- 1Department of Management, Kinshasa School of Public Health, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo

- 2African Centre for Migration and Society, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been the subject of several armed conflicts for more than two decades, causing the displacement of millions of Congolese in and outside the country and impacting on their mental health and wellbeing. Mental healthcare interventions are a vital component for the displaced to holistically integrate into their new communities. This policy brief draws from a systematic review of various laws and policies as well as stakeholders' analysis to address the mental health issues of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the DRC. In addition, we examine data from 32 interviews with various stakeholders at the national level and in 4 provinces of the DRC (Kasai Central, Tanganyika, South Kivu and Ituri). The findings show that while the DRC has committed to progressive policies and conventions the implementation of these policies and conventions, however, remains insufficient. There are also limited local and international stakeholders that provide forms of psychosocial support to IDPs and, effectively address mental health challenges in context. In addition, the provision of such care is limited by the scarcity of specialized and skilled staffs. These findings point to the need to strengthen mental health system governance. This should include scaling up of the integration of mental healthcare at the operational level, the training of community health workers in the screening of mental health issues and the sensitization of the IDPs and the host population to help them change their perception of mental ill-health.

1 Introduction

This policy brief brings together an examination of existing legislation that addresses health, mental health and internally displaced persons (IDPs) with findings from interviews with stakeholders working within the context of mental health.

In what follows we start by providing an overview to the background and context of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with a focus on the impact of sustained armed conflict on the mental health of IDPs. In doing so we also review the current policies and interventions in place to address mental health challenges. From the key findings we provide recommendations that are intended to guide stakeholders -government, United Nations (UN) agencies, local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs)- to take necessary and tailored actions in order to strengthen their responses to mental health support and alleviate mental health issues among IDPs.

1.1 The DRC context and population displacement

The DRC is the second largest country in Africa with an area of 2 345 408 km2. The DRC shares its borders with nine neighboring countries. Movement across the borders by choice (for work, education, family etc.) and forced due to the protracted violence and armed conflict that has crippled the country for more than 30 years is both regular and frequent. The fact that many people cross informally taking advantage of the largely porous borders reflects the mobility, relationships and connections across the region. However, it also means that the activities of armed groups and of the illicit movement of natural resources and goods are frequent (Schlindwein, 2020).

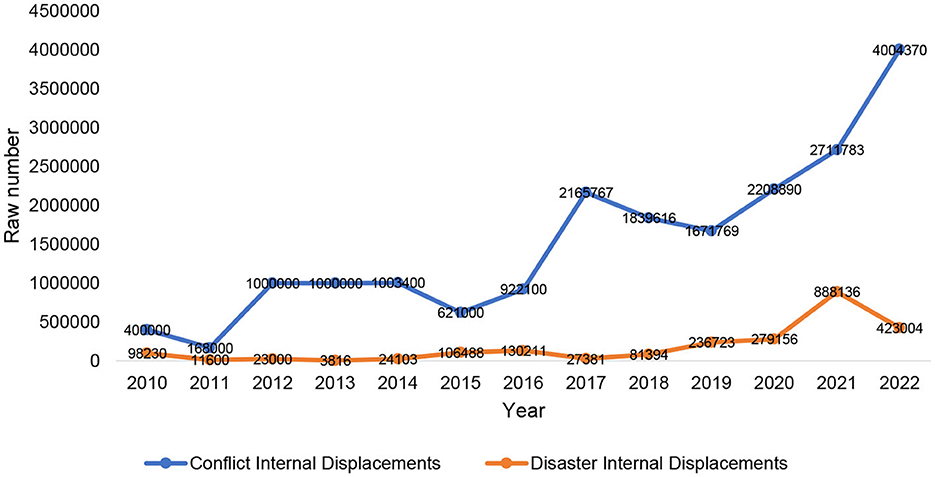

The decades of conflicts across the DRC have been fuelled by geopolitical and economical tensions with neighboring countries, primarily Rwanda and Uganda. The activism of armed elements and military operations have caused massive displacement of populations outside of the country (refugees) as well as within the country (internally displaced persons or IDPs). As shown in Figure 1, from 2010 to 2022, the number of IDPs have increased 8.8 times (from 498,230 in 2010 to 4,427,374 in 2022). This increase is explained by the escalation of armed conflicts in the east of the country with the M23 rebellion in North Kivu as well as the attacks by the Islamist group ADF-NALU from neighboring Uganda. Overall, in June 2023, the number of IDPs in the DRC has been estimated to be over 6 million; among the highest figures in the world (IDMC, 2023; UNHCR, 2023b). Most displacements were recorded in the eastern provinces of North Kivu (2,334,813), South Kivu (1,530,631) and Ituri (1,754,650). The inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika have also caused the displacement of 350,958 IDPs. Nearly 20,000 IDPs remain in the Kasai region and other provinces near Kinshasa (UNHCR, 2023a).

Figure 1. Trends of internal displacement from 2010 to 2022 in the DRC. Source: IDMC (https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo).

1.2 IDPs and mental illness risk

Research shows that the rate of mental health conditions in conflict zones is more than double that of the general population (Charlson et al., 2019). Evidence also suggests that the negative impacts of conflict on mental health can be passed down through generations (Yehuda and Lehrner, 2018) and with psychological, familial, social, cultural and neurobiological transgenerational effects (Sangalang and Vang, 2017; Bezo and Maggi, 2018).1 There are many possible reasons for why IDPs are at higher risk of developing mental health disorders. Mental illnesses among IDPs can result from multiple, often intersecting factors including direct exposure to the violence and destruction of war like (e.g., physical assault, the destruction of one's home, the disappearance or death of loved ones) and the stressful social and material conditions such as poverty, malnutrition, the destruction of social network or unemployment (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010; Rofo et al., 2023). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety disorder are recorded as highly prevalent after displacement and armed conflicts (Carpiniello, 2023). However, it is important to note that the definition as well of use of the diagnosis of PTSD are contested and therefore data reporting high prevalence requires a cautious interpretation (Tay, 2022). Originating from the West and the identification of traumatic symptoms amongst soldiers returning from the First World War, PTSD has since been used to diagnose forms of trauma experienced across a diverse range of contexts and countries. However, there is continuous debate in terms of its applicability cross-culturally and where and how it should be used as a diagnostic tool (Banerjee, 2015). Moreover, the screening of specific populations for such disorders is subjective due to the possible presence of other traumatic experiences such as early life trauma and the accumulation of other life events (Frissa et al., 2016) as well as the assumptions which guide initial screenings. Increasingly, studies indicate the need for a broader lens in understanding trauma and PTSD especially in terms of diverse and divergent contexts and where conflict and violence is enduring – therefore leaving no space for “post-trauma” (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010; Palmary, 2016; Ellis et al., 2019; Walker and Vearey, 2022).

In fact, exposure to armed conflict does not inevitably lead to mental illnesses and nor do mental illnesses only emerge during time of violence and conflict. Yet it is evident that the forms of exposure (either directly or indirectly), the types of exposure (e.g., human rights violations, sexual and gender-based violence, health threats, and witnessing atrocities), and the timing of exposure can all increase the risk of developing mental illness (Tay, 2022).

1.3 Understanding mental health amongst IDPs in the DRC

Within the context of the DRC, recent data about the type of mental illnesses are not available yet. One study conducted in 2010 revealed that half of the general population (50.1%) in the Eastern Congo, the most affected region by armed-conflict, reportedly met symptomatic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder, 25.9% reported suicidal ideation, and 16% reported attempted suicide at some point during their lives (Johnson et al., 2010).

1.4 The place of mental health in the context of the transition to Universal Health Coverage in the DRC

The response to mental health challenges in the DRC is marked by a health system where mental health service delivery is very limited. In fact, the country has < 60 neuropsychiatrists—one psychiatrist for more than six million inhabitants—of whom about 50 are concentrated in the capital, Kinshasa. Only three percent of primary care facilities integrate mental health services, and the country has only six hospitals specializing in mental health. There is no national budget allocated to the mental health national program (PNSM). That said, the PNSM has recently elaborated its National Strategic Plan for Mental Health; a promising step but will require more involvement of the Government to ensure its success. In addition, some forms of psychosocial support are offered by local organizations (such as the Panzi Foundation)2 and International Humanitarian and Development Organizations (such as OCHA and OIM), particularly in provinces affected by conflicts or in the post-conflict phase (OSAR, 2022).

Improving mental health and wellbeing is recognized as an essential component of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) (OMS, 2022) as set out as a key goal in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The DRC, like many other countries has recently committed to offer universal coverage of health care services to the entire population. The DRC aims to do this by 2030 (Ministere de la Santé Publique, 2018). This implies that all the Congolese population should receive all the quality and accessible care-including mental health care that meets their needs. However, the level of inclusion into the public health care system and universal health coverage planning is unclear. Therefore, based on the structural and systemic challenges described above, for the DRC reaching universal coverage will be impeded by the failure to improve the mental healthcare for all populations including those at heightened risks such as IDPs.

2 Method

This study draws from a review of various national laws and policies (including, decrees, orders, etc.) and international commitments of the DRC to address the mental health issues of IDPs. Publicly available documents (gray or published articles) were also reviewed. Supplementing this review, we conducted a series of interviews with various stakeholders to understand the significance of mental health in their interventions. A total of 32 semi-structured interviews, using a guideline with open questions, were conducted with one national and three provincial representatives of the National Program for Mental Health; one representative of the national and three provincial representatives of the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs; and 24 leaders of national and international NGOs in the capital city Kinshasa and four of the most affected provinces (Tanganyika, South Kivu, Kasai Central and Ituri). Questions were related to the role or missions of the organization in relation with IDPs and/or mental health; the existing texts relating to IDPs and mental health (laws, decrees, orders, etc.), and their applications on the field; some achievements in dealing with mental health among IDPs; and barriers to accessing mental health services by the IDPs. A thematic analysis was used to examine themes and identify patterns in respondents' answers to the various questions asked.

3 Findings

This section is structured in four, interrelated parts which successively develop: the legislative framework, the organization of the mental health response, stakeholders' intervention and barriers to accessing mental healthcare.

3.1 The legislative framework

All respondents pointed to the lack of specific legislation that addresses mental health provision and rights among IDPs in the DRC. Two key international and Continental conventions addressing the rights of IDPs were identified by some respondents: the International Humanitarian Law and the African Union's Kampala Convention. Respondents noted that both conventions have yet to be ratified by the DRC National Parliament as illustrated in the quote below:

“There are two laws lying around without being ratified: the International Humanitarian Law and the Kampala convention. These laws show the protection of internally displaced people in their country, and for refugees, how we can supervise people who are refugees outside their country. In other signatory countries, these laws have already been ratified, here with us it is still dragging on” (Stakeholder 21, Provincial Humanitarian Affairs).

The Kampala Convention builds upon the 1998 UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, the internationally recognized framework on internal displacement, which restates the principles of international human rights, humanitarian and refugee law applicable to IDPs. This includes the right to access healthcare and therefore is critical for ensuring the wellbeing of IDPs.

Other respondents pointed to the creation of the National Refugee Commission—(Commission Nationale pour les Réfugiés—CNR) to process asylum applications and ensure the protection of refugees as well as the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs. They saw these as positive indicators of solid political decisions for better management of migrants' issues in general but yet, still falling short of addressing mental health specifically:

“We already have the National Refugee Commission. There is also another major advance: the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs which now has divisions at the provincial level, which are responsible for these issues, especially in the provinces which have been affected by several humanitarian crises with movement of populations. All this shows this involvement of the government, the responsibility of the government in the implementation of all these international and national policies and treaties” (Stakeholder 12, International Agency).

The majority of the respondents mentioned both the ministerial decree creating the National Program for Mental Health as a positive move and also the absence of any legislation specific to mental health. As captured by one of the officials:

“There is a law that exists but it is more a general law on national health policy [Law No. 18/035 of December 13, 2018 establishing the fundamental principles relating to the organization of public health], specific laws on mental health need to be developed. And then two, you have to provide the resources, because in the budget law, the budgetary resources that are devoted to health are so minimal that certain components such as mental health only benefit from the salary coverage of agents” (Stakeholder 11, National level).

3.2 Review of existing legislation

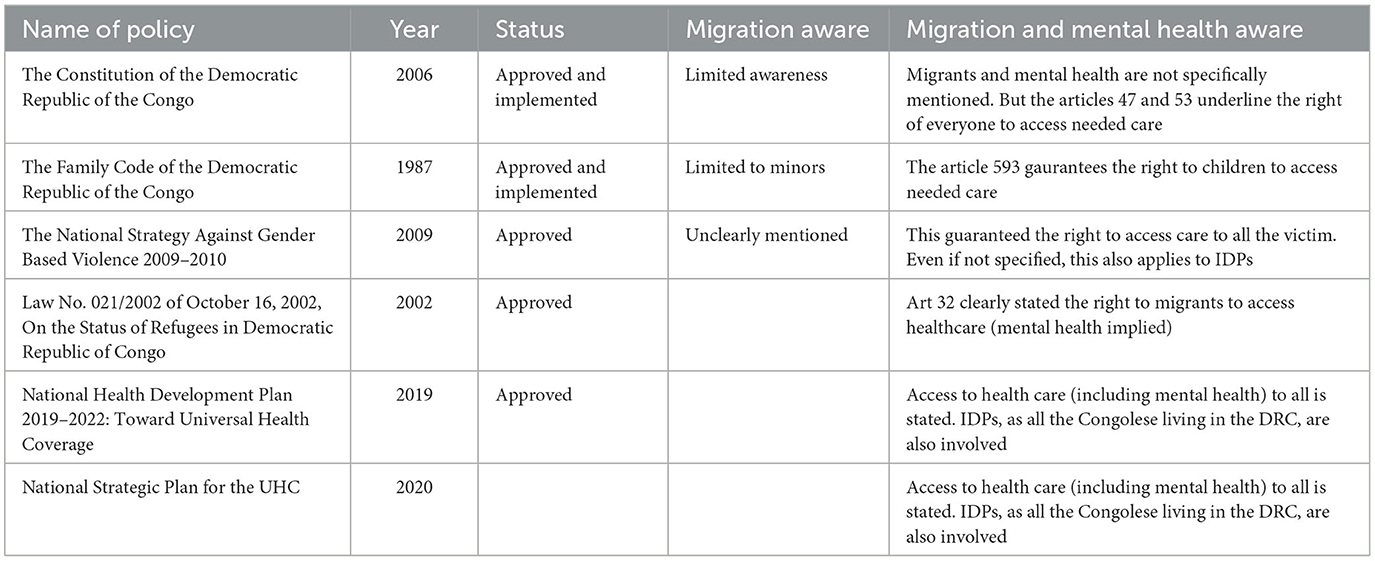

The findings from the interviews are supported by the review of DRC's legislative framework which, shows that the DRC has ratified several international conventions regarding the movement of populations (see Table 1). These include key conventions such as: the UNHCR (1951) and its 1967 Protocol; the 1969 Organization of African Unity Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa; the United Nations (1990) and the one directly dealing directly with IDPs, the United Nations (1990), Integral Human Development (2019).

However, despite the DRC's commitment to IDP governance agreements, and despite the high number of displaced people in the country, specific national legislation on IDPs' rights has not yet been adopted.

Unlike other migrants or refugees, IDPs do not cross any international border and therefore remain in their own country and under the protection of their government. They should therefore, enjoy the same rights as any other citizen while benefiting from specific protection due to the vulnerabilities posed by displacement. This is reflected in Article 30 of the country's Constitution, which provides that:

“Any person who is on the national territory has the right to move freely there, to fix his residence there, to leave it and to return there, under the conditions fixed by law. No Congolese should be expelled from the territory of the Republic, nor be forced into exile, nor be forced to live outside his habitual residence” (Article 30, DRC Constitution).

The Constitution also stipulates that the Congolese State is responsible for all legislation on refugees, expellees and displaced persons (Cabinet du Président de la République, 2011).

Other laws, although not specifically addressed to IDPs, have provisions protecting some of those most vulnerable including IDPs: the Family, the Children and the Penal Codes (as amended and supplemented by the law n°06/018 of July 20, 2006). The Congolese Criminal Code penalizes, for all the Congolese population, at its article 174 The Crimes of Rape, Minor Prostitution, Forced Prostitution, Sexual Slavery and Forced Marriage (Cabinet du Président de la République, 2006). The Child Protection Code (date) also contains a provision on displaced and refugee children, stipulating that they have the right to protection, support and humanitarian aid and that the State must ensure follow-up (Ministère de la Justice, 2010). However, laws addressing the specific case of IDPs' rights have yet to be promulgated.

The right to health is guaranteed in Article 47 of the Constitution and it is implied that this includes migrants who should have equal rights to health under the special provisions given for non-citizens. The Constitutional right to health is also affirmed in health legislation (such as the Public Health Law), polices and development plans although there is no specific mention of migrants or IDPs.

As for mental health for IDPs, there is no specific legislation on mental health, and legal provisions for mental health are not covered in other legislation. The DRC has ratified the international legal instruments concerning the provision of mental healthcare to those in need (United Nations, 2019), but there is yet no DRC law defining the rights and protection of people with mental illness or regulating the procedures of their admission into hospitals (On'okoko et al., 2010).

The DRC includes mental health as a component of the primary health care and its national mental health program, created in 2001 (Ministère de la Santé Publique RDC, 2001) and several national plans intend to integrate mental health provision at the operational level. However, this has not been implemented as < 5% of health facilities at the operational level have integrated the mental healthcare package. This is illustrated by a quote from one stakeholder:

“The institution that is responsible for this in the DRC is the national mental health program, set up by the government… We realized that, first of all, this program is not known, in most cases and it is not operational in certain regions… We really can't offer even 10% of the support” (Stakeholder 12, member of inter-cluster).

The Strategy for Strengthening the System of Health (SSSH) and its implementation plan, The National Health Development Plan 2019–2022 (NHDP): Toward Universal Coverage also mention a number of activities regarding mental health. The plan also recognizes the barriers toward achieving UHC including limited financing, lack of community participation, poorly demarcated and regulated health zones and insufficient resources and it is evident that commitments on mental health have not been implemented (Ministere de la Santé Publique, 2018) and no activities for IDPs or even the general population, have been implemented yet.

Overall, it emerges from our interviews and the review that support for mental illness among IDPs does not benefit from any specific legislation. There is an evident failure to prioritize the issue of mental health problems by the Congolese national authorities and therefore the current legislative framework fails to address the challenges of mental health both generally for all in the DRC and specifically, for IDPs.

4 Stakeholders' Interventions

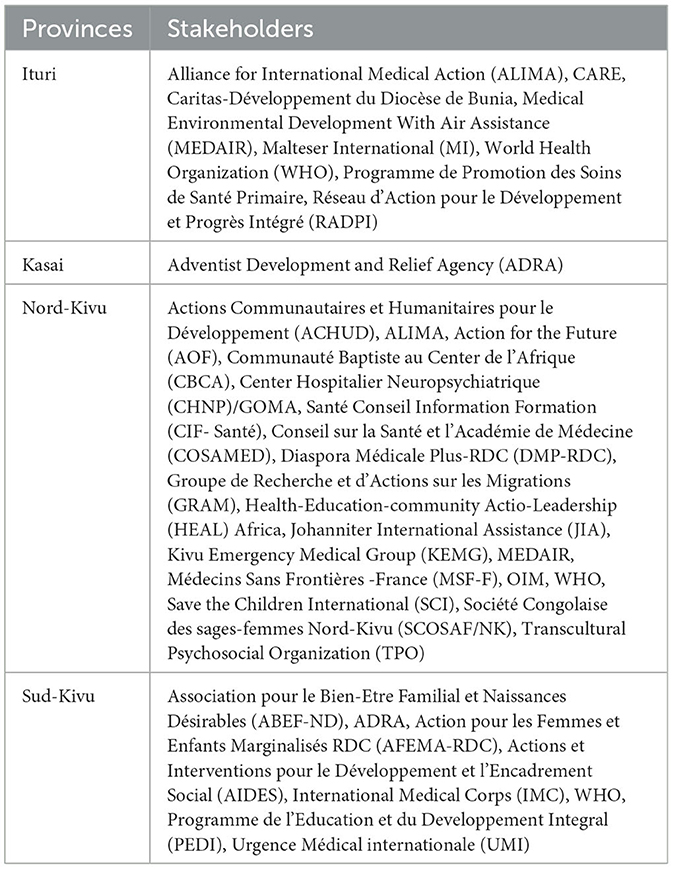

There is myriad of stakeholders (Governmental, Non-Governmental, UN agencies, international organizations, civil society and Faith-based Organization) helping IDPs in various areas (housing, nutrition, health, education, protection) either independently or under a coordinated cluster with other organizations sharing the same mission. While it is difficult to identify the exact focus of all the organizations and clusters very few were identified or recognized to have mental healthcare in their agenda.

The interventions from the Government take place through the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs which is responsible for coordinating the entire humanitarian response. There is also the aforementioned Humanitarian Affairs Committee. Additionally, there are other ministries like the Ministry of Social affairs, Gender, Health and Justice that have also been mentioned to have the interventions targeting migrants in general. However, this intervention seems to be, in the opinion of the majority of respondents, very limited and does not always include mental health. There are some exceptions to this in the Eastern part of the country where some efforts, from all stakeholders including the national government, have been made to provide psychosocial care to the survivors of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) as detailed by the following interviewees:

We work with different ministries (humanitarian, Justice, social affairs, etc.), health care providers, law enforcement officers, SGBV survivors, community leaders, etc. The government is not involved enough, it does not provide enough resources to combat mental health problems (Stakeholder 1, member of health cluster).

“In agreement with the government in its policy to combat GBV, the actors are organized in a health sub-cluster for the fight against GBV. In this sub-cluster, the actors share information on the response, we act in the management and prevention of this gender-based violence” (Stakeholder 14).

An effort is being made to extend mental health care to the entire population through the policy of integrating mental health into the primary health care package. This care should therefore be offered at the operational level. However, as reported by respondents, < 5% of health districts have the human resources capable of offering this care. No specific budget line has been allocated for these activities as the following quote demonstrates:

The simplest reason is that we do not have specialists trained in mental health, we do not have appropriate structures to offer quality mental health care, we do not also have resources available to do so such as in literature because the consequences can be such that the person even develops dementia (Stakeholder 12).

According to our review of published documents, stakeholders' interventions are brought together in different clusters including: health, WASH (water, hygiene and sanitation), protection, shelter, camp coordination and camp management (CCCM), education, nutrition and food security. All these clusters are supposed to work in synergy and brought together in a structure called Inter-Cluster, an Inter-Agency Standing Committee coordination mechanism under the co-leadership of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The health cluster comprises 158 international NGOs, 58 national NGOs, 82 UN representatives, 6 with Ministry of Humanitarian affairs, 8 donors, and 5 Observers (see the Table 2 with key stakeholders members of health cluster by provinces). The stakeholders' priorities areas include the fight against excess morbidity and excess mortality linked to lack of access to basic health care, secondary health care, sexual and reproductive health care, complications of malnutrition and various outbreaks epidemics of measles, cholera and malaria in the context of an already very fragile health system (OCHA, 2021, 2023a). In their report on their response to humanitarian problems for the second trimester of 2023, this cluster recognized that mental health has not benefited from enough activities and none (0%) of the 14,000 migrants in needs were reached during that period (OCHA, 2023b).

Some respondents however reported activities that were recently conducted. These included: the integration of mental health care in 51 of the 519 health zones in mostly four provinces Nord-Kivu, Sud-Kivu, Ituri and Tanganyika; capacity building in mental health care of health providers throughout the province of Tanganyika in eight of the 11 health zones; the harmonization of mental health guidelines in 2021 among all the stakeholders providing mental healthcare; and capacity building of health care providers (clinical psychologists, physicians and nurses) from seven health zones in Ituri province (Bunia, Rwampara, Nizi, Bambu, Nyakunde, Lita and Aru).

However, most respondents acknowledged that the integration of mental health activities is recent and very limited as the following quote illustrates.

“The integration of mental health activities is recent; it was somewhat neglected. We currently have at least one meeting per month. We try to mobilize the actors in the field and ensure coordination. We participated in the harmonization of mental health guidelines during the workshop organized in Goma in October 2021…” (Stakeholder 15, member of health cluster).

4.1 Barriers to accessing mental healthcare

From the interviews and documents reviews, the following barriers were identified:

4.1.1 Scarcity of specialized and skilled staff

Most respondents highlighted the fact that psychiatrists and other needed skilled staffs are lacking across the country and that this is unequal provision across the country. For example, respondents from Kasai Central, Ituri and Tanganyika reported no skilled human resources while those from South Kivu have the availability of such staff in some health facilities most notably SOSAME (Soins de Santé Mentale or mental health care facility) regional center and Panzi Foundation mostly for victims of sexual violence. This unrequal situation can be illustrated by the following quotes:

“Here, in the province of Ituri, there is no hospital that can take care of cases of mental illness. Only some NGOs provide some supports” (Stakeholder 18, local NGO).

“In reality here in Tanganyika, I have never observed an actor on the ground providing mental healthcare” (Stakeholder 21, provincial level).

“We have integrated mental health services into some district level mostly in North and South Kivu” (Stakeholder 11, National level).

However, referring to some key stakeholders' plans (CCCM in particular), financial resources have been specifically allocated to mental health challenges among displaced populations (CCCM Cluster, 2023). The training of health workers has also been organized as some respondents reported:

“After the workshop, we organized training for providers at DPS Bunia on Mental Health in December 2021. Six health zones (Bunia, Rwampara, Nizi, Bambu, Nyakunde and Lita) took part in this training: clinical psychologists, doctors, nurses and some NGOs invited on the management of cases of mental illnesses. We have also organized training on the management of mental illnesses in Aru” (Stakeholder 15, UN agency).

Although this may appear promising in theory, this has arguably very limited impact given the potential scale of the problem and the need for mental health care for an IDP population of over 6 million, not counting the host families of the displaced.

Apart from these NGOs, we must also highlight the role of community organizations, particularly community relays, in the promotion of mental health. This is still an experience limited to certain health zones:

“We have already integrated mental health care in the Walungu health zone by training care providers (doctors, nurses, community relays, etc.), we help them to refer complicated cases to specialized structures. We have integrated listening and support units into the health zone structures. We are in the process of expanding our activities in other health zones” (Stakeholder 5).

4.1.2 Perceived lack of interest by stakeholders

Overall, mental health care has not been prioritized and considered as an urgent need by stakeholders, although respondents indicated that there has been a recent growing interest demonstrated in the section above by the training of some health providers. However, this does is not yet enough to cover the IDPs' needs. However, psychosocial support to victims of sexual violence needs to be highlighted among the effort to combat mental health issues among this population.

“The integration of mental health activities is recent; it was somewhat neglected… We try to mobilize the actors in the field and ensure coordination” (Stakeholder 15, UN agency).

“The Congolese people in general are abandoned to their sad fate, because if you go to SOSAME you will see that the number that is there is really minimal compared to the mental health problem that there is in Bukavu” (Stakeholder 06, local NGO).

4.1.3 The drain of trained health care workers

To explain the scarcity of skilled human resources in the DRC, respondents noted that some healthcare workers trained to work in mental health are recruited by NGOs during specific projects, and they then tend to leave right after the end of those projects.

“You train people from the health zones for mental health care, and these people develop skills but because they are underpaid, the NGOs come and recruit them and take them to them as experts and they will work for them. It is also important to improve the remuneration of service providers to help them stay” (Stakeholder 11, National level).

The inability to sustain the achievements of the projects after they have finished and to hold onto the trained health care providers who understand the context and needs of the IDP population is therefore a major concern. This undermines any efforts to build a stronger mental health work force and in turn, limits access to mental healthcare for those in need.

4.1.4 Perception of mental illness origin and treatment

Findings from the interviews with experts also highlighted the significance of how mental illnesses are perceived by the majority of the population, even some health providers themselves, as mystical or due to curse. This is an issue that has also been identified in a number of studies (Ventevogel et al., 2013; Mutombo Tshibamba et al., 2019; Wiel and Slegh, 2022), As a result, many turn to traditional or religious healers rather than seeking help via bio-medical health facilities: “In the DRC we have a problem of often considering mental health as witchcraft” (Stakeholder 06, Province level). For stakeholders this perception means that those facing mental health challenges are often blamed and held responsible which also impacts on whether treatment is sought.

For example, those affected by mental illness are often accused of wrong-doing in the past and it is assumed that they deserve their curse. Therefore, effort to seek care is undermined by the assumed source of mental health. This also contributes to suspicion and doubt about the effectiveness of the “modern” (Western) medicine in treatment mental illness (Echeverri et al., 2018). For those who do not/cannot seek care this can lead to a worsening of issues, particularly for women:

For the mental health problem, it is often the mothers (women) who are traumatized. There are those who flee the war, even forgetting their children and they develop disorders in relation to the unfortunate events they have experienced. They are neglected, they run away from them, they take them for sorcerers because they are troubled, and these are problems we encounter in the sites (Stakeholder 24, local NGO).

5 Actionable recommendations

As the DRC moves toward achieving UHC the findings of this review suggest that there is a need to implement measures aiming to promote and to improve mental health and wellbeing as an essential component. This should include scaling up comprehensive and integrated services for the prevention as well as treatment for people with mental disorders and other mental health conditions (United Nations, 2019). Drawing from suggestions from respondents in what follows we set out some recommend key steps to address which could pave a way toward ensuring the UHC is achieved with support for mental health at the center of its commitments.

5.1 Strengthen focus and leadership of the government on mental health responses

One of the main recommendations by respondents to ensure a holistic solution to mental health issues among IDPs is that the Government should invest more, in terms of increasing budget allocation and providing necessary resources to the Humanitarian Affairs and the National Program for Mental Health. Government leadership should also reinforce collaboration between the aforementioned institutions through the elaboration of a joint plan to engage other stakeholders. This much needed plan is of great importance as all the stakeholders should align to guarantee the rationalization of their interventions.

5.2 Scale-up the integration of mental healthcare at the operational level

The aforementioned effort to integrate mental health at the operational level- which has begun with 51 health zones- is a guarantee on early screening of mental health problems at the district level. This could also help IDPs, as well as the host population, to receive the needed care in facilities close to their habitation. If district level plans are effectively rolled out, these can include IDPs into planning so that parallel ad hoc programs by NGOs are not ineffectively duplicating services. This implies that stakeholders should invest more training for district health workers in screening, treating or referring mental health problems. They should also elaborate a supply plan for all the medications and needed materials.

5.3 Train the communities in screening for mental health issues

The involvement of community health workers in the promotion of mental health within the community is a positive experience that needs to be expanded. In fact, the DRC already benefits from a vast network of community health workers that are involved in the promotion, prevention and even curative health provision. Training such workforce could be particularly useful in the screening of IDPs that require mental healthcare. There are guidelines that have shown their effectiveness for such purpose (WHO, 2005; Echeverri et al., 2018).

5.4 Sensitize IDPs and their host population

Interventions aiming at raising the awareness to reduce mental health stigma have been reportedly shown to be effective in countries like South Africa (Kakuma et al., 2010). In the DRC, stakeholders should invest in the sensitization of the IDPs and host populations to help provide more education on mental health issues and prevent stigmatization of those affected. A joint behavior change communication plan that also use the network of community health workers can help for that purpose.

6 Conclusions

This policy brief raises the alarm on the mental health problem among IDPs that is often neglected but has harmful effects on their wellbeing. It has highlighted the major challenges that currently limit an effective mental health response to IDPs in DRC. Insufficient resources, a failure to prioritize mental health issues among stakeholders, and the stigmatization of mental health challenges require more attention in order to improve responses that are also critical to the DRC achieving the goal of UHC. Effective solutions, as suggested by respondents are dependent on the involvement and investment of all stakeholders and especially the Government to take mental health seriously and center mental healthcare in a “health for all” approach.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Kinshasa School of Public Health, Kinshasa, DR Congo (Approval number: ESP/CE/20B/2021). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PM: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Software, Visualization. GL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Software, Supervision, Visualization. RW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Economic and Social Research Council (Grant Ref: ES/T004479/1).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1273937/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^There is a growing focus area in research and clinical work in psychology and related disciplines that explores how and why trauma impacts through generations.

2. ^The Panzi foundation ia a well-funded organization founded by Dr. Denis Mukwege, a Nobel Peace Prize winner.

References

Banerjee, B. (2015). Background, controversies, and misuse of post traumatic stress disorder diagnostic criteria: a review. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 6, 400–406.

Bezo, B., and Maggi, S. (2018). Intergenerational perceptions of mass trauma's impact on physical health and well-being. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 10, 87–94. doi: 10.1037/tra0000284

Cabinet du Président de la République (2006). Loi n° 06/018 du 20 juillet 2006 modifiant et complétant le Décret du 30 janvier 1940 portant Code pénal congolais. Journal Officiel de la République Démocratique du Congo.

Cabinet du Président de la République (2011). Constitution de La République Démocratique Du Congo. Journal Officiel de La République Démocratique Du Congo 2006, 89.

Carpiniello, B. (2023). The mental health costs of armed conflicts—a review of systematic reviews conducted on refugees, asylum-seekers and people living in war zones. Int. J. Environm. Res. Public Health 20, 2840. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20042840

CCCM Cluster (2023). Stratégie nationale du cluster de coordination et gestion des sites (CCCM) pour la République Démocratique du Congo 2023-2024. Kinshasa. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/strategienationale-du-cluster-de-coordination-et-gestion-des-sites-cccmpour-la-republique-democratique-du-congo-rdc-2023-2024

Charlson, F., van Ommeren, M., Flaxman, A., Cornett, J., Whiteford, H., and Saxena, S. (2019). New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 394, 240–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1

Echeverri, C., Le Roy, J., Worku, B., and Ventevogel, P. (2018). Mental health capacity building in refugee primary health care settings in sub-saharan africa: impact, challenges and gaps. Global Mental Health 5, 19. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2018.19

Ellis, B. H., Winer, J. P., Murray, K., and Barrett, C. (2019). “Understanding the Mental Health of Refugees: Trauma, Stress, and the Cultural Context,” in The Massachusetts General Hospital Textbook on Diversity and Cultural Sensitivity in Mental Health. Humana, Cham: Current Clinical Psychiatry. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-20174-6_13

Frissa, S., Hatch, S., Fear, N. T., Dorrington, S., Goodwin, L., and Hotopf, M. (2016). Challenges in the retrospective assessment of trauma: comparing a checklist approach to a single item trauma experience screening question. BMC Psychiat. 16, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0720-1

Johnson, K., Scott, J., Rughita, B., Kisielewski, M., Asher, J., Ong, R., et al. (2010). Association of sexual violence and human rights violations with physical and mental health in territories of the eastern democratic Republic of the Congo. JAMA 304, 553–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1086

Kakuma, R., Kleintjes, S., Lund, C., Drew, N., Green, A., and Flisher, A. J. (2010). Mental health stigma: what is being done to raise awareness and reduce stigma in South Africa? African J. Psychiat. (South Africa) 13, 116–24. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v13i2.54357

Miller, K. E., and Rasmussen, A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Soc. Sci. Med. 70, 7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029

Ministère de la Justice (2010). Loi N° 09/001 Du 10 Janvier 2009 Portant Protection de l'enfant. Journal Officiel de La République Démocratique Du Congo 7.

Ministere de la Santé Publique (2018). Plan National de Développement Sanitaire recadré pour la période 2019-2022?: Vers la couverture sanitaire universelle. Available online at: https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/sites/gff_new/files/documents/DRC_Investment_Case_FR.pdf

Ministère de la Santé Publique RDC (2001). ARRÊTÉ MINISTÉRIEL 1250 / CAB / MIN / S / AJ / 008 / 2001 du 9 décembre 2001 portant création d ' un programme national de santé mentale. (Ministère de la Santé publique). Journal Officiel de La République Démocratique Du Congo. Available online at: https://www.leganet.cd/Legislation/DroitPublic/SANTE/AM.1250.008.09.12.2001.htm

Mutombo Tshibamba, J., Tshifita, M. K., Nkuanga, F. M., and Kasongo, N. M. (2019). Perception of mental illness in the city of Lubumbashi (The Case of the Inhabitants of the Commune of Kenya, Lubumbashi, DR Congo). East Afr. Scholars Multidisc. Bull. 4413, 114–17.

OCHA (2023a). République Démocratique Du Congo: Présence Opérationnelle−3W (Qui Fait Quoi Où). Kinshasa: RDC.

OMS (2022). “30e Conférence Sanitaire Panaméricaine,” in Politique Pour L'amélioration De La Santé Mentale.

On'okoko, M. O., Jenkins, R., Ma Miezi, S. M., Andjafono, D., and Mushidi, I. M. (2010). Mental health in the democratic republic of congo: a post-crisis country challenge. Int. Psychiat. 7, 41–43. doi: 10.1192/S1749367600005737

Palmary, I. (2016). “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” in The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Rofo, S., Gelyana, L., Moramarco, S., Alhanabadi, L. H., Basa, F. B., Dellagiulia, A., et al. (2023). Prevalence and risk factors of posttraumatic stress symptoms among internally displaced christian couples in Erbil, Iraq. Front. Public Health 11, 2003. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1129031

Sangalang, C. C., and Vang, C. (2017). Intergenerational trauma in refugee families: a systematic review. J. Immig. Minority Health 19, 745–54. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0499-7

Tay, A. K. (2022). The mental health needs of displaced people exposed to armed conflict. Lancet Public Health 7, e398–99. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00088-3

UNHCR (1951). “Text of the 1951 convention relating to the status of refugees,” in Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/media/convention-and-protocol-relating-status-refugees

UNHCR (2023a). Internally Displaced in the DRC 2023. Available online at: https://data.unhcr.org/ar/country/cod#idp (accessed June 08, 2023).

United Nations (1990). International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families. UN Treaty Collection. doi: 10.1017/9781912961139.016

United Nations (2019). “Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage,” in Universal Health Coverage: Moving Together to Build a Healthier World. Available online at: https://www.un.org/pga/73/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/07/FINAL-draft-UHC-Political-Declaration.pdf

Ventevogel, P., Jordans, M., Reis, R., and De Jong, J. (2013). Madness or sadness? local concepts of mental illness in four conflict-affected african communities. Conflict Health 7, 1. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-3

Walker, R., and Vearey, J. (2022). ‘Let's manage the stressor today' exploring the mental health response to forced migrants in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int. J. Migrat. Health Social Care 19, 1. doi: 10.1108/IJMHSC-11-2021-0103

WHO (2005). “Mental health policy and service guidance packages: mental health policy, plans and programmes,” in Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Packages, 1–104.

Wiel, A. T., and Slegh, H. (2022). Practices of congolese mental health and psychosocial support providers: a qualitative study on challenges and obstacles. Res. Square 2022, 1–15. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2152158/v1

Keywords: internally displaced populations, mental health, DR Congo, migration, policy

Citation: Mutombo PBB, Lobukulu GL and Walker R (2024) Mental healthcare among displaced Congolese: policy and stakeholders' analysis. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1273937. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1273937

Received: 07 August 2023; Accepted: 11 December 2023;

Published: 05 January 2024.

Edited by:

Marcia Vera Espinoza, Queen Margaret University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jasmin Lilian Diab, Lebanese American University, LebanonJohn Quattrochi, Georgetown University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Mutombo, Lobukulu and Walker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paulin Beya Wa Bitadi Mutombo, cGF1bGluLm11dG9tYm9AdW5pa2luLmFjLmNk

Paulin Beya Wa Bitadi Mutombo

Paulin Beya Wa Bitadi Mutombo Genese Lolimo Lobukulu

Genese Lolimo Lobukulu Rebecca Walker

Rebecca Walker