- 1Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, Baruch College, New York, NY, United States

- 2The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, New York, NY, United States

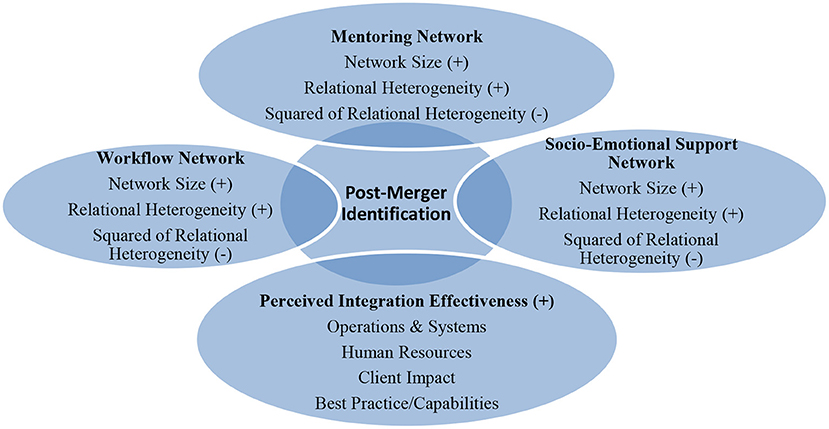

This paper incorporates insights from organizational identity and identification, social network research and post-merger integration to explore factors influencing employees' identification with a merged nonprofit organization. We propose that nonprofit employees' identification with the merged nonprofit organization is associated with their network size, relational heterogeneity, and perceived effectiveness of integration processes. Empirical results suggest that employees with larger mentoring and socioemotional support networks exhibit strong post-merger identification. Relational heterogeneity within the workflow network has an inverted U-shape relationship with post-merger identification. Employees' perceived effectiveness of integration processes significantly influences their sense of identity with the new organization. Implications for better managing post-merger identification are discussed.

Points for practitioners

• When designing work processes after the merger, nonprofit managers need to strike a balance between increasing opportunities for intergroup interactions and avoiding overburdening employees with outgroup connections.

• Increasing opportunities for employees to seek mentoring and socioemotional support may help them better adjust to the new organizational environment.

• The leadership of the merged nonprofit should keep employees well informed and engage them in the post-merger integration progresses.

Introduction

Faced with a plunge in charitable donations and government funding, nonprofits are undergoing a number of restructuring strategies to survive this tough economic climate. One important strategy is through mergers and alliances (Pradhan and Hindley, 2009; The Collaboration Prize, 2009; Chen and Krauskopf, 2012; Seachange, 2021). Mergers are extreme cases of strategic alliances that involve the process of combining two or more independent organizations into a new organization. As Cortez et al. (2009) estimated, the cumulative merger rate (measured as the number of merger cases divided by mean number of organizations in 11 years) in the nonprofit sector is 1.5%, only 0.2 percentages lower than that in the for-profit sector (1.7%). The existing research has paid attention to the external and internal driving forces of nonprofit mergers (Kohm and La Piana, 2003; Ferris and Graddy, 2007; Campbell, 2008; Pietroburgo and Wernet, 2008), how nonprofit organizations decide to merge (Yankey et al., 2001; Pietroburgo and Wernet, 2008), and various restructuring forms through which partnering nonprofits integrate (Kohm et al., 2000; Yankey et al., 2001; Delany and Manley, 2003). Little is known regarding how previously separate and independent organizations integrate into a single organization through mergers (Benton and Austin, 2010).

The biggest challenge facing any organization after a merger is the integration of organizational cultures that evolve into a new organizational identity (Gammal, 2007; Pietroburgo and Wernet, 2008; Chenhall et al., 2015). Organizational identity is defined as central, distinctive, and enduring elements regarding an organization's members' collective sentiment about “who we are,” differentiating one organization from another (Albert and Whetten, 1985). Organizational identification is how employees define themselves in their relationships with the organization and the importance attached to that self-definition (Cooper and Thatcher, 2010). Mergers or acquisitions create problems of intergroup relations for organizations. When two organizations come together or when one takes over the other, the merged entity inherits competitive and sometimes bitter and antagonistic pre-merger relations between the merging partners. Because of negative responses and feelings toward employees of the other organization, the merger may fail (Hogg and Terry, 2000). There are many examples of failed mergers because of prevailing “us” vs. “them” dynamics, if employees refuse to give up their old identities. Managers often struggle with fusing multiple identities brought from different prior organizational affiliations into a distinct new whole (Pratt and Foreman, 2000). Nonprofit organizations tend to attract employees with strong ideological orientations. Nonprofit mergers as an organization change, not only disrupt employees' routines, but also threaten organizational identity they attached to. Achieving post-merger identity is thus especially challenging for merged nonprofits (Lee and Bourne, 2017).

Social psychological research suggests that how individuals identify with a new organization is inextricably linked to individuals' networking relations both within and between groups and their initial experience with the merging process (Hogg and Terry, 2000; Terry et al., 2001; Brickson, 2005; Ramarajan, 2014). In this paper, we integrate theories of organizational identity and identification, social network analysis and post-merger integration processes to explore factors instrumental to individuals' identification with a merged nonprofit. We examine how the structure of employees' networks— network size and heterogeneity of their interpersonal relationships (the percentage of cross-group ties over total ties)—affects their post-merger identification. We examine how implications differ by the type of formal and informal networks. We further examine the role of perceived effectiveness about the integration processes in building up the new organizational identity.

The article proceeds as follows. First, after reviewing the theories of organizational identity and identification in the context of mergers, we incorporate insights from the intraorganizational networks literature and research on post-merger integration performance into a model of antecedents of employees' post-merger identification. Next, we empirically test this model using a case of merger involving two nonprofit organizations. After describing data collection, measurements, and estimate methods, we present the results of our empirical study. The paper ends with a discussion of findings, managerial implications and limitations.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Organizational identification in the context of mergers

Organizational identification measures the extent to which individual employees think themselves in terms of a specific organization and their perception of oneness or sense of belongingness with an organization (Ashforth et al., 2008). A high degree of identification with an organization has been shown to lead to many positive organizational outcomes: greater loyalty, increased likelihood that employees will go beyond their duties to benefit the organization, reduced turnover intentions, and increased cooperative behaviors (Mael and Ashforth, 1992; Bartel, 2001; Dukerich et al., 2002). In the organizational literature, identification is understood as both a state of being identified with an entity and a process of becoming identified with an entity (Kreiner et al., 2006). When identification is referred to as a state, individual and organizational identities align (Whetten, 2007) and therefore individuals achieve a sense of “oneness” with their organization. Identification, as a process of reciprocal interaction between the individual and the target of identification (Ashforth et al., 2008), unfolds when an individual discovers affinity with the target and seeks to alter his or her identity to align with that of the target (Pratt, 1998). But events of organizational restructuring can dislocate the alignment of individual and organizational identities by bringing competing identities into association. In this study, we focus on factors that drive the identification process following organizational mergers.

Research on organizational identity and identification has largely drawn from social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) and its extension to self-categorization theory (Turner et al., 1987). According to social identity theory, individuals derive self-definition from their memberships in social groups. Categorizing one's self as part of a social group accentuates perceived similarities with other members within the same group. Subsequently the differences between “ingroup” and “outgroup” become more salient. An organizational merger imposes a new organizational identity on employees. It can be perceived as a threat to group distinctiveness as group members are forced to change their pre-merger identity. Mergers create identification problems because employees tend to act on the identity based on their prior affiliation rather than identity imposed by the merger. Group members are usually motivated to preserve their group distinctiveness from other groups. One of the reactions aimed at restoring group distinctiveness are an ingroup bias (van Leeuwen et al., 2003; Baldassarri and Page, 2021)—when people strongly identify with a group, they tend to exaggerate attitudinal and behavioral similarities between themselves.

Organizations consists of complex networks of internally structured intra and intergroup relations. An ingroup bias will be manifested in employees' patterns of interpersonal relationships formed within a merged organization. In social network studies, the ingroup bias is equivalent to homophily, a natural tendency to connect with others sharing similar attributes such as age, gender, education, prestige, social class, tenure, and occupation. Chen and Krauskopf (2012) found that intraorganizational networks in a merged nonprofit reflected homophily based on prior organizational affiliations. Employees with the same pre-merger organizational affiliations are more likely to have networking ties with one another than do employees with different pre-merger affiliations.

Whether it is an ingroup bias or a pre-merger affiliation-based homophily, issues of ingroup vs. outgroup memberships will cause problems for organizational identification among members across different groups. An ingroup bias will produce more negative attitudes toward the outgroup members. Intergroup hostility will lead to a drop in identification with the new organization and ultimately endangers the success of the merger (van Leeuwen et al., 2003).

Formal and informal networks of workflow, mentoring and socio-emotional support

Social psychological studies highlight the importance of perceived intergroup relationships in fostering employees' identification with the merged organization (Hogg and Terry, 2000). Little is known regarding how the different types of interpersonal networks affect employees' post-merger identification. We extend this line of research by identifying three formal and informal networking ties within the merged organization. Within each type of network, we focus on impacts of two structural characteristics —network size and relational heterogeneity—on employees' post-merger identification.

Within any organization, employees reply on networks of interpersonal relationships for resources, information and support necessary for their career success. Three interpersonal relational networks are typical in any organizational setting and are the focus in this study. They are workflow networks, mentoring networks and networks for socioemotional support. The different types of networks can be characterized along two dimensions: formality (from formal to informal) and instrumentality (instrumental to expressive). Formal networks include formally defined supervisor-subordinate relationships within a functional department and interdepartmental collaborations to complete a specific job-related task. Although formal networks describe authority line embedded in working relationships, much of the actual work in organizations are also likely to be accomplished through informal networks (Krackhardt and Stern, 1988; Minbaeva et al., 2022). Informal networks refer to more discretionary patterns of relationships and their content of interactions may be either work-related, social, or both. We describe the nature of interpersonal relationships within a network as ranging from instrumental to expressive. Instrumental ties include exchanges of job-related resources, information, expertise, career directions and guidance. Expressive ties involve exchange of friendship, trust and socio-emotional support (Ibarra, 1993, 1995).

Workflow network

A workflow network consisting of the most formal and instrumental network ties within an organization, reflecting the formally prescribed set of task interdependencies between organizational members as a result of division of labor. Employees exchange inputs and outputs on the basis of the workflow sequences (Brass and Burkhardt, 1992). The workflow network reflects how individuals define themselves in terms of their specific role relationships with other individuals in the workplace.

Mentoring network

A mentoring network is less formal than the workflow network and yet combines both instrumental and expressive elements. In organizational socialization literature, two major functions of mentoring are identified: career-related and psychosocial support (Kram, 1985; Humberd and Rouse, 2016). The career functions include sponsorship, exposure and visibility, coaching, and assigning challenging tasks. The psychosocial functions include role modeling, acceptance and confirmation, counseling, and friendship. In a mentoring network, a mentor assigns challenging tasks to a mentee, provides proper assistance in accomplishing the tasks, and purposefully helps build the mentee's positive impression of the organization. Mentoring relationships within a merged organization were found to help employees cope with stress as a result of mergers (Siegel, 2000).

Socioemotional support network

As the most informal network, the socio-emotional support network has the expressive function of helping employees cope with personal life problems and emotions. Emotions as subjective experiences are most often experienced in social interactions and are often shared with others (Parkinson, 1996). Social exchange theory suggests that employees receive socioemotional resources through their interpersonal relationships at work (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005). It is increasingly recognized that emotions and the way they are experienced and expressed in the work environment have a fundamental impact on a wide range of work-related outcomes (Ashkanasy, 2003). Hurlbert (1991) found that membership in a co-worker network was positively associated with job satisfaction because the network may provide resources to help the individual cope with job stress. Thus, we expect employees' socioemotional support network to significantly influence their identification with the merged organization.

In addition to the content and nature of networking ties, the structure of interconnection surrounding a relationship may also influence employees' post-merger identification. Here, we focus on two basic properties identified in network research: network size and relational heterogeneity.

Network size

Certain structural characteristics of intraorganizational networks, such as network size, are believed to be correlated with important outcomes. The number of working contacts a person has reflects their level of involvement in the operation of the entire organization. More direct working contacts within a workflow network can enable the individual to access more co-workers for information and other resources. Larger mentoring networks were found to provide more career and psychosocial support in the early careers of lawyers (Higgins, 2000). They were associated with a greater number of promotions and a higher level of job-related satisfaction for university employees (Bozionelos, 2003; van Emmerik, 2004), greater life satisfaction among MBA students (Murphy, 2007), and greater self-efficacy of MBA alumni in a longitudinal study (Higgins et al., 2008). A larger network of socioemotional support enables an individual to tap into his/her “social capital” for moral or emotional support and informational support (Cohen and Wills, 1985; Taylor et al., 2004). We expect that individuals with more working contacts, mentoring relationships and socioemotional supporters are more likely to feel that they are an integrated part of the new organization. Thus, we hypothesize that

Hypothesis 1: In a merged nonprofit, the larger the size of an individual employee's workflow, mentoring or socioemotional support network, the more likely he/she feels identified with the new organization.

Relational heterogeneity

A larger network alone may not be a sufficient condition for post-merger identification. If most network ties are formed within the same pre-merger group, ingroup bias will be further consolidated. On the contrary, employees' response to a merger would be more favorable if they have high levels of contact with members from the other partnering organization. Thus, diversity of relational ties should be taken into account. Relational heterogeneity is defined as the extent to which individuals connect with others with different backgrounds and attributes (Gulati et al., 2010). For the purpose of this study, we define it more narrowly as the degree to which employees have developed outgroup vs. ingroup network relationships, where the group is defined by individuals' pre-merger affiliation. With more heterogeneous relationships, intergroup contact and perceived permeability of intergroup boundaries will neutralize ingroup bias and strengthen employees' post-merger identification.

Extensive intergroup contact allows members of different groups to discover similarities in beliefs and values and therefore promotes the development of harmonious relations between groups (Allport, 1954). Increasing contacts between groups not only reduce the tendency for group members to categorize others on the basis of group membership, but also serve to change people's cognitive representation of group memberships from a differentiated ingroup-outgroup representation to an inclusive superordinate category. Gaertner et al. (1996) found that many opportunities for intergroup interactions reduced ingroup bias among banking executives involved in a corporate merger. When group members feel that they can pass freely from one group to another and they have access to opportunities that are afforded to members of the other group, the group boundaries are perceived to be permeable. Employees of pre-merger organizations who perceived the intergroup boundaries to be highly permeable would be better adjusted to the merger on both job-related (organizational commitment and job satisfaction) and person-related (emotional wellbeing and self-esteem) outcomes. They would be less likely to engage in ingroup bias and be more likely to identify with the new organization. In a study of merging two airlines, Terry et al. (2001) confirmed that strength of identification with the new organization was strongest for those who reported high levels of contact with members of the partnering organization and for those who perceived that the intergroup boundaries in the merged organization were permeable.

However, we propose that increasing relational heterogeneity may be associated with decreasing returns or even negative outcomes for organizational identification. From a cognitive perspective, organizational members' views of their organizational reality are negotiated between interacting individuals. People use their social networks to find support for their own interpretations of organizational experience. When outgroup ties dominate over ingroup ties, employees from one group may have excessive exposure to the views and perspectives of another group and find little support for their own opinions and interpretations of the new organization. Employees are likely to be in a state of discomfort or cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957). Such a discomfort is likely to result in a reduction in overall satisfaction with work as well as their post-merger identification.

Consistent with theories of intergroup contact and perceived permeability of group boundaries, we argue that at relatively low levels of relational heterogeneity, the greater the extent of outgroup (vs. ingroup) ties, the greater the identification with the new organization. At higher levels of relational heterogeneity, however, further increase in outgroup (vs. ingroup) ties may have negative consequences that are likely to offset the positive effects. We thus hypothesize that

Hypothesis 2: There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between relational heterogeneity and post-merger identification.

Perceived integration effectiveness

Previous studies of organizational mergers identified employees' positive assessment of the merging process as an important condition of successful mergers (Hogg and Terry, 2000). This is in addition to promotion of intergroup interaction and cooperation. Immediately after the merger, the first thing employees in the combined organization experienced is how mangers handled the integration. Researchers and practitioners increasingly pay attention to the performance of integration process at the task level.

Performance of the post-merger integration process is defined as “the degree to which the targeted level of integration between the two organizations has been achieved across all of its task dimensions in a satisfactory manner” (Zollo and Meier, 2008, p. 56). As many as four dimensions of integration performance were identified: alignment of the operations and systems (such as control systems, conversion of IT systems) (Datta, 1991; Weber, 1996), integration of human resource programs and policies (salary and benefit programs) (Buono et al., 1985), impact on existing clients (Bekier and Shelton, 2002), and transfer of capabilities across the organizational boundaries (Capron, 1999). Poor handling of integration along the four dimensions has been linked to employees leaving the merged organization. We hypothesize that

Hypothesis 3: Employees' positive assessment of post-merger integration process is positively related to their post-merger identification.

We summarize all the hypotheses into Figure 1.

Data, measures and methods

Data collection

The authors of this study examined a merger between two nonprofits in the micro-financing sector through individual interviews, archive reviews, and an online survey of post-merger integration. For the acquirer, the motivation for the merger was strategic— to scale up and increase its leadership role in the micro-financing community. The acquired, on the other hand, was driven into the merger by a lack of financial stability and a high level of financial leverage. Its lending portfolio grew from $2 million into $8 million in 3 years; yet its repayment rate was down from 97 to 81%. The merger was also encouraged by funding agencies such as foundations who would like to see fewer applicant organizations that compete for the same but limited amount of resources.

In this case, two nonprofits operating in the same market and serving the identical clients with the similar services come together—a horizontal merger. Mergers of this kind usually require extensive integration because of duplicating structures and functions between the partnering organizations. During the integration, the CEO of the acquirer became the new President and CEO of the merged organization, and two vice presidents were from the acquired. They restructured different departments by streamlining programs and reducing functional duplication. They restructured product portfolio, integrated the software platform, and standardized guidelines for collections, accounting/finance and underwriting. The staff members first had the opportunities to interact with each other in a 3-day retreat. Then, bi-weekly department meetings and monthly organization-wide meetings were organized to update employees about the merging process. The organization also circulated internal newsletters reporting progress of integration. After the merger was completed, the merged organization had 62 managers and staff. Among them, 24 were from the acquirer; 21 were from the acquired; 17 were new hires.

The two partnering organizations had very different cultures. The working culture of acquiring organization was more business-like, while the acquired one paid more attention to its grassroots social missions. According to our interviews, employees from the acquired organization expressed concerns that the merged organization would move away from working with traditional grassroots micro-financing clients to supporting highly established businesses. They had the perception that the acquirer's policies and culture filtered through the organization top-down and that they were subordinate to the acquiring group and not treated fairly.

This study started 8 months after the completion of the merger. Eight months is, arguably, the right timing for this study. If it had been immediately after the merger, employees' identification with the new organization would not have formed. If it were years after the merger, employees with poor identification with the new organization may have already quitted; damages to the organization such as loss of key personnel and expertise may have already occurred. With the support of organizational leadership, we invited all the employees in the merged organization to participate in an online survey. It took respondents about 20–30 min to complete the survey. Fifty-six participants responded to the survey, yielding a response rate of 90%.

Measures

Post-merger identification

Our survey included three items (based on those used by van Leeuwen et al., 2003) to assess strength of employees' identification with the merged organization. They are: (1) I am happy to be in X organization; (2) I feel like a part of X organization; and (3) I feel close to people at X organization. All three are rated using a 5-point likert scale, from 1=Strongly disagree to 5= Strongly Agree. With a Cronbach's α value of 0.70, we constructed a single measure of post-merger identification by taking the average of the three.

Formal and informal intraorganizational networks

In the survey, we asked participants to nominate individuals with whom he/she worked, received mentoring, and sought socio-emotional support in the merged organization. These data were used to construct workflow, mentoring and socioemotional support networks within the merged organization. The survey questions concerning the workflow network were adopted from Brass (1981, p. 332):

On the list below, please select names of the people at X organization who you would consider have been your primary work partners over the last 6 months. Work partners are people who provide you with your workflow inputs, as well as the set of people to whom you provide your workflow output. Workflow inputs are any materials, information, clients, tasks, etc. that you might receive in order to do your job. Workflow output is the work that you send to someone else when your job is complete.

On the basis of mentor's definition, we designed the questions concerning the mentoring network as follows:

Are there any individuals at X organization whom you regard as a mentor? A mentor is someone who has taken a strong interest in your professional career over the last six months by providing you with opportunities and/or help with your career advancement.

We adopted questions on socioemotional support networks from Toegel et al. (2007) as follows:

Over the last 6 months, who have you been going to within X organization when you experience anxiety, tension or emotional pain? These are people who you think would assist you when you need support and help in coping with your personal problems and your negative emotions.

Network size

For each of the three networks, we measured individual employee's network size by its degree of centrality—the total number of each individual's direct ties with others in the network. As this measure depends on the size of the entire network within the organization, it is important to standardize the measure across networks. We did so by dividing the number of direct ties of a given individual by the maximum value of this measure among all individuals. We used UCINET (Borgatti et al., 2002), a software program for social network analysis, to calculate the standardized degree centrality.

Relational heterogeneity

We measured relational heterogeneity by dividing the number of outgroup ties by the total number of ties (both outgroup and ingroup). This index ranges from 0 to 100%. To test a nonlinear relationship between relational heterogeneity and post-merger identification, we included in our analysis both the measure itself and a squared term.

Perceived integration effectiveness

We asked the respondents to assess the post-merger integration along four dimensions: alignment of operations and systems, integration of human resources, positive impact on existing clients, and transfer of best practice/capabilities across the organizational boundary1. Responses were coded on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). These four items were highly correlated (Cronbach's α = 0.78). We thus used the mean score to construct a single measure.

Our analysis controlled for several individual characteristics believed to affect identification independently from the properties of their relational networks. First, women are more likely to define themselves in ways that reflect a relationalist and collectivist orientation, while men tend to define themselves in ways that reflect an individualist orientation (Cross and Madson, 1997). We included a dummy variable for Male (Yes = 1, No = 0) to control for gender differences. Second, as in most mergers, the two organizations in our case did not come together on equal status: employees of the acquired organization felt more threatened by the merger; it is likely that they did not identify with the new organization as strongly as members of the acquiring organization. We thus included two dummy variables, Acquired (Yes=1, No=0) and New Hires (Yes = 1, No = 0), Acquiring being the reference, to control for the pre-merger status of individuals. Third, managers may have more extensive networking relationships than non-managers. At the same time, being a manager may also affect the way they identify with the new organization. To control for confounding by rank and nature of job, we treated senior managers as the reference and included two dummy variables: Mid Managers (Yes = 1, No = 0) and Non-Managers (Yes = 1, No = 0).

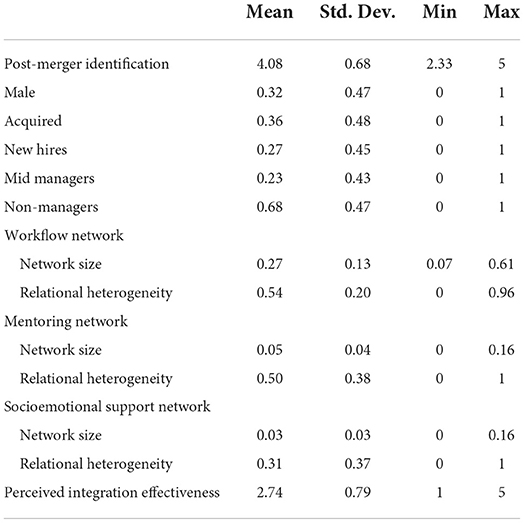

We present descriptive statistics of all variables in Table 1. Among all the respondents, 32% were male and 68% female (S.D. 0.47). On their pre-merger status, 36% were from the acquired organization (S.D. 0.48), 37% from the acquiring group and 27% were new hires (S.D. 0.27). 9% of respondents were senior managers, 23% mid-level managers (S.D. 0.43) and 68% staff members (S.D. 0.47). Informal and expressive networks were more difficult to form than formal and instrumental ones. So it is not a surprise to see that employees on average had the highest network size (mean 0.27, S.D. 0.13) and relational heterogeneity (mean 0.54, S.D. 0.20) in the workflow network. The mentoring network (mean 0.05, S.D. 0.04; mean 0.50, S.D. 0.38) ranked second and socioemotional support network (mean 0.03, S.D. 0.03; mean 0.31, S.D. 0.37) the least. The mean value of perceived effectiveness of post-merger integration was 2.74 (S.D. 0.79).

Analytical methods

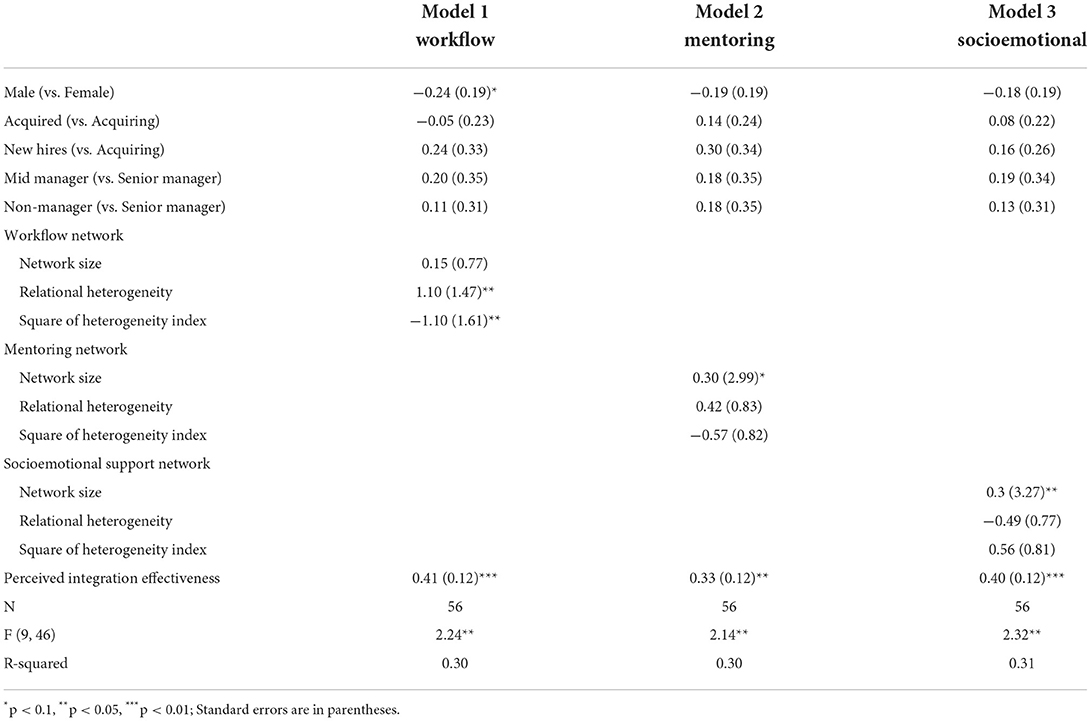

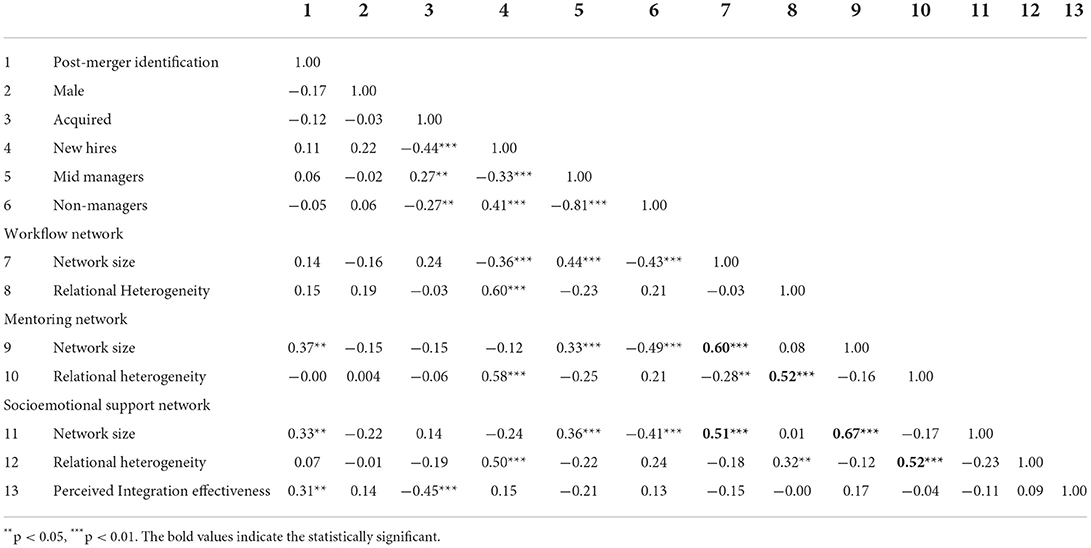

We performed OLS regressions to test hypotheses regarding how network size and relational heterogeneity (each measured from three types of networks), and perceived effectiveness of integration processes are associated with employees' identification with the merged organization. Correlations among all variables are shown in Table 2. We found that the measures of network size and relational heterogeneity across the three networks were highly correlated at significant levels. Including them in one regression model would cause serious multicollinearity problems. We thus conducted a separate OLS regression for each of the three networks.

Table 2. Correlations of post-merger identification, control, network variables and perceived integration effectiveness.

Results

The results of our analyses predicting strength of employees' post-merger identification are shown in Table 3. The three models explained 30–31% of all variations in the data. Overall, support for hypotheses regarding network structural characteristics (size and relational heterogeneity) varied across different networks. Perceived effectiveness of integration, however, was consistently and strongly associated with post-merger identification.

Results of Model 1, focusing on workflow networks, weakly support Hypothesis 1 that a larger network is positively associated with stronger post-merger identification. The coefficient of network size did not achieve statistical significance. The coefficient for the linear measure of relational heterogeneity was positive and significant (β = 1.10, p < 0.05); the coefficient for the quadratic term was negative and significant (β = −1.10, p < 0.05), thus supporting Hypothesis 2 about the inverted U-shaped relationship between relational heterogeneity and identification. Based on the estimated model, we calculated the value of relational heterogeneity at which post-merger identification was maximized: 0.5. This indicates that, when relational heterogeneity was low, identification with the new organization increased with relational heterogeneity. However, once relational heterogeneity reached 50%, post-merger identification started to decrease with increase in outgroup ties as a percentage of all ties.

Contrary to results of workflow networks, results pertaining to the mentoring networks (Model 2) and socioemotional support networks (Model 3) supported Hypothesis 1. Estimated coefficients were 0.30 (p < 0.1) and 0.37 (p < 0.05) respectively. However, Hypothesis 2 was not supported in either analysis. In the mentoring network analysis, estimated coefficients of the linear and quadratic terms of relational heterogeneity had signs that were consistent with the hypothesis, but were not statistically significant. In the analysis about socioemotional support network, signs of coefficients were inconsistent with the hypothesis and did not achieve statistical significance.

Results across all three models supported Hypothesis 3, indicating positive relationships between perceived integration effectiveness and post-merger identification (β = 0.41, p < 0.01 in Model 1; β = 0.33, p < 0.05 in Model 2 and β = 0.40, p < 0.01 in Model 3).

Few control variables achieved statistical significance. The coefficients for male were all negative in all the three models, but only at the significant level of 0.1 in model 1. Even controlling the network size, relational heterogeneity, perceived effectiveness of post-merger integration, male employees did not feel identified with the new organization as strongly as their female colleagues in the workflow network. Although not significant, the negative sign of acquired suggests that employees from the acquired group felt less identified with the merged organization in the workflow network.

Discussion and conclusion

As one nonprofit executive who experienced a merger commented, “A merger usually started with financial reasons, but failed in human reasons.” One of the human reasons is whether employees identify with the merged organization. For a merged nonprofit to function well, its employees must identify with their work and their organization. Our research starts from the premise that organizational identification is influenced by intergroup relations and perceived effectiveness of the integration process. An organization can be conceptualized as multiple networks in which individuals of different groups are interacting with each other. These interactions take place as formal or informal relationships, which shape an individual's identification process. The process of organizational identification occurs through interactions with organizational members. Individuals interact with others to learn about the values and attitudes that are associated with their new organization.

In this study, we incorporated insights from organizational identity and identification, social network research and post-merger integration to understand factors influencing employees' identification with a merged nonprofit organization. We hypothesized that two key structural characteristics of intraorganizational networks - network size and relational heterogeneity- and employees' perceived effectiveness of post-merger integration would be associated with their identification. Using network data collected from a case of nonprofit merger, we empirically examined these hypotheses in three types of networks: workflow, mentoring, and socioemotional support. Our main empirical findings are threefold. First, employees with larger networks for mentoring and socioemotional support feel more identified with the merged organization. Second, more relational heterogeneity within the workflow network is a mixed blessing for post-merger identification. When there were few outgroup ties relative to ingroup ties in a workflow network, an increase in relational heterogeneity (measured by proportion of all ties that are outgroup) was associated with an increase in identification. However, after a certain threshold, the negative impact of more outgroup ties (potentially a result of conflicting roles and individuals' attempt to balance loyalty to different groups) seemed to outweigh the positive impact derived from increased cross-group working contact. Third, employees' subjective assessment of the integration process with regard to operations and systems, human resource policies, impact on existing clients and best practice and capabilities strongly influenced their sense of identification with the merged organization.

Our study advances the nonprofit management theory and research in the following ways. First, our study applies theories of organizational identity and identification to enriching our understanding of nonprofit management. These two constructs have begun to gain traction in current research (Sandfort, 2011; Battilana et al., 2017). Existing studies examined how employees' interpretations of organizational identity determined their responses to leadership succession in a nonprofit (Balser and Carmin, 2009); discussed the strategic and structural implications of organizational identity for nonprofit organizations (Young, 2001); and explored the roles of relationships and employee retention (Cooper and Maktoufi, 2019). Second, this study integrates three streams of research – organizational identity and identification, social network, and post-merger integration – into a model of antecedents of post-merger identification. Our study empirically investigates the relationship between organizational identification and interpersonal networks, thus advancing research on organizational identity and identification. Third, the findings of our study render some practical guidance to nonprofit organizations on how to effectively foster and manage employees' identification with merged organizations.

Our findings have several important practical implications for nonprofit mergers. First, our findings suggest that, when designing work processes after the merger, nonprofit managers need to strike a balance between increasing opportunities for intergroup interactions and avoiding overburdening employees with outgroup connections. As our study indicates, a balance of ingroup vs. outgroup relationships in the workflow network may be critical to fostering post-merger identification. It may be best to balance loyalty to and identification with employee's own group and loyalty to and identification with another group, and not overemphasize either one to the detriment of the other.

Second, mergers often produce enormous uncertainty and stress. Our findings suggest that increasing opportunities for employees to seek mentoring and socioemotional support may help them better adjust to the new organizational environment. Planners of nonprofit mergers may sow the seeds for these networks by encouraging and facilitating informal connections through retreats, consultations, and joint planning in the pre-merger stage. Nonprofit managers may identify individuals who are likely to serve as mentors or to provide socioemotional support and encourage them to reach out to their colleagues.

Third, we found that perceived effectiveness of post-merger integration played an important role in post-merger identification. A direct implication of this finding for leadership of the merged nonprofit is to do a better job of keeping employees well informed about the progresses, making the processes transparent and engaging employees in decision-making: what problems were encountered, and how they were handled. Managers should pay special attention to four tasks. One is integrating different operation and information systems. Since the largest cost of nonprofits is personnel, addressing personnel issues is critical to the success of a merger. One critical issue is to resolve salary inequities and benefit discrepancies brought from different partnering organizations. Nonprofit employees always strongly identify with the programs with which they work and are committed to clients they serve. So the efforts must be made to preserve the range and breadth of services in the communities affected. To realize synergy of the merger, key knowledge and expertise must be effectively retained and transferred across organizational boundaries.

Limitations

Our study has three limitations. First, the case we studied represents a horizontal nonprofit merger that required streamlining programmatic areas and reducing functional duplication. In other nonprofit mergers, operation-wise, partnering organizations may remain separate and independent; the parent organization controls the board, but the staffs actually remain quite distinct because of little or no overlap in program operation. We might conceptualize mergers along a continuum from low to high integration. In some mergers, the board may want low integration to limit the risk to the organization of a failed merger. Over time, though, the board may decide that greater integration may be necessary in the interest of efficiency. Under these circumstances, rather than imposing a new identity upon employees, it is advised that keeping multiple organizational identities may better serve the interests of the merged organization.

Second, even for nonprofit mergers of the same nature, we cannot generalize our findings of a study that used data from a single case. It is particularly true for studies that involve network research. Any organizational network is unique (Isett et al., 2011). Intraorganizational networks are embedded in a specific organizational context. The behavior, interactions and dynamics of networks actors is constrained by that context (Heikkila and Isett, 2004).

Third, our study is cross-sectional. Mergers take time and move through stages, during which different processes of organizational identification may operate. In future studies, it will be important to track these processes in mergers over time. Longitudinal research projects can help clarify how employee identification develops over time.

Data availability statement

The data for this study is not available because there is a requirement to keep the information on survey respondents confidential.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by CUNY Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by Professional Staff Congress Research Award, the City University of New York.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We adopted the survey instruments from Zollo and Meier (2008).

References

Ashforth, B., Harrison, S., and Corley, K. (2008). Identification in organizations: an examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manage. 34, 325–374. doi: 10.1177/0149206308316059

Ashkanasy, N. (2003). “Emotions in organization: a multilevel perspective,” in Research in Multi-level Issues, eds Dansereau, F., and Yammarino, F. J. (Greenwich, CT: Elsevier JAI Press), 9–54.

Baldassarri, D., and Page, S. E. (2021). The emergence and perils of polarization. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 118, e2116863118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116863118

Balser, D., and Carmin, J. (2009). Leadership succession and the emergence of an organizational identity threat. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 20, 185–201. doi: 10.1002/nml.248

Bartel, C. (2001). Social comparisons in boundary-spanning work: effects of community outreach on members' organizational identity and identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 46, 379–413. doi: 10.2307/3094869

Battilana, J., Besharov, M., and Mitzinneck, B. (2017). “On hybrids and hybrid organizing: a review and roadmap for future research,” in The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, eds Greenwood, R. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 128–162.

Benton, A., and Austin, M. (2010). Managing nonprofit mergers: the challenges facing human service organizations.” Adm. Soc. Work 34, 458–479. doi: 10.1080/03643107.2010.518537

Borgatti, S., Everett, M., and Freeman, L. (2002). UCINET for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. (Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies). Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA.

Bozionelos, N. (2003). Intra-organizational network resources: relation to career success and personality. Int. J. Org. Anal. 11, 41–66. doi: 10.1108/eb028962

Brass, D. (1981). Structural relationships, job characteristics, and worker satisfaction and performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 26, 331–348. doi: 10.2307/2392511

Brass, D., and Burkhardt, M. (1992). “Centrality and power in organizations,” in Networks and Organizations: Structure, form and Action, eds Nohria, N., and Eccles, R. G. (Boston: Harvard Business School Press), 191–215.

Brickson, S. (2005). Organizational identity orientation: forging link between organizational identity and organizations' relations with stakeholders. Adm. Sci. Q. 50, 576–609. doi: 10.2189/asqu.50.4.576

Buono, A., Bowditch, J., and Lewis III, J. W. (1985). When cultures collide: the autonomy of a merger. Hum. Relat. 38, 477–500. doi: 10.1177/001872678503800506

Campbell, D. (2008). Giving up the Single Life: Leadership Motivations for Interorganizational Restructuring of Nonprofit Organizations. Center for Nonprofit Strategy and Management, Working Paper Series. New York, NY: Baruch College of the City University of New York.

Capron, L. (1999). The long-term performance of horizontal acquisitions. Strateg. Manag. J. 20, 987–1018.

Chen, B., and Krauskopf, J. (2012). Integrated or disconnected? Examining formal and informal networks in a merged nonprofit. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 22, 325–345. doi: 10.1002/nml.21063

Chenhall, R., Hall, M., and Smith, D. (2015). Managing identity conflicts in organizations: a case study of one welfare nonprofit organization. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 45, 669–687. doi: 10.1177/0899764015597785

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Cooper, D., and Thatcher, S. (2010). Identification in organizations: the role of self-concept orientations and identification motives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 35, 516–538. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2010.53502693

Cooper, K., and Maktoufi, R. (2019). Identity and integration: the roles of relationship and retention in nonprofit mergers. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 30, 299–319. doi: 10.1002/nml.21382

Cortez, A., Foster, W., and Milway, K. (2009). Nonprofit MandA: More than a tool for Tough Times. Boston, Massachusetts: The Bridgespan Group.

Cropanzano, R., and Mitchell, M. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J. Manage. 31, 874–900. doi: 10.1177/0149206305279602

Cross, S., and Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychol. Bull. 29, 512–523. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5

Datta, D. (1991). Organization fit and acquisition performance: effects of post-merger integration. Strateg. Manag. J. 12, 281–297. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250120404

Delany, S., and Manley, L. S. (2003). Mergers and Strategic Alliances for New York not-for-Profit Corporations. New York, NY: Lawyers Alliance for New York.

Dukerich, J., Golden, B., and Shortell, S. (2002). Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: The impact of organizational identification, identity, and image on the cooperative behaviors of physicians. Adm. Sci. Q. 47, 507–533. doi: 10.2307/3094849

Ferris, J., and Graddy, E. (2007). Why do Nonprofits Merge? Working Paper for the Center on Philanthropy and Public Policy. Los Angeles, California: University of Southern California.

Gaertner, S., Dovidio, J., and Backman, B. (1996). Revisiting contact hypothesis: the introduction of a common ingroup identity. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 20, 271–290. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(96)00019-3

Gammal, D. (2007). Before you say “I Do”: Why nonprofits should be wary of merging. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. Summer. 47–51.

Gulati, R., Kilduff, M., Li, S., Shipilov, A., and Tsai, W. (2010). The relational pluralism of individuals, teams, and organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 53, 914–915. doi: 10.5465/amj.53.5.zoj1210

Heikkila, T., and Isett, K. (2004). Modeling operational decision making in public organizations: An Integration of two institutional theories. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 34, 3–19. doi: 10.1177/0275074003260911

Higgins, M. (2000). The more, the merrier? Multiple developmental relationships and work satisfaction. J. Manag. Dev. 19, 277–296. doi: 10.1108/02621710010322634

Higgins, M., Dobrow, S., and Chandler, D. (2008). Never quite good enough: The paradox of sticky developmental relationships for elite university graduates. J. Vocat. Behav. 72, 207–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.11.011

Hogg, M., and Terry, D. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 121–140. doi: 10.5465/amr.2000.2791606

Humberd, B., and Rouse, E. (2016). Seeing me in you and you in me: Personal identification in the phases of mentoring relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 41, 435–455. doi: 10.5465/amr.2013.0203

Hurlbert, J. (1991). Social networks, social circles, and job satisfaction. Work Occup. 18, 415–430. doi: 10.1177/0730888491018004003

Ibarra, H. (1993). Personal networks of women and minorities in management: a conceptual framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 18, 56–87. doi: 10.5465/amr.1993.3997507

Ibarra, H. (1995). Race, opportunity, and diversity of social circles in managerial networks. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 673–703. doi: 10.5465/256742

Isett, K., Mergel, I., LeRoux, K., Mischen, P., and Rethemeyer, R. (2011). Networks in public administration scholarship: Understanding where we are and where we need to go. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 21, i157–i173. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muq061

Kohm, A., and La Piana, D. (2003). Structuring Restructuring for Nonprofit Organizations: Mergers, Integrations, and Alliances. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Kohm, A., La Piana, D., and Gowdy, H. (2000). Strategic Restructuring: Findings from a Study of Integration and Alliances Among Nonprofit Social Service and Cultural Organizations in the United States. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

Krackhardt, D., and Stern, R. (1988). Informal networks and organizational crises: an experimental simulation. Soc. Psychol. Q. 51, 123–140. doi: 10.2307/2786835

Kram,. K. (1985). Mentoring at Work: Developmental Relationship in Organizational Life. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foreman.

Kreiner, G., Hollensbe, E., and Sheep, M. (2006). Where is the “me” among the “we”? Identity work and the search for optimal balance. Acad. Manag. J. 49, 1031–1057. doi: 10.5465/amj.2006.22798186

Lee, Z., and Bourne, H. (2017). Managing dual identities in nonprofit rebranding: an exploratory study. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 46, 794–816. doi: 10.1177/0899764017703705

Mael, F., and Ashforth, B. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 13, 103–123. doi: 10.1002/job.4030130202

Minbaeva, D., Ledeneva, A., Muratbekova-Touron, M., and Horak, S. (2022). Explaining the persistence of informal institutions: the role of informal networks. Acad. Manag. Rev. doi: 10.5465/amr.2020.0224

Murphy, W. (2007). Individual and Relational Dynamics of Ambition in Careers (Doctoral dissertation). Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, United States.

Parkinson, B. (1996). Emotions are social. Br. J. Psychol. 87, 663–683. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1996.tb02615.x

Pietroburgo, J., and Wernet, S. (2008). Bowling Together: Anatomy of a Successful Association Merger. Center for Nonprofit Strategy and Management Working Paper Series. New York, NY: Baruch College of the City University of New York.

Pradhan, G., and Hindley, B. (2009). Passion and Purpose, Restructuring, Repositioning and Reinventing: Crisis in the Massachusetts Nonprofit Sector. Boston, Massachusetts: The Boston Foundation.

Pratt, M. (1998). “To be or not to be: central questions in organizational identification,” in Identity in Organizations: Building Theory Through Conversations, eds Whetten, D. A. and Godfrey, P. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 171–208.

Pratt, M., and Foreman, P. (2000). Classifying managerial responses to multiple organizational identities. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 18–42. doi: 10.5465/amr.2000.2791601

Ramarajan, L. (2014). Past, present and future research on multiple Identities: toward an intrapersonal network approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 8, 589–659. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2014.912379

Sandfort, J. (2011). Book review of exploring positive identities and organizations: Building a theoretical and research foundation edited by Laura Morgan Roberts and Jane E. Dutton. Int. Public Manag. J. 14, 252–255. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2011.582439

Seachange. (2021). A primer on Nonprofit Mergers and Sustained Collaborations: Lessons from New York City. New York, NY: New York Merger and Collaboration Fund.

Siegel, P. H. (2000). Using peer mentors during periods of uncertainty. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 21, 243–253. doi: 10.1108/01437730010340061

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior” in Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds Worchel, S., and Austin, W. G. (Chicago: Nelson-Hall), 7–24.

Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Kim, H. S., Jarcho, J., Takagi, K., and Dunagan, M. S. (2004). Culture and social support: Who seeks it and why? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 354–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354

Terry, D. J., Carey, C. J., and Callan, V. J. (2001). Employee adjustment to an organizational merger: an intergroup perspective. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 267–280. doi: 10.1177/0146167201273001

The Collaboration Prize. (2009). Available online at: https://lodestar.asu.edu/sites/default/files/coll_finalists_report-2009.pdf

Toegel, G., Anand, N., and Martin, K. (2007). Emotional helpers: the role of high positive affectivity and high self-monitoring managers. Pers. Psychol. 60, 337–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00076.x

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-categorization Theory. (Oxford, UK: Blackwell).

van Emmerik, I. J. H. (2004). The more you can get the better: mentoring constellations and intrinsic career success. Career Dev. Int. 9, 578–594. doi: 10.1108/13620430410559160

van Leeuwen, E., van Knippenberg, D., and Ellemers, N. (2003). Continuing and changing group identities: The effects of merging on social identification and ingroup bias. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 29, 679–690. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029006001

Weber, Y. (1996). Corporate cultural fit and performance in mergers and acquisitions. Hum. Relat. 49, 1181–1203. doi: 10.1177/001872679604900903

Whetten, D. (2007). “A critique of organizational identity scholarship: challenging the uncritical use of social identity theory when social identities are also social actors,” in Identity and the Modern Organization, eds Bartel, C. A., Blader, S., and Wrzensniewski, A. (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 253–272.

Yankey, J. A., Jacobus, B. W., and Koney, K. M. (2001). Merging Nonprofit Organizations: The Art and Science of the Deal. Cleveland, Ohio: Mandel Center for Nonprofit Organizations.

Young, D. R. (2001). Organizational identity in nonprofit organizations: Strategic and structural implications. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 12, 139–157. doi: 10.1002/nml.12202

Keywords: organizational mergers, post-merger identification, interpersonal networks, post-merger integration processes, organizational communication

Citation: Chen B and Krauskopf J (2022) Nonprofit post-merger identification: Network size, relational heterogeneity, and perceived integration effectiveness. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:933460. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.933460

Received: 30 April 2022; Accepted: 03 August 2022;

Published: 31 August 2022.

Edited by:

Rong Wang, University of Kentucky, United StatesReviewed by:

Sophia Fu, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United StatesYannick Atouba, The University of Texas at El Paso, United States

Copyright © 2022 Chen and Krauskopf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bin Chen, YmluLmNoZW5AYmFydWNoLmN1bnkuZWR1

Bin Chen

Bin Chen James Krauskopf1

James Krauskopf1