94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 15 March 2024

Sec. Migration and Society

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2024.1249805

Hailu Megersa

*

Hailu Megersa

*

Tesfaye Tafesse

Tesfaye TafesseRecent research suggests a significant rise in both international and intra-African migrations, with South Africa emerging as the primary destination for irregular migrants in the region. However, the phenomenon of irregular migration to South Africa has received limited attention despite the growing number of migrants hosted by the country. To address this gap, this study adopts a concurrent cross-sectional mixed-methods approach to explore the patterns of inter-state irregular migration in Africa, specifically focusing on Ethiopian migrants to the Republic of South Africa (RSA). The investigation draws on quantitative data collected from 316 migrant returnees, as well as qualitative in-depth interviews and focus-group discussions. The findings of this study reveal that there is a decline in the patterns of Ethiopian irregular migration to the RSA within the past decade due to tight legal restrictions. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the pattern of irregular migration, leading to a decline in the number of migrants from mid-2018 to 2020 due to stringent border closures. Irregular migration to the RSA tends to be temporary, with an increasing migrants returning to their home country once they have achieved economic success or as they encountered precarious conditions at the destination. Addressing the root causes that drive migration, improving border control mechanisms, and implementing inclusive integration strategies are key steps toward minimizing the risks and maximizing the benefits associated with this migration phenomenon.

Throughout its history, the people of Africa have been involved in cyclical and seasonal migration, as well as permanent settlement in new territories that provide sustenance and support livelihoods (Kane and Leedy, 2013). The prevailing notion of Africans desperately striving to leave the continent, particularly for Europe, is discredited by the reality of intra-African migration (Awumbila, 2017). Africa is often depicted as “a continent on the move,” (a continent experiencing a mass exodus), a place where constant movement is the norm. However, the truth is that the majority of migration actually occurs within the borders of Africa itself (Moyo, 2021). Migratory patterns within Africa are on the rise, both from and within the continent, yet a significant number of African migrants choose to remain on the continent (UN DESA, 2020; IOM, 2021). In comparison to other regions, Africa has the lowest rate of intercontinental migration (Flahaux and de Haas, 2016). These portrayals of an African “exodus” and a constantly mobile continent arise from an imbalance in migration literature, which primarily focuses on the Global North or the political agendas of Europeans seeking to restrict migrant access. This overlooks the fact that the majority of migration actually takes place within the Global South (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, 2020).

Migration movements in Africa are currently a heavily debated topic, as African states and policymakers face challenges regarding safe migration and border management limitations (Adamson, 2006). The prevailing notion is that Africans are only mobile when circumstances are unfavorable. It is believed that Africans only relocate when they are compelled to do so by external forces beyond their control. However, the attempts made by African states to restrict mobility contradict the reality of Africa’s extensive history of flexible mobility. Africa is a continent that comprises interconnected spaces, which have constantly experienced shifts, displacements, and reconfigurations through various events such as wars, conquests, and the movement of goods and people (Nyamnjoh, 2013). Despite ongoing efforts for regional and continental integration in Africa, little to no attention is given to policies aimed at ensuring the social protection of migrants. The absence of a pan-African ideology that prioritizes the social protection of migrants leaves them vulnerable to xenophobia, abuse, and exploitation (Moyo, 2021).

Within Africa, destination countries have presented both irregular migration and regular human mobility as threats to the economic and physical well-being of their own citizens (Castles, 2018). In South Africa, for instance, there is a significant outcry for policies that target foreigners, particularly those from other African countries, who are often scapegoated as the source of HIV/AIDS, a primary cause of crime, and a perceived threat to South African jobs and cultural values (Nyamnjoh, 2013). Overall, the issue of migration in Africa is multifaceted and complex. It requires a comprehensive approach that takes into account the historical context of mobility on the continent and addresses the social protection of migrants to prevent discrimination and exploitation.

Human mobility in Africa exhibits an irregular pattern, with a significant and increasing occurrence both within and beyond the Horn of Africa. The migration landscape in this region is characterized by a mixture of irregular migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees (Horwood and Frouws, 2021). Irregular migration is favored by migrants as the regular migration channels pose significant challenges that are financially inaccessible to the impoverished population. Additionally, obtaining an entry visa to the Republic of South Africa is virtually impossible. As a result, around 95 percent of Ethiopian migrants to South Africa are irregular migrants (Girmachew, 2021).

The majority of irregular migrants originating from Ethiopia, approximately two-thirds, are smuggled through Kenya using a route that passes through Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, and Mozambique before reaching South Africa (Frouws and Horwood, 2017; Meron, 2020). However, the paths taken by irregular migrants to South Africa are highly dynamic and fluid, constantly changing to evade border controls and checkpoints set up by authorities (Frouws and Horwood, 2017). Within the Horn of Africa, 80% of Ethiopians and 20% of Somalis opt for the southern route as their migration path to South Africa. Consequently, estimates suggest that between 13,000 and 20,000 individuals have been migrating along this route annually for the past 15 years (Horwood and Forin, 2019).

This article explores the patterns of irregular migration in Africa, specifically highlighting the movement of Ethiopian migrants from the Kembata-Tembaro Zone to the Republic of South Africa (RSA) via the ‘Southern Route’ within the last decade. The study primarily focuses on the patterns of migration in terms of migrants’ demographics and socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as the spatial and temporal patterns observed in Ethiopian migration toward the RSA.

Migration can be broadly described as a change in residence, whether it is a permanent or semi-permanent shift, that occurs either voluntarily or involuntarily. This definition encompasses both internal and international migration (Sironi et al., 2019). Regardless of the duration, ease, or difficulty of the journey, migration entails three fundamental aspects: the place of origin, the intended destination, and a series of intervening barriers or challenges (Lee, 1965). Hein de Haas, in his work, presents an alternative perspective on human mobility. He defines it as the capacity or freedom of individuals to choose their place of residence, which includes the option to remain in their current location, rather than solely focusing on the actual act of relocation or migration itself (2021:4). However, it is important to note that this particular definition is not universally accepted by all countries. Each nation employs distinct criteria to classify individuals as international migrants, as highlighted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2019).

The concept of irregular migration does not have a universally accepted definition. Various sources, including IOM (2021), Robin (2019), and UNICEF (2017), acknowledge the lack of clarity in defining irregular migration. It encompasses several scenarios, such as individuals intentionally crossing borders without permission, those unintentionally crossing borders without authorization, individuals becoming irregular after initially entering a country legally, children born to irregular migrants, and people crossing borders through human trafficking (Mcauliffe and Koser, 2017). Irregular migration involves both irregular entry and irregular stay (Provera, 2015:4). The term “irregularity” refers to the legal status that describes the relationship between a migrant and one or more states. This irregularity arises from conflicts between the social space’s logic, which promotes the free movement of people and goods through concepts like free-market economy, globalization, and transnationalism, and the political space’s logic, where states aim to limit and regulate mobility factors to maintain their politically constructed, historically and ideologically distinct identity and sovereign power within their territorial jurisdictions (Echeverría, 2020).

Many empirical sources, including Amelina and Horvath (2017), IOM (2021), Mcauliffe and Koser (2017), and the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS, 2015), mention irregular migration is associated with the term “problem.” In contrast to regular migration, irregular migration is often regarded as a “problem, risk, or danger” that requires neutral or more aggressive responses. It is considered a necessary problem that should be addressed or confronted (Robin, 2019). Castles et al. (2014) and Girmachew (2019) criticize the dichotomy between regular and irregular, legal and illegal migration, as immigrant status can easily and frequently change between categories. Furthermore, migrants utilize both regular and irregular channels, blurring the distinction between the two (Girmachew, 2019). Such labeling stems from legal provisions that wrongly dichotomize migrants into the categories of “deserving and undeserving,” and differentiate between “legitimate and illegitimate” (UNICEF, 2017). The line between irregular and regular migration is not always clear-cut, as individuals considered irregular migrants may be legalized through special regularization schemes provided by host states. Conversely, regular migrants can become irregular if their permits expire (King, 2012).

The complexity and diversity of migration processes worldwide are the main factors contributing to the difficulty in defining terms such as legal, illegal, regular, and irregular migration. The term “illegal” carries negative connotations that can dehumanize and stigmatize migrants, hindering empathy and understanding. It refers to the movement of individuals across borders without proper authorization, documentation, or in violation of a country’s immigration laws (Echeverría, 2020). On the other hand, legal migration involves the movement of individuals across borders in compliance with the immigration laws and regulations of the destination country (Provera, 2015:4). The term “illegal” fails to capture the nuanced and often desperate circumstances that migrants face, oversimplifying their complex situations (Casarico et al., 2015). In contrast, irregular migration encompasses a broader range of scenarios. It includes intentional border crossings without permission, unintentional crossings, becoming irregular after initially entering a country legally, children born to irregular migrants, and individuals who are victims of human trafficking (Mcauliffe and Koser, 2017). Irregular migration refers to migrants who fail to adhere to existing immigration procedures and regulations (McAdam, 2019). In this context, the term “irregular migration” is preferred as it is considered a more neutral way to describe the movement of individuals who do not meet the legal requirements for migration or stay in a particular country. It acknowledges that people may migrate due to various reasons such as conflicts, economic circumstances, or lack of legal pathways, rather than as a deliberate act of violating laws (Echeverría, 2020).

Irregular migrants along the South Africa were assisted by a network of smugglers locally known as delala (broker). The brokers in the migrants locality act as informal facilitators of migration through provision of information to the aspiring migrants, arranging the migration process, facilitating informal money transfers (Fekadu et al., 2019) and they used to provide bogus travel documents purportedly from Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia [Mixed Migration Centre (MMC), 2019]. The choice of the route and arrangement of transport and other facilities for irregular migrants are prepared by informal local smugglers or brokers (delalas) to cross the borders (Frouws and Horwood, 2017). Empirical studies confirmed that the brokers’ propaganda to recruit aspired migrants was attractive to pull and lure them to join irregular migration (Bisrat, 2014; Messay and Teferi, 2017). A qualitative study by Yordanos and Freeman (2022) indicates the smuggling business was boosted with the facilitating role the smugglers along the routes to South Africa in response to state’s restrictive policy measures of border control and closure that in turn resulted in proliferated number of irregular migrants. They conclude that unlike the family networks and a few actors involved in the facilitation of irregular migration for the pioneer migrants, later changed into a thrived smuggling business joined by multiple actors that extend from the source through transit to the destinations and beyond.

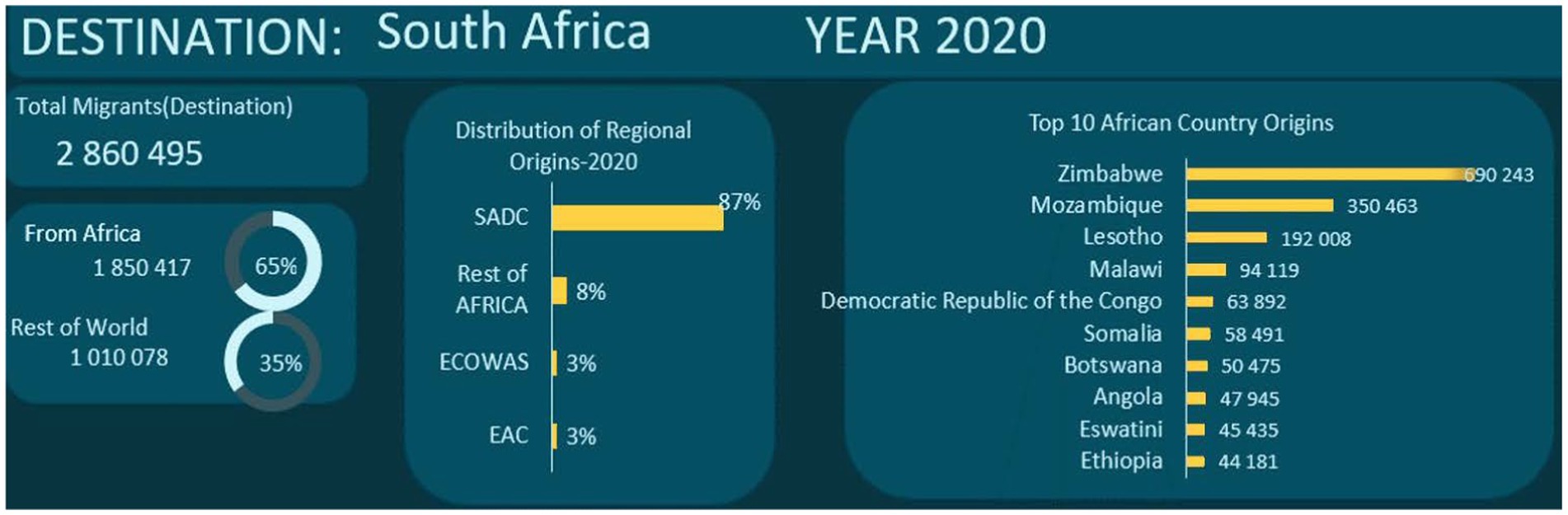

Throughout its history, the Republic of South Africa has witnessed different migration patterns. These patterns can be classified into three primary waves: colonial migration, migration during the apartheid era, and migration in the post-apartheid period. The colonial history of South Africa enticed European settlers, predominantly from the Netherlands, Britain, and Germany. In the 17th century, the Dutch established a colony, which was later taken over by British control in the 19th century. As a result, there was a notable influx of Europeans who migrated to South Africa in search of economic prospects, land, and resources (Ross, 1993). In the period of apartheid (1948–1994), the South African government enforced stringent policies of racial segregation that had a significant impact on migration patterns. These policies involved the forced relocation of millions of Black Africans from rural regions to designated homelands called Bantustans, with the aim of maintaining racial segregation. Furthermore, restrictions on migration were imposed on non-white populations, restricting their mobility and opportunities within the country (Crush, 1995; Posel, 2001). After the abolition of apartheid, South Africa witnessed a rise in migration from neighboring African nations, as well as from other parts of the world like Asia and the Americas. The allure of economic prospects, political stability, and the country’s reputation for democracy has attracted migrants in search of a brighter future. However, this influx has also sparked discussions and difficulties concerning matters such as xenophobia and the integration of diverse communities (Crush and Tevera, 2010; Figure 1).

Figure 1. South Africa as a destination for African migrants. Source: Mutava (2023). Analysis of trends and patterns of migration in Africa, p. 34.

The pattern of migration in sub-Saharan Africa mainly occurs within the region and the numbers of migrants to the rest part of the world also increasing (IMF, 2016; Mutava, 2023). Sub-Saharan region of Africa have relatively low rate of migration about 2% of the region’s population. However, the stock of migrants growing steadily due to the highest growth of population (IMF, 2016). In Africa, countries such as South Africa Nigeria, Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire and Libya have major migrant hosting countries. From these, South Africa is the major migrants’ destination followed by Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria (Tsion, 2017; UNECA, 2017).

The pattern of Ethiopians’ irregular migration to South Africa is also shaped by complex social relations, access to communication technologies, information flows, and money transfer systems. Communication technologies are vital for smugglers to hold networks and money transfers (Fekadu et al., 2019). An irregular migration from Ethiopia is also determined by the state restriction policy on mobility. Through the land routes the migrants from Kembata areas move from Hossana via Dilla to Moyale. From Moyale they cross the borders of Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi and Mozambique/Zimbabwe to enter South Africa. Most of Ethiopian emigrants mainly travel on foot or in vehicle, some migrants who can afford used to fly part or their entire journey (Frouws and Horwood, 2017; Meron, 2020).

Recent studies on Ethiopia’s international migration (Assefa et al., 2017; Girmachew, 2019, 2021; Woldemichael and Getu, 2020; Tekalign, 2021b) have indicated a notable increase in the number of irregular migrants. Previous research conducted by Girmachew (2014) and Habte (2015) suggests that migration from Ethiopia, which was previously driven by conflicts, has now shifted toward irregular migration primarily driven by economic factors. Furthermore, Tekalign (2021b) and Girmachew (2019, 2021) argue that irregular migration is preferred over regular channels due to the significant challenges and unaffordability associated with regular migration, particularly for individuals with limited financial resources. Therefore, as highlighted by Woldemichael and Getu (2020), gaining a deeper understanding of the patterns of irregular migration is essential and goes beyond the limited perspective offered by the traditional push-pull model.

Ethiopians in South Africa are a significant immigrant group in terms of size, although much of their immigration is undocumented and irregular (Girmachew, 2019; Mutava, 2023). The migration from Hadiya and Kembata regions is predominantly driven by the presence of smugglers, creating an enabling environment for individuals to migrate (Kinfe, 2019; Meron, 2020). Young people often view migration as a means to fulfill personal, family, and social expectations, influenced by stories of successful migrants and the positive perception of migration within their families (Fekadu et al., 2019). Previous studies conducted in the area (Assefa et al., 2017; Girmachew, 2019; Tekalign, 2021a) have shown an increase in the number of migrants from this region using irregular channels, despite the government’s restrictive measures and xenophobic reactions from host communities. Ethiopian emigration to South Africa began in the mid-1990s, but a significant wave of emigration from the study area started in 2000 (Yordanos and Zack, 2019). As a result, certain villages and districts within the Kembata-Tembaro zone, such as Damboya, Angacha, and Doyogena, have become known as typical migrant areas (Girmachew, 2019; Tekalign, 2021a).

Migration theory aims to address various questions related to the phenomenon of migration, including the reasons behind migration, the individuals or groups that choose to migrate or stay, the patterns of migration in terms of location and time, and how migration perpetuates itself (Carling and Collins, 2018). In order to better understand migration, different theories emerged from various social science disciplines since the late 19th century. Migration theories can be classified into two major theoretical paradigms of functionalist and historical-structural social theory (de Haas et al., 2020). For instance, the neoclassical theory (from economics), push-pull models and migration systems theories (from geography and demography) and network theory (from sociology) can be positioned under functionalist social theory, considered migration as income optimization by individuals or families through cost–benefit analysis (Semela and Cochrane, 2019; de Haas, 2021). Similarly, the neo-Marxist theory, dependency theory, world systems theory, dual labor market theory and critical globalization theory can be located under historical-structural social theory, and interpreted migration formed by structural economic and power inequalities. This gives emphasis to the exploitation of poor and vulnerable people by the powerful elites (Girmachew, 2014; de Haas, 2021).

The Push-Pull theory assumes that the origin of international migration is rooted in the economic backwardness of developing countries (Mercandalli et al., 2020). Accordingly, such economic conditions like lower wages, high unemployment and underemployment, slow economic growth or stagnation and poverty, and population growth in rural areas cause a Malthusian pressure on natural and agricultural resources, considered as “push” factors and the “pull” or attraction forces in the destination countries include factors like employment, higher wages, and better welfare systems. These are considered the causal variables that explain the why and how of international migration as well as causes for both legal and illegal migration toward the industrialized countries (de Haas, 2014). Urbański (2022) classified the push factors of migration into economic, political and social. Economic push factors include unemployment or the existence few jobs and overpopulation in the developing countries push people to migrate into developed world (Ibrahim et al., 2019). Lack of healthcare services and absence of religious tolerance are among the social factors that push migrants to move into another places in search of better opportunities (Khalid and Urbański, 2021). While the political push factors influence migration include war, terrorism, prejudiced justice system and lack of government tolerance (Urbański, 2022).

The push-pull migration theory also criticized as a simple description of determinants of migration without identifying their relative importance (Hochleithner, 2018). In addition, poverty and demographic factors alone insufficient conditions to cause migration (European Union, 2018; Bufalini, 2019). The wage deferential is also inadequate to address factors behind irregular migration. For instance, the ability to migrate is related to cost of migration than solely depend on wage gaps. Thus, it was not the poorest poor who migrate as seen from the case of Africa’s irregular migrants who paid between $1,200 and $1,500 for smugglers (Ogu, 2017).

Conversely, the new economics of labor migration argues that the reason to migrate is dependent not only on the labor market but also on conditions of other markets such as the capital market or unemployment insurance market (Grüne and Adele, 2017). The new economics of labor migration put risk sharing at the center of household’s migration decision making, as individuals migrate as part of household strategy to diversify income sources and improve household livelihood security by spreading risk (Mercandalli et al., 2020; Bakewell and Sturridge, 2021). This theory recognizes migration as a household decision rather than individual decision making. In this case, migration allows households income diversification in the case of failure of local income sources. People migrate abroad on a temporary basis rather than permanently to diversify household income and to accumulate cash to solve household economic problems that had initially forced them to emigrate (de Haas, 2014; Massey, 2015; Wickramasinghe and Wimalaratana, 2016).

The new economics developed theoretical premises that are different from the neoclassical one (Porumbescu, 2015). First, migration decisions should not be an individual rather family decision where households are culturally defined as production and consumption units (Anggoro, 2019; de Haas et al., 2020). Second, for international migration to occur, wage difference is not a necessary condition. In the absence of wage difference, families have good reasons to minimize risks related to economic gaps through migration (Porumbescu, 2015; Hochleithner, 2018). Third, it is not possible to exclude international migration from the local one. Economic development in the area does not guarantee a reduction in migration. Fourth, international migration never ceases at a moment of elimination of wage differences between sending and receiving areas. Reasons to migrate may continue to persist (de Haas et al., 2020). Fifth, migration influenced by national governments through policies in the field of the labor force, capital insurance markets, social security systems (like unemployment insurance) is among the key factors that influence the decision to emigrate (Porumbescu, 2015).

The NELM is criticized due to the emphasis it put on micro-level factors, consequently, it fail to address contexts related to historical factors and to establish linkage between household decision making and macro-structural factors. Therefore, the roles played by government, policies, labor markets, and power asymmetries (Mercandalli et al., 2020).

Network theory is among the major theories that need to explain the perpetuation and continuation of migration (Sha, 2021). Migration, according to social capital theory is caused by interpersonal ties between origin and aspired destination of migrants. Accordingly, the potential migrants are able to get information (about the open doors, risks and challenges), and support for the advantage of their movement in minimized expenses through their social capital (Borojo, 2020). Network theory put emphasis on the function of social networks in facilitating, sustaining and perpetuating migration flows. Therefore, network theory provides a new another perspective to the structural analysis focused on wage gaps, push-pull factors, capitalist expansion and market penetration; historical analysis that put emphasis on colonial ties between origin and destinations; and the micro-analysis framework focus on individual and household decision making. And this theory consider an international migration is a social and economic process (Sha, 2021).

Migration networks form a special link that connects migrant-sending communities with host communities in specific areas of destination. Migrant networks are interpersonal links that form ties among potential migrants, earlier migrants, and non-migrants at the origin and destination areas commonly established based on kinship, friendship, and shared community ties (Blumenstock and Tan, 2016; Sha, 2021; Wagner and Katsiaficas, 2021). Migration networks play a crucial role in international migration because they serve as channels of information and resources, provides short-term assistance; reduce migration costs and risks thereby influencing the selection of destination and origin sites (Blumenstock et al., 2021). Networks facilitate information exchanges and perpetuate migration. Moreover, networks play a major role in increased employment opportunities in migrant communities. They also provide information for irregular migrants about low-priced and trusted brokers, the border guides as well as on how to overcome anxiety and what to do in case of deportation (Bircan et al., 2020; Sha, 2021).

Network theory is subject to different critics. The first critic states that the theory inherently focuses on positive outcomes and forgetting about its negative effects (Ahmad, 2015). Second, the research works disproved that the traditional assumption of network theory of gender-neutrality is mistaken (Côté et al., 2015). For instance, study by Ryan (2011) shows that migrant networks promote a higher possibility of migration from men than women. Third, network theory is criticized for ignoring the role of other important migration facilitators like employers, government officials, traffickers, brokers, and others that can be seen beyond the migrant networks (Dekker and Engbersen, 2014; Wagner and Katsiaficas, 2021). Fourth, with the rise of Internet migrants may hunt for other sources of assistance beyond the traditional migrant networks. Potential migrants through the internet may establish contacts with immigrants at the destination whom they do not know and access information about the destination online via YouTube, blogs, Facebook, and other forms. Thus, the role of the Internet and social media in encouraging and facilitating migration is overlooked by migrants’ network theory (Van Meeteren and Pereira, 2018).

However, it is important to note that there is no single theory that can fully explain the complex nature of migration. Instead, multiple theories are needed to comprehensively understand the diverse aspects of migration. Therefore, it is crucial to integrate existing theories from different disciplines to enhance our understanding of migration (de Haas, 2021). In this study, we incorporate theoretical concepts from the new economics of labor migration and the sociological theory of network migration. The assumptions of the network theory are seemed to support an irregular migration from Kembata-Tembaro zone to the Republic of South Africa. For instance, it is very common in the study area for the men who migrated to encourage their close relatives and family members to join the system. As Fekadu et al. (2019) and Yordanos and Zack (2019) stated social ties may bring other community members into the migration stream through the exchange of information and assistance in making the migratory trip and finding housing and employment in a new destination. The role of migration networks in the process of migration is often manifested in the form of having a family member who is a migrant and/or having a friend from the same community who is a migrant. Therefore, social networks are one of the main causes for migration of these people to the RSA. On the other hand, the new economics of labor migration is founded on the assumption that families or households engage in risk-sharing behavior, seeking to maximize income while minimizing and dispersing risks (Stark and Bloom, 1985; de Haas, 2008). The migration decision making process in the study area is align with the idea of this model as the risk sharing behaviors had significant influences on the households’ migration decision.

The study employed a mixed-methods design, specifically a concurrent cross-sectional approach. Our major data source is Ethiopian migrant returnees from South Africa at the time of data collection in 2022. Survey questionnaire, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussion guides were employed to collect the data from the research participants consisted of Ethiopian migrant returnees from South Africa located in the Kembata-Tembaro Zone. For the quantitative survey, a multi-stage sampling technique was used to select samples from the target population. In the first stage, Angecha and Doyogenna districts from the Kembata-Tembaro Zone in the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region were purposively selected due to the higher number of irregular migrants to South Africa. In the second stage, two rural and two urban representative villages (Garba Fandide and Shino Funamura from Angecha district, and Wanjela and Doyogenna from Doyogenna district) were purposively chosen again based on the higher number of irregular migrants. In the third stage, a systematic random sampling method was employed to select a sample of 316 migrant returnees. The number of respondents sampled for each village was determined by calculating proportions relative to the total household size. According to the records of the Social and Labor Affairs Office, a total of 4,906 migrants from South Africa returned to the Kembata-Tembaro Zone during the study period. The sample size for the study was determined using Kothari (2004) formula for determining sample size in finite populations.

The qualitative in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) relied on non-probability sampling methods such as purposive and snowball sampling techniques. Thus, 15 face-to-face in-depth interviews with Ethiopian migrant returnees from the Republic of South Africa (RSA), four interviews with experts from the Labor and Social Affairs office selected purposively, and four face-to-face FGDs with migrant returnees selected through snowball sampling. Participants were interviewed in the selected villages of Garba Fandide, Shino Funamura, Wanjela and Doyogenna. In addition, in-depth interviews were conducted with purposively selected experts of labor and social affairs at districts and zone administrative bodies in the study area.

In this study, both descriptive and inferential methods of data analysis were used. Demographic and socio-economic variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics. For comparing observed proportions of a sample with hypothetical values, Binomial and Multinomial (Chi-square of goodness of fit test) tests were utilized. Qualitative data, collected through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs), underwent transcription, cleaning, and thematic organization. Before the interviews, respondents were given a detailed briefing about the interview process, study objectives, and anonymity protocols. Written consent was obtained from research participants prior to the interviews, and their rights to withdraw from the study at any time were respected.

Throughout the research process, great care was taken to ensure the quality of both qualitative and quantitative data. The focus on data quality began with the preparation of data collection tools. To enhance the reliability of the study instruments, they underwent thorough reviews by colleagues and experts, followed by a pilot test in the field. This process involved rephrasing and simplifying certain questions to ensure they were easily understood by respondents, thus enhancing the validity and reliability of the data.

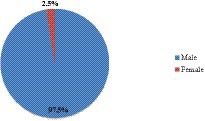

The demographic trends of Ethiopian irregular migration to the Republic of South Africa (RSA) within the past decade have witnessed variations in their age, gender, and socioeconomic background. According to the findings of a survey, the vast majority of these migrants (97.5%) are male, indicating a prominent gender role in engaging in irregular migration to South Africa. The age distribution of migrants reveals that the majority fall within the 25 to 34 years age bracket, closely followed by those aged between 35 and 49 years. This concentration of migrants within the productive age groups highlights their significance in the migration process. In terms of marital status, a significant proportion (60.1%) of the participants was single, while the majority (89.2%) of them had completed their education up to secondary school level or below at the time of migration, indicating their literacy levels (Table 1).

The Figure 2 below indicates that the majority of individuals engaging in irregular migration in the Republic of South Africa are males, accounting for 97.5% of the total. The results of the Binomial test further validate this observation, as they demonstrate a significant difference between the proportions of male and female migrants (p = 0.000). The lower percentage of female migrants can likely be attributed to two main factors. Firstly, the nature of irregular migration to the Republic of South Africa involves extensive travel by car and on foot, spanning several months and posing significant risks while crossing national boundaries of various African states. Secondly, the demanding and hazardous nature of employment opportunities in the Republic of South Africa does not incentivize females to migrate. These findings are supported by insights gained from focus group discussions with migrant returnees. According to their accounts, the Republic of South Africa is perceived as a destination exclusively suitable for male migrants due to the numerous risks encountered during the journey and at the final destination. As a result, female migrants tend to prefer the Arab Gulf States, where air travel offers a safer mode of transportation, and they are employed in domestic work instead of engaging in physically demanding door-to-door trades like their male counterparts in South Africa. However, it should be noted that recent years have witnessed an increase in female migration to the Republic of South Africa for reasons such as marriage or employment in tuck-shops.

Figure 2. Sex of migrants. Source: Kembata-Tembaro zone labor and social affairs office profile of irregular migrants, 2022.

Age is another significant demographic variable that necessitates assessment, as it is crucial for understanding the patterns of irregular migration. Based on the cross-sectional survey data, it can be inferred that the majority of irregular migrants to South Africa belong to the economically productive age groups. Approximately 42.4% of migrants fall within the 25–34 age range, 36.1% are aged between 35 and 49, and 16.8% are in the 15–24 age category. The results of the chi-square test also reveal a statistically significant difference in the proportions of migrants across different age categories (p-value =0.000). Consequently, it can be concluded that 99.4% of migrants are within the working-age groups, actively contributing to the economy. While migration occurs across various age levels, multiple studies have consistently indicated that the majority of migrants are young adults (Tadesse, 2012; Habteyes, 2016; Wondimu, 2016; Stocchiero, 2017; Nyikahadzoi et al., 2019).

Marital status is a demographic characteristic that influences individuals’ migration decisions. The survey report indicate that the majority of participants are single (60.1%) followed by married (38.6%), together accounting for a total of 98.7%. Divorced and widowed individuals constituted the smallest percentage of migrants, each making up approximately 0.6%. Empirical studies (Massey et al., 1993; Horváth, 2008; Roux et al., 2011; Teshome et al., 2013; Henok et al., 2017) indicate migration of young unmarried male are considered as a “rite of passage” or transition to manhood as well as a social success of attaining assets and ability to support family. Moreover, the young generation is expected to replace the old migrant generation and working abroad is seen as exerting strong pressure on the young unmarried men to migrate, for instance, in Senegal (Mondain and Diagne, 2013; Dibeh et al., 2018; Yendaw, 2021; Dennison, 2022). Similarly, empirical studies in Latin America indicates that being married discourage migration (Mincer, 1978; Etling et al., 2018; Czaika and Reinprecht, 2020). The participants in focus group discussions and in-depth interviews also mentioned that the prevalence of young unmarried individuals migrating to South Africa is partly driven by a household strategy to send singles and partly influenced by social expectations for unmarried youth to seek better opportunities abroad and remit money back to their families. The second factor influencing migration is related to network migration, which is financed through family and friendship networks of previous migrants, as well as debt migration facilitated by brokers both at the origin and destination.

When examining the educational background of the respondents, it was found that the majority had completed secondary education (38%) or primary education (25.9%). The results indicate that about 63.9% of irregular migrants to the Republic of South Africa had only attended primary and secondary levels. Additionally, 10.8% of the participants had received higher education. The Chi-square test result (p-value =0.000) suggests a significant difference in the educational attainment of migrants. These findings align with previous studies (Zerihun and Asnake, 2018; Asmelash and Litchfield, 2019; Woldemichael and Getu, 2020) indicating that the majority of migrants have attained primary and/or secondary education. The educational status of migrants, primarily at the primary and secondary school levels, may indicate a high rate of school dropout, suggesting that many migrants are more likely to abandon their education either before or during their migration. The discussants in focus group discussions also emphasized that students are currently pursuing their education with less enthusiasm as migration is the aspiration for everyone. Their interest in education has significantly declined, and many of them reluctantly complete only up to grade 8 or grade 12 due to family pressure (Figure 3).

The place of birth and residence is an important demographic factor that influences an individual’s decision to migrate. According to the findings of the survey, approximately 58.5% of migrants come from rural areas, while about 41.5% originate from urban areas. The results of the binomial test indicate a significant disparity in the place of birth and residence between rural and urban regions (p-value = 0.003). The study participants also observed a rise in the number of migrants from urban areas compared to rural residents due to the rapid urbanization in those areas. Consequently, former rural communities are now being transformed into emerging towns, while others are becoming district centers. Furthermore, a study conducted by Kelemework et al. (2017) revealed the vulnerability of urban youth to irregular migration, as they are more exposed to migration information and influence. Participants of in-depth interviews emphasized the role of telecom services, particularly the Internet, in providing young people with ample information through Internet cafes in district towns or via data services on smartphones. This accessibility to information has enabled previous migrants to attract their friends and family members by inviting them to explore business opportunities through virtual platforms such as Imo, Vibber, or WhatsApp. As a result, the reliance on hearsay from brokers, migrant returnees, and their families has now been complemented or even replaced by more advanced virtual information systems among aspiring young migrants.

To understand migration patterns, it is crucial to assess significant demographic variables such as occupation type and income of migrants. The survey results indicate that a large proportion of respondents (83%) were employed before migrating, while approximately 17% were unemployed. The binomial test result (p-value = 0.000) confirms a statistically significant difference in migration between employed and unemployed individuals. Additionally, about 24% of respondents had multiple occupations before migrating. The primary occupations of migrants prior to their migration to RSA included farming (32.3%), private business (31.3%), daily laborers (23.4%), merchants (22.5%), government employees (4.4%), and private or NGO employees (3.5%). The average monthly income of migrants was 2313.95 birr (1$ = 51.926703 birr), with a minimum income of 500 birr and a maximum income of 5,400 birr. The Chi-square test result (p-value = 0.000) also highlights a significant disparity in the median income of migrants compared to the median income in the country. This aligns with Zerihun and Asnake (2018) study, which identifies low income as push factors for migration, driven by the pursuit of a better life and the desire to support their families (Figure 4).

In an effort to evaluate the distribution of family size and land size among migrant households, an analysis was conducted. The family sizes observed ranged from 1 to 16, with an average of 6.16. It is evident that the sampled households in the study area have considerably larger sizes compared to both the regional average of 4.9 and the Kembata-Tembaro zone average of 5.5 (SNNPR BoFED, 2019). The statistical Chi-square test (p-value = 0.000) provides evidence of a significant disparity between the median family size of migrant households and the median family size of the Kembata-Tembaro Zone. This indicates that there is substantial population pressure on the available resources in the study area. During focus group discussions and in-depth interviews, participants emphasized the scarcity of farmlands, which compelled the younger generation to resort to migration, both internally and internationally, as a last option. It is important to note that land serves as the fundamental productive resource for agricultural activities, yet it is sparsely allocated among the respondents. The average land size for migrant households is 0.898 hectares, with possession ranging from a minimum of 0.01 hectares to a maximum of 4 hectares. The Chi-square test result (p-value = 0.013) demonstrates a significant difference in the average farmland size of migrant households compared to the national average.

The movement of people across borders in Africa is influenced by historical connections established during the colonial era and shared language ties (Idemudia and Klaus, 2020). However, Ethiopia stands apart from other African and European nations that were never colonized, as it does not adhere to this established migration pattern. Consequently, Ethiopian migration lacks a distinct route, resulting in the dispersal of Ethiopians across various continents (Girmachew, 2021). The migration pattern within Africa itself is highly unpredictable, with the Republic of South Africa emerging as a significant destination for irregular migrants (UNCTAD, 2018).

The survey result indicates that a significant number of Ethiopian migrants from the southern regions of the country are predominantly choosing the southern route as their path toward the Republic of South Africa, which serves as their ultimate destination. As shown in the Table 2 above, about 96.2% of participants respond as the irregular Ethiopian migration originating from Kembata aims to find better opportunities in the dreamed-of land of the Republic of South Africa. Nevertheless, small percentage participants (3.8%) respond as they aspired to go beyond and travel through the Republic of South Africa to reach countries in the Global North such as the United States of America, Europe, and Australia. The majority of individuals participating in in-depth interviews consistently express their desire to settle in the Republic of South Africa, considering it as their ideal place for pursuing a better life since the mid-1990s. Therefore, their decision to migrate to the Republic of South Africa is primarily driven by economic prospects. This funding is consistent with earlier studies in the area by Girmachew (2019) and Dereje (2022).

The survey result also shows that despite the risks involved in crossing international borders within various African countries, a considerable number of Ethiopians opt for irregular migration to the Republic of South Africa. Accordingly, respondents replied that the reasons behind choosing this mode of migration include its cost-effectiveness compared to regular routes (76.3%), the lengthy and expensive bureaucratic processes associated with regular migration (50.3%), the lack of access to regular routes for entering the Republic of South Africa (39.9%), influence from brokers (35.4%), and difficulties in obtaining an entry visa to the Republic of South Africa (30.1%). During in-depth interviews, participants mentioned that traveling to the Republic of South Africa through regular channels is practically impossible due to the struggle of meeting legal requirements, particularly obtaining an RSA visa. Moreover, the lawful process is time-consuming, challenging, and costly, which poses significant barriers for those with limited financial means. Consequently, the easiest and preferred way to reach the Republic of South Africa is to rely on the services of brokers, which are cost-effective, affordable, and time-saving.

Consequently, only a few irregular migrants possess the necessary legal documents for their migration to the Republic of South Africa. The survey results indicate that approximately 42.1% of migrants possess solely a passport, 29.4% have both a legal passport and visa, and around 28.5% of migrants have neither passports nor visas. Informants highlighted that most migrants acquire visas through brokers using bribes at transit posts, such as Moyale. Legal documents such as passports and visas are irrelevant for migrants who embark on foot journeys. Moreover, land route travelers often follow the advice of smugglers to dispose of or destroy their passports in order to minimize the risk of deportation if they are caught by the police along the journey. It is important to note that this practice is unrelated to the asylum application process for migrants in the Republic of South Africa.

Regarding the mode of transportation and migration routes favored by Ethiopian migrants, the findings of the survey indicate that a majority of emigrants employed mixed transportation systems on the land route, with 77.5% relying on foot travel, 75% using cars, and 2.8% utilizing motorbikes. Around 21.5% of migrants opted for airplanes, while 49.7% chose boats as their means of reaching the Republic of South Africa (RSA). During in-depth interviews, participants revealed that due to the high cost associated with air travel, most migrants preferred to journey via land routes using cars or traveling on foot. However, some individuals still combined air travel with land transportation for certain parts of their journey. Additionally, air travel was predominantly utilized by females, particularly wives or prospective wives of established Ethiopians residing in the RSA. On the other hand, male migrants favored the cheaper and less legally demanding mode of travel to the RSA.

The pattern of irregular migration from Ethiopia is largely influenced by the legal restrictions imposed by the state on mobility. Migrants from the Kembata area, for example, typically travel from Hosanna to Moyale via Dilla. From Moyale, they cross several borders, including those of Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe, in order to enter the RSA. Most migrants stated that within Ethiopia, they usually follow the route from Hosanna to the Moyale highway via Hawassa, while variations in land routes become more pronounced after reaching Moyale. Notably, 69% of survey participants reported using the route from Moyale through Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, and Mozambique to reach the RSA. As highlighted by focus group discussion participants, these routes frequently change due to stricter government control. These changes in routes are not limited to land travel alone; they also impact flight routes. In the past, migrants would take a direct flight from Addis Ababa to Johannesburg, with Addis Ababa serving as a transit point for Nairobi, Maputo, Harare, or Lilongwe before proceeding to the RSA via land routes. However, due to increased government regulations, migrants are now compelled to select longer and more costly flight paths, such as those through Dubai or West African countries like Nigeria and Guinea.

The selection of routes and means of transportation utilized by irregular migrants is greatly influenced by intricate family and social networks, and ultimately negotiated and organized by smugglers. The migrants’ preferences for specific routes to reach RSA were dependent on various factors such as the choices made by smugglers (45.3%), recommendations from family networks (44%), the perception of the route being easier to travel (40.2%), the safety of the route (27.2%), and the cost-effectiveness and affordability of the route (20.6%). Informants highlighted during comprehensive interviews that the selection of migration routes relies on the brokers as well as the economic capabilities of the migrants. During in-depth interviews, individuals providing information stated that the selection of a migration route is influenced by both the brokers involved and the economic resources of the migrants. The journey associated with irregular migration involves several steps, such as organizing the required paperwork, obtaining counterfeit travel documents for air travel, or arranging transportation. Additionally, migrants must search for a secure land route and find ways to evade border checkpoints, either by paying bribes or concealing themselves. These complex tasks cannot be accomplished by individuals without the assistance of brokers.

The process of irregular migration entails arranging the necessary documents, obtaining counterfeit travel papers for flights, or organizing transportation, searching for secure land routes, and circumventing border checkpoints through either bribery or concealing migrants. Businesses cannot accomplish these tasks without the assistance of brokers. The pattern of irregular migration to RSA involves various methods of crossing international borders along the routes. A significant number of respondents (73.1%) managed to cross state borders by evading border controllers, while approximately 39.6% resorted to bribing border guards. In-depth interviews revealed that hiding in large cargo trucks or sealed containers, traveling across swampy areas and lakes using small boats, concealed travel through forests and at night, and brokers bribing border controls and police are among the mechanisms employed to cross state borders. Failure to successfully navigate these mechanisms can result in capture and prolonged detention, labor exploitation (such as working long hours on farms or shamba), deportation, or an increased demand for payment in order to secure release from prison.

The temporal distribution of Ethiopian migrants based on their year of migration experience reveals that the majority of migrants (67.1%) relocated to the Republic of South Africa (RSA) during the 2000s. Around 27.2% of them migrated to the RSA in the 1990s, while approximately 5.7% of respondents immigrated after 2010. According to the research participants, the Kembatas started joining international migration to the RSA in the early 1990s. These early migrants were primarily traders who had connections with the Hadiya people, neighboring communities, and received information about migration to South Africa from them. The main drivers behind this migration to the RSA were economic, stemming from land scarcity, and large family sizes. It is worth noting that the initial irregular migration from Kembata to the RSA was not solely motivated by economic factors. Both the research participants and existing literature highlight the role of political developments, such as regime changes in Ethiopia that facilitated mobility, as well as the introduction of liberal refugee laws by the RSA in the first half of the 1990s (Girmachew, 2019; Yordanos and Freeman, 2022; Table 3).

However, most research participants emphasized that Kembatas’ immigration to the RSA increased significantly in the early 2000s. This observation aligns with the existing literature on Kembata migration to the RSA. In addition to economic pressures, other factors like the influence of political networks, the culture of migration, and the spiritual aspects of migration have played a crucial role in driving the increased migration of Kembatas to the RSA (Dereje, 2022). During focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews, participants frequently highlighted the pivotal role played by Ambassador Tesfaye Habisso, who had a mixed Kembata and Hadiya ethnic background, and served as the Ethiopian ambassador to the RSA from 2002 to 2004. He acted as both an enabler and facilitator of Kembatas’ migration to the RSA. Other studies (Dereje, 2022; Yordanos and Freeman, 2022) have also noted that the Ambassador assisted in the immigration of some of his relatives, thereby contributing to the initiation of large-scale migration to the RSA. Consequently, the Ambassador is credited for establishing political networks of migration that benefited both Hadiyas and Kembatas. Research participants passionately mentioned this role of the ambassador, as he encouraged and raised awareness among people to move out and work. Additionally, they cited a quote from the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi’s parliamentary address: “Neb yetem zoro wede kefo new marun yemiametaw” (Wherever the bees go, they eventually bring honey back to the hive). Therefore, during his visit to Kembata, the Ambassador publicly urged young individuals to migrate, work, and eventually return home. The political instability caused by the 2000 elections in the region was another factor that prompted youth migration to the RSA. Furthermore, the remittances sent by migrants contributed to the growing influx of Kembatas into the RSA, as they helped bridge the gaps in both livelihood and income.

The trend of irregular migration to the Republic of South Africa (RSA) witnessed a decrease in the number of migrants between mid-2018 and 2020, following a peak in 2005 and 2006. This decline can be attributed to the government’s strict measures against local brokers, efforts to raise awareness, and the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted the implementation of stringent border closures by the states. However, as travel restrictions and border closures gradually diminished, coupled with economic crises caused by inflation and political instabilities, the inadequate attention from regional and federal governments in addressing the issue of unemployment, and the absence of any efforts to regulate this migration route, the number of irregular migrants to the RSA increased. In this regard, it should be noted that Prime Minister Abiy’s visit to the RSA in 2020 did not bring any significant changes in terms of regulating the nature of migrations, except for requesting the safety of Ethiopian immigrants facing rising xenophobic attacks. As highlighted by the participants in the focus group discussions (FGDs), the problem lies not in the lack of information about the risks involved, but rather in societal attitudes toward migration. Consequently, there is now a widespread aspiration among individuals to migrate, with even teenage students abandoning their education at grade 8 or 10 to join the migration process. This situation has been further exacerbated by fluctuating climatic conditions, leading to crop failures in recent years.

Brokers continue to play a prominent role in facilitating migration and remain the sole conduits for migrants to reach the RSA. The fees charged by these brokers for their services, including travel costs, have been increasing. In-depth interviews with migrant returnees revealed that the costs were relatively cheaper in the early stages, with pioneer migrants paying between 3,000 and 6,000 Ethiopian birr (equivalent to $487 to $974) for land routes, and between 18,000 and 24,000 birr (equivalent to $2,923 to $3,897) for air travel in the late 1990s. However, in recent times, migrants are paying between 500,000 and 600,000 birr (equivalent to $9,629 to $11,555) for land routes, and over 1 million birr (equivalent to $19,258) for air travel. Initially, migrants mostly covered their own travel costs or received assistance from extended family members. However, as time went on, mortgaging and selling household assets, particularly land, became a reliable means to cover these expenses. Pioneer migrants, mainly fathers, later sponsored the migration of their sons, brothers, and other extended family members. This pattern has recently been complemented, and even replaced, by a new source of funding through sponsorship from earlier migrants residing in the RSA. The payment methods have also varied over the decades. Earlier migrants paid in one lump sum in cash or mortgaged their land through long-term lease agreements. In contrast, later migrants paid in two installments, the first before embarking on their journey and the second upon arrival in the RSA. Additionally, migrants over the past decades have been subjected to multiple payments along the route.

The patterns of irregular migration to the RSA underwent certain changes in terms of the success rate of migrants in reaching their intended destination within the expected timeframe. According to the responses received, approximately 82.9% of the participants reported successfully reaching their destination despite facing legal barriers and enduring a perilous journey. Conversely, the remaining 17.1% faced failure, either being apprehended, imprisoned, and subsequently deported, or getting lost along the way. The duration of the migrants’ journeys varied depending on several factors, including their chosen mode of travel and the tightening of legal restrictions imposed by the destination countries. The survey findings revealed that, on average, it took around 2 months and 1 week (67.82 days) to reach the RSA. However, some individuals managed to arrive within a day or less when traveling by air. On the other hand, a significant portion of migrants endured an arduous journey lasting up to 3 years, primarily when using land routes. A majority of the migrants (93.5%) completed their journey within 6 months, with a substantial number (79%) managing to do so in 3 months or less. A fortunate few who traveled by land or air managed to reach their destination within a week (23.7%) or even within a day or half (12.2%). Moreover, a considerable percentage (72.9%) of these migrants arrived either on their planned date (37%) or within the expected timeframe (35.9%). Unfortunately, approximately 27.1% experienced significant delays in reaching their destinations compared to their originally anticipated dates.

It is worth noting that the migration patterns to RSA are not entirely permanent and involve instances of migrants returning to their home countries. Between 2015 and 2020, a significant proportion (40.7%) of migrants opted to return home, and this trend continued after 2020 (39.7%). The phenomenon of return migration commenced in the early 2000s, with approximately 0.6% of early migrants returning between 2000 and 2005. This rate gradually increased to 4.2% between 2006 and 2010, and further rose to 14.7% between 2011 and 2015. In in-depth interviews with migrant returnees, it was observed that a majority of those who successfully reached the RSA returned home after working and accumulating sufficient capital. This capital enabled them to start their own businesses in their home countries after a period of 10 to 20 years of labor. Consequently, most migrants began returning home after 2005, with the trend intensifying after 2015.

The primary motive for individuals to come back home stemmed from the fact that a majority of the survey participants (65.8%) felt the need to work and reside within their own country. Additionally, other factors contributing to their decision to return included visiting family members (11.7%), the lack of expected opportunities in the RSA (7.6%), personal illness (7%), fear of experiencing xenophobic attacks in the RSA (6%), and deportation (1.9%). Consequently, a significant proportion of these individuals (79.4%) had no intentions of returning to the RSA, while a small fraction (11.7%) had not yet determined their future place of residence, and a few (8.9%) still aspired to re-emigrate to the RSA. According to the participants, the primary motive behind returning home was connected to the initial factors that led to their migration, as well as the perceived success of their migration by both migrants and society. The foremost reason for migrants returning to their home country is the achievement of economic prosperity, which was the main driving force behind their initial emigration to the RSA. Therefore, a successful migrant returnee is not only someone who brings back financial wealth from the RSA to invest in their home country but also an individual who supports the emigration of their extended family members to the best of their ability, even if they return with no money.

Other factors that contribute to the temporary nature of migration are related to legal barriers and security concerns in the destination country. The legal status of the majority of Ethiopian emigrants in the RSA is as asylum seekers, which requires periodic renewal every 3 to 6 months. Still, many others lack any form of asylum documentation, as most migrant returnees reported the absence of any opportunities to obtain South African citizenship. Furthermore, these individuals lead precarious lives in the RSA, facing frequent xenophobic attacks. Some returnees described their survival as a “miracle or God’s plan,” and they also lack access to social services, among other reasons for their decision to return. Consequently, a majority of the participants had no intention of returning to the RSA.

The migration patterns from Ethiopia to the Republic of South Africa have experienced significant transformations throughout the years. The majority of Ethiopian individuals migrating to South Africa were individuals seeking asylum or refuge due to political instability though actual problem is economic difficulties in their home nation. The relatively stable political climate, strong economy, and higher wages in South Africa make it an appealing destination for Ethiopian migrants who are searching for improved economic prospects. Moreover, the existence of an established Ethiopian community in South Africa, providing social networks and support systems, acts as an attractive factor for potential migrants.

The routes chosen by Ethiopian migrants have also evolved. Traditionally, many migrants would undertake long and dangerous journeys through countries like Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi Mozambique, and Zimbabwe before reaching South Africa. A few numbers of migrants possess the necessary legal documents mainly passport, and most of them employed mixed transport system. The mode of travel and the routes to South Africa mainly determined and arranged by the smugglers. However, due to enhanced border controls and the risks associated with irregular migration, the number of irregular migrants has decreased, and some have sought safer routes, including air travel into South Africa.

It is important to acknowledge that migration from Ethiopia to South Africa comes with its challenges. Migrants often encounter language barriers, xenophobic attacks, and discrimination in their new country. Understanding the patterns of inter-state irregular migration from Ethiopia to South Africa is crucial for devising effective policies and interventions. Addressing the root causes that drive migration, improving border control mechanisms, and implementing inclusive integration strategies are key steps toward minimizing the risks and maximizing the benefits associated with this migration phenomenon. Facilitating regular migration channels, such as streamlining visa processes and exploring opportunities for legal and secure migration, can make it simpler for Ethiopian migrants to enter South Africa through official means. This can help reduce reliance on irregular migration and the associated risks. Ultimately, this can contribute to a more positive and inclusive migration experience for Ethiopian migrants in South Africa while maximizing the potential benefits for both the migrants and the host country.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in the research was provided by the participants.

Authors contributed to the initiation, data collection, analysis, and preparing the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adamson, F. B. (2006). Crossing borders: international migration and national security. Int. Secur. 31, 165–199. doi: 10.1162/isec.2006.31.1.165

Ahmad, A. (2015). “Since many of my friends were working in the restaurant”: the dual role of immigrants’ social networks in occupational attainment in the Finnish labour market. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 16, 965–985. doi: 10.1007/s12134-014-0397-6

Amelina, A., and Horvath, K. (2017). Sociology of migration. The Cambridge handbook of Sociology: Core areas in sociology and the development of the discipline 1, 455–464. doi: 10.1017/9781316418376.046

Anggoro, T. (2019). Identification of push factor, pull factor, and negative information concerning to migration decision.(evidence from West Nusa Tenggara). Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 8, 138–144.

Asmelash, H., and Litchfield, J. (2019). Changing patterns of migration and remittances in Ethiopia, 2014–2018. Mig. Out Pover. 59, 1–59.

Assefa, A., Seid, N., and Tadele, F. (2017). Migration and forced labour: An analysis on Ethiopian workers. Addis Ababa: ILO. Ilopubs@ Ilo. Org.

Awumbila, M. (2017). Drivers of migration and urbanization in Africa: key trends and issues. Int. Migr. 7, 1–9.

Bakewell, O., and Sturridge, C. (2021). Extreme risk makes the journey feasible: decision-making amongst migrants in the horn of africa. Soc. Inclu. 9, 186–195. doi: 10.17645/si.v9i1.3653

Bircan, T., Purkayastha, D., Ahmad-yar, A. W., Lotter, K., Iakono, C. D., Göler, D., et al. (2020). Gaps in migration research. Review of migration theories and the quality and compatibility of migration data on the national and international level. Hum MingBird paper, august, 1–104. Available at: http://www.hummingbird-h2020.eu.

Bisrat, W. (2014). International migration and its effects on socio-economic Wellbieng of migrant sending households: Evidence from Erob woreda, Eastern Zone, Tigray Regional State [Masters Thesis]. Mekelle University.

Blumenstock, J., Chi, G., and Tan, X. (2021). Migration and the value of social networks. JEL Classification. 94, 1–96.

Blumenstock, J., and Tan, X. (2016). Social networks and migration: Theory and evidence from Rwanda.

Borojo, P. G. (2020). An empirical study on irregular migration in Ethiopia: policy perspective. Public Policy and Admin. Res. 10, 1–14. doi: 10.7176/ppar/10-3-01

Bufalini, A. (2019). Global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration. Int. J. Refugee Law 30, 774–816. doi: 10.1093/ijrl/eez009

Carling, J., and Collins, F. (2018). Aspiration, desire and drivers of migration. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 44, 909–926. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384134

Casarico, A., Facchini, G., and Frattini, T. (2015). Illegal immigration: policy perspectives and challenges. Econ. Stud. 61, 673–700. doi: 10.1093/cesifo/ifv004

Castles, S. (2018). Social transformation and human mobility: reflections on the past, present and future of migration. J. Intercult. Stud. 39, 238–251. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2018.1444351

Castles, S., de Haas, H., and Miller, M.J. (2014). The age of migration:International population movements in the modern world (Fifth Edition). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Côté, R. R., Jensen, J. E., Roth, L. M., and Way, S. M. (2015). The effects of gendered social capital on U.S. migration: a comparison of four Latin American countries. Demography 52, 989–1015. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0396-z

Crush, J., and Tevera, D. (2010). Migration and social cohesion in South Africa. African Centre for Migration & Society, University of the Witwatersrand, Witwatersrand.

Czaika, M., and Reinprecht, C. (2020). “Drivers of migration: a synthesis of knowledge.” The IMI Working Papers Series, No. 163, 1–45.

de Haas, H. (2008). Irregular migration from West Africa to the Maghreb and the European Union: An overview of recent trends (Vol. 32). Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

de Haas, H. (2021). A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework. Journal CMS 9:8. doi: 10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4

de Haas, H., Castles, S., and Miller, M. J. (2020). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world. 6th Edn. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Dekker, R., and Engbersen, G. (2014). How social media transform migrant networks and facilitate migration. Global Netw. 14, 401–418. doi: 10.1111/glob.12040

Dennison, J. (2022). Re-thinking the drivers of regular and irregular migration: evidence from the MENA region. Comp. Migr. Stud. 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s40878-022-00296-y

Dereje, F. (2022). Beyond economics. Zanj: J. Critical Global South Stud. 5, 35–58. doi: 10.13169/zanjglobsoutstud.5.1.0005

Dibeh, G., Fakih, A., and Marrouch, W. (2018). Labor market and institutional drivers of youth irregular migration in the Middle East and North Africa region. J. Ind. Relat. 61, 225–251. doi: 10.1177/0022185618788085

Echeverría, G. (2020). Steps towards a systemic theory of irregular migration.In: Towards a Systemic Theory of Irregular Migration. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham.

Etling, A., Backeberg, L., and Tholen, J. (2018). The political dimension of young people’s migration intentions: evidence from the Arab Mediterranean region. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1485093

European Union (2018). International migration drivers: a quantitative assessment of the structural factors shaping migration. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg.

Fekadu, A., Deshingkar, P., and Ayalew, T. (2019). Brokers, migrants and the state: Berri Kefach ‘door openers’ in Ethiopian clandestine migration to South Africa. Migrating out of Poverty 56, 1–35.

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2020). Introduction: re-centring the south in studies of migration. Migration and Society: Advan. Res. 3, 1–18. doi: 10.3167/arms.2020.030102

Flahaux, M. L., and de Haas, H. (2016). African migration: trends, patterns, drivers. Comp. Migr. Stud. 4, 1–25. doi: 10.1186/s40878-015-0015-6

Frouws, B., and Horwood, C. (2017). Smuggled south: An updated overview of mixed migration from the horn of Africa to southern Africa with specific focus on protections, risks, human smuggling and trafficking. Horn of Africa and Yemen, Nairobi.

Girmachew, A. (2014). The impact of migration and remittances on home communities in Ethiopia [doctoral dissertation]. The University of Adelaide.

Girmachew, A. (2019). Migration patterns and emigrants’ transnational activities: comparative findings from two migrant origin areas in Ethiopia. Comp. Migr. Stud. 7, 1–28. doi: 10.1186/s40878-018-0107-1

Girmachew, A. (2021). Once primarily an origin for refugees, Ethiopia experiences evolving migration patterns. Migration Policy Institute (MPI).

Grüne, A. F. A., and Adele, A. F. (2017). To What Extent Does The New Economics of Labour Migration Theory (NELM) Explain Refugee Remittances? A Case Study of the Cause of Migration and Remittances Sent by Somalis in Finland. 1–117.

Habte, H. (2015). Socio-economic impacts of migration of Ethiopians to the South Africa and its implications for Ethio-RSA relations: The case of Kembata-Tembaro-Hadiya zones[masters thesis]. Addis Ababa University.

Habteyes, D. (2016). The socio-economic consequences of illegal migration: The case of returnees from Saudi-Arabia in west Shoa zone of Oromia National Regional State[masters thesis]. Addis Ababa University.

Henok, Y., Seid, M., Marcon, B., and Birhanu, N. (2017). “Causes and consequences of irregular migration in bale zone, oromia regional state, south eastern ethiopia” in About Migration: 7 Researches of 5 Ethiopian Universities on the Root Causes of Irregular Migration. ed. A. Stocchiero 3, 47–57.

Hochleithner, S. (2018). Theories of migration in and from rural sub-Saharan Africa: Review and critique of current literature ICLD Working Paper, No. 14. 1-41. Lee, Everett S. (1965). Theory Mig. Demogra. 3, 47–57.

Horváth, I. (2008). The culture of migration of the rural Romanian youth. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 34, 771–786. doi: 10.1080/13691830802106036

Horwood, C., and Forin, R. (2019). Everyone’s prey: Kidnapping and extortionate detention in mixed migration.Mixed migration briefing paper 2019. Mixed Migration Centre. Geneva.

Horwood, C., and Frouws, B. (Eds.). (2021). Mixed migration review 2021. Highlights. Interviews. Essays. Data. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Mixed-Migration-Review-2021.pdf

Ibrahim, H., al Sharif, F. Z., Satish, K. P., Hassen, L., and Nair, S. C. (2019). Should I stay or should I go now? The impact of “pull” factors on physician decisions to remain in a destination country. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 34, e1909–e1920. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2819

Idemudia, E., and Klaus, B. (2020). Psychosocial experiences of African migrants in six European countries (Vol. 81). Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-48347-0.

IMF (2016). Sub-Saharan African migration: patterns and spillovers. In Sub-Saharan African Migration. doi: 10.5089/9781475546668.062

IOM . (2019). Migration governance indicators. A global perspective. PUB2019/004/EL). IOM Retrieved from https://publications. iom. int/system/files/pdf/mgi_a_global_perspective. pdf.

IOM . (2021). World Migration Report 2022. In International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva. Available at: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022

Kane, A., and Leedy, T. (2013). Introduction: African patterns of migration in a global era: new perspectives. African migrations: patterns and perspectives, 1–16. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16gh6wd.4

Kelemework, T., Zenawi, G., Tsehaye, W., Awet, H., and Kelil, D. (2017). “Causes and Consequences of Irregular Migration in Tigray, Ethiopia,” in About Migration: 7 Researches of 5 Ethiopian Universities on the Root Causes of Irregular Migration, ed. S. A. Tigray , Ethiopia. (Addis Ababa: Italian Agency for Development Cooperation).

Khalid, B., and Urbański, M. (2021). Approaches to understanding migration: a Mult-country analysis of the push and pull migration trend. Econ. Soc. 14, 242–267. doi: 10.14254/2071-789X.2021/14-4/14

Kinfe, A. (2019). All or nothing: The costs of migration from the horn of Africa–evidence from Ethiopia. Africa: Roaming Africa: Migration, Resilience and Social Protection, 37.

King, R. (2012). Theories and typologies of migration: an overview and a primer. Willy Brandt Series of Working Papers in Int. Migration and Ethnic Relations 3, 1–43.

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Delhi: New Age International.