95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 11 March 2025

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2024.1426605

This article is part of the Research Topic Unraveling Human Trafficking Dynamics Amidst Mixed Migration and Global Crises View all 3 articles

Sasha Baglay1*

Sasha Baglay1* Idil Atak2

Idil Atak2The article discusses the challenges of data collection in the context of anti-human trafficking efforts in Canada. It aims to identify existing statistical data from government sources and stimulate discussions around data accuracy and availability. The analysis indicates that the available data predominantly focuses on crime-related statistics, highlighting the need for improved data practices. The article’s conceptual framework emphasizes open government as crucial for democratic governance, advocating for data availability and Access to Information (ATI) regimes that promote transparency and empower public engagement. It stresses that reliable data is vital for evidence-based policymaking, particularly in Canada, where responses to human trafficking have often been largely rhetorical and enforcement-centric. Structured in four parts, the article first outlines international standards for data collection on human trafficking. It then situates the research within open government principles, discusses the specific complexities of data reporting in Canada, and shares insights from the authors’ data collection experiences through ATI requests. The conclusion raises critical questions to guide future efforts in enhancing data collection and reporting processes related to human trafficking.

Accountable, transparent and responsive policy-making are essential to good governance (OHCHR, 2024). Anti-human trafficking policies should be no exception, but data collection and reporting in this field remains challenging and incomplete. In this article, we tackle these complex issues in Canadian context. The main objectives of our study are: (a) to identify what statistical data is currently available from government sources and through access to information (ATI) requests; and (b) to prompt a conversation about data availability and accuracy.

The Canadian government does not publish yearly comprehensive reports on human trafficking. Rather, the information can be found in the following key sources: Statistics Canada; Canada’s National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking (2012–16); National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking (2019–24); and Public Safety Canada reports on the progress in implementation of the Action Plan and of the Strategy. In addition, a foreign source - the United States (US) Trafficking in Persons reports (sections on Canada)—contains yearly statistics on law enforcement and protection of survivors. Our analysis draws on these publicly available sources as well as statistics from federal, provincial, and municipal authorities obtained through ATI requests. We demonstrate that most of the data is crime-focused (charges, prosecutions, convictions, survivors identified in criminal process), piecemeal, and often lacks longitudinal scope. We urge the authorities to take steps towards critical analysis of human trafficking data practices and to develop a framework for improved collection and reporting.

The conceptual framework for this article focuses on the notion of open government as the cornerstone of democracy. Data availability and ATI regimes serve a pivotal role, aiming not only to foster government transparency and accountability but also to empower the public with insights into government administration. The importance of data availability cannot be overstated, particularly in the context of evidence-based policy-making. Reliable and accurate reporting of data enhances the capacity of policymakers to develop strategies that are grounded in empirical evidence, rather than ideological or rhetorical positions. This is especially significant in Canada, where governmental responses to human trafficking have often leaned towards rhetoric-driven solutions that predominantly focus on sex trafficking and prioritize law enforcement (Roots et al., 2024; Millar et al., 2017; Timoshkina, 2012, 2014; Millar and O’Doherty, 2020).

The article is in four parts. Part One outlines international guidance and practices on data collection and reporting on human trafficking. In Part Two, we contextualize our research within the framework of open government. Part Three introduces the readers to the complexities of data collection and reporting specific to Canada. In Parts Four and Five, we discuss the nature of publicly available information on human trafficking and share our experiences of data collection through ATI requests. We conclude by identifying questions that should inform future efforts in the development of data collection and reporting processes.

Before we proceed, important caveats are in order. First, we are not suggesting that more data is always better or that accumulation of more data automatically leads to more transparent and evidence-based policies. Neither are we arguing that the key problem in Canada’s anti-human trafficking initiatives is the lack of data. While we say that data is incomplete, our main point is that it is reported in a piecemeal and inconsistent manner, raising questions as to why gaps and discrepancies among sources exist. We recognize the challenges stemming from survivor identification, prosecution of trafficking and politicized discourse on human trafficking—each having an impact on how cases are classified and subsequently counted in statistics. Thus, statistics always must be viewed through a critical lens with an awareness that the numbers do not tell the full story and that they may be either underreported or inflated. Second, while we discuss largely crime-focused data, this does not mean that we are endorsing a law enforcement focused approach or suggest that more prosecutions are the evidence of success of anti-human trafficking policies. As stated above, our objective is to identify what statistical data is reported, and since current data is crime-centered so is our discussion. Third, the focus of our study is on government sources and statistical information only; the discussion of estimates or reporting by non-governmental organizations is outside our scope. Fourth, we recognize that the problematic nature of the mainstream anti-human trafficking discourse lies at the root of current limitations in data collection and accuracy. While the topic of how to change this discourse is beyond this paper to address, we hope that critical conversations on human trafficking data can at least incrementally contribute to this change. Against this background, our study involves mapping the publicly available official statistical data to identify which indicators are reported and assessing whether gaps in these sources can be addressed through ATI requests. This systematic approach will help us better understand the current landscape of human trafficking data and facilitate the identification of critical information that may be lacking.

There is no one single international instrument outlining guiding principles and methodologies for the collection and reporting of data on human trafficking. Rather, guidance can be drawn—albeit in a piecemeal fashion—from several sources as well as international/regional practices. As discussed below, these sources project a consensus that data collection is essential for the development and evaluation of evidence-based anti-human trafficking policies. They also identify the key types of data to be collected and publicly reported on a regular basis.

The main international treaty on human trafficking – the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (Trafficking Protocol) – does not contain detailed provisions on States Parties’ obligations with respect to data collection. However, its importance can be implied from several articles of the Protocol. Article 9(1) requires states to establish comprehensive policies and programs to prevent and combat human trafficking and to protect survivors. Arguably, the development of such policies would not be possible without knowing the scope and nature of the issue, past and current trends, and profile and needs of survivors. Article 9(2) further specifies that States Parties “shall endeavor to undertake measures such as research… to prevent and combat trafficking in persons.” Article 10 requires States Parties to cooperate with one another by exchanging information on cross-border human trafficking, including the means, methods and routes used by traffickers.

Several international guidelines emphasize the importance of data collection to support evidence-based policies. The Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking (OHCHR, 2002) issued by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights state: “Effective and realistic anti-trafficking strategies must be based on accurate and current information, experience and analysis” (Guideline 3). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2009) similarly recognizes that systematic collection and analysis of data is essential: first, in order to increase understanding of human trafficking and of the trends and patterns at national and international levels; and second, to set baselines against which to assess the progress of national anti-human trafficking initiatives (p. 7). The Framework identifies evidence-based approach as one of the key guiding principles for anti-human trafficking action: “Policies and measures to prevent and combat trafficking in persons should be developed and implemented based on data collection and research and regular monitoring and evaluation of the anti-trafficking response” (2009, p. 9). The implementation of other guiding principles—although not explicitly referring to data collection—appears to also be contingent on data availability. For example, gender-sensitive approach requires addressing similarities and differences in the trafficking experiences and vulnerabilities of women and men as well as of the differential impact of policies on men and women. These experiences and differential impacts cannot be properly understood without disaggregated data collection. The principle of sustainability of anti-trafficking responses—their endurance over time and ability to adapt to changing conditions—also hinges on the availability of up-to-date data on human trafficking trends. The 2010 Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons further reaffirmed the commitment to “[c]onduct research and collect suitably disaggregated data that would enable proper analysis of the nature and extent of trafficking in persons (para. 16)” and vowed “to strengthen the capacity of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime to collect information and report biennially…on patterns and flows of trafficking in persons at the national, regional and international levels in a balanced, reliable and comprehensive manner” (para. 60).

The importance of data collection and reporting in anti-trafficking initiatives has also been underlined by regional organizations. In the European Union, for instance, the Anti-Trafficking Directive mandated, among other things, that Member States establish national rapporteurs or equivalent mechanisms to gather statistics on human trafficking, assess trends and measure results of anti-trafficking actions (Art 19). This information is transmitted to the EU anti-trafficking coordinator and forms the basis for the European Commission’s reports on human trafficking. Further, the EU Strategy on Combating Trafficking in Human Beings (2021–25) identified among key priorities the improvement of data recording and collection to ensure reliable and comparable information for policy-making (European Commission, 2021).

The above sources also offer some guidance on the types of data to be collected. The UN Framework (2009) establishes the following indicators for each prong of the anti-human trafficking strategy and urges collection of respective statistics on them:

• Prosecution: number of investigations and prosecutions of human trafficking; number of charges and convictions; number of specialized units on human trafficking investigations and specialized criminal justice practitioners.

• Protection: number of identified survivors; number of survivors who accessed supports and services; number of survivors that participated in criminal proceedings; number of survivors who received compensation; number of internationally trafficked persons who benefited from a period of reflection and who obtained residence permits; number of internationally trafficked persons who were informed of the right to request asylum and who were granted refugee status or subsidiary protection.

• Prevention: number of trafficked persons detected at a state’s border; number of officers trained to detect trafficked persons; and number of referrals to the asylum procedure.

Furthermore, the Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking (OHCHR, 2002) urge states to ensure that the data on trafficked persons is disaggregated by age, gender, ethnicity and other relevant characteristics.

The leading international/regional reports on human trafficking demonstrate what indicators are currently being reported on. The UN Global Reports on Trafficking in Persons (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020) focus on global and regional trends (without detailed country statistics) with respect to identified survivors (by age, gender, form of exploitation and citizenship), investigations, prosecutions and convictions as well as characteristics of convicted traffickers (age, gender, trafficking structure and type of exploitation exacted from trafficked persons). The US Trafficking in Persons (TIP) reports typically include data on the number of investigations, charges, prosecutions and convictions and the number of survivors, including foreign nationals, but provide no detailed breakdown by age, gender, citizenship, or forms of exploitation.1 The European Commission and Eurostat report on the numbers of registered survivors (with breakdown by form of exploitation, gender, age and citizenship) and the number of traffickers who were suspected, prosecuted and convicted (with breakdown by age, gender, citizenship and form of exploitation exacted from survivors) (European Commission, 2020). The Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA), which evaluates implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, requests from States Parties even more detailed statistics, including the number of: presumed victims (i.e., those that have not been formally recognized by state authorities as victims of trafficking), recipients of assistance, recipients of temporary resident permits, survivors who made asylum claims and who received refugee protection, survivors who claimed compensation and who received it, survivors who were repatriated (all with breakdowns by gender, age, citizenship and form of exploitation) (GRETA, 2023).

While international/regional guidance speaks to the crucial role of data collection and reporting, it does not define the term ‘data’. The above discussed reports demonstrate that ‘data’ tends to be understood in a narrow sense as statistical data. While the reports usually include a narrative account of trends or an evaluation of states’ anti-human trafficking initiatives, those narratives are tied to statistics. This approach creates a need to open the discussion about the meaning of ‘data’ and the place of qualitative information (such as experiences of survivors and service providers) in it. Statistical data reveals only a very partial picture of human trafficking and, arguably, cannot be understood or critically assessed without qualitative accounts.

In our analysis of the accessibility and accuracy of data collection and reporting on human trafficking in Canada, we underscore the critical role of open government policies within democratic frameworks (Head, 2010). Wirtz and Birkmeyer (2015) define open government as “a multilateral, political, and social process, which includes in particular transparent, collaborative, and participatory action by government and administration” (p. 384). They note open government’s role in enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of governmental and administrative action (Wirtz and Birkmeyer, 2015, p. 384).

In an open government, the public has the ability to monitor and impact governmental processes by accessing government information (Meijer et al., 2012). Transparency is therefore a fundamental aspect of open government, ensuring timely public access to government information and enabling the public to monitor, scrutinize and assess the internal workings of governmental organizations (Lourenço, 2023, p. 3). As noted by Lourenço (2023), lack of information impedes meaningful public engagement and debate as well as decision-making (p. 2). Information availability and accessibility is important not only for policy-formation and civilian oversight, but also for maintaining public confidence in those policies (Steets and OAPEN Foundation, 2010, p. 25).

The main purpose of open government initiatives has been to strengthen the accountability of government agencies to the public (Wirtz and Birkmeyer, 2015, p. 384). Accountability can be defined as the obligation of government and/or public administration to account for their activities, accept responsibility for them, and to disclose results in a transparent manner (Wirtz and Birkmeyer, 2015, p. 391). According to Schedler, the main connotation of political accountability is answerability, the obligation of public officials to inform about and to explain what they are doing (Schedler, 1999, p. 14). In a similar vein, Bovens et al. (2014) define accountability as the obligation to provide answers to those with a legitimate demand for explanation. They view accountability as a relational concept, forming connections between agents and individuals for whom they carry out tasks or who are impacted by those tasks (pp. 6–7).

Open government policies encourage the utilization of government data for social or economic benefits. In fact, access to information enriches civic knowledge and contributes to the understanding of governance mechanisms and reinforcing democratic procedures. Access to information is recognized for its role in promoting social justice (Luscombe and Walby, 2017, p. 380). Duncan et al. (2023) emphasize that “Open government policies are motivated by desires to disincentivize corruption through transparency, the creation of social and economic value using government data, and to encourage participatory and collaborative forms of democracy” (p. 47). Open and transparent government is interrelated with evidence-based policy-making, which is considered to enable better informed, reasoned and effective policies (Pankhurst, 2017).2 Evidence-based policymaking requires the capacity to collect quality data, availability of such data, interaction and openness of communication among researchers and coordination among participating institutions (Riddell, 2007). Without transparency, it is not possible to know what evidence was used and how it was used to inform policy; open government standards set criteria for the quality of the information that is collected (Steet and OAPEN Foundation, 2010). Transparency also ties into the participatory nature of open government whereby researchers and other non-governmental actors may contribute to the policy process. Pettrachin and Hadj Abdou (2024) contend that ‘knowledge transfers’ between core decision-makers and knowledge producers, such as academia, NGOs, and think tanks can also help address information gaps. Researchers and advocates can also promote a more critical analysis of the data itself, its utilization, and gaps in information serving as a check against inaccurate, manipulative or self-serving data use. However, as noted by Luscombe and Walby (2017), issues with information availability and accessibility negatively impact researchers’ ability “to filter through [the information], interpret it, and communicate the findings to the public in accurate and meaningful ways” (p. 383).

In sum, collection and reporting of data on human trafficking is important for at least two reasons: first, it supports evidence-based policymaking, helping enhance both the legitimacy and effectiveness of those policies (Adam et al., 2018); second, it promotes transparency of the policy process (Head, 2010), contributing to open government. The principles of evidence-based policy-making and open government are incorporated throughout Canada’s government structures. For example, the 2022–24 National Action Plan on Open Government includes a commitment to making data available to the public and ensuring it is easy to use and understand (Government of Canada, 2024a). The Directive on Open Government (2014) requires federal departments and agencies to maintain comprehensive inventories of data and to maximize the release of government data to the public. Furthermore, the Cabinet Directive on Regulation incorporates a principle that regulatory decision-making be evidence-based: “proposals and decisions are based on evidence, robust analysis of costs and benefits, and the assessment of risk, while being open to public scrutiny” (Government of Canada, 2024b). The current National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking (2019) acknowledges these points: “Research capacity will be enhanced to expand the knowledge-base of human trafficking, close data gaps and inform policy and program initiatives over the five-year National Strategy.” The next section discusses the current state of this knowledge base on human trafficking.

The lack of an effective data collection system has been consistently highlighted as one of the gaps in Canada’s anti-trafficking efforts (Roots and De Shalit, 2015; Millar et al., 2017; Timoshkina, 2014; Millar and O’Doherty, 2020; Statistics Canada, 2010). Academic literature discussed various challenges to data gathering and analysis both in Canada and internationally. First, it points to the clandestine nature of human trafficking that often impedes the determination of its actual magnitude (Van Dijk and Campistol, 2018; Aronowitz, 2010).

Second, data may be incomplete or unreliable due factors such as uneven attention to different types of human trafficking (e.g., priority to sex trafficking rather than labour trafficking), conflation of sex work and human trafficking, criminalization of survivors, inadequate victim identification, and a tendency to view internationally trafficked persons as ‘merely’ smuggled migrants (Aronowitz, 2010; Farrell and Reichert, 2017). These factors can contribute to both underreporting and overreporting of human trafficking cases. Underreporting may occur when trafficked individuals fail to be recognized as such, often due to a lack of awareness or understanding of their victimization. Conversely, overreporting can happen when individuals, such as sex workers, are mistakenly or deliberately classified as trafficking victims. For example, the criminalization of survivors who are foreign nationals working without authorization in Canada creates significant barriers to identification efforts. Many foreign nationals may fear detention and deportation, which discourages them from seeking help or coming forward to law enforcement (Baglay et al., 2024; Canadian Council for Refugees (CCR), 2013). The ability to identify cases of human trafficking may be impacted by the operational lens used by a given agency. As an illustration, border officers might misidentify trafficking cases as smuggling if they are primarily focused on the undocumented status of migrants (Farrell et al., 2015) or may miss trafficking cases where individuals are brought in under temporary worker programs with proper work permits (Kaye et al., 2014). There have been reports of agencies disagreeing in their assessment of cases whereby one agency recognized certain individuals as trafficked persons and the other did not (Perrin, 2010). For instance, while the RCMP does not consider cases of forced marriage to amount to human trafficking, other agencies and stakeholders—including the City of Toronto—argue that the matter does fall under the human trafficking legislation (Beatson and Hanley, 2015).

Further, the literature highlights how human trafficking frequently becomes inflamed and politicized (Dandurand and Jahn, 2020). The politicized nature of government discourse on human trafficking has the potential to impede the accuracy of data collection and reporting. Canadian authorities tend to conceptualize human trafficking predominantly as domestic trafficking and as a crime (rather than a human rights issue) involving sexual exploitation of young women (De Shalit et al., 2021; Durisin and van der Meulen, 2021; Millar and O’Doherty, 2020). The discourse often involves “sensational depictions of trafficking, which focus on child sex slavery rings or large numbers of migrant women forced into sexual slavery” Maynard (2015, p. 43). As Sharma (2005) points out, anti-trafficking practices often contribute to a moral panic that obscures the genuine vulnerabilities faced by survivors, who frequently find themselves trapped between restrictive state policies and capitalist exploitation. This moral panic not only justifies more stringent law enforcement measures but also exacerbates the vulnerabilities of the communities targeted. Additionally, it may further distort data collection and reporting, leading to an incomplete and inaccurate understanding of the broader trafficking landscape. Baird and Connolly (2023) found that available statistics on sex trafficking are often “guesstimates” rather than reliable rates, which makes it a challenge to develop data-informed approaches to prevention and intervention initiatives.

The selective focus on specific forms of trafficking over others diverts attention from other prevalent types of human trafficking. In law enforcement, the tendency to approach human trafficking primarily through the lens of sex crimes or other “vice” offenses can result in labor trafficking cases being overlooked (Farrell et al., 2014; Barrick et al., 2014). We explored elsewhere how discourse shapes agenda-setting, policymaking and implementation processes (Baglay et al., 2024). Our findings confirmed the low visibility of labour trafficking and internationally trafficked persons in government discourse. Most government strategies and action plans in Canada not only reflect a narrow and stereotypical understanding of human trafficking, they also heavily focus on law enforcement and often pay insufficient attention to the needs of survivors (Baglay et al., 2024). This policy context shapes government priorities for NGO funding whereby resources are more likely to be directed to projects and groups that align with the dominant narrative (De Shalit et al., 2014). For example, Ontario NGOs that receive government anti-human trafficking funding tended to reproduce the conflation between sex work and trafficking (De Shalit et al., 2020), which, in turn, impacts the accessibility of supports and services that they provide.

Third, there is no established and universally accepted methodology for collection of data on human trafficking (Saner et al., 2018) and various agencies may use different definitions of human trafficking and of ‘victim’.3 For instance, some may include suspected/presumed cases or self-identified survivors in the numbers of trafficked persons, while others may count only those who have been recognized as survivors by the authorities (Statistics Canada, 2010). With respect to the data on the accused traffickers and convictions, much depends on how human trafficking cases are prosecuted in the criminal justice system. Although many countries have incorporated a specific offence of human trafficking in their legislation, trafficking cases may be prosecuted not only as a human trafficking offence, but also under related charges such as assault, sexual assault, kidnapping and others. Where the latter charges are used to prosecute, it is possible that these cases may not be counted in the human trafficking statistics.

Fourth, like many other countries, Canada does not have a centralized agency for collection/reporting of data. This results in fragmented data scattered across various sources and variation in numbers reflective of differences in definitions and methodological approaches used by respective entities (ICMPD, 2006; Aronowitz, 2010; Zhang and Cai, 2015). While the existence of a centralized agency alone does not guarantee better or more available data, it can prompt development of a more cohesive methodological framework and some quality control.

In Canada, the constitutional division of powers among various levels of government further complicates data collection and reporting efforts. An anti-human trafficking response involves an array of measures, which touch upon federal as well as provincial jurisdiction. Hence, some measures are uniform across Canada and indicators can be collected nationally, while others vary by province and require intergovernmental coordination for Canada-wide reporting. The federal government has jurisdiction over criminal law and immigration status. The Criminal Code contains the definition of human trafficking that captures both domestic and transborder activity. In addition, an offence of human trafficking is included in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA, s. 118), but it concerns transborder trafficking only. Hence, prosecutions are possible under either the Criminal Code or the IRPA and separate statistics need to be collected under each statute. However, the data collection process is complicated by the fact that the administration of justice, including maintenance of courts and prosecutions under the Criminal Code, are within the purview of the provinces. As a result, provinces would be the primary holders of data on human trafficking prosecutions and convictions. They are also responsible for subject matters involving supports for survivors such as income assistance, legal aid, victim compensation and housing (Constitution Act, 1867). Correspondingly, provinces would be in a better position to collect data on survivors, their characteristics, and services that they have accessed. In contrast, data on foreign nationals who received Temporary Resident Permits (TRPs), would be available from the federal government only, corresponding to its jurisdiction over immigration.

Yet another layer of complexity comes from the fact that anti-human trafficking work falls within the ambit of several federal and provincial departments. At the federal level, among the agencies involved are: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), Global Affairs Canada, Public Safety Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), and the Department of Justice. Public Safety Canada has an overall responsibility for the anti-human trafficking coordination across federal departments. IRCC is in charge of immigration policy and application processing, including TRPs for trafficked migrants. The CBSA is responsible for border controls and enforcement, including identification of suspected cases of trafficking and investigation of cross-border human trafficking cases. Global Affairs Canada provides humanitarian and international development assistance to other governments, including funding for anti-human trafficking initiatives. The RCMP runs the Human Trafficking National Coordination Centre (HTNCC), whose mandate includes collecting statistics on human trafficking and promoting training and awareness. It also provides policing services across territories and most provinces. Of note, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador each maintain their own provincial police forces and, hence, data on human trafficking investigations and charges needs to be collected from these provinces separately. Additionally, provinces delegate policing authority to cities, which operate their own municipal police forces. Some of these police forces, such as Toronto Police Service, have their own human trafficking enforcement unit. Considering the division of jurisdiction and the involvement of multiple departments in anti-trafficking efforts, it is imperative that data collection is coordinated across all government levels and different departments. Yet, to the authors’ knowledge, no nation-wide, transparent mechanism has been developed to date.

Various government agencies and civil society organizations have urged action to address the challenges arising from the fragmented jurisdictional landscape. In Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights (2018) recommended that federal and provincial authorities work together to improve data gathering and information sharing and create a national database. A similar call was repeated by the Standing Committee on the Status of Women in 2024: “to improve the collection of data on human trafficking so that it is disaggregated by identity factors, including disability, race, Indigenous identity, sexuality, immigration status and others” and “to establish a national human trafficking database to allow jurisdictions across the country to access standardized information on perpetrators of human trafficking in Canada” (2024, p. 3). The Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking (2023) recommended that the federal government allocate funding for third-party research aimed at identifying, evaluating, and promoting best practices in policies and programs that disrupt human trafficking and support survivors. The 2019–2024 National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking identified improvement of data collection as a priority and committed to building a centralized website to consolidate information on human trafficking (Government of Canada, 2019). Public Safety Canada (2022) launched a website with general information on the definitions, legislation, funding opportunities and resources for survivors but it is not meant to be a source of statistical information or a research resource on human trafficking. A Horizontal Evaluation of the National Strategy (Public Safety Canada, 2024) contended that some progress on data collection has been made through Statistics Canada’s work with police-reported data on human trafficking, but it has also acknowledged that this data is crime-focused and does not contain much information about survivors. The evaluation concluded that “there is a significant need to increase reporting efforts to address data gaps” (Public Safety Canada, 2024).

For this research, we reviewed publicly available data from Statistics Canada, Canada’s National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking (2012–2016), and the National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking (2019–2024). Additionally, we examined Public Safety Canada reports on the implementation progress of both the Action Plan and the Strategy, along with the U.S. Trafficking in Persons reports that include sections on Canada. Our focus was on evaluating the reported data, followed by a comparison of the reporting across these various sources. As mentioned above, there is no universal guidance on the human trafficking statistics that should be collected and reported. However, it is common—both as recommended and as actual practice—to report on the numbers of investigations, charges, convictions, identified victims and some characteristics of victims and perpetrators. In 2010, Statistics Canada consultation on the national human trafficking data collection framework identified similar indicators as essential or important for collection: the number of incidents of human trafficking (suspected and confirmed; domestic and international); type of exploitation (sexual exploitation, forced labour, etc.); number of survivors, their characteristics and citizenship; number of TRPs issued to internationally trafficked persons; number of persons accused of human trafficking and their characteristics; number of prosecutions and convictions. As discussed below, the available data predominantly centers on crime-related metrics, including investigations, prosecutions, convictions, and identified survivors, with some sources also providing information on the number of foreign nationals issued TRPs. Additionally, our findings reveal that human trafficking reporting is fragmented, lacking a standardized approach to data collection and analysis, as well as disaggregated data. Statistics appear to be used largely in ornamental ways as vignettes to illustrate government narratives rather than a source of information that can prompt questions about policies or monitor their effects.

Each of the above-mentioned sources reports on some, but not all of the above-mentioned indicators (see Table 1). For example, Statistics Canada provides detailed information on the criminal justice side but its data on survivors is limited and there is no information on internationally trafficked persons. Public Safety annual progress reports are available only for select years and contain less detailed information on the criminal justice side than Statistics Canada, but they provide some information on survivors, including internationally trafficked persons. Thus, to gain at least some idea about human trafficking trends in Canada one needs to piece together—like a mosaic—data from several sources.

The National Action Plan and National Strategy provide only aggregate data for select years without any apparent logic or consistent coverage of time periods. To illustrate, the 2019–24 Strategy mentions the following three pieces of information:

• Between 2009 and 2016—Ontario accounted for more than two thirds of reported incidents (no actual numbers or breakdown by year provided)

• In 2017, there was a total of 375 police-reported incidents, involving 291 accused (this is the single year for which statistics are provided)

• From January 2016 to December 2018, the Government issued 146 TRPs to survivors (unclear why only 2 years preceding the Strategy are covered, given that TRPs have been in place since 2006)

The 2012–2016 Action Plan included four pieces of statistics:

• As of April 2012: 25 convictions (41 survivors) under human trafficking offences in the Criminal Code.

• As of April 2012, 56 cases are pending before courts, involving 85 accused and 136 survivors.

• Over 90% of the above cases involve domestic human trafficking; the remaining involved transborder trafficking.

• From May 2006 to December 2011, 178 TRPs were issued to 73 foreign nationals. Out of these, 16 were males and 54 were females; 3 were minor dependents of adult survivors (gender not specified). 54 of the survivors endured labour exploitation and 14—sexual exploitation.

The statistics in the Action Plan and Strategy are fragmented and appear to be merely illustrative snapshots rather than an overview of known trends that ground policy responses or future priorities. While they are policy documents that may not be intended to serve as sources of detailed statistics, it is difficult to understand how the action items and future directions of anti-trafficking policies are determined without the knowledge and presentation of longitudinal trends.

Public Safety Canada produces annual reports on the progress under the National Action Plan and the National Strategy. However, the data range of these reports is limited—2012 to 2016 and 2019 to 2023—as they are associated with the time periods when the Action Plan and the National Strategy were in place, respectively. There are no reports between 2016 and 2019 as the National Action Plan expired in 2016 and no new plan or strategy was adopted until 2019.

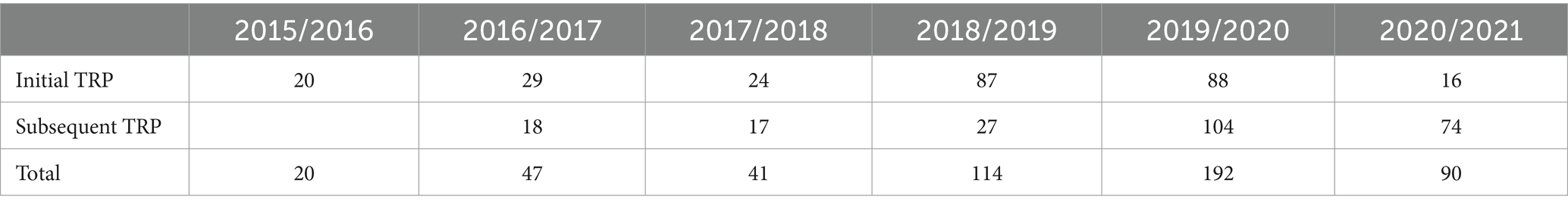

Information on internationally trafficked persons is available mostly in aggregate numbers for select periods of time and from a compilation of sources; there are no yearly breakdowns or consistent reporting. For example, the National Action Plan (2012–16) indicated that between May 2006 and December 2014, 178 TRPs were issued to 73 foreign nationals (Government of Canada, 2012). A Public Safety Canada (2016) study of TRPs reported that between 2012 and 2015, IRCC issued 142 TRPs (119 to survivors and 23 to their children and spouses). The National Strategy (2019–24) reported that from January 2016 to December 2018, 146 TRPs were issued to survivors and dependents. Another report stated that between 2013 and 2018, 271 TRPs were granted to survivors and their dependents (Public Safety Canada, 2018). Such aggregate reporting precludes any monitoring of trends and is particularly problematic in light of long-standing concerns about the underuse of TRPs issued, their restrictive criteria and other challenges encountered by trafficked migrants (CCR, 2018; Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2024). Ironically, the most consistent reporting of yearly information on both prosecutions and survivors, including TRPs, is found in a non-Canadian source: the US Trafficking in Persons Reports (TIP Reports, US Department of State, 2023).

As mentioned above, each available source focuses on pieces of information and there does not appear to be a uniform approach to the types of data that are considered essential. Even within the same source, the approach to reporting changes year to year. For example, Public Safety Canada annual reports usually contain statistics on police-reported cases, ongoing prosecutions and convictions as well as TRPs, but reporting and breakdown is not always consistent. The 2012–13 report includes information on the types of human trafficking (sexual vs. labour exploitation) and gender of survivors who were issued TRPs (Public Safety Canada, 2013). The 2013–14 report provides information on the gender of survivors, but no breakdown by type of trafficking (Public Safety Canada, 2014). Similarly, the reports for 2014–15 and 2015–16 no longer offer breakdowns, only presenting the overall number of cases and TRPs. The 2019–20 and 2020–21 reports show a breakdown of police-reported incidents under Criminal Code vs. the IRPA, but no breakdown by type of trafficking or gender of survivors who were issued TRPs (Public Safety Canada, 2020, 2021). Some data is made available in percentages only, without indication of actual numbers (e.g., X% of survivors were female). Some data is presented as an aggregate for several years, without yearly breakdowns. The 2021–23 report provides even less disaggregated data: no breakdowns of prosecutions by Criminal Code vs. IRPA and no breakdown of survivors by gender (Public Safety Canada, 2023). Since 2019, Public Safety Canada reports provide less statistical information and focus primarily on how much funding was allocated to anti-trafficking initiatives, how many awareness campaigns were conducted, and officers trained.

Most of the reports discussed above do not clearly outline their methodologies or sources of information. The only exception is Statistics Canada, which relies on police-reported data (Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2024). But such data is not particularly accurate or reliable. On the one hand, as previously stated, it may lead to underreporting as not all survivors turn to the police. In addition, police may not classify an incident as human trafficking if there is insufficient evidence to lay the human trafficking charges (Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2024). At the same time, some numbers may be inflated when, for example, individuals working in the sex industry consensually are ‘classified’ as trafficked persons (Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2024). The focus on police-reported data also reflects the predominant criminal justice nature of current anti-human trafficking efforts, while showing limited attention to survivors.

Another noticeable issue is inconsistencies between numbers reported in different sources. For example, there are discrepancies between the numbers of charges and survivors reported by Statistics Canada compared to those in the US TIP reports (see Tables 2–4) or the numbers of internationally trafficked persons reported in the US TIP reports and those reported by Public Safety (see Table 5). It is not known what causes these inconsistencies. They can arise from the different methodologies; the differences in the legal frameworks under which trafficking cases are categorized; divergent data sources and the varying capacities of agencies to collect and report data. Understanding the root causes of these discrepancies is crucial for improving data practices.

None of the examined sources consistently report disaggregated data on the age and gender of offenders and survivors, types of exploitation, types of charges (Criminal Code vs. IRPA) or citizenship of survivors. For example, some of Statistics Canada’s annual reports on trafficking in persons provide only aggregate data and others - disaggregation on few indicators. From 2006 onwards, Statistics Canada provides a breakdown by Criminal Code versus IRPA charges, the incidence of human trafficking across provinces and metropolitan areas, and trends on gender and age of survivors. However, it does not provide annual breakdowns by type of trafficking or other characteristics of survivors as it is currently not possible to disaggregate police-reported data by these parameters (Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2024).

The available Statistics Canada data are largely based on police-reported cases and draw upon the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and the Integrated Criminal Court Survey, which do not capture unreported cases and may distort figures concerning trafficked migrants as they are particularly vulnerable due to precarious (or lack of) immigration status and risk of deportation.

Although there are several gaps in the discussed public sources, this does not automatically mean that sought data is not available. It is possible that the gaps are more indicative of issues in reporting than in data collection. To test this assumption, we filed a series of ATI requests in hopes to obtain more detailed statistics.

Federal and provincial ATI regimes protect the right of the members of the public to access records under control of federal and provincial institutions and impose an obligation on those institutions to make every reasonable effort to assist the ATI applicant and to respond to the request as accurately and completely as possible.4

Our ATI requests sought to obtain the following data from 2006 to present with breakdown by year, type of trafficking and (where applicable) gender of survivors:

• number of persons charged with human trafficking offences (with breakdown of charges under IRPA vs. Criminal Code);

• number of convictions, acquittals and withdrawal/stay/dismissal of charges (with breakdown of charges under IRPA vs. Criminal Code);

• overall number of survivors identified;

• number of survivors who have testified at trial or otherwise assisted the prosecution;

• number of identified survivors who are foreign nationals;

• number of referrals made by the police or prosecution to IRCC (for the purpose of a TRP);

• number of foreign nationals who have testified at trial or otherwise assisted the prosecution;

• number of TRPs issued to foreign nationals and their dependents.

The requests were made to federal and provincial authorities (respective of their areas of jurisdiction) at various times during 2022, with follow ups in 2023.

ATI regimes are particularly relevant to the conceptual framework of this article. Access to information is a key open government principle and a cornerstone of democracy (McLachlin, 2009). Accountability, transparency and meaningful public participation in governance are impossible in the absence of information about what the government is doing (McLachlin, 2009). While ATI regimes have been put in place to promote such transparency and accountability [Access to Information Act, 1985, s 2(1)], the effectiveness of these regimes has been marred by various problems: delays, costs, agencies’ denial of existence of records, rigid interpretation of requests, and broad and arbitrary use of statutory exemptions (Dickson, 2013; Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics, 2023). Research has also shown that the lack of (accurate) record production and retention, over-zealous redaction as well as the prioritization of private over public interests, and political interference significantly impede the goals of the ATI regimes, “eroding the values of public memory, accountability, and social justice” (Luscombe and Walby, 2017, p. 382; Tomkinson, 2023; Duncan et al., 2023). Access to information may be particularly challenging when requested information has the potential to embarrass a government agency or disrupt a government narrative (Larsen and Walby, 2013). ATI regimes can therefore lead to defensive, risk reduction responses, which ultimately result in a slow and obstructionist ATI system (Larsen and Walby, 2013). Demands for more information and accountability may lead some agencies to become even more restrictive in their disclosures (Dafnos, 2013).

In our research, we encountered the following systemic challenges: difficulty identifying the appropriate department to which direct our requests, processing delays, limited information disclosure, and instances where the provided information did not fully address our requests.

At the federal level, Public Safety Canada is the primary agency responsible for anti-human trafficking work and coordination among departments. Hence, we thought that it would be best positioned to provide the requested statistics. However, Public Safety transferred our request to the RCMP “as that institution has a greater interest in the information you are seeking” (A-2002-00015). This suggests that the primary coordinating agency does not accumulate statistics on human trafficking and approaches human trafficking through a crime-focused lens (for example, it did not forward immigration-related parts of the request to IRCC).

The request to Public Safety was filed on April 5, 2022 and was transferred to the RCMP on April 20, 2022. As of the time of writing, the request is still pending. We also filed a request with the CBSA to obtain statistics on the number of foreign nationals identified as survivors of human trafficking at the border and with IRCC—on the number of TRPs issued to foreign nationals with breakdown by year, gender and type of exploitation. In addition to federal departments, we contacted provincial authorities. Few provinces have an anti-human trafficking coordination office, or a ministry designated as a lead on anti-human trafficking efforts. For example, in Ontario, the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services is the lead on anti-human trafficking work. However, in other provinces, such designation is often unclear, and it may be difficult to identify a proper addressee for our ATI requests. We usually directed our inquiries to the ministries of justice and public safety as well as the police forces of major metropolitan areas (Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary and Vancouver) as they were most likely to have information on prosecution, convictions and identified survivors.

Some of our requests were affected by the pandemic delays, but despite this, disclosure was typically provided within several months. Notable outliers are the police forces. The request to the RCMP has now been pending for 2 years. The RCMP itself admitted that it struggles with compliance under the ATI and has a backlog of requests dating back to 2017 (Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics, 2023). Similarly, the responses for our requests to Calgary, Toronto, and Vancouver police forces took nearly 2 years.

The information we obtained was limited and piecemeal, demonstrating similar problems as publicly available information. The major shortcomings were:

(a) some information was not being collected. For example, the CBSA was not collecting statistics on the number of trafficked migrants identified at the border (A-2021-20435 / BPERR6). At the provincial level, departments of justice or public safety usually were able to provide information on the number of charges laid and on the number of survivors, but most of the other requested data was not available, including: breakdown by type of trafficking, charges under the Criminal Code vs. IRPA, convictions/acquittals/withdrawals, numbers of trafficked migrants. For example, Justice and Public Safety department in Alberta advised that they do not collect the information sought and suggested that we direct the request to provincial and municipal police forces. Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan provided publicly available reports by Statistics Canada on human trafficking in Canada in 2018 and 2019, without adding any other information (JU-028-22-G7; JUS 2023-005598). Newfoundland provided a copy of an email where an official from a prosecution office stated that there was only one charge in 2014 and no other charges between 2010 and 2020 (JPS 61-20229). Quebec was the only province that provided more detailed information, including charges with breakdown of Criminal Code vs. IRPA, and the number of survivors (2022-1173010). None of the provinces appear to collect any information on trafficked migrants or on the frequency of survivor participation in legal proceedings or testimony at trial.

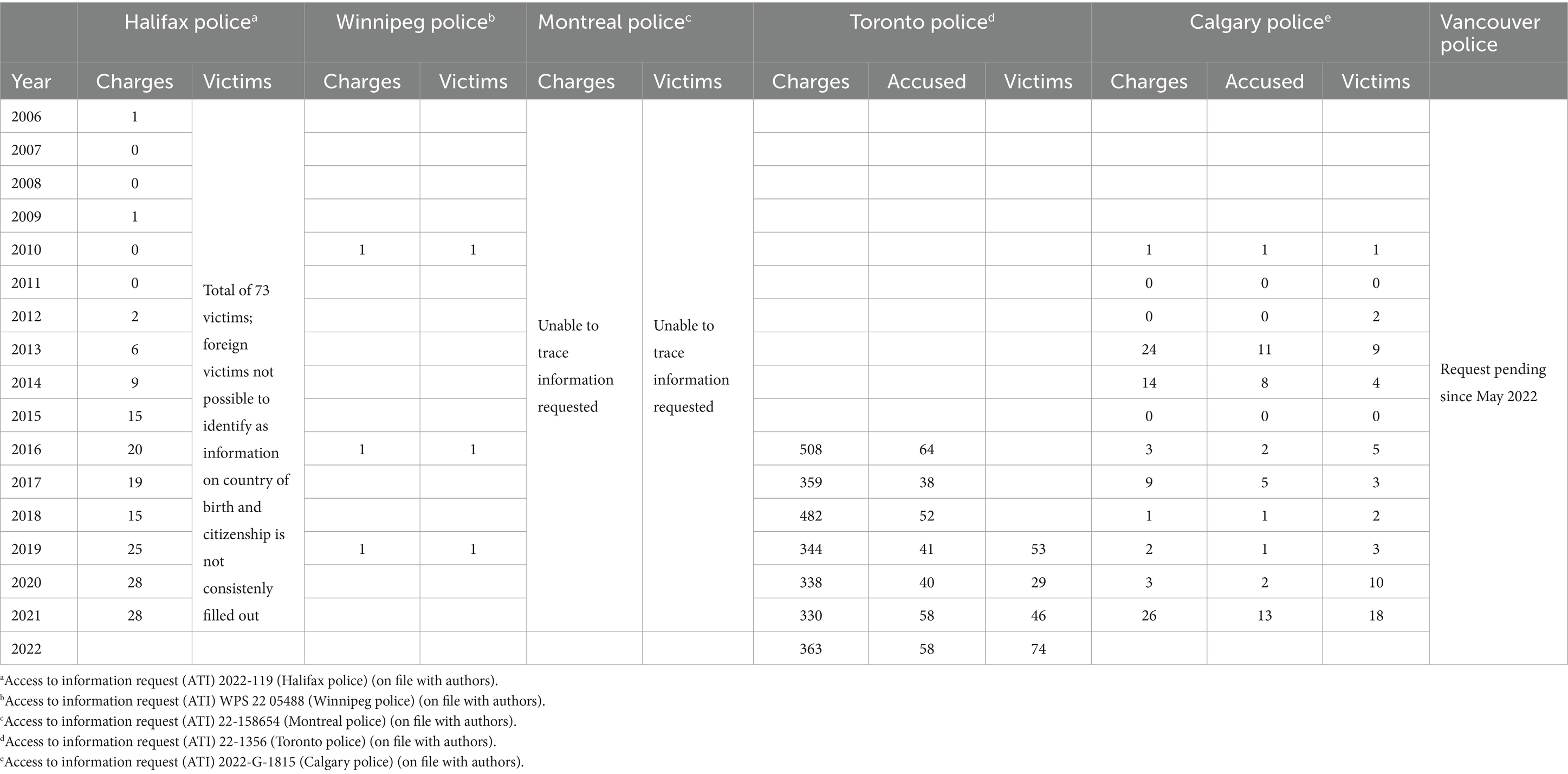

Likewise, the data obtained from municipal police forces proved to be incomplete (Table 6). The ATI request we filed with Vancouver police force in May 2022 was still pending as of December 2024. Montreal police were unable to trace the information requested. Calgary and Toronto police forces disclosed information on the number of human trafficking-related charges, the number of persons charged with human trafficking offences, and the number of survivors identified, but other parts of our requests (breakdown of charges under IRPA vs. Criminal Code; breakdown by type of trafficking, gender and nationality of survivors) remained unanswered. The time periods over which information was available also varied. For example, the Calgary Police Force provided information dating back to 2010, while the Toronto Police Service’s data only extended to 2016. The Halifax municipal police appeared to have collected some of the requested information since 2006, yet there were notable gaps in their data, which primarily focused on charges and survivor counts.

Table 6. Data on charges and survivors disclosed by municipal police forces [2022-G-1815 (Calgary police); 2022-119 (Halifax police); 22-158654 (Montreal police); 22-1356 (Toronto police); WPS 22 05488 (Winnipeg police)].

There appears to be a common thread among provincial and municipal agencies: even fairly basic disaggregated data such as the type of trafficking, IRPA vs. Criminal code charges, gender and citizenship of survivors are not collected.

(b) where information was available, it was tracked and presented in a confusing manner. A case in point is TRPs for survivors of human trafficking and their dependents. Tables 7–9, which are part of the same information package disclosed by IRCC, show that no single, definitive table of information is available on TRPs issued to the survivors.

Table 7. Number of TRPs (including extensions) issued for survivors and dependents from January 2016 to March 2021.

Table 9. Number of TRPs (including extensions) issued to survivors and dependents between 2019 and 2022 by destination province.

While Table 7 figures are broken down by fiscal year, Table 8 and Table 9 delineate them according to calendar years. Despite this differentiation, discrepancies persist in the totals. It is not clear whether the numbers in Table 8 include extensions/renewals. Consequently, obtaining a clear overview of the total TRPs issued for any given year remains elusive. The tables show a deficiency in systematically collecting and organizing essential data concerning the number of TRPs issued, encompassing renewals and dependents. This lack of integration and organization, which is also apparent in the publicly available data on TRP statistics above, hampers a comprehensive understanding of TRP issuance trends and policy review. It puts into question IRCC’s implementation of the TRP policy objective to “respond to the vulnerable situation of victims of trafficking in persons by providing these individuals with a means of legalizing their temporary resident status in Canada, when appropriate” (Government of Canada, 2024c). Some of the requested information was not provided, namely the average length of TRPs, the number of survivors who received permanent residence under the permit holder class or under humanitarian and compassionate consideration (ATI 1A-2023-2564211).

The availability of multidimensional data on human trafficking is important for several reasons. First, it can contribute to the development of more informed policies, encourage critical questions and re-appraisal of the current measures. Second, it fits within a broader framework of open government, which fosters transparency in policy making and informs the public about critical issues in society.

It has been nearly 20 years since Canada acceded to the UN Trafficking Protocol, during which millions of dollars have been invested in various anti-human trafficking initiatives, particularly in law enforcement. However, little has been done to lay the groundwork for meaningful data collection. At the moment, publicly available sources suffer from a lack of consistent reporting, disaggregated details and transparency. For example, the data on breakdowns by types of trafficking (such as labour versus sex trafficking and domestic versus international trafficking) and on foreign nationals trafficked to Canada is not consistently available year to year. Disaggregated data on survivors and accused is limited. There is little transparency (except for reports by Statistics Canada) about methodologies and sources of presented data. As there is no central reporting agency or a national database, information is scattered across various sources and poorly tracked. Canada faces dual challenges of lack of effective information sharing across jurisdictions and an absence of common standards and systems for information collection (Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2024).

While highlighting the above concerns, we need to ensure not to fall into the trap of the usual mantra: if we only had more data, we could solve issues of human trafficking (Aradau, 2015; Uhl, 2018). Aradau (2015) remarks how conceptualizing the root causes of this lack of knowledge with reference to ignorance (lack of awareness of trafficking situations), secrecy (clandestine nature of trafficking) or uncertainty (human trafficking as a constantly changing phenomenon) has implications for ‘remedial’ measures as well as data acquisition and use. For example, the ignorance lens can elevate the status of ‘experts’, while delegitimizing other voices; secrecy lens can enable responses that seek to control and surveil; the uncertainty lens can lead to invasive data collection practices that infringe upon privacy or other rights (Aradau, 2015). This underscores the need for increased thoughtfulness and responsibility regarding data practices and their effects as well as the very constructs of data gaps and availability.

Further, knowledge production and data collection are not neutral (Uhl, 2018). They are impacted by ideological frameworks of government institutions as well as perceptions of individual officials involved in front-line work, policy-making and data collection/reporting (Vorheyer, 2018). The politicized nature and flawed conceptualization of human trafficking as well as the distorted government discourse surrounding survivors impede data availability and accuracy. This creates a vicious circle: the data resulting from these processes is suspect, so why continue collecting it? Can we even use it as ‘evidence’ in policy-making? At the same time, ceasing the use of statistical data until we change the mainstream discourse is not a viable solution either. How do we address this conundrum? We believe that critical conversations on human trafficking data can prompt some ‘soul-searching’ in relation to human trafficking discourse as a whole and incrementally contribute to its change. The mapping exercise undertaken in this article can offer some ideas for future discussion.

First, we need to discuss the meaning of ‘data’ and ‘evidence’: does it comprise statistical information only? A related question concerns the place for qualitative information available from survivors, service-providers, advocates, academics and other stakeholders. For the purpose of evidence-based policies, evidence includes not only scientific knowledge, but also political knowledge, strategies, tactics and agenda-setting of political leaders; professional knowledge of service delivery practitioners; experiential knowledge of service users and stakeholders (Head, 2010); results from stakeholder consultations, and other data collected inside and outside government. Statistics do not provide a complete and objective picture of reality. To be meaningful, statistical information needs to be situated within qualitative experiences of participants of the system as well as in the critical discourse analysis.

Second, we need to clearly identify the main purposes of data collection, a standardized list of indicators that could facilitate more consistent data collection across all agencies, as well as critically examine whether these indicators should continue focusing primarily on crime. A survey of the types of data currently collected by provincial and federal agencies is essential, along with an assessment of their institutional capacities to produce disaggregated data. On the latter point, some caution that data collection tools can become means to categorise, label, and control survivors, transforming them into objects of data collection (Uhl, 2018). The pursuit of more disaggregated data may lead to compromising privacy rights of survivors and, hence, it is important to identify the clear purpose of personal data collection and minimize it to what is absolutely necessary (Uhl, 2018).

Third, understanding how data is collected across different agencies requires clarity on the definitions and survivor identification processes used. Notably, the absence of data on types of exploitation, distinctions between IRPA and Criminal Code charges, and the citizenship status of survivors needs addressing. Establishing which federal and provincial agencies should be primarily responsible for data collection is paramount for coordination and effectiveness.

Fourth, it is important to explore how the collected data is utilized by various agencies and for what purposes. Discrepancies in reported numbers regarding the same indicators among Public Safety, Statistics Canada, and the US TIP Reports must be analyzed, including the sources used for gathering this information. Identifying obstacles to aggregating information from all relevant agencies is crucial, along with strategies to overcome these challenges.

Fifth, while the current data is limited, raising questions about reliability should lead to a thoughtful reassessment of existing policies. The low number of police-reported human trafficking cases raises concerns about the justification for significant investments in anti-human trafficking investigations and prosecutions. Additionally, the rationale for focusing on sex trafficking work in light of the lack of disaggregated data calls for careful consideration.

A national database could help establish comparable standards, processes and information systems across departments and levels of government (Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2024). In fact, Statistics Canada started working with the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police to create a national database and, in the coming years, it may be able to expand the scope of reported disaggregated data to include ethnicity, indigeneity and immigration status. However, a more comprehensive approach is needed to compile not only police-reported data, but also more information on the experiences of survivors. This entails gathering information on their utilization of support services and assessing the availability and effectiveness of these services. In this process, the open government principles such as transparency, timely access to information, and effective collaboration among relevant stakeholders would bolster the accountability of government agencies to the public, fostering confidence in anti-human trafficking policies.

Establishing a national data collection and reporting system is a complicated endeavor fraught with methodological and practical challenges. Even once more comprehensive data is available, it will not be a ‘perfectly complete’ representation of all trends. We recognize the complex relationship between evidence/data and policy, which often exposes competing ideas about what counts as ‘evidence’, who can be considered an ‘expert’, and how research should be carried out (Balch and Hesketh, 2024). We do not suggest that more data will automatically help improve Canada’s anti-human trafficking response. However, taken together with critical literature and stakeholder input, it can prompt reappraisal of policy directions and more critical questioning of the data itself. As the current National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking (2019–24) is due for a review and renewal, it is time to re-evaluate the fundamental premises underlying current anti-human trafficking efforts and to strive for enhanced data collection and accessibility to align with the open government framework. To this end, better connections must be formed between decision-makers/implementers and key stakeholders, including researchers and civil society organizations working on anti-human trafficking areas. This would entail unobstructed information sharing and regular consultations and other forms of collaboration, as a minimum requirement. Such collaboration would help pinpoint gaps and shortcomings in existing data and their root causes, enabling a thorough examination and recalibration of prevailing narratives. Moreover, such collaborative forms of democracy can help counteract rhetoric-driven policy formation and contribute to reflexive policy processes that are informed by quantitative and qualitative data, and inclusive of various voices.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

SB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Insight Grant (grant reference number: 435-2019-0746).

SB would like to thank Dakoda Cluett and Luis Lara Palacios for their research assistance on the project.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^We are aware of the problematic nature of the TIP reports (see, for example, Gallagher, 2015; Hyatt, 2022) and are not taking their data at face value. However, they continue to be considered one of the important sources of information on national and global anti-human trafficking efforts and for that reason are included in our discussion.

2. ^While the idea of evidence-based policy-making has gained significant popularity, there are also criticisms of this approach (e.g., Parsons, 2002; Greenhalgh and Russell, 2009) and various limitations and challenges to it (Sanderson, 2003; Howlett and Craft, 2013; Pankhurst, 2017). Thus, it should not be seen as the only or superior approach to policy-making or a guarantee of policy successes.

3. ^Throughout the paper we use the term ‘survivor. However, legislation and government documents continue using the term ‘victim’ and our reference here reflects this reality.

4. ^The exact wording of rights to information and obligations to disclose varies from one piece of legislation to another. For example, federal legislation limits information rights to Canadian citizens and permanent residents (Access to Information Act, 1985, s. 4), while provincial legislation tend to not impose such limitations (see, e.g., BC’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, RSBC, 1996, s. 4, c. 165; Ontario’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, R.S.O. 1990, s. 10, c. F.31).

5. ^Access to information request (ATI) A-2002-0001 (Public Safety Canada) (on file with authors).

6. ^Access to information request (ATI) A-2021-20435 / BPERR (CBSA) (on file with authors).

7. ^Access to information request (ATI) JU-028-22-G (Ministry of Justice, Saskatchewan) (on file with authors).

8. ^Access to information request (ATI) JUS 2023-00559 (Justice and Public Safety, Nova Scotia) (on file with authors).

9. ^Access to information request (ATI) JPS 2023-102 (Justice and Public Safety, PEI) (on file with authors); Access to information request (ATI) JPS 61-2022 (Justice and Public Safety, Newfoundland and Labrador) (on file with authors).

10. ^Access to information request (ATI) 2022-11730 (Ministry of Public Safety, Quebec) (on file with authors).

11. ^Access to information request (ATI) 1A-2023-25642 (IRCC) (on file with authors).

Adam, C., Steinbach, Y., and Knill, C. (2018). Neglected challenges to evidence-based policy-making: the problem of policy accumulation. Policy. Sci. 51, 269–290. doi: 10.1007/s11077-018-9318-4

Aradau, C. (2015). Human trafficking: between data and knowledge. In data protection challenges in anti-trafficking policies: A practical guide. KOK e.V. – German NGO Network against Trafficking in Human Beings

Aronowitz, A. A. (2010). Overcoming the challenges to accurately measuring the phenomenon of human trafficking. Rev. Int. Dr. Pénal 81, 493–511.

Baglay, S., Atak, I., and Kalaydzhieva, V. (2024). Understanding gaps in supports for trafficked migrants in Canada: a discursive analysis. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 25, 1325–1349. doi: 10.1007/s12134-024-01126-z

Baird, K., and Connolly, J. (2023). Recruitment and entrapment pathways of minors into sex trafficking in Canada and the United States: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 24, 189–202. doi: 10.1177/15248380211025241

Balch, A., and Hesketh, O. (2024). Mind the gap(s)? Evidence and UK policymaking on human trafficking and modern slavery. J. Hum. Trafficking 10, 330–338. doi: 10.1080/23322705.2024.2303257

Barrick, K., Lattimore, P. K., Pitts, W. J., and Zhang, S. X. (2014). When Farmworkers and Advocates See Trafficking but Law Enforcement Does Not: Challenges in Identifying Labor Trafficking in North Carolina. Crime, Law, and Social Change 61, 205–214. doi: 10.1007/s10611-013-9509-z

Beatson, J., and Hanley, J. (2015). The Exploitation of Foreign Workers in Our Own Backyards: An Examination of Labour Exploitation and Labour Trafficking in Canada. Committee of Action Against Human Trafficking National and International (CATHII).

Bovens, M. A. P., Goodin, R. E., and Schillemans, T. (2014) in The Oxford handbook public accountability. eds. M. A. P. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans. First ed. (Oxford University Press).

Canadian Council for Refugees (CCR). (2013). Temporary resident permits: limits to protection for trafficked persons [online]. Available at: http://ccrweb.ca/sites/ccrweb.ca/files/temporary-resident-permit-report.pdf

Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking. (2023). Recommendations for the next National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking. Available at: https://www.canadiancentretoendhumantrafficking.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Canadian-Centre-to-End-Human-Trafficking-letter-to-Minister-Mendicino.pdf

CCR. (2018). CCR concerns: Human trafficking in Canada. A submission to the house of commons standing committee on justice and human rights for their study on human trafficking in Canada. Available at: http://ccrweb.ca/en/ccr-concerns-human-trafficking-canada

Dafnos, T. (2013). “Beyond the blue line: researching the policing of aboriginal activism using access to information” in Brokering access: Power, politics, and freedom of information process in Canada. eds. M. Larsen and K. Walby (Vancouver: UBC Press).

Dandurand, Y., and Jahn, J. (2020). “The failing international legal framework on migrant smuggling and human trafficking” in The Palgrave international handbook of human trafficking, 783–800.

De Shalit, A., Heynen, R., and van der Meulen, E. (2014). Human trafficking and media myths: Federal Funding, communication strategies, and Canadian anti-trafficking programs. Can. J. Commun. 39, 385–412. doi: 10.22230/cjc.2014v39n3a2784

De Shalit, A., Roots, A., and van der Meulen, E. (2021). Knowledge mobilization by provincial politicians: the united front against trafficking in Ontario Canada. J. Hum. Trafficking 9, 568–586. doi: 10.1080/23322705.2021.1934370

De Shalit, A., van der Meulen, E., and Guta, A. (2020). Social service responses to human trafficking: the making of a public health problem. Cult. Health Sex. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1802670

Dickson, G. (2013). “Access regimes: provincial freedom of information law across Canada” in Brokering access: Power, politics, and freedom of information process in Canada. eds. M. Larsen and K. Walby (Vancouver: UBC Press).

Duncan, J., Luscombe, A., and Walby, K. (2023). Governing through transparency: investigating the new access to information regime in Canada. Inf. Soc. 39, 45–61. doi: 10.1080/01972243.2022.2134241

Durisin, E., and van der Meulen, E. (2021). The perfect victim: Young girls, domestic trafficking and anti-prostitution politics in Canada. Anti-Trafficking Rev. 16, 145–149. doi: 10.14197/atr.201221169

European Commission. (2020). Data collection on trafficking in human beings in the EU. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2837/45442

European Commission. (2021). EU strategy on combatting trafficking in human beings (2021–2025). Available at: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/internal-security/organised-crime-and-human-trafficking/together-against-trafficking-human-beings/eu-strategy-combatting-trafficking-human-beings-2021-2025_en

Farrell, A., Pfeffer, R., Zhang, S. X., and Weitzer, R. (2014). Policing Human Trafficking: Cultural Blinders and Organizational Barriers. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 653, 46–64. doi: 10.1177/0002716213515835

Farrell, A., Pfeffer, R., and Bright, K. (2015). Police perceptions of human trafficking. Journal of Crime & Justice 38, 315–333. doi: 10.1080/0735648X.2014.995412

Farrell, A., and Reichert, J. (2017). Using U.S. law-enforcement data: promise and limits in measuring human trafficking. J. Hum. Trafficking 3, 39–60. doi: 10.1080/23322705.2017.1280324

Gallagher, A. (2015). The 2015 US trafficking report: Signs of decline? Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/2015-us-trafficking-report-signs-of-decline/

Government of Canada. (2012). National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking. Available at: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/ntnl-ctn-pln-cmbt/ntnl-ctn-pln-cmbt-eng.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2023)

Government of Canada. (2019). National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking 2019–2024. Available at: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2019-ntnl-strtgy-hmnn-trffc/2019-ntnl-strtgy-hmnn-trffc-en.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2023)

Government of Canada. (2024a). National Action Plan on Open Government. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/government-wide-reporting-spending-operations/trust-transparency/about-open-government/national-action-plan-open-government.html

Government of Canada. (2024b). Cabinet directive on regulation. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/laws/developing-improving-federal-regulations/requirements-developing-managing-reviewing-regulations/guidelines-tools/cabinet-directive-regulation.html

Government of Canada. (2024c). Office of the Chief Science Advisor. Available at: https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/office-chief-science-advisor

Greenhalgh, T., and Russell, J. (2009). Evidence-based policymaking: a critique. Perspect. Biol. Med. 52, 304–318. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0085

GRETA (2023). Questionnaire for the evaluation of the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on action against trafficking in human beings by the parties. Available at: https://rm.coe.int/questionnaire-for-the-evaluation-of-the-implementation-of-the-council-/1680abd8fa

Head, B. W. (2010). Reconsidering evidence-based policy: key issues and challenges. Polic. Soc. 29, 77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2010.03.001

Howlett, M., and Craft, J. (2013). “Policy advisory systems and evidence-based policy: the location and content of evidentiary policy advice” in Evidence-based policy-making in Canada. ed. S. Young (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 27–44.

Hyatt, B. (2022). “TIP-ping the scales: Bias in the trafficking in persons report?” Human Trafficking Search. Available at: https://humantraffickingsearch.org/tip-ping-the-scales-bias-in-the-trafficking-in-persons-report/ (Accessed November 29, 2022)

ICMPD. (2006). Guidelines for the development and implementation of a comprehensive national anti-trafficking response

Kaye, J., Winterdyk, J., and Quarterman, L. (2014). Beyond criminal justice: a case study of responding to human trafficking in canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice. 56, 23–48. doi: 10.3138/cjccj.2012.E33

Larsen, M., and Walby, K. (2013). “On the politics of access to information” in Brokering access: Power, politics, and freedom of information process in Canada. eds. M. Larsen and K. Walby (Vancouver: UBC Press).