- 1Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur, Jodhpur, India

- 2Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India

Introduction: In this article, authors have investigated the relationship between intergenerational educational mobility and the chances of experiencing domestic violence among Indian women. This perhaps is the first ever attempt to demonstrate this relationship not just in the Indian context but also in the global scholarship on domestic violence.

Methods: The analysis is based on logistic regression using the data ‘India Youth Survey: Situation and Needs’. Authors have controlled for various individual, familial, and community-level factors in achieving the results.

Results: Findings indicate that women who have more years of education than their mothers have significantly lesser chances of experiencing domestic violence. Furthermore, daughters whose mothers have been victims of domestic violence are highly likely to experience it themselves. Besides, women whose husbands consume alcohol, come from low income strata or live in nuclear families have significantly higher odds of experiencing domestic violence. Also, it was observed that the odds of experiencing domestic violence vary significantly for different castes, regions, religions as well as rural and urban areas. Insights from this study can contribute to policymaking aimed at empowering women through education, especially when their mothers have not had a significant education. Additionally, the study further substantiates the role of factors such as maternal experience of domestic violence, husband’s alcohol consumption, low income levels, and family structure in determining the likelihood of experiencing domestic violence. Therefore, the findings support existing scholarship for designing targeted interventions to address these specific risk factors, ultimately contributing to creating safer environments for women.

Conclusion: Merely educational attainments do not affect the chances of domestic violence to a large extent. It is probably the confidence a woman derives on account of better educational attainments as compared to her previous generation that influences her take on the menace of domestic violence.

Introduction

Whether at home, on the streets or during war, violence against women and girls is a human rights violation of pandemic proportions that takes place in public and private spaces (WHO, 2013; Bhattacharyya et al., 2021; Reilly et al., 2021; Veloso, 2022; Pertek et al., 2023). Amongst all forms of violence against women, domestic violence is the most rampant one. It is estimated that about 35 per cent of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual violence by their partner (not including sexual harassment) at some point in their lives (WHO, 2021). According to several empirical studies up to 75% women are victims of domestic violence in India (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Karlekar, 1998; Visaria, 2000; National Crime Records Bureau, 2019; Kamath et al., 2022; Mahapatro et al., 2023). There are several theories from the existing literature which explain the prevalence of domestic violence such as evolutionary theories, social and family culture of violence and feminist theories (Eswaran and Malhotra, 2011; Anderson, 2010; Alesina et al., 2016).

WHO defines domestic violence as the range of sexually, psychologically and physically coercive acts used against adult and adolescent women by current or former male intimate partners (WHO, 2012). Violence against women in all forms casts a long shadow on the overall development of any economy. Evidence shows that women who have experienced domestic violence report higher rates of depression, having an abortion and acquiring HIV, compared to women who have not (WHO, 2013). A profusion of research has been done to address this concern around the world and most of them suggest that effective way to tackle domestic violence is to tackle it in such a way that it does not occur in the first place by addressing its root causes (Gelles, 1974; Hall, 2000; Martin, 1976; Mirchandani, 2006; Nielson et al., 1979; Steinmetz and Straus, 1974; Straus and Hotaling, 1980; Erten and Keskin, 2018; Heath et al., 2020; Gahramanov et al., 2022; Samal and Poornesh, 2022; Kamat et al., 2013; Piedalue, 2015).

Violence against women in India is both systemic and systematic. It occurs in both the public and private spheres. Patriarchal social norms, customs and religious practices have been a persistent feature of Indian society since time immemorial. The manifestations of violence against women reflect these structural and institutional inequalities that are pervasive and entrenched in Indian society (WHO, 2013). Women, especially wives have been living a status that is subordinate to their husbands (Sultana, 2010). Despite the challenging nature of the issue, India has consistently made advancements in fulfilling its dedication to achieving gender equality. India’s enduring battle against patriarchy has been influenced by a multitude of social and political developments (Sen, 2000). Social, political and economic empowerment of women through education continues to be one of the key vehicles to end violence against women (Koenig et al., 2003; Koenig et al., 2006). However, there have been numerous instances where well educated women were reported to have suffered from severe forms of domestic violence (Sanghera, 2018). This hints towards the need to explore the possibility that the fundamental reason behind the problem could be ingrained in the intricate family patterns in India. Eswaran and Malhotra (2011) present some evidence for the evolutionary theory of domestic violence, which argues that such violence stems from the jealousy caused by paternity uncertainty in our evolutionary past and it will take more than an improvement in women’s employment options to address the problem of spousal violence.

Women who witness their mothers experiencing domestic violence tend to accept it in the form of a societal norm (Singh and Singh, 2013; Visaria, 2008). This is not the case only with India as Cascardi and O’Leary (1992) found that a lot of domestic violence victims often tend to blame themselves for their victimization in the case of American women. Similarly, in the neighbouring country, Pakistan, domestic violence is transmitted as learned behavior from mothers to daughters who tend to accept such violation of human rights as normal (Aslam et al., 2015). Walker (1979) stresses on how women experiencing unpredictable and uncontrollable forms of domestic violence are highly likely to show signs of learned helplessness and sunken self-confidence. Moreover, lack of self-confidence among women increases their chances of experiencing domestic violence. Hence, women are trapped in a vicious circle of low self-confidence and domestic violence (Parrado et al., 2005; Yawn et al., 1992).

Studies have hinted that better education empowers women and gives them the strength to protect themselves against domestic violence (Sultana, 2010). Besides, this effect may get enlarged when the education achieved by the current generation woman is more than her previous generation, i.e., her mother. Also, several studies have related upward intergenerational educational mobility with increase in self confidence and reduction in chances of experiencing depressive episodes (Chevalier et al., 2003; Gugushvili et al., 2019). Furthermore, an increased self-confidence empowers women to recognize and resist abusive behaviors, thereby reducing their chances of experiencing domestic violence (Kiani et al., 2021). Expanding upon the aforementioned research, our study investigates the phenomenon where daughters who surpass their mothers in educational attainment not only experience overall improvement in self confidence, but also obtain further advantages. The daughter’s recognition of her greater educational achievements compared to her mother significantly enhances her sense of accomplishment. This strengthens their self-confidence, empowering them to challenge the societal conventions and obstacles that restrict their personal development with better education as the first milestone. Daughters who have a higher level of education than their moms are more likely to have a more profound comprehension of the fact that they are not obligated to go through unpleasant experiences that their mothers had to endure. Therefore, this study examines how education of a woman which is more than that of her mother, i.e., upward intergenerational educational mobility affects her chances of experiencing domestic violence in India. This perhaps is a novel attempt to demonstrate this relationship not just in the Indian context but also in the global scholarship on domestic violence and thus adding to the findings of Gugushvili et al. (2019). To carry out this research we have used data from the “Youth in India: Situations and needs” survey. We have used logistic regression with chances of experiencing domestic violence as the main dependent variable and intergenerational educational mobility as the main explanatory variable. We have controlled for various other circumstances of the woman.

Our findings suggest that women with a higher level of education as compared to their mothers have significantly lesser odds of experiencing domestic violence.

The paper is further organized as follows: the next section documents a brief review of studies on domestic violence, following presents the details of the materials and methods in the order data and research methodology used for the current study, followed by results and finally some discussion on the main findings followed by some concluding remarks.

Brief review of scholarship

Domestic violence is an intensely scrutinized phenomenon among researchers across the globe. Scholarship on domestic violence started to evolve in early 1970s and a profusion of research has been done till date to study its pattern and prevalence among women across the world (Bowker, 1983; Dobash and Dobash, 1979; Gelles, 1974; Kalokhe et al., 2015; Kirkwood, 1993; Martin, 1976; Nielson et al., 1979; Pagelow, 1981; Pence and Paymar, 1993; Rocca et al., 2008; Steinmetz and Straus, 1974; Straus and Hotaling, 1980; Krishnan et al., 2012; Piedalue, 2015; Sreelatha et al., 2021; Kamat et al., 2013; Samal and Poornesh, 2022; Burke et al., 2004; Dalal, 2011; Fleming et al., 2015; Gage and Thomas, 2017; Gupta et al., 2013; Raj et al., 2018; Schuler et al., 2018). Jewkes et al. (2002) indicates that educationally, economically, and socially empowered women are the most protected, but below this high level the relationship between empowerment and risk of violence is nonlinear. The relationship between women empowerment and domestic violence is highly ambiguous. Having a job can enhance emotional well-being by providing economic stability for women, which in turn can decrease incidents of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Buller et al., 2018). However, it is possible that this could provoke aggressive reactions from partners who perceive their own status as being endangered or who aim to gain some of the additional riches that come with the employment. According to Heath and Jayachandran (2016), the incidence of intimate partner violence (IPV) rises as more women are employed, the overall benefit of female employment at the individual level becomes unpredictable.

There is sizeable body of scholarly work which supports empowerment of women through education, employment, financial autonomy, strong social support; higher socio-economic status are less susceptible to domestic violence (Rapp et al., 2012; Kishor and Johnson, 2006; Jeyaseelan et al., 2007). Rapp et al. (2012) suggests that women who have a greater level of education than their husbands are often less susceptible to experiencing domestic violence compared to women who have a lower level of education than their husbands. In addition, women who are working and have financial autonomy are less prone to encountering domestic abuse (Kishor and Johnson, 2006). Furthermore, Jeyaseelan et al. (2007) found that having a higher socioeconomic position and strong social support served as effective safeguards against spousal physical abuse among Indian women. According to classical ideas of household bargaining, economic empowerment can enhance women’s opportunities outside of the household and decrease their likelihood of encountering violence (Erten and Keskin, 2018). Aizer (2010) shows that a decline in the male–female wage gap in a household reduces violence against women.

On contrary to the above findings, women and girls who are thought to be violating traditional gender roles established by a male-dominated society are more vulnerable to experiencing sexual abuse (Kelly-Hanku et al., 2016). Furthermore, the prevalence of spousal violence was higher for women who are employed than women who are not (Agnes, 2019). Moreover, Lim (1997) hints that patriarchy, a system where men dominate over women and treat them as subordinates in any society, is responsible for the inferior or secondary status of women, which often leads to gender based violence as well. On a similar note, Visaria (2008) finds that the socioeconomic background of a woman does not make much difference, as a significant proportion of women accept the subordinate status to their husband because of the power associated with the gender. Even education does not empower women to enter the public arena for support. Better educated women or those belonging to better-off families who experience violence are least likely to share their experiences or seek support from others (Visaria, 2008). An augmentation in the resources accessible to women could potentially enhance men’s motivations to employ violence or the act of making threats of violence as a means to exert control over these recently acquired resources (Bloch and Rao, 2002; Eswaran and Malhotra, 2011; Bobonis et al., 2013). Furthermore, an enhancement in women’s ability to negotiate, such as through improved job prospects, could result in a negative reaction from their partners, who may have a preference for women not being employed (Field et al., 2016). Consequently, women may be more susceptible to mistreatment.

Above discussed are a few studies from the ocean of literature on domestic violence that we found relevant for our current study. Several studies have stressed upon education being the game changer to eradicate domestic violence whereas, others suggest that education does not play a significant role to improve women’s condition as far as domestic violence is concerned. Domestic violence turns out to be a highly complex phenomenon and therefore arises the need to conduct further studies to understand the dynamics around domestic violence experienced by women in Indian setting. To the best of our search we could not find any scholarship which looks into how an education of a daughter which is more than that of her mother can affect her chances of experiencing domestic violence. Thus, the current study will explore a new direction to study the dynamics of domestic violence among women in India and significantly contribute to the scholarship on domestic violence.

Materials and methods

Materials (data)

We have used data from the “Youth in India: Situations and needs” survey. The survey was conducted in the year 2006–07 by the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai (India) and the Population Council, New Delhi (India) under the stewardship of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Population Council, 2010).

The Youth in India: Situation and Needs study (also referred as the Youth Study), is the first-ever sub nationally representative study conducted to understand the conditions and needs of the young people in India (Choudhary and Singh, 2017; International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Population Council, 2010; Singh et al., 2014; Choudhary and Singh, 2020).

Two steps were involved in the selection of the rural area sample. Using a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling approach, villages were first chosen. Using a systematic sample scheme, households were chosen for the second step of the process. The sample was chosen in three phases for urban areas. Wards were methodically chosen in the first round of selection using the PPS sampling procedure. Using the PPS sampling scheme, census enumeration blocks (CEBs) of between 150 and 200 homes were chosen for the second stage. At the third stage, households were chosen through the use of a systematic sampling process. Interviews with 50,848 young men and women, married or single, were conducted with success. For one-on-one interviews, response rates ranged from 84 to 90% (Choudhary and Singh, 2017; International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Population Council, 2010; Singh et al., 2014).

For this study purpose, we have restricted our analysis to married women aged 15–24 years only. The details of the sampling weight used for analysis are given in the survey report (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Population Council, 2010).

Although the Youth in India: Situation and Needs study is a very comprehensive survey, it does have certain limitations. For the entire survey, 50,848 young men and women were interviewed however, after constructing the final model for the analysis which included only ever married women and women with missing values for any of the variables in the study were dropped. The Final sample of the eligible women for the analysis after dropping all missing was 10,498.

Besides, the given data set provides a great opportunity for a cross-sectional analysis for the pre COVID period demographic landscape (as the data collection happened in 2006–07) and on the same time suffers from the limitation of not able to provides insights which reflect longer-term trends and dynamics.

Methods

Outcome of interest: measure of gender based domestic violence

The outcome of interest in the current study is domestic violence experienced by ever married woman. This variable is dichotomous in nature (experienced domestic violence: Yes/No). The below mentioned criteria has been used to identify whether an ever married woman has faced domestic violence: she is a victim of domestic violence: if her spouse has intentionally attempted to strangle her or burn her, threatened or attacked her with a knife, gun, or other weapon, or slapped her, twisted her arm, pulled her hair, shoved, shook, or flung something at her; punched her with his fist or something sharp; kicked, dragged, or beat her up. This identification has been adopted from the survey report (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Population Council, 2010) and is also in line with Singh and Singh (2013).

Main explanatory variable and control variables

Intergenerational educational mobility of the ever married women is the main explanatory variable of interest. The data captures education of the women as well as their mother in terms of years of education. For the analysis it is categorized in two categories: (i) education of the daughter is more than that of her mother; and (ii) education of daughter is equal to or less than that of her mother. Drawing from the published literature on determinants of domestic violence (Caesar, 1988; Ellsberg et al., 1999; Heise, 1998; Hotaling and Sugarman, 1986; Jewkes et al., 2002; Kalmuss, 1984; Martin et al., 2002; Singh and Singh, 2013; Straus and Gelles, 1989; Sugarman and Hotaling, 1989) and other relevant factors in the Indian context, we have included the following control variables in the regression based analysis.

(i) Individual level variables:

(a) Choice of marriage (categorical) – arranged marriage or love marriage.

(b) Duration of marriage in years – we also considered inclusion of age of the women in the analysis but the correlation between “age in years” and “duration of marriage in years” was substantially high (0.6) and significant at 0.1% level of significance; given that the women included in the analysis are 15–24 years old which is not a wide range and “duration of marriage in years” is a more relevant variable in the present context, we decided to include it and drop “age in years” from the regression based analyzes; and

(ii) Household/familial level variables:

(a) Occupational status of the husband (categorical) – the survey captures the occupational status of husbands as: not working/unemployed/retired (1); cultivator (2); Agricultural laborer (3); non-agricultural laborer (4); administrative/executive and managerial (5); skilled (manual, machinery) (6); clerical (7); and other workers (8).

(b) Husband Consumes Alcohol (categorical-yes or no, married women were asked about the members of family who consume alcohol) – this variable has been taken for analysis as a lot of researchers suggested for a positive relation between Husband’s alcohol consumption habits and domestic violence (Krishnan, 2005; Rao, 1997).

(c) Whether mother has experienced domestic violence (categorical – yes or no, the identification criteria for domestic violence being same as that used to capture the outcome variable) – we included this variable because there is a strong scholarship base which supports the intergenerational transmission of domestic violence from mother to the daughter (Caesar, 1988; Choudhary and Singh, 2020; Ellsberg et al., 1999; Heise, 1998; Hotaling and Sugarman, 1986; Jewkes et al., 2002; Kalmuss, 1984; Martin et al., 2002; Singh and Singh, 2013; Straus and Gelles, 1989; Sugarman and Hotaling, 1989; Visaria, 2008). This variable allows us to capture the intergenerational nature of domestic violence among women in India.

(d) Type of family (categorical-nuclear family or non-nuclear family) – this variable has been taken as a control variable as existing research has hinted that non-nuclear family setup reduces the chances of experiencing domestic violence for women (Kalokhe et al., 2015).

(e) Wealth (presented in form of wealth quintiles) – Wealth quintiles have been taken into analysis to present the economic status of the woman’s family.

(f) Brought dowry at the time of wedding (categorical-yes or no) –a lot of scholarly work has supported dowry as one of the main reasons for the occurrence of domestic violence against married women (Kalokhe et al., 2015). Thus, controlling for dowry will certainly enhance our model.

(g) Caste1 (categorical – scheduled castes and tribes [SC/ST], other backward castes [OBC] and Others) – the above categorization is a meaningful representation of the Indian social fabric along caste lines (Singh and Singh, 2013).

(h) Religion – religion has been divided into three categories, namely “Hindu” (the majority religious group in the Indian population), “Muslim” (largest group among religious minorities) and “Others”.

(iii) Community/societal level variables – rural/urban and state dummies for the pooled sample analysis.

Regression model

We have modelled the association between the ever married young women’s experiences with domestic abuse and their intergenerational educational mobility using logistic regression. Intergenerational educational mobility serves as the primary explanatory variable of interest for the domestic violence that women experience, coupled with a few control factors that were covered in the preceding subsection. There is always a possibility of a high degree of multicollinearity between various control variables. In addition, we ran multicollinearity tests [the Variance Inflation Factor [VIF] test and the Condition Index test, which were suggested by Belsley (1991) and Hill et al. (2003)], but we were unable to detect any indication of multicollinearity that was statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Sample composition by individual, household and community level factors

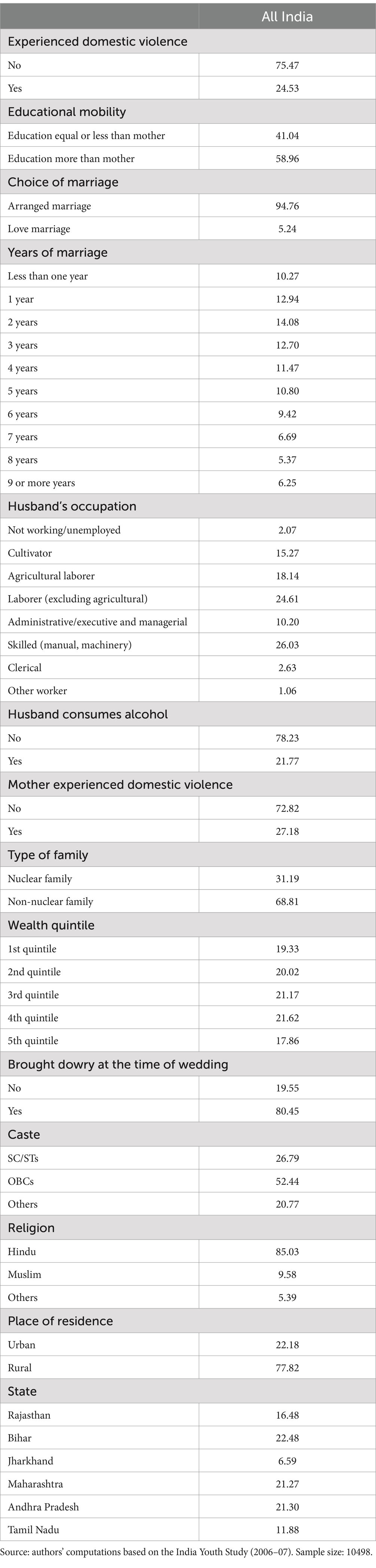

Table 1 and Figure 1 present the composition of the sample by various individual, household and community level variables. The table represents the above for the All-India level (strategically chosen six states representing Indian population). Some key findings from the Table 1 are as follows: (1) about 25% of women experienced domestic violence; (2) while looking at the intergenerational educational mobility, about 59% women reported to have education more than their mother while rest had less or equal education vis-a-vis their mother; (3) the fact that around 12% of the women in the age group of up to 24 years (as covered by the dataset) have been married for 8 years or more highlights the prevalence of child marriages in India; (4) 22% of the husbands reportedly consumed alcohol whereas the percentage of men consuming alcohol in three regions identified by WHO – the Americas, Europe and Western Pacific is as high as 50% (WHO, 2018); (5) about 27% of women reported that their mothers experienced domestic violence; (6) around 69% of women have reported to live in joint or non-nuclear families; (7) about 80% women reported to have brought dowry at the time of their wedding; (8) around 78% of women live in rural areas.

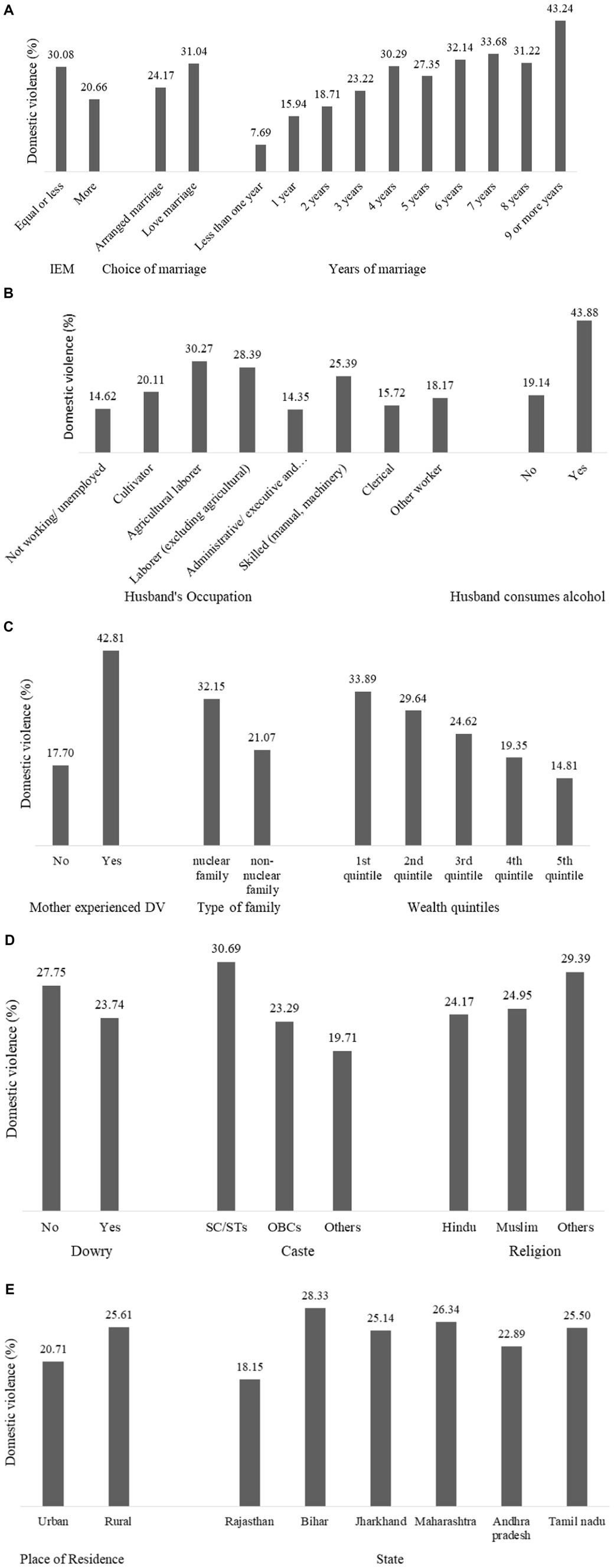

Figure 1. Experience of domestic violence by individual, household and community level factors. Source: based on authors’ calculations from India Youth Survey (2006–07). (a) Domestic violence experienced by ever married women by Intergenerational educational mobility (IEM), choice and years of marriage. (b) Domestic violence experienced by ever married women by husband’s occupation and alcohol consumption. (c) Domestic violence experienced by ever married women by mother’s experience of domestic violence, type of family and wealth quintiles. (d) Domestic violence experienced by ever married women by dowry, caste and religion. (e) Domestic violence experienced by ever married women by area and states.

Experience of domestic violence by individual, household and community level factors

There are several interesting patterns which can be observed from the data and also presented in the prevalence of domestic violence among the women by various socio-economic factors. The key patterns are as follows: (1) daughters who achieved education more than their mothers, 20% of them experienced domestic violence, whereas, 30% of daughters experienced domestic violence who were equal or less educated than their mothers; (2) percentage of women experiencing domestic violence is more in case of love marriage (31%) as compared to that of arranged marriage (24%).

It presents the prevalence of domestic violence among women by husband’s occupation and consumption of alcohol by him. Key findings are as follows: (1) prevalence of domestic violence among women is as high as 30 and 28% when husbands are involved in agricultural labour or other labor activities respectively; (2) On the other hand if husbands are not working, or doing administrative jobs or clerical jobs prevalence of domestic violence among their wives is comparatively less (14 to 15%) as compared to others; (3) prevalence of domestic violence among women is as high as 44% whose husbands consume alcohol as compared to 19% whose husbands do not consume alcohol.

The study also presents the prevalence of domestic violence among women by their various socio-economic characteristics of family such as mother experienced domestic violence, type of current family and wealth quintile their family fall into. There are interesting patterns about prevalence of domestic violence by Indian women worth noting are as follows: (1) about 43% women whose mothers experienced domestic violence also experienced domestic violence; (2) whereas, only 18% of women experienced domestic violence whose mothers did not experience domestic violence; (3) about 32% of women experienced domestic violence who were staying in nuclear families as compared to 21% in non-nuclear family; (3) percentage of women experiencing domestic violence falls as we move from low wealth group to high wealth group from 34 to 15%.

We also present the percentage of women experiencing domestic violence by dowry, caste and religion. Some prominent facts are as follows: (1) proportion of women experiencing domestic violence who brought dowry at the time of their wedding is 24% as compared to that of 28% who did not bring dowry at the time of their wedding; (2) proportion of women who reported to have experienced domestic violence from SC/STs, OBCs and Others caste group is 31, 23 and 20%, respectively.

The study also presents the presence of domestic violence among women by their place of residence (rural/urban) and states. Proportion of women experiencing domestic violence is higher in rural areas (26%) as compared to urban areas (21%). While looking at the percentage of women who experienced domestic violence by state it was lowest in Rajasthan (18%) and the highest in Bihar (28%).

Regression results

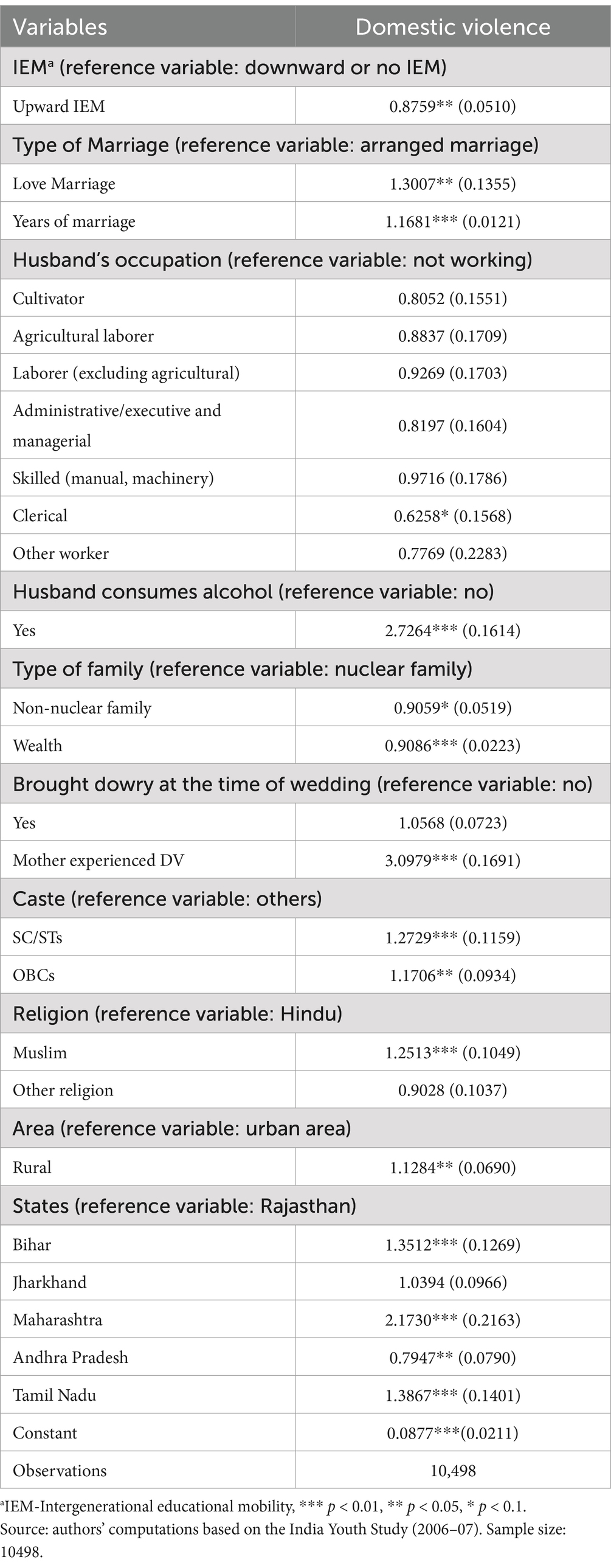

The main results from the multivariate analysis have been presented in Table 2 and discussed in the following paragraphs.

Firstly, women who achieve education which is more than that of their mother have significantly lesser odds of experiencing domestic violence as compared to that of women who ended up having equal or lesser number of years of education vis-à-vis their mothers. Secondly, chances of experiencing domestic violence increase significantly when they are in a love marriage as compared to an arranged marriage.

We have also analyzed the effect of husband’s occupation on the women’s chances of experiencing domestic violence. The interdependence though is not as significant based on the inferential analysis for most occupational categories but in case of the husbands being employed in clerical jobs the chances of experiencing domestic violence are significantly reduced. Likewise, husband’s job insecurity has also been related to increased chances of experiencing domestic violence by women which supports the current findings (Schneider et al., 2016). Tur-Prats (2021) argues in Spain when females unemployment rate goes down in comparison to that of males prevalence of domestic violence increases. However, husband’s alcohol consumption habit is a highly significant factor in determining the chances of experiencing domestic violence by their wives. The odds of experiencing domestic violence by a woman is as high as 2.7 times when husband consumes alcohol as compared to that of a woman whose husband does not consume alcohol. Further, we see women living in non-nuclear families have significantly lesser chances (odds ratio 0.905) of experiencing domestic violence vis-à-vis women living in nuclear families. It can also be seen from Table 2 that as the wealth increases the chances of experiencing domestic violence by a woman go down (odds ratio 0.908). Moving forward to the next factor in Table 2, it is quite surprising to see that dowry brought by women at the time of their wedding is not a significant factor in determining her chances of experiencing domestic violence.

Notably, mothers being victims of domestic violence augment their daughter’s chances of experiencing the same. The odds ratio for experiencing domestic violence for women whose mothers have experienced it too is as high as 3.09 (with a p value less than 0.01).

Furthermore, caste too affects the chances of experiencing domestic violence for women. Women from SC/STs (odds ratio 1.27) and OBCs (odds ratio 1.17) have significantly higher odds of experiencing domestic violence as compared to that of women from Others (Upper caste). Similarly, religion is also a significant factor, Muslim women (odds ratio 1.25) have significantly higher chances of experiencing domestic violence as compared to Hindu women.

Moving to community level factors, our analysis shows that the chances of experiencing domestic violence vary significantly from one state to another as well as from urban to rural areas. Women from rural areas (odds ratio 1.12) have significantly higher chances of experiencing domestic violence as that of women living in urban areas. While looking at the odds ratio of experiencing domestic violence for states, it can be seen that Bihar (odds ratio 1.35), Maharashtra (odds ratio 2.17) and Tamil Nadu (odds ratio 1.38) have significantly higher odds of experiencing domestic violence as compared to that of Rajasthan. Whereas, women from Andhra Pradesh (odds ratio 0.79) have significantly lower chances of experiencing domestic violence as compared to that of Rajasthan.

Our findings from the regression results call for further discussion.

Discussion

Most of the prior research on domestic violence has emphasized upon better educational and health outcomes as effective measures for combating domestic violence. Studies have indicated a correlation between women’s education and domestic violence, indicating a change in the way women think and a declining degree of control between husband and wife (Sen et al., 2002). However, as our results suggest, a mere quantitative increase in the educational attainments that is now available to a majority of women in India will not substantially alter their risk. For instance, the odds of domestic violence are higher in states like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu with better overall educational attainments for women as compared to educationally backward states such as Rajasthan and Jharkhand. These better economic and sociological indicators may contribute to a considerable extent but still their direct effect is questionable in light of these findings. It is therefore important to conduct further research on this complex social issue and look for alternative approaches and solutions. Qualitative aspects of women’s education such as intergenerational educational mobility can therefore provide for vital policy inputs.

With our due cognisance of the various familial characteristics and patterns that prevail in India prompted us to look into the aspect of intergenerational transmission of domestic violence. As suggested by our results, women who reported their mothers experiencing domestic violence have significantly higher chances of experiencing domestic violence compared to women who did not. This can also be attributed to the normalization or the gradual acceptance of the wrong of domestic violence as a societal right. The resistance from such women is low as compared to the women whose mothers have not experienced domestic violence leading to the exacerbating of the power imbalance in the marriage.

A daughter growing up in such a flourishing atmosphere for intergenerational transmission of domestic violence is more likely to accept such occurrences herself without exercising much restraint. Unless otherwise provided with an impetus such a daughter will tolerate and further allow her partner to propagate the heinous act of violence in the private sphere. The daughter might internalise the act of domestic violence as normal. A daughter’s expectation of better life outcomes for herself as compared to her mother on account of upward Intergenerational educational mobility can provide for this much needed impetus.

Notwithstanding whether her mother experienced domestic violence or not, a woman any how requires the inner strength and courage to stand against this manifestation of male hegemony in the form of physical or verbal abuse. In the majority of countries with available data, less than 40 per cent of the women who experience violence seek help of any sort (Caesar, 1988). This lack of resistance on the woman’s part can largely be attributed to her low morale resulting from an all-pervasive normalization of gender discrimination (Bartholini, 2020). A woman’s appreciation of her higher level of education vis-a-vis her mother can uplift her morale thereby empowering her to exercise restraint against any untoward incidents. This explains the findings of this study that suggest that women with upward intergenerational educational mobility have significantly lower chances of experiencing domestic violence.

Another important finding from our regression results suggests that women who choose love marriage have significantly higher chances of experiencing domestic violence than that of an arranged marriage. This finding is surprising and further research is imperative for a better understanding. However, it can be reasonably concluded that it is due to the perceived helplessness of the woman in a love marriage on account of the lack of support from her natal family that otherwise serves as a deterrent (Heise, 1998).

Furthermore, as suggested by the results, the number of years for which a woman has been married increases, her chances of experiencing domestic violence also increase significantly. Anecdotally it can be said that the chances increase due to the increased exposure with the increase in the number of years. At the same time there may be other factors such as enhanced responsibilities and an increase in the number of children that results in deteriorating the economic status of the household with the increase in the number of years of marriage. The added stress in the family leads to higher rates of domestic violence (Kimuna et al., 2013). These findings further confirm the relevance of policies targeted at delaying the age of marriage in reducing the prevalence of domestic violence in a less developed country like India (Dhamija and Roychowdhury, 2018).

Besides, women who reported their husbands being alcohol consumers are highly likely to experience domestic violence than the ones whose husbands do not consume alcohol. This interrelation has been well captured by prior research on the subject matter and our research further substantiates the findings (Duran et al., 2009; Gokler et al., 2014; Krishnan, 2005; Leadley et al., 2000; Markowitz, 2000; Rao, 1997).

Regression results also suggest that living in a non-nuclear family provides for a natural check on the husband’s impulsive or violent behavior. The intervention from the family can also assist the women in coping with violence by her husband but at the same time there is another form of harassment or psychological abuse the women has to undergo on account of living in a non-nuclear family (Deshpande and Suleiman, 2014; George et al., 2016). The women’s individual liberties are significantly suppressed whether in the name of customs, traditions, family honour or societal norms in a non-nuclear household. Therefore, the overall effect of the type of family alone on the prevalence of domestic violence cannot be conclusively ascertained.

Our regression results further substantiate that women from socially backward and disadvantaged caste groups such as SC/STs and OBCs are at a higher risk of experiencing domestic violence as compared to women from upward castes. This particular aspect has been well documented in existing literature (Visaria, 2008). Likewise, a woman in a Muslim family has higher chances of experiencing domestic violence than a woman in a Hindu family.

Moreover, women from rural areas also require special attention from the policymakers as women there have significantly higher chances of experiencing domestic violence. In addition, women from rural areas have relatively lower upward intergenerational educational mobility due to lack of access to schools and other opportunities (Choudhary and Singh, 2017, 2019).

Conclusion

To unfold suitable interventions to advise policymakers to curb prevalence of domestic violence, it is crucial to analyze the determinants of it. Researchers have often advised education and employment as a way to empower women to combat domestic violence. However, the most developed parts of the world where women are reasonably well educated are still vulnerable to the evils of domestic violence. This is not just disheartening but also shows that merely educational attainments do not affect the chances of domestic violence to a large extent. It is probably the confidence a woman derives on account of better educational attainments as compared to her previous generation that influences her take on the menace of domestic violence. In spite of that, this relationship between intergenerational educational mobility and domestic violence among women has been untouched by the researchers so far. That said, there are some major gaps in the evidence base that need to be addressed. Our study makes humble attempt in that direction and the results from regression are quite encouraging that how women with upward intergenerational educational mobility have significantly lesser chances of experiencing domestic violence, their odds of experiencing domestic violence reduce to 0.87 (statistically significant) with a p value of less than 0.05.

A woman being more educated than her mother is more likely to enjoy a say in the day to day decision making in her natal household (Choudhary and Singh, 2017). Instead of being a passive recipient she is an active contributor in decision making and this lays the foundation for a participative and democratic spirit in the women. Such women are more likely to participate in the decision making in their married lives as well. Besides, democratisation of decision making power or increase in the bargaining power at home encourages women to question the menace of domestic violence and therefore, stops the internalisation process of domestic violence and thus reducing the act itself (Shirwadkar, 2009).

Since marriage and family is a private institution the state is severely restricted in its ability to provide for a coping mechanism by direct intervention. It is highly imperative that the state should work upon devising indirect interventions and our research on the effect of intergenerational educational mobility on a woman’s chances of experiencing domestic violence provides a ready reckoner in this regard. However the findings of the study do face certain limitations, which also paves way to future scope of research to strengthen the arguments presented here as well as offer insights about the results from this study. In case of less developed countries where the disparities in educational attainments are starker than that in developed countries, findings of our research are very crucial. In the Indian context, there is a lot to achieve when it comes to educational attainmentsfor women as well as men. This backwardness can be leveraged to combat the menace of domestic violence if it is overcome in a well deliberated manner having due regard to the positive social outcomes of upward educational mobility. The need for inclusion of intergenerational educational mobility studies into policy planning becomes all the more crucial when we consider the impact of upward intergenerational educational mobility on other aspects of woman’s wellbeing such as health (Choudhary and Singh, 2018).

Limitations and scope for future work

In order to strengthen our findings, it is necessary to conduct further studies to validate these results and gain a more comprehensive understanding of the observed connections. The findings of this study particularly explain Indian setting. While the dataset from 2006–07 may be considered old and may not capture post COVID effects, its richness provides valuable insights into the human dynamics of that period, significantly contributing to our understanding and paving the way for further research in this field. We anticipate that our research will inspire more studies on the important topic of how upward intergenerational educational mobility influences the likelihood of experiencing domestic violence. This, in turn, will aid in developing appropriate policy recommendations to address the issue of domestic violence, which is of great importance.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the rigorous review by the 2 reviewers, whose insightful comments have been instrumental in enhancement of this manuscript. Additionally, we are also grateful for the valuable feedback received from the participants of the SASE 2024 conference at the University of Limerick, Ireland.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Scheduled castes and scheduled tribes are historically most disadvantaged and most discriminated against groups in India, other backward castes have also been historically disadvantaged and discriminated against but not so much as the scheduled groups. ‘Others’ Caste group represent socially advantaged caste groups which are not part of SCs, STs or OBCs.

References

Agnes, F. (2019). What survivors of domestic violence need from their new government. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 54, 7–8.

Aizer, A. (2010). The gender wage gap and domestic violence. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 1847–1859. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.4.1847

Alesina, A., Michalopoulos, S., and Papaioannou, E. (2016). Ethnic inequality. J. Political Econ 124, 428–488.

Aslam, S. K., Zaheer, S., and Shafique, K. (2015). Is spousal violence being “vertically transmitted” through victims? Findings from the Pakistan demographic and health survey 2012-13. PLoS One 10:e0129790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129790

Bartholini, I. (2020). The trap of proximity violence: research and insights into male dominance and female resistance. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature.

Belsley, D. A. (1991). A guide to using the collinearity diagnostics. Comput. Sci. Econ. Manag. 4, 33–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00426854

Bhattacharyya, P., Songose, L., and Wilkinson, L. (2021). How sexual and gender-based violence affects the settlement experiences among Yazidi refugee women in Canada. Front. Hum. Dyn. 3:644846. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.644846

Bloch, F., and Rao, V. (2002). Terror as a bargaining instrument: A case study of dowry violence in rural India. https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=a529d2bbd18813642fe111d8f990b893c71cc906688e365de8a8501b1b04dae1JmltdHM9MTczMzQ0MzIwMA&ptn=3&ver=2&hsh=4&fclid=0a36bd81-9d55-6a63-3aec-a9089c356b25&u=a1L3NlYXJjaD9xPUFtZXJpY2FuK0Vjb25vbWljK1JldmlldyZGT1JNPVNOQVBTVCZmaWx0ZXJzPXNpZDoiYjYzYTQ1YmQtMjg0ZC0wMzU4LWM5MTYtZDQyNzc1YTllNGMwIg&ntb=1AER, 92, 1029–1043.

Bobonis, G. J., González-Brenes, M., and Castro, R. (2013). Public transfers and domestic violence: The roles of private information and spousal control. Am Econ J Econ Policy, 5, 179–205.

Buller, A. M., Peterman, A., Ranganathan, M., Bleile, A., Hidrobo, M., and Heise, L. (2018). A mixed-method review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in low-and middle-income countries. World Bank Res. Obs. 33, 218–258. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lky002

Burke, J. G., Denison, J. A., Gielen, A. C., McDonnell, K. A., and O’Campo, P. (2004). Ending intimate partner violence: An application of the transtheoretical model. Am. J. Health Behav. 28, 122–133.

Caesar, P. L. (1988). Exposure to violence in the families-of-origin among wife-abusers and maritally nonviolent men. Violence Vict. 3, 49–63. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.3.1.49

Cascardi, M., and O’Leary, K. D. (1992). Depressive symptomatology, self-esteem, and self-blame in battered women. J. Fam. Violence 7, 249–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00994617

Chevalier, A., Denny, K., and McMahon, D. (2003). A multi-country study of inter-generational educational mobility (no. WP03/14. Dubli: Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series.

Choudhary, A., and Singh, A. (2017). Are daughters like mothers: evidence on intergenerational educational mobility among young females in India. Soc. Indic. Res. 133, 601–621. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1380-8

Choudhary, A., and Singh, A. (2018). Effect of intergenerational educational mobility on health of Indian women. PLoS One 13, 1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203633

Choudhary, A., and Singh, A. (2019). Do Indian daughters shadow their mothers? Int. J. Soc. Econ. 46, 1095–1118. doi: 10.1108/IJSE-10-2018-0499

Choudhary, A., and Singh, A. (2020). “Experience of domestic violence by young women in India: does the nature of occupation play any role?” in Population change and public policy (Cham: Springer), 295–320. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-57069-9_15

Dalal, K. (2011). Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence? JIVR 3:35.

Deshpande, H., and Suleiman, G. A. (2014). Age, family type and domestic conflict in Bangalore. (NIAS report no. R21-2014).

Dhamija, G., and Roychowdhury, P. (2018). The causal impact of Women’s age at marriage on domestic violence in India. Available at SSRN 3180601.

Dobash, R. E., and Dobash, R. (1979). Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy. New York: Free Press Accessed 11 November 2023.

Duran, B., Oetzel, J., Parker, T., Malcoe, L. H., Lucero, J., and Jiang, Y. (2009). Intimate partner violence and alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among American Indian women in primary care. Am. Indian Alaska Native Mental Health Res. 16, 11–27. doi: 10.5820/aian.1602.2009.11

Ellsberg, M. C., Pena, R., Herrera, A., Liljestrand, J., and Winkvist, A. (1999). Wife abuse among women of childbearing age in Nicaragua. Am. J. Public Health 89, 241–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.2.241

Erten, B., and Keskin, P. (2018). For better or for worse?: education and the prevalence of domestic violence in Turkey. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 10, 64–105. doi: 10.1257/app.20160278

Eswaran, M., and Malhotra, N. (2011). Domestic violence and women's autonomy in developing countries: theory and evidence. Canadian J. Econ. 44, 1222–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5982.2011.01673.x

Field, R., Jeffries, S., and Rathus, Z., and Lynch, A. (2016). Family reports and family violence in Australian family law proceedings: What do we know. JJA, 25, 212–236.

Fleming, P. J., Gruskin, S., Rojo, F., and Dworkin, S. L. (2015). Men’s violence against women and men are inter-related: Recommendations for simultaneous intervention. Soc Sci Med 146, 249–256.

Gage, A. J., and Thomas, N. J. (2017). Women’s work, gender roles, and intimate partner violence in Nigeria. Arch. Sex. Behav. 46, 1923–1938.

Gahramanov, E., Gaibulloev, K., and Younas, J. (2022). Does property ownership by women reduce domestic violence? A case of Latin America. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 36, 548–563. doi: 10.1080/02692171.2021.1965551

George, J., Nair, D., Premkumar, N. R., Saravanan, N., Chinnakali, P., and Roy, G. (2016). The prevalence of domestic violence and its associated factors among married women in a rural area of Puducherry, South India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 5, 672–676. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.197309

Gokler, M. E., Arslantas, D., and Unsal, A. (2014). Prevalence of domestic violence and associated factors among married women in a semi-rural area of western Turkey. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 30, 1088–1093. doi: 10.12669/pjms.305.5504

Gugushvili, A., Zhao, Y., and Bukodi, E. (2019). ‘Falling from grace’and ‘rising from rags’: intergenerational educational mobility and depressive symptoms. Soc. Sci. Med. 222, 294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.027

Gupta, J., Falb, K. L., Lehmann, H., Kpebo, D., Xuan, Z., Hossain, M., et al. (2013). Gender norms and economic empowerment intervention to reduce intimate partner violence against women in rural Côte d’Ivoire: a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 13, 1–12.

Hall, J. (2000). It hurts to be a girl: growing up poor, white, and female. Gend. Soc. 14, 630–643. doi: 10.1177/089124300014005003

Heath, R., Hidrobo, M., and Roy, S. (2020). Cash transfers, polygamy, and intimate partner violence: experimental evidence from Mali. J. Dev. Econ. 143:102410. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102410

Heath, R., and Jayachandran, S. (2016). The causes and consequences of increased female education and labor force participation in developing countries. Massachusetts Avenue: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women 4, 262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002

Hill, R. C., Adkins, L. C., and Bender, K. A. (2003). “Test statistics and critical values in selectivity models” in Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Misspecified Models: Twenty Years Later (Emerald Group Publishing Limited).

Hotaling, G. T., and Sugarman, D. B. (1986). An analysis of risk markers in husband to wife violence: the current state of knowledge. Violence Vict. 1, 101–124. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.1.2.101

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Population Council (2010). Youth in India: Situation and needs 2006–2007. Mumbai: IIPS, 396.

Jejeebhoy, S. J. (1998). Wife-beating in rural India: a husband’s right? Evidence from survey data. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 54, 855–862.

Jewkes, R., Levin, J., and Penn-Kekana, L. (2002). Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a south African cross-sectional study. Soc. Sci. Med. 55, 1603–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00294-5

Jeyaseelan, L., Kumar, S., Neelakantan, N., Peedicayil, A., Pillai, R., and Duvvury, N. (2007). Physical spousal violence against women in India: some risk factors. J. Biosoc. Sci. 39, 657–670. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007001836

Kalmuss, D. (1984). The intergenerational transmission of marital aggression. J. Marriage Fam. 46, 11–19. doi: 10.2307/351858

Kalokhe, A. S., Potdar, R. R., Stephenson, R., Dunkle, K. L., Paranjape, A., del Rio, C., et al. (2015). How well does the World Health Organization definition of domestic violence work for India? PLoS One 10:e0120909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120909

Kamat, U. S., Ferreira, A., Mashelkar, K., Pinto, N. R., and Pirankar, S. (2013). Domestic violence against women in rural Goa (India): prevalence, determinants and help-seeking behaviour. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 3, 65–71.

Kamath, A., Yadav, A., Baghel, J., and Mundle, S. (2022). Locked down: experiences of domestic violence in Central India. Global Health: Science and Practice. 10:e2100665. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00665

Kelly-Hanku, A., Aeno, H., Wilson, L., Eves, R., Mek, A., Nake Trumb, R., et al. (2016). Transgressive women don’t deserve protection: young men’s narratives of sexual violence against women in rural Papua New Guinea. Cult Health Sex 18, 1207–1220. Available at: https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=a529d2bbd18813642fe111d8f990b893c71cc906688e365de8a8501b1b04dae1JmltdHM9MTczMzQ0MzIwMA&ptn=3&ver=2&hsh=4&fclid=0a36bd81-9d55-6a63-3aec-a9089c356b25&u=a1L3NlYXJjaD9xPUFtZXJpY2FuK0Vjb25vbWljK1JldmlldyZGT1JNPVNOQVBTVCZmaWx0ZXJzPXNpZDoiYjYzYTQ1YmQtMjg0ZC0wMzU4LWM5MTYtZDQyNzc1YTllNGMwIg&ntb=1

Kiani, Z., Simbar, M., Fakari, F. R., Kazemi, S., Ghasemi, V., Azimi, N., et al. (2021). A systematic review: empowerment interventions to reduce domestic violence? Aggress. Violent Behav. 58:101585. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2021.101585

Kimuna, S. R., Djamba, Y. K., Ciciurkaite, G., and Cherukuri, S. (2013). Domestic violence in India: insights from the 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey. J. Interpers. Violence 28, 773–807. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455867

Kirkwood, C. (1993). Leaving abusive partners: From the scars of survival to the wisdom for change : Duke University Press.

Kishor, S., and Johnson, K. (2006). Reproductive health and domestic violence: are the poorest women uniquely disadvantaged? Demography 43, 293–307. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0014

Koenig, M. A., Ahmed, S., Hossain, M. B., and Mozumder, A. B. M. K. A. (2003). Women’s status and domestic violence in rural Bangladesh: individual-and community-level effects. Demography 40, 269–288. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0014

Koenig, M. A., Stephenson, R., Ahmed, S., Jejeebhoy, S. J., and Campbell, J. (2006). Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. Am. J. Public Health 96, 132–138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872

Krishnan, S. (2005). Gender, caste, and economic inequalities and marital violence in rural South India. Health Care Women Int. 26, 87–99. doi: 10.1080/07399330490493368

Krishnan, S., Subbiah, K., Khanum, S., Chandra, P. S., and Padian, N. S. (2012). An intergenerational women’s empowerment intervention to mitigate domestic violence: results of a pilot study in Bengaluru, India. Viol. Against Women 18, 346–370. doi: 10.1177/1077801212442628

Leadley, K., Clark, C. L., and Caetano, R. (2000). Couples’ drinking patterns, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related partnership problems. J. Subst. Abus. 11, 253–263. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00025-0

Lim, L. Y. (1997). Capitalism, imperialism and Patriarcy: The dilemma of third-world women Workers in Multinational Factorie in Visvanathan, Naline (etal). Dhaka: The University Press Limited.

Mahapatro, M., Prasad, M. M., and Singh, S. P. (2023). Domestic violence and COVID-19: policy and pattern analysis of reported cases at the family counseling center (FCC) in Alwar, India. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 20, 1096–1104. doi: 10.1007/s13178-022-00782-z

Markowitz, S. (2000). The price of alcohol, wife abuse, and husband abuse. South. Econ. J. 67, 279–303.

Martin, D. (1976). Battered wives (revised Subsequent edition). San Francisco, CA: Glide Publications.

Martin, S. L., Moracco, K. E., Garro, J., Tsui, A. O., Kupper, L. L., Chase, J. L., et al. (2002). Domestic violence across generations: findings from northern India. Int. J. Epidemiol. 31, 560–572. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.560

Mirchandani, R. (2006). Hitting is not manly, domestic violence court and the re-imagination of the patriarchal state. Gend. Soc. 20, 781–804.

National Crime Records Bureau. (2019). Crime in India. Available at: https://ncrb.gov.in/crime-in-india-year-wise.html?year=2019&keyword

Nielson, J., Eberly, P., Thoennes, N., and Walker, L. (1979). Why women stay in battering relationships: preliminary results. Presented at the American Sociological Society Meeting, Boston, Mass.

Pagelow, M. D. (1981). Factors affecting women’s decisions to leave violent relationships. J. Fam. Issues 2, 391–414.

Parrado, E. A., Flippen, C. A., and McQuiston, C. (2005). Migration and relationship power among mexican women. Demography 42, 347–372. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0016

Pence, E., and Paymar, M. (1993). Education groups for men who batter: the Duluth model. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Pertek, S., Block, K., Goodson, L., Hassan, P., Hourani, J., and Phillimore, J. (2023). Gender-based violence, religion and forced displacement: protective and risk factors. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1058822. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1058822

Piedalue, A. (2015). Understanding violence in place: travelling knowledge paradigms and measuring domestic violence in India. Indian J. Gend. Stud. 22, 63–91. doi: 10.1177/0971521514556947

Raj, A., Silverman, J. G., Klugman, J., Saggurti, N., Donta, B., and Shakya, H. B. (2018). Longitudinal analysis of the impact of economic empowerment on risk for intimate partner violence among married women in rural Maharashtra, India. Soc Sci Med 196, 197–203.

Rao, V. (1997). Wife-beating in rural South India: a qualitative and econometric analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 44, 1169–1180. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00252-3

Rapp, D., Zoch, B., Khan, M. M. H., Pollmann, T., and Krämer, A. (2012). Association between gap in spousal education and domestic violence in India and Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 12, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-467

Reilly, N., Sahraoui, N., and McGarry, O. (2021). Exclusion, minimization, inaction: a critical review of Ireland's policy response to gender-based violence as it affects migrant women. Front. Hum. Dyn. 3:642445. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.642445

Rocca, C. H., Rathod, S., Falle, T., Pande, R. P., and Krishnan, S. (2008). Challenging assumptions about women’s empowerment: social and economic resources and domestic violence among young married women in urban South India. Int. J. Epidemiol. 38, 577–585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn226

Samal, S., and Poornesh, S. (2022). Prevalence of domestic violence among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study from a tertiary care Centre, Puducherry, India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 16. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2022/50428.16213

Sanghera, T. (2018). Delaying marriage by a year can empower women against domestic violence. Available at: https://www.indiaspend.com/delaying-marriage-by-a-year-can-empower-women-against-domestic-violence/

Schuler, M. S., Rice, C. E., Evans-Polce, R. J., and Collins, R. L. (2018). Disparities in substance use behaviors and disorders among adult sexual minorities by age, gender, and sexual identity. Drug Alcohol Depend 189, 139–146.

Schneider, D., Harknett, K., and McLanahan, S. (2016). Intimate partner violence in the great recession. Demography 53, 471–505. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0462-1

Sen, S. (2000). Toward a feminist politics?: The Indian Women's movement in historical perspective. Calcutta: World Bank, Development Research Group/Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Network.

Sen, G., George, A., and Östlin, P. (2002). Engendering international health: the challenge of equity. London: MIT Press.

Shirwadkar, S. (2009). Family violence in India: Human rights, issues, actions and international comparisons. Jaipur: Rawat Publishers.

Singh, A., and Singh, A. (2013). Intergenerational transmission of gender based domestic violence in India: some new evidence. In annual conference of the International Union for Scientific Study of population (IUSSP) at Seoul, South Korea.

Singh, A., Singh, A., Pallikadavath, S., and Ram, F. (2014). Gender differentials in inequality of educational opportunities: new evidence from an Indian youth study. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 26, 707–724. doi: 10.1057/ejdr.2013.35

Sreelatha, D., Girija, N., Purandaran Vasanthamani, B., Bindhu, A., Jose, R., and Leelavathy, M. (2021). Prevalence of domestic violence among married women doing unskilled manual work in a rural area of Trivandrum district. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health 8:1350. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20210809

Straus, M. A., and Gelles, R. J. (1989). Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families, (revised edition). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Straus, M. A., and Hotaling, G. T. (1980). The social causes of husband-wife violence. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sugarman, D. B., and Hotaling, G. T. (1989). Violent men in intimate relationships: an analysis of risk markers 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 19, 1034–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb01237.x

Sultana, A. (2010). Patriarchy and women s subordination: a theoretical analysis. Arts Facul. J., 1–18. doi: 10.3329/afj.v4i0.12929

Tur-Prats, A. (2021). Unemployment and intimate partner violence: a cultural approach. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 185, 27–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.02.006

Veloso, D. T. M. (2022). Safety and security issues, gender-based violence and militarization in the time of armed conflict: the experiences of internally displaced people from Marawi City. Front. Hum. Dyn. 3:703193. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.703193

Visaria, L. (2008). Violence against women in India: is empowerment a protective factor? Econ. Polit. Wkly. 43, 60–66.

WHO. (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C5E36FFB241D5D597BA47F2806B1A24A?sequence=1

WHO (2013). “Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence” in Department of Reproductive Health and Research, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, south African medical research council (Geneva: World Health Organisation). Available at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/

WHO. (2018). WHO | global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Available at: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/ (Accessed 25 September 2023)

WHO (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Keywords: domestic violence, intergenerational educational mobility, education, women, India

Citation: Choudhary A and Singh A (2024) Breaking chains across generations: exploring the nexus between intergenerational educational mobility and domestic violence among Indian women. Front. Hum. Dyn. 6:1390983. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2024.1390983

Edited by:

Akansha Singh, Durham University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jasmin Lilian Diab, Lebanese American University, LebanonPriyanka Tripathi, Indian Institute of Technology Patna, India

Copyright © 2024 Choudhary and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Akanksha Choudhary, Y2hvdWRoYXJ5ai5ha2Fua3NoYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Akanksha Choudhary

Akanksha Choudhary Ashish Singh2

Ashish Singh2