- Master Program in Sociology, Department of Culture, Politics and Society, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

1 Introduction

The establishment of mutual trust between Ukrainian refugees and the Swiss state has become increasingly relevant amidst global migration dynamics and the substantial influx of Ukrainian refugees driven by ongoing military conflict. Given the significant number of Ukrainian refugees who have been residing in Switzerland for extended periods, there is an urgent need to establish effective communication between Swiss governmental institutions and this population, as well as to develop comprehensive long-term integration strategies. This endeavor is complicated by the protracted nature of the conflict in Ukraine and the uncertainty surrounding the potential return of refugees to their homeland. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the long-term challenges faced by both Ukrainian refugees and Swiss society and to explore viable solutions to address these issues effectively.

Switzerland is not bound by EU Council Directive 2001/55/EC of 20 July 2001 on minimum standards for giving temporary protection (European Union, 2001). It has implemented similar measures under its own national asylum legislation that reflect the key principles of the directive. Status S grant's Ukrainian refugees rights to residence, employment, education, and access to social and medical services. According to the Circular Cantonal Integration Programs 2024–2027 and the Swiss Integration Agenda (PIC 3), dated October 19, 2022, refugees from Ukraine are encouraged to actively engage in Swiss social and professional life through integration programs, education, and paid employment, allowing them to maintain and develop their skills (Federal Department of Justice and Police, 2024).

Historical experience demonstrates that temporary protection can evolve into long-term residency, as was the case with refugees from the former Yugoslavia in the 1990's, many of whom chose to remain in Switzerland even after the situation in their home country stabilized. In 2003, Swiss citizenship was granted to 12,000 Yugoslavs (Gross, 2006). “In 2001, the number of returning nationals was at its lowest level since the mid-1980's (<3,500 people in column 6) and it is falling rapidly. In parallel, the number of acquisitions of Swiss nationality was at its highest ever with almost 12,000 in 2003, which represented 1/3 of all naturalizations, much more than its representation in the foreign population (columns 7 and 7′)” (1). Similarly, a significant number of Ukrainian refugees, faced with ongoing instability in Ukraine, do not plan to return to their country. A survey conducted by the UNHCR, SEM, and the market research firm Ipsos indicates that repatriating Ukrainian refugees voluntarily may be challenging. One-third of the Ukrainian refugees surveyed expressed that they do not wish to return to their homeland, while 40% remain undecided (UNHCR and Ipsos SA, 2023; UNHCR, 2024b).

The theoretical foundation of this article is grounded in Alexander's (2004) concept of cultural trauma, which explores how the long-term psychological effects of historical events, particularly those marked by ethnic and racial violence, can be transformed into universal symbols of human suffering and moral transgression. Alexander extends the traditional understanding of trauma by introducing cultural trauma, a phenomenon that transcends individual experiences and impacts the collective identity of entire societies. Cultural trauma, as defined by Alexander (2004), arises when a group perceives itself as having endured a catastrophic event that leaves a lasting imprint on their collective memory, fundamentally reshaping their shared identity and social fabric. Smelser (2004) explores the relationship between psychological trauma and cultural trauma, emphasizing how both affect collective memory.

The article integrates the social capital theories of Putnam (2000), Coleman (1990), and Bourdieu (1986), focusing on the significance of networks, norms, trust and social cohesion in fostering integration. Consistent with Wagner's (2014) research on social capital among immigrants, the integration of refugees into both bonding social capital (within ethnic networks) and bridging social capital (connections with the host society) is critical for achieving long-term integration outcomes. Wagner (2014) underscores that bonding capital addresses immediate needs by providing support within ethnic communities, whereas bridging capital facilitates upward mobility and deeper participation in the host society. Additionally, research demonstrates that both forms of social capital are positively correlated with subjective wellbeing, underscoring the role of social support networks in enhancing life satisfaction among immigrant populations (Wagner, 2014).

However, refugees from countries with high levels of corruption and weak governance face additional challenges in integrating into host countries. Rothstein and Uslaner (2006) emphasizes that corruption erodes institutional trust, weakening social cohesion and undermining collective action. This dynamic is particularly relevant for Ukrainian refugees, many of whom have developed deep distrust toward governmental structures due to their negative experiences with corruption in their home country. As a result, rebuilding trust in the institutions of the host country—such as those in Switzerland—becomes a complex and critical component of the integration process. The transference of institutional distrust may hinder the refugees' ability to fully engage with and benefit from the host country's support structures, thus complicating their integration.

The primary aim of this article is to draw attention to the academic community's need for further research into the transference of institutional distrust from Ukraine to Swiss governmental institutions among Ukrainian refugees. This article also seeks to address gaps in the literature on temporary protection and institutional trust, while laying the groundwork for the development of sustainable long-term integration strategies that are sensitive to the specific needs of Ukrainian refugees. These strategies should not only support successful integration but also help preserve social cohesion within the host society, aligning with the broader goals outlined in the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation: “Switzerland shall promote the common welfare, sustainable development, internal cohesion and cultural diversity of the country” (2) (Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, 1999, Art. 2).

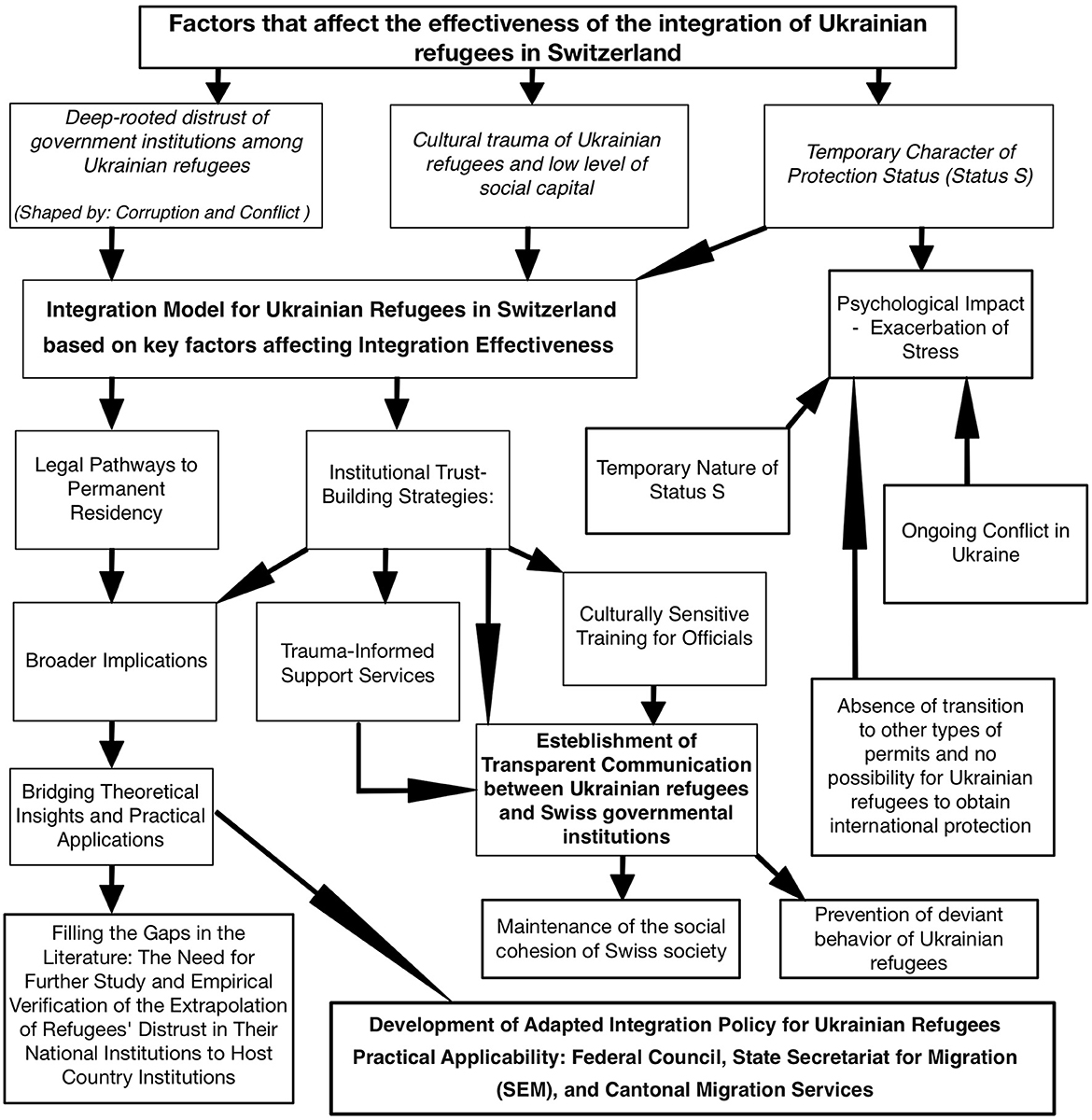

Central to this article is the author's conceptual model, which integrates the principles of trust, transparency, and cultural sensitivity as foundational pillars of refugee integration strategies (Figure 1). This model is intended to enhance communication, mitigate institutional distrust, and create a more inclusive and supportive environment for Ukrainian refugees. By strengthening social cohesion and promoting adaptability, the model provides a versatile framework that can be adapted to various national contexts facing the challenges of integrating refugees under temporary protection measures.

Figure 1. Comprehensive author's model for the effective integration of Ukrainian refugees in Switzerland: strategies for building trust and transparent communication.

2 Methodology

This study employs a theoretical approach to develop a conceptual integration model specifically designed for Ukrainian refugees residing in Switzerland under temporary protection (Status S; State Secretariat for Migration, 2023). The research methodology involves a comprehensive and rigorous analysis of existing literature, drawing upon interdisciplinary theoretical frameworks. These frameworks are utilized to address the unique challenges of institutional distrust and the complex dynamics of refugee integration in the host society.

2.1 Limitations of the study

The primary limitation of this study lies in its theoretical nature. While the proposed model is grounded in a thorough analysis of existing literature, its practical applicability has not yet been empirically tested. As such, the model's effectiveness in real-world settings remains hypothetical and requires validation through future empirical research. Additionally, the focus on Ukrainian refugees under temporary protection may limit the generalizability of the model to other refugee populations with different legal statuses or cultural contexts.

3 Theoretical framework

Institutional trust refers to the confidence and expectations that citizens have regarding the actions of government and social institutions. It reflects the belief that these institutions will act according to their responsibilities, adhere to norms and laws, and contribute to public welfare (Rothstein and Stolle, 2008). This trust is fundamental to maintaining social cohesion and ensuring the effective functioning of democratic societies. Institutional trust significantly influences social interactions, citizens' willingness to cooperate with authorities, and their participation in public life (Hardin, 2002). When institutional trust is high, societal stability and wellbeing are enhanced, creating an environment that is predictable, stable, and under control. Conversely, a decline in trust can lead to alienation, social isolation, and decreased civic engagement, potentially destabilizing the social structure (Rothstein and Stolle, 2008).

In societies with high institutional trust, citizens are more likely to believe that government institutions act in their best interest and protect their rights (Rothstein and Stolle, 2008). This trust, both between individuals (interpersonal trust) and in institutions (institutional trust) are a decisive determinant of economic growth, social cohesion and wellbeing. It is also a crucial component for policy reform and for the legitimacy and sustainability of any political system (Algan, 2018).

Trust is not only a vital element of institutional stability but also a fundamental component of social capital. Social capital, which refers to the networks, norms, and trust that enable members of a society to coordinate and cooperate for mutual benefit, is strengthened by high levels of trust. In turn, strong social capital enhances economic development and the quality of governance (Algan, 2018). According to Yann Algan, a high level of trust contributes to the development of social capital, which further facilitates societal functioning by reducing transaction costs and enabling collective action. This relationship between social capital and trust is mutually reinforcing: high levels of trust build social capital, which further supports trust. Conversely, low levels of trust can erode social capital, leading to weaker institutions and diminished social cooperation.

The case of post-Soviet countries offers a poignant example of this dynamic. In post-Soviet countries, social capital, which encompasses norms of trust and social interaction, was significantly undermined during the transitional period following the collapse of the Soviet Union (Habibov et al., 2017). This erosion led to a decline in trust in governmental institutions, further exacerbating the spread of corruption (Habibov et al., 2017). Ukrainian refugees coming from countries with low levels of social capital and high levels of corruption, building trust in new government institutions is a significant challenge (Uslaner, 2008). When social capital is eroded, as is often the case in conflict-ridden and repressive environments, refugees may struggle to integrate and trust even those institutions that demonstrate high levels of transparency and accountability (Portes, 1998). It's also important to consider that war, displacement, persecution, and associated trauma disrupt social networks, social cohesion and norms, undermining trust in authority and outsiders (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al., 2014).

3.1 The role of social capital in the adaptation of Ukrainian refugees: trust dynamics and integration challenges

The study “Unseen Glue: Social Capital in Ukraine,” conducted by the Sociological Group “Rating” with the support of USAID and implemented by Chemonics International Inc., sheds light on critical aspects of social capital in the context of war and its impact on Ukrainian society.

The close circle (family, friends, and colleagues) is the main source of trust for Ukrainians. According to the study, 96% of respondents trust their immediate family members, 68% trust relatives, and 60% trust friends (Sociological Group “Rating”, 2023). These figures emphasize the importance of family and friendship bonds, which play a crucial role in the adaptation process for Ukrainian refugees. Support from family and friends helps manage the challenges of relocation and provides both emotional and practical assistance, which is critical in the context of forced migration.

However, despite the importance of trust within the close circle, the study revealed a significant lack of trust toward strangers and people of other nationalities. According to the results, 58% of Ukrainians do not trust strangers, and 44% express distrust toward people of other nationalities (Sociological Group “Rating”, 2023). These findings underscore the existence of social barriers that may complicate the integration of refugees into new countries. Distrust of people from other cultures can make it harder to form new social connections, which is an essential factor for successful integration into host societies.

Another important aspect of the study is the low level of trust in government institutions. Only 32–33% of respondents trust state and municipal bodies, while 34–35% express distrust (Sociological Group “Rating”, 2023). This low level of trust may negatively affect refugees' perception of government support systems in host countries. If refugees are inclined to avoid interaction with governmental institutions, it could hinder their access to necessary resources and slow down the adaptation process.

Thus, social capital plays a key role in supporting Ukrainian refugees. Family and friendship ties are vital sources of stability during crises, but integration into new societies can be complicated by distrust of strangers and government structures. For successful adaptation, it is essential to create conditions that foster the development of new social connections and build trust between refugees, host communities, and government institutions.

3.2 The impact of cultural trauma and cognitive distortions on perception of Swiss governmental institutions

“We don't see everything. Some of the information we filter out is actually useful and important. Our search for meaning can conjure illusions. We sometimes imagine details that were filled in by our assumptions, and construct meaning and stories that aren't really there. Quick decisions can be seriously flawed. Some of the quick reactions and decisions we jump to are unfair, self-serving, and counter-productive. Our memory reinforces errors. Some of the stuff we remember for later just makes all of the above systems more biased, and more damaging to our thought processes” (3) (Benson, 2022).

Cultural trauma and cognitive distortions are deeply intertwined in shaping the perceptions and behaviors of individuals who have experienced significant collective suffering. Alexander (2004) defines cultural trauma as the profound psychological and collective damage inflicted on a community by catastrophic events such as wars, genocide, or systemic injustice. This trauma embeds itself in collective memory, significantly influencing how individuals within the affected community perceive and react to their environment (Mollica et al., 1992).

This cultural trauma can lead to a persistent and deep-seated distrust of any authoritative structures, even in a stable and democratic environment like Switzerland. The memories of past tragedies continue to influence how refugees perceive new institutions, often leading them to see these institutions not as protectors, but as potential threats. This enduring mistrust is further compounded by cognitive distortions, which are systematic errors in thinking that often arise under stress or trauma (Beck, 1976). According to Kelly's Personal Construct Theory (Kelly, 1955) individuals develop anticipatory cognitive attitudes based on prior experiences. These attitudes help form schemas, which Kelly defined as mental structures or frameworks created from past experiences. These schemas are used to organize and categorize new information and experiences. They facilitate the processing of novel events by helping individuals identify familiar patterns, suggesting where to look for additional information, and providing default interpretations when perception is incomplete (Zaiden et al., 2023).

Refugees who have faced violence and systemic injustice may be prone to cognitive distortions such as catastrophizing (expecting the worst possible outcome), overgeneralization (believing that negative experiences are likely to happen in all similar situations), and personalization (feeling that negative events are specifically targeted at them; Friedman, 2023). These distortions skew their perception of reality, making them more likely to misinterpret even minor bureaucratic delays or challenges as signs of impending injustice or betrayal (Hynie, 2018).

The interplay between cultural trauma and cognitive distortions establishes a feedback loop wherein past experiences and present anxieties mutually reinforce each other, leading to a deepening distrust of new institutions. This dynamic poses significant challenges to the integration of refugees into their host society, as they may exhibit reluctance to fully engage with institutions they perceive as potentially threatening, despite clear evidence to the contrary. A thorough understanding of this complex interaction is vital for the development of targeted support systems designed to address both the psychological sequelae of trauma and the cognitive distortions that result from it. Such interventions are not only critical for facilitating successful and harmonious integration but also for preventing deviant behavior, alleviating the burden on social services, and safeguarding the social cohesion of a democratic and transparent host society.

3.3 Stress factors associated with temporary character of protection status

“While the Temporary Protection Directive has been praised for its success in providing immediate assistance to millions, uncertainty remains about what will happen once it ends. One option that has recently gained attention is to further prolong temporary protection beyond March 2025. It may seem straightforward to simply extend temporary protection by another year, yet this may create some important challenges beyond deferring longer term decisions.” (4) (Wagner, 2014).

The temporary protection status (Status S) granted to Ukrainian refugees in Switzerland, characterized by its provisional nature and the lack of direct pathways to permanent residency, combined with the ongoing uncertainty of the conflict in Ukraine, presents several significant stress factors that may affect the wellbeing and integration of refugees. By its nature, Status S creates an environment of uncertainty regarding the long-term future of refugees in Switzerland. Research in psychology indicates that uncertainty can be a substantial source of stress, particularly for individuals who have already experienced significant trauma and displacement (Miller and Rasmussen, 2017). The Swiss Federal Council has indicated that Status S will remain valid until stability is restored in Ukraine, which is not expected in the near future due to the ongoing conflict (Federal Council, 2023).1 This situation may hinder refugees' ability to make long-term plans, affecting decisions related to education, employment, and family life.

The current framework lacks options for transitioning from temporary protection to permanent residency, which contributes to a sense of instability among refugees. This situation limits their opportunities for full social and economic participation, leading to feelings of isolation and negatively affecting their trust in host country institutions (Koser and Pinkerton, 2002; Portes, 1998). Additionally, the unpredictable nature of the conflict in Ukraine adds further complexity to the situation. The lack of clarity regarding the end of hostilities and the possibility of returning home increases the psychological burden on refugees, as they navigate the challenges of adapting to life in a new country while facing an uncertain future. This ongoing uncertainty directly impacts their ability to fully engage in the integration process. The combination of these factors—temporary protection status, lack of alternative residency pathways, and conflict-related uncertainty—heightens stress among Ukrainian refugees. To support the wellbeing of refugees and facilitate their integration, it is essential to explore policy adaptations tailored to the specific circumstances of the Ukrainian situation.

“The uncertainty about developments in the war and its implications for the duration of the refugee situation requires that the Nordic countries shift to more forward-looking policies. A discussion is needed about potential changes and extensions to the status of refugees from Ukraine and about an integration strategy for them in the long-term. More long-term responses should also involve better matching of Ukrainian refugees' skills and labor-market needs in order to help new arrivals find quality jobs and avoid skills being wasted.” (5) (Nordic Council of Ministers and UNHCR, 2022).

4 Socio-institutional dynamics

The Federal Department of Justice and Police (FDJP) of the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) has released the Asylum Statistics for 2022 indicating that Switzerland has faced one of the most significant refugee influxes in decades (State Secretariat for Migration, 2022). Nearly 25,000 individuals applied for asylum, in addition to ~75,000 Ukrainian refugees who were granted protection under the newly activated Status S, introduced for the first time (State Secretariat for Migration, 2022). In response to these active migration flows and the activation of temporary protection status [Asylum Act of 26 June 1998. Article 66(1). Policy decision of the Federal Council; Swiss Confederation, 1999]. Switzerland developed systems for efficient communication between refugees and social institutions. Consequently, centers for rapid registration of Ukrainian refugees (Swiss Confederation, 2022) were established, along with the provision of essential aid, specialized support services, information resources, integration programs, and streamlined management of migration-related bureaucratic procedures (State Secretariat for Migration, 2022). The implementation of temporary protection allowed for expedited registration of Ukrainian refugees, avoiding the prolonged procedures typically associated with international protection applications.

Currently, Ukrainians under Temporary Protection Status S have been residing in Switzerland for over 2 years. During this period, they have been integrating into Swiss society, learning the local languages, and actively participating in the labor market, either by seeking employment or securing jobs. As their time in Switzerland progresses, many Ukrainian refugees are considering pathways for full integration, including transitioning other types of residence permits that are currently unavailable (Asylum Act, 1998) due to the temporary nature of the Council Directive 2001/55/EC (European Union, 2001) and the temporary nature of the protection status in Switzerland.

According to a survey conducted by the UNHCR Office for Switzerland and Liechtenstein in collaboration with Ipsos SA in Switzerland in December 2023 (UNHCR and Ipsos SA, 2023) 21% of Ukrainian respondents are currently employed. Additionally, ~29% identified themselves as unemployed but actively seeking work, while 21% are engaged in professional training or courses. Notably, 50% of those employed reported that their current job is at a lower skill level compared to their previous employment in Ukraine. Furthermore, the survey revealed that 69% of respondents possess at least a university-level education, with 32% holding a master's degree or higher, indicating that Ukrainian refugees are highly educated and demonstrate significant integration potential as skilled migrants (International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2019).

Despite the high educational qualifications and proactive efforts of Ukrainian refugees to integrate into Swiss society, unemployment remains a persistent challenge. The temporary nature of Status S does not provide employers with sufficient assurance regarding the long-term employability of Ukrainian refugees once the temporary protection period concludes. This uncertainty contributes to increased anxiety among refugees, places additional pressure on social services to provide financial support, and leads employers to adopt risk-averse strategies due to the absence of guarantees and a clear framework for integrating Ukrainian refugees into the labor market.

In response, the Federal Council has set a target of increasing the employment rate among Ukrainian refugees from the current level of ~20–40% by the end of 2024 (Federal Council, 2023). The FDJP, in collaboration with the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research (EAER), the cantons, and social partners, is working on developing and implementing additional targeted measures to achieve this goal. According to the Federal Council (2023), “Bern, 01.11.2023—The situation in Ukraine is not expected to change in the foreseeable future. The Federal Council therefore decided at its meeting on 1 November not to lift the protection status S for Ukrainian refugees before 4 March 2025. For the first time, it has also defined a target for labor market integration: By the end of 2024, 40% of persons capable of employment with protection status S should be in work.” (6) (Federal Council, 2023). As of now, the most recent available data on the employment rate among Ukrainian refugees is from November 1, 2023.

Future research should prioritize the examination of updated data on the employment and integration of Ukrainian refugees in Switzerland under temporary protection status. This research should encompass a comprehensive assessment of labor market participation, socio-economic outcomes, and the effectiveness of integration initiatives, with particular attention to the impact of temporary protection status on employment stability and social inclusion. Additionally, it is essential to explore how evolving policy frameworks and support mechanisms influence the successful integration of refugees into both Swiss society and the workforce.

4.1 Institutional trust dynamics. The influence of Corruption Perception of institutional trust: examining Ukrainian refugees' trust in governmental institutions

According to Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index for 2023, Ukraine scored 36/100 and ranked 104th out of 180 countries, reflecting a significant level of perceived corruption. In contrast, Switzerland received a score of 82/100 ranking 6th globally and placing it among the least corrupt nations in the world (Transparency International, 2023). These pronounced disparities in corruption perception are likely to influence the expectations of Ukrainian refugees in their interactions with Swiss governmental institutions. Refugees originating from a context where corruption is systemic may exhibit an inherent skepticism toward state institutions, which could shape their initial levels of trust or distrust in Swiss authorities. This preconditioned skepticism may lead to altered expectations concerning institutional transparency, fairness, and reliability, thereby potentially impacting their integration trajectories and the overall effectiveness of host-country support mechanisms (Heidinger, 2021).

Given that Ukrainian refugees are migrating from a country characterized by a high level of perceived corruption to one of the least corrupt nations globally, it becomes imperative to tailor social and integration programs to address the specific mindset shaped by such environments. This context calls for the development of innovative approaches to foster communication between Ukrainian refugees and Swiss governmental institutions. Key strategies should include appointing public relations officers, establishing cultural exchange platforms, utilizing digital communication channels, implementing robust feedback mechanisms, actively involving Ukrainian refugees in the decision-making process, and developing comprehensive educational programs to inform refugees of their rights. Additionally, culturally sensitive training for officials is essential to ensure effective interaction with refugees. These measures are designed to promote mutual understanding, enhance trust in institutions, and support the successful integration of refugees into Swiss society, while acknowledging their previous experiences with corrupt and ineffective institutions.

To further illustrate this issue, reference is made to the all-Ukrainian public opinion survey “Omnibus,” conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) between November 29 and December 9, 2023 (Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 2023). This survey monitors trust dynamics in key state institutions from 2021 to 2023. The findings reveal a growing criticism of Ukrainian authorities, with trust in the Verkhovna Rada decreasing from 35% in December 2022 to 15% in December 2023, while distrust increased from 34 to 61%. Similarly, trust in the government declined from 52 to 26%, accompanied by a rise in distrust from 19 to 44%. These trends underscore the significant challenges Ukraine faces in fostering transparent and accountable governance, a critical element in its trajectory toward EU integration.

4.2 Comparative context: Switzerland institutional trust dynamic

For a comparative analysis, data from the “Government at a Glance 2021” report, which provides reliable and internationally comparable indicators on government activities and outcomes across OECD countries, is examined (OECD, 2021). The analysis particularly focuses on Switzerland's performance, as outlined in the 2021 Country Fact Sheet: Switzerland (OECD, 2021). According to the report, confidence in the national government in Switzerland is the highest among OECD countries, with 85% of Swiss respondents reporting trust in their government in 2020, significantly exceeding the OECD average of 51%. This high level of trust highlights the effectiveness of Switzerland's governance structures, offering a valuable benchmark for understanding governance challenges in other nations, including Ukraine.

5 The process of resocialization of Ukrainian refugees in Switzerland within the framework of new social norms and institutional standards

Exposure to a minimally corrupt environment such as Switzerland provides a unique opportunity for Ukrainian refugees to reconstruct their perceptions of how a society oriented toward collective wellbeing functions and to witness first-hand how government institutions operate effectively (OECD, 2023). Resocialization within such a context is essential for reinforcing social cohesion and institutional trust while providing Ukrainian refugees with a deeper understanding of how efficient governmental systems function. As defined by the Cambridge Dictionary, resocialization involves the process of discarding old behavioral patterns and adopting new ones as part of a significant life transition (Cambridge University Press, 2024). In the case of Ukrainian refugees, this resocialization is a critical component of their adaptation, as they transition from a society characterized by corruption and low institutional trust to the transparent and well-regulated environment of Switzerland (Khan, 2021).

For successful integration, Ukrainian refugees must internalize the new norms, values, and regulations of Swiss society, fully embracing European standards of governance and societal interaction. Nevertheless, this process of resocialization is challenging and requires time, as well as collaborative efforts between the refugees and Swiss governmental, public, and social institutions. The adaptation process is further complicated by the specific social orders and trust dynamics2 that characterize countries with high levels of corruption, which often differ significantly from the governance principles and norms present in Switzerland. These disparities can hinder the acceptance of new institutional frameworks and prolong the resocialization process for refugees accustomed to less transparent governmental systems.

The integration of Ukrainian refugees into Switzerland, recognized as one of the least corrupt nations globally, can be facilitated by enhancing mutual trust between refugees and Swiss governmental institutions. This can be achieved through initiatives such as roundtable discussions, continuous monitoring, and surveys, which ensure that Ukrainian refugees feel their voices are heard and that they are actively involved in decision-making processes.

To mitigate the intragroup stress experienced by Ukrainian refugees due to the temporary nature of protection under Status S, it is crucial to develop a comprehensive action plan that addresses their long-term prospects beyond the expiration of temporary protection status. This plan should include clearly defined pathways for transitioning to alternative residency statuses in Switzerland, thereby providing a more stable and predictable framework for their long-term integration.

6 Recommendations for adapting migration programs for Ukrainian Refugees

In adapting migration programs to effectively support the integration of Ukrainian refugees, it is essential to consider several critical factors that address the unique challenges faced by this population. Below are key recommendations that should be integrated into these programs to ensure their success.

6.1 Addressing cultural trauma and cognitive distortions

6.1.1 Trauma-informed support services

Migration programs must incorporate trauma-informed care that recognizes the profound impact of cultural trauma and cognitive distortions on refugees. These services should include specialized training for social workers, educators, and healthcare providers to identify and address symptoms of trauma such as heightened vigilance, mistrust, and anxiety. By providing targeted support that addresses these psychological barriers, programs can facilitate more effective integration and help refugees build trust in their new environment (Knezevic and Olson, 2014; Alexander et al., 2004; Kelly, 1955).

6.1.2 Culturally sensitive counseling and support

Access to culturally sensitive counseling services is crucial in helping refugees process their traumatic experiences and mitigate the effects of cognitive distortions. These services should be designed to respect and accommodate the cultural backgrounds of refugees, thereby aiding their adjustment to the new environment and fostering trust in Swiss institutions (Hynie, 2018).

6.2 Reducing stress associated with temporary protection status

6.2.1 Pathways to permanent residency

To alleviate the uncertainty associated with temporary protection status (Status S), it is recommended to establish clear legal pathways for transitioning from temporary protection to permanent residency. Providing refugees with the opportunity to apply for permanent residency after a specified period of residence in Switzerland can reduce the stress and instability caused by the temporary nature of their current status. In countries like Germany, where legal pathways to permanent residency were provided to Syrian refugees, there was a marked increase in labor market participation, reflecting the importance of legal stability for integration. For instance, a report by the OECD (2017) underscores that legal pathways to permanent residency significantly improved labor market participation among Syrian refugees, demonstrating the importance of stable legal status for effective integration. Such examples underline the necessity of similar adaptations in Swiss migration programs.

6.2.2 Support for long-term planning

Offering refugees guidance on long-term planning, including education, employment, and family life, is essential in reducing the stress related to the uncertainty of their future. This support should include comprehensive information on available opportunities and resources as well as counseling services that assist refugees in making informed decisions despite the ongoing political situation in Ukraine. For example, in Norway, structured long-term planning programs have been shown to significantly enhance refugees' abilities to integrate into the labor market and educational systems, resulting in higher employment rates and educational attainment among refugee populations (UNHCR, 2021). Long-term planning support will enable refugees to better adapt and integrate into Swiss society, enhancing their prospects for successful social and economic participation.

6.3 Building institutional trust and enhancing social capital

6.3.1 Transparent communication and engagement

To build institutional trust, migration programs should prioritize transparent communication about government policies and processes. This can be achieved by providing clear, consistent information to refugees regarding their rights, the status of their protection, and any potential changes in their legal standing. Furthermore, involving refugees in decision-making processes related to their integration can foster a sense of agency and inclusion, which are vital for rebuilding social capital (Strang and Quinn, 2021).

6.3.2 Community engagement initiatives

Strengthening social capital among refugees can be facilitated through community engagement programs that encourage interaction between refugees and local Swiss communities. These initiatives should aim to build support networks, promote participation in local events, and foster connections that help refugees fully integrate into society. Such programs are instrumental in reducing social isolation and building mutual trust between refugees and the host community.

7 Model for increasing institutional trust in the Swiss government

Basic model to increase the level of institutional trust of Ukrainian refugees in the Swiss government apparatus (vertical trust) (UNDP, 2021).

7.1 Active involvement

Active involvement of Ukrainian refugees in decision-making processes and oversight of the activities of government institutions will create a sense of responsibility and transparency. Also it can strengthen intergroup relation based on Intergroup Contact Theory (IGCT) between Ukrainian refugees and Swiss governmental institutions (Allport, 1954).

7.2 Improving the level of information

Improving the level of information on the rights and responsibilities of Ukrainian refugees, as well as the functioning of government institutions based on Temporary Protection Status S, will contribute to building interpersonal and institutional trust between Ukrainian refugees and Swiss institutions (Kwon, 2019).

7.3 Enhancing openness in the work

Enhancing openness in the work of Swiss government institutions toward Ukrainian refugees. This may include the public disclosure of information on decisions, budgets, further programs, and procedures: conditions for transitioning to other types of residence permits in Switzerland after the expiration of the temporary status S (State Secretariat for Migration, 2023).

The model requires empirical validation, which can be conducted through bilateral survey methods, allowing for an assessment of the effectiveness of the proposed strategies in strengthening institutional trust among Ukrainian refugees toward Swiss governmental institutions. To empirically validate the proposed model, it would be essential to conduct bilateral surveys both among Ukrainian refugees and Swiss governmental officials. These surveys should focus on assessing changes in trust levels and the effectiveness of communication initiatives, such as the proposed community liaison officers and digital platforms. This empirical approach will not only confirm the model's effectiveness but also offer insights into further refinement.

8 Strategies for enhancing communication between Ukrainian refugees and Swiss institutions

In addition to strategies aimed at trust-building (generalized social trust), enhancing communication between Ukrainian refugees and Swiss institutions is crucial for fostering integration and mutual understanding (Sturgis et al., 2012). The proposed model encompasses the following components:

8.1 Cultural sensitivity training

Implementing cultural sensitivity training for Swiss government officials and frontline staff who interact with Ukrainian refugees. This training should emphasize understanding Ukrainian culture, history, and the refugee experience, enabling more empathetic and effective communication (Bhugra, 2017; Kowalski, 2023).

8.2 Community liaison officers

Appointing community liaison officers within Swiss institutions to serve as dedicated points of contact for Ukrainian refugees. These officers can facilitate communication, address concerns, and provide essential information about available resources and services, thereby enhancing support and integration efforts.

8.3 Cultural exchange programs

Organizing cultural exchange programs and events that bring Ukrainian refugees and Swiss locals together. These initiatives promote cross-cultural understanding, dismantle stereotypes, and foster positive relationships between refugees and the broader Swiss community (Berry, 2005).

8.4 Digital communication platforms

Creating digital communication platforms, such as online forums or mobile applications, where Ukrainian refugees can easily access information, ask questions, and receive updates from Swiss institutions. These platforms ensure accessible and timely communication, particularly for those who may encounter barriers to in-person interactions (Diaz Andrade and Doolin, 2016).

“The lessons from the Ukraine crisis are that digital technologies are deeply intertwined with migration, not only at the individual level, but also in terms of the relations between migrants, State actors and non-State actors, both within the country and at international levels. These technologies can have transformational effects on migrants' lives, in some cases enhancing their capabilities and empowering them in ways not observed in the past. Supporting the development of these capabilities while also limiting the negative impacts of these technologies will involve a concerted effort on the part of the international community in terms of the governance of digital public goods, platform services and dual-use technologies. The digital lives of migrants in Ukraine are complex and nuanced, but they demonstrate opportunities and risks that will likely only be more present in upcoming crises, as the boundaries between the physical and the digital become even more blurred” (7) (Thinyane et al., 2023).

8.5 Community feedback mechanisms (CFMs)

Introducing feedback mechanisms that enable Ukrainian refugees to share their insights on the effectiveness of communication strategies and the responsiveness of Swiss institutions. This approach ensures that communication efforts are aligned with the needs and preferences of the refugee population, fostering continuous improvement and adaptability (Nevill, 2022).

“Community Feedback Mechanisms (CFMs) are key to ensuring that people affected by crisis have access to avenues to hold humanitarian actors to account. They offer a formalized structure for people to share suggestions, ideas and concerns in regard to the delivery of humanitarian services” (8) (Nevill, 2022).

9 Key goals for strengthening social unity and refugee integration

These models will contribute to maintaining social cohesion in Swiss society by promoting mutual understanding and cooperation between Ukrainian refugees and Swiss institutions (UNHCR, 2024a). Consequently, the following objectives will be accomplished:

9.1 Building interpersonal and institutional trust

By offering education, informing Ukrainian refugees about the core principles of Swiss political and social systems, and ensuring access to relevant information, the model enhances trust among Ukrainian refugees in Swiss institutions. This approach reduces mistrust toward government entities and diminishes the inclination to withhold information from social services (Kwon, 2019).

9.2 Preventing deviant behavior (Durkheim's Anomie theory)

Refugees often arrive in a new country with high, and sometimes unrealistic, expectations. When these expectations are unmet, some may turn to criminal activities as a means of bridging the gap between their aspirations and the realities they encounter. This phenomenon can be understood as a response to the disparity between anticipated opportunities and actual available resources. Enhanced communication and improved access to resources have been shown to lower the likelihood of deviant behavior among Ukrainian refugees. By providing comprehensive information about Swiss norms and legal frameworks, these initiatives help refugees align their behavior with local standards and expectations, thereby reducing the probability of engaging in activities considered deviant and an escape mechanism (Merton, 1938; Simmler et al., 2017).

9.3 Promoting communication and openness

Increasing communication and openness in Swiss public institutions reduces the probability that Ukrainian refugees will feel the need to hide information. By making procedures and ways of seeking assistance clear and accessible, the model ensures that refugees are less likely to resort to deceptive practices of implementing behavioral patterns of corruption.

9.4 Facilitating resocialization and adaptation

This approach supports the resocialization of Ukrainian refugees by equipping them with essential information and resources to navigate Swiss society effectively. By fostering understanding and cooperation, it enhances their ability to integrate into Swiss society and improves the overall processes of adaptation and resocialization within a new socio-cultural environment.

These models are essential for establishing an integration process that promotes the sustainable and long-term adaptation of Ukrainian refugees, facilitating their successful entry into the social, economic, and cultural structures of Swiss society. They create the conditions for effective interaction between refugees and governmental institutions, strengthening trust and ensuring efficient communication. This, in turn, helps reinforce social cohesion and contributes to the wellbeing of both refugees and the host society. Moreover, considering the widespread application of Directive 2001/55/EC across Europe, these models can be adapted to support the integration of Ukrainian refugees in other European countries facing similar challenges, offering a flexible and multi-layered framework for improving integration processes, building trust, and fostering effective communication.

10 Ethical and social considerations

In developing and proposing this integration model, significant attention has been paid to the ethical responsibility and social impact it may have on both Ukrainian refugees and the host society. Ethical considerations include respect for cultural differences, the protection of human rights, and the ethical engagement of refugees in decision-making processes. The model also aims to foster social cohesion and can be adapted for use in other contexts facing similar challenges, with careful attention to potential implementation barriers.

11 Conclusions

This study has identified and thoroughly analyzed the primary challenges faced by Ukrainian refugees during their integration into Swiss society, with a specific focus on the transfer of institutional distrust from their home country to the governmental institutions of the host country. By leveraging the theoretical frameworks of cultural trauma and social capital, this research elucidates how prior experiences with corruption and conflict complicate the establishment of trust in Swiss governmental institutions, particularly under the temporary protection status (Status S).

The findings underscore the critical importance of enhancing trust through the implementation of transparent communication systems, active refugee involvement in decision-making processes, and culturally sensitive training for government officials. Additionally, the proposed development of legal pathways to permanent residency is highlighted as a crucial measure to alleviate the psychological stress associated with the temporary nature of protection status, thus contributing to a more stable and secure integration process.

While the proposed strategies and models are aimed at significantly improving integration processes, certain key aspects require further in-depth analysis. Specifically, the phenomenon of transferring institutional distrust merits additional empirical investigation. Despite this study's substantial contribution to understanding the dynamics of trust within the context of migration and refugee integration, this area remains insufficiently explored in the academic literature. Future research, particularly through longitudinal and cross-sectional studies, is essential for empirically validating the proposed model and assessing its practical effectiveness.

In conclusion, this study addresses a critical gap in the literature concerning temporary protection and institutional trust, offering practical strategies to improve refugee integration processes. Although the proposed model requires further empirical validation and adaptation to evolving circumstances, its implementation holds significant potential for enhancing integration outcomes, reducing distrust, and strengthening social cohesion within host societies. Moreover, the principles underlying this model can be adapted to various national contexts facing similar challenges in integrating Ukrainian refugees under temporary protection, providing a robust foundation for developing more inclusive and sustainable integration strategies across Europe.

Author contributions

VH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Federal Council. Last modified November 1, 2023. The Federal Council has therefore decided not to lift protection status S until 4 March 2025 unless the situation changes fundamentally before then. This decision provides clarity not only for the Ukrainian refugees, but also for the cantons, the communes and employers. In view of Switzerland's Schengen membership, the Federal Council considers it vital to coordinate closely with the EU, which decided on 19 October to extend temporary protection to Ukrainian refugees until 4 March 2025.

2. ^Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) indicates that compared to December 2022, criticism of the authorities is growing. In particular, the share of those who trust the Verkhovna Rada decreased from 35 to 15%, and the share of those who do not trust it increased from 34 to 61%. Trust in the Government decreased from 52 to 26%, distrust increased from 19 to 44%.

References

Alexander, J. C. (2004). “On the social construction of moral universals: the “Holocaust” from war crime to trauma drama,” in Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, eds. J. C. Alexander, R. Eyerman, B. Giesen, N. J. Smelser, and P. Sztompka (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 196–263.

Alexander, J. C., Eyerman, R., Giesen, B., Smelser, N. J., and Sztompka, P. (2004). Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Algan, Y. (2018). “Trust and social capital,” in OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust. Paris: OECD. Available at: https://www.yann-algan.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Algan-2018_Ch.-10-Trust-and-Social-Capital_OECD.pdf (accessed September 7, 2024).

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Available at: https://ia601500.us.archive.org/17/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.188638/2015.188638.The-Nature-Of-Prejudice.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

Asylum Act (1998). Federal Act on Asylum Procedures. Art. 69 Para. 3. Available at: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1999/358/en#art_66 (accessed September 8, 2024).

Benson, B. (2022). Cognitive Bias Cheat Sheet. Better Humans. Available at: https://betterhumans.pub/cognitive-bias-cheat-sheet-55a472476b18 (accessed September 7, 2024).

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 29, 697–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

Bhugra, D. (2017). Cultural competence training and mental health care in refugees and asylum seekers. Eur. Psychiat. 41:166. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.166

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. J. G. Richardson (New York, NY: Greenwood Press), 241–258. Available at: https://home.iitk.ac.in/~amman/soc748/bourdieu_forms_of_capital.pdf (accessed September 6, 2024).

Cambridge University Press (2024). Resocialization. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/resocialization (accessed September 8, 2024).

Diaz Andrade, A., and Doolin, B. (2016). Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. MIS Quart. 40, 405–416. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.2.06

European Union (2001). Council Directive 2001/55/EC of 20 July 2001 on Minimum Standards for Giving Temporary Protection in the Event of a Mass Influx of Displaced Persons and on Measures Promoting a Balance of Efforts Between Member States in Receiving Such Persons and Bearing the Consequences Thereof . Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2001/55/oj (accessed September 8, 2024).

Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation (1999). Title 1: General Provisions, Art. 2 Aims. Status as of 3 March 2024. Available at: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1999/404/en#art_2 (accessed September 7, 2024).

Federal Council (2023). Policy on Employment for Ukrainian Refugees. Available at: https://www.admin.ch/gov/en/start/documentation/media-releases.msg-id-98405.html (accessed September 8, 2024).

Federal Department of Justice and Police (2024). Program “Support measures for individuals with protection status S” (Program S). State Secretariat for Migration SEM, Integration Division, Circular II, 1 January, 1–8. Available at: https://www.sem.admin.ch/dam/sem/it/data/integration/foerderung/programm-s/rundschreiben-2-programm-s.pdf.download.pdf/rundschreiben-2-programm-s-i.pdf (accessed September 6, 2024).

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E., Loescher, G., Long, K., and Sigona, N. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Friedman, H. (2023). Overcoming Cognitive Distortions: How to Recognize and Challenge the Thinking Traps that Make You Miserable. Koppelman School of Business, Brooklyn College, City University of New York. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.31209.47208

Gross, D. M. (2006). Immigration to Switzerland: The Case of the Former Republic of Yugoslavia. Washington DC: World Bank. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/656711468120841053/pdf/wps38800rev0pdf.pdf (accessed September 6, 2024).

Habibov, N., Afandi, E., and Cheung, A. (2017). Sand or grease? Corruption-institutional trust nexus in post-soviet countries. J. Euras. Stud. 8, 172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.euras.2017.05.001

Heidinger, E. (2021). Overcoming Barriers to Service Access: Refugees' Professional Support Service Utilization and the Impact of Human and Social Capital. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, No. 1151. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW). Berlin. Available at: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/248566/1/1780066880.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

Hynie, M. (2018). The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: a critical review. Can. J. Psychiat. 63, 297–303. doi: 10.1177/0706743717746666

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2019). Glossary on Migration, International Migration Law No. 34. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available at: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf (accessed September 16, 2024).

Kelly, G. A. (1955). The Psychology of Personal Constructs. Vol. 1: A Theory of Personality; Vol. 2: Clinical Diagnosis and Psychotherapy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Khan, A. (2021). Resocialization of immigrants. Int. J. Law Manag. Human. 4, 516–523. doi: 10.1732/IJLMH.26091

Knezevic, B., and Olson, S. (2014). Counseling people displaced by war: experiences of refugees from the former Yugoslavia. Prof. Counselor 4, 316–331. doi: 10.15241/bkk.4.4.316

Koser, K., and Pinkerton, C. (2002). The Social Networks of Asylum Seekers and the Dissemination of Information about Countries of Asylum. Research Development and Statistical Unit of Home Office, London.

Kowalski, S. (2023). Cultural Sensitivity Training: Developing the Basis for Effective Intercultural Communication, econcise GmbH.

Kwon, O. Y. (2019). Social Trust and Economic Development: The Case of South Korea. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 22–32. doi: 10.4337/9781784719609

Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (2023). Dynamics of Trust in Social Institutions in 2021–2023. Available at: https://www.kiis.com.ua/?lang=eng&cat=reports&id=1335&page=1 (accessed September 8, 2024).

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social Structure and Anomie. American Sociological Review. 3, 678. Available at: https://www.csun.edu/~snk1966/Robert%20K%20Merton%20-%20Social%20Structure%20and%20Anomie%20Original%201938%20Version.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

Miller, K. E., and Rasmussen, A. (2017). The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: an ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 26, 129–138. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000172

Mollica, R. F., Caspi, Y., Bollini, P., and Tor, S. (1992). The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 180, 107–111. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008

Nevill, J. (2022). Community Feedback Mechanism: Guidance and Toolkit. Danish Refugee Council (DRC). Available at: https://pro.drc.ngo/media/f4li0lon/drc_global-cfm-guidance_web_low-res.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

Nordic Council of Ministers and UNHCR (2022). Implementation of Temporary Protection for Refugees From Ukraine: A Systematic Review of the Nordic Countries. Available at: https://pub.norden.org/nord2022-026/# (accessed September 8, 2024).

OECD (2017). Labour Market Integration of Refugees in Germany. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/labour-market-integration-of-refugees-in-germany_14947519-en (accessed September 8, 2024).

OECD (2021). Government at a Glance 2021. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/government-at-a-glance-2021_1c258f55-en (accessed September 8, 2024).

OECD (2023). Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi: 10.1787/e13bef63-en

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 24, 1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Rothstein, B., and Stolle, D. (2008). The state and social capital: an institutional theory of generalized trust. Compar. Polit. 40, 441–459. doi: 10.5129/001041508X12911362383354

Rothstein, B., and Uslaner, E. M. (2006). All for All: Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. QOG Working Paper Series 2006:4. The QoG Institute, University of Gothenburg. Available at: https://www.gu.se/sites/default/files/2020-05/2006_4_Rothstein_Uslaner.pdf (accessed September 6, 2024).

Simmler, M., Plassard, I., Schär, N., and Schuster, M. (2017). Understanding pathways to crime: can anomie theory explain higher crime rates among refugees? Current findings from a Swiss Survey. Eur. J. Crim. Pol. Res. 17:4. doi: 10.1007/s10610-017-9351-4

Smelser, N. J. (2004). “Psychological trauma and cultural trauma,” in Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, 1st Edn, eds. J. C. Alexander, R. Eyerman, B. Giesen, N. J. Smelser, and P. Sztompka (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 31–59. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pp9nb (accessed September 6, 2024).

Sociological Group “Rating” (2023). Unseen Glue: Social Capital in Ukraine. Conducted by the Sociological Group “Rating”, Supported By USAID, Chemonics International Inc. Available at: https://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/report_ua_fin.pdf (accessed September 7, 2024).

State Secretariat for Migration (2022). Foreign National and Asylum Statistics 2022. Available at: https://www.sem.admin.ch/dam/sem/en/data/publiservice/statistik/bestellung/auslaender-asylstatistik-2022.pdf.download.pdf/auslaender-asylstatistik-2022-e.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

State Secretariat for Migration (2023). Permit S (People in Need of Protection). Available at: https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/en/home/themen/aufenthalt/nicht_eu_efta/ausweis_s__schutzbeduerftige.html (accessed September 7, 2024).

Strang, A. B., and Quinn, N. (2021). Integration or isolation? Refugees' social connections and wellbeing. J. Refugee Stud. 34, 328–353. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fez040

Sturgis, P., Patulny, R., Allum, N., and Buscha, F. (2012). Social Connectedness and Generalized Trust: A Longitudinal Perspective. ISER Working Paper Series, 2012-19, 1–22. Available at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1559&context=lhapapers (accessed September 8, 2024).

Swiss Confederation (1999). Federal Act on Foreign Nationals and Integration (FNIA). of 16 December 2005 (Status as of 1 January 2023). Available at: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1999/358/en (accessed September 8, 2024).

Swiss Confederation (2022). Register Me. Available at: https://registerme.admin.ch/start (accessed September 8, 2024).

Thinyane, M., Fournier-Tombs, E., and Molinario, G. (2023). The Digital Dynamics of Migration: Insights from the Ukrainian Crisis. Migration Research Series No. 78. IOM. Available at: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/pub2023-033-r-the-digital-dynamics-of-migration.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

Transparency International (2023). Corruption Perception Index 2023. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023 (accessed September 8, 2024).

UNDP (2021). Trust in Public Institutions: A Conceptual Framework and Insights for Improved Governance Programming. UNDP Oslo Governance Centre. Available at: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/oslo_governance_centre/Trust-in-Public-Institutions-Policy-Brief_FINAL.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

UNHCR (2021). UNHCR Recommendations to Norway for Strengthened Refugee Protection in Norway, Europe and Globally. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/neu/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2021/11/UNHCR-Recommendations-to-Norway-Nov-21.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

UNHCR (2024a). Integration Handbook for Resettled Refugees: Promoting Welcoming and Inclusive Societies. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/dach/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2023/12/20231213_Survey-Intentions-and-perspectives-of-refugees-from-Ukraine-in-Switzerland.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

UNHCR (2024b). Lives on Hold: Intentions and Perspectives of Refugees, Refugee Returnees and IDPs from Ukraine. Regional Intentions Report #5. Summary Findings. February. Available at: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/106738 (accessed September 6, 2024).

UNHCR and Ipsos SA (2023). Survey on Employment and Education of Ukrainian Refugees in Switzerland. Conducted by the UNHCR Office for Switzerland and Liechtenstein in Collaboration With Ipsos SA. December 2023. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/dach/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2023/12/20231213_Survey-Intentions-and-perspectives-of-refugees-from-Ukraine-in-Switzerland.pdf (accessed September 8, 2024).

Uslaner, E. M. (2008). Corruption, Inequality, and the Rule of Law: The Bulging Pocket Makes the Easy Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wagner, B. F. (2014). Trust: The Secret to Happiness? Exploring Social Capital and Subjective Well-Being among Immigrants. M.A. Applied Social Research, Queens College. Available at: https://paa2014.populationassociation.org/papers/142867 (accessed September 6, 2024).

Keywords: The Federal Department of Justice and Police (FDJP) of the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), temporary protection status S, Asylum Act of June 26, 1998, institutional trust dynamics, Swiss governmental institutions, Ukrainian refugees, integration programs, transparent communication

Citation: Hett V (2024) Towards mutual trust and understanding: establishing effective communication between Ukrainian refugees and Swiss government institutions. Front. Hum. Dyn. 6:1445749. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2024.1445749

Received: 08 June 2024; Accepted: 11 September 2024;

Published: 02 October 2024.

Edited by:

James C. Simeon, York University, CanadaReviewed by:

Syeda Naushin, University of Malaya, MalaysiaCopyright © 2024 Hett. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valeriia Hett, dmFsZXJpYWhldHRAZ21haWwuY29t

†Present address: Valeriia Hett, Doctorate Program in Migration Studies, Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

Valeriia Hett

Valeriia Hett