- 1Department of Environment, Development, and Health, School of International Service, American University, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Collegium de Lyon, Université de Lyon, Lyon, France

- 3Center on Health, Risk and Society, College of Arts and Sciences, American University, Washington, DC, United States

- 4Psychologie de la Santé, Université Lumière Lyon 2, Lyon, France

- 5Santé Publique, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, France

- 6Pôle Recherche et Innovation, Habitat et Humanisme, Caluire et Cuire, France

- 7LEIRIS, Université Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, Montpellier, France

The concept of “transit” is an understudied phenomenon in migration studies. Transit is not necessarily a linear and unidirectional temporal movement from origin to destination countries, nor is it a clearly demarcated event in time and space. This article examines the complex dimensions of transit, that is, the geospatial, social, economic, psychological, and relational aspects that both shape and are being shaped by asylum seekers. Drawing on a unique qualitative phenomenological approach, the study utilizes an in-depth case narrative to trace and analyze the transit of Mamadou, a Guinean 26-year-old male asylum seeker in France. The salient themes of the narrative fall into five parts: (1) Triggers of transit; (2) Transit as a survival strategy; (3) The complex legal hurdles of asylum; (4) The politics of discomfort and dispersal; and (5) Acts of resistance. Throughout the narrative, an analytic lens is interwoven as informed by relevant literature. The results highlight how Mamadou's migration trajectory is characterized by various cycles of trauma, while he simultaneously employs survival, livelihood, and resistance strategies to confront and overcome these different forms of trauma. This paper highlights the much-needed call to depoliticize transit through adopting a pragmatic approach to asylum that promotes a virtuous cycle of policies, which contribute to the wellbeing and integration of asylum seekers.

Introduction

While migration is commonly thought of as crossing borders between nations, the scope of international migration is smaller than conceptualized, as only about 3.5% of the global population lived in a different country than where they were born in 2020 (McAuliffe and Triandafyllidou, 2021). An asylum seeker is recognized as “a person who has left their country and is seeking protection from persecution and serious human rights violations in another country, but who hasn't yet been legally recognized as a refugee and is waiting to receive a decision on their asylum claim” (Amnesty International, 2024).

Conflict in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, the Republic of Guinea and other countries have contributed to a growing number of individuals who are seeking asylum in European countries (Buonfino, 2004; United Nations, 2016; Krzyżanowski et al., 2018; Sajjad, 2018; Grande et al., 2019; Castelli Gattinara and Zamponi, 2020; Lauwers et al., 2021; UNHCR, 2021; Castañeda, 2022). This influx of asylum seekers has been continually framed as a “refugee crisis,” which inherently problematizes those seeking refuge (Buonfino, 2004; Grande et al., 2019; Castelli Gattinara and Zamponi, 2020; Castañeda, 2022). While refugees arrive in their new host country with pre-approved protection status or receive this status when granted asylum in the country, asylum seekers live in a state of liminality for an indefinite and usually prolonged period as they await the outcome of their asylum case (Constant and Zimmermann, 2016; Havrylchyk and Ukrayinchuk, 2017). They lack legal and social security within their new host country (Constant and Zimmermann, 2016). In France, 149,511 asylum applications were registered on December 31, 2023, 6.4% more than at the end of the previous year (Forum Réfugiés, 2024). The top five countries of origin in 2023 with the most asylum seekers in France were: Afghanistan, Guinea, Turkey, Ivory Coast, and Bangladesh (Forum Réfugiés, 2024).

The concept of “transit” in migration studies is garnering increasing attention with much of the focus on how transit is embedded in the overall migration trajectories of individuals from the Global South who are in limbo in the Global North, or experiencing violent border regimes and/or immobility at the borders (Mountz et al., 2002; Agier, 2011; De Leon and Wells, 2015; Crawley et al., 2018; Walia, 2021; Laakkonen, 2022; Riva, 2022). However, migration trajectories are not necessarily linear and unidirectional temporal movements from origin to destination countries, nor are they clearly demarcated events in time and space (Castagnone, 2011; Crawley and Jones, 2021). To date, there is no clear and consistent definition of the concept of “transit” in the extant migration literature. In its earliest conceptualization, Düvell (2012) referred to it as “blurred, politicized concept that is closely related to processes identified with the internationalization or externalization of European Union migration policies.”

More recently, critical migration scholars have begun to unpack the complexity of transit as part of the “complex mobility puzzle” that can vary in duration and be reiterated events, occur at any stage of the migration trajectory, and transpire within Africa as well as within Europe (Castagnone, 2011; Fontanari, 2018; Snel et al., 2021). The idea that asylum seekers in transit are simply moving “in-between” countries ignores the fact that asylum seekers often stay in various spaces within a country for indefinite periods of time and cultivate livelihoods in these spaces. In this sense, being in “transit” may, therefore, include various spaces in one or more countries (i.e., multispatial), in various directions (i.e., multidirectional), and for varying periods of time (i.e., multitemporal) before deciding or being forced to move on. Those seeking asylum often find themselves “caught in… (im)mobility” (Fontanari, 2018, p. 172). Migration scholars have highlighted how asylum seekers' experience of “transit” is internalized by experiences of moving (Khosravi, 2010), waiting (Bissell, 2007), being stuck (Brekke and Brochmann, 2015), crossing borders (Coutin, 2005), or “fragmented circuits,” which “occur both in time and space” (Fontanari, 2018, p. 76).

The precarious, unpredictable, and open-ended nature of transit significantly affects the migration trajectories of asylum seekers. We, therefore, define transit as a series of actions and experiences with indefinite beginnings and ends that are shaped by the subjectivities and social relationships of each asylum seeker as well as the structural factors that impede or control their mobility. These structural factors include the national migrant laws and local reception management policies and practices that influence the asylum seekers' experiences in a particular space. Moreover, the temporary nature of transit impedes asylum seekers from participating in long-term planning or pursuing future projects (Fontanari, 2018). The experiences of asylum seekers, in turn, allows us to conceptualize transit as related to both “transition(s)” (e.g., between legal categories, such as asylum seeker to refugee; between expectations and reality; or between various relationships), and “transiting” (e.g., between countries, places). Our study draws on a qualitative phenomenological approach to trace and analyze in-depth the transit experiences of a Guinean 26-year-old male asylum seeker in France.

Methods

Design

The study utilized a qualitative phenomenological methodology grounded in an idiographic approach to research, which explores how an asylum seeker experienced transit. This methodology concerns itself with the specific and unique richness of the transit phenomenon as understood by the asylum seeker. The aim of phenomenology is to explore and capture the meaning of the phenomenon through analysis of the participant's “lived experience” (Moustakas, 1994). The term “lived experience” refers to a participant's narrative account or the story of their experience, told in their own words (Moustakas, 1994). Fundamentally, phenomenology seeks to understand the essence of the individual's experience.

Data collection

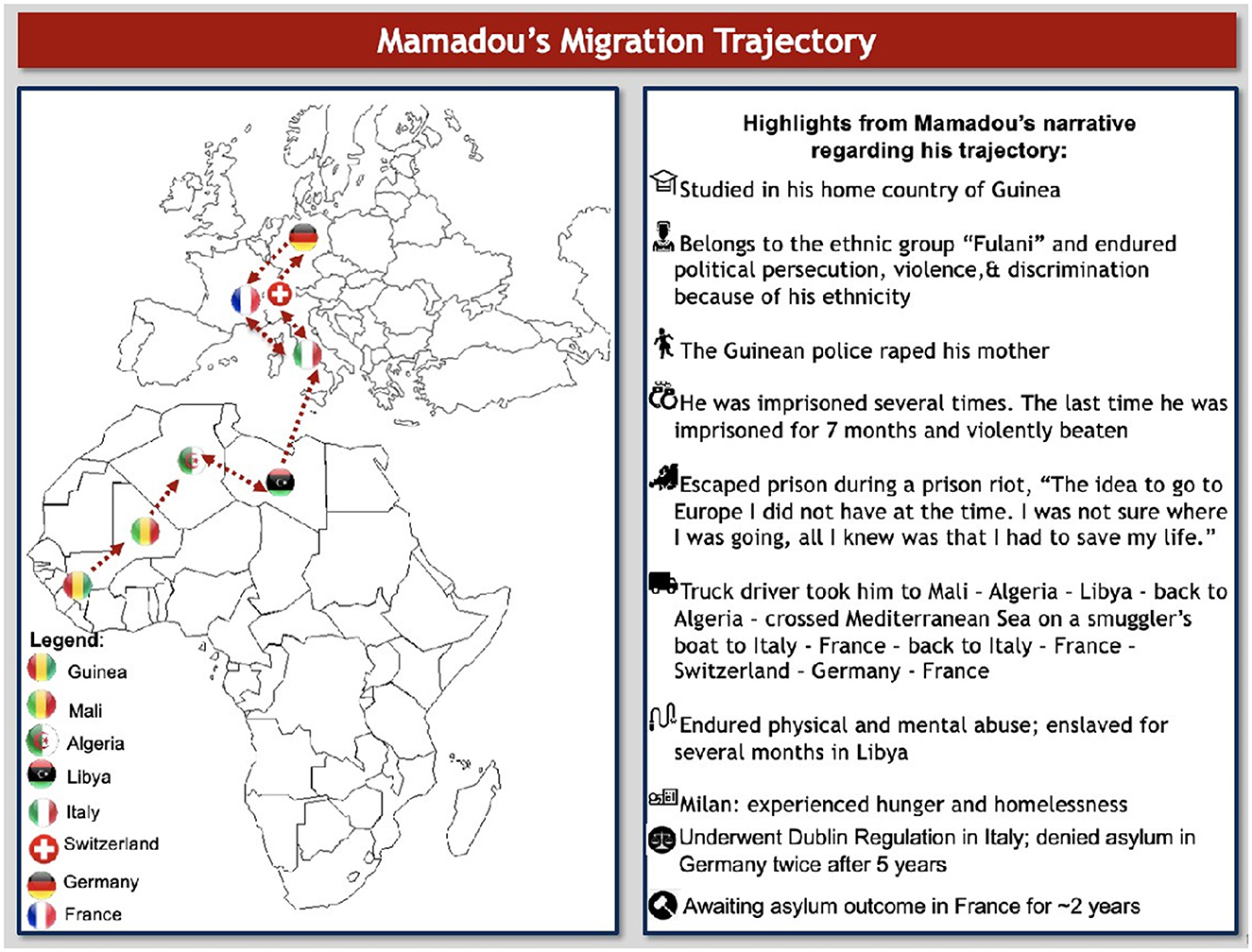

The study utilized an in-depth case narrative to trace and analyze the transit experiences of a Guinean 26-year-old male asylum seeker named Mamadou (pseudonym) in France. In line with Collins (2017) research, migrant narratives “allow researchers and migrants themselves to piece together accounts of movement that cut across geographic and temporal settings.” The first author conducted six interviews in French with Mamadou between September 2019 and February 2020 in a private room at a local library in Lyon. The chosen language for the interviews was French given that the participant was fluent in the language and comfortable sharing his experiences in that language. Each interview was audio recorded and lasted ~2 h. A collaborative partnership with Habitat et Humanisme, a community-based organization that serves vulnerable community members, including asylum seekers and refugees, facilitated trust and relationality with participants as well as the participant recruitment process. The first two semi-structured interviews were dedicated to Mamadou's narrative of the pre-migration experience, followed by two interviews relating to his fleeing experience, and the latter two interviews focusing on his post-migration experiences. This process enabled a rich and in-depth understanding of this asylum seeker's transit experiences.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Université de Lyon. The participant was offered a comprehensive description of the study, including its purpose and the data collection process. The first author also explained to the interviewee that participation was voluntary, and that the participant could withdraw from the study at any time without repercussions to the receipt of current or future services. Written consent was obtained prior to the interviews. Protection of confidentiality was assured through the deidentification process and secure storage of all information.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis were iterative processes. The first author first transcribed the interviews and then translated the French transcripts to English. A professional bilingual translator checked the transcripts for accuracy by performing a thorough line-by-line quality check on all the transcripts as she listened to each interview audio recording and edited any translation errors. The English transcripts were then analyzed utilizing narrative analysis (Riessman, 1993). We began by creating initial codes as we read each transcript and then collapsed these initial codes into higher order codes that reflected emergent themes. We had multiple data analytic group sessions that allowed us to refine the themes. The participant constructed his narrative of transit from his own personal experience, and subsequently, we interpreted the construction of that narrative. We selected this approach as it allowed us to unpack the complex themes related transit that were salient in the participant's lived experience.

Results

Mamadou's transit experience is analyzed as a four-part narrative: (1) Triggers of transit; (2) Transit as a survival strategy; (3) The complex legal hurdles of asylum; (4) The politics of discomfort and dispersal; and (5) Acts of resistance. Throughout the narrative we interweave an analytic lens informed by relevant literature from migration studies.

Part 1: Triggers of transit

Mamadou was born and raised in the Republic of Guinea, a coastal country in West Africa. Guinea is bordered by Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Liberia and Sierra Leone to the south. Guinea, under the name French Guinea, was a part of French West Africa until it gained independence in 1958. Mamadou lived with his mother and siblings and his father. He is from a large ethnic group known as the Fulani or Fulbe (Peul in French), who speak different local languages and have different cultural practices than the other ethnic groups in the country, namely the Malinké and the Soussou.

The complex triggers of transit

During civil protests between October 2019 and July 2020, the Guinean government persecuted the Fulani ethnic group, including killing and arresting young people for being a part of the protests. Mamadou stated that even though he did not choose to be Fulani, they still discriminated against and harassed him. He believed that the West (namely, France and the United States) recognize the atrocities committed by the Guinean president, yet they knowingly support him despite these offenses. He recounted how he and his family had endured many traumatic and violent experiences at the hands of those in power in Guinea due to their Fulani membership. In Mamadou's home neighborhood, there were 130 Fulani youth who were killed, including his brother who had lost his life by a flying bullet. Many women that Mamadou knew, including his mother and sisters, had been victims of sexual violence and rape.

At the peak of the tension, four police officers arrived at Mamadou's home and wrongfully accused him and his mother of crimes they did not commit. His mother attempted to defend Mamadou, and as a result, she was raped in front of her family members. Following this event, the police arrested Mamadou and transported him to the worst prison in the country where he was imprisoned for seven months. Even within the prison, an ethnic divide existed, and as such, Mamadou was violently beaten during his imprisonment.

In addition to this violence, Mamadou recounted the inhumane prison conditions, stating that his prison cell “was unfit for a dog, with little lighting and no toilet or sink.” Mamadou recalled that he slowly became “a skeleton.” One day, during a prison riot, Mamadou was able to escape from the prison. He stated, “The idea to go to Europe I did not have at the time. I was not sure where I was going, all I knew was that I had to save my life.” Snel et al. (2021) describe a Eurocentric bias in migration literature highlighting that it often denies the reality that some migrants never intend to move to Europe. In this case, Mamadou was unclear about his destination, he was simply fleeing to survive.

Cycles of trauma

In Mamadou's narrative, we observe that the decision to migrate was not a pre-planned and exclusively voluntary one, but rather a desperate move to seek safety and protection. Refugees and asylum seekers are often forced to flee their home countries due to violence, war, lack of basic needs including food security and healthcare access, as well as ever-changing environmental challenges, persecution, and overall danger to wellbeing and ability to flourish (Toma and Castagnone, 2015; Silove et al., 2017; Hynie, 2018; Cantekin, 2019; Lusk et al., 2021; Willen et al., 2021). In his recollection of his escape from prison, Mamadou said, “Many people misjudge the motivation of asylum seekers and think we are here [in France] primarily due to poverty. Many of us here are not fleeing misery. We can manage misery. Even in France, there is misery and poverty, but what we are fleeing is the violence.”

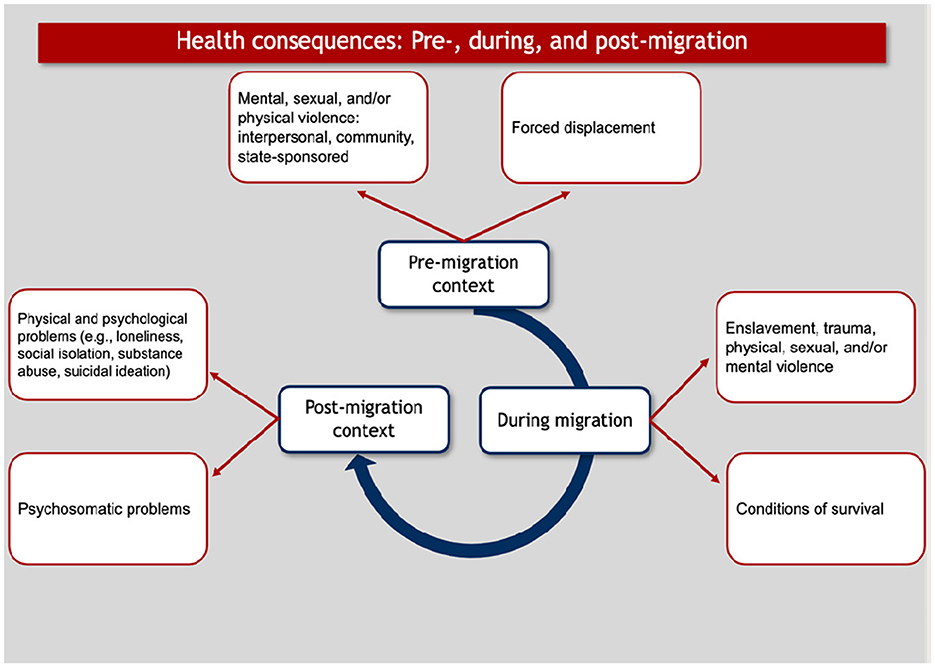

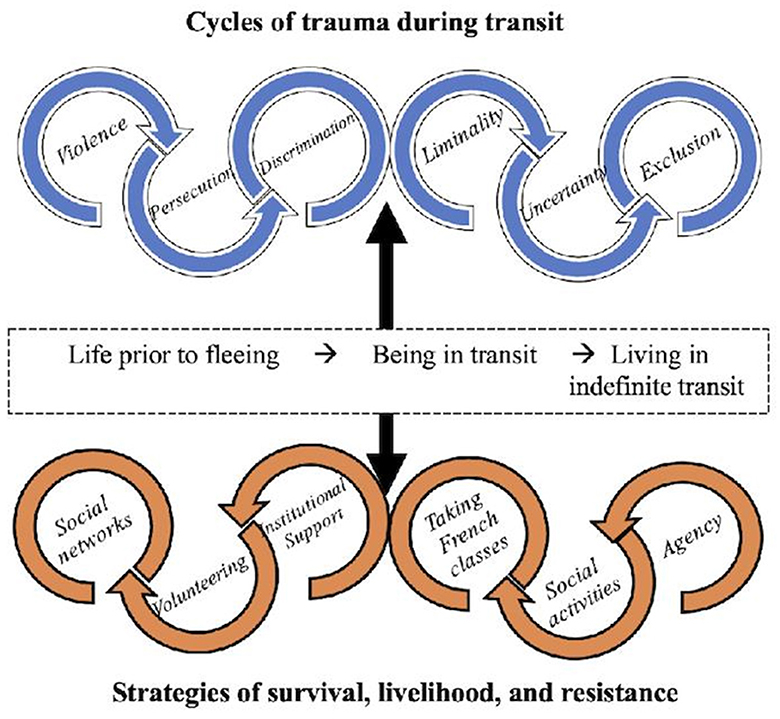

The complex pre-migration circumstances as well as the transit experiences of migrants once they leave their country of origin can result in psychological distress and post-traumatic stress, which impact their ability to function and flourish in their new environments (Ryan et al., 2008; Lien et al., 2010; Bakker et al., 2014; Constant and Zimmermann, 2016; Crawley and Skleparis, 2018; Sajjad, 2018; Cantekin, 2019; Stuart and Nowosad, 2020). The different forms of trauma that asylum seekers continue to undergo in transit are also crucial to recognize beyond and separate from previously endured traumas throughout the other phrases of their migration trajectory (Hynie, 2018). Transit is, therefore, characterized by various cycles of trauma—pre-, during, and post-migration—that negatively harm the mental health and wellbeing of asylum seekers, and these impacts can vary in terms of their severity (Figure 1) (Bogic et al., 2012; Hynie, 2018; Stuart and Nowosad, 2020).

Part 2: Transit as a survival strategy

As Mamadou described, transit was a “survival strategy” triggered by the violence and persecution that he endured in his country. From Guinea, a truck driver took Mamadou to the neighboring country of Mali and then to the North African country of Algeria. Upon his arrival in Algeria, Mamadou discovered that the Algerian government was sending Fulani Guineans back to Guinea. He ended up meeting a Guinean man who he worked for a few weeks who then gave him a ride to Libya. He described Libya as having “no government and no stability.” There he was enslaved for about 2 months where he was forced to work and received no financial compensation. He recounted his transit experience in Libya: “There were many people in this place. We all had to work. We were given small meals at the end of the day. We all slept there too on the ground on top of makeshift beds. I was cold at night. I barely slept.” He also described how he had endured extreme physical and mental torture while in Libya. His capturers told him that if he wanted to leave Libya, he would have to have his family send money. He was able to get in contact with Guinean family members who were able to send some money. As such, Mamadou paid a Libyan man to take him back to Algeria.

Mamadou's narrative revealed that his transit in the continent of Africa was not completely linear nor unidirectional from point A to point B as his return to Algeria after his time in Libya displayed a pattern of circular movement (Fontanari, 2018; Snel et al., 2021). Mamadou experienced multiple “transits” to various countries with no clear destination in mind, as he was influenced by the set of adverse circumstances in which he found himself. In other words, he did not predetermine these destinations, but found himself caught in transit as a means to survive. As he discovered the conditions in these countries and endured more trauma—for instance, strict internal migration controls that prevented him from staying in Algeria to a context of degradation and exploitation in Libya—transit became a “survival strategy” he continued to employ as he sought safety and protection for his life.

Survival or death

Mamadou's transit was also influenced by the people who he met along his path. While in Algeria the second time, he learned about people who smuggled people to Europe and obtained information on how to cross the Mediterranean Sea. He paid a few smugglers a deposit and agreed to pay them the remainder when he was in Europe. He recalled his transit to Europe on an inflatable boat with about 100 people in it, all of whom were as desperate as he was to seek protection and safety. He recounted, “I remember there was a woman with a baby and there were so many people on the boat. Some people were getting crushed. Not everyone was able to survive these conditions. I saw death around me.” He ended up making it to Italy where he stayed at a migrant camp for about 3 months.

Mamadou's migration trajectory was marked by trauma, negative psychological and physical health outcomes, and stress (Renner et al., 2020; Figure 1). He had already endured trauma prior to migration and during his transit endured new cycles of trauma. Mamadou related his experience, “I fled my country leaving behind a bunch of problems only to encounter a new set of problems and no protection, which forced me to keep moving.” While asylum seekers, like Mamadou, are exposed to violence prior to their journeys, they continue to undergo trauma at each stage of their relocation (Lusk et al., 2021; Figure 1). According to the European Union (EU), as of 2022 nearly 330,000 asylum-seekers have crossed into Europe through perilous border crossing means (Frontex, 2023). Nearly 15,000 of these crossings occurred in the Western Mediterranean (Frontex, 2023) and represent the hazardous and traumatic nature of transit that many asylum seekers experience, resulting in an estimated 29,000 deaths in the Mediterranean since 2014.

The non-linear transit in Europe

Mamadou's narrative revealed the nature of transit within North Africa and to Europe as dangerous and unpredictable. Subsequently, even when he arrived in Europe, his transit was difficult and non-linear. Mamadou was first brought to a migrant camp in Italy. From the camp, Mamadou went to the city of Milan in northern Italy where he experienced hunger and homelessness. No one was willing to help him. While in Milan, other Africans explained to him how to get to France. He ended up meeting an Italian man who spoke a little French who smuggled people to the border town of Nice on the southeastern coast of France. In Nice, he was stopped by the police and was brought back to Italy, therefore again displaying the circular nature of transit. While in Italy, Mamadou met a group of African and Albanese asylum seekers who were headed to Switzerland. He decided to follow suit. He met a man who spoke French who was willing to drive him across the border to Switzerland with another Fulani asylum seeker who paid for his ride. In Switzerland, he was again detained by police and returned once again to Italy, which again exemplifies how structural migration controls affect the transit of asylum seekers. He then stayed in Italy for about a month, and then traveled back to Switzerland again. A week later, he crossed the border into Germany alone, a decision that was influenced by the local residents telling him that life was too complicated for asylum seekers in Switzerland. He ended up spending 5 years in Germany.

Mamadou's transit to multiple locations in Europe varied in duration and was characterized by a few reiterated events (e.g., went to Italy, France, and Switzerland twice). His narrative displayed how individualized circumstances evolve for different asylum seekers, including the external forces that cause individuals to move and impact their decisions about where to relocate (Arriola Vega, 2021; Snel et al., 2021). Transit for Mamadou was an ever-changing process that involved “multiple paths, gateways, entry and exit points, and territories en route to the country of resettlement” (Yildiz and Sert, 2021; Figure 2). Fontanari (2018) refers to this transit as a sort of “temporal prison” of uncertainty related to asylum seekers' legal condition that keeps them on the move without a clear direction.

Part 3: The complex legal hurdles of asylum

In addition to experiencing temporary living accommodations, asylum seekers have a precarious legal status. Mamadou was first fingerprinted in Italy, and it took almost a year for him to learn that he had been denied asylum in Italy. Following his non-linear transit throughout Europe (Figure 2), Mamadou settled in Germany to seek asylum, as he perceived this EU-state as more likely to grant him legal status than other neighboring countries. Various countries throughout the EU are characterized by different acceptance rates, and Germany at the time was known to have a high acceptance rate of asylum seekers (Bordignon and Moriconi, 2017).

When an asylum seeker is unlikely to be granted asylum within the Dublin Regulation, this enables “incentives for moving on within Europe” (Toma and Castagnone, 2015). In the case of Mamadou, like other asylum seekers who are first rejected from the EU-state where they first entered, he actively navigated his surroundings with the aim of achieving protection and security within the complex dynamics of migration policies (Crawley and Hagen-Zanker, 2019; Bartel et al., 2020; Kuschminder, 2021).

He was also denied asylum in Germany, and thus, appealed the decision. However, he was rejected a second time. Despite the 5 years that he had spent in the country, Mamadou's life was uprooted again. He recounted, “I felt I wasted 5 years of my life. In Germany, I played soccer. I went to school for job training. I learned the language. I had friends. I had a life. Now I feel like a nobody starting from zero.” As Mamadou was forced to leave, he made his transit back to France again, thus displaying how the current legal policies contributed to circular migration (Figure 2). The policies led some asylum seekers to move on to other countries in search of security, while others were transferred back to their first destination, thus creating forced circular transit. The prolonged asylum process throughout the EU, as influenced by the Dublin procedure, has created a never-ending system of limbo for asylum seekers across the region (Fassin, 2005).

Mamadou's reflection of feeling defeated also revealed the new cycle of trauma of having to be on the move again and experiencing uncertainty and exclusion. He stated, “I have no asylum and no papers to be here permanently. Without papers, I have no identity. Having these legal papers would allow me to be safe, to work and have more rights, maybe I could then form a family in the future. I could somehow have a normal life.” He continued by explaining that he wanted to work, “I do not want the government to give me money. I want to go to work! I want to do something here. I feel I spend a lot of time doing nothing. Taking French classes twice a week is not enough. I am waiting, that is all I do.” This time in France, Mamadou was trapped in a space of legal and socio-economic limbo again despite the European Union's efforts to harmonize asylum policies across member-states.

Due to uneven distribution of those seeking asylum across the EU, the European Council created the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) in 1999, based on the principles outlined in the Geneva Convention. As a result, the CEAS was developed to harmonize asylum policies across the EU (European Commission, n.d.). One of its legislative instruments is known as the Dublin Regulation, which establishes the EU-state responsible for examining asylum application. In sum, the EU-state which first finger-printed an asylum seeker, that is the country of entry, is responsible for accepting or rejecting the asylum seeker, thereby preventing transfer of asylum seekers from one country within the EU to another (Constant and Zimmermann, 2016). In practice, however, the Dublin Regulation has contributed to a lack of responsibility region-wide for asylum seekers and has significantly increased waiting periods for asylum seekers (Bartel et al., 2020), as we observed in the case of Mamadou.

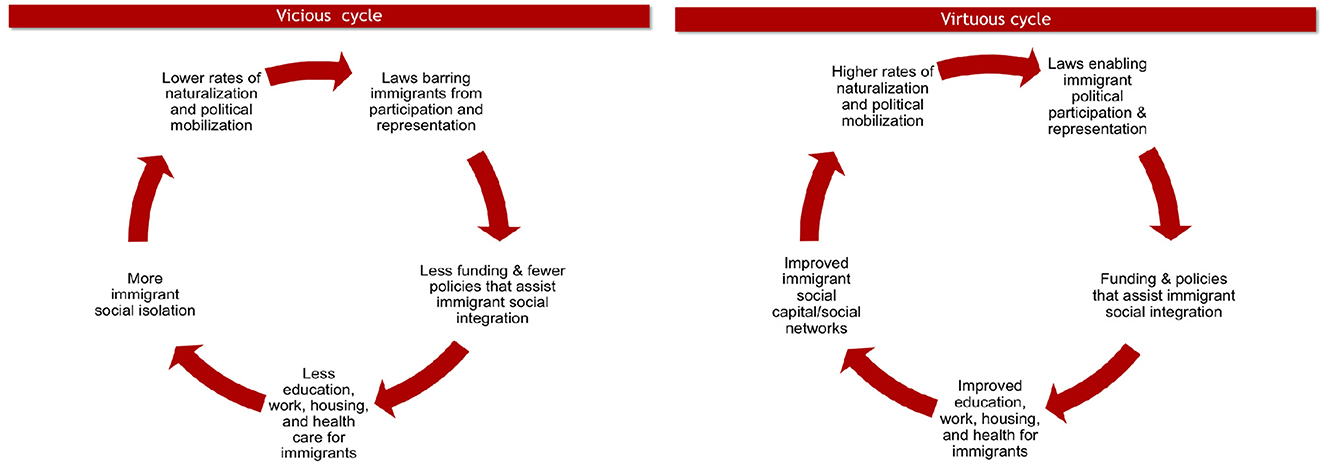

The negative impact of current migration policies is reflected in Mamadou's forced transit. As he states, “These [migration] policies have not yet changed. We continue to suffer here in France even though France calls itself a “country of human rights.” There is a humanitarian crisis.” Current migration policies in the EU represent a vicious cycle, which bars asylum seekers from social and economic integration and increased social isolation, and in turn, harms the health and wellbeing of asylum seekers (Sales, 2002; Phillimore and Goodson, 2006; Havrylchyk and Ukrayinchuk, 2017). Mamadou further stated, “What I need most is for people to understand my situation, for the government to understand my situation and to create policies that help asylum seekers instead of hurting us.” Figure 3 depicts a vicious cycle of migration policies and their impact on the lives of asylum seekers who are living in transit with no clear path forward vs. a virtuous cycle of migration policies that facilitate asylum seekers' social integration and improve their health and wellbeing.

Part 4: The politics of discomfort and dispersal

During his first arrival in Italy while at the migrant camp, Mamadou described how there was frequently a lack of water as well as food in the camp for all the asylum seekers. He recounted, “There were days when I did not even have water to drink. They had run out of clean water and the local restaurants and residents outside the camp refused to give me water. There was also not enough food for us. I went hungry for many days.” Kreichauf (2018) coined the term “campization” to describe the increasingly normalized use of temporary living situations across the EU. These camps “[function] to territorialize, marginalize, contain, and deter” and work to mark the asylum seeker's position in society, which is in line with the alienation of those seeking asylum (Kreichauf, 2018). Applied to Mamadou's situation in the Italian camp, he was forced into a state and space of discomfort to undermine, negate, and challenge a sense of belonging.

Inhumane living conditions and continual temporality

These inhumane living conditions are representative of internal deterrence policies referred to by critical migration scholars as the “politics of discomfort” meant to marginalize asylum seekers, remind them of their uncertain status, and deter future asylum seekers from following in their footsteps (Guiraudon, 2018; FitzGerald, 2020; Glorius and Doomernik, 2020; Zill et al., 2021; Papatzani et al., 2022). These policies aim to exclude asylum seekers from the economic, political, social, and/or legal rights granted only to French citizens (Boswell, 2003; Darling, 2011; Zill et al., 2021).

As part of the larger scheme of “the politics of discomfort,” these camps are designed in accordance with racially charged discourses and laws throughout Europe (Kreichauf, 2018; Zill et al., 2021). Mamadou described how he had experienced discrimination and racism at the migrant camp in Italy. It was clear to him and other migrants, he recounted, how local Italian residents did not want asylum seekers settling in the camp close to their residential area.

After 5 years in Germany in social and legal limbo, Mamadou moved on to France where he faced a new set of challenges. He was homeless for 2 months in Paris where he slept in a tent under bridges and in parks. He was eventually able to gain assistance from a non-profit organization, which helped him in his transit to Lyon. For about a year, Mamadou and other asylum seekers lived in shipping containers that were transformed into temporary housing accommodations for asylum seekers and were not meant for permanent residence (Figure 4). The structural foundation of the shipping container was faulty due to poor craftsmanship, and caused consistent water leakage from the roof, which prevented Mamadou from sleeping well at night. A fellow asylum seeker who lived with him also had a persistent cough caused by these poor living conditions. As such, once again his living conditions revealed the “politics of discomfort” that many asylum seekers encounter in transit (Boswell, 2003; Guiraudon, 2018; FitzGerald, 2020; Glorius and Doomernik, 2020; Zill et al., 2021).

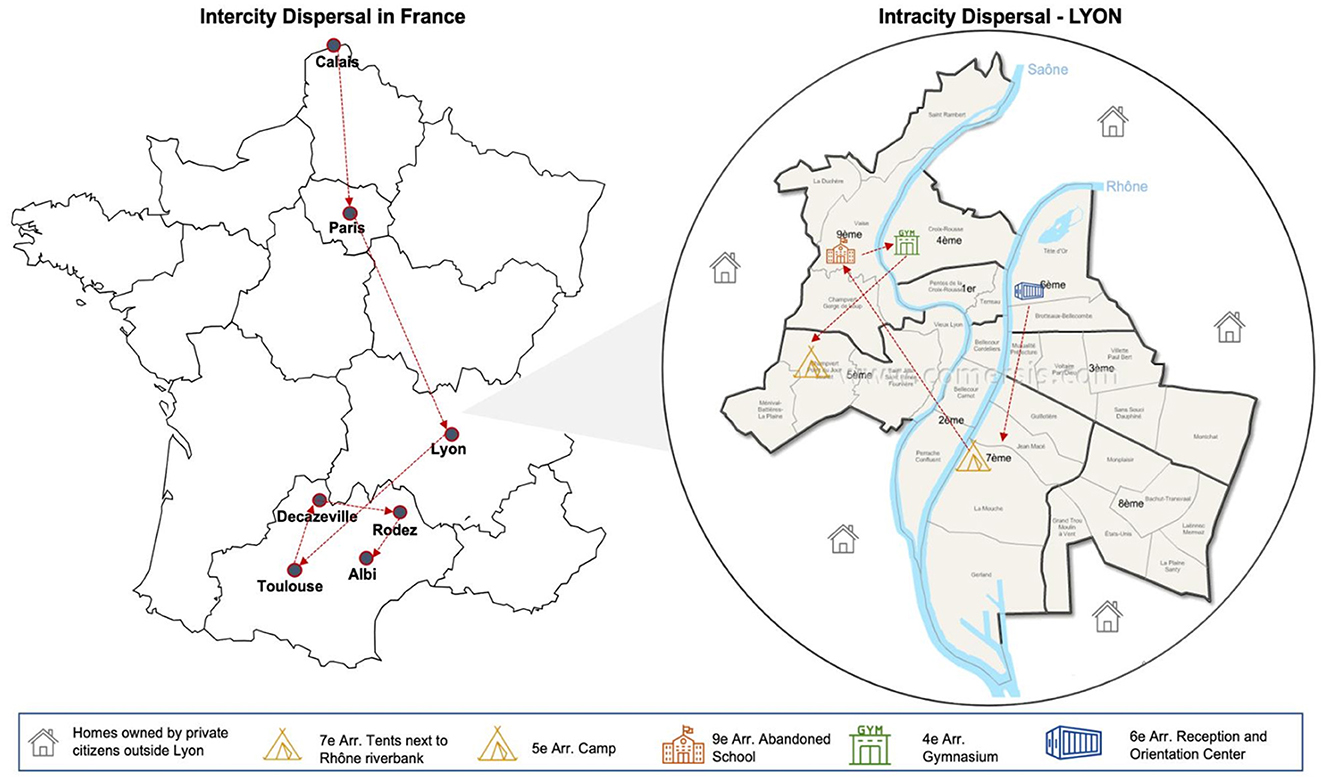

Mamadou was forced to “restart the integration process” living in various transit sites in France (Brekke and Brochmann, 2015; Havrylchyk and Ukrayinchuk, 2017). As defined by Fontanari (2018), these “transit sites” serve as temporary living spaces for recently arrived asylum seekers where people in transit are housed with those of similar temporal and precarious trajectories. Being forced to move to different cities in France and to several sites within these urban areas are elements of what critical migrant scholars have referred to as the “politics of dispersal” (Tazzioli, 2017). Mamadou experienced several transits to different cities in France (i.e., intercity dispersal), and various transit spaces within cities for different periods of time (i.e., intracity dispersal), including Lyon, where he was currently living (Figure 5).

Discrimination and deteriorating mental health

Beyond his lack of employment and housing challenges, Mamadou faced continual discrimination like his experiences in the Italian camp. He woke up one morning and discovered with other asylum seekers a sign with a xenophobic message that “asylum seekers are not wanted here” that had been plastered on the wall surrounding the containers. Mamadou stated, “People want us to leave, and we are blamed for all the bad things that happen in the neighborhood even if it is not us. We are even blamed for the dog poop on the sidewalk, and we do not even own a dog!”

Mamadou also felt marginalized from mainstream French society, stating that he had little opportunity to connect with French natives other than the staff and a few volunteers at the temporary housing shelter where he lived. He recounted, “No one approaches me. They [French people outside the migrant center] do not see me. They do not know me.” Mamadou described how his mental health steadily decreased following his transit back to France. He felt that he lacked a sense of purpose in his new environment, which caused him to feel depressed. In addition to depressive symptoms, Mamadou related how there were times when he felt overwhelmed and anxious. He stated, “There are moments when I feel I can't keep going. What is the point of starting all over again? What if the same thing happens and then I cannot stay here in France? Then what? It is harder to work toward future goals as I wait.”

A myriad of studies has examined the devastating psychological effects of transit for asylum seekers (Sourander, 2003; Ryan et al., 2009; Hynie, 2018; De Jesus and Hernandes, 2019). For example, depression and anxiety rates among asylum seekers have been found to be as high as 69 and 70%, respectively (Sourander, 2003; Ryan et al., 2009). Despite his declining mental health, Mamadou mentioned that he would not give up. His main priority was to feel safe and at peace. He explained that he needed protection and could not return to Guinea, although he understood that there was no guarantee to obtain asylum. He stated, “Certain people who have a right to protection are rejected. This bothers me given what is happening in my country Guinea.”

Part 5: Acts of resistance

While navigating the difficulties of transit, asylum seekers also employed various resistance and livelihood strategies to confront the hurdles they faced (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Asylum seekers endure cycles of trauma during transit and employ strategies of survival, livelihood, and resistance.

For example, Mamadou relied on informal local social networks such as his relationships with other asylum seekers as well as formal social networks such as staff at the camp for emotional, social, and tangible support. He also obtained moral support from his transnational networks by maintaining connections via WhatsApp with his family members in his country of origin. These social networks were representative of the forms of social capital that asylum seekers rely upon as acts of resistance to survive and live amid the challenges of being in transit. While many asylum seekers in transit have been depicted as “agency-less” actors, Mamadou's lived experience displayed the opposite, that is, he showed a strong sense of agency and employed strategies to survive and resist the structural constraints he encountered living in transit.

For instance, during this lengthy period of waiting in Germany (which ended up being close to 5 years), he developed his social network of friends who were asylum seekers from various countries as well as Germans of the same age group. These positive experiences were juxtaposed by the larger society's rejection of his belonging as an asylum seeker without legal status. Mamadou sought to integrate in his own way through forming connections with others around him. The choices that he makes living in transit are also reflective of his agency, which transpires as an act of resistance against the legal and social barriers that he encounters.

The process of seeking asylum, therefore, is not simply a result of passive decision-making but dynamic processes, which are shaped by a complex interaction between macro-, meso- and micro-level factors (Crawley and Hagen-Zanker, 2019). These factors include historical and geographical ties between the origin and host country as well as the economic, political, and social resources that asylum seekers can mobilize to their advantage in pursuit of asylum (Crawley and Hagen-Zanker, 2019). In the face of the legal barriers posed by the Dublin Regulation, Mamadou's expression of active engagement and self-agency in his transit is representative of strategies of resistance.

Although his asylum case had not yet been determined, he now considered France to be his new home and found ways to create a life for himself. He was able to get medication from a psychiatrist for his depression. He volunteered at the local library and was learning French. He was also slowly establishing new informal and formal social networks in France comprised of other asylum seekers and French staff and volunteers at several community-based organizations. He engaged in social activities and played soccer with his new friends. In addition, he stayed in touch with friends he had made while in Germany via social media, and hoped that 1 day in the future, he could travel to Germany to see them again.

Discussion

Our in-depth narrative analysis of Mamadou's transit experiences highlight the importance of conceptualizing transit beyond the geo-spatial linear process in which asylum seekers are depicted as moving from their countries of origin to their countries of destination (Crawley et al., 2018; Crawley and Jones, 2021; Snel et al., 2021). Transit encompasses the temporal, geospatial, sociocultural, economic, psychological, and relational aspects that influence the lives of asylum seekers. As study findings reveal, asylum seekers, like Mamadou, often stay in various spaces within a country for indeterminate periods of time and cultivate livelihoods in these spaces. The uncertain nature of transit deeply affects the migration trajectories of asylum seekers. Oftentimes structural barriers such as the national migrant laws and/or local reception and management policies contribute to the asylum seekers' experiences of transit (Fontanari, 2018).

As the politicization of international migration is driven by assumptions that migrants pose a threat to the national security and political stability of a nation-state, this creates discriminatory narratives and policies toward those seeking asylum (Fassin, 2005; Mulvey, 2010; Darling, 2011; Sajjad, 2018; Castelli Gattinara and Zamponi, 2020). Media discourses are often combined with visceral images and stories of migrants crossing borders, which then play an important role in shaping public opinion toward migration (McCann et al., 2023). These negative public opinions and perceptions regarding migration, in turn, influence the political climate in which policy decisions about the admission and treatment of migrants are made (Banulescu-Bogdan, 2022). As a result of this politicization, macro-level influences including migration policies that bar access to employment, stable housing, and other vital social services negatively affect asylum seekers' health and wellbeing (Mulvey, 2010; Darling, 2011).

Mamadou's narrative highlights how in Europe he experiences new cycles of trauma in transit, while he simultaneously exercises agency through several strategies—survival, livelihood, and resistance. The experiences of asylum seekers demonstrate the dynamic and changing nature of transit. Asylum seekers are “active navigators” who try to find their way in the often complex and dangerous situations they are confronted with Kuschminder (2021). Paradoxically, asylum seekers living in transit find ways to create livelihoods that maintain a sense of dignity in efforts of rationalizing an uncertain future. Their transit is often nonlinear and circular, as personal circumstances change, the context to which they move changes, and structural factors limit or facilitate their opportunities (Arriola Vega, 2021).

This study argues that in efforts of breaking the cycle of the negative impact of current vicious migration policies, the EU must garner the political will to transform their migration system of policies, procedures, and practices to treat asylum seekers with humanity (Brekke and Brochmann, 2015; Henrekson et al., 2020; De Jesus et al., 2023). Numerous countries throughout the EU, including France, are signatories of the United Nations High Commission on Forum Réfugiés (2024) Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol and, as a result, “share the same fundamental values and joint approach to guarantee high standards of protection for refugees” (European Commission, n.d.). The Common European Asylum System has established legal instruments to ensure that asylum seekers “are treated equally in an open and fair system—wherever they apply” (European Commission, n.d.). Despite attempts to establish an ever-increasingly harmonious system across the EU, it has never successfully harmonized its policies in relation to handling asylum affairs (Brekke and Brochmann, 2015; Henrekson et al., 2020). The reality of the lived experiences of those seeking asylum are far from the promises made within the 1951 Refugee Convention and the EU's ambitions to create a harmonized reception system for asylum seekers.

In addition, these policies do not reflect the actual realities on the ground, which prompt asylum seekers to flee in the first place. Asylum seekers are often grouped with economic migrants (Cummings et al., 2015; Léonard and Kaunert, 2019; Kang, 2021). Nevertheless, it is critical to recognize that not all asylum seekers are driven by economic factors, as many, like Mamadou, are driven by a desire to save their lives from the trauma and persecution they endure, which trigger their migration, regardless of economic circumstances (Kang, 2021).

Moreover, distinct conceptual categories that delineate “causes of migration” in the literature are not as clear-cut and practically significant when we analyze the narratives of asylum seekers. In reality, a person may simultaneously fit both categories because violence-torn regions are also devastated economically (Cummings et al., 2015; Léonard and Kaunert, 2019; Kang, 2021). As such, the generalized model inspired by labor migration does not fully describe an asylum seeker's decision-making (Kang, 2021). Moreover, those who move primarily for economic purposes tend to aspire to migrate to a specific location, while those seeking asylum have vague images of the destination, thus displaying the nonlinear and often circular transit patterns in their migration trajectories (Cummings et al., 2015; Kang, 2021). Policymakers continue to fail to recognize the lived experiences of asylum seekers, as stated by Mamadou in his narrative and thus, create policies that further exacerbate the psychological health and wellbeing of asylum seekers (Hynie, 2018).

Living in transit itself is inherently a powerful social determinant which impacts the health and wellbeing of migrants (De Jesus and Hernandes, 2019). Hence, we argue that it is necessary to depoliticize migration to facilitate a more effective process in formulating effective solutions and policies. One way to depoliticize migration is to adopt a pragmatic approach to migration policies, as demonstrated in the case of Portugal. In its policies, Portugal stands out among its European counterparts for working across government to treat migration as an opportunity instead of a problem, and to promote the hospitable reception of migrants of all skill levels (Mazzilli and Lowe, 2023).

Portugal has a history of sensible migration policies and exceptionally positive political narratives around migration. These reflect a long-standing agreement among mainstream parties not to politicize im/migration, based on the mutual understanding that migrants are needed to fill a key role in labor shortages, especially in a context of an aging and shrinking Portuguese population (Mazzilli and Lowe, 2023). Several campaigns have also been developed to foster pro-immigrant narratives, dating back to the “Immigrant Portugal. Tolerant Portugal” campaign in 2005 that followed the first large labor-related immigration wave from Eastern Europe (OECD, 2019). The Portuguese government and the European Commission also created “Strategy Portugal 2030,” as part of the overall national development strategy (Portugal, 2030). Key political figures have also spoken out to debunk negative stereotypes about immigration and promote positive discourse (Visintin et al., 2018). However, more recently, the rise of the far-right party named “Chega” (meaning “Enough”) led by André Ventura is a concern, as anti-migrant rhetoric and discrimination have increased since the party's emergence in 2019.

Alongside this practical rationale, positive political narratives on immigration have also been grounded on value-based arguments, which appeal to a sense of moral obligation (Mazzilli and Lowe, 2023). Community initiatives that aim to help individuals feel solidarity with newcomers and further their own goals—both economic and humanitarian—can also be constructive (Banulescu-Bogdan, 2022). While it may be unrealistic to eradicate all fear and anxiety about migration, it may be possible to defang it to the point that it is not the most salient concern.

Finding practical ways for communities to come together in common purpose can embed feelings of unity over the long term (Banulescu-Bogdan, 2022). For example, local leaders can create structured opportunities for migrants and native populations to have meaningful cultural exchanges through dialogue, food, dance and other traditions (see example of Fundão City in Portugal that integrated Afghan refugees; Barchfield, 2023). Another example is the University of Coimbra, that created a unique channel for refugee students and professionals to integrate into Portuguese society (United Nations Academic Impact, n.d.). These opportunities create foster relationality rather than creating an “us vs. them” categorization.

With an aim to depoliticize migration, we call for a more determined and collective effort to engage with the public and raise their awareness about the facts around migration relying on sound evidence. It is imperative that the media act responsibly in promoting public education and awareness-raising and information campaigns to disseminate accurate information and a fair representation of migrants. The depoliticization of asylum and asylum seekers may offer a fruitful pathway to formulate solutions and policies that aim to improve asylum seekers' social integration and wellbeing, and ultimately, treat them with the human dignity that everyone deserves.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of the Université de Lyon. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BW: Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZM: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LP: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Institute for Advanced Studies, Collegium de Lyon within the Université de Lyon and Habitat et Humanisme.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amnesty International (2024). Who is a Refugee, a Migrant or an Asylum Seeker? Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/refugees-asylum-seekers-and-migrants/ (accessed May 13, 2024).

Arriola Vega, L. A. (2021). Central American asylum seekers in Southern Mexico: fluid (im)mobility in protracted migration trajectories. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 19, 349–363. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2020.1804033

Bakker, L., Dagevos, J., and Engbersen, G. (2014). The importance of resources and security in the socio-economic integration of refugees. A study on the impact of length of stay in asylum accommodation and residence status on socio-economic integration for the four largest refugee groups in the Netherlands. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 15, 431–448. doi: 10.1007/s12134-013-0296-2

Banulescu-Bogdan, N. (2022). From Fear to Solidarity: The Difficulty in Shifting Public Narratives about Refugees. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Barchfield, J. (2023). Afghan Human Rights Advocate helps Portuguese City Embrace Fellow Refugees. UNHCR. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/us/news/stories/afghan-human-rights-advocate-helps-portuguese-city-embrace-fellow-refugees (accessed January 30, 2024).

Bartel, A., Delcroix, C., and Pape, E. (2020). Refugees and the dublin convention. Borders Global. Rev. 1, 40–52. doi: 10.18357/bigr12202019589

Bissell, D. (2007). Animating suspension: waiting for mobilities. Mobilities 2, 277–298. doi: 10.1080/17450100701381581

Bogic, M., Ajdukovic, D., Bremner, S., Franciskovic, T., Galeazzi, G. M., Kucukalic, A., et al. (2012). Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. Br. J. Psychiatry 200, 216–223. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084764

Bordignon, M., and Moriconi, S. (2017). The case for a common European refugee policy. Bruegel Policy Contribution, Brussels, Belgium.

Boswell, C. (2003). Burden-sharing in the European Union: lessons from the German and UK experience. J. Refug. Stud. 16, 316–335. doi: 10.1093/jrs/16.3.316

Brekke, J.-P., and Brochmann, G. (2015). Stuck in transit: secondary migration of asylum seekers in Europe, national differences, and the Dublin regulation. J. Refug. Stud. 28, 145–162. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feu028

Buonfino, A. (2004). Between unity and plurality: the politicization and securitization of the discourse of immigration in Europe. New Polit. Sci. 26, 23–49. doi: 10.1080/0739314042000185111

Cantekin, D. (2019). Syrian refugees living on the edge: policy and practice implications for mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Int. Migr. 57, 200–220. doi: 10.1111/imig.12508

Castagnone, E. (2011). Transit migration: a piece of the complex mobility puzzle. The case of Senegalese migration. Cahiers l'Urmis. 13. doi: 10.4000/urmis.927

Castañeda, E. (2022). Immigrants are only 3.5% of people worldwide – and their negative impact is often exaggerated, in the U.S. and around the world. The Conversation. Available online at: http://theconversation.com/immigrants-are-only-3-5-of-people-worldwide-and-their-negative-impact-is-often-exaggerated-in-the-u-s-and-around-the-world-184522 (accessed March 30, 2024).

Castelli Gattinara, P., and Zamponi, L. (2020). Politicizing support and opposition to migration in France: the EU asylum policy crisis and direct social activism. J. Eur. Integr. 42, 625–641. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2020.1792459

Collins, F. L. (2017). Desire as a theory for migration studies: temporality, assemblage and becoming in the narratives of migrants. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 44, 964–980. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384147

Constant, A. F., and Zimmermann, K. F. (2016). Towards a New European Refugee Policy that Works. Munich: ifo Institut - Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der Universität München 14, 3–8.

Crawley, H., Duvell, F., Jones, K., McMahon, S., and Sigona, N. (2018). Unravelling Europe's “Migration Crisis”: Journeys Over Land and Sea. Bristol: Policy Press. doi: 10.46692/9781447343226

Crawley, H., and Hagen-Zanker, J. (2019). Deciding where to go: policies, people and perceptions shaping destination preferences. Int. Migr. 57, 20–35. doi: 10.1111/imig.12537

Crawley, H., and Jones, K. (2021). Beyond here and there: (re)conceptualising migrant journeys and the ‘in-between.' J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 47, 3226–3242. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804190

Crawley, H., and Skleparis, D. (2018). Refugees, migrants, neither, both: categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe's ‘migration crisis.' J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 44, 48–64. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224

Cummings, C., Pacitto, J., Lauro, D., and Foresti, M. (2015). Why people move: understanding the drivers and trends of migration to Europe. Overseas Development Institute. Available online at: https://odi.org/en/publications/why-people-move-understanding-the-drivers-and-trends-of-migration-to-europe/ (accessed March 29, 2024).

Darling, J. (2011). Domopolitics, governmentality and the regulation of asylum accommodation. Polit. Geogr. 30, 263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.04.011

De Jesus, M., and Hernandes, C. (2019). Generalized violence as a threat to health and well-being: a qualitative study of youth living in urban settings in Central America's “Northern Triangle.” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 34–65. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16183465

De Jesus, M., Warnock, B., Moumni, Z., Sougui, Z. H., and Pourtau, L. (2023). The impact of social capital and social environmental factors on mental health and flourishing: the experiences of asylum-seekers in France. Confl. Health 17:18. doi: 10.1186/s13031-023-00517-w

De Leon, J. D., and Wells, M. (2015). The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Düvell, F. (2012). Transit migration: a blurred and politicised concept. Popul. Space Place 18, 415–427. doi: 10.1002/psp.631

European Commission (n.d.). Common European Asylum System. Available online at: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/migration-and-asylum/common-european-asylum-system_en (accessed January 31 2024).

Fassin, D. (2005). Compassion and repression: the moral economy of immigration policies in France. Cult. Anthropol. 20, 362–387. doi: 10.1525/can.2005.20.3.362

FitzGerald, D. S. (2020). Remote control of migration: theorising territoriality, shared coercion, and deterrence. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 4–22. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1680115

Fontanari, E. (2018). Lives in Transit: An Ethnographic Study of Refugees' Subjectivity across European Borders, 1st Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351234061

Forum Réfugiés (2024). Asile: Les principales données pour l'année 2023 en France. Available online at: https://www.forumrefugies.org/s-informer/publications/articles-d-actualites/en-france/1415-asile-les-principales-donnees-pour-l-annee-2023-en-france (accessed February 15, 2024).

Frontex (2023). EU's external borders in 2022: Number of irregular border crossings highest since 2016. Available online at: https://frontex.europa.eu/media-centre/news/news-release/eu-s-external-borders-in-2022-number-of-irregular-border-crossings-highest-since-2016-YsAZ29 (accessed March 30, 2024).

Glorius, B., and Doomernik, J. (2020). Geographies of Asylum in Europe and the Role of European Localities. New York, NY: Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-25666-1

Grande, E., Schwarzbözl, T., and Fatke, M. (2019). Politicizing immigration in Western Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 26, 1444–1463. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1531909

Guiraudon, V. (2018). The 2015 refugee crisis was not a turning point: explaining policy inertia in EU border control. Eur. Polit. Sci. 17, 151–160. doi: 10.1057/s41304-017-0123-x

Havrylchyk, O., and Ukrayinchuk, N. (2017). The Impact of Limbo on the Socio-Economic Integration of Refugees in France. Munich: ifo Institut - Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der Universität München 15, 6.

Henrekson, M., Öner, Ö., and Sanandaji, T. (2020). “The refugee crisis and the Reinvigoration of the Nation-State: does the European union have a common asylum policy?” in The European Union and the Return of the Nation State: Interdisciplinary European Studies, ed. A. Bakardjieva Engelbrekt, K. Leijon, A. Michalski, and L. Oxelheim (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 83–110. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-35005-5_4

Hynie, M. (2018). The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: a critical review. Can. J. Psychiatry 63, 297–303. doi: 10.1177/0706743717746666

Kang, Y.-D. (2021). Refugee crisis in Europe: determinants of asylum seeking in European countries from 2008–2014. J. Eur. Integr. 43, 33–48. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2020.1718673

Khosravi, S. (2010). 'Illegal' Traveller: An Auto-Ethnography of Borders. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230281325

Kreichauf, R. (2018). From forced migration to forced arrival: the campization of refugee accommodation in European cities. Comp. Migr. Stud 6:7. doi: 10.1186/s40878-017-0069-8

Krzyżanowski, M., Triandafyllidou, A., and Wodak, R. (2018). The mediatization and the politicization of the “refugee crisis” in Europe. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 16, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2017.1353189

Kuschminder, K. (2021). Before disembarkation: eritrean and Nigerian migrants journeys within Africa. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 47, 3260–3275. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804192

Laakkonen, V. (2022). Deaths, disappearances, borders: migrant disappearability as a technology of deterrence. Polit. Geogr. 99:102767. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102767

Lauwers, N., Orbie, J., and Delputte, S. (2021). The politicization of the migration–development nexus: parliamentary discourse on the european union trust fund on migration. J. Common Mark. Stud. 59, 72–90. doi: 10.1111/jcms.13140

Léonard, S., and Kaunert, C. (2019). Refugees, Security and the European Union. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429025976

Lien, L., Thapa, S. B., Rove, J. A., Kumar, B., and Hauff, E. (2010). Premigration traumatic events and psychological distress among five immigrant groups. Int. J. Ment. Health 39, 3–19. doi: 10.2753/IMH0020-7411390301

Lusk, M., Terrazas, S., Caro, J., Chaparro, P., and Puga Antúnez, D. (2021). Resilience, faith, and social supports among migrants and refugees from Central America and Mexico. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 23, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2019.1620668

Mazzilli, C., and Lowe, C. (2023). Public narratives and attitudes towards refugees and other migrants: Portugal country profile. London: ODI.

McAuliffe, M., and Triandafyllidou, A, . (eds). (2021). World Migration Report 2022. Geneva: International Organizationfor Migration (IOM). doi: 10.1002/wom3.25

McCann, K., Sienkiewicz, M., and Zard, M. (2023). The role of media narratives in shaping public opinion toward refugees: a comparative analysis. Migration Research Series, N° 72. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Mountz, A., Wright, R., Miyares, I., and Bailey, A. J. (2002). Lives in limbo: temporary Protected Status and immigrant identities. Glob. Netw. 2, 335–356. doi: 10.1111/1471-0374.00044

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781412995658

Mulvey, G. (2010). When policy creates politics: the problematizing of immigration and the consequences for refugee integration in the UK. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 437–462. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feq045

Papatzani, E., Psallidaki, T., Kandylis, G., and Micha, I. (2022). Multiple geographies of precarity: accommodation policies for asylum seekers in metropolitan Athens, Greece. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 29, 189–203. doi: 10.1177/09697764211040742

Phillimore, J., and Goodson, L. (2006). Problem or opportunity? Asylum seekers, refugees, employment and social exclusion in deprived urban areas. Urban Stud. 43, 1715–1736. doi: 10.1080/00420980600838606

Portugal (2030). Available online at: https://portugal2030.pt/en/portugal-2030/o-que-e-o-portugal-2030/ (accessed March 30, 2024).

Renner, A., Hoffmann, R., Nagl, M., Roehr, S., Jung, F., Grochtdreis, T., et al. (2020). Syrian refugees in Germany: perspectives on mental health and coping strategies. J. Psychosom. Res. 129:109906. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109906

Riva, S. (2022). Tracing invisibility as a colonial project: indigenous women who seek asylum at the U.S.-Mexico Border. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 20, 584–597. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2021.1955173

Ryan, D., Dooley, B., and Benson, C. (2008). Theoretical perspectives on post-migration adaptation and psychological well-being among refugees: towards a resource-based model. J. Ref. Stud. 21, 1–18. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem047

Ryan, D. A., Kelly, F. E., and Kelly, B. D. (2009). Mental health among persons awaiting an asylum outcome in western countries. Int. J. Ment. Health 38, 88–111. doi: 10.2753/IMH0020-7411380306

Sajjad, T. (2018). What's in a name? ‘Refugees', ‘migrants' and the politics of labelling. Race Class 60, 40–62. doi: 10.1177/0306396818793582

Sales, R. (2002). The deserving and the undeserving? Refugees, asylum seekers and welfare in Britain. Crit. Soc. Policy 22, 456–478. doi: 10.1177/026101830202200305

Silove, D., Ventevogel, P., and Rees, S. (2017). The contemporary refugee crisis: an overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry 16, 130–139. doi: 10.1002/wps.20438

Snel, E., Bilgili, Ö., and Staring, R. (2021). Migration trajectories and transnational support within and beyond Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 47, 3209–3225. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804189

Sourander, A. (2003). Refugee families during asylum seeking. Nord. J. Psychiatry 57, 203–207. doi: 10.1080/08039480310001364

Stuart, J., and Nowosad, J. (2020). The influence of premigration trauma exposure and early postmigration stressors on changes in mental health over time among refugees in Australia. J. Trauma. Stress 33, 917–927. doi: 10.1002/jts.22586

Tazzioli, M. (2017). Containment through mobility at the internal frontiers of Europe. Available online at: www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies (accessed May 1, 2024).

Toma, S., and Castagnone, E. (2015). What drives onward mobility within europe? The case of senegalese migrations between France, Italy and Spain. Population 70, 65–95. doi: 10.3917/popu.1501.0069

UNHCR (2021). Global Trends Report 2021. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/publications/brochures/62a9d1494/global-trends-report-2021.html (accessed May 1, 2024).

United Nations (2016). Definitions, Refugees and Migrants. Available online at: https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions (accessed May 1, 2024).

United Nations Academic Impact (n.d.). Integrating Refugee Students: A Model of a Portuguese University. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/integrating-refugee-students-model-portuguese-university (accessed May 1 2024).

Visintin, E. P., Green, E. G. T., and Sarrasin, O. (2018). Inclusive normative climates strengthen the relationship between identification with Europe and tolerant immigration attitudes: evidence from 22 countries. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 49, 908–923. doi: 10.1177/0022022117731092

Walia, H. (2021). Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Willen, S. S., Selim, N., Mendenhall, E., Lopez, M. M., Chowdhury, S. A., Dilger, H., et al. (2021). Flourishing: migration and health in social context. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e005108. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005108

Yildiz, U., and Sert, D.S. (2021). Dynamics of mobility-stasis in refugee journeys: case of resettlement from Turkey to Canada. Migr. Stud. 9, 196–215. doi: 10.1093/migration/mnz005

Keywords: asylum seeker, migrant, migration, transit, livelihood, resilience, France, asylum

Citation: De Jesus M, Warnock B, Moumni Z, Hassan Sougui Z and Pourtau L (2024) Strategies of survival, livelihood, and resistance in transit: a narrative analysis of the migration trajectory of a Guinean asylum seeker in France. Front. Hum. Dyn. 6:1285316. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2024.1285316

Received: 29 August 2023; Accepted: 20 June 2024;

Published: 10 July 2024.

Edited by:

Nergis Canefe, York University, CanadaReviewed by:

Guntars Ermansons, King's College London, United KingdomJennifer Moore, University of New Mexico School of Law, United States

Copyright © 2024 De Jesus, Warnock, Moumni, Hassan Sougui and Pourtau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria De Jesus, ZGVqZXN1c0BhbWVyaWNhbi5lZHU=

Maria De Jesus

Maria De Jesus Bronwyn Warnock

Bronwyn Warnock Zoubida Moumni4

Zoubida Moumni4