- Forensic Child and Youth Care, Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Introduction: The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) accords children the right to give their views on all important decisions in their life (art.12 CRC). In the past decades increased awareness has risen among professionals who work with children in judicial and administrative proceedings, to hear their voices. The key question guiding this research was whether refugee children have the possibility to meaningfully participate in asylum proceedings, as required by international children's rights law and standards? Asylum application procedures are highly complex administrative procedures, that are often not adapted to the capacities and level of maturity of children. Recent studies suggest that the right to participation and information is insufficiently safeguarded for children involved in asylum procedures. Unaccompanied children seeking asylum as young as 6 years of age have to go through the asylum procedure in the Netherlands. Efforts have been put in making this procedure more child-friendly, by designing a child-friendly interview room and training immigration officers. The aim of this study was to explore to what extent the immigration authority takes into account children's voice, age and development, in line with international children's rights.

Methods: Observations have been conducted of first instance asylum application interviews with children held by immigration officers. In total 13 interviews with children aged 7–11 have been observed, that were held between 2012 and 2019.

Results: The results show that child-friendly conversation techniques and tools are used to some extent, however, immigration officers should be trained more extensively in order to enhance the effective participation of young children.

Discussion: It is concluded that interviews with children could be improved by giving children more information and using techniques to communicate with young children. In order to truly hear the child's voice the interviews should be better adapted to the age and level of development of unaccompanied children.

1. Introduction

Asylum application procedures are highly complex administrative procedures, that are often not adapted to the capacities and level of maturity of children (Smyth, 2014; Stalford, 2018; Rap, 2022a). However, unaccompanied and separated children1 usually have to go through the same asylum application procedures and asylum interviews as adult applicants. Moreover, the stakes are high, because when the application is rejected, this means that the child will have to be sent back to the country she fled. Being involved in lengthy and demanding procedures can have a profound impact on the emotional wellbeing of a child, evoking feelings of stress, anxiety and concern (Derluyn et al., 2008; Kalverboer et al., 2009; Wernesjö, 2011; Sleijpen et al., 2017; Darmanaki Farahani and Bradley, 2018; Chase et al., 2020). Moreover, it appears to be difficult for most immigration authorities to implement these proceedings in a manner that is adapted to the age, level of maturity and capacities of the child that is engaged in the procedures. Asylum procedures are often described in terms of being adversarial, hierarchical and narrowly focussing on evidence and truth-finding (Shamseldin, 2012; Dahlvik, 2017; Lundberg and Lind, 2017; Stalford, 2018). Several studies have shown that children experience hostile interrogation techniques, feel attacked and intimidated, and that questions are asked to expose inconsistencies and questioning the credibility of the child's story (Kohli, 2006; Chase, 2013; Hedlund, 2017; Brittle, 2020; Iraklis, 2020; Rap, 2022a). Moreover, immigration officials often do not possess extensive skills which pertain to communicating with children, due to a lack of training and specialization (Doornbos, 2006; Keselman et al., 2008, 2010a; Rap, 2022b). In the Netherlands, similar issues with regard to the treatment of children in asylum procedures have been identified, such as lack of training of immigration officers in interviewing children and knowledge about child development, insufficient information and preparation provided to children, confronting children with contradictory statements made by siblings, and posing detailed questions (Van Willigen, 2003; Kloosterboer, 2009; Strik et al., 2012; Uzozie and Verkade, 2016; Werkgroep Kind in azc/COA/Avance, 2018; Werkgroep Kind in AZC/Avance, 2021).

In recent years, influenced by children's rights discourse and in particular the right of the child to be heard (article 12 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, CRC) and child-friendly justice,2 increased awareness has risen to adapt the asylum procedure to the capacities and level of maturity of children [Kilkelly et al., 2019; European Union (EU), 2021; Council of Europe, 2022]. Liefaard (2016) explains that “[c]hild-friendly justice aims to make justice systems more focused on children's rights, more sensitive to children's interests, and more responsive to children's participation in formal and informal decision making concerning them”. Practically, child-friendly justice can be operationalized in specific children's rights such as the right to be heard, right to information, right to protection, right to privacy, right to non-discrimination and the best interests of the child principle [European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), 2017]. In this article, the right to be heard and to information are specifically regarded in relation to asylum interviews with children. The right to be heard implies that children who are capable of forming their own views have the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting them, including in judicial and administrative proceedings (article 12 CRC). The views and opinion of the child should be taken into account giving due weight to the age and maturity of the child [article 12(1) CRC]. Moreover, children's growing capacities should be taken into account in the exercise of their rights (article 5 CRC). In order to make decisions that are in the best interests of children (article 3 CRC), the views of the child should be considered [UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 2009, para. 74]. The UNCRC has recommended that in order for children seeking asylum to enjoy the right to be heard in asylum procedures, states must provide children access to procedures in an age-appropriate manner, having regard for the age and evolving capacities of the child [UN Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (UNCMW) and UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 2017, para. 37]. The child should have the opportunity to present her3 reasons that lead to the asylum application, either filed independently or by a parent [UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 2009, para. 123]. Every child, however, also has the right not to exercise her right to be heard – it should be seen as a choice, not an obligation [UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 2009, para. 16]. The UNCRC explains that states have to ensure that the child receives all necessary information and advice to make a decision in line with her best interests [UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 2005, para. 25; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 2009, para. 16]. Therefore, children should be enabled to understand the procedure and its consequences, have access to age-sensitive information and decisions should be communicated to children in a language and manner they understand [UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2012].

The aim of this study is to explore how young unaccompanied children (below the age of 12) are interviewed by the immigration authorities in the Netherlands and to what extent this takes place in a manner that is adapted to the age and level of development of children, in line with the requirements that can be distilled from the international children's rights framework. This question will be addressed by presenting the findings of observations conducted of asylum interviews with unaccompanied children. This study takes a socio-legal perspective (Creutzfeldt et al., 2020), in which the international children's rights framework is taken as a starting point to analyse the child's right to be heard in asylum procedures. This study aims to empirically explore how the child's right to be heard is implemented in the legal practice of asylum procedures. This article will start with a brief overview of previous research conducted on interviewing children in legal (forensic) contexts, including asylum procedures. The literature on forensic interviewing of children can provide important starting points for analyzing asylum interviews. Second, the legal context of the asylum application procedure in the Netherlands will be briefly explained. Third, the methodology of this study will be outlined. Fourth, the results of this study will be presented, focussing on the preparations and explanations, conversation techniques used by immigration officers and the content of the interview. This article will conclude with a discussion of the conclusions, implications and limitations of this study.

2. Interviewing refugee children

In current debates around migration, a divide is visible between on the one hand depicting unaccompanied children as vulnerable victims, who are sent away by their parents and are in need of care and protection and on the other hand depicting them as fortune hunters or dangerous young men from “safe countries” who are a threat to Europe's security and social welfare system (Flegar, 2018; Lems et al., 2020; Kovner et al., 2021; Fox et al., 2022).

In the context of migration law (unaccompanied) children are often identified as a vulnerable group. These children are frequently portrayed as vulnerable and helpless victims, who are not able to exercise agency and voice their opinion (Herring, 2012; Flegar, 2018; Lems et al., 2020; Mendola and Pera, 2022). They are seen as victims of migrant smugglers or traffickers, or even their own parents who are desperate enough to send their children alone to a foreign country. Beduschi (2017) shows in her analysis of European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case law concerning migrant children that the ECtHR uses the vulnerability of migrant children and the best interests of the child principle to emphasize the need for special measures of protection for these children. Beduschi (2017) also recognizes that identifying children as a vulnerable group poses risks, such as not regarding their agency and over-emphasizing their dependency upon adults. Several studies have shown, however, that unaccompanied refugee children exercise agency in the choices they make, regarding their decision to migrate and to build a future in a new country (Allsopp et al., 2014; Belloni, 2020; Rap, 2022a).

On the contrary, unaccompanied children are also often first considered as migrants who pose risks to society, rather than children who are exposed to risks themselves (Thorburn Stern, 2015) and they are subjected to restrictive detention and deportation regimes (Cleton, 2022). With regard to the treatment of unaccompanied children a tension is visible between “migration management and the normative imagery of liberal, human rights-respecting states” (Wittock et al., 2023: p. 17). States may adapt procedures in order to operate in line with international human and children's rights standards, such as the CRC, but do so within the existing structures, policies and practices.

Under the CRC all children until the age of 18 (unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier) are entitled to the rights set forth in the Convention (article 1 CRC). The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (2005, para. 7) has defined unaccompanied children as “children, as defined in article 1 of the Convention, who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.” A distinction is made with separated children “who have been separated from both parents, or from their previous legal or customary primary caregiver, but not necessarily from other relatives. These may, therefore, include children accompanied by other adult family members” [UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 2005, para. 8]. States, however, differ in how they define childhood in their legal systems, in relation to refugee children. Countries apply different age limits with regard to the legal capacity of children to apply for asylum and the age from which children are interviewed by the immigration authorities. For example, age thresholds have been used to control migration flows by limiting the rights of older children in asylum legislation and family reunification procedures (Drywood, 2010). In a number of EU member states specific age limits are laid down for interviewing children in asylum procedures, ranging from 6 to 18 years. In other member states, courts decide on an ad hoc basis whether or not to provide children with the opportunity to be heard [European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), 2018]. For example, in the United Kingdom, all unaccompanied children from the age of 12 are interviewed by the immigration authorities and children below the age of 12 can be interviewed if they are willing and found to be mature enough (Coram Children's Legal Centre, 2017). In this article I will explore the child's right to heard in asylum interviews with unaccompanied children in the Netherlands.

As mentioned in the introduction of this article, previous studies have shown that it is difficult for unaccompanied children to participate in a meaningful manner in asylum procedures (see Kohli, 2006; Rap, 2022a). Power is unequally distributed in the asylum procedure between the state and the child and the child bears the burden of proof (Dahlvik, 2017; Lundberg and Lind, 2017). The child's testimony and evidence play an important role in substantiating the asylum application (Shamseldin, 2012; Stalford, 2018). Lundberg and Dahlquist (2012: p. 74) conclude that as a consequence of the fear that children have of being returned to their home country, they “squeeze their stories into what was expected from them, or they just turn quiet,” which in turn may lead to suspicion by the authorities concerning the accuracy of the asylum story and motives (see also Kohli, 2006).

Immigration officers have the “difficult task to distinguish facts from fiction” in order to determine whether the asylum applicant should be granted protection (Doornbos, 2005: p. 104). One of the assumptions underlying the task of the immigration officer is that a refugee is able to present her story throughout the asylum process in a coherent manner and without inconsistencies. This has been proven to be particular challenging given the cultural and language differences between the immigration officer and applicant, the institutional context, the aim of the interview and the traumatic and highly emotionally-ridden events that are discussed (Doornbos, 2005; Keselman, 2009; Dahlvik, 2017). With regard to young children, it is expected that additional challenges are present given the level of development and understanding of children. Moreover, often immigration officers' expectations of the knowledge children possess and the answers they can provided to detailed questions is too high (Van Willigen, 2003). Research among unaccompanied children shows that they find it difficult to disclose their story to adults (Kohli, 2006; Keselman et al., 2010b), that they selectively share information with adults and peers, displayed a sense of distrust toward social workers and others representing the asylum system (Chase, 2010) and need to receive more information and support in the asylum process (Lundberg and Dahlquist, 2012).

In addition, research in the field of forensic interviewing (e.g., police interrogations, court hearings) indicates that young children and do not know the social codes of formal interview settings (Lamb and Sim, 2013). In order to have a meaningful conversation with a young child in such setting it is of importance to explain the social rules before the start of the interview and to use metacommunication (i.e., communication about the communication, for example to explain the intentions and goal of the interview to the child, Delfos, 2009). The goal of the interview and the role of the interviewer need to be explained clearly to the child and the interviewer should build rapport (i.e., make a connection and build trust) (Lamb et al., 2008; Delfos, 2009; Saywitz et al., 2010; Van Nijnatten and Jongen, 2011). When a child is not well-prepared before the interview, she may try to give the answers that she expects to lead to the approval of the adult. The child will seek for (non)verbal signals of approval by the adult and this will result in socially desirable answers (Lamb et al., 2008; Lamb and Sim, 2013). Moreover, not knowing what to expect leads to feelings of stress and anxiety, which causes children to clam up (Smeets et al., 2020). Stress may also increase children's susceptibility to false suggestions and may lead to less detailed responses during interviews (Hritz et al., 2015).

Children are in any case more compliant and suggestible in interviews with adults. Compliance means that a person confesses falsely, or gives false information just to speed up or end the interview or interrogation. Suggestibility refers to the extent to which a person can be led to believe the information that is wrongly presented to her (Gudjonsson, 2003). Given that children often assume that they have to answer every question they are asked and that they are in a subordinate position to adults, they are particular vulnerable to suggestion (Saywitz et al., 2010). However, the quality of children's statements in legal interviews is influenced only to a limited extent by the child's age, level of development and individual susceptibility to suggestion and even more so by the quality of the interviewer and conversation techniques used (Finnilä et al., 2003). Ineffective conversation techniques are for example using difficult words or complex sentences, asking closed-ended questions or suggestive questions or not explaining the goals of the conversation. This may lead to increased suggestibility, inaccurate and socially desirable answers by children (Cederborg et al., 2000; Klemfuss and Ceci, 2012). By contrast, when interviewers use conversational techniques, such as asking open-ended questions, reflective listening and summarizing, children are encouraged to give longer, more detailed, more accurate, and less self-contradictory responses (Cederborg et al., 2000; Lamb et al., 2008; Klemfuss and Ceci, 2012). Reflective listening (e.g., repeating what the child said) and summarizing can be used to check whether the interviewer has understood the child's story accurately and to structure the conversation (Erickson et al., 2005; Levensky et al., 2007). The use of these conversation techniques could also be helpful in interviewing children in asylum procedures.

3. The asylum application procedure in the Netherlands

In 2021, 2.191 unaccompanied children up to the age of 18 applied for asylum in the Netherlands, of which 370 children under the age of 14. They mainly came from Syria, Eritrea, Iraq and Somalia (Ministry of Justice and Security, Immigration, and Naturalisation Service and IND Business Information Centre, 2021; CBS, 2022). In the Netherlands the Immigration- and Naturalization Service (INS) is responsible for administering the asylum procedure. The goal of the asylum procedure is to determine whether the applicant is in need of international protection, based on the Refugee Convention, the European Convention on Human Rights and the Common European Asylum System (CEAS).

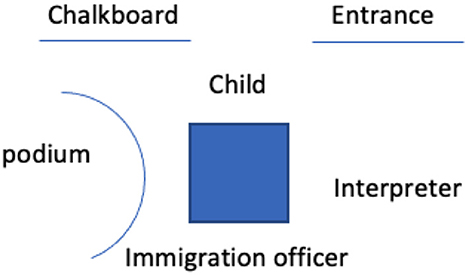

When an unaccompanied child arrives in the Netherlands and reports to the authorities, she is immediately placed under the supervision of a legal guardian (i.e., a child protection officer employed by the guardianship organization for unaccompanied minors Nidos, article 3.109d(1) Aliens Decree 23 November 2000). In addition, the child is assigned a lawyer and information about the procedure is provided by the guardian, the Dutch Council for Refugees and the lawyer [article 2.2 Aliens Act Implementation Guidelines 2000 (C); article 3.109(2) and article 3.108c(2) Aliens Decree 2000]. The first interview takes place at the registration phase, and unaccompanied children are asked about their personal details and family composition [article 2.11 Aliens Act Implementation Guidelines 2000 (C)]. After registration unaccompanied children have the right to a rest and preparation phase of 3 weeks [article 3.109(1) Aliens Decree 2000]. The purpose of the second interview is to identify the asylum narrative and flight motives of the child [article 2.11 Aliens Act Implementation Guidelines 2000 (C)]. It is expected that unaccompanied children collaborate with the interviews conducted by the INS as part of the asylum application [article 3.113 Aliens Decree; 2.4 Aliens Circulair 2000 (C)]. Unaccompanied children between the ages of six and twelve, which is the target group of the current study, are interviewed in a specially designed interview room for children by trained immigration officers and in the presence of an interpreter (see Figure 1 and Section 5). These immigration officers usually have an affinity for working with children and some of them have a social work degree [Aliens Circular 2000 (C), article 2.11; Aliens Decree 2000, article 3.113; Official Journal, 2015, 20705, Explanation part F].4 According to the law, the guardian or lawyer should be allowed access to the interview and may ask questions or make comments at the end of the interview [article 3.109d (4-5) Aliens Decree; Aliens Circular 2000 (C), article 2.11]. Dutch immigration law furthermore prescribes that the INS needs to take into account the age, level of development and burden (sic) when interviewing a child below the age of 18 [Aliens Circular 2000 (C), article 2.11]. In addition, it has been laid down by law that “If an educational or psychological examination reveals that a foreign national younger than 12 has problems that impede a further interview, the IND will not conduct a further interview” (article 2.11; see also article 3.113 Aliens Decree 2000). Within 6 months after the asylum application has been filed the INS needs to take a decision [article 42(1) Aliens Act 2000]. This time limit can be prolonged with 15 months when for example it concerns a complex case or when many applications are filed at the same time [article 42 (4-5) Aliens Act 2000]. In August 2022, only 17% of all asylum cases received a decision within the legal time limits and the average length of the first instance asylum procedure was 35 weeks (IND, 2022). However, due to a high influx in asylum applications in 2022, the time-limits have been prolonged at the time of writing this article.

4. Methodology

The results that are presented in this article are based on observations of first instance asylum application interviews with children held by immigration officers. These concern the second interview during which the asylum motives of the child are discussed. In total 13 interviews have been observed, that were held between 2012 and 2019.5 Two cases in 2019 were observed by the researcher in person in a video link room at the office of the INS. Of the other 11 interviews the video recordings were observed. Observing video recorded interviews and through a live video link had the advantage that the researcher did not interfere with the interview setting (see Bryman, 2012).

Since all children fell under the guardianship of Nidos this organization as well as the INS provided permission to conduct the observations, giving consent either on behalf of the children or immigration officers. The immigration officers were informed about this study through an information letter provided to the INS and through the interviews conducted with immigration officers as part of this study (Rap, 2022b). Because in all but two cases the asylum procedures of the children had been completed at the time of the observations it was decided not to contact the children about this study. Therefore, the personal details and references to places were removed from the transcripts to ensure protection of the children's privacy. The personal data concerning the children was only collected through the observations and no other written reports or files were available for the researcher. To ensure the anonymity of the immigration officers, no personal data was collected concerning them. The video recordings have been selected by the INS, based on the availability of tapes at the INS office. The researcher watched the recordings at an INS office. The Committee Ethics and Data of Leiden Law School provided ethical approval of this study. At the start of this study the author was employed by the Department of Child Law at Leiden University as assistant professor and therefore obtained ethical approval from this institute.

The sample of 13 interviews consists of four girls and nine boys. The average age of the children was 9.5 years, ranging from 7 to 11 years. Nine out of 13 children originally came from Syria6 and the others came from Eritrea, Iraq, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Mongolia.7 The interviews lasted on average 49 min, ranging from 19 to 72 min. This excluded the one or two breaks that were taken in six out of thirteen interviews. The breaks lasted between 2 and 45 min.8 Several immigration officers were observed in more than one interview. Next to the child, the immigration officer and the interpreter, a guardian (N = 10) and/or family member (N = 4) accompanied the child to the interview.9 In almost half of the cases a support person present in the interview room itself.

In order to structure the observations an observation scheme was used. The observation scheme consisted of the following elements to be filled in: general information about interview, map of the position of the participants in the room, explanations before the start of the interview (e.g., about the video equipment, asylum procedure, interpreter), the asylum story (e.g., topics, questions, tools used) and the closure of the interview (e.g., input guardian, explanation follow-up procedure, questions from the child). Detailed and chronological accounts of the interviews were produced, which were guided by the observation scheme. Especially with regard to the video recordings it was possible to produce verbatim transcripts. The transcripts of the interviews were coded in NVivo, using a code scheme developed by the author. The observation scheme and coding scheme form the basis of the presentation of the results below.

Due to the small sample size and selection of cases by the INS the results of this study cannot be generalized to all interviews with young unaccompanied children conducted by the immigration authorities in the Netherlands.

5. Asylum interviews with young children

In the Netherlands, asylum application interviews with children below the age of 12 take place at one location of the INS, where a child-friendly interview room is designed, modeled after police interview rooms for child victims. The room is equipped with audio-visual recording equipment and a video link is established with another room, where the guardian can observe the interview. Three cameras record the interview and the footage is livestreamed in the video link room. The interview room itself measures ~30 m2, with a raised stage in the corner, a table with office chairs and a high children's chair, a separate desk with a computer, a cupboard with toys and tools and a chalkboard. During the hearing, special aids and tools can be used, such as puzzles depicting means of transport, a folder with photographs of different countries, icons (for example of family, religion, school and travel) and dots on the stage that can be used to depict the journey. The INS internally trains staff to conduct interviews with young children. A 1-day training titled Interviewing unaccompanied children of 6–12 years has been developed, which was attended and observed by the author in 2019. The training manual of the course was also available to the researcher.

The results of the observations of the interviews will be organized around three main themes: (1) the preparations and explanations provided to the child by the immigration officers (2) the conversation techniques used by immigration officers and (3) the content of the interview and the types of questions asked.

5.1. Preparations and explanations

As explained above it is of importance when interviewing a child to make her feel at ease and to prepare the child by explaining the aim and structure of the interview. In most observed cases an explanation was given to the child about the audio-visual recording (8 out of 13) and the video-link room (9 out of 13). One immigration officer gave the following explanation:

IO10: Since you are younger than 12 years, I will not immediately type out everything on the computer, but it will be recorded. Those lights, do you see those? Those are cameras. This is the table where we will sit at. There is your guardian. Look, she is waving. Ok? [They are standing in the video link room, SR] (Interview 3, 8-year-old boy).

Next to this technical explanation, the immigration officer should explain the procedure of the interview and verify whether the child understands the interpreter. In 11 out of 13 of the observed cases the child was asked if she understood the interpreter. The procedure of the interview itself, the aim of the interview, the role and expectations of the child, ground rules and taking breaks, were not explained very extensively in most cases. Only in four cases the interview contained an elaborate introduction.

A final part of the introduction is to verify whether the child understands what has been explained. Moreover, some immigration officers also check whether the child is vulnerable to suggestion, i.e., easily agreeing with wrongly information presented to her. In the manual of the INS course Interviewing unaccompanied children of 6–12 years, it is explained that the child's suggestibility can be tested using the “red car test.” In some of the interviews this has been observed:

IO: This morning, when I went to work, I drove in my red car to work, is that right?

C: Me or she? I don't know.

IO: No. How come you don't know?

C: I don't know how you came here.

IO: You cannot know that, because you did not see me this morning. This was a little trick, because I want to explain to you that the answer “I don't know” is a correct answer in this room. If your teacher is asking you a question, then “I don't know” is not a good answer, because she wants to hear an answer, but here, it is fine, because there are things you really just don't know.

C: That is good (Interview 12, 10-year-old boy).

It remained unclear, however, why this test was not consistently applied in all interviews, since the explanation to the child could help her in understanding the importance of saying “I don't know.” In most cases checking the understanding of the child took place in a much briefer manner, by just asking if the child understood the explanations. Despite the predominantly short introductions, most immigration officers explicitly stated that the child could say “I don't know” to a question asked:

IO: You came here because I have some questions for you. If I ask you a question and you don't understand, it is important that you tell me. If you don't know the answer, it is also important to tell me, because you don't have to make up the answer, it is not about right or wrong (Interview 8, 10-year-old girl).

At the closure of the interview, it was observed whether explanations were given regarding the follow-up of the interview, with regard to the procedure and the decision that needs to be taken. However, usually the closure only contained some brief comments about the fact that the immigration officer will make a report of the interview and will send it to the child's lawyer:

IO: I will make a report of this conversation, that will take a couple of days before I finish that and then I will send it to your lawyer. And then your lawyer will call you or your dad to discuss it and to see whether everything is correct.

IO: Do you know what a lawyer is?

C: No.

IO: I will explain dad about what will happen (Interview 13, 8-year-old boy).

When the interview has been conducted, the child only plays a marginal role in the final phase of the asylum procedure (see Rap, 2020, 2022a). The lawyer is involved in the procedural steps that follow the interview and this part of the procedure takes place in writing. The lawyer has the task to discuss and explain the interview report with the child. The lawyer has the possibility to send the INS corrections and additions to the report. Subsequently, the INS will decide whether the child will be granted asylum (articles 3.112–3.114 Aliens Decree).

5.2. Conversation techniques

During the interviews it was observed that immigration officers used certain conversation techniques, such as metacommunication, small talk, complimenting the child, summarizing, and bringing the child back to reality, to adapt the interview to the level of maturity and conversation skills of the child. These techniques were taught to the immigration officers in the courses they followed. Most immigration officers explained that the child should say “I don't know” in case she does not know the answer to the question and should say it when she does not understand something that is asked. Children can be more suggestible compared to adults, therefore most immigration officers explicitly repeated this during the interview. Some immigration officers gave feedback when a child did not know an answer or stayed silent:

IO: Do you know how old your father is?

C: No

IO: That is very good, if you don't know you can just tell me and you don't have to make something up (Interview 3, 8-year-old boy).

At the end of the interview some children were asked about their views on the interview:

IO: How did you think it went?

C: Normal.

IO: You did well.

IO: Were the questions too difficult?

C: No.

IO: You only used the interpreter a little, did you understand her well in French?

C: Yes (Interview 9, 10-year-old girl).

The second conversation technique that was observed is the use of small talk to make the child feel at ease. Immigration offers asked the child how she traveled to the immigration office, if she liked to go to school, and about learning the Dutch language, or her physical appearance (hair, henna paintings, braces, etc.). Some officers asked whether the child would like to make a drawing or coloring picture. It was observed that the use of small talk differs substantially among the immigration officers, with some of them hardly ever doing so and others integrating small talk throughout the whole interview. Children are also complimented about their participation in the interview. This mostly happens at the end of the interview, when the immigration officer ends the conversation:

IO: That was my last question. You did very well, I want to compliment you on that (Interview 3, 8-year-old boy).

Some immigration officers, however, also gave compliments during the interview, to encourage the child:

IO: It is really good that you were able to tell everything so well (Interview 4, 10-year-old girl).

Summarizing the answers of a child was used by some immigration officers as well. It was not used extensively by every immigration officer and usually only a few times per interview. For example, one immigration officer summarized as follows:

IO: We already discussed a lot, you told me where you lived, which language you speak, how you came to the Netherlands, you told me about school and church, who you lived with in a house and you told me about the day you left your home, about the bad people with guns, you told me they came to get money (Interview 9, 10-year-old girl).

The final conversation technique that was observed entails ending the interview by bringing the child back to reality (the here-and-now technique). Most interviews ended this way, for example, by asking the child what she will do during the remainder of the day or how she will travel home:

IO: What will you be doing when you come home this afternoon?

C: I will be coloring.

IO: You are not going to watch TV?

C: That is not necessary.

IO: You go and color or play with your little brother and fight with your brother [laughs, SR]. You don't need to go back to school today, I reckon (Interview 11, 11-year-old girl).

Making the child feel more at ease by using small talk and bringing the child back to reality are techniques that immigration officers are instructed to use when interviewing young children, so that the experience will be less stressful for the child and the immigration officer will be able to get more information from the child. This shows how the age and level of development of children is taken into account during the interviews.

However, as was observed with regard to giving explanation on the follow-up of procedures, in most interviews not much time was devoted to the final part of the interview. Next to the usage of conversation techniques, immigration officers could also make use of the aids and tools that were available in the child-friendly interview room. In half of the interviews, tools were used. Mostly involved pencil and paper, when the child was for example asked to draw a map. In one case the blackboard was used to visualize the places where the child had lived. In another case the podium with dots in the carpet was used, to explain with every step to which country the child had traveled:

IO: And where did you live back then?

C: In Turkey.

IO: In the hotel or somewhere else?

C: Somewhere else.

IO: And then to the next one, where did you live then?

C: The hotel.

IO: And after that?

C: In France.

IO: And where did you go after that?

C: Holland.

IO: And then with your dad? I get it. And now you have done some exercises.

C: A little bit.

C: I want to do a different kind of sports, moving around.

[He stands on his head on the podium, he grabs the big bear, SR].

IO: We are going to work a little longer, after that you can play.

IO: Do you play sports in the Netherlands?

C: Physical Education, karate (Interview 13, 8-year-old boy).

5.3. Content of the questions

The main part of the interview revolved around the child's asylum story, with questions to verify where the child came from, why she sought asylum and whether the child was in need of international protection. Moreover, the child was asked in detail about her situation in the country of origin, whether she was in school, what she usually did during the day, what kind of house the family lived in and the different places and countries the child lived in. Also, questions were asked about parents, siblings and other family members; their names and age, what kind of work they did, where they lived and where they currently resided and if they were still in contact with the child.

For example, questions were asked about birth places and places of residence of (grand)parents:

IO: Do you know where your dad was born, in what city or village in […]?

C: I don't know. Maybe he was born in X., but I don't know in which city.

IO: Do you know where the dad and mom of your dad live?

C: I don't know where they live (Interview 3, 8-year-old boy).

Also, questions were asked about the whereabouts of the child's parents:

IO: Why didn't you mother come to the Netherlands?

C: She left, but I don't know.

IO: What do you mean?

C: I heard that she was going to leave.

IO: And your father?

C: He is in prison.

IO: Who did you hear that from?

C: From mother and family.

IO: Why is he in prison?

C: I don't know.

IO: Where is he in prison?

C: I don't know.

IO: In […]?

C: I don't know, I think so (Interview 2, 10-year-old boy).

In some cases, the child was also asked about her ethnicity:

IO: You were born in […], a very big country. There are different groups of people living there, Syrians, Kurds, Palestinians. Do you know which group of people you belong to?

C: I am […] (Interview 3, 8-year-old boy).

The interviews also contained questions about the flight of the child to the Netherlands, what means of transportation the child used, with whom she traveled, in which countries she had lived and whether the child knew what a passport was:

IO: Dad brought you. But if you travel, you have to arrange many things, a passport, an airline ticket. Can you tell me about the journey, what do you know about that?

C: I don't know.

IO: Did you arrive by plane? First you went to Greece I believe. Yes, indeed, from Lebanon to Greece and then to the Netherlands. The reason I know that is because I can see that in your passport. These stamps in your passport were put there by customs, when you travel through somewhere. Was this the first time you went flying?

C: No, it was not the first time, but I do not remember the first time (Interview 3, 8-year-old boy).

The above excerpts show that the questions posed required the child to have detailed knowledge about her parents or other family members. Also, the topic of ethnicity is abstract and the immigration officer did not verify whether the child understood the notion of ethnicity or had heard about the different ethnic groups before. Therefore, the child was not able to give detailed knowledge and it remained unclear whether the child understood the content of the questions and answered those accordingly. In the excerpt in which is asked about the journey to the Netherlands it can be noticed that the intention of the immigration officer is not clear to the child, because the question “Can you tell me about the journey, what do you know about that?” is too open and the child was not motivated to provide an answer. Moreover, the immigration officer filled the answer in herself which gave the impression to the child that she already knew the answers. This emphasized the notion of the all-knowing adult, that young children have (Delfos, 2009).

In order to verify whether the child is a refugee or otherwise in need of international protection, a question that was always posed was why the child had left her country of origin and whether that was connected to for example a war or violence:

IO: The war in […] has been going on for a long time, at one point you left, do you remember why you left at a certain moment, did something happen or why did you leave?

C: Nothing happened, but to make sure nothing would happen to us, we left.

IO: It was just to be sure, they did not want something to happen to you of course. That makes sense, I understand that (Interview 8, 10-year-old girl).

IO: When there was no war in X., no trouble, then why did your family leave that place? Can you tell me that?

C: My dad always watched the news and told us that there is war in other places and that is why he decided to leave with my uncle.

IO: I understand that (Interview 12, 10-year-old boy).

In the same line of reasoning of the immigration officers, another recurring question in the interviews revolved around whether the child had any annoying or cruel experiences in her country of origin:

IO: During the war, people can do really mean things to each other. Has anyone ever done something bad to you, or called you names?

C: No.

IO: And did that happen to your parents?

C: No.

IO: And to your sisters?

C: No.

IO: They were still little right (Interview 6, 9-year-old boy).

IO: Did you hear anything else from the war? Sounds, planes?

C: Planes.

IO: What did you hear?

C: I don't remember.

IO: Are there other things you can remember?

C: No.

IO: Did anyone ever hurt you in the war?

C: I don't remember, I was very young, I don't know if I was still in […] at that time.

IO: Did anyone ever hurt your family?

C: I don't know (Interview 2, 10-year-old boy).

It can be observed that many open directive questions were asked. These are questions that refocus the child's attention on details or aspects of events that she has already mentioned, providing a category for requesting additional information using “Wh-” questions (Keselman et al., 2008: p. 106). In many instances the child was not able, however, to provide an answer, because she might not have had such detailed knowledge. Also, questions concerning the reasons for flying, were predominantly posed in the “Why-form.” This can be difficult for the child to answer for various reasons. First, the child is asked to explain why she has left her home country, implying a form of accountability or responsibility for her actions or even the decisions made by others, such as parents. Second, young children cannot fully understand causal relationships, which are often asked about when using a “Why-question” (Delfos, 2009), which makes it difficult for them to provide an answer to these questions.

Despite the fact that some immigration officers used conversation techniques such as metacommunication, the reason for asking these questions and the intention of the immigration officer were not made clear to the child (see also Rap, 2022a). The confusion among children about the intention and purpose of the interview often also became clear at the end of the interview, as shown by the following excerpt:

IO: Is there anything else you want to tell or ask?

C: Why am I here?

IO: Everybody who wants to stay in the Netherlands comes here. We always want to hear from the people themselves. Everybody gets a conversation, including children.

C: Can we stay?

IO: That will be decided soon. Do you understand?

C: Can my mother come here from […]?

IO: That is the next step. Your guardian can explain all about that.

C: If we cannot stay, do we have to go back?

IO: That is a small chance, you don't have to worry about that. We don't send people from […] back for no reason, when there is war going on (Interview 2, 10-year-old boy).

This excerpt shows that the most important question the child had was whether he could stay in the Netherlands and whether he could be reunited with his family. The fact that the purpose of the interview was to make a decision on that, was not clear to the child.

The above excerpts also show that immigration officers relied heavily on closed-ended questions (e.g., “do/did you…”), which were often factual by nature and highly detailed. This confirms the findings by Keselman et al. (2008), who concluded that in Sweden immigration officers made extensive use of focused, option-posing questions (i.e., the child's attention is directed toward details or aspects that the minor has not previously mentioned, asking her to affirm, negate, or select an interviewer-given option using recognition memory processes Keselman et al., 2008: p. 107) and open directive questions, which inhibited children to give free-recalls of their story. Doornbos (2005) observed in her study involving adult asylum applicants that they had “great difficulty with the emphasis on facts, names, places, and dates” (p. 120). Moreover, applicants are expected to know about the geography or political situation in their country of origin and a lack thereof is often seen as an indicator of incredibility, which plays an important role in assessing the asylum application (Dahlvik, 2017). The same difficulties in answering the questions posed by the immigration officers have been observed in the present study, which probably was exacerbated by the young age of the applicants.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to explore how young unaccompanied children (below the age of 12) are interviewed by the immigration authorities, the extent to which this takes place in a manner that is adapted to their age and development, and in accordance with international children's rights standards. Since, in the Netherlands unaccompanied children from the age of six are interviewed by the immigration authority as part of their asylum application, this study examined the manner in which these interviews are conducted in practice with young unaccompanied children. In the case of unaccompanied children seeking asylum, their story plays a crucial role in the assessment of the asylum application. The goal of the asylum procedure is to determine whether the child is in need of international protection and therefore the child's identity and asylum motives need to be investigated. Truth-finding is an important element of the procedure, which determines the content of the interview (Shamseldin, 2012; Stalford, 2018; Rap, 2022b). Although, in line with the children's rights framework, children have the right and not the obligation to be heard in proceedings, in asylum cases this point of departure is rather problematic. In practice, the child is expected to cooperate with the authorities, because the child is the applicant and asks the receiving state for international protection. This implies a relationship of dependency and hierarchy between the child and the immigration officer. Moreover, due to the young age of the children, and the fact that the stakes are high for them (i.e., being granted a residence permit) the use of forensic interviewing techniques could be helpful, to facilitate a meaningful conversation that is of benefit to both parties.

The asylum interviews with young unaccompanied children in the Netherlands were analyzed based on three aspects of the interview: preparations and explanations, the conversation techniques used by the immigration officers and the content and types of questions asked during the interview. First, it was shown that immigration officers provided several explanations to the child, in preparation of the actual interview. However, a thorough explanation of the aim of the interview, ground rules for the conversation, what was expected from the child during the interview, and explaining the follow-up procedure after the interview was largely lacking. Also, immigration officers did not devote much attention to verifying whether the child understood the explanations provided. It was saying that several children asked at the end of the interview about the outcome of the procedure and when they would receive the final decision. Second, the use of specific conversation techniques, such as metacommunication, small talk, complimenting the child, summarizing, and bringing the child back to reality, differed substantially among immigration officers. The child-specific tools that were available for immigration officers, were only used in half of the cases. Third, and relatedly, the fact that the use of explanations, preparations and conversation techniques showed several gaps influenced the manner in which children were able to respond to the questions that were asked. The answers to the questions show that many children did not fully understand the purpose of questions, were not able to give detailed answers and were lacking knowledge concerning the implications of the interview. The lack of substantial responses the children gave raises questions concerning their understanding of the questions and the aim of the interview.

Previous research has shown that lack of information is a common problem for children involved in asylum procedures (Rap, 2020, 2022a). Lundberg and Dahlquist (2012) for example observed that children find it hard to cope with the uncertainties around whether they will receive a residence permit. For children who apply for asylum, the stakes are very high, since the outcome of the procedure will determine whether they can stay in the Netherlands and in a later stage be reunified with their family. Therefore, more information, provided at different occasions and in a way that they understand, could contribute to feeling less stressed and insecure (see also Rap, 2022a). More elaborate introductions, may benefit their performance during the interview, since research on forensic interviewing has shown that children need explanations in this unfamiliar setting, that this will alleviate feelings of stress and anxiety, which in turn will lead to less suggestibility. It is also of importance that children are informed at the end of the interview about the procedures, possible outcomes and time-limits.

This study shows that the INS has made a start with adapting the asylum procedure to young children, by designing a child-friendly interview room and by providing training to immigration officers. This shows that the Netherlands is not blind to international children's rights obligations. However, this study also shows that immigration officers should be trained more extensively in order to adapt the interview to young children and to become more familiar with child-specific conversation techniques. In previous research it was confirmed that trained interviewers made more frequent use of invitations to the child to freely recall their story. This could result in obtaining richer and more accurate information (Keselman et al., 2008; see also Doornbos, 2005). This would not only benefit the child, because she is made feel more comfortable in talking and less stressed (Lundberg and Dahlquist, 2012), but also the INS, because it would be able to receive more detailed and accurate information to base its decision on. This is of importance, because in the Dutch asylum procedure much emphasis is laid on truth-finding and credibility of the child's story. In order to truly hear the child's voice in a child rights compliant manner the interviews should be better adapted to the age and level of development of unaccompanied children.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the sensitivity of the data collected. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SR, cy5lLnJhcEB1dmEubmw=.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Committee Ethics and Data of Leiden Law School, Leiden University. Written informed consent for participation was not provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because the legal guardianship organization responsible for these children gave its written informed consent.

Author contributions

SR developed and contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analyses, wrote the draft of the manuscript and contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO)—Social Sciences and Humanities under Grant No. 451-17-007 4135.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Dutch Immigration and Naturalisation Services and Nidos for their support and facilitation of this study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For practical reasons, in this article will be referred to unaccompanied children, separated children are to be considered under this heading as well.

2. ^See Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child-friendly justice, adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 17 November 2010 at the 1098th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies.

3. ^For practical reasons, in this article children and adults are referred to using a feminine pronoun. Masculine children and adults are to be considered under this heading as well.

4. ^Every immigration officer who interviews minors has completed the EASO modules Interviewing techniques, Interviewing children and Interviewing vulnerable persons and the INS course Interviewing unaccompanied children of 6–12 years.

5. ^Ten out of the thirteen interviews took place in 2017–2019.

6. ^Some of these children had resided in other countries before their arrival in the Netherlands, such as Turkey and Lebanon.

7. ^The older interviews from 2012 and 2013 involved children from DRC and Mongolia.

8. ^This made that the longest interviews took 108 minutes, with a break of 43–45 min.

9. ^Other family members were an aunt, grandmother, brother and father. It is not known why the child who was accompanied by his father was interviewed, because normally accompanied children are only interviewed when 15 years or older. It was decided to keep this interview in the analysis, because it did not substantially differ from the other observed interviews.

10. ^IO: Immigration officer; C: Child.

References

Allsopp, J., Chase, E., and Mitchell, M. (2014). The tactics of time and status: young people's experiences of building futures while subject to immigration control in Britain. J. Refugee Stud. 28, 163–182. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feu031

Beduschi, A. (2017). Vulnerability on trial: protection of migrant children's rights in the jurisprudence of international human rights courts. Boston Univ. Int. Law J. 36, 55–85.

Belloni, M. (2020). Family project or individual choice? Exploring agency in young Eritreans' migration. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 46, 336–353. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1584698

Brittle, R. (2020). A hostile environment for children? The rights and best interests of the refugee child in the United Kingdom's asylum law. Hum. Rights Law Rev. 19, 753–785. doi: 10.1093/hrlr/ngz028

CBS (2022). Alleenstaande Minderjarige Vreemdeling; nationaliteit, geslacht en leeftijd. Available online at: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/82045NED/table?ts=1665416537732 (accessed May 17, 2023).

Cederborg, A. C., Orbach, Y., Sternberg, K. J., and Lamb, M. E. (2000). Investigative interviews of child witnesses in Sweden. Child Abuse Neglect 24, 1355–1361. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00183-6

Chase, E. (2010). Agency and silence: young people seeking asylum alone in the UK. Br. J. Soc. Work 40, 2050–2068. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcp103

Chase, E. (2013). Security and subjective wellbeing: the experiences of unaccompanied youngpeople seeking asylum in the UK. Sociol. Health Illness 35, 858–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01541.x

Chase, E., Rezaie, H., and Zada, G. (2020). Medicalising policy problems: the mental health needs of unaccompanied migrant young people. Lancet 394, 1305–1307. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31821-5

Cleton, L. (2022). Assessing adequate homes and proper parenthood: how gendered and racialized family norms legitimize the deportation of unaccompanied minors. Soc. Polit. 1–24. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxac001

Coram Children's Legal Centre (2017). Migrant Children's Project FACTSHEET: Claiming Asylum as a Child. Available online at: https://www.childrenslegalcentre.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Claiming-asylum-as-a-child-August2017.final_.pdf (accessed May 17, 2023).

Council of Europe (2022). Council of Europe Strategy for the Rights of the Child (2022-2027). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Creutzfeldt, N., Mason, M., and McConnachie, K. (2020). Routledge Handbook of Socio-Legal Theory and Methods. Oxon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429952814

Dahlvik, J. (2017). Asylum as construction work: theorizing administrative practices. Migrat. Stud. 5, 369–388. doi: 10.1093/migration/mnx043

Darmanaki Farahani, L., and Bradley, G. L. (2018). The role of psychosocial resources in the adjustment of migrant adolescents. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 12, 1–11. doi: 10.1017/prp.2017.21

Delfos, M. F. (2009). Luister je wel naar mij? Gespreksvoering met kinderen tussen vier en twaalf jaar oud. Amsterdam: SWP Uitgeverij.

Derluyn, I., Broekaert, E., and Schuyten, G. (2008). Emotional and behavioural problems in migrant adolescents in Belgium. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 17, 54–62. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0636-x

Doornbos, N. (2005). “On being heard in asylum cases: evidentiary assessment through asylum interviews,” in Proof and Credibility in Asylum Law, eds G. Noll and A. Popovic (Leiden: Nijhoff), 103–122. doi: 10.1163/9789047406198_009

Doornbos, N. (2006). Op verhaal komen. Institutionele communicatie in de asielprocedure. Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers.

Drywood, E. (2010). Challenging concepts of the “child” in asylum and immigration law: the example of the EU. J. Soc. Welfare Fam. Law 32, 309–323. doi: 10.1080/09649069.2010.520524

Erickson, S. J., Gerstle, M., and Feldstein, S. W. (2005). Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in paediatric health care settings: a review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 159, 1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1173

European Union (EU) (2021). EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child 2021. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2017). Child-Friendly Justice. Perspectives and Experiences of Children Involved in Judicial Proceedings as Victims Witnesses or Parties in Nine EU Member States. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2018). Children's Rights and Justice. Minimum Age Requirements in the EU. Available online at: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2018/minimum-age-justice (accessed May 17, 2023).

Finnilä, K., Mahlberg, N., Santtila, P., Sandnabba, K., and Niemi, P. (2003). Validity of a test of children's suggestibility for predeicting responses to two interview situations differing in their degree of suggestiveness. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 85, 32–49. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0965(03)00025-0

Flegar, V. (2018). Who is deemed vulnerable in the governance of migration? Unpacking UNHCR's and IOM's policy label for being deserving of protection and assistance. Asiel Migrantenrecht 8, 374–383.

Fox, C., Deakin, J., Spencer, J., and Acik, N. (2022). Encountering authority and avoiding trouble: young migrant men's narratives and negotiation in Europe. Eur. J. Criminol. 19, 791–810. doi: 10.1177/1477370820924627

Gudjonsson, G. H. (2003). The Psychology of Interrogations and Confessions: A Handbook. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. doi: 10.1002/9780470713297

Hedlund, D. (2017). Constructions of credibility in decisions concerning unaccompanied minors. Int. J. Migr. 13, 157–172. doi: 10.1108/IJMHSC-02-2016-0010

Herring, J. (2012). Vulnerability, Children and the Law. In: M. Freeman (ed.) Law and Childhood Studies. Current Legal Issues Volume 14. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 243–263. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199652501.003.0016

Hritz, A. C., Royer, C. E., Helm, R. K., Burd, K. A., Ojeda, K., and Ceci, S. J. (2015). Children's suggestibility research: things to know before interviewing a child. Anuarion Psicol. Jurídica 25, 3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.apj.2014.09.002

IND (2022). Doorlooptijden asielaanvraag. Available online at: https://ind.nl/nl/na-uw-aanvraag/doorlooptijden-asielaanvraag (accessed May 17, 2023).

Iraklis, G. (2020). Move on, no matter what… Young refugee's accounts of their displacement experiences. Childhood 28, 170–176. doi: 10.1177/0907568220944988

Kalverboer, M. E., Zijlstra, A. E., and Knorth, E. J. (2009). The developmental consequences for asylum-seeking children living with the prospect for five years or more of enforced return to their home country. Eur. J. Migrat. Law 11, 41–67. doi: 10.1163/157181609X410584

Keselman, O. (2009). Restricting Participation. Unaccompanied children in interpreter-mediated asylum hearings in Sweden (Ph.D. Thesis., Sweden: Linköping University.

Keselman, O., Cederborg, A.-C., Lamb, M. E., and Dahlström, Ö. (2008). Mediated communication with minors in asylum-seeking hearings. J. Refug. Stud. 21, 103–116. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem051

Keselman, O., Cederborg, A.-C., Lamb, M. E., and Dahlström, Ö. (2010a). Asylum-seeking minors in interpreter-mediated interviews: what do they say and what happens to their responses? Child Fam. Soc. Work 15, 325–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00681.x

Keselman, O., Cederborg, A. C., and Linell, P. (2010b). “That is not necessary for you to know!” Negotiation of participation status of unaccompanied children in interpreter-mediated asylum hearings. Interpreting 12, 83–104. doi: 10.1075/intp.12.1.04kes

Klemfuss, J. Z., and Ceci, S. J. (2012). Legal and psychological perspectives on children's competence to testify in court. Dev. Rev. 32, 268–286. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2012.06.005

Kloosterboer, K. (2009). Kind in het centrum. Kinderrechten in asielzoekerscentra. Den Haag: UNICEF.

Kohli, R. K. S. (2006). The sound of silence: listening to what unaccompanied asylum-seeking children say and do not say. Br. J. Soc. Work 36, 707–721. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bch305

Kovner, B., Zehavi, A., and Golan, D. (2021). Unaccompanied asylumseeking youth in Greece: protection, liberation and criminalization. Int. J. Hum. Rights 25, 1744–1767. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2021.1874936

Lamb, M. E., Hershkowitz, I., Orbach, Y., and Esplin, P. W. (2008). Tell Me What Happened: Structured Investigative Interviews of Child Victims and Witnesses. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9780470773291

Lamb, M. E., and Sim, M. P. Y. (2013). Developmental factors affecting children in legal contexts. Youth Justice 13, 131–144. doi: 10.1177/1473225413492055

Lems, A., Oester, K., and Strasser, S. (2020). Children of the crisis: ethnographic perspectives on unaccompanied refugee youth in and en route to Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 315–335. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1584697

Levensky, E. R., Forcehimes, A., O'Donohue, W. T., and Beitz, K. (2007). Motivational interviewing. An evidence-based approach to counseling helps patients follow treatment recommendations. Am. J. Nurs. 107, 50–58. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000292202.06571.24

Liefaard, T. (2016). Child-friendly justice: protection and participation of children in the justice system. Temple Law Rev. 88, 905–927.

Lundberg, A., and Dahlquist, L. (2012). Unaccompanied children seeking asylum in Sweden: living conditions from a child-centred perspective. Refugee Surv. Quart. 31, 54–75. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hds003

Lundberg, A., and Lind, J. (2017). Technologies of displacement and children's right to asylum in Sweden. Hum. Rights Rev. 18, 189–208. doi: 10.1007/s12142-016-0442-2

Mendola, D., and Pera, A. (2022). Vulnerability of refugees: some reflections on definitions and measurement practices. Int. Migrat. 60, 108–121. doi: 10.1111/imig.12942

Ministry of Justice Security Immigration Naturalisation Service IND Business Information Centre. (2021). Asylum Trends: Monthly Report on asylum applications in the Netherlands. Available online at: https://ind.nl/nl/documenten/03-2022/atdecember2021hoofdrapport.pdf (accessed May 17, 2023).

Rap, S. (2020). The right to information of (un)accompanied refugee children: improving refugee children's legal position, fundamental rights' implementation and emotional well-being in the Netherlands. Int. J. Child. Rights. 28, 322–351. doi: 10.1163/15718182-02802003

Rap, S. (2022a). A test that is about your life: the involvement of refugee children in asylum application proceedings in the Netherlands. Refug. Surv. Q. 41, 298–319. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdac004

Rap, S. (2022b). The right to be heard of refugee children: Views of professionals on the participation of children in asylum procedures in the Netherlands. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 13, 1–16. doi: 10.33134/njmr.442

Saywitz, K., Camparo, L. B., and Romanoff, A. (2010). Interviewing children in custody cases: implications of research and policy for practice. Behav. Sci. Law 28, 542–562. doi: 10.1002/bsl.945

Shamseldin, L. (2012). Implementation of the United Nations convention on the rights of the child 1989 in the care and protection of unaccompanied asylum seeking children: findings from empirical research in England, Ireland and Sweden. Int. J. Childrens Rights 20, 90–121. doi: 10.1163/157181811X570717

Sleijpen, M., Mooren, T., Kleber, R. J., and Boeije, H. R. (2017). Lives on hold: a qualitative study of young refugees'resilience strategies. Childhood 24, 348–365. doi: 10.1177/0907568217690031

Smeets, D. J. H., Bruning, M. R., de Boer, R., and Bolscher, K. G. A. (2020). “Praktijkonderzoek naar Ervaringen met de Civiele Procespositie van Minderjarigen,” in Kind in Proces: Van Communicatie naar Effectieve Participatie. Meijers-reeks no. 335, eds M. R. Bruning, D. J. H. Smeets, K. G. A. Bolscher, J. S. Peper, and R. de Boer (Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers), 161–234.

Smyth, C. (2014). European Asylum Law and the Rights of the Child. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203797297

Stalford, H. (2018). David and Goliath: due weight, the state and determining unaccompanied children's fate. Immigrat. Asylum Nationality Law 32, 258–283.

Strik, T., Ullersma, C., and Werner, J. (2012). Nareis: het onderzoek naar de gezinsband in de praktijk. Asiel and Migrantenrecht 9, 472–480.

Thorburn Stern, R. (2015). “Unaccompanied and separated asylum-seeking minors: implementing a rights-based approach in the asylum process,” in Child-Friendly Justice: A Quarter of a Century of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, eds S. Mahmoudi, P. Leviner, A. Kaldal, and K. Lainpelto (Leiden: Brill Nijhoff), 242–255.

UN Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (UNCMW) and UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (2017). Joint General Comment No. 3 (2017) of the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families and No. 22 (2017) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child on the General Principles Regarding the Human Rights of Children in the Context of International Migration, UN Doc CMW/C/GC/3-CRC/C/GC/22.

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (2005). Treatment of unaccompanied and separated children outside their country of origin. General comment no. 6, UN Doc CRC/GC/2005/6, 1 September 2005.

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (2009). General Comment No. 12. The Right of the Child to be Heard, UN Doc CRC/GC/2009/12.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2012). A Framework for the Protection of Children. Geneva: UNHCR.

Uzozie, A., and Verkade, M. (2016). Volg je dromen tot je niet langer kunt leven: Een retroperspectief onderzoek onder voormalige alleenstaande minderjarige asielzoekers naar toekomstbeleving. Stichting Vrienden van SAMAH.

Van Nijnatten, C., and Jongen, E. (2011). Professional conversations with children in divorce-related child welfare inquiries. Childhood 18, 540–555. doi: 10.1177/0907568211398157

Van Willigen, L. H. M. (2003). Verslag van de quick scan van ‘het kind in het asielbeleid' in de praktijk. Amsterdam.

Werkgroep Kind in AZC/Avance (2021). Monitor: Leefomstandigheden van kinderen in de asielopvang. Signalen, conclusies en aanbevelingen. Den Haag: Werkgroep kind in azc.

Werkgroep Kind in azc/COA/Avance (2018). Leefomstandigheden van kinderen in asielzoekerscentra en gezinslocaties: Rapportage I: conclusies en aanbevelingen. Den Haag: Werkgroep kind in azc.

Wernesjö, U. (2011). Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children: whose perspective? Childhood 19, 495–507. doi: 10.1177/0907568211429625

Keywords: refugee children, asylum procedure, conversation techniques, child-friendly justice, children's rights, the right to be heard

Citation: Rap SE (2023) “Can my mother come?” Asylum interviews with unaccompanied and separated children seeking asylum in the Netherlands. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1191707. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1191707

Received: 22 March 2023; Accepted: 10 May 2023;

Published: 31 May 2023.

Edited by:

Jaya Ramji-Nogales, Temple University, United StatesReviewed by:

Catherine Baillie Abidi, Mount Saint Vincent University, CanadaRafaela Hilário Pascoal, University of Palermo, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Rap. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stephanie E. Rap, cy5lLnJhcEB1dmEubmw=

Stephanie E. Rap

Stephanie E. Rap