- Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

Chieftaincy succession conflicts are a near-ubiquitous phenomenon in Ghanaian Chiefdoms. While many studies have investigated the causes and implications of such conflicts, the extent to which traditional and central authorities collaborate in the management of chieftaincy succession conflicts in Ghana is largely understudied. This is the gap in the literature that this study attempted to fill. The study was situated within the frameworks of the Collaborative Leadership Theory. The Exploratory Sequential variant of the mixed method approach was adopted for the study where 16 key informants were recruited using expert purposive sampling technique and 99 others recruited for a survey using stratified and simple random sampling techniques. The unit of analysis was the Bole chieftaincy succession conflict management team. Data were solicited around the level of representation of traditional and central authorities on the team, the roles assigned to each member, the levels of commitment of each member, and the significance of the roles played by each member at the various stages of conflict management. The analysis of the data revealed that there were some levels of collaboration at the preparatory stage of the mediation process but this was less so at the main stages of the mediation process. The study therefore recommended that the state, through the National Security Council, may liaise with the National House of Chiefs to fashion out better ways of collaborating in conflict management, from the initial stages to the final stages, so as to completely resolve chieftaincy conflicts that are often disruptive and destructive.

Introduction

Succession conflicts transcend many historical epochs and have spurted and ebbed at varied moments in many monarchical societies since antiquities (Barnes, 2018; Van Bockhaven, 2020). Many scholars agree that the transferral of traditional power from one leader to another is likely to cause instability in monarchies (Chrimes, 2013; Bérenger and Simpson, 2014; Bezio, 2016). From the well-established monarchies of England, Finland, Japan, through the autocratic dynasties of North Korea and Saudi Arabia, the Benin Empire in Southern Nigeria, the Bajia and Bagbo Kingdoms in Sierra Leone to the Asante Kingdom in Central Ghana, chieftaincy succession conflicts are not completely alien to any (Gunaratne, 2005; Anderson, 2014). In Medieval Europe, the death of a King was often characterized by the moments of security uncertainties until the leading circles of the society had assembled and elected a leader (Derluguian and Earle, 2010; Bérenger and Simpson, 2014). This was minimized much later at the onset of the modern period when Europeans adopted a primogeniture succession arrangement where the eldest son of a dead King succeeded him spontaneously (Kokkonen and Sundell, 2014; Bezio, 2016).

In Africa, it is indubitable that chieftaincy is among one of the longest surviving traditional institutions across the continent (Owusu-Mensah et al., 2015; Mawuko-Yevugah and Attipoe, 2021). The institution of chieftaincy in African societies is as old as the societies themselves (Mawuko-Yevugah and Attipoe, 2021). Empires such as Kush, Punt, Carthage, and Aksum in North Africa, The Great Zimbabwe, Mapunbubwe, Mutapa, Butua, and Maravi in the South and Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Kanem-Bornu, and the Hausa States in the West were created between the fourth and eleventh century (Getachew, 2019; Lentz, 2020). The social and political organization of these empires depicts the quality of leadership exhibited by their kings and chiefs even before the advent of colonialism in Africa (Getachew, 2019). By the end of the fifteenth centuries, many empires and kingdoms had risen in Africa such as the Sultanate of Sennar, Saadi dynasty, Sultanate of Darfur, Alauite dynasty, and Mohammed Ali dynasty in the North of Africa, Merina, Rozwi, Ndwendwe, Zulu, and Xhosa kingdoms in Southern Africa, and Gonja, Dagbon, Mamprusi, Dahomey, Kong, and the Sokoto Caliphate in the West of Africa (Wesseling, 2015; Duindam, 2016). Most of these kingdoms still exist and remain relevant till date even though much of their relevance was largely decimated during colonialism and at the onset of modern states.

Ghana, then referred to as Gold Coast, was colonized by the British from 1844 to 1957 (Balakrishnan, 2020). At the demise of colonialism, two levels of government emerged; the central and traditional governments (Apter, 2015; Honyenuga and Wutoh, 2018). In modern Ghana, chiefs, apart from performing their traditional functions, serve as links between the central government and their people (Doran, 2017; Honyenuga and Wutoh, 2018). Chieftaincy remains very important to most societies in Ghana. The position of chiefs is failsafe under the fourth republican constitution (1992). Article 270(1) of the 1992 constitution supports the institution of chieftaincy, together with its traditional councils as established by customary law and usage. Article 277 of the 1992 constitution describes a chief as someone who comes from the appropriate family and lineage and has been validly nominated, elected or selected, and installed as a chief or queen mother in accordance with existing customs. Chiefs in Ghana wield a lot of powers. They have great control over the people and resources within their jurisdiction. It is therefore not surprising that people fight to get installed as chiefs.

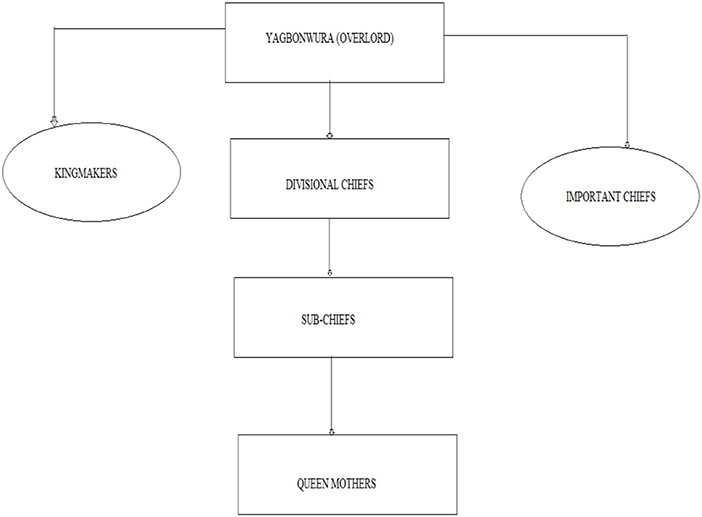

The traditional governance structure in Bola is similar to that of the ancient empires of Ghana, Mali, Songai, and Kanuri in the then Southern Sudanese states. This is not strange as the Gonja is a part of the Madingo group that broke away from the Songai Empire and formed their own kingdom after the empire became weak and disintegrated. The traditional governing structure of the Gonja kingdom is headed by Yagbonwura, the overlord of the Gonja kingdom, who is the final arbiter of disputes in the kingdom. He works closely with the kingmakers and a group of chiefs who are considered important chiefs. The kingmakers are responsible for training and appointing chiefs and the important chiefs work closely with Yagbonwura to maintain peace and stability in the kingdom. The kingdom of Gonja has five main divisions, which are headed by divisional chiefs. These divisional chiefs exercise power within their jurisdiction, but are subordinate to the overlord. The divisional chiefs are also assisted by the sub-divisional chiefs. The sub-divisional chiefs are appointed by the divisional chiefs and help to maintain law and order in their divisions. Disputes within the division are first resolved by the sub-divisional chiefs. If they cannot do so, they refer them to the divisional chiefs, and if the parties are not satisfied with the decision of the divisional chiefs, they can appeal these decisions to the Yagbonwura, who has the final say in such matters. At the very bottom of the hierarchy are the Queens Mothers, who must come from the Yagbonvura lineage. The Queen Mothers are responsible for giving wise counsel to the chief and his elders, uniting all women and overseeing social conditions in the community. The traditional governance structure of the Gonja kingdom is shown in Figure 1.

The Gonja confederacy is located in the Savannah Region; one of the nascent regions carved out in 2016 in further pursuance of decentralization by the state. The Gonja people are believed to have immigrated into Ghana from the Mali-Songhai Empire. According to Goody (2018), the Gonjas were led out of the Mali-Songhai Empire by Landa Wam to the present day Bole and Sawla districts between 1546 and 1576. Landa Wam reigned for 19th years from 1595 to 1615 when he was overcome by a protracted illness. After his dead, Amoah took over and also ruled Gonjas between 1596 and 1615 before handing over to Lamtalimu, the father of Ndewura Jakpa in 1634 (Tampuri, 2016; Yaro et al., 2020). When Lamtalimu abdicated for his son, Ndewurajakpa in 1675 due to ill health, the latter saw the need to expand the territories of the Gonja people. He embarked on an expansionist war where he conquered the Safalba, Brifor, and Vagla people around the present day Sawla area (Goody, 2018). He later moved eastward and engaged the Dagombas, the Nawuris, and the Chumburus in the present day areas of Salaga, Daboya, Damango, and Buipe (Tampuri, 2016; Yaro et al., 2020). From these, he established seven divisions and installed his sons in each as divisional chiefs while he served as their overlord (Stacey, 2016). These divisions included Wasipe, Kpembe, Bole, Tulwe, Kong, Kandia, and Kusawgu (Stacey, 2016; Tampuri, 2016; Yaro et al., 2020). They have survived till today and have chiefs in each of them who are still answerable to the Yagbonwura as the overlord of Gonjaland (Bediako, 2017). With the exception of Kong and Kandia, any of these divisional chiefs can ascend to the paramount throne depending on the succession arrangements in place. Kong and Kandia were expelled from the kingship due to an alleged conspiracy with a foreigner to fight the Chief of Bole at that time (Yaro et al., 2020). The succession to these divisions has created huge instability within the Gonja kingdom (Tampuri, 2016).

There is a chieftaincy succession arrangement in Gonjaland that was made in 1930, which provides that successions to the Yagbon throne (overlord of Gonjaland) be rotated among the five divisions and successions to the divisional thrones should be rotated within various gates (royal families) in each division (Bediako, 2017). Yaro et al. (2020) observed that the arrangements so contained in the 1930 agreement at Yapei have made it possible for the kingmakers to know which division is next to ascend the Yagbon throne and which gate is next to the other at the divisional levels. The defect in this arrangement, Tampuri (2016) notes, is that no provision was made for the selection of a particular family member who will represent the gate during divisional successions. A gate usually consists of so many family members, when there is a vacancy; the selection of a specific family member who will ascend the throne becomes a problem. Goody (2018) believes this created the current stalemate in the Bole traditional area.

Ibrahim et al. (2019) observed that the modern history of Gonja has had no records of disagreement about who becomes the Yagbonwura. Succession disputes are rather pervasive at the divisional and sub-divisional levels ((GTC, 2019)). One of the most violent divisional successions conflict ever fought in Gonjaland was that of the Jinapor and the Lebu gate in the Buipe Traditional Area over who becomes the Buipewura. The Jinapor gate members would not submit to the decision of the then Yagbonwura that, apparently, went against them. Even when the decision was later upheld by the Judicial Committee of the Regional House of Chiefs, a body constitutionally mandated to preside over chieftaincy related matters, the Jinapor gate would have nothing to do with it. The case was later taken to the Supreme Court but subsequently settled out of it in 2010. Similar conflicts had occurred in Kpembe and Wasipe divisions. Bole traditional area now hosts much of the succession conflicts. The Gonja Traditional Council (GTC, 2019) attributes this to the lack of consensus among the kingmakers over who has the right to install chiefs in the Bole traditional area. The 1930 chieftaincy rotation arrangements in Yapei mandate the divisional chiefs to install sub-divisional chiefs but also make provision for an appeal to the Yagbonwura should there be any cases of abuse of power by the divisional chiefs (GTC, 2019).

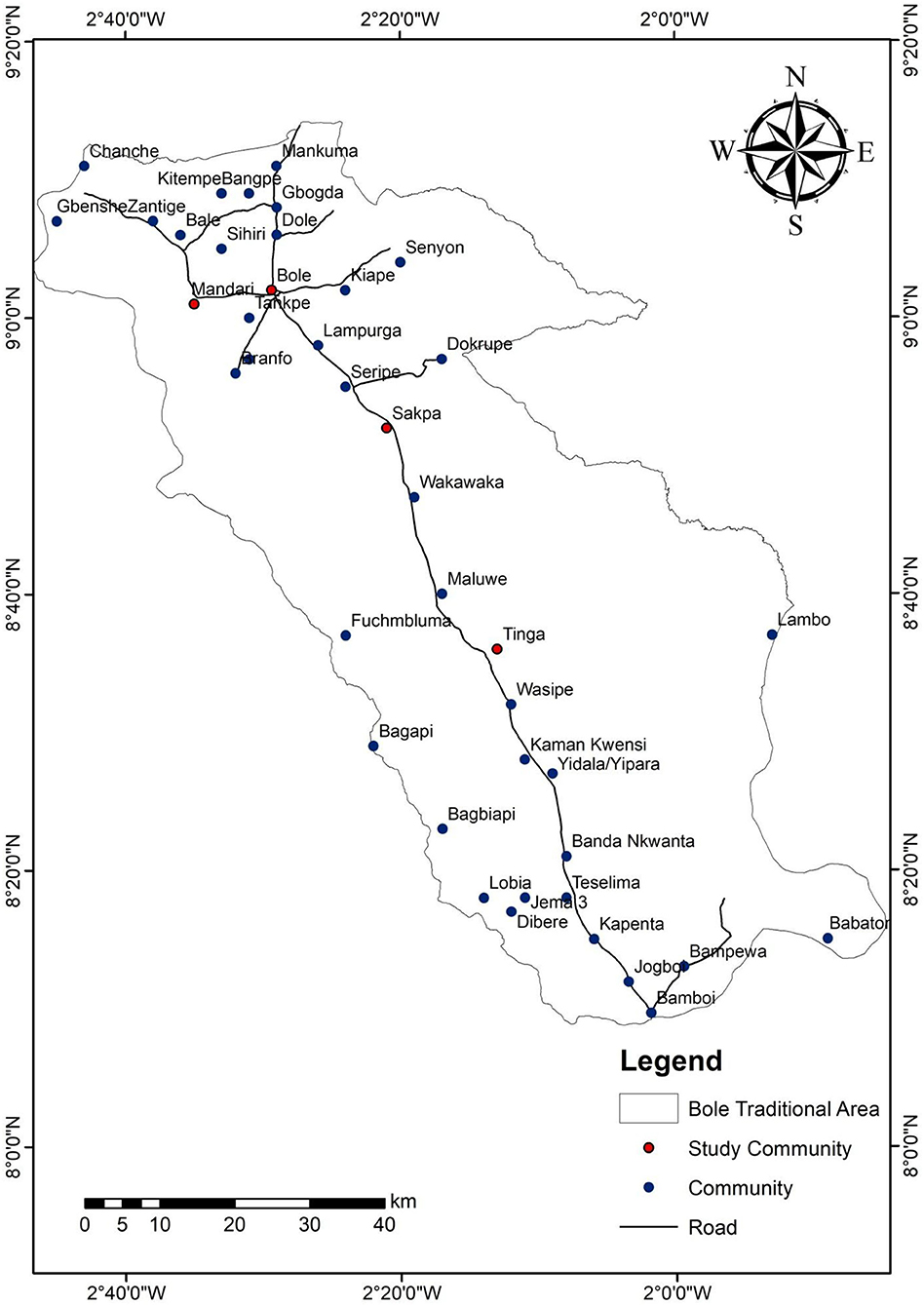

Figure 2 shows the map of Bole traditional Area. Mandari, as shown in Figure 2 is closely located to Bole Township. The Mandari throne is one of the most coveted thrones within the Bole traditional area because, by a local succession arrangement, the Mandariwura (sub-chief) automatically succeeds the Bolewura (Divisional Chief) anytime the latter deceases (Tampuri, 2016). The Mandari throne became vacant in 2013. Then, the Bolewura installed one Issahaku Abdulai Kant as the new Mandariwura (GTC, 2019). His choice of a Mandariwura was, however, contested by some members of the Wulasi gate who were next in line to supply a consensus candidate for the position of a Mandariwura (Goody, 2018). The aggrieved persons went to the Yagbonwura who eventually voided the installation of Issahaku Abdulai Kant and, instead, appointed Bukari Abudu who was the eldest person from the Wulasi gate as the legitimate Mandariwura (GTC, 2019). This situation segmented the people of the Bole traditional area into two; those who supported the decision of the Yagbonwura (overlord of Gonja kingdom) and those against the decision. This later created a stalemate in Mandari as the two chiefs were installed contemporaneously (Yakubu, 2017). With the intervention of the Regional Security Council, the imminent violence that hovered over the town was prevented and the case referred to the Judicial Committee of the Regional House of Chiefs (Yakubu, 2017). In December 2017, the Judicial Committee ruled that the Bolewura did nothing wrong because by the provisions of the 1930 chieftaincy successions arrangement in Gonjaland, the power to install sub-divisional chiefs rests with the divisional chiefs and the divisional chiefs were to be installed by the overlord of Gonjaland (Ashahadu, 2018).

On the 31 May 2017, Bolewura Mahama Pontongprong II passed on. His death reignited a new wave of tension within the Bole traditional area. Soon after his funeral rites were performed, the Yagbonwura moved in to install a divisional chief for Bole (GTC, 2019). This was contrary to an internal arrangement within the Bole traditional area, which requires that a Bolewura must first of all pass through the Mandari skin (Ashahadu, 2018). In pursuance to this, Issahaku Abdulai Kant also installed himself as a Bolewura during which violence erupted and two people were killed with several others sustaining various degrees of injuries (Goody, 2018). The Regional Security Council, in its characteristics manner, moved in to restore calm. The two were asked to stay away from the Palace until the case is resolved. As it stands, Bole traditional area has no substantive divisional chief, the conflict has been repressed but it is yet resolved.

Ghana has institutions for conflict management such as the District, Regional, and National Security Councils, the Regional and National Houses of Chiefs and the Judiciary. Most of these institutions are state institutions except for the Regional and National Houses of chiefs which are traditional institutions. This study therefore seeks to ascertain the level of collaboration between the central and traditional authorities in the management of the chieftaincy succession conflict in Bole traditional area. The succession conflict has attracted considerable academic attention. Bediako (2017) looked at the causes of chieftaincy succession conflicts in Bole traditional area. Yakubu (2017) investigated the causes of the conflict and its impact in Bole traditional area. Tampuri (2016) assessed the chieftaincy succession conflict in Mandari and how it affects development in the entire Bole traditional area. All of these researchers did some studies on the conflict but the extent to which central and traditional authorities collaborate to resolve succession conflicts in Bole traditional area has not been fully explored. This is the gap the study attempts to fill. The study raises a number of questions; what is the composition of the Bole conflict management team? What are the areas of collaboration between traditional and central authorities? To what extent has the traditional and central authorities collaborated in managing the Bole chieftaincy conflict? Answers to these questions will provide a framework for policy formulation that will encourage interdisciplinary approach to conflict management in Ghana.

Theoretical review

The study adopted the theory of Collaborative Leadership to provide a deductive analytical framework for the study. Collaborative Leadership theorists express the view that leadership yields better results when it involves all the significant elements in a society or organization in making major decisions (Finch, 1977). Such leadership approach is characterized by shared vision, interdependence, and mutual respect and a cross-fertilization of ideas. Decisions are neither top-down nor bottom-up. Decision-making adopts an integrative approach where all the actors and sections become unanimous in decision-making (Lawrence, 2017). In the context of this study, it means that in conflict management, traditional and central authorities need to collaborate and play complementary roles that will address the issues that keep the conflicts alive.

While some researchers argue that traditional authorities have lost or are gradually losing their relevance in modern democratic states (Albrecht and Moe, 2015; Baldwin, 2016; Rosenbaum, 2018), a number of studies around the world confirm the sustainability, legitimacy, and relevance of the institution of “traditional” governance as embodying the preservation of rural people's culture, traditions, customs, and values (Granderson, 2017). Organizations such as the World Bank and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) concerned with development seek opportunities to engage the rural sector when implementing poverty reduction programs by working directly with traditional authorities (Makinta et al., 2017).

Traditional governance predates colonialism and represents early forms of social organization and local governance, especially in rural Africa (Amsler, 2016). The rest of the world has gone through eras of monarchical rule in one form or another. In countries such as France, Russia, Mozambique, and Uganda, the institution of traditional leadership has either been completely abolished or an attempt has been made to do so. The socialist government in Mozambique banned chiefdoms after independence in 1975 and created new governance structures (Biitir and Nara, 2016). Despite this, chiefs continued to play an important roles in the countryside. The powerful kingdom of Buganda was abolished by the 1967 Ugandan constitution after the Buganda king was ousted in 1966. Despite attempts to abolish or make it irrelevant by modern states, the fact that this institution still exists today, even in countries where it has been abolished, demonstrates its relevance and resilience (Kolk and Lenfant, 2015).

Alongside the existence of traditional leadership, institutions are parallel “modern” states or new forms of social organization with enormous powers to make rules, enforce them, adjudicate, reward, and punish. The whole debate about traditional government and local governance is not about whether traditional and modern systems of governance compete with each other, but about how to integrate the two systems more effectively to better serve citizens in terms of representation and participation, service delivery, social and health standards, peace and security, and access to justice.

Scholars generally agree on two main forms of traditional government. These two main classifications are the centralized political system (cephalic societies) and acephalic societies or what is described as a “decentralized” political system. Cephalic societies have a centralized authority, administrative apparatus, and judicial institutions where stratification by wealth, privilege, and status corresponds to the distribution of power and authority (Boakye and Béland, 2019). The Gonjas, Ashantis, and the Dagombas are examples of cephalic societies. Acephalic societies, on the other hand, in their pure form lack centralized authority, administrative apparatus, and judicial institutions, and there is no clear division by rank, status, or wealth. Tallensi and Dagaabas are examples of acephalic societies. In such societies, the lineage system is predominantly used to regulate and govern their people. Despite this simple political system, there is usually a central figure such as a Tindana whom the people respect and look up to for spiritual support (Bukari, 2016). Essel (2021) suggests that pre-colonial indigenous administration in the cephalic societies of Ghana was bureaucratic as there were highly formalized systems or procedures within the chiefdom hierarchy.

The traditional bureaucracy had elements of decentralization and citizen participation (Lutz and Linder, 2004). For example, in the Ashanti kingdom, traditional administration was highly decentralized and based on citizen participation. There was a hierarchy of positions from the Asantehene, who was the overall head, to the village chief, who enjoyed considerable autonomy in the chieftaincy hierarchy. In addition, in the traditional bureaucracy, there was ample opportunity for adult participation in decision-making, as issues such as village projects and business decisions were often decided in open forums, through debate and consensus building. The modern state is believed to be highly centralized and bureaucratic (Debrah et al., 2016). Boakye and Béland (2019) argue that African political culture values consensus building and social solidarity. Clearly, in pre-colonial times, the institution of chiefdoms was a mechanism for maintaining social order and stability. Consequently, the functions of the chief were a fusion of various roles such as military, religious, administrative, legislative, economic, and cultural (Bergius et al., 2020). As a form of integration, cephalic and acephalic societies were assimilated into the colonial governance structure and used to achieve the objectives of the British colonial government.

According to Barry (2018), successful and effective conflict resolution and local development projects require effective cooperation between all stakeholders. It follows from the above that traditional authorities are custodians of culture and important agents in the development process. There is, of course, a renewed interest in indigenous knowledge and institutions, which is in line with the current advocacy for a minimalist state and an “enabling approach” as conditions for good governance in a period of structural adjustment and public sector reform. Under pressure from civil society and donor organizations, governments are being urged and in fact obliged to reduce their role to the level that their dwindling or limited resources and capacities allow (Crawford et al., 2017). This implies decentralizing the governance structure, promoting genuine participation and involving a wide range of non-state actors and stakeholders, including traditional institutions and leadership (Owusu-Mensah et al., 2015). Consequently, if culture is important and traditional authorities are its custodians, then suffice it to say that in conflict resolution and transition, traditional authorities are indispensable in both processes. Their importance becomes even more relevant in chieftaincy succession conflict because such conflicts are rooted in existing traditions and customs.

Methods

The study area

The research was carried out in Bole traditional area of Savannah Region. Bole traditional area covers the areas of Bole, Sawla, Tuna, Kalba, and Mandari. The traditional area has a population of 61,593 people representing 2.5% of the total population of the Savannah Region (GSS, 2014). Bole has more men (51.4%) than women (46.4%). Of this population 41.8% can read and write while 58.2% are illiterates (GSS, 2014). Many of them engage in one economic activity or the other except those who are sick or very old. The main economic activities in Bole are farming, trading, charcoal burning, and small-scale mining. Many others are also engaged in the formal sector as doctors, nurses, teachers, and administrators. In total, 59.6% of the population are farmers, 13.2% are into sales and service provision, 8.2% are into craft and similar trade, and 4.8% are nurses, teachers, or administrators (GSS, 2014). Bole traditional area has about ninety-four chieftaincy titles that are occupied by people from the three chieftaincy gates at various locations (GTC, 2019). The three chieftaincy gates in Bole traditional area are Wulasi from the Safope family, Kiape from the Jagape family, and Sikri from the Denkeripe family.

Research design

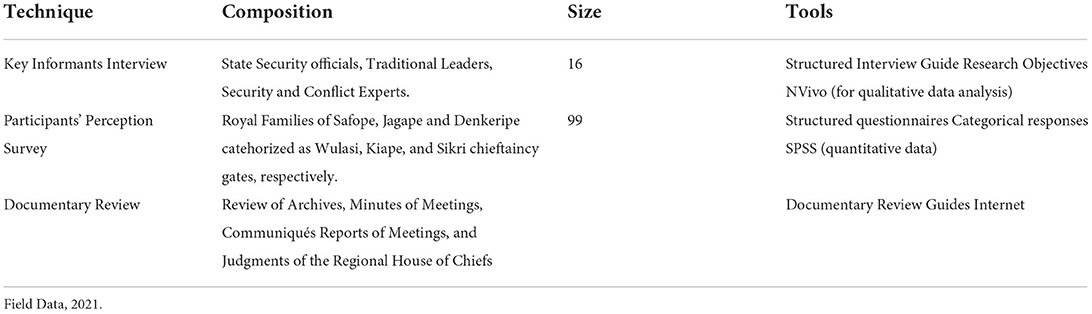

The study adopted an exploratory sequential mixed method design to gather comprehensive data on the level of collaboration between the central and traditional authorities in the management of the Bole chieftaincy succession conflict. The mixed method was adopted not just because it enabled the collection of a more comprehensive data but also because it provided a means of cross-validating field data before final interpretations and this made the overall quality of the study stronger than using either qualitative or quantitative approaches in isolation. First of all, sixteen key informants were selected using Expert Purposive sampling technique for personal interviews. They were selected because they have had general first-hand details of the conflict and the level of collaboration that had taken place between the central and traditional authorities in resolving the conflict. The interview with each participant lasted for an hour and was guided by an interview protocol which contained the research objectives, the data collection plan, and the purpose of the research. Data were solicited around the demographic characteristics of the interviewees, levels of collaboration at the stages of: identification of the causes of the conflict, negotiations, solution finding, implementation of resolutions, assessment of impact of implementation, and carving pathways for desired future relations in Bole traditional area. The results of the qualitative analysis were used to develop instruments for the collection of quantitative data.

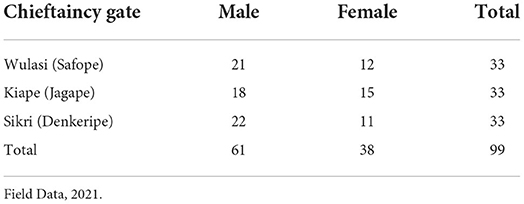

For the quantitative aspect, ninety-nine participants were recruited for a perception survey using stratified and simple random sampling techniques. The recruitment was limited to members of the three royal families in Bole traditional area because they could better speak about the conflicts since they were directly affected by it. Respondents were first of all divided into three strata based on their chieftaincy gates (royal families). A simple random sampling technique was then used to randomly select 33 participants from each stratum. Questionnaires were used to solicit data from this category of participants. The questionnaire was structured in five sections labeled A–E. Section “A” solicited data on the demographic characteristics of respondents such as sex, age, chieftaincy gate, and years of residence in Bole traditional area. Section “B” contained 9 items that solicited data on the level of collaboration of traditional and central authorities in identifying the root causes of the conflict. Section “C” contained 8 items that solicited data on level of collaboration during the negotiation stage. Section “D” solicited data on the levels of collaboration between traditional and central authorities during the implementation of resolutions and section “E” had five items that solicited data on the level of collaboration during the assessment of the impact of implemented resolution and designing of a desired future state. The interview guides and the questionnaires were adapted from previous studies of Lawrence (2017) and Akinwale (2010), which also investigated the role of traditional and modern leadership in conflict resolution in Malawi. The items that measured the levels of involvement of both traditional and central authorities, the role they both played, and the stages at which they collaborated were adopted and modified to fit the current study. This was sent out to several colleagues who previewed the items and offered suggestions that helped in the recalibration of the instrument to better fit this study. To further ensure the validity of the instruments, the instruments were pre-tested using 15 participants before the actual data collection. Challenges that were encountered at the pre-testing state were addressed before the main data collection.

A documentary review of various unpublished documents that had relevant information about the management of the conflict was undertaken, including a review of minutes of meetings of the District and Regional Security Councils, Regional House of Chiefs, and Gonja Traditional Councils. Communiqués issued by various stakeholders such as the Gonja Youth Association, The Gonja Traditional Council, and Bole Traditional Council were also reviewed. A review of evaluation reports from the National Security Council and the Regional Security Council was carried out. Judgments from the Judicial Committee of the Regional House of Chiefs were also carefully studied. Basically, the data that were sought from the documentary review were on the management of the conflict and the level at which traditional authorities were involved in the management of the conflict. The results of the interviews were transcribed into a text report and analysed alongside the documentary information using thematic content analysis. The documents and the transcribed interviews were read through severally to enable the authors get familiar with the contents. The researchers coded the data by highlighting and coloring sections of the documents and developing shorthand labels to describe their contents. These codes enabled the researchers to gain a condensed overview of the main points and common meanings that recurred throughout the documents. After that, patterns in the generated codes were identified and themes built by combining the codes. These themes were reviewed and mapped against the transcribed text and the documents that were reviewed. Few of the themes were broken down and others combined to make the themes more meaningful and useful. The refined themes were then named before final interpretation. A summary of the data collection instruments and profile of participants is provided in the Tables 1, 2, respectively.

Our unit of analysis was the team that managed the conflict in Bole traditional area. We measured the composition of the team at various stages of conflict management. From the literature, we identified six stages of conflict management: identification of causes, bringing conflicting parties to negotiation tables, brainstorming for possible solution, implementing solutions arrived at through consensus, assessing the impact of the implementation, and designing a desired future state (Dimas and Lourenço, 2015; Taras and Ganguly, 2015; Stavenhagen, 2016; Soliku and Schraml, 2018). We asked whether there were both traditional and central leaders at each of the stages, the numeric composition of each group at every stage, the role each played, the levels of significant attached to these roles, the level of commitment shown, and the level at which each group felt integrated during any of the processes.

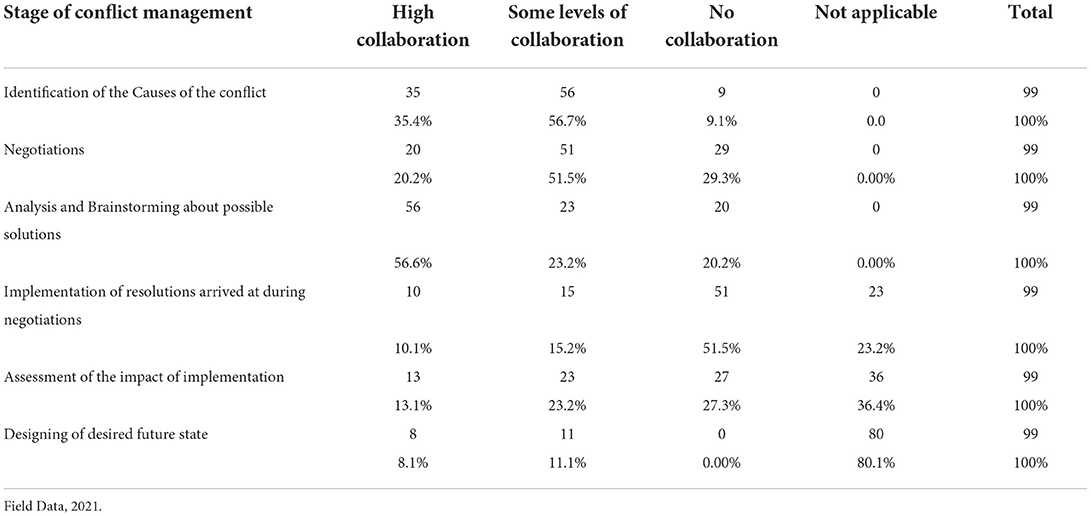

We first of all protected our respondents' identities by coding all sixteen key informants with the first sixteen English alphabets: A–P. This means that respondent 1 was coded A, 2 B through to the sixteenth respondent who was coded P. In searching for the responses that answered our research questions, we categorized and named the codes base on the objectives of the study. While a few other themes emerged in the areas of collaboration, majority of the responses pointed to the fact that collaboration between the two authorities was in the areas of identifying the causes of the conflict, bringing conflicting parties to negotiation, engaging the people through a collective process of searching for solutions and sometimes, implementing the resolutions that were made at the negotiation stage but less collaboration was reported in the areas of assessing the impact of implementing the resolution and carving a pathway for desired future relations. Descriptive statistics was used to analyze quantitative data using SPSS software. Data from the field were edited and entered into the software which was later use to generate patterns and frequencies from participants' responses. These were presented in a table for easy understanding.

Results

Participants who participated in the survey reported collaboration in the areas of identification of the causes of the conflict and negotiations but reported less collaboration in the implementation of resolutions and no collaboration in assessing the impact of the implementation and designing of a desired future state.

As shown in Table 3, majority of the participants indicated that there were some levels of collaboration at the stage of identifying the causes of the conflict (56.7%). In total, 35.4% reported that there was high collaboration between the two authorities in identifying the root causes of the conflict. This was corroborated by the responses from the Key Informant Interviews (KIIs). In total, twelve of the key informants reported that there was strong collaboration between the central and traditional authorities at this stage of conflict management because both were involved equally in terms of numbers and the roles played in the procedures and processes that led to the identification of the root causes of the problem. Respondent D who was a sub-chief explains it this way:

“The Committee that was set up to investigate the chieftaincy conflict consisted of both traditional and local authorities. Apart from this, the constitution even makes provision that such conflicts be settled by the Regional House of Chiefs which consists of mainly traditional rulers. The Regional House of Chiefs worked hand in hand with the Regional Security Council to identify the root causes of the conflict.”

This indicates that there was a certain level of collaboration when it came to identifying the causes of the conflict. Respondent F who was a member of the District Security Council also explained:

“There is that collaboration between the state and traditional authorities. Some of them are members of the District Security Council. In planning the best way to resolve the conflict, key traditional leaders were selected to sit with the Military and other persons concerned with national security issues to cross-fertilize ideas. To me, this is high level collaboration.”

In total, four of the key informants, however, denied that there was any collaboration at this stage of conflict management. They were of the view that there have not been any serious efforts at managing the conflict. Respondent K who was a divisional chief explained:

“Whenever the conflict escalates, the Military is sent to repress violence and the case referred to the Judicial Committee of the Regional House Chiefs where it remains largely silent until violence erupts or becomes imminent.”

In terms of assembling the conflicting parties for negotiation, 51.5% of the respondents indicated that there were some levels of collaboration, 29.1% of the total respondents reported that there was no any form of collaboration at all. In total, 20.2% of the participants, however, affirmed that there was high collaboration between the two authorities when it came to negotiations. This was corroborated by the key informants. In total, ten of them were of the view that all stakeholders were involved either directly or through their representatives when it came to negotiation. Respondent F who was a conflict expert explained:

“One of the most critical stages in conflict management is bringing the conflicting parties to a negotiation table. What I know about this conflict is that the state tries to bring as many stakeholders to the negotiation table as possible and these include traditional authorities. The difficulty here is that there seems to be a power tussle between the Yagbonwura and the Bolewura and these are very significant authority figures in Gonjaland. Sometimes their personal difference distorts the lines of neutrality and makes negotiations difficult. But in any case there is always an engagement of the traditional authority by the state at the levels of negotiations.”

At the stage of analyzing and brainstorming for possible solutions during conflict management, participants reported that there was a high level of collaboration (56.6%). In total, 23.2% reported that there were some levels of collaboration but 20% reported that there was no collaboration at all. The high reports of high level collaboration and some levels of collaboration are indicative of the perception of majority of the respondents that there is a certain level of collaboration in this area. This was confirmed by some of the keys informants. In total, thirteen of them reported that in most cases, brainstorming for solution during the negotiation stage is bottom-up as people believe it is a traditional conflicts and solution can only be found within the traditions and customs of the people. Respondent G who was a member of the National Security explained:

“When it comes to proffering solutions to a conflict, the state only facilitates the discussions but most of the suggestions emanate from the locals themselves who are often represented by their chiefs, clans' heads and family heads. So at this stage, I can tell you that we experience high collaboration due to the bottom up approach that is needed for managing these kinds of conflicts.”

The documentary review also showed that this stage of management was dominated by traditional leaders as the state largely monitored and facilitated the process.

When it came to the implementation of resolutions agreed during negotiations, low levels of collaboration were reported (high = 10.1; low = 15.2%). Majority of the respondents reported that there was no collaboration (51.5%). In total, 23.2% reported that it was not applicable, meaning that no such activity has taken place from both the central and traditional authorities. In total, nine of the key informants also reported that there was hardly any collaboration in the implementation and six others reported that sometimes, the resolution is never implemented at all that is why the conflict becomes intractable. Responded H who was a divisional chief explained:

“To be sincere, sometimes due to some political factors, implementing the resolutions becomes difficult. In this era of political opportunism, it becomes difficult to implement some of the resolutions because by doing that a certain political party may lose some support. So the implementation is often abandoned in the hands of Traditional Authorities who may be less willing or lack resources to implement.”

Respondent L who was a clan head held a different view.

“When it comes to chieftaincy succession conflicts, we try to avoid a win-lose outcome so we devise creative ways of getting a win-win outcome this makes implementation easy, collaborative and systematic. Every stakeholder is involved because each side has to give up something so as to gain something.”

At the stage of assessing the impact of the implemented resolutions, 36.4% of the participants reported that there has not been such an activity by both the central and traditional authorities. In total, 27.3% of them reported that there was no collaboration. The key informants also reported that no assessment has been done yet since the last resolution because the conflict seems to spurt and ebb by varied triggers at varied moments. Respondent Q who was a security chief explained:

“At the level of assessment, to be sincere we have not gotten there yet. The conflict is dynamic. Today you think a solution has been found tomorrow it is something different. When the Judicial Committee of the Regional House of Chiefs ruled that the Bolewura had the right to install any of the sub-divisional chiefs within his jurisdiction, we thought that was an end to the conflict until there was yet again a succession struggle when the Bolewura died and the Yagbonwura moved in to install a new one. The tricky nature of it is that the Yagbonwura exercised his authority but the Bole chiefdom also expects any Bolewura to have passed through the Mandari Skin. So these are some of the reasons why we cannot assess any implemented resolution because none has survive over a year.”

In terms of designing a desired future state for the conflicting parties, 80.1% of the participants who took part in the survey reported that there has not been any activity from both sides in that regard. This was corroborated by all key informants. They explained that the conflict itself has not been resolved, so no issues around designing a desired future succession plan that will forestall subsequent conflicts as regards succession in Bole traditional area has ever come up for discussion. Respondent B who was a security expert explained as this:

“We are yet to get there. The conflict itself has not been resolved. Attempts at peaceful negotiations failed so it was referred to the Judicial Committee of the Regional House of Chiefs. They ruled in 2020 that the Mandariwura was validly installed and that it was not within the jurisdiction of the Yagbonwura to install sub-chiefs. The 1930 chieftaincy succession arrangement in Gonjaland, however, provides that the Yagbonwura installs divisional chiefs who in turn install sub-chiefs. The Yagbonwura has installed a chief for the Bole Traditional Area. The problem is that the divisional chief who has been installed by the Yagbonwura did not pass through the Mandari skin as it is required by and has been the custom in the Bole Traditional Area. The Mandariwura, who per the Bole local arrangement, is qualified to ascend the Bole throne is not the pick of the Yagbonwura. The case has been refereed back to the Judicial Committee of the Regional House of Chiefs. So as it stands, we have not resolved the conflict yet when we do we will design a desired future state.”

Documentary evidence also confirmed that the conflict management efforts in Bole traditional area is yet to get to this stage, which is considered by many conflict experts as the final stage in conflict management.

Discussions

The study revealed that the traditional and central authorities worked together in identifying the causes of the chieftaincy succession conflict in Bole traditional area, bringing conflicting parties to negotiation table and brainstorming for possible solutions. This corroborates the finding of Bolaji and Gariba (2020) when they found that there was high collaboration between the central and traditional authorities during the management of the Andani-Abudu chieftaincy succession conflict in Dagbon Kingdom. Tseer (2017) also found that the two authorities worked together in managing the conflict between the Bimobas and the Konkombas in Bunkpurugu Yunyoo. This also falls within the frameworks of the Collaborative Leadership Theory that was adopted as a deductive analytical framework for the study. The collaboration between the central and traditional authorities incorporates both customary and contemporary dynamic approaches to conflict management, thereby making resolutions more integrative, consensual and binding as posited by the Collaborative Leadership Theory. The finding that there was a collaboration at the initial stages of conflict management in Bole, however, contradicts that of Akinwale (2010) when he reported low collaboration in the identification of the root causes of the Igbo-Yoruba conflict in Lagos. They found that a top-down approach was adopted by the state and this excluded traditional authorities. They, therefore, concluded that traditional authorities in Nigeria are often undermined when it comes to conflict resolution especially where the central authority intends to manipulate sentiments to derive political benefits. The variance of their finding with that of this study may lie in the nature of the two conflicts. The Igbo-Yoruba conflict was an inter-ethnic conflict while the Bole conflict is an intra-ethnic one. The methodologies adopted could also explain the variance in the findings. While this study adopted a mixed method approach with a sample size of 99, the study of Akinwale (2010) recruited a limited sample size of 19 using a qualitative approach.

This study also found that there was limited collaboration at the later stages of managing the conflict as both the central and traditional authorities played isolated roles or no roles at all. In terms of implementation of resolutions, this study found that there was less collaboration and fewer efforts from the state due to some political reasons. In this sense, traditional authorities had always solely struggled to implement resolutions in the face of scarce resources. This has often led to poor implementation and a relapse of the succession conflict. This finding is consistent with those of Akinola and Uzodike (2018) and Nyadera (2018) who made similar findings in South Sudan and Nigeria, respectively. Amandong (2021) reports a similar situation in Cameroun but adds, in his conclusion, that even though implementations of resolutions in Cameroun were low, it was more about unsatisfied negotiations from the conflicting parties than it was about political considerations.

In terms of assessing the impact of the implementation of the resolution, the study also found that there has not been an assessment of the impact and the final stage of conflict management which is designing a desired future state has also not been considered just yet. This is consistent with the findings of Duursma (2020) who reports that in many cases of conflict management in Africa, management efforts end at negotiations. Implementation, assessment of implication, and designing a desired future state are the stages that conflict managers in Africa hardly pay attention to. For instance, Henseler et al. (2018) found a low level of collaboration between traditional and central authorities in Mozambique in terms of implementing resolutions. They adopted a qualitative approach involving key traditional leaders and central government officials responsible for conflict management and peace building and found that traditional leaders indicated a lack of appreciation from government officials in conflict management, but expressed a willingness to work with them on everything from training in Western conflict management procedures to building partnerships to improve peace and security in rural areas. They further found that traditional leaders provided culturally appropriate approaches, which were linked to the indigenous interpretative model of conflict resolution held by many Mozambicans. They, therefore, concluded that the central government in Mozambique was less willing to work with traditional leaders to manage conflicts at all stages.

Limitations

The study was conducted when the conflict was yet to be completely resolved. This would have affected some of the data that were collected to measure the level of collaboration between the central and traditional authorities at various stages of conflict management. Due to the sensitive nature of the conflict, the researchers were denied access to some of the documents which would have provided useful information about the levels of engagements, number of traditional and central leaders on the conflict management team, roles played, and the significance of each role in the management of the chieftaincy succession conflict in Bole. Despite these limitations, the study made unique contributions to the literature on conflict management. The assessment of the level of collaboration at various stages of conflict management remains a unique contribution of this study to the available literature on chieftaincy succession conflict management. Exclusive to this study also is the finding that conflict management in Bole traditional area had often stalled at the implementation stage with no impact assessment and no plan for the prevention of a relapse of the conflict or emergence of new variants. Methodologically, the study uniquely combines a qualitative approach with a quantitative approach which provided a window for the use of integrative data analysis tools making the overall results stronger and more valid than using a single approach in isolation.

Conclusion

The study set out to investigate the levels of collaboration between central and traditional authorities in the management of the chieftaincy succession conflict in Bole traditional area. Using a mixed method approach, the study found that there were certain levels of collaboration at the early stages of conflict management even though implementation of resolutions that were arrived at during the negotiations was difficult. Conflict management in many parts of Ghana had often stalled at the implementation stage. This is partly because of a lack of political will; driven by the parochial interests of political actors. Another reason is also that once the initial violence is repressed by the Military and curfews imposed, it is often assumed that the conflicts have ended until they resurface again in a more destructive manner. Chieftaincy conflicts, in particular, have the tendency of easily assuming a near intractable nature because wrong imageries are of the other factions that are passed down to the next generation. Younger people are told of how the other group is wicked, greedy, intolerable, and constitute an imminent danger that must be dealt with. This accumulates and translates into out-group hatreds over time. Trust between the two factions who must continually live together in the same kingdom erodes incrementally until it gets to the lowest levels. At such instances, any trigger is enough to spark off violent conflictual behaviors. To effectively resolve chieftaincy succession conflicts, an integrated approach is needed. Traditional authorities are closer to their people compared to the central authorities. They, however, lack the resources and expertise that may be needed in managing conflicts in modern states. This, therefore, requires that both the central and traditional authorities work hand-in-hand in managing chieftaincy succession conflicts. An integrated approach where more people are involved in the management processes at all stages is needed, so that resolutions that are arrived at during negotiations would be consensual and binding.

Practical implications

The study found that there was a certain level of collaboration between traditional and central authorities in managing the Bole chieftaincy succession conflict. This means that such efforts can be strengthened through the continuous engagement of traditional leaders by the state and its agencies during conflict management.

It was also found that the implementation of resolutions that were made during negotiations was often abandoned. This means that the National Security Council may become more involved in the implementation of such resolutions to complete the management process so as to prevent relapses or emergence of new variants of the same conflict.

It was further revealed that that no efforts were made by both traditional and central authorities in assessing the impact of implemented resolutions. This means that the National Security may liaise with the National House of Chiefs to put mechanisms in place that will assess the impact of implemented resolutions and determine what actions need to be taken to ensure that the conflict is completely resolved.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TT reviewed literature and did the analysis while MS dealt with the methodology. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the undying support of Persius Aaliebemwin Yabelang who assisted by proofreading the work and making relevant suggestions which improved the quality of the study. We also acknowledge the assistance of Alhaji Nurideen Ibrahim and Ikima Hardi Edward who assisted in distributing and retrieving some of the survey questionnaires. We are equally indebted to the reviewers whose comments and suggestions have enriched the quality of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer OS declared a shared affiliation with the authors to the handling editor at the time of review.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akinola, A. O., and Uzodike, U. O. (2018). Ubuntu and the quest for conflict resolution in Africa. J. Black Stud. 49, 91–113. doi: 10.1177/0021934717736186

Akinwale, A. A. (2010). Integrating the traditional and the modern conflict management strategies in Nigeria. Afr. J. Conflict Resol. 10, 81–106. doi: 10.4314/ajcr.v10i3.63323

Albrecht, P., and Moe, L. W. (2015). The simultaneity of authority in hybrid orders. Peacebuilding 3, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/21647259.2014.928551

Amandong, E. M. (2021). Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) hybrid in cameroon as a form of legal protection for consumers of defective products. Brawijaya Law J. 8, 66–81. doi: 10.21776/ub.blj.2021.008.01.04

Amsler, L. (2016). Collaborative governance: Integrating management, politics, and law. Public Adm. Rev. 76, 700–711. doi: 10.1111/puar.12605

Ashahadu, S. H. (2018). Analysing the chieftaincy succession dispute in mandari and its socio-economic implications on the development of the Bole traditional area (Ph. D. Thesis). University of Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana.

Balakrishnan, S. (2020). Of debt and bondage: From slavery to prisons in the Gold Coast,. 1807–1957. J. Afr. Hist. 61, 3–21. doi: 10.1017/S0021853720000018

Baldwin, K. (2016). The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa: Cambridge University Press.

Barnes, S. T. (2018). Patrons and Power: Creating a Political Community in Metropolitan. Lagos: Routledge.

Barry, C. (2018). Peace and conflict at different stages of the FDI lifecycle. Rev. Int. Pol. Econ., 25, 270–292. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2018.1434083

Bérenger, J., and Simpson, C. (2014). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273–1700. London, UK: Routledge.

Bergius, M., Benjaminsen, T. A., Maganga, F., and Buhaug, H. (2020). Green economy, degradation narratives, and land-use conflicts in Tanzania. World Dev. 129, 104850. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104850

Bezio, K. M. (2016). Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignty. London, UK: Routledge.

Biitir, S. B., and Nara, B. B. (2016). The role of Customary Land Secretariats in promoting good local land governance in Ghana. Land Use Policy 50, 528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.10.024

Boakye, P. A., and Béland, D. (2019). Explaining chieftaincy conflict using historical institutionalism: A case study of the Ga Mashie chieftaincy conflict in Ghana. Afr. Stud. 78, 403–422. doi: 10.1080/00020184.2018.1540531

Bolaji, M., and Gariba, M. A. (2020). The Scramble for the Partition of the Northern Region of Ghana. Afr. Sociol. Rev. 24, 75–104. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26918066#metadata_info_tab_contents

Bukari, K. N. (2016). A concomitant of conflict and consensus: case of a chieftaincy succession in Ghana. Peace Conflict Stud. 23, 55–83. doi: 10.46743/1082-7307/2016.1282

Chrimes, S. B. (2013). English Constitutional Ideas in the Fifteenth Century. Cambridge, UK Cambridge University Press.

Crawford, G., Botchwey, G. J. C., and Politics, C. (2017). Conflict, collusion and corruption in small-scale gold mining: Chinese miners and the state in Ghana. Commonwealth Comp. Pol. 55, 444–470. doi: 10.1080/14662043.2017.1283479

Debrah, E., Alidu, S., and Owusu-Mensah, I. (2016). The cost of inter-ethnic conflicts in Ghana's Northern Region: the case of the Nawuri-Gonja Conflicts. J. Afr. Stud. Peace Buid. 3, 77–93. doi: 10.5038/2325-484X.3.1.1068

Derluguian, G., and Earle, T. (2010). “Strong chieftaincies out of weak states, or elemental power unbound,” in Troubled Regions and Failing States: The Clustering and Contagion of Armed Conflicts. Bradford, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Dimas, I. D., and Lourenço, P. R. (2015). Intragroup conflict and conflict management approaches as determinants of team performance and satisfaction: two field studies. Negotiation Conflict Manage. Res. 8, 174–193. doi: 10.1111/ncmr.12054

Doran, S. (2017). “James VI and the English succession,” in James VI and I (London, UK: Routledge), 39–56.

Duindam, J. (2016). Dynasties: A global history of power, 1300–1800. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Duursma, A. (2020). African solutions to African challenges: the role of legitimacy in mediating civil wars in Africa. Int. Organ. 74, 295–330. doi: 10.1017/S0020818320000041

Essel, E. A. (2021). The role of traditional leaders in governance structure through the observance of Taboos in Cape Coast, Kumasi and Teshie Societies of Ghana. Int. Relat. 9, 122–135. doi: 10.17265/2328-2134/2021.03.003

Finch, F. E. (1977). Collaborative leadership in work settings. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 13, 292–302. doi: 10.1177/002188637701300305

Goody, J. (2018). The over-kingdom of Gonja. In West African kingdoms in the nineteenth century (London, UK: Routledge), 179–205.

Granderson, A. (2017). The role of traditional knowledge in building adaptive capacity for climate change: Perspectives from Vanuatu. Clim. Soc. 9, 545–561. doi: 10.1175/WCAS-D-16-0094.1

GSS (2014). 2010 Population Census. Availabe online at: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/storage/img/marqueeupdater/Census2010_Summary_report_of_final_results.pdf (accessed on February 20, 2022).

GTC (2019). Succession Disputes in Gonjaland. Available online at: https://gh.opera.news/tags/gonja-traditional-council (accessed on February 22, 2022).

Gunaratne, S. A. (2005). Asian philosophies and authoritarian press practice: a remarkable contradiction. Javnost Public 12, 23–38. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2005.11008886

Henseler, J., Müller, T., and Schuberth, F. (2018). “New guidelines for the use of PLS path modeling in hospitality, travel, and tourism research,” in Applying partial least squares in tourism and hospitality research. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Honyenuga, B. Q., and Wutoh, E. H. (2018). Ghana's decentralized governance system: the role of Chiefs. Int. J. Public Leadership 17, 38–62. doi: 10.1108/IJPL-01-2018-0005

Ibrahim, M. G., Adjei, J. K., and Boateng, J. A. (2019). Relevance of indigenous conflict management mechanisms: evidence from Bunkpurugu-Yunyoo and Central Gonja Districts of Northern Region, Ghana. Ghana J. Dev. Stud. 16, 22–45. doi: 10.4314/gjds.v16i1.2

Kokkonen, A., and Sundell, A. (2014). Delivering stability—primogeniture and autocratic survival in European Monarchies 1000–1800. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 108, 438–453. doi: 10.1017/S000305541400015X

Kolk, A., and Lenfant, F. J. (2015). Cross-sector collaboration, institutional gaps, and fragility: the role of social innovation partnerships in a conflict-affected region. J. Public Pol. Market. 34, 287–303. doi: 10.1509/jppm.14.157

Lawrence, R. L. (2017). Understanding collaborative leadership in theory and practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2017, 89–96. doi: 10.1002/ace.20262

Lentz, C. (2020). ‘Tradition’Versus ‘Politics': Succession Conflicts in a Chiefdom of North-western Ghana. London, UK: Routledge.

Lutz, G., and Linder, W. (2004). Traditional structures in local governance for local development (Thesis). University of Berne, Berne, Switzerland.

Makinta, M. M., Hamisu, S. A., and Bello, U. F. (2017). Influence of Traditional Institutions in Farmer-herder Conflicts Management in Borno State, Nigeria. Asian J. Agric. Exten. Econ. Sociol. 1–6. doi: 10.9734/AJAEES/2017/33129

Mawuko-Yevugah, L., and Attipoe, H. A. (2021). Chieftaincy and traditional authority in modern democratic Ghana. S Afr. J. Philoso. 40, 319–335. doi: 10.1080/02580136.2021.1964206

Nyadera, I. N. (2018). South Sudan conflict from 2013 to 2018: Rethinking the causes, situation and solutions. Afr. J. Confl. Resolut. 18, 59–86.

Owusu-Mensah, I., Asante, W., and Osew, W. (2015). Queen mothers: the unseen hands in chieftaincy conflicts among the Akan in Ghana: myth or reality. J. Pan Afr. Stud. 8, 1–16. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/jacaps/vol3/iss1/2/

Rosenbaum, A. (2018). On the Current State of Public Administration Research and Scholarships: political accommodation or simply increasing irrelevance? Network of Institutes and Schools of Public Administration in Central and Eastern Europe. NISPAcee J. Public Adm. Policy 11, 11–23. doi: 10.2478/nispa-2018-0011

Soliku, O., and Schraml, U. (2018). Making sense of protected area conflicts and management approaches: A review of causes, contexts and conflict management strategies. Biol. Conserv. 222, 136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.011

Stacey, P. (2016). Rethinking the making and breaking of traditional and statutory institutions in post-Nkrumah Ghana. Afr. Stud. Rev. 59, 209–230. doi: 10.1017/asr.2016.29

Tseer, T. (2017). Conflict And Its Resolution In Northern Ghana: Examining The Causes And Intractability Of The Bimoba-Konkomba Conflict In Bunkpurugu Yunyoo District. Thesis submitted to the University for Development Studies

Van Bockhaven, V. (2020). Anioto and nebeli: local power bases and the negotiation of customary chieftaincy in the Belgian Congo (ca. 1930–1950). J. East. Afr. Stud. 14, 63–83. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2019.1710363

Yakubu, H. (2017). Chieftaincy Succession Disputes In Gonjaland; A Study Of Their Manifestations In Bole Traditional Area In The Northern The Northern Region Of Ghana. Thesis submitted to the University for Development Studies

Yaro, D. S., Tseer, T., and Achanso, A. S. (2020). Exploration of chieftaincy succession disputes in gonjaland: a study of their manifestations in the Bole traditional area. J. Global Research 1, 15–41. Available online at: https://www.research.lk/publications/research-papers/dr-david-suaka-yaro/Dr-David-Suaka-Yaro.pdf

Keywords: conflict, management, collaboration, traditional authority, chieftaincy conflicts, Collaborative Leadership Theory

Citation: Tseer T and Sulemana M (2022) Collaboration between traditional and central authorities in chieftaincy succession conflicts management in Ghana: Evidence from Bole traditional area. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:934652. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.934652

Received: 02 May 2022; Accepted: 30 August 2022;

Published: 21 September 2022.

Edited by:

Jane Freedman, Université Paris 8, FranceReviewed by:

Dickson Adom, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, GhanaOphelia Soliku, SD Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Ghana

David Suaka Yaro, University of Technology and Applied Sciences CKT-UTAS, Ghana

Copyright © 2022 Tseer and Sulemana. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tobias Tseer, Y2hyaXN0NG1lMDAyQHlhaG9vLmNvLnVr

Tobias Tseer

Tobias Tseer Mohammed Sulemana

Mohammed Sulemana