- 1Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Geography and Geosciences, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, United States

This perspective piece contends that political-ecological relations are already digital and that feminist analyses help reveal their often-overlooked power relations. We argue that as digital political ecologies research grows in popularity, there is widespread omission and forgetting of key epistemological lessons from feminist political ecologies, such as rooted networks. Here, we remind readers of rooted networks lessons, and we distill them into suggested writing strategies for researchers. Such rooted network writing strategies may seem inefficient and may take up space and time, but as feminist political ecologists concerned with digital relations, we see them as necessary.

Introduction

Over a decade of researching digital political ecologies, we have encountered a persistent acceptance of abstract knowledge coupled with assumptions about networks and scale that are specific to digital technologies. We understand that all knowledge is situated and that writing grounded and contextualized narratives is a form of rigorous analysis that is necessary in digital political ecology. One way to situate and ground our work is through the conceptualization of “rooted networks”: “webs of relation shot through with power” that are rooted in specific territories, spaces, natures and contexts (Rocheleau and Roth, 2007, p. 434). In this perspective piece, we argue that assumptions about digital technologies are exacerbating barriers to “putting rooted networks into practice” (see Cantor et al., 2018, p. 961). As digital political ecologies research grows in popularity, we see the widespread omission and forgetting of key epistemological lessons from feminist political ecologies (FPE), like rooted networks. Here, we remind readers of those lessons, distill them into suggested writing strategies and highlight examples to emulate. How we write matters. Writing choices can help to situate our lively and engaging analyses of digital relations in particular places and power relations.

Assuming the digital

Political ecologists increasingly consider ‘the digital' in their work, because natures are increasingly digitally monitored, controlled, visualized and mediated. From the use of drones in countermapping against land grabs in Indonesia (Radjawali and Pye, 2017), to algorithms monitoring fishing vessel locations to identify incidences of illegal fishing (Drakopulos et al., 2022a), technology is integral to topics typically of interest to political ecologists. This attention to digital technologies is encouraging, but we have observed in the writing of some of our political ecology colleagues (and sometimes ourselves) a treatment of ‘the digital' ontologically as abstract, vast and universal. This is easy to do, as much of digital technology is invisible, abstract and not easily located (Ash et al., 2018): How does a digital message pass from an agricultural extensionist to a farmer's cell phone in Myanmar (Faxon, 2022)? and what kinds of stories, tensions and relationships emerge where undersea fiber-optic cables connecting most transoceanic Internet traffic surface at landings in Papenoo, Tahiti and Vatuwaqa, Fiji (Starosielski et al., 2014; Starosielski, 2015)?1

Much of digital technology also seems immense and often overwhelming and unmanageable (Rose, 2016). For example, recent research by Roberta Hawkins and Jennifer Silver (Hawkins and Silver, under review) on a conservation organization that tags and tracks marine animals and educates and entertains audiences on social media has yielded: publicly available virtual maps for over 300 tagged animals that can be searched by time period, species, and location, along with multi-paged websites, reports, press releases, YouTube videos, a mobile phone app and thousands of Tweets from about 100 different accounts associated with the organization, going back years. As a result of encountering this type and quantity of data, researchers commonly apply quantitative and systematic data analysis methods while avoiding in-depth qualitative analysis (e.g., Ladle et al., 2016; Pincetl and Newell, 2017; Nost et al., 2021).

Assumptions about the digital can also reinforce political ecology research as principally about large-scale conservation, energy production, agricultural technologies or environmental governance, while in our experience, other more mundane and intimate topics receive little attention, such as digital birding communities in neighborhood parks or the use of body-monitoring apps (Nelson et al., 2022). Along these lines, an abstract, written account of the digital runs the risk of portraying technology as neutral or apolitical (Nost, 2022). This may happen more often in work that does not present the experiences of the individual producers and users of the technologies under exploration or that fails to situate researchers in their work. We notice that conclusions drawn in digital political ecology research lean into ‘universal' explanations and tend toward techno-dystopic conclusions where technology reproduces already existing power relations (e.g., capitalist exploitation) (Leszczynski, 2020; Elwood, 2021; Nelson et al., 2022). This leaves little space for different lived-experiences and for nuanced examination of the possibilities and potential that some digital technologies may foster.

Rooted networks matter

Trained as feminist political ecologists, we can't help but notice a disjuncture between these assumptions about the digital and our own understandings of “rooted networks” in political ecology. FPE emphasizes that political ecological relations are not neutral and universal but are in fact gendered, classed, racialized and shaped through other markers of social difference, and that this in turn affects material outcomes such as labor roles, access to resources, environmental responsibilities and subjectivities, and knowledge production (Rocheleau et al., 1996; Elmhirst, 2011; Nightingale, 2011, 2013; Buechler and Hanson, 2015; Harcourt and Nelson, 2015; Harcourt et al., 2022). FPE reminds us that environmental knowledge is situated, rooted and partial, necessitating attention to whose voices and lived experiences inform our understandings of the world (Rocheleau and Roth, 2007; Mollett and Faria, 2013; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, 2019). FPE “[i]nterrogates power assemblages, undertakes multi-scalar analyses from the body to the planet, investigates counter-topographies of connections across spaces, scales, places and species, and is explicit about its praxis” (Sultana, 2021, p. 161).

Specifying different meanings of “networks” within FPE and digital political ecologies is necessary here. As Cantor et al. (2018, p. 963) explain regarding network metaphors in Actor Network Theory (ANT) and related discussions preceding and informing the rooted networks concept, “the term ‘network' only distantly resembled earlier usage by computer scientists who popularized it to model technological relationships in mechanical terms.” Specifically (Alida Cantor and colleagues, p. 964) argue:

The concept of rooted networks differs from most network-focused theories in that it is explicitly place-based, emphasizing the ways in which particular territories situate and ground socio-ecological relations. It recognizes apparently discrete territories as emergent from, and produced by, networked relations between complex assemblages of disparate things and beings…[and] asserts that human and non-human interactions transpire in material dimensions in specific places. At the same time, territories are conceptualized as more than discrete spatial polygons. They are relational, particular, material, and manifest across multiple scales.

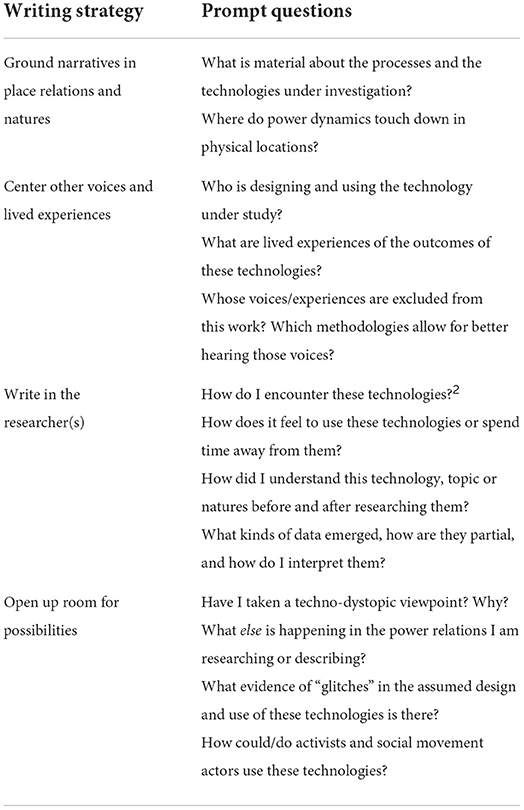

Rooted networks and FPE more broadly offer many insights of relevance to digital political ecologists. We argue elsewhere for a feminist digital natures (FDN) approach that “combines feminist epistemologies and practices with an understanding that digital technologies mediate and co-produce many natures” (see Nelson et al., 2022). Here, we focus on writing as a key actionable and longstanding feminist strategy. As scholars we are always making decisions about writing – choosing words, tone, structure, style and voice – often while trying to figure out what to include or exclude to meet word limits, publisher requirements, and reviewer demands. Recent attention to the importance of stories in political ecological work highlights what particular writing choices can do analytically and politically in communicating complex points (Harris, 2022). Below, we offer four suggested writing strategies and highlight examples to emulate. These examples are not necessarily from digital political ecology but from related fields and they are not all mobilizing rooted networks concepts, however they illustrate how our work can become more situated, and lively through writing choices. In Table 1 we also offer questions to prompt researchers to get started (or keep going!) in situated and grounded writing.

Ground narratives in place relations and natures

Rooted networks research in FPE brings abstract versions of network thinking and analysis back down to Earth through grounding these processes in territories, places and natures aiming to “articulate the territoriality and materiality of networks as assemblages, which may be simultaneously rooted and mobile” (Cantor et al., 2018, p. 959). This is a common practice in ethnographic writing, but we see it less in research that engages with the digital. When digital analyses are grounded in specific places and natures, readers can understand the simultaneously material and virtual aspects of digital technologies, the socio-ecological influences and implications of them and as a result, the nuanced power dynamics underway.

This is exemplified in Ingrid Nelson's (Nelson, 2016a, 2017) work in the miombo woodlands of central Mozambique, where she applies a much broader and more longitudinal definition of “technology” (e.g. kinds of “tools” or practices) in her work; only some of which are digital and many of which are simultaneously quite “old” and contemporary. Part of understanding contested land, forest and kin relations amidst repeated development and environmental intervention requires paying attention to both longstanding embodied practices such as daily sweeping of the dirt around the home (Nelson, 2016b), which asserts many temporal layers of presence in a place, and digital ‘technologies' brought by outside loggers, rural extensionists and development aid groups such as GPS devices for resolving boundary disputes and digital video-recordings of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) meetings about land deals (Nelson, 2016a). The narrative descriptions in her work allows readers to ground what could be abstract socio-ecological and technological relations in practices, places and forests. Doing this kind of rooted network analysis requires methods that trace these relations through ethnography, in-depth interviews, reading, listening, community engagement, being in a forest, and engaging technologies with critical attention and curiosity.

Center other voices and lived experiences

One of the goals of FPE and rooted networks is to “conduct analyses that unearth multiply-situated knowledges within networks” (Cantor et al., 2018: 959). We have noticed that digital political ecology work does not seem to share this goal. Not only are multiple voices and knowledges overlooked, but we commonly see the exclusion of any human participants. This is accomplished by referring to the work done by institutions (e.g., WWF), corporations (e.g., Alphabet Inc.), reports, maps, data or algorithms, often missing the fact that people constitute these entities. Stories that engage them in the practices of technological design and use can bring the lived experiences of digital political ecologies to the forefront for readers and ground an analysis in material, embodied and emotional ways. Researchers often collect these stories through in-depth interviews, event or digital ethnography and critical discourse analysis.

Sandra McCubbin's (2020) work on the killing of Cecil the Lion by an American trophy hunter in Zimbabwe, and subsequent online reaction is a good example of weaving together multiple voices on an issue. Here, we read the voices of conservationists and field biologists who digitally tracked Cecil; local wildlife guides and social media users who protested the killing online, garnering global attention; an American celebrity distraught at Cecil's death and a Zimbabwean author surprised and puzzled by the outraged Americans who seemed “to care more about African animals than about African people” (Nzou, 2015 cited in McCubbin, 2020, p. 199). What McCubbin's approach offers is a nuanced look at global political ecological power dynamics, concepts like spectacle and ultimately the “mutability” (2020, p. 201) of digital political ecology practices and processes.

Another example is Eric Nost's (Nost's, 2022) work analyzing how specific people (e.g., scientists and planners) actually use ecosystem modeling data to make decisions for coastal restoration planning in Louisiana, USA. Through a detailed analysis, with multiple participant views, Nost illustrates how various components of data infrastructures are (de)politicized, providing insights into the production of data for environmental planning. Finally, researchers such as Jessica McLean (McLean, 2020) have written accounts of the lived experiences of activists engaging digital technologies for social justice as they confront systemic power relations.

Write in the researcher(s)

Work on rooted networks is grounded in feminist theory, one key element of which is that there is no view from nowhere (Haraway, 1988). As researchers we have a particular perspective on our work – even when that work is digital and seemingly abstract. Reflexive narrative writing is one effective way to include the researcher in the work while also describing data, such as a study site, and performing elements of data analysis through writing. We are not advocating for a total centering of the researcher, but rather a need to refuse assumed neutrality. As Pamela Moss and Kathryn Besio (Moss and Besio, 2019, p. 313) argue regarding auto-methods in particular,

In writing their lives, researchers…can, for example, use their own life to organize, bound, and shape their inquiry. Or they can analyze their own lives alongside the experiences of the people whom they have talked with or interviewed. Or they can trace pathways of power by recounting encounters they have had with institutions….auto-methods [are] long-standing feminist research approaches that treat researchers' own stories and experiences as data.

One example of this is at a plenary lecture3 Where Political Geography Specialty Group Plenary at the virtual Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers in 2022. where political ecologist Farhana Sultana (Sultana, 2022) included excerpts from words she wrote as a student, “… mainly for the haunting of the words today, how it resonates with contemporary climate politics, and reflecting how the personal is always political.” This writing grounds her engagement with concepts like climate colonialism through bringing in the researcher's embodied, emotional and situated lived experiences. Similarly, Robyn Longhurst (Longhurst, 2013, 2016) writes that her own experiences connecting with her children over Skype inspired her research interests and her in-depth examination of others' experiences mothering through digital technology.

Researchers studying digital technologies also pursue auto-methods and reflexive writing to describe their experiences using apps. Lauren Drakopulos et al. (Drakopulos et al., 2022b) use narrative vignettes to describe their use of citizen science apps. The vignettes describe the app design and function but also include research experiences and emotions navigating these technologies. More thoroughly, Jacqueline Gaybor (Gaybor, 2022), used diary writing to chronicle her use of a menstrual cycle tracking app for over a year, allowing her to reflect on the disembodied production of bodily knowledge and the effects the app had on her own assessment of whether or not her body was “normal.” In all these examples, including the voices of the researchers allows for the political-ecological relations and technologies under study to be grounded and contextualized in particular people, places, relations and lived-experiences.

Open up room for possibilities

Our final suggestion for a more feminist ethos in writing digital political ecologies is an effort to move away from the tendency to see digital research through a techno-dystopic lens or to interpret all power dynamics as hierarchical or deterministic (as critiqued by Ash et al., 2018; Leszczynski, 2020). Sarah Elwood (Elwood, 2021, p. 210) encourages a feminist relational ontology that may reveal how digital technologies can encourage “thriving otherwise.” She reminds us that: “[D]igital objects, praxes and ways of knowing always contain possibilities for unanticipated forms of agency, subjectivity, or sociospatial relations” (Elwood, 2021, p. 211), meaning that they must be considered in ontologically open ways where creativity, re-assembly, resistance and “glitch politics” (see Russell, 2012) are always possible. This aligns well with the social movement orientation of rooted networks and its generative goals of coalition building and collaborative problem solving (Cantor et al., 2018).

Eben Kirksey et al. (Kirksey et al., 2018) offer this type of openness in their analysis of a project that tagged Cockatoo birds with numbered leg bands and encouraged residents of Sydney, Australia to report bird sightings on Facebook. The authors describe the agency of the birds in their relations with the humans who feed them on their balconies and the importance of the Facebook page as a “lively forum for discussions about the exploits of particular birds as well as cockatoo behavior and ecology.” They present some of the potential harms of the project (e.g., the potential culling of locatable nuisance birds) but they focus the article on the potential of the project to generate multi-species friendships (Kirksey et al., 2018).

If political-ecological relations are co-constituted by digital technologies (among other things), then researchers in this field must pay more attention to the moments where these relations are constituted in ways that do not reinscribe existing and dominant power relations, for example, moments where activists use digital technologies to disrupt common representations of nature (Hawkins and Silver, 2017) or environmental management or resource distribution decisions (Checker, 2017).

Discussion

Writing rooted networks into digital political ecologies involves: including contextual elements like place relations and environments, centering multiple voices allowing for more nuanced and situated analyses, including the researcher in the work, and opening up room for alternative possibilities. These writing strategies take up space. Sometimes, as writers we feel that we cannot justify this nuanced, multi-vocal and narrative approach. We often prefer the short-cut and would rather summarize and move on.

Writing places, people, researchers and possibilities into digital political ecologies also takes time: to collect, to craft and weave, to read and interpret. In our current cultures of speed, where publishers nudge us to promote our work via brief Tweets or we are pushed to prioritize quantity over quality, it may seem as though we don't have the time or space for rooted networks. We advocate otherwise. Rooted networks can be a form of slow scholarship (Mountz et al., 2015). Following these suggested writing strategies whenever possible can make our writing on digital political ecologies more engaging, clear and accessible to readers.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewer for their detailed and thorough feedback. Any remaining errors or omissions are our own.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^There are efforts to ground digital political ecology in material environments, often through a focus on the energy involved in digital processes (for example, see Lally et al. (2022) on the material impacts of Bitcoin mining in Chelan County, Washington).

2. ^Consider using or adapting the app-walk through method (Light et al., 2018) to guide a closer reflection on using and experiencing various technologies.

3. ^Political Geography Specialty Group Plenary at the virtual Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers in 2022.

References

Ash, J., Kitchin, R., and Leszczynski, A. (2018). Digital turn, digital geographies? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 42, 25–43. doi: 10.1177/0309132516664800

Buechler, S., and Hanson, A-M. S. eds (2015). A Political Ecology of Women, Water and Global Environmental Change. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315796208

Cantor, A., Stoddard, E., Rocheleau, D., Brewer, J., Roth, R., Birkenholtz, T., et al. (2018). Putting rooted networks into practice. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 17, 958–987.

Checker, M. (2017). Stop FEMA now: social media, activism and the sacrificed citizen. Geoforum 79, 124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.004

Drakopulos, L., Nost, E., Hawkins, R., and Silver, J. (2022b). “A shark in your pocket, a bird in your hand(held): the spectacular and charismatic visualization of nature in conservation apps,” in The Routledge Handbook for the Digital Environmental Humanities, eds C. Travis, D. Dixon, L. Bergmann, R. Legg, A. Crampsie (New York, NY: Routledge), 303–316. doi: 10.4324/9781003082798-26

Drakopulos, L., Silver, J.J., Nost, E., Gray, N., and Hawkins, R. (2022a). Making global oceans governance in/visible with Smart Earth: the case of Global Fishing Watch. Environ. Plan. E: Nat Space 5. doi: 10.1177/25148486221111786

Elmhirst, R. (2011). Introducing new feminist political ecologies. Geoforum 42, 129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.006

Elwood, S. (2021). Digital geographies, feminist relationality, black and queer code studies: thriving otherwise. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 45, 209–228. doi: 10.1177/0309132519899733

Faxon, H. O. (2022). Welcome to the digital village: networking geographies of agrarian change. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. doi: 10.1080./24694452.2022.2044752

Gaybor, J. (2022). “Of apps and the menstrual cycle: a journey into self-tracking,” in Feminist Methodologies: Experiments, Collaborations and Reflections, eds W. Harcourt, K. van den Berg, C. Dupuis, and J. Gaybor (New York, NY: Springer), p. 65–82. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-82654-3_4

Haraway, D. J. (1988). Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem. Stud. 14, 575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066

Harcourt, W., and Nelson, I. L. eds (2015). Practicing Feminist Political Ecologies: Moving Beyond the ‘Green Economy'. London: Zed Books. doi: 10.5040/9781350221970

Harcourt, W., van den Berg, K., Dupuis, C., and Gaybor, J. eds (2022). Feminist Methodologies: Experiments, Collaborations and Reflections. Palgrave Macmillan Open Access. Available online at: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-030-82654-3.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022).

Harris, L. M. (2022). Towards enriched narrative political ecologies. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 5, 835–860. doi: 10.1177/25148486211010677

Hawkins, R., and Silver, J. J. (2017). From selfie to #sealfie: nature 2.0 and the digital cultural politics of an internationally contested resource. Geoforum 79, 114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.06.019

Hawkins, R., and Silver, J. J. (under review). Following Miss Costa: Examining digital natures through a shark with a Twitter account. Digital Geographies.

Kirksey, E., Munro, P., van Dooren, T., Emery, D., Maree Kreller, A., Kwok, J., et al. (2018). Feeding the flock: wild cockatoos and their facebook friends. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 1, 602–620. doi: 10.1177/2514848618799294

Ladle, R. J., Correia, R. A., Do, Y., Joo, G. J., Malhado, A. C., Proulx, R., et al. (2016). Conservation culturomics. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14, 269–275. doi: 10.1002/fee.1260

Lally, N., Kay, K., and Thatcher, J. (2022). Computational parasites and hydropower: a political ecology of Bitcoin mining on the Columbia River. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space. 5, 18–38. doi: 10.1177./2514848619867608

Leszczynski, A. (2020). Glitchy vignettes of platform urbanism. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space. 38, 189–208. doi: 10.1177./0263775819878721

Light, B., Burgess, J., and Duguay, S. (2018). The walkthrough method: an approach to the study of apps. New Media Soc. 20, 881–900. doi: 10.1177/1461444816675438

Longhurst, R. (2013). Using skype to mother: bodies, emotions, visuality, and screens. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 31, 664–679. doi: 10.1068/d20111

Longhurst, R. (2016). Mothering, digital media and emotional geographies in Hamilton, Aotearoa New Zealand. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 17, 120–139. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2015.1059477

McCubbin, S. G. (2020). The Cecil Moment: celebrity environmentalism, Nature 2.0, and the cultural politics of lion trophy hunting. Geoforum 108, 194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.10.015

McLean, J. (2020). Changing Digital Geographies: Technologies, Environments and People. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mollett, S., and Faria, C. (2013). Messing with gender in feminist political ecology. Geoforum 45, 116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.10.009

Moss, P., and Besio, K. (2019). Auto-methods in feminist geography. GeoHumanities 5, 313–325. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2019.1654904

Mountz, A., Bonds, A., Mansfield, B., Loyd, J., Hyndman, J., Walton-Roberts, M., et al. (2015). For slow scholarship: a feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the Neoliberal University. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 14, 1235–1259.

Nelson, I. L. (2016a). “Responding to technologies of fixing ‘nuisance' webs of relation in the Mozambican Woodlands,” in The Palgrave Handbook on Gender and Development: Critical Engagements in Feminist Theory and Practice, ed W. Harcourt (New York, NY and London: Palgrave Macmillan), 251–261. doi: 10.1007/978-1-137-38273-3_17

Nelson, I. L. (2016b). Sweeping as a site of temporal brokerage: linking town and forest in Mozambique. Crit. Anthropol. 36, 44–60. doi: 10.1177/0308275X15617303

Nelson, I. L. (2017). Gendered orphan kits, authority, power and the role of rumor in the woodlands of Mozambique. Gender Place Cult. 24, 1263–1282. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2017.1378624

Nelson, I. L., Hawkins, R., and Govia, L. (2022). Feminist digital natures. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space. doi: 10.1177/25148486221123136

Nightingale, A. J. (2011). Bounding difference: intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 42, 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.03.004

Nightingale, A. J. (2013). Fishing for nature: the politics of subjectivity and emotion in Scottish inshore fisheries management. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 45, 2362–2378. doi: 10.1068/a45340

Nost, E. (2022). Infrastructuring “data-driven” environmental governance in Louisiana's coastal restoration plan. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 5, 104–124. doi: 10.1177/2514848620909727

Nost, E., Gehrke, G., Poudrier, G., Lemelin, A., Beck, M., Wylie, S., et al. (2021). Visualizing changes to US federal environmental agency websites, 2016–2020. PLoS ONE 16, e0246450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246450

Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. (2019). Visualizing politics: a feminist political ecology and participatory GIS approach to understanding smallholder farming, climate change vulnerability, and seed bank failures in Northern Ghana. Geoforum 105, 109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.014

Nzou, G. (2015). “In Zimbabwe, We Don't Cry for Lions”. The New York Times, 4 August. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/05/opinion/in-zimbabwe-we-dont-cry-for-lions.html?searchResultPosition=2 (accessed June 29, 2022).

Pincetl, S., and Newell, J. P. (2017). Why data for a political-industrial ecology of cities? Geoforum 85, 381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.002

Radjawali, I., and Pye, O. (2017). Drones for justice: inclusive technology and river-related action research along the Kapuas. Geogr. Helv. 72, 17–27. doi: 10.5194/gh-72-17-2017

Rocheleau, D., and Roth, R. (2007). Rooted networks, relational webs and powers of connection: rethinking human and political ecologies. Geoforum 38, 433–37. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.10.003

Rocheleau, D., Thomas-Slayter, B., and Wangari, E. eds (1996). Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experience. London: Routledge.

Rose, G. (2016). Rethinking the geographies of cultural ‘objects' through digital technologies: Interface, network and friction. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 40, 334–351. doi: 10.1177/0309132515580493

Russell, L. (2012). Digital dualism and The Glitch Feminist Manifesto. The Society Pages, 10 December. Available online at: https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/12/10/digital-dualism-and-the-glitch-feminism-manifesto/ (accessed July 17, 2022).

Starosielski, N. (2015). The Undersea Network. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv11smhj2

Starosielski, N., Loyer, E., and Brennan, S. (2014). Surfacing. Available online at: www.surfacing.in (accessed September 20, 2022).

Sultana, F. (2021). Political ecology I: from margins to center. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 45, 156–165. doi: 10.1177/0309132520936751

Keywords: digital political ecologies, feminist political ecology, narrative, power relations, writing

Citation: Hawkins R and Nelson IL (2022) Where are rooted networks in digital political ecologies? Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:989387. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.989387

Received: 08 July 2022; Accepted: 06 October 2022;

Published: 01 November 2022.

Edited by:

Muriel Côte, Lund University, SwedenReviewed by:

Seema Arora-Jonsson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenCopyright © 2022 Hawkins and Nelson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ingrid L. Nelson, aWxuZWxzb25AdXZtLmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Roberta Hawkins1†

Roberta Hawkins1† Ingrid L. Nelson

Ingrid L. Nelson