the following observation:

If a Rohingya family needs 5 blankets, they often receive more than double from different organizations annually. So, what will they do with those extra blankets? They sell those extra blankets in nearby markets, which negatively disrupts local markets. So, this practice became their business. A similar situation occurs with food rations and other non-food items that negatively affecting the local business and socio-economic status of the host community (participant 9, government official).

Consequently, the degrading livelihood satisfaction in economic capabilities has exacerbated negative attitudes toward refugees in Cox’s Bazar, culminating in a marked rise in anti-refugee sentiment among the host population.

5.2 Social factor

The prolonged presence of Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar has led to various social challenges for the host community, thereby undermining peaceful coexistence. The local government’s respondents unanimously expressed concerns about the escalating social disorder and the locals’ frustration, which have been exacerbated by the Rohingya population’s perceived threats to the local population. One of the local Union Parishad (a unit of subdistricts) members postulated that,

“Drug dealers are roaming freely in Cox’s Bazar. The local youths are increasingly addicted to the Yaba drug, which is now widely available. Many local men are also marrying Rohingya women, even though they already have families and children. This is alarming for our society.’’ (Participant 3, local government member).

Cox’s Bazar has emerged as a hub for narcotics trafficking, due to its geographical proximity to Myanmar, particularly with the methamphetamine tablets (known as Yaba) trafficked across the Naf River. Drug traffickers often exploit vulnerable groups, including women and children, as couriers. The media has extensively reported on drug-related issues stemming from the growing refugee population, highlighting the operation of security forces and the confiscation of illicit substances from drug traffickers. Besides, other forms of criminal activity, such as kidnapping, extortion, and human trafficking, are also disrupting the local social order. Many Rohingya men attempt to migrate to Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand, often falling victim to traffickers in the process. Furthermore, the sex trade has increasingly exploited Rohingya women (Sakib, 2023). One international NGO actor expressed concern about the future, stating that “there is a significant likelihood that Rohingya youths, women, and children will become involved in illegal activities such as drug trafficking and organized crime. This could potentially lead to direct conflicts with the local population in Teknaf.” (Participant 18, NGO practitioner).

The murder of Rohingya prominent leader Mohib Ullah in 2021 further intensified security concerns within the camps and garnered significant local and international media attention. The escalating conflict among the armed groups, such as ARSA and RSO, has resulted in a significant rise in casualties and violence, prompting security forces to intervene. Due to the terrorist acts and ongoing turf wars between various Rohingya armed groups in the camps, the nearby host communities are experiencing heightened fear and tension, perceiving the camps as potential security threats. Another representative from a local NGO commented on the situation,

“I prefer to designate the residents of Cox's Bazar as the local community rather than the host community, because the entire community is bearing the burden of hosting the Rohingyas. There are substantial manifestations of social disruptions inside their society, including gender sensitivity issues, as local women feel a sense of negligence. This is because many women reported their husbands' marriages to Rohingya women without their consent and subsequently moved in the camps.’’ (Participant 11, NGO practitioner)

The rise of polygamy within the Rohingya camps is reportedly disrupting local social norms. Moreover, the proliferation of media coverage of counterfeit birth certificates and passport claims made by Rohingyas has raised significant security concerns in Bangladesh. Previously, Saudi Arabia repatriated several Rohingyas who possessed Bangladeshi passports, raising alarms about the integrity of identification documents. Further, reports from several areas in Cox’s Bazar indicate fraudulent use of the Bangladeshi National Identity (NID) and birth certificates (Sakib, 2023), exacerbating bureaucratic challenges in local government offices and escalating frustration among the local population.

5.3 Cultural factor

Despite religious and linguistic similarities between the local population of Bangladesh and Rohingya refugees, there remain significant cultural differences. Both communities share the Muslim faith and linguistic commonalities, which can facilitate interaction and social integration (Ansar and Khaled, 2021). However, Bangladesh’s cultural identity is closely linked to its affiliation with the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), whereas Myanmar’s culture aligns more with Southeast Asian traditions, as a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). These distinct cultural affiliations contribute to the complexities of coexistence between the two groups.

Generally, cultural influences are pivotal in shaping interactions between the host community in Chittagong, which adheres to the practices of Bengali culture, while the Rohingyas exclusively adhere to Muslim cultural traditions. Although both groups share a common faith, variations exist in their dietary customs and lifestyles. However, there are many commonalities, including food, attire, and festivals, that enable Rohingyas to navigate local social structures. This cultural affinity often leads to intermarriage and settlement beyond the refugee camps (Islam et al., 2023). Despite the restrictions on Rohingya mobility outside the camps, their ability to adapt to local life highlights the critical influence of cultural proximity in shaping social dynamics in Cox’s Bazar district. A government official in charge of camp management made the following observation:

“In the camps, we regularly handle cases of underage marriage and polygamy. The Rohingya leaders, known as majhis, bear the responsibility of reporting such incidents to us. However, due to the volume of complaints, it is not possible to promptly resolve every case. Rohingya women frequently report that they did not consent to their second marriages, or that they experienced verbal divorce (Talaq) as a result of their second marriage’’ (Participant 8, a government official).

Another respondent, a prominent national NGO practitioner, further observed that.

“Rohingyas speak and understand local Chatgaian dialect, and they share Muslim faith. Nevertheless, there are certain distinctions that are comprehensible to us as locals. They consume a specific variety of rice (atop type chal), and they employ Myanmar products. This also influences Bangladeshi culture, as it gives local residents access to Myanmar-made products. Child marriage is a prevalent practice. Additionally, local residents are travelling to the settlements to marry them, as they are able to reside there on humanitarian rations” (Participant 15; NGO practitioner).

The majority of the interviewees reported polygamous practices around the Kutupalong refugee settlements in Ukhiya, where many local married men enter into verbal agreements to marry Rohingya women in the presence of a mosque imam, bypassing formal registration. The food assistance program for the refugees in the camps registers the Rohingya women and their families, which alleviates the financial burden on local men for multiple marriages (Rahman et al., 2019).

Furthermore, language also serves as an integral component of culture and heritage. The Rohingya language, an Indo-Aryan language that is similar to the local “Chittagongian” dialect, facilitates communication between the two groups (ibid., 2019). However, the Bangladeshi government has imposed restrictions on formal education for Rohingyas in Bengali, fearing that it will serve as a pull factor for additional refugees seeking a better life in Bangladesh (Olney et al., 2019) and hinder the repatriation process.

5.4 Environmental factor

Environmental degradation has emerged as a critical factor affecting local ecology and contributing to land disputes in Cox’s Bazar. The majority of participants (1, 5, 6, 11, 15, 16, and 18) emphasized the negative environmental impact of the mass displacement of Rohingyas from Myanmar, with many locals viewing the refugees as a threat to their environment. One of the INGO respondents emphasized the depletion of groundwater resources, stating that,

“Cox's Bazar hosts over a million Rohingyas and local people. The early stages of the refugee response paid little attention to aquifer levels. The widespread installation of thousands of shallow tubewells led to a significant depletion of groundwater. Residents in Ukhiya, Ramu, and nearby places can no longer rely on shallow tubewells and must now use deep tubewells to extract drinking water.” (Participant 18, international NGO official).

Another respondent from a local NGO described the environmental challenges caused by the refugee settlements, noting that,

“The densely populated region surrounding the camps frequently blocks drainage systems during heavy rainfall. Deforestation, including the clearing of millions of trees and flattering of hilly terrain for Rohingya settlements, has led to landslides in the camps during monsoon season. Although the Rohingyas now use LPG gas, they previously relied on forest firewood.” (Participant 11, local government representative).

In addition to the water and sanitation challenges, Cox’s Bazar confronts various environmental issues, including soil erosion, rising sea level, increased landslides, etc. The accumulation of solid waste discharge obstructing the drainage canals near the camps, further exacerbates the prevalence of waterborne diseases (Habib and Roy Chowdhury, 2023). In particular, following a period of intense rainfall during monsoon season, surface water becomes contaminated and waterborne infections proliferate alarmingly. Additionally, deforestation, primarily driven by the urgent need for emergency shelters, has also endangered local wildlife, particularly disrupting the habitats and migration routes of wild elephants, thereby posing broader risks to the biodiversity of the region.

The large-scale relocation of refugees has also contributed to demographic strain, occupying cultivable land and limiting local resources. The iron-fenced perimeters of the camps further restrict the freedom of movement for both refugees and host communities, intensifying tensions regarding resource access. In Teknaf, the situation is particularly intricate, with many Rohingyas opting to rent private land rather than settling on government owned land (Khas land). This arrangement has led to shared usage of essential common resources, such as ponds and graveyards, creating additional issues of conflict. Notably, disputes have arisen when local residents have refused to allocate space for the burial of deceased Rohingyas. Consequently, the strain on land, water, and natural resources has deepened the socio-environmental tensions between the host communities and the Rohingya refugees.

5.5 Political factor

Bangladesh, characterized by its high population density, faces significant challenges in effectively accommodating a substantial influx of refugees, prompting the government to implement stringent administrative measures. The ongoing presence of refugees has placed the Bangladeshi government in a politically precarious position. Long-term policies for Rohingya refugees risk undermining efforts toward voluntary repatriation, which remains a politically sensitive issue. Further, the Rohingya crisis severely limited the effectiveness of refugee management and governance.

Initially, the government faced critical shortages of security personnel and administrative staff necessary to manage the sudden, large-scale migration, resulting in considerable deficiencies in the domestic advisory and refugee management systems. In response, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) stepped in to assist, leading the government of Bangladesh through the Inter-sector Coordination Group (ISCG) in developing a coordinated response. However, the involvement of international organizations has also externalized much of the policy advice, contributing to further politicizing the crisis and complicating the overall management efforts (Chowdhury, 1995).

Apart from that, the presence of organized armed groups inside the camps of Cox’s Bazar encounters numerous political challenges. These groups often contribute to instability, undermining the efforts of humanitarian organizations and the government authorities to maintain peace and conflict inside the camps. One of the local NGO workers recounted the difficulties in ensuring security, asserting that:

"We convened a meeting a few days ago and suggested that camp employees wear badges; however, we had to modify our approach shortly thereafter." The security force and the public refrain from questioning an individual who is operating with a badge, which could be problematic if a terrorist were to utilise the badge to engage in unlawful activities. "Identifying the culprits will be challenging. " (Participant 13, local NGO practitioner).

The Rohingya crisis has also influenced local politics. The local politicians in Cox’s Bazar have leveraged the situation, either to incite anti-Rohingya sentiment or to forge alliances with international NGOs for political gain. This exploitation has intensified political rivalries, with parties seeking to exploit the situation to bolster their support base. Nevertheless, it is evident that Naypyidaw has no intention of granting the Rohingya their requests for recognition as a national group, instead denying them citizenship, fundamental liberties, and access to services. The bilateral agreement between Myanmar and Bangladesh has not yielded any success. Consequently, the government is politically sensitive to the idea of implementing any long-term policy settings for the Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, as this could potentially undermine the efforts for voluntary repatriation. While local political leaders initially condemned the violence against the Rohingya, public perception has shifted, reflecting growing frustration with the protracted displacement and the several failed attempts of repatriation.

6 Discussion

The findings indicate that the current state of peaceful coexistence in the Rohingya camps of Cox’s Bazar is characterized by the absence of direct conflicts between the host community and the refugees. However, the identified factors contribute immensely to the changing attitudes among local host communities, fostering anti-Rohingya sentiments and perceiving the Rohingya refugees as a threat to the local communities. There is a substantial risk that Rohingyas would encounter severe forms of confrontation and animosity from the host populations in the near future, potentially eroding social cohesion as peaceful coexistence.

In the refugee settings, social cohesion programming must extend beyond merely managing intergroup tensions; it should incorporate a social (de-)cohesion lens to explore the deeper causes of growing discord between the groups (Grossenbacher, 2020). To identify the disrupting factors of the social cohesion, it is comprehensive to identify certain levels of interaction that contribute to or disrupt the social harmony. Social de-cohesion, as evidenced in everyday interaction between host and refugees, shapes broader societal norms, both social cohesion and conflict dynamics (ibid., 2020). The inter- and intra-communal tensions between the host and refugees in the camps have spurred increased security concern fueled by fear of direct threats, which reinforce harmful narratives from the outgroups Rohingya refugees. Eventually, the government authorities often reassess these contexts of the disrupting factors and impose restrictive policies that further inhibit cohesion between host and refugee communities, complicating pathways to peaceful coexistence.

Based on the identified disrupting factors that amplify resentment among the ingroup host communities and intensify the integrated threats between the host and the refugees, as well as the theoretical foundations of the integrated/intergroup threat theory discussed in the above section, it is posited that two groups are increasingly predisposed to adversarial rather than collaborative toward peace, resulting in social (de-)cohesion as peaceful coexistence. The degree of spatial and psychological proximity between the two groups largely influences intergroup tensions; as these proximity exposures increase, perceived threats intensify proportionately. To investigate these dynamics, an analytical framework (see Figure 1) is proposed, which examines both spatial and psychological proximity in relation to integrated threats on the ground. This framework underscores how proximity fosters conditions that exacerbate perceived threats, further complicating the likelihood of peaceful coexistence.

The findings of this study indicate that increased spatial and psychological proximity between hosts and refugees heightens perceived integrated threats for one group to another. This proximity exposure significantly influences peaceful coexistence, with closer living conditions amplifying perceived threats, particularly those associated with the Rohingya refugee population (see Figure 1). This pattern aligns with observations in other contexts; for instance, Ylitalo-James and Silke (2024), in their exploration of radicalization in Northern Ireland, found that proximity to areas of violent conflicts increased the potential for radicalization of the groups due to perceived threats. Similarly, the study by Lewis and Topal (2023) argues that conflict intensifies group divisions, reinforces in-group solidarities, and diminishes trust in the outgroup. Hence, the findings of this study resonate with this perspective, indicating that proximity—both spatial and psychological—are critical determinants of peaceful coexistence. Furthermore, identified five factors: economic, social, political, cultural, and environmental factors play critical roles in shaping these dynamics, establishing them as crucial variables in the interactions between the two groups.

While social and cultural factors have remained relatively stable, persistent political and environmental concerns threaten the current state of peace. The local population perceives the Rohingyas as a threat to Bangladeshi culture, with the crisis facilitating various criminal activities such as drug trafficking, armed robbery, maritime piracy, smuggling, and cross-border trafficking, which further exacerbate local tensions. A recent study by Biswas et al. (2022) reported a significant decline in residential satisfaction among host communities, with nearly all respondents expressing dissatisfaction stemming from overcrowded neighborhoods, deteriorating public services, and increased insecurity. Therefore, heightened violence and declining harmonious relationships between these groups intricately link to both spatial and psychological proximity.

For example, the relocation of Rohingyas to Bhasan Char (a newly developed island) may initially appear to alleviate tensions by distancing them physically from the host community (Islam and Siddika, 2022). However, the wire-fenced boundary surrounding the camps served to restrict the Rohingyas’ freedom of movement, thereby creating a psychological distance and intensifying perceived threats. In reality, the complete relocation of all Rohingyas to Bhasan Char or the immediate repatriation is not feasible. Thus, addressing the psychological proximity is also crucial to fostering peaceful coexistence between the host and refugee population in the affected areas.

Moreover, interpersonal communication is one of the main indicators for social cohesion as well as peaceful coexistence (Uddin et al., 2021). However, the interaction between hosts and refugees in Ukhiya and Teknaf remains minimal. The government of Bangladesh’s (GOB) has adopted an ad hoc policy on the Rohingya humanitarian response, demonstrating reluctance to acknowledge the political dimensions of the Rohingya issue. It is considered that any long-term national plan in Bangladesh that includes Rohingyas is likely to hinder the government’s repatriation plan, as it might lead the international community to lessen its pressure on Myanmar for quick repatriation of Rohingyas (Khan, 2024). As of now, there has been little international pressure on Myanmar to create a conducive environment for the Rohingya’s voluntary return. Many claim that the geopolitical interests of India and China in Myanmar play a key role in settling the situation (Idris, 2017). China’s vested interest in Myanmar through the “Kyauk Phyu port,” which serves as the starting point for an oil and gas pipeline and other infrastructure projects (Idris, 2017; Lintner, 2017), underscores the political barriers to resolving the Rohingya crisis.

Bangladesh, however, as a small country with limited state capacity in terms of institutional quality and governance (Uddin, 2024), is ill-equipped to indefinitely host over a million refugees. The situation is further complicated by regional pressure, such as India’s citizenship registry in Assam, which has rendered almost 2 million people stateless (Sharma, 2024), many of whom are of Bangladeshi origin and migrated to Assam before the independence of Bangladesh. The “Indira-Mujib pact” was signed on March 19, 1972, which was tactically provided that Bangladesh would not be responsible for persons who had illegally migrated to India before March 25, 1971 (Schendel, 2004, p. 219). This raise concerns that India might adopt a similar approach to Myanmar and push these individuals into Bangladesh, as has occurred with the Rohingya population. The political sensitivity of this issue is heightened by Bangladesh’s historical grant of citizenship to the Urdu-speaking Bihari population, which sets a complex precedent for long-term solutions for Rohingya refugees. Therefore, the government remains apprehensive about the possibility of any local integration of Rohingyas in its society.

Therefore, the spatial (physical) and psychological proximity profoundly influences peaceful coexistence between hosts and refugees. To effectively address the threats between these groups, it is essential to consider both dimensions. Although the government’s relocation of Rohingyas to Bhasan Char has faced criticism due to its geographical location and vulnerability, it inadvertently mitigates the escalating animosity among local residents (Islam and Siddika, 2022) by creating both spatial and psychological proximal distancing that inhibits peaceful coexistence. Given Bangladesh’s socio-economic and political constraints, the government has not designed a long-term refugee policy. Bangladesh’s reluctance to integrate the Rohingya locally is understandable, as the government faces challenges in managing such a substantial strategy that promotes peaceful coexistence between host communities and Rohingya refugees.

7 Conclusion

In order to address the research question of investigating the determining factors influencing peaceful coexistence, this study identifies five main factors behind perceived threats that impede peaceful relations between the host and refugees in Cox’s Bazar, which are: economic, social, political, cultural and environmental factors. As long as these factors are not adequately addressed, the potential for conflict remains high. Despite limited changes in political instability and environmental degradation, the primary challenges revolve around determining the peaceful coexistence of both host communities and refugees, particularly in the economic, social, and cultural dimensions. As a result, host communities frequently perceive the Rohingya as a threat (Siddiqi, 2022) to their social stability, economic resources, and cultural values.

Therefore, the study aligns with arguments emphasizing the impact of proximity in exacerbating intergroup tensions and perceptions of threats. The findings demonstrate that as the spatial (physical) proximal distance between both groups decreases, perceptions of threat from the Rohingya refugees significantly escalate, obstructing the potential for peaceful coexistence. Consequently, both spatial and psychological proximity emerged as pivotal determinants for sustaining peace, thereby managing this proximal distance as a strategy measure for conflict prevention between two groups.

Nevertheless, the meaning of social cohesion as peaceful coexistence between host and refugees in Cox’s Bazar does not imply the social integration of refugees with the host communities per se. It is noteworthy that the current legislative framework for refugee treatment in Bangladesh does not allow any means of local integration of refugees. Therefore, this study underscores the critical importance of managing both spatial and psychological proximity to foster peaceful coexistence between two groups. A notable example of this argument posits the relocation of projected hundred thousand refugees to Bhasan Char, where the increased geographical distancing has contributed to mitigating tensions and alleviating host community resentment. Given the government’s reliance on voluntary repatriation as the ultimate solution, it is critical that interim peace measures remain comprehensive and inclusive, fostering social cohesion and peaceful coexistence.

Therefore, the findings suggest that addressing these proximities requires a conflict-sensitive approach that integrates intergroup relations, addresses root causes of conflict, and considers the unintended consequences of the refugees’ responses to host communities (Woodrow and Chigas, 2009). Relocating refugee camps further from the proximal exposure with host communities could serve as a practical strategy to reduce intergroup exposure and perceived threats, ultimately supporting residential satisfaction of the host population and reducing perceived threats associated with the Rohingya refugees. Although the government of Bangladesh has implemented physical measures such as wired fencing around the camps to limit direct interaction between the host and refugee populations (Khan, 2023), these measures alone are insufficient to address the deeper issues of resource scarcity, political marginalization, and growing local resentment. To foster peaceful coexistence between the hosts and refugees, it will be required to expand of comprehensive skill development programming and formal education to support small entrepreneurship and income-generating activities within the camps. Such initiatives should aim to ensure that Rohingyas do not adversely impact local livelihoods or pose any threats for the host communities.

While this study offers valuable insights into the factors influencing the peaceful coexistence between host and refugees in Cox’s Bazar, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The research was primarily conducted in the subdistricts of Teknaf and Ukhiya, and given the study avoided interviewing Rohingya refugees directly due to the complexity of the situation and the political sensitivities surrounding the treatment of refugees, direct interviews with refugee participants were intentionally excluded. This limits the comprehensiveness of the analysis, as the perspectives of refugees were not directly represented. To achieve a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing peaceful coexistence, future research should broaden its geographical scope with other areas with refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar.

Data availability statement

The interview data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval for this study involving human participants for social research were obtained in accordance with local legislation and the institutional requirements of the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. The study adhered to the ethical principles of research with human participants as outlined by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK) guidelines 2019. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the interviews, and a detailed research notification was presented to all participants.

Author contributions

AK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Despite the fact that the 2017 influx did not recognize the displaced Rohingyas as conventional refugees, this article uses the terms “displaced Rohingyas” and “refugees” interchangeably.

References

Ahmad, S. M., and Naeem, N. (2020). Adverse economic impact by Rohingya refugees on Bangladesh: Some way forwards. Int. J. Soc. Pol. Econ. Res. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.46291/IJOSPERvol7iss1pp1-14

Ansar, A., and Khaled, A. F. (2021). From solidarity to resistance: host communities’ evolving response to the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. J. Int. Humanit. Action 6:16. doi: 10.1186/s41018-021-00104-9

Biswas, B., Mallick, B., Ahsan, N., and Priodarshini, R. (2022). How does the Rohingya influx influence the residential satisfaction and mobility intentions of the host communities in Bangladesh? J. Int. Migr. Integr. 23, 1311–1340. doi: 10.1007/s12134-021-00886-2

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. New York, NY: American Psychological Association.

Chowdhury, R. A. (1995). Repatriation of Rohingya refugees. Colombo: UNHCR’s Regional Consultation on Refugee and Migratory Movements.

Cook, A. D., and Ne, F. Y. (2018). Complex humanitarian emergencies and disaster management in Bangladesh: The 2017 Rohingya exodus. Singapore: Centre for Non Traditional Security Studies (NTS Centre).

Fonseca, X., Lukosch, S., and Brazier, F. (2019). Social cohesion revisited: a new definition and how to characterize it. Innovation: Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 32, 231–253. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2018.1497480

Given, L. M. (2008). Nonprobability sampling. SAGE Encycl. Qualitative Res. Methods 1, 562–563. doi: 10.4135/9781412963909

Grossenbacher, A. (2020). Social cohesion and peacebuilding in the Rohingya refugee crisis in Cox’s bazar, Bangladesh. KOFF. Available at: https://koff.swisspeace.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/2021CaseStudyBangladesh.pdf (Accessed July 17, 2023).

Habib, M. R. (2023). Rohingya refugee–host community conflicts in Bangladesh: issues and insights from the “field”. Dev. Pract. 33, 317–327. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2022.2090516

Habib, M. R., and Roy Chowdhury, A. (2023). The Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: conflict with the host community over natural resources in Cox’s bazar district. Area Dev. Policy 8, 263–273. doi: 10.1080/23792949.2023.2193246

Halim, M. A., Rinta, S. M., Amin, M. A., Khatun, A., and Robin, A. H. (2021). The environmental implications of the rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh. Asian J. Environ. Ecol. 16, 189–203. doi: 10.9734/ajee/2021/v16i430269

Hashim, S. M. (2019). Socio-economic impacts of the Rohingya influx. The daily star (newspaper). Available at https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/no-frills/news/socio-economic-impacts-the-rohingya-influx-1782133 (Accessed August 17, 2024).

Hoque, M. M. (2021). Forced labour and access to education of Rohingya refugee children in Bangladesh: Beyond a humanitarian crisis. J. Sci. 6, 20–35. doi: 10.22150/jms/PPJY4309

Idris, I. (2017). Rohingya crisis: impact on Bangladeshi politics. K4D Helpdesk Report 233. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

International Crisis Group . (2023). Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: limiting the damage of protracted crisis. Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar-bangladesh/rohingya-refugees-bangladesh-limiting-damage-protracted (Accessed December 12, 2023).

Islam, L. (2024). “Exploring post-settlement social dynamics and conflict between the host community and Rohingyas” in Understanding the Rohingya displacement: Security, media, and humanitarian perspectives. eds. K. Ahmed and M. R. Islam (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 49–63.

Islam, M. R., and Haque, M. M. (2024). Repatriation of Rohingya refugees: prospects and challenges. Understanding Rohingya Displ. Secur. Media Hum. Persp. 12, 257–273. doi: 10.1007/978-981-97-1424-7_15

Islam, M. D., and Siddika, A. (2022). Implications of the Rohingya relocation from Cox’s bazar to Bhasan char, Bangladesh. Int. Migr. Rev. 56, 1195–1205. doi: 10.1177/01979183211064829

Islam, M. T., Sikder, S. K., Charlesworth, M., and Rabbi, A. (2023). Spatial transition dynamics of urbanization and Rohingya refugees’ settlements in Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 133:106874. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106874

Joireman, S. F., and Haddad, F. (2023). The humanitarian–development–peace Nexus in practice: building climate and conflict sensitivity into humanitarian projects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 62:101272. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2023.101272

Kamruzzaman, P., Kabir, M. E., and Siddiqi, B. (2024). “Representation of forcibly displaced Rohingyas in Bangladeshi newspapers” in The displaced Rohingyas. eds. M. D. Landry and A. Tupetz (New Delhi: Routledge India), 198–222.

Khan, A. K. (2023). “Constrained humanitarian space in Rohingya response: views from Bangladeshi NGOs” in Civil society responses to changing civic spaces. eds. K. Biekart, T. Kontinen, and M. Millstein (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 191–213.

Khan, A. K. (2024). Envisioning the humanitarian-development-peace nexus in the Rohingya response in Bangladesh: implementation challenges and suggestions for the future. Dev. Policy Rev. 42:12803. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12803

Khan, A. K., and Kontinen, T. (2022). Impediments to localization agenda: humanitarian space in the Rohingya response in Bangladesh. J. Int. Humanit. Action 7:14. doi: 10.1186/s41018-022-00122-1

Kim, J., Sheely, R., and Schmidt, C. (2020). Social capital and social cohesion measurement toolkit for community-driven development operations. Washington, DC: Mercy Corps and The World Bank Group.

Kudrat-E-Khuda, B. (2020). The impacts and challenges to host country Bangladesh due to sheltering the Rohingya refugees. Cogent Soc. Sci. 6:1770943. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2020.1770943

Lewis, D. (2019). Humanitarianism, civil society and the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh. Third World Q. 40, 1884–1902. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2019.1652897

Lewis, J. S., and Topal, S. A. (2023). Proximate exposure to conflict and the spatiotemporal correlates of social trust. Polit. Psychol. 44, 667–687. doi: 10.1111/pops.12864

Lintner, B. (2017). The world will soon have a new terror hub in Myanmar if the Rohingya crisis isn’t tackled well, QUARTZ (economics). Available at: https://qz.com/india/1088213/the-world-will-soon-have-a-new-terror-hub-in-myanmar-if-the-rohingya-crisis-isnt-tackled-well. (Accessed August 2, 2024).

Masum, S. J. H. (2021). “Mapping the development effectiveness of the triple nexus approach in a protracted refugee context: the case of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh” in Localizing the triple nexus: A policy research on the humanitarian, development, and peace Nexus in nine contexts. eds. S. Barakat and S. Milton (Quezon: CSO Partnership), 50–75.

Meem, M. I. (2024). “Social cohesion and integration of Rohingyas in the host Community in Bangladesh” in Understanding the Rohingya displacement: Security, media, and humanitarian perspectives. eds. K. Ahmed and M. R. Islam (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 241–255.

Mohiuddin, M., and Molderez, I. (2023). Rohingya influx and host community: A reflection on culture for leading socioeconomic and environmental changes in Bangladesh. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy. 13:11559. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.11559

OECD (2012). “Social cohesion and development” in Perspectives on global development 2012: Social cohesion in a shifting world. ed. O. E. C. D. Headquarters (Paris: OECD Publishing).

Olney, J., Badiuzzaman, M., and Hoque, M. A. (2019). Social cohesion, resilience and peace building between host population and Rohingya refugee community in Cox’s bazar, Bangladesh.

Rahman, U. (2010). The Rohingya refugee: A security dilemma for Bangladesh. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 8, 233–239. doi: 10.1080/15562941003792135

Rahman, H., Rahman, M., and Rahman, E. (2019). Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh: Socio-cultural issues and challenges of national and regional security. The Jahangirnagar Review, Jahangirnagar University. Faculty of Social Sciences (Part II, Social Science, Vol. XLIII), 321–342.

Sakib, A. N. (2023). Rohingya refugee crisis: emerging threats to Bangladesh as a host country? J. Asian Afr. Stud. 12:00219096231192324. doi: 10.1177/00219096231192324

Sattar, Z. (2019). Rohingya crisis and the host community. The financial express. Available at: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/reviews/rohingya-crisis-and-the-host-community-1564498784 (Accessed February 12, 2024).

Schendel, W. V. (2004). The Bengal borderlands: beyond state and nation in South Asia. London: Anthem Press.

Schwandt, T. A. (2000). “Three epistemological stances for qualitativeinquiry: Interpretivism, hermeneutics, and social constructionism” in Handbook of qualitative research. eds. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. 2nd ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 189–213.

Sengupta, I. (2021). An agenda for a dignified and sustainable Rohingya refugee response in Bangladesh. Sydney: Act for peace.

Sharma, C. (2024). National register of citizens Assam, India: the tangled logic of documentary evidence. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 22, 225–237. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2021.2018084

Siddiqi, B. (2022). Challenges and dilemmas of social cohesion between the Rohingya and host communities in Bangladesh. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:944601. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.944601

Siddiqi, B., and Kamruzzaman, P. (2021). Policy challenges towards Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh: the role of national development experts. Available at: https://pure-test.southwales.ac.uk/ws/files/5832139/Siddiqi_and_Kamruzzaman2021Policy_Challenges_towards_the_Rohingya_Crisis_in_BD.pdf (Accessed July 1, 2024).

Siddiqi, B., Kamruzzaman, P., and Kabir, M. E. (2024). “Living in uncertainty: vulnerable Rohingya in Bangladesh” in The displaced Rohingyas. eds. B. Siddiqi and M. R. Bhuiyan (New Delhi: Routledge India), 77–93.

Stephan, W. G., and Stephan, C. W. (2000). “An integrated threat theory of prejudice” in Reducing prejudice and discrimination (Lawrence Erlbaum Associatesf: Mahwah, NJ), 23–45.

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., and Morrison, K. R. (2009). “Intergroup threat theory” in Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination. ed. T. D. Nelson (London: Psychology Press), 43–59.

Sultana, Z. (2023). Impact of Rohingya influx on host community’s relations to places in Bangladesh. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 93:101782. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101782

Uddin, N. (2024). Understanding ‘refugee resettlement’ from below: decoding the Rohingya refugees’ lived experience in Bangladesh. World Dev. 181:106654. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2024.106654

Uddin, M. A., Islam, T., Anjum, I., Rayhan, I., and Miah, A. S. M. J. (2021). Social cohesion between the Rohingya and host communities in Cox’s bazar. Dhaka: Advocacy for Social Change (ASC), BRAC.

Ullah, S. A., Asahiro, K., Moriyama, M., and Tani, M. (2021). Socioeconomic status changes of the host communities after the Rohingya refugee influx in the southern coastal area of Bangladesh. Sustain. For. 13:4240. doi: 10.3390/su13084240

Woodrow, P., and Chigas, D. (2009). A distinction with a difference: conflict sensitivity and peacebuilding. Collaborative for Development Action. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/distinction-difference-conflict-sensitivity-and-peacebuilding (Accessed September 2, 2023).

Keywords: Rohingya refugees, peaceful coexistence, threat, host community, proximity, social (de-)cohesion, Bangladesh

Citation: Khan AK (2024) A critical analysis of the factors influencing peaceful coexistence between Rohingya refugees and host communities in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Front. Hum. Dyn. 6:1457372. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2024.1457372

Edited by:

Bulbul Siddiqi, North South University, BangladeshReviewed by:

Nur Newaz Khan, North South University, BangladeshMd. Touhidul Islam, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

Copyright © 2024 Khan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdul Kadir Khan, bXVyYWRkZC5raGFuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Abdul Kadir Khan, orcid.org/0000-0003-2492-8463

Abdul Kadir Khan

Abdul Kadir Khan