- Institute for Global Health and Development, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Migration through managed routes such as spousal and work visas has been conceptualized as being a pragmatic choice driven by the needs of families rather than individuals. In contrast, studies of refugee integration post-migration have tended to analyse integration processes through the perspective of the individual rather than through a family lens. Drawing from data collection using a social connections mapping tool methodology with recently reunited refugee families supported by a third sector integration service in the UK, in this paper the author makes a valuable contribution to addressing this theoretical gap. The author explores the ambivalent ways in which family relationships, and the care that flows between family members, influence emotional, and practical aspects of refugees' integration. Empirically the inclusion of accounts from people occupying different positions within their families, including from children, adds depth to our understanding of integration from a refugee perspective. Conceptually, the paper argues that a focus on familial relationships of care re-positions refugees not as passive recipients of care, but active and agentive subjects who offer care to others. The paper ends with a call for integration to be understood in a family way that fully encompasses the opportunities and limitations offered by familial care.

1. Introduction

Across the UK, Europe, and the Global North, controlling and, in some cases, preventing spontaneous arrivals by people seeking international protection has become a major policy preoccupation. Responses to refugee mobilities range from the construction of physical walls to blockade borders (Garcia, 2019), to co-operation agreements with third countries to prevent departures regardless of the humanitarian consequences (Sajjad, 2022). In the UK context, immigration legislation has restricted refugees' legal and socio-economic rights (Mulvey, 2015), creating a policy environment that is purposefully hostile to migrants, most especially those entering the country through irregular routes to seek international protection (Griffiths and Yeo, 2021). People who overcome these hurdles and are recognized as refugees can face a new set of challenges as they try to settle in the new country context (Strang et al., 2018) including structural constraints that shape their experiences of integration (Phillimore, 2020).

Integration policies are nominally designed to assist refugees to “re-build their lives from the day they arrive” in their countries of settlement (Scottish Government, 2018, p. 10). Political discourse around integration is strongly linked to concerns around social cohesion, with social and cultural changes occasioned by migration perceived as leading to division and discord (Casey, 2016). This discourse has been critiqued as being rooted in a post-colonial mindset, that assumes people are integrating into what is in fact an imaginary culturally and ethnically homogenous national community (Schinkel, 2013). Scholars have insisted on the importance of understanding integration as a multi-dimensional process, rather than a pre-determined set of outcomes. However, policy and practice interventions can still rely on gathering evidence of integration through measures such as levels of employment and education (Penninx, 2019). As a result, refugees can find their progress judged against metrics that fail to consider the fluid, non-linear nature of their lives and changing circumstances.

This paper does not, as Schinkel (2013) recommends, jettison the concept of integration entirely. Instead, in line with scholarship that recognizes and addresses its critiques (Spencer and Charsley, 2021), my aim is to expand its conceptual and empirical reach through exploring the role of the interrelated concepts of care and family in integration. Care, as a site of “intimate connection” (Caduff, 2019, p. 788) can facilitate integration (Käkelä et al., 2023). The obligations and complexities of organizing and providing transnational family care where one or more family members are living overseas have been well-documented (Baldassar, 2007; Näre, 2020). Yet, despite the family's central position as “a template for a safe social relations” (Caduff, 2019, p. 794), where care is present in integration discourse, it is usually understood as professionalized care received by refugees—through interventions taking place in health or social care, provided by the third sector or during research itself (Vera Espinoza et al., 2023). Intra-familial acts of care given and received by refugees in countries of settlement remain largely invisible.

In a similar way, the role of the family in the integration experiences of forced migrants is rarely explored in detail. While the same critique could be leveled across the field of migration studies, research with people migrating for work or family reasons has increasingly, though not uniformly, adopted a family-eye view. Cooke (2008) underlines the importance of understanding all migratory projects “in a family way” (Cooke, 2008, p. 255). This approach conceives of migratory decisions as the result of a process of weighing up costs and benefits for the whole family, not just in relation to the individual family members who cross international borders. Family has been recognized as an effector of integration: one of a multitude of contextual factors that influence integration (Spencer and Charsley, 2016). Research with refugees living in London and Glasgow, two large cities in the UK, confirmed that family has “a unique saliency in human relationships” and should be a central component of future integration research and policymaking (Strang and Ager, 2010, p. 597). Yet, for people who cross borders to seek asylum, as opposed to through routes such as work and spousal visas, an understanding of individual and family mobilities as being migratory projects can be somewhat subsumed by insistence on the traumatic and forcible nature of their displacements (Marlowe, 2010). Relatively little is known about the concrete ways in which being part of a family, and the everyday care this involves, can affect refugees' experiences of integration.

To address this gap, this paper presents data drawn from qualitative research activities undertaken with recently reunited refugee families living in the UK. Data were gathered using a Social Connections Mapping Tool methodology with a sample of refugee families living in cities where people seeking asylum are housed by the UK government. Participants were drawn from a cohort of asylum route refugees accessing family-focused integration services and were recruited through specialist third sector project partners. To frame the findings from the study, I begin by exploring the nexus between family, migration and integration; then outline feminist conceptualizations of care and how these apply in a migratory context. Taking the moment of family reunion as a pivotal event around which past, present and future experiences and aspirations for care collide and coalesce, I draw out accounts from sponsors, arriving spouses, and children to build a multi-layered view of the meanings they ascribe to giving and receiving care. This illustrates the ways that age, sex and family position shape how care impacts upon integration. I end with a call for care within the family to be recognized as a site where refugees are agents, rather than recipients, of integration assistance, and for intra-familial care to be foregrounded in future integration research and policy.

1.1. Migration, integration, and the refugee family

Perceptions of the role played by the family in the integration are not static. The European Union's Family Reunification Directive accords rights to family members of EU workers because “family reunification helps to create sociocultural stability facilitating the integration of third country nationals in the Member State, which also serves to promote economic and social cohesion” (EU Council Directive 2003/86/EC). This was indeed the initial approach to family unification migration taken by European countries in the post-war period. Allowing workers coming from outside the European Economic Area (EEA), who were primarily men, to bring wives and children to join them was seen as a positive way to ensure their integration into society (Bonjour and Kraler, 2015). However, in recent years, family members' capacity to integrate, as judged by measures including language proficiency tests, has been used to justify policies that restrict family migration (Strik et al., 2013). Increasingly migrant families are situated as problematic social units where harmful cultural norms are perpetuated, and where integration can be halted or reversed (Grillo, 2008).

In the specific case of refugee families, similar contradictions dot the policy landscape. Being officially recognized as a family is a primary criterion that qualifies refugees for resettlement schemes that enable safe passage to receiving countries. In this reading of what it means to be a refugee, being part of a (nuclear) family denotes vulnerability and people at risk, whereas being single, especially for men, is an indicator that you may be a risk rather than someone who is deserving of care (Welfens and Bonjour, 2020). It is on this basis that families are prioritized for resettlement, displacing the goalposts of refugeehood enshrined in the 1951 Refugee Convention, and re-positioning asylum as a humanitarian gesture rather than a human right (Fassin, 2005). If family arrivals are nominally more welcome than single men, this does not denote an unconditional acceptance of family as a factor supporting integration. Interventions to support family integration can have as their starting point the notion that family relations that are “one of the main barriers toward successful integration into the local society” (Olwig, 2011, p. 191). Doubt is cast upon refugee parents' capacity to care for their children in line with prevailing cultural expectations (Kouta et al., 2022). Perceptions of refugee families as being in need of assistance not only justifies government interference in their family lives but, in contrasting local family norms to those of arriving refugees, reinforces the cultural identity of receiving countries (Bonjour and De Hart, 2013).

Evidence from research with migrants and refugees themselves confirms that family unity—or lack thereof—has an important effect on people's ability to settle into new environments (Bonjour and Kraler, 2015). The existence of trusted social bonds, including familial relationships, is fundamental to people's ability to build deeper connections with other people or services over time (Strang and Ager, 2010). Knowing that family members are living in situations of danger and precarity overseas can mean that people feel “less able to establish and sustain relationships” in the country of settlement (Pittaway et al., 2016, p. 414). However, if family ties can provide “strength and solace” (Lokot, 2018, p. 560), familial relationships can also be sites of obligation, and, in severe cases, of abuse and violence. Migration, and the separations it occasions, can affect family relationships (Näre, 2020). Evidence suggests that subsequent moments of reunion can be fraught with difficulty as family members come to terms with the effects of separation (Rousseau et al., 2004). Young people have reported various challenges within the home: conflict with parents who object to them adopting the new cultural norms, pressure from parents who see their children's success as the main aim of their migration and the need to navigate unfavorable material circumstances in the early days of settlement (McMichael et al., 2011). The enforced nuclearization of refugee families by immigration policies that narrowly define family as parents and their dependent children means that families themselves may still feel incomplete. Important extended family members including grandparents and adult siblings can be prevented from crossing borders to live with or visit families who have been granted settlement (Grillo, 2008; Wachter and Gulbas, 2018). This paper provides further evidence of both the joys and difficulties of rebuilding family relationships in the months after reunion, and by extension of the ways that family, in its opportunities and constraints, influences integration for people settling in the UK.

1.2. Perspectives on family care and its role in migration

Feminist perspectives that suggest that care, in its practical and emotional manifestations, is a “building block of society,” whose meanings and practices are rarely explored in detail (Innes and Scott, 2003, p. 5.1). In a wide range of social policy areas, manifestations of care are both neglected and ignored (Lynch et al., 2021). For example, while many social policies orientate toward “facilitating labor market participation for a range of socially excluded groups” (Innes and Scott, 2003, p. 3.1), this has been at the expense of policies that recognize and support the unpaid work of care and its contribution at micro (family) and macro (societal) levels (Yeates, 2011). Much of the physical and emotional labor of care is undertaken by women, either within familial structures or as employees in care industries. The relegation of care as an area of private rather than public concern is reflective of the ways in which women's experiences more broadly have traditionally been understood to lie outside the public, male sphere. This, Scuzzarello (2009, p. 66) argues, “depoliticizes highly political issues and retains structures of power that position women and care receivers outside the public realm.”

At the nexus between care and migration, this does not always mean that women are materially disadvantaged. Women who migrate to provide care elsewhere face fewer obstacles than men in obtaining visas and regularization in countries of settlement (Calavita, 2006). However, migrant women can then face the challenge of navigating between caring for others and organizing transnational care for their own family members (Bernhard et al., 2009). The often invisible labor of transnational care can include financial remittances (Bernhard et al., 2009), maintaining virtual contact by phone or internet (Baldassar, 2007), social remittances involving sharing of new social and cultural norms between countries (Lacroix et al., 2016), and organizing visits home (Baldassar, 2015). If the capacity to provide these multiple layers of care can be considered a form of “social capital” (Baldassar and Merla, 2013, p. 7) care can also elicit emotions of guilt and obligation (Baldassar, 2015). This is especially the case for women who, before, during and after migration, are potentially expected to be primary carers for children and for older family members, in proximity as well as transnationally. Similarly, the work of “homemaking” in the new country environment, a process that involves dual processes of adaptation to new environments and retention of customs, connections and identity, is inherently gendered with women undertaking much of its emotional and practical labor (Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2023). This is not to say that men are excluded from all caring responsibilities. As the family members who are most likely to depart first for potential countries of refuge, men may face a specific and administrative burden of care. This is discharged through navigating the bureaucratic systems that will allow them to obtain leave to remain for themselves and then send for family who remain overseas (Näre, 2020). Fulfilling this role, and the separations it entails, can have a significant impact on their spousal and parental relationships.

Less is known about the ways in which family care interacts with processes of integration once families are reunited in receiving countries. The UK's policy framework for understanding integration—the Indicators of Integration Framework—mentions care only briefly: three times in the context of formal care offered by others (social or health care) and twice regarding the need for childcare so that adult family members can engage in economic activity outside the home (Ndofor-Tah et al., 2019). In this way, to the extent that it is considered at all care is positioned as something provided through professional services external to refugees' own family units; and primarily in terms of the potential for care-giving to impede progress in other domains. While this paper does not seek to deny the ambivalent nature of care's impact on integration, the framework does not appear to recognize acts of intra-familial care, nor accord them any integrative value. Yet, for the men, women and children who took part in this study, such care was central to their experiences as they prepared for reunion, navigated its realities and imagined their family's future life. This paper seeks to fill this gap and, in line with feminist perspectives on care, render intra-familial care more visible as a factor affecting integration for all family members.

2. Materials and methods

The findings outlined in this article are drawn from a research project that used a mixed methods Social Connections Mapping Methodology to explore the role of social connections in integration, building upon previous studies in the UK (Strang and Quinn, 2019) and Iraq (Strang et al., 2020). The methodology comprises (a) workshops using visual mapping methods to invite adults to discuss whom they or members of their community would turn to in three hypothetical scenarios (see below) and (b) a quantitative social connections survey. Constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic led the team to conduct a series of additional semi-structured qualitative interviews in the period immediately after initial lockdown restrictions were lifted.

2.1. Sampling and limitations

The data outlined in this paper is drawn from the qualitative components of the methodology: 13 interviews conducted with adults and young people aged 12 and over living in Glasgow and Birmingham (13 families: 21 adults, 8 children); and eight social connections mapping workshops conducted in cities across the UK's four devolved nations (35 families: 61 adults). The choice of sites was determined by the places where the project's third sector partners were offering services to refugee families. This in turn reflects the location, at the time of the study, of the UK's principal dispersal areas—local authority areas where the UK government and its subcontractors allocate accommodation to people seeking asylum.1 In one site the mapping workshop with families was supplemented by a workshop with six Peer Educators, who were volunteers from a refugee background working with our third sector partner. All participants were, at the time of the research activities, accessing or supporting the work of a specialist family reunion integration service provided by two voluntary sector partner organizations. The service provided support both to the sponsor refugee—the person who had first come, usually alone, to claim asylum; and their arriving spouse and any dependent children, granted visas under the UK's refugee family reunion regulations.

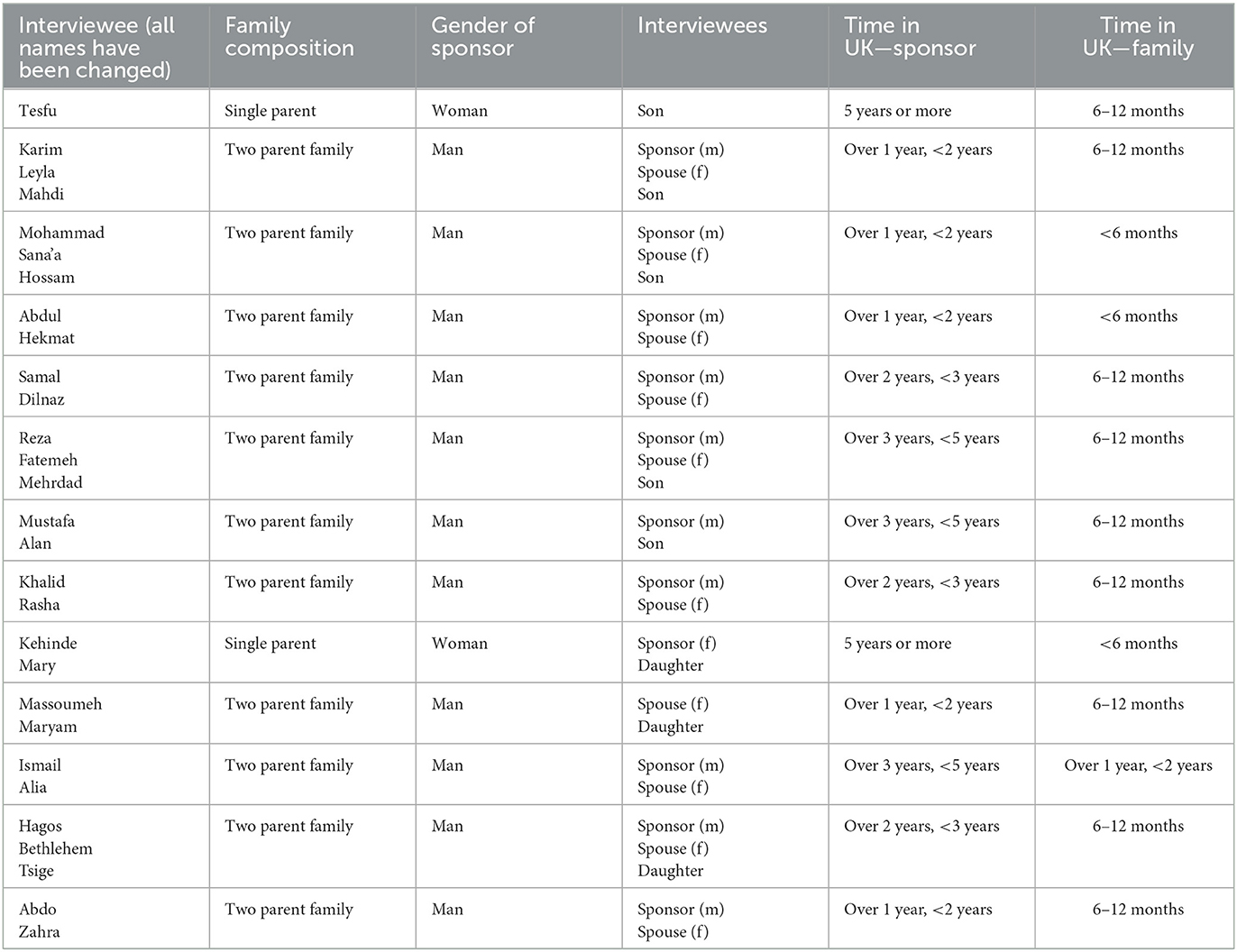

Demographic information for workshop participants, all of whom were adults, is outlined in Table 1; Table 2 summarizes the profiles of the families interviewed during remote interviews. All names have been changed and pseudonyms used throughout to preserve participant anonymity. Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Queen Margaret University Ethics Panel (REP 0190; REP 0222).

The cohort of research participants was drawn from the beneficiaries of a third sector-led refugee integration service offered to people who had qualified for family reunion under existing UK immigration rules. In allowing only reunion with spouses and dependent children aged under 18, these rules are heavily skewed toward the nuclear, heterosexual family. As a result, this paper focuses on the experiences of families constituting one or more biological parents reunited with one or more biological children and so cannot claim to represent the full range of experiences of diverse family groupings. The power dynamics inherent in research activities, and our profile as university researchers may have influenced answers given to us during workshops and interviews (Mackenzie et al., 2007). While the use of interpreters, translated information and a two-stage informed consent process mitigated this, participants may not have felt able to discuss all aspects of their experiences in the UK or may have felt obliged to present a positive image of their family life. Families living in areas, including in rural locations, not served by the urban sites included in the study and/or who had chosen not to accept the support offered by the integration service are not represented in this cohort. Finally, the remote interviews were conducted online and so researchers were unable to ensure that each family member could talk in a private space without their spouse or parents able to hear their accounts. As such, it is likely that negative experiences within the family were minimized or omitted.

2.2. Social connections mapping methodology

In mapping workshops, participants were presented with three scenarios and asked to discuss whom they would speak to or ask for help were they, or someone they knew, to face these hypothetical problems. The scenarios were explored sequentially: (a) having no hot water at home; (b) looking for a job; (c) a child being unhappy at school. They were designed to elicit responses covering the categories of social bonds (close relationships with people you trust), bridges (weaker relationships with people occupying different social spaces), and links (relationships with organs of the state). The questions were drawn from previous research conducted with displaced people (Strang et al., 2020), and adapted to the UK context in discussion with our third sector partners who advised on relevance to the refugee families who access their services. As participants spoke, researchers drew the connections onto visual maps, using lines to illustrate the ways in which one connection could lead to another, for example if the initial connection could not assist with the problem, whom might they recommend that the family contact. These maps and contemporaneous notes taken by the team comprised the dataset from this phase of the research.

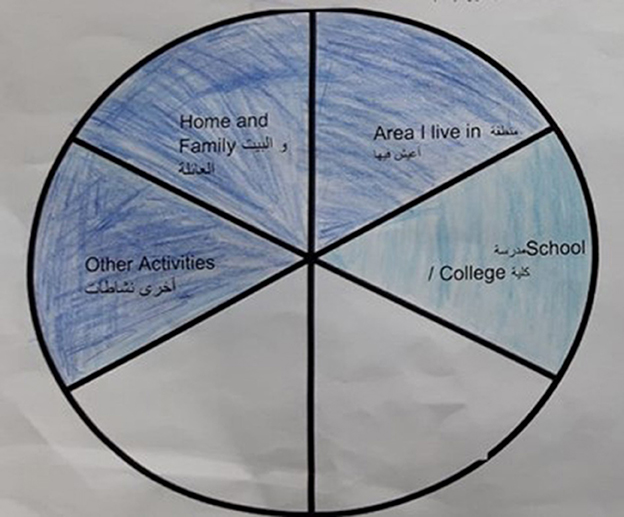

For interviews, the research team used a Wheel of Life visual tool2 to facilitate discussions. Paper copies of the wheel were posted, translated if required, to participants in advance. An amended version, and information in age-appropriate language, was provided for children. Participants were invited to shade the wheel before the interview to indicate how fulfilled they felt in each area of their life. The researchers had envisaged that people would fill each segment according their level of satisfaction in this area of their lives, with a fully shaded segment indicating high satisfaction. However, some interviewees chose instead to color code their wheels. In the wheel shown in Figure 1, Hossam explained that deep blue represented “excellent,” while the lighter blue was “less good.” Each interviewee was encouraged to share their rationale for their choices of shading. The wheel then served as a prompt to allow interviewees to begin the interview with the part of the lives they most wanted to discuss.

Family members were offered the opportunity to be interviewed separately, however space constraints in family homes meant that most children spoke to the team with at least one parent present in the room with them. For the nine families where both spouses took part in interviews, all interviews were conducted jointly with both spouses speaking in the same room either consecutively or together. All but two interviews were recorded and sent for professional transcription.

2.3. Analysis

Research notes and visual mapping diagrams were jointly reviewed after each workshop by the team. This produced a set of emerging codes, which were then used by the researchers to manually code the full set of diagrams and notes once this research phase was complete. Interview data were analyzed using an interpretive phenomenology approach (Matua and Van Der Wal, 2015). All transcripts or notes relating to each family were analyzed in turn, firstly by each individual researcher and then as a team. In this way, data gathered from each family was reviewed as a distinct phenomenon or case. After this initial analysis the team proceeded to a more traditional inductive coding phase. Each researcher manually coded an agreed sample of interview notes and transcripts. The team then met to compare their coding schemes. This informed the development of a joint coding scheme, which was then applied to the full dataset. Following this initial phase, the author undertook a subsequent round of analysis that focused on findings relevant to intra-familial care. This encompassed narratives relating both to experiences of caring about family—care understood to be a set of values and concerns; and caring for family—undertaking physical acts of care (Yeates, 2011). Relevant excerpts were extracted and analyzed using Dedoose software to inform the findings presented in this paper.

3. Results

While care was not the focus of the broader research project, acts of caring for and about family emerged strongly from our analysis as being central in participants' accounts of life in the UK and the social connections that they valued. In this family context, caring for included daily tasks like cooking, cleaning, and walking children to school. Caring about was expressed through the strong sense that family members were constantly “looking out for” each other (Yeates, 2011, p. 1,111) and, in the case of adult family members, taking decisions on housing, education and employment with the welfare of their dependants uppermost in their minds. I draw on the ethnographic work of Larsen (2018) to explore these aspects of intra-familial care across a temporal scheme encompassing the past (prior to family reunion), present (post reunion, at the time of the interviews), and aspirations for the future. Placing the moment of reunion as the pivotal event around which these time periods coalesce is a choice borne from the accounts of the families my colleagues and I spoke to. Our analysis confirmed that the moment of reunion was the culmination of many months if not years of planning and yearning, after which life shifted once more on its axis and began again. This gives voice to time's central role in integration and migration, confirming that time really is “of the essence” when seeking to explore and better understand integration as a process (Sheller, 2019).

3.1. Caring in the past

Caring in the past, defined for the purposes of this paper as the period prior to the moment when sponsors, spouses and children were finally able to reunite in the UK, was still vivid in the memories of many participants. Arranging, funding, and delegating transnational care is well-documented in literature on transnational family practices (Baldassar and Merla, 2013). The obligations involved in such care directly impacted on parents' decisions around other integration domains. One workshop participant explained that she had remained working for a company in the UK, despite evidence that she and other migrants were being discriminated against by the employer, for reasons relating to her family's welfare overseas:

“I needed to keep the job as I was paying for my children to come to the UK and for family back home.” (Alisha, sponsor and mother)

If the foundations of integration are rights and responsibilities (Ndofor-Tah et al., 2019), caring for family can impinge upon refugees' ability to demand that their rights are realized.

Sponsors' accounts confirmed that, above and beyond organizing transnational care, their decisions and actions in the UK were heavily influenced by considerations of how they planned to organize family care in future. These considerations were largely invisible from public view, but strongly shaped sponsors' accounts of the time prior to families' arrival. Mustafa explained that he had moved to a new city, despite strong social ties elsewhere, as he perceived that it offered better prospects for his arriving family members.

“I am always concerned about my family and the good quality of education for my children, so I decided to come to Glasgow.” (Mustafa, sponsor and father)

This was the case even where other cities or places offered opportunities for advancement in areas such as employment, because, as Mohammed explained, they were not suitable as places to raise a family:

“I went to London to search for a job because there is good opportunities there. And the rate of the hours—of working hours—is better than other cities. Yes, it's expensive, it's good for single people, but for family, I don't think that it's good, because it's very expensive and not easily to find the accommodation like that.” (Mohammed, sponsor and father)

Primrose, a workshop participant had left a full-time job to move from England to Wales. She decided to move when she heard news of her four daughters and knew that reunion was imminent. In moving, she was motivated by her feeling that Wales would be a better place to settle as a family. It is not then only the existence of family, or family-like connections in other areas that motivate internal migration (Stewart, 2011). Instead, decisions reflect the ways in which sponsors “think forward” about care from the moment that reunion becomes a possibility (Innes and Scott, 2003, p. 5.2). Moreover, decisions that may appear to negatively affect integration—for example, Primrose's decision to leave a stable job—can instead be understood as active steps toward a sustainable, family-focused future (Strang and Ager, 2010).

At an emotional level, care provided even in the more distant past continued to resonate in the present time. This was evident in Samal's account of his gratitude and love for his father. He became emotional when he spoke of his father and the care he had received from him.

“I always say that if there is a—there comes another Prophet after our Prophet it would be my dad because I think he's the greatest person. He did everything for us. […] he sacrificed all his life only for us just so that we have a good life to live, and now whenever I talk to him he cannot stay on the phone […] because he just starts to cry because he misses us so bad. I just wish that if possible 1 day I can go back to see them again.” (Samal, sponsor and father)

This mixture of gratitude for past care, and guilt around current separation illustrates the ways that migration can disrupt assumed contracts of care within families, whereby younger family members benefit from care as children and then can reciprocate by caring for parents in old age (Baldassar, 2015). Being unable to fulfill that contract can lead to feelings of guilt and shame. Giving and receiving care in the past then shaped emotions in the present, affecting lives across borders. Even for families reunited on paper, the restrictive way that the family is defined in migration legislation, and related practices of “bureaucratic bordering” (Näre, 2020) can leave families feeling incomplete (Wachter and Gulbas, 2018). This is the case even once they have successfully navigated the paperwork, waiting times and dangerous journeys involved in family reunion (BritishRedCross, 2020). These accounts remind us too of the difficulties of drawing definitive lines between past, present, and future when exploring migration and integration (Sheller, 2019).

3.2. Caring in the present

If the absence of beloved extended family members was still keenly felt for some families, their previous separation(s) from family members who were now living together in the same household also had echoes in the present, despite long-desired reunion having finally been achieved (Bernhard et al., 2009). Kehinde explained that caring for her teenage daughter in the present was rendered more difficult by the 9 long years when her daughter had been in the care of others.

“I keep telling her that there's some things that you have to do. You don't want to do this job, but you can't just say you don't want to do everything. You just have to learn how to do it. […] But I assume because I wasn't around to look after her, to know you know so, so many things that I trying to make her adapt to now […] it's really hard. So, I know we'll get there.”(Kehinde, sponsor and mother)

Sana'a had remained with her children, assisted in caring for them by her own mother, while her husband navigated through the asylum process. Although they were now living together as a family, she felt that he was unwilling to fully share childcaring responsibilities, ascribing this to differences in attitudes between men and women. While in the same interview she spoke at length of her joy at being reunited with him, this was a source of frustration.

“The day before yesterday, I was having headache, I was telling their father to take them to the market. He said, “No, no, I cannot control them in the street.” I said, “Why? I was controlling them for 2 years there alone and sleeping and wake up and everything. […] You see, the men, they don't want to take responsibility like us.” (Sana'a, arriving spouse and mother)

Other parents expressed more everyday difficulties in parenting their children. Reza and Fatemeh, interviewed separately from their only son, expressed concern that he was spending increasing amounts of time in his room playing on a computer game. They explained that:

“We don't see him much, sometimes he just comes for dinner or lunch and again back to his room, so it's, kind of, everybody's problem now.” (Reza, sponsor and father)

As a result, these parents were considering seeking therapeutic family support. On the other hand, when interviewed separately to his parents, their son Mehrdad, explained that for him the computer game was a positive way to build and maintain social contacts with friends from home. These intergenerational discussions and dynamics speak to the complexities of building and maintaining positive relationships of care and of the ways that care can constrain as well as empower those who receive it, particularly children (Larsen, 2018). They are also far from unique to families with experience of forced migration (Livingstone and Byrne, 2018).

Other “dark sides of care” (Pratesi, 2017, chapter 5) that emerged were the ways in which parents' obligations to provide care for children constrained them in domains of integration such as work, education and building social networks. Kehinde had found herself unable to embark upon paid work despite her strong desire to become economically self-sufficient and support herself and her daughters:

“They [employability support programme] were like, “You want to work, but all your time you have, so which time do you want to have for your children?” Which hours you want to use to want to work?” I say, “I use the weekend,” they say, “No, you can't use the weekend, so you have to stay with your children for that weekend you know.” […] because I want to fit in, I want to do something, I want to be able to provide for my children.” (Kehinde, sponsor and mother)

It was not just caring for children that constrained participants. Mary, a workshop participant, had arrived to join her husband, and both were of retirement age. But her husband had significant health problems. At the outset of the workshop, she explained that caring for him meant that she rarely left their house. In integration terms, this also meant that she could not rely on him for advice on settling in their local area. Instead, she took many of her questions to a nearby neighbor who luckily was willing to assist.

Sponsors often reflected on the sense of responsibility that they had for their family's integration as the person who had been longest in the UK and knew systems better than more recently arrived spouses and children.

“Actually the time was very tight, so I had only 15 min' break and at that time, so it's only—I was getting a chance to meet my classmates only but not other people. The reason basically is because I was feeding my kids, buying some food from restaurants, so I was running after college to my family.” (Hagos, sponsor and father)

“I am thinking of joining the Sudanese Community in Glasgow, but my time is very limited, being busy with my children, sometimes helping with the kids when my wife is going out.” (Mustafa, sponsor and father)

It is perhaps notable that for both men quoted above, care impinged upon but did not fully prevent other activities. They were, it seemed, engaged in care on more of a part-time basis—“helping when my wife is out”—than some of the mothers who raised similar problems. The obligations of care were, it appeared, more of a potential impediment to integration for women than for men (Innes and Scott, 2003).

Yet if care has its dark sides, acts of care contain integrative potential also. In line with Ryan (2018), parents were often able to build social connections outside the home when engaging in daily childcare activities, for example walking children to school and nursery or supervising them as they played outside. “Taking our kids to the park and having the chance to play there” (Bethlehem, arriving spouse and mother) was an activity that enabled all members of the family—men, women and children—to build social networks with others. The resulting ties contributed to families' sense of belonging and safety in their local areas. Families also recounted being able to share care outside their immediate families and spoke of mutual networks of support whereby they provided care to others' children, enabling all concerned to “grow our kids together” (Bethlehem, arriving spouse and mother). Care was a priority and had a value in and of itself, even when its realities impacted on other areas of life.

“My kids are the most important thing in my life so I just try my best to make them happy and overcome those difficulties that we face.” (Samal, sponsor and father)

This commitment to family was echoed by the children we interviewed. Despite some of the difficulties described by their parents, the predominant emotion expressed by the children we interviewed was the joy of being back together with their families:

“I'm so happy to see my mum and my sisters after a very long time. Like, so I get to know them more than before.” (Mary, arriving child)

“So, the most thing that makes me happy is we all, [our] family's reunited.” (Tsige, arriving child)

And if adults were sometimes frustrated by the ways that caring responsibilities prevented them from moving forward in other domains, some children saw things differently. Tesfu's mother had been able to find work outside the home, however he reflected that before COVID-19 lockdowns, this had meant that he, his sibling and his mother “rarely saw one another.” He was pleased when lockdown meant his mother was able to spend more time with them, and went on to explain that being with his family had been enough even to overcome some of the constraints and boredoms of the COVID-19 lockdown:

“Surviving lockdown was not important, it had its difficult moments but it was just a temporary moment the whole world went through. The important thing is that me and my family are safe and were safe throughout lockdown. And the most important thing ever is the bond I share with my family. There is a lot of love.” (Tesfu, arriving child)

The dark sides of care are a strong reminder not to romanticize the giving or receiving of care, nor to assume that all families were happy and nurturing outside the confines of the interview space. However, care as narrated to us by refugee families had on occasion been enough to overcome the practical and emotional obstacles placed in families' roads by circumstances and world events.

3.3. Caring in the future

If the obligations and opportunities offered by intrafamilial care shaped families' current experiences of integration, these were also prime considerations when families spoke of their future aspirations. These were not framed around individual goals but were formulated with the whole family's future wellbeing and success in mind. Caring about children was expressed by parents' strongly felt wish that, in future, their children “be better than us” (Hagos, sponsor and father). The route to this, in parents' accounts and those of several children, was education. Caring about education and their children's progress within the UK system was fundamental to parents' aspirations for the future. This was also expressed through parents' willingness to advocate for the best possible education provision for their children, even where they were reluctant to independently challenge systems barriers in other domains (Baillot et al., 2023).

Care included a recognition of and support for shifting notions around the role of women and girls within and outside the family home. Adults from two families discussed the importance of helping their partners and children adapt to what they perceived to be more equal, less strictly defined gender roles in the receiving society. Khalid and Rasha, interviewed jointly, were one of the couples who talked in these terms. Having progressed in her English through online classes during lockdown, Rasha's goal for the future was now to “work and help myself” (Rasha, arriving spouse and mother). However, Khalid explained that he had told her many times that to achieve this, she would have to reduce the time she spent cooking for the family. This highlights the ways in which care is part of a wider, family-wide calculation whereby caring duties must be balanced with people's desire to achieve individual goals in other domains:

“I sometimes have thinking because the life here is different. It's not like our country especially she started studying and if she starts working full time, I told her this system [cooking fresh dishes] will not work. So especially sometimes some food it takes about 2–3 h to prepare, it's a long time.” (Khalid, sponsor and father)

Khalid's explicit contrasting of cultural norms in his country and those in the UK was echoed by Sana'a. Her daughter was trying to find a place in an all-girls school in the UK as she did not feel comfortable in a mixed-sex environment. Whilst sympathetic to her daughter's wishes, her mother felt that she would sooner or later have to adapt to prevailing cultural norms in the UK in this regard. As such, she was managing her child's expectations as best she could:

“I feel like she was enforcing us to put her in girls' school […] I said, if it is she will not go to this school, she will go to another one. It's OK, it will be good experience, it will be hard at the beginning, but she'll get used to […] Because like just think, if she will keep going in the girls' school, OK, in university, what she will do?” (Sana'a, arriving spouse and mother)

For Sana'a, caring for her children was not limited to physical acts of childcare but included supporting them to understand and adapt to the prevailing norms in the new country context. Similarly, when workshop participants in Cardiff were presented with a hypothetical scenario around their child being unhappy at school, they felt that this matter did not immediately require care from professionals. Instead, they spoke of their role as parents in helping their children to build “resilience” that would enable them to cope with hardships in the future. Their view was that “once they show their character, the bullying will stop” (Peer Educator workshop participant).

Family members' active role in these moments of cultural and emotional adaptation contradict framings of family as a place where parents and their children may “actively decide not to integrate” (Casey, 2016, p. 103). Instead, caring for one's own family was directly related to nurturing ways in which the whole family could move from being recipients of help to actively contributing to the receiving society.

“now I just try to do everything in correct way to get the better life for my family […] sometimes I hope my kids do better in the school and they can in the future help this country and like to repay all this help to this country.” (Khalid, sponsor and father)

This transformation is enabled through acts and values of care—in simple terms, the care parents and spouses gave to their family members in the present was a means to help those family members to adapt and become successful in the future. There is evidence that shouldering this burden of expectation can put pressure on young people whose parents frame familial success in this way (McMichael et al., 2011). Deeper exploration of children's own feelings about familial aspirations and how they navigate these over time would be ripe topics for further research.

4. Discussion

The accounts of families who took part in this study confirm that the emotional and practical impacts of care given and received flow across time and space in ways that confirm the fluidity not just of care but of integration itself (Tefera, 2021). Foregrounding refugees' experiences of care and caring remind us too that refugee families share commonalities with all families in the ways that the obligations and logistics of care can constrain life on one hand but provide deep emotional connection on the other (Innes and Scott, 2003). This is true also for the ways that care can have a differential impact across the family. While men did discuss care, and—for sponsors in the study—felt the weight of their caring duties—it appeared to be women whose activities outside the home were most circumscribed by caring commitments. Again, this is not confined to people with experiences of forced migration—in many contexts it is women who, in their role as wives and mothers, shoulder the greatest burden of the obligations and duties of care (Innes and Scott, 2003; Baldassar, 2007; Bernhard et al., 2009; Scuzzarello, 2009).

Of course, caring for and caring about one's family members (Yeates, 2011) may be rendered more difficult by the specific circumstances of people's forced migrations to seek protection from harm. The moment of family reunion is pivotal precisely because it is often the culmination of months if not years when families have navigated separation, bureaucratic processes and sometimes extreme physical danger (BritishRedCross, 2020). Organizing and managing care across borders during separation is frequently an invisible labor being undertaken by refugee sponsors even before families arrive (Bernhard et al., 2009) confirming that a transnational understanding of care is required to fully encompass refugees' experiences of settlement. Even whilst physically separated, people's choices, conditioned as they are within the structural constraints of systems of immigration control and welfare (Phillimore, 2020) are made not with only their individual futures in mind but with the needs, circumstances, and future welfare of their families as a prime consideration. This may involve making choices that could from the outside appear to undermine their own integration (Strang and Ager, 2010). Failing to take family into account when working with people who initially present as single adults is to render invisible the familial context which conditions many of their choices and decisions.

Once families arrive, providing care is a time intensive activity. While superficially it may seem that this care impedes progress across other domains, accounts from families themselves clearly indicate that giving and receiving care has value in and of itself. Children's accounts, which are often omitted from integration research, do indicate that those who receive care in the present feel safe and at home. This complements previous findings to the ways in which receiving care from professionals in the third sector can have a positive impact on integration experiences (Käkelä et al., 2023). Importantly, a focus on care given by refugees, rather than care that they receive, repositions them as active subjects who are shaping the world around them rather than passive recipients of help. In this way, bringing intra-familial acts of care from the private realm to the public plays a role in pivoting away from images of helplessness and victimhood and the negative impact that these can have in the real world (Pupavac, 2008; Wroe, 2018).

The present though remains intimately connected to the past. Previous separations from arriving family members, and ongoing separation from extended family can temper joy at reunion with emotions of sadness and guilt (Baldassar, 2015). Shifting family roles can bring frustration as well as happiness. Seen from a child's eye view, acts of integration such as gaining paid employment outside the home can reduce the quantity or quality of care they receive from parents. Women may remain tied to obligations of care and struggle more than men to build lives outside the home. Care certainly has its dark sides (Pratesi, 2017) and should not be over-romanticized (Caduff, 2019).

Refugees' aspirations for the future make clear that it is not only in the private realm that care can be given effect. Intra-familial acts of care can carry forward into the public realm, demonstrating that “interdependency with close others” is not a recipe for non-integration (Scuzzarello, 2009). Instead, it can be a platform from which refugees can go on to build independent lives and, in the words of families themselves, give back to society. In this vein, building an ethics of care into integration policy as Scuzzarello (2009) suggests, is not an ideological stance. Rather, these findings suggest that it is a far better reflection of the reality for refugee families settling in the UK for whom the family unit motivates, facilitates and shapes integration pathways. Looking at families' future aspirations through the lens of care helps us too to understand how the very existence of hope for the future is a vital emotional underpinning to refugees' own narratives of settlement and integration. As Larsen explains:

“The envisioned future for their children ascribes meaning to the parents' present everyday lives and thus has an integrating effect, here understood in terms of an inner personal integrity in the form of a sense of existential meaning and coherence in a life within one's present surroundings.” (Larsen, 2018, p. 118)

Given the well-documented pressures of settling in a new country context after navigating what can be a complex and brutalizing asylum process (Mulvey, 2015), the emotional importance of being able to provide intra-familial care and of feeling that this will bring the family to a brighter future is critical to refugees' own notions of successful integration.

5. Conclusion

“Migration research should embrace the family as a central component of migration […] family migration should move front and center in discussions regarding migration in general.” (Cooke, 2008, p. 262)

In this paper, I have argued that, for refugees as for people taking alternative migration routes, it is not only migration but integration that should be understood “in a family way.” Even refugees who arrive alone are in many cases seeking protection not only for themselves as individuals but for their families who—even if they themselves never cross a border—may eventually rely on social and financial support sent by the individual. For refugees who do reunite under family reunion, integration pathways are shaped not only by well-documented structural constraints but by the care they actively provide in the present and hope to provide in future. This care is not an adjunct to integration. The obligations inherent in undertaking acts of care shape opportunities for progress across other integration domains. As such, familial care plays an ambivalent role in integration and its constraints may be particularly hard to overcome for women upon whose shoulders the greatest burden of care continues to rest. This said, it is important to note that what may appear to be a step backwards in one domain can in fact be a move toward refugees' own aspirations for stable, familial future. These same obligations of care often contain opportunities too, for example parents who through traveling to nursery and school meet other parents with whom they can build positive relationships in local areas. Caring about family, from afar and from within the household, is the motivator for a multitude of decisions taken at different junctures. Losing sight of the role of family in these decisions is to fundamentally misunderstand their meaning to refugee families. On this final point, exploring integration through the lens of familial care is an important way to foreground refugees' status as agents of integration rather than passive recipients of integration assistance. Care given by non-familial others can, as I and colleagues outline elsewhere, play a key practical and emotional role in integration (Käkelä et al., 2023). But giving care within the family is a realm where refugees can exercise decision-making and their own skills. While aware of the dangers of over-romanticizing the family and remaining cognizant of the risks that less powerful members of family can face, including of intra-familial violence and abuse, the accounts of the families in this cohort provide a welcome antidote to images of refugee helplessness. Instead, in considering them as family units, we see that receiving and giving care within the family is a crucial ingredient to building hope for the future. Bringing care to a central position in understandings of integration is not designed to mask its ambivalent nature. Instead, it supports feminist perspectives that ask that the work involved in caring for and about family members, in all its complexity, be brought more strongly into the light of public debate rather than confined to the shadows of the home.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not publicly available due to the potential for identifying vulnerable participants (refugee families). Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bGtlcnIyQHFtdS5hYy51aw==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Queen Margaret University Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent was sought from all participants, including, for children aged under 18, from their parents/guardians.

Author contributions

HB is the sole author of this paper and agrees to be accountable for the content of the work.

Funding

Data collection for this study was funded by the EU Asylum, Migration, and integration Fund grant number UK/2018/PR/0064.

Acknowledgments

Research design, data collection and analysis was a joint effort with my colleagues from the research team based at Queen Margaret University's Institute for Global Health and Development: Leyla Kerlaff, Arek Dakessian, and Alison Strang. We benefited from support from our third sector project partners when organizing data collection activities and interpreting our findings, for which I am most grateful. Thank you to Joe Brady and Emmaleena Käkelä for their invaluable comments on an earlier version of this paper. And thank you most of all to the families who generously shared their experiences with us.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The geographic distribution of people seeking asylum—and as a result of those who are recognized as refugees—has significantly changed since the study was completed due to the implementation of a “full dispersal model” in the UK whereby all local authorities must make arrangements to house people seeking asylum. Available online at https://www.emcouncils.gov.uk/write/Migration/Asylum_Dispersal_Factsheet_PDF.pdf.

2. ^This tool was adapted from commonly used life-coaching tools, for example: https://www.kingstowncollege.ie/coaching-tool-the-wheel-of-life/.

References

Baillot, H., Kerlaff, L., Dakessian, A., and Strang, A. (2023). ‘Step by step': the role of social connections in reunited refugee families' navigation of statutory systems. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 41, 2105–2129. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2023.2168633

Baldassar, L. (2007). Transnational families and the provision of moral and emotional support: the relationship between truth and distance. Identities 14, 385–409. doi: 10.1080/10702890701578423

Baldassar, L. (2015). Guilty feelings and the guilt trip: emotions and motivation in migration and transnational caregiving. Emot. Space Soc. 16, 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2014.09.003

Baldassar, L., and Merla, L. (2013). Transnational Families, Migration and the Circulation of Care. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203077535

Bernhard, J. K., Landolt, P., and Goldring, L. (2009). Transnationalizing families: canadian immigration policy and the spatial fragmentation of care-giving among Latin American newcomers1. Int. Migr. 47, 3–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00479.x

Boccagni, P., and Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2023). Integration and the struggle to turn space into “our” place: homemaking as a way beyond the stalemate of assimilationism vs. transnationalism. Int. Migr. 61, 154–167. doi: 10.1111/imig.12846

Bonjour, S., and De Hart, B. (2013). A proper wife, a proper marriage: constructions of ‘us' and ‘them'in Dutch family migration policy. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 20, 61–76. doi: 10.1177/1350506812456459

Bonjour, S., and Kraler, A. (2015). Introduction: family migration as an integration issue? Policy perspectives and academic insights. J. Fam. Issues 36, 1407–1432. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14557490

Calavita, K. (2006). Gender, migration, and law: crossing borders and bridging disciplines. Int. Migr. Rev. 40, 104–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00005.x

Casey, L. (2016). The Casey Review: A Review Into Opportunity and Integration. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

Cooke, T. J. (2008). Migration in a family way. Popul. Space Place 14, 255–265. doi: 10.1002/psp.500

Fassin, D. (2005). Compassion and repression: the moral economy of immigration policies in france. Cult. Anthropol. 20, 362–387. doi: 10.1525/can.2005.20.3.362

Garcia, A. C. (2019). Bordering work in contemporary political discourse: the case of the US/Mexico border wall proposal. Discour. Soc. 30, 573–599. doi: 10.1177/0957926519870048

Griffiths, M., and Yeo, C. (2021). The UK's hostile environment: deputising immigration control. Crit. Soc. Policy 41, 521–544. doi: 10.1177/0261018320980653

Grillo, R. (2008). The Family in Question Immigrant and Ethnic Minorities in Multicultural Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi: 10.1017/9789048501533

Innes, S., and Scott, G. (2003). ‘After i've done the mum things': women, care and transitions'. Sociol. Res. Online 8, 39–52. doi: 10.5153/sro.857

Käkelä, E., Baillot, H., Kerlaff, L., and Vera-Espinoza, M. (2023). From acts of care to practice-based resistance: refugee-sector service provision and its impact(s) on integration. Soc. Sci. 12, 39. doi: 10.3390/socsci12010039

Kouta, C., Velonaki, V. S., Lazzarino, R., Rousou, E., Apostolara, P., Dorou, A., et al. (2022). Empowering the migrant and refugee family's parenting skills: a literature review. J. Commun. Health Res. 11, 337–348. doi: 10.18502/jchr.v11i4.11735

Lacroix, T., Levitt, P., and Vari-Lavoisier, I. (2016). Social remittances and the changing transnational political landscape. Compar. Migrat. Stud. 4:16. doi: 10.1186/s40878-016-0032-0

Larsen, B. R. (2018). Parents in the migratory space between past, present and future: the everyday impact of intergenerational dynamics on refugee families' resettlement in Denmark. Nordic J. Migrat. Res. 8, 116–123. doi: 10.1515/njmr-2018-0014

Livingstone, S., and Byrne, J. (2018). “Parenting in the digital age: the challenges of parental responsibility in comparative perspective,” in Digital Parenting: The Challenges for Families in the Digital Age, eds M. Giovanna, C. Ponte, and A. Jorge (Gothenburg: Nordicom University of Gothenburg), 19–30.

Lokot, M. (2018). ‘Blood doesn't become water'? Syrian social relations during displacement. J. Refugee Stud. 33, 555–576. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fey059

Lynch, K., Kalaitzake, M., and Crean, M. (2021). Care and affective relations: social justice and sociology. Sociol. Rev. 69, 53–71. doi: 10.1177/0038026120952744

Mackenzie, C., McDowell, C., and Pittaway, E. (2007). Beyond ‘do no harm': the challenge of constructing ethical relationships in refugee research. J. Refug. Stud. 20, 299–319. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem008

Marlowe, J. M. (2010). Beyond the discourse of trauma: shifting the focus on sudanese refugees. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 183–198. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feq013

Matua, G. A., and Van Der Wal, D. M. (2015). Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Res. 22, 22–27. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.6.22.e1344

McMichael, C., Gifford, S. M., and Correa-Velez, I. (2011). Negotiating family, navigating resettlement: family connectedness amongst resettled youth with refugee backgrounds living in Melbourne, Australia. J. Youth Stud. 14, 179–195. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2010.506529

Mulvey, G. (2015). Refugee integration policy: the effects of UK policy-making on refugees in Scotland. J. Soc. Policy 44, 357–375. doi: 10.1017/S004727941500001X

Näre, L. (2020). Family lives on hold: bureaucratic bordering in male refugees' struggle for transnational care. J. Fam. Res. 32, 435–454. doi: 10.20377/jfr-353

Ndofor-Tah, C., Strang, A., Phillimore, J., Morrice, L., Michael, L., Wood, P., et al. (2019). Home Office Indicators of Integration Framework. Home Office.

Olwig, K. F. (2011). ‘Integration': migrants and refugees between scandinavian welfare societies and family relations. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 37, 179–196. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2010.521327

Penninx, R. (2019). Problems of and solutions for the study of immigrant integration. Comp. Migr. Stud. 7:13. doi: 10.1186/s40878-019-0122-x

Phillimore, J. (2020). Refugee-integration-opportunity structures: shifting the focus from refugees to context. J. Refug. Stud. 34, 1946–1966. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feaa012

Pittaway, E. E., Bartolomei, L., and Doney, G. (2016). The Glue that Binds: an exploration of the way resettled refugee communities define and experience social capital. Commun. Dev. J. 51, 401–418. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsv023

Pratesi, A. (2017). Doing Care, Doing Citizenship. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63109-7

Pupavac, V. (2008). Refugee advocacy, traumatic representations and political disenchantment. Govern. Opposit. 43, 270–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2008.00255.x

Rousseau, C. C., Rufagari, M. C., Bagilishya, D., and Measham, T. (2004). Remaking family life: strategies for re-establishing continuity among Congolese refugees during the family reunification process. Soc. Sci. Med. 59, 1095–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.011

Ryan, L. (2018). Differentiated embedding: polish migrants in London negotiating belonging over time. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 44, 233–251. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341710

Sajjad, T. (2022). Strategic cruelty: legitimizing violence in the European union's border regime. Global Stud. Q. 2:ksac008. doi: 10.1093/isagsq/ksac008

Schinkel, W. (2013). The imagination of ‘society' in measurements of immigrant integration. Ethnic Racial Stud. 36, 1142–1161. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2013.783709

Scuzzarello, S. (2009). Multiculturalism and Caring Ethics. On Behalf of Others: The Psychology of Care in a Global World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 61–81. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195385557.003.0004

Sheller, M. (2019). Afterword: time is of the essence. Curr. Sociol. 67, 334–344. doi: 10.1177/0011392118792919

Spencer, S., and Charsley, K. (2016). Conceptualising integration: a framework for empirical research, taking marriage migration as a case study. Comp. Migr. Stud. 4:18. doi: 10.1186/s40878-016-0035-x

Spencer, S., and Charsley, K. (2021). Reframing ‘integration': acknowledging and addressing five core critiques. Comp. Migr. Stud. 9:18. doi: 10.1186/s40878-021-00226-4

Stewart, E. S. (2011). UK dispersal policy and onward migration: mapping the current state of knowledge. J. Refug. Stud. 25, 25–49. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fer039

Strang, A., and Ager, A. (2010). Refugee integration: emerging trends and remaining agendas. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 589–607. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feq046

Strang, A., O'Brien, O., Sandilands, M., and Horn, R. (2020). Help-seeking, trust and intimate partner violence: social connections amongst displaced and non-displaced Yezidi women and men in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. Confl. Health 14:61. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00305-w

Strang, A. B., Baillot, H., and Mignard, E. (2018). ‘I want to participate.' transition experiences of new refugees in Glasgow. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 44, 197–214. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341717

Strang, A. B., and Quinn, N. (2019). Integration or isolation? Refugees' social connections and wellbeing. J. Refug. Stud. 34, 328–353. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fez040

Strik, T., de Hart, B., and Nissen, E. (2013). Family Reunification: A Barrier or Facilitator of Integration? A Comparative Study. International Centre for Migration Policy Development. doi: 10.5771/9783845252759-92

Tefera, G. W. (2021). Time and refugee migration in human geographical research: a critical review. Geoforum 127, 116–119. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.10.005

Vera Espinoza, M., Fernández de la Reguera, A., Palla, I., and Bengochea, J. (2023). Reflections on ethics, care and online data collection during the pandemic: researching the impacts of COVID-19 on migrants in Latin America. Migr. Lett. 20, 325–335. doi: 10.33182/ml.v20i2.2838

Wachter, K., and Gulbas, L. E. (2018). Social support under siege: an analysis of forced migration among women from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Soc. Sci. Med. 208, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.056

Welfens, N., and Bonjour, S. (2020). Families first? The mobilization of family norms in refugee resettlement. Int. Polit. Sociol. 15, 212–231. doi: 10.1093/ips/olaa022

Wroe, L. E. (2018). ‘It really is about telling people who asylum seekers really are, because we are human like anybody else': negotiating victimhood in refugee advocacy work. Discour. Soc. 29, 324–343. doi: 10.1177/0957926517734664

Keywords: refugee, family reunion, care, integration, migration

Citation: Baillot H (2023) “I just try my best to make them happy”: the role of intra-familial relationships of care in the integration of reunited refugee families. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1248634. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1248634

Received: 27 June 2023; Accepted: 05 September 2023;

Published: 27 September 2023.

Edited by:

Clayton Boeyink, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomReviewed by:

Gil Viry, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomJames Marson, Sheffield Hallam University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Baillot. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helen Baillot, aGJhaWxsb3RAcW11LmFjLnVr

Helen Baillot

Helen Baillot